HaNSA – Head and Neck, Shoulder & Arm Research Group Last ...

Protocol Paper Abstract Template: · Web viewWhile in Sweden, 13% of computer workers with neck...

Transcript of Protocol Paper Abstract Template: · Web viewWhile in Sweden, 13% of computer workers with neck...

Protocol Paper Electronic Paper Template:

A workplace exercise versus health promotion intervention to

prevent and reduce the economic and personal burden of non-

specific neck pain in office personnel: A cluster randomized

controlled trial

Human research ethics approval committee: The University of Queensland Medical

Research Ethics Committee

Human research ethics approval number: 2012001318

INTRODUCTION

Musculoskeletal disorders such as neck pain are a common threat to productivity in office

workers. In the Netherlands, 26% of computer users with regular or prolonged neck/shoulder

and/or hand/arm symptoms reported that their symptoms affected their productivity (van den

Heuvel et al 2007). While in Sweden, 13% of computer workers with neck or neck/shoulder

pain reported productivity effects at work with the average reduction in productivity in those

experiencing daily pain of nearly 22% (Hagberg et al 2002).

Ergonomic interventions, considered to be industry best practice, appear to positively impact

on outcomes relevant to industry – productivity and absenteeism. In a Scandinavian study,

workers receiving ‘current best practice ergonomic intervention’ reported significantly

improved productivity (Martimo et al 2010) and had significantly fewer sick days compared

with the control group (mean 17.3 versus 23.3 days, at 12 months) (Shiri et al 2011). While

these outcomes are beneficial for the organisation, there is strong evidence that workplace

adjustments alone have no effect on neck/upper extremity musculoskeletal health outcomes

of individuals (Brewer et al 2006, Kennedy et al 2010). In contrast, neck and shoulder girdle

exercises have demonstrated benefits to the individual. Two recent systematic reviews found

strong evidence to support the positive effect of muscle strengthening and endurance

exercises for controlling neck pain in office workers (Coury et al 2009, Sihawong et al 2011).

The exercise intervention was effective in reducing neck pain in office workers with severe

pain by 79%, well beyond that attained by aerobic exercise (leg-bicycling) or the reference

symptomatic at baseline (Andersen et al 2008b). This same exercise protocol was also more

effective in preventing the development of neck–shoulder symptoms in those asymptomatic

at baseline than an all-round physical exercise intervention (Blangsted et al 2008). However

the impact of these exercises on work productivity is unclear.

While there is evidence that multi-modal interventions have additive clinical benefits for

chronic neck pain (Miller et al 2010) there is a lack of quality studies investigating multi-

modal interventions for the primary and secondary prevention of neck pain. The majority of

studies test single interventions but as ergonomic measures are now considered best practice,

it is reasonable to expect that the addition of a validated exercise intervention involving

progressive conditioning (strength/endurance) of neck and shoulder girdle muscles will

demonstrate additional benefits for office workers with neck pain and those at risk of

developing neck pain. We postulate that the addition of a neck exercise intervention

(conditioning the worker) to best practice ergonomic approach (optimising the work

environment) will result in improved productivity and reduced neck pain severity in those

symptomatic at baseline. It is also hypothesised that this multi-modal approach will reduce

the risk of neck pain in those asymptomatic at baseline. If new occupational health

interventions are to be widely adopted and implemented by industry, gains in both

productivity and pain need to be demonstrated.

This research will determine if the addition of a workplace-based neck exercise program to a

best practice ergonomic intervention:

1. Reduces productivity losses in office workers with and without neck pain;

2. Reduces the risk of developing neck pain in office workers without neck problems;

3. Reduces the severity of neck pain in office workers with neck problems.

METHOD

Design

This study will be a prospective parallel arm cluster-randomized controlled trial with a best

practice ergonomic and exercise training (EET) intervention group and a combined best

practice ergonomic and health promotion information (EHP) control group (Figure 1).

Invitation to eligible office personnel

Baseline measures Productivity, pain severity, neck disability, quality of life, physical activity levels, exercise self-efficacy, stage of change,

muscle performance

Randomisation(N = 640 participants

Control Group(N = 320)

Ergonomic & Health Promotion intervention 12 weeks

Intervention group(N = 320)

Ergonomic & Exercise training intervention 12 weeks

Productivity, pain severity, neck disability, quality of life,

physical activity levels, exercise self-efficacy, stage of change,

muscle performance,adherence to exercise

Productivity, Pain, disability, adherence to exercise

Productivity, Pain, disability, adherence to exercise

Productivity, pain severity, neck disability, quality of life,

health beliefs, Physical activity levels, exercise self-efficacy,

exercise stage of change, muscle performance, adherence to exercise

3 months follow up

6 month follow up

9 month follow up

12 month follow up

Productivity, pain severity, neck disability, quality of life,

physical activity levels, exercise self-efficacy, stage of change,

muscle performance,adherence to exercise

Productivity, Pain, disability, adherence to exercise

Productivity, Pain, disability, adherence to exercise

Productivity, pain severity, neck disability, quality of life, health beliefs, Physical activity levels, exercise self-efficacy, exercise

stage of change, muscle performance, adherence to

exercise

Figure 1: Flow chart of study

Participants, therapists, centres

Employees will be recruited from organisations employing large numbers of office personnel

from government and non-government industry sectors. Eligible employees will be any office

worker, aged over 18 years, who work more than 30 hours/week performing office work.

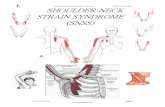

Exclusion criteria will be pregnancy, health conditions such as previous trauma or injuries to

the neck, specific pathologies (e.g., congenital cervical abnormalities, stenosis,

radiculopathy) or inflammatory conditions (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis), any history of cervical

spine surgery or if exercise is contraindicated by their medical practitioner for any reason

(e.g., uncontrolled hypertension, angina). Employees will be encouraged to continue with any

usual exercise or sporting activity for the duration of the research. To avoid potential bias

with only symptomatic cases volunteering, the exercise intervention will be promoted also as

a preventive health initiative rather than an intervention targeting those with neck symptoms.

Qualified health professionals will deliver all interventions (ergonomic, exercise and health

promotion).

Interventions

Both the exercise training intervention group and health promotion group will receive an

individualised current best practice ergonomic intervention conducted by an experienced

health professional. The ergonomic intervention will involve an initial one-hour assessment

and a maximum of one follow-up appointment. Criteria for the ergonomic intervention will

be based on current empirical evidence and best practice using Australian government

guidelines (Comcare 2008). Any necessary equipment will be purchased through the research

project’s funds thereby removing financial barriers and ensuring implementation of the

recommended interventions.

Exercise training (intervention group)

Participants allocated to the training intervention group will also receive a progressive

exercise program shown to be effective in reducing neck pain in office workers (Andersen et

al 2008b, Blangsted et al 2008). The exercises will be performed at the workplace in small

groups of employees, for 20 minutes 3 times a week for 12 weeks. A standard set of exercises

consisting of three exercises each for the neck and shoulder girdle will be prescribed to all

employees but their implementation and progression will be within the specific capabilities of

the individual. Upper cervical flexion (utilised as a warm up exercise), and progressive

resisted lower cervical flexion and extension exercises, will be performed in sitting utilising

varying resistance elastic bands with higher resistances obtained by combining the bands in

parallel or stronger resistance (Figure 2). Shoulder girdle exercises will include bilateral

shoulder flexion and abduction (in the plane of the scapula) to 900 (Figure 3), and bilateral

reverse flyes (Figure 4) using progressive resistance provided by dumbbells and resistive

elastic bands. Training load for each individual will be based on their one-repetition

maximum (1-RM) that will be regularly re-evaluated to ensure appropriate exercise

progression. Each training session will commence with a warm up of ten repetitions at a load

of 50% of 1-RM for each exercise. This will be followed by three sets of 10-20 repetitions of

each exercise at 60-85% of their 1-RM (Mayhew et al 1992). Progression of exercise in this

manner is within guidelines suggested for the principles of periodization and progressive

overload (Kraemer et al 2002). The exact load prescribed for any individual worker, for any

of the exercises at any stage of the exercise program, will be a load at which the individual is

able to perform the exercise with control, particularly with respect to their postural

orientation during the exercise. This is in accordance with contemporary approaches to

exercise for the management of spinal pain (Jull et al 2008).

A B

Figure 2: Lower cervical flexion (2A) and cervical extension (2B) exercises using graded

resistive elastic bands

A B

Figure 3: Resisted shoulder flexion (3A) and abduction (in the plane of the scapula) (3B)

using dumbbells

Figure 4: Reverse flyes against graded resistive elastic bands

The risk of adverse events will be minimised by the health professional supervising one

exercise session per week to ensure the exercises are being performed safely and within the

employee’s capabilities and pain tolerance. Compliance with the 12-week exercise

intervention will be encouraged by the attending health professional. Employees will

maintain a weekly diary to record exercise quantity, intensity and frequency. Adherence with

the exercise intervention on completion of the 12-week intervention will be encouraged with

fortnightly reminder emails. A written detailed copy of each exercise technique, load

intensity, and the number of sets and repetitions will be given to each employee to facilitate

compliance during the 12-week intervention.

Health promotion (control group)

To ensure parity in time with those in the intervention group, employees will be invited to

attend health promotion information sessions for one hour per week for 12 weeks in addition

to the ergonomic intervention. Topics will include information on healthy eating, stress

management, weight loss, relaxation, and cessation of smoking. There will be no structured

physical activity recommendations or specific information on exercise other than the

importance of staying active. Attendance to these sessions will be documented to determine

participation rate.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome:

Productivity Loss will be measured in monetary units calculated using the World Health

Organisation’s Health and Productivity Questionnaire (HPQ), a validated instrument for

measuring self-reported absenteeism and presenteeism rates that is also able to measure the

workplace costs of illness (Kessler et al 2003). This measure has demonstrated excellent

reliability, validity, and sensitivity to change (Kessler et al 2004). Self-reported absenteeism

will be measured by the number of days and part days missed from work in the previous four

weeks and converted to a monetary value using the employee’s wage rate (including on-

costs). Presenteeism will be measured by the HPQ by asking several memory priming

questions around different aspects of job performance (e.g. quality of work, concentration).

Following these questions, the respondent will be asked to rate the performance of an average

person working in a similar job to their own on a scale of performance from 0-10 (worst to

best). The respondents then rate their own performance over the last 4 weeks on the same

scale. Published algorithms will be used to convert the self-rated scale into a monetary value

for lost productivity due to presenteeism based on the employee’s wage rate (Kessler et al

2004). Total productivity loss will be calculated for each individual as the sum of the losses

due to absenteeism and presenteeism in Australian dollars. This outcome measure will be

collected at baseline, immediately after the intervention and at three-monthly intervals for 12

months.

Secondary outcomes:

The severity of neck pain will be evaluated using pain intensity measures over the prior seven

days and prior three months. A body map will be used to clarify the anatomical areas

specified as the neck, shoulder and upper back regions. Employees will record the intensity oftheir worst and average symptoms for the previous three months and degree of pain over the

previous seven days using a 10-point scale ranging from 0 (no pain) to 9 (worst possible pain)

(Kaergaard et al 2000). The validity of this self-report scale has been confirmed in a sample

of workers with clinical signs of neck-shoulder disorders (Kaergaard et al 2000) and the test-

retest reliability reported to be good to excellent for average and worst pain (Brauer et al

2003). Activity restriction due to symptoms in each body region during the previous three

months will also be recorded using the same scale. Our study will define cases as those who

score ≥3 on the 0-9 scale and non-cases as those who score from 0 to 2 on the seven-day

symptom intensity question (Blangsted et al 2008, Zebis et al 2011). These outcome

measures will be collected at baseline, immediately after the intervention and at three-

monthly intervals for 12 months.

The number and severity of concurrent musculoskeletal pain sites will be determined using a

body chart to indicate the anatomical regions of low back, hips, knees, ankles, elbows and

hands. Employees will indicate the presence of symptoms at each site and then the intensity

of symptoms using a 10-point scale ranging from 0 (no pain) to 9 (worst possible pain) during

the previous seven days. An additional pain region will be defined when the reported pain

intensity is three or more (Andersen et al 2010a). These outcome measures will be collected

at baseline, immediately following the intervention and at 12 months follow up.

Cervical flexor/extensor isometric strength [Maximal Voluntary Contraction, MVC] then

endurance will be measured with a dynamometer (Mecmesin BFG 1000N digital force gauge

from SI Instruments Pty Ltd) attached to a seated frame. The thorax of the employees will be

secured by the adjustable backrest of the frame and attached belt anteriorly. The mounted

dynamometer will be height adjustable for accurate recording of extensor (application pad

positioned at the occipital protuberance) and flexor (non-elastic strap at the level of the

forehead) muscle force. Employees will perform a standard warm-up of three sub-maximal

repetitions followed by three trials of maximal contractions with 60s rest between each trial.

The maximal value measured will be recorded as the MVC score. For the endurance test

participants will be required to sustain an isometric effort at 50% of their MVC until task

failure (no longer able to sustain the contraction). The duration for which the employee was

able to sustain the contraction before task failure will be recorded as the endurance measure

(O'Leary et al 2007, O’Leary et al 2012). During testing, standardised visual feedback (live

force display) and verbal encouragement will be provided to the participants. These neck

dynamometry measurements have been shown to have good to excellent test-retest reliability

(ICC 0.7 - 0.99) (O’Leary 2005, Van Wyk et al 2010).

The MVC (kilograms) and endurance (seconds) of the shoulder abductors will be determined

with free weights using a lateral arm raise to 900 shoulder abduction in scapular plane with

the participant standing against a wall (Andersen et al 2010b). The maximal weight lifted

with acceptable technique will be recorded as the 1-RM. Endurance will be determined by the

number of times a weight 1kg lower than MVC can be raised and lowered. Measures of neck

and shoulder muscle strength and endurance will permit evaluation of the impact of the

exercise program on muscle conditioning of neck and shoulder girdle. The muscle strength

and endurance measures will be collected at baseline, immediate and 12 months post-

intervention.

Compliance to exercise during the 12 week structured intervention will be determined from

the weekly diary completed by each participant in the EET. Regular adherence will be

defined as participating at least once a week during the 12-week intervention (Andersen et al

2008a). On completion of the exercise training, adherence will be recorded with two

questions administered electronically monthly to participants in the EET group. One question

will ask about frequency of exercise in the last four weeks and the other about reasons for

absence from training (Zebis et al 2011).

Additional secondary outcomes evaluated at baseline, immediately following and 12 months

post intervention include: the degree of neck disability [Neck Disability Index (Vernon

1996)]; health related quality of life [20 item Assessment of Quality of Life Scale, (AQoL

instruments 2009, Hawthorne et al 1999)]; physical activity levels [short-form International

Physical Activity Questionnaire, (Craig et al 2003)]; self-efficacy to undertake exercise for

20 minutes, three times a week despite various barriers [six questions on a 5-point Likert

scale (Pedersen et al 2013)] and individual stage of change in relation to regular exercise [one

question (Marcus et al 1992)].

Consultation with a health professional due to problems in the neck/shoulder region and the

number of workers’ compensation claim submitted in the previous 12 months will be

evaluated with one question each at baseline and 12 months post-intervention.

The following data will be collected at baseline to control for potential confounding:

Demographic information including age, gender, body mass index, hand dominance,

occupational category, income range, education level, number of comorbidities,

medication use for neck symptoms;

Duration of computer work performed will be evaluated with self-assessment of hours

worked per day with a computer;

Health beliefs will be assessed using three questions from the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs

Questionnaire (Hoe et al 2011);

Three domains of workplace psychosocial factors will be assessed using the 18-item

version of the Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ) (Karasek et al 1998, Mausner-Dorsch and

Eaton);

Job Satisfaction will be evaluated with a single item using both words and pictures

(faces) (Kunin 1955, Wanous and Hudy 2001, Wanous et al 1997);

The mental health status of the individual will be recorded with the Kessler 6 scale

(Burgess 2007).

Procedure

An invitation to participate will be sent from the project coordinator to the workplace liaison

for distribution to office personnel. Interested employees will be directed to a project website

with information about the research, consent form, as well as questions to determine

eligibility and their work location (to establish clusters). The project coordinator will allocate

eligible employees to a cluster until the required number (5-8) is reached for each intake. A

statistician blinded to the identity of the individuals will assign clusters by simple random

allocation to either the control or training group (i.e. individuals will be randomized at the

cluster level). A cluster is defined as a small group of people located in the same building,

floor or work group. This approach will be used to avoid contamination of the intervention; to

enhance compliance with the intervention and to implement the intervention in a natural work

environment. The project coordinator will notify individuals of their allocation after baseline

measures have been collected, and communicate between participants and the intervening

health professional to organize the ergonomic and exercise assessments. The study will

commence in July 2013 with an anticipated final intake of participants in July 2015. The

participants receiving and the health professional delivering each intervention cannot be

blinded to the intervention group. A second different health professional will be collecting the

outcome measures and will be blinded to group allocation.

Data analysis

The data will be analysed on an ‘intent to treat’ basis and per protocol. The effect of the

intervention on productivity over the study period will be examined using multi-level

generalized linear models. This model will be able to deal with the non-normal nature of the

cost data as well as adjust for the effects of clustering as individuals will be nested within

each cluster. Secondary outcomes will be analysed by appropriate statistical methods for the

type of data. Statistical Models will be developed in consultation with a biostatistician and

will adjust for clustering and baseline factors if necessary. We will investigate the distribution

of gender and symptoms across the intervention and control groups. In case of uneven

distribution, these factors will be included in the model to adjust for their potential

confounding effects. Case status will be examined to see whether it modifies the relationship

of interest, and if an effect modifier, stratified results will be presented separately. All

statistical analyses will be performed using Stata statistical software (StataCorp 2012). An

alpha level of 0.05 will be accepted as significant. Missing data will be examined to determine

its randomness and addressed with multiple imputations, if required.

Power analysis

A break-even point for the organisation comparing the costs of implementing the program to

changes in productivity was used to calculate the sample size. Cost of implementing a 12-

week exercise program with one initial assessment was calculated using physiotherapy costs

of conducting assessments and exercise programs for Q-Comp (Q-Comp 2011) The cost of

time off work to participate in the program (one hour per week) for employees was calculated

using the current average office administration wage from Australian data (My Career 2012).

Summing the health professional time costs and employee lost time costs, the total cost of the

program to the employer was estimated to be $896.80 over 13 weeks. Therefore the

improvement in productivity (changes in absenteeism and presenteeism) needed to be at least

$896.80 for the organisation to break-even. Previous Australian research measuring

productivity loss due to illness using the HPQ found an average productivity loss per office

worker (adjusted to current salaries) from absenteeism and presenteeism of $2,812 (SD

$4,133) annually (Hilton et al 2008). Estimated employee numbers based on achieving a

$900 difference in means at a power of 80% and a one-sided, alpha error of 0.05 indicated

that 262 employees would be needed in each group.

The study design incorporates randomisation of clusters of workers. The extent to which

power is diminished by clustering relates to the design effect (D) = 1 + (m - 1) r (Cohen

1988), where m = the average size of a cluster and r = the intra-class correlation coefficient.

Typically, intra-class correlation coefficients are small (< 0.02) (Ukoumunne et al 1999), and

we have used a conservatively estimated intra-class correlation of 0.02. A mean cluster size

of six is anticipated and based on an ideal number per exercise class, D = 1 + (6 - 1) * 0.02 =

1.1, thus total sample size required is (262 * 2 * 1.1) = 576. With an anticipated loss to

follow-up of 10%, the total number of employees to be invited is 640. This sample is similar

to other studies using this neck exercise protocol in office workers (Blangsted et al 2008).

DISCUSSION

Approximately one in two office workers in Australia is affected by neck pain during their

working career. This study is the first to combine evidence-based ergonomic and exercise

interventions not only for the prevention of neck symptoms but also for the management of

neck pain in office workers. It is also the first to evaluate the impact of an intervention

relevant to both the employer (lost productivity) and the worker (perceived neck pain).

This project has several strengths including the innovative design of the interventions with

both ‘control’ and exercise training groups receiving similar time with a health professional.

The benefit for industry and employees is the comprehensive evaluation of these best-practice

interventions that will significantly contribute to informed decision making for the prevention

and management of neck pain in the workplace. The simplicity and availability of the

interventions to be tested ensure they will have immediate application in industry.

As with any intervention study there is the potential for participants to drop-out or non-

attendance for varying reasons. Another limitation is the unpredictability of the economy

with organizational restructuring or downsizing a possibility in the current financial climate

which may impact recruitment rates. There is also the risk of contamination of interventions

with participation of workers from the same organisation allocated to either arm. These

limitations will be minimised by strategic recruitment of work groups rather than a whole of

organisation.

In conclusion, this trial will impact on physiotherapy practice by offering evidence for the

primary and secondary prevention of non-specific neck pain in office personnel. A common

concern of industry is that while primary prevention of musculoskeletal problems is a worthy

endeavour, little evidence for its potential impact on productivity and health exists. Similarly,

the value of interventions to reduce neck pain should not only impact on the individual but

also on the organisation’s costs. In other words, interventions recommended and

implemented by health professionals are more likely to be implemented and sustained if they

offer some financial incentive for the employer to ensure it is a worthy investment.

Conflict of interest declaration:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements:

The authors acknowledge the assistance of Gwendolen Jull, Paul Scuffham and Bill Vicenzino in the preparation of this project. Shaun O’Leary is supported by a Health Practitioner Research Fellowship (Queensland Health nd University of Queensland and CCRE Spinal Pain, Injury and Health). Leon Straker is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Senior Research Fellowship.

REFERENCES

Andersen LL, Christensen KB, Holtermann A, Poulsen OM, Sjøgaard G, Pedersen MT,

Hansen EA (2010a) Effect of physical exercise interventions on musculoskeletal pain

in all body regions among office workers: A one-year randomized controlled trial.

Manual Therapy 15: 100-104.

Andersen LL, Jorgensen MJ, Blangsted AK, Pedersen MT, Hansen EA, Sjogaard G (2008a)

A randomized controlled intervention trial to relieve and prevent neck/shoulder pain.

Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 40: 983-990.

Andersen LL, Kjaer M, Sogaard K, Hansen L, Kryger AI, Sjogaard G (2008b) Effect of two

contrasting types of physical exercise on chronic neck muscle pain. Arthritis &

Rheumatism 59: 84-91.

Andersen LL, Zebis MK, Pedersen MT, Roessler KK, Andersen CH, Pedersen MM, Feveile

H, Mortensen OS, Sjogaard G (2010b) Protocol for work place adjusted Intelligent

physical exercise reducing musculoskeletal pain in shoulder and neck (VIMS): a

cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 11: 173.

AQoL instruments (2009) htt p:/ /www.aqol.com.a u/ [Accessed

Blangsted AK, Sogaard K, Hansen EA, Hannerz H, Sjogaard G (2008) One-year randomized

controlled trial with different physical-activity programs to reduce musculoskeletal

symptoms in the neck and shoulders among office workers. Scandinavian Journal of

Work, Environment & Health 34: 55-65.

Brauer C, Thomsen JF, Loft IP, Mikkelsen S (2003) Can we rely on retrospective pain

assessments? American Journal of Epidemiology 157: 552-557.

Brewer S, Van Eerd D, Amick B, Irvin E, Daum K, Gerr F, Moore SJ, Cullen K, Rempel D

(2006) Workplace interventions to prevent musculoskeletal and visual symptoms and

disorders among computer users: A systematic review. Journal of Occupational

Rehabilitation 16: 325-358.

Burgess P (2007) Australian Mental Health Outcomes and Classification Network. Cochrane

Database of Systematic.

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences edn). Hillsdale, NJ,

Erlbaum.

Comcare CoA (2008) Officewise: A Guide to Health and Safety in the Office. Cochrane

Database of Systematic Reviews: 1-90.

Coury HJCG, Moreira RFC, Dias NB (2009) Evaluation of the effectiveness of workplace

exercise in controlling neck, shoulder and low back pain: a systematic review. Revista

Brasileira de Fisioterapia 13: 461-479.

Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, Pratt M,

Ekelunk U, Yngve A, Sallis JF, Oja P (2003) International physical activity

questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Medicine and Science in Sports and

Exercise 35: 1381-1395.

Hagberg M, Tornqvist EW, Toomingas A (2002) Self-reported reduced productivity due to

musculoskeletal symptoms: associations with workplace and individual factors among

white-collar computer users. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation 12: 151-161.

Hawthorne G, Richardson J, Osborne R (1999) The Assessment of Quality of Life (AQoL)

instrument: a psychometric measure of health-related quality of life. Quality of Life

Research 8: 209-224.

Hilton MF, Scuffham PA, Sheridan J, Cleary CM, Whiteford HA (2008) Mental ill-health

and the differential effect of employee type on absenteeism and presenteeism. Journal

of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 50: 1228-1243.

Hoe VC, Kelsall HL, Urquhart DM, Sim MR (2011) Risk factors for musculoskeletal

symptoms of the neck or shoulder alone or neck and shoulder among hospital nurses

Occupational and Environmental Medicine.

Jull G, Sterling M, Falla D, Treleaven J, O'Leary S (2008) Whiplash, headache and neck

pain. Research based directions for the physical therapies edn). Edinburgh: Elsevier.

Kaergaard A, Andersen JH, Rasmussen K, Mikkelsen S (2000) Identification of neck-

shoulder disorders in a 1 year follow-up study. Validation of a questionnaire-based

method. Pain 86: 305-310.

Karasek RA, Berisson C, Kawakami N, Houtman I, Bongers PM, Amick B (1998) The Job

Content Questionnaire: an instrument for internationally comparative assessments of

psychosocial job characteristics. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 3: 322-

355.

Kennedy CA, Amick BCI, Dennerlein JT, Brewer S, Catli S, Williams R, Serra C, Gerr F,

Irvin E, Mahood Q, Franzblau B, Van Eerd D, Evanoff B, Rempel D (2010)

Systematic Review of the Role of Occupational Health and Safety Interventions in the

Prevention of Upper Extremity Musculoskeletal Symptoms, Signs, Disorders,

Injuries,Claims and Lost Time. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation 20: 127-162.

Kessler RC, Ames M, Hymel PA, Loeppke R, McKenas DK, Richling DE, Stang PE, Ustun

TB (2004) Using the World Health Organization Health and Work Performance

Questionnaire (HPQ) to evaluate the indirect workplace costs of illness. Journal of

Occupational and Environmental Medicine 46: S23-S37.

Kessler RC, Barber C, Beck A, Berglund P, Cleary PD, McKenas D, Pronk N, Simon G,

Stang P, Ustun TB, Wang P (2003) The World Health Organisation Health and Work

Performance Questionnaire (HPQ). Journal of Occupational and Environmental

Medicine 45: 156-174.

Kraemer WJ, K. A, Cafarell iE, al. e (2002) American College of Sports Medicine position

stand. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Medicine and

Science in Sports and Exercise 34: 364-380.

Kunin T (1955) The construction of a new type of attitude measure. Personnel Psychol 51:

823-824.

Marcus BH, Selby VC, Niaura RS, Rossi JS (1992) Marcus BH, Selby VC, Niaura RS, Rossi

JS. Self-efficacy and the stages of exercise behavior change. Res Q Exerc Sport 1992;

63: 60-6. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 63: 60-66.

Martimo K-P, Shiri R, Miranda H, Ketola R, Varonen H, Viikari-Juntura E (2010)

Effectiveness of an ergonomic intervention on the productivity of workers with upper-

extremity disorders – a randomized controlled trial. Scandinavian Journal of Work,

Environment and Health 36: 25-33.

Mausner-Dorsch H, Eaton WW (2000) Psychological work environment and depression:

Epidemiologic assessment of the demand-control model. American Journal of Public

Health 90: 1765-1770.

Mayhew JL, Ball TE, Arnold MD, Bowen JC (1992) Relative muscular endurance

performance as a predictor of bench press strength in college men and women.

Journal of Applied Sport Science Research 6: 200-206.

Miller J, Gross A, D'Sylva J, Burnie S, Goldsmith C, Graham N (2010) Manual therapy and

exercise for neck pain: A systematic review. Manual Therapy 15: 334-354.

My Career (2012) Administration / Office Support Salary Centre.

htt p:/ /content.m yc ar eer.c om.au/salar y-c entre/admi nist rati on -office -support [Accessed

23 January, 2012].

O'Leary S, Jull G, Kim M, Vicenzino B (2007) Cranio-cervical flexor muscle impairment at

maximal, moderate, and low loads is a feature of neck pain. Manual Therapy 12: 34-

39.

O’Leary S (2005) Development of a New Method of Measurement of Cranio-Cervical Flexor

Muscle Performance Cochrane Database of Systematic.

O’Leary S, Jull G, Kim M, Uthaikhup S, Vicenzino B (2012) Training mode dependent

changes in motor performance in neck pain. Archives of Physical Medicine and

Rehabilitation 93: 1225-1233.

Pedersen MM, Zebis MK, Poulsen OM, Mortensen OS, Jensen BR, Sjogaard G, Bredahl T,

Andersen LL (2013) Influence of Self-Efficacy on Compliance to Workplace

Exercise. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine published online 2012.

Q-Comp TWsCRA (2011) Physiotherapy services table of costs.

htt p:/ /www.qcomp.com.au/m edia/8391/ph ysiot her ap y% 20table%20o f%20c osts %202

011.pdf [Accessed 23 January, 2012].

Shiri R, Martimo K-P, Miranda H, Ketola R, Kaila-Kangas L, Helena L, Karppinen J,

Viikari-Juntura E (2011) The effect of workplace intervention on pain and sickness

absence caused by upper-extremity musculoskeletal disorders. Scandinavian Journal

of Work, Environment and Health 37: 120-128.

Sihawong R, Janwantanakul P, Sitthipornvorakul E, Pensri P (2011) Exercise therapy for

office workers with nonspecific neck pain: a systematic review. Journal of

Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics 34: 62-71.

StataCorp (2012) Stata/SE. Cochrane Database of Systematic.

Ukoumunne OC, Gulliford MC, Chinn S, Sterne JA, Burney PG (1999) Methods for

evaluating area-wide and organisation-based interventions in health and health care: a

systematic review. Health Technology Assessment 3: iii-92.

van den Heuvel S, Ijmker S, Blatter BM, de Korte E (2007) Loss of productivity due to

neck/shoulder symptoms and hand/arm symptoms: Results from the PROMO-study.

Journal of Occupational Rehabiliation 17: 370–382.

Van Wyk L, Jull G, Vicenzino B, Greaves M, O’Leary S (2010) A comparison of cranio-

cervical and cervico-thoracic muscle strength in healthy individuals. Journal of

Applied Biomechanics 26: 400-406.

Vernon H (1996) The neck disability index: patient assessment and outcome monitoring in

whiplash. Journal of Musculoskeletal Pain 4: 95-104.

Wanous JP, Hudy MJ (2001) Single-item reliability: A replication and extension.

Organizational Research Methods 4: 361-375.

Wanous JP, Reichers AE, Hudy MJ (1997) Overall job satisfaction: How good are single

item measures? Journal of Applied Psychology 82: 247-252.

Zebis L, Andersen L, Pedersen MT, Mortensen P, Andersen CH, Pedersen MM, Boysen M,

Roessler KK, Hannerz H, Mortensen OS, Sjøgaard G (2011) Implementation of

neck/shoulder exercises for pain relief among industrial workers: A randomized controlled

trial. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 12: 205.