martin lings review of schimmel calligraphy book

-

Upload

ashfaqamar -

Category

Documents

-

view

233 -

download

0

Transcript of martin lings review of schimmel calligraphy book

-

7/30/2019 martin lings review of schimmel calligraphy book

1/3

Journal of the Royal AsiaticSocietyhttp://journals.cambridge.org/JRA

Additional services forJournal of the RoyalAsiatic Society:

Email alerts: Click here

Subscriptions: Click hereCommercial reprints: Click hereTerms of use : Click here

Calligraphy and Islamic culture. By AnnemarieSchimmel (Hagop Kevorkian Series on NearEastern Art and Civilization) pp. xiv, 264. New

York and London, New York University, 1984. \$52.00.

Martin Lings

Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society / Volume 117 / Issue 02 / April 1985, pp 199 - 200

DOI: 10.1017/S0035869X00138511, Published online: 15 March 2011

Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0035869X00138511

How to cite this article:Martin Lings (1985). Review of Annemarie Schimmel 'Calligraphy and Islamic

culture' Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 117, pp 199-200 doi:10.1017/S0035869X00138511

Request Permissions : Click here

Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/JRA, IP address: 131.252.96.28 on 01 Sep 2013

-

7/30/2019 martin lings review of schimmel calligraphy book

2/3

REVIEWS OF BOOKS 199CALLIGRAPHY AND ISLAMIC CULTURE. By ANNEMARIE SCHIMMEL (Hagop Kevorkian Series onNear Eastern Art and Civilization) pp. xiv, 264. New York and London, New York University,1984. $52.00.

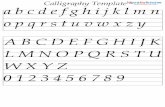

This book with its four chapters perpetuates four Kevorkian Lectures given at New YorkUniversity in 1982. We miss here "the great number of colour slides" which accompanied thelectures, but their absence is partly made up for by plates and also by the many calligraphicinscriptions which are lavishly scattered throughout the text.The first chapter is an informative and well documented study of the main styles of cal-ligraphy. It is followed by "Calligraphers, Dervishes and Kings" which, as its title suggests, ismainly about persons. "Many masters apparently almost every famous calligrapher inOttoman Turkey were in one way or another connected with a Sufi order." One of thegreatest, Shaykh Ham dullah, so entitled because he was the head of an order, taught calligraphyto the Sultan Bayezid II, "who did not mind placing the cushions in the right position or holdinghis inkstand". Nearly two centuries later Mustafa II did the same for Hafiz Osman, who was alsoa Sufi; and when on one occasion the Sultan remarked: "There will never be another HafizOsman" the calligrapher replied: "Your Majesty, as long as there are kings that hold theinkstand for their teacher, there will be many more Hafiz Osmans" a remark not withoutprofundity, and sad for us, because it partly accounts for the extreme artistic poverty of our day.In this chapter, however, the author is perhaps less concerned with kings as patrons than withkings as calligraphers, and she mentions royal adepts of the art not only in Turkey "where almostevery other ruler is known as a calligrapher", but also in Persia and in India, as well as in theArab Near East. Nor must calligraphy be thought of as an exclusively male prerogative, eitherin general or in the royal families. "One of the leading calligraphers in the Middle Ages, whoformed a link between Ibn al-Bawwab and Yaqut, was Zaynab Sh uh da ... and if emperors arecelebrated as good m asters of the craft, princesses did not lag behind."Chapter III, "Calligraphy and Mysticism", opens with the seeming paradox of the importanceof the Book in Islam and the unletteredness of Muham mad. "T he mystics loved to dwell on theilliteracy of the Prophet; and proud as they were of the revealed Book, they also realized thatletters might be a veil between themselves and the immediate experience of the Divine, for whichthe mind and the heart have to be like a blank page." This same idea is taken up again later inthe mention of SanaTs likening of the true mystic to "the alifof bism", for the alif is the firstletter of ism (name) and it experiences fana' (extinction) by disappearing when bi-ism (in thename) is contracted to bism. As to the letters in themselves, that is, when they are not"extinguished", the 10th century Sufi Niffari is quoted as saying that they are "pure otherness"in relation to God, which means that they are symbols of illusion; and the author reminds usthat Yiiniis Emre defined the m ystic's goal as being "to drown in the ocean, to be neither an alifnor a mm nor a ddl." The letters have none the less, as we are shown, a symbolism which

transcends this "drow ning"; in a poem, one of the most sublime in the poetry of the Arabs, whichbegins: "We were lofty letters not yet pronounced", Ibn 'Arab! refers to al-a'yan ath-thabitah,the immutable prototypes of all beings contained in the Divine Essence, prototypes which arealso, as ultimate plenitudes, the supreme aim and end of mysticism. Such considerations as thesehowever, both the transcendent and the negative, remain in the background. The chapter ismainly concerned with the unfolding of the created universe, that is, with the actualized "letters"and with the "pen" which they presuppose. "The Pen, which was able to write everything on theTablet, is according to a Prophetic tradition, thefirst hing that God created. . . Ibn Abi Jumhur,who closely follows Ibn 'Arabrs system, considers the Divine Throne, the Pen, the UniversalIntellect and the primum mobile as one and the same, whereas much earlier the Ikhwan as-Safahad interpreted 'aql (Intellect) as God's 'book written by His Hand'. . . It is therefore notsuprising that calligraphers would regard their own profession as highly sacred, since it reflectsin some way the actions of the primordial Pen ." But in ano ther sense the mystic is mysteriouslyidentical with the Pen, "for the hadith says: 'man's heart is between two of God'sfingers,andHe turns it as He pleases'." The author goes on to give us various Sufi interpretations of thesymbolic meaning of the different letters. There is also mention of the Sufi "Golden Alphabets";and the chapter overflows into a n appendix which consists of a Chishtiyya "mystical alphab et"

-

7/30/2019 martin lings review of schimmel calligraphy book

3/3

2 0 0 R E V I EW S O F B O O K Sof correspondences between the Divine Names, the planes of creation which they govern, theletters, and the lunar mansions.The last chapter is "Calligraphy and Poetry," and in my opinion it is the least successful ofthe four. The imagery offered by script does not always lead to the best poetry, and many of thesimiles and metaphors are far fetched. I, for one, find it difficult to accept the letter nun as aportrayal of the eyebrow of the beloved, who would have to be standing on her head for theimage to be plausible. No t th at no goo d p oetry is quo ted; b ut whenever it is, one feels that therecould and should have been more. This chapter is none the less a relevant complement to thethree others.All four are remarkable for their documentation. The theme which runs throughout issummed up in the sentence: "The art of writing is an essential part of the entire culture of theMuslim world" (and it must be clearly understood that the word "art" means here what it says).If anyone presumed to disagree with the author, he would soon be battered to the ground bythe onslaught of overwhelming proofs which she gives from Arabic, Persian, Turkish, Urdu,Sindhi, Pashto and Malayalam sources; and doubtless many of those who already agreed withher will have to adm it, after reading w hat she quo tes, that the Muslim love of calligraphy goeseven further than they had supposed. "Popular stories also, not only theArabian Nights, showthe high appreciation of calligraphy even amo ng the illiterate: the famous T urkish m aster HafizOsm an had once forgotten h is purse and , returnin g from Istanbul to Uskiidar, paid the ferrymanwith an artistically written waw." Admittedly a calligraphic art exists for every sacred languageand for almost every liturgical language, but there are degrees in the intensity of men's interestin it and it would not be easy to find a parallel to this last anecdote in the West, or anywhereelse outside the world of Islam except in China and Japan.

MARTIN LINGS

MUQ ARN AS: A N A NN UA L ON ISLAMIC A RT AND ARCHITECTUR E, VOL. 2. THE AR T OF THEMAMLUKS. Edited by OLEG GRABAR. pp . x, 18 1, 140 pis., 33 figs. New Hav en etc, Yale UniversityPress, 1984, 35.00The second volume of Muqarnas consists of papers given at the symposium held in conjunc-tion with the notable exhibition of Mamluk Art organised by Esin Atil in 1981 in Washington.These are unrelated to the paper s published in the first issue and on e might have hoped that theywould be published in their own right as an entity leaving Muqarnas to develop a personalityas a critical jou rna l. The re is a despe rate need for a forum of debate in the world of Islamic Artstudies where ideas could be subjected to critical analysis. It is not enough for the results ofresearch to be embalmed in an annual shrine.Book reviews are inadequate, if not dead ends, simply because there is no space in which to

develop criticism. A monthly journal might generate exchanges of ideas which an annual, itselfnaked of scholarly reviews or notes on work in progress, cannot achieve. Some of Dr Lapidus'strictures in this issue might then be met since noth ing tau tens thou ght better than the thrust andparry of debate.This is no t to say th at this issue is barren . Louise M ackie's paper on M am luk silks is cogentlyargued and offers important evidence of the influence of fabric design on other decorative arts:a force which has been seriously underestimated in the past. David James' study of the Koranof Rukn al Din Baybars advances knowledge of Mamluk illuminated manuscripts and theircraftsmanship while Ma m luk ceram ics are the subject of repo rts on work in progress by GeorgeScanlon and Mari lyn Jenkins.David King surveys the astronomy of the period with precisely that lively speculativeapproach which calls for continuing debate as when he suggests that the orientation of mosquesin Tripoli could be based on th at of their relatively d istant m odels. The Cairene architectural andpopulation papers are the result of important research but they are overshadowed by morerecent publications. But Atil 's own paper on late 15th-century Mamluk painting with itsdiscussion of the importance of Turcoman artists cries out for an exchange of views even moreloudly than that of David King.