THE RISE OF TOTALITARIAN STATES THE BOLSHEVIK REVOLUTION AND THE CREATION OF THE SOVIET UNION.

ON THE THIRD FRONT: THE SOVIET MUSEUM AND ITS PUBLIC DURING THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION

Transcript of ON THE THIRD FRONT: THE SOVIET MUSEUM AND ITS PUBLIC DURING THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION

-

7/29/2019 ON THE THIRD FRONT: THE SOVIET MUSEUM AND ITS PUBLIC DURING THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION

1/18

KONSTANTIN AKINSHA (Washington, DC, USA)ADAM JOLLES (Tallahassee, FL, USA)

ON THE THIRD FRONT: THE SOVIET

MUSEUM AND ITS PUBLIC DURING

THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION

In 1928, two Russian satirists, II'ia Il'f and Evgenii Petrov, published a

picaresque adventure-drama destined to become one of the most popular

novels of the Cultural Revolution. The plot o f their novel, The Twelve Chairs,

concerns a desperate race to locate a missing fortune in jewels rumored to be

hidden in the seat of one of twelve upholstered chairs confiscated during the

revolution from the family of one of the protagonists, the former nobleman

Ippolit Matveevich Vorob'ianinov. Working in tandem with Ostap Bender, a

young miscreant looking to make some fast money, Vorob'ianinov traces the

itinerary of the chairs to the Moscow Museum of Furniture. Expecting to fmd

them on display, the protagonists learn much to their dismay that the chairs

had been recently de-accessioned by the curatorial staff, and will be auc-

tioned off as objects lacking in "museum value" (muzeinaia tsennost1).1I

A thinly disguised critique of the deplorable state of Soviet museums at

the demise of the New Economic Policy, The Twelve Chairs was written dur-

ing a period that witnessed the rapid transformation of the state-owned mu-

seum in relation to a newly emerging Soviet society. Following the October

Revolution, the majority of Soviet museums had been asked to preserve and

display those cultural properties that had only recently come under their pur-view, whether objects confiscated from the imperial family itself or, as in the

case of the twelve chairs that formerly belonged to the Vorob'ianinov family,

materials consolidated from various collections of wealthy landowners and

merchants. During the years of War Communism (1918-21) and the New

Economic Policy (1921-28), the Soviet museum would evolve from an ex-

perimental novelty into a full-blown federation of institutions under the lib-

eral leadership of Anatolii Lunacharskii, the People's Commissar of Enlight-

enment. Dozens of city palaces and hundreds of country estates belonging to

1. Ilya Ilf and Yevgeny Petrov, The Complete Adventures of Ostap Bender; Consisting of the

Two Novels: The Twelve Chairs and the Golden Calf, trans. by John H. C. Richardson (New

York: Random House, 1961), p. 166. ll'ia II'f was a pseudonym of II'ia Fainzil'berg, Evgenii

Petrov a pseudonym of Evgenii Kataev.

-

7/29/2019 ON THE THIRD FRONT: THE SOVIET MUSEUM AND ITS PUBLIC DURING THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION

2/18

members of the nobility and upper-middle class were transformed virtually

overnight into a form of public institution that came to be identified as the"palace-museum" (dvorets-muzei).

According to Aleksei Fedorov-Davydov, a leading curator at the State

Tret'iakov Gallery in Moscow and one of the most vocal supporters o f mu-

seum reform at the time, such administrative activity had been absolutely

necessary following the revolution:

By itself the preponderance of the tasks o f collection and preservation

during the first years o f the revolution was natural and healthy. Life i tsel f

demanded it: we had to use all [our] forces for registering and gathering

together abandoned and nationalized art. Many museums were over-

stocked with the mass of art valuables that arrived and ended up looking

l i k e b i g w a r e h o u s e s . 22

This preservationist effort had been broadly supported by both intellectu-

als and representatives of the artistic community, despite the fact that neither

necessarily sympathized with the stated goals o f the revolutionaries. Many

members o f the educated class simply regarded the new public museum as a

place in which to take refuge from the harsh realities of everyday revolution-

ary life. Abram Efros, for one, a successful art critic both before and after the

revolution, described the fate of Petrograd intellectuals whose homes and

possessions had been confiscated by the state, but who were now enjoying all

the benefits o f their pre-revolutionary lifestyles in their new jobs as state mu-seum officials:

Revolution destroyed the man from Petersburg as a collector, but pre-served him as a museum worker. It moved his collection from his house

to the State museum. He moved there in its wake as a kind of peculiar

addition to it . . . now he extends the feeling of private property to the

whole museum: the Hermitage is his museum, Gatchina is his palace,

and the whole of Petersburg is his city.3

Nevertheless, despite the sudden proliferation of public museums

throughout Russia following the revolution, the museum pub li c - a com-

pletely new national entity - was thoroughly unprepared for what would be

expected of it.

2. Aleksei Fedorov-Davydov, Sovetskii khudozhestvennyi muzei (Moscow: OGIZ-IZOGIZ,

1933), p. 23.

3. Abram Efros, "Peterburgskoe i moskovskoe sobiratel'stvo," Sredi kollektsionerov, 4

(192 1), ), p. 15.

-

7/29/2019 ON THE THIRD FRONT: THE SOVIET MUSEUM AND ITS PUBLIC DURING THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION

3/18

The authors of The Twelve Chairs keenly observed that a type o f museum

visitor peculiar to Russia was becoming increasingly evident - the largely

uneducated viewer attracted only to the material aspects of museums. Thisfigure, who had only jus t come into being in Russia with the creation of the

public museum, tended to perceive museums as opulent repositories of uni-

maginable decadence:

There is a special group o f people in Moscow who know nothing

about art, who are not interested in architecture, and who do not like his-

torical monuments. These people visit museums solely because they are

housed in splendid buildings. These people stroll through the dazzling

rooms, look enviously at the frescoes, touch the things they are requested

not to touch, and mutter continually:

"My, how they used to live!" ,

They are not concerned with the fact that the murals were painted by

the Frenchman Puvis de Chavannes. They are concerned only with how

much they cost the former owner of the house. They go up staircases

with marble statues on the landings and try to imagine how many foot-men used to stand there, what wages were paid to them, and how much

they received in t i p s . . . . In the oak-paneled dining-room they do not ex-

amine the wonderful carving. They are troubled by one thought: what theformer merchant-owner used to eat there and how much would it cost at

present prices?4

While Il'f and Petrov dismissed such fetishistic reactions as provincial, a

significant number of theircontemporaries in the art world held the museums

and especially their administrators responsible for failing to develop a suffi-ciently rigorous expository model to educate their public properly about the

cultural history of class warfare.

Following Stalin 's consolidation of power during the Cultural Revolution

(1928-1931) and extending throughout the period of the first Five-Year Plan

(1928-1932), the museum as a public institution was subject to intense scru-

tiny from the radical left. This effort to bring contemporary Socialist cultural

criticism to bear on museology gave rise to considerable debate over the

function of the museum in the new Soviet society and the correct manner of

bringing the museum into line with the cultural goals of the current admini-

stration. I f the Soviet arts administration during the NEP period had been

most concerned with preserving objects and establishing public collections o f

4. Ilf and Petrov, The Complete Adventures of Ostop Bender, pp. 156-57.

-

7/29/2019 ON THE THIRD FRONT: THE SOVIET MUSEUM AND ITS PUBLIC DURING THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION

4/18

exemplary aesthetic value, Soviet museums during the Cultural Revolution

became first and foremost pedagogical and propagandistic vehicles for the

State, an aspect that was evident both in the emergence of new, text-heavy

modes of exposition, as well as in the leveling of collections in an effort to

introduce balance and uniformity. By 1930, at the First All-Russian Congress

of Museum Workers in Moscow, a consistent although by no means un-

equivocal museological platform was presented to the public, thereby mark-

ing the official end of the preservationist policy that had governed museum

administration during the prior decade.

On the eve of the Cultural Revolution, a new generation of radical Marx-

ist curators unleashed a broad campaign accusing their predecessors in the

museums of fixating on the objects under their purview at the expense of

the audience for which they were responsible. Fedorov-Davydov, for exam-

ple, associated the materialistic form of collecting practiced by the palace-

museums and their first curators with "object-fetishism" (veshchnyi fe t-

ishizm). Rather than designing a model that would serve the museum's

pedagogical goals, he writes: "The ideology of collecting based on object-

fetishism and the bourgeois feeling of property was demonstrated strikingly

in the tendency to transform every palace, country estate and monastery into

a separate museum."55

This new wave of criticism was by no means limited to the curatorial

community. In 1929 Lunacharskii h imself was pilloried on the pages of

Daesh (Give), a journal close to the radical October group and directly

committed to realizing the goals o f the First Five-Year Plan. An anonymous

poem published therein accuses Narkompros in general (and Lunacharskii

in particular) of protecting unneeded country estates by turning them into

museums. In the style of political denunciation that was swiftly becoming

de rigueur, the poem denigrates him as a "Soviet Maecenas," finding him

guilty not only of preserving the past but of appointing former nobles ando t h e r c l a s s e n e m i e s a s c u s t o d i a n s o f t h e p a l a c e - m u s e u m s . 66

Perhaps not surprisingly, the substantial quantity of palace-museums soon

gave rise to the problem o f how to administer such institutions. According to

the radical curators, the palace-museums were ripe for reinstallation precisely

because their current exhibitions addressed only the material splendor of

Russia's feudal past. They failed to consider - and did nothing at all to ex-

plain to their audiences - the class origins of the forms for which they were

responsible. It is this shortcoming to which II'f and Petrov allude indirectly in

offering the conventional proletarian response to the art of the preceding ep-

och ("My, how they used to live!").

5. Fedorov-Davydov, Sovetskii khudozhestvennyi muzei, p. 25.

6. "Velika li tsena-to nashim metsenatam?," Daesh, 8 (1929), p. 12.

-

7/29/2019 ON THE THIRD FRONT: THE SOVIET MUSEUM AND ITS PUBLIC DURING THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION

5/18

Two young curators from Leningrad, Semen Geichenko and Anatolii

Shemanskii, pioneered the revision of the palace-museums, starting work on

the reinstallation of the Gatchina Palace and parts of the Peterhof PalaceComplex in 1927. They were the first to mount slogans and so-called "visual

installations" (izo-ustanovki) in the public museum. For Geichenko and She-

manskii the palaces and their contents were best treated as nothing more than

"historic documents of everyday life" (istoriko-bytovoi dokument), an ap-

proach that would by extension transform them into "revolutionary muse-

ums" (revolutsionnye muzei).' As would soon be the case with other young

Marxist curators working throughout the Republic, Geichenko and She-

manskii employed in their installations the principle of cinematic montage

developed earlier by avant-garde filmmakers.8 In the personal rooms of Nico-

las I in the Gatchina Palace, for example, they mounted a slogan that pro-

claimed, "He handicapped Russia for thirty years," adjacent to dozens of of-

ficial portraits of the tsar suspended from the wall at different angles.9 ,

Geichenko and Shemanskii's experimental installations were soon imi-

tated throughout the major museums of Moscow and Leningrad, many of

whose curators at least initially mistakenly perceived the beginning of the

Cultural Revolution as a return to the ideals of War Communism, believing

the retreat of NEP to be finished. In reality, the Cultural Revolution wouldmanifest itself in the halls of the public museum not so much through formal

experimentation as in a new, more ideologically rigorous model of exposi-

tion. Grounded in the propagandistic presentation of objects, heavily medi-

ated by text, this model would be stressed by the well-known Leningrad art

historian Fedor Shmit in his major 1929 study Museum Work: Questions of

Exposition. Shmit argued that the most effective form o f propaganda would

be completely hidden from view:

From the state point of view museums either should not exist at all or

should be socio-educational institutions willingly attended by people be-

cause they are "interested" . . . and can be educated in a direction desir-

able for the state without noticing it.'o

7. Anatolii Shemanskii and Semen Geichenko, Poslednie Romanovy v Petergofe. Putevoditel'

po nizhnei dache i vagonam (Moscow-Leningrad: Gos. lzd. izobrazitel'nykh iskusstv, 1933), p.4.

8. The influence of avant-garde film montage on the Marxist curators is described in Fe-

dorov-Davydov, Sovetskii khudozhestvennyi muzei, pp. 60-61.

9. Gichrrye komnaty Nikolaia L Gatchina (Leningrad: OGIZ, 1928). Postcard in the authors'collection.

10. Fedor Shmit, Muzeinoe delo. Voprosy ekspozitsii (Leningrad: Academiia, 1929), p. 82;

see also Theodore Schmit, "Les Musdes de 1'Union des Rpubliques Socialistes Sovietiques,"

Les Cahiers de la Rpublique des lettres, des sciences et des arts, 13 (1931), pp. 206-21.1.

-

7/29/2019 ON THE THIRD FRONT: THE SOVIET MUSEUM AND ITS PUBLIC DURING THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION

6/18

The next year, the Tret' iakov Gallery in Moscow was the site of the "Ex-

hibition of Revolutionary and Soviet Thematics" in which Fedorov-Davydov

attempted to introduce subtle forms o f persuasive propaganda, whose pres-

ence was intended to assist in advancing the claims of the exposition. In addi-

tion to mounting political slogans alongside paintings drawn from the mu-

seum's permanent collection, he installed such novel supplementary materials

as photographs and film stills, whose presence was intended to reinforce theclaims of the exhibi tion."IT

At least initially, this freedom to experiment in the realm of the propagan-distic exhibition seems to have led some museum curators to include uncon-

ventional materials in their installations and to abandon the structure and de-sign of the traditional, aesthet icized art exhibition. In 1930, for example, the

State Russian Museum in Leningrad organized an exhibition of "War and

Art," going so far as to recreate trenches in one hall, frame battle paintings in

barbed wire and gas masks, and project a rotating selection of slides, includ-

ing images of St. George and military propaganda posters depicting Russian

Cossacks impaling German soldiers. 12 By the beginning o f 1930, however,

the radical Marxist curatorial community had begun to express serious reser-

vations about the effectiveness of experimenting with exhibition design and

incorporating unconventional materials into the permanent galleries of the

public museum. Neither practice was considered appropriate and they were

shortly expunged altogether. Numerous apologists for incorporating everyday

objects into museum galleries suddenly found themselves accused of defend-

ing formalism (the history of style without any discursive Marxist exposition

of form). Within short order, experimental display practices came to be re-

garded as best reserved for temporary exhibitions, as demonstrated in two

important such installations that year: Aleksandr Rodchenko's "Anti-Pope"

exhibition in the Moscow Planetarium'3 and the "Imperialist War" exhibitionin the Gor'kii Park o f Culture and Rest (Moscow). 14

The failure of radical experimental display practices pointed to the rising

need among Soviet curators to establish more firmly an ideological underpin-

ning to their expositions. For most o f the previous century, museums across

the West had privileged nationality, chronology and the biography of the art-

ist (in descending order o f importance) as the essential criteria through which

to make sense of the history of art. By the late 1920s, this expository model

11. A. Grech, "Exhib itions of Revolut ionary and Soviet Themat ics," VOKS, 6-7 (1930), pp.

71-78.

12. Fedorov-Davydov, Sovetskii khudozhestvennyi muzei, p. 62.

13. Anna Karavaeva, "Ob odnoi poleznoi vystavke. Iz dnevnika pisatelia," Literaturnaia ga-

zeta, no. 22, June 2, 1930.

14. Fedorov-Davydov, Sovetskii khudozhestvennyi muzei, p. 61.

-

7/29/2019 ON THE THIRD FRONT: THE SOVIET MUSEUM AND ITS PUBLIC DURING THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION

7/18

had come to be perceived in the Soviet Union as a function of bourgeois ide-

ology, hostile in other words to the interests o f the proletariat. During the pe-

riod of the Cultural Revolution, Soviet curators explored several alternativeexpository models for making their arguments more ideologically transpar-ent. Each of these models had in common the de-sacralization of the museum

object. The expository paradigm that emerged from this period o f crisis as the

preferred means of presenting the history of art as the reflection of class

struggle came to be known as the "complex Marxist exposition" (komplek-

snaia marksistskaia ekspozitsiia).ls

The single most important expository transformation during this period

was the privileging of text over image, the grand narrative that would govern

the sequence of objects in each installation. The reign o f the discursive would

be evident in the dominating text panels that came to be ubiquitous in instal-

lations across the Soviet Union. Equally important was the policy o f transfer-

ring objects among museums in order to balance collections. Those museums

unable to procure examples of the period styles they needed for their juxtapo-

sitions opted willingly for copies and reproductions; those curators found

guilty of overvaluing the originality and uniqueness of objects in their collec-

tions were subject to scathing critique. Related to this desire to establish bal-

anced historical installations was a trenchant resistance to maintaining collec-tions exclusively devoted to media historically favored by the ruling classes

(furniture, porcelain, etc.). Finally, certain curators pushed to introduce ex-

amples of proletarian art into their galleries, arguing that the juxtaposition o f

art by different classes would make eminently clear the cultural history of

their struggle.

The predominance o f text is evident in its presence in virtually every as-

pect of the Marxist exposition: catalogues of all types abounded and slogans

of all sorts appeared in different configurations above and adjacent to the ob-

jects on display. In such installations, art was typically relegated to the role of

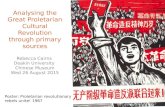

illustration, with text providing the narrative. In Kiev in 1931, for example,

Sergei Gil'iarov, the curator of the Museum of the Ukrainian Academy of

Science, reinstalled the museum's permanent collection according to this new

museological model (Figs. 1-2). Gil'iarov's exposition was deprived of suchcreative constructivist elements as visual installations and reduced to the use

of slogans and wall labels explaining the class character o f the exhibited

paintings. 16 Such privileging of text speaks undoubtedly to a pervasive

15. A. Fedorov-Davydov, "Nekotorye voprosy rekonstruktsii Tret'iakovskoi galerei," in Sov-

etskii muzei. Bulleten' Gosudarstvennoi Tret'iakovskoi galerei i Gosudarstvennogo Muzeia no-

vogo zapadnogo iskusstva (Moscow: Izd. Gos. Tret'iakovskoi galerei, 1930), pp. 6-10.

16. By the time the installation was organized the museum had already lost to Gostorg such

masterpieces as Adam and Eve by Lucas Cranach the Elder and a French tapestry of The Adora-tion of the Magi, dated 1512.

-

7/29/2019 ON THE THIRD FRONT: THE SOVIET MUSEUM AND ITS PUBLIC DURING THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION

8/18

-

7/29/2019 ON THE THIRD FRONT: THE SOVIET MUSEUM AND ITS PUBLIC DURING THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION

9/18

They do not want and cannot understand that the most striking painting,

vase, sculpture, drawing has no value for this museum if it is unique, if

there are no other objects from the same epoch, in the same style, and

that such pieces must be transferred to other museums. "Feudalism," the

system of "isolated economy" is reigning in museums. Each museum

thinks only about itself, preserves pieces only for itself, clings to every

object that it knows to be rare, and equates the transfer of such objects to

another museum as a fate equal to their destruction. Until today, rarities

have been more important to museums than the meaning and tasks ofmuseum work. 18

For the radical Marxists, however, such institutions as the Ostroukhov col-

lection, the Tsvetkov Gallery, or the Shchukin and Morozov museums - all

museums formed from private collections - were little more than anachronis-

tic monuments to the idea of the bourgeois collector and his particular

tastes.'9 The new generation had no interest in maintaining the historic unity

of the great Russian private collections; by contrast, they privileged above all

the master Marxist narratives they sought to install in their respective muse-

ums. By the early 1930s, the transfer of objects among museums had become

fairly commonplace as a practice. Wriat had previously been perceived as anunassailable museological entity - the historic collection shaped by an indi-

vidual temperament - had been swiftly and mercilessly dismantled.

Marxist curators faced not only the problem of enriching the collections of

the museums for which they were responsible. They often fought as well to

diminish the vast and overwhelming quantity of objects that had been acces-

sioned by their museums. This concern was voiced especially among radical

curators at the palace-museums and estate-museums, which had been the re-

cipients of excessive quantities of all sorts of materials, from painting and

sculpture to the applied arts. This surfeit, they complained, was in turn giving

rise to an experience among museum visitors that bordered on aesthetic rap-

ture. At the 1930 Congress o f Museum Workers, this concern with the sur-

plus quantity of art objects in the palace-museums was addressed in the form

of a directive to begin diminishing collections:

The elevated position (of works of art in the palace-museums) has to

be re du ce d . .. by the substantial addition of clearly historical material,

by the removal of all artworks not needed by that particular museum (inits function) as a museum of the history o f everyday life. Artistic ensem-

bles (buildings, parks, interiors) do not have the utmost importance.

18. Fedorov-Davydov, Sovetskii khudozhestvennyi muzei, p. 29.

19. Ibid., pp. 24-25.

-

7/29/2019 ON THE THIRD FRONT: THE SOVIET MUSEUM AND ITS PUBLIC DURING THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION

10/18

They must be used as a moment (an element) in the exposition specifi-

cally to demonstrate the parasitic existence of the aristocracy, (to demon-strate) the role of art in creating an aesthetic pedestal and a barrier be-

tween the ruling group and the masses, in creating the eternal feast but

not the real everyday life of the epoch. Any other demonstration will turn

into an excessive aesthetic apologia for serfdom (and will) hide the eco-

nomic roots of the beastly essence of its exploitation. 20

Described thus as an impediment to the proper mission of the museum, the

glut of materials in public collections would henceforth be addressed by fa-

cilitating loans, exchanges, or simply direct transfers of objects among insti-tutions.

In much the same spirit, those curators who suffered from a lack of suffi-

cient materials and who were unable to obtain specific objects to complete

their historical narratives were encouraged to enhance their installations by

using surrogates. Their exhibitions would include plaster copies and repro-

ductions (typically photographs or prints) of those objects they were not able

to obtain by transfer or exchange. As Fedorov-Davydov argued at the 1930

Congress of Museum Workers, "Because the central task of the art museum

is to demonstrate the processes of art and not separate objects, it can and must

use reproductions and plaster copies together with originals when neces-

sary."21 Maintaining the integrity and coherence of the historical narrative

was clearly more of a priority than honoring the aura of the original object.

For some curators, the key issue was not so much the privileging of ob-

jects as the privileging of certain kinds of objects. Kovalenskaia, who had

helped design the "First Experimental Marxist Exposition" at the Tret'iakov

Gallery in 1929, was one such curator, objecting specifically to the way in

which museums had traditionally privileged those media historically sup-ported by the ruling classes. In gi vi ng preference to easel painting and

monumental, representational sculpture, she observed, museums were ignor-

ing the "art of the oppressed classes," whatever form it might have taken

throughout the ages. She thus proposed bringing the two into direct contactwith one another in order to illuminate class contradictions:

It is necessary to include the art of the lower classes, which until now

has not been researched and in general has not been treated like art and

has been collected only by museums of everyday life.... By contrastingsuch art with the art of the upper classes we are able to show class con-

20. Pervyi Vserossiiskii muzeinyi s'ezd Tezisy dokladov (Leningrad: Leningradskii oblastnoi

otdel' Soiuza rabotnikov prosveshcheniia. Muzeinaia komissiia, 1930), p. 49.

21. Ibid., p. 53.

-

7/29/2019 ON THE THIRD FRONT: THE SOVIET MUSEUM AND ITS PUBLIC DURING THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION

11/18

tradictions visually and to demonstrate class struggle sharply. Displaying

such material in museums is necessary even for the purpose of destroy-

ing the legend o f the coherent flow of the nation's art, a legend that sup-ports the classless understanding of art. 22

This kind of visual juxtaposition, through which the history of style was

interpreted as a reflection of the history of class struggle, retained traces of

the formalist models from which it was derived. Fedorov-Davydov, one of its

most prominent proponents, explained that he had arrived at this model of

comparative exposition by merging contemporary Marxist theory with the

art-historical methodology of Heinrich Wolfflin and certain figures from the

Vienna School. 23In their sensitivity to secondary media, the radical curators were following

in the footsteps of Wilhelm von Bode, the legendary curator of the Kaiser-

Friedrich-Museum in Berlin, who some thirty years earlier had sought to in-

stall applied art and furniture alongside representational art in his installa-

tions .24 Unlike Bode, however, they sharply rejected the possibili ty that cer-

tain types of applied art might on their own reveal the class history of form.

One of the museums most commonly derided for failing to develop balanced

collections was the Moscow Museum of Furniture, which had been subject to

such condescension by Il'f and Petrov. As Federov-Davydov argued, the mu-

seum embodied the concept o f the fetishistic ideology of collectors, accord-

ing to which the class history of form is not revealed:

Two museums of applied arts were formed, separated according to

types o f material: the Museum of Porcelain and the Museum of Furni-

ture. These two museums were the apogee of formalist creativity and the

bourgeois-fetishistic ideology o f collectors. Their collections were sorted

in a formalist-descriptive way, according to countries, periods and pro-d u c e r s . . . . By the very nature of their collections these museums were

deprived of the possibility o f showing the history o f art as the change

and the struggle of class ideologies.25

The new Marxist expositions would thus necessarily incorporate a wide

range of media and would do so with an eye not jus t to elucidating the evolu-

22. Kovalenskaia, Putevoditel' po opytnoi kompleksnoi marksistskoi ekspozitsii, p. 4.

23. Fedorov-Davydov, "Nekotorye voprosy rekonstruktsii Tret'iakovskoi galerei," pp. 6-10.

24. Wilhelm von Bode, Museumsdirektor und M6zen: Wilhelm von Bode zum 150. Geburt-

stag der Kaiser-Friedrich-Museums-Verein (Berlin: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, 1995).

25. Fedorov-Davydov, Sovetskii khudozhestvennyi muzei, pp. 35-36.

-

7/29/2019 ON THE THIRD FRONT: THE SOVIET MUSEUM AND ITS PUBLIC DURING THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION

12/18

tion of style, but to determining how those media had been favored histori-

cally by one class or another.As the state transformed its museums into weapons of ideological strug-

gle, it sought out new means to practice effective political indoctrination.

From 1927 the leading Soviet museums created specialized internal depart-

ments that would be responsible for both museum education and statistical

investigations into the preferences and demographics of their constituents.

We might construe such research and practices as an early form of political

profiling, which would in turn help the museums develop more sophisticated

and increasingly refined forms o f propaganda. Statistical surveys show that

from the beginning of the First Five-Year Plan the composition of museum

visitors was changing rapidly. Increasingly, the museum audience was com-

prised of urban workers and proletarians, Red Army soldiers and Soviet offi-

cials. The number of rural peasants visiting museums remained miniscule andno effort was made to address this lack.26

Many of the major museums organized specialized guided tours through

their collections during'this period, in part to address particular interest

groups. In 1927, for example, the Tret'iakov developed a series of excursions

through its permanent galleries, the itineraries of which were very carefully

orchestrated: "The Lives of Different Classes before the Revolution"; "The

Life of the Se rf in His Envi ronment"; "Merchants, Workers, Peasants"; "Eve-

ryday Life and the Development of Industrial Forms"; "The Reflection of

Capitalist Formations in Painting and Sculpture"; "Religion in the Service ofthe Tsarist Government. ,,27 The sudden arrival at the doors of the museum of

great quantities of uneducated masses made for some interesting and unan-

ticipated results. Workers and soldiers perceived the art hanging on the walls

of the museum to be illustrations of Tsarist Russia's dark and sordid past. Af-

ter visiting the Tret'iakov Gallery, for example, the workers in the bakery ofthe main political department of the secret police (OGPU) wrote that they

greatly enjoyed the tour, which helped them to understand the past, and that

anybody wanting to know how difficult life had been under the tsars need

only visit the museum.28 Statistical research undertaken by the museum indi-

cates that ninety-eight percent of its visitors were interested in nineteenth-

century realist art; by contrast virtually none mentioned either religious icons

or modern art. This passion for narrative painting was apparent in the unri-

v a l e d p o p u l a r i t y o f I l ' i a R e p i n ' s I v a n t h e T e r r i b l e K i l l i n g h i s S o n ( 1 8 8 5 ) . 2 9

26. A. Moizes. "Ekskursionnaia zhizn' Tret'iakovskoi galerei," in Izuchenie muzeinogo zrite-

lia (Moscow: lzd. Gos. Tret'iakovskoi galerei, 1928), p. 19.

27. Ibid., p. 19.

28. Ibid., p. 26.

29Ibid., pp. 20-23.

-

7/29/2019 ON THE THIRD FRONT: THE SOVIET MUSEUM AND ITS PUBLIC DURING THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION

13/18

The museum reform movement was officially institutionalized during the

1930 Congress of Museum Workers. By this year, the preservationist ap-

proach to museology had clearly fallen out of favor in the upper ranks of So-

viet cultural administration in favor of a model that privileged ideological in-

terpretation. Andrei Bubnov, who had succeeded Lunacharskii the previous

year in the role of People's Commissar of Enlightenment, delivered a speech

via proxy that made eminently clear the administration's position. In contrast

to his predecessor, Bubnov could hardly be accused of soft liberalism. His

speech, relentless and unapologetic, effectively implicated the earlier genera-

tion of museum curators - those objecting to the new ideological museology

- in undermining the state, a rhetorical gesture popularized by Stalin in link-ing class struggle to the construction o f Socialism:

Class resistance of the elements hostile to Socialism found its reflec-

tion in this zone of cultural building. A certain number o f museum offir

cials are resisting reorganizing museums according to the new model.

This is provoking to a considerable extent the question about museumcadres.3o

The People's Commissar further announced the beginning of a campaignto purge museums of those curators who still persisted in clinging to the ob-

ject-oriented museological model preferred by the West: "We don't need a

museum-Kunstkammer. We must destroy reactionary slavery to routine in the

construction of museums."3' After 1930, the metaphor preferred by the Marx-ist curators to describe their activities was that of the "Third Front." As She-

manskii and Geichenko wrote:

Now the working class, which prevailed on the political and industrial

fronts, is realizing the tasks of the third front - the cultural one. It studies

to understand the past and to consciously lay the foundation of a new so-

c i a l i s t s y s t e m u s i n g t h i s u n d e r s t a n d i n g . 3 2 -

If the "first front" was that of political struggle, and the second that o f in-

dustrialization, then the trenches of the third front were to be found in the

museum halls. This was the front o f Cultural Revolution. Such an application

of militaristic rhetoric was typical o f official party documents o f the time and

extended readily to decrees on the subject o f museum reform, which in many

30. Andrei Bubnov, 0 muzeiakh. Privetstvie i rech' na 1-m Muzeinom s"ezde (Moscow-

Leningrad: Narodnyi kommisariat prosveshcheniia RSFSR, 193 1), ), p. 5.

31. Ibid., p. 5.

32. Shemanskii and Geichenko, Poslednie Romanovy v Petergofe, pp. 6-7.

-

7/29/2019 ON THE THIRD FRONT: THE SOVIET MUSEUM AND ITS PUBLIC DURING THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION

14/18

ways lead to the destruction of the last ideologically hostile representatives of

the interwar intelligentsia. The casualties of this campaign, however, were

not only the old generation of museum curators, those seeking only to pre-

serve the objects in their collections. They included as well thousands of

works o f art sold abroad by Gostorg, the State Department o f Trade.

To a great extent, the museum reform movement o f the Cultural Revolu-

tion facilitated the sale of art from Russian collections. Museum objects had

already been deprived of an aura o f indispensability, having been deemed re-

producible or replaceable through surrogate copies. Indeed, the unique work

of art had come to be regarded as inexpedient precisely because Marxist in-

stallations avoided discussion of distinctiveness and idiosyncrasy wheneverpossible. Conversely, one can argue that the sales even helped realize the

dream o f the radical Marxist curators, in drastically diminishing the quantity

of art objects with which they had to concern themselves in the palace-museums.

Those who opposed the sales soon found themselves politically marginal-

ized, and were given no outlet through which to voice their objections. Nev-

ertheless, the connection between the museum reform movement and the se-

cret sales did not go unnoticed. Panteleimon Romanov mentioned it obliquely

in his dramatic novel, Three Pairs of Silk Stockings: A Novel of the Life of theEducated Class under the Soviet, published in two parts in 1931. Romanov'ss

story brilliantly addresses the rising tension between those curators of an

older generation who devoted themselves to preserving and cataloguing ob-

jects and those administrators of the new regime charged with bringing the

museum into line with the goals o f the Cultural Revolution. Set in Moscow,

in the early years of the First Five-Year Plan, the story unfolds in an ambigu-

ous civic institution referred to only as the Central Museum.

For Romanov, this generational tension cannot be separated from the class

conflict endemic to the period. The museum's curatorial staff, all educated

members of the intelligentsia, find themselves at the mercy of a newly-

appointed director, Andrei Zakharovich Polukhin, a university-trained mem-

ber of the working class dedicated to bringing the street (that is to say, Com-

munist scouts and workers) into the museum. Polukhin - who sports a stern

and unblinking glass eye that strikes fear into the hearts of his staff - makes

clear his intention to make curatorial science immediately available to the

working class, to make the museum "useful," in a word, by having exhibits

that "show the road on which we have advanced and on which we are nowadvancing."33 Much to the chagrin of his curators, he speaks contemptuously

33. Panteleimon Romanof, Three Pairs of Silk Stockings: A Novel of the Life of the Educated

Class under the Soviet, trans. by Leonard Zarine (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 193 1), p.109.

-

7/29/2019 ON THE THIRD FRONT: THE SOVIET MUSEUM AND ITS PUBLIC DURING THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION

15/18

of the Central Muse um' s collection, dismissing a precious bed and several

helmets formerly belonging to Tsar Nicolas I as mere "relics" and "dead

things."34At one point, while walking home from work with his chief curator and

confidant, Ippolit Grigorevich Kisliakov, the director stands admiringly be-

fore a series of massive construction sites, bemoaning the fact that while the

signs and symbols o f the new Russia rise from the ruins o f the old, he is re-

duced to "protecting tombstones and tsars' beds."35 While his curators insist

on carefully documenting the objects under their purview, Polukhin's ultra-

leftist view of history, hardly a rarity among members of his generation,

places singular importance on the revolution, by extension diminishing the

status of everything that preceded it:

The various articles and exhibits [in the museum] only had value in

his eyes according to the extent to which they reflected the revolutionary

process: the extent to which they were essential to the revolution. To him

past history was merely a prologue to the revolution, or, more rightly,

s o m e t h i n g t h a t h a d i m p e d e d i t .36

Regarding his collection with a mixture of "indifference and almost ani-mosity," Polukhin has no reservations about selling off objects that would

bring badly needed food and materials to his countrymen. Indeed, the art of

the pre-revolutionary period for him seems little more than a fossil from a by-

gone era, a species of object that no longer has a place in society, much less a

public museum:

"These foreigners - what good have they been to us?" he once said to

Kisliakov. "Take this clever painter, I am told they will give money for

his works abroad."

"Which clever painter?" _"The one in the comer hall."

"Rembraridt?"

"Yes, but what use is he to us? I don't understand him. Pictures are all

the same. Neither will the workers understand.... Such things may be

appreciated, perhaps by about a hundred people throughout the whole of

the Soviet Union. Of what importance is it that they understand? . . . You

must realize that we are working away from these Old Masters, not to-

wards them. Perhaps art will now follow quite a different course and if

34. Ibid , pp. 72 and 109 respectively.

35. Ibid., p. 157.

36. Ibid, p. 236.

-

7/29/2019 ON THE THIRD FRONT: THE SOVIET MUSEUM AND ITS PUBLIC DURING THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION

16/18

we try to learn from these (pictures) we shall only get confused.... We

have now to think about food and machines. I f they will give us machin-

e r y f o r t h e s e p i c t u r e s , t h e n w e m u s t u s e t h e o p p o r t u n i t y . " 3 7

Polukhin and his generation, as it turns out, would not have to wait long.

Independent Schola r and Florida State University

37. Ibid, p. 238.

-

7/29/2019 ON THE THIRD FRONT: THE SOVIET MUSEUM AND ITS PUBLIC DURING THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION

17/18

Fig. 1: Exposition of Spanish paintings,. Slogan placed over the paintings

says: "Spain 17th century. Art at service of the crowned degenerates and the

church." Courtesy of the authors.

-

7/29/2019 ON THE THIRD FRONT: THE SOVIET MUSEUM AND ITS PUBLIC DURING THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION

18/18

Fig. 2: Exposition of the Flemish paintings. Slogan placed over the paintings

says: "Flanders o f the end of the 16th - the 17"' centuries. Art o f agrarian aris-

tocracy and merchant bourgeoisie." On the left: "Everyday life of working

peasants in imagination o f the ruling class." On the right: "Luxurious life and

hedonistic attitudes of the social upper strata." Courtesy o f the authors.