Pulse Magazine - Issue 11

-

Upload

rzim-europe-headquarters -

Category

Documents

-

view

236 -

download

3

description

Transcript of Pulse Magazine - Issue 11

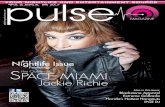

R Z I M E U R O P E ’ S M A G A Z I N E

Introducing Tanya Walker

Discipleship remixed:

The art and practice of huddling

www.rzim.eu

WHY DOES TRUTH MATTER?

John Lennox’s

Lent talk for Radio 4

Evangelism in the public sphere

ISSUE 11 | SUMMER 2012

SUMMER 2012 | PULSE ISSUE 11

Our speakers are trained to respond to the objections and questions that people have about faith, so that lives

might be transformed by the gospel message. We also help to resource the church, through apologetics articles

and talks, engagement with the media, training events and academic courses through the Oxford Centre for

Christian Apologetics (OCCA). Furthermore, we run an Associates Programme for emerging evangelists around

Europe and we contribute to the work of Wellspring International, RZIM’s humanitarian organisation.

SUMMER 2012 | PULSE ISSUE 11

RZIM Europe is the working name of RZIM Zacharias Trust, a charitable company founded in 1997 that is limited by guarantee and registered in England. Company No. 3449676. Charity No. 1067314

PRINTER | VERITÉ CM LTD

DESIGN & ILLUSTRATION | KAREN SAWREY

PHOTOGRAPHY | JOHN CAIRNS

STOCK IMAGES | ISTOCKphoto

The Oxford Centre for Christian Apologetics (OCCA) is a partnership between RZIM and Wycliff e Hall, a Permanent Private Hall of the University of Oxford.

RAVI ZACHARIAS, PRESIDENT OF RZIM AND SENIOR RESEARCH FELLOW AT WYCLIFFE HALL

MICHAEL RAMSDEN, EUROPEAN DIRECTOR OF RZIM AND DIRECTOR OF THE OCCA

ALISTER MCGRATH, PRESIDENT OF THE OCCA

AMY ORR-EWING, UK DIRECTOR OF RZIM AND CURRICULUM DIRECTOR OF THE OCCA

JOHN LENNOX,ADJUNCT PROFESSOR AT THE OCCA

OS GUINNESS, SENIOR FELLOW AT THE OCCA

VINCE VITALE, SENIOR TUTOR AT THE OCCAAND SPEAKER FOR RZIM

TOM PRICE,TUTOR AT THE OCCAAND SPEAKER FOR RZIM

SHARON DIRCKX, TUTOR AT THE OCCAAND SPEAKER FOR RZIM

MICHELLE TEPPER, SPEAKER FOR RZIM

TANYA WALKER, SPEAKER FOR RZIM

VLAD CRIZNIC, DIRECTOR OF RZIM ROMANIA

RZIM Europe, 76 Banbury Road, Oxford, OX2 6JT T: +44 (0)1865 302900 F: +44 (0)1865 318451 www.rzim.eu

our team includes:

HELPING THE THINKER BELIEVE AND THE BELIEVER THINK

RZIM Europe is an evangelistic organisation that seeks to engage hearts and minds for Christ.

SUMMER 2012 | PULSE ISSUE 11

Th e enlarged format enables us to bring you even more content, including the latest news about about RZIM Europe and the Oxford Centre for Christian Apologetics (OCCA), as well as articles on evangelism and apologetics.

WELCOME TO THE NEW LOOKpulse

PULSE ISSUE 11 | SUMMER 2012

CONTENTSINTRODUCING

TANYA WALKER 4WHY JESUS?:

BOOK REVIEW 7EVANGELISM

IN THE PUBLIC SPHERE 8JOHN LENNOX’S

LENT TALK FOR RADIO 4 10WHY DOES

TRUTH MATTER? 13OCCA ARTICLES:

DISCIPLESHIP REMIXED:

THE ART AND PRACTICE

OF HUDDLING 16STORY AS AN

APOLOGETIC 18RELIGION FOR

ATHEISTS: BOOK REVIEW 20DATES FOR

YOUR DIARY 23

IN THIS ISSUE:

THE MEDIA

John Lennox gave one of Radio 4’s

Lent Talks on science and faith which

provoked the biggest response

to date on his website. Read the

transcript of what he said on page 10.

EVANGELISM TODAY

What opportunities are there for

evangelism in modern Britain today

and why does truth matter anyway?

The former question is tackled by

Amy Orr-Ewing (page 8), whilst the

latter is addressed by Os Guinness

(page 13).

WHY JESUS?

Ravi Zacharias’ latest book, entitled

Why Jesus?, addresses the rise of mass-

marketed (New Age) spirituality in the

West. A review can be read on page 7, whilst another, on Alain de Botton’s

Religion for Atheists, can be read on

page 20.

INTRODUCING TANYA WALKER

Meet the newest member of RZIM

Europe’s team and learn about her

passion for evangelism and her hopes

for the role (page 4).

THE OCCA

Frog Orr-Ewing explains how the

system of ‘huddling’ works, which

is used to encourage spiritual

development at the OCCA (page 16). This is followed by an article on

‘Story as an Apologetic’ by an

alumnus, Theo Brun (page 18).

DO YOU HAVE A QUESTION?

Do you have a diffi cult question

about Christianity you would like

us to answer? If so, please email it

Each subsequent edition of Pulse will

include a reader’s question answered

by a member of the RZIM team. We

will keep a record of all of those that

are submitted, so that we can address

the topics that people are most

interested in.

Simon Wenham

RESEARCH CO-ORDINATOR

INTRODUCING

TANYA WALKER

INTERVIEW BY SIMON WENHAM

GENUINELY, I THINK, FOR ME, IT’S AS SIMPLE AS:

I FIND RELATIONSHIP WITH GOD EXHILARATING.

SUMMER 2012 | PULSE ISSUE 11

PHO

TOG

RAPH

S FO

R A

RTIC

LE B

Y JO

HN

CA

IRN

S

SIMON:

Firstly, we'd like to welcome you to the RZIM team! For those who are not familiar with you, could you tell us a little about how you became connected with the ministry?

Tanya: Thank you! I’ve had a number

of connections with RZIM over the

past twenty years or so. I fi rst heard

Ravi Zacharias speaking when I

was about eight years old and the

teaching completely blew me away.

I think what captured my heart about

it was that it was more than just

listening to a gifted speaker – the way

he communicated truths about God

really revealed more of the beauty of

God, and it had a transformative eff ect

on me. Ever since then I’ve really loved

this ministry, and often thought of it

and prayed for it. The next signifi cant

step for me was coming to Oxford

for my undergraduate degree and

getting to know Michael and Anne

Ramsden, who had a huge impact on

my life. I did the training weekends

and various other things with the

ministry, and the friendship continued

to grow after university. And then

I think it was about fi ve or six years

ago now, that Michael asked me

to join the Associates Programme,

and there’s been more of a formal

involvement in the team since then.

So there are a number of diff erent

avenues, which make me feel like

I’m part of the family already.

So you were brought up a Christian?

Yes, I don’t remember a day when I

haven’t known Jesus as my personal

Lord and saviour. I was born in Iran

during the Iran-Iraq war and it was

a diffi cult context. But I’ve been

incredibly blessed with parents

who are amongst my heroes of the

faith – they really walked the talk,

and they’ve always lived with a real

expectation and excitement about

seeing people coming to Jesus,

both personally and in the church-

planting ministry that they lead. So

I had a very privileged upbringing

in experiencing the reality and the

adventure of walking with Jesus when

I was young. We moved to the UK

when I was seven, and I remember

being very evangelistically motivated

even then. I don’t think I really

considered the intellectual aspect of

the faith, though, until my late teens,

when I regularly listened to Ravi. So

I’ve been a Christian ever since I can

remember, but I’m not sure I would

have been able to give a reasoned

defence for my beliefs until later.

What would you say to someone who says that you - or anyone for that matter - are only a Christian because you were brought up that way?

Well, it’s not an original claim, in

that it’s grounded in a Foucauldian

understanding of discourses of power

that are said to shape us as individuals

and the ‘truths’ of our cultures. Of

course it can be easily turned around

to the person making the claim – in

the sense that they don’t believe in

God because of their background or

culture! But it is more fundamentally

fl awed than that. I think I would want

to redefi ne the debate and bring

us back to the question of truth.

Regardless of why I believe what I

believe, the real question is: ‘Is there

such a thing as truth and can we

know it?’ And if we can know it, how

can we go about fi nding out what is

true? That’s where I’d want to have

the discussion and that’s why I think

apologetics is so important, because

we have to be ready to ask some hard

questions – both of ourselves and of

other people. If I don’t agree that I

am simply a Christian because of my

background – then I need to be ready

to engage with the real reasons of

why I am a Christian, and be ready to

give a reasoned defence for my faith.

When you studied philosophy (as part of your Philosophy, Politics and Economics degree) did anything challenge your faith?

A lot of people assume that if you

study philosophy you’re bound to

lose your faith, because there are

all these hard questions that are

diffi cult to answer. But I found the

opposite. I left Oxford with such a

confi dence in my faith – I discovered

that even one-to-one tutorials with

world-renowned philosophers could

not shake the solid ground that is

the gospel. I remember one of the

most helpful pieces of advice that

Michael Ramsden ever gave to me

was not to try and philosophise

outside of theology, but to stick to

the Bible and what it says. If you try

and make the Bible fi t into what you

think is philosophically sound, you

will fi nd that both your theology and

philosophy eventually run aground.

But philosophy works when theology

is true, even when we can’t see it

straight away – and that truth helped

me in more than one tutorial!

So why has it taken you so long to join the team?

It feels like it’s been a convoluted

route, to say the least! Although

Michael had mentioned the job to me

a while ago, and I knew it would be

my dream job, I had felt God lead me

towards postgraduate research. Toby

– my husband – and I had prayed and

thought about the various possibilities

and we were confi dent that I should

pursue a PhD, and that’s what God

had for us in this particular season.

So that’s what I’ve been doing these

past few years. It’s defi nitely been a

challenge – as well as an adventure

– but I’ve recently completed my

PhD thesis, which has meant that

I’ve been freed up to join the team.

SUMMER 2012 | PULSE ISSUE 11

5

SUMMER 2012 | PULSE ISSUE 11

6

....ENGAGING BOTH THE MIND AND

THE HEART

Can you tell us a bit more about the research?

Yes, it’s essentially an ethnographic

study that looks to the workings

of the Shari’a councils in Britain,

and asks some questions about

the motivations, the circumstances

and the reasoning of the women

who use them. I look at some of the

political and sociological implications

of the councils and their growing

role in the West, as well as some

of the political theory on the role

of religion in the public sphere,

the rights of minorities, issues of

freedom of religion, liberalism, and

so on. There’s still a lot more to be

known and discussed in the fi eld,

but I think my research makes a

signifi cant contribution to our

understanding of the dynamics that

are involved in the call for a greater

recognition of Shari’a law in the West.

What motivates you to do evangelism?

Genuinely, I think, for me, it’s as

simple as: I fi nd relationship with

God exhilarating. There is nothing

like being loved by God and loving

God. It’s not that I have this deep

sense of wanting everyone to

live a certain way or to conform

to a certain morality – it’s just the

understanding that being with God

is the most amazing place to be and

I cannot imagine what it would be

like to live without God. That’s what

motivates me to do evangelism.

What role does apologetics play in this?

For me, growing up, it was primarily

the experience of God that fi rst

captured my heart, but I think I would

feel very uncomfortable with basing

my whole existence on something if it

did not make sense. And it’s the same

in our culture – people don’t just

want an experience of God, they want

to know that it makes sense, that it

can engage their minds – and this is

actually a very Biblical desire!

I love that the greatest commandment

is not just to love God with all our

heart, but to love him with all our

heart, soul, mind and strength. So I

think apologetics has to go hand-

in-hand with a genuine experience

of the love and reality of God. It is

about knowing that you are building

on a sure foundation, engaging

both the mind and the heart.

What are your hopes for the new role?

I have so many hopes and dreams for

the coming years. I cannot imagine

anything more wonderful than telling

people about Jesus for your job and

helping to instil confi dence about

the Gospel in what is, at times, an

unsettled and insecure church. But

I think maybe my overriding hope

for this role comes down to what I

call the ‘stand up and clap’ moment.

I remember when I fi rst heard Ravi

speak, it would make me feel like

standing up and clapping – and it

was applause that wasn’t directed at

Ravi, but at something of the beauty

of God, or of the Gospel, that my heart

had connected with in the moment.

It was eff ectively spontaneous,

child-like, worship. I hope that when

I speak I can help to similarly reveal

something of the nature of God, his

truth, his grace and his wisdom, that

incites worship – both for the believer

who’s lived with God for many

years, but maybe sees something

new of him, and for the unbeliever

who sees him for the fi rst time.

How can we pray for you?

I have one particular prayer that I have

been praying as I get started. I am

very aware that talks get written, we

think, study and research to convey

the message of the gospel, in all sorts

of diff erent ways – but it’s really all

words unless the presence of God

and the power of the Holy Spirit

come with us. So my biggest prayer

is that whenever I am speaking it’s

not just good ideas, concepts, and

words that I am conveying, but that

the presence of God is with me and

that the power of the Holy Spirit is

convicting heart and minds. That is

my daily prayer and I would love it

if others would pray that too.

SUMMER 2012 | PULSE ISSUE 11

7

Although this can mean a range

of things, the chances are it may

have been uttered by someone

who embraces a form of New

Age spirituality, whether they

name it as such, or not.

This is a religious movement that few

Christians know much about, which

is why Ravi Zacharias has addressed

the topic in his latest book, Why

Jesus? Rediscovering his truth in an

age of mass marketed spirituality.

The work is partly a critique of the

New Age movement and partly

a critique of western culture.

Zacharias points out that the kind

of ‘smorgasbord’ spirituality that is

prevalent today and espoused by the

likes of Oprah Winfrey and Deepak

Chopra, simply does not stand up to

scrutiny. The proponents of ‘Weastern

spirituality’ (his word for the melding

of Western Materialism and Eastern

spirituality) use language that may

sound exotic and profound, but often

the precise meanings remain elusive.

Some of the teachings have even

been given a contemporary twist by

the adoption of pseudo-scientifi c

terms, such as Chopra’s ‘quantum

healing’, which attempts to align

Hindu metaphysics with modern

physics - a link that is strongly denied

by scientists. Zacharias reminds us

that we should not forget that the

New Age movement has at its core a

Hindu-pantheistic worldview, which,

unlike Christianity, makes humans

less than they should be and not

more. There is no such thing as ‘I’

in pantheism, for example, which

means that it lacks the transformative

relationship that is at the heart

of Christianity. Furthermore, it

misunderstands and misuses logic, it

cannot sustain the idea of the sacred

(or even defi ne evil) and it fails to give

grounds for why love should occur.

Like Alain de Botton (see page 20), Zacharias also admonishes the

materialistic culture of the West, which

has created a spiritual vacuum that

has been exploited by the ‘wellness’

market. There has also been a reaction

to the perceived shallowness and,

at times, hypocrisy of the church.

So-called Christians have sought to

reshape Jesus according to their own

agenda, whilst religious institutions

have been guilty of chasing political

or economic power. As a result, the

church has been viewed as intolerant

and dogmatic, whilst the reputation

of the New Age movement has

remained relatively unsullied.

A recurring theme of the book is

that there remains a strong spiritual

hunger in the West today, which

serves as an encouragement to

those hoping to share their faith

with others. Why Jesus? is for those

who want to communicate more

eff ectively to those from a New Age

background or those seeking to

understand more about the beliefs

that underpin the movement. Above

all, it serves as a reminder that

the need for apologetics training

has arguably never been greater,

which is why Zacharias’ ministry is

dedicated to ‘helping the thinker

believe, and the believer think’.

Copies of Why Jesus? are available

for £12 each from the Oxford offi ce.

R EVIEW BY SIMON WENHAM

Have you ever heard someone say ‘I’m not religious, but I am a spiritual person’?

SUMMER 2012 | PULSE ISSUE 11

EVANGELISM

IN THE

PUBLIC SPHERE

In the last few months God has featured prominently in the news. Th ere has been the question of whether councils can include a time of

prayer in their meetings, there have been statements about religion from the highest echelons of the royal family, and the government recently

held a discussion about the role of Christianity in Britain today.

BY AMY ORR-EWING

SUMMER 2012 | PULSE ISSUE 11

The Archbishop of Canterbury’s

debate with Professor Richard

Dawkins in Oxford on God’s

existence captured the twittersphere

as Dawkins was quoted as being

agnostic about belief in God.

It seems it is now acceptable to

discuss the Christian faith and belief

in God in public. From radio studios

to the school gate I have enjoyed

being a part of this. The role of

God in Britain is being discussed

up and down the country in

government, education, legislation

and community life in a way that I

can’t remember in recent history.

This is a huge opportunity.

The secularists tell us that nothing

good comes from religion, but isn’t

it actually the case that it is our

Christian heritage that provides

us with a free and open society –

encouraging people to question and

reason for themselves? For many

people religious faith is a process,

a journey of discovery on the basis

of evidence, reason and personal

experience. Christianity has provided

the foundation in Britain for an open

and tolerant society. It was the great

Christian leader Augustine who

coined the phrase tolerare malus.

He claimed that political structure,

infl uenced by the Christian faith,

must tolerate that which it disagreed

with and perceived as wrong, for

the greater good of freedom.

Attitudes about freedom and

tolerance arise from a worldview – a

set of values and beliefs that are

conducive to liberty, which do not

come about by random chance. In

Britain this foundation (or worldview)

has undeniably been the Christian

faith. But this seems to fl y in the

face of the claims made by leading

atheists that belief in God is delusional

and oppressive and that people in

Britain are not truly religious anyway.

Invoking what has come to be known

by sociologists as the secularization

thesis, they tell us that modern

countries eventually turn their

back on spiritual belief - as people

progress they become less religious.

However, the myth of secularization

has plainly not panned out and it

has been soundly debunked within

academia. The leading sociologist

Mary Douglas announced the death

of the secularization theory in 1982

in an essay that began with the

words, ‘Events have taken religious

studies by surprise.’ Even prominent

proponents like sociologist Peter

Berger have now abandoned

it because the world is plainly

becoming more religious not less.

SO IS BRITAIN STILL A CHRISTIAN COUNTRY?

Our most profound laws and rights,

and the concept of the dignity of the

human person expounded in the

Magna Carta arise from a Christian

vision and the assumption of God’s

existence. Our greatest social reform

movements, from the abolition of

the slave trade to the reform of child

labour laws - and many other justice

movements - are the bequest of this

heritage. Britain has benefi tted so

much from Christianity – and this

continues today, as we see the values

of a tolerant society envisaged by St

Augustine where Rowan Williams and

Richard Dawkins can debate without

fear of reprisals. Does everyone in

Britain agree with the central tenets

of the Christian faith? No, of course

not, but does our Christian heritage

make a way for peace, courteous

debate, tolerance, inclusion and

freedom? I believe it does.

But as Christians going about our

everyday lives, are we able to speak

confi dently and warmly about the

person of Christ who has inspired

so much that is good about our

society? Or are we silenced by

a fear of seeming intellectually

unsophisticated? Last month, I was

privileged to be leading a university

mission in the north of England.

It was freezing cold and we were

holding a series of events for students

in a marquee in the snow. This

particular university is known for

its nightlife and on the surface it

seemed, under the circumstances,

to be a very unlikely place for

people to be turning to Christ in

any signifi cant number. My team

and I were so humbled to see over

forty students make professions of

faith in Christ for the fi rst time and

139 signed up asking to fi nd out

more about the Christian faith.

As people up and down the country

discuss belief in God and the

newspapers keep running stories

about Christianity, we are seeing a

greater openness to speak about

the gospel in Britain. Who knows,

this may be a window that is open

for a few weeks or months, or it

may be a more signifi cant change.

Either way, are we ready and willing

to take the opportunities to speak

of Christ when they come?

Amy Orr-Ewing

UK DIRECTOR

DOES OUR CHRISTIAN

HERITAGE MAKE A WAY FOR PEACE,

COURTEOUS DEBATE, TOLERANCE,

INCLUSION AND FREEDOM?

9IL

LU

ST

RA

TIO

N B

Y K

AR

EN

SA

WR

EY

SUMMER 2012 | PULSE ISSUE 11

I have spent my life as a pure

mathematician and I often refl ect

on what physics Nobel Prize-

winner Eugene Wigner called

‘the unreasonable eff ectiveness

of mathematics’. How is it that

equations created in the head of

a mathematician can relate to the

universe outside that head? This

question prompted Albert Einstein

to say: ‘The only incomprehensible

thing about the universe is that it

is comprehensible.’ The very fact

that we believe that science can be

done is a thing to be wondered at.

Why should we believe that

the universe is intelligible?

After all, if as certain secular thinkers

tell us, the human mind is nothing

but the brain and the brain is nothing

but a product of mindless unguided

forces, it is hard to see that any kind

of truth, let alone scientifi c truth,

could be one of its products. As

chemist J. B. S. Haldane pointed

out long ago: if the thoughts in my

mind are just the motions of atoms

in my brain, why should I believe

anything it tells me – including

the fact that it is made of atoms?

Yet many scientists have adopted

that naturalistic view, seemingly

unaware that it undermines the

very rationality upon which their

scientifi c research depends!

Contemporary science is a wonderfully collaborative activity. It knows no barriers of geography, race or creed.

At its best it enables us to wrestle with the problems that beset humanity and we rightly celebrate when an

advance is made that brings relief to millions.

JOHN LENNOX’S

LENT TALK FOR RADIO 4

SUMMER 2012 | PULSE ISSUE 11

It was not – and is not – always so.

Science, as we know it, exploded onto

the world stage in Europe in the 16th

and 17th centuries. Why then and why

there? Alfred North Whitehead’s view,

as summarised by C. S. Lewis, was

that: ‘Men became scientifi c because

they expected law in nature, and they

expected law in nature because they

believed in a lawgiver’. It is no accident

that Galileo, Kepler, Newton and

Clerk-Maxwell were believers in God.

Melvin Calvin, Nobel Prize-winner

in biochemistry, fi nds the origin of

the conviction, basic to science, that

nature is ordered in the idea ‘that

the universe is governed by a single

God, and is not the product of the

whims of many gods, each governing

his own province according to

his own laws. This monotheistic

view seems to be the historical

foundation for modern science.’

Far from belief in God hindering

science, it was the motor that drove

it. Isaac Newton, when he discovered

the law of gravitation, did not make

the common mistake of saying: ‘now

I have a law of gravity, I don’t need

God’. Instead, he wrote Principia

Mathematica, the most famous book

in the history of science, expressing

the hope that it would persuade the

thinking man to believe in a Creator.

Newton could see what, sadly, many

people nowadays seem unable to

see, that God and science are not

alternative explanations. God is the

agent who designed and upholds the

universe; science tells us about how

the universe works and about the

laws that govern its behaviour. God

no more confl icts with science as an

explanation for the universe than Sir

Frank Whittle confl icts with the laws

and mechanisms of jet propulsion as

an explanation for the jet engine. The

existence of mechanisms and laws

is not an argument for the absence

of an agent who set those laws and

mechanisms in place. On the contrary,

their very sophistication, down to

the fi ne-tuning of the universe, is

evidence for the Creator’s genius.

For Kepler: ‘The chief aim of all

investigations of the external world

should be to discover the rational

order which has been imposed on

it by God and which he revealed to

us in the language of mathematics’.

As a scientist then, I am not ashamed

or embarrassed to be a Christian.

After all, Christianity played a large

part in giving me my subject.

The mention of Kepler brings me

to another issue. Science is, as I said

earlier, by and large a collaborative

activity. Yet real breakthrough is often

made by a lone individual who has

the courage to question established

wisdom and strike out on his own.

Kepler was one such. He went to

Prague as assistant to the astronomer

Tycho Brahe, who gave him the task

of making mathematical sense of

observations of planetary motion, in

terms of complex systems of circles.

The view that perfect motion was

circular came from Aristotle

and had dominated thought for

centuries. But Kepler just couldn’t

make circles fi t the observations.

He then decided on the revolutionary

step of abandoning Aristotle,

approaching the observations of

the planets from scratch and seeing

what the orbits actually looked

like. Kepler’s discovery, that the

planetary orbits were not circular

but elliptical, led to a fundamental

paradigm shift in science.

Kepler had the instinct to pay careful

attention to things that didn’t fi t in

to established theory. Einstein was

another. For things that don’t fi t

in can lead to crucial advances in

scientifi c understanding. Furthermore,

there are things that do not fi t in to

science. For, and it needs to be said

in the face of widespread popular

opinion to the contrary, science is

not the only way to truth. Indeed,

the very success of science is due to

the narrowness of the range of its

questions and methodology. Nor is

science co-extensive with rationality –

otherwise half our university faculties

would have to shut. There are bigger

matters in life – questions of history

and art, culture and music, meaning

and truth, beauty and love, morality

and spirituality and a host of other

important things that go beyond the

reach of the natural sciences – and,

indeed, of naturalism itself. Just as

Kepler was initially held back by an

assumed Aristotelianism could it

not be that an a priori naturalism is

holding back progress by stopping

evidence speaking for itself?

It is to such things that my mind turns

at this time of Lent. In particular, to

the person of Jesus, the man, above

all others, who did not fi t in to the

pre-conceptions of this world. Just

as Kepler revolutionized science by

paying close attention to why the

observations of the planets did not fi t

in to the mathematical wisdom of the

time, I claim that my life and that of

many others has been revolutionized

by paying close attention to why

Jesus did not, and still does not, fi t in

to the thinking of this world. Indeed,

the fact that Jesus did not fi t in is

one of the reasons I am convinced

of his claim to be the Son of God.

For instance, Jesus does not fi t in to

the category of literary fi ction. If he

did, then what we have in the Gospels

is inexplicable. It would have required

exceptional genius to have invented

the character of Jesus, and put into his

mouth parables that are in themselves

literary masterpieces. It is just not

credible that all four Gospel writers

with little formal education between

IT IS NO ACCIDENT THAT GALILEO, KEPLER, NEWTON AND

CLERK-MAXWELL WERE BELIEVERS IN GOD.

SUMMER 2012 | PULSE ISSUE 11

them just happened, simultaneously,

to be literary geniuses of world rank.

Furthermore, there are relatively few

characters in literature that strike us

as real persons, whom we can know

and recognise. One of them is my

intellectual hero, Socrates. He has

struck generation after generation of

readers as a real person. The reason

for that is that Plato did not invent

him. So it is with Jesus Christ. Indeed,

the more we know about the leading

cultures of the time, the more we

see that, if the character of Jesus had

not been a historical reality, no-one

could have invented it, for the simple

reason that he did not fi t in to any

of those cultures. The Jesus of the

Gospels fi tted nobody’s concept of a

hero. Greek, Roman and Jew all found

Him the very opposite of their ideal.

The Jewish ideal was that of a strong,

military general, fi red with messianic

ideals, and prepared to fi ght the

Roman occupation. So when Jesus

eventually off ered no resistance to

arrest, it was not surprising that his

followers temporarily left him. He

was far from the Jewish ideal leader.

As for the Greeks, some favoured

the Epicurean avoidance of

extremes of pain and pleasure

that could disturb tranquility.

Others preferred the rationality of

Stoicism that suppressed emotion

and met suff ering and death with

equanimity, as Socrates had done.

Jesus was utterly diff erent. In

such intense agony in the garden

of Gethsemane that he sweat

drops of blood, he asked God

to let Him off the task of facing

the cross. No Greek would have

invented such a fi gure as a hero.

And the Roman Governor Pilate found

Christ unworldly and impractical

when Jesus said to him: ‘My kingdom

is not of this world…to this end I was

born and to this end I came into the

world to bear witness to the truth’.

So, Jesus ran counter to everybody’s

concept of an ideal hero. Indeed,

Matthew Parris, an atheist, suggested

in the Spectator recently that if

Jesus hadn’t existed not even

the church could have invented

him! Jesus just did not fi t in.

Nor did his message – the Easter

message for which Lent prepares us.

St. Paul tells us that the preaching of

the cross of Christ was regarded by

the Jews as scandalous, and by the

Greeks as foolish. The early Christians

certainly could not have invented

such a story. Where, then, did it come

from? From Jesus himself who said:

‘the Son of Man did not come to be

served, but to serve, and to give his life

as a ransom for many’. Jesus did not

fi t in to the world. So they crucifi ed

him and tried to fi t him in a tomb.

But that did not work either. He rose

from the dead on the third day.

But, doesn’t this go against

the grain of the science I was

praising earlier? Aren’t such

miracles impossible because they

violate the laws of nature?

I disagree. If, on each of two nights,

I put 10 pounds into my drawer, the

laws of arithmetic tell me I have 20

pounds. If, however, on waking up,

I fi nd only 5 pounds in the drawer,

as C. S. Lewis pointed out, I don’t

conclude that the laws of arithmetic

have been broken, but possibly the

laws of England. The laws of nature

describe to us the regularities on

which the universe normally runs.

God who created the universe with

those laws is no more their prisoner

than the thief is prisoner of the laws

of arithmetic. Like my room, the

universe is not a closed system, as

the secularist maintains. God can,

if he wills, do something special,

like raise Jesus from the dead.

Note, that it is my knowledge of

the laws of arithmetic that tells me

that a thief has stolen the money.

Similarly, if we did not know the law

of nature that dead people normally

remain in their tombs, we should

never recognise a resurrection. We

could certainly say that it is a law

of nature that no-one rises from

the dead by natural processes. But

Christians do not claim that Jesus

rose by natural processes, but by

supernatural power. The laws of

nature cannot rule out that possibility.

Hume’s view was that you must

reject a miracle as false, unless

believing in its falsity would have

such inexplicable implications, that

you would need an even bigger

miracle to explain them. That is

one good reason to believe in the

resurrection of Jesus. The evidence

of the empty tomb, the character

of the witnesses, the explosion of

Christianity out of Judaism and

the testimony of millions today are

inexplicable without the resurrection.

As Holmes said to Watson: ‘How

often have I said to you that when

you have eliminated the impossible,

whatever remains, however

improbable, must be the truth?’

As Russian Christians say at Easter:

Khristos Voskryes – Voiistinu Voskryes!

Christ is risen – he is risen indeed!

John Lennox

ADJUNCT PROFESSOR AT THE OCCA

SUMMER 2012 | PULSE ISSUE 11

"At fi rst sight, the biblical view of truth is obscene to modern minds. But on a deeper level, the biblical view is profound, timely, and urgent for today, even for those who reject it."

WHY DOESTRUTH

MATTER?

BY OS GUINNESS

In this extraordinary moment in

human history, why is it that truth

matters? There are times when history

and the gospel of Jesus converge

and create a great thrust forward

in human history. So it was with

the ‘gifts’ of the gospel, such as the

rise of philanthropy, of the reform

movements, or the creation of the

universities, or modern science.

There are other times when history

and the gospel collide and the

titanic struggle shapes history in a

diff erent, but equally decisive, way.

So it was when the Lordship of Christ

triumphed over the might of imperial

Rome. But there are still other times

when history and the gospel appear

to collide but, in fact, the gospel

speaks to the deepest dilemmas and

the highest aspirations of the age,

even to those who oppose it. So it

is today with the concept of truth.

At fi rst sight, the biblical view of truth

is obscene to modern minds. It’s

arrogant, it’s exclusive, it’s intolerant,

it’s divisive, it’s judgmental, and it’s

reactionary. But on a deeper level,

the biblical view is profound, timely,

and urgent for today, even for those

who reject it. But obviously regardless

of what the world thinks, we follow

the one who is the way, the truth,

and the life. We therefore worship

and serve the God of truth, whose

Word is truth, and who Himself is

true and may be trusted because

of his covenant faithfulness.

Let me, therefore, sum up six

reasons why truth matters to

us supremely. And why those

Christians who are careless about

truth are as wrong, and as foolish,

and as dangerous as the worst

scoff ers and sceptics of our time.

FIRST, ONLY A HIGH VIEW OF TRUTH HONOURS THE GOD OF TRUTH.

Too often truth is left as a

philosophical issue. Philosophical

issues are important to us but truth

is fi rst and foremost a matter of

theology. Not only is our Lord the

God who is objectively, really, and

truly there—so that what we believe

corresponds to what actually is

the case —but our Lord is also the

true one in the sense that He is the

one whose covenant loyalty may

be trusted and the entire weight

of our existence staked on Him.

Those who weaken their hold on

truth, weaken their hold on God.

SECOND, ONLY A HIGH VIEW OF TRUTH REFLECTS HOW WE COME TO KNOW AND LOVE GOD.

Jesus is the only way to God, although

there are as many ways to Jesus as

there are people that come. But the

record of Scripture and the experience

of the centuries show us that there are

three main reasons why we believe,

often overlapping. We come to faith

in Christ because we are driven by

our human needs. We come to faith

in Him because He seeks us and fi nds

us. And we come to faith in Christ

because we believe his claims and

the claims of the gospel are true. It is

because of truth that our faith in God

is not irrational. It is not an emotional

crutch. It is not a psychological

projection. It is not a matter of wish-

fulfi lment. It is not an opiate for

the masses. Our faith goes beyond

reason because we as humans are

much more than reason. But our

faith is a warranted faith because

we have a fi rm, clear conviction that

it is true. We are those who think in

believing and we believe in thinking.

THIRD, ONLY A HIGH VIEW OF TRUTH EMPOWERS OUR BEST HUMAN ENTERPRISES.

Sceptics and relativists who

undermine the notion of truth

are like the fool who is cutting off

the branch on which he is sitting.

Without truth, science and all human

knowledge collapse into conjecture.

Without truth, the vital profession of

journalism and how we follow the

events of our day and understand

the signs of our times dissolve into

rumour. Without truth, the worlds

of politics and business melt down

into rules and power games. Without

truth, the precious gift of human

reason and freedom becomes license,

and all human relationships lose

IN THIS EXTRAORDINARY

MOMENT IN HUMAN HISTORY,

WHY IS IT THAT

TRUTH MATTERS?

SUMMER 2012 | PULSE ISSUE 11

SUMMER 2012 | PULSE ISSUE 11

the bonding element of trust that is

binding at their heart. We then, as

followers of Christ, are unashamed

to stand before the world as servants

and guardians of a high view of truth,

both for our Lord’s sake but also for

the highest endeavours of humanity.

FOURTH, ONLY A HIGH VIEW OF TRUTH CAN UNDERGIRD OUR PROCLAMATION AND DEFENSE OF THE FAITH.

If our Lord is the God of truth, we

gladly affi rm that all truth is God’s

truth and we therefore welcome all

ideas and arguments and beliefs that

pass the muster of God’s standard

of truth. But we also know that all

humans, including we ourselves,

are not only truth seekers but truth

twisters. All unbelief, as St. Paul says,

holds the truth in unrighteousness.

We have the grounds, as well as the

duty, to confront false ideas and false

beliefs with the assurance that they

are neither true in the end nor are

they in the best interests of those who

believe them. And we must never

forget today that our stand for truth

must start in the church itself. We

must resist the powerful seductions

of those who downplay truth for

methodology, or truth in the name of

activism, or truth for entertainment, or

truth for seeker sensitivity, and, above

all, those who put a modern and

revisionist view of truth in the place of

the biblical view. Whatever the motive

of these people, all such seductions

lead to a weak and a compromised

faith and they end in sorrow and

a betrayal of our Lord. To abandon

truth is to abandon faithfulness, and

to commit theological adultery, and

to end in spiritual suicide. Let the

sorry fate of Protestant liberalism

be a stern warning to us all.

FIFTH, ONLY A HIGH VIEW OF TRUTH IS SUFFICIENT FOR COMBATING EVIL AND HYPOCRISY.

Postmodern thinking makes us all

aware of hypocrisy but gives us no

standard of truth to expose and

correct it. And now with the global

expansion of markets through

capitalism, the global expansion of

freedom through technology and

travel, and the global expansion of

human dysfunctions through the

breakdown of the family, we are

facing the greatest human rights crisis

of all time and a perfect storm of evil.

Both hypocrisy and evil depend on

lies. Hypocrisy is a lie in deeds rather

than in words. And evil always uses

lies to cover its oppressions. Only with

truth can we stand up to deception

and manipulation. For all who hate

hypocrisy, care for justice and human

dignity, and are prepared to fi ght evil,

truth is the absolute requirement.

SIXTH AND LASTLY, ONLY A HIGH VIEW OF TRUTH WILL HELP OUR GROWTH AND OUR TRANSFORMATION IN CHRIST.

Just as Abraham was called to walk

before the Lord, so are we called

to follow the way of Jesus. Not just

to believe the truth or to know

and defend the truth, but to so

live in truth that truth may be part

of our innermost beings, that in

some imperfect way we become

people of truth. So let there be no

uncertainty from this congress, as

followers of Christ and as evangelicals.

If we do not stand for truth, this

congress might as well stop here.

Shame on those Western Christians

who casually neglect or scornfully

deny what our Lord declared, what

the Scriptures defend, and what

many brothers and sisters would

rather die than deny: that Jesus is

the way, the truth, and the life.

Let us say with the great German

reformer, as he said of truth in regard

to the evil one, ‘One little word

will fell him.’ Let us demonstrate

with our brother the great Russian

novelist and dissident, ‘One word of truth outweighs the entire world.’ If faith is not true, it would be false

even if the whole world believed

it. If our faith is true, it would be

true even if the whole world were

against it. So let the conviction

ring out from this conference. We

worship and serve the God of truth

and humbly and resolutely, we

seek to live as people of truth. Here

we still stand, so help us God.

As evangelicals we are people of the

good news, but may we also always

be people of truth, worthy of the

God of truth. God is true. God can be

trusted in all situations. Have faith in

God. Have no fear. Hold fast to truth.

And may God be with us all.

Os Guinness

SENIOR FELLOW AT THE OCCA

From a plenary session delivered

at Lausanne 2010 (www.lausanne.org)

Used by permission of the author.

SUMMER 2012 | PULSE ISSUE 11

I was more of an enthusiast than an

expert, but the ‘gather-round’ moment

was crucial - a constructive breathing

space to reassess the successes and

failures of the fi rst half and then to get

back into the game and play to win.

I have another set of memories - weak

tea in polystyrene cups in my student

days enduring an earnestly-led bible

study strung out like a painful English

comprehension exercise: …'and what

does Jesus mean when he said "come

follow me and I will make you fi shers

of men"?'...'That he wanted evangelists

to always exaggerate the size of

the catch?' 'Er… no - that wasn’t

quite the answer I was looking for!'

Discipleship, so central, so crucial

to genuine Christianity has been

blighted by the memories of tepid

tea and navel-gazing on one hand,

or by guilt-inducing exhortation and

dry cerebral information-sharing

on the other. Some children of the

eighties may still be living with the

psychological hang-over of the heavy

shepherding movement, though

increasing numbers of young adults

are now asking and longing for

more mentoring, more constructive

spiritual intervention. Pastoral care

in church communities has taken

on the trappings of the client-

provider relationships, so beloved

of public sector bodies - individuals

involved in public ministry teams

are often hindered or swamped by

the management structures which

were meant to liberate them.

Huddles are the half-time team

talks of the Christian walk - but

probably without oranges.

They are a re-articulation of a long-

I have an enduring memory of half-time team-talks as a boy playing rugby: It is the quarters of oranges sucked enthusiastically and turned into garish clown smiles combined with the obligatory

‘C’mon lads’ and a little pep talk from the team captain.

DISCIPLESHIP

REMIXED:

BY FROG ORR-EWING

The Art and Practiseof Huddling

SUMMER 2012 | PULSE ISSUE 11

17understood principle of Christian

discipleship, from the catechisms of

the early church, to the class groups

of the early Methodists, marked by

content, accountability, prayer and,

more than anything, an expectation

of spiritual progress in the lives of

those within the group. They are

intentional discipleship groups

formed at the invitation of the leader,

which meet regularly. They are

prayerful and accountable groups

which practice learning together

through theological refl ection and

asking penetrating, but open-ended,

questions. They are designed to

equip and empower missionary

leaders and discipleship is expected

to be a process and a journey which

includes regular change. We come

to speak and we come to listen. We

come to draw upon the lessons of

life and ministry, as well as think

of ways through problems.

Listen to how radically diff erent a

huddle leader’s briefi ng sounds

to a classic small group:

Ask the person/people who talked about that topic to unpack further what they have said. Ask them questions that help bring accurate observation – essentially these are ‘who’, ‘where’, ‘when’, ‘what’ and ‘how’ questions. Th en begin to do some refl ection together – essentially by asking ‘why’ questions. Ask them what refl ections they have had on the matter. Follow up with questions that ensure they are refl ecting properly – for instance, ‘Why did you say that? Why does it stir that response in you? What could you have done better? What are you pleased about in your response? Why is there such a strong emotional response in you to this person? Is God showing you any broader

patterns in this incident?’... Th e discussion will fl ow out of the refl ection stage, and your aim in it is to be well on the way to identifying the key issue at hand – in other words, ‘What is God saying in this situation?’1

Over the last two years, we have

incorporated huddles into the

spiritual formation of the year-long

programme at the OCCA, with tutors

and some of the itinerant team

leading the process for the students.

As tutors we have been astonished

at how much more progress we

are seeing in the spiritual lives of

our students since we began to

expand on a simple pastoral or prayer

group of previous years. We ask

about the placements, the missions,

we process culture-shock and

homesickness – emotional, as well

as practical, issues are allowed. The

groups are safer and bolder at the

same time. We have even continued

with some ‘virtual huddles’ using

Skype for OCCA alumni scattered

across the world, serving God.

We have tended to rest most heavily

on one model to work through

the hour we spend together every

week - which is that of a ‘learning

circle’. Those accustomed to the

academic discipline of theological

refl ection, might have encountered

such tools within spiritual direction

and spiritual counselling, but seldom

have these lessons been brought

out of the Academy or the confi nes

of the professionals involved in

mental or vocational health.

We take a moment out of our lives

and pause to observe, refl ect and

discuss, before beginning to consider

a way forward. We plan, account

and then act - getting back into

the game again for the second half.

Having repented, and turned away,

ideally from those destructive habits

or thoughts in order to embrace

the positive values and belief in

the Kingdom of God in our current

situations and circumstances. After

the fi rst few times together these

precise steps begin to give way to a

fl ow of thought and accountability

which by God’s grace eff ects

change in the life of a disciple.

(THIS IMAGE IS FROM

‘BUILDING A DISCIPLING CULTURE’ - SEE BELOW)

More recent resources developed

by 3DM have refi ned these

theoretical models into a truly

helpful discipleship tool, which I am

convinced is here to stay, because

it has recaptured an understanding

of discipleship more like a biblical

apprenticeship than being in the

schoolroom. The disciples needed

not only to ‘follow Jesus’, as a prayer

of commitment, but while they did

so, they would begin the process of

change from fi shers of fi sh to eff ective

persuaders, who help people out

of the choppy sea of confusion into

the Ark of salvation. This change in

purpose would require not just a

diff erent Master to follow, but also a

change in character, a renewal of the

mind, and a re-skilling for mission.

I have taken part in huddles for several

years now, as well as having led

them, and have never even thought

to pick holes in a polystyrene cup

out of boredom or in a desperate

attempt to avoid the creeping

death of an English comprehension

question. Discipleship has become

fun again and eff ective. Hurrah!

Frog Orr-Ewing

CHAPLAIN OF THE OXFORD CENTRE FOR CHRISTIAN APOLOGETICS

1 Mike Breen, How to Lead a Huddle, p.40

Excellent resources to help explain huddles and missional communities can be found on the 3DM website, but I would

recommend a cover-to-cover read of two specifi c books for an overview:

Building a Discipling Culture by Mike Breen and Steve Cockram and Launching Missional Communities by Mike Breen and Alex Absolom

X

�R

epen

t�

Act

Account

Plan

�B

elie

ve�

�

Observe

Reflect

Discuss

SUMMER 2012 | PULSE ISSUE 11

From a picture book, read to a child,

to the most ambitious novel up

for the Nobel Prize for Literature,

authors say something about the

reality in which we live - even when

they claim they don’t. The reason

is that they can’t help it. A story is

seldom told without the narrative,

somehow, growing out of the way

the author themselves makes sense

of the world - their worldview. As

Paulo Coelho writes, ‘I am my books

and they are part of my soul.’

Writers may choose to represent

diff erent worldviews through diff erent

characters in their stories, but it is

rare for the resolution of a story to

Everybody loves a good story. It is hard, to conceive of a story that doesn’t also carry a message, whether in novels, movies,

TV programmes, songs or poetry. We are surrounded by narrative and, as human beings, it has always been so.

BY THEO BRUN

SUMMER 2012 | PULSE ISSUE 11

run against the author’s deepest

convictions about what is true.

Can anyone doubt the sincerity of

J.K. Rowling’s climactic conclusion

to the Harry Potter series – that she

believes it is only sacrifi cial love

that has the power to overcome

death and evil? That tendency arises

because authors use narrative to get

at the truth – often to discover it for

themselves within their own stories.

Even if the plotline is outrageous

or fantastical or mythical, essential

messages about good and evil,

purpose, fate and freedom, love

and suff ering are inescapable when

you tell a story about anything. As

readers, we allow ourselves to be

drawn along by the story if we fi nd

it compelling or resonant; or we

end up parting company with the

storyteller somewhere along the

way, as our views of reality diverge.

Narrative, however, is not only

something we draw into ourselves

from storytellers in their various

guises; it is how we make sense of

our own lives. From the creation of

all things and how we came to be,

to the plans we’ve made for this

week or year and why, narrative

informs our vision for our lives and

the life of the world: our grasp of

truth. Who creates the narrative of

our age? What are they saying?

Although authors with a Christian

worldview have great champions

amongst their number - writers

like Lewis and Tolkien; Dickens

and Dostoyevsky; Tolstoy and

Sayers - has some ground been lost

recently? Popular fi ction these days

rarely arises from overtly Christian

imaginations. Perhaps because,

on one hand, preachy books

generally don’t make good fi ction;

on the other, books that are well

received tend to refl ect the existing

worldview of the reading public.

Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials,

refl ects an acerbic scepticism about

the Church. Jonathan Franzen’s

bestsellers refl ect a view that

psychology explains all, while saying

almost nothing positive about faith.

The popularity of Paulo Coelho

refl ects his intoxicating way of telling

a story, but also a palatable form of

spirituality which tries to be many

things to many people. On the broad

road of Coelho’s spirituality in The

Witch of Portobello, one can wander

rather freely from Catholicism to

Buddhism; to pagan rites and ancient

Mother Goddess worship; without

discounting any. Jesus is good, but

whoever says so exclusively is bad

(and misunderstands Him). It is as if

Coelho celebrates Jesus as life-giving

water, but stops short of actually

encouraging anyone to take a drink.

Even more popular, is the world of

Harry Potter, created by J. K. Rowling.

It is a grand assertion of the reality

of good and evil, a premise people

naturally accept, from which great

minds through history have argued

for the existence of God. Though

she admits to the Christian themes

in her books, if she laboured the

point too much would she begin

to lose her audience? In young

adult fi ction, a publishing friend

assures me that vampires are now

‘dead’ and adventures in dystopian

near-future worlds, like The Hunger

Games trilogy, are taking over. What

spiritual messages are behind that

kind of fi ction? What is the eff ect

of absorbing those kinds of stories

at such an impressionable age?

There are no clear answers to those

questions. What is clear is that fi ction

is a realm of the heart and the mind –

the imagination – where the destiny

of a person’s soul may be profoundly

infl uenced. Jesus knew that better

than anyone: his teaching of eternal

truths often came through stories.

If you like, he used fi ction to make

his point, and by using parables,

he introduced a veil of judgment

between the message and his

listeners. How would each receive his

stories? ‘He who has ears, let him hear.’

To imitate Jesus, followers must,

therefore, contest the realm of fi ction.

That is where fi ction and apologetics

join hands. In the search for truth,

apologetics serves a vital purpose.

Reason has the power to remove

many obstacles standing in the

way of a person coming to faith.

Fiction, on the other hand, exists as

a paradox; as Camus said, ‘Fiction

is the lie through which we tell

the truth.’ Crucially, it is often those

truths that touch the heart.

For us then, discernment is key.

When the ears of a post-modern

listener may be closed to the

propositional truths of philosophy

or reason - that this is right, and that

is wrong - they may yet be open to

the power of story. Such a person,

trying to make sense of their own life,

may be unable to admit that they

are wrong or that there is just one

Truth in Christ, but they may be able

to accept an ‘apologetic of story’.

That God may become part of

their narrative, and they may

become part of His.

Theo Brun

OCCA ALUMNUS

For further information about courses

at the OCCA see the back cover.

USING STORIES FOR EVANGELISM

Do you know of good stories that can

be used in an evangelistic context? An

ex-student of the OCCA has contacted

us to ask whether we knew of any tales

that could be used to communicate

both the gospel and a Christian ethic

to street children, but without overtly

mentioning fi gures from the Bible,

etc. These are to be used in a country

where Christianity is marginalised

and therefore the stories have to be

appropriate for this setting. If you know

of anything that might be suitable

please email [email protected].

SUMMER 2012 | PULSE ISSUE 11

Rather than suggesting ‘religion

poisons everything,’ he argues

that it is ‘intermittently too useful,

eff ective and intelligent to be

abandoned to the religious alone.’1

De Botton’s central thesis is that the

best ideas and practices (i.e. those that

don’t relate to belief in God) should

be stolen and appropriated by non-

believers. He suggests that atheists

can learn from religious approaches

to community, kindness, education,

tenderness, pessimism, perspective,

art, architecture and institutions

(each of which are covered in a

respective chapter). Although he

cherry-picks from a variety of faiths,

the majority of what he commends

comes from Christianity. He

applauds the church for, amongst

other things, teaching us how to

live, encouraging people towards

moral improvement, promoting

role models, being consoling and its

eff ectiveness in communicating ideas.

One might argue that there is

nothing particularly revolutionary

about that approach. Charlie Brooker,

for example, rather unkindly branded

de Botton a ‘pop philosopher’ who

has ‘forged a lucrative career stating

the bleeding obvious’.2 The book

Christians have grown accustomed to the aggressive anti-religious rhetoric that has become a hallmark of the New Atheists, so it comes as

quite a surprise, therefore, to read Alain de Botton’s, Religion for Atheists, which adopts a much more conciliatory approach to the topic of faith.

R EVIEW BY SIMON WENHAM

SUMMER 2012 | PULSE ISSUE 11

21is certainly targeted at a popular

audience - and it suff ers from various

classic weaknesses as a result, such as

a lack of precise defi nitions (‘religion’

and ‘culture’ being two obvious

ones), some broad generalisations

and inconsistent citation - but

this shouldn’t detract from the

fact that his work sells because it

resonates with so many people.

Indeed, Religion for Atheists is

intended to be a practical guide for

improving life, because de Botton

believes that western society has

lost out because it has ‘secularized

badly’.3 In particular, he notes that

atheism has failed to satisfy deep

human needs, which remain the

primary focus (and preserve) of

religions. Furthermore, he suggests

that some of the atheist literature

that has been generated has not

been particularly helpful – in a recent

radio interview, for example, he

described A. C. Grayling’s attempt at

humanist wisdom as a ‘weird book’.4

One should not assume, however,

that this is a pro-Christian work, as

he is quite clear that it is intended for

those who are already non-believers,

but who want to know where to go

next (Atheism 2.0, as he has dubbed

it). The non-existence of God is

therefore assumed throughout and

is backed up by various passing

comments.5 Intriguingly, the reason

for not addressing this topic is that

he believes that people come to

faith by a ‘fairly mysterious’ process,

which may not be related to rational

thought, but, instead, to some kind of

psychological-spiritual orientation.6

The idea provokes a number of

questions, although it is a topic

that is not covered in his book.

De Botton was fully aware that

his book would upset the militant

atheist and the believer alike.7 The

major criticism he faced from the

former, was that, like his inspiration

Auguste Comte, the project comes

across as being a little too religious

(as the name of the book suggests).

He advocates, for example, having

patron saints of atheism, secular

‘wailing walls’ transmitted by

technology to help us cope with

our inadequacies, and ‘temples’ for

atheists (in the form of museums that

inspire us). One of his most amusing

suggestions is that non-believers

should imitate American Pentecostal

churches by adopting a more

interactive approach to learning,

by saying the secular equivalent of

‘Amen, Preacher’ during lectures!8

Richard Dawkins poured scorn on

the idea of ‘temples for atheists’, as

he suggested that the money would

be better spent on something more

practical, such as institutions for

educating people to think logically

and critically.9 De Botton responded

by saying that although you had ‘to

love Dawkins for his sheer grumpiness,’

the backlash had illustrated precisely

why he thought his book was

necessary. Although he accepted the

word ‘temple’ was perhaps misguided,

he pointed out that whilst schools,

libraries and railways stations are all

very valuable, they are not enough to

satisfy the inner human longings.10

Yet the atheist John Gray argued

that de Botton’s ideas were doomed

to failure, because they were,

by defi nition, unable to satisfy

the most important needs:

Th e church of humanity is a prototypical modern example of atheism turned into a cult of

collective self-worship... Religions are human creations. When they are consciously designed to be useful, they are normally short-lived. Th e ones that survive are those that have evolved to serve enduring human needs - especially the need for self-transcendence. Th at is why we can be sure the world's traditional religions will be alive and well when evangelical atheism is dead and long forgotten.11

By contrast, criticism from religious

quarters centred on the problem of

trying to defend ideas or practises,

whilst denying the philosophical

justifi cation for upholding them.

A LOT OF CHRISTIAN CONCEPTS ARE FLOATING IN OUR

SOCIETY UNRECOGNISED AND UNNAMED.

SUMMER 2012 | PULSE ISSUE 11

22

1 A. de Botton, Religion for Atheists

(London, 20012), p. 312.

2 C. Brooke, ‘The Art of Drivel’, The

Guardian , 1 January 2005.

3 De Botton, Religion , p. 17.

4 A. de Botton, J. Orr and J. Brierley, ‘Should

atheists be more religious?’, on ‘Unbelievable?’,

Premier Christian Radio, 11 February 2012.

5 De Botton, Religion , p. 173

6 De Botton, Orr and Brierley, ‘Should atheists’.

7 De Botton, Religion , pp. 17 – 18.

8 De Botton, Religion , pp. 131.

9 ‘Temple for Atheists Provokes row among non-

believers’, Daily Telegraph , 27 January 2012.

10 De Botton, Orr and Brierley, ‘Should atheists’.

11 ‘The Cult of Unbelief’,

New Statesman , 16 February 2012.

12 De Botton, Orr and Brierley, ‘Should atheists’.

13 ‘Divine intervention’, Sydney Morning

Herald , 18 February 2012.

14 ‘Religion for atheists by Alain de Botton

– review’, Guardian , 12 January 2012.

15 ‘Secularism vs Religion: Should we give a fi g?’,

The Big Issue , 27 February – 4 March 2012, p. 9.

16 De Botton, Orr and Brierley, ‘Should atheists’.

17 A. de Botton, Status Anxiety (London,

2004), pp. 225 – 274.

18 De Botton, Religion , p. 77.

19 ‘Religion for Atheists by Alain de Botton –

review’, The Observer , 22 January 2012.

In a recent interview de Botton

defended this approach by saying:

A lot of Christian concepts are fl oating in our society unrecognised and unnamed. Th e very concept of human rights is essentially a Christian concept. Th ings like feminism arise from Christianity, as does the welfare state, in many ways. It’s impossible to imagine a welfare state without the tradition of Christianity and Christian charity, etc… We’ve got a lot of this already and it’s working very well…12

The Religious Editor of The Age ,

Barnie Zwatz, argued that de Botton’s

ideas could be a house built on sand

‘because what gives religions their

staying power are the ideas at their

core. Stripped of that nourishment,

appendages in a secular world

may simply wither and die.’13

The Catholic and Marxist literary critic

Terry Eagleton branded de Botton

a ‘reluctant atheist’, for refusing to

revolutionise his ideas. He suggested

that there is something ‘deeply

disingenuous’ and ‘patronising’ about

arguing ‘that religious beliefs are a

lot of nonsense, but that they remain

indispensable to civilised existence.’

He claimed this was akin to being

told that free speech and civil rights

were bunkum, but that they had

their social uses. By hijacking other

people’s beliefs, emptying them of

content and redeploying them in the

name of moral order, social consensus

and aesthetic pleasure, he argued

that de Botton had reduced the

radical teaching of the gospel to ‘a

set of banal moral tags’ deployed as a

‘soothing form of spiritual therapy.’14

As this suggests, a major problem

with advocating ideas without

the philosophical justifi cation for

supporting them, is that, as well as

being an inconsistent way to live, it

becomes very unclear as to which

ones other people might choose to

adopt. De Botton wants to raise up a

group of benevolent humanists who

can make life better for everyone,

but what if those who take up the

mantel are militant nihilists instead?

The latter might be considered a

danger to society, but if they insist

they are being more consistent

with their worldview, how do you

determine who is right? Furthermore

there are already plenty of secular

‘patron saints’ out there whom people

worship, but many of them are far

from being good role-models. As

Brendan O’Neill, a self-confessed

atheist secularist, has pointed out,

it is becoming increasingly hard

to know which side to take:

A great irony in today’s topsy-turvy faith wars is that the religious side oft en appears more humanist, more trusting of mankind, than the humanist side. Indeed, in a brilliant historical fl ip-reversal of their normal roles, humanists now tend to attack the religious for having too much regard for human beings.15

Furthermore, as James Orr pointed

out, perhaps the greatest irony is

that de Botton’s solution for society

is to become more religious at a

time when many Christians are

advocating precisely the opposite

(in order to avoid a legalistic faith).16

The book will certainly resonate with

those who do not believe in God,

but who identify themselves as

being culturally 'Christian’.

Yet by emphasising the failure of

atheism to meet human needs

and by suggesting the solution is

something akin to a religion, de

Botton has arguably played into the

hands of the religious apologist.

In fact, this is an author who has

written in a previous work that

Christianity is one of the answers to

the ‘status anxiety’ that is so pervasive

in our modern society.17 In Religion

for Atheists , he even writes that ‘Our

deepest wish may be that someone

would come along and save us from

ourselves’!18 The obvious response

to this, from a Christian perspective,

is that someone has already done

this! Furthermore, one might be

inclined to question how eff ective

mimicking religious practices will be.

As Michael Ramsden often says, ‘If you

take Christ out of Christian you are

left with i-a-n and Ian is not going to

help you!’ Indeed, perhaps the fi nal

word should go to Richard Coles, who

points out that our deepest longings

and fears may be ‘mirrored and

contextualised’ by an atheist temple,

but crucially, ‘they are not redeemed’:

…Christianity does not off er consolation, it off ers salvation. Th at is why people built cathedrals, and in other dispensations enormous mosques and complexes of temples: they sought, and seek, salvation, and for this, God-givenness seems to me essential.19

FURTHER READING:

For information about the

inconsistency of holding onto

Christian concepts without the grounds to do

so, see John Gray’s Straw Dogs (for an atheist’s

perspective) and John Lennox’s Gunning for God (for a Christian’s perspective).

SUMMER 2012 | PULSE ISSUE 11

SELECTED EUROPEAN HIGHLIGHTS:

THE DIARY

THIS LIST DOES NOT INCLUDE ALL OF THE EVENTS THAT OUR SPEAKERS ARE INVOLVED

WITH, BUT IF YOU WANT FURTHER INFORMATION ABOUT ANY OF THE ABOVE PLEASE

CONTACT OUR OXFORD OFFICE.

PLEASE JOIN US IN

PRAYING FOR THESE EVENTS

AND IN PARTICULAR

THOSE SHOWN BELOW:

THE EUROPEAN LEADERSHIP FORUM

This is a major annual event that unites Christian teachers and students from

across Europe. Please pray for all of those attending, including the RZIM team who will be teaching the evangelism track, as well as

giving a number of apologetics seminars.

OCCA YEAR PROGRAMME

The OCCA year programme will be ending in June. Please pray for all of the graduates as they leave Oxford to start the next stage in their lives. Please pray that there will be many opportunities to use the skills that they have learnt and that their ministry will be fruitful.

OCCA SIX-WEEK PROGRAMME

AND THE RZIM SUMMER SCHOOL

At the end of May a new cohort of students will be arriving at the OCCA for the start of the six-week programme. Please pray for those who will be attending this, as

they seek to learn about communicating the gospel more eff ectively in the secular

work environment. The course ends with delegates attending the annual

Oxford Summer School, where they will be joined by another 100 delegates for a week of intensive apologetics teaching.

Please pray that those attending will experience both a deepening faith and a greater knowledge of God.

NEW WINE

Please pray for Michelle Tepper, Vince Vitale and Tom Price who will all be speaking at

New Wine, a major Christian summer festival.

RZIM TRAINING DAY

Please pray for Os Guinness and Vince Vitale, who will be speaking at the next RZIM

training day in Manchester. Please also pray for the on-going work of AiM (Apologetics in Manchester), who are hosting the event.

MAY

19-24 EUROPEAN LEADERSHIP FORUM, EGER, HUNGARY (Team)

26 UNBELIEVABLE? CONFERENCE, LONDON (John Lennox)

26-30 SCOTTISH DISCIPLESHIP FORUM, ARBROATH (Os Guinness)

28 OCCA SIX WEEK PROGRAMME STARTS (Team)

JUNE