SKILL-A-THON PRACTICE FEEDSTUFFS & PLANTS. FEEDSTUFFS Shelled Corn.

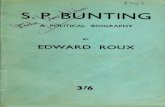

REPORT or - historicalpapers.wits.ac.za · A list of delegates is available on request from the...

Transcript of REPORT or - historicalpapers.wits.ac.za · A list of delegates is available on request from the...

/I)

✓ iREPORT or the: c o n f e r e n c e o n c o n s c i e n t i o u s o b j e c t i o n h e l d at n a t al

UNIVERSITY FROM OULY'tt - ',7,1983

CONTENTS

1 . Information of genera'! interest

The material contained in this section could be naoe available tr> any interested bodies. Although presented at the Conference in a variety of ways, it has been compiled so as to make it more readily accesible.

a) The political and socio-economic background to militarism in South Africa today.

b) Destabilisation

c) The Defence Amendment Act 1983 - a sunnary

d) COSG factsheet on Recent Developments in the SADF

e) Chronology of oppression and resistance.

f) A reading list

?. Id°as for groups working in the area of militarisation

All ideas, issues and plans generated by the Conference are compiled in this section. Their inclusion does not mean that thev received support from the Conference, or that they are either definitive or evaluated.They are included here to provide a full record of Conference discussicns.

a) Ideas and issues for further work in local grojps. _b) Ways of taking ud th? military issue among young otoplfc.

• c) Women and the military,d) Conscription and militarisation,

r ) e) The Defence Amendment Act.f) A programme for creating a civilian form of chjplaincy.g) Alternative Defence.h) Ideas for conducting o campaign againsi conscription.i) Draft SACC resolution referred back for discussion.

(

C

3. Conference decisions

The Conference made certain decisions, both as a full conference and in particular caucases.

a) The call to end conscription.b) A press statement made on behalf of the Conference.c) CPSA delegates resolution.

A list of delegates is available on request from the Durban COSG.

Edited and published by: Durbar. COSG, 19S3 Printed by: Peace Print

THE COh'TEXl

Struc tura1/economic factors:

Ideological factors:

)Political resistance factors:

This is t “Wed

0 growth o f monopoly c a p i ta i s r

° recession

" increesec1 jf.e?Dloyme~.

" r i s ' . rg i n f l a t i o n

0 price hikes in basic feedstuffs

° war economy

0 skills shortage

. ° role of Armscor to rest of economy -* i i 000 private businesses involved

0 skilled and unskilled unemployed lookir.g i to SADF for employment

0 housing - e.g. KTC

0 drought

° media - threat to and of media

0 myth of communist threat

° myth that the war can be won

0 myth that army can be used as shield while reform happens (PFP)

o jv

° bonus bonds

° army making *he-men"

° use of language - e.g. terrorist 7freedom fighter

0 use of army in adverts

6 apartheid - strjggle of ideas

0 education for perpetuation of the system

c worker action grows

0 worker-supportive action on increase

D rise of schools, youth, student, wooer’s, coraiiunity, sports organizations

0 orowth of exiles (white) resistingSADF call-up

0 re-emergence of ANC presence in W Care .and in general

6 relatively outspoken and ^biased ne«-s . reports on independent radio 6Cn

1 the '-*te as:^ r T ( ( i a n s i A U G H T

RESPONSE of the STATE

/N

Total onslaught requires a:

T O T A L . s t r a t e g y

r e f o r m

CO-OPTIONDIVIDE

REPRESSION

CONTROLRULE

Conn ions:

Wiehahn (TU recognition) t- Riekert (increased rights

to urban blacks,

De Lange

Constitutional proposals:

“Power sharing""Inclusion of "Coloureds ̂and Indians'(Extend laager)

Rikhoto judgement

Detention of trade unionists Tightened influx control O

Resettlement

Concentration of power

Apartheid

BantuStanj itr.plementctiot.

KTtK,hay?l i tsha Koornhoff Bills

cuota bi11 . .tightening up of security legislation police empowered to search c?rs anywncre Commission of Enquiry into SACC .Army used for repression not defence *

in civil issues .atrocities in Namibia:- economic/pcntica

need for war there .increasing role and extent of mii’.tc y

destabilization of froi.tline states economic and political reasons: kee: than economically dependant on SA e.g. NMR, uni LLA, Zimbabwe resistance troops raiding of ANC and SWAPO offices abrced

' homeland armies:- Transkei: 171 budget on development

rest on salaries, mostly police and army

- sophisticated recruiting propaganda

5 foreign support:- embargos and sanctions not enforce?- new set of international relations

e a Israel, Taiwan, Chile, etc.. military technology ? knowledge exchange

- US b USA involvement: ti metht)training centre on in‘•-rrog,at o- •co-operation'with 3.-a world gove ^enx

- international militarization and violence- massive IMF loan of R1 24G million- admittance of SADF to international

military trade fair in Greece- purchase of arms in Britain through

private sales- upward spiral of arms trade

0 business involvement in military ° influence of Army in Government:

National Security Council, Cabinet ° 'hearts and minds' policy: 801 political,

20% military ° extended call-up

The mood of the country suggests a

D E V E L O P I N G C R I S I S

RESISTANCEA- /N

The developing crisis is met by resistance from a niriuer of ^or:es

n e political storm in Durban re beachesRight-wing backlash. . ?bJttle of thc Berg(.«

° Broederfcord.'SAERA controversy ° ce".eral resistance to new const'itutior.

Eig business pressure

Foreign pressure:

Internal resistance:

Position of resisting whites:

negative coverage of SADF in Namibia at UN

increase in anti-SADF reporting from journalists in neighbouring countries

changing as economic crisis continues

T.U. activity

community resistance eg. Driefontein, KTC, Lamontville,

• Cnesterville, Clair-wood

COSAS and AZASO

growth re-emergence of democratic organisations

Charterists <---------- > National For^

non-racial struggle

1 increasingly isolated from white comunity scope of operations narrowing

D E V E L O P I N G R E P R E S S I O N

bl

° media: ° more severe clamp-down on reporting of military affairs

° counter-propaganda

° detentions and prosecutions

° likely call-up a; “Coloured" and Indian mer,

6 developmer.t of mo-e sophisticated weaponry

&the future

Economy: promoting war economy to prop up sagging economy will ultimately unb&lance it f'jrtht

Politicization/education 0 ne^d for united strategy in resisting cc-opt-ion

° need to plan ahead at a community level, tc be creative, take initiatives

0 w3y of approaching people is important need to show why rather than play on fears

0 spreading information:e.g. business involvement in military needs

to be exposed in SA

° possibilities of e.g. Bophuthatswana TV

Militarization

0 vigorous reporting in alternative coomunity and student press

° create awareness of civil war0

Conscription 0 deal with dc-Jbts ar.tl fear:

Role of the Church

HELL-BENT ON DESTABILISATION

South Africa and the Frontline States

Mike Evans

If we think, back ten year',, ar.d envisage a nap of Southern Africa, we see a very different p ;cture to the one we 3re used to today. In South Africa, the state had beer; ib‘e to crush all '-e^istance since the clamp-down of tf.. early sixties, and there v..-*s little indication of Uc- mass upheavals which would bsgin with the 1973 Durbar, strides, in Narribia, the *ar wricf had begun in 1966 hao only just advance tc a sccle w'ere South Africa was forced to introauce the SADF to conc.au trn? growing SWAPO activity.But even this activity was confinec to 1 relatively small portion cf the Caorivi. In Mozambique end Angola the v.b**s of independence were at ar. advanced stage; nevertheless, in the e*rly 7D’s the colonial govemn.er ts appeared to be in a strong enough position to at least contain the conflict' with FRELIMO and the MPLA. In Zimbabwe (then Rhodesia) the war only began in earnest in 1972, and Ian Smith was able to assert very confidently that never in his lifetime would there be black majority rule. Finally, the ELS countries (Botswana, Lesotho and Swaziland) were all favourably disposed to South Africa, and weren't even prepared to mount challenges to apartheid on a public level.

When we think of Southern Africa' today, then we realize how dramatically the scenario has changed in a relatively short space of time. What we need to ask ourselves then, is how has South Africa been affected by these changes? How, in turn, has South Africa responded to the dramatic changes of the past decade?

Factors influencing South African Policy in Southern Africa:

The most significant events influencing South African policy in Southern •— Africa have obvious^ been the coming to independence of Angola and

Mozambique in 1975, and Zimbabwe five years later. Not only did independent bring to power governments which were militantly opposed to apartheid, but also the policies of non-racialism and socialism which they expused poseo a longer-term threat to South Africa's hegemony in the region.More than that, Mozambique and Angola soon provided moral and material aid to the South African and Namibian liberation movements. There seers little doubt that the victories of FRELIMC, and the MPLA, aid the de.feat of the SADF in Angola in 197E-/6, provided massive encouragement to the students in 1976. Furthermore, soor, after irdepender.ee, A’-.gol- e l f red the way for SWAPO and ANC bjises to be established there. Today, Angola is the major training ground for Umkhontc --eSizwt and Pl.AN (Copies Liberation Army of Namibia) guerillas; arc together with Tanzania anc Zambia it provides tne most significant material assistance to the ANC.

Other external factors have had an important influence on South African policy. Most significant is the increasing non-Western involvement in Southern Africa, and support for the liberation movements; in particular, the Cuban presence in Angola - itself partly a response to SADF aggression - has also had an important bearing on South African policy-makers. More recently, the increasingly hostile attitude to South Africa of previously submissive frontline states (e.g. Lesotho) has influenced SA policy; so, too,- have the attempts at economic independence of these frontline states, as marked by the formation of the Southern African Development and Co-ordinating Conference (SADCC). *

Cut it is not only events outside SA which have changed SA foreign SlicJ. Internally, we've seer, in the last ten y e a r s the upsurge in

^ “M n ^ e ' i f C r l « ’• « leen thousand

ssorsrss: m ?as guerillas of the armed wing of the ANc, Unkhonto weSizwe.

South African Policy: Ergnomic Dependency

liberal international relations writers have often referred to the ’hawks' and the ‘doves* in the corridors of the foreign affairs department, me 'doves* are those who argue that South Africa must use its strong economic base to buy stability in the region, promote regional prosper.... and thus tope to weaken radical forces. The ‘hawks’ on the other hand, argue that South Africa should keep its neighdoun economical y and rniitirallv cowered; that the temptation on the frontline states tc see* e c o n o m i c assistance elsewhere should be weakened, and that whatever means

necessary should be used to achieve these ends. f

miH 7n'c th= nolicv of the 'doves' was dominant. This was S ’p S i S and co. regularly trotted off to the !voryCoast Senegal and whatever other African state would have them. Deter.e was the catch-word of South African foreign policy.

Obviously the intention was to intensify the economic dependence of Southern A f r i c a n states on SA and to varying degrees, SA has been successful in f r e a n q a n d maintaining these economic ties. This economic dependency h a s taken on a number of forms. Firstly. SA capital owns jr controls mu.h of the economies of some frontline stales, in particular Lesotho a

Secondly, many SADCC countries are dependent on SA for the import of'goods. The BLS countries aVI get over SOi of their imports frcm SA, while Zimbabwe and Malawi get over 40«.

The South African Customs Union is another way in which economic oependercy is maintained An agreement between South Africa and the countries

in this way, while Eotswan.. raises on^-third.

South Africa has also significant control oyer JJe transport networks of c Ac wpll a5 over the provision of electricity ana n>e(it has been said that SA could switch off all Lesotho and Swaz^lan s

lights in a second).

Finally although this is a diminishing factor, somefrontline states still rely oil the income generated by migrant workers. 40i of the Lesot workforce, for example, is employed in South Africa.

All these examoles indicate the network of SA economic influence which pervades throughout Southern Africa - a network which s substantia but very unequal, and one which has remained equally strong in the 70's and early 80's, despite the more aggressive SA foreign policy.

The Ttominance of the 'Hawks'

The turning ppint for South African policy in Southern A.nca was

independence of Angola in 197-• - Angola was, ano remains, the cr»- country r̂ the region which had virtually no economic ties, with Scuth Arrira. SA could rot, thererore, exe^t pressure on Angola as it could,say, or Mozambique which at that stage had also recently wcr, its independent f-or Portugal. In addition, the new MPIA government immediately prc-r.’.stci Strong support for SWAPO.

The rest of the stcry is well-known..... SADF troops movec in ir late ‘backing the dissident UNITA movement.... tney were hi'Id up at the Curve River just long enough for the MPL* to call on the Cubans for assistance

by early.1976, the SADF had been defeated and forced to retreat, with promised support from the ’Jest (particularly the USA) having beei withheld

at the last moment.

From this point onwards, SA began to rely increasingly on military and other forms of destabilisation, so as to maintain its position of rontrol in the Southern African region.. In the following seven years, a range of strategies have been employed: pressure by economic means, provocation in the form of border and airspace violations, campaigns of sabotage and terrorism, generally using surrogate forces portrayed as dissident movements of the countries affected, and commando raids. The final stage, so far reached only in the case rf Angola, is that of large-scale military offensives using conventional military formations.

In the remainder of this talk, I will look at some of these forms of destabilisation in a little more depth.

Continued Economic Pressure

While military aggression has dominated South Africa's destabilisation policy, economic pressure on neighbouring states has continued.PW Botha's (unsuccessful) attempts to form a ‘Constellation of States' have been aimed at breaking the moves towards greater economic independence on the part of the 9 SADCC countries (Angola, Mozambique, Zimbabwe,Tanzania, Zambia, Malawi and the BLS countries). Indeed, South Africa's attempts to give KaNgwane and Ingwwvuma to Swaziland, can be seen at least partly as an attempt to woo the conservative Swazi leadership to the constellation idea.

Zimbabwe has been hard hit by South Africa's destabilising intentions. Soon a*ter independence, SA terminated its preferential trade agreement with Zimbabwe. Then, late last year, 80 trucks and diesel engines carrying maize and fuel to Zimbabwe were withdrawn. At the same time, the fuel supply line from Beira in Mozambique, to Zimbabwe, was blown up by SA - backed terrorist forces. The result of this dual attack was massive fuel shortages during the packed holiday period.

Support for Terrorist Organisations

The Beira fuel-line attack is just one exampleof the way in which SA uses surrogate terrorist groupings to destabilise the frontline states.One of the'most significant of these is the Mozambique National Resistance Movement (MNR), originally formed by the Rhodesian SAS, but since 1 S3u' allenedly financed, armed and trained by the SADF at a base in the Eastern Transvaal, The MNR currently has a force of about 10 900, an.* during the last year it managed to cause severe damage in centra* ar.o Southern Mozambique. Howeve' major Ff>ELlM0 offensives during the first half of IM?. year hav ’ to n v :f^ sotbacks for the MNR. At the sam

time. South Africa has has come under strong attack for its backing of the MNR from such reputable bodies as the US State Department, and the influential London weekly, the Economist. SA government disclaimers regarding its backing of the MNR carry little weight. In Kay this year, the effective leader of the MNR, Orlando Christina, was killed in Pretoria. And two years ago, when MNR attacks on Cabora-Bassa led to power cuts in the Transvaal, PFP MP Graham McIntosh blam?d "some incompetent ass in th.- SADF or the National Intelligence Service".

Much publicity has been given recently to the allegedly South African- backed attacks on Lesotho by the so-called Lesotho Liberation Amy. Throughout 1981/82 each attack occurred within 2 km of the Lesotho/SA bolder, giving support to the theory that the LLA operates from the Eastern OFS. At one point PW Botha was quoted as saying that 'there wuuld be no LLA if you (Lesotho government) removed all refugees from Lesotho'. Clearly, SA is attempting to pressurise Lesotho to stop harbouring So-Jth Africar exiles.

The Mozambique and Lesotho'situations can be repeated for Ang:!:, Zimbabwe and even Zambia, where SA allegedly backea the dissident grouping led by Adamson Mushala. in Angola, SA does not even deny its active support for UNITA, while in Zimbabwe there is strong belief that SA is training 5 000 Mu2orev,a au iliaries. The death of 3 white SADF members during a mission in Southern Zimbabwe in August last year confirmed the SA presence in that country. It was this mission that led Robert Mugabe to remark that South Africa was "hell-bent on destabilisation".

C

Actions aimed directly at the ANC

Much South African action in Southern Africa has been aimed at breaking down support for the ANC and SWAkO. However, attacks on neighbouring states have often merely served to strengthen their resolve to back the ANC and SWAPO, for the frontline states more than anywhere else realise they themselves can only achieve true liberation when South Africa is liberated.

As a r e suHr’SA~has"ofteh~aimed its attacks directly at the ANC; for example, the SADF attacks on Touth African refugees in Matola in 1981, and in Maseru in 1982. The killing of refugees (as well as innocent civilians of the host countries^ has itself induced a change in strategy on the part of the ANC. Up till tnis year, the ANC attacks were directed only at economic tarqets and ley strategic installations. The Pretoria bomb blast is evidence of the fact that attacks will now be directed at military and police personnel as well.

Besides direct attacks, SA has also been involved in the surveillance of neighbouring states (the recent drone spy-plane over Mozambique,for example) and the kidnapping of South African exiles (three SA security policemcn were recently sentenced in Botswana for such activity). Far more insiduous is the alleged South African involvement in the assassinations of key ANC and SACTU personnel, such as Joe Gqabi in Harare in 1981, Petrus and Jabu fizima in Swaziland in 1982, and Ruth First in Maputo last year.

Full-scale Military Invasion

The final stage in South Africa's destabilising activities has only been reached in the occupation and complete destruction of much of Southern Angola.

m S«* has huge inf entry and , * £ « . [° f''" '

stele* pose n0 m n t a n > irMt -■' ^ ■• r.orclud.io tl.it t W S«? 5susro ere fighting gunr^l » “£ enU>l°y °n e.ter.ul « r ‘k* <;rce. for m .mass w e conventional orw> • - - - fhf invasion o1 otnercontinued invasion of Defence Wr.'ite Pape^ strcsse: tneSouthern African sta e|.. Th« , B D e f n c c ^ n , ^ W - t ^ .

U ™ ^ u c h as the O W a n t t a t t l e » * end the « 1 S 5 m gur a e su^ef for conventional rather than guenlU-type a.tacks.

r- .rront l\i stationed in Southern Aridola, and many cun ■=5 500 troops are c u r r e n t C e n t r a ' Angola it tne r.ea- future, anticipate a full sea 6 . i Keen enormous: many thousandTne cost of SA aggress.on a g a i n * ^ on d « e ?™intent,o?, has clearly dead, wounded or disabled, ano m u activity; traffic on the

r d s ^ r r e f n V ^ f T b r i b e s and railways bc.bed, and towns and vill.ges

reduced to rubble.

i ~ Houjctatp the entire region, b^eak down al ■The long-tem goals ^ the removal of all the Cubans presently

’? E 2 l I r . 2 ^ t l E 3 y . force the MPtA government to negotiate with

UN1TA.

■i**** nf artivitv in Southern Angola has been wh-

widespread^assecre of O g e e s ’ Aft/r the Kassinga attack in ,978.

Bishop Desmond tutu comnented.

-If South African forces could tell me U « « clear that they only attacked military targets, j would accept that. - ?"ev know it is not true. They have been eole to go ,n-u

' s k : . " - - " - *

S * « » t « S ! l = ...It is this continued onslaught that M S a’*°r5^ 1 ,r,e^Hest“rn S'lth-. (~)

- r ? « • - „

stopped, the iS. of i.ne pjoge^ J u i 11 ke CDoned. the minera; and

S S i S S S a S

Conclusion: The Destabilisation of Southern Africa

The picture presented in this talk has been rtws.

f f i B i * J K 2 K " *f n “^ " U S S w H c M r , destabilised by its neighbour, .

t H id: , ^ V . JfkP*

M°/3Pons on its border. What are thes^ sophisticated weapons

that the regime is referring to?

We do not represent a threat to anyone, r.eiJ'Jer . ^ 1^ arl1y n°r nn/vBirslIu No sensible person could think that an

» " d p 5 r country like our., with . 0 many wounds f war ctiii bleeding, could threaten the sovere'gity,

t e r r i t o r i a l integrity or stability of a n y state, espec-ally

a power like South Africa.

Vh^is'the^op^sticated^weapon^that'the regime refers to? Tie answer

H the work -e are doing. What is this work?

« • - 9 “»rth t? ^ " 4 U mr ^ p ”{ecUn9VtU.»1hdd ” t l £ ‘. f ^ U

of^affection'and peace^ as the ’g ^ n t S r . of future generations.

Tnis is what South Africa fee-s.

The sophisticated weapon is making the home the centre of ir* not, as in South Africa, a prison and a carded residence.

The sophisticated weapon is.having children ^

sector of our *°^ety]tk" Psu?rogt,ding children with love and affection,

? ™ 1 anS harness, and not, as in So«to. making them targets ,or .

police brutality and murderous weapons.

w s c a w s * r s s M a r A s a x J ir - ■

DEFENCE AMENDMENT AC i . 19a_3

- P ^ n r PROVISIONS RELATIW6J0 i a J 6 W L S § ^ I i g

Rn,.rri. for r e l i g i o ^ o ^ * ! 1— :

There may be one or more boaris for reUg'Ot* object'ion appoirted by the Minister of Manpower.

U There will consist of:

I ^ o ^ ^ H ^ o i t ^ r e S i - t i p n s

- 0ne military chaplain

: S I S H k s s b s s s -or chaplain are of that denomination

1.2 Rules for hearings:

- No legal representation- Witnesses allowed- All decisions final

1.3 Powers of the boards.

- Granting of #PP1 ?cat’0J* rips- Allocation to other categories- Refusal of applications- Referral to an exemption boc d- Reviewing of cases

1.4 Applications to boards need:

. 1 o be made in writing and sicred by applicant

: ?„ “f ^ a l W s r S l o r application

Tn state the "books of revelation and the• I n i c l " of faith upon which the r e l ^ o u s

convictions .“ppf ' su^p0rtirc witnesses

- To be*received1 by the days‘ If delivery of notice to render service

1 5 Applications can be made after a person has

started his servi.e.

Sec nor

/2M

72AC? :

72C(4)72B(2)(e)72D(5;

72D(t)(a) 720(1)(b) 72D(1)(c) 72D(2)f3)

72F

723

nf reliQiou^ ob'octor? provided for:Cn f°r0 ------ *--------------

7 ’ -a religious objector with whose religious 2 J convictions it is in conflict to render service

ir. a combatant capacity in any armed fo.ce.

Length:- Normal call-up

Type: Non-combatant duties in military uniform

Discipline: Normal SADF

2 . 2 ■ ■ religious objector with whose religious convictions it is in conflict to render service in a combatant ^in any amed force, to perfonn any maintenance tasks of combatant nature therein and to be clothed in a

military uniform."

Lenrjtn: One-and-?-half times each call-up

Type: Non-combatant duties in a non-military uniform

Rank: If an officer, reduction to the ranks

Refusal: Equivalt-.it prison sentence

. .. reli^ ouS objector with whose religious convictions it 2 - 3 H in conflict « render any niliUry service or M p e r f o m

any task in or in connection with any armed forc.ci.

Length: a) One-a**!-a-half times the full period of service owed, served continuously

b) For Section 44, periods equivalent to 1} time' call-up period; minimum 18 days

Type: a) "Community service” in Public Service or Municipal Service

b) Conditions of service laid down by State Preside:.t

c) No promotion, increases, etc., by employers for first two years where already employed in a category deemed 'comnunity service

d) No political activities other than those prescribed by the State President: voting i», election or referendum a right

e) No publication of written material relatirg to restricted activities

Refusal: Detention of equivalent length with parolepossibility

3 . Objectors not provided for:

All persons refusing to render service who do not fall into

the above categories.

Penalty: Imprisonment of one-and-a-half times lengthQf service owed or 18 months whichever is

longer

72D(lKa;(i)

72E(1)

7:d (»)'c )

(ii)

72E(2)

72D(4)

721(1)

72DH)U)(iii)

72f.(3) -

72E(4,

72G

72E(5)'c)

72H(1)

72H(2)(3)(4 )

721(2)(a)

126A(1)(a)

cosg factsheet —

2 500

2 000

1500

1 000

500defence spending

\

i

budget* Over the last 10 years the Oefenc* "

• Thi'/y'ear R3 092 700 000 was a l W a t e d I" O e t w t

• I t » a s ? £ e third-highest budgetted figure, ’he Departments of Constitutional D e v e l o p and F,nance took the biggest s l ' c e s o f t h e budge . lhp

* The 83/8^ Defence budget is up

t o - o p e r a t i o n and Development'was allocated Ri ,5

objectors

* In -he last 10 years 5 181 people havr been prosecuted

. r s a r ^ - s r ^ -to do training. «,«„». eniitarv confinemen;

* Two national servicemen were kept in solitaryfor two weeks during ’82 for refusing to wear

army browns. . ;aii tpntprc®* One man is presently serving year-long ja sente

in Pretoria Central Prison, and one in Pollsmoor.* Boards for religious objection have not ye.

(October '83) been established.

r

3t2

•

O 1

i963

196*4

SI

CHRONOLOGY of oppression

" ® " ^ T h e ^ e d i . commission, UCT, Caps lown . „£. f,-on . chronology prepared by the

r on Ka-ch 21. 6 0 oeople killed. Eleven people Willed at langa.

a t ® «- t ; : ; : ; : ; ; r : ; - 9e n . a , a . e 5tl o ^ 2 0 0 0 p e o p , . «

March 3 unlawful oroanisat ions.d PAC declared unlawtu 9 ,,rtr-l raoe Town in ant.-pass

, V „ 5 ,rh of ^ 0 0 0 0 into central tape PAC leader Phillip Koosana leads march o, 33

deronslrations. . ,lburt, „lth U CCO delegates »"d

• t o* design a "new non-raciel d e e c c n , c ™ i5es .w

- V 3 1 « - “ ;<l(kr,l i r ,. " h r ee f a r c e r s of

- - — ; h r r : " e ,r m k Am r ( **C fMf <s I V̂ * if i. I Hr N * » VChl.f * -1 U r t M I . President c the • . ^ ^ ,,, Congress

T he African . « * « ~ -hichn»ver«nt * »no serves a

■- th* ' * " 156 “ „ of th, «„C, Umkhonto «e Si— i*..' •* <heon M e m b e r .* «h. s ^ t a g e attack.

launches t e ^ ^ Suppression of Co-r.jnism Act.

C o n g r e s s of D e m o c r a t s a m - f v i0 le nce against vhiteThe PAC t n m d Poqc (Pure) engages .. random ac.s

civilians and black po icemen. e „ ba,-ks on a sabotag.

The African Resistance Movement c o m p o s e d ma.nly

campaign. arrest. Rioting at Cato Manor aga.nst po'- ce

Hclen Joseph first person unde, hous

raids. Quickly apprehended after acts of v o en.e.PAC/Poqo leaders lacking o r g a n ,sat■on. qu,ck!y

Eleven hanged. tends members

„ „ „ , ace5 blanket han on all Panned and listed persons.

abroad to establish a external m.ss.o ^ ^ ^ ^ corTTT̂ nd members

Motsoaledi sentence , . escape.

Goldrech, „ arreste, and put on trl.l -l«h .J others.

Braam [ischer. SACP 'eade . , r,osto0 and tried for sabotage.

Many members of U m k ^ n r o Pogo an A . « . r ™ ^ 0 ‘ too state.

1 6 0 “ people are conv.cteo ^ executed.

Three prominent SACTU trade un.on.sts ___________ ^

1965

1966

Three prominent ,round. A,retted

Braair. P l s c ^ r > « > of l i fe" impri lor-r.ent for

eleven months latei , he. . __ Va n c

SUAPO launches its first guerrila operations.

, f A J L u t h u l M * ki.Hetf in an accident on July 21.

C * 1 1 tarv a l l i a n c e w i t h ZAPU andthe 'Luthuli eonbit detachment

S£3 H s r & .s : s t w - — *• souih‘

i*p!SiSSi .

s w s y 'son piece of soap . i (

“

s * *»“r̂ x;̂ roU« J « . u i “g l * « °f th£ BUck Consciousness novement.

u-t • _ tK, ANC at the horogoro Conference In Tanzania *bere strategy Kajor policy sb, ts .n the sitoation were adopled. AHC becomes a non-rac.al

m a s s - b « l“ r e v o l u t i o n ^ organisation incorporating coloureds, indians and de»o-

cratic whites.

22 people including Sarnson Ndou tK e J e a d i n g ^ c c u s e d ^ a n d Mrs^Vlnnie

^ ; K d^ rc ^ r ^ e d and re-applied but all arc acquitted 19 receive

banning orders. sente,cc for taWing part In Terrorist Activities.

k k i : - i i T c 1,..- * — - . ;:s; ^ ; : ;;-st.n d 5 t m , . itrl*

2 0 0 0 0 K a l i a n contract . r j e r s b . ^ ^ control.

against tne sy Anniversary celebrations of the Republic.

NUSAS S h e o i t o ^ i l e b ' r a t i o n s . -SASO and the Black Sasn rfVnru,n ltv result in major clashes withPort Elizabeth bus b o y c o t t ^ the^coloured c o ^ n l t y

the police. ' K ear i8 n sentence forJ « . April, a coloured student at U.C.T., r e e v e s a 15 ,e.r Ja

membership of Um*bonto. _ s,udents in schools.Sou,h African Students c e m e n t formed to organise bl.ck « u d ̂ ^

, 0 0 0 0 0 -orkjr, in D u r b a n ^ « ”|I " i o s , ly spontaneous bu. proved

to development o. independent black trade of rREL.H0.

^ ^ i c u e .cbi.ves independence - ^ c ,.shes uith p o H c e

SASO oroanises rallies uu

“,ae,v — >• —

rz::;«!»«... * -— — - 1 -miles a oay to and from work.

South Africa invades the Peoples Republic of Angrl-. _ furlheri»»i the

Several security trials including white democrats and * « « »_•___ r * autaims of the ANC

,i977

c

s 1978

o1979

•J

rft-'F r c i r f a t i 'n'.o

. , <|Icf. iOT ».-e » lr .<

g ^ . o students P - ' ^ ^ U n ! " ^ - i - ^ " l ^ t N h , •O n J u n e to n a t i o n w i d e u p r i s i n g ° U n r e s t c o n t i n u e s t* ^

- s « 5 - »— *"t he c o u n t r y . A N - P*

s t u d e n t ' £ s t r u g g l e .

S U report.- Incidents 000 students. The « « or9* "“" **“ "

^ s m i u onionist lauren„ -

J - . S in d e t e n t i o n on *ep

« r ; ' « s « ' d i . I- d ' ' ' n i l°;e „ i p a p e r i , * » r » « «

it organisations * 2 ' ! ! t . orgnnl » * t o n > a re banne M n t r |,l» take P ' - «

Christian re« l v e banning orders. *>

,re d e t a m e K t |vitles.

„ U t l n g to » „ „, sabotage- 5 c uth«rn M g o l

r r : »-•: - - r r r •» “ ~ - .... . -, , l l v I n Q »n L'0>> ,

»° 000 ( - - n l n0t ”°',e'' „,r*cy to overthrow th. state. 5,. rrjlogan | ,„ A«: conspiracy

12 people Ch.r9e d . th be ^ ^ < * *'_ the

‘" ’“T e r , r.vih, 10 Crossroads resist « . « - ( t d ,t Hodderda- ....

JO 0 0 6 (we - M t ootrcve->.

slog*" ' V ' ^ v . i U t ll4u ' « r »»i r '', W " 'Unibe'l •" ,577- .ve CoJnoli tried

So-ete Studf ‘S, * T r ^ 3 to 7 years. ________

sentences 9 * of sabo.agr■ „,nv;c ted under the Terror!.

Ihlrty-t-o repj „ e c u t e d after be'1?* ' J0 OCO peep =• 1 1 , Soloecn hahlangu s « ' c h i n s e H fir.ng a shot.

AHC guerrilla t shooting w.tnoJtAct a f t e r the Goch S t ree l r e a son. M M o o f

I - . r ; trial of E * r e c e d e d death

- -for planning c^ri »nd Canning

Robert t K „ i , called by £ solidarity -Ith

^ “ ' U ^ v e s - ^ P P O t t ^ M t theif d e m a n d s . ^ ^ ire

.n r s t i n t s t.r ;^ rtr^ . !tu‘eMs

_ , , lh incftas,n 9 - u n d i r e c t e d - <

Umkhonto guerrilla rsllway lines. T-enty six P celebrated.

5och a, police s t a r , o n ” gp of he Freedom b,

Twenty-Fifth .nn.versary fr„ Bandela Campaign.

S r hS u X ”o\r;«:.-,ve, 79 »00 signatures. .

ten, of " °' *"I n f e r i o r r a c i s t g u t t e r

I960

„r raids into Angola In o r c-ation, Snokeshell and Sceptic.

“ “ r

i‘i:s .s?’cratit representation.

° ^ n i 3pi«i!d‘ntNo°y 1 ™ ion'o! ' ̂ ' . s l ^ t a ' S U I T s i T w o H ^ g n u f o n

as, a symbol of the s t r u g g le .« C guerrl U a a t t a c h uscalate. Targets include police station, ,« Sooysens and

Soekmekuor. SASOl refioer.es sabotaged.

800 s t r iking meat workers in C ape T o w n r e c eive support from the c o r m - n . t y w a n »

red neat boycott.,0 oco Johannesburg aunlcipal workers strike .or improve* cond.t.ons and recog -

tion of their unregistered union BMVU. ;

b l a ^ ' ^ n ' p l ' c l T n s t i n g s .

!5.«,w ,M rK S£.TTS s ^ i r a - i y r s = • •L ib erat io n .Finhteen reported Incidents of sabotage.

S A W c o » » n d o raids Horambioue and assasinates 12 ANC members and kidnaps 3 others

it Matola, a suburb of Haputo.SADF raids southern Angola in opperation Prot.a leaving large -scale destruction

Trtd^Uniolitrlld'collln'ity Leader Oscar Hpetha and .7 others are put on trial

on charges of terrorism and attempted murder.joe Gouabi, leading ANC activist, assinated in Zimbabwe.joe usuo , _ In Durbar, militant

real's tance^s^own5 to'rent* increases conditions' in community struggl

X " c sAntl-SA.C boycott and demonstrations receive wide support and back-up by

sabotage. The people decisively reject durr-y councils.

Twenty-seven reported incidents of sabotage. .

,9 8 1 / 8 2 lacreasing unity onves within the traoe union movement.

Kassive state security clamp down and hundreds of activists detained n a t .onw.de.

a t a nionist Nell Agcett and detainee Ernest Cipeie die. in dt.ter.. o.i.1932 Trade un.onlst Hell * 9 $ ^ £ reprass5on.

20 000 African mine workers sttkc on the ra . . . . .

A * activists Petros and Jabu Nzima esslnated by car bombs in Swaz.lanu.

Professor Kuth First, academic and activist, assinated b, letterbomt in Maputu.

,361

t ce„tMaterial published on militarisation in Southern Africa.

r ^ i p n t i o u s Ob.ierMnn: Occasional Paper No.Jj, Centre for Intergroup

Studies, Cape Town, 1983

2. 6 Evans, "SADF and Civic Action" in H o H ^ P r O £ r e s s _ 2 8 and Vork

in Progress 29

3. SA Outlook Mcy 1983 "Destabilisation and the Church’'

4. SA Outlook August 1983 "Destabilisation without and within"

’ containing a reprint fro. the .Economist entitled “Destabilisation in

Southern Africa"

5. south African Review: Same Foundation, New Faca_oes, Ravan Press

Johannesburg 1983. Articles on "Military policy and the Namibian

dispute" and "Restructuring: the role of the military in Section 1

6. T Weaver, "Caught in the crossfire: the war in Namibia" in

Work in Progress 29

ID£AS AND ISSUES FOR fURTHER WORK

1. Combatting militarization

* C.A.P.r Annscor, and other influences in society.

* military influence in schools.* the role of the SADF.* di'cussion of the SACC propose aritation* exploration of the global dimensions of militarisation.

t

2. Conscientious Objection

: 1 \ . heresy for just war theorists?

* Continued action on the legislation.

: £ & * objectors.* Continue the debate about universal/select.ve objection.

» Explore refusals to register.

3. Active Peacemaking

* Apart fro. combatti.., militarisation, establish clear alternative actio-,.

A. The Church

* Rcle in Boards for Religious Object'cr.* participation in chaolaiHcy se*-vnccs f >b or. the borcrr’..* Programmes of support for NSM, i n d u i n g p o f -

5, Odds and Ends

* Focus on cadets an" inform about Section S7 which parents can invoke

to stop their children from participation.

UAYS OF TAKING UP THE MILITARY ISSUE W O N G ST YOUNG HOPIE

* Establish personal contacts.* Provide an alternative to veld schcnls.

: ^ ^ " ^ e M ^ o ' t h e present Youth Preparedness manual.

i 5 3 H r e n = r B^ = s t i t o e n c ,

' Ske"fonU cr»U hy0thebe 5 i m i L l faculties of Universities* include information in Church syllabi for fomation/membership.

* Arrange workshops and camps.

r

lir..,-trrr ][}v AC awn SUGGEST I DNS. FCR_ALu£:

„ f f ---------------

wh4t, wiil

" s issue should he d e . U with prior to conscnptu . -

riarifving include.need c»ariTj y rfj r^rt i d patino

T 1 x r . r f-O U “ * 1 T.V d P u p c » w v k Ko..,opr + K-' feminist call .or equ- ■*.

* differentiating be^woe .

. r : " ; « « - « - » « * « • • ^

■ v s s s s s . ■ ? » « " “ ' - ......

2 The present military conflict ,

Focus on:

Of Children on both sides of the civil war..

* m0tne'S d the pressures on thar. to support tren in

’ ^ r 0^1 flsl5focusyon"thfsexual' violence which appears to result

Rising militarisation.

rnninc with families while fathers are in SADF.* wcr.en coping wi tn »o ehifts

,pr 5tress as a result of the personality shitts . families which are under stress

caused by military service.

G

3.Particular ideas.:

: sssrs s u f f c r i " 9 ar,d, rhalleno^medi ̂ images of women . Jork with women and not through men.

CONSCRIPTION AND MILITARISATION

Discussion points and programme ideas:Discussion points anu “ s includes* veld schools,

• ̂ s g s x a s s ^ ' i ^ ’ ■“

. - - - - — • -

penalties., .. thp crate to conscript peopie.

. Question tne .oral authority of the ^ ^

• explore the possibility of refusi. to regut..r j

'coloureds* c.r.J ,nui3ns.

. fnnfcrintion is 'needed' - unjust society, internal

* Ft°„Cre!t°nco”p?io.Woyf certain groups in society.

. [xp,ore the possibilities of incorporating a focus on homeland — s. -

. Kake use of future CO trials to raise the issue of conscnption.

. Reiate to other organisations such as NEUSA. When's Hove»ent for Peace.

. End ,n9 conscription would end ^itarisation - this would need to

be made clear.

. The necessity of -king .oral judgments about the conflict an. a ou

violence would remain.

. txplore the relationship with international . e v e n t s and with peace c « . 9-

• use all possible opportunities to ra,se these issues.

• Explore conscription in other civ*' war and nsticnal situation..

• Analyse other campaigns and use methods i,ready tried.

• Arrange workshops, petitions, etc.

THE DEFENCE AKENDMENT_ACT Ufa

Ideas for action:

1 . participation in Boards: .

* inUseparate°resourcesC (cf Roufand

Commission).

• Should this strategy not be P° s 1 1 11 This person

2 rnrrmmity Service.

’ * W K r r » ,fW .U ^ .Two options were sudge.»ted.

: appearing°beforerthef Boa rd^but* ref using to sen,e the prescribed

■ , ^ I ’tion to the length of c a n i t y service, it was possible to sen-e

* IS aoreed length and t i n refuse as a protest.

3. Gaol Sentence: rvice

. It was pointed out that U I b’S ^ s ”this was only a maximum of 3 years, oecre »

Collection Number: AK2117 DELMAS TREASON TRIAL 1985 - 1989 PUBLISHER: Publisher:-Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand Location:-Johannesburg ©2012

LEGAL NOTICES:

Copyright Notice: All materials on the Historical Papers website are protected by South African copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, or otherwise published in any format, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner.

Disclaimer and Terms of Use: Provided that you maintain all copyright and other notices contained therein, you may download material (one machine readable copy and one print copy per page) for your personal and/or educational non-commercial use only.

People using these records relating to the archives of Historical Papers, The Library, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, are reminded that such records sometimes contain material which is uncorroborated, inaccurate, distorted or untrue. While these digital records are true facsimiles of the collection records and the information contained herein is obtained from sources believed to be accurate and reliable, Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand has not independently verified their content. Consequently, the University is not responsible for any errors or omissions and excludes any and all liability for any errors in or omissions from the information on the website or any related information on third party websites accessible from this website.

This document is part of a private collection deposited with Historical Papers at The University of the Witwatersrand.