Notes on the Constructed Image

Transcript of Notes on the Constructed Image

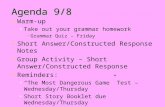

THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE The Constructed Image can come in many forms. Author/critic A.D. Coleman, in his seminal essay The Directorial Mode, defines the practice widely, including any type of photograph where the subject matter has been arranged before the lens, and defends the practice’s history while deconstructing the “presumption of moral righteousness” that is generally attached to purist photography. Certainly, we understand today that all photography is subjective, and it is through the constructed image that we as photographers can trans-form places into theatrical spaces, activate artifacts and archetypes into critical symbols, and challenge the long-cherished assumptions about the transparency of the photograph. These methods push photography beyond the descriptive, therefore positively challenging existing power structures and enacting profound political and cultural critique that extends well beyond the front page of the newspaper or the flash of the television screen.1

For our purposes in this class, we can categorize the Constructed Image into the following types: the CIN-EMATIC, the ART HISTORICAL, the SCULPTURAL OBJECT, and the MYTHICAL/MYSTICAL. This document explores examples of the cinematic and art historical modes along with an introduction to early works in tableaux photography.

1 Coleman, A.D. The Directorial Mode: Notes Toward a Definition. 1976

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

Hippolyte Bayard SELF PORTRAIT AS A DROWNED MAN

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

HIPPOLYTE BAYARD

Bayard, a Civil Servant, was one of the earliest of photographers. His invention of photography actually preceded that of Daguerre, for on 24 June 1839 he displayed some thirty of his photographs, and thus at least goes into the record books as being the first person to hold a photographic exhibition. However Fran-cois Arago (a friend of Daguerre and who was seeking to promote his invention) persuaded him to postpone publishing details of his work. When Bayard eventually gave details of the process to the French Academy of Sciences on 24 February 1840, he had lost the opportunity to be regarded as the inventor of photography. As some recompense he was given some money to buy better equipment, but in no way did this atone for the injustice caused him.2

Bayard’s somewhat surreal self-portrait (October 1840), depicting him as a drowned man, is by way of protest against this injustice of having been pipped at the post because he had kept quiet about his invention. It is in fact the first known example of the use of photography for propaganda purposes, and also of a faked picture.3

On the back on the photograph Bayard wrote:

The corpse which you see here is that of M. Bayard, inventor of the process that has just been shown to you. As far as I know this indefatigable experimenter has been occupied for about three years with his discovery. The Government which has been only too generous to Monsieur Daguerre, has said it can do nothing for Monsieur Bayard, and the poor wretch has drowned himself. Oh the vagaries of human life....! ... He has been at the morgue for several days, and no-one has recognized or claimed him. Ladies and gentlemen, you’d better pass along for fear of offending your sense of smell, for as you can observe, the face and hands of the gentleman are beginning to decay.

2 http://www.rleggat.com/photohistory/history/bayard.htm 3 ibid

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

OSCAR REJLANDER

In THE TWO WAYS OF LIFE, Rejlander wanted to show artists of his time how photography can be an aid in painting while also showing the flexibility photography had as a means of producing artworks that went beyond the recording of subject matter and instead employed allegory, story telling and artistic expression. The TWO WAYS OF LIFE is a large photograph, particularly for its time, and measures 31x16 inches. It took 6 weeks to complete and is comprised of images printed from over 30 negatives.

The composite photograph depicts a father and two sons, each about to make their way down two separate paths, one path towards the right, a path that leads to religion, mercy and industry, the other towards the left, a path full of idlers, gamblers and bacchanalians. The triangular composition, coupled with the strong visual symbolism and moral tone, takes its inspiration from Renaissance painting. The center figure, a nude female draped in a cloth, is often interpreted to represent Mary Magdelene, a disciple of Jesus who was once a prostitute. Therefore, the inclusion of Mary Magdelene is read as a source of hope for the wayward son - that though he is headed to destruction, there is a chance for redemption. At the time, this photographic representation of a nude female was considered indecent.

Oscar Rejlander THE TWO WAYS OF LIFE

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

HENRY PEACH ROBINSON

The most famous of Robinson’s works is Fading Away, 1858. Comprised of images made from five sepa-rate negatives, the picture most likely tells the story of a young girl’s death from tuberculosis. However, the cause of death might have come from greater moral implications, or perhaps even a broken heart. The male figure in the center can be read alternately as the girl’s father/husband/lover. Was the relationship between them healthy and loving, therefore represented by a father turned away in grief, or is this much older lover turned away in shame? Perhaps the male figure does not even know of the young girl’s love, or maybe he did and was forced to turn her affections away. It is this final reading that is often understood as Robinson’s primary meaning, for on the back of one of the prints of FADING AWAY, Robinson wrote this poem:

She never told her loveBut let concealment, like a worm I’ the budFeed on her damask cheek.

Henry Peach Robinson FADING AWAY

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

The CINEMATIC

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

CINDY SHERMAN

Throughout her career, Cindy Sherman has subverted the codes of female subjugation (or perpetuated those same codes) by constantly examining female stereotypes, particularly those found in pop culture cinema. While not necessarily self portraits, each character in Sherman’s pictures is “portrayed” by the artist. There-fore, the images are simultaneously and inseperably read as both photographs and performances.

Sherman’s characters in the Untitled Film Stills are never specified, so we are free to construct our own narratives for the women seen within the pictures. Sherman encourages our participation by suggesting, through the deliberate nature of her poses, that she is the object of someone’s gaze. The voyeuristic nature of these images and their filmic associations encourage a psychoanalytical reading of these works as illus-trations of Laura Mulvey’s renowned 1975 essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” which describes the image of women onscreen as the subject of the controlling male gaze and the object of masculine desire. Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills not only imply our own, as well as the camera’s, gazes but at times hint at the presence of another person that is just out of frame.

In “Visual Pleasure...” Mulvey employs a term, Scopophilia, to describe the conditioned cultural point of view described above. Literally interpreted as a “love of watching,” Scopophilia is synonymous with voy-eurism, where the “watcher” gains sexual gratification from observing others in secret. Often the object of voyeurism is undressed or engaged in some kind of sexual activity. The key factor in voyeurism is that the voyeur does not interact personally with the person being observed. Voyeurs are called Peeping Toms after the legendary man who illicitly looked at Lady Godiva during her ride.

Movie-making and movie-viewing have long been analyzed as voyeuristic practices. Traditionally, the mov-ie viewer sits in the dark and observes the activities of people on a screen (figured as a window) who appear to be unaware of being watched. Horror films in particular are strongly voyeuristic, in that they characteristi-cally identify the viewer with the point of view of the monster.

Feminist film theory has emphasized the notion of “the gaze.” According to this theory, the movie-going experience, and even the cinematic “apparatus,” is coded male. In both subject matter and techniques of filming, movies encapsulate the desire of men to look at women.

For more, see Mulvey, Laura. Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Screen 16.3 Autumn 1975 pp. 6-18

Cindy Sherman, UNTITLED FILM STILLS

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

Gregory Crewdson, UNTITLED (OPHELIA)

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

GREGORY CREWDSON

Gregory Crewdson’s photographs present the superficially idyllic world of rural America and its small towns as an enigmatic cinematographic dream full of dark and mysterious moments, whereby in effect the inexpli-cable element appears as the eruption of rampant, uncontrollable nature into a civilizational context that has become fragile and incomprehensible.

Through theatrical lighting and the inclusion of fantastic and fairy tale elements, the artist operates within the framework of staged photography, which, under the influence of Cindy Sherman and Jeff Wall, became established as one of the most important forms of artistic photography. Crewdson alludes to the popular myths of cinema mainly to visually capture his protagonists’ psychological abysses and secret longings. The result: compelling images of a society gazing into the chasm of its damaged collective psyche, as alienated from itself as it is from the porous and fragile real context through which it moves in an apparently som-nambulist state.

Crewdson condenses filmic narrative logic to a point where a single photograph potentially embodies the narrative expanse of a whole feature film. The surrogate for different narrative fragments at work in these “single frame movies” forms a whole which photographically orchestrates the myth machine of cinema in a way that is as seductive as it is elaborate. It also presents the artificiality and contrived aspect of each picto-rial context, yet without suppressing its magic potential.

For more on Crewdson, see:

Audio clip - http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5157819

http://community.ovationtv.com/_Interview-With-Gregory-Crewdson/video/178577/16878.html

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

JEFF WALL

The constructed images of Jeff Wall reach into both the Cinematic and Art Historical. Often referencing classical painting, Wall constructs his subject matter much like a movie set - using constructed backdrops, props and actors. The following are some of his most notable pictures, which are often presented as large scale light boxes. Included also are the art historical references. Like Rejlander and Robinson in the late 1800’s, Wall uses composite images to construct his large scale pictures, and he was one of the first artists to use the digital medium as a means of combining photographs for fine art purposes.

The DesTroyeD room 1978‘My first pictures like The Destroyed Room emerged from a re-encounter with nineteenth-century art’, Wall has said. Here, the work in question is The Death of Sardanapalus (1827) by Eugène Delacroix, which de-picts the Assyrian monarch on his deathbed, commanding the destruction of his possessions and slaughter of his concubines in a last act of defiance against invading armies.

Wall echoes Delacroix’s composition, with its central sweeping diagonal and sumptuous palette of blood reds, while acknowledging its staged atmosphere by re-composing the scene as a roughly fabricated stage-set, absent of any players. ‘Through the door you can see that it’s only a set held up by supports, that this is not a real space, this is no-one’s house,’ he has commented. Though clearly a woman’s bedroom, the cause of the violence is unexplained, leaving the viewer to speculate on the sequence of events.

PicTure for Women 1979Picture for Women was inspired by Edouard Manet’s masterpiece A Bar at the Folies-Bergères (1881–82). In Manet’s painting, a barmaid gazes out of frame, observed by a shadowy male figure. The whole scene appears to be reflected in the mirror behind the bar, creating a complex web of viewpoints. Wall borrows the internal structure of the painting, and motifs such as the light bulbs that give it spatial depth. The figures are similarly reflected in a mirror, and the woman has the absorbed gaze and posture of Manet’s barmaid, while the man is the artist himself. Though issues of the male gaze, particularly the power relationship between male artist and female model, and the viewer’s role as onlooker, are implicit in Manet’s painting, Wall up-dates the theme by positioning the camera at the centre of the work, so that it captures the act of making the image (the scene reflected in the mirror) and, at the same time, looks straight out at us.

mimic 1982The large color print format that Wall favours requires a camera that is ill-suited to capturing fleeting mo-ments, yet he wanted to explore the documentary style of street photography practiced by a number of photographers, such as Robert Frank or Garry Winogrand. Wall’s solution was to restage such moments, preserving a sense of immediacy by using non-professional actors in real settings. He calls these constructed images ‘cinematographic photographs’. In Mimic, the white man’s ‘slant-eyes’ gesture recreates a scene of racial abuse that Wall witnessed on a Vancouver street.

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

Jeff Wall, THE DESTROYED ROOM

Eugene Delacroix, THE DEATH OF SARDANAPALUS

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

Jeff Wall, PICTURE FOR WOMEN

Manet, A BAR AT THE FOLIES BERGERES

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

Jeff Wall, MIMIC

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

Jeff Wall, ODRADEK

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

Some say the word Odradek is of Slavic origin, and try to account for it on that basis. Others again believe it to be of German origin, only influenced by Slavic. The uncertainty of both interpretations allows one to assume with justice that neither is accurate, especially as neither of them provides an intelligent meaning of the word.

No one, of course, would occupy himself with such studies if there were not a creature called Odradek. At first glance it looks like a flat star-shaped spool for thread, and indeed it does seem to have thread wound upon it; to be sure, they are only old, broken-off bits of thread, knotted and tangled together, of the most varied sorts and colors. But it is not only a spool, for a small wooden crossbar sticks out of the middle of the star, and another small rod is joined to that at a right angle. By means of this latter rod on one side and one of the points of the star on the other, the whole thing can stand upright as if on two legs.

One is tempted to believe that the creature once had some sort of intelligible shape and is now only a bro-ken-down remnant. Yet this does not seem to be the case; at least there is no sign of it; nowhere is there an unfinished or unbroken surface to suggest anything of the kind; the whole thing looks senseless enough, but in its own way perfectly finished. In any case, closer scrutiny is impossible, since Odradek is extraordinarily nimble and can never be laid hold of.

He lurks by turns in the garret, the stairway, the lobbies, the entrance hall. Often for months on end he is not to be seen; then he has presumably moved into other houses; but he always comes faithfully back to our house again. Many a time when you go out of the door and he happens just to be leaning directly beneath you against the banisters you feel inclined to speak to him. Of course, you put no difficult questions to him, you treat him–he is so diminutive that you cannot help it–rather like a child. “Well, what’s your name?” you ask him. “Odradek,” he says. “And where do you live?” “No fixed abode,” he says and laughs; but it is only the kind of laughter that has no lungs behind it. It sounds rather like the rustling of fallen leaves. And that is usually the end of the conversation. Even these answers are not always forthcoming; often he stays mute for a long time, as wooden as his appearance.

I ask myself, to no purpose, what is likely to happen to him? Can he possibly die? Anything that dies has had some kind of aim in life, some kind of activity, which has worn out; but that does not apply to Odradek. Am I to suppose, then, that he will always be rolling down the stairs, with ends of thread trailing after him, right before the feet of my children, and my children’s children? He does no harm to anyone that one can see; but the idea that he is likely to survive me I find almost painful.

– Franz Kafka, Die Sorge des Hausvaters (The Worries of a Householder)

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

Jeff Wall, A SUDDEN GUST OF WIND, AFTER HOKUSAI

HOKUSAI

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

Dead Troops Talk, 1992, is a kind of “dialogue of the dead.” Each figure or group in the picture seems to respond differently to the experience of death and reanimation.

As carefully constructed as a film or epic painting, the work was shot in a large temporary studio, involving performers and costume, special effects and make-up professionals. The figures were photographed sepa-rately or in small groups and the final image was assembled as a digital montage.

Jeff Wall, DEAD TROOPS TALK

Jeff Wall, details from DEAD TROOPS TALK

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

Ralph Ellison’s 1952 novel Invisible Man centers on a black man who, during a street riot, falls into a for-gotten room in the cellar of a large apartment building in New York and decides to stay there, living hidden away. The novel begins with a description of the protagonist’s subterranean home, emphasizing the ceiling covered with 1,369 illegally connected light bulbs. There is a parallel between the place of light in the novel and Wall’s own photographic practice. Ellison’s character declares: ‘Without light I am not only invisible, but formless as well.’ Wall’s use of a light source behind his pictures is a way of bringing his own ‘invisible’ subjects to the fore, so giving form to the overlooked in society.

Jeff Wall, AFTER THE ‘INVISIBLE MAN’

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

Wall described the ‘event’ of this work as ‘a moment in a cemetery. The viewer might imagine a walk on a rainy day. He or she stops before a flooded hole and gazes into it and for some reason imagines the ocean bottom. We see the instant of that fantasy, and in another instant it will be gone.’ The Flooded Grave was completed over a two-year period, and photographed at two different cemeteries in Vancouver as well as on a set in the artist’s studio. It was constructed as a digital montage from around 75 different images.

For more on Jeff Wall, see: http://www.moma.org/exhibitions/2007/jeffwall/” http://www.moma.org/exhibitions/2007/jeffwall/

http://www.tate.org.uk/modern/exhibitions/jeffwall/rooms/room6.shtm

Jeff Wall, THE FLOODED GRAVE

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

The ART HISTORICAL

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

JOEL PETER WITKIN

Witkin’s photographs often recall religious iconography or art historical works through rather gruesome means. Using cadavers, hermaphrodites, transsexuals, dwarfs and the deformed as subjects, Witkin’s tab-leaux images are generally seen as transgressive, irreverent, and sometimes blasphemous things, yet they hold an undeniable beauty - both in form and process. Witkin, a devout Catholic, views his work as a per-sonal expression of his faith, and claims that his macabre visual style comes from seeing the decapitation of a girl when he was young. He writes:

“It happened on a Sunday when my mother was escorting my twin brother and me down the steps of the tenement where we lived. We were going to church. While walking down the hallway to the entrance of the building, we heard an incredible crash mixed with screaming and cries for help. The accident involved three cars, all with families in them. Somehow, in the confusion, I was no longer holding my mother’s hand. At the place where I stood at the curb, I could see something rolling from one of the over-turned cars. It stopped at the curb where I stood. It was the head of a little girl. I bent down to touch the face, to speak to it -- but before I could touch it someone carried me away.”

Raphael, MADONNAJoel Peter Witkin, MOTHER AND CHILD

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

Joel Peter Witkin, LAS MENINAS Velazquez, LAS MENINAS

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

Joel Peter Witkin, VENUSBotticelli, THE BIRTH OF VENUS

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

Joel Peter Witkin, THREE KINDS OF WOMEN Georges Seurat, THE MODELS

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, SUMMERJoel Peter Witkin, HARVEST

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

LUIS GONZALEZ PALMA

Luis Gonzalez Palma has long been recognized for his haunting photographs of solitary figures whose dis-passionate gazes speak of silence and sadness. Intended as personal expressions of the people of his Guate-malan homeland who have been the victims of conquest and violence for generations, each person, whether indigenous Maya or Mestizo, represents the psychological conflicts and personal tragedies of all mankind. He uses numerous symbolic references from Catholicism, Maya myth and ritual, and the culture of Gua-temala to create a poignant environment for his subjects. The large-scale photographs, with their saturated hand-painted sepia tones and layers of appropriated materials and images, are as poignant as they are visual-ly provocative. Adopting a Postmodern approach to exploration of the medium of photography by construct-ing, rather than only discovering, his world, Gonzalez Palma poses questions about the human condition and the way in which visual images can both express and manipulate behavior. His self-conscious awareness of his own people, historically and now in a postmodern world, has led to a technique that gives new mean-ing to his images. Technically and conceptually complex, each work is composed of collaged objects in an asphaltum emulsion that include Kodalithic transparencies, gold leaf, and other materials arranged on red paper and then embedded in resin. He will also frequently use alcohol to remove elements on the surface to reveal certain details, especially the eyes, for a mesmerizing interaction with the viewer. These effects give a sculptural presence to each image that further enhances their reality, and vulnerability, and our own involve-ment. The photographs are beautiful, yet we find ourselves asking: “Why are they so disturbing?” “What does he reveal about his figures and their settings that makes us uncomfortable?”4

4 Bernice Steinbaum Gallery

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

Luis Gonzalez Palma, CONFESSION

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

Luis Gonzalez Palma, THE ANGEL

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

Luis Gonzalez Palma, LA LUNA

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

Luis Gonzalez Palma, LOTTERY

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

Luis Gonzalez Palma, LOTTERY

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

Luis Gonzalez Palma, CROWN OF ROSES

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

Luis Gonzalez Palma, IMAGES OF LABOR AND PAIN

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

Luis Gonzalez Palma, THE LOYALTY OF GRIEF

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

Luis Gonzalez Palma, HOPE

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

Yasumasa Murimura as Frida Kahlo

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

YASUMASA MORIMURA Everybody loves a dame. And Morimura just loves to be one! In (his) self-portraits Morimura convincingly slips into the roles of legendary silver screen goddesses, from Audrey Hepburn to Ingrid Bergman (and it doesn’t stop there - he’s also been art historical icons such as the Mona Lisa and Renoir’s busty barmaid!). But Morimura is more than just art’s most famous drag queen. Dealing with issues of cultural and sexual appropriation he is constantly exploring ideas of image consumption, identity and desire: Can Brigitte Bardot be as innocently flirtatious with angular Japanese features? Would Marilyn Monroe be as sexy if she was Japanese - and a man? And where does the line lay between Garbo’s neurotic reclusivity and the paranoid expression of the down right freaky? In his photos Morimura lives out his impossible dreams of being ‘other’, playing the role of Asian agent provocateur infiltrating Western collective consciousness: becoming the women most lusted after, making them even more exotic.5

Morimura has conceived of his work through simultaneously appropriating and subverting significant art his-torical masterpieces. Through his deconstruction of the notion of the “masterpiece,” Morimura calls into ques-tion assumptions imparted on such works by Western documentation of art history, as well as commenting on Japan’s absorption of Western culture. However, Morimura’s interpretation and representation is particularly effective because while Morimura renegotiates the definition of masterpiece, he genuinely identifies with and respects the artists themselves. By inserting himself into the work, he recreates, relives and indulges in the artis-tic process. His ability to satirize and simultaneously create an homage is what enables his work to defy catego-rization.

Much like Marcel Duchamp’s LHOOQ and performances as Rrose Selavy, Murimura’s pictures blur the line between the masculine/feminine, between the original and the copy, and between the conceptual idea and the crafted object. Murimura seeks to obliterate the world with his own signs; his works are specifically made for art historians and art critics only, in order to stimulate critical discourses.

5 http://www.saatchi-gallery.co.uk/artists/yasumasa_morimura.htm

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

Marcel Duchamp as Rrose Selavy

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

Yasumasa Murimura as Marcel Duchamp as Rrose Selavy

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

Yasumasa Murimura as Marilyn Monroe

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

Yasumasa Murimura as Marilyn Monroe

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

Yasumasa Murimura as Greta Garbo

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010

Yasumasa Murimura as Audrey Hepburn

RAGLAND - NOTES ON THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE 2010