Literature Review - ADAC · 2007-02-08 · Literature Review 1998 Melanie Lehmann Aboriginal Drug...

Transcript of Literature Review - ADAC · 2007-02-08 · Literature Review 1998 Melanie Lehmann Aboriginal Drug...

Literature Review

1998

Melanie Lehmann

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc.

Development of a Manual for the Detoxification andTreatment of Aboriginal Solvent Abusers

ISBN 09585204 7X

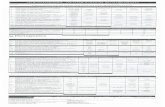

Table of Contents

Page

♦ Solvent Abuse 1

♦ Petrol Sniffing in Australia 2

♦ Prevalence 3

♦ Patterns of Use 4

♦ Reasons for Beginning Petrol Sniffing 4

♦ Petrol Sniffing and Australian Law 5

♦ Effects of Petrol Sniffing 6

♦ Acute Effects 6

♦ Mortality 7

♦ Morbidity 7

♦ Social Effects 10

♦ Treatment Approaches 11

♦ Community Health Worker Treatment Approach 11

♦ Hospital Based Treatment Approach 12

♦ Community Based Treatment Approaches 14

♦ Educational Approach 14

♦ Harm-reduction Approach 16

♦ Aversion Approach 16

♦ Outstation Approach 18

♦ Residential Approach 19

♦ Positive Alternatives Approach 20

♦ Family Influence Approach 22

♦ Other Approaches 23

♦ Review of Two Community Approaches to Petrol Sniffing 24

♦ The Healthy Aboriginal Life Team (HALT) 24

♦ The Petrol Link-up 27

♦ Overseas Approaches to Solvent Abuse 28

♦ A British Approach 28

♦ A Canadian Approach 29

♦ A South-East Asian Approach 30

♦ References 32

♦ Appendix A: Hospital Treatment Protocols 36

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 1

Solvent Abuse

Solvent abuse is the deliberate inhalation of gas or fumes given off from solvents

at room temperature for the intoxicating effect. Solvent abuse is observed

throughout the world in a variety of populations. Solvent abuse is different from

some other forms of substance abuse, in that, solvents are not illegal to use and

the age profile of the solvent abuser is much younger (Ives, 1994).

Most young people do not abuse solvents. In the UK, a recent review of

prevalence suggests that 4-8% of secondary school children have sniffed

solvents (Ives, 1994). In Australia, a 1992 survey of NSW Secondary School

Students found that 2.6% of girls and 3.1% of boys used inhalants every week

(Mundy, 1995). Studies in the United States indicate that approximately 5.7% of

high school students have used inhalants (National Institute on Drugs, 1988).

Specific ethnic minority groups appear to have much higher rates of solvent use

than the general population. A study of inhalant use among Eskimo school

children in Alaska reported a lifetime prevalence of 48 per cent (Zebrowski et al.,

1996). Similar prevalence rates have been reported in Native Americans,

Canadian Indians, and Mexican Youth (Zebrowski et al., 1996). In Australia, rates

appear higher in Aboriginal Australians. A recent study investigating the

prevalence of drug use in urban Aboriginal communities found that 8 per cent of

males and 4 per cent of females had sniffed petrol, which is significantly higher

than that reported in the general population (Perkins, 1994).

Within ethnic groups, prevalence rates vary depending on geographical location.

A recent Western Australian study investigated the use of tobacco, alcohol and

other drugs in young Aboriginal people in the rural town of Albany (Gray et al.,

1997). The study found that 16 per cent of the sample reported sniffing a variety

of substances. This is significantly higher than the rates reported in urban

Aboriginal communities (Perkins, 1994).

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 2

Similar ethnic variations are observed in relation to solvent choice. Young (1987)

noted that in North America, Hispanics preferred spray paints and Blacks

preferred corrective fluids. Similarly, petrol sniffing is particularly prevalent in

Canadian, American and Mexican Indians, Canadian Inuit, black South Africans,

Maoris and Australian Aboriginals (Brady, 1992).

Evidence of variation in solvent choice within an ethnic group is found in

Australia, with urban Aboriginal youth preferring toluene in the form of adhesives

and thinners, and Aboriginal youth living in remote rural regions preferring petrol

(Brady, 1992; Sandover, 1997). It is thought that youth in towns and metropolitan

areas have greater access to a wider variety of substances and this determines

the variation in substance choice (Gracey, 1998; Brady & Torzillo, 1994).

The variations in solvent abuse observed between and within populations

necessitates specialised approaches to treatment. The following section will

review the literature on petrol sniffing as occurs in Australian remote rural

Aboriginal communities with particular consideration to prevalence, aetiology,

laws, effects, treatment and intervention approaches.

Petrol Sniffing in Australia

Petrol sniffing is the deliberate inhalation of petrol fumes for the intoxicating

effect.

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 3

Prevalence

Petrol sniffing has been recognised in Australia for more than 50 years, with the

larger remote rural Aboriginal communities being the most affected. Variations in

prevalence across the remote rural regions are evident with Central Australia, the

Eastern Goldfields in Western Australia and West, Central, and East Arnhem

land in the Northern Territory being the areas of greatest use (Brady, 1992).

Young men are the greatest abusers of petrol with the ratio of males to females

being approximately 3 to one (Brady & Torzillo, 1994; Mosey, 1997). The age of

users range from 8 to 30 years (Brady & Torzillo, 1994). Interestingly, the age of

petrol sniffers seems to be increasing with the greatest proportion of users being

in the 20 to 25 year old age group (Roper & Shaw, 1996). This is likely due, in

part, to the particularly high proportion of chronic sniffers observed in the older

age groups (d’Abbs, 1991).

It is extremely difficult to determine the number of young Aboriginals engaged in

petrol sniffing with much accuracy. Rates of use reported are based on

observation and self-reports, which are known to be inaccurate. Moreover, petrol

sniffing appears cyclical with the practice flourishing and dying down over periods

of time (Brady, 1989; Garrow, 1997; Gray et al., 1997). Factors noted to correlate

with changes in prevalence include seasonal weather variations, the presence of

ringleaders, school holidays and changes in community population (Brady,

1992).

Indeed, the majority of young Aboriginals do not sniff petrol. Brady (1992)

believes that only a very small proportion of young Aboriginals engage in the

activity. Also, there appears to have been a reduction in the number of young

Aboriginals sniffing petrol. In 1984, it was estimated that 10 per cent of the total

population in the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Lands were petrol sniffers, whereas, in

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 4

1995 estimates had reduced to 3.8 per cent (Roper & Shaw, 1996). Analyses of

these results indicate very little recruitment over the decade.

Patterns of Use

As with solvent abusers, petrol sniffers can be distinguished by their patterns of

use with experimental, social (occasional) and chronic sniffers contributing to the

total population. Unlike most solvent users who are experimenters, many

Aboriginal petrol sniffers appear to be chronic users (Chalmers, 1991). Brady &

Torzillo (1994) reported that in the AP lands approximately 50 per cent of 10-14

year old users in 1980 continued to sniff petrol at 25-29 years of age. Similarly,

current sniffers in a recent study in the Maningrida community reported sniffing

for a mean duration of 8 years (Burns et al., 1995).

Reasons for Beginning Petrol Sniffing

Numerous reasons for beginning petrol sniffing have been suggested in the

literature. Poverty, cultural and family breakdown, peer pressure, boredom,

pleasure and the lack of apparent health sequelae for ex-sniffers being the most

frequently cited (Burns et al., 1995; Brady, 1992; Brady & Torzillo, 1994; Gracey,

1998; Hayward & Kickett, 1988).

Aetiological explanations of petrol sniffing emphasising cultural and family

breakdown have been criticised. Indeed, Brady (1989) observes that many petrol

sniffers come from well respected, caring families. Furthermore, factors common

to other forms of adolescent substance abuse such as physical and mental

pleasure, risk taking behaviour, and feelings of autonomy appear to be of greater

significance. Notably, all sniffers consulted in the Senate Select Committee on

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 5

Volatile Substance Fumes (1985) reported ‘fun’ as the reason for engaging in the

activity.

Burns (1996) considered the aetiology of petrol sniffing and presented a well

integrated view concluding:

“Like native American youth, the degree of social disadvantage

experienced by Aboriginal youth through poverty, prejudice and the lack of

economic, educational and social opportunities may increase their

susceptibility to drug use but may also be accompanied by factors

common to other adolescents which make them vulnerable to harmful

drug use.”

Petrol Sniffing and Australian Law

Only two regions of Australia, the Pitjantjatjara Lands in the northwest of South

Australia and the Ngaanyatjarra Lands in Western Australia, currently have laws

specifically concerning petrol sniffing.

In South Australia, by-laws under the Pitjantjatjara Land Rights Act 1981 make it

an offence to possess or supply petrol for the purposes of inhalation. An

amendment to the Act in 1987 also gives police the power to confiscate and

dispose of any petrol or containers suspected as being used for the purpose of

inhalation.

In Western Australia, there are by-laws in the Ngaanyatjarra Lands that restrict

the supply, possession and use of deleterious substances, including petrol.

In the Northern Territory, under section 18 of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1993, it is

illegal to sell or supply petrol to anyone when it is known or should be known that

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 6

the person will use it as a drug or supply it to someone else to use as a drug.

Also, under the Northern Territory Community Welfare Act, a petrol sniffer under

18 years of age can be declared ‘in need of care’ and dealt with through statutory

child protection.

Effects of Petrol Sniffing

The effects of petrol sniffing are widespread and not limited to the individual.

There are also significant social consequences for families and communities.

In 1985, the Parliamentary Senate Select Committee on Volatile Substance

Fumes identified petrol sniffing as the ‘most intrinsically hazardous form of drug

abuse, being more dangerous than amphetamines, alcohol, tobacco, barbiturates

and heroin’ (Commonwealth of Australia, 1995).

Acute Effects

Petrol consists of a complex range of toxins including hydrocarbons such as

benzene, toluene and xylene. The acute effects of petrol intoxication are largely

due to the action of such hydrocarbons on the central nervous system. Sniffers

experience feelings of mild euphoria and excitement similar to that of alcohol.

Many individuals also report hallucinations and delusion with high levels of

intake. Accompanying the initial high are the unpleasant effects of nausea,

vomiting, dizziness, staggering gait, irritation of the eyes, excessive sensitivity to

light and confusion (Morice et al., 1981). Following these initial effects,

individuals experience drowsiness with the highly intoxicated progressing into

unconsciousness and sometimes coma. A more extensive account of the acute

effects of petrol inhalation is given in Morice et al. (1981).

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 7

Mortality

The major cause of death associated with petrol sniffing is aspiration pneumonia

although a number of deaths are cardiac or burns related (Brady, 1995;

Goodheart & Dunne, 1994). Unfortunately, the mortality associated with petrol

sniffing is extremely difficult to ascertain. Death is often attributed to the

presenting cause, such as pneumonia, and not recorded as associated with

petrol sniffing.

The most recent data on deaths associated with petrol sniffing is from the

National Drug Abuse Information Centre (NDAIC) for the period between 1981-

1988. Twenty deaths were attributed to petrol sniffing in the reporting period

however the number of Aboriginal deaths amongst these was not determined.

Brady (1995) suggests that NDAIC severely underestimated the true number of

petrol sniffing deaths and that the majority were Aboriginal people. Indeed, this

idea is supported by a study which reported that 18 of the 20 chronic sniffers

admitted to a Perth hospital with severe illness were Aboriginal (Goodheart &

Dunne, 1994).

Morbidity

Fortunately, short-term experimental petrol sniffing does not appear to result in

irreversible long-term detrimental health effects. The outcome of chronic long-

term petrol sniffing, however, is not as favourable. Arguably, the most significant

long-term effect of chronic petrol sniffing is cognitive dysfunction (Brady &

Torzillo, 1994; Goodheart & Dunne, 1994; Maruff et al., 1998; Valpey et al.,

1978). Other common long-term physiological effects include chronic tissue

irritation of the respiratory system, nutritional disturbances, anaemia, foetal

abnormalities and cardiac, liver and renal dysfunction (MacGregor, 1997).

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 8

The major contributor to long term adverse effects of petrol sniffing is thought to

be tetraethyl lead in leaded petrol. However, neurological damage can also occur

from the toxic aromatic hydrocarbons, such as toluene, that are present in petrol

(Morrow, 1992). The exact contribution of lead as opposed to these other

components of petrol is yet to be determined and a point of vigorous debate

among researchers.

A recent study investigated the neurotoxic effects of both unleaded and leaded

petrol (Burns et al., 1996). The study found that both unleaded and leaded petrol

were neurotoxic with neurocognitive deficits being related to the duration of

exposure. However, neurological deficits were observed to be more widespread

in users of leaded petrol as were hospital admissions. This study also

investigated the possibility of physical improvements with abstinence. It was

found that abstaining from petrol sniffing was associated with improvements in

neurological functioning with the degree of improvement being related to the

length of abstinence.

The most recent study investigating the neurological and cognitive abnormalities

associated with chronic petrol sniffing is that by Maruff et al. (1998). This study

compared 33 current sniffers, 30 ex-sniffers and 34 matched non-sniffers and

found that current sniffers showed higher rates of cognitive and neurological

abnormalities than non-sniffers. Ex-petrol sniffers showed similar deficits as

sniffers, however, these were not as widespread. This finding suggests that there

may be some improvement in functioning with abstinence, which is in

accordance with the results of Burns et al. (1996). When analysed, blood lead

levels and length of time sniffing were significantly correlated with the magnitude

of neurological and cognitive deficits.

Differences have been observed in the presentation and outcome of acutely

intoxicated versus chronic petrol sniffers. Goodheart and Dunne (1994)

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 9

investigated petrol sniffers encephalopathy in 25 patients admitted to Perth

teaching hospitals. Twenty patients were chronic sniffers and five presented with

acute petrol intoxication. The acute patients generally presented with altered

states of consciousness and were ataxic, whereas, the clinical features of the

chronic patients were far more extensive. The outcome for the acute patients

was far more favourable than that of the chronic patients. All acute patients

recovered within 24 hours whereas 8 out of the 20 chronic petrol sniffers died.

Furthermore, only one of the surviving chronic petrol sniffer was functionally

independent on discharge. Similar to the findings of Maruff (1998), blood lead

levels on admission were correlated with poor prognosis.

The disabling effects of petrol sniffing are widespread and severe disability is not

uncommon (Mosey, 1997). Disability from petrol sniffing results mostly from

damage to neural networks and their connections. More specifically, the

incoordination often observed in petrol sniffers appears to result from damage to

cerebellum, pyramidal tracts and areas of frontal cortex. Similarly, memory

deficits probably result from damage to discrete areas of temporal lobe and

cerebellum (Burns et al., 1996). Accidents and self-inflicted harm associated with

intoxication also make a significant contribution to disability.

Psychological sequelae have also been observed in chronic sniffers. The most

common including personality disorders, apathy, mood swings, depression and

paranoid thinking. Psychological dependence is also common among chronic

sniffers. Although physical dependence is rare, withdrawal can occur and

symptoms include dizziness, tremors, nausea and seizures (MacGregor, 1997).

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 10

Social Effects

Petrol sniffing adversely effects the communities in which it occurs. The Royal

Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody found that the impact on

communities affected by petrol sniffing can be ‘massive and destructive’

(Commonwealth of Australia, 1991). It is most often the social disruption and

vandalism caused by sniffers which instigates intervention attempts (d’Abbs,

1991).

The families of petrol sniffers suffer tremendously. Feelings of loss and shame

are widespread and alienation from their community is common (Brady, 1992).

Crime among Aboriginal youth related to petrol sniffing is considerable. In the

Northern Territory, there were 131 juvenile offences associated with petrol

sniffing between January 1986 and June 1989, which represents 9.4% if the total

offences for that age group (Brady, 1992). A recent study by Burns et al. (1995)

found that 80 per cent of ex-sniffers and current sniffers reported having ‘been in

trouble with the police’ as a direct result of petrol sniffing.

The financial burden on the Aboriginal communities affected by petrol sniffing is

substantial. Sniffers continually damage buildings, including homes and

businesses. Moreover, the cost of caring for a disabled sniffer can be as much as

$100, 000 annually (Mosey, 1997). A recent estimate of disabled ex-sniffers in

the cross-border areas of NT, SA, and WA was forty three, however, the true

numbers are likely to be significantly higher (Mosey, 1997).

High levels of sexually transmitted diseases have been observed in affected

communities. Petrol sniffers report increased libido and risk taking behaviour

when intoxicated (Burns et al, 1995).

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 11

Treatment Approaches

The recent report on petrol sniffing in Central Australia by Central Australian

Alcohol and Other Drug Services (Mosey, 1997) stated that:

“…all communities and service providers wanted to be trained in how to

deal effectively and safely with sniffers both when they were affected by

the substance and at a later date.”

Treatment approaches to petrol sniffing will be considered according to three

perspectives; (1) the community health worker; (2) the hospital; and (3) the

community.

Community Health Worker Treatment Approach

Community care facilities are the first point of reference for most petrol sniffers

(Brady, 1992). On presentation individual needs are assessed. Severely ill

individuals need to be stabilised and quickly evacuated to a critical care facility.

The major concern for community health staff and evacuation teams in such

situations is protection of the airways (Currie et al., 1994). Fortunately, most

petrol sniffers present with the less serious effects of fits, hallucinations,

uncontrollable behaviour, minor burns or infections. These individuals can be

adequately treated in community care facilities.

The Central Australian Rural Practitioners Association (CARPA) manual (1997)

provides the best treatment protocol available for health workers in community

care facilities. According to the CARPA manual there are 3 main presenting

problems associated with solvent abuse: (1) Fits; (2) Strange and violent

behaviour; and (3) Weakness and Infection. The CARPA protocols for the

treatment of these problems are outlined in the CARPA Manual.

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 12

The literature suggests that burns are also a common presenting problem for

petrol sniffers. Although burns are not included in reference to solvent abuse in

the CARPA manual, a protocol for the treatment of burns is found elsewhere in

the manual.

Hospital Based Treatment Approach

Hospital based treatments are appropriate for individuals suffering serious

symptoms of petrol sniffing. Regional hospitals deal with most of the serious

cases however those who are more severely ill are transferred to tertiary referral

hospitals (Goodheart & Dunne, 1994).

The serious acute effects of petrol sniffing such as convulsions, coma and

cardiac arrhythmia all require hospitalisation and treatment is symptom

appropriate (Morice et al., 1981). Severe burns and other serious injuries

resulting from petrol sniffing may also require hospitalisation. The treatment

protocols for all such cases are agreed upon in the medical profession. For those

individuals presenting with the chronic effects of lead intoxication agreement on

treatment is less widespread. The general protocol appears to be airway

stabilisation followed by chelation therapy. The Royal Darwin Hospital and the

Alice Springs Hospital both have protocols for the treatment of petrol sniffers

(See Appendix A).

Chelation therapy aims to reduce serum levels of lead using chelating agents.

Chelating agents are chemical compounds that bind to heavy metals including

lead. The most common chelating agents are Calcium disodium edetate (EDTA),

British Anti-Lewisite (BAL) and D-Penacillamine. Although use of the chelation

therapy is widespread both overseas and in Australia, there is uncertainty over its

effectiveness (Brady, 1992). A number of Australian studies have investigated

this issue.

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 13

Currie et al. (1994) studied 70 petrol sniffers evacuated to the Royal Darwin

Hospital with encephalopathy (degenerative disease of the brain). The primary

emphasis of treatment for these individuals was airway management followed by

chelation therapy using calcium EDTA and dimercaprol. These researchers

support the use of chelation therapy for lead intoxication as it appears to hasten

recovery in hospital and reduces the amount of lead in the body (Currie et al.,

1994). They do acknowledge that this lead mobilisation is sometimes

accompanied by neurological deterioration, however, this appears to be

temporary in nature.

An evaluation of hospital based treatments for severely ill petrol sniffers by Burns

& Currie (1995) included an evaluation of chelation therapy as a means of

mobilising inorganic lead. The study found that lead was mobilised and excreted

through the use of chelation therapy with a decrease in blood lead levels. They

emphasised that airway management and vigilance against sepsis was critical in

survival. This is in accordance with the results of others.

A less favourable appraisal of chelation therapy was given by Goodheart and

Dunne (1994). In their investigation of petrol sniffing encephalopathy in 25

patients the outcome of treatment was reported as ‘extremely disappointing’.

Forty per cent of the chronic patients treated with chelation therapy died. The

direct causes of death were cardiac arrest or respiratory failure due to

pneumonia.

Berry et al. (1993) calculated that by the year 2000 the use of leaded petrol in

Australia would fall well below 15%. With the increasing introduction of unleaded

fuel to remote areas of Australia it is likely that the number of hospitalisations for

acute petrol encephalopathy will fall, as evidenced in the Maningrida study, and

hence the need for hospital based treatments focusing on lead intoxication (eg.

chelation therapy) will wain.

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 14

Since the major cause of death for petrol sniffers is sepsis, particularly aspiration

pneumonia, this will continue to be a problem with unleaded petrol and should

therefore be the focus of hospital based treatments. According to d’Abbs (1991)

treatment for chronic sniffers should also include intensive physiotherapy, to help

restore wasted muscle and overcome the symptoms of neuropathy.

Community Based Treatment Approaches

Community based approaches to substance abuse have recently experienced a

growth in popularity throughout the world. The work of Martien Kooyman, a Dutch

psychiatrist, has been fundamental in this change. Kooyman (1993) evaluated

the therapeutic community approach and found that the involvement of families

and the larger community acted as a curative mechanism in substance abuse.

Various community approaches have been employed to address the problem of

petrol sniffing in Australia. The major approaches will be outlined here.

Educational Approach

One would assume, after all the work undertaken in the area of petrol sniffing

including education, that communities would now be aware of its detrimental

effects. Nevertheless, a recent report on petrol sniffing in Central Australia

(Mosey, 1997) stated that:

“ All community organisations, families and service providers expressed

concern at their lack of knowledge of the physical effects of inhalant abuse

on the body. They wanted information on the physical, neurological and

social effects of petrol sniffing…”

The same report also stated that:

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 15

“There was concern at the lack of teaching aids …and all communities

asked for videos about petrol sniffing…”

Indeed, it appears community education is still an area that needs to be

addressed.

Educational material has primarily focused on the detrimental health effects

associated with petrol sniffing. The Senate Select Committee into Volatile

Substance Abuse concluded that such ‘scare tactics’ were unlikely to be effective

in reducing petrol sniffing. Fortunately, a number of other approaches have been

taken.

Videos produced by communities in response to the petrol sniffing problem have

been valuable. The focus of the material has been varied. The Yalata community

made a video called “Petrola Wanti”, which shows how they reduced petrol

sniffing in their community. Two videos produced in Western Australia have

taken a more educative approach. One video “Care about Yourself” includes

information on caring for friends, fitting, harm reduction, identifying healthy

alternatives to petrol sniffing and identifying adults to notify if problem occurs.

The other video “Your’e the Boss” focuses primarily on the legal implications

associated with petrol sniffing.

The Petrol Link-Up project developed “The Brain Story”. The brain damage

resulting from petrol sniffing is shown through a series of laminated posters. This

educational approach has been very popular throughout the remote Aboriginal

communities (Shaw, 1994).

A School Drug Education Approach has been implemented in WA. Through the

program children are educated about drugs, including petrol sniffing, as part of

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 16

their school curriculum. This approach is limited to those communities where

petrol sniffing occurs, as exposure to the unaware is not desirable.

Future educational approaches would do well to focus on the effects petrol

sniffing has on physical co-ordination, particularly in relation to sporting activities.

This was an area of concern for petrol sniffers in the Burns et al. (1995) study of

strategies to reduce petrol sniffing in an Aboriginal community.

Harm-reduction Approach

Some Aboriginal communities have taken a harm reduction approach and have

introduced unleaded petrol as an alternative to leaded petrol. Maningrida is one

such community located 300km east of Darwin. The introduction of unleaded

petrol for a 3 year period in Maningrida resulted in a reduction of hospital

admissions from 40 in the period 1984-1988 to zero in the study period of 1990-

1993 (Burns et al., 1996). Indeed, communities would benefit from replacing

leaded petrol with unleaded petrol but volatile hydrocarbon toxicity still remains a

problem.

Aversion/Preventive Approach

The introduction of aviation fuel (AVGAS) as a substitute for petrol is an

approach implemented by as many as 25 remote Aboriginal communities.

AVGAS is not an attractive alternative for petrol sniffers as it causes severe

headaches and abdominal cramping when inhaled (Burns et al, 1994; Burns et

al., 1995). A number of studies have evaluated the effectiveness of AVGAS.

Burns et al. (1995) evaluated the AVGAS strategy in the Maningrida community.

Eleven non-sniffers, 11 ex-sniffers and 18 petrol sniffers participated in a 20-

month follow–up. The researchers reported that following the introduction of

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 17

AVGAS, petrol sniffing ceased, community crime was reduced and employment

increased significantly.

The Petrol Link-Up project (Shaw et. al., 1994) evaluated the introduction of

AVGAS as an alternative fuel to petrol in a number of remote regions throughout

Central Australia. The project found that the introduction of AVGAS was

successful in reducing and eliminating petrol sniffing in some communities yet

not others. Success appeared to be related to the proximity of alternative sources

of petrol. This idea is supported by others (Roper & Shaw, 1996; Commonwealth

Department of Health and Community Services, 1998).

A project in the Anangu and Pitjantjatjara Lands found that the introduction of

AVGAS was significant in the reducing petrol sniffing between 1994 and 1995

(Roper & Shaw, 1996). Moreover, there was a significant decrease in petrol

sniffing related offences. Interestingly, there was no change in the number of

petrol sniffing related evacuations by the Royal Flying Doctors Service. This

finding suggests that AVGAS does not prevent chronic sniffers from obtaining

petrol.

An obstacle to the success of AVGAS is the importation of petrol into

communities. Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal residents are reported to be involved

in the activity (Roper & Shaw, 1996). Moreover, there is evidence that the

parents are providing their children with petrol. This practice is thought to be a

result of despair, desperation and fear on the part of the parent and threats of

violence and self-harm from the child (Commonwealth Department of Health and

Community Services, 1998).

Although most remote Aboriginal communities are now using AVGAS the petrol

sniffing problem persists. Unfortunately, AVGAS alone cannot solve the petrol

sniffing problem. Indeed, this strategy has been effective in a number of

communities yet success appears dependent on the proximity of alternative

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 18

sources of petrol. A multi-modal approach, which includes AVGAS seems most

likely to be successful in reducing petrol sniffing.

The Australian government has recently increased the excise on AVGAS from 13

cents per litre to 45.242 cents per litre for non-aviation purposes. This move has

caused uproar in Aboriginal communities who fear a worsening of the petrol

sniffing problem. At present, it appears that communities already using AVGAS

will be subsidised, however, others wanting to implement the strategy will have to

pay the full excise.

Outstation Approach

Outstations are small settlements on traditional homelands where Aboriginal

people are encouraged to engage in traditional activities. From the literature the

major functions of outstations in relation to petrol sniffing are: (1) to remove

current sniffers from sources of petrol in an attempt to detoxify them; (2)

rehabilitate individuals who have developed disabilities as a result of petrol

sniffing; (3) provide respite to communities.

The report on Petrol sniffing in Central Australia (Mosey, 1997) stated that:

“communities generally expressed this (outstation respite services) as

one of their preferred strategies.”

Indeed, outstations have been shown to be an area where petrol sniffing does

not occur (Eastwell, 1977; Commonwealth of Australia, 1987).

Many programs for petrol sniffers have been implemented on outstations,

however few have continued for a substantial period of time. The Mt. Theo

outstation near Yuendemu is an exception and is a good example of the general

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 19

concept of outstations. Fortunately, Mt Theo has recently acquired further

funding from the Federal Government. The Injartnama outstation near Ntaria has

also received funding to expand youth activities and to work with families, as has

the Ilpurle oustation near Kings Canyon.

A number of short-comings of outstations have been outlined in the literature.

These were publicised in the coronial inquest into the death of a young petrol

sniffer in Alice Springs (Donald, 1988). The major limitations identified were the

lack of telecommunication facilities and reliable vehicles on outstations and

limited or non-existent First Aid skills among Outstation workers. These

limitations could prove fatal in medical emergencies. The Petrol Link-up project

produced a document entitled “The Missing Link” which can be used as a manual

for outstation programs and aims to address these inadequacies (Shaw et al.,

1994).

Indeed, most Aboriginal communities believe that the outstation movement is one

of the most powerful strategies against petrol sniffing. This is significant as

community support for an approach is consistently cited in the literature as one of

the most influential factors in ensuing success.

Residential Approach

Throughout all remote Aboriginal communities there is strong sentiment that

children should be helped in their communities (Mosey, 1997). Taking children

away from their homelands to residential care facilities is not generally

supported. The success of this approach has been limited with most petrol

sniffers returning to the practice when they return to their community (Divakaran-

Brown & Minutjukur, 1993).

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 20

A residential rehabilitation facility that has evidenced some success is the

Gordon Symons Centre in Darwin (d’Abbs, 1991). Between 1985 and 1990 the

centre offered an Education recovery program for men with alcohol or petrol

sniffing problems. Treatment was based on: (1) the disease model of substance

abuse and (2) the theory that family/kin networks are both the source of

substance abuse problems and the solution.

The program lasted for four or eight weeks and included family group therapy,

access to Alcoholics Anonymous, cultural activities, and spiritual activities.

Follow-up visits were provided with counselling continuing in the home

community.

According to d’Abbs (1991) the limited outcome data available on the Gordon

Symons Centre suggests that, although the there is evidence of some success,

the residential program appears less effective than a program based on

recreation, community development, and individual and family counselling.

Positive Alternatives Approach

Secondary Education

Most remote rural Aboriginal communities lack secondary education facilities

(Mosey, 1997). Families who want to further educate their children are forced to

send them away from their communities. This is not an attractive option for most

Aboriginal people and hence the level of education is limited.

The report on petrol sniffing in Central Australia (Mosey, 1997) stated that:

“many communities expressed concern at the lack of secondary age

education facilities on their community. They believed that this contributed

to the numbers of young people attracted to the sniffing habit…”

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 21

Indeed, this is an area that needs to be addressed.

Employment

Remote communities suffer from extremely high rates of unemployment (Brady,

1992; Mosey, 1997). Furthermore, unemployment has been found to be

significantly higher among those individuals with a present or past history of

petrol sniffing (Burns et al., 1995). Brady (1992) believes that providing

‘meaningful and productive activity, not necessarily paid work’ for young people

would help reduce petrol sniffing.

An evaluation of strategies to eliminate petrol sniffing in the Maningrida

community investigated the value of employment (Burns et al., 1995). In this

community, a labour pool was formed from community service admissions

referred by the Magistrates court. The more interested individuals were employed

with the help of training funds from ATSIC into the building, mechanical and

landscaping trades. Burns et al. (1995) concluded that employment strategies

were very important in the success of AVGAS this community.

Recreation

The majority of remote Aboriginal communities lack recreational facilities for their

youth. There is widespread belief that the boredom that ensues is significantly

related to the abuse of petrol. Hence, to address petrol sniffing communities have

implemented recreational programs. Importantly, d’Abbs (1991) notes that

recreational programs primarily aim to prevent ‘would-be sniffers and

experimental sniffers’ and are not ‘a substitute for treatment and rehabilitation

programs for chronic sniffers’.

Sport, music and art have been the focus of most initiatives as these activities

are valued by Aboriginal youth (Burns et al., 1995). Prerequisites for successful

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 22

recreation-based interventions were identified in The Senate Select Committee

on Volatile Substance Fumes (Commonwealth of Australia, 1985). These were:

• Staff that understood the problems of petrol sniffing, the needs of the

community and were able to provide interesting, exciting, educational and

purposeful activities.

• Providing after-school activities.

• Including sniffers in activities but not giving preferential treatment.

• Including activities for females and some separate sex programs.

The value of youth development workers has been emphasised by a number of

prominent researchers in the area of petrol sniffing (Brady, 1992). A Youth

development officer has recently been appointed in Jamieson, Western Australia.

This move promises success with 4 youth programs now in progress in

Warakurna, Warburton and Blackstone. As yet, there are no youth development

officers working in South Australia or in the Northern Territory.

Family Influence

The breakdown of family structure is often acknowledged as a major factor in the

abuse of petrol (Brady, 1992). Indeed, the importance of family influence is

evident in the results of the study by Burns et al. (1995) in the Maningrida

community. They found family pressure to be the most significant factor

influencing quitting petrol sniffing.

To address the petrol sniffing problem in Yuendemu, the HALT project focused

on re-including sniffers into their family networks. Parenting roles had been

abandoned under the stress of the problem and attempts were made to reinstate

them (Franks, 1989). Increasing support from the community for the families of

the sniffers was emphasised as they too were experiencing isolation and blame.

The community supported the HALT approach and success followed.

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 23

In accordance with the HALT approach a number of communities support the use

of community counsellors. Community counsellors work to reinforce family

strengths and networks so that they are able to regain control of raising their

children. Individual and family counselling has also been requested by

communities, especially for long-term sniffers (Mosey, 1997).

Other Approaches

Night patrols have been conducted by police and community members in many

remote communities. The patrollers survey the community, seeking out young

sniffers and returning them to their homes. The night patrol in Yuendemu has

received particular attention with a documentary entitled “munga wardingki partu”

(night patrol) being broadcast on the ABC. Although the approach helps ensure

the safety of sniffers and peace in the community it has little long-term

effectiveness.

Another popular strategy is taking sniffers out bush, far away from the community

and thus petrol. The aim is to detoxify the sniffer and give the community a rest.

This approach is ad hoc with the health status and needs of the sniffers being

neglected. Although the use of this approach is widespread, it is fraught with

dangers.

Punishments are often employed by communities in an attempt to deal with the

petrol sniffing problem. Traditional approaches such as public beatings, shaming

and banishment have all been used with limited success (Morice et al., 1981;

Commonwealth Department of Health and Community Services, 1998). Some

communities have also introduced Council by-laws that make it an offence to

inhale petrol or supply petrol for inhalation.

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 24

Volunteer groups have also been used in communities to act against petrol

sniffing. In Western Australia, local communities and the Government of Western

Australia have formed ‘Local Drug Action Groups’. Members of the community

act as volunteers and aim to reduce drug abuse, including petrol sniffing, using a

variety of strategies. These include issuing drug education material, providing

support for families and positive alternatives for youth, monitoring local issues

and trends and working with schools. An evaluation of the effectiveness of these

groups is yet to be undertaken.

A Combination of all approaches according to the needs of the community is

most likely to be effective. All successful projects emphasise the importance of

communities undertaking their preferred treatment approach. Success appears to

be dependent on energy and support from the community (Brady, 1992; Burns et

al., 1995).

Review of Two Specific Community Approaches

Many petrol sniffing programs have been employed in various communities

throughout remote rural Australia. Unfortunately, high staff turnover and the

short-term nature of funding means that the details of most programs are not

readily available. Fortunately two projects, The Health Aboriginal Lifestyle Team

(HALT) and Petrol Link-up, are well documented and will be reviewed here.

These programs received the greatest publicity and funding.

The Healthy Aboriginal Lifestyle Team (HALT)

The HALT project was funded by the Commonwealth Government from 1984-

1990.The HALT work originated in Yuendemu and was later implemented in

Kintore and the Pitjantjatjara Lands.

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 25

The HALT approach was based on the theory that petrol sniffing was

symptomatic of a breakdown in the nurturing authority provided by significant

adults in the sniffers immediate and extended family (Bryce et al., 1994). The

HALT intervention focused on helping Aboriginal adults regain this nurturing

authority and thereby reintegrating the sniffers into the community and reduce

counterproductive peer influence.

According to Franks (1989), the HALT approach to petrol sniffing in each of the

communities can be summarised into four broad steps:

1. Talks with the President and Council.

HALT met with the President and Council of the community for a number of

reasons. Firstly, the whole community needed to be aware of the project and this

was the most appropriate means of achieving this. Secondly, HALT wanted to

emphasise the importance of the relationship between themselves and the

community. And finally, they wanted to discuss how strategies undertaken by

community members would integrate with those of the Team.

2. Community Support Agreements.

Community Support Agreements were formulated at the Council meeting and set

out the specific measures that were to be implemented by the community to

combat petrol sniffing. These varied between communities but included such

things as introducing night patrols, assisting with needs of taking a child to an

outsation, and selecting local adults to act as Community Workers with the

Team.

3. Counselling.

Individual and Family counselling were included in the HALT approach. Two

types of Individual Counselling were utilised. Simple Support Counselling was

used in situations where the family was still providing support and understanding.

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 26

In-depth Counselling was employed for those families whose functioning had

become distorted and powerless.

4. Appropriate Communication

Where possible, HALT used culturally appropriate forms of communication to

promote petrol sniffing issues. These included using indigenous symbolism in

paintings, diagrams and video production.

A number of evaluations of the HALT approach have been undertaken. There is

general agreement that HALT successfully helped the Yuendemu community to

eliminate petrol sniffing, however, HALT evidenced less success in Kintore and

had no significant impact on the Pitjantjatjara Lands (Bryce et al., 1991; Bryce et

al., 1992).

Major criticisms of HALT outline in the literature include a lack of specific goals

and outcome criteria, and an apparent inability for others, except the Team, to

replicate the approach (Bryce, 1992; Hempel & Patterson, 1986; Smith &

McCulloch, 1986). Importantly, the contributions of HALT to petrol sniffing

interventions have also been recognised (d’Abbs, 1991). Indeed, the importance

of reintegrating sniffers into their families and communities, the significance of

kinship networks, and the value of family and individual counselling and

community involvement are now generally recognised.

The variation in success at Yuendemu, Kintore and the Pitjantjatjara Lands

indicates that there is no single solution to suit every community. Communities

need to be supplied with information on a range of approaches so they can

choose a strategy most appropriate to their needs. Indeed, it is support for a

chosen approach that is one of the most influential factors in success.

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 27

The Petrol Link-Up

The Petrol Link-up project was funded by the Commonwealth from 1993-1994.

The project supported community initiatives in the tri-state region of the Northern

Territory, South Australia and Western Australia. The project aimed to act as a

service provider to communities by collecting and supplying information about

existing programs and research. The major contributions of the project are

outlined here.

Information gathered was disseminated by way of newsletter. The newsletter

approach proved to be a powerful communication tool between the Petrol Link-up

team and the communities. The requests from communities for further

information resulted in a field trip routine, whereby Petrol Link-up team visited

communities and continued the information process. A resource list was

developed which included all current relevant information sources.

One of the major successes of the project was the development of the “Brain

Story”. This series of laminated posters depicting the brain damage caused by

petrol sniffing was used on visits to the communities.

The Petrol Link-up team recognised the value of outstations from their field trips

to communities. Through meetings and workshops they endeavoured to help

communities apply for funding for outstations programs. After visits to numerous

outstations they developed a document entitled “The Missing Link”. The

document had been intended to be a resource which set out the all the options

and arguments for the funding of outstation programs. Unfortunately, the

document was left at first draft, nevertheless, is suggested as a good basis for a

manual for outstation programs.

The Petrol Link-up team also focussed a lot of energy on the AVGAS strategy.

They gathered and distributed information about the approach to anyone who

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 28

was interested or concerned. In addition, they monitored the progress of the

strategy in communities where it had been introduced. Following Petrol Link-up

involvement a number of communities successfully introduced AVGAS as a

strategy to reduce petrol sniffing.

The project hoped to stimulate a “three way” approach to petrol sniffing. The

“three way” approach involved:

• reducing the availability of petrol through the substitution of AVGAS

• rehabilitating damaged sniffers through outstations

• providing positive alternatives through youth programs

On conclusion of the project a number of communities were implementing this

approach.

The Petrol Link-up project was successful in its meeting its aims and objectives.

The major successes of the project included assisting the introduction of AVGAS

to communities, the gathering and dissemination of information about petrol

sniffing related issues, and the development of petrol sniffing resources.

Overseas Approaches to Solvent Abuse Treatment

A British Approach

Richard Ives is the leading expert in solvent abuse in the UK. He has developed

a manual for treatment that includes the most successful approaches

implemented in that country. The treatment approaches outlined in the manual

may be useful for urban Aboriginal solvent abusers but are unlikely to be

effective for Aboriginal youth from remote communities.

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 29

A Canadian Approach

Canadian indigenous people suffer similar substance abuse problems as

Aboriginal Australians. The use of solvents has grown to epidemic proportions in

many First Nation and Inuit communities. Fortunately, the Canadian government

has recognised the extent of the problem and has allocated 17.5 million dollars to

solvent abuse prevention and treatment. With this funding 8 solvents abuse

treatment facilities, designed specifically meet the needs of the indigenous youth,

have been established across Canada. These treatment facilities appear highly

successful and are a good reference for future directions in treatment for

Aboriginal Australians.

The Whiskyjack Treatment Centre Inc. is one of the Canadian facilities. Like the

other 7 solvent abuse treatment centres, it is based on a multi-discipline

residential treatment approach with particular attention to First Nation cultural

beliefs, traditions, values and customs. The centre serves both male and female

solvent abusers aged from 8 to 17 years. Treatment generally lasts 6 months

however this varies between individuals.

Treatment includes programs which focus on developing mental and emotional

wellbeing as well as physical, social and recreational skills, and spiritual growth..

Education plays an important role in treatment with each client being given

individualised education program. Moreover, clients are provided with information

on solvent abuse and addictions and are encouraged to enhance their command

of their native language. Western healing is utilised in the form of Psychiatric

Nurses, Psychologists and Counsellors, however, native healing is also

encouraged. The family of the client is encouraged to participate in as many

aspects of treatment as possible as this increases awareness and functioning

among family members. A community outreach program is also provided by the

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 30

centre. It aims to increase community awareness of solvent abuse and promote

maintenance and prevent relapse in ex-solvent abusers.

The residential focus of this approach to solvent abuse treatment is unlikely to be

popular in Australian remote rural Aboriginal communities. However, the

programs used in treatment may provide a good source of ideas for petrol

sniffing communities, in that, the importance of culture and tradition is

emphasised.

A South-East Asian Approach

In South East Asia a camp approach to drug detoxification has arisen. Although

these camps are not specific to solvent abuse the approach is relevant and

transferable.

The camps vary in structure and target group yet most involve the following

steps, as outlined by Sell (1994):

♦ Identification of all the drug dependent users living in the community.

♦ Initiate a process of rehabilitation before detoxification through empowerment.

That is, spread optimism, de-dramatise withdrawal, de-mystify drugs, and de-

professionalise detoxification.

♦ Form a parents’ group for self-help and support by bringing together the

parents, and/or relatives and friends of the drug user.

♦ Enlist the help of ex-users and other volunteers to plan the detoxification

camps and later provide support for the users.

♦ Locate an appropriate facility to accommodate the users, significant others

and workers for the group detoxification which usually lasts 10-14 days.

Although a school or community centre is most appropriate some camps have

been successfully run in tents.

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 31

♦ Usually by the time the detoxification camp is to take place most of the users

have been motivated to participate. Those who refuse are expelled from the

community as are known drug suppliers.

♦ Following the detoxification camp, there is continued involvement of staff with

clients in varying degrees for a number of months. This involvement is aimed

at promoting maintenance and preventing relapse.

Variations of this ‘camp’ approach to drug and alcohol detoxification are found

throughout the Indian subcontinent. These include opium detoxification camps in

Rajasthan in Northwest India, alcohol treatment camps in Madras in South India

and the ad-hoc heroin detoxification camps in the regions of Colombo, Kandy

and Galle, Sri Lanka. All have shown surprisingly high rates of success when

compared to popular Western approaches (Kaplan et al., 1993). Indeed, in the

search for a successful strategy against petrol sniffing the ‘camp’ approach has

much to offer.

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 32

References

Berry, M., Garrard, J. & Greene, D. (1993). Reducing lead exposure in Australia:A consultation resource. RMIT, 9-47.

Brady, M. (1989). Drug set and setting: the Aboriginal context. Australian Instituteof Aboriginal Studies: Canberra.

Brady, M. (1992). Heavy Metal: The social meaning of petrol sniffing in Australia.Aboriginal Studies Press: Canberra.

Brady, M.(1995). Culture in treatment, culture as treatment. A critical appraisal ofdevelopments in addiction programs for indigenous North Americans andAustralians. Journal of Social Science and Medicine, 41, 1487-98.

Brady, M. & Torzillo, P. (1994). Petrol Sniffing down the track. The MedicalJournal of Australia, 160, 176-177.

Bryce, S., Rowse, T. & Scrimgeour, D. (1991). HALT: and evaluation. MenziesSchool of Health Research and the Aboriginal Torres Strait Islander Commission:Darwin.

Bryce, S., Rowse, T. & Scrimgeour, D. (1992). Evaluating the petrol-sniffingprevention programs of the Health Aboriginal Life Team (HALT). AustralianJournal of Public Health, 16(4), 387-396.

Burns, C.B., Currie, B.J., Clough, A.B & Wuridjal, R. (1995). Evaluation ofstrategies used by a remote Aboriginal community to eliminate petrol sniffing.The Medical Journal of Australia, 163, 82-86.

Burns, C. & Currie, B. (1995). The efficacy of chelation therapy and factorsinfluencing mortality in lead intoxicated petrol sniffers. Australian and NewZealand Journal of Medicine, 25, 197-203.

Burns, C.B., D’Abbs, P. & Currie, B.J. (1995). Patterns of petrol sniffing and otherdrug use in young men from as Aboriginal community in Arnhem Land, NorthernTerritory. Drug and Alcohol Review, 14, 159-169.

Burns, C. (1996). An End of Petrol Sniffing. Ph D thesis, Sydney University.

Burns, C.B., Currie, B.J. & Powers, J.R. (1996). An evaluation of unleaded petrolas a harm-reduction strategy for petrol sniffers in an Aboriginal community.Journal of Toxicology and Clinical Toxicology, 34, 27-36

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 33

Central Australian Rural Practitioners Association. (1997). CARPA StandardTreatment Manual. 3rd Edition. Central Australian Rural Practitioners Association:Alice Springs.

Chalmers, E.M. (1991). Volatile substance abuse. The Medical Journal ofAustralia, 154, 269-274.

Commonwealth of Australia. (1985).Volatile Substance Abuse in Australia.Senate Select Committee on Volatile Substance Fumes. AGPS: Canberra.

Commonwealth of Australia.(1987). Return to Country: The AboriginalHomelands movement in Australia. House of Representatives StandingCommittee on Aboriginal Affairs AGPS: Canberra.

Commonwealth of Australia. (1991). Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths inCustody National Report. AGPS: Canberra.

Currie, B., Burrow, J., Howard, D., McEiver, M. & Burns. (1994). Petrol Sniffer’sEncephalopathy. In Brady & Torzillo (eds) Workshop on lead and hydrocarbontoxicity from chronic petrol inhalation. The Drug Offensive. AGPS: Canberra.

D’Abbs. (1991). The Prevention of Petrol Sniffing in Aboriginal Communities – AReview of Interventions. Drug and Alcohol Bureau: Department of Health andCommunity Services: NT

Divakaran-Brown, C. & Minutjukur, A. (1993). Children of Dispossession: Anevaluation of petrol sniffing on Anangu Pitjantjatjara Lands. Department of StateAboriginal Affairs: Adelaide.

Donald, W. (Coroner). (1988). Coroners Act: Summary of Findings 9420219 Rel.case A82/94: NT

Eastwell, H.D. (1979). Petrol inhalation in Aboriginal towns. Its remedy: thehomelands movement. Medical Journal of Australia, 2, 221-224.

Franks, C. (1989). Preventing Petrol sniffing in Aboriginal communities.Community Health Studies, 13, 14-22.

Garrow, A. (1997). Time to stop reinventing the wheel: petrol sniffing in the TopEnd. Project Final Report. Alcohol and Other Drugs Services, Territory HealthServices. Unpublished.

Gray, D., Brooke, M., Ryan, K. & Williams, S. (1997). The use of tobacco, alcoholand other drugs by young Aboriginal people in Albany, Western Australia.Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 21(1), 71-76.

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 34

Goodheart, R.S. & Dunne, J.W. (1994). Petrol Sniffers encephalopathy: a studyof 25 patients. The Medical Journal of Australia, 160, 178-181.

Gracey, M. (1998). Substance misuse in Aboriginal Australians. AddictionBiology, 3, 29-46.

Hayward, L & Kickett, M. (1988). Petrol sniffing in Western Australia: An analysisof morbidity and mortality in 1981-86 and the prevalence of petrol sniffing inAboriginal children in the Western Desert region in 1987. Health Department ofWestern Australia: Perth.

Hempel, R & Patterson, B. (1986). Alice Springs Petrol Sniffing Prevention Team:evaluation report. Department of Aboriginal Affairs and Department ofCommunity Development: NT.

Ives, R. (1994). Stopping sniffing in the States: approaches to solvent misuseprevention in the USA. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 1(1), 37-48.

Ives, R. (1996). Drug use among Western Australians (part II). Journal ofSubstance Misuse, 1, 226-229.

Kaplan, C., Morival, M. & Bieleman. (1993). The Camp Approach to DrugDetoxification.

Kooyman, M. (1992). The therapeutic community for addicts: Intimacy, ParentInvolvement and Treatment Outcome. Erasmus University Press: Rotterdam.

MacGregor, M. (1997). Synopsis of Inhalant Solvent Abuse from a CentralAustralian Perspective. Central Australian Alcohol and Other Drugs Program,Territory Health Services.

Mann, K.V., & Travers, J.D. (1991). Succimer, an oral lead chelator. ClinicalPharmacy, 10, 914-922.

Maruff, P., Burns, C.B., Tyler, P., Currie, B.J. & Currie, J. (1998). Neurologicaland cognitive abnormalities associated with chronic sniffing. Brain, 121(10),1903-1917.

Morice, R.D., Swift, H. & Brady, M. (1981). Petrol sniffing among AboriginalAustralians: A resource manual. Alcohol and Drug Foundation, Canberra.

Morrow, L.A., Robin, N. Hodgson, M.J. & Kamis, H. (1992). Assessment ofattention and memory efficiency in persons with solvent neurotoxicity.Neuropsychologica, 30, 911-922.

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 35

Mosey, A. (1997). Report on petrol sniffing in Central Australia. Cental AustralianAlcohol and Other Drug Services, Territory Health Service. Unpublished.

Mundy, J. (1995). Out of the Spotlight. Connexions, 15(4), 269-274.

National Drug Abuse Information Centre. (1989). Update on deaths caused byvolatile substances, 1980 to 1988. Commonwealth Department of CommunityServices and Health, Canberra.

Perkins, J.J., Sanson-Fisher, R.W., Blunden, S. Lunnay, D., Redman, S. &Hensley, M.J. (1994). The prevalence of drug use in urban Aboriginalcommunities. Addiction, 89, 1319-31.

Roper, S. & Shaw, G. (1996). Moving On: a report on petrol sniffing and theintroduction of AVGAS on the Anangu Pitjantjatjara lands. Nganampa HealthService, Department of Human Services and Health.

Sandover, R., Houghton, S. & O’Donoghue, T. (1997). Harm minimisationstrategies used by incarcerated Aboriginal volatile substance users’. AddictionResearch, 5(2), 113-136.

Sell, H. (1994). The community approach to drug abuse control. Paper presentedat the European Consultation on the Open Community Approach toTreatment/Care & Prevention of Drug Abuse. London 1-5 June.

Shaw, G., Armstrong, W. & San Roque, C. (1994). Petrol Link-up final report.Commonwealth Department of Human Services and Health: Canberra.

Smith, A & McCulloch, L.. (1986). Petrol sniffing: report on a visit to Alice Springsto see the work of the Northern Territory Petrol Sniffing Prevention Team.Department of Community Services (WA).

Valpey, R., Sumi, S.M., Corass, M.K. & Goble, G.J. (1978). Acute and chronicprogressive encephalopathy due to gasoline sniffing. Neurology, 28, 507-510.

Young, T.J. (1987). Inhalant use among American Indian Youth. Child Psychiatryand Human Development, 18(1), 36-46.

Zebrowski, P. & Gregory, R. (1996). Inhalant use patterns among Eskimo schoolchildren in Western Alaska. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 15(3), 67-75.

Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council (SA) Inc. 36

ALICE SPRINGS HOSPITAL PROTOCOL FOR THE MANAGEMENT OFPETROL SNIFFING PATIENTS

(as cited in Brady, 1992)

• Intravenous fluids to maintain hydration

• SedationParaldehyde

• Anti-epileptic medicationPhenytoin

• Chelation TherapyDimercaprol (BAL) 24 milligrams per kilogram of body weight per dayIntramuscularly in six doses for five days.

EDTA 50 milligrams per kilogram of body weight per dayIntramuscularly in six doses for five days.

• NutritionNasogastric feeding or parenteral nutrition, ie. feeding through the nose,by injection of intravenously.