Research Summary - Christian Aid · Research Summary 3 1. Experiences in early warning and early...

Transcript of Research Summary - Christian Aid · Research Summary 3 1. Experiences in early warning and early...

Research Summary

Building resilience to El Niño drought - experiences in early warning and early action in Nicaragua and Ethiopia

October 2017

2 Research Summary

Christian Aid is a Christian organisation that insists the world can and must be

swiftly changed to one where everyone can live a full life, free from poverty.

We work globally for profound change that eradicates the causes of poverty,

striving to achieve equality, dignity and freedom for all, regardless of faith or

nationality. We are part of a wider movement for social justice.

We provide urgent, practical and effective assistance where need is great, tackling

the effects of poverty as well as its root causes.

christianaid.org.uk

Contact us

Christian Aid 35 Lower Marsh Waterloo London SE1 7RL T: +44 (0) 20 7620 4444 E: [email protected] W: christianaid.org.uk

UK registered charity no. 1105851 Company no. 5171525 Scot charity no. SC039150 NI charity no. XR94639 Company no. NI059154 ROI charity no. CHY 6998 Company no. 426928 The Christian Aid name and logo are trademarks of Christian Aid © Christian Aid

Front cover: Rain gauge managers and the monthly Climatico bulletin, Nicaragua. In Nicaragua, Christian Aid’s

implementing partners are Centro Humboldt and Movimiento Communal Nicaragüense; in Ethiopia, ActionAid

Ethiopia and BBC Media Action. Both projects are funded by DFID and Christian Aid.

Research Summary 3

1. Experiences in early warning and early action to El Niño and drought

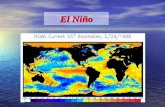

The 2015-16 El Niño was the strongest so far experienced in the 21st Century and roughly similar to,

although longer lasting than the 1997 event, the strongest of the 20th Century. It was among the four

most intense El Niños since 1950 and its impacts were severe. Drought affected about 60 million people1

across the Horn of Africa, Southern Africa, Central America and the Caribbean, South and South-East Asia.

Christian Aid has been supporting local partners across El Niño-affected areas through a variety of

resilience building projects. In both Nicaragua and Ethiopia (see map), this has involved facilitating

community risk assessment processes through participatory vulnerability and capacity assessments

(PVCA), with resilience-building interventions then based on the risk management “action” plans

developed from this process.

A key part of this has been to improve access to climate services (weather and climate forecasts and

associated information) to improve anticipation of a variety of risks, especially drought. 2015 therefore

provided an opportunity to understand if this approach had indeed been successful – had it enabled

affected communities to get through the risk management cycle more effectively (see IG12 below)? Did

they receive early warning and weather forecasts that would inform drought resilience measures before

or during the growing seasons? Did these have any impact on agricultural performance, water and food

security? Did participating communities access drought relief more effectively and did they move through

the recovery phase and back into long-term resilient development faster?

The main difference between the two countries involved in this assessment was the duration of the

projects, just two years at the time of assessment for Ethiopia versus six years for Nicaragua. This enabled

the research to investigate how a well-established project performed as compared to one starting only

recently, as well as comparing project participants with those not or less directly involved. The

investigation used a combination of surveys (covering 440 households), focus group discussions with

community representatives (12 in each country) and interviews with key informants, such as climate

scientists and Government agricultural advisors to understand their experience through the drought.

Communities in Nicaragua confirmed that the Christian Aid project implemented by Centro Humboldt and

MCN was their main source of support. In Ethiopia, as well as the project work implemented by ActionAid

Ethiopia, other assistance included the Productive Safety Net Programme (PSNP) and the network of

agricultural advisors at local government (woreda) level that provide information to small-scale farmers.

1 El Niño affects more than 60 million people – WHO (2016) 2 IG = infographic

Research Summary 4

IG1. Risk management cycle

Central America’s drought started in mid-2014 and by early 2015, as the El Niño strengthened, the

number of people requiring emergency support regionally increased to 2.8 million, with about 346,500 of

these in Nicaragua. The primera3 rains typically arrived late (see IG2 below) and apart from some short-

lived relief in early June, were substantially below average. In the north-western part of the country, less

than 40% of average July rainfall was received, leading to an early canicula4 before any crops had

matured. This pattern continued into the postrera5 with rainfall in most of western Nicaragua delayed by

20-30 days.

Drought impacts in Ethiopia evolved primarily in the eastern side of the country. Both seasons6 delivered

severely depressed levels of rainfall and at the beginning of June, belg failure was declared. The resulting

assessment identified 4.5 million people in need of emergency food assistance in August, rising to 8.2

million by mid-October before peaking in December at 10.1 million. For Kombolcha, the kiremt offered

little relief, whereas as Seru received significant October rainfall that flooded lowland areas, partly

compounding rather than alleviating drought stress. The results of the survey in terms of climate services

and agricultural productivity are summarised below (in IG3 and IG4).

3 Rains that last from May – July, the first cropping season of the year. 4 The mid-season dry period, usually from mid-July to mid-August. 5 Rains that last from August – October, the second cropping season of the year. 6 The belg (February - May) and the kiremt (June - September)

Research Summary 5

IG2. El Nino forecasts and rainfall, 2015

Source: ENSO forecasts as per those issued in 2015 by the Climate Prediction Centre/NCEP/NWS and the International Research Institute for Climate and Society; colours approximately as per the 3 levels proposed in the Inter-Agency Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for Early Action to El Niño/La Niña Episodes; to be classified as a fully-fledged El Niño, the +0.5 threshold must be exceeded for a period of at least 5 consecutive overlapping 3-month seasons. NH = northern hemisphere. 2015 rainfall data above from Africa Flood and Drought Monitor and Centro Humboldt community rain gauge records across 6 drought affected areas in Nicaragua (note: June precipitation mainly an upland event, Oct precipitation mainly a drought corridor event).

Research Summary 6

IG3. The results of Early Warning/Early Action and the impact pathway, Nicaragua

Research Summary 7

IG4. The results of Early Warning/Early Action and the impact pathway, Ethiopia

Research Summary 8

Early warning and drought resilient decision-making

In Nicaragua, survey results (see IG3 above) showed that most project participants received an El Niño

drought early warning around April 2015, with a good supply of weekly and monthly forecasts to guide

them as the drought evolved. To this was added drought-management advice which supported early

action. In Ethiopia, early warning was much less widespread (see IG4 above) with only about a third

receiving in Kombolcha and much later, around August, and virtually none in Seru. The focus group

discussions revealed a more varied picture from village to village (see examples below in IG5 and IG6), both

largely reinforcing the survey results but adding important local detail. This confirmed the importance of

local context and how drought impacts can vary quite considerably from one community to the next. For

example, communities in Nicaragua highlighted the important variety of communication channels used to

get forecast information; the value of their rain gauges in making precise decisions on planting time; and

how this relates to the difficulty of getting reliable seed for the right crop varieties. Those in upland areas

identified the primera as the more useful season, whilst a clear majority of those in the lowland “drought

corridor” areas did not plant in the first part of the season and saved their inputs for the postrera, which

did experience some late rains (corresponding to the rainfall data in IG2).

In Ethiopia, the limited early warning was confirmed – most people relied on their local knowledge and

explained that belg season failure was effectively their first early warning - but the value of the action plan

was cited as a key resource, with the village savings and loans associations seen as particularly important in

helping people invest in income generating activities so that they can purchase food from their earnings.

However, when combined with drought resilience advice, about two thirds of Kombolcha farmers made a

variety of drought-resilience decisions earlier. Being a younger project, radio-based forecasts started after

the drought but they were already seen as a valuable information resource. These weekly programmes

combine interviews and features on community-based resilience with the forecast. In both areas, the

impact of the drought on crop production and the value of resilience-building measured in the survey was

broadly confirmed through group discussions, although project participants in Seru gave a more positive

picture through group discussions of resilience actions they had taken before the emergency began.

Productivity

In Nicaragua, the result was maize yields 72% higher than farmers not in the project, together with a

reduction in input costs (such as seed, fertiliser) and damage avoided. Beans showed only a slight

improvement, reflecting their greater drought vulnerability, and as sorghum was a new crop with fewer

growers, comparison with e.g. previous droughts was difficult. Significant reductions in input cost and

damage were also recorded. In Ethiopia, farmers in Kombolcha achieved maize yields 45% higher (for the

core participants versus those only getting climate forecasts) and over 3x those in Seru, together with some

input cost reduction and damage avoided. In terms of overall productivity, this yield benefit needs to take

into account farmers reducing cultivated area, with 44% of farmers in Nicaragua and about 15% in Ethiopia

confirming that they used this strategy. However, farmers in Nicaragua stressed that they also diversified,

growing a range of vegetables and increasing their production of sorghum, a more drought-resilient crop

option. They also sourced new drought-resilient bean varieties as a result of advice received.

Access to drought relief

Although no emergency was declared in Nicaragua, once the extent of the drought was clear, some areas

received relief, which according to the focus group discussions, tended to be highly targeted to vulnerable

households or to children after Ministry of Health assessments. It was difficult to discern a systematic

pattern – the number of distributions varied from village to village, but groups in the dry corridor especially

emphasised the importance of the PVCA-based action plans that they had developed, submitting these to

municipalities and using them to lobby for and receive drought relief (see below in IG7). Only about 30% of

project participants received emergency support, with the majority relying on their increased drought

resilience to get through the El Niño.

Research Summary 9

IG5. Focus group discussion with Somotillo communities, Nicaragua

Research Summary 10

IG6. Focus group discussion with Kombolcha communities, Ethiopia

Research Summary 11

In Ethiopia, a much larger drought relief operation was initiated in 2016, about 8 months after the first

“belg” harvest failure. In the intervening period, the PSNP facilitated some drought relief and supported

some drought resilience actions that were identified in action plans. As a result, over 90% of those surveyed

in Seru and nearly 60% of in Kombolcha reported receiving drought relief. Like their counterparts in

Nicaragua, a clear majority agreed that their action plans include guidance on who to contact in the event

of a drought emergency situation and who in their community are the most vulnerable and in need of

assistance. In Seru, group discussions highlighted how this level of support did not prevent at least some

migration as household members moved out of the area in search of work to support their families.

Post-drought recovery

Better access to early warning and early action can also be traced through to a more efficient and faster

recovery in the 2016 agricultural seasons (also below in IG7). In both countries, being better able to resume

agricultural production, better access to the right inputs and better understanding of drought management

and forecast information has supported the resumption of livelihoods after the drought. Likewise, food and

financial security in both places, while still positively affected by resilience activities, tended to lag behind

other recovery measures, indicating the unavoidable impact experienced. Group discussions added further

detail, including a focus on food storage, seed banking of drought resilient local crop varieties and even

developing funds to buy land for farmers over-reliant on rented land they are unable to invest in for long-

term resilience (in Nicaragua).

Implications for drought management and climate change

Both the survey and community discussions demonstrate the importance of community-based climate

resilience-building to the ability of communities to anticipate, manage and recover from the El Niño-driven

severe drought of 2015/16. In Nicaragua, six years of work including resilience planning and improved use

of climate services have enabled rural communities to take a range of actions both before and during the

agricultural season to mitigate drought risk. In Ethiopia, similar results were achieved in Kombolcha,

although with lower impact, partly due to the increased severity of the drought there, the younger age of

the resilience project and the lack of early warning. Focus group discussions especially emphasised the

importance of the PVCA and resilience planning process in both mitigating drought risk and supporting

communities get through and recover after the drought. Climate information services, although

implemented after the drought, have received an increasingly positive response as a useful source of

weather forecasts and adaptation information. A number of implications emerge from the assessment,

including:

• The impact achieved in both Nicaragua and Ethiopia is consistent with other studies on the cost-benefit

of resilience. For example, a UNICEF/WFP study7 showed that all preparedness investments saved cost

and/or time, with an average of over $2 saved in humanitarian cost for every $1 spent. Earlier research8

has found that investment in resilience brings substantial returns in terms of need averted and broader

developmental outcomes, with benefit to cost ratios of $2.3 – $13.2 for each $1 spent. With both

climate change and the cost of humanitarian intervention increasing annually, this demonstrates the

need to transform the current approach from emergency declaration/late response to early

warning/early action.

• Impact also demonstrates the value of expanding access to climate information services, including

forecasts at various time scales (weekly, monthly, seasonal and long-term scenarios) so that those

affected can take autonomous resilience building actions appropriate to their local circumstances, work

through their community-based organisations (as e.g. the emphasis in Kombolcha on access to savings

7 Return on Investment for Emergency Preparedness Study - WFP-UNICEF (2017) 8 Economics of Early Response and Resilience (Summary) - TEERR (2013) The results in this summary are based on a longer, fully referenced impact assessment report.

Research Summary 12

IG7. Access to drought relief and post-drought recovery

IG8. Expanding the alert phase of the risk cycle to show how the global SOPs, local early action levels and risk mitigation can link and coordinate

Research Summary 13

Research Summary 14

and loans as a drought management resource shows) and access timely support and complimentary

advice from Government service providers and civil society partners.

• Although a wide variety of decision changes were made in response to drought early action advice, soil

and water resource management is also fundamental to drought resilience but received lower levels of

attention – only 30% of participants in Nicaragua and 2% in Ethiopia (Kombolcha) prepared land

differently in the lead up to the onset of rains. This suggests scope for greater focus on these aspects of

drought resilience that also yield dividends in normal years, strengthening the agro-ecological resilience

of farming systems and reversing land and agrobiodiversity degradation. Focus group discussions in all

areas referred to this need, suggesting that they are considered a priority for action by rural

communities. Other options, such as the promotion of appropriate methods of conservation agriculture,

terracing and other soil and water conservation methods would ensure vulnerable farmers can benefit

from the drought resilience they deliver.

• At the global level, the Inter-Agency Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for Early Action to El Niño

and La Niña Episodes need to be implemented as soon as possible to be operationally ready before the

next severe ENSO event. Local early action levels and SOPs need to be established and implemented in

all potentially affected countries to compliment the three global levels (see IG8 above). These will need

to consider seasonality and how El Niño or La Niña events evolve, as this will determine the extent of

global to local overlap and therefore how integration and funding for early action will work. A

substantial global funding facility needs to be put in place to address the current lack of any significant

formal process allocating international aid to early warning and early action.

• The results of this study (and others, as cited above) demonstrate that better, more cost-effective

humanitarian response results from improved early warning and early action. This is largely achieved

through building parallel redundancy – resilience capacity which is kept operationally efficient and is

useful in “normal” conditions (such as improved soils, regular use of climate forecasts, etc.) as well as in

response to shocks – and minimising reliance on standby redundancy, or resources which are only used

when a severe drought occurs, but may degrade through non-use in between shocks and are difficult to

justify in resource-constrained countries and communities. This means building a long-term “resilience

culture” to facilitate effective anticipation, organisation and action (see IG9 below).

IG9. Long-term resilience results in more effective early action, reducing the need for humanitarian response