Report of NEFSALF first meeting for...

Transcript of Report of NEFSALF first meeting for...

NEFSALF Bulletin September 2010 1

Report of NEFSALF first meeting for 2010Report of NEFSALF first meeting for 2010

Issue No. 13 September 2010

for collaboration among participants from government, community, market, knowledge and civic sectorsCity and environs agriculture and livestock keeping enhance urban food security and improve the well-being, income, skill and knowledge of those who practice it.

Continued on pg 2

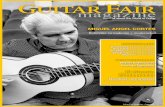

The NEFSALF fi rst meeting for 2010 was held on 15th July at Mazingira Institute. The meeting brought to-gether about eighty participants from various sectors of NEFSALF. A team of fi ve Canadians from Rooftops Canada/Abri International on a study visit to Kenya were among the participants.

The meeting consisted of two sessions. The fi rst session, among other things, was devoted to presentation and discussion of reports, which included: • Update on urban and peri-urban agriculture and

livestock (UPAL) policy, by Albin Sang, Deputy Director, Extension Services, Ministry of Livestock Development.

• World Food Summit, by Davinder Lamba and Kuria Gathuru.

• Post-training visits, by Deborah Gathu.• Africa – Toronto exchange visit, by Brad Lester and

Kuria Gathuru.• Crypto Campaign with small dairy farmers in

Dagoretti, by Prof. Erastus Ngethe.

The second session was for NEFSALF Farmers Network to address their specifi c business. There was also a dis-play of a variety of products that the farmers are begin-ing to market.

The Bulletin collates the presentations delivered at the meeting.

Update on urban and peri-urban agriculture and livestock (UPAL) policyPolicy processThe Draft formulation process entailed discussions with interest groups such as Kenya Agricultural Research Institute (KARI), Mazingira Institute, Nairobi City Council, Provincial Director of Agriculture (PDA), among others. Different stakeholders identifi ed vari-ous policy concerns and developed concept papers based on the same. These views were used to devel-op draft policy documents after holding consultation workshops with various stakeholders. The major play-ers in this process have been representatives from the Ministries of Agriculture, Livestock Development, Local Government, Public Health and Social Services, Kenya Agricultural Research Institute (KARI) and rep-resentatives from the NEFSALF forum.

Intense consultations have resulted to development of a zero draft UPAL policy which is waiting cabinet ap-proval after which it shall be published and launched, followed by development of a legal framework, imple-mentation and fi nally review of the policy.

OverviewChapter one introduces the draft by reviewing the state and impact of urbanization in the world and in the sub-Sahara African region. Also reported is the current status in policy, legal and regulatory framework; environmen-tal pollution; technology development and dissemina-tion of information; markets and marketing; safety of agricultural produce and products as well as land use.

Chapter two covers the objectives of the policy (both broad and specifi c). The broad objectives underscore the higher level objective and sector contribution to nation-al goals. On the other hand, specifi c objectives focus on the thrust of thematic areas. Chapter three addresses pol-icy constraints to sub-sector performance and proposes intervention measures to address the constraints in each thematic areas: policy, legal and regulatory framework; environmental pollution; crop and livestock produc-tion; technology development and dissemination; mar-kets and marketing; safety of agricultural produce and products; land use; provision of support services; gen-

der; and HIV/AIDS. Findings of studies on waste wa-ter, pollution along Nairobi river, lead and heavy metals on food grown along roads and milk contamination are also reported in this section of the draft. Chapter four introduces the institutional stakeholders involved in the UPAL activities.

Chapter fi ve proposes institutional arrangement for co-ordination of UPAL development. These are: national UPAL steering committees; UPAL coordinating com-mittee; and municipal and town council agriculture and livestock committees. Chapter six outlines review, mon-itoring and evaluation of policy implementation; roles of institutions; and an implementation framework.

The current status of the draft UPAL policy is the on-go-ing discussion and consultation on a zero draft amongst the afore mentioned stakeholders as well as emerging ones. The team is also working on identifi cation of pol-icy concerns and development of concept papers. The fi rst stakeholder workshop was held at KARI headquar-

Albin Sang, the Deputy Director, Extension Services in the Ministry of Livestock Development addressing participants on UPAL policy progress. To his right are Davinder Lamba, NEFSALF Coordinator, Peris Mugo, Nairobi Provincial Livestock Extension Coordinator and Brad Lester, Rooftops Canada.

Pho

tos:

Maz

ingi

ra li

brar

y

NEFSALF Bulletin September 20102

Continued from pg 1

BackgroundThe Food & Agriculture Organization (FAO) hosted the World Summit on Food Security in Rome, Italy, 16-18 November 2009, in order to keep the challenge of food insecurity on top of the international agenda. The over-all purpose of the Summit was to agree on key actions to tackle the global food crisis.

Food insecurity all over the world has worsened over the last three decades. In 2009, the number of people living in hunger and malnutrition short up above the one billion mark for the fi rst time in human history. Eighty percent of these hungry people are food produc-ers themselves, many affected by harsh weather patterns due to the effects of climate change. Another two billion are suffering from malnutrition, yet about one billion worldwide are obese.

This situation is also as a result of twenty-fi ve years of ill-advised international and national public policies such as structural adjustment, trade liberalization, con-ditioned renegotiation of the foreign debt, and reduc-tion of support for and investment in small scale agri-culture in the global South. Such policies have led to the massive eviction of peasants, indigenous peoples, pastoralists and fi sherfolk, among others—destroying their livelihood as well as hindering their access to land and other productive resources. At the same time, these global policies have severely hindered the capacity of States to regulate their national policies, interfering with their capacity to promote food sovereignty and protect the Right to Food and to produce food.

Some powerful developed countries attempted to lim-it the mandate of the Food Agriculture Organization (FAO) and to reduce the importance of the Committee on World Food Security (CFS), or even eliminate it. The situation exploded in 2007 in the so-called “food crisis” sparked off by the combined pressure of increased oil prices, fi nancial speculation in food commodities, strong investment in the production of agro-fuels and, most re-cently, through land grabbing by richer states and corpo-rations. The aggravation of food insecurity in 2007 and 2008, accompanied by social mobilization throughout the world, changed the political situation and has led to a number of new initiatives at global level.

Caucuses and thematic working groupsThree caucuses consisting of women, indigenous peo-ples and youth -- plus a working group on alliances, met to discuss issues affecting them. Later, each of these came up with declarations and for the next two days these groups dispersed into four thematic sessions to address the following questions:• Who decides about food and agriculture? • Who controls food producing resources?• How is food produced? and • Who has and needs access to food?

Who has and needs access to food?Davinder Lamba, HIC President, who is also the Executive Director of Mazingira Institute, represented

the urban poor constituency in the Steering Committee. He prepared the draft paper for discussion and also chaired the working group. He explained that those in need of food are from the South and the poorer pockets in the North. Many of these are small scale farmers in urban and peri-urban areas because of rising urbaniza-tion rates.

This Working Group formulated proposals in regard to: food security, urbanization and the right to the city; food security in war-torn confl ict zones and occupied terri-tories; the global food security crisis and low-income and food-defi cit countries, including small island states; food security and urban and peri-urban agriculture; and food security for the urban and rural disadvantaged, and for vulnerable people and areas.

How is food produced?The group’s major concern was on how to move to-wards an ecological model of food provision that sup-ports and implements food sovereignty through provi-sion of suffi cient healthy food in localized food systems, while at the same time, cooling the planet. The group was against industrial crop and livestock production and intensive fi sheries, with their associated process-ing, global distribution and retailing. It was noted that the corporate model was behind the campaign for a new Green Revolution promoted by AGRA, CAADEP and other initiatives as well as the dragging of small-scale food providers into the global market through enhancing ’Value Chains’. The group supported ecological food provision at a smaller scale, which is people-centered --with both women and men having decisive roles. This model of production cannot be appropriated or ‘owned’ by an individual, but is responsive to democratic de-mands and respects collective rights.

Possible actions arrived at included: strengthening ur-ban food production and small-scale producer move-ments; reclaiming the language of (healthy) food and regaining control of nutrition – changing diets, ‘eat less meat’; reframing research in a more inclusive and participatory manner; engaging with local and national institutions in reducing distances between food provid-ers and consumers; to promote local and organic pro-curement and availability of food; and to promote local farmers as well as markets.

Who decides about food and agriculture?This group was of the view that those who decide food and agriculture policies are central to ending hunger. They proposed the need for an authoritative global policy forum that could signifi cantly strengthen the prospects of achieving bottom-up change, by “disciplin-ing” those who act against the Right to Food and food sovereignty at global level and rewarding governments who fulfi ll their commitments. The group also suggest-ed those decisions regarding the allocation of fi nancial resources for food and agriculture to be controlled by the Commitee on Food Security (CFS) and not by donor countries and / or the Word Bank.

Who controls food producing resources?Access to and control over land, water and agricultural biodiversity is getting increasingly concentrated in a few hands, with serious implications for the availability of precious natural wealth for food provision by local communities and societies at large. The working group then set out to identify key drivers and trends behind the concentration of food producing resources and to dis-cuss possible actions and alternatives to face this threat, guaranteeing the rights to food production resources of local communities, as a pre-condition to the Right to Food and food sovereignty.

Landlessness and land grabbing have intensifi ed in the wake of the global food crisis, deforestation, sequester-ing of water bodies, inland waters and coastal zones. Forced evictions and displacement of local communities to pave way for industrial agriculture, plantations, large infrastructure projects, tourism and luxury recreation have become commonplace in many parts of the world and especially in the developing countries. Since 2008, a new trend is sweeping the world, whereby countries and companies are buying or leasing farmland abroad to secure food supplies or just to make money. For ex-ample, in Kenya there have been attempts by foreign companies to buy land for growing sugarcane along the Tana River, as well as biofuels and other crops.

Fresh water consumption worldwide has more than dou-bled since the 1940s to nearly 4,000 cubic kilometers annually and is set to rise another 25 percent by 2030. Up to three times that amount is said to be available for human use, but waste, climate change, and pollution have left clean water supplies running short. Water is becoming commodifi ed and privatized, and often times diverted to other uses than sustaining life, ensuring health and hygiene, and producing food. The depletion of water hits women and girls the hardest, since they are often the ones in charge of supplying water to their households in poor countries.

Declaration from social movements /NGOs/CSOs We, 642 persons coming from 93 countries and repre-senting 450 organizations of peasant and family farm-ers, small scale fi sher folk, pastoralists, indigenous peoples, youth, women, the urban people, agricultural workers, local and international NGOs, and other social actors, gathered in Rome from the 13 -17 of November, 2009 united in our determination to work for and demand food sovereignty in a moment in which the growing numbers of the hungry has surpassed the one billion mark. Food sovereignty is the real solution to the tragedy of hunger in our world.

Food sovereignty entails transforming the current food system to ensure that those who produce foods have eq-uitable access to, and control over, land, water, seeds, fi sheries and agricultural biodiversity. All people have a right and responsibility to participate in deciding how food is produced and distributed. Governments must re-spect, protect and fulfi ll the Right to Food as the right to adequate, available, accessible, culturally acceptable and nutritious food.

ters, Nairobi on 15th June 2010. Further changes shall be effected on the zero draft based on inputs from vari-ous stakeholders during this meeting.

Discussions drawn from this presentation expressed concern over the unwillingness of the Nairobi City Council in the development of the UPAL policy. The Forum noted with concern of their absenteeism in vari-ous fora despite having been invited. For example, de-spite personal delivery of an invitation to their offi ces, they did not send a representative to this forum. Creation of an agricultural department within the Nairobi City Council came out as one suggestion to ensure adequate representation. UPAL policy aims at equipping farmers within the urban settlement with informed farming prac-tices suitable for urban areas.

World Food Summit

Participants at a panel session during the CSO Forum at the World Food Summit.

A group discussion at the forum where a presentation on NEFSALF was made.

Continued on pg 3

NEFSALF Bulletin September 2010 3

Governments have obligations to provide emergency aid. But this must not undermine food sovereignty and human rights. Emergency aid should be procured as lo-cally as possible and must not be used to pressure coun-tries into accepting Genetically Modifi ed Organisms (GMO). Food must never be used as a political weapon.

We call attention to the violations of rights of people, urban and rural, living in areas under armed confl ict or occupation and in emergency situations. The inter-national community must urgently address violations of human rights like those related to forced displacement, confi scation and alien exploitation of property, land, and other productive resources, demographic manipu-lation and population transfers.

Who Decides?We declare our support for the renewed Committee on World Food Security: We take particular note of the com-mitment those Heads of State present at the FAO Summit have shown to this important body in their Declaration. We emphasize the fundamental importance of the re-newed CFS as the foremost inclusive international pol-icy body for food and agriculture within the UN system, and as an essential body where the knowledge and per-spectives of those whose daily labours have fed human-ity for generations are not only heard, but also acted upon. We assert the centrality of the Right to Food as a principle to guide all elements of the Committee on World Food Security’s work.

We express concern that the CFS is not receiving the funding appropriate to the ambition of its work pro-gramme. We urge FAO member states to back their political commitment with fi nancial resources. We also note that much work remains to be done within the CFS to ensure that there is coherence between the different organs of the global food and agricultural institutional architecture. In this regard, we are extremely concerned by the proposed World Bank Global Agriculture and Food Security programme whose governance mecha-nism appears undemocratic, untransparent, and des-tined to lead to a replication of past mistakes. As long as institutions such as the WTO continue to privilege com-mercial interests over the globally marginalized and malnourished, hunger will continue to stalk the world.

Civil society has played a fundamentally important role in the CFS reform process, opening up a critical space which we intend to fully occupy in a responsible and ef-fective manner. In so doing we will ensure that the voices of the excluded continue to be heard at the heart of food and agricultural policy-making and governance, at all levels. However, whilst we value the work that has been done, and hold high expectations regarding the CFS’s future achievements, we will vigilantly monitor its work to ensure that member states follow through on their commitment to create an effective mechanism that is strong in its powers of coordination at all levels; able to hold its members to account; and start now to realize its commitment to develop a Global Strategic Framework for food security and nutrition.

Ecological Food ProvisionWe reaffi rm that our ecological food provision actually feeds the large majority of people all over the world in both rural and urban areas (more than 75%). Our prac-tices focus on food for people not profi t for corporations. It is healthy, diverse, localized and cools the planet.

We commit to strengthen and promote our ecologi-cal model of food provision in the framework of food sovereignty that feeds all populations including those in marginal zones like small islands and coastal areas. Our practices, because they prioritize feeding people locally, minimize waste and losses of food and do not create the damage caused by industrial production sys-tems. Peasant agriculture is resilient and can adapt to and mitigate climate change. We insist, however, that food and agriculture be kept out of the carbon market.

We will defend and develop our agricultural, fi sheries and animal biodiversity in the face of the aggressive

commodifi cation of nature, food and knowledge that is being facilitated by the ‘new Green Revolutions’. We call for a global moratorium on GMOs. Governments must protect and properly regulate domestic food mar-kets. Our practices require supply management policies in order to secure availability of food and to guarantee decent wages and fair prices. We are ready to discuss new legal frameworks to support our practices.

We call for a reframing of research, using participatory methods that will support our ecological model of food provision. We are the innovators building on our knowl-edge and skills. We rehabilitate local seeds systems and livestock breeds and fi sh/aquatic species for a changing climate. We commit to promoting the fi ndings of IAASTD (International Assessment of Agricultural Knowledge, Science and Technology for Development). We call for accountability by researchers. We reject corporations’ control of research and will not engage in forums that are dominated by them. We will promote our innova-tions through our media and outreach programmes for capacity building, education and information dissemi-nation.

We will strengthen our interconnecting rural - urban food webs. We will build alliances within a Complex Alimentarius - linking small-scale food providers, pro-cessors, scientists, institutions, consumers - to replace the reductionist approach of the Codex Alimentarius. We commit to shortening distances between food pro-vider and consumer. We will strengthen urban food movementsand advance urban and peri-urban agricul-ture. We will reclaim the language of food, emphasizing nutrition and diversity in diets that exclude meat pro-vided from industrial systems.

Control over food producing resources Land grabbing by transnational capital must stop. Landlessness and land grabbing have intensifi ed in the wake of the global food crisis, deforestation, seques-tering of water bodies, privatization of the sea, inland waters and coastal zones. Land and water confi sca-tion and isolation practiced by occupying forces must be stopped. Countries and companies are colluding in alarming land grabbing practices. In less than a year, over 40 million hectares of fertile land in Africa, Asia, Latin America and Eastern Europe have been usurped through these deals, displacing local food production for export interests.

Instead of promoting large-scale industrial agricultural investments, we urge our governments and the FAO to implement structural changes implied in the Declaration of the International Conference on Agrarian Reform and Rural Development (ICARRD) and in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The International Planning Committee for Food Sovereignty (IPC) must play a critical role in ensuring the effective participation of social movements and civil society or-ganizations.

We demand comprehensive agrarian reforms which up-hold the individual and collective/community rights of access to and control over territories. All States must implement effective public policies which guarantee community (those who derive their livelihood) con-trol over all natural resources. Strong accountability mechanisms to redress violations of these rights need to be in place. Gender equity and the youth interests must be at the heart of genuine agrarian and aquatic re-forms. Reforms should guarantee women and youth full equality of opportunities and rights to land and natural wealth, and redress historical and ongoing discrimina-tion.

Access to water is a human right. Water must remain in the “commons” and not be subject to market mecha-nisms of use and governance. Aquatic reforms should give legal recognition, protection and enforcement of the collective rights of small-scale fi shing communities to access and use of fi shing grounds and maritime re-sources.

Closure of pastoralists’ routes and expropriation of lands, natural wealth and territories from local commu-nities through economic concessions, big plantations, industrial agriculture and aquaculture, tourism and in-frastructure projects and any other means must come to an end.

Gathered food is also an important source to feed many of our communities and therefore deserves specifi c pro-tection.

The rights to territory for indigenous peoples encom-pass nature as a living being essential to the identity and culture of particular communities or peoples. As guar-anteed by Articles 41 and 42 of the UN Declaration on Indigenous Peoples Rights, we call on FAO to adopt a policy for Indigenous Peoples, to recognize Indigenous Peoples’ Territorial Rights, and to ensure their partici-pation in resource decisions. We urge FAO and IFAD to create a Working Group with Indigenous Peoples in the CFS.

We reject intellectual property rights over living re-sources including seeds, plants and animals. De facto biological monopolies –where the seed or breed is ren-dered sterile – must be banned. We will keep the seeds in our hands. We will keep freely exchanging and saving our seeds and breeds. We value our traditional knowl-edge as fi shers, livestock keepers, indigenous peoples and peasants and we will further develop it to be able to feed our communities in a sustainable way. Our songs and tales express our cosmic vision and are important to maintain our spiritual relationship with our lands.

Civil Society CommitmentsWe commit ourselves to increase our level of organi-zation, build broad and strong alliances and promote joint actions, articulations, exchanges, and solidarity, to speak with a strong voice for defending our food sovereignty. We are convinced that only the power of organized peoples and mobilization can achieve the needed changes, thus our principal task is to inform, raise awareness, debate, organize and mobilize people.

Women participants in the forum, noting the systematic oppression of women through the processes of global-ization and corporatization of agriculture, fi sheries and livestock, intensifi ed by patriarchy, commit ourselves to achieving equality in representation and decision mak-ing bodies. We demand gender justice, peace and re-spect for the rights of women, including common prop-erty rights. Our rights over seeds, productive resources, our knowledge and our contributions to enhancing resil-ience must be respected, valued and protected. Women agricultural workers and their communities must be as-sured safe working conditions and fair wages.

Youth participants of the forum reaffi rm that young peo-ple are key to the development and implementation of ecologically and socially sustainable agriculture poli-cies. All decision making bodies must ensure the effective participation of young people. We insist on agricultural, fi sheries and livestock education (formal and informal) from an early age, and the FAO and IFAD should pro-vide adequate funds for capacity building training at all levels to address the needs of young people and rural women. Our commitment to food sovereignty includes a demand that the Committee on Food Security be trans-formed into the “Committee for Food Sovereignty” and a call for a moratorium on agrofuels.

We engage ourselves to collectively accept our respon-sibilities to mobilize from the local to the international levels in our struggles for food sovereignty. We claim the control and the autonomy of our processes of or-ganization and alliances and we will further enhance our mutual accountability by valuing the wealth of our diversity and in the respect for our autonomies. We rec-ognize the essential role of the IPC in the facilitation of alliance building.

We Demand Food Sovereignity Now!

Continued from pg 2

NEFSALF Bulletin September 20104

This entails follow-up visits to trainees of the el-ementary training courses conducted by Mazingira

Institute under the NEFSALF Forum. The aim is to touch base with the farmers by assessing their progress in agricultural related enterprises as well as connecting the network members and allowing interactions and col-laboration amongst various stakeholders—farmers, ser-vice providers, government extension offi cers, research institutions, and market. The sample selection is done by divisional boundaries across the city of Nairobi and the peri-urban environs. We also try to reach out to as many NEFSALF farmers as possible at any one given visit.

The last post training visit was carried out in April this year, whereby we visited thirteen NEFSALF farm-ers across Nairobi and it environment. Amongst these were the new comers in urban agriculture belonging to Muungano Maendeleo, a human development organi-zation. Those members who underwent the elementary training have started farming enterprises despite limita-tions in the informal settlements and are already reaping the benefi ts of urban food production by putting food on the table and generating income from sales of extra pro-duce. Some members have initiated joint projects, such as the Mathare volunteers who rear sheep and goats joint-ly, thus improving their social interaction as well as their economic welfare. The group’s future plan is to purchase land in the peri-urban of Nairobi where they shall initiate various agricultural projects.

General observations:• 90% of farmers are practising farming as a business—

breeders, producers, value addition, trainers and tech-nology transfer;

• majority are practicing mixed farming;• better collaboration across sectors (community, gov-

ernment and market);• improved living standards (socially, health & nutri-

tion, economically);• adaptation of new agricultural activities and technolo-

gies. Example--greenhouse technology, fi sh farming.• NEFSALF members have taken up leadership roles

at community level due to the knowledge and skills acquired. For example representation at the Provincial and District Agricultural Boards in Nairobi; and

• improved networking among farmers through informa-tion sharing, production groups and exchange visits.

Post-training visits

3

4

6

92

1

5

7

8

10

Photos 1-9--Enterprises at Francis farm: indigenous chicken; rabbit farming; a training session; stawberries; pawpaws; dairy goat; multi-story garden; jatrova and sugarcane and sacks of organic manure. His is a demonstration farm on UPE activities at Makadara in Nairobi. Photo 10--Indigenous chicken at Charles Kamau’s farm at Kahawa West. He is also a rabbit breeder and a trainer in UPE.

Continued on pg 11

NEFSALF Bulletin September 2010 5

The presentation on urban gardening in Montréal was done by Mr. Belisle Sylvain of FECHIMM COCH, Montreal and a Board Member of Rooftops Canada. He was one of the study team members from Rooftops Canada. Montréal is a city in southern Quebec Province on the Saint Lawrence River and also the largest city in Quebec. He indicated that in Montréal, the aim of urban gardening is to break isolation and self production of organic and ethnic crops.

He belongs to a group of farmers who came together and reclaimed a dumpsite. He was once evicted from one dumpsite to give way to other types of land use. The group has board members, who meet from time to time and make rules on garden sharing-- tools, pest control and crops to be grown at certain times of the year.

Some years back, informal agriculture used to be practiced in Montréal but this has given way to conventional farming. Land grabbing by developers, contamination from toxic waste since gardens are on a dumpsite and com-petition between car parks and urban gardening are some of challenges that urban farmers face in Montréal.

Urban Gardening in Montreal

Mr. Sylvain addressing the Forum.Community gardening in Montréal.

The presentation on a study on cryptosporidia in live-stock was done by Prof. Erastus Kang’ethe from the University of Nairobi, Department of Public Health, Pharmacology and Toxicology. The objective of the study was to determine the prevalence of bovine crypto-sporidiosis and to create awareness of the disease among smallholder dairy households in Dagoretti Division, Nairobi, Kenya.

According to Prof. Kangethe, cryptosporidiosis is a di-arrhea infection caused by the parasite cryptosporidium. The parasite is transmitted after drinking or swallowing contaminated food or water. The study has evolved into a group now known as Dagoretti Crypto Society that has continued the work on sensitizing the community about the dangers of crypto and good animal husbandry practices. The Campaign members are known as Crypto Campaigners.

Kangethe mentioned that although 18% bovine cryp-tosporidiosis prevalence does not constitute a risk to human health, it warrants attention bearing in mind the closeness of humans to livestock in an urban setting, changing lifestyles, incidences of people living with

Crypto Campaign with small dairy farmers in Dagoretti: Crypto goes on TelevisionHIV/AIDS, overcrowding in areas with poor sanitation and children playing in open spaces that are contami-nated with cryptosporidiosis. The existence of shallow, unprotected wells in Dagoretti that are used as sources of water for human and livestock consumption poses a health risk due to contamination.

Crypto infection is contagious and precautions to avoid spreading the parasite to other people include protective clothing, boiling water, washing hands with soap and water after handling animals, visiting the toilet or col-lecting manure. William Kimani, a Crypto campaigner in Dagoretti explained to the meeting how the group un-dertakes door to door campaign sensitizing people on the problems related to the disease.

Professor Kangethe presented NEFSALF Forum with three copies of the dramatized “Health risks analysis of cryptosporidiosis in urban smallholder dairy produc-tion, Dagoretti, Nairobi, Kenya” by Makutano Junction, a show aired by one of the local television stations in Kenya. Copies of the DVD are available at Mazingira. Institute.

The second session kicked off during lunch break with peoplegoing round the exhibition tables by selected NEFSALF farmer. Some of the products exhibited in-cluded: solid waste recycling by making fuel briquettes and buskets; goat’s milk, peanut, green house, fi sh pond, mushroom, fi reless cooker, energy saving jikos among others. Five presentations were later made by members--touching on progress, challenges and future expecta-tions of the forum.

Ken, a youth and chairman of Vijana Youth gave a brief of the youth group that started with garbage collection and has started making fuel briquettes from the waste, cleaning household items/houses and offer fumigation services. After undertaking the elementary training course at Mazingira, he embarked on organizing youth in his neighbourhood who are now reaping the benefi ts a sustainable lifestyle. “We are able to feed ourselves and our families”, he reiterated.

Esther is the chairlady of Upendo Women group in Utawala and a trainer in communication, social skills

and group dynamics. Her group was a benefi ciary of a grant amounting to Kshs.100, 000 from Njaa Marufuku , a programme under National Agriculture Livestock Extension Programme (NALEP) in the Ministry of Agriculture in July this year. She is a small scale mixed farmer and rears dairy goats, rabbits, chicken and con-tainer gardening to grow an assortment of vegetables as well as rooftops gardens. She also processes pea-nut into butter, crunchy and powder. She owns a peanut grinding machine and offer the service at a cost (Shs. 30 for one kologramme). She informed the meeting how the women have added value to their lives by en-gaging in agri-enterprises. She acknowledged support from NEFSALF/Mazingira Institute and Ministries of Agriculture, Livestock Development and Fisheries.

Participants were informed of the emerging livestock such as wild birds and crocodiles. Esther has also been actively involved in organizing exchange visits between NEFSALF members and these have proved successful in knowledge and skills transfer. Recently she organized women to visit Mr. Charles Kamau, a rabbit breeder in

Kahawa West and Mrs. Margaret Ndimu a dairy goat cum arrowroot farmer in a peri-urban area. She has held value addition sessions with farmers in Ruai and Embakasi.

Sylvia, an urban farmer in Mwiki area of Kasarani in-formed the meeting about the benefi ts by being a mem-ber of NEFSALF. She is a dairy farmer with cows and goat, rears chicken and grows vegetables in containers on her backyard. She sells milk to her neighbors and processes yoghurt to what remains, thus adding value to it. She sits in the Provincial Agricultural Board as a farmers’ representative and has added agri-tourism to her activities, whereby visitors both local and interna-tional come to see her agri-business.

Ndungi, a peri urban farmer in Zambezi narrated life as a per urban farmer starting with goat farming, Asian vegetables, pigs and chicken farming. He is now grow-ing tomatoes in green houses. The excess runoff from the green house roof which used to erode his garden has been now been channeled into a fi sh pond. Early this

NEFSALF Farmers Network Meeting

William Kimani, a member of Crypto campaigners briefi ng the Forum on the activities of the group.

Prof. Erastus Kang’ethe during his presentation.

Continued on pg 6

NEFSALF Bulletin September 20106

Continued from pg 5

Continued on pg 7, col. 1

year, he managed to sell around 4,000 kilogram of to-matoes, 61 kilogram of fi sh, and 40 piglets. He is also a trainer and charges Kshs 200 per person for a visit to his farm. He belongs to a group of four men that help farm-ers construct good greenhouses at an affordable cost.

Julius Mirara is a breeder of the Saanen dairy goat, an urban farmer and a member of NEFSALF steering committee. He farms in Ruai area in the south east of

Nairobi. He narrated how the dairy goats have helped him generate income and climb the leadership ladder. He represents farmers in the Provincial Agricultural Board and is a member of the Kenya Breeders Stud. He encouraged NEFSALF farmers to engage in dairy goat farming based on: manageable space; feeds; nutrition and the good prices the milk fetches.

Farmers expressed the numerous achievements through

the forum and suggested the start of a NEFSALF open day-- whereby the farmers exhibit their innovations and products with the aim of networking and sharing.

Some of the challenges highlighted were: lack of mar-ket information for their produce, harassment by the Nairobi City Council and lack of guidelines on how to practice urban agriculture in the city.

IntroductionThe study visit was undertaken as part of an ongoing exchange program between Mazingira Institute and Rooftops Canada-Abri International on the theme of Urban Food Security-Urban Agriculture. The aim is to enhance urban agriculture practice and policy develop-ment through a learning exchange involving multiple stakeholders in Nairobi, Kenya; Cape Town, South Africa and Toronto, Canada.

Mazingira Institute and Rooftops Canada have been collaborating for 25 years in areas of Settlements Information Network Africa (SINA), Operation Firimbi (Blow the whistle) campaign against land grabbing and for land reform and Community organizing for human development. Recently the two partners saw the strate-gic need to move towards Urban and peri-urban agri-culture for food security and nutrition and small enter-prises.

The exchange program is on pilot basis from April 2010 to March 2011, and will address youth mobilization for productive employment, higher quality local food, the engagement of women, the benefi ts of improved nutri-tion through urban food production to HIV/Aids infect-ed and affected households. The exchange will also sen-sitize actors on ways of responding to the many health benefi ts as well as risks of urban food production, both through community level and local government level action.

The study visit was fi nanced by the Government of Canada through the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) in partnership with Rooftops Canada. Rooftops Canada-Abri International is the international development program of the Co-operative Housing Federation of Canada; the Canadian Housing and Renewal Association; the Ontario, New Brunswick and British Columbia non profi t Housing Associations and la Confederation quebecoise des co-operatives d’habitation.

About Toronto Toronto is the major city in the province of Ontario and was founded in 1793. It is also Canada’s largest city, the heart of the nation’s commercial, fi nancial, indus-trial, and cultural life. Although Toronto has the status of an international city, walking through feels like walk-ing through several “villages” in Africa with different communities that are deeply nationalist (Canadian) in outlook. Cultural and ethnic diversity is the identity of Toronto. Residential areas housing Greek Canadians, Korean Canadians, Chinese Canadians and ethnic groupings had street signs in both their local languages and in English.

Study team In June 2010, a team of three--Kuria Gathuru from Mazingira Institute, Nairobi, Kenya; Lourens De Jaeger from Communicare; and Stanley Visser, both from Cape Town, South Africa visited Toronto at the invita-tion of Rooftops Canada/ABRI International.

Stanley Visser is the Head, Development Facilitation in the Directorate of Economic and Human Development for the City of Cape Town. He is responsible for invest-ment facilitation, land reform and urban agriculture. As part of the urban agriculture portfolio, he oversees poli-cies and strategies, operational assistance to practitio-

ners, identifi es partnerships locally and internationally, facilitates the land reform process and ensures compli-ance. He hoped to see urban agriculture activities, un-derstand how urban farmers are organized, how they market and different forms of tenure.

Lourens De Jaeger is the coordinator, Learning Center for Communicare, the largest social housing organiza-tion in South Africa. The center offer many programs for impoverished communities, one of which is the food gardens program which aims at getting people one healthy plate of food everyday. The program includes supplying plants, training and technical services in part-nership with the city of Cape Town.

Kuria Gathuru works with Mazingira Institute, Nairobi, Kenya, where he coordinates the urban agriculture pro-gramme. He is responsible for the Nairobi and Environs Food Security, Agriculture and Livestock Forum (NEFSALF), a consortium of farmers, policymakers, veterinarians, researchers, as well as national and inter-national agriculture research institutions. He has over 25 years experience in urban agriculture and appropriate technology programs. His key strengths are in commu-nity mobilization, education and leadership training. He is also an urban and rural farmer, rearing dairy animals and growing fruits and vegetables.

The team visited many organizations and programs on urban agriculture in the City of Toronto mainly to understand the aspects of growing crops, technology, land management, health and community mobilization within the context of housing, urban development and food security. The three themes of the study visit were youth engagement, community mobilization and food enabling policy for urban agriculture. A wrap–up work-shop was held at the end of the study tour to consolidate observations as well as to share lessons from the visit, support future directions for such exchanges and to sug-gest potential partnerships and collaborations.

Toronto Public Health (TPH) Toronto is a global leader in municipal food policy de-velopment. The Toronto Food Charter outlines food rights and a vision for food security in the city, revealing how urban leadership on food can help the city achieve its environmental, economic, social and community pri-orities, while improving health. A visit to the TPH offi c-es on 277 Victoria Street showed a different government offi ce from what we are used to here in Africa.

The meeting was hosted by Barbara Emmanuel, the Senior Policy and Strategic Issues Advisor of Toronto Public Health. In 1999, Toronto City Council made a

commitment to ensure that every ward in the city had at least one community garden by 2003. She took us through the Toronto Food Strategy and how it has impacted on other sectors in the food web.The Goal of Toronto Food Strategy is vision and action toward health-focused food system and Identify ways the city can help build a healthier and more sustainable food system.

The newest Toronto Food Strategy report - Cultivating Food Connections: Towards a Healthy and Sustainable Food System for Toronto - was submitted to the Toronto Board of Health on June 1, 2010. This report defi nes food from fi eld to table, as generating health along the food chain, as connected to other pressing social issues. The report outlines a broad, creative and meaningful consultation and engagement process that will capture Torontonians Good Food Ideas, and more importantly, strategies to effectively implement these ideas.

The process involved consultations with several stake-holders among them farmers, city staff, city councillors, residents, community organizations and industries. The engagement was a two way conversation that led to people to start investing in ideas and processes of food strategy and about issues of community local food chal-lenges and how they linked to the strategic issues of the food strategy. The consultations centred on affordability of healthy food, lack of access to quality food stores, needs of newcomers, concern about lack of basic food skills among children, interest in community-based food solution and need for clearer information on city food policies-- governments to play a role in facilitating solutions.

Toronto carries out food safety inspections, supports community gardens, provides allotment garden spac-es, promotes healthy eating, provides meals for 7,000 people a day in childcare centres, shelters and seniors’ homes, supports the growth of food processors and re-tailers, coordinates food festivals and much more.

Toronto Environment OfficeWorking collaboratively with other City divisions and the community, the Toronto Environment Offi ce is working to increase lands for urban food production and develop a comprehensive strategy to address emerging issues related to urban agriculture. Food strategy is an important component of the Climate Change, Clean Air and Sustainable Energy Action Plan, which was unani-mously adopted by City Council in July, 2007. The Plan contains recommendations to promote local food pro-duction.

Africa - Toronto Exchange Visit

Toronto Public Health approval for food premises: Green-pass; Yellow-conditional pass; Red-closed. A typical waste collection bin on a street.

NEFSALF Bulletin September 2010 7

Continued from pg 6

Continued on pg 11

Toronto Food Policy CouncilThe TFPC operates as a sub-committee of the Toronto Board of Health. The members include City Councilors, and volunteer representatives from consumer, business, farm, labour, multicultural, anti-hunger advocacy, faith, and community development groups. In 1991, in the ab-sence of federal and provincial leadership on food secu-rity, the City created the Toronto Food Policy Council (TFPC). As one of the few urban-rural policy develop-ment bodies in Canada, TFPC tries to bridge the gap between producers and consumers. It has no authority to pass or enforce laws. It’s the power of ideas, inspired individuals and empowered communities that gives us infl uence.

During the discussions with the TFPC team, the Coordinator, Wyn Roberts indicated the fact that Toronto has recognized the importance of food in ad-dressing climate change. In July 2007, City Council of Toronto unanimously adopted a call to action on climate change, clean air and sustainable energy that included a plan to promote local food. He also mentioned that Toronto depends on an industrialized food system and that hunger is caused by poverty, not food shortages.

At the City level, Toronto is one of the fi rst municipali-ties in North America to take a leadership role in food policy. In 2001, Toronto City Council, led by the work of the TFPC and the Food and Hunger Action Committee, adopted the Toronto Food Charter, which is its offi cial vision of a food secure city and a useful starting point for a discussion of a food strategy. It highlights food as a critical connector among the city’s priorities.

Toronto Youth Food Policy Council

The Toronto Youth Food Policy Council (TYFPC) com-prises of food passionate youth who provide a youth perspective to the emerging Toronto Food Strategy. The Council is the voice for youth on food system issues and a platform to share ideas with the Toronto Food Policy Council. The youth members have various areas of ex-pertise including environmental studies, economics, nu-trition, and urban planning. The youth members have been active in developing close relationships with other food-oriented organizations to promote their perspec-tive on food policy in Toronto.

Discussions with Solomon Boye, at the Rockcliffe gar-dens indicated that the youth had benefi ted from the in-ternship at the farm where they grew vegetables for a daily allowance. The youth expressed mental alertness, ability to relate with nature and information sharing amongst participants during the internship period.

Toronto Community Housing (TCH)Toronto Community Housing is the largest social hous-ing provider in Canada, providing housing to over 164,000 families, seniors, singles and special needs ten-ants. They are committed to healthy communities, equi-ty and a strong learning culture. The study team visited the offi ces of TCH and was informed that the average household income in Toronto in 2001 was CD 69,125.(1 Canadian dollar=Ksh.71). We visited other coopera-tives such as Bain co-operative, community gardens as well as composting sites, Lawrence Heights, Westhill co-operative and Windmill Line co-operative—all members of members of TCH.

A visit to the Youth engagement project at Rockcliffe gardens man-aged by Toronto Parks and Recreation.

Hands-on composting practice with Vermi-composting Guru, Mike Nevin (right) and Kuria Gathuru (left) at Bain Cooperative.

Bain Cooperative: Community Gardens and Composting SitesBain’s gardens and composting system have won many awards and set an example of what is possible for other housing co-operatives. The history of the Bain commu-nity and its garden was one of many struggles, claim-ing the right to garden, fi guring out how to work to-gether and learning decision making through meetings. Before 1976 the courtyards were mostly empty spaces with scraggly hedges and token petunia beds. We visit-ed the permaculture gardens of Zora and Mike—which grow indigenous plants, and vegetables. Bain’s 500 residents have also been composting their own kitchen and garden waste using three-bin com-posters for almost 18 years. Fresh food scraps go in bins and are covered with leaves to prevent odors. The whole process takes about three months and the fi nal product is dark and rich compost.

Windmill Line Cooperative: Rooftop GardenWindmill co-operative’s unique building and garden design are intended to foster a co-operative spirit and the rooftop space encourages community interaction and involvement.The rooftop gardens enclosed in a 5ft by 4ft box are individually owned by the residents. Each individual plants what they want whether fl owers, herbs or veg-etables. Water has been provided by the Windmill coop and they have a rooftop workshop which has all tools and materials for construction of a box garden. A visit to a Rooftop gardens at Windmill Line Cooperative.

Westhill Cooperative at Lawrence EastAbout 6 women members of Westhill Coop have 17 raised beds on a former grass patch. The building has seniors, disabled and singles who applied for a grant from the City council. They have now spent 2,000 Canadians dollars on the project. Their main chal-lenge is how to organize the people in the building to grow their own food. The project is associated with the Westhill Food Bank that serves over 900 families a month. Women plan to set up a green house to grow fruit trees like raspberry with support from a Councilor in the City of Toronto.

A group photo at the box gardens by Westhill community cooperative (L) View of Westhill community building.

The Scadding Court Community Centre The Scadding Court Community Centre has an urban agriculture programme that started 13 years ago. The centre has fi ve sites with more than 200 farmers. Their theme is “plant a row grow a row.” They have 12 other plots in a local church compound and 1500 square feet in South Park for a hot meal program where a farm-er deposits $20 to rent a plot and gets back $15 at the end of the harvesting season.

To prevent underutilization of these plots, they place a red fl ag in your garden if you are not utilizing it properly and then a red one for repossession. They collaborate with the Green Bin programme of the City of Toronto to stock the pool with fi sh while not in for their children to practice fi shing

Community gardens outside Scadding community centre.

A member of Scadding community (centre) with visitors during a visit to the garden.

Community oven at Scadding community

centre

NEFSALF Bulletin September 20108

Lawrence Heights Community CenterToronto Community Housing developed engagement models for Lawrence Heights and Regent Park and in 2004, tenants in Lawrence Heights set up four commu-nity gardens. The idea for the gardens came out of an effort to renew the community and help residents feel more in control by putting neighborly life and owner-ship back into the community. More than 60 people came to the fi rst planning meeting and chose four im-portant places to plant the gardens.

Lawrence Heights has used the gardens to help resi-dents get involved in the community. The theme for the community gardens is “come grow with your neighbors and make new friends”. The gardens have helped break down barriers by giving people the op-portunity to connect in a new way.

The team held discussions with Helen Kennedy, the Community Recreation Coordinator; Tinashe, Food Justice Coordinator for North America and community animators. Food justice was described as the structural limb for combining everybody’s interests. The centre has a studio; Desk Top Publishing, Video editing and on-line radio/Skype.

The community centre started a community garden three years ago with youth having a negative attitude

towards gardening. When Mr. Tinashe Kanengoni, the Food Justice Coordinator for North America started mo-bilizing them around food, they changed their attitude and joined in. The visitors were informed that issues of group management are more critical than crop manage-ment at the centre. A case was illustrated by one of the animators about the inter-generational confl icts at the Lawrence Heights market.Tinashe, described the com-munity gardens as confl ict zones where different com-munity practice what they know.

Gardening at Lawrence Heights. On the right is Weslley, a com-munity member.

The visiting team outside Lawrence Heights Community Centre.Tinashe (centre) the Food Justice Coordinator gives his views at a meeting.

Farmers’ MarketsToronto has 12 farmers’ markets; including a year round market on Saturdays in various parts of the city. The study team visited Wychwood Barns Arts Farmers Market, and Lawrence Heights farmers market. At the Wychwood Barns market, farmers sell farm produce such as vegetables, fruits, cheese and baked foods. The market supports Ontario agriculture by encourag-ing farmers to grow as sustainably as possible. There is a community oven supported by the Stop where dif-ferent groups gather to prepare bread, pizza and other baked goods. Around 1,000 customers attend the farm-ers’ market held every Saturday at the Green Barns. During the visit, a farmer indicated that he drives for over 100km to sell his produce at the market. (Top) Lawrence Heights market (above) Wychwood Arts Barns Farmers Market. (R) Kuria admires strawberries, bananas,tomatoes etc.

The Stop Community Food CentreThe Stop as the centre is commonly known uses food as a tool to help build community and health, challenge poverty and fi ght hunger, from planting and growing, to cooking, sharing and advocating. The centre reclaims food as a public good. According to the Director, Nick Saul, the Drop-in served around 45,700 breakfasts, lunches and snacks and distributed 221,193 healthy meals through their food banks in 2009

The Stop opened the Green Barn, in 2009, as sus-tainable food production and education centre with a 3,000-square-foot greenhouse, commercial kitchen, classroom, sheltered garden and composting facility. During the visit we were taken round by Ms.Rhonda Teitel-Payne,the Urban Agriculture Manager. The green house is managed by Dr.Lord Abbey, who is currently setting up a pilot project on mushroom production. The green house has all sorts of crops such as arrowroots, sweet potatoes, cassava, kale and spinach. Here at the Barn people learn to grow, eat, celebrate and advocate for healthy, local food. The green house distributes over 14,000 seedlings to community gardens within the Toronto city.The Stop has compost units and vermin-composting bins that are used to teach children and the public about bio-diversity. (www.thestop.org)

(L-R): Priya, Nick, Kuria, Stanley and Lourens at the Stop. Container gardening at Greenhouse managed by The Stop.

Lord Abbey, green house coordinator with mushroom substrate. Compost bins outside the Green house.

The visiting team admire aquaponics technology at the Food Share offi ces.

FoodShareFood Share Toronto, a non-profi t organization, was founded 25 years ago to address hunger in Canada. Located at 90 Croatia Street, FoodShare works to empower individuals, families, and communities through food-based initiatives while at the same time advocating for the broader public policies needed to ensure that everyone has adequate access to sustainably produced, good healthy food.The study team had an opportunity of attending their Annual General Meeting held on Saturday 19th June 2010 at their offi ces. They approach hunger and food issues from a multifaceted, innovative, and long-term outlook by using models like

Continued on pg 9

NEFSALF Bulletin September 2010 9

co-operative buying systems, collective kitchens and community gardens. Their programs reach over 145,000 children and adults per month in Toronto. The programs include: Student Nutrition, Field to Table Schools, The Good Life Café, Focus on Food Youth Internships, The Good Food Box, Good Food Markets, Fresh Produce for Schools and Community Groups, Baby and Toddler Nutrition, Community Kitchens, Field to Table Catering, Power Soups, Community Gardening, Composting, Bee Keeping and Urban Agriculture.

FoodShare promotes policies, such as adequate social assistance rates, sustainable agriculture, universal fund-ing of community-based programs and nutrition educa-tion.They hope to make food a priority at all levels of society through subsidized fresh produce distribution, student nutrition programs, community gardening and cooking, classroom curriculum support, home made baby food workshops and youth internships. During the discussion at FoodShare, it emerged that Toronto’s waste system has a waste reduction but not nutrient re-capture strategy. It also emerged that local communities

would like to grow their own food and one can easily get access to land for urban agriculture. However no livestock is allowed in the city.

Public education on food security issues is a major fo-cus of FoodShare, creating and distributing resources, organizing training workshops and facilitating networks

and coalitions.Their innovative grassroots projects aim to promote healthy eating, teach food preparation and cultivation, develop community capacity and create non-market-based forms of food distribution. (www.foodshare.net)

Afri-Can Food Basket – Ujamaa FarmThe Afri-Can Food Basket (AFB) was founded to address food security in the African Canadian community in Toronto and now works with several additional communi-ties in the city including Polish, Russian, Persian, South Asian, Chinese, and Latin American. These communities are often missed by traditional food security organiza-tions and are the most vulnerably food insecure communities in the area. By working directly with affected communities, the AFB is drawing on the tremendous knowl-edge and energy of the city’s diverse cultures, to improve food security and strengthen neighborhoods. The team visited the McVean farm located at McVean in Brampton,where AFB has been allocated 2 acres in a conservation area/corridor for wildlife owned by Toronto Parks. We met the gardening Guru, Anan Lololi who introduced us to the other gardeners in the group. They started in February this year with six groups and have a youth farm and new Farmers pro-gramme. They emphasize on community building and reconnection with culture. Mr. Lololi indicated that people of African descent have issues with agriculture due to slavery in the past.

This past summer, as part of the Community Food Animators Project, the AFB animated gardens in three

communities. Once a group of interested individuals had been identifi ed, the AFB helped them fi nd the resources they needed, including community garden training programs, technical advice, and help with garden administration. These gardens play a critical role in food security, especially in low income, new immigrant com-munities. Above all, AFB strives to empower people to foster a community of gar-deners that are able to take charge and produce beautiful vegetables for themselves, their family and their communities.

Lourens (centre) from Cape Town with youth at Ujamaa farm.Group photo of Afri-Can youth and the study team.

Foodcycles Greenhouse in Downsview Park

Foodcycles is a not for profi t city farm in Toronto that inspires people to raise worms, make nutritious, vi-brant compost and grow food. Started by a group of community gardeners whose membership is through buying shares, their vision is to create a just and eco-logical urban food system that encourages all people to come together to grow, learn about, and celebrate food. They are located near a 20 acre park and close to a waste water lake. The community organization works to nurture urban agriculture in Toronto by producing and providing access to quality compost and good food. Their fi rst project is a greenhouse at Downsview Park where they grow on a one-acre market garden plot, as well as run a worm bank. This year, they will produce a fair amount of quality organic vegetables and compost materials.

The team visited the green house at Downsview park and were informed that Foodcycles is a project of several ac-tors that would like to replicate Will Allen’s Growing Power Project in Milwaukee,USA. They are focused on capital investment with 450 registered farmers and 350 volunteers. Among the plants in the green house

were,quina plant,tomatoes,lettuce spinach, buckwheat among others. For insect repellants they use sticky traps. FoodCycles is currently trying to expand their work in Toronto to create more FoodCycles setups in areas at risk.

Study team inside a green house at Downsview Park. Organically grown peas at Downsview Park.

Evergreen Learning GroundThe team visited a schools’ programme that is located in a priority neighbourhood. According to Sarah McCans, the Programme Coordinator, Evergreen focuses on energy and waste reduction, habitat and food gardens. They operate a lunch cafeteria where they charge 3 CAD per child for lunch. A typical meal is made up of pasta, salad and a drink. They have about 500 schools in the programme that are under the Toronto Schools’ Board. The main challenge is limited staff on the ground that has basic horticultural skills. They also run teachers’ workshops and organizes “green thumbs” small groups organized around 4 persons.

Since 1991 Evergreen has been engaging Canadians in creating and sustaining dynamic outdoor spaces—in schools, communities and homes. By deepening the connection between people and nature, and empower-ing the citizens to take a hands-on approach to their urban environment. Evergreen aims to improve the health and well-being of the cities in a sustainable way.

The organization offers a range of services, resources and funding to people interested in greening across the country. They have three main areas of programming: for school grounds; for community and public spaces, and for private grounds at home. Learning grounds is

The Principal of Sir Sandford Flemming Academy explains a point to Kuria Gathuru of NEFSALF at the school garden.

Continued from pg 8

Continued on pg 10

(L & R) Outdoor meeting at the food share offi ces on Croatia Street.

NEFSALF Bulletin September 201010

an exciting program for students, parents and teachers who are interested in bringing nature to their school’s grounds. Through this initiative, Evergreen encour-ages schools and their communities to participate in a nation-wide effort to reclaim Canada’s school grounds and to create healthy learning environment. The Learning Grounds program also teaches children about the importance of restoring and preserving the environment.

A visit to the Sir Sandford Fleming Academy, a high school in a high priority neighbourhood indicated that urban gardening is used as a tool in guidance and counselling. According to the principal, they started an urban agriculture garden with Toronto Schools Board and Eco- Schools to create safe spaces and for teach-ing purposes. They work with guidance and counsel-ing staff while generating income from the garden containing cherries, strawberry, kale, and amaranth. (L&R) Habitat garden in one of the schools supported by Evergreen.

Meeting with School Without Boarders team at East Scarborough. Gardens at East Scarborough with school children (top left).

Centre for Studies in Food Security – Ryerson University (CSFS)The CSFS was established at Ryerson University in 1994 and has been working to promote food security through research, dissemination, education, community action and professional practice. They take an interdisciplinary and systemic approach to social justice, environmental sustainability, health and socio-cultural aspects of food security. The centre looks at the interaction of public health and community gardens and the potential livelihoods in urban agriculture. The centre conducts community level training to mothers on basic nutrition and rights to food, cooking skills in schools and legislation

The main aim of the Centre is to create a platform for dialogue to increase food security through focusing on issues of health, income and the evolution of food system, including attention to ecological sustainability and socio-cultural diversity. Several members of the Centre have been involved with initiatives related to understand-ing urban agriculture activities and promoting their potential contribution to food and nutrition security of urban dwellers. In 2005, the centre through Prof. Fiona Yuendel worked with Urban Harvest in Nakuru on a study on “combating HIV/AIDS in urban communities through food and nutrition security: the role of women-led micro-livestock enterprises and horticultural production”.

Discussion with researchers at CSFS, Ryerson University.

An observation made was that, although there is a food policy at the city of Toronto, there is no similar policy at both federal and provincial levels. The centre has also built the capacity in food security in Brazil and Angola on community based education and training models.

Rooftops Gardens and Onsite Bee Keeping OperationsThis is a unique project on the 14th storey of the Fairmont Royal York Hotel in downtown Toronto. The rooftop garden has seventeen four-poster beds complete with seasonal herbs, fruit and vegetables, and an apiary of six bee hives. The team was taken round by Chief Chef, David Garcelon and also met the consultant gardener Marjorie Mason. Other produce includes organic basil, parsley, sage, tarra-gon, chocolate mint, peppermint, spearmint, chives, and lemon balm, two pear trees, fi ve cherry trees and a single green apple tree, marjo-ram hot peppers and cayenne pepper plants. It is also home to over 300,000 bees in peak season. The Toronto Beekeepers Cooperative, a group of 25 volunteers and one certifi ed keeper, care for the hives.

The Fairmont Royal York’s partners are Toronto Beekeepers Cooperative, City of Toronto (clean & beautiful) and second harvest. This is a unique venture that could be adopted by high rise buildings in the city of Nairobi and managed by the youth. (Top) Bee hives and (L-R): Lourens and Stanley Visser from Cape Town, Chief Chef Guy Garcelon and Kuria Gathuru of

Mazingira Institute at the roof top garden of Fairmont hotel.

Continued from pg 9

Schools Without BordersSchools Without Borders (SWB) is a unique youth-led organization that makes education and learning more accessible to young people. SWB plays an integral in-termediary and supportive role in grassroots commu-nity development in Canada and around the world by supporting young people to create their own platforms for change and build the form of communities they want to live in. They have linkages with several organi-zations who offer services freely at the centre. For ex-ample, they recently developed linkages with a law fi rm that gives legal aid to needy clients at the centre. They manage a three million Canadian Dollar programme at East Scarborough Storefront (formaly a police station) where they do not pay rent. The Scarborough centre sees over 5,000 persons every month and has over 300 volunteers who come in at different times.

NEFSALF Bulletin September 2010 11

...Post training visits continued

Lessons During the visit there were such terms as global warm-ing, community/youth engagement, food strategy, roof-top gardening, community animators, organic and food justice that kept coming up in the discussions and site visits. Concerns were made over expanding cities that are swallowing farmland, how to advance food policy agenda and practice, how to use food to make a com-munity happen, how to broaden action around youth and

children engagement, how to identify successful models and champions of UA and how to integrate all this into the policy conversation..

Other Issues that came up during the discussions were engaging young women in agriculture, food and HIV/AIDS. Food was described as an item that connects people, a powerful vehicle to address barriers and build cities. Apart from the exchange visits between cities, an

annual seed exchange was one of the suggestion to cre-ate space for trust among the urban and peri-urban farm-ers and other interest groups.

AppreciationNEFSALF would like to appreciate Rooftops Canada/ABRI International for supporting the study visit and all those individuals and institutions that hosted the study team while in Toronto, Canada.

Photos 11 & 12: Kageci,(2nd left) with daughter, grand daughter, Kuria and Alfred, Mazingira Institute at her family’s rabbit farming project. Photos 13-17: New comers in urban farming, also members of Muungano Maendeleo, with their sheep, goats and vegetables at Kariobangi and Korokocho areas in Nairobi. They have a dream of acquiring land in peri-urban Nairobi,.

11

14

17

20

23

12

15

18

21

24 25

13

16

19

22

26 27

Photos 18-22: Margaret Ndimu, a farmer in peri-urban Limuru. Has dairy goats, rabbits, kenbrew chicken and grows indegenous vegetables, arrowroots and processes banana jam from bananas on her farm. Photos 23-27: Ndungi Ngugi: grows tomatoes in green houses; fi sh farming and pigs as well as grows vegetables. He constructs and conducts training on green house management.

from pg 4

Continued from pg 7 col.1

NEFSALF Bulletin September 201012

Printed by Colour Print

Editorial TeamDavinder LambaDeborah Gathu Kuria Gathuru

DesignMacharia Henry

In order to help students develop their skills and capac-ity to address global problems, speci cally those relat-ed to the current global food crisis and climate change, an urban agriculture course series has been developed as part of the elective offerings of The Chang School’s Certi cate in Food Security. The series will consist of four courses and students who complete them will re-ceive of cial documentary acknowledgement from the university of having achieved completion.

The four courses are:• Understanding Urban Agriculture (CVFN410)• Dimensions of Urban Agriculture (CVFN411)• Urban Agriculture Types (CVFN412)• Urban Agriculture Policy Making (CVFN13)

These four courses will provide students with a com-prehensive picture of current practices in urban agri-culture and the environmental, socio-economic and political challenges that must be addressed to support them. Therefore, students who complete the course se-ries will not only have gained in-depth knowledge of the technical aspects of urban agriculture but also of the policy dimensions and governance issues that must be taken into account for development of effective urban agriculture systems. The thematic focus of the course series is to demonstrate the importance and value of urban agriculture as an integral part of planning and development for sustainable, food-secure and healthy urban environments.

The urban agriculture courses are also electives for the food security certi cate and can be used by students as part of their course requirement for completing the certi cate if they so wish. The courses have been devel-oped in a unique international partnership between The Chang School and the International Network of Re-

sources Centres on Urban Agriculture and Food Securi-ty (RUAF) in the Netherlands, which is a global leader in urban agriculture research and development. The in-structors for the courses are based in Canada, Lebanon, the Netherlands and Sierra Leone and so bring a wide range of local and international knowledge and experi-ence to the courses.

Who should enroll in these courses?Recent reports by United Nations agencies have high-lighted the practice of urban agriculture and its signi -cance, constraints, and potential. Furthermore, many cities have issued new regulatory provisions and scal measures, and are creating municipal programs to sup-port urban agriculture. The demand for professionals with urban agriculture training has never been greater.

The Chang School’s new urban agriculture courses will appeal to a diverse group of individuals and organiza-tions across the globe:• students interested in urban agriculture and its policies• researchers and professionals working in social ser-

vices, public health, environmental studies, interna-tional development, food aid, poverty alleviation, and other elds

• non-governmental organization (NGO) and govern-ment staff in related elds

Our InstructorsThe Chang School’s instructors bring a wealth of expe-rience and up-to-date knowledge to every course. Our food security instructors are internationally recognized. Having lived and worked around the globe, they under-stand the challenges of implementing urban food secu-rity projects and policies; bring together backgrounds in

Urban Agriculture CoursesUrban agriculture is increasingly recognized for its potential contribution to urban poverty alleviation, urban food security, productive reuse of urban wastes, urban greening, local economic development, and community devel-opment, among others. In response to an increasing demand for training in urban agriculture, Ryerson Universi-ty’s G. Raymond Chang School of Continuing Education and Centre for Studies in Food Security (www.ryerson.ca/foodsecurity) are developing a portfolio of distance education courses on urban agriculture in partnership with ETC-Urban Agriculture (www.etc-urbanagriculture.org) and the international network of Resource centres on Urban Agriculture and Food security (RUAF) (www.ruaf.org).

urban planning, architecture, agronomy, and ecology; and have coordinated several regional training activi-ties in urban agriculture spanning several continents.

Our ExpertiseRyerson University’s Chang School is Canada’s lead-ing provider of university-based continuing education for adults. We are leaders in exible learning options, offering more than 1,100 professionally relevant cours-es to individuals and organizations.Our partners, ETC-Urban Agriculture and RUAF, have worked over the past 10 years to assist local and inter-national actors in the participatory design, implemen-tation, and evaluation of effective policies and action programs on urban agriculture.

Urban Agriculture Course DesignIn a unique online learning environment, students will participate in group discussions and complete assign-ments and exams. You will be supported by instructors and a technical help desk, and will have access to an online library and resource centre. These distance edu-cation courses are designed in such a way that they can be accessed with low-speed Internet connections. To balance theoretical learning with practical applications, the course curriculum will include a variety of well-documented examples and case studies from different continents.Urban agriculture courses can be taken individually or as part of the current Certi cate in Food Security.

How to Enroll - Canadian StudentsFor individual course enrollment, visitwww.ryerson.ca/ce and click on Enrollment for details. New students can enroll in person (350 Victoria Street) or by mail. Returning students can enroll in person, by mail, or online. If the deadline for the mail in applica-tions has passed please fax your application to Distance Education at 416.979.5196. Enquiries about registra-tion can be emailed directly to [email protected]

How to Enroll - International StudentsFor international student enrollment details, please e-mail [email protected].

CoursesAll courses are 42 hours and delivered online. For com-plete course descriptions, course fees and scheduling details please visitwww.ryerson.ca/ce/foodsecurity

The Chang School launches course seriesin Urban Agriculture

Available online, the course series will focus on urban agriculture as an integral part of sustainable

food security

August 17, 2010, Toronto - Starting in Fall 2010, Ryerson University’s G. Raymond Chang School of Continuing Education will be offering a course series through online learning in urban agriculture as part the Certi cate in Food Security. Students who complete the course series will receive of cial documentary acknowledgement from the univer-sity. The four courses that make up the series are:

Understanding Urban Agriculture (CVFN410) offered in Fall 2010

Urban Agriculture Policy-Making (CVFN413) offered in Fall 2010

Urban Agriculture Types (CVFN412) offered in Winter 2011

Dimensions of Urban Agriculture (CVFN411) offered in Spring/Summer 2011