Pan Kachin Development Society Karen environmental and Social ...

Transcript of Pan Kachin Development Society Karen environmental and Social ...

Pan Kachin Development Society

Karen environmental and Social Action Network

Edited and introduced bySearchweb

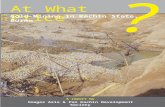

Destruction and Degradation of the Burmese Frontier Forests

Colofon

Destruction and Degradation of the Burmese Frontier Forests:

Listening to the People's Voices

By Pan Kachin Development Society (PKDS)And Karen Environmental and Social Action Network (KESAN)

Acknowledgements: Tropical Rainforest Programme of NC-IUCN for funding theresearch, Novib for financing the report, Global Witness, Images Asia E-Desk,ERI, Terre des Hommes Germany, and all the people from the local communitieswho helped with the research.

Design:Continental Drift

Edited and introduced by:Search web

Printed by Kaboem Amsterdam, 2004

Table of contentsChapter 1 Introduction

Chapter 2 The politics of Burma and deforestationa. Politics of Burma 5

b. Logging and civil war 8

Chapter 3 Kachin State by PKDSIntroduction— 10

a. Logging business 11

b. Who benefits from the logging---14

Chapter 4 Karen State by KESANIntroduction

a. Doo The Htoo District

b. Mu Traw District (Pa Pun)

c. Toungoo District

- 16

- 18

-24

-32

Chapter 5 Conclusions and recommendations by KESAN 40

Maps 42

Abbreviations 44

3

5

10

16

Chapter 1

IntroductionIn 1998, the World Resources Institute (WRI) inWashington published a highly alarming report onthe state of the Burmese frontier forests. "Burmaholds more than half of mainland Southeast Asia'sclosed forests - forests that have caused the countryto be called 'the last frontier of biodiversity inAsia'", began the report. It concluded that this lastfrontier of biodiversity was seriously endangered.The findings of the report included, amongst others:

* Burma's neighbours, having lost virtuallyall of their own original forest cover, reliedincreasingly on timber from Burma.

* The rate of deforestation had more thandoubled since the present military regimehad come to power in 1988.

* Wasteful and destructive logging by theregime, some of the ethnic minority groups,and foreign companies along the borderswith China and Thailand, had resulted inmassive soil erosion, sedimentation of riv-ers, increased flooding, and acute dry sea-son water shortages.

W RI's information on the state ofBurma's frontier forests, specifi-cally on forest cover and the rateof deforestation in Kachin and

Shan State (on the border with China), relied heavilyon satellite data. What actually happened on theground within these frontier states, or around forestsin Burma as a whole, remained to a large degree un-known territory for the observer. Vast areas of theethnic states in Burma remain closed to foreignersby the Burmese military. This was the result of theongoing and disastrous political and ethnic conflictsand power struggles that have made the military re-gime of Burma, the State Peace Development Coun-cil (SPDC and before: SLORC), a pariah in the in-ternational community. As described in the nextchapter, the problem of logging and deforestationtakes place in the context of the complex politicaland military situation in Burma. The frontier re-gions, where the hotspots of biodiversity are locatedare controlled and contested by SPDC Army units,and a bewildering number of ethnic liberationgroups and armies, some of whom have, and some

of whom have not signed cease-fires with the re-gime. This situation has made it a point of vehementdiscussion whether international environmental anddevelopment organizations should and could work inthe country to support more sustainable developmentpolicies. A major international conservation organi-zation, the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) ispresently working in SPDC-controlled areas in col-laboration with the Burmese Forestry Department toestablish conservation areas. For most of the interna-tional organizations, working with the regime is stillout of the question as long as democracy in Burma isrepressed.

This dilemma has led a number of organizationsover the past four years to develop alternative ap-proaches. At the end of 2003, one of these organiza-tions, the London-based NGO Global Witness pub-lished a report with the findings of then- 'undercover'research in Burma and the frontier areas. The reportgives a poignant and once again disturbing analysisof Burmese forests as a 'conflict resource'. The ex-ceptionally valuable and high grade Burmese tim-bers are resources that are extracted commerciallyfor large short-term profits, by institutions and indi-viduals ruthlessly exploiting the conflict situation.

Logging trucks on the road to China

Destruction and Degradation of the Burmese Frontier Forests

The chief beneficiaries are Burmese officials andChinese companies. Meanwhile the Burmese andespecially ethnic populations are deprived of manyof their chief assets for sustaining livelihoods andfor future development. Many ethnic organisationsalso seem caught in the need for short-term incomegeneration and play along in the squandering of theforests. The end result? More and more environ-mental destruction and a continuation of the trendsoutlined in the 1998 WRI report.

The devastation, however, is not only environmental.Deforestation has its consequences for forests andfor forest dwellers, including indigenous people andother forest users. It is on these forest dwellers that,in conjunction with the end of the political repres-sion, the coming of democracy, and the empower-ment of local communities, the development of fu-ture sustainable environmental policies should bebased. But the lack of information on the forestdwellers and on the impacts of deforestation on theirsocial and economic life is, if anything, even greaterthan the lack of information about the deforestationitself.To address this information gap, representatives oftwo ethnic groups, from Kachin and Karen State,undertook the first research project, supported bygrants from the Tropical Rainforest Programme ofthe Dutch Committee for the IUCN (NC-IUCN).The results of this research by the Pan Kachin De-velopment Society (PKDS), and the Karen Environ-mental and Social Action Network (KESAN) in theirhome states, are presented in this report.

The reports of PKDS and KESAN are the first at-tempts to uncover the social impacts of deforestationand to relate them to envi-ronmental degradation. Theresearch was undertaken ina very difficult and danger-ous political climate. As aresult, the researchers wereforced to keep a low profile.The outcome of the re-search is therefore oftenuneven and remains impres-sionistic. These impressionsare, however, sufficient tomake us realize that whathappens at this moment inthe frontier forests ofBurma has its implicationsnot only on the terrain ofnature conservation, butalso on the terrain of thesocial and economic devel-

opment of local communities. With the logging andthe deforestation a whole new economic and socialreality develops, in which most people, having losttheir traditional livelihood, are turned into casuallabourers and a cheap labour force for local poten-tates and entrepreneurs. The loss of community for-ests is another outcome of the global dispossessionthat opens up even marginal territories to the dictatesof the market economy. With this dispossession notonly the environment, but also traditional culturesand social organizations disappear.

What this report, especially the contribution of KE-SAN, makes clear, is the positive role that the tradi-tional cultures and traditional environmental policiescan play in the formulation and implementation ofsustainable forestry policies in Burma. Support forgrass-root initiatives and for awareness-raisingwithin local communities should be combined withthe political campaigns for democracy in Burma,and with environmental campaigns to stop trade inunsustainable timber, to create an alternative for thepresent state of degradation and corruption. The fu-ture will show whether there is still time left, beforeone of the last hotspots of biodiversity in SoutheastAsia is sacrificed to human greed and narrow-mindedness.

References:

J. Brunner. 1998. Logging Burma's Frontier Forests:Resources and the Regime.World Resources Institute, Washington.

Global Witness. 2003. A Conflict of Interests: TheUncertain Future of Burma's ForestsGlobal Witness, London.

NDA-K controlled town on China border

Chapter 2

The Politics ofBurma and

DeforestationBurma, or Myanmar as it was renamed by the mili-tary government in 1989, is the largest country onthe mainland of South-East Asia, covering an area of678,580 square kilometres. It is bordered by India,Bangladesh and the Bay of Bengal to the west, byChina in the north-east, Laos and Thailand in theeast, and by the Andaman Sea to the south.Despite the fact that Burma is rich in resources, thecountry is very poor. Decades of destruction througharmed conflict, political repression, human rightsabuses, and government mismanagement have cre-ated great hardships for the peoples of Burma; espe-cially in ethnic minority areas. It has left the countryin a deep economic, social, and humanitarian crisis.Burma, once one of the wealthiest, developed andmodern nations of Southeast Asia, had to apply tothe UN for Least Developed Country (LDC) statusin 1987.

C limatic conditions differ from region toregion, and there is a wide variety ofecosystems. These include the snow-capped mountains of northern Kachin

State, the rugged bare hills of the Wa region, theShan highland plateau, the rice growing areas in theirrigated dry zone of the central plains, mangroveforests in the Irrawaddy Delta, and the rainforestsand tropical islands of southern Burma. Burma isrich in minerals and natural resources, is one of themost fertile countries of Asia, and has wide biodi-versity. Kachin State in particular has been listed asone of the worlds remaining 'biodiversity hot-spots' (Moncreif and Myat, 2002).Burma is inhabited by a wide range of different eth-nic groups, including Burman, Mon, Karen, Karenni,Shan, Wa, Kachin, Chin and Rakhine. Ethnic mi-norities make up over 30% of the population, whichstands at some 50 million in 2003. Reliable statisticson population and ethnic groups are not available;the last comprehensive population census dates backto 1931.

Since the constitution of 1974, the country is admin-istratively divided into 7 divisions and 7 ethnic mi-nority states; Yangon, Irrawaddy, Magwe, Tenas-serim, Mandalay, Pegu, and Sagaing Divisions, andRakhine, Chin, Kachin, Shan, Karenni, Karen, andMon States. These ethnic minority states make up55% of the land area, but represent only a few of thelargest ethnic groups.The majority of the Burman Buddhist populationlives in the central plains and valleys, where theypractise wet-rice paddy cultivation. These includethe river basins of the Irrawaddy. Sittaung, Salween,and Chindwin rivers. In contrast, the ethnic minoritygroups live in the hills and mountains that surroundthe central lowlands, where they have developedtheir own distinctive cultures and traditions, and

Destruction and Degradation of the Burmese Frontier Forests

practise upland rice cultivation and rotational agri-cultural fanning systems. Before and during Britishcolonization, these ethnic minorities were largelyruled by their local leaders, and maintained a relativeindependence from the successive traditional king-doms in the plains.

N egotiations for independence fromBritish rule started after World War II,The Burman nationalists, led by AungSan, wanted independence from the

British as soon as possible. Ethnic minority leaderson the other hand, were concerned about the right ofself-determination, and wanted to establish a systemthat would give them equal rights and protect themagainst domination by the Burman majority. Someethnic groups wanted independent states for them-selves. In 1947, the Panglong agreement was signedbetween Aung San and Shan, Kachin and Chin rep-resentatives, which formed the basis for a future Un-ion of Burma. However, this agreement was incon-sistent about the rights of different ethnic minoritygroups, and many ethnic groups were not repre-sented.All these factors ultimately led to civil war soon af-ter the declaration of independence in January 1948,with a communist insurrection and army mutinies.The Karen National Union (KNU), created in 1947out of Karen nationalist organisations dating back tocolonial time, took up arms in January 1949.Other ethnic groups came up in revolt at the sametime. These included Karenni and Mon nationalists,who later formed the Karenni National ProgressiveParty (KNPP), and the New Mon State Party(NMSP) respectively. A Pao group in Shan State and

Loading wood on truck

6

Rakhine and Muslim nationalists in Arakan(Rakhine) State also took up arms.In 1962, General Ne Win took power from the U Nugovernment in a military coup, and created a one-party state led by the Burma Socialist ProgrammeParty (BSPP). The constitution was abrogated, allopposition put behind bars, and people's attempts toorganise themselves were severely repressed. Alllarge industries and business enterprises were na-tionalised under the 'Burmese Way to Socialism',the BSPP's official doctrine, Burma was to becomeself-sufficient, and the generals isolated the countryfrom the outside world.By this time, the civil war had already spread to Ka-chin and Shan State, where the Kachin Independ-ence Organization (KIO) and the Shan State Army(SSA) had started armed uprisings. Both of themwere able to expand quickly, fuelled by the growingdissatisfaction among the Kachin and Shan popula-tion over the unequal position of ethnic minorities inthe Union of Burma.By the mid-1970s, the Burmese army had succeededin pushing back the armed opposition groups fromthe plains and the Irrawaddy Delta and the Pegu Yo-mas into the hills and mountains of the border re-gions, using the infamous Tour-Cuts' campaign.This campaign is aimed at cutting the four links be-tween the insurgents and the civilian population:food, finance, intelligence and recruits. The 'FourCuts' strategy is directly targeted at the civilianpopulation, which has been subject to harsh treat-ment and forced relocations to special sites nearBurma Army camps.

After Ne Win came to power, relations with Chinadeteriorated. These came to an absolute low after

anti-Chinese riots in 1967,which China suspected wereinstigated or at least stimu-lated by the BSPP. As a re-sult, China changed its ini-tial careful policy towardsthe Communist Party ofBurma (CPB), which hadjust lost its main base areasin central Burma, into anall-out support.The CPB launched a suc-cessful invasion from Chi-nese territory into northernShan State and quickly be-came the strongest insurgentarmy in Burma (Lintner.1990). It forged a number ofalliances with ethnic minor-ity armed groups, including

Destruction and Degradation of the Burmese Frontier Forests

Wa and Kokang troops.These were given arms andammunition in return foraccepting the political lead-ership of the CPB. This pol-icy was later applied to otherregions, and caused a num-ber of debilitating splits inethnic minority organisa-tions.In 1976, the National De-mocratic Front (NDF) wasformed; a new alliance con-sisting solely of ethnic mi-nority organizations, includ-ing the KNU, NMSP,KNPP, K1O, SSA and someother smaller groups. At-tempts to form a united frontbetween the CPB and theNDF failed. Until its collapse in 1989, the CPB alli-ance rivaled the anti-communist and pro-westernNDF alliance in strength. While the CPB and its al-lies relied on support from China, most of the NDFmembers financed their organizations by setting uptollgates along the Thai border. In Shan State, manyinsurgent armies were financed by opium taxation.

The BSPP's economic policy was a complete fail-ure. Consumer goods were only available on theblack market. Smuggling of these goods became amajor source of income for ethnic insurgent armiesbased along the Thai border. Burma was facing ahuge economic crisis, and in 1987 had to apply forLCD status. The BSPP decision to devaluate a largeamount of banknotes, officially to curb black markettrade, further led to great resentment among thepopulation, In 1988, a massive movement for de-mocracy and human rights was initiated by studentsand other urban activists. They staged demonstra-tions and strikes in the cities and larger towns ofcentral Burma, demanding an end to military ruleand a multi-party system. On 8 August 1988 ('8-8-88'), millions of protesters over the whole countrytook to the streets. The army responded with bruteforce, killing thousands of unarmed protesters. InSeptember 1988, the military set up a new rulingbody, the State Law and Order Restoration Council(SLORC). After years of self-imposed isolation, theSLORC (that most observers claim to have beenonly a new name for the same old group of powerholders), initiated a new 'open door policy', andsought to attract foreign investment and acquire for-eign exchange. For elections in May 1990, the armyallowed the formation of new political parties, thefirst time since it took over state power in 1962. The

Logging Papun area

opposition National League for Democracy (NLD),led by Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, the daughter of inde-pendence hero Aung San, won a landslide victory.The military backed National Unity Party won only10 seats, then the Shan Nationalities League for De-mocracy (23 seats) and the Arakan League for De-mocracy (11 seats).The SLORC refused to hand over power and by1992, the majority of political parties had beenbanned. Instead, the SLORC set up a National Con-vention that started to work on a new constitution inearly 1993, under close supervision of the military.In 1995, the NLD decided to withdraw from theConvention in protest against restrictions. In an attempt tobreak the deadlock, the NLD, in cooperation with anumber of ethnic minority politicians, set up theCommittee Representing the People's Parliament(CRPP) in 1998. The military immediately re-sponded by arresting many NLD and CRPP mem-bers.

A fter the crackdown of 1988, thousandsof Burman activists fled to the junglebases of ethnic armed oppositiongroups in the border area, mostly to

member groups of the NDF. Here student activistsformed the All Burma Students' Democratic Front tolaunch an armed struggle against the military gov-ernment. This led to the formation of new alliances.In 1990, the Democratic Alliance of Burma (DAB)was formed, a new umbrella organisation of ethnicminority organisations and Burman oppositiongroups. Two years later, in 1992, the National Coun-cil of the Union of Burma (NCUB) was created and set

Destruction and Degradation of the Burmese Frontier Forests

up at the KNU headquarters in Manerplaw, near theThai border. The NCUB consisted of ethnic nationalityorganisations plus members of political parties, and MPs-

elect (mainly NLD) who had escaped a new wave ofarrests after the elections of 1990.

In 1989, Wa and Kokang troops mutinied against theBurma CPB leadership. They formed new organisa-tions based along ethnic lines and included theUWSA in Wa-inhabited regions of Shan State, theMNDAA in Kokang in northeast Shan State, theNDAA in eastern Shan State, and the NDA-K in Ka-chin State. The mutiny spread quickly, and SLORCresponded by offering cease-fire agreements to thesenew groups. The CPB insurgency was effectivelyended.

Old DKBA logging camp (Sin Swein area)

The NDF tried to woo the mutineers into their campbut failed. Instead, the military pressure on otherethnic armed groups in the northern Shan State in-creased. The Shan State Army (in northern ShanState), an NDF member, signed a cease-fire soonafterwards. Other important NDF members, includ-ing the Pao National Organisation (PNO) (nearTaunggyi in Shan State) and the Palaung State Lib-eration Party (PSLP) (near Hsipaw in Shan State), fol-lowed two years later in 1991.The Burmese Army launched new offensives againstthe remaining NDF members. During 1991-92,heavy fighting took place in the mountains aroundManerplaw, the KNU headquarters, but against theexpectation of many observers, the KNU managedto hold its ground.The KIO now proposed to start joint negotiationswith the SLORC on behalf of the NDF. After failing

to convince the NDF, the KIO signed a sepa-

rate cease-fire in February 1994. While the KIO ar-gued that it was better to make a cease-fire first, andthen find a political solution, others, including theKNU, wanted to have a political solution first beforesinging a cease-fire. The KIO was subsequentlyejected from the NDF and the DAB. In 1995, twoother NDF members, the NMSP and the KNPP, alsosigned a cease-fire, although the latter broke downafter a few months.Pressure on the KNU increased after the breakawayof groups of dissatisfied Buddhist soldiers, whoformed the Democratic Karen Buddhist Army(DKBA). The SLORC responded quickly and of-fered the DKBA aid and territory. This ultimatelyled to the fall of the KNU's headquarters in Maner-

plaw in early 1995.Cease-fire talks be-tween the SLORC andthe K N U during1996-97 failed to pro-duce results. The KNUmaintained that it can-not sign a cease-firewithout a lasting po-litical solution. Duringthe military offensiveof the Burmese armythat followed immedi-ately after, the KNUlost most of its

remaining territory.It now operates as a

guerrilla army from a

number of small basesalong the Thai border,

with small-scale hit and

run attacks.By the end of 2003, most of the large armed ethnicopposition groups had signed cease-fire agreements,except for the KNU, the KNPP, and the SSA-South.These organisations are all located along the Thaiborder. Smaller Chin, Rakhine, Naga and Muslimgroups remained active on Myanmar's northern bor-ders with Bangladesh and India, In early 2004, theKNU and the SPDC made a temporary verbal cease-fire agreement.

Logging and civil war

During the decades of civil war in Burma, all con-flict parties have relied on the extraction of naturalresources, mainly by logging and mining, to financetheir armies. The scale of logging increased dramati-cally after SLORC came to power in 1988. The most

8

Destruction and Degradation of the Burmese Frontier Forests

serious damage has been done in the ethnic minorityareas along the borders with Thailand and China.These areas previously contained untouched forestreserves with various types of hardwood and tropicalrainforests, and included many important watershedareas. The increased fighting along the Thai borderin the late 1980s and early 1990s coincided with un-sustainable and clear-cut logging practices by Thailogging companies,In November 1988, the Thai government announceda total logging ban in Thailand after logging-relatedmudslides caused the death of 350 civilians. In De-cember 1988, soon after the formation of theSLORC and the bloodbath of August and September1988, Thai Army Commander Chaovalit visitedBurma and returned with lucrative logging and fish-ing concessions. As a result of this trip, a large num-ber of Thai logging companies, most of them wellconnected to high-ranking Thai military officers orpowerful Thai politicians were granted logging con-cessions by the SLORC. Many of these concessionswere located in areas controlled by armed ethnic op-position groups, including the KNU, NMSP, KNPP,and MTA.

From the SLORC's perspective, these log-ging concessions were pan of a largerscheme to defeat the ethnic insurgencies. In1991, U Nyunt Shwe, then Burmese Am-

bassador to Thailand, said: "We are selling [the log-ging concessions] to get foreign exchange. No onecan deny that countries need foreign exchange. Hadthe deal not been sealed before the logging ban [inThailand] then there would be political problems inThailand. Therefore, politically you [Thailand] gain.Economically we [SLORC] gain, and politically andeconomically the insurgents lost." (Kramer, 1994)The sale of logging concessions in US dollarsbrought in much-needed foreign exchange. Annualincome from the sale of these logging concessionsmight have been US $112 million a year. In the1990s, the total average annual timber revenue wasUS $200 million and was the largest single source offoreign exchange (Smith, 1994).Thai logging companies removed forest cover forguerrilla armies, and buil t strategic roads into hith-erto inaccessible terrain. Furthermore, on a numberoccasions the Thai army allowed Burmese troops toattack Karen, Mon and Karenni strongholds frombehind, using That territory. In this way, the Bur-mese army quickly overran a number of bases thathad been impregnable before. These "logging wars'were chaotic in nature and led to many conflicts be-tween logging companies, ethnic minority armies,

and the SLORC, and lasted until the mid-1990s. Bythat time, huge parts of Burma along the Thai borderhad been deforested by Thai companies (Kramer,1994).Logging also increased dramatically in northernShan State and in Kachin State after the cease-fireagreements. Organisations such as the KIO, NDA-Kand the SSA-North, found it increasingly difficult tofinance their organisations, and became reliant onthe sale of natural resources, mainly timber, toChina. They claim to have no other alternative. Afterthe cease-fire, the KIO lost control of the jade minesat Hpa-kant, which up until then was its mainsource of income.The majority of the timber is cut by Chinese compa-nies, who subsequently export the logs across theborder to neighbouring Yunnan Province in China.In recent years, both the KIO and the NDA-K havealso given out logging concessions to foreign com-panies, mainly Chinese but, reportedly, also Malay-sian and Singaporean. These concessions were ex-changed in return for road building projects in Ka-chin State, which is very underdeveloped and haspoor infrastructure. Representatives of the KIO andthe NDA-K say that since the government has madeno efforts to develop Kachin State, they have to do itthemselves. The only way to finance this, they ar-gue, is by selling logging concessions (Moncreifand Myat, 2001).

References:

Kramer, T. 1994. "Thai Foreign Policy TowardBurma 1987-1993". MA thesis, University of Am-sterdam, Amsterdam.

Lintner, B.1990. "The Rise and Fall of the Com-munist Party of Burma (CPB)". Cornell Univer-sity Press, New York.

Moncreif, J., and H. Myat. October-November2001. "The War on Kachin Forests."The Irrawaddy 9 (8): 14-17.

Myanmar Forestry Department. 1991. Popula-tion statistics for May 1991.

Smith, M. 1999. "Burma: Insurgency and thePolitics of Ethnicity", Zed Books, London.

Smith, M. 1994. "Paradise Lost? The Suppressionof Environmental Rights and Freedom of Expres-sion in Burma. London", Article 19:13.

Chapter 3

KACHIN STATEby PKDS

An introduction

Kachin State is a dark green temple of closed for-ests, full of precious natural resources; notably jadeand gold. The subject of many poems and songs, itsbeauties are far beyond those expressions, It is saidthat the forests of Burma are among the most re-sourceful in the world; inside Burma, the forests ofour Kachinland are the richest of all.Since the days of our forefathers many have giventheir lives, talents; all they had, to protect this re-sourceful land. Kachins lived without greed, earningtheir Livelihood and producing sufficient food usingtraditional methods of agricultural cultivation. Everyyear they grew crops for an annual harvest, and aftereach year they moved to another field (taungya) toplant new crops, returning once in ten years to eachfield.In forty years of civil war, many of our Kachin peo-ple; men, women, and children, were only able tosurvive in me midst of war because of the forest. AllKachin know in themselves that me forest is themother which offers shelter and food for me Kachinpeople. It has long been the safe operating area andhome of the Kachin liberation fighters of the KIOand the NDA-K. Because the Burmese enemy wasnot familiar with the Kachin forest, the Kachin de-fenders could for a long time compete with the Bur-mese troops, despite the Kachin resistance forceshaving less weapons and smaller numbers.

The Kachin practice traditional medicine using re-sources from the forests and mountains of Ka-chinland. There are many different herbs with me-dicinal value in the leaves, sterns, flowers, bark, ber-ries, nuts, roots and fruits in the plants. Bird nestsand other animal products, even some animal drop-pings, are used as medicine. The forest is the medi-cine store of the Kachin. Traditional Kachin herbalmedicine can cure diseases and injuries as severe asbroken bones and deadly wounds often better thanmodem medicine. Presently, this rich source ofherbal medicine is in great danger of being wipedout. as some of the most useful species are becomingvery difficult to find. Some of the best herbal medi-cine plants which are a world heritage can only befound in the very deep forest areas.

K achin life is heavily dependant on theforest. Some people are taking advan-tage of the forests to get rich throughthe logging, mining and smuggling of

natural resources like rattan cane, jade and wildlifeproducts. Jade and gold mining, logging, overhun-ting and road building are especially threatening theKachin heritage. Many Kachin are left wanderingand rootless, having lost their livelihood resourcesalong with the forests that have been destroyed be-fore their eyes. The forest, rivers and land where ourancestors have lived for generations are being sold

An interview with a local in Laiza

"There were many kinds of wild animals. Tigers, antelopes, deers, bears, fowls, birds, monkeys, and more wereabundant around here. Now they have gone. People are setting the forest on fire in the summer. Because ofthe fires the wild animals cannot stay in the forest and insects die. Medicinal shrubs are also wiped out.""People say the logging business is for the development of the country. We can see no other development thanthe increasing number of good houses built for officers. People are still in the same situation as before. Deforesta-tion is done by the people in authority. When we talk about deforestation and reforestation to them, they tell us tobring dollars. The KIO is planting trees, but only teak to be cut in the future.Real reforestation means to grow a variety of trees that were wiped out. Religious leaders are preaching this in thechurches. They should preach more about this. Everyone should grow at least one tree and look after it. Environ-mental conservation should be taught in the schools. Only then will the new generation know how to conserve theforest and have a healthy environment.Hpung Ki Company is the biggest company from China engaged in the logging. At first it was supposed to builda hydropower electricity plant at Mali Hka. After eight years of extraction there is still no sign of the plant.People cannot do logging business. All permits are issued to officers only."

10

Destruction and Degradation of the Burmese Frontier Forests

off to the advantage of foreign and local business-men and the national and state power holders. Busi-nessmen from both inside and outside Kachin Statehunt for resources like wolves in sheepskin, playinga game that destroys the land. Moreover, they createnew hardships for the local people - leaving themwithout land and resources, unemployed and disad-vantaged

T he problems of logging and mining areclosely related. Until the mid-1990s,gold mining was done only on a smallscale, using manpower, with bamboo-

made sluices and banana leaves and trunks. Up tothat time the only logging done was for the construc-tion of local buildings. Today, all kinds of powerfulmachinery are used with catastrophic environmentalconsequences. Mining concessions and logging con-tracts have been issued across Kachinland to compa-nies from different regions.The situation is not only the result of profit motivesand bad administration. It is also a consequence ofthe political game playing of the SPDC. Stimulatingmigration to Kachinland in relation to 'economic de-velopment' is a way to break up Kachin social andethnic structures. Destruction of the natural re-sources of the forest, sources of food, and other ba-sic necessities threatens to extinguish Kachin culture

Because of this, we will discuss the following ques-tions:

1 What problems are caused by the logging?2 Who benefits from the logging?

The report is based mostly on interviews and otherfield research done mostly between April 2002 andJuly 2003. It looks at the strategies behind the log-ging, about the concessions, and about the endan-gered areas. It talks about the victims of the conces-sions, about exploitation of local people, and aboutthe growing power of businessmen.

Logging business

At one time the forest was central to the life of theKachin people. After harvesting their crops, villag-ers collected different types of mushrooms, andhunted birds and wild animals in the forest. In someplaces, villagers collected many kinds of forest prod-ucts and vegetables and brought them to the marketto sell. With the money they earned they were able

Logging news from Talawgyiand Sinbo (June-July 2003)

There are two districts under the K1O administration inthe eastern part of Irrawaddy (Mali Hka) River, namelyMan Maw (Bhamo) District and Sadung (Sadon) Dis-trict. Logging business began in 1985, on a small scalein these two districts. Large-scale and intensive loggingbusiness started in 1994, extracting hundreds of thou-sands of tons per year. From 1990-1999, people fromKachinland (Kachin and Shan) were given permits forlogging. The KIO did not allow the Chinese companiesto log. Since 2000, logging permits have been issued to Chi-nese merchants from China and the local people are notallowed to log anymore. All the forests in Sinbo and Ta-law Gyi area were given in concessions to the Chinese.

From 1985-1990, local people engaged in the loggingbusiness. Tax for a logging permit was paid to the KIOonly. From 1994-2000, loggers had to also pay SPDCsoldiers 1000-2000 Kyat per truck-load of logs apartfrom the permit tax. Since 2000, loggers have to paySPDC soldiers at 200,000 Kyat per truck. The KIO hasalso increased the permit tax.The biggest logging tycoons are: Lau Ying (Chinesefrom China), Leng Wun (Chinese from Myanmar), YupZau Hkawng (Jade Land Company - Kachin), and theboss of Hung Ki Company (from China).From 1985-1990, about 10,000 tons of logs were ex-tracted per year from Sinbo and Talawgyi forests. Dur-ing 1991-1996, the extraction increased to many tens ofthousands of tons per year. In 2002, the extraction wasabout 100,000 tons. Logs from Sadung District, BhamoDistrict and the KfO General Headquarters area wereextracted at the rate of 500.000-600,000 tons a year dur-ing 1999-2002.In 2003, the extraction became even more intensive.One Chinese company extracted 2000 logs in 6 months.In June 2003 alone, about 40 to 50 thousand logs werepiling up in Talawgyi and Sinbo forest (at the time ofthis survey). This is estimated to add up to many hun-dreds of thousands of tons over the logging season.Logging concessions were given for October 2002 toJune 2003. The KIO issued a statement that loggingconcessions would be stopped in the year 2003-2004,but some KIO officers illicitly allowed a few loggers towork in return for bribes,

11

Destruction and Degradation of the Burmese Frontier Forests

to buy basic kitchen materials. However, with com-mercial logging, there have been big environmentalchanges, including loss of wild food and acute watershortages, forcing the villagers to turn their back onthe old way of life and join the logging business.In 1994, after the ceasefire the serious logging be-gan, and after only three to four years it had ex-panded to every comer of the land, although in someareas it is smaller scale and hard to document.The majority of the logging concessions now areheld by Chinese foreign businessmen and people inauthority.

A1Logging companies andconcessions

Today the word 'development' is very popular inBurma but in actual practice nothing positive hap-pens, nothing changes to make conditions better forthe Kachin and other ethnic societies. The nationalarmies, the KIO and NDA-Kare aware of the necessity forrapid development in Kachinsociety before outsiders havebuilt too strong an economicposition that disadvantages lo-cal people. They want to set uptheir own development projectsin Kachin State. But, the armieslack the skills and money torun these projects. The imperialjade from the mining town ofHpakant, the main source ofwealth for the KIO and Kachinsociety, is now under control ofthe Burmese government.Opium production, a former Logging trucks at checkpointsource of financing, is internationally prohibited andhas been seriously cut back by the KIO which wantsinternational support and credibility. To supporttheir own development projects the KIO and NDA-K have turned toward the sale of the forests. Bigscale logging started in the KIO area, after the cease-fire agreement in 1994, and in the NDA-K area in1996,Almost all the biggest logging companies are fromChina, which itself has a ban of logging to protect itsown forests. Some well-known holders of loggingconcessions in Kachinland include the followinglauban (an honorific title for boss or tycoon): CingShin (a company from Ten Chong), Cu Hi Jshau,Leng Wun, Hkang Lung (from Yin Jiang), Fan DuShau (Yang Yin), Pong Han Chin, Lag Yin, ShingLeng Woon (from Loije) and Lau Fu.

There are different reasons given by the authoritiesfor the selling of concessions such as the building ofroads and hydropower plants. As one example, theJadeland Company was engaged to build a road be-tween Bhamo - Myitkyina - Sumprabum. In winningthe bid to build the road they were given a loggingconcession one mile wide on each side of the roadbeing constructed.In 2001, the KIO hired the Hung Ki Company tobuild the Mali hydropower station. In return theJahta area was given as a logging concession to theHung Ki Company. Now the concession has beenextended to two Chinese companies, including theHug Ki and Hung Hta companies. The KIO leadershave ordered local people not to do any logging inthis area.Sometimes villagers are persuaded by the business-men to ask permission for logging. For example in1996, the villagers of Jaumau in the NDA-K areawere persuaded by a Chinese company to ask theNDA-K leader for permission to log in their forest.In return, the company would build a school, hospi-

tal and church in the village. The Chinese business-man also offered to build a road and to carry all thelogs. In the end, however, the concession went toNDA-K officers and the village chief who privatelysold to the Chinese and pocketed the profits; whilethe villagers were left without any benefits.

Logging practice

When a logging concession is given to a Chinesecompany, Chinese workers move into the forest areafor a period of months. They bring their own rice,but for their curry they usually rely on forest prod-ucts and wildlife. They exhaust the forest with theirhunting. When the logging process begins, the Chi-

12

Destruction and Degradation of the Burmese Frontier Forests

L

nese first build a road for their trucks. Then theystart cutting the trees into eight foot iong logs (thesize in which they can be carried loaded sideways onthe trucks) with their chainsaws.Where two or three Kachins have to work all daywith their handsaws to cut one big tree, the Chinesewith their chainsaws can speedily clear the forest.When the workers have to move the logs fromplaces where the trucks can't come, they either carrythem themselves to the trucks, or use elephants whenavailable. The trucks carry the logs day and nightinto China.

In Sinboo, Ta Law Gyi and Shwe Gu areas, localpeople are allowed to sell teak. These people cut theteak with handsaws and sell to Kachin businessmen.But since the Kachin businessmen don't have muchcapital and can't buy many logs cut by the villagersthey started taking loans from Chinese businessmen,buying more logs and therefore making more profit-able business.

Loggers bring the logs to the Irrawaddy riversideon bullock carts from the deep forest. Where it istoo difficult for both trucks and bullock carts, thelogs are cut smaller and carried by the workers

themselves. By river, the logs are brought to theNam San Yang area. Bullock carts are used again totake the illegal logs to where trucks can approach.

After that, trucks carry the logs into China via Lizatown.

There are numerous toll gates on the main roadsmost people use, and also on the separate, secret log-ging roads in Kachin State. The majority of them arecontrolled by different SPDC army and military in-telligence units, police, forestry department and cus-toms. There are less KIO and NDA-K checkpoints.As well as Laiza there are a number of other bordercrossing points where the timber is taken across toChina: the Pangwa gate (check-point), Kambaitigate, Hpimaw gate, Sa Ji gate, Sampai gate, LrangFang, Htaw Lang, Shi Chyang, Pa Wa Hku. La Ka-ing gate, Loi Ying Hai gate (Mai Ja Yang), and viathe Hka Shang road and Lai Ying road (Mai Ja Yangand Loije). It is most likely that there are other bor-der gates where logs are brought to China that areunknown and until now inaccessible to our research-ers, such as in the N'Mai Hku area on the border inthe north of the KIO and NDA-K controlled territo-ries.

Khindit area

Khindit consists of three small villages, Hkindit,Bawmling and Bumring Zup around the town of MaiJa Yang located on the Chinese border. There areabout 20 households with a total population of 100people. Approximately one third of the householdscultivate wet fields and approximately two-thirds de-pend on dry field cultivation. A few people havehorses, mules and water buffaloes. The entire villagewas burnt down by the military in 1962 and has sincebeen re-built In 1999, the village leaders granted alogging and charcoal extraction concession for theirforest in return for electricity.

Key points:(1) Average costs of electricity are 9 Yuan per week

per household (higher than on the Chinese side ofthe border). Average expenses on kerosene were 4Yuan per week before the installation of electric-ity.

(2) Voltage is always lower than the standard,(3) Electric lamp-posts are only on the main streets.(4) The villagers have still not been informed about

the terms of the concession agreement.(5) Young people and women feel that there is too

much deforestation but cannot say anything to thevillage leaders.

(6) The women have no voice in the village admini-stration. A woman leader is chosen by the villageleaders, not elected by the women. Women andyoung people hope that the village wilt progressbetter if their voice is heard. They wish to partici-pate in reforestation for future generations.

(7) There are no plans for forest conservation or refor-estation.

(8) The concession was granted for three years, but nowritten agreement was signed. This was four yearsago, but logging and charcoal extraction is stillgoing on.

(9) The community forest is within a radius of 1 milearound the vitlage. Apart from the community for-est, the concessionaires continue to cut trees fromthe main forest. At present, the deforested area isalready about 10 miles deep into the main forest.

(10) The villagers grow fruit trees in the deforestedarea for subsistence, but not on a commercialscale. There is now a plan to grow bamboo andpomelloes. The seedlings will be bought from theChinese factory, but on condition that the productsmust be sold to the factory at the price fixed by thelatter.

(11) Meteorological changes have been noticed since2003. Streams are drying up in the summer andthe climate is hotter.

13

Destruction and Degradation of the Burmese Frontier Forests

Dum Bau and Prang Ngawng Villages

(1) In these villages controlled by the KIO, a log-ging concession and electricity supply agree-ments have been signed with Chinese compa-nies. The forest concession is four square kilo-meters. Logging activities started on November24, 2002, three days after the concession wasissued. At first, only large trees were logged.Now trees as thin as a Pepsi bottle are alsologged for charcoal.

(2) There are 24 households and 117 persons inDum Bau Village. Among them 20 percent areyoung people; mostly students. Most have toleave school because they cannot afford thecosts. The villagers cultivate paddy-fields. Somepeople do not own but rent their land. All house-holds have small gardens to grow vegetables.People also collect vegetables and mushroomsfrom the forests and sell them in the market.There are many kinds of bamboo (ora, mai seng,u law, mai hka, mai hpyu, mai dading) in the for-ests. The shoots of many species are edible.There are many kinds of wild animals, but peo-ple seldom hunt them.

(3) Dum Bau village can be reached after passing aKIA logging check point. There is a timber fac-tory situated in a long and narrow valley by thevillage. There are no carpenters or skilled per-sons to manage business in the villages, thereforethe villages cannot start their own sawmill. Thissituation compelled them to sell forest land to aChinese company in exchange for electricity.

(4) One high-ranking KIA officer owns a large fishpond. There is a hydro-electric generator operat-ing just to supply the fish pond and the farm.

(5) Prang Ngawng village is adjacent to Dum BauVillage. Villagers get electricity from China viaMai Ja Yang and Loije. Villagers pay for theelectricity and the Chinese government mam-tains the supply. The villagers feel that the elec-tric power is over-priced. There is no meter box,

(6) There is enough water and suitable elevation tobuild hydro-electric generators to supply elec-tricity to both Dum Bau and Prang Ngawng vil-lages. However since the local Kachins lack skillin the operation and maintenance of the genera-tors, they chose the alternative of buying elec-tricity from China.

(7) At the time of research (April 2003), woodenposts for electric cables were erected by the Chi-nese company. Villagers proposed to provide theposts, hut the Chinese company did not agreeand will charge for the posts at a higher price.

Social problems in loggingareas

Villagers are often unaware about the problems fromlogging because of a lack of education. The word'development' is attractive to them. Many business-men make use of this, and promise to build schools,hospitals, and churches to get their cooperation. An-other method for enticing villagers to give up theirforest is the promise of electricity for lighting.Again, the result is deforestation, leading to: notenough clean water, water shortages for farming,scarcity of firewood and of trees and bamboo used inhouse construction, and increasingly irreversible en-vironmental changes.Deforestation affects not only the forest, but also thesocial structure of Kachin life, Kachin used to live incollective ways, supporting each other. They did notneed much money to travel since the structure ofsocial relations extended throughout the villages.Any two Kachins were always in a kind of sharingfamily relationship with each other, considering eve-ryone else cousin or brother, aunt or uncle. Thisbeautiful and valuable social structure is now disap-pearing as a consequence of mining and logging.The state of mind, manner, and behaviour haschanged among the young Kachins. Kachin cultureis being further eroded because of the immigrationof thousands of Chinese workers, many of whomentice and marry Kachin girls, often met in Chinesekaraoke bars where the girls work as waitresses.

Who benefits from the logging?

Chinese and Kachin business

Chinese businessmen clearly benefit the most fromthe logging. They are present in all aspects of thebusiness. Chinese workers use chainsaws which arenot available to the Kachins. Kachins are not em-ployed for loading the trucks. The workers are paidpiece-wages. For instance, in Sampai area a busi-nessman called Wu Leng pays workers 25-30 Yuanfor each ton of logs cut, and Y 35-40 for one loadedtruck. Kachins "benefit" from the logging onlythrough the KlO's sale of concessions and the col-lection of taxes at the tollgates and through moneymade by the local people who are involved in cuttingand destroying their own forests. Chinese business-

14

Destruction and Degradation of the Burmese Frontier Forests

Kachin State

men make their biggest profits by processing thelogs in sawmills and timber factories near the borderregion, and exporting the products.Some Kachin businessmen join in logging conces-sions, but since they borrow their investment capitalfrom Chinese companies, they have to sell them thetimber for the price the companies offer. Many Ka-chin businessmen have been arrested for not havingenough money to bribe Burmese army posts.

SPDC, KIO, and NDA-K

In the eyes of many, the KIO and the NDA-K are theorganisations responsible for the excessive and non-sustainable logging in Kachin State. In actual prac-tice however, the major part of income from the log-ging goes to the SPDC. The SPDC really controls

most activities in KachinState, and if they wanted tostop it there would be littleor no logging.In one of our interviews,six timberworkers at Sam-pai-Jahta said that the log-ging was only possiblethrough bribery of the Bur-mese army posts. If onedoesn't pay, they can bearrested and jailed for log-ging, as has happened tosome Chinese businessmenwith insufficient funds forbribing the SPDC army.Another example of thiswas the Lin Fung Com-pany, managed by YangHkyi Seng, and logging in

Gang Dau Yang in Jahta area and Seng Mai Pa. TheChinese had to give 2 million kyat to a Burmesearmy officer for his "travel allowance".One of the interviewed said: "We have to givemoney to every SPDC army post that demands it.These demands are random. As for the KIO, theyprescribe a limit for taxes at their posts, before thelogs are sent to different parts of China via DumBung, close to the border. The KIO collects Y 150per ton, and Y 500 per truck. One concession fromthe KIO costs Y 3000 (300,000 Kyats), logging be-ing possible between September and April in thefollowing year. However we have to pay a personalbribe of 1-2 million kyat to a senior SPDC officerfor one convoy (or consignment) and then pay sepa-rate bribes to the forestry department, the police sta-tion, and all the army posts around."One logger interviewed in Man Win village saw histrucks loaded with timber confiscated by BurmeseArmy troops in 2001, "1 didn't have enough moneyto bribe them", he reported.

Logging news from Sinlum, Law Mun, Law Dan, Hpakawn (January 2003)

(1) This area has once been very rich in biodiversity. It had thick forests and was rich in flora and fauna. Riv-ers and streams would flow the whole year round. But after the commercial logging started, streams aredrying up in the summer and wild animals have started to disappear.

(2) Logging started in the year 2000. The logging concession is 38 miles wide and tens of thousands of acres.It includes Sinlum, Lum Ja, Munghka and Nmawk areas. In addition, some Chinese companies bribe theSPDC army camps and do logging in their territory too. Logging companies have to pay 3000 Yuan for apermit to the KIO, The KIO tollgate charges Y 500-600 for one truck load.

(3) Most of the logging is done around Sama Bum, Lagyen Bum, Langda Bum ranges, About 30-40 truckloads of about 6 tons each are transported to Dumbung in China per day.

(4) By estimation, about 4000 tons in 2002 and at least 5000-6000 tons in 2003 have been extracted.(5) People are watching with tears, the elimination of big trees that have been growing from the lime of their

forefathers. But nothing can be done; the people with authority and the Chinese merchants benefit.

15

Chapter 4

KAREN STATEby KESAN

Introduction

Karen State, home to what were once lush and richlydiverse forests is in the Southeast of Burma, sharingits eastern border with Thailand and other borderswith Mandalay Division, Shan, Mon, and KarenniStates. There are seven districts in Karen State.Three of the four northern districts: Mu Traw(Papun), Toungoo, and Doo The Htoo (Thaton), arethe areas where research on the forest situation hasbeen conducted, (see MAP on page 42)

N orthern Karen State is comprised ofboth flatlands and mountainous areas.The Karen depend on flat rice paddyagriculture, traditional rotational farm-

ing in the highlands, and integrated orchard farming.These practices are suitable for the use of sustain-able agricultural techniques and have been used formany generations.The research shows that all three districts are facingsimilar situations and problems with respect to thedegradation and destruction of forest resources. Theareas were once rich in biodiversity, but now somespecies have become completely extinct, and manyothers are disappearing at alarming rates.

In Karen State, forests are officially classified in twocategories: reserved and unreserved forest land. Thereserved areas were set up by the British during theircolonial rule and remain under government control.The unreserved areas are supposed to be communityforests belonging to villages. However in mostplaces this is no longer the case and community for-ests are logged by other parties.

Several factors are a hindrance to the practice of tra-ditional agricultural methods and are causing majordepletion of the forests:

1.

Transporting logs by cattle

The war. All conflict parties have relied on theextraction of natural resources to finance theirarmies during the decades of civil war. This hasbeen the primary cause of forest destruction inKaren State. The majority of the villagers in thethree districts face forced relocations by theSPDC and have had to abandon their homes andtraditional lifestyles.They have little choice but either to go to theconcentration camps where they must deal withforced labour, forced demand of food and sup-plies, unofficial taxes, and other human rightsabuses; or to hide in the forests. The influx of

Internally Displaced Peo-ple (IDPs) into the forestshas put a great stress onforest management andconservation. In the forests,the villagers have few op-tions for their survival andmost resort to non-traditional forms of shiftingcultivation. Where in tradi-tional forms forest areasare left to fallow for longerperiods, enabling the soil torecover, non-traditionalforms are non-sustainablemethods of farming thatclear large areas of forestafter inadequate fallowperiods, producing lowyields, and providing little

16

Destruction and Degradation of the Burmese Frontier Forests

food security. This situation has been pushedfurther because of a new SPDC strategy that al-lows the regime to maintain control of loggingthrough local intermediaries, in this way ensur-ing cooperation on both sides of the front linesin Karen State.

2. Closely related to the first point is the impact ofcommercial logging. It has been a commonpractice for many years, with notable accelera-tion in the 1990s. Logging that should be doneonly in the reserved areas that are under govern-ment control is now encroaching and destroyingthe traditional community forests. The KNUalso makes deals with the loggers, and villagershave lost their forest resources from their tradi-tional community forests as well as have re-stricted access to reserved forests, resulting inconflicts with the KNU.

3. Recent migration from the cities to the country-side has had great impact on the local communi-ties. Uncontrollable migrants from the cities col-lect fuel and timber for trade in the city, andclear forest areas for unsustainable vegetablegardens.

4. The routine setting of forest fires by the SPDCarmy to clear hiding areas of the KNU.

5. Charcoal production.6. Land confiscation by the SPDC to set up com-

mercial monoculture plantations, to buildcamps, and to develop infrastructure. Whenfarmers shift from traditional agricultural prac-tices to monoculture, the forest-use systemchanges from common property ownership toindividual ownership; encouraging people toencroach on community forest areas, and caus-ing more damage to already degraded forests.

L ogging has had serious impacts on theKaren people and their traditional waysof life. The villagers rely on the commu-nity forests for timber, and non-timber

forest products (NTFP) such as food, herbal medi-cines, and other plant resources. Women especiallydepend on the forest. They need to collect firewood,wild vegetables and other products daily, but thefogging makes this more and more difficult, increas-ing time spent on travel and resulting in less timeavailable for other daily responsibilities.Diminishing biodiversity threatens the practices oftraditional healers who rely on forest resources. Inaddition, the forests have a very important role inreligious beliefs and practices. When they are de-stroyed, the Karen can no longer practice their tradi-tional beliefs.

Key points:

(1) A new strategy allows the SPDC to main-tain control of logging through local inter-mediaries, ensuring cooperation acrossfrontline conflicts.

(2) There is some conflict between local vil-lagers and the KNU over deforestation andlack of access to the forests.

(3) Deforestation by means of logging, mono-culture and forest fires has led to watershortages, which has affected farming.This has forced people to change their live-lihood from farming to casual labour inlogging, gold mining, on mono-plantationand other temporary jobs

Deforestation has had great ecological impact onwater quality and availability, and on meteorologicalconditions. Farmers who depend on irrigation fromthe rivers are facing the problem of poor soil qualitydue to nutrient-deprived water, with lower yields asconsequence. In the dry season, there is a watershortage, and the rivers are at low levels during therainy season. Integrated orchards and gardens aretraditionally set up along the streams, however withthe changed conditions, the plants cannot surviveand die from lack of water. The quality of the wateris greatly affected by the logging. Elephants and buf-falos are used by loggers to pull the logs along thecourse of the streams (that villagers use for drinkingwater and household needs) and pollute the waterwith earth and dung. Soil erosion on the banks altersthe course of the rivers, and destroys gardens andorchards along the banks. The villagers have noticedan increase in air temperature and the weather can bequite irregular with increased droughts and flooding.These impacts jeopardise food security; farmers canno longer rely on their traditional agricultural prac-tices. The unsustainable logging sets off a downwardecological spiral. Many are forced to abandon theirfarms and become daily labourers and elephant driv-ers for the logging companies, work in gold mining,practice unsustainable non-traditional forms of shift-ing cultivation and commercial mono-plantations, orcultivate temporary vegetable gardens.

Deforestation is not only causing serious ecologi-cal problems, but with the loss of the forestsKaren cultural identity, indigenous knowledge,traditional beliefs and values are disappearing aswell. This is a major concern of all villages visitedin the course of the research.

17

Destruction and Degradation of the Burmese Frontier Forests

Doo The Htoo DistrictDoo The Htoo (in Burmese; Thaton) district is located in the plain areas betweenSittang River in the northwest and Salween River in the east. Most of the land areais flat with some mountains in the far north and slopes on the eastern side of the dis-trict near the Salween River. Many villages and agricultural lands are located alongthe basins of Dontkemi River (Baw Naw Klo in Karen) (Salween's tributary} and itstributaries such as Daw Za Chaung (Ta Uu Klo), Kyakat Chaung (Ter R'weh Klo),and other rivers like Bilin River and Theh Pyu Chaung,At present, accurate data on forests in Doo The Htoo district are not available. Ac-cording to the Myanmar Forestry Department statistics of May 1991, there are twomajor types of forests: Tropical Wet Evergreen; stretching from north-west to southparallel to the coastal line, and Mixed Deciduous Forests spreading out from thenorth towards the east, lying parallel to the tropical wet evergreen and coveringmost of the northern and eastern part of the district.Resarch was conducted in three villages: Taung Lweh (Karen name Ta Uu Kee) inBilin Township, and Kyakat Chaung (Ta R'weh Kee) village and Zee Woun(Saktaraw) village in Doo The Htoo TownshipTotal areas involved: Bilin and Doo The Htoo townships in Eastern Doo The Htoo(2 out of 5 districts)Habitat types: Tropical Wet Evergreen forests (cool and very wet). Mixed Deciduousforest (hotter climate, less rain)Wildife present: wild buffalo, wildpig, 2 monkey species, bear, deer, squirrel, wildchicken and other small bird species

1. True status of the rainforest

The status of the rainforest has significantlychanged over the last thirty years. Around 1970many kinds of tree species were common, such asteak, ironwood, Sgaw, Say Baw, Kyaw Kae, Thay PaHsa, Gaw (species from Dipterocarp family), La Ter(another kind of Dipterocarp), Padaunk, Thay PomuPwa, and Klaw Klay. Different kinds of bamboogrew in the forests, such as Wa Mee, Wa Klay, WaShu and Wa Bway. Another type of bamboo, WaKlu, very suitable for building houses, was plantedby villagers near their communities.According to the villagers in the district, there stilllive rare animals such as the rhinoceros, tigers, gib-bons, hornbills, and Toe Khae (similar to but smallerthan the hornbill) in the forests. The most commonanimals present are various kinds of monkeys (TaUu, Wah Mae), deer, barking deer, wild buffaloes,gaurs, bears, wild pigs, and many kinds of birds.There are ten reserve forests in Doo The Htoo dis-trict. The British colonial government establishedeight of them; the other two reserve forests were setup by the KNU after Burma became independent.All of these reserve forests are in the five townships

administered by the KNU. Da Thu Lu reserved for-est is in Kyaito Township. O Kan Gyee, Bee LakanGyee and Tagaylaw reserve forests are in BilinTownship. Kyakat Chaung, Pabein, Toe Bo Gyee,and Dernu are in Thaton Township. Kyo Sein re-serve forest is located in Pa-an Township, andKalamat reserved forest in Paling Township. Toe BoGyee and Demu reserve forests were set up by theKNU. The KNU declared Kyakat Chaung a wildlifesanctuary in 2000.

Currently the status of the forests has completelychanged. The Doo The Htoo deputy district officerof the KNU, Saw Oh Shwe estimates that only about15% of the forests are left. Even the reserve forestsexist almost only in name, except for some remainsin Bilin Township. According to a Bilin Townshipofficer, the total area of the three reserved forests inhis township is about 5,252 acres, of which 20% isactually still forest, mostly in Bee Lakan Gyee re-serve forest. A small piece of forest is left in Tagay-law but O Kan Gyee reserve forest is alreadycleared.Populations of wild animals are dramatically in de-cline. Only a very few wild animals are found inKyakat Chuang wildlife sanctuary. Villagers nolonger see wild animals inside or outside the reserveforests. Rare animals such as the tiger and the rhi-noceros are gone from the wildlife sanctuary.

18

Destruction and Degradation of the Burmese Frontier Forests

Environmental conditions have radically changed.Rivers dry up in the summer, and have a lower levelin the rainy season than in the past. People travellingin these areas can no longer rest in the shades of thetrees and always have to carry their own drinkingwater.Despite the serious degradation of the forest, loggingcontinues. Together with the collection of firewood,the charcoal business, the expansion of mono-cropplantations, and regular forest burnings by SPDCsoldiers, the remaining forests are in serious danger.

2. The importance of rainforestfor local communities

The rainforest plays very important roles inthe livelihoods of the local communities in Doo TheHtoo district. Rotational farming is a vital part ofagriculture, and depends on good forest to producesuccessful yields. Traditionally, villagers let the landlie fallow for at least seven years. Another kind ofagriculture is irrigated paddy farming. The tradi-tional irrigation system is very productive becausethere are lots of organic substances like leaves andother tree litter that drops and decomposes in thecanal. This organic matter flows with the water intothe field and fertilizes the paddy fields. Forests alsoprovide good conditions and fertility for the localcommunities' orchards. Many villagers plant betelnut (areca nut), dot fruit, durian, coconut, jackfruit,plum mango (Takaw Hsi Tha), Livistona speciosa

The designated reserve forests have helped pro-tect the land, but that protection has not beenadequate. Most of the reserve forests, as muchas 85%, have been felled for timber or for per-manent conversion to cultivation. The KNUprotected areas still provide habitats for somewild animals, but these areas are inaccessible forvillagers. The only suitable logging area left inDoo The Htoo district is in Bilin Township.Here, since 1996, the SPDC has pursued a newpolicy to avoid KNU resistance to the logging.The SPDC loaned money through a stale-ownedlogging company to local Karen elites who es-tablish logging operations and sell the timber tothe Myanmar Timber Enterprise (MTE). Theseelites also negotiate with the KNU to safeguardtheir operations. The KNU used to ambushstate-owned logging business operating in theirareas. But DOW it grants permission and taxesthe loggers. This has caused tension between thevillagers and the KNU because the loggers haveaccess to the reserve forests while the local vil-lagers do not.

Transferring of logs to stockpile using elephant labour

(Lo Htu: have big leaves which look like palmleaves and are used for thatch), palm trees, sourgrapefruit (Shau Thee), leech lime or kumquat,(Shaunu Thee), lime, pomelo (Ma O) and other spe-cies in the forest. These orchards are not only forhousehold consumption but also provide extra in-come.In addition to agricultural benefits, forests aresources of food (wild vegetables, fruits) and medi-cines. Most of the materials for buildings and bas-

ketry come from the for-est. Forests used by thecommunity as a whole arecalled community forests.They also serve as pasturefor the cattle.Forests are very impor-tant in religious beliefsand practices. In theTaung Lweh village com-munity, every year inMay, a ritual ceremony isperformed in a sacred partof the forest. Red andwhite cloth is wrappedaround two big trees. Notrees in the sacred forestmay be cut down. Thiswould lead to illness anddeath to the members ofthe community.

19

Destruction and Degradation of the Burmese Frontier Forests

3. Social and ecological impacts ofdeforestation on environmentand local communities

Farmers face the consequences of meteoro-logical changes leading to droughts and floods.Flooding kills most of the rice. What is left of therice is destroyed by a tiny green insect. Anotherproblem is a small caterpillar that eats the leaves inthe night-time and stays under the rice in the day-time. When the rice produces the seeds, small cater-pillars cut through the branches of the seeds and eatthem. During harvest time (dry season), when itstarts raining, the seeds get wet, sprout, and growagain, which is another major problem.Since 1996, the situation has deteriorated. Accordingto the villagers this was when deforestation led tochanging climatic conditions. An average farm nowproduces 20 to 30 baskets of rice per acre, where itonce produced 80 to 100 baskets of rice per acre.The nutritious qualities of the soil have deteriorated,"When we used the water from the river there was alot of humus from the tree leaves and mud flowingwith the water into the farm. This made the soil fer-tile", villagers explained, "When the river dried upwe had to depend on rain in the rainy season. So wedo not get the fertile soil." The diminished yieldsmean food shortages, and the people have problemsto pay their taxes to the SPDC. Many farms wereabandoned and people prefer to work as casual la-bourers in the logging and other enterprises to maketheir living.Logging is not the only problem. People cut bam-boo, bamboo shoot, and firewood for commercialpurposes. Another problem is the deterioration of

Logging has caused:

* a serious threat to local biodiversity. For ex-ample traditional healers find it increasinglydifficult to find medicinal plants; this couldlead to loss of indigenous knowledge.

* water shortages. The diminishing supply ofwater available for irrigation (which is morenutritious than rainwater) has led to decliningrice yields in wet paddy cultivation.

This causes a downward ecological spiral, sincevillagers are forced by insufficient rice harveststo become casual labourers in logging operationsand other enterprises.

health care due to the logging. "My mother knewtraditional medicine. Villagers came to her to becured of their diseases, 1 assisted her and when shedied, I became traditional healer in Ta Uu Kee(Taung Lweh) village. I collect medicine from thetrees in the forest. Some patients I can cure with thismedicine. But some patients I can't cure with thismedicine. I don't charge the patients and accept any-thing they would like to offer me. Sometimes theygive me foods and sometime they give me money."This traditional healer claimed that in the past hecould find the medicine in the forest easily, but sincethe logging has started some medicine can not befound anymore. "1 replant some medicinal plants andtrees in my garden. Some disappeared medicine wenow have to buy in the city." In Ta Uu Kee (TaungLweh) village the elder is the only person who stilluses traditional medicine. For many people tradi-tional knowledge has been lost. They want westernmedicine, but it is very expensive. It is also ex-tremely dangerous to have because the SPDC doesnot allow it, fearing that the medicine will be passedon to the Karen National Liberation Army (militarywing of the KNU).

Impacts on women

In Doo The Htoo district the villagers have to dealwith three different political groups: the KNU, theDKBA, and the SPDC. They are liable to have to dowork for all three groups. Women and men have dif-ferent roles for their work. One of the women inKyakat Chaung (Ta R'weh Kee) village, ThatonTownship, said that women have more work to dobecause their men are forced to serve as porters, se-curity guards, and in other jobs for the BurmeseArmy; sometimes for 20 days a month. The remain-ing 10 days they are tired, sick, and bored to workon the farm. This changes the division of responsi-bilities traditionally shared by men and women,Although the Karen are family-based and involveboth male and female input in most decisions and incultivation practices, they are a matrilineal culture,thus the women are highly affected by changes inthe forest. Both male and females have access to theforest, however females predominately spend moretime, collecting forest products both for family-useas well as for extra income, and working on the land.With the decreasing forest products, they cannot col-lect enough to provide for extra income, and thuswith lack of income they cannot send their childrento school.Women are responsible for the housework and arethe primary house owners. Their responsibilities in-clude taking care of the children, feeding the family,

20

Destruction and Degradation of the Burmese Frontier Forests

Urban dwellers collecting timber from the forest and selling it in the city

feeding the animals, collecting water, collecting fire-wood, pounding rice, and cleaning. Additionally,they are responsible for all daily work when the menin the family have to serve for the military or be por-ters. The women also have to answer to SPDC mili-tary demand. The military will ask the women forfirewood, building materials for their camps, nightwatch duty, and other jobs which conflicts withother regular tasks.

4 a. Logging

4. Main factors that threaten thepractices of traditional forestconservation

Traditionally the local communities in DooThe Htoo district have their own system of forestmanagement. In the customary traditions each vil-lage has its own community forests with clearboundaries. Within this community forest land thereare rotational farms, irrigated farms, orchard farms,communal forest, pasture, and sacred forest. Thissystem has worked very well until recently. Nowhowever, many factors threaten or weaken the sys-tem. The main interrelated factors are logging, prob-lems of forest management and access to the forests,the civil war, and the introduction of monoculture.

Since 1973, the Burmese military government hasbeen heavily logging the forests in Doo The Htoodistrict. This logging has targeted most of the re-served and communal forests. Logging in BilinTownship forests exemplifies the situation. In 1992,SPDC troops advanced to Bilin Township. They alsomade the area secure for logging by building roadsand bringing in trucks, machinery, and other mate-rial. Since then, the military-backed logging opera-tion exploited the three reserve forests in BilinTownship. However, continuing surprise-attacks onthe logging operation by the KNLA, the military armof the KNU, did severe damages to hardware, per-sonnel, and profits; thus the SPDC changed its strat-egy in 1996, This time it used local Karen business-men (the 'log extraction group') to do the loggingand to negotiate with the KNU, believing that theKNU would not attack their own countrymen. TheSPDC-controlled Myanmar Timber Enterprise(MTE) loaned about four million kyat to each of theKaren entrepreneurs through U Bah Than, the MTE-manager in Pa-An township. Condition of the loanwas the exclusive sale of the timber to MTE. Timberwas collected at two central stockpiles, Dun YaySeik and Tor Prah.KNU district officials saw a chance to let the log-ging be of benefit to the KNU struggle. One seniorKNU district reasoned: "The SPDC has a militaryforce and they have occupied many of our controlledareas, one after another. So even if we didn't deal

21

Destruction and Degradation of the Burmese Frontier Forests

with the logs extraction group the SPDC will do thelogging anyway and there is no benefit for theKNU." The logs extraction group agreed to pay theKNU 5,000 Kyat taxes per each ton of timber. Thenthey could execute their operations without hin-drance. Local villagers report that the KNU allowedlogging in an area outside the reserve forests of ca,31.25 square miles.

4b Forest managementand access to forests

Granting logging permissions either inside or out-side of reserved forests by the KNU is a controver-sial issue, and has led to conflict between the KNUand villagers in Bilin Township. The areas outsidethe reserve forests are supposed to be for public use.The reserve forests and especially teak and otherhardwood trees, officially under the management ofthe SPDC forestry department, are under control ofthe KNU and are protected by forestry laws. TheKNU have forestry laws that prohibit the cutting oftrees in the reserve forest, on penalty of seven yearsjail or death for second offenders. The laws allowvillagers to collect wood for household necessitiesoutside the reserve forests. Burning forests violatesKNU forestry laws and the violator must pay a fine.The villagers in Bilin Township area said: "We haveno trees for building our house because of the log-ging, while the KNU does not allow us to cut onetree. But they allow the log extraction group to dologging." The local communities are not satisfiedwith the KNU,claiming that it isnot fair that they donot even have theright to use timberfor their domesticneeds.As a result, somevillagers started ille-gal logging whilethere were still treesin the reserve for-ests. A few of themwere arrested andtaken for interroga-tion. The villagersreported that thelower ranking offi-cials of KNU wereintoxicated by alco-hol-use and theytreated the suspects

badly. Many villagers fell very unsatisfied with this.This state of affairs was reported to a well-respectedKNLA officer, lieutenant colonel Htu Gaw, com-mander of 1st KNU brigade in Doo The Htoo dis-trict. He called for a meeting of all district officials,including the KNU forestry department, and toldthem: "If you don't give my children [the villagers]the chance to collect wood to build their houses, wecan not resolve the conflict and will be distrusted byour own people," Finally the other KNU officialsagreed to let local villagers to collect a certainamount of wood for building material in March2002. As soon as access rights were conceded to lo-cal communities, illegal logging by outsiders alsostarted to occur. Because of this, the KNU withdrewits permission after one year. The KNU district lead-ers said they would call another meeting and if nec-essary, issue another permission period. So far, theconflict between the KNU and the local communi-ties is still unsettled. Thus the attempts of local peo-ple to conserve traditional forest management aredisencouraged by the offical forest administration.

4c Civil war

As part of the SPDC 'Four Cuts policy', restrictionshave been placed on the movements of villagers,Villagers are not allowed to do rotational farmingoutside a distance of a one-hour walk. They maywork their fields only from 6 o'clock in the morninguntil 6 o'clock in the evening and everyone has to beback in their community by that time. If anybody is

Urban migration: burning of forest for easy collection of firewood in order to take back and sell in thecity

22

Destruction and Degradation of the Burmese Frontier Forests