MakingSerbs - Danilo Mandic

Transcript of MakingSerbs - Danilo Mandic

MAKING SERBS: SERBIAN NATIONALISM AND COLLECTIVE IDENTITY, 1990-2000 By Danilo Mandi

A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Department of Sociology Princeton University 2007

Honor Pledge I pledge my honor I did not violate the Honor Code in writing my senior thesis. Danilo Mandi

2

Acknowledgments Research for this thesis was funded by the George and Obie Shultz Fund, the Fred Fox Class of 1939 Fund, the Class of 1991 Fund, and Princeton Universitys Sociology Department.

3

Note on Transliteration For readers unfamiliar with Serbian spelling and pronunciation, the following guide may be useful for many names appearing below: c dj d j lj nj ts as in cats ch as in church tj as in fortune dg as in drudge j as in job y as in you lli as in million n as in canyon sh as in she zh as in pleasure

4

The enemies of the Serbs made Serbs Serbs. -- Dobrica osi Politika, July 27, 1991.

5

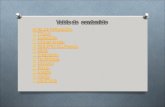

Table of Contents Honor Pledge Acknowledgements Note on Transliteration Table of Contents INTRODUCTION Theoretical Approach and Definition Departing from the Literature on Yugoslavias Disintegration Beyond Blame Scholarship CHAPTER 1: Where Have All the Yugoslavs Gone? (1990-1992) Multiple Identities Values and Voting Military Mobilization and Resistance CHAPTER 2: Enemies and their Portrayal in the Media (1990-1992) The Power of the Media Slovenia Croatia Bosnia-Herzegovina A New World Order CHAPTER 3: United in Misery (1993-1995) Sanctions and the War A New Kind of Society, New Vested Interests Public Opinion and Values CHAPTER 4: Something Borrowed, Something New (1996-2000) Public Opinion in the Second Half of the 1990s The Walks: Novelties The Walks: Continuities and the Nationalist Reaction The NATO Bombing: A Temporary Upsurge in Nationalism The Bulldozer Revolution: Nationalism Defeated The Bulldozer Revolution: Nationalism Lives CONCLUSION Reactive After All Implications for Theory and Future Study Appendix #1 Bibliography 2 3 4 6 7 7 16 23 27 27 36 47 55 55 59 63 70 75 83 84 88 103 114 114 120 128 136 141 146 156 156 162 168 170

6

INTRODUCTION This thesis explores the ways nationalism interacts with external military, diplomatic and economic pressures or perceived nationalist challenges, and attempts to account for the formation and intensification of nationalist collective identity. Specifically, I investigate the ways Serbian collective identity in the 1990s was shaped and, in large parts, defined by the perceived challenges and pressures posed by Croatian, Bosnian Muslim, Albanian and Slovenian nationalisms, as well as by the US and Western European countries that were diplomatically, militarily or otherwise implicated in the Yugoslav civil wars. Through historical and sociological analysis, I intend to establish when and how the notion of we, the Serbs monopolized collective identity and when and how the principle of all Serbs in one state became a popular priority of the highest order. Following the lead of Susan Woodwards history of the dissolution of Yugoslavia, I approach the period as a highly complex civil war in which outside interference was a crucial component and decisive force behind the formation of new nationalist identities, if not the dominant one. Theoretical Approach and Definition A recurring question about Serbian nationalism in the late XX century is: can we better understood it as a state-driven phenomenon, defined and perpetuated by considerations of governments and power elites, or as a phenomenon based on widespread popular senses of community and national identity among Serbs? To illustrate my general take on this question, I briefly outline two theoretical approaches to understanding nationalism: those of Benedict Anderson and Charles Tilly. By highlighting several crucial differences between the two, I hope to simplify a much broader and more sophisticated debate in the theoretical literature

7

over nationalism. Far from mutually exclusive, the two authors overlap on certain analyses of nationalism (especially given their shared Marxian inspiration). I therefore treat the two positions as Weberian ideal types, not strict opposites of an absolute dichotomy. This thesis, I should state immediately, will be friendlier to Tillys general perspective. Andersons influential Imagined Communities purports to salvage Marxism from its discrediting underestimation of nationalism. To account for nationalisms capacity to command such profound emotional legitimacy (even in a world of nominally antinationalist Communist societies), Anderson reevaluates it as a cultural phenomenon. 1 Removing nationalism from the company of isms such as fascism, liberalism and other ideologies, Anderson associates it (along with nationality, nation-ness and the like) with kinship or religion a sense of belonging to an imagined community that is perceived as destiny rather than rational choice and that, like religion, offers transcendental explanations of human sacrifice, agony and death. 2 Much more than simply a false consciousness or outdated irrationality, nationalism is portrayed as a potent source of self-awareness and identity that drives humans to think and behave according to their national membership. As several older sources of identity lost their credibility, nationalism gained the power to motivate and mobilize people (elites and semi-literate peasants alike) to act on its principles often against competing institutions such as the family, the church, the government or the tribe. The imagined community of the nation arose out of large cultural systems (like the religious community and the dynastic realm), most often as a rebellion against them. These systems had held an axiomatic grip on mens minds, Anderson argues, by promoting three

1 2

Anderson, 4. Ibid, 5-6.

8

crucial beliefs: that certain languages and scripts enable unique access to truth, that aristocratic and monarchic rule is divinely ordered and legitimated, and that time flows nonlinearly, cosmologically and without clear separations between past and present. The single greatest force in demolishing these beliefs was print capitalism an abrupt proliferation of the activities of writers, scribes, printers, publishers, lexicographers, grammarians, and text merchants, who not only created a new readership by offering books in the vernacular as well as Latin, but also gave language a novel fixity. Since European nationalism of the late XVIII and early XIX centuries was largely language-based, this enabled populist unification around one or another mother tongue. 3 Print capitalism gave birth to widespread literacy, mass education, linear thinking, accurate maps, novels and a new conception of time. Importantly, Andersons ultimate agent of change is the individual. It is neither state, church, diplomatic elite or intellectual class that sparks nationalist beliefs, but a large group of individuals who autonomously, we are led to presume begin imagining themselves and others as members of a common political collectivity. Each person separately, anonymously and self-consciously consumes the exciting new products of print-capitalism (newspapers, novels, maps, etc.), while others simultaneously do the same, imagining each others existence and awareness. In fact, these by-and-large unaffiliated individuals are so formative of nationalist imagination that more coherent and organized non-individual agents are sometimes even forced to adapt to this imagination. For instance, Anderson argues that the European dynasties of the XIX century were practically left with no choice but to adopt elements of the vernacular as official state language. What is more, these previously nonnationalist elites were ultimately compelled to endorse official nationalism, a fusion of empire and nation. Hence the Romanovs discovered they were Great Russians, Hanoverians3

Anderson, 67-83.

9

that they were English, Hohenzollerns that they were Germans. 4 Official nationalism later flourished, Anderson argues, in the XX century in Asia, Africa and Europe after World War I. This not only implies that individuals can, in sufficient numbers, be the true agents of historical change, but also that powerful institutional structures like the state often have to adapt to nationalisms authority. At first glance, Charles Tillys work does not appear to analyze nationalism, let alone offer an exhaustive theory of nationalism as such. I would argue, nevertheless, that Tillys theses can be understood as an alternative explanation for the very phenomenon Anderson is purporting to explain. Tillys avoidance of the term is indicative of the most crucial difference between them: Tillys focus is the state, not the nation. He finds it unproductive to treat the nation one of the most puzzling and tendentious items in the political lexicon 5 as a proper unit of historical and sociological analysis. It is the modern state that deserves our attention because nationalism and nations depend on an elaborate inter-state system of power relations to even become meaningful. Like Michael Mann and others, Tilly argues that the state precedes and makes possible the rise of nationalism, not vice versa. Its importance, Tilly believes, is its political principle [that] a nation should have its own independent state, and an independent state should have its own nation. 6 The state is so integral to understanding nationalism that even Tillys informal definition of the phenomenon is fundamentally state-based:

4 5

Anderson, 85. Tilly 1995, 6. Cited in Smith 1998, 76. 6 Tilly 2003, 33.

10

The word [nationalism] refers to the mobilization of populations that do not have their own state around a claim to political independence; [] It also, regrettably, refers to the mobilization of the population of an existing state around a strong identification with that state. 7 Thus nations are understandable through the study of European inter-state diplomacy and warfare alone; analyses which fail to acknowledge the states role are, Tilly argues, grossly incomplete. The contrast with Andersons definition of an imagined political community is striking. This not only shifts our attention from the cultural and the imaginative, but affirms the centrality of war, violence, coercion, competing interests and rivalry in defining identities and communities. It is, after all, war that makes states. 8 Far from a romantic vision of the national state as a cultural product of popular will or general sentiment, Tilly is describing a brutally realpolitik institution with behavior and logic comparable to those of an organized crime network. The states activities war making, state making, protection and extraction are essentially self-justifying and self-perpetuating processes that, over time, produce various institutional and ideological by-products (residue[s], in Tillys words) to sustain themselves and maximize efficiency and the probability of success. To formulate the thesis another way: nationalism can be understood as one of these by-products a mere residue. Given the need to placate the demands of various internal and external populations, nationalism emerged as a convenient tool for state-affiliated elites to remain in power, as well as a dominant mode of political communication for those seeking to challenge them.

7 8

Tilly 1993, 116. Ibid 1985, 170.

11

Moreover, Tilly puts great emphasis on the ways war the states ultimate function and purpose necessarily implicates states into complex networks of various constituencies, power structures, industry-specific elites and other states. War as international relations reflects Tillys dismissal of the idea of the state as geopolitically detached the impact of the European inter-state system of coercion and competition is so fundamental that the very distinction between internal and external, domestic and foreign affairs is blurred.9 As states pursue their own interests, the interests of other states and the overall balance of power restrict and frame the behavior of all actors involved. It is only in this inter-connected and complex arena that nationalist ideologies can emerge, and are fated to be dependent on these state activities and inter-state relations. Three crucial points of contention between the two authors can be summarized. Firstly, they diverge on the nature of the causal relation between political reality and what we might call popular perception. For Anderson, a fundamental shift in a groups perception of time, history, geography and itself produces new political realities based on nationalist ideology; for Tilly, it is the political realities shaped overwhelmingly by states which cause peoples affected by these realities to gain new perspectives, ideas, and so-called worldviews. For both authors, the nation is a construct; yet, it is a different kind of construct for each. Anderson argues it is constructed by the imagination of its members a process precipitated by print-capitalism and the collapse of pre-nationalist dogmas like divine rule and cosmological senses of time. Tilly, on the other hand, argues it is constructed incidentally and derivatively by rivaling states pursuing their self-interests in a violent, competitive arena. Put crudely, Anderson believes popular perception constructs nationalist reality, while Tilly believes the state constructs both those things.9

Tilly 1985, 184.

12

Secondly, there is a difference regarding the extent to which nationalism is a product of top-down processes as opposed to vice versa. Anderson suggests bottom-up processes are crucial for the development of nationalism and might even overpower top-down pressures from, say, imperial elites. He acknowledges the role of high institutions like monarchies and colonial administrations, but does not see them as central. In sharp contrast, Tilly treats grassroots forces as generally deferential to higher structural and institutional processes from the top. Another formulation of this difference is whether nationalism is understood as a somewhat spontaneous or state-dependent phenomenon. As mentioned, Tilly necessarily implicates nationalism into a complex system of interconnected and competing states; in this context, nationalism is inherently reactive and dependent on state-related affairs. For Anderson, nationalism is fairly spontaneous in this regard, potentially oblivious to structures like the state and primarily dependent on the private, autonomous thought processes and sentiments of individuals. At best, Anderson concedes that the state may regulate nationalism, but does not allow for the possibility that nationalism presupposes a political order based on state structures. Finally, while Anderson describes nationalism as a cultural phenomenon arising out of large cultural systems, Tilly subsumes nationalism into the realm of politics as a phenomenon arising out of considerations like protection from violence, coercion, violation of property rights and so on. Andersons national subjects, in contrast, are motivated by emotional considerations, senses of belonging, internal mental processes and reflections on transcendental matters of suffering and death.

13

Table 1.0. Anderson vs. Tilly on Nationalism Dissimilarity Primary (not exclusive) source of loyalty and allegiance to nation state Primary agents of historical change Proper unit of analysis Single most emphasized development that allowed nationalism to arise Context out of which nationalism arose The direction of the formation of nationalism Anderson Emotional and psychological legitimacy, built through the imagination of community. Individuals. The nation. Print-capitalism. Cultural: Religious community, dynastic realm and other large cultural systems. A bottom-up process nationalism as somewhat spontaneous. Tilly Force, violence and coercion. States. The state. War. Political: European inter-state warfare, competition, rivalry, conflict, etc. A top-down process nationalism as statedependent.

These differences are, of course, matters of emphasis, not fundamentally irreconcilable perceptions. Nevertheless, this thesis tackles nationalism in a sense closer to Tillys general approach: with an emphasis on the role of states, war, coercion and political conflicts on nationalism as opposed to more Andersonian concerns. Accordingly, I will define Serbian nationalism as that set of political demands and collective actions that called for the uniting of all Serbs into a single independent state ruled by Serbs. These will include not only the doctrine of Greater Serbianism, but also advocacy of those variants of Yugoslavism and socialism that emphasized unity with Croats, Slovenes or Muslims but under the condition (at least implicit) that Serbs enjoy superior status of one kind or another. To take an example from another time period: many advocates of the post1918 Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes would be treated as Serbian nationalists under this definition if their defense of south Slav unity was motivated not by utopian beliefs

14

in altruistic brotherhood and inter-ethnic teamwork, but by the hope that Serbian interests will be served to a greater extent than those of other groups.10 The Yugoslav civil war inspired social scientists to generate an array of imprecise concepts (historico-ethnic, ethno-mythological, religio-national, ethno-fascist and nihilo-nationalist are among the most impressive), most of which I intentionally avoid. Nationalist collective identity and Serbian-ness are used synonymously to describe the general sentiment that primary loyalty should be directed to being Serbian, not Yugoslav or Orthodox Christian or a citizen of Vojvodina or a resident of Belgrade. Bosniaks will refer to Bosnian Muslims; Bosnians, to citizens of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Preceding the word Serbs or Croats with the epithet ethnic is a prevalent custom in much of the literature, though it has worn out its usefulness. It had originally served to distinguish between nationality and civic status (an ethnic Serb from Croatia as opposed to a Croat from Croatia), but has degenerated into an attempt to homogenize national belonging and to account for the discrepancy between state and national boundaries. To avoid wordiness, I avoid the prefix ethnic and refer to the entire nationality as Serbs. Citizens of Serbia will be Serbians as opposed to Serbs, citizens of Croatia Croatians as opposed to Croats, and so on. I avoid the careless distinguishing between ultra-nationalists and nationalists, preferring simply the latter. Finally, to dodge an extraordinarily difficult debate over what new categories of identity the Yugoslav civil wars have introduced in the fields of anthropology and sociology, I use ethnicity and nationality interchangeably.

For the most influential author arguing that the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was intended as an expression of Serbian hegemony, see: Banac 1984.

10

15

Departing from the Literature on Yugoslavias Disintegration The focus on Serbian nationalism specifically is not meant as a rejection of comparative approaches to understanding the Balkans or as a statement about the uniqueness of Serbias nationalist experience. To the contrary, I emphasize the inherently interactive and interconnected nature of Serbian nationalism to Croatian, Slovenian, Bosnian Muslim and even Western nationalisms. Although authors like Ivo Banac, Charles and Barbara Jelavich and Stevan K. Pavlowitch have carried out extensive comparative studies of Yugoslavias various nationalisms in the pre-World War I or pre-World War II era, 11 few have emphasized that Serbian nationalism in the last decade of the XX century can only be understood if contextualized in relation to its rivals. Instead, much of the literature on the 1990s breakup has perpetuated the notion of the uniqueness of Serbian nationalism the idea that Serbian nationalism is, in one way or another, an anomaly and exception in its unusual aggressiveness, irrationality, intolerance, aversion to multiculturalism, propensity for violence, expansionist tendency or general backwardness. Branimir Anzulovis Heavenly Serbia: From Myth to Genocide isolates the development of Serbian nationalist ideology from those of other South Slavic peoples to attribute a genocidal nature to it.12 Less extreme but somewhat similar approaches are visible in Michael Sells A Bridge Betrayed: Religion and Genocide in Bosnia-Herzegovina, in Stephen Schwartzs (and Christopher Hitchens') Kosovo: Background to a War, and even in the standard works of distinguished

Banac, 1984; Pavlowitch 1999; Jelavich and Jelavich 1987. In addition, comparative approaches have sought to evaluate the similarities between Serbian nationalist state policies and Israeli state violence (Ron 2003), between ethnic cleansing experiences in Yugoslavia and Rwanda (Mueller 2000) and even between the Armenian genocide, state-sponsored massacre in Niger and Serbian crimes in the Bosnian war (Melson 1996). In addition to some unwarranted generalizations and occasional overlooking of the specificities of Serbian nationalism, these approaches do not address the interrelations and interconnections of Balkan nationalisms or the ways their mutual relationships define them. To employ a metaphor from Michael Reynolds: it is one thing to study bacteria as a series of isolated case studies in separate petri dishes, and quite another to examine the ways they reproduce and interact with each other in the same environment (Reynolds 2003, 10). 12 Anzulovi 1999.

11

16

journalist Tim Judah. 13 In large parts, it was this uniqueness thesis that gave rise to the dubious distinction between "ethnic nationalism" and "civic nationalism," the former being a destructive, anti-liberal, virulent plague infecting the world and the latter being a democratic, multi-cultural, diversity-friendly model exemplified by peace-loving democratic nation-states. 14 The distinction is largely normative and analytically unhelpful, though its political usefulness is clear. However as Diana Johnstone, Kate Hudson and Aleksa Djilas have warned branding the dark side of Serbian nationalism unique is not only historically unsound but might blind us to the uncomfortable commonalities it may have with its Western counterparts. I maintain that crucial features of Serbian nationalism are far from unique and that the formation of collective identity described and traced here is easily detectible in most, if not all other national groups. With a few exceptions, the approach to historical analysis of the 1990s Balkan wars is regularly a traditional, top-down approach that analyzes statesmen and formal institutional interactions a "history of leaders," if you will, in which the principal agents and carriers of nationalism are presidents, military officials and high-level diplomats. A typical example is the obsessive focus on Slobodan Miloevis 1989 speech at Kosovo Polje, at which fateful moment we are led to believe he gave birth to Serbian nationalism. This kind of approach not only tends to neglect the existence of opposition movements in the various Yugoslav republics, but treats public sentiment and grassroots nationalism as products of well-designed schemes of the republics' leaders, who are considered the true actors in the drama. Although it is certainly true that leaders of authoritarian currents (primarily in Serbia and Croatia) enjoyed overwhelming control over major events in the wars, they were also under

13 14

Schwarz 2001; Sells 1998; Judah 2000. For a clear example of the distinction, see: Roshwald 2001, 3-4, though the distinction is pervasive.

17

significant pressure from their republics' populations. Occasionally, this public pressure restricted policymaking, even though state elites rarely admitted so in public. For instance, the massive anti-Miloevi protests in Belgrade in March of 1991 put noteworthy pressure on the regime and significantly complicated the supposedly homogenous nationalist mindset of Serbia. Similarly, the 1992 Sarajevo protests against ethnic division caught many nationalist leaders by surprise, as it turned out that popular antiwar sentiment opposed to exclusionary nationalism in Bosnia-Herzegovina made mobilization for war difficult. Yet, Little and Silbers canonized book on the war Yugoslavia: Death of a Nation assumes that war mobilizes public opinion to the power centers of each republic, leaving the leaders with most, if not all the influence. 15 In a similar vain, Louis Sell tells the story of the destruction of Yugoslavia with no more than a biography of Miloevi alone, as if the single leaders decisions and political maneuvers account for all the developments of the period. 16 Doder and Branson likewise attribute all the major developments of the period to biographical explanations related to Miloevi, with practically no acknowledgement of public opinion in its own right. 17 I argue, however, that the connections between public support for state authority, nationalism among elites, nationalism among the general population, and actual political events and outcomes during the period, were rarely straightforward. The views of Slobodan Miloevi, Ratko Mladi, Vojislav eelj and other nationalist icons were often irrelevant to the levels of nationalism among Serbs at large. Mobilized masses, occasionally at least, had nationalist demands quite disparate from their leaders, and were sometimes even infringements on leaders' power. Inspired in part by Padraic Kenneys study of the Central15 16

Silber & Little 1996. Sell 2002. 17 Doder and Branson 1999.

18

European revolutions that toppled Communism in 1989, 18 I explore the often neglected, grassroots influences on collective identity and state policy which arise from below and are sometimes impervious to official state policy or the pressure of leaders. Although political sociology has tackled the interaction between nationalism and military crisis in the Balkans, few studies have dealt with the role of external pressure vis-vis the destructive rise of Serbian nationalism. Indeed, Misha Glennys Fall of Yugoslavia belongs to a marginal minority by emphasizing factors other than Serbian aggression as roots of the problem, and was ground-breaking at the time of its publication in questioning Western intentions in the Balkans. 19 By-and-large, however, non-Yugoslav influences on the civil war have not received reasonable attention. At one extreme, there is a conspiratorial, nationalistic and oddly paranoid account, which sees the machinations of the international community (usually defined as the Vatican, US, Britain and Germany) as the primary source of the excesses of Serbian nationalism, as it manifested itself in ethnic cleansing, territorial expansion and ethnic fanaticism. 20 At another extreme, there is a highly idealized vision of the international communitys benevolent and altruistic efforts in mitigating the irrational and barbaric practices of Balkan primordial nationalists. 21 In between are standard interpretations of the Yugoslav wars, which explain major events as caused primarily by Serbian aggression and secondarily by the various reactions to it within Yugoslavia, with the disinterested or humanitarian international community failing to intervene on time, or with insufficient force to impose stability. 22 One reflection of the last two of these approaches is the common reluctance among scholars to refer to the conflict as a "civil war a term thatKenney 2003. Glenny 1993. Other useful analyses of external factors in the dissolution of Yugoslavia are Hudson 2003; Parenti 2001; Chomsky 1999. 20 eelj N.d.; Batakovi N.d.; Mitrovich 1999; Hudson 2003; Parenti 2001. 21 Doder and Branson 1999; International Crisis Group 2001; Malcolm 1998. 22 Ignatieff 2000; Judah 2000; Mertus 1999; Vickers 1998.19 18

19

appears to contradict an original sin thesis of Serbian nationalism as the primary instigator of the bloodshed, or that appears to assume that multi-ethnic Yugoslavia was a legitimate entity. Most of these accounts remain incomplete because they assume that Serbian nationalism arose somewhat spontaneously and in isolation, not as a reactive or interactive force shaped by other nationalisms of the Yugoslav crisis. I approach the conflict precisely as a civil war to draw attention to the interactive aspects of Serbian nationalism and away from its supposed exceptionality and isolation. While I avoid reductionist attempts at burdening only outside forces for the Yugoslav tragedy, 23 I do concentrate significantly on external factors and pressures in making Serbian collective identity what it was. Serbian nationalism (imagined as arising spontaneously and in isolation) is often said to explode when, for instance, an intellectual class or political leader comes along and ignites a mass nationalist awakening in some sort of political vacuum. Nationalists themselves especially promote the view, as they are mostly hesitant to describe their own nations as responses to other nations or outsiders (which might imply a status of inferiority), preferring instead to portray those other nations (or ideologies like Bolshevism, religions like Islam, etc.) as reacting derivatively to us and our natural instinctive desires (which implies our superiority). Such is the unswerving line of Matija Bekovi, Vojislav eelj and other Serbian hardliners (some of whom see themselves as the sparks that ignite nationalist awakening), though similar approaches are visible in the works of Anzulovi and others. Aside from the aforementioned Miloevi speech at Kosovo Polje, many Western accounts point to the 1986 Memorandum of the Serbian Academy or the publication of books by Dobrica osi or Vuk Drakovi as the beginnings of the stirring of Serbian nationalism in the late 20th Century. As Ivo Banac has pointed out, this approach mistakenly assumes that23

Examples of such reductionism are Parenti 2001, Hudson 2003, and a plethora of Serbian nationalist authors.

20

Titoist Communist Yugoslavia was a period of absolute peace and tolerance, devoid of national conflicts until the unfortunate rise to power of Slobodan Miloevi. Departing from these approaches, I treat nationalisms in the Balkans as primarily reactive and interactive forces shaped by other nationalisms, perceived outside threats, external economic challengers, rival ethnicities, etc. As Aleksa Djilas has pointed out, Serbian nationalist fears and ambitions were by no means post-Communist novelties concocted by a clique of intellectuals or political elites. 24 In fact, the presence of Serbian nationalism in the 1990s is often independent of nationalist leaders, intellectuals or elites, which suggests caution about what is sometimes called a constructivist approach to the phenomenon. 25 Nevertheless, an approach that emphasizes almost everlasting, primordial, ancient hatreds which were merely delayed by the post-1945 Communist regime and erupted inevitably in the 1990s is equally unsatisfying. For all their transcendental differences, Serbian and Croatian nationalists in fact agree that the only way to understand nationalist rivalries in the 1990s is to trace them back to XIX century (if not earlier) national yearnings and to understand the other sides malicious thirst to replay previous historical crimes. The most obvious battleground for such nationalist interpretations is the Second World War. Vladimir Dedijers Yugoslav Auschwitz and the Vatican 26 and similar books reviewed Croatian extermination policies against Serbs in World War II in painful detail and encouraged viewing the Croatian separatist movement in the 1990s as continuities of the ustaa regime of the 1940s. In contrast, Croatian nationalists such as Franjo Tudjman24 Djilas 2005. This very question how ancient or modern the nationalist rivalries and hatreds in question are has been hotly debated by Djilas in his much-publicized review of Noel Malcolms Kosovo: a Short History (1998). The latter was criticized for downplaying the role of ancient hatreds in the conflicts between Serbs and Muslims in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo, as Djilas argued that the impact of the divisions of the Second World War are quite deep and that BosniaHerzegovina in particular should not be idealized as a multi-ethnic paradise without national tensions. See Djilas 2005, 163175. 25 For an extensive presentation of the constructivist approach (albeit in the African context), see: Yeros, 1998. 26 Dedijer 1992.

21

himself in his Horrors of War and Genocide and Yugoslavia exonerate the WWII Croatian state from responsibility for genocide and see in the ustaa experience a legitimate national aspiration of the Croatian people. 27 Both approaches overestimate the ancientness and underestimate the novelty of major aspects of the national divisions of the 1990s. Significant national differences existed in the Balkans, to be sure, but were historically more often determined by regional as opposed to national lines. Differences between two regions populated by the same national group were often greater than those between two different national groups populating the same area (this is, incidentally, true even of most of the early 1990s). 28 Furthermore, precise nationalist delineations from the ancient past are extremely difficult to acquire, given the closeness of the three principal languages of the region, the frequent conversions among religions, the promiscuity of cultural practices in the region, and the high levels of inter-ethnic and inter-religious marriages (especially in BosniaHerzegovina). Therefore, the opposite extreme of reducing the rise of nationalism in the 1990s to obvious ancient trajectories that were perfectly predictable and perhaps inevitable is very problematic. In conclusion, it remains extremely difficult to predict or explain behavior according to ethnicity, religion, and ideology in the Balkans. Accordingly, I will aim for a balancing act in regard to the difficulty of representing Yugoslavia's disintegration along nationalist lines. Some of the identity categories ethnic and religious especially are inevitably somewhat confusing, given how conflated they are. Most scholars have never fully reconciled the difficulty of treating Serbian-ness as parallel to Muslim-ness in Bosnia-Herzegovina, for instance. Or, when we look at the Yugoslav Armys conduct during the wars, its state

27 28

Tudjman 1996a, 1996b. Djilas, 4-6.

22

socialist ideological character may not explain much of its decision-making. Therefore, when discussing interactions and reactions of Serbian nationalism with its rivals, it is not a matter of dealing with simple identity equations (Miloevi-style Communism and Orthodox Christianity, Catholicism and "Greater Croatian" nationalism, Islam and Bosnian secessionism, etc.). Rather, nationalism, ethnicity, etc. will be seen as driving forces of violence only in so far as Serbs, Croats, and Muslims are taken as highly imperfect categories. Finally, certain aspects of the conflict are, as many scholars agree, reducible to purely realpolitik standpoints, unrelated to ethnic considerations or national loyalties. I will therefore remain cautious about misinterpreting elements of a straightforward war for territory through the lens of abstract national imagination, but will also remain sensitive to crucial nationalist differences. Beyond Blame Scholarship Sadly, most of the literature on Yugoslavias demise ranges from biased analyses to outright nationalist propaganda. By-and-large, Serbian nationalism is analyzed with deliberate implications for who is to blame for its detrimental impact and who is to be vindicated of responsibility for the grotesque levels of carnage. In Yugoslavia itself, scholars like Anzulovi and Mitrovich seek to blame Serbian and Croatian nationalism, respectively, for instigating and escalating the bloodshed and rejecting peaceful solutions and diplomatic initiatives from the other side. 29 Much of our information about the Serbian-Croatian war comes from the likes of Former Yugoslav Defense Minister Veljko Kadijevi, whose purpose is not necessarily to narrate truthfully, but simply to justify the behavior of the Yugoslav

29

Anzulovi 1999; Mitrovich 1999.

23

Army. 30 Outside Yugoslavia, Western scholars seek to condemn or defend the actions of the international community according to ideological considerations or local political loyalties. Michael Ignatieff, Ivo Daalder and Michael O'Hanlon, for instance, criticize US/British interventions in the former Yugoslavia on the grounds of one or another party faction on the Anglo-American political scene. 31 Similarly, Robert Kaplans Balkan Ghosts was explicitly written with the hopes of influencing if not guiding Clinton administration policies. 32 Generally, the purpose of many travelogues or eyewitness accounts of the rise of Serbian nationalism was far from descriptive and empirical. The normative nature of most of the accounts is due to the fact that they come from journalists or involved state officials, not sociologists or political scientists. Often, journalists perspectives are mere reflections of where they were reporting from during the civil war. Authors such as David Rohde, Roy Gutman, David Rieff and others reported mostly from areas under siege by Serbian forces and, understandably, offer books that lament Western non-intervention. Peter Brocks reporting from Serbian areas, conversely, accuses Western media coverage of the war in Bosnia-Herzegovina of bias against Serbia. 33 Similarly, statesmen and military officials like Richard Holbrooke and Wesley Clark are precious sources of information, but write primarily to support their own involvements rather than to offer objective, descriptive accounts of historical events. 34 What is more, many works that have entered the canon are authored by journalists affiliated with politicized organizations or statesmen with obvious agendas. Miloevi-biographer Louis Sell was a US

30 31

Kadijevi 1993. Ignatieff 2000; Daalder and OHanlon 2001. 32 Kaplan 2005. 33 Brock 2005. 34 Holbrooke 1998; Clark 2001.

24

Foreign Service officer and a board member of the International Crisis Group, which predictably restricted his distribution of guilt for the Yugoslav wars. The shortcomings of such blame scholarship have been amply documented. Edward Herman and Philip Hammonds collection of essays demonstrates the limitations and ideological pollution of media coverage of the Kosovo crisis of 1999 as well as the earlier phases of the wars in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Croatia. 35 Aleksa Djilas has pointed out some of the limitations of Noel Malcolms exclusive focus on non-Serbian documentary sources and archives in his Bosnia: A Short History and Kosovo: A Short History, with broader implications for how to avoid partiality in similar historical accounts. 36 In addition, both Ed Vulliamys Seasons in Hell: Understanding Bosnias War, and Gutmans Witness to Genocide have been discredited for their exaggerated and even fabricated accounts of mass rape and death camps in Bosnia-Herzegovina, even though both went on to become bestsellers and award-winning works. 37 In sum, healthy skepticism and heavy scrutinizing of most secondary sources especially given the normative stakes in evaluations of external pressures on Serbian nationalism are in order. To address this problem of bias, I can do little more than acknowledge an obvious point: I will strive to separate, to the extent possible and to the satisfaction of common sense, my political judgments from my analysis. This thesis, as any work dealing with such a brutal historical episode, will present arguments which will unfailingly be shared by Serbian extremist nationalists, just as it will contain claims dear to the hearts of apologists for Western misconduct. It will mostly, however, present evidence in favor of an understanding

Hammond and Herman, 2000. Djilas, 2005. Tim Judah has also challenged some of Malcolms approaches. 37 Hammond and Herman, 2000; Ali 2000. For a credible account of death figures and other statistics about the war, see: Ewa and Bijak 2005 (a study by demographers commissioned by the Hague tribunal).36

35

25

of nationalism that can help future handlings of it be more productive and humane. I cannot perfectly avoid being labeled biased in one direction or another, especially on political issues as contentious as the ones surrounding the Yugoslav conflicts. Unfortunately, uncompromising advocates of one nationalism/ideology or another will inevitably denounce analytic approaches, often regardless of what analysis may conclude. Against such thinking, I hope my views and interpretations which I have strived to make as transparent as possible will be judged on their merits.

26

CHAPTER 1: Where Have All the Yugoslavs Gone? (1990-1992) This chapter deals with the period that is often referred to as a climax of Serbian nationalism by exploring what some of its concrete features were. Contrary to many of the authors mentioned above, I argue that Serbian nationalism should not be overemphasized as a causal factor in this stage of the disintegration of Yugoslavia. I first outline the movement from a widespread self-understanding based on multiple identities (which assigned low importance to nationality) to a more nationalist one, based on ethnicity and a rejection of the more collectivist category of Yugoslavs. Secondly, despite a lack of satisfactory public opinion data, I investigate the extent to which values conducive to nationalism were reflected in public opinion and how these were translated into voting decisions in the fateful elections of this period. Finally, I review the military mobilization of 1991, the massive resistance to it, and the implications of both for understanding the limits of Serbian nationalism. Multiple Identities From 1960-1980, Yugoslavia had one of the worlds leading economic growth rates, one of Europes lowest infant mortality rates, a steady inflow of enormous foreign capital, an extensive system of free health care, a guaranteed right to an income, affordable transportation and housing, one of the highest levels of university-educated women in the world, and a life expectancy of seventy-two years. Without an official national to its state, Yugoslavia was a rarity in Europe and one of very few on the continent without an official national language. Though often ridiculed for their inefficiency and corruption, independent worker councils and student-run cafeterias maintained a level of grassroots

27

participation and self-management in local affairs that was unheard of in the rest of the state socialist world. The red Yugoslav passport could cross virtually every border in the world, and its bearer could afford the indulgence thanks to a guaranteed, subsidized one-month vacation. The so-called Third World placed its hopes on Yugoslavias economic development model, victims of Soviet terror in Eastern Europe cheered the countrys clash with Stalinism, while President Gerald Ford eagerly toasted to Yugoslavias honor by observing that Americans have particularly admired Yugoslavia's independent spirit. 38 In this cozy socialist environment of brotherhood and unity, it made little sense to emphasize ethnic and religious differences for any political posturing, let alone for territorial expansion. Students and workers of numerous backgrounds shared university classrooms and factory floors, often in blissful ignorance of what nationality some of their colleagues even were. Although sometimes dismissed as revisionist romanticization of an artificial, repressive communist state that was united only by coercion (the dreaded Yugonostalgia), the fact remains that even the very last years preceding Yugoslavias death were a period of considerable multi-nationality. To be sure, much of Yugoslav anti-nationalism was a coerced principle, dictated by state socialist ideology for often unflattering reasons. Yet Titoist dogma notwithstanding, the simple power of decades of multi-ethnic life and mixing throughout the entire state in discouraging nationalism was undeniable. Despite the claims made by nationalist leaders, Susan Woodward wrote, the reality of multinational Yugoslavia still existed in the lives of individual citizens in 1990-91 in their ethnically mixed neighbourhoods, villages, towns and cities; in their mixed marriages, family ties across republic boundaries, and second homes in another republic; in their conceptions of

Gerald Ford, Toast at State Dinner in Belgrade, August 3rd, 1975. Available at stable URL: http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=5146 (the American Presidency Project).

38

28

ethnic and national coexistence and the compatibility of multiple identities for each citizen. 39 Indeed, multiple identities were reflected in multiple loyalties and associations, most of which were localized and non-national (families, schools, sport teams, neighborhoods, villages, professional associations, etc.). A national character was particularly deficient among younger generations, especially those far enough from the inter-ethnic carnage of World War II to be uninterested. In a study of youth attitudes towards identity in Serbia proper (a highly homogenous environment, as we will see below), a predominance of personalistic beliefs was found those based on the idea that people should be judged as persons rather than as members of nations. A majority of respondents rejected national background as something of importance: 61% regarded it as less important that ones profession, friends, age, family, class position, gender, political orientation and region. In ninth place, nationality found itself above only the categories of favorite sport and religion on the scale of significance. 40 Though more moderate, a similar rejection of national identity as a priority was also recorded among the population at large, who likewise preferred localized, smaller categories. 41 It was from this cocktail of identity that a vulgarized, jingoistic and narcissistic national identity emerged among Serbs, drawing loyalty and allegiance to Serbia above all other collectivities and claimed the most brutal atrocities in Europe since the Second World War in its name. To trace this rise, I begin with a look at data relating to the curious concept of Yugoslav-ness. A powerful indicator of multiple identities and the absence of nationalism is the number of citizens in post-World War II census data declaring themselves

39 40

Ali 2000, 205. Panti 1994, 149. 41 Ibid 1991.

29

Yugoslav an ethnically, culturally and religiously undefined category, which was competing against six constitutionally-defined national or religious categories, six national minorities and over ten other recognized ethnic groups. As a rough indicator of what political collectivity citizens directed their allegiance to, this census data is potentially a valuable way to trace Serbian nationalism and its rivals. [See Appendix #1 for a visual representation of this data.]Table 1.1. Self-declared Yugoslavs in Republics and Regions: Numbers 42 Republic or Region Bosnia-Herzegovina Montenegro Croatia Macedonia Slovenia Serbia (total) Central Serbia Vojvodina Kosovo & Metohija SFR of Yugoslavia 1961 275,883 1,559 15,559 1,260 2,784 20,079 11,699 3,174 5,206 317,124 1971 43,796 10,943 84,118 3,652 6,744 123,824 75,976 46,928 920 273,077 1981 326,316 31,243 379,057 14,225 26,263 441,941 272,050 167,215 2,676 1,219,045 1991 239,845 25,854 104,728 n/a 12,237 317,739 145,810 168,859 3,070 n/a [1,018,142 w/o Macedonians]

Table 1.2. Self-declared Yugoslavs in Republic and Regions: Percentages Republic or Region Bosnia-Herzegovina Montenegro Croatia Macedonia Slovenia Serbia (total) Central Serbia Vojvodina Kosovo & Metohija SFR of Yugoslavia Republic Bosnia-Herzegovina Percentage Share of Yugoslavs in Total Population 1961 8.4 3.3 0.4 0.1 0.1 0.3 0.2 0.2 0.5 1.7 1971 1.2 2.0 1.9 0.2 0.4 1.5 1.4 2.4 0.1 1.3 1981 7.9 5.3 8.2 0.7 1.4 4.7 4.8 8.2 0.2 5.4 1991 5.5 4.2 2.2 n/a 0.6 3.2 2.5 8.4 0.2 n/a

Percentage distribution of Yugoslavs 1961 87.0 1971 16.0 1981 26.8 1991 23.56

42 Both tables are drawn from 1961, 1971, 1981 and 1991 censuses. The rapid decline in the number of persons declaring themselves Yugoslavs from the 1961 to 1971 is due to the fact that Muslim was offered as a novel category in the 1971 census for the first time. This explains why Bosnia-Herzegovina, with its sizable Muslim population, saw the most abrupt drop in Yugoslavs in this period. Additional summaries of the census data in the discussion below are drawn from Spasovski et al. 1995.

30

Montenegro Croatia Macedonia Slovenia Serbia SFR of Yugoslavia

0.5 4.9 0.4 0.9 6.3 100.0

4.0 30.8 1.3 2.5 45.4 100.0

2.6 31.1 1.2 2.1 36.2 100.0

2.54 10.29 n/a 1.20 62.42 ~ 98.5 (100.0 w/o Macedonia)

Firstly, it is interesting that the most rapid increase in Yugoslavs occurred in the Republic of Serbia itself. Over 420,000 citizens of the republic abandoned their previous identity categories (mostly Serb) in just twenty years (1961-1981). Despite a significant drop of the percentage share of Yugoslavs in the total population in Kosovo and the vastly superior natural growth rate of Muslims in all the republics, this percentage share rose in the Republic of Serbia from 0.3% in 1961 to 3.2% in 1991. This is largely due to the astounding increase in Vojvodina, Serbias northern region: the share of Yugoslavs rapidly rose from 0.2% to 8.4% in forty years. In 1961, only 3,174 Yugoslavs in Vojvodina called themselves that; by 1981, the number had climbed to over 167,000, a 53-fold increase. Ignoring for the moment natural growth rates and migration patterns (relatively stable anyway), this means 22 newly-declared Yugoslavs on average were being made every day for twenty years. What is more, Vojvodina saw the continuation of this growth in Yugoslavs into the 1991 census, unlike the Republic of Serbia as a whole, which saw a slight decline from 1981. This suggests that, whatever complex set of forces it was that discouraged nationalist selfidentification and advanced the more collectivist Yugoslavism, it appeared to be significantly more effective in Serbia than in the other republics, if not most effective. Secondly, of all those who declared themselves Yugoslavs in 1971, 45.4% lived in Serbia, 30.8% in Croatia, and 16.0% in Bosnia-Herzegovina. The latter two percentages are, furthermore, in large parts reflecting the Serbian minorities in those republics. In BosniaHerzegovina, for instance, 43,796 Yugoslavs in 1971 grew to 326,316 in 1981 (from 1.2% to

31

7.9% of the total population), but this was correlated to an equally sharp decline of declared Serbs in the republic, suggesting that even Serbs outside Serbia tended to become Yugoslavs disproportionately to other nationalities. By 1991, a remarkable 62.42% of all Yugoslavs were accounted for in Serbia alone (up from 36.2% since 1981, and an almost tenfold increase since 1961). In the total increase of 949,947 persons that declared themselves Yugoslavs in the entire communist state from 1971-1981, it is estimated that 890,730 or 93.8% were individuals who changed categories between the two censuses; out of these converts, as many as 60.3% came from the Serbian population. Duan Biladi illustrated the difference as follows: "If you wake an average Serb from Croatia up in the middle of the night and ask him what his national state is, he will say `Yugoslavia.' If you wake a Croat up and ask him the same, he will say `Croatia.'" 43 The reasons for going from Serb to Yugoslav were apparently varied, and certainly anything but straightforward. In the case of Croatia, some analysts have suggested that the increase in Yugoslavs from 84,118 to 379,057 (from 1.9% of Croatian citizens in 1971 to 8.2% in 1981) consisted largely of Serbs induced by the nationalist movement of the Croats in the 1970s to temporarily deny their ethnic identity by declaring themselves as Yugoslavs. 44 A perceived nationalist competitor, in other words, apparently led Serbs to opt for a sort of assimilation a declaration of allegiance to the most general collectivity to alleviate differences within it. This suggests that minority nationalities within a republic will tend to hide their minority status by identifying with a social group that transcends both nationalities and these republics. Furthermore, the data suggests a flipside to that coin: clear national majorities are less likely to call themselves Yugoslavs and more likely to affirm a

43 44

Biladi 1993, 119. Spasovski et al. 1995.

32

nationalist category. In the 1981-1991 period, declines in Yugoslavs within the Republic of Serbia were recorded in homogenous Central Serbia, but not in the diverse and heterogeneous provinces of Kosovo and Vojvodina; in the latter two cases, non-Serbs tended to declare themselves Yugoslavs more than Serbs did. Members of the minority Albanian and Hungarian communities were more likely to be Yugoslavs, while Serbs constituting decisive majorities were less so. Why hide behind the Yugoslav category if youve got noone to hide from? If ones national identity is in the majority, one might as well affirm it. Notwithstanding this reasoning, other apparent motives for adopting a Yugoslav identity seem to contradict such explanations. Namely, the general drop in Yugoslavs in all the republics from 1981-1991 (excluding Macedonia, for which data is unavailable) is widely believed to be a direct result of heightened ethnic and religious tensions, for majorities and minorities alike. Primarily in Croatia and Slovenia, but also in Serbia, people who had been Yugoslavs retracted to their original identities in response to perceived conflicts with the rivals of such identities. Far from assimilating, minorities (Serbs in Croatia, Albanians in Kosovo, and every nationality in Bosnia-Herzegovina) seem to affirm their nationality in response to rising tensions with hostile majorities in their republics. The striking differences in growth rates of Yugoslavs between the decade of 1971-1981 and 1981-1991 is, to be sure, largely a result simply of Titos death, the symbolic discrediting of the Yugoslav idea, a loosening of single-party directives for suppression of nationalism and the like. A national minority feeling outnumbered and threatened by another nationality could no longer express loyalty to a broader collective called Yugoslavia, for such a collective was looking increasingly politically unstable, economically weak, and militarily incapable of protecting minorities if hell were to break loose. Nevertheless, it remains remarkable that tens of

33

thousands of Serbs apparently changed their identities twice in twenty years for incoherent reasons. Large numbers of Serbs from Dalmatia and Slavonija, for instance, seem to have passionately turned Yugoslav in 1981 in response to increasingly bitter relations with their Croatian co-citizens and yet, come 1991, seem to have metamorphosed back into proud Serbs in response to even greater tensions with Croatian nationalism in the area. A more localized picture of the distribution of nationalities can perhaps explain this paradox. Usefully, Appendix #1 shows subtleties according to ethnic settlements within republics and provinces, which the census data above ignores. The existence of peaceful multinational coexistence as reflected in numbers of mixed marriages, multi-ethnic schools, heterogeneous workplaces and the like are not evenly distributed within provinces or republics. These maps show that, almost without exception, the rise of nationalist identity is negatively correlated with peaceful ethnic mixing in a given territory. In other words, the more tense ethnic relations were in a given territory in a given decade, the less likely citizens are to affirm their Yugoslav-ness. Hence the maps show that self-proclaimed Yugoslav Serbs in the Republic of Serbia were mostly on the frontier areas of south-eastern Serbia towards Bulgaria, parts of Vojvodina with homogenous Hungarian communities, and other areas of contact with populations with whom Serbs have had historically high levels of ethnic tolerance. While Bulgarian and Hungarian nationalisms were practically nonexistent in the decades leading up to 1981, the Albanian nationalist movement was in full swing and had already generated Serbian-Albanian violence in Kosovo in the early 1970s. Accordingly, the number of Yugoslavs in the Serb-Albanian contact zones was miniscule, as it was in areas of the Republic of Serbia with Muslim constituencies. Historical contextualization is therefore essential, along with sensitivity to localized differences i.e. an acknowledgment of the

34

variance among Serbs within the same province or republic, let alone between those from differing ones. A provisional but noteworthy conclusion can be drawn about Serbian national identity from these data. Throughout the latter half of the XX century, Serbs appear to have an especially strong investment in Yugoslav identity they adopt it more in relative and absolute terms from other nationalities, tend to adopt it in areas of mixed nationalities more than comparable populations in such areas, and are less likely to abandon it in return to original identity in the face of perceived threats from rival nationalities.45 Insofar as numbers of declared Yugoslavs indicate the presence of multiple identities and the absence of nationalism, a striking segment not only of Serbs but Yugoslav citizens in general remained nominally anti-nationalist by 1991. To take the example of a republic that was said to have the highest rate of inter-ethnic marriage in all of Europe: even as nationalism began looming in Bosnia-Herzegovina, as many as 326,000 citizens refused to declare themselves as one or another nationality or religion, remaining simply Yugoslavs in 1981. A decade later, when nationalism had turned into outright violence and massacre along ethnic lines, the number still remained as high as 239,845. Nevertheless, these census responses alone tell very little about the development of nationalist or, in fact, any political belief; declaring ones nationality can be a personal, cultural and perhaps even arbitrary choice, irrelevant of political views or perceptions of differences between nationalities. Appendix #1 shows that declared Yugoslavs in general were mostly concentrated in urban areas, perhaps suggesting that they have above-average45

This strong Serbian attachment to Yugoslav-ness was also reflected in a separate public opinion poll that reported that (at the height of conflict in 1992-1993) slightly more Serbs favored a united Yugoslavia than a purely Serbian state: 34% reportedly favored the old Yugoslav arrangement with Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Macedonia in a single state while about 31 percent favored a Union of Serbian lands. Needless to say, not a single other nationality even came close to favoring the preservation of Yugoslavia. Cited in footnote #7 of Simi 1997.

35

educational levels and social statuses, leaving them unrepresentative of the core mass constituencies of the nationalist movements that tore Yugoslavia apart. Even more importantly, the data leave us speculating about the potential nationalist interpretations and meanings attached to Yugoslav identity. Large numbers of Serbs may have sworn their loyalty to Yugoslavia under the assumption of Serbian hegemony within it, not as a benevolent expression of multi-ethnic tolerance. Indeed, as nationalists of all sides have argued, Yugoslavism might be a faade for nationalist dominance of one group over another. To approach these issues, we must look to another set of indicators of Serbian nationalism that identify specific values and political beliefs. Values and Voting Investigating what was in the heads of ordinary Serbs in the early 1990s is no easy task. State propaganda dominated media outlets, making content analysis of television and most newspapers highly unrepresentative. Even after the introduction of multi-party elections in 1990, the legacy of the Titoist single-party system was enormous, with the state silencing a vast majority of the population and allowing public visibility or voice only to a faithful minority that met the criterion of moral-political aptitude. 46 Prior to the establishment of Belgrades Strategic Marketing agency in the mid-1990s, no private agencies measuring nationalism or national issues in public opinion methodically even existed, and the notion of impartial political surveys was largely unheard of. What I rely on here, therefore, is one of the few available windows into the role of nationalism in Serbian public opinion in 19901992: the archives of the Center for Political Studies and Public Opinion Research (Centar zaMoralno-Politika podobnost was the prerequisite not only for all those associated with the Union of Communists of Yugoslavia (SKJ), but for everyone from janitors to university professors. A rigorous filtering process left all those deemed morally-politically inept completely outside the public arena at best and imprisoned for counter-revolutionary activity at worst.46

36

politikoloka istraivanja i javno mnjenje, CPIJM), an association of the Belgrade-based Social Science Institute (Institut drutvenih nauka). It conducted two national public opinion surveys in 1990 and 1992, one regional public opinion survey for Serbia in 1992, and two pre-electoral regional public surveys in 1990-1991 and in 1992 (with three survey waves each). In addition, CPIJM published a volume on the Cross Cultural Analysis of Values and Political Economy Issues, 1990-1993 in which several chapters deal with Yugoslavia and Serbia specifically. 47 Finally, I rely on second-hand analysis of CPIJM data conducted by two scholars investigating components of Serbian political culture and its relation to support for political parties. This work not only reproduces otherwise unavailable CPIJM findings, but also produces its own valuable statistics drawing on supplementary sources on electoral preferences and independent surveys. 48 Like Churchills democracy, this indirect approach to measuring nationalism is the worst possible aside from all its alternatives. Most generally, a value crisis appears to have swept Yugoslav society by 1990 in the words of political scientist Ljiljana Baevi, a moral vacuum, anomy and conflict of values that left deep scars on the consciousness of [Yugoslavias] citizens. 49 The crisiss central feature was widespread abandonment of purported Communist values and those associated with state socialist ideology. From 1981 to 1991, the number of people expressing favorable views of self-management the prided model of Yugoslavias independent socialist experiment dropped by more than half. Over 90% of the population had favored the policy of nonalignment; barely 25% did so in 1991. The popularity of social ownership over other types of property distribution, which had stood at an indoctrinated 65%, plummeted to less than 10%, with more than half the population in favor of a market47 48

Voich and Stepina 1994, 119-197. Panti and Pavlovi 2006, 120. 49 Voich and Stepina 1994, 120.

37

economy. 50 Aside from a merely ideological or philosophical disturbance, this value crisis had colossal implications for identity. An entire system of indications and reasons for who we are, who we can be, why we belong to one collectivity as opposed to another, how they can be our brothers despite differing dialects, religions, etc., simply collapsed. Like all abrupt disappearances of an identity and its accompanying values, this one needed replacement. In a comment highly applicable to the discussion of census data above, Baevi wrote that: These trends [of abandonment of professed communist/state socialist ideals and towards a value crisis] are reflected in phenomena such as the retreat into privacy, a return to religion, ethnocentrism, cynicism, and an external loss of control. In the general breakdown of value systems and the resulting confusion, identification with traditional social groups and institutions is a logical reaction. This takes the form of a socalled [sic] return to national concerns and religion, which are depicted and regarded as a refuge and salvation from the social and individual crisis. How likely this return is varies, we saw earlier, with the levels of perceived insecurity and potential for violence along national lines in the environment of the constituency in question. Few things can generate the kind of confusion, loss of control and crisis that intensified ethnic violence can, and few settings are better for a transformation of values than a community under (real or imagined) threat. But what are the values in question? An extensive survey of value priorities was carried out in May-June 1990 on a representative sample of 18+ year-olds in all republics and provinces. Although the research was designed to create an index of so-called materialist vs. post-materialist values, certain elements of the survey can be selected for our purposes here. From data for the

50

Voich and Stepina 1994, 121.

38

broader Yugoslav public, the following can be extrapolated for Serbs according to provinces and republics:Table 1.3. Value Priorities of Serbs in 1990 Goals Serbia Bosnia Croatia Kosovo Vojvodina Others TOTAL Economic growth 46 51 67 16 47 29 47 Strong state 34 33 15 59 42 40 34 More respect for 12 12 10 16 7 16 11 will of the people Make cities, 4 2 1 3 2 13 3 countryside cleaner and more beautiful Maintaining order 49 61 60 29 55 53 52 Give people more 15 12 15 22 10 16 14 say in government Fight rising prices 22 18 15 22 24 18 21 Protect free speech 10 3 1 19 8 11 8 Note: Within each of the two sets of four goals, respondents were asked to make two ranked choices. Figures shown represent the percentage choosing the given goal as first in importance. Undecided and dont know were omitted. Source: Vasovi 1994.

The Kosovo Serbs immediately leap to our attention, with a record 59% prioritizing a strong state. With high levels of perceived insecurity from actual Albanian pressure or otherwise and significant emigration rates into Serbia proper, Kosovo Serbs apparently embraced the prospects of a firm government hand to protect them against the separatist majority. It is also safe to assume that the heightened emphasis on giving people more say in government did not refer to the Albanians. These southern Serbs also stressed freedom of speech, reflecting widespread sentiment that Serbs in Kosovo were not being heard or paid any mind from their supposed protectors in Belgrade (a state of affairs Slobodan Miloevi was to remedy to fantastic political advantage). Interestingly, the other two major areas where Serbs are a minority Bosnia-Herzegovina and Croatia prioritized a strong state far less frequently than their co-nationals in Kosovo. Granted, the minority status of Serbs in BosniaHerzegovina and Croatia was far less extreme, but the escalation of violence had already become enormous in these areas at the time of the survey (Serbs in Croatia were already

39

calling for autonomy and refusing to recognize the newly-elected nationalists). Instead of opting for a strong state, these Serb minorities favored maintaining order at roughly 60% each. The discrepancy is perhaps understandable because, intense as violent incidents could get in Kosovo, the prospects of outright military confrontation with Albanians were not immediate. Serbian forces effectively suppressed rioting and, more often than not, managed to reinstall general public order. The exodus of Serbs from Kosovo was, technically speaking, voluntary or unforced migration, induced by intimidation and violence, but involving a significant space for choice. 51 In contrast, the fleeing of Serbs from eastern Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina at the time was, quite literally, forced migration, sometimes chosen at gunpoint for lack of alternatives. Thus, Serbs faced with the prospects of immediate civil war (perceived rightly or wrongly) tended to prioritize maintaining order instead of a strong state, perhaps associating the latter with their hostile home republics as opposed to the state of Yugoslavia or even Serbia. The insecurity associated with being a minority in general, however, did highly correlate with the perceived need for order or a strong state as opposed to luxuries like free speech (only 1% and 3% in Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina, respectively) or advancing the beauty of cities (ranging from 1-3%). Economic issues, furthermore, are mostly on the minds of Serbs in peaceful areas and where they are comfortable majorities. Serbia proper and Vojvodina have the highest rates of Serbs concerned about rising prices. Like Kosovo, these areas were suffering the economic crunch of the 1980s most severely and significantly more than Croatian and Bosnian citizens, as is reflected in Table 1.3. Croatia is peculiar, however, in having the greatest share of Serbs voting overwhelmingly for a strong economy as the top priority (67%) unlike Bosnian

For an interesting discussion of the usefulness (or lack thereof) of the term forced in the rubric of forced migrations, albeit in a different context, see Brubaker 2001.

51

40

Serbs, they even prioritize this over maintaining order, despite comparable ethnic tensions. In this regard, Croatian Serbs are in agreement with Croatian citizens in general. In Kosovo, and Macedonia, Slovenia and elsewhere (Others), however, the Serbian minority gives little attention to economic issues. Although economic growth is a strong second priority in Vojvodina, for Serbs in Serbia and for all Serbs in general, a strong state remains perceived as more urgent. For our purposes, it may be useful to categorize the goals of Table 1.3 into two approximate poles: those value priorities conducive to Serbian nationalism and those unfavorable to Serbian nationalism, as defined here. In the first category, we may include those goals that seem to meet the desire for unity, stability, strength and protection against perceived threats (strong state and maintaining order). In the second category, we may include those goals pertaining to a higher living standard, political liberties, civic rights, economic issues and development (economic growth, cleaner and more beautiful countryside, cities, fight rising prices, free speech,). [Due to the ambiguous interpretations of more respect for will of the people and more say in government especially in Kosovo I exclude this goal from either category.] This opposition is not only sketched in accordance with the particularly authoritarian and statist dimensions of Serbian nationalism, but also reflects the basic dichotomy represented in parliamentary elections by two general party blocks. The dichotomy can give us at least a rough estimate of the extent of those values that were most compatible with (or vulnerable to appropriation by) nationalist mobilization along lines of Serbian-ness. Values conducive to nationalism were strong, but not absolutely dominant. Recall that respondents were asked to name the favorite value priority within each cluster of four

41

choices. Values conducive to nationalism indeed received either most or second-most preferences in both clusters; however, Serbs in general (total) and those from Serbia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia and Vojvodina specifically all voted for a value unfavorable to nationalism (i.e. economic growth) in the first cluster. In other words, only most Serbs from Kosovo and other places prioritized a value conducive to nationalism, and even these populations opted for non-nationalist priorities as a strong second-place preference. In the second cluster, most chose a nationalist value, with 52% of all Serbs calling for order more than those calling for all the other options combined. However, the range of alternatives in this category should be scrutinized. Particularly, fighting rising prices is far narrower than the more general economic growth in the first category that attracted so much interest. Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia and especially others (which includes prosperous Slovenia) were settings where Serbs were not particularly scarred by rising prices (like those hitting Kosovo, for instance), but were surely concerned with wages, unemployment, pensions and other aspects of economic growth. Therefore, the lack of a more general priority covering these concerns probably boosted the nationalist-friendly maintaining order value. The first category suggests that, if a worthy non-nationalist value was offered in the second cluster, the nationalist value that more than half of all Serbs prioritized might have seen a relative drop. In conclusion, value priorities conducive to nationalism were strong (though not absolute) and their dominance was conditional on the absence of a viable alternative, particularly one relating to economic growth and stability. 52 The real question, of course, is how these values translate into collective action and mobilization. Electoral preferences are the most immediate and testable reflections of this

This connects to a more general thesis that has argued that nationalist mobilization was not exclusively or even primarily based on appeals to ethnicity. See: Ganon 1994.

52

42

translation. Serbia held its second multi-party elections since World War II in December of 1992, with roughly 5 million voters (or 70% of the electorate) conveying their values to the ballot. The tension detected above between economic issues, political liberties and concerns about standards of living on the one hand, and a strong state, protection from violence, and order on the other was confirmed in a CPIJM survey of values of supporters of the major political parties in 1992. The general split of the party scene into two blocks (the so-called democratic oppositional one and the ruling communist-nationalist one) largely reflected this tension.Table 1.4. Values of Serbs According to Support for Political Parties in 1992 Value53

Socialist Party of Serbia (SPS)

Serbian Radical Party (SRS)

Democratic Party (DS)

Democratic Party of Serbia (DSS)*

Serbian Renewal Movement (SPO)*

NationalistCommunist Block (Average)

Democratic Opposition Block (Average)

Modernism Liberalism Tolerance Xenophobia Mandates

13 17 3 85 101

9 32 7 92 73

67 78 30 59 6

73 71 58 54

53 70 35 59 50

11 24.5 5 88.5

64.3 73 41 57.3

% of Votes 28.8 22.6 4.2 16.9 Note: Non-bold figures show percentages of respondents endorsing the given value. * Part of opposition grouping Serbian Democratic Movement (DEPOS), along with another small party; number of mandates won is the total for DEPOS. Source: CPIJM

As two analysts of these and similar data have pointed out, the crucial divide is between SPS and SRS on one side and the other three parties on another.54 Followers of the SPS-SRS expressed highest levels of xenophobia and lowest levels of tolerance, clear indicators of vulnerability to nationalist mobilization and aversions to pro-Western, reformist and liberal party platforms. DS and DSS followers were in the majority committed to modernism as opposed to traditionalism and liberalism as opposed to conservatism or communism. SPO,

An elaboration of the index of the value categories is available in the CPIJM study itself, though elaboration here is not necessary, as the categories are defined rather commonsensically. Detailed analysis of this table can be found in Panti and Pavlovi 2006. 54 Ibid, 53-56.

53

43

though markedly more nationalistic in its platform, has followers with values closer to DS/DSS than the ruling parties. The high levels of xenophobia in the opposition parties is somewhat surprising, but longer-term trend studies have shown that this is a non-intensive, reactive and fleeting phenomenon which is largely due to the pressures of the ongoing war in Bosnia-Herzegovina at the time. 55 Though the levels of tolerance for the DS and SPO are not as admirable as they might be, they are in fact above-average compared to the population at large: CPIJM found an average of only 22% of adult Serbs endorsing tolerance, with 53% displaying intolerance in 1992. The single-digit tolerance levels of the victorious parties suggest, therefore, that those who voted for the ruling parties are very unrepresentative of the entire population on the question of tolerance. Furthermore, those voting for the democratic opposition are above-averagely tolerant, especially DSS supporters. In general, the democratic opposition is significantly less attractive to voters with nationalist values than the ruling parties are, but considerable nationalist potential remains in the high levels of xenophobia (over half of all the supporters of the opposition). Simultaneously, however, the democratic block endorsed the anti-nationalist values of modernism and liberalism, conducive to democratic and reformist goals. On average, 57.3% of supporters of the democratic opposition expressed xenophobia, but 73% and 64.3% of them also expressed values of modernism and liberalism. The supporters of the ruling parties have, we may say, a more coherent value system, susceptible to authoritarianism and nationalist perspectives of non-Serbs. This incoherence of values among voters of the democratic opposition immediately suggests that the latter failed to present a coherent political message that would attract the primary concerns of the public. As we saw above, economic and nationalist issues can each55

Panti and Pavlovi 2006, 53-56.

44