R3 Reports with Hogan Lovells · Visit R3’s Wiki here. Visit R3's Public Research here. Contents...

Transcript of R3 Reports with Hogan Lovells · Visit R3’s Wiki here. Visit R3's Public Research here. Contents...

1

R3 Reportswith Hogan Lovells

Networks in trade finance: Balancing the optionsAlexander McMynMartin Sim

Visit R3’s Wiki here. Visit R3's Public Research here.

Contents

1. Introduction 12. A brief discussion of DLT 23. Basics of network structure 24. One global network 35. Multiple business networks 46. Key considerations to note 67. Conclusion 10

Disclaimer: These white papers are for general information and discussion only. They are not a full analysis of the matters presented, are meant solely to provide general guidance and may not be relied upon as professional advice, and do not purport to represent the views of R3 Holdco LLC, its affiliates or any of the institutions that contributed to these white papers. The information in these white papers was posted with reasonable care and attention. However, it is possible that some information in these white papers is incomplete, incorrect, or inapplicable to particular circumstances or conditions. The contributors do not accept liability for direct or indirect losses resulting from using, relying or acting upon information in these white papers. These views are those of R3 Research and associated authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of R3 or R3’s consortium members.

R3 Research aims to deliver concise reports on DLT in business language for decision-makers and DLT hobbyists alike.

Leaders in Blockchain, Hogan Lovells has the ability to navigate regulation and think differently with regards to new products and services.

Visit Hogan Lovells’s Website here.

Networks in trade finance: Balancing the options

Alexander McMyn, Martin Sim

November 07, 2017

Abstract

Is a single global network or are multiple business networks the right structure for a dis-tributed ledger ecosystem for trade finance? The answer will reduce uncertainty for marketplayers and enable faster implementation of distributed ledger solutions. This paper considersthe trade-offs between a single universal global network versus multiple business networks.For a universal global network to succeed, regulators would need to come to a consensus overlegal and regulatory standards globally. In the specific context of Asia, multiple interoperablebusiness networks more closely align with the existing diverse regulatory environment.

1 Introduction

What does the future of trade finance look like on distributed ledger technology (DLT)?

Currently, trade finance is a business ecosystem with multiple, isolated networks. Technologyproviders using proprietary digital solutions seek to reduce processing costs, but this has createda series of disconnected networks, bridged by legacy paper-intensive processes.

The resulting complexity in the industry has resulted in four main challenges: illiquid asset pools,costly and error-prone processes, lack of standards, and siloed trade data. As a result, the industryis ripe for disruption, and DLT is a unique technology for solving these legacy problems. The BostonConsulting Group estimates that industry-wide costs can be reduced by $2.5 to $6 billion overthree to five years if institutions adopt innovative technologies such as blockchain-based solutions(International Chamber of Commerce, 2017). Clarity over the structure of a future DLT networkwould certainly help to encourage adoption of the technology.

To avoid recreating a world with isolated networks, stakeholders will need to make decisions abouthow to establish the network framework today. To help regulators and stakeholders make informeddecisions, we consider the trade-offs of the two available options.

The framework choice we explore in this paper is about the diversity of network operators. Shouldthere be only one global network, that every market player, regardless of geography and industry,must join to transact with one another? Or should we promote many business networks, split byjurisdiction, including a subset of market players?

The answer to these questions will define the choices that market players make as they moveforward with this technology, and shape the way in which business is conducted in trade finance.

1

This is particularly critical to Asia where trade is an important driver of development and thereis a lack of harmonised rules in trade finance due to regional diversity.

After a brief discussion of DLT, we compare a single global network to multiple networks. Then,we define business, legal and regulatory, and technical considerations that would underpin thedecision on the network structure.

2 A brief discussion of DLT

The interest in DLT for trade finance comes from the potential connection of digital and jurisdic-tional islands. This will happen in three areas – interoperability, visibility, and standardization.

Interoperability between previously disconnected systems is one of DLT’s main objectives. DLTcan provide an open and shared technology infrastructure for trade data, including bank platforms,e-invoicing, and systems of records, logistics providers and more.

Visibility of data to relevant participants is a second benefit. Participants on a DLT network havereal-time visibility into a single source of truth for trade data, which can help eliminate costlyerrors and agreement disputes. This can greatly reduce fraud risk and compliance costs. DLTalso enables the convergence of data from physical, informational, and financial supply chains. Indoing so, it provides trading parties secure and easy access to verified trade data. The data can beleveraged by buyers and sellers to unlock credit financing, and by financial institutions to providetargeted financing with greater confidence.

Standardization can both solve inefficiencies by putting trade agreements and documents intodigital smart contracts, which allows for automated, efficient and secure management of dealsacross global counterparties. Trade assets can be issued, traded and settled in real-time betweentrading parties globally. With such tangible benefits, market players are increasingly exploring theuse of DLT use-cases in trade finance, many are developing a solution on the path to production.

3 Basics of network structure

The shape of the network structure will determine the rate of adoption of DLT. Without a clearunderstanding of the network structure, the resulting uncertainty will make it difficult for marketplayers to chart a clear path to adoption. Clarity gives key stakeholders the confidence to beginstrategizing for the future in the push towards adoption.

Currently, there are two different outcomes for the network structure. The first outcome is that of aglobal network, which would be run by a single network operator. In this model, all market playersin the industry, ranging from financial institutions to ports to regulators, will be on-boarded ontothe same network before they can do business with one another.

The other outcome is an ecosystem with many disparate networks. This is similar to the worldwe live in today, but with the core difference that DLT networks can build in interoperability.While the trade finance networks of today are isolated and independent of one another, a tradefinance network built on DLT promises common standards and interoperability between differentnetworks.

Since Asia is made up of a diverse set of countries, it has been difficult for all jurisdictions to agreeon a single set of business rules in order to form a universal network. Different countries will havevarying opinions on how a trade finance network should be run. This difficulty is magnified whencountries outside Asia are brought into the equation. As such, we foresee multiple interoperablebusiness networks emerging out of Asia from the outset.

Once one outcome has momentum, it will be very difficult, if not impossible, to change the structureof the network. Hence the options have to be carefully considered and weighed against each otherin the early stages of implementation.

2

3.1 Components of a network

A network will typically comprise four types of nodes: a participant, doorman, notary, and oracle.

Participant nodes include regulators, banks, port and customs among others. A participant of adistributed ledger network, e.g. a bank, will run a regular node. This allows them to transactwith other participants, send and receive digital assets, and run shared business logic. Regulatornodes can receive real-time read-only “drop copies” of transactions between entities they oversee.Regulator nodes can either be party to a transaction (and approve them) or non-party and receivenotification only (reporting). A participant node can be a member of one or more business networks,running one or more applications.

The second type of node is a doorman service/root certificate authority. Participation in a networkrequires nodes to possess an identity that is unique throughout the network, and for the nodesto be able to reliably assert that identity in their interactions with peer nodes and other networkservices. The certificate authority function is provided by a doorman service. The doorman servicereceives requests from nodes to join its network via certificate signing requests. The service willthen verify the contents of the request to ensure the node’s entitlement to assert the requestedidentity as well as its eligibility to join the network. If this verification step is successful, the servicewill return a signed certificate to the node. That certificate may then be used by the node to attestto its identity in its interactions with other nodes and services, and by its peers to validate anysignatures that it may append to messages or transactions.

The third type is a notary cluster. These are several nodes operating in concert, according to ashared consensus algorithm such as RAFT, PBFT, and others. The notary provides independentassurance that any given transaction is unique and doesn’t represent a double spend. When aparticipant wants to commit a transaction on the ledger, a signature from the notary service isrequired. The point of finality is reached when the notary signs the transaction.

The final type of node is the oracle. These are trusted third parties that provide market datarelated to the contract code execution. This could be a market data provider for certain agreedupon rates.

Regardless of the structure, the DLT network will be made up of the same types of nodes asdescribed above. In the next two sections, we will take a closer look at the two options: a globalnetwork and multiple interoperable business networks.

4 One global network

A single global network is one with every industry player on the same network, regardless ofjurisdiction, asset class or business function. This network will be managed by a single operator.

Logistically, each transacting entity on the system would run its own node on the universal network,and be able to communicate and transact with other nodes. Since the network is private andpermissioned, each node has to establish its unique identity, and prove without a doubt that theyare who they claim to be. This service is provided by the doorman service.

Once a global network is established, nodes can transact with each other seamlessly across differentindustries and lines of business. For example, HSBC Singapore can run a node on the globalnetwork and can transact with its counterparties across many different businesses (e.g. tradefinance, capital markets) and jurisdictions, and any type of asset (e.g. cash, derivatives) can befreely traded between nodes. The system could also allow for each actor in a transaction to operatetheir own node, including, for example, the corporate customers of financial institutions, with therelevant smart contracts controlling the interactions according to the specific needs of each actor.

The experience of SWIFT informs our thinking about global network design in trade finance.SWIFT is a global network in the same style as we are envisioning for DLT. It is privately-run,and connects 11,341 financial institutions worldwide (SWIFT, 2017). In the trade finance space,SWIFT offers a wide range of messages, which are adopted globally. Why would a bank considerDLT instead of SWIFT?

3

The primary difference is that SWIFT is purely a messaging system and does not hold accounts formembers. It also does not perform any form of clearing, settlement or funds transfer. All paymentmessages need to be settled through correspondent accounts that institutions hold with each other.A DLT network would be more than just a messaging system. A fully developed DLT network willmodel fungible assets, including cash, and enable trading among different parties on the ledger.

From a regulatory perspective, a DLT network will be treated very differently from SWIFT. SinceSWIFT is neither a payment nor a settlement system, it is not regulated, and is instead subject tocooperative oversight by central banks (SWIFT, 2017). Because a fully developed DLT networkwill, by design, include asset and funds transfer, it will require stricter regulatory control from theoutset, which makes the choice of network structure even more important.

5 Multiple business networks

The other possible setup of a DLT ecosystem in trade finance would be a model with multipleinteroperable business networks. These networks would be set up for a specific jurisdiction, assetclass or industry.

A business network is a group of actors or participants that transact with each other for somedefined purpose, using one or more applications. Each network is managed or co-ordinated by aBusiness Network Operator (BNO). The BNO is expected to oversee the business network accordingto defined rules. The BNO also controls access to the network. Some form of Business NetworkAgreement is likely to be used to instantiate the rules and define the roles of the various actors inthe network.

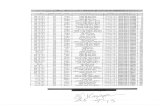

Figure 1: Example of a possible interoperable business network in trade finance

As shown in Figure 1, business networks are typically initiated by a group of institutions that wishto conduct business with each other on a DLT platform (left side). The first step is to identify aBNO. This may be a joint entity formed by the initial participants or a third party selected for

4

this purpose. The next step is to select a system delivery partner to handle the application buildand integration into existing systems.

In a typical trade finance business network, the participants would include varying types of insti-tutions such as banks, ports, customs, exporters, importers and regulators, each running their ownnode. The network operator is likely to be a trusted third-party. These third parties can buildand maintain proprietary trade finance applications and limit the usage of these applications tothe participants on their business networks.

However, the current lack of common rules and standards in DLT may re-create digital islands. Byallowing networks to act unilaterally with respect to network configuration, it may be very difficult,if not impossible, for business networks to interact freely. This may result in individual groups ofDLT pioneers creating their own “walled gardens” to run specific applications for a defined andpermissioned set of participants and transactions.

Interoperability is a key hurdle that exists for the multiple network model. If a multiple networksolution is to be adopted, the value proposition of DLT in trade finance depends on having themultiple networks interoperate with each other. Interoperability can involve integration with ex-isting systems, compatibility between different platforms (e.g. Corda and Fabric) or interactionsbetween different networks on the same platform (Lewis, 2017). In electronic payments, for exam-ple, interoperability can refer to three levels: the scheme (an electronic funds transfer from onebank will be accepted at the recipient bank), the network (a holder of a domestic credit card canuse it in a foreign country), and the system (merchants accept various credit cards) (InternationalTelecommunication Union, 2016).

Interoperability constraints have the potential to limit the efficiency of asset exchanges betweencounterparties and asset exchanges for other assets (Buterin, 2016). DLT interoperability needs tosolve both existing problems of inconsistent static data representation as well as future problemsthat will arise with the technology. For example, in a world of shared smart contracts, solutionsmust provide active alignment of states changing (representation of events and processes) in addi-tion to states at rest. Interoperability complexity depends on whether network participants wantto keep two ledgers in sync (either within the same platform or between different platforms), orsimply allow the ledgers to provide information to each other.

The specific interoperability requirements for the DLT landscape will vary with the market struc-ture. Traditional forms of third party bridging between DLT networks is possible. However, suchan approach would re-introduce a number of risks, and would be architecturally intensive, re-introducing many of the problems that DLT intends to resolve by recreating a somewhat similarinfrastructure to that in effect today.

To address the interoperability challenge, one potential solution is to create a common set ofrules and technical standards within which multiple business networks operate. Let’s call this theCompatibility Zone. It is a technical network where multiple business networks can run on a singleplatform, use common services, and conform to common rules and standards. The intention is toenable separate business networks to interoperate with one another under common rules.

To make a Compatibility Zone work, there would need to be a shared doorman service, whichprovides the initial identity verification service for institutions that want to join, as well as acommon set of trusted notaries. The global, shared doorman service will need to control approvedparticipant nodes in the Compatibility Zone and provide routing information without compromisingprivacy or confidentiality. A key point to note is that participants on-board each node only onceto the Compatibility Zone, and this will enable them to join any number of business networks forwhich they meet the entry criteria set by the BNO.

An example of how business networks could interoperate using this model is seen in Figure 2.HSBC could be a member of a cash business network, which is run by the Hong Kong MonetaryAuthority (HKMA). It uses some of this cash to settle an obligation to Development Bank ofSingapore (DBS) arising out of a contract on a trade finance business network that is operated byFinastra. Subsequently, DBS could use that cash to fund a syndicated loan on a third businessnetwork. That cash could move seamlessly from one business network to the other with only theinformation needed to prove its provenance moving from one party and one business network tothe next. And this is not only limited to cash, but can include self-sovereign identity objects,

5

Figure 2: Network structure with two interoperable business networks

securities, and any asset, deal, contract or other shared fact on the ledger that more than oneapplication knows how to understand. The key to this is the conformity of each business networkto the rules and technical standards set forth by the Compatibility Zone.

Why would network operators want the additional layer of a Compatibility Zone? Regulatorsmight want to group institutions in the same jurisdiction, which allows for efficient monitoring.Technology providers might want to protect their commercial interests by limiting participation inthe business networks to only their customers.

6 Key considerations to note

There are many possible reasons why network operators might prefer one option over the other. Inthe table below, we give a brief overview of the considerations that key stakeholders (e.g. banks,regulators, ports, network operators, and exporters/importers) have when deciding on the networkstructure.

6.1 Business considerations

There are three key business considerations that operators will need to review: governance, com-plexity, and cost.

6

6.1.1 Governance

In a global universal network, any single operator controlling access has monopoly influence andpricing power. Due to network effects, it will be difficult for participants to leave the networkonce a critical mass is reached. This can lead to a service provider monopoly with outsized pricingpower, and potentially cause anti-trust issues (Benos, Garratt & Gurrola-Perez, 2017).

Furthermore, regulators and central banks may be concerned with the systemic economic im-portance of large-scale financial networks, where a single powerful controller sits outside of theirinfluence. Regulators and central banks may be concerned about fair and open access, continuityand systemic risk to the financial system and their instinct may be to either not allow progress orto impose control after establishment, as is the case with SWIFT.

The ability to support multiple business networks within a single Compatibility Zone can overcomethese issues. The concept of independent business networks allows regulatory bodies and privateinstitutions to have greater control over their own business networks. The role of the networkoperator for the Compatibility Zone is simply to maintain standards for the Compatibility Zone asa whole, and identify new nodes on the Compatibility Zone, rather than discriminate over whichinstitution can join the Compatibility Zone. The shared doorman service for the CompatibilityZone will only seek to verify the identities of the requesting institutions. It is effectively an identityverification service and will not bar an institution from joining as long as the institution can proveits identity and is not likely to bring the Compatibility Zone operator into disrepute.

That said, the thinking around the design of the Compatibility Zone will evolve as market playersweigh the pros and cons of various approaches, and seek to maximise their commercial benefits. Wemight imagine that the operator that runs and maintains the zone takes a member-led cooperativestructure. Alternatively, it could be run by an existing utility or a new utility could be created.There must be consensus among industry participants to ensure that the Compatibility Zone isrun in a way that is fair and acceptable to all.

Returning to the example of a trade finance business network, Finastra, as a technology provider,will maintain overall control over its business network. It can determine which institution gets totransact on its network by limiting the usage of its proprietary applications to only participantnodes. In addition, Finastra can control the branding of the network. Instead of being labelled asa generic business network, Finastra has free rein to brand the network the way it wants, thereby

7

increasing its visibility and brand equity. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, Finastra will beable to control the pricing on its own network. Since it is the BNO, it can charge participants afee to join the trade finance network, which it is unable to do on a universal network. There isless concern over anti-trust issues because there will be multiple BNOs that run a trade financenetwork (e.g. Bolero), which will reduce the pricing power of any one institution.

6.1.2 Complexity

For a global universal network, all participants need to go through the on-boarding process onlyonce. As long as the institutions pass the identity checks performed by the doorman service andreceive the signed root certificate, they will be able to communicate and initiate transactions withother participant nodes.

In a world with multiple business networks underpinned by a global Compatibility Zone, therewill be an extra step in the on-boarding process. Similar to having a global universal network,participants need to on-board onto the global Compatibility Zone. At this step of the process, thenetwork operator for the Compatibility Zone will verify the identity of the institution and map thenode to its legal entity.

Additionally, the concept of passporting or sponsoring new members to the Compatibility Zoneby BNOs is possible to ensure a seamless process for new joiners to the Compatibility Zone. Thislightweight verification is intended to front-end the more detailed checks that BNOs may want toexercise by way of due diligence when nodes request to join specific business networks. Therefore,participants need to go through a two-step process before they can begin transacting with otherparticipants. In addition, the number of times participants have to go through the on-boardingprocess can increase depending on the number of business networks they have to be on. Take forexample HSBC. If they have to join multiple different business networks (e.g. cash and paymentsnetwork, trade finance network, securities network), they will have to go through the on-boardingprocess multiple times with different BNOs. This adds much complexity and inconvenience.

6.1.3 Costs

Costs will always be one of the key considerations for participants. It is reasonable to expect on-boarding costs to be higher in a world with many interoperable business networks given a two-stageon-boarding.

At the first stage, participants will have to pay the network operator of the Compatibility Zonea fee to be on-boarded. However, this step of the process would not give participants access tobusiness networks. To gain access to specific business networks where the BNOs limit the entry ofnodes through their proprietary applications, participant nodes will have to pay another upfronton-boarding fee. The costs can quickly snowball when a participant needs to join multiple businessnetworks.

For example, DBS would need to pay a fee to join the Compatibility Zone, and then pay additionalfees to join a trade finance network by Finastra, a cash business network by the Monetary Authorityof Singapore, a securities business network by the Stock Exchange of Hong Kong and so on.Furthermore, DBS would likely have to pay a subscription fee to the different BNOs to maintainthe business networks and applications, which will further increase the costs. In contrast, DBSwould only have to pay an on-boarding fee once to join a global network, and a regular subscriptionfee to one global network operator to maintain the network. Therefore, costs are expected to behigher for participants in a world with multiple interoperable business networks.

6.2 Legal & regulatory

The multiple interoperable business networks versus single global network debate also has regula-tory oversight implications. Regulation in Asia is currently managed on a country-by-country basis– there being no overarching organisation, such as the European Union, or federation of states,such as the USA, capable of bringing forward common regulation across the continent. Given the

8

disparity in sophistication between the most advanced and the least developed economies in Asia,any attempt at imposing a set of common regulations covering the management of trade financenetworks would be difficult to achieve.

Achieving such common standards would likely need to start at a "lowest common denominator"position across the various countries – making any region-wide rule set potentially too limitedfor the more advanced markets. The major financial centres in Asia pride themselves on beingefficiently regulated. It is difficult to see the national regulators making concessions on standards orceding authority over regulated activity to assist less sophisticated countries in the implementationof a common regulatory framework. This makes the formation of a universal network less feasible.

All of the above seems to lead strongly in the direction that the only possible solution from aregulatory point of view is to organise multiple interoperable networks along national lines, eachregulated by the relevant national authorities. However, the goal of good regulation should beto assist the market in appropriate development, rather than to hinder it. No matter which ofthe multiple networks or single network route eventually dominates, it is unarguable that the bestsolution from a market perspective will provide for the functioning of a network or networks acrossnational borders. It is therefore incumbent on regulators to find a satisfactory solution.

From a regulatory perspective, both options are possible,

(a) Regulation of business activities within a country’s borders: A single global network on whichlimited regulated activity takes place – with national regulators keeping oversight of institu-tions or regulated activity on the network taking place within their own jurisdictions. Forexample, HSBC Hong Kong can be on the global network, and transact with its counter-parties globally, yet only regulated activity that occurs within Hong Kong borders would bemonitored and regulated by HKMA; or

(b) Regulation through business networks: A business network (maybe segregated by country)over which regulated activities within the country are performed, linking to a SWIFT-likeglobal standard network (the “Compatibility Zone”) for all unregulated steps. Commercialparties would only need to be nodes on the “Compatibility Zone”, with the parties performingregulated activity in a jurisdiction needing to be a member of that jurisdiction’s regulatedbusiness network also. Given that financial institutions, which would perform most of theregulated activity, are already well accustomed to interacting with regulators in each marketwhere they operate, it may be that this would be an acceptable outcome.

That being said, we believe the "two tier" system of a Compatibility Zone and business networkswould also potentially resolve a number of other legal issues around cross border networks: disputesaround entries on a national network could be resolved by reference to the dispute resolutionmechanisms of the relevant nation, whereas those in relation to activities on the global networkcould be resolved via an arbitration body not aligned to a given country, for example. Equally,flows of sensitive data might be better managed on national networks – preventing issues arising ontransmitting it cross border. Finally, were the Compatibility Zone become systemically important,it could, like SWIFT, be the subject of an agreement between multiple local authorities as to itsoversight.

6.3 Technical considerations

The network structure decision will have several important technical impacts. These include mostprominently the validity of notaries and common technical standards.

6.3.1 Notaries

For a notary to carry out its function, it is imperative that notaries in any business networkare trusted by notaries in another. Otherwise, it is possible that notaries in one of the businessnetwork will question the validity of a transaction that occurred in another network, and preventtransactions from being finalized.

9

For example, Standard Chartered Bank can be a participant node on the Singapore cash networksupervised by the Monetary Authority of Singapore and also a participant node on a Finastratrade finance network. The Monetary Authority of Singapore will designate its own notaries forits cash network, which Finastra may not necessarily trust because it is not familiar with them.Therefore, it will be difficult for Standard Chartered Bank to use the money in the cash businessnetwork to pay for its obligations in the trade finance business network. The notaries in the tradefinance business network will not be able to sign off on the transaction as they are not confidentthat the cash has not been double spent, even if it was verified as unique by the notaries on the cashbusiness network. This could lead to the isolation of the various business networks. To mitigatethis issue, one possible solution is to have a set of globally trusted notaries that each BNO canselect from. This ensures that the notaries trust each other, and will sign off on transactions thathave been verified by other notaries.

The problem will not be present on the universal network. On a global network, there will be a setof globally trusted notaries, similar to the solution we proposed above. As such, we can guaranteethat notaries will trust each other and transactions can be completed.

6.3.2 Technical standards

For interoperability between multiple business networks, it is important that we adopt commontechnical standards globally. This underpins the whole concept of Compatibility Zone. This maybe difficult to broker globally. Views and opinions will differ and we accept that some jurisdictionswill want to start out with full control of the entire system. They will not buy into the concept ofa Compatibility Zone, and will be suspicious of the concept of free and easy movement of assetsacross borders. Nonetheless, it is important that global technical standards are established early,and be allowed to evolve as requirements and the regulations governing the industries change.

This issue will also exist for a global network. To give participants confidence that they cantransact with one another on the global network, common standards have to be agreed upon andestablished from the beginning, which again is difficult as different participants will have differentopinions.

7 Conclusion

In the context of Asia, there is currently no single organisation capable of bridging the regulatoryand legal differences between countries. Each country has its own set of regulation and businessrules surrounding trade finance. It makes more sense to have multiple business networks, wherethe regulators and network operators in each jurisdiction will have control and oversight over itsown business network. The most critical aspect is the interoperability between different businessnetworks, which can be achieved with the adoption of global technical standards.

However, if regulators are able to come to a consensus over common laws and regulation, a globaluniversal network will work, and this option will result in lower costs and less complexity.

Ultimately, institutions and regulators have to weigh the business, regulatory and technical con-siderations of both options, and decide on the one that best suits the needs of the trade financeindustry.

10

References

[1] International Chamber of Commerce (2017). Rethinking Trade & Finance. ICC Global Surveyon Trade Finance

[2] Buterin, V. (2016). Chain Interoperability. R3 Research Paper.

[3] Lewis, A. (2017). Decrypting Interoperability. R3 Insights.

[4] SWIFT. SWIFT Oversight.

[5] SWIFT (2017). SWIFT in figures. SWIFT Fin Traffic & Figures.

[6] Benos E., Garratt R. & Gurrola-Perez P. (2017). The economics of distributed ledger technologyfor securities settlement. Bank of England Staff Working Paper, No. 670.

[7] International Telecommunication Union (2016). Payment system oversight and interoperability.Focus Group Technical Report.

11

Is an enterprise software firm using distributed ledger technology to build the next generation of financial services infrastructure.

R3's member base comprises over 80 global financial institutions and regulators on six continents. It is the largest collaborative consortium of its kind in financial markets.

Is an open source, financial grade distributed ledger that records, manages and executes institutions’ financial agreements in perfect synchrony with their peers.

Corda is the only distributed ledger platform designed from the ground up to address the specific needs of the financial services industry, and is the result of over a year of close collaboration between R3 and its consortium of over 80 of the world’s leading banks and financial institutions.

Consortium members have access to insights from projects, research, regulatory outreach, and professional services.

Our team is made of financial industry veterans, technologists, and new tech entrepreneurs, bringing together expertise from electronic financial markets, cryptography and digital currencies.

![COMPUTER ORGANIZATION & ARCHITECTURE · mov r3, h r3 m [h] add r3, g r3 r3+m [g] div r1, r3 r1 r1/r3 mov x, r1 m[x] r1 page 4 of 16 knreddy computer organization and architecture.](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/6144b5c334130627ed50859a/computer-organization-architecture-mov-r3-h-r3-m-h-add-r3-g-r3-r3m-g.jpg)