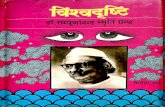

Vishva Drishti Part I Dr. Sampurnanda Smrti Grantha - Sampurnananda University_Part3

Rath 2012_Varieties of Grantha Script

-

Upload

deepro-chakraborty -

Category

Documents

-

view

88 -

download

12

description

Transcript of Rath 2012_Varieties of Grantha Script

Aspects of Manuscript Culture in South India

Edited by

Saraju Rath

BRILL

LEIDEN • BOSTON 2012

CHAPTER TEN

VARIETIES OF GRANTHA SCRIPT: THE DATE AND PLACE OF ORIGIN OF MANUSCRIPTS

Saraju Rath

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1 The development and, eventually, wide-spread use of grantha1

script in the southern part of the Indian subcontinent form a constitu-tive part of the extensive manuscript culture in the Indian world and in Asia, especially South and South-East Asia. The beginnings of grantha script around one and a half millennium ago are no more directly accessible but impressive fragments of its material basis and traces of its vibrant life history are still visible. Although the available material, in the form of inscriptions and even more in the form of manuscripts, is abundant, its detailed examination has hardly begun. Early works on Indian scripts such as the one by Burnell (1878) pro-vide the basics only on grantha next to several other scripts of South India. Recent publications specifically devoted to grantha2 do not intend to be more than introductions and study aids for beginners. In this article it is my aim to clarify, in the framework of a synthetic over-view, distinctive characteristics of varieties and stages of development of the grantha script that have so far not been noted or that have remained vague and ambiguous. For this I will not rely on tables of hand-drawn characters (as is mostly done in recent publications on grantha) but on characters that are directly taken from manuscripts from different periods.

1.2 Texts in the Sanskrit language, transmitted and often also pro-duced in South India, appear in different scripts such as telugu, kan-nac;l.a, grantha, nandinagari and malayalam. Among these scripts,

' Because I have to refer to a few scripts that have the same names as the lan-guage to which they primarily belong, script names in this article will start in small case and language names in capital : telugu script-Telugu language.

2 Grlinendahl2001, Visalakshy 2003.

188 SARAJU RATH

grantha occupies a major position as this is the only script specially designed to write Sanskrit (and Vedic) texts, including royal records and documents in the southern states of the Indian subcontinent. Here, grantha is the transregional script employed for texts in the Sanskrit language next to other scripts which are preferably used for other languages and vernaculars: tamil for Tamil, telugu for Telugu, etc. Some of these scripts, for instance telugu, are suitable for writing Sanskrit and have actually been employed for that purpose next to the writing of the corresponding regional language. Other scripts such as tamil, are incapable of distinctively representing all sounds ofSanskrie and are hence in need of grantha for the adequate representation of these sounds. Just as Sanskrit as language of several sciences, of litera-ture and of brahmanical and buddhist religious texts is normally part of a bilingual situation-speakers in south India thus typically com-bine lmowledge of Sanskrit with an intimate familiarity with Tamil, Telugu, etc.-like that the grantha script in south India is normally part of a biscriptual situation in which grantha combines with tamil, telugu scripts etc. 4 It should hence not be a matter of surprise that grantha shows regional differences parallel with the distinct nature of the other scripts with which it stands in a biscriptual relation. More-over, grantha has gone through a number of relatively clearly identifi-able stages of development, from the first half of the first millennium CE till early modern times. 5 Among the multifaceted changes in style and calligraphy of the characters of the different varieties of the script, which are the ones that may serve to determine the relative date of a grantha manuscript?

1.3 Since especially South Indian manuscripts normally lack any precise statement about the date of their production, indications that can be derived from subsequent changes in the style and calligraphy of the script-varieties are very much needed for a chronological determination of available manuscripts. Even in the very limited number of cases their colophon does contain a date, the system of dating usually gives the Samvatsara year which follows a 60-year cycle6

3 For example, tam iJ alphabet ka represents Sanskrit kha, ga and gha. 4 For the moment we will here not take into account the later use of devanagari

in South India, which wil l make the situation mu lti -scriptual. 5 Its origins are therefore contemporary with those of siddhamatrka and early

nagari in the middle and northern part of the Indian subcontinent (Rath 2006). 6 See for telugu manuscripts, Sarma's article on "From my Grandfather's chest of

palm leaf Books" in tl1e present volume.

VARIETIES OF GRANTHA SCRIPT 189

of Brhaspati (Jupiter), so that a year given as, for instance, virodhakrt samvatsara, may correspond to CE 1551 or to 1551 + 60 = 1611, or to 1671, to 1731 etc. or also to 1551-60 = 1491 etc. In recent decades laboratory techniques have been developed to determine the dates of an object on the basis of the ratio of a radioactive isotope (C, 4) in the material texture. In practice this technique leaves a considerable margin and often remains incapable of adding a significant chronological indication beyond the rough estimates that can be made on other grounds.

2. VARIETIES OF GRANTHA SCRIPT

2.1 In his discussion of the South-Indian alphabets and their devel-opment, A.C. Burnell (1878: 14) gives a chronological chart of the southern scripts in order to show the derivation of some of these scripts (including grantha) from southern brahmi, as well as their link with other scripts from southern origin. I give here this chronological chart with minor modifications.

500BC

250 BC

1st AD

350

650

1000

1300

1600

Southern Scripts, 250 B.C. - 1600 A.D.

BRAHMT

Gupta (N) cave

I cera Calukya Ver'lgi

/\ Proto - Grantha Vatteluttu W. Calukya E. Calukya Old Javanese (Kawl)

I I

o•! T,,,l_"•' G• II I I I I

Tulu Malayalam Grantha Tamil

I Ha!a-Kannac;la

I Old Telugu

I Kannac;la Telugu Modern Javanese

Chart 10.1. A Chronological Chart of Southern Scripts.

190 SARAJU RATH

A closer study of grantha from early stone-inscriptions, copper-plates and palm-leaf manuscripts shows that a few clearly distinct varieties developed in the course of time. Their style shows the reflection and influence oflocal scripts, as we notice below.

Chart 10.2. Varieties of grantha script found in manuscripts.

Table 10.1. Varieties and chronology ofGrantha script in inscriptions, mss, etc.

Varieties Period Dynasty Areas Main (century CE) materials

grantha with 4th-7th Ca lukya, Inscriptions, tel. &kan. Kadamba & copper-pl.

--- - -- -- Pallava ---- ----late grantha with 15th+ -- -- Vijayanagara, mss. tel. & kan. Bijapur, G untur

grantha with 6th+ Pallava, Cera, Madurai dt. Inscriptions, vatteluttu Cola, Pandya S, S-W TNadu, copper-pl. &

& S, S-E Kerala mss.

grantha with 7th + Cola, Pandya, Arcot, Pulicat Inscriptions, tamil PaJlava, copper -pl. &

mss.

grantha with fromllth , esp. Cola, Cera, South Kerala, Inscriptions, ma laya lam from 14th Pandya Travancore copper-pl. & (& arya-eluttu) mss.

grantha with from lOth, esp. Kasargad dt. Inscriptions tulu -mal. from 14th Malabar,NKeraJa, &mss. (& kol-eluttu) Tulu country

VARIETIES OF GRANTHA SCRIPT 191

2.2 As indicated in Chart 2 and Table 1, the varieties we find are,

i. grantha with telugu-kannac,i.a n. grantha with vatteluttu iii. grantha with tamil iv. grantha with malayalam (arya-eluttu) v. grantha with tulu-malayalam (kol-eluttu)

i. Stone inscriptions and copper-plates which are found from the 4th-5th century onwards show an archaic form of grantha characters (representing Sanskrit) that has a close affinity to archaic telugu-kan-nac,i.a7 characters (representing early Telugu and Kannac,i.a) of the same period. Especially the grantha characters which, in spite of their mon-umental context, have a cursive form show this affinity. This suggests a development of early grantha in connection with early telugu-kannac,i.a writing and in parallel monumental and cursive styles (the latter probably on perishable materials now lost). The grantha charac-ters were developed in a full-fledged way to a common variety in course of time through a number of developmental phases. The par-ticular early specimens of this writing found in inscriptions and plates belonged to the period of the Pallava, the Chalukya and the Kadamba rulers, who reigned till the mid 7th century. From then onwards we see a gradual speciation till the early southern scripts acquire an indi-vidual status and an independent identity.

In addition to the early sources available in Indian epigraphy, inscriptions and plates outside India show the archaic cursive and monumental styles of early grantha that is close to telugu/kannac,i.a. K. A. Nilakanta Sastri (1949 [2003]: 79-82) refers to both the monu-mental and the cursive style of this early grantha in some early inscrip-tions discovered in Java, e.g. one at Ci-Aruton. Also Diringer refers to

7 Inscription found in Halmidi, dated ca . 450 CE and Badami rock Inscription (5th-6th AD) which was found in Bijapur, Karnataka. Also see Sivaramamurti 1952, p. 222.

Also see Epigraphia Indica I, VIII, pp. 159-163, Pikira plates of Pallava king Simhavarman, dated 5th AD, found in Nelatur, Ongole taluk, Guntur District, Andhra Pradesh.

192 SARAJU RATH

this inscription.8 Another relevant specimen is formed by the two thin gold plates known as Maunggun plates discovered in Burma.9

In available manuscripts the archaic monumental and archaic cur-sive styles of grantha have so far not been found. However, we do find Sanskrit manuscripts of a later period written in a round variety of grantha where telugu or kanna<;la characters are inserted in between; for example, the word grhapati where gr appears in telugu [or/and kanna<;la] and hapati in grantha.

ii. According to Burnell (1878: 49), tamil script is the direct descen-dant from vatteluttu. Both are closely similar, except that in vatteluttu the character slants from down-left to up-right. 10 The observations of C. Sivaramamurti (1966: 235) are basically in harmony with this: "Grantha and Vatteluttu were used in the extreme south of the Peninsula. Vatteluttu is a form of cursory Tamil written in a peculiar slanting way .. . " He further explains, more interestingly, how these two scripts nevertheless developed to a large extent independently and maintained their distinctive features: "as [vatteluttu) had an inde-pendent development, the letters differ to a certain extent in their gen-eral features with greater resemblance in such letters as a, au, e, ka, pa, ra, la and va, but [with less resemblance] in letters like ta and rna, and in some cases [the resemblance is even less) by their peculiarly differ-ent shape as for instance in i, ta, na and ya, though the ultimate common origin can easily be traced." Vatteluttu is thus to be regarded as an old and cursive form of southern script which was important from the 5th century onwards, 11 under Pallava, Cera, Pandya and Cola rulers. Grantha characters occurring with vatteluttu were mostly used in inscriptions and later in palm-leaf manuscripts in areas such as South Malabar, Coimbatore etc .. In his report on the palace records (grandhavaris) in Malabar and Kerala, Dr. Nampoothiry mentions

8 See 1996, David Diringer, The A lp habet: A key to the History of Mankind, Fig. 174, p. 383.

9 K. A. Nilakanta Sastri (194-9, reprinted in 2003: 14) writes, "The inscription comprises quotations from Pali Buddhist scriptures written in a clearly South Indian alphabet of the fifth or sixth cen tury Ao" Furthermore, he clarifies (on p. 15), "a line of inscription in Pyi1 and Pali, in an ea rly Telugu-Canarese script of South India, very closely allied to that of the Kadambas of Vanavasi and that of the Pallavas of

The character is practical ly the same as the sc ript of the Maunggun plates .. ..

' 0 It gives me an impress ion of running handwrit ing. " Mahadevan 2003: 2 11 -215.

VARIETIES OF GRANTHA SCRIPT 193

the existence of palmleaf manuscripts of the 16th century in vatteluttu and koleluttu script. 12 With regard to epigraphical evidence of the 8th century, Sivaramamurti (1966: 229) observed the following: "Grantha letters occurring with vatteluttu or by themselves, in pure Sanskrit texts ... [represent] a cursory forrn. [of grantha] which in many respects differs from [tamil scripts] though [it is] based on [those tamil] scripts." However, Mahadevan (2003: 212) 13 reports that "the Royal Chancellery of the State of Travancore in South Kerala continued to use Vatteluttu even in the 19th century .... " While going through manuscripts in vatteluttu I noted that the archaic variety and the later development of the combination grantha plus vatteluttu in palrnleaf manuscripts show very little proximity with tamil characters. An illus-tration of a palmleaf written in the grantha-vatteluttu variety is given in Figure 10.1.

Figure 10.1. A palmleaf ms. showing grantha-vat:teluttu variety. Courtesy:Vaidika Samshodhana Mandai, Pune, India.

Picture by the author. See colour section, Plate XI.

m. The development of characters in grantha-tamil is seen in Pallava, Cola and Pandya inscriptions. In his book on Indian epigraphy and South Indian scripts, Sivaramamurti (1966: 222-234) shows in detail the stages of development through illustrations of the mixed grantha-tamil variety in inscriptions. In the manuscript tradition, however, both the scripts got prominence with an independent, individual sta-tus. The following points deserve notice:

a. In a manuscript text in Sanskrit, the text is written in grantha which is sometimes mixed with a few letters (the ones most resem-bling their tamil counterparts) in tamil style, for example, i, e, o, ra, l and 1. This happens often if the scribe is from Tamil origin.

12 Dr. N.M. Nampoothiry in his "Report submitted to ICSSR, New Delhi" (1983): "Palm leaf manuscripts are collected in seventy bundles. The earl iest of them is dated 1538 AD. Most of them are written in old scripts. A few of them are in ko[le] luttu/ vatteluttu".

13 Mahadevan 2003: 212: "Gradually, however, the Malayalam script completely replaced the phonologicaLly deficient and palaeographically degenerate Vat:teluttu by the end of 18th century AD".

194 SARAJU RATH

b. In this case we also find the Sanskrit text purely in grantha script but with wrong readings-for instance, patapatma in place of pada-padma-which can be explained from the phonetic structure of the Tamil language and the tamil script. 14

c. In a Sanskrit text with Tamil commentary, the Sanskrit version is written purely in grantha and the commentary mainly in tamil script and Tamil language. Literature of the type shows this variety.

Figure 10.2. A palmleaf ms. in grantha-tamil script. Johan van Manen collection; courtesy: Kern Library, Lei den . Picture by the author. See colour section, Plate XII.

iv. Among scripts for Dravidian languages, malayalam script is closest to grantha as it shows numerous similarities in many individual characters. This was well noticed already by Burnell, who referred to malayalam script as a catagory of modern grantha 16 (western grantha); however, the appropriateness of the name which he used for this, tulu-malayalam, can be disputed. 17 The grantha-malayalam18 mss studied

14 Such reading may confuse non-Tamil Sansluit scholars but may be automati-cally corrected in reading and understanding by bilingual and biscriptual Tamil Sansluit scholars.

15 I take the term "gem and coral" here in its broader sense of a combination of a regional Dravidian language and Sanskrit, not in the sense of the schoolmaster approach of the Lilatilakam (on which cf. now Freeman 2003: 446-450) which tries to narrow down the term to apply only to a highly regulated "union" (yoga) between and Sanskrit. The term has even been employed with reference to a projected "commingling of Brajbhasa and Khari Boli" (Trivedi 2003: 1016).

' 6 See Burnell 1878: 41 -43. Burnell catagorises modern Grantha as eastern Grantha and Tulu-Malayalam as western Grantha.

1 7 Burnell gives the name "transitional grantha" to the script I would call tulu-malaya lam.

18 Seeing the combined style, I prefer to nam e it as grantha-malayalam and see no point of naming it as tulu-malayalam. In ea rlier days, kanna<;la script was domi-

VARIETIES OF GRANTHA SCRIPT 195

by me make me agree with Mahalingam's view on the influence of the old vatteluttu style ('round-hand' calligraphy) on malayalam characters which are otherwise close to (and apparently derived mainly from) Arya-eluttu. Regarding the place of Arya-eluttu in the evolution of Vatteluttu, Mahadevan (2003:212) writes,

"Ultimately, however, it became necessary for Malayalam to have a script of its own, which was formed from the Grantha script. The new script which came into existence towards the end of the 14th century AD was called Arya-eluttu to distinguish it from Tekkan Malayalam, the local name for Vatteluttu in South Kerala and Koleluttu, another variant of Vatteluttu in North Kerala. Even after the introduction of Arya-eluttu for Malayalam, Vatteluttu lingered on as it was popular among the sections of the population whose dialects were not so heav-ily Sanskritised as that of the Nambudiri Brahmans."

v. The tulu-malayalam script is a variety of grantha dating from the 8th or' 9th century CE. It is the variety which Burnell called transitional grantha. From about 1300 CE we see the script in the form which it has basically maintained till modern times. Currently two varieties of tulu-malayalam are in use: Brahmanic, or square, and Jain, or round. The development of malayalam script and its varieties (esp. Koleluttu) deserves further research on the basis of mss in mixed scripts.

Figure 10.3. A palm leaf ms. in grantha-malayaJam. Courtesy:Vaidika Samshodhana Mandal, Pune, India. Picture by the author. See colour section, Plate XIII.

3. GEOGRAPHICAL DIFFERENTIATION AND DEVELOPMENTS OVER TIME

3.1 The locations of inscriptions and of collections of manuscripts etc. point to distinct areas where the different varieties of grantha

nantly used in Tulu country; full -fledged malayalam variety came here in use later 011.

196 SARAJU RATH

were popular and dominant. A map which specifies the geographical areas where the respective varieties developed and flourished in early centuries is provided below.

• 4r•tlU,o C,r .. v .•

• • C,.r . Tu/u·4\f11htjlfhtrn

Figure 10.4. Map of South India showing the areas of the varieties of grantha. Map by author. See colour section, Plate XV.

3.2 Apart from geographical differentiation there are developments over time. We find notable changes in some aspects of grantha script applying to some or all varieties which can be used in the determina-tion of a date of the manuscript. In addition, each scribe has his own style but in the present study I abstract from such variations and focus on features that change over time. These notable changes can be sum-marized under the following headings:

[ A ] Specific characters (vowels and consonants) [ B ] Conjunct consonants & placements [ C ] Punctuation marks [ D ] Numerals: alphabetic, syllabic, or digital

3.3 With regard to [A], [B] and [C], the comparative chart (table 2) illustrates some major changes over time. The earliest stage is repre-

VARIETIES OF GRANTHA SCRIPT 197

sented by grantha characters not on palmleaf but on copper plates; they derive from the so-called Leiden Copper-plates which belong to the period of Rajaraja Cola I. Later stages are represented by charac-ters from palm-leaf manuscripts belonging to different periods (16th-19th).

Table 10.2. Changes over time in grantha.

Column! Column2 Column3

Chola cp. Palmleaf mss Palm leaf mss llth AD 16-l8th AD 19th AD

VOWEL/MATRA

A <:{'fJ ' eft! ' l Bc1 A tQj

U/U

AI G'\ e >same continued G"

VISARGA 0 0

AVAGRAHA .s CONSONANTS

KA <f1> dP Jre

RA IT a:r,rtr fV CONJUNCTS

KSA f8 VYA 02-}_, .. 'bi)

c;.- '

0-[_)

SRI G 'r!1-(}j

RNNA/RPPA/ I rr-!--;;tb-?196 RPA/RJJA

198 SARAJU RATH

3.4 In the comparative chart (table 2) only a small number of charac-ters and conjuncts are discussed in order to illustrate changes in style and calligraphy which have occurred from time to time. Among avail-able sources I give examples from manuscripts of the van Manen col-lection and from the so-called Leiden copper-plates which belong to the 11th cent. AD of Chola King Rajaraja Chola I.

Vowel A and A a. Column 1 (copper-plate) gives an ancient vowel A which is simple, having a single loop at the left side below, and has few ornamental features except for the connected vertical line. An early form of ms. variety in column 2 shows double loops, a feature that is not common in later periods. The A in a 19th cent. ms. (last column) is simpler in form . b. In long A, the ancient version in column one has an extending line at the right (of the character) which remains proportional when it comes out from the middle in a curving shape (a bit like roman numeral three) and encircles it from below till the lower front part of the character is reached; the ms. style shows considerable freedom regarding the extending line which sometimes starts from the top, sometimes from below, and which continues even till the top of the frontside of the character.

Matra U and 0 c. The miitras u and u after consonant in copper-plate are put in two vertical lines with the lower ends joined in the case of all characters such as su orrJ, bu du etc. In few cases, earlier mss show a partly similar style with the matras exclusively put below the characters in the middle part such as pu "'tr', and in other cases they are put at the side, for example, su Mss of the 19th century do not show uniformity: this matra sometimes starts from the corner below or at the side, in pu not from the middle. Even with the same character in the same ms. of this period the style of this matra can each time be different (starting from the corner below, at the side or from the middle); this was not the case in earlier centuries.

Diphthongs d. The matra ai (similarly au not shown here) in inscriptions and copper-plates in Chola grantha consists of two spiraling curls one above

VARIETIES OF GRANTHA SCRIPT 199

another preceding to the consonant character to which it belongs and this style is known as PF$thamatra, occasionally also one curl in front of the other and both preceding to the consonant; in manuscripts (16th-18th and 19th cent.) only the latter style is found.

Visarga e. The style of visarga shows some variation in manuscripts between the 16th and 18th century, the similarity between the various styles being that two dots are never placed separately. The second column shows a running style which differs both from what is found in earlier and from what is found in later centuries.

Consonants f. Among consonants I have taken the first one, ka, as test character, and ra as an additional one. A complete overview of all characters is to be provided in a forthcoming publication. To be noted is the subtle distinction between the ka in the early ms. variety and the later one: the right-hand loop is only curved but not joined. g. Two long vertical lines joined both on the top and the bottom represents ra in copper-plate and inscription writing. In later writing ra is more open and has an addtionalline. In tl1e early mss. the special features are: (i) the beginning line often joins the second one whereas the first line remains always separate in 19th century ms. and in some earlier transitional forms; (ii) the topline is lengthened which is mostly not the case in 19th cent. ones.

Conjuncts h. In case of conjuncts, both characters in full form are put either one above the other or side by side: this is what we find both in inscriptions and copper-plates and in early mss. However, later mss. show ligatures in which the first character is abbreviated and the second one full. Even in later mss. we may also find the old system. i. Inscriptions and copper-plates are consistent in the use of a brief conjunct form of ya slanting from left-down to right-up which is added to consonants; in early mss. a new style comes up which is more vertical and more rounded; this is the only form normally found in later mss.

Duplication in characters j. Characters can be doubled in all periods (from early Sanskrit

200 SARAJU RATH

inscriptions till recent manuscripts19), especially in conjuncts with

r and h (Piil).ini's rule 8.4.46 aco rahabhyarh dve) but also in other environments. 2° For instance, sri is found written as ssri (with s below sr). These doubled consonants, as in rppa, rcca, rjja, are in the earlier centuries written one above the other, later on mostly side by side (with the repha in between).

3.5 With regard to numerals [D], the use of specific symbols and sys-tems of representation in grantha script have not yet been sufficiently studied and needs a separate treatment. Scholars such as Ojha, Gokhale, Pandey, Diringer, Dani, Mahalingam, Shivaganesha Murthy do not discuss the problems of the representation of the numerals and variations in the system. Buhler's, Ojha's, Griinendahl's, Visalakshy's works contain useful material but they provide only brief charts which are quite insufficient for determining the value of the numerals as found in the manuscripts.

3.6 The following ms. is a good example of the use ofboth alphabetic numerals (one of the varieties of Ak$arapalli) and digital numerals in the margin. The manuscript apparently belongs to a transitional period where both types are used.

Figure 10.5. Alphabetic and digital numerals. Johan van Manen collection, courtesy: Kern Library, Leiden.

Picture by the author. See colour secion, Plate XIV.

' 9 In Asoka's inscriptions and other Prakrit inscriptions, however, double and doubled consonants are usually represented by single ones.

20 Practices in inscriptions and manuscripts partly match with the prescriptions of ancient grammatical authorities who differ with each other in several details: Wackernagell896: 110-114, Renou 1961:6-8.

'*",.---- --

VARIETIES OF GRANTHA SCRIPT 201

The various types of numerals used in grantha mss.21 are briefly shown below in table 3. The period attributed to the syllabic and digital numerals (columns Grantha [A] and Grantha [B]) is primarily based on calligraphical and palaeographical characteristics.

Table 10.3

ROMAN TAMIL Grantha[A] Grantha[B] Grantha[C] SYLLABIC ALPHABETIC DIGIT 16-18th CE Biiriikha(ii or 19th CE

dvadasiik$ari

Eh [9 A/KA

2 SL eJ A!KA Q_

3 & II KI g_ 4 lJ-1 I!KI r;u 5 @ 'fuJ U/KU @j@

6 9n '/ U/KD !lrr 7 6T ,:!) B.IKB. err 8 't!::::J B. ..u;..e, 9 fh., GJ'?- L/KL

10/0 Ll) 2 L!KV2 w

21 A descriptive study with all southern numeral systems in general and specific varieties, used in grantha mss., is in preparation (Rath, forthcoming b).

22 In Barakha(ii or dviidasiik$ari style, grantha L I KL is only used to represent 10, not Zero.

202 SARAJU RATH

4. INDICES FOR ATTRIBUTING A DATE AND REGION OF ORIGIN TO A MANUSCRIPT

4.1 Referring to our previous discussion and adding a few points, we give in this section an overview of peculiarities in calligraphy and style that can be particularly helpful in dating a manuscript (which I will discuss here first, in 4.2) and in localising it ( 4.3) .

4.2 The characteristics found in inscriptions, for instance copper-plate inscriptions (from the 11th) and (rare) early manuscripts till the 15th century CE are as follows. 23

i. absence of ii. absence of kakapada mark (as insertion marker); iii. absence of other punctuation marks; iv. absence of avagraha mark; v. absence of halantyam; vi. conjunct consonants: one below the other, both in full form; vii. for diphthongs ai and au, two e matras are placed one above the

other viii. archaic forms of grantha is found; ix. only syllabic numerals are used.

The characteristics of manuscripts of the 16th -18th century CE: i. single sometimes we find it very small in size;

iii.

ii. halantyam (consonant without vowel) is shown by placing the full characters ma, ta, na, ka, ta very small in size at the end; conjuncts: one below other for specific characters like ppa, cca, ccha, lla, tta, jja, tta; also side by side for combinations such as gga,jja,jjha, lla, tta, tta, both characters appearing in a full form; rare use of the avagraha mark: ( ; kakapada mark is used above a fine, two types: _L V;

anusvara mark is given on the top, for instance, Q}-rP- and also at the side of the character f'IN o;

iv. v. vi.

23 These and the following sets of characteristics are mostly overarching ones that apply to all regional varieties (4.3) to the extent they are attested in a period. We will consider here strictly the chronological indications to be derived from the script itself, disregarding indications that may be derived from explicit statements in the colophons, the developmental stage of characters of oth er scripts occasionally inserted, the quality of the pa lm leaf that is used as writing material, etc.

VARIETIES OF GRANTHA SCRIPT 203

vii. repha (small vertical stroke representing r in conjuncts) on the top (for all) (rka), sometimes the consonants are doubled

side by side, sometimes one above other, for instance,

viii. accent marks/4 for instance, udiitta: f"L ix. alphabetic and syllabic numerals are simultaneously found on

the left side margin of mss.

The characteristics of manuscripts of the 19th century CE: i. single for end of one line of the verse: I and double at the

end of the verse: I I; ii. halantyam is shown by turning the last part of the characters t,

n, m, k, t up in a slight curved vertical line. For example,« t, n/ n;

iii. avagraha mark is rarely used; iv. kiikapada mark below the line, between characters: 1\, n ; v. anusviira mostly placed at the side; vi. repha, as a vertical stroke similar to a (short) single is

placed in between the characters (doubled): rma, rca, rja, rpa lT I 1!1 ; ...!LJ I _.!L); £;:? I 1lR; Q_j I d)_J ;

vii. appearance of vedic anuniisika (gum) and candrabindu: ?J \..!); viii. accent marks2 5 (for anudiitta and svarita) 0 L._; ix. the full appears as two vertical lines joined with a small

horizontal bar on the top .J ; x. numerals are presented mostly in digits, occasionally alphabetic.

4.3 With regard to the determination of the region of origin of a mss. or its scribe, I can give here a few simple small hints.

a. Sanskrit texts written mainly in grantha characters but mixed with tamil, malayalam, tulu, telugu and kannada characters wherever possible (on account of phonetic identity or similarity), especially in earlier times, show the influence of the scribe's mother script on his writing.

b. So-called writing mistakes (in the ms where the language is Sanskrit and script is grantha or other) often betray properties of the scribe's first language and script: for instance, forgan-

patma for padma. Bilingual and biscriptual readers may

24 More detai ls in Rath (forthcoming, a). 25 More detai ls in Rath (forthcoming, a).

204 SARAJU RATH

automatically correct such reading and understand the sentence appropriately, even without experiencing a mistake in writing. While working on a manuscript, one therefore needs to have a good knowl-edge of local languages and scripts and their linguistic representation in a particular region.

c. The principle of pagination style fluctuates in every region. For example, the folio -number stands left-side on the front page (recto) of each leaf in the dravidian regions2 6

; in other parts oflndia on the back side (verso) known as sankapr$tha (in eastern region on the right-side top, in the north-western region on the left-side middle or top);

d. South Indian scribes often start their manuscript with sri and/or svasti, where scribes of other parts of India start with om (and just as siddham/svasti is used in the beginning of inscriptions).

5. CONCLUSION

In the southern states of premodern South India, grantha was the spe-cialised script for writing Sanskrit (and Vedic) texts, including royal records and documents. Grantha shows regional differences parallel with the distinct nature of the other scripts (telugu, etc.) with which it was standing in a biscriptual relation; moreover, it shows a nwnber of relatively clearly identifiable stages of development, from the first half of the first millennium CE till early modern times. In the preceding paragraphs we have focused on those among the multifaceted changes in style and calligraphy of the characters of the different varieties of the script, which may serve to determine the relative date of a grantha manuscript, and which have mostly not been analyzed in available studies and handbooks. A few major parameters have been reviewed in this paper which together can help to narrow down the age of a manuscript within a few centuries. If a Sarhvatsara date is given, the determination can become more precise and point to a specific year (within a 60-year cycle).

26 See, for instance, Rath 2005: 55.

VARIETIES OF GRANTHA SCRIPT 205

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bi.ihler, G. 1961. Indian Palaeography. New Delhi . Burnell, A.C. 1878. Elements of South-Indian palaeography from the fourth to the

seventeenth century AD,. Second en l. and improved edition. London: Triibner. Dani, A. H. 2nd edition 1963. Indian Palaeography. Dell1i: Munshiram Manoharlal. Diringer, David. 1953. The Alphabet: A Key to the History of Mankind. New York: The

Philosophical Library. (Reprint: New Delh i, Munshiram Manoharlal, 1996.) Freeman, Richard. 2003. "Genre and Society: 1l1e Literary Culture of Premodern

Kerala." In: Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions from South Asia (ed. S. Pollock): 437-500. Berkeley: Univ. of California.

Gokhale, Shobhana L. 1966. Indian Numerals. Pune: Deccan College Post-graduate and Research Institute.

Gri.inendah l, Reinhold. 2001. South Indian Scripts in Sanskrit Manuscripts and Prints: Grantha Tamil-Malayalam-Telugu-Kannada-Nandinagari. Wiesbaden: Harras-sowitz.

Mahadevan, Iravatham. 2003. Early Tamil Epigraphy (From the earliest times to the Sixth century A. D.). Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University.

Mahalingam, T.V. 1967. Early South Indian Palaeography. Madras. Nampoothiry, N. M. 1983. "A report on Malabar and Kerala Studies, Submitted to

ICSSR, New Delhi." New Delhi. www.maJabarandkeralastud ies.net, accessed on September 2010.

Ojha, G. H. 1959. The Palaeography of India (Hi ndi edition). Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal.

Pandey, Raj Bali. 2nd edition 1957. Indian Palaeography. Varanasi. Pollock, Sheldon. 2007. "Literary culture and manuscript culture in precolonial

India." In: Literary culture and the material book (ed. by Simon Eliot, Andrew Hash and Ian Willison): 77-94. London: 1l1e British Library.

Rath, Saraju. 2005. "A Note on the Taittirlya Manuscripts Belonging to the Van Manen Collection." Acta Orientalia Vi lnensia, 6.2: 52-62.

--. 2006. "Scripts of Ancient India: Siddhamal:l·ka." In: Nyaya- Felici-tation volume Prof V.N. Jha (ed . by M. Banerjee): 717-728. Kolkata: Sanskrit Pustak Bhandar.

--. forthcoming, (a). "Observations on Vedic Accents in Grantha Palmleaf Manuscripts." (To appear in the Proceedings of the Fourth International Vedic Workshop, Austin, Texas, May 24-27, 2007; ed. J. Brereton).

--.forthcoming, (b). "Numerals in Grantha Manuscripts." (Expanded version of a paper presented at the 13th WSC, Edinburgh, 2006.)

Renou, Louis. 1961. Grammaire sanscrite. Tomes I et II rbmis. PhontWque-composi-tion-derivation-le nom-le verbe-la phrase. Deuxieme edition revue, corrige et augmente. Paris: Adrien Maisonneuve.

Sastri, Nilakanta K. A. 2003. [1949, reprinted in 2003.] South Indian Influences in the far East. Chennai: Tamil Arts Academy.

Shivaganesha Murthy, R.S. 1996. Introduction to Manuscriptology. Delhi: Sharada Publishing House.

Sivaramamurti, C. 1966. Indian Epigraphy and South Indian Scripts. Bulletin of the Madras Government Museum, New Series, General Section, vol. 3, no. 4. Madras: Government of Madras. (Second edition, with minor improvements, previous ed. 1948, 1952.]

206 SARAJU RATH

Trivedi, Harish . 2003. "1l1e Progress of Hindi, Part 2: Hindi and the Nation." In: Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions from South Asia (ed. S. Pollock): 958-1022. Berkeley: Univ. of California.

Visalakshy, P. 2003. The Grantha Script. Thiruvanathapuram: Dravidian Linguistic Association.

Wackernagel, Jakob. 1896. Altindische Grammatik. Band 1: Lautlehre. Gottingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.