Past, Present and Future for Thirteenth-Century …3 Past, Present and Future for Thirteenth-Century...

Transcript of Past, Present and Future for Thirteenth-Century …3 Past, Present and Future for Thirteenth-Century...

1 eBLJ 2013, Article 13

Past, Present and Future for Thirteenth-Century Wales: Two Diagrams in British Library, Cotton Roll XIV.12

Laura Cleaver

Amongst the relatively small group of illustrated histories from thirteenth-century Britain, a roll in the British Library, Cotton Roll XIV.12, is remarkable for its size, scope and, to a lesser degree, format. William H. Monroe aptly observed that it might best be termed ‘prodigious’, and summarized the roll as ‘a locus classicus of the practice of collecting items on ecclesiastical and secular history, real and legendary, and stringing them together in chronological sequence’.1 Originally over sixteen metres long (with portions now missing), and tracing the descent of humanity from Adam to the reign of William Rufus in images and Latin text, it contains a vast amount of information about humanity’s past, and Anglo-Norman history in particular. Moreover, at the end of the roll, text and images relating to Battle Abbey and Brecon Priory suggest a context for the production of this remarkable history in one of those Benedictine houses. In addition, the roll begins with two diagrams that offer frameworks for the understanding of history; past, present and future. Versions of one of these diagrams, often described as the Septenarium Pictum, are also found in other thirteenth-century rolls showing Christ’s genealogy, but the second diagram offers a more unusual vision of history, from creation to the end of time, which represents contemporary interests in morality. Whilst a detailed examination of the entirety of this roll is beyond the scope of this article, a study of these diagrams allows an exploration of approaches to the past in thirteenth-century Britain.2 In particular the use of imagery and the sources quoted in the diagrams may help to shed light upon the purpose, maker and audience for this object, as well as the context in which it was produced.

The origins of the roll

On stylistic grounds Cotton Roll XIV.12 may be dated to the thirteenth century and associated with Britain. These general claims are corroborated by details on the roll, but whilst the content seems to offer clues about the time and place of production, as appropriate

I am very grateful to all those who have patiently listened to my ideas as they were in progress and asked challenging questions. In particular I would like to thank Stephen Church, Kati Ihnat, Julian Luxford and Laura Slater for their insights and advice. In addition, Helen Conrad O’Briain has been most generous in dealing with my queries about the text (all remaining errors are my own). I am also extremely grateful to the British Library for allowing me to spend days wrestling with the Cotton Roll. This research has been generously funded by a Marie Curie Actions Grant (FP7) as part of the History Books in the Anglo-Norman World project.

1 W. H. Monroe, ‘Thirteenth- and Early Fourteenth-Century Illustrated Genealogical Manuscripts in Roll and Codex: Peter of Poitiers’ Compendium, Universal Histories and Chronicles of the Kings of England’ (unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of London, 1989), pp. 226-7.

2 For a list of the roll’s contents see Monroe, ‘Thirteenth’, pp. 517-19.

2

Past, Present and Future for Thirteenth-Century Wales: Two Diagrams in British Library, Cotton Roll XIV.12

eBLJ 2013, Article 13

for an account of human history, the evidence for dating and precise location is far from straightforward. The genealogical diagram on what appears to be the main side of the roll traces Biblical history from Adam to Christ, following a format associated with Peter of Poitiers (although with more content in both text and images than most copies of the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries) (fig. 1).3 After Christ, Peter is presented as the first in the line of popes that runs down the centre of the roll, providing a visual backbone for the rest of the schema. Gregory the Great is given particular attention; in a larger roundel he is shown being inspired by the Holy Spirit in the form of a bird. Part of his importance in this scheme lies in his decision to send Augustine to England, and Augustine appears to the left of Gregory in a smaller circle at the head of a line of archbishops of Canterbury. The popes are also accompanied by lines of European rulers including the Anglo-Saxon kings and the dukes of Normandy who took control of England in 1066, as well as emperors, and the Frankish and Carolingian kings. In this they provide a visual expansion of the lists of rulers often included at the start of chronicles. One of the remarkable features of this roll is that for the bulk of the diagram each individual is represented by a drawing of a head (with larger images for important figures, as in other rolls). However towards the end of the roll the inclusion of both names and images tails off, leaving blank circles connected by pairs of lines. This suggests that the roll was never finished, and that the maker may have intended to continue it, as the lines run to the end of the roll, and the final text breaks off mid-sentence. Although the roll concludes with the rule of William Rufus and the final text deals with events in Normandy in 1091, therefore, this is not an indication of its date of production.4 A better clue to the date of the roll’s creation may be found on the reverse, where, amongst a collection of texts about historical matters and time, a table contains the dates of Easter from 1065 to 1233, suggesting that the roll was produced in an ecclesiastical milieu.5 The former date emphasizes the importance of the conquest for the maker of the roll, whilst the latter date may give an indication of when the roll was produced. However it is not certain that this did not represent a past or future date and, for reasons that will be explored later, the 1233 date sits rather awkwardly with some of the other contents of the roll.

Returning to the genealogy, some of the figures included in the later portion may shed light on the circumstances of the roll’s production. The major (although not exclusive) source for the text dealing with the Middle Ages in the Cotton Roll is William of Malmesbury’s Gesta Regum Anglorum, whilst the details for British rulers before the start of William’s text is largely supplied by Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae.6 However towards the end of the roll additional material is incorporated to describe the family of Bernard of Neufmarché, who controlled lands in the Welsh marches, and the gift of Brecon Priory to Battle Abbey by Bernard and his wife.7 Part of Bernard’s family is also represented in a diagram. Some of the relevant text is comparable with sections of The Chronicle of Battle Abbey, and the importance of both sites is underlined by the inclusion of images of Battle Abbey and Hastings, together with a blank space labelled ‘Brecon’ (Brectonia).8 The familiarity of the artist with his subject is suggested by the fact that Hastings is represented as a town on a cliff lapped by waves, rather than a generic image of a city; however a degree of confusion is perhaps indicated by the fact that the image of Battle is labelled Hastings, and vice versa (fig. 2). The sequence of execution was evidently flexible, as although the text

3 See W. H. Monroe, ‘A Roll-Manuscript of Peter of Poitiers’ Compendium’, The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art, lxv (1978), pp. 92-107, 138; S. Panayotova, ‘Peter of Poitiers’s Compendium in Genealogia Christi: The Early English Copies’, in R. Gameson and H. Leyser (eds.), Belief and Culture in the Middle Ages (Oxford, 2001), pp. 327-41; P. S. Moore, The Works of Peter of Poitiers (Notre Dame, 1936).

4 Monroe, ‘Thirteenth’, p. 517.5 Monroe, ‘Thirteenth’, p. 518.6 Monroe, ‘Thirteenth’, pp. 517-19.7 Monroe, ‘Thirteenth’, p. 229.8 Monroe, ‘Thirteenth’, p. 517.

3

Past, Present and Future for Thirteenth-Century Wales: Two Diagrams in British Library, Cotton Roll XIV.12

eBLJ 2013, Article 13

Fig. 1. Adam and Eve and their offspring. BL, Cotton Roll XIV.12.

Fig. 2. Battle Abbey and Hastings (mislabelled). BL, Cotton Roll XIV.12.

4

Past, Present and Future for Thirteenth-Century Wales: Two Diagrams in British Library, Cotton Roll XIV.12

eBLJ 2013, Article 13

is written around the images of Battle and Hastings, space has been left for Brecon. The alignment of the image of Hastings, rather than Battle, with a circle for the abbot of Battle Abbey, however, suggests that the images were drawn in the wrong place. The format of the roll makes it difficult to compare sections of script, but it seems to have been written in a single hand, and it is plausible that this hand was also responsible for the imagery.9 The confused identification of the sites is thus most likely to be a mistake, rather than a lack of knowledge about the name of the abbey. That it was not corrected, however, may indicate limited use of the roll.

An interest in Battle Abbey is also evident in some adaptations to William of Malmesbury’s text. Thus on the death of William the Conqueror, Malmesbury’s claim that William Rufus ‘decorated his father’s monument conspicuously with a mass of silver and gold and gleaming stones’, is altered on the roll to specify that the monument was at Battle Abbey.10 The Chronicle of Battle Abbey records the gift of William’s royal cloak and a reliquary with three hundred relics on his death, though it does not suggest that there was a monument to William on that site.11 Beneath the image labelled Battle is a large circle for Abbot Gausbert, and the surrounding text describes the foundation of Battle Abbey and Gausbert’s consecration as abbot. However the latter part of this text pertains specifically to Brecon Priory, as, in a section of text that is very similar to part of Battle Abbey’s Chronicle, it describes how two monks, Roger (who is also named in a roundel on the right edge of the roll, which was presumably intended to contain an image representing him) and Walter, persuaded Bernard to give the Brecon church to Battle and worked to rebuild it, suggesting a particular association between the former site and the roll.12 The emphasis on Brecon is strange if the roll was intended primarily for Battle, and it thus seems likely that, as Monroe tentatively concluded, the roll was made for and possibly at Brecon Priory.13

The material about Bernard of Neufmarché’s family concentrates on the division of his property between his heirs. The text begins with Miles de Pitres’s creation as Earl of Hereford, and his marriage to Bernard’s daughter, by which he became lord of Brecon. Miles’s own inheritance was in Gloucestershire and Herefordshire, and his family’s associations with Gloucester might help to account for the inclusion of an image of that city earlier in the roll (although the city is also mentioned in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s text).14 Both Bernard and Agnes are named in the genealogical diagram, and the lines connecting them to their daughter are labelled ‘filia’, though her circle is missing her name (Sybil). This may be the result of incompleteness, rather than ignorance, however, as the circle representing Miles is also unlabelled, but a note above the next tier of circles identifies them as representing ‘the sons and daughters of Miles, Earl of Hereford’.15 The text of the roll records that each of Miles’s four sons succeeded to the inheritance in turn, but it does not name them, and the four circles in the diagram are similarly blank. On the death of the last brother without issue the inheritance was split between Miles’s daughters. There seems to be some confusion in the text about these women, although part of the roll with the relevant text is lost at this point. The first daughter is named as Margaret (corrected from Lucy) who married Humphrey de

9 Monroe, ‘Thirteenth’, p. 519.10 ‘Patris etiam memoriam in monasterium belli congerie argenti et auri cum gemmarum luce conspicue

adornauit’; see also William of Malmesbury, Gesta Regum Anglorum: The History of the English Kings, ed. & trans. R. A. B. Mynors, R. M. Thomason and M. Winterbottom (Oxford, 1998), vol. i, pp. 512-13.

11 The Chronicle of Battle Abbey, ed. & trans. E. Searle (Oxford, 1980), pp. 90, 96, 100.12 The Chronicle of Battle Abbey, pp. 86-9; Monroe, ‘Thirteenth’, p. 230.13 Monroe, ‘Thirteenth’, p. 519.14 D. Walker, ‘Miles of Gloucester, Earl of Hereford’, Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological

Society, lxxvii (1958), pp. 66-84; the other sites represented on the roll are Jerusalem, Ephesus, Carthage, Troy, London, York and Canterbury.

15 ‘Filii et filiae Milonis comitis Herefordie’.

5

Past, Present and Future for Thirteenth-Century Wales: Two Diagrams in British Library, Cotton Roll XIV.12

eBLJ 2013, Article 13

Bohun and inherited the Earldom of Hereford. She is also named in the second of the three circles representing the sisters in the diagram, which is connected to a circle above probably representing her husband, and two circles below suggesting their offspring, all of which are blank. The second sister is named as Lucy. Part of the text is missing, but she is identified as the wife of William de Braose. Lucy is also named in the first of the circles representing the sisters, which is again connected to further circles representing her husband and children, none of which contain names. A third sister is identified as Joanna in the text and associated with Herbert FitzHerbert and lands in Blaenllyfni and Dinas.16 This sister is presumably represented in the third blank circle in the diagram, which is again connected to circles for husband and offspring. The rest of the text then describes the inheritance of the Brecon land by the heirs of William de Braose, and the Blaenllyfni and Dinas lands by Herbert’s successors. The land division amongst the wives of these men is supported by other sources, including documents associated with Brecon Priory, but the names given here are unusual, as Lucy was the wife of Herbert FitzHerbert, whilst Bertha married William de Braose.17 As with the evidence of the image of the sites singled out for particular attention, therefore, the material presented here seems contradictory. The maker was clearly concerned with the founding family, but was oddly ill-informed or careless about some of the details, although the inclusion of alternative names may suggest a concern about his source.

The inheritance of the Brecon lands had a particular resonance in the middle of the thirteenth century and surviving documentary sources provide some intriguing evidence that may shed light on the circumstances of the roll’s production. William de Braose’s great-grandson, also called William, inherited the Brecon lands and married Eva Marshal, by whom he had four daughters (fig. 3).18 This William was executed by Llwelyn the Great in 1230 when, whilst visiting Llwelyn to arrange a marriage between the latter’s son Dafydd and William’s daughter Isabel, William was caught in adultery with Llwelyn’s wife.19 From 1230, therefore, the division of his lands became a significant political issue. Eva Marshal claimed Brecon as her dower lands, although the king retained the castles, which with the wardship of her daughters passed to Eva’s father William Marshal.20 After his death the wardship came into the hands of Richard of Cornwall, who in turn granted the rights to Eva’s brother Gilbert Marshal in 1235.21 In 1236/7 Eva contracted a debt of 800 marks to the king and Gilbert.22 In 1242 the king demanded 650 marks remaining from a debt of 800 marks from the Earl of Hereford for a fine which Eva had incurred with the king ‘for having the custody and marriage of Eleanor, her daughter’.23 It seems plausible that both documents refer to the

16 ‘Tertia soror nomine Johanna in camera regis innupta [...] sit. Quam concupiscens Herebertus filius Hereberti vel vi vel voluntate ad se illectam in conjugium ascunt(?), sperans s[...]ta parte comitatus tertia adipisci scilicet Blendlevelni et Dinas et alia quae plura’.

17 W. Rees, ‘The Mediaeval Lordship of Brecon’, Transactions of the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion (1915-16). pp. 165-224; R. W. Banks, ‘Cartularium Prioratus S. Johannis Evang. De Brecon’, Archaeologia Cambrensis, xiii (1882), pp. 275-308, xiv (1883), pp. 18-49, 137-68, 221-36, 274-311.

18 See also L. E. Mitchell, Portraits of Medieval Women: Family, Marriage and Politics in England 1225-1350 (New York, 2003), pp. 45-7.

19 Matthew Paris, Chronica Majora, ed. H. R. Luard (London, 1876), vol. iii, p. 194; Rees, ‘The Mediaeval Lordship of Brecon’, p. 189.

20 Rees, p. 189; The Close Rolls of the Reign of Henry III 1227-1231 (London, 1902), pp. 354-5; R. F. Walker, ‘Hubert de Burgh and Wales, 1218-1232’, English Historical Review, lxxxvii (1972), pp. 483-4.

21 Rees, ‘The Mediaeval Lordship of Brecon’, pp. 189-91; Walker, pp. 484-6; Calendar of the Charter Rolls Preserved in the Public Record Office, vol. i (London, 1903), p. 192; see also The Book of Fees Commonly Called ‘Tesya de Nevill’, vol. i, 1198-1242 (London, 1920), p. 396.

22 Calendar of the Fine Rolls of the Reign of Henry III Preserved in the National Archives, vol. iii (London, 2009), p. 219.

23 Fine Rolls, vol. iii, pp. 503-4.

6

Past, Present and Future for Thirteenth-Century Wales: Two Diagrams in British Library, Cotton Roll XIV.12

eBLJ 2013, Article 13

Fig. 3. Family tree.

7

Past, Present and Future for Thirteenth-Century Wales: Two Diagrams in British Library, Cotton Roll XIV.12

eBLJ 2013, Article 13

same debt, and that at some point between 1236 and 1242 Eva and Humphrey de Bohun, Earl of Hereford, arranged the marriage of Eva’s daughter Eleanor and Humphrey’s son, also called Humphrey. The date may be refined further by the fact that in 1241 Humphrey de Bohun junior was granted ‘the honour of Brecon which his predecessors were accustomed to have’ (my emphasis).24 Although Humphrey’s primary claim to the lands lay in his marriage to the De Braose heiress, this document may hint at an acknowledgement that he also had a familial claim in his own right as the great-great grandson of Miles’s daughter Margaret (fig. 3). Humphrey’s claims, however, were contested by Llywelyn’s son David, and Matthew Paris connected this with hostilities in 1244.25 The marriages and contemporary politics might thus have revived interest in the founding family of Brecon Priory and claims to the Brecon lands. Against this backdrop, the inclusion of the references to Bernard’s inheritance taken with the date 1233 on the reverse might suggest a production date for the roll in the 1230s or 1240s.26 Given the roll’s association with Brecon, the 1233 date takes on additional significance, as some chronicles give this as the year in which Llywelyn attacked the town, burning it to the ground after a month-long siege.27 However control of the Welsh Marches continued to be disputed in the latter part of the century. Eleanor de Bohun died in 1251/2, and the Brecon land passed to her son when he came of age in 1270.28 By this time, however, the Welsh had control of the area, and Humphrey fought to reclaim it, establishing lasting control by 1277.29

Whilst the historical evidence is, at best, circumstantial for understanding the production of the roll, the political instability of this period might explain a desire to preserve a record of the community at Brecon’s history. In this context the format of the roll may be significant, as in this period rolls were associated with official records.30 Peter of Poitiers’s genealogy seems to have circulated relatively widely in roll form as well as in codices, but texts such as William of Malmesbury’s were much more commonly found in books. This text has had to be adapted to the new format, resulting in a textual layout that is not always easy to follow, as text is fitted around the genealogical diagram. The association of rolls with record-keeping may thus have contributed to the maker’s decision to use this format, as well as the potential to create a large-scale visual schema, incorporating the founders of Brecon Priory, whose descendants had continued to support the foundation.31

24 ‘Mandatum est vicecomiti Hereford’ quod permittat H. de Bohun, comitem Hereford’, habere omnes libertates in comitatu suo de honore de Brekenn quas predecessores sui habere consueverunt in eodem comitatu de predicto honore temporibus predecessorum regis regum Anglie usque ad tempus comitis supradicti’, Close Rolls of the Reign of Henry III: 1237-1242 (London, 1911), p. 326; see also Curia Regis Rolls of the Reign of Henry III, ed. L. C. Hector, vol. xvi (1237-42) (London, 1979), p. 376; Rees, ‘The Mediaeval Lordship of Brecon’, p. 191.

25 Matthew Paris, Chronica Majora, vol. iv, p. 385; Rees, p. 191. 26 For a similar argument about a different text see J. Spence, ‘Genealogies of Noble Families in Anglo-Norman’, in

R. L. Radulesccu and E. D. Kennedy (eds), Broken Lines: Genealogical Literature in Late-Medieval Britain and France (Turnhout, 2008), p. 68; this text has some similarities with the Cotton Roll, but is not an exact match. It is also in Anglo-Norman rather than Latin. For an edition of the text see D. Tyson, ‘A Medieval Genealogy of the Lords of Brecknock’, Nottingham Medieval Studies, xlviii (2004), pp. 1-14; see also National Archives E164/1; for Monroe’s hypothesis about the circumstances of production see Monroe, ‘Thirteenth’, p. 232.

27 Rees, pp. 189-90; Brut Y Tywysogyon or The Chronicle of the Princes: Peniarth MS. 20 version, ed. and trans. T. Jones (Cardiff, 1952), p. 104.

28 Banks, ‘Cartularium Prioratus S. Johannis Evang. De Brecon’, pp. 299-300; Close Rolls of the Reign of Henry III Preserved in the Public Record Office: 1251-1253 (London, 1927), pp. 221-2; Close Rolls of the Reign of Henry III Preserved in the Public Record Office: 1268-1272 (London, 1938), pp. 205-6.

29 Brut Y Tywysogyon, p. 118; Rees, pp. 194, 198-9.30 See M. Clanchy, From Memory to Written Record: England 1066-1307, 2nd edn (Oxford, 1995), pp. 135-44;

Monroe, ‘Thirteenth’, p. 32.31 See Banks, ‘Cartularium Prioratus S. Johannis Evang. De Brecon’.

8

Past, Present and Future for Thirteenth-Century Wales: Two Diagrams in British Library, Cotton Roll XIV.12

eBLJ 2013, Article 13

The Septenarium Pictum

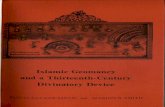

Despite the problems encountered in trying to establish the precise circumstances of production of the roll, the two diagrams with which it begins, one on each side, may offer insights into what the designer was attempting to achieve in his exploration of history. On the front of the roll, above Adam, is the diagram known as the Septenarium Pictum or Wheel of Sevens (fig. 4).32 This diagram also appears on some other rolls with Peter of Poitiers’s genealogical schema, though it was not always included, and the tendency to place it at one end of the roll may have led to other examples being lost. 33 The Cotton Roll version, however, is unusual in several points. Firstly, the image at the centre of the diagram places the object firmly within a monastic milieu, as Christ, seated and holding a book or scroll, is flanked by two tonsured figures in monastic habits. In addition this diagram is one of the more detailed versions to survive, and on the basis of its text may be compared with two early thirteenth-century versions: Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS. Lyell 84 and Harvard, Houghton Library, MS. Typ. 584, both of which have survived as cut down sheets (figs 5-6).34 The circular diagram follows a standard format, being made up of five concentric circles and divided into seven segments, providing five groups of seven terms, which are detailed in circles placed on the concentric bands. A strip runs from the top of the circle to just above Christ’s head and contains details of the contents of the different bands. Thus working outwards from Christ at the heart of the diagram, the innermost band contains the seven beatitudes, which (reading clockwise) are: the kingdom of heaven, possession of the earth, consolation, satisfaction, obtaining of mercy, vision of God, and sonship of God.35 Above these, in the next band, are the virtues. Arranged to correspond with the beatitudes these are: spiritual poverty, meekness, mourning, hunger for justice, mercy, purity of heart, and peace. Some of these qualities have branches coming from them giving further details of what they might involve, thus spiritual poverty is connected to ‘humility of heart’ and ‘renunciation’, which in turn is connected to ‘interior’ and ‘exterior’ which are then linked to ‘all forms of abasement’ and ‘the heart not set upon [things]’, giving the viewer additional material for meditation.36 The next band focuses on how these qualities may be achieved, listing the gifts of the Holy Spirit: fear of the Lord, piety, knowledge, fortitude, counsel, understanding and wisdom. 37 In the fourth band are the petitions of the Lord’s prayer, which reading clockwise occur in reverse, beginning ‘deliver us from evil’ and ending with ‘hallowed be thy name’. Again these petitions are further expanded upon in branches stemming from them. All these elements are given a particular application in the final tier, as the diagram explains that ‘man is sick, God is the doctor, the vices are the illnesses’.38 In the final band are seven vices, identified both

32 See M. Evans, ‘The Geometry of the Mind’, Architectural Association Quarterly, xii (1980), pp. 32-55.33 For other thirteenth-century examples see: Harvard University, Houghton Library, MS. Typ. 584; London,

British Library, Add. MS 60628A; Royal MS. 14. B. IX; Lyon, Bibliothèque Municipale, MS. 863; Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS. Lat. Th. B. I and Lat. Th. C. 2; MS. Lyell 84; Naples, Bibl. Naz., MS. VIII C 3; New York, Morgan Library, MS. M. 628; Philadelphia, Free Library Lewis E 249; the diagram was probably originally included in Liverpool, Walker Art Gallery, Mayer 12017, which now only retains the associated texts on the Pater Noster; see also A. Katzenellenbogen, Allegories of the Virtues and Vices in Medieval Art: From Early Christian Times to the Thirteenth Century (New York, 1964), pp. 63-4, n. 2; Evans, ‘The Geometry of the Mind’, p. 29; N. J. Morgan, Early Gothic Manuscripts (II) (London, 1988), pp. 180-1.

34 The approximate dimensions for the three sheets are as follows: Houghton Library, MS. Typ. 584, 44 x 31 cm; Bodleian Library, MS. Lyell 84, 55.3 x 43 cm; British Library, Cotton Roll XIV.12, 45.6 x 34.2 cm. The image in the centre of the Bodleian diagram is a later addition.

35 See also Matthew 5.36 ‘Paupertas spiritus, humilitas cordis, abdicacio, interiorium, exteriorium, omni moda abiectio, cordis non

apposicio’.37 See Isaiah 11:2.38 ‘Est homo egrotus deus medicus vicia languores’.

9

Past, Present and Future for Thirteenth-Century Wales: Two Diagrams in British Library, Cotton Roll XIV.12

eBLJ 2013, Article 13

Fig. 4. The Septenarium Pictum. BL, Cotton Roll XIV.12.

10

Past, Present and Future for Thirteenth-Century Wales: Two Diagrams in British Library, Cotton Roll XIV.12

eBLJ 2013, Article 13

Fig. 5. The Septenarium Pictum. Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS. Lyell 84. With permission.

11

Past, Present and Future for Thirteenth-Century Wales: Two Diagrams in British Library, Cotton Roll XIV.12

eBLJ 2013, Article 13

Fig. 6. The Septenarium Pictum. Harvard University, Houghton Library, MS. Typ. 584. With permission.

12

Past, Present and Future for Thirteenth-Century Wales: Two Diagrams in British Library, Cotton Roll XIV.12

eBLJ 2013, Article 13

through labels and in personifications engaged in the particular vice, which are linked to a collection of associated errors named in smaller circles. Reading clockwise, vainglory sits on a throne wearing a crown and carrying a sword, anger is represented by a fighting couple, envy sits supporting his head in one hand, sloth is asleep in bed, avarice pours coins from a bag on to a board, gluttony is feasting, and lust is represented by a couple embracing. In this imagery the Cotton Roll differs slightly from the Bodleian and Houghton Library versions, which show individual female personifications of the vices (figs 5-6). However, in all these versions, the viewer is presented with pictures of sins to be combated through prayer and godly behaviour, with the ultimate end of the rewards promised in the beatitudes.

The visual prominence given to the vices is partly enabled by the available space at the edge of the circle and can thus be misleading, particularly in versions of the diagram where Christ is not represented in the centre. The vices, however, are not the focus of the diagram, as the text within the diagram concentrates on the means of combating these evils. The spiritual battle is made particularly clear in the Cotton Roll, where at the top of the diagram a knight in armour receives a scroll from a female figure, together with the gifts of the Spirit in the form of tongues of fire from seven doves that appear from heaven, a detail I have not found on another roll, although some other versions of the diagram include a standing figure of pride at this point, as, for example, in the Bodleian version (fig. 5). The iconography of the knight is reminiscent of a well-known, but nonetheless remarkable, image of the Christian’s battle against vice in British Library, Harley MS. 3244, ff. 27v-28 where it accompanies a collection of texts including William Peraldus’s Summa de Vitiis (fig. 7).39 Here a knight on horseback, accompanied by the seven doves and the virtues associated with the beatitudes, battles against vices, this time represented as demons.40 The imagery at the centre of the diagram on the roll also finds a parallel in the preceding image in the volume, on f. 27, where a Dominican friar kneels before an enthroned Christ, whose right arm is raised in blessing (fig. 8). Despite the general stylistic and iconographic parallels, however, more careful examination reveals a different categorization of the errors associated with the vices in the Harley manuscript image (which Michael Evans demonstrated is not directly related to the Summa text), whilst the religious on the roll do not appear to be Dominicans.41 Although the two manuscripts make use of similar ideas, therefore, the connection between them is thus unlikely to be a direct one, although it is worth noting that the Dominicans established a Friary in Brecon before 1269.42 Peraldus’s work may be dated c. 1236, providing a terminus post quem for the British Library volume, although on the basis of some of the other imagery Evans considered it to have been made rather later, c. 1255.43

The battle against vice is given a further level of significance in the diagram on the Cotton Roll through the use of a border that provides both a visual and temporal frame for the image.44 As Evans observed, the frame is not a complete rectangle, but rather marks out a pathway around the diagram, beginning on upper right, slightly inset.45 The upper part of the roll is damaged, but the lower part of an image can be made out in the opening roundel, which appears to show Adam and Eve being driven out of the Garden of Eden. Between this roundel and that on the upper left are the names of the Sundays from Septuagesima (the ninth Sunday before Easter) to Easter. In other versions of this diagram, this line is also

39 See M. Evans, ‘An Illustrated Fragment of Peraldus’s Summa of Vice: Harleian MS. 3244’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, xlv (1982), pp. 14-68; P. Binski, Becket’s Crown: Art and Imagination in Gothic England 1170-1300 (New Haven & London, 2004), pp. 182-3.

40 Evans, ‘The Geometry of the Mind’, p. 29.41 Evans, op. cit., p. 40.42 R. C. Easterling, ‘The Friars in Wales’, Archaeologia Cambrensis, xiv (1914), pp. 337-8. 43 Evans, ‘The Geometry of the Mind’, pp. 14, 41; N. Morgan, Early Gothic Manuscripts (I) 1190-1250 (London,

1982), pp. 127-8.44 Monroe, ‘Thirteenth’, pp. 130-1.45 Evans, ‘The Geometry of the Mind’, p. 49.

13

Past, Present and Future for Thirteenth-Century Wales: Two Diagrams in British Library, Cotton Roll XIV.12

eBLJ 2013, Article 13

Fig. 7. The Christian knight. BL, Harley MS. 3244, ff. 27v-28.

14

Past, Present and Future for Thirteenth-Century Wales: Two Diagrams in British Library, Cotton Roll XIV.12

eBLJ 2013, Article 13

Fig. 8. Christ and a Dominican friar. BL, Harley MS. 3244, f. 27.

15

Past, Present and Future for Thirteenth-Century Wales: Two Diagrams in British Library, Cotton Roll XIV.12

eBLJ 2013, Article 13

identified as ‘the time of deviation, from Adam to Moses’, and this may have been cut from the top of this roll, which is clearly incomplete. The lower part of a figure (possibly Moses, as in Bodleian MS. Lyell 84) can be made out in the second roundel, and the line from this to the roundel in the lower left corner is labelled ‘the time of revocation, from Moses to Christ’.46 This is accompanied by a list of the four Sundays in Advent. In the lower left roundel is an image of Christ’s Nativity, and this is followed in the lower right corner by an image of the Resurrection. Between the two are listed the feasts of the Nativity, Circumcision, Epiphany and the ninth Sunday before the start of Lent, along with two descriptions of time; ‘the time of reconciliation in regard to the body’ and ‘the time of Christ’s peregrination’.47 Finally the fourth side encompasses the ‘time of reconciliation’, and a section that is now damaged, but which on other rolls reads ‘the time of the peregrination of the church’.48 Below are listed the feasts of the Resurrection, Ascension, Pentecost, Trinity Sunday, and the thirty-three feasts of ‘ordinary time’. These are followed by ‘Antichrist’, ‘forty-five days of penance’ (referring to a period of peace between the coming of the Antichrist and the final judgement), ‘conversion of the remnant’ and ‘Day of Judgement’.49 The roundel at the end of this line is largely lost, but on the basis of other versions of the diagram it probably contained an image of Christ in judgement. Thus the frame brings together the history of the world, past and future, with the annual cycle of the church calendar.

The importance of the temporal framework for the circular diagram is underlined by the text that flanks the Christian knight at the top of the image, versions of which also appear in British Library, Add. MS. 60628A; Royal 14. B. IX; Bodleian Library, MS. Lyell 84; and Houghton Library, MS. Typ. 584. On the left the text begins ‘these four lines, which create the outer square, represent the four times like a thread, from the beginning to the end of the world, during which time vices attack us and we must take up the benefits of virtues and gifts against them’.50 This text is followed, on the right, by a collection of excerpted statements about the Pater Noster. The search for a textual source for the diagram has generally led scholars to Hugh of St Victor’s De Quinque Septenis and De Septem Donis Spiritus Sancti, which present the petitions of the Lord’s Prayer and gifts of the Holy Spirit as medicines with which to counteract the vices.51 As more recent scholarship has observed, however, these texts do not provide all the details found in the diagram.52 A fuller match may be found in the fifth book of Innocent III’s De Sacro Altaris Mysterio or De Missarum Misteriis (chapters 16-28), which also provides part of the text above the circle.53 This offers a commentary on the Lord’s Prayer that connects the vices, petitions, gifts of the Holy Spirit, beatitudes and related virtues, together with the associated elements listed in the diagram. Innocent’s text was probably first written in the 1190s and circulated widely.54 The large number of sources that engage with these ideas indicate that they were very widely discussed, and Innocent’s text may thus not have been the direct source for the diagram, though it does indicate that the ideas were still being explored at the turn of the thirteenth century.

46 ‘Tempus revocationis a Moyse usque ad Christum’.47 ‘Tempus peregrinationis quantum ad Christum; tempus reconciliationis quantum ad membra’.48 ‘Tempus reconciliationis’.49 ‘Antichristus, xlv dies penetentie, conversio reliquiarum, dies judicii’; see R. E. Lerner, ‘Refreshment of the

Saints: The Time After Antichrist as a Station for Earthly Progress in Medieval Thought’, Traditio, xxxii (1976), pp. 97-144.

50 See appendix, below; J. Perarnau i Espelt, ‘Indicacions esparses sobre Lul·lisme a Itàlia abans de 1450’, Arxiu de Textos Catalans Antics, v (1986), p. 297, n. 8.

51 Hugues de Saint-Victor, Six Opuscules spirituels, ed. & trans. R. Baron (Paris, 1969); Evans, ‘The Geometry of the Mind’.

52 Monroe, ‘Thirteenth’, p. 129; Morgan, Early Gothic Manuscripts (II), pp. 180-1.53 Innocent III, ‘De Sacro Altaris Mysterio’, Patrologia Latina, ccxvii, cols 773-915.54 W. Imkamp, Das Kirchenbild Innocenz’ III (Stuttgart, 1983), pp. 46-53; J. C. Moore, Pope Innocent III

(1160/61-1216): To Root Up and to Plant (Leiden and Boston, 2003), pp. 20-2.

16

Past, Present and Future for Thirteenth-Century Wales: Two Diagrams in British Library, Cotton Roll XIV.12

eBLJ 2013, Article 13

The association between the diagram and these textual sources raises the possibility that the schema was designed for a practical use, providing a relatively straightforward theological framework that might be a foundation for sermons.55 The virtues and vices and the Pater Noster seem to have been popular material for preaching.56 For example, in England in the early thirteenth century the material on the roll finds parallels with Robert Grosseteste’s popular Templum Dei.57 One of the tables in this work presents seven groups of seven qualities, including vices, the petitions of the Lord’s Prayer, behaviour (mores), character (habitus), virtues, gifts of the Holy Spirit and beatitudes. The description of this table declares, ‘in the table is the whole care of pastoral office’ and likens the gifts of the Spirit and the beatitudes to medicinal treatments.58 However, unlike easily portable codices, it is difficult to see how the Cotton Roll might have been used in practice. Some scholars have assumed that rolls had a practical application in a classroom, as visual aids for students, and some have suggested that such rolls might have been displayed on walls, though in most cases this seems unlikely.59 The size of the Cotton Roll, together with the fact that it has content on both sides, which is arranged along the narrower dimension of the roll, makes it extremely difficult to use, and certainly unsuitable for wall display. Moreover, the theological content of the opening diagram and the Biblical genealogy is balanced by the more terrestrial concerns of the later section with its interest in the families who controlled much of the Welsh Marches. It may thus have been designed as a means of understanding the history that was about to unfurl before the reader as part of an ongoing battle against evil that began with Adam, but was to be understood as being of contemporary relevance, and in which the user could thus play a part. In particular it provided a reminder of God’s control over both the beginning and end of time, with the associated final judgement.

The imagery on the dorse

The imagery at the top of the back of the roll also reveals an interest in both temporal structures and contemporary life. At the top of the roll is another circular diagram that continues the theme of the battle between virtue and vice (fig. 9).60 At the heart of the circle is another knight, this time accompanied by an angel, who holds a scroll which reads ‘be strong in the Lord’.61 Around this are eight armed female figures, identified by labels as the

55 Morgan, Early Gothic Manuscripts (II), p. 128; M. W. Bloomfield, B.-G. Guyot, D. R. Howard and T. B. Kabealo, Incipits of Latin Works on the Virtues and Vices, 1100-1500 AD: Including a Section of Incipits of Works on the Pater Noster (Cambridge, MA, 1979); M. Carruthers, The Book of Memory: A Study of Memory in Medieval Culture, 2nd edn (Cambridge, 2008), p. 328.

56 D. D’Avray, The Preaching of the Friars: Sermons Diffused from Paris Before 1300 (Oxford, 1985), pp. 76-7; R. Newhauser, ‘Preaching the “Contrary Virtues”’, Mediaeval Studies, lxx (2008), pp. 135-62; R. Tuve, Allegorical Imagery: Some Mediaeval Books and Their Posterity (Princeton, 1966), p. 87; see also Evans, ‘The Geometry of the Mind’, p. 53, n. 85.

57 Robert Grosseteste, Templum Dei edited from MS. 27 of Emmanuel College Cambridge, ed. J. Goering and F. A. C. Mantello (Toronto, 1984).

58 ‘In hac tabula est tota cura officii pastoralis, ut obstetricante manu per vinum et oleum contra vulnera et infirmitates educatur coluber tortuosus et preambulis preparacionibus detur medicina purgativa inducens sanitatem, et inductam conservet quousque pro infirmitatibus dotes et pro vulneribus beatitudines inducantur’, Grosseteste, p. 38.

59 H. E. Hilpert, ‘Geistliche Bildung und Laienbildung: zur Überlieferung der Schulschrift Compendium historiae in genealogia Christi (Compendium veteris testamenti) des Petrus von Poitiers (d. 1205) in England’, Journal of Medieval History, xi (1985), pp. 315-32; C. Klapisch-Zuber, L’Ombre des ancêtres: Essai sur l’imaginaire médiéval de la parenté (Paris, 2000), p. 139; Monroe, ‘Thirteenth’, pp. 39-40.

60 Monroe, ‘Thirteenth’, p. 518.61 ‘Fortare in Domino’.

17

Past, Present and Future for Thirteenth-Century Wales: Two Diagrams in British Library, Cotton Roll XIV.12

eBLJ 2013, Article 13

Fig. 9. Battle of virtues and vices. BL, Cotton Roll XIV.12, dorse.

18

Past, Present and Future for Thirteenth-Century Wales: Two Diagrams in British Library, Cotton Roll XIV.12

eBLJ 2013, Article 13

virtues of charity, chastity, sobriety, patience, humility, voluntary poverty, fear of God and spiritual joy.62 The figures carry spears and scrolls that identify corresponding vices as their targets.63 They are separated by lines of text that run to the edge of the diagram. These are paths of salvation, each containing the name of a virtue (with one exception, where a space has been left) followed by a quotation from the Bible.64 Beneath these virtues is an army of female figures, identified as elements of the virtues above. These women are in combat with a collection of demons labelled as sins, in a variation on the common imagery of a battle between the virtues and vices. In the outermost circle are eight roundels featuring more demons, this time representing the overarching sins to which the errors associated with the other demons belong.65 Between these roundels, at the end of the lines representing the paths of salvation, angels and demons compete for naked souls. However in every case the soul turns its face towards the angel. As with the diagram on the other side, therefore, this schema seems to associate man’s behaviour on earth with future judgement.

At the same time, the circular diagram on the dorse of the roll is part of a much larger design (fig. 10). This imagery stretches across the first two membranes of the roll with a section missing from the middle where the join has been repaired. The theme of the vices continues in the body of a monstrous creature, the tail of which stretches up the right hand side of the roll to meet the circular schema. Within the monster are personifications of the seven vices (one of which is now lost in the repair), each surrounded by the names of associated sins. An inscription in the creature’s neck identifies it as Charrum or Charon. Isidore of Seville noted that Charon was the Greek name for Pluto or ‘Orcus, receiver of the dead’.66 Further names are given in the creature’s head, where the ‘head of the body of sin’ is called Behemoth and Leviathan, whilst a note by the tail declares that this part of the body has the power to bind and sever.67 The text in the creature’s throat details the evils that pervade this body, declaring ‘In his neck is strength / The origin of sin is pleasure as a result of suggestion / The derivation of sin is consent to preceding pleasure / The body of sin is the collection of evils’.68 On the creature’s head is a crown, with a note identifying it as king of the sons of pride, a title associated with Lucifer (fig. 11).69 In its face are two winged demons (identified as being of different degrees), associating the creature with hell, and with the fall of the angels.70 The origin of human sin is represented in the creature’s mouth, where Eve hands an apple to Adam. Beneath the apple is an angel, possibly representing the expulsion from Eden. However the angel holds a sceptre rather than the customary sword (as shown on the front of the roll, fig. 1), and might thus also represent Lucifer and the fall of the angels. This point in the image serves as a basis for a loose temporal framework. To the right of the open jaw is the word Genesis, surrounded by an image of creation; at the bottom is earth, above which is written ‘water’ and ‘fish’, and over these are ‘air’, ‘birds’ and ‘stars’. To the right of and slightly above Eve is an image of Cain, and moving up the roll Moses

62 ‘Caritas, castitas, sobrietas, patiencia, humilitas, paupertas voluntaria, timor Dei, spirituale gaudium’.63 See also Katzenellenbogen, pp. 1-13. 64 Monroe, ‘Thirteenth’, p. 518.65 The connections being made between virtues and vices are complex, but the vices corresponding to the virtues

seem to be as follows: caritas and tristitia, castitas and invidia, sobrietas and luxuria, patiencia and ventris ingluvies, humilitas and ira, paupertas voluntaria and superbia, timor Dei and avaricia, spirituale gaudium and vana gloria.

66 Isidore of Seville, The ‘Etymologies’ of Isidore of Seville, ed. S. A. Barney, W. J. Lewis, J. A. Beach and O. Berghop (Cambridge, 2006), p. 186.

67 ‘Caput corporis peccati; Cauda stringit draco [...] et pungit’.68 ‘Charrum / In collo eius fortitudo / Origo peccati est delectacio proveniens ex suggestione / Derivatio peccati

est concensus delectatione precedenti / Corpus peccati collectio malorum’.69 ‘Rex filiorum superbie’; see Peter Lombard, The Sentences: Book 2: On Creation, trans. G. Silano (Toronto,

2008), p. 24. 70 See Peter Lombard, The Sentences: Book 2, esp. pp. 24-7.

19

Past, Present and Future for Thirteenth-Century Wales: Two Diagrams in British Library, Cotton Roll XIV.12

eBLJ 2013, Article 13

Fig. 10. Start of BL, Cotton Roll XIV.12, dorse.

20

Past, Present and Future for Thirteenth-Century Wales: Two Diagrams in British Library, Cotton Roll XIV.12

eBLJ 2013, Article 13

Fig. 11. Charon’s head. BL, Cotton Roll XIV.12.

Fig. 12. Legal proceedings around a consanquinity table. BL, Cotton Roll XIV.12.

21

Past, Present and Future for Thirteenth-Century Wales: Two Diagrams in British Library, Cotton Roll XIV.12

eBLJ 2013, Article 13

receives the tablets of the law. Above this are tables of affinity and consanguinity flanked by personifications of the virtues, again suggesting a contemporary struggle against vice, though this time in a particular context. Between the two diagrams is written ‘the beginning of the New Testament’, whilst at the top of this section is an image of the Trinity, over which is ‘things to be after the day of judgement’.71 The crown worn by God the Father, in which Christ sits, overlaps the circular diagram above, again suggesting that all the imagery should be read as a unit.

At the heart of the lower part of this remarkable collection of imagery and text are the diagrams of consanguinity and affinity. These charts show the relations one was not allowed to marry, which following the Fourth Lateran Council of 1215 had been reduced to within four generations.72 Packed around the schema are explanatory texts, which provide an indication of how to read the diagrams. The importance of the diagrams to the schema as a whole is reinforced by the first text immediately below the imagery (at the start of the third membrane), which provides instructions how to construct a tree of consanguinity.73 This text and that pertaining to marriage around the diagrams seems to be derived from a popular treatise, Quia tractare intendimus, by Raymón de Penyafort, which Sam Worby considers to have been written about 1235, and which is often found in collections of the Decretals of Gregory IX, sometimes accompanied by decorated schemas showing consanguinity and affinity.74 Marriage ties had implications for inheritance, and thus could have a bearing on a range of legal matters. Whilst a consanguinity table has obvious relevance for a manuscript with a genealogical diagram on the other side, with the figures of Adam and Eve in Charon’s mouth also representing the first marriage, it may also have had a particular relevance for the thirteenth century. In this context it is intriguing to note that Eleanor de Braose and Humphrey de Bohun were related in the fifth degree through their shared great-great-great grandparents Milo and Sybil, a relationship that would have been prohibited before 1215. However the consanguinity tables need not be seen as relating primarily to the affairs of laymen, as clerical marriage continued to be a concern in England and Wales.75 Gerald of Wales, nephew of the more famous author of the same name, who succeeded his uncle as archdeacon of Brecon, a post he held until the late 1240s, acknowledged and made provision for three sons.76

The relationship between the tree of consanguinity and legal matters is made clear in the Cotton Roll in the imagery that surrounds the relationship schemas. Fitted rather awkwardly into the space to the left of the trunk of the consanguinity tree is an image of a seated judge, holding a sword and labelled ‘judex’, who is flanked by figures making gestures suggesting speech, identified as an apparitor (an official who summoned others to appear before a judge), and an actor or prosecutor (fig. 12).77 This figure is tonsured, suggesting that the case is one of canon law. Beneath this, in what appears to be a second scene on a legal theme, what seems to be a female figure, with a covered head, holds forth to a group of onlookers. The figure is labelled postulator or petitioner. On the right of this scene is a strange figure that appears to have two, embracing, bodies meeting in one, male, head. The caption is partially lost, but it appears to read coniug[...]; relating to marriage. The figure may thus represent the idea

71 ‘Initium novi testamenti; Futura post diem Judicii’.72 Constitutiones Concilii quarti Lateranensis una cum Commentariis glossatorum, ed. A. García y García (Vatican

City, 1981), pp. 90-1; J. A. Brundage, Law, Sex, and Christian Society in Medieval Europe (Chicago and London, 1987), p. 356.

73 ‘Arborem consanguinitatis describas hoc modo’.74 S. Worby, Law and Kinship in Thirteenth-Century England (Woodbridge, 2010), pp. 34, 35, 148; Brundage, pp.

401-5.75 See C. N. L. Brooke, ‘Gregorian Reform in Action: Clerical Marriage in England, 1050-1200’, Cambridge

Historical Journal, xii (1956), pp. 1-21.76 J. S. Barrow, ‘Gerald of Wales’s Great Nephews’, Cambridge Medieval Celtic Studies, viii (1984), pp. 101-6. 77 See Isidore of Seville, p. 205.

22

Past, Present and Future for Thirteenth-Century Wales: Two Diagrams in British Library, Cotton Roll XIV.12

eBLJ 2013, Article 13

Fig. 13. The grades of clergy and the Trinity. BL, Cotton Roll XIV.12.

23

Past, Present and Future for Thirteenth-Century Wales: Two Diagrams in British Library, Cotton Roll XIV.12

eBLJ 2013, Article 13

presented in Ephesians 5:23 that ‘the husband is the head of the wife, as Christ is the head of the church’.78 The metaphor about heads continues in the section below, which is less immediately related to marriage. Here a headless figure holds an axe, beneath the statement ‘a servant has no head’.79 The rather alarming image again relates to law, as, in an idea that can be traced to Roman law, a master was held to be the head of his slaves, giving them no legal rights. The image of the slave may be associated with claims to property, as around this figure are images of foliage and a city, labelled as rural and urban property.80 On the opposite side of the tree are two other images dealing with aspects of law. To the right of the trunk two soldiers seize a tonsured figure, labelled as the defendant (reus).81 This may be a reference to the different rules of military law. Below a figure in bed is identified as giving testimony, presumably as the result of an injury, to a group of witnesses, including a legal secretary ([a]manuensio legis). On the right a malefactor is then apprehended by the hair. The figures were drawn in before the tree, though the ones above were designed to fit into a triangular space, and the lines of the tree have been rather awkwardly drawn over them. These images were thus not an afterthought to fill available space. They may have been included to provide an earthly and contemporary parallel to God’s final judgement as depicted above.

Law is also one of the major themes of the section immediately below the consanguinity diagram (fig. 11). Above Adam and Eve is written ‘natural law’, defined by Isidore of Seville as being ‘common to all nations, and, because it exists everywhere by instinct of nature, it is not upheld by any regulation. Such is the union of a man and a woman’.82 Over this is ‘rational creation’, and Isidore also observed that ‘if law amounts to reason, the law will consist of everything that already agrees with reason, provided that it accords with religion, benefits orderly conduct, and promotes welfare’.83 Above the figure of Cain is written ‘customary law’, which Isidore defined as a ‘system of justice established by moral habits, which is taken as law when a law is lacking’.84 Slightly above this, and aligned with Adam and Eve, Moses receives the tablets of the law, watched on the left by a series of heads representing the nations who are associated with another facet of law (ius gentium).85 On either side of this imagery are representations of Sparta (Lacedemonia) and Athens. These cities are explicitly identified with law, as Athens is labelled ‘written law’, whilst Sparta is associated with ‘unwritten law’ and ‘customary law’, elements also defined by Isidore.86 The association of early law with these cities was also made by Augustine, who claimed that Roman law was derived from the laws of Solon of Athens, and that ‘although Lycurgus pretended that he had drawn up laws for the Lacedaemonians by Apollo’s authority, this the Romans wisely refused to believe, and for this reason took nothing from that source’.87 Thus contemporary canon law is presented as being rooted in both Biblical and Roman law.

The imagery above the consanguinity tree also relates to canon law, although it focuses on the ranks of clergy, which are set out in Gratian’s Decretum and its sources, notably in Isidore of Seville’s Etymologies, and Peter Lombard’s Sentences.88 On the far right is a kneeling figure,

78 See also Isidore of Seville, p. 211.79 ‘Servus non habet caput’.80 ‘Predia rusticana; predia urbana’.81 See Isidore of Seville, p. 365.82 ‘Ius naturale’; Isidore of Seville, p. 117; see also Brundage, p. 348. 83 ‘Rationalis creatura’; Isidore of Seville, p. 73.84 ‘Ius consuetum’; Isidore of Seville, pp. 73, 117.85 ‘Ius gentium’; Isidore of Seville, p. 118; Corpus Iuris Canonici, ed. E. Friedberg (Leipzig, 1879), col. 3.86 ‘Ius non scriptum / consuetudo / mos’; Isidore of Seville, p. 117.87 Saint Augustine, The City of God Against the Pagans, trans. G. E. McCracken, vol. i (Cambridge MA &

London, 1981) p. 195; see also Isidore of Seville, p. 117.88 P. Landau, ‘Gratian and the Decretum Gratiani’, in W. Hartmann & K. Pennington (eds.), The History of

Medieval Canon Law in the Classical Period, 1140-1234: From Gratian to the Decretals of Pope Gregory IX (Washington, 2008), p. 28; see also J. Barrow, ‘Grades of Ordination and Clerical Careers c. 900-c. 1200’, Anglo-Norman Studies, xxx, ed. C. P. Lewis (Woodbridge, 2008), pp. 41-61; Peter Lombard, The Sentences: Book 4 on the Doctrine of Signs, trans. G. Silano (Toronto, 2010), pp. 138-150.

24

Past, Present and Future for Thirteenth-Century Wales: Two Diagrams in British Library, Cotton Roll XIV.12

eBLJ 2013, Article 13

carrying a scourge and holding a door, apparently desiring entry to the church (fig. 13). Beyond the door is a scene of baptism, the symbolic entrance to the Christian faith. To the right of this scene and facing it are representatives of different types of clergy, who are labelled, and carry appropriate attributes.89 The slope of the tree is here used to suggest a hierarchy. At the base of the slope is an untonsured figure, whose caption is now difficult to read, but who seems to be a layman (perhaps a conversus), in contrast to the tonsured clerics behind.90 Above him is the hostiarius or porter, who carries a key in order, as Isidore observed, to ‘receive the faithful and reject the unfaithful’.91 Behind him is the lector or reader, who is followed by an exorcist, shown in the act of driving a spirit out of a man’s mouth. At this point the damage to the roll makes the next figure and his attribute unclear, however the figure seems to be holding a long thin object that broadens at the base, and might be an acolyte carrying a candle.92 The images may have continued in a second tier immediately above, as the remains of a roundel for one of the vices suggests that approximately 45 millimetres is missing at this point. Peter Lombard was amongst those who identified seven ecclesiastical orders (including subdeacons, deacons and priests) to match ‘the sevenfold grace of the Holy Spirit’.93 On the surviving adjoining section are three bishops (labelled tres episcopi) together with Peter and Paul, who are placed opposite a representation of a figure wearing a papal tiara, placed beneath the inscription ‘head of the church militant’.94 The papal tiara is similar to that worn by God the Father, which is labelled imperium pontificale, underlining the pope’s role as God’s representative on Earth. Behind the unnamed pope are three cardinals, and beneath this group are two figures who seem to be in armour, which may be another reference to the church militant. On the far right, at the bottom of the slope is a priest with an excommunicated man, who is being grasped by a devil, providing a contrast to the scene of the penitent being received into the church on the far left.

The porter’s key is an echo of the key that is at the heart of this section of the image, which, unfortunately, falls partially in the lost area of the roll. The key is aligned with the centre of the consanguinity table, but seems to be controlled by the Holy Spirit, as the base of the key is arranged around the head of the dove, which proceeds from the mouth of God the Father and holds scales representing the day of judgement in its beak. Both Peter and the unnamed pope extend their hands to it, further identifying it as the key of heaven, as referred to in Matthew 16:19, where Christ declared to Peter, ‘I will give to thee the keys of the kingdom of heaven. And whatever thou shalt bind upon earth, it shall be bound also in heaven: and whatsoever thou shalt loose upon earth, it shall be loosed also in heaven’. In the Sentences Peter Lombard discussed these keys at some length in connection with priests’ abilities to remit sins, concluding ‘God alone remits and retains sins, and yet he confers upon the Church the power of binding and loosing. But he binds and looses in one way, and the Church in another. For he remits sins by himself alone in such a way that he both cleanses the soul from inward stain and absolves it from the debt of eternal death. [...] He did not grant this power to priests. And yet he gave to them the power of binding and loosing, that is, of showing that men are bound or loosed. [...] although one is unbound before God, yet he is not treated as unbound in the face of the Church, except by the judgement of the priest’.95 The link between God’s judgement and that of the church is stressed in the image, where beneath the depiction of the scales is written ‘the judgement of the church is the judgement of God, who is the judge’. 96 The space around the dove, which appears to be God’s shoulders, is labelled Syon, further suggesting a link between

89 See, for example, Peter Lombard, The Sentences: Book 4, pp. 140-46.90 Isidore of Seville, p. 170.91 Isidore of Seville, p. 172.92 See Corpus Iuris Canonici, ch. 16; Isidore of Seville, p. 172. 93 Peter Lombard, The Sentences: Book 4, p. 138; Barrow, pp. 41-61.94 ‘Capud ecclesie militantis’. 95 Peter Lombard, The Sentences: Book 4, p. 110.96 ‘Judicium ecclesie est judicium dei qui est judex’.

25

Past, Present and Future for Thirteenth-Century Wales: Two Diagrams in British Library, Cotton Roll XIV.12

eBLJ 2013, Article 13

celestial and terrestrial law and judgement, as in addition to being a place closely identified with God and his people, the writer of the book of Revelation declared, ‘I beheld, and lo a lamb stood upon mount Sion, and with him an hundred forty-four thousand, having his name, and the name of his Father, written on their foreheads’. 97 Isidore of Seville offered another view of Zion, identifying it with the church and ‘its present-day wandering [...], because from the imposed distance of this wandering it may “watch for” (speculari) the promise of celestial things, and for that reason it takes the name “Zion” (Sion), that is, watching (speculatio)’.98 The Bible identified the church as the body of Christ, and the position of the label ‘Syon’ thus seems to resonate with these ideas, being identified with the execution of God’s law on earth.99

The complexity of the imagery leaves us with the two related questions of what the roll was for and who made it. Beginning with the question of the maker of the roll, the evidence, in particular the inclusion of the monks in the Septenarium Pictum diagram, suggests a monastic creator. Although the large number of medieval texts cited in this article might suggest that the author had access to a substantial library or advanced educational training, most of the information presented on the roll represents widely known legal and theological ideas. It seems likely that Battle had a better library and resources than Brecon, and Monroe thus suggested that the roll may have been made at Battle Abbey for Brecon.100 Details of the members of Brecon Priory in the first half of the thirteenth century are, in general, sketchy, though the community may have numbered no more than nine in this period. 101 However, its best known member, Gerald of Wales, left an account of his quarrel with his successor in the post of Archdeacon of Brecon and nephew, also called Gerald of Wales, which sheds light on what at least two members of the community knew, and the sort of training available to young men in the area in the early thirteenth century.102 From Gerald the elder’s Speculum Duorum we learn that he was disappointed in and felt cheated by the nephew whom he considered he had treated like a son. Whilst he repeatedly claimed that Gerald junior did not make the most of the opportunities available to him, he nevertheless provided some evidence of the educational training available. A comparison with the achievements of one John Blund, who spoke perfect French despite never having been to Paris, may suggest that Gerald the younger did not follow in his uncle’s footsteps in spending time in the schools of that city, where the latter had studied the arts and canon law.103 Nevertheless Gerald senior claimed that his nephew studied at Beverley with ‘Master David the Welshman, your kinsman’, and at Hereford, as well as accompanying him to Lincoln for his studies.104 Gerald senior, conceivably with his nephew, seems to have encountered Robert Grosseteste at Lincoln (where Robert would later become bishop), and Gerald recommended him to the bishop of Hereford.105 This is not to suggest that either Gerald was responsible for the production of the Cotton Roll; nevertheless it seems possible that it could have been made by an enterprising monk at Brecon Priory as an attempt to make sense of contemporary events using the standard theological and legal thinking of the time.

97 Revelation 14:1.98 Isidore of Seville, p. 173.99 See Colossians 1:24.100 Monroe, ‘Thirteenth’, p. 519; N. Ker, Medieval Libraries of Great Britain, 2nd edn (London, 1964), pp. 7-8, 12;

R. Sharpe et al. (eds.), English Benedictine Libraries: The Shorter Catalogues (London, 1996).101 F. G. Cowley, The Monastic Order in South Wales, 1066-1349 (Cardiff, 1977), p. 42; Banks, ‘Cartularium Prioratus

S. Johannis Evang. De Brecon’, Archaeologia Cambrensis, xiv (1883), p. 298.102 Giraldus Cambrensis, Speculum Duorum or A Mirror of Two Men, ed. Y. Lefèvre and R. B. C. Huygens, trans.

B. Dawson (Cardiff, 1974). 103 Giraldus Cambrensis, p. 57.104 Giraldus Cambrensis, pp. 31, 43, 70, 157, 247; see also J. Moreton, ‘Before Grosseteste: Roger of Hereford and Calendar

Reform in Eleventh- and Twelfth-Century England’, Isis, lxxxvi (1995), pp. 562-86.105 Giraldi Cambrensis Opera, vol. i, ed. J. S. Brewer (London, 1861), p. 249; R. W. Southern, ‘Grosseteste, Robert (c.1170-

1253)’, Dictionary of National Biography, www.oxforddnb.com [accessed September 2012].

26

Past, Present and Future for Thirteenth-Century Wales: Two Diagrams in British Library, Cotton Roll XIV.12

eBLJ 2013, Article 13

The Cotton Roll could have helped a monk in Brecon make sense of his world. It provided an account of those of significance in the government of the world, both the founders of his house and the political and ecclesiastical authorities. In addition it offered him an account of humanity’s place in a theological framework. Caught between the death of Christ and the final judgement, it illustrated the vices with which man must do battle. At the same time it equipped a monk in the mid-thirteenth century with a mass of well-established ideas that might be useful in preaching and interacting with the wider community. The choice of the roll format was probably inspired by Peter of Poitiers’s genealogy, but may also have served to underline the official nature of the material recorded. Yet the fact that the roll was probably executed by one monk, and seems to be incomplete, may suggest that it was an individual’s labour of love, which, perhaps because of the turbulent politics of Wales in the thirteenth century, none of his brothers saw fit to complete. It thus remains a rich, but tantalizingly elusive, witness to thirteenth-century ideas about history.

Appendix

Linee iste quattuor exteriores que faciunt quadrata quattuor nobis tempora representant que fluunt ab initio mundi usque ad finem in quibus hec vitia nos impugnant et beneficia virtutum et donorum contra hec expugnanda nobis necessaria sunt. Primum fuit tempus deviationis ab Adam usque ad Moysen quomodo peccavit Adam in paradiso et Caim in homicidio et Lamech in bigamia et illi qui submersi sunt in diluvio. De quo apostolus ait: Regnavit mors ab Adam usque Moysen quia peccatum tunc vix cognoscebatur [Romans 5:14]. Secundum fuit tempus revocationis a Moyse usque ad Christum. Per legem enim et prophetas cognita sunt magis peccata et veriti homines ceperunt retrahi timore potius quam amore. Tertium fuit tempus reconciliationis a nativitate scilicet Christi usque ad missionem Spiritus Sancti. Per hec enim omnia que gessit Christus reconciliatus est mundus. Deus enim erat in eo mundum sibi reconcilians. De hoc tempore dicit apostolus: Ecce nunc tempus acceptabile [id est] tempus gratie [2 Corinthians 6:2]. Quartum tempus est peregrinationis a missione Spiritus Sancti usque ad diem iudicii quo adhuc peregrinatur ecclesia in lucta et pugna. Quia etsi soluta sit culpa restat adhuc pena, quod significatum est in Absalon qui postquam reconciliatus est patri suo per Ioab mansit in Ierusalem biennio antequam videret faciem patris. Ista quattuor tempora ita se sequntur per ordinem, ut hic annumerata sunt et annotata in figura. Sed in representacione ecclesie non ita. A prima enim dominica adventus usque ad nativitatem recolit ecclesia tempus revocationis. A nativitate usque ad Septuagesimam tempus reconciliationis est quantum ad membra, que per hoc reconciliata sunt. Quod etiam tempus peregrinationis est quantum ad Christum qui inter nos peregrinatus est dum natus circumcisus baptizatus est. A septuagesima tempus deviationis representatur usque ad passionem domini per septem dominicas que respiciunt septem etates mundi unde cuiuslibet dominicarum illarum officium pertinet ad opera alicuius illarum septem etatum. Quia in omnibus etatibus inveniuntur aliqui deviantes preterquam in septima unde illa dominica plena est leticia qua cantatur letare Ierusalem. Due dominice de passione ad tempus reconciliationis pertinent et Christi peregrinationem et peccatorum aggravacionem in hominibus quia officium illud mixtum est magis tamen fit commemoratio perfidie iudaici populi et peccatorum humani generis pro quibus passus est dominus unde officium illud dicitur pertinere ad tempus deviacionis. Tempus resurrectionis ascensionis Spiritus sancti missionis tamen ad reconciliationem nostram pertinet non ad peregrinationem Christi tunc enim iam cum deo patre erat. Dominice viginti tres que sunt ab octavo die pentecostes usque ad adventum tempus designant peregrinationis ecclesie modo usque ad diem judicii et ita peregrinatio bipartita est in capite primo que tamen ad reconciliationem nostram spectat et in corpore secundo. In cuius peregrinationis fine veniet antichristus. Post cuius regnum xlv dies dabuntur ad penitentiam. In quibus reliquie Israel convertentur. Postea veniet Christus ad iudicium et tunc videbit eum omnis caro et qui eum pupugerunt [Revelation 1:7].