Le Corbusier - Strasbourg_Eisenman.pdf

-

Upload

nancy-al-assaf -

Category

Documents

-

view

68 -

download

2

description

Transcript of Le Corbusier - Strasbourg_Eisenman.pdf

•

1. rtJllsie1; ,Hodel of the Palais des CUllgres-Stral>/)01wg, Fm?tcp, 19GJ-v.,.

3. Textual Heresies Le Corbusier. Palais des Congres-Strasbourg, 1962-64

One of Le COl'busier's earliest drawings of the Parthenon is a key to the evolution of his architecture during a period spanning the two world wars and leading to a critical inflection point with his project for the Palais des Congres in Strasbourg. The drawing, probably done at the tune of his Voyage d'Orient, shows the Parthenon in the left foreground, its columns and base providing a Cartesian fratnework for the drawing. But on the right, in what seems to be an impossible view given the Parthenon's distance from the sea, is the harbor of Athens with its shoreline and surrounding mountains. This drawing is an early manifestation of what was to become an evolving obsession: the dialectical and tensioned interplay of the figure with the Cartesian grid, which appears in his earliest Purist paintings and continues throughout his career, evolving from a two-dimensional figures to three-dimensional figures.

While the concept ofgridded Cartesian space is readily understandable in the work ofLe Corbusier, the concept of the figural as different from any free-form shape emerges in the context of post-structuralism. This idea is based on Gilles Deleuze's discussion of the paintings of Francis Bacon. In his 1981 book, Francis Bacon: Logique de la Sensation, Deleuze distinguishes figuration from the figural. Figuration refers to a form related to the object that it is meant to represent. Rather than defining a form, the figural is that which is produced as a register of forces. Here,!o'1'ces is the operative term. In the case of Bacon's portraits, the figure is distorted by internal pressures while the paint of the canvas-scrubbed, smearedaddresses these forces in the very materiality of the painting. The figural no longer expresses an iconic form or figure, but rather dOCUlnents the encounter of matter-paint, canvas, painter, and sitter-and forces-both

/4

physical and psychological. As a regi>itcr of' such force~, the human figur~ no longer presents it~elf'

as a discrete, clear I'm'm, but rather re~ides in what can be called an wldecidable relationship with the canvas; the outline of the whole figur is blurred to become an assembly of partial figures that neither cohere, nor strive to create a clistinct and understandable form. This shift from whole to what are being called partial figures,which themselves m'e a physicall'esidue of' forces acting on whole figures, cOlTesponds to a shift in Le Corbusier's architecture from his prewar interest in a dialectical interplay between figure and gJ.id to, late in his career, an internally generated critique that severs the prior dialectic. Instead, a serie~ of figural conditions are produced which have the quality of partial figures, In his postwar work, I.e Corbusier also challenges the precepts of his "Fi\e Points," in which free plan, pilotis,fenelre en longueur, free

Palai~ cle~ C'ollgr(,:!'

facade, and rooftop terrace were characLeJ'istic of his prewar work.

It could be argued thai Le Corbusier's earl architecture repre~ent~ an attempt to transcend the limits ofpainting, which he theorized in his book Afte)· f'ubism, Wl'iUen with Amedee Ozcnfant. If cubist painting was marked by a ten1'ion between the frontal pictw'e plane and spatial depth, Le

orbusier's architecture strained to both inCOl})O

rate and overcome the tenets of frontal and flattened cubist space in a three-dimensional matrix. This integration of a three-dlrnensional, figured quaHty began early in his career with his Pmist period paintings and his 1914 Dom-ino diagTam. In the Dom-ino diagram, Le COl'busier introduce the Cmtesian gl'id as a structural system that could produce an infinite horizontal extension 0

space. This diagJ.'am conceptualizes veli-ical circulation as a legible figure or what can be considered a figured element, which is pulled out of the stacked horizontal slabs. The Dom-ino diagram 31ticulates Le Corbusier's concern with integrating a tlu'ee-dimensional figured element into a necessarily reticulated condition of architecture.

Le Corbusier's Dom-ino diagl-am prefigured the "Five Points" articulated in his 1923 book Vel's

tine Al'clzitectu1'e. In the Dom-ino diagram, the columns are set back from the facade to create a free plan and a free facade: the fiat roof becomes the pl"ivate space, and the floor slab 1::; lifted off the ground to produce a horizontal continuum f Rpace. The primitive foundation blocks in the

place of pilatis initiate a critique of architectme's relationship to the ground: figure in architecture had always been tied to the ground, so much RO

that it was defined as a figurc/gl'ound relationship. The idea of' the pilotis originally displace::; architecture, lifting the building off the gJ.'olmd literally and conceptually to initiate a more complex dynamic of figure and ground,

I.e Corbusier's early canonical buildingsVilla Savoye U) Poissy and Villa Stein at Garches-

Palais des congl'cs

3. p(llais des Congres-Stmsbonm, model, 1962.

develop the diagl'am offered in his "Five Points," and introduce a more strongly figw'ed condition in the circulation, The early sketches for Villa Savoye document the mo\'ement in Rection generated by the ramp, which takes up the movement of the car as it enters underneath the building and then engages the subject in a spiraling up through the building to the roof garden. The ramp as a figured element creates and registers a kind of vortex of centrifugal energy. This entrifugal motion in the Cartesian space of the

building generates an energy from the center to the periphery, Similarly exemplifying the "Five Points," the Villa Stein emphasizes both figured elements and the gJ.idded envelope of the villa's stlucture, which retains a cubist or layered flatness resembling a vertically stacked deck of cards. The facade at Garches presents the collapse of the space of the plan into the vCltical plane of the facade, which becomes an index of the collapse of

If)

real space into a single moment in space and time. Tins collapse of pcrspective also becomes a criique of monocular perspecti\'al vision. The mol'

strongly figured elements ofGarches are the CUl'\'

ing free-form walls and the promenade al'chitec

tumle, which is inserted into the l'eal' facade as ' staircase, Figw'ed form also appears in two staircases and in the cutout of the balcony and eating area, yet these figures remain more lU1ear Ulan volumetric. In these early works, the figured clements are implicated in a dialectical relationship to the absb'act grid of Lhe buildings' plan, facades, and sectioll.

The relation ofgl'id to figure in Le ('orhusier's postwar work changes dramatically from the gJ.·id-dominant systems of his prewar building5. The figured element becomes increasingly \'olumetlic, indicating a shift in his attitudes toward both abstraction and the ligure. In Runchamp, the Philips Pavilion, and Chan<1igal'h, fully Lhl'ee

iii Palais des Congrb Patak de;; Congres /,

I<

4. Vill(l SIII'()ye, PO;R'~l!, 1928.

dimensional fig1.U·e~ stand out against the grid, yet the grid remains legible. 1"'01' example, while the figure seems to dominaLe in the sculptured forms of Ronchamp. the grid is present in the floor patterning, which is part of Le COl'busier's modular system of proportiomi, and a virtual 01' impliecl gl'id is legible from the building's f"outh elevation.

he square punctures in the facade register a tension between an implied veltical grid and the sloping wall, as if the holes were tethers maintaining the e:\.'terior wall's curve. The tension in the curve comes from the implication that if these connections were cut, the wall \"ould snap back into a flat vertical plane. The notation of these openings in the thickened figured wall plane indicates that the curved wall is not a gratuitous curve, but rather refiects an internal t.ension between th figured surface and a virtual. griddecl plane.

If the prewar work demonstrate~ the linear igw'ebecomingincreasingly three-dimensional, it • could be argued that Le COl'busier's postwar work begins with the fully articulated ftgw'e, which is increasingly deformed into a series of partial fi~ores. In his Parliament Building at Chandigal'h. a giant cylindrical element breaks through the roof, becoming a dominant featw'e of the roofscape as a fully three-dimensional figure. Yet this figure is hidden behind the orthogonal blocks that form

5. Not,'e Dame d'U Haul, Ronchamp, 1950.

each of Ule parliament's facades. Chandigarh also marks an important departure from the planar, free facade of Le COl'busier's "Five Points": Chandigarh's deep tn-i.se-soleill'eplace thefenetre en longueunvith a honeycombed mass; this motif is repeated in Harvard's Carpenter Center, La Tom'ette, and Strasbourg.

La Tourette can also be related to Strasbourg by means of a rotational energy established by the pinwheeling organization of its lower floors. A geometrical figme is established in the form f a blunted, three-sided pinwheel. Another kind

of rotation animates the facade of La Tom'ette, according to Colin Rowe's analysis, yet this rotational energy retains the tension provided in the fi'ontal plane. In the Carpenter Center this rOl.a

tional energy becomes increasingly explicit: the paired lobed forms of its studios and exhibition spaces seem to revolve around a central core, which anchors its large S-shaped main ramp. Despite the contradktory internal movements at the Carpenter Center-its lobes spin counterclockwise and the internal ramp rotates clock:wi~e

up to the third floor-it could be argued that each component is mticulated as a separate figure: the S-shaped main ramp, the lobed studio and exhibition spaces, and central square fo}'m are COlD

pressed together, yet they remain identifiable as

6. As,~embly Hall, Clw.lIdignrh.195.j-6b

complete and separate parts. Similarly, a number of the precepts of Le COl'busier's "Five Points" remain apparent with elongated pilotis, the free plan, rooftop terraces, and briBe-sole-il occupying the horizontal openings formerly allocated to the fenetre en longu.euf.

The centrality of the ''Five Points" in Le COl'busier's prewar work suggests that the points served as a foundational diagram from which each building draws, but inflects differently. This indicates the capacity of the ''Five Points" to serve as a text for his early buildings, in the sense that a diagram is an architectural form of a text. If the idea of a text is established in Le Corbusier's ''Five Points," it is his inversion of the "Five Points" and his turn away from the legible figure toward partial figures that suggest that Strasbourg can be read as heretical to his prior architectlU'al t.exts. There are a mm1ber of didactic deviations from the "Five Points" in Le Corbusier's postwar work; the bl'iBe-soleil replacing the free facade is only one example. Yet Le COl'busier's Palai~ de~ Congr€s-StrasbouTg becomes the summation of an evolution in a textual language, on the one hand in its didactic refutation of each of the "Five Points," and on the other in its movement away from a dialectical relationship between figure and grid. If the

7. PaLais des Cougl'es-Strltsbolll'g, l>'1te plan, 196w.

text of the figure/grid relationship is scripted in Le Uorbusier's prewar work, the postwar work deYelops the idea of the figure, from a whole and discrete element into one whose vel-Y wholeness is questioned. 'The figure becomes deformed into a series of partial figw·es. As an heretical te};.i;, the Palalli des Congl'es engages both a dialectical system refuting the "Five Points" and a nondialectical system pursuing the evolution of the figure from a discrete tltree-dimensional entity to a dispersed series of figural elements whose contours become increasingly undecidable.

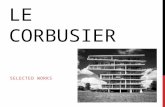

With the Palais cles Cong1'€s, a project beg-un in 1962, only a year after the Carpenter Center, many of the relationships established in La Tourette and the Carpenter Center are inverted. First, the relationship of building to gl'ound is profoundly different at Strasbow'g. No longer d pilotis preserve the horizontal flow of the ground below the building. Instead, the gl'o1.lJ1d plane becomes a honeycombed plinthlike ba.."e. whose very solidity is fmther questioned as the gr01.111 is cut away in such a mam1er to suggest that the base is floating. The sloping ground around Strasbourg's base creates a double reading of both plinth and pilotis. Similarly, the precepts of free plan and free facade are inverted. Just as the brise-soleil counters the planar facade with depth,

--

71' Palms des Congl'e" ~a]ab des Congrb T!l

H. Jlct/ais de.~ Crmf/res-SII'Us/)o//I'O, spr-l;rllLllO,.t/t-scmth. 196f2.

shadow, and thidmesi', so lOU doe!'\ the free plan become 8uh~umed by a geometrical figure resembling the pinwheel ol'ganization of La Tourette in Strasbomg's ground level. Finally, the horizontal surface of the roofgarden becomes a figural plane, which is tipped, l wi~ted, and torqued.

If circulat ion had previously registered both a ccntlifl.lgal fOl'ce and a distinct figural element in Le Corbusier's ecu'lier work, the ramp at Strasbourg registers both centripetal and centrifugal force" ~imtl1laneously, as well as a critique of the legible whole figurE', Tbe figure of the ramp is the most significant index for the development of the 8tl'asbom'g scheme. A study of the carliest St.l'asboul'g schemes of 1962 reveals that the l'amp was initiall~' envisioned as a distinct figure forming an unbroken loop through the building. The first, 19G2 scheme is an articulated gquare in plan with a giant straight ramp entering the square form from the ~outheast corner and a pair of'

• lobed ramps protruding frOll! the 11001:h and souU, sides of the l'quare in an echo of the Carpentel' 'enter. The giant ramp leadf: up to the :;econtl

floor, where it divides to form paired ramps on the north side, which reach up around the third floor and lead onto the rooI. The ramp forms a complete entity around the building, and in the l'iecond-floor plan is highlighled as an independent figure, a'i is the pinwheel figure of the floor below. In a sub

sequent plan, the giant ramp is rotated ninety degrees and positioned to align axially with the giant lobed ramp on the north sidc, replacing the small southern lobed ramp of the initial plan. In this second scheme, reproduced in Le COl'busier's Oem.tres Compfete, the bi-lobed organization of the Carpenter Center has been edited, signaling Le Corbusier's departm'e from whole figures and movement toward the paltial figure. This becomes apparent in the final scheme of the Palais des Cong1'es, where the yelJ' figure of the ramp seems to shift its weight to the west in counterpoint to the dominant axiality of the giant ramp extending south. More significantly, the ramp's figm'E' i:=; no longer whole; the figure of the ramp seems to split in several places, no longer looping through the building but rather spiraling around the stmctw'e. The ramp can be conceived of as a series of partial figures which no longer cohere like the independent ramp of the eaJ'ly scheme. Thus, Strasbourg's final scheme is animated by a 'ondition of complex partial figures.

The figw'e assumes a different role at Stl'asbourg in tJ1ut it is no longer defmed in relabon"hip to the grid. Strasboul'g is signif1callt in Le COl'busier's oeuvre as a depmture from the grid/figure dialectic. This depalture appears in two different conditions: as a partial figure and as an undecidable condition of the ramo: is it

~._-.-

~ --'=- :;. -..----=--=..=--;.::. /

~~

.,. Palrt;5; del'- Congl'es-Stralibourg, uieu' ofealil eleuutiol/. 1962.

I

centripetal or centrifu~al? While the figural is often seen as a system of movement-and this is no less truE' in Strasbourg-the project invokes both centrifugal and centripetal forces, which first move outward through the Cartesian enclosure of the building and then tm'n back, spil'aling inward. The subject becomes involved not only in the figural ramp but also in the breaching of the container, the pJ'ism pOx of Cartesian space that was articulated in the "Foul' Compositions" by Le

orbusier. Unlike the rotation on the entry facade of La Tourette, which, in Rowe's analysis, retains the tension of a frontal plane, the rotation develped at Strasbourg is no longer dialectical with

respect to any frontal plane, but rather register!'! simultaneously as centl'ipetal and centrifugal in plan and section.

In thi~ respect, Le COl'busier's project for Strasbourg marks an important movement near the end of his postwar career. Stl'asbourg is also an anomaly in t.his book, for it is not a hinge building within the particular career of an architect but rather a hinge between Le COl'busier and the architects that draw on his legacy. In exploring the figural at Strasbourg, Le Corbusier blurs the large figures of the ramp by dispersing them as paltial figures at the upper :floors. Similarly, the didactic natlU'e of the "Five Points" and the didactic development of the figme against a CaItesian

g1id become increasingly blurred as Le COl'busiel' explores the potential of these pmtial figtu'es at Strasbotll'g.

This building offers a missing link bet.ween the formal strategies of the high modernist "Five Points" and those apparent in Rem Koolhaas's n'es Grande Bibl:iotheque and Jussieu Libraries. StrasbolU'g is the forerunner of both Koolhaas projects, in that the object is no longer merely contained in t.he volumetric endosure but rather a sel;es of forces push the object out through the exterior cnclosm'e of the object, while the movement of the subject continues to circumscribe the volume. The discontinuity between successivc hOl;zontal plan levels at Strasbourg will ultimately appeal' in Koolhaas's Delirious New Yo,.k and his French library projects. Lastly, Strasbourg shifts the idea of understanding from seeing to the expelience of movement.

The Palais des Congres-Strasbourg establishes an internal clitique of what could be onsidered the prewar "texts" embodied in Le

COl'busier's "Five Points," Finally, in the evol\Ting changes in the acts of close reading, legacies of the formal and the conceptual remain. ·What becomes visible ill the Strasbourg project as a pivotal development of Le Corbusier's thought is the new figural condition of the subject's experience of the object. This Vlrilliead for example to a

"'1

r

I I~

. IdJ~:~,~</:=:->-'I~ ~

/~---;:'r ~ -----I ''<, .........

I l__" ,tT

lJ. Palo is de::; COl/rrres. 7)[all leoe! .J.

11. Palai.~ de.~ C01lgl'eS, plall level.).

CJ

=:;:; ;::::;• .:=:; :=: :::.s;s==:=;=.::::=;= ~==--.

es COl1gl'e.~, plan l('1'el 4.

~--:--

-,--.---/' - /1-/"- -'"'-"",

; ~- .... ,

/-. "

== :::::;. -~.~~ ~ ~=== '~ ====="

,,"'.t

n

12. Pal

10. Pa.lais des C'ongres, plan level 2.

Palai" rle>' Congl'e~Pa]ai~ def' Conl!"l'es ~(j

different necessity of close reading in Koolhaas's Jussieu Libraries, Strasbourg, unlike La Tourette and Chandig-arh, pl'Oposed an entire other series of pl'oblematics not addressed in either phase of Le COl'busier's previous work. In these inversions of many Corbusian tropes begin an internal critique that marks this particular work as different when compared to the prior buildings of Le Gorbw:;ier's architectlll'e.

~..... '"

16. The brise-soleil anpeaJ'S a.~ ,tJOid8 cut fro ill (I solid.1." Pala1:s des Congres, first-floor levels. The fenetre en longueur oj'Le CO/'busier's "Fl:ue P()int.~" becomes a lwlleycombed briRe-soleil. a ,,'gular sy.~teJl1, oj' openings thal1l'raps aronnd three I<ides of the Palais des Congl·as.

Palai!' de:; Congre:;

/ f I .

d.

f·"

,~

Palai~ ~,.; COllgJ'eS

/"""/ /1", ''''

///""~'" / ~ "

~,~ /)/b"',(:/

<l~"# ",~, \::. -~

"\

'a/ais deN COt/gres can be read as a doable sOl/dwic'/i containing two piloti !cwe/s stacked one on top of the otllel: The gvol/lld wn no lOJ/ger be identified as S1lCh, ,,"or Ille luwer pi/ntis levellla.~ been !J1t.<:hed dO({'rl $0 that f/ie second lel'eZ (~fpitotif; is at gromullcoel.

a.

r.

(~ .

/

// /

////

//

/ '-'V/

,

>/ """JJ~/.... .

/

"

/'"~ \

/1"'"/ / ~'/ / "

// "'\/ / 1-/~~ ;/" ~. ."' ~~

" - ----- ----- -

/"""// / /" ,

// // ',." // /// "', "

//// " '" //(// "" ..: ' "" ' ," .... ' "" '!Ii. f ....

, .§k

'"

~~ '--

14 ((lj). Palais des COrLr!rcs, groltlld- (lI/(I,find-jloor' I'p/s. The fo'stfloGI' level (a) is depl'e.~sed into the

,ground (b), doubled (c), voilied (d), and ro IIIfJrd 1/[i to tlie new uraund level (e), which br'comes the bwse for the pilotis (0, The 1'e/)el'8(11 of Le Co,.b?(,~iel-:~ "Fllie

?illt.~" at Strasbourg begins with tile piloti,,:, 7'Ii

•

-)

".pil

'"

O. The double-height uoid,~ in IIleloll rill Qlldfifthfloors lSe,·1.Ie ClS a rotatiol/al a.l'isfo/ the pi1PLlleel, who.~e ((miS

w'e tile hlocksflll'111ed by the main lwditol"iu1II spaces.

19. Palai:; dp.~ r'v1/gres.j(mnll fiool: The fO/lrl1l floor is I()o.~ely organized illto blockl>, ("IWltillg two 1l,.,I/S of fl pin 1/111 eel which mtctte a,'omlcl a eel/tel' void.

Palais des Congres

"'\',

" ".

~

Palais des COlIgr~S

18. 011 the :;econd floor, this pinwheeling motion is n>,peated on Qnothel', snwllel' scale: a clusler I!( moms rotates witl/hl each quadrant, creating a ,~ecollda,.y

spillllin{J inlerllal to coth of tile. (11((Jdl'(mt,~.

':'" - ~,!I'N.~/

"", 1./

/ /'

,

17. Palai~ des Co1I{JI'iJ.s, second jioo/: Till' plllll of tile ,~ecI)l/d.ffo()r can be divided into/OIlr Quadrants, wltieh. because of the ramp that goes up to the piano nobile and the mmp that enter.~ into tills lowrr lel'el, ol'e organized ax pillwlleelillgfo.,.m.~.

lH

,~

•

'v

~(l alai.8 des CongJ'es

~

j'

I

/ /

!l. Pnlais des Crmgr'f1S, ,~er;olld flool: The a nulysi8 of U, These absences describe spa.ces that pUlIctuJ1te this the second}ioor colnmn ,grid begil/s to ','aeal tliat at ullerall !friel, Por I<xample, the void 'ill the seCfmd~floor

Strasbourg, the Corbusian free plan 1'1$ .~IlI~iecledto ('ut'/alm grid serves (..~ iu; rotational Mis. piay o.f'strategic om i~sions. indicated by the hif/hi iyhled red col limns,

Palais des Congl'P-i' .s'

/ " .~ // -'" '\ /' / '\. \

/'

/~///, \

~ "

,

<9

/

~/

23. l'otais des Congl'iJs, third floor, On the third floor nly ol1e colu mil iB p,lin?'i nated, rpplaced by a 1itair

CMe. The missing cohwl.II fm'rm; It strl/cture q(arrested rotatioll. The disposition offigure.~ 0'11 tile third floor dltmonst.rates the 711ay between. what appears to be whole nowres Gild 'M./'tialjigl

24. 01/ the thinl j/.OOI; a continuO'l.i~ s(~ries of col limns fram(3j; the building (m three .side~, !Iet Oil tlli! interior of the building, the columns are 81:Zfri cliffe/'e;ltly. TIle larger columns divide the sql1are pluu illto a thlw:-bay ,~chema with an ABE arrangement ofthe,~e il11le,' I'OW.~.

AA Paluis ric!> Cong1'e:; Palais des ('ongre:s !I

~/

J5. Palais des COllyres,foltTlltjlo01: A second, subtler I/olotiou of the rolwnns occurs 08 they arc Mpa1'ated iI/to dommant rows. The perimeter co/millis are se

back.ti·om the sides butjfush.lo whot would be tl1I' rea,. of the buildl1lg. Entire bays of co[nTr/l/f; are I'emoved (red).

2(i. 0/1 tile fourth .lloor. the ,'emoool of wlllmn bays also slriates t!le plan i7lto (/ serie:; of linear elements t1wl, as they break daul1I and are inieJT1.I pted, allow the vOI'iolls grids to become figural elements. Thi,~

maintain.~ a continuitll of column.~ OJ/ tlte Oil/boor, II/u:face while lhe inner rows diuide into 1111 A buy, u B ba,lJ, and another B bay.

~~---

27. Palais des Congres,.lijth.lloOl: The central branch 18 no longer clear. Again there an! a IIcl·ie.~ (~r ]Jtl/"lial

ofOw mmp connect!; to thefift.h level. While thefigured figures on the jijlh ]ioor which lIape w/'res/lfmdcmres

fonn n.ftlle ramp is clearly (Ji.~ce""liblp ill. the thirdfioo with thejigumlform>; 011 the third and fourth flooi's.

alld roof [('vel, the shape of tire 1'(Unp 011 the fifth flom'

!J1

/

-

\ \

31, The geometry of the ,'ooF<I rlwml>oid shape seemlS

pinned 111/ a shlgle poi Ilt, echoing the ma 11111$1' 'ill wll ic!l a

.~ingfe 7m~~si'rlg collLmnfo/'ms the j'lI/C!'t/ mft))· ·~/JI:/'(/Iing

olJement ill lhe secolld. third aJldfrml'th .tl()ol',~,

//

(

/

"

/

~

"-,

P<llail' de~ Cungres _ _ _ __

J //

/ /// /

/'

\

,/ /

\

/

~~''''' ~ ~

", "

'""'~/

__________Palai~ de;; Congores

L9. The roof volume is warped into a 'rhombuid Ilhape and distorts tile horizontal datt/11I,

""

';:-

,/ /

!l(1

28. Pnl()..i.~ lies Congres, "oof level. The '~Jlil'ahllg fon'cs traced in eCLch leL'(jl echo the 11I0VeliWI1t ql'thc Tn mp. The warped sll/face of the 'roof levtll'eflf3ct:; this spil'alin.a mm'ement.

•

itl

The gl'01tl1d iR ne-I'M' Ie-vel: ii, ill C/il away liS a sll1:fac:e

01/(1 ,.i~e8 up inlo the bllildillg uritlilhe ramp (m-p),

p.

n.

I.

j.

-

F\"""~. - ~ I " .

m.

E r- r " ,I .=-. ( J I i?

The Iwilding i.~ cut intenmlly, rreatillg differellt sectiollal collrlitio'rl,~. The bllilding sectim/x /'pveal /Illlitipll) /'(!11icnllJOirk (i-I),

k.

Palais des C'onwes

O.

i.

__ _ .alais des Congres

h.

d.

r-

f

:Ollgres (a~f). The /.'oided plillth alld the depressioll (~f

tI/e gt'Olu/d at lite I)((8e of the building is also apporent (e-//.)

I.

---~-",=r- =bh~k_"--'--~J-'

c.

n~

e.

g.

JJ (a-p). Palais des COl/gri's, xecti(m~ and elemtiul/S. Tile buiLding .~ecli(ms and facade .fin'ther I'el'eal til w:mbled or "sandwlched" ur.qanizatioll oftlte P(Jlai.~ des

•

l!,}

"'.

'(:f'

/

"". "

" /

~/

'.'-,

.ii. Palais des Congl'es. The I'Omp joins the ot'OlI'nd mal 'oof hi a continWlnl.

Palais des Congres Palais des Congrb

//

/'

"

,/

~

91

JJ. Pala;s d.es Congres, fourth J1o()J~ ramp an second .floor. The ramp links the dijrel-i1l.g llil!ll'heel

rg(l1/'izafiol/.'1 ofeach level.

•

-'"

-.

~~

.::

~

-::: ~

;...

'-' ;:::"1::!e.s

0:

";..

t

~

-" "~ '"'°5 ~

l" c ..., 0 .. c s ;::; g '" '" ..,... ~

c

V '" '"tl

.~

C

"" "'"

•

/ /

/'6

""'--_

/

/

-,5

:r.

'~ u

•

/ ~~

/

//

./ /

//

" ./

,'..v /

•