Publication: The Straits Times, Saturday Section, p S1, S2 ...

Transcript of Publication: The Straits Times, Saturday Section, p S1, S2 ...

Publication: The Straits Times, Saturday Section, p S1, S2, S3 & S4

Date: 16 February 2008

State of the Arts

The big picture: for Singapore to be a premier centre for arts education. The strategy: build arts schools, and invest big money in the creative

industries. HONG XINYI reports

Publication: The Straits Times, Saturday Section, p S2 & S3

Date: 16 February 2008

Under one groove

HIP HOP: Students at the School of the Arts (SOTA) learn to express themselves during a

hip hop class. It is hoped that a school like SOTA would help bolster Singapore’s cultural-

hub ambitions.

Singapore is putting on the moves to become the region’s premier centre for arts education. Hong Xinyi reports

BECOMING an arts student was not for the faint of heart, at least not when Mr T. Sasitharan was growing up.

“Back then, if you decided to study the arts, you were either considered insane,

because you wouldn’t be able to feed yourself, or useless, because it was assumed you weren’t good enough to get into any other discipline,” says the 50-year-old co-founder and director of the seven-year-old Theatre Training &

Research Programme (TTRP) housed in the serene enclave of Emily Hill.

But times have changed.

“Arts education in Singapore today is unrecognisable,” he says.

Indeed it is. Nowhere is this transformation more visible than in the multimillion-dollar edifices that have been constructed for arts students here.

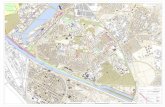

By next year, the new School of the Arts Singapore (Sota) will move into a $100-

million campus currently being built at Kirk Terrace, a stone’s throw away from TTRP.

That will put it in the same neighbourhood as Singapore’s oldest arts school, Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (Nafa), whose first batch of 14 students started classes in 1938.

Today, its 2,232 students attend classes at its three Bencoolen Street campuses,

built at a cost of $110 million in 2004. Also nearby is the 24-year-old Lasalle College of the Arts. Its 2,300 students

moved into its striking new $150-million campus at McNally Street six months ago.

Out west, the Yong Siew Toh Conservatory of Music has its own elegant campus within the National University of Singapore. Launched in 2001 with the support of the Peabody Institute – one of the world’s leading music conservatories – it

boasts studios with cutting-edge recording technology and pristine recital halls.

And over at Nanyang Technological University, the 21/2-year-old School of Art, Design and Media (ADM) – the first local tertiary institution offering Bachelor of Fine Arts degrees – is housed in a $37-million concoction of undulating glass

curves. Not to be left out, the polytechnics have also been building up their respective

niches in the field of animation, film and design.

Republic Polytechnic’s Woodlands campus, for instance, has a breathtaking performing arts centre designed by award-winning Japanese architect Fumihiko Maki.

“The centre allows our students to put into practice the technical theatre skills

they learn here,” says Dr Victor Valbuena, the director of the polytechnic’s

School of Technology for the Arts, which offers courses like technology and arts management. “It’s like a mini-Esplanade, if you will.”

The story doesn’t end here. Last year also saw two prestigious foreign institutions

set up their first Asian branches in Singapore. The London-based Sotheby’s Institute of Art started master’s degree classes in art

business and contemporary art in October.

New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts – whose alumni include heavyweights like Martin Scorsese and Lee Ang – started Master of Fine Arts classes in film and television production in September.

Meanwhile, the Ministry of Education has also, in recent years, launched new Normal (Technical) art and music syllabi and opened up Higher Art and Higher

Music courses to more students.

Economic potential

HOW did this former cultural desert learn to stop worrying and love the arts?

The answer, not surprisingly, has a lot to do with the economic potential of the creative industries.

The idea of setting up a school like Sota first came up in 2002, as part of a review

of secondary and junior college education. The region was then still smarting from the 1997 Asian financial crisis. China’s

surging economy also seemed increasingly threatening to Singapore’s own financial growth.

The review was part of the Government’s Remaking Singapore initiative, which aimed to introduce changes that would create a more freewheeling and

innovative environment. A school like Sota, it was suggested, would help bolster Singapore’s cultural-hub

ambitions.

Two years earlier, the 2000 Renaissance City Report initiated by the Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts (Mica) had pumped $50 million into

the arts over five years.

In 2004, another $200 million over five years was allocated for the creative industries under Mica’s Renaissance City 2.0, DesignSingapore and Media 21 initiatives.

The aim of these measures: to help double the sector’s contribution to GDP by

2012, from 3 per cent to 6 per cent. The presence of Sotheby’s Institute and Tisch in Singapore today owes much to

the Economic Development Board’s (EDB) Global Schoolhouse scheme, which aims to attract 150,000 international students to Singapore by 2015.

Ms Aw Kah Peng, assistant managing director of EDB’s industry development unit, describes a vibrant education sector as “critical”.

She says: “Singapore needs to continue to attract the best talents to maintain our global competitiveness.”

Nafa president Choo Thiam Siew, 56, believes there is no need to shy away from

this pragmatic, goal-oriented view of the arts. “Creative industries are one of the engines of growth, and arts school graduates

must earn a living.

“There is nothing wrong with viewing culture as an industry. Look at how much money The Beatles and Andrew Lloyd Webber have generated for their industries.”

As Professor Isaac Kerlow, dean of NTU’s School of ADM, puts it: “It doesn’t happen very often that building arts schools is part of the national agenda.

That’s really cool.”

Why Asia chosen

FOR foreign schools, Singapore’s attractions are all too familiar: stability,

efficiency and a strategic geographic location.

Dr Pari Shirazi, 52, president of Tisch Asia, says that the idea of a satellite campus was born after 9/11, when applications from international students decreased

due to visa problems and fears about living in New York.

The school decided on Asia, a region it viewed as economically vibrant and ripe with artistic potential. Shanghai and Beijing were considered, but she ultimately felt that it would be too difficult for non-Mandarin-speaking students to survive

outside the campus.

She says: “By being in Singapore, students from Europe and America can easily access other parts of Asia for shooting projects, while our Asian students can still feel that they are in their own backyard.”

The presence of schools like Tisch and Sotheby’s Institute here means more affordable options are now available to local students, contributing to a stronger

arts scene.

Minister for Information, Communications and the Arts Lee Boon Yang told The Straits Times via e-mail: “Students are no longer compelled to go overseas to pursue their interest in the arts. This will help with retention of talent.”

He added that more arts schools could result in more interesting collaborations

between students and a raising of academic standards across the board. And even those graduates who choose not to become arts practitioners will

have an important role to play.

“Many will carry with them a lifelong love of the arts even as they excel in other careers. They will become part of a discerning audience who will help ensure that the arts continues to flourish,” he said.

Being expressive

DESPITE the dramatic changes, some old notions still linger. One potential roadblock is Singapore’s conservative reputation in creative

expression.

“The perception that Singapore is a limiting place spells death for the future of the arts,” says Prof Kerlow. “The main goal is build an environment where

students feel free and compelled to be creative, then the perception will change.”

After all, he reasons, “the most valued commodity in this profession is personal

expression. You can be super successful only if you have something unique to offer”.

Tisch’s Dr Shirazi says the conservative image of Singapore was “absolutely a concern” when it came to choosing a location for the satellite campus.

The authorities, however, assured the school that it would have total academic freedom on campus with regards to teaching materials like the kinds of films

screened in classes. The Media Development Authority has also been helping the students get permission to shoot in various locations in Singapore.

The results, when we dropped in on a screening session one Saturday morning, were striking.

Using a Skype Internet link-up, students from the New York and Singapore campuses introduced themselves to one another before their black-and-white

shorts were screened for both cohorts.

The void decks, multilingual Danger signs and construction cranes of Singapore were framed with the same romantic ardour that the New York students invested in their shots of Manhattan’s fire escapes, brownstones and billboards.

It was almost like watching an aspiring cultural metropolis introducing itself to an

established one. Yong Siew Toh conservatory director Bernard Lanskey, 47, is optimistic that arts

school graduates will transform the physicality and imagination of Singapore in the coming years.

“Historically, any city with a meaningful artistic presence has had to have a certain economic stability, an international perspective and political support for

the arts. “I see all these things in place here. I believe that Singapore is ready to explore its

artistic identity.”

Publication: The Straits Times, Saturday Section, p S4

Date: 16 February 2008

Creativity finds expression here

THE ART OF DANCE: The only two boys in a class of 27 during a dance lesson at SOTA are

Leonard Heng (left) and Thaddaeus Low (second from right), both 12.

Singapore’s new arts school takes its first steps to shape tomorrow’s dancers

WEEK two at the School Of The Arts Singapore (Sota), and there is no trace of post-recess lethargy in sight.

The school hall is filled with the slick, cocky beats of Wall To Wall, a dance track by American R&B heart-throb Chris Brown.

On stage, dance instructor Ryan Tan, from local performing arts centre O School, instructs some of the 239 students in Sota’s first cohort in the basic elements of

hip-hop dance.

“In every dance form, the most important thing is that your fundamentals are strong,” Tan, 34, reminds his young charges, as he coaxes slouchy-cool attitude

into tentative adolescent gestures.

It’s advice that is not lost on 12-year-old Leonard Heng, who has been taking ballroom dancing lessons since he was six years old.

“I want to represent Singapore in international dance competitions,” he says. “I wanted to come to this school because I want to learn to be a better dancer.

The teachers here can teach me how to improve my stamina and flexibility.” Sota is Singapore’s first independent pre-tertiary arts school for students aged 13

to 18, who will experience a six-year integrated arts and academic curriculum, leading to an International Baccalaureate diploma.

It will move into its permanent Kirk Terrace campus next year. Meanwhile, its first intake is getting its first taste of this new experiment in education at the former

LaSalle College of The Arts campus in Goodman Road. Orientation here means a whirlwind tour of creative expression through the ages.

The first week saw the students getting acquainted with pre-historic caveman

drawings and the dances often seen in movie adaptations of Jane Austen novels.

By the time The Straits Times dropped in for a visit, the programme had plunged head-first into the contemporary era (hence the hip-hop).

The aim of the orientation activities, says principal Rebecca Chew, 41, is to introduce the students to Sota’s interdisciplinary ethos.

“By engaging the students in dynamic ways, we want to help them understand the history and evolution of a variety of art forms,” she says.

“We want to teach them how to ask critical questions, cultivate their

independence of thought and encourage them to think about the responsibilities of an artist.”

Over the following weeks, as proper classes begin, the students will be asked to consider scientific concepts like diffusion in the context of arts disciplines like

music.

Sota’s head of science, Ms Suriyani Rahamat, 34, says: “The students have responded very well so far and we are waiting to get into even deeper

questions.”

In a nearby classroom, Visual Arts head and installation artist Ye Shufang leads a discussion about the history and characteristics of graffiti art.

The images she unveils elicit a chorus of admiring wonder from the students: Avant- garde China artist Zhang Dali’s spray-painted silhouettes on Beijing’s

derelict buildings in the 1990s; Singapore artist Luthfi Mustafah’s mural featuring his trademark character, The Killer Gerbil, commissioned by the Singapore Art Museum in 2005.

Ye, 37, patiently guides the class in unpacking the symbolic implications of the images, nudging them with questions rather than answers.

“Does the meaning of graffiti change when it is legalised? Why would an artist

use impermanent materials and spaces for his work?” And, finally, the question that will be repeatedly posed to the students of this

school: “An artist must have something to say to the world. What will you say?”

The question hangs in the humid afternoon air, and goes unanswered – for now. But check back in another 10 years, and there may be some very interesting answers indeed.

Source: The Straits Times © Singapore Press Holdings Limited. Permission

required for reproduction.