Ordinary Writing and Scribal Culture in Nineteenth-Century Spain: Memory Books

-

Upload

antonio-castillo -

Category

Documents

-

view

213 -

download

0

Transcript of Ordinary Writing and Scribal Culture in Nineteenth-Century Spain: Memory Books

This article was downloaded by: [Stony Brook University]On: 27 October 2014, At: 15:59Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registeredoffice: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

The European Legacy: Toward NewParadigmsPublication details, including instructions for authors andsubscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cele20

Ordinary Writing and Scribal Culturein Nineteenth-Century Spain: MemoryBooksAntonio Castillo Gómez aa Department of History I and Philosophy , University of Alcalá, c/Colegios, 2, Alcalá de Henares , Madrid, 28801, SpainPublished online: 26 Aug 2011.

To cite this article: Antonio Castillo Gómez (2011) Ordinary Writing and Scribal Culture inNineteenth-Century Spain: Memory Books, The European Legacy: Toward New Paradigms, 16:5,615-631, DOI: 10.1080/10848770.2011.599554

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10848770.2011.599554

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the“Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis,our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as tothe accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinionsand views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors,and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Contentshould not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sourcesof information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims,proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever orhowsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arisingout of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Anysubstantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms &Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

The European Legacy, Vol. 16, No. 5, pp. 615–631, 2011

Ordinary Writing and Scribal Culture inNineteenth-Century Spain: Memory Books

ANTONIO CASTILLO GOMEZ

ABSTRACT This article is a study of the survival of scribal culture in nineteenth-century Spain in the form of the

so-called ‘memory books’ ( libros de memorias). I analyse their relationship with the educational developments

of the period, as well as the material characteristics and the content of these texts, in order to define their typical

features. These texts were the products of hybrid writing practices, in the sense that several elements were

frequently superimposed on one another: economic news, personal, family and social events and even historical

details. Hence the similarity between the memory books and other genres such as account books ( libros de

cuentas) and family books ( libros de familia). Lastly, I will examine some nineteenth-century examples as

epigones of a writing genre which had its origins in the later Middle Ages and Early Modern period.

‘‘One morning, while tidying up the bedroom, Rosa opened the drawer in the trunk

where Cholo kept his papers. There she found the papers about the property and, in a

corner, together with the Family Book and the social security booklet, the papers from

the bank [. . .]. And she was about to put it away when it occurred to her to take off the

elastic band around the big folder which Cholo had kept from his time in Switzerland.

There were things, names and so on that she didn’t understand, but in the middle there

were also some of the cards she had sent from Aran.’’1

1. INTRODUCTION

Leaving aside the emotion and the family secrets in my opening quotation as typical

features of literary fiction, it nevertheless illustrates my topic in its evocation of an

important site of family memory. The chest of drawers where Cholo kept his papers

could easily be taken as the fictional representation of the disappearing habit of preserving

the most fragile memories of the lives of ordinary people. At the same time, in the above

citation from the Galician writer Manuel Rivas, we can observe a daily relationship with

writing which has existed for centuries. Its importance for the individual and the family is

linked to the democratisation of writing and its exponential expansion in the

contemporary era. This link is demonstrated in the preservation of official documents

recording the status and profession of the individual, his or her properties and leisure

activities, as well as in different forms of private writing (letters, diaries, memoirs etc.).

Department of History I and Philosophy, University of Alcala, c/ Colegios, 2, Alcala de Henares, Madrid, 28801, Spain.

Email: [email protected]

ISSN 1084-8770 print/ISSN 1470-1316 online/11/050615–17 � 2011 International Society for the Study of European Ideas

DOI: 10.1080/10848770.2011.599554

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ston

y B

rook

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

5:59

27

Oct

ober

201

4

Nevertheless, these memory trunks (baules de memoria), to adopt the happy phrase coined

by Federico Croci and Giovanni Bonfiglio in their study of emigrants’ writings,2 do not

always include everything connected with the individual and the family. We may have

lost a few records along the way, some hidden away or destroyed because too

compromising, others just missing by accident so that, as Philippe Artieres argues, the

ordering and selecting of what remains constitutes a more or less conscious

autobiographical choice.3

Among the mass of private papers there is one particular form of writing that comes

under the heading of ‘memory books’ (libros de memorias), understood as the books in

which one noted what might be forgotten, whether it related to work or property, or

whether it was connected to the family or recorded other events. As we know, it was a

form of writing with a long history behind it. Its origins as a genre go back to the Late

Middle Ages, when artisans, merchants, bankers and a few peasants found it necessary to

record their accounts in writing. They produced books which they sometimes signed and

sometimes entrusted to an intermediary. In Italy, the practice seems to have been in

decline after the sixteenth century,4 but in Spain it persisted into the modern period,

although it was mostly limited to Catalonia and Valencia.

What happened to the ‘memory book’ in modern times? Although the popular

conquest of writing may have been slow, it was steady and was becoming a reality, as we

can see in the abundance of letters, diaries, memoirs and other personal and domestic

writings which survive from the nineteenth century onwards, even if our knowledge of

that reality remains partial.5 Numerous scenes and representations in contemporary art

and literature echo the involvement of ordinary people in writing and show that it was

becoming an everyday practice. See for example La carta del hijo ausente [The letter from

the absent son], painted in 1881 by Maximino Pena Munoz, an artist from Soria who

captured the anxious desire to receive news from an absent family member—a situation

which the painter, himself an emigrant, knew at first-hand.6 The artist draws an

interesting contrast between the illiterate parents and the literate son, a faithful reflection

of the progress which had been made by then.

Nevertheless, before answering it is just as well to be clear that our knowledge is

quite insufficient. In Spain, the study of private writings in the early modern era has

developed considerably, but as far as the nineteenth and twentieth centuries are

concerned, it has only been in the last decade that scholars have begun to investigate this

area, above all thanks to the new generation of researchers in scribal culture.7 Apart from

edited texts, which mostly consist of diaries, memoirs and correspondence, there now

exist some general theoretical surveys and inventories of autobiographical writing.8 There

is, however, a scarcity of studies which specifically address the variety of writing contained

in memory books. Among the few works which do so is Xavier Torres Sans’s study of

peasant family books in Catalonia, although its main focus is on the period between the

sixteenth and eighteenth centuries.9 Carmen Rubalcaba Perez dedicated some pages of

her work on writing practices in nineteenth-century Santander to the account books of

Policarpo Pando and Pedro Jago Aguero.10 In addition, Jordi Curbet Hereu produced an

annotated edition of the ‘‘llibretes de memories’’ of Joan Serinana (1818–1903).11

This article builds on these works and offers some fresh reflections, while treating

them as evidence of writing practices and witnesses to the survival of scribal culture. This

select group of manuscript texts illustrates nineteenth-century cultural practices, even if

616 ANTONIO CASTILLO GOMEZ

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ston

y B

rook

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

5:59

27

Oct

ober

201

4

some may have started life in the last decades of the eighteenth century, and others were

still being composed in the first decades of the twentieth. The corpus of documents

consulted—some in the original, others copied and a few published—consists of 18

examples, a fairly representative group within a total production which still resists precise

quantification. In Catalonia, which has attracted most attention so far, 17 have been

identified for the nineteenth century, to which we should add 8 originating in the

eighteenth century, and at least another 5 which between them cover the period between

the sixteenth and twentieth centuries.12 Although we lack a precise census of memory

books, if we confine ourselves to those written in the nineteenth century we arrive at a

total of over 30, which is substantially more than the 18 livres de raison counted in

France.13

2. LITERACY, SCHOOLING AND AN APPRENTICESHIP IN HANDWRITING

It follows from this that the development of writing as a social practice is connected with

the educational and cultural changes of the second half of the nineteenth century,

especially the impetus then given to primary schooling, the importance of which was

recognised by the Moyano Law of 1857. Thus whereas in 1831, the level of school

attendance was less than 25% of children of school age, in 1879 the figure was 47%, and

by 1914 it had risen to 56%.14 As a result of economic progress in this period, and factors

like the more widespread presence of books and reading in society, especially with the

rise of public and popular libraries, the number of literate people rose considerably. At the

same time, an alarming gender gap still persisted, not to mention regional differences, so

that at this time Spain found herself listed along with Russia, Italy, and Hungary amongst

the least literate countries in Europe.15 Taking all this into account, the overall national

literacy rate increased progressively during the late nineteenth century and accelerated

further in the first third of the twentieth, rising from 27% in 1860 to 45% in 1900 and to

73% in 1930.16

Other aspects besides the rise in literacy are equally relevant in explaining the

expansion of private writings. There were changes in the way writing was taught in

modern schools, in particular cursive handwriting was introduced into the curriculum

with the help of publication series like Lecturas de manuscritos [Manuscript readings].17 Its

pages offered a complete repertoire of models for ordinary writings, that is to say, from a

functional point of view, the writing used to manage and resolve various situations arising

out of daily life. One book in this series, the Guıa del artesano [Artisan’s guide], appeared in

its first edition in 1859 at the author’s own expense, and carried the explanatory subtitle

‘‘A work containing all kinds of documents frequently needed in the course of one’s life

and 220 model-letters to assist in the reading of handwriting.’’ As the 1913 edition made

clear, the number of ‘‘model-letters’’ had risen to 240, and the book was directly aimed at

familiarising the reader with a graphic culture designed for everyday tasks. This is how a

notice for the work explained its contents:

1. The reading of various manuscripts, set out in model letters appropriate to our

century, and commonly used in all kinds of handwritten documents.

2. A collection of common and necessary documents which do not require the

approval of a public writer or notary.

Ordinary Writing and Scribal Culture in Nineteenth-Century Spain: Memory Books 617

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ston

y B

rook

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

5:59

27

Oct

ober

201

4

3. Practical spelling, contained in a small number of letters, the main problems

associated with words of similar sound but different meaning in our language.

4. For dictation classes, a variety of material which can be usefully taught in schools, in

conformity with Article 73 of the Rules previously cited.18

Apart from the questions of spelling and dictation mentioned here, we should

especially note that the first two items lead directly into commonly used forms of writing.

They aimed to immerse the reader in different kinds of writing and documents in

everyday use, such as personal and business correspondence, leasing contracts, accounts,

reports, official letters, contracts of sale, receipts, advertisements, tickets, announcements

of death, worksheets and so on.

3. MEMORY BOOKS

It was not simply a question of demonstrating different models, as was emphasised in the

preface to another book in the same genre, Grafos. Segunda serie de manuscritos [Writings:

Second manuscript series] by Jose Frances, which won prizes at the Valencia Regional

Expo in 1909, the National Expo in 1910, and the International Expo in 1912. The aim

was rather to facilitate contact with writing technology which could be used in private

life, commerce, literature and for official purposes, and these spheres shaped the four

sections into which the contents were divided, each with its corresponding introduction.

My study is concerned with the first of these parts—writing in private life. The

introduction began with the Latin quote proclaiming the permanence of writing as

opposed to the temporary nature of speech, and it reminded the child Ricardo, to whom

the text was addressed along with every schoolboy of the period, that letters, postcards

and other manuscripts ‘‘will remain behind, even after you die, as records of your past

life.’’19 Then followed different model letters, some telegrams, postcards, clear evidence

of the expansion of epistolary communication as a social practice. It concluded with a

selection of pages from a fictitious yet true-to-life ‘‘memory book’’ that Ricardo’s father

had given him to start recording his impressions, just as his father used to record ‘‘the most

important events of his life’’ in another book ‘‘the same shape but larger,’’ which he kept

in his study (45) (Fig. 1). He started his notes on 12 September and other pages followed

at particular times and particular months from 1910 to 1911, referring usually to his classes

at the Institute, his exams and other cultural experiences, like the day he went to a

concert at the Teatro Royal or when he went to the Athenaeum with his father and a

friend (45–60). So this was a notebook containing various entries and it was similar to the

one recalled in the following words by the writer Mariano Jose de Larra in one of his

newspaper articles entitled ‘‘¿Quien es el publico y donde se encuentra?’’ [Who is the

public and where can I meet it?]:

I leave the cafe, I wander through the streets and at least I can enter hotels and other

public places; a growing crowd of Sunday customers is making a noise, eating and

drinking and the place is humming with their turbulent din; they are all full of people;

everywhere the Yepes and the Valdepenas are loosening their tongues, just as the wind

blows the weather-vane and water turns the millstone; already the thick vapours of

‘‘Baco’’ are beginning to go to the public’s head and it can’t hear itself speak any more.

I almost go and write in my memory book: ‘‘The esteemed public is drunk’’; but

618 ANTONIO CASTILLO GOMEZ

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ston

y B

rook

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

5:59

27

Oct

ober

201

4

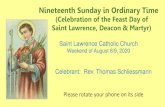

Figure 1. Jose Frances: Grafos. Segunda serie de manuscritos, Valencia: S. Mirabet, ca. 1913, p. 45.

UAH, SIECE, AEC, FE 1.12.

Ordinary Writing and Scribal Culture in Nineteenth-Century Spain: Memory Books 619

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ston

y B

rook

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

5:59

27

Oct

ober

201

4

fortunately the end of my pencil breaks at this inopportune moment, and since I don’t

have anything here to sharpen it with, I keep my observations and my gossiping tongue

to myself.20

Far from taking us into the realm of fiction, these imaginary fragments from the

memory books of the student Ricardo or the writer Larra give us a few clues to

understand the defining characteristics of this form of autobiographical writing. Its

content and writing processes put it somewhere between a diary and a memoir. A diary,

according to Manuel Alberca, ‘‘should be written as each day and its experiences are

lived, with no plan other than to try to capture within its pages the passage of time and

the impressions it leaves on the writer,’’ so that it ‘‘can absorb events large and small in no

preconceived order or shape other than that of the calendar.’’21 The diary is close to lived

experience and lacks perspective. It remains attached to feelings and day-to-day comings

and goings in a way that does not occur in memoirs, which embody a series of structured

memories organised in sequence, whether chronological or thematic or both.22 Memory

books are not the product of memorialising after the event, but are the same length as

diary entries, in other words they are written according to the same rhythm at which the

events described actually occur. This, however, does not rule out the insertion of

memories and evocations of the past. In addition, they share the miscellaneous character

of the diary’s contents. Thus in the handwritten Apuntaments y recorts per Joaquim Viladerbo

[Notes and memories of Joaquin Viladerbo], erroneously dated 31 February 1889, in

Barcelona, the author recalled the family farmhouse in the municipality of Tagamanent,

which went back to the thirteenth century, and he added various other things, including

a collection of poetry.23

The Quadernos de algunos apuntes curiosos [Notebooks of some curiosities], by the

Canary Islands merchant Antonio Betancourt, preserved in the Canary Islands Museum,

lists events strictly in their chronological order. They consist of five in-quarto manuscripts

written between 7 January 1796 and 18 October 1807 to leave some record of events

concerning himself and his family, but also including various events which occurred

during those years at Las Palmas (Grand Canary), whether related to commercial and

maritime affairs, religious questions, festivals, historical notes or social issues.24

Pedro Santos Fernandez, a weaver from Tuy in Galicia, left a similar manuscript in

the same format, entitled Libro de memorias y barias apuntaciones para apuntarlas segun ban

sucediendo, por sus dıas, anos y meses, como en el ası se contienen [Memory book and various

notes to explain the happenings of days, months and years, as contained within]. The

author recorded a host of personal, family or public events in the years 1779 to 1826,

preceded by a pair of registers covering 1777—the construction of the organ in the

convent of the Franciscan Sisters of the Immaculate Conception, on which Pedro Santos

worked for seven months as servant to the maestro organist—and 1778, when he was

employed as secretary to Benito Duran en Poyo for nine months. Initially, his notes

tended to be brief and precise, as in the entries for 1781–1790, which included the death

of his father on 6 January 1781, his marriage to Catalina Gomez on 3 January 1782, the

fire at their country house on 18 July 1783, the blessing and installation of the new

cathedral bell on 16 February 1788. and the snowfall of 8 January 1789. From 1791

onwards, more detailed information is included and the narrative becomes denser. The

manuscript is completed by two final folios written by his nephew Luis Blas Senra, with

620 ANTONIO CASTILLO GOMEZ

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ston

y B

rook

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

5:59

27

Oct

ober

201

4

dates of births, marriages, and deaths within the family, followed by fragments about the

conflict between cristinos and Carlists in summer 1837.25

Three of the 20 or so surviving memory books by the vintner Joan Baptista

Serinyana i Mallol (1818–1903) are especially significant in this respect. Leaving aside the

others, all handwritten, with his maps, prayers and moral tales, recipes and miscellaneous

notes, these three books are interesting both in terms of their content and the titles on the

covers:

(1) Libreta de memorias de Juan Batista Sarinana, escrita lo an 1851 y cupiada lo an 1879

[Memory book of Juan Batista Sarinana, written in the year 1851 and copied in the

year 1879], no doubt composed from the previous book of which a few loose pages

survive (Fig. 2);

(2) Llibreta de memorias de barias notas: Prime de la Guerra y Rebulocions de Espana, y altres

notes del meu recort ynventadas las maquinas y carril y altras notas desde lo an 32 fins lo an

1852 fins al present. Jo Juan Bautista Sarinana, de hedad 47 ans [Memory book of

various notes: First on the war and revolutions in Spain, and other notes of my

memories of the invention of the railway engines and other notes from the year 32

up to the year 1852 up to the present day. By myself, Juan Bautista Sarinana, 47

years of age], which indicates that he began it in 1865;

(3) Llibreta de memorias de barias notas escritas por J[uan] B[autista] S[arinana] [Memory

book of various notes written by Juan Bautista Sarinana], with the additional title

inside the cover: de memorias antigas y modernas escritas per mans propias de mı, Juan

Bautista Sarinana y Malloll, de edad satanta ans y escrita lo an 1889 [Memoirs ancient

and modern written by my own hand, Juan Bautista Sarinana y Mallol, seventy

years of age and written in the year 1889].26

All three share the same title—Libreta de memorias—even if the title also includes

different additions alluding to the specific content of each book. This lends a certain

ambiguity to the genre and this has been pointed out for equivalent testimonies in

previous centuries.27 As Jordi Curbet Hereu has stressed in his edition of these notebooks,

the author was someone who did not possess great writing skills, but we cannot help

noting his ‘‘graphomania’’ and the distinction he maintained between these different

artefacts of memory. The first notebook contains notes on economic and family matters,

which makes it a libro de familia, especially since it was continued in the same vein by

Sarinana’s eldest son Jaume. The second is dedicated to notes and memories which

resemble a historical chronicle. He used the third book to record religious events,

especially his activities as a member of the Confraternity of the Sacred Heart of Jesus,

whose emblem is attached to the book’s cover.

4. FROM THE ACCOUNT BOOK TO THE FAMILY BOOK

We must not of course assume that this was always the case; it depended a lot on each

case and above all on the number of notebooks used. The rational ordering of the

memory represented by Juan Sarinana’s three notebooks is most likely to be the work of

individuals familiar with writing or with proven graphic ability. When these qualities are

less in evidence, accounting is frequently combined with family records and social events

Ordinary Writing and Scribal Culture in Nineteenth-Century Spain: Memory Books 621

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ston

y B

rook

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

5:59

27

Oct

ober

201

4

Figure 2. Libreta de memorias de Juan Batista Sarinana, 1851 y 1879. Cover. Private collection.

622 ANTONIO CASTILLO GOMEZ

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ston

y B

rook

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

5:59

27

Oct

ober

201

4

within the same graphic space. The page thus becomes an instrument of memory and the

expression of individual identity.28 In such cases it is normal to find, in different degrees,

that the accounts are interrupted from time to time, giving way to autobiographical

details, especially births, weddings, deaths and other personal or family events. Thus in the

book of Benito Sanz, from near Guadalajara, covering 1822–1852: ‘‘My beloved brother

Juan Sanz passed away on this day 21 November 1897/ his sister Dorotea Sanz’’ or ‘‘My

beloved sister Paulina passed away on the day of 27 November 1891, her sister Dorotea

Sanz’’ (fol.133v).29

The family book of Rodrıguez Menendez, from Inclan in the Asturias, is another

example (Fig. 3).30 As well as any event which might affect the family in one way or

another, we find an appointment to a public office, the enrolment of his sons in school,

military recruitment or a change of address in search of new opportunities, among other

notes: ‘‘Night school in Yervo. On the night of 4 October 1843 my sons Manuel and

Francisco started school.’’31 The following are examples of this kind of book:

(1) The account book (Libro de cuentas) of the Rodrıguez Menendez family of Inclan

(Asturias), with notes starting in 1800 and extending up to 1955;32

(2) The cash or account book of Benito Sanz, inhabitant of El Cubillo de Uceda

(Guadalajara), dating from 1822 to 1852;33

(3) The account book of Andres Dıaz, a proprietor of Talamanca del Jarama (Madrid),

which begins in 1826 and continues up to 1897, and in which different family

members contribute to the writing;34

(4) Cash book of D. Juan Gomez Castrillon, resident in the locality of Yerbo, in the

year 1828, also used by other members of the family until 1874.35

The authors of these notebooks just cited were mainly fathers with families,

landowners, administrators or merchants, and they recorded all their income and expenses

in their role as managers of the family property, so as to keep an account of every

transaction for their own reference.36 As a consequence the involvement of women as

authors was quite rare, but they contributed as widows, or else appeared in specific and

circumscribed roles, as in the example already cited of the death notices which Dorotea

Sanz entered in Benito Sanz’s account book. One text was entirely the work of a woman:

the memoirs of Isabel Piferrer (1814–1833), mistress of the Anglada farm at Vilert

(Girona), which she wrote when she was 67, two years before her death, in a 28-page

quarto notebook.37

The notebooks reflect a logical graphic organisation of family assets and accounts,

having as its main axis the progressive story of individual agreements, with numerical

quantities listed laterally, sometimes in columns to facilitate comparisons and subsequent

calculations. The author’s signature is often present too on every page where he acts as

borrower or beneficiary (either his own signature or that of an intermediary in cases

where he might be illiterate or incapacitated) (Fig. 4). When the income and

disbursements had been reconciled and the ledger had lost its practical utility, the

agreements were usually cancelled or marked with a cross, and the pages even torn out of

the notebook, which shows the practical character of this type of book (Fig. 5). For the

same reason we can sometimes find alphabetical marks (for example in the ledger of

Policarpo de Pando) or tables of contents referring to page numbers (as in that of the

Asturian family of Rodrıguez Menendez).38

Ordinary Writing and Scribal Culture in Nineteenth-Century Spain: Memory Books 623

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ston

y B

rook

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

5:59

27

Oct

ober

201

4

Figure 3. Record of Faustino Rodrıguez Menendez’s death in his libro de familia, 21 February

1890, fol. 146r. Gijon, MPA, 136/5.

624 ANTONIO CASTILLO GOMEZ

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ston

y B

rook

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

5:59

27

Oct

ober

201

4

Figure 4. Faustina Fernandez’s receipt in Juan Gomez Castrillon’s account book, written by

witness Manuel Rodrıguez, Yerbo, 18 July 1913, s. fol. Gijon, MPA, 136/4.

Ordinary Writing and Scribal Culture in Nineteenth-Century Spain: Memory Books 625

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ston

y B

rook

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

5:59

27

Oct

ober

201

4

Figure 5. Benito Sanz’s account book, fol. 7v. UAH, SIECE, AEC, FMe 1.1.

626 ANTONIO CASTILLO GOMEZ

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ston

y B

rook

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

5:59

27

Oct

ober

201

4

As Carmen Rubalcaba Perez has pointed out in her study of the account books

preserved in the Archive of San Roman de Escalante,39 they resemble the structure of a

diary, in the sense that entries are made as receipts come in, expenses go out and other

events happen. They deal with four main themes: family assets, its properties and their

administration, and inheritances or litigation related to them; the family as a group, seen

through births, marriages, deaths and illnesses; social and family life, for instance the

tenure of public office, political and community events, the occupations of and advice

given to descendants; and the bizarre and curious, a category including all kinds of rare

and unexpected occurrences.40

Almost all these books were written by several generations of the same family, and as

a result they lack closure, or as Raul Mordenti puts it ‘‘this very remarkable relationship

established between writing and family survival explains why these texts have no ‘end’,

and why, in every case, they would be unexpectedly cut off if one day the family died

out.’’41 The written testimony of each generation appears as an open-ended process, in

which various people participate, their handwriting obeying the organisation of graphic

space laid out by their predecessors, sometimes spanning a considerable period, as in the

memory book of the Anglada family, which begins with an entry by Miguel Anglada in

1612 and concludes with another Miguel in 1808.42 Even Rodrıguez Menendez’s family

book covered the period 1880 to 1955, when a pencilled entry noted the death of Marıa

del Amparo Mendez Quintero at the age of 87.43 Many examples like this clearly fall

within the category of libros de familia, defined by their most eminent students Cichetti

and Mordenti as ‘‘multi-generational diary-like writings, in which the family, both as

sender and addressee, constitutes the main theme and the medium of textual

communication.’’44 Its preservation as an instrument of family genealogy and estate

management aided its material survival; normally the books consisted of several small

paper notebooks in quarto format, with a protective cover of parchment reinforced at the

edges, and with leather straps to keep the book closed.

The aim is therefore to take up pen and paper to register, communicate, preserve

and transmit a collective memory within a domestic space. Individual, family and

collective events, religious and festive occasions, plagues and diseases, form the axes on

which the workings of the group’s memory were articulated. In this sense, the account

books and memory books of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries represent the

final link in a chain which stretches back to the early modern period and which

developed into a distinct corpus in the family books of small peasant landowners in the

sixteenth to eighteenth centuries. In analysing many of them, we become aware of their

hybrid character; they were, in the words of the opening of Joan Guardia’s account book,

to be continued by his son Antoni Juan (1631–1687), ‘‘books of blank paper for writing

accounts,’’45 although once a book was started, the memory often took a direction quite

different from that of strict economics.

This overview of nineteenth-century memory books demonstrates the longevity of

this genre of writing. It offers convincing proof of the intense dissemination of

handwriting in the private sphere at this time, and its spread wherever it was needed to

resolve concrete situations, as reflected in the growing number of studies on the different

typologies of personal writings.46 Thus the focus shifts from writing as an instrument of

communication to writing as a practice, and the ways in which it was appropriated as a

technology of the word.47 Furthermore, the history of memory books underlines the

Ordinary Writing and Scribal Culture in Nineteenth-Century Spain: Memory Books 627

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ston

y B

rook

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

5:59

27

Oct

ober

201

4

attachment to writing of certain individuals, primarily male heads of households,

responsible for the administration of agricultural assets and for carrying out certain

professional activities which relied on the book as a useful record. Ultimately, the

memory book came to embody a personal and a family memory, assisted by the spread of

literacy which was then clearly differentiated according to gender.48

At the same time, we can see that the memory and account books of the nineteenth

century are the epigones of a writing genre which had its roots in the Middle Ages and

developed more fully in the Early Modern period, as was also true in other parts of

Europe. Whereas Catalan family books reached their apogee between the second half of

the seventeenth and the second half of the eighteenth centuries,49 the heyday of the

French livres de raison was rather in the seventeenth century, and especially between 1600

and 1650.50 In Italy, meanwhile, the importance of the libri di famiglia declined in the

course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries: they were being superseded by the

development of public (or ecclesiastical) cadastral registers, and the consolidation of other

kinds of first-person writing, like biographical and genealogical compilations and, later

on, autobiographies.51

Lastly, this study provides an insight into the way these texts evolved in their final

stages of existence, that is to say, at the moment when they began to be replaced by other

documents, genres and typologies, like accounting ledgers, memoirs or personal

autobiographies.52 The genre started to disappear as fast as traditional society transformed

itself into mass society, so that the nineteenth-century examples will come to be seen as a

bridge between personal, handwritten account books and the standardised printed forms

of the early twentieth century. It is now common to use popular printed diaries to record

income or expenses, or to make special notes on one’s health, the family, the economy or

the weather, which were so vital in traditional economies.

NOTES

This article, translated from the Spanish by Professor Martyn Lyons (University of New SouthWales, Sydney, Australia), is based on a paper presented in the workshop on ‘‘OrdinaryWritings and Scribal Culture: The History of Writing in the Nineteenth and TwentiethCenturies,’’ at the 11th International Conference of the International Society of the Study ofEuropean Ideas (ISSEI) on ‘‘Language and the Scientific Imagination,’’ University of Helsinki,Finland, 28 July–2 August 2008. It also forms part of the Research Project ‘‘Cinco siglos decartas. Escritura privada y comunicacion epistolar en Espana en la Edad Moderna yContemporanea’’ (‘‘Five Centuries of Letters: Private Writing and Epistolary Communicationin Spain during the Modern and Contemporary Age’’) (HAR2008-00874/HIST), funded bythe Ministry of Science and Innovation of the Government of Spain, and directed by ProfessorAntonio Castillo Gomez. This work has been carried out according to the ResearchAgreement endorsed by the University of Alcala and by the Gijon Council’s MunicipalFoundation for Culture, Education and the Peoples’ University.

1. Manuel Rivas, En salvaje companıa (1994) (Madrid: Alfaguara, 1998), 100–101.2. Federico Croci and Giovanni Bonfiglio, El baul de la memoria (Lima: Fondo Editorial del

Congreso del Peru, 2003).3. Philippe Artieres, ‘‘Arquivar a propria vida,’’ Estudos Historicos 21 (1998): 9– 34.

628 ANTONIO CASTILLO GOMEZ

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ston

y B

rook

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

5:59

27

Oct

ober

201

4

4. Raul Mordenti, ‘‘Scrittura della memoria e potere di scrittura (secoli XVI–XVII). Ipotesi sullascomparsa dei ‘libri di famiglia,’’ Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa. Classe di Lettere eFilosofia, ser. 3, 23.2 (1993): 741–58.

5. See Antonio Castillo Gomez et al., Bibliografıa sobre escrituras populares y cotidianas (siglosXIV–XXI) (Alcala de Henares: SIECE, 2006); (http://www.redaiep.es/pdf/publicaciones/bibliografia-escrituras-cotidianas.pdf; accessed 8.7.2011); Antonio Castillo Gomez andVeronica Sierra Blas, eds., El legado de Mnemosyne. Las escrituras del yo a traves del tiempo(Gijon: Trea, 2007).

6. On this theme, see Veronica Sierra Blas, ‘‘‘Puentes de papel’: Apuntes sobre las escrituras de laemigracion,’’ Horizontes Antropologicos 10.22 (2004): 121–47; Veronica Sierra Blas, ‘‘‘Baules dememoria’. Las escrituras personales y el fenomeno migratorio,’’ in De la Espana que emigra a laEspana que acoge. Catalogo de la Exposicion, Madrid (Fundacion Francisco Largo Caballero andObra Social Caja Duero, 2006), 157–75; Laura Martınez Martın, ‘‘Las correspondencias de laemigracion en la epoca contemporanea: una mirada historiografica,’’ Migraciones y Exilios 9(2008): 135–50; Veronica Sierra Blas and Laura Martınez Martın, ‘‘Le voyage des mots. Lettresd’emigres et secrets de famille (Espagne-L’Amerique, XIXe–XXe siecles),’’ in Les ecrits du forprive en Europe (du Moyen Age a l’epoque contemporaine). Enquetes, analyses, publications, ed. Jean-Pierre Bardet, Elisabeth Arnoul and Francois-Joseph Ruggiu (Bordeaux: Presses Universitairesde Bordeaux, 2010), 185–204.

7. For summaries of this question, see Veronica Sierra Blas, ‘‘‘Olvidos epistolares’, Luces ysombras en la epistolografıa contemporanea,’’ Revista de Historiografıa, 3.2.2 (2005) : 55–68;and Antonio Castillo Gomez, ‘‘Les ecrits du for prive en Espagne de la fin du Moyen Age al’epoque contemporaine. Bilan et perspective,’’ in Bardet, Arnoul and Ruggiu, Les ecrits du forprive, 31–47.

8. Angel G. Loureiro, coord., ‘‘La autobiografıa en la Espana contemporanea. Teorıa y analisis textual,’’Anthropos. Revista de documentacion de la cultura 125 (1991): 1–78 (special issue); Anna Caballe,Narcisos de tinta. Ensayo sobre la literatura autobiografica en lengua castellana (siglos XIX y XX)(Malaga: Megazul, 1995); Fernando Duran Lopez, Catalogo comentado de la autobiografıa espanola(siglos XVIII y XIX), (Madrid: Ollero & Ramos, 1997); Celia Fernandez Prieto and MarıaAngeles Hermosilla Alvarez, eds., Autobiografıa en Espana: un balance (Madrid: Visor Libros,2004); and Ernesto Puertas Moya, Los orıgenes de la escritura autobiografica. Genero y Modernidad(Logrono: SERVA - Universidad de La Rioja, 2004).

9. Xavier Torres Sans, Els llibres de familia de pages. Memories de pages, memories de mas (segles XVI–XVIII) (Girona: CCG edicions, 2000).

10. Carmen Rubalcaba Perez, Entre las calles vivas de las palabras. Practicas de cultura escrita en el sigloXIX (Gijon: Trea, 2006), 169–247.

11. Jordi Curbet Hereu, ed., Les llibretes de memories de Joan Serinyana (1818–1903), vinyaterllancanenc (Girona: CCG edicions, 2007).

12. Torres Sans, Els llibres de familia de pages, 111–14. A complete census of the texts would requirestudy in situ because some authors wrote several memory books, as in the cases of JoanSerinana and Lluıs M. Salvador.

13. Nicole Lemaıtre, ‘‘Les livres de raison en France (fin XIIIe–XIXe siecles),’’ Testo & Senso 7(2006): 8; See <www.testoesenso.it> (accessed 14.8.2009).

14. Clara Eugenia Nunez, La fuente de la riqueza. Educacion y desarrollo economico en la Espanacontemporanea (Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 1992), 228–50.

15. David Vincent, The Rise of Mass Literacy: Reading and Writing in Modern Europe (Cambridge:Polity Press, 2000), 9–21.

16. Nunez, La fuente de la riqueza, 91–122.17. Agustın Escolano Benito, ‘‘Los manuscritos escolares,’’ in Historia ilustrada del libro escolar en

Espana. Del Antiguo Regimen a la Segunda Republica, ed. A. Escolano (Madrid: FundacionGerman Sanchez Ruiperez, 1997), 345–71.

18. This refers to the Regulations for Public Primary School Education in this period. Cf. EstebanPaluzie y Cantalozella, Guıa del artesano. Libro que contiene los documentos de uso mas frecuente enlos negocios de la vida y 240 caracteres de letra, para facilitar a los ninos la lectura de manuscritos, tan util

Ordinary Writing and Scribal Culture in Nineteenth-Century Spain: Memory Books 629

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ston

y B

rook

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

5:59

27

Oct

ober

201

4

a toda clase de personas, (Barcelona: Hijos de Paluzie, 1913), ‘‘Objeto de esta obra.’’ Universidadde Alcala de Henares, Seminario Interdisciplinar de Estudios sobre Cultura Escrita, Archivo deEscrituras Cotidianas (UAH, SIECE, AEC), FE 1.7.

19. Jose Frances, Grafos. Segunda serie de manuscritos (Valencia: S. Mirabet, ca. 1913), 6. UAH,SIECE, AEC, FE 1.12.

20. El pobrecito hablador, 1, 17 August 1832. Cf. Mariano Jose de Larra, Figaro. Coleccion de artıculosdramaticos, literarios, polıticos y de costumbres, ed. Alejandro Perez Vidal (Barcelona: Crıtica,1997), 660–61.

21. Manuel Alberca, La escritura invisible. Testimonios sobre el diario intimo, (Oiartzun: Sendoa, 2000),14–15.

22. Francisco Ernesto Puerta Moya, Como la vida misma. Repertorio de modalidades para la escrituraautobiografica (Salamanca: Celya, 2003), 29.

23. La Roca del Valles (Barcelona), Arxiu de la Memoria Popular.24. Los ‘Quadernos’ del comerciante de la calle Peregrina don Antonio Betancourt (1796–1807), intro.

Antonio de Bethencourt Massieu, transcribed by Aurina Rodrıguez Gallardo (Las Palmas deGran Canaria: Cabildo Insular de Gran Canaria, 1996).

25. Jose Maria Alvarez Blazquez, ‘‘Memorias de un menestral curioso,’’ Museo de Pontevedra 13(1958): 61–102. Marıa Cristina of Bourbon was the widow of Ferdinand VII and supportedtheir daughter Isabella’s claim to the throne against Ferdinand’s brother Don Carlos, in theso-called Carlist Wars.

26. Curbet Hereu, ed., Les llibretes de memories de Joan Serinyana (1818–1903), vinyater llancanenc,96–97, 164–65, 198–99. I would like to thank the author for making reproductions of themanuscript available, in particular Fig. 2.

27. Antonio Castillo Gomez, Entre la pluma y la pared. Una historia social de la escritura en los siglos deOro (Madrid: Akal, 2006), 59–61.

28. Marıa Luz Mandingorra Llavata, ‘‘La configuracion de la identidad privada: diarios y libros dememorias en la Baja Edad Media,’’ in Antonio Castillo Gomez, ed., La conquista del alfabeto.Escritura y clases populares (Gijon: Trea, 2002), 131.

29. Libro de cuentas/ caja de Benito Sanz, fol. 112r-113v. UAH, SIECE, AEC, FMe 1.1, fol.112r–133v.

30. Gijon, Museo del Pueblo de Asturias (MPA), 136/5.31. Libro de caja de D. Juan Gomez Castrillon, s. fol. This book is dated 1828, but it was also used

subsequently by other family members up to 1874. Gijon, MPA, 136/4.32. Gijon, MPA, 136/5.33. UAH, SIECE, AEC, FMe 1.1. The author used both titles alternately: ‘‘Libro de cuentas

para / Benito Sanz, natural y / vecino desta villa del Cubillo. / Ano de 1831’’ (‘‘Account bookby Benito Sanz, native and resident of this small town of El Cubillo. In the year 1831’’)(fol. 108r), ‘‘Libro de caja de Benito Sanz, / vecino del Cubillo’’ (‘‘Cash book of Benito Sanz,resident of El Cubillo’’) (fol. 110v). And another note by the author: ‘‘Los hizo Benito Sanz,ano de / 1829,’’ (‘‘Benito Sanz made this, in the year 1829’’) referring to the numbers at thehead of the pages (fol. 111v).

34. UAH, SIECE, AEC, FMe 2.18.35. Gijon, MPA, 136/4.36. Madeleine Foisil, ‘‘L’ecriture du for prive,’’ in Histoire de la vie prive, v. 3, De la Renaissance aux

Lumieres, ed. Roger Chartier (gen. eds. Philippe Aries and Georges Duby) (Paris: Seuil, 1986),331–69; and Sylvie Mouysset, Papiers de famille: Introduction a l’etude des livres de raison (France,XVe–XIXe siecle) (Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2007), 113–20.

37. Albert Compte i Freixenet, ‘‘Vida rural a les terres marginals de l’Emporda, durant la primerameitat del segle XIX’’ Annals de l’Institut d’Estudis Empordanesos 26 (1993): 175–232 ; andTorres Sans, Els llibres de familia de pages, 113.

38. Rubalcaba Perez, Entre las calles vivas de las palabras, 174; MPA, 136/5, fol. 1r.39. In particular those of Policarpo Pando, covering 1712–1753, and two account books of Pedro

Jado Aguero which span the periods 1844–57 and 1878–79.

630 ANTONIO CASTILLO GOMEZ

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ston

y B

rook

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

5:59

27

Oct

ober

201

4

40. Rubalcaba Perez, Entre las calles vivas de las palabras, 173; and Rosa Marıa Blasco Martınezand Carmen Rubalcaba Perez, ‘‘Las escrituras del yo en los libros de cuentas de Pedro Jado(1844–1879),’’ in Gomez and Blas, El legado de Mnemosyne, 55–73.

41. Raul Mordenti, ‘‘Los libros de familia. Incunables del escribir sobre sı mismo,’’ Cultura Escrita& Sociedad 5 (2007): 216.

42. Santi Soler i Simon, ed., Memories d’una familia pagesa: els Anglada de Fonteta (segles XVII–XVIII)(Girona: CCG edicions, 2005).

43. Gijon, MPA, 136/5, fol. 147v.44. Angelo Cichetti and Raul Mordenti, ‘‘La scrittura dei libri di famiglia,’’ in Letteratura italiana,

vol.3, Le forme del testo, tome 2, La prosa, ed. Alberto Asor Rosa (Turin: Einaudi, 1984), 1149–50; Raul Mordenti, I libri di famiglia in Italia, 2, Geografia e storia (Rome: Edizioni di Storia eLetteratura, 2001); and his ‘‘Les livres de famille en Italie,’’ Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales59.4 (2004): 785–804.

45. Antoni Pladevall i Antoni Simon, eds., Guerra y vida pagesa a la Catalunya del segle XVII(Barcelona: Curial, 1986), 31–120.

46. Apart from works cited elsewhere in these notes, see also for the Spanish case Antonio CastilloGomez, ed., Cultura escrita y clases subalternas: Una mirada espanola (Oiartzun: Sendoa, 2001);and for its pedagogical potential, Veronica Sierra Blas, dir., Laura Martınez Martın and JoseIgnacio Monteagudo, eds., Esos papeles tan llenos de vida... Materiales para el estudio y edicion dedocumentos personales, (Girona: CCG Edicions, 2009).

47. Walter Ong, Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word (London: Methuen, 1982).48. According to the 1900 population census, the illiteracy rate for young men over 10 was 47%,

whereas for women it rose to 69%. Cf. Mercedes Vilanova Ribas y Xavier Moreno Julia, Atlasde la evolucion del analfabetismo en Espana de 1887 a 1981 (Madrid: Ministerio de Educacion yCiencia, 1992), 166.

49. Torres Sans, Els llibres de familia de pages, 27.50. Jean Tricard, ‘‘Les livres de raison francais au miroir des livres de famille italiens: pour relancer

une enquete,’’ Revue historique 624 (2002): 1008.51. Mordenti, ‘‘Los libros de familia,’’ 220; this does not of course rule out the existence of later

family books, for which see, among others, Simona Foa, ed., Le ‘Croniche’ della famiglia Citone,transcribed and translated from Hebrew by Alberto A. Piattelli, with preface by GiuseppeSermoneta (Rome: Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura, 1988); and Marilisa Cucculelli, La memoriae l’alfabeto. Il ‘libro di ricordi’ di Rinaldo Cosme (Ascoli Piceno, 1822–1844) (Turin: Scriptorium,1996).

52. Torres Sans, Els llibres de familia de pages, 29.

Ordinary Writing and Scribal Culture in Nineteenth-Century Spain: Memory Books 631

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ston

y B

rook

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

5:59

27

Oct

ober

201

4