Treatment of Infantile Capillary Hemangioma of the Eyelid with Systemic Propranolol

Laser and Other Treatment Options in the Therapy of Infantile Capillary

-

Upload

vidya-muthukrishnan -

Category

Documents

-

view

12 -

download

1

description

Transcript of Laser and Other Treatment Options in the Therapy of Infantile Capillary

LeH

D

R

A

soso©

K

I

ttwc[mestssarrC

1d

Medical Laser Application 25 (2010) 242–249www.elsevier.de/mla

aser and other treatment options in the therapy of infantile capillaryyelid and periorbital hemangiomas: An overvieweike M. Elflein∗, Bernhard M. Stoffelns, Susanne Pitz

epartment of Ophthalmology, University Medicine Centre, Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, Langenbeckstr. 1, 55101 Mainz, Germany

eceived 21 June 2010; accepted 27 July 2010

bstract

Hemangiomas in infancy generally require a multidisciplinary approach. As a result of their natural course, usually withpontaneous involution, a “watch-and-wait” strategy often seems to be sufficient. Nevertheless, in periorbital hemangiomas notnly cosmetic but also functional aspects may require an early intervention. There are many treatment options such as steroids,

urgery, cryotherapy, magnesium seeds and laser. The present paper focuses on the different types of laser used in the treatmentf infantile capillary eyelid and periorbital hemangiomas.2010 Published by Elsevier GmbH.

t[pctppp

magpdS

eywords: Infancy; Hemangioma; Laser; Amblyopia

ntroduction

Capillary hemangiomas are the most common benignumors in childhood, found in 8–12% of all infants duringhe first year of life, and in even up to 22% of preterm babiesith a birth weight of less than 1000 g [1,2]. They typi-

ally appear during the first weeks of life as small tumors3]. In the newborn, hemangiomas may originate as a paleacule with thread-like telangiectasia. As the tumor prolif-

rates, it assumes its most recognizable form: a bright red,lightly elevated, non-compressible plaque. Hemangiomashat lie deeper in the skin are soft, warm masses with alightly bluish color. Frequently, hemangiomas have both,uperficial and deep components. Hemangiomas range fromfew millimeters to several centimeters in diameter [4]. After

apid and often unpredictable growth in the first 6–9, or inare cases, 18 months of life, they gradually involute [5].omplete resolution often occurs until 7 years of age when

∗Corresponding author. Tel.: +49 6131 17 3324; fax: +49 6131 17 3455.E-mail address: [email protected] (H.M. Elflein).

ohiitht

615-1615/$ – see front matter © 2010 Published by Elsevier GmbH.oi:10.1016/j.mla.2010.07.004

hree quarters of the hemangiomas have completely involuted6,7]. Philipp et al. differentiate between typical developmenthases of hemangiomas: (1) prodromal phase without anylinical visible hemangioma sign, (2) initial phase in whichhe hemangioma may partially appear within a few days, (3)roliferation phase with fast proliferative rate, (4) maturationhase, in which proliferation comes to halt and (5) regressionhase with spontaneous involution of the lesion [8].

Hemangiomas can be distinguished from vascular malfor-ations, which in contrast do not show phases of growth

nd involution [9–11]. In about 80% of the cases heman-iomas are present as isolated tumors, whereas 20% of theatients show more than one hemangioma. A couple of syn-romes may be associated with hemangiomas for example,turge–Weber syndrome, which may be present with sec-ndary glaucoma or choroidal hemangioma. Half of theemangiomas are located on the skin of the head, especiallyn the nose, mouth, ear and eyelid areas [12]. The upper eyelid

s for unknown reasons 3–4 times more often affected thanhe lower eyelid [3]. Despite the described natural course ofemangiomas with a high chance of spontaneous regression,reatment is especially indicated for those cases involving

H.M. Elflein et al. / Medical Laser Application 25 (2010) 242–249 243

Fn

tAwbtlcaadb4mtap

O

(iftrogeMlidSa

R

tre

Fc

iLtE1tco7rufhc

Magnesium seeds

Magnesium seeds have been used for successful treatmentof hemangiomas for more than 100 years as a low-risk ther-

ig. 1. Eight-month-old infant: hemangioma at the left lower lid;o treatment so far.

he periocular region and thus causing significant visual loss.mblyopia or lazy eye i.e., poor vision in an eye that is other-ise physically normal, is a major ophthalmic problem. It cane caused by eyelid hemangiomas either directly obscuringhe visual field or causing ptosis. Another important factoreading to amblyopia is pressure from the hemangioma. Thisan distort the globe and lead to refractive errors such asnisometropia (unequal refractive power of the two eyes) orstigmatism. Moreover all these factors may compromise theevelopment of binocular vision, running the risk of stra-ismus. The incidence of these complications ranges from6% to as high as 80% [13–15]. There are quite a few treat-ent modalities for capillary hemangiomas. The purpose of

his paper is to introduce especially different forms of laserpplications for the treatment of infantile capillary eyelid anderiorbital hemangiomas.

verview of therapeutic options

Not every hemangioma demands active treatmentFigs. 1–3). Indications for treatment have to be based on thendividual findings. The aim of any therapeutic interventionor infantile capillary eyelid and periocular hemangiomas iso stop further growth of the hemangioma or to accelerateegression, and thus prevent functional loss. The guidelinesf the German Society of Dermatology with the workingroup Pediatric Dermatology together with the German Soci-ty for Pediatric Surgery and the German Society for Pediatricedicine [16] recommend control examinations at regu-

ar intervals depending on the age of the infant (one-weekntervals for each completed month of age). In the case ofocumented growth, active treatment has to be considered.everal treatment options have been applied over the years,s is discussed below.

adiation therapy

Historically, radiation therapy has been the preferredherapeutic approach in hemangiomas because they areadiosensitive, and they are even more so if they are treatedarlier in life [17,18]. Radiotherapy can be highly effective

Fm

ig. 2. Eight-month-old infant: hemangioma of the conjunctiva,lose-meshed controls, no complications so far.

n the management of capillary hemangioma [3,19,20].ow-level radiation can help to create microembolisms in

hese vascular tumors and speed regression of the mass.ither supervoltage or orthovoltage radiotherapy in the50–250 centigray (cGy) range is administered in a singlereatment, with appropriate shielding of the globe and adja-ent uninvolved tissues. An involutionary response usuallyccurs within 1–2 weeks. Cumulative doses of more than50 cGy should only be used on rare occations. Currentlyadiotherapy for these benign tumors in the pediatric pop-lation is hardly ever performed, because of the concernor radiation oncogenesis, such as thyroid cancer [21,22] oremangiosarcomas [23]. In addition, induction of radiationataract cannot be prevented safely.

ig. 3. Four-month-old infant: hemangioma of the upper lid, close-eshed controls, no complications so far.

2 aser Ap

a0tr[r

S

irlro[

C

fitno

S

sioc1biScswicettsa[ps[asoww

hsdftgiw

P

cPiei

L

hkgtgatit

sims

O

A

oIetiaaas

44 H.M. Elflein et al. / Medical L

peutic option [24]. This technique consists of implanting.5–1 mm thick wires of 99.8% pure magnesium into theumor mass. During repeated courses, oxidation of the metalesults in fibrosis and cicatricial transformation of the tumor25]. Nowadays, magnesium seeds are gradually becomingeplaced by newer treatment options, e.g. laser.

urgery

Surgery with complete or partial resection of the tumors indicated in sight-threatening hemangiomas which do notespond to other therapeutic options, or in small discreteesions that are amenable to total excision with minimalisk of morbidity [26]. It is also applicable for eliminationf fibrovascular remnants after regression of a hemangioma27].

ryotherapy

Cryotherapy is effective and of low risk in small super-cial hemangiomas [28], but might be painful and lead to

ransient distinctive swelling and permanent scars. Liquiditrogen cryotherapy also seems to be an effective treatmentption in conjunctival vascular tumors [29].

teroids and interferon alpha

Steroids can be used either as a systemic drug, as intrale-ional injections or topically. Systemic steroids might bendicated in rapidly diffuse growing hemangiomas, whenther treatment modalities are not possible. The mostommonly recommended oral corticosteroid dose is either–2 mg/kg body weight of prednisone daily, or 2–4 mg/kgody weight every second day [30]. Tumor shrinkages often dramatic and typically noted within two weeks.evere adverse effects include cushingoid facies, personalityhanges, gastric irritation, infection, weight gain, hyperten-ion, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and retarded growth [31],hich are said to be usually short-termed [32]. Intralesional

njection of steroids is typically performed by injecting aombination of a long- and a short-acting steroid under gen-ral anesthesia in the tumor. It seems to be an effectivereatment option, leading in most cases to complete reduc-ion of tumor volume and to the disappearance of the initialymptoms [33]. Usually injected doses are 40–80 mg tri-mcinolone and 4–8 mg dexamethasone or betamethasone34]. Injections usually have to be repeated to ensure thera-eutic success [35]. They bear the risk of local side effectsuch as hypopigmentation, cutaneous atrophy and infection36–38], as well as, very rarely, systemic adverse effectss mentioned above [38]. Adjunctive patching or glasses or

urgical debulking might be necessary to prevent from ambly-pia [39]. Orbital hemangiomas are also successfully treatedith sub-Tenon’s infusion of steroids [40]. Treatment optionsith interferon alpha are only reserved for life-threateningaoev

plication 25 (2010) 242–249

emangiomas as the side effects are both numerous andevere with neutropenia, elevated liver enzymes, spasticiplegia in 25–30% of the cases [41–43]. Therapy schemeor example is daily administration as a subcutaneous injec-ion, usually for a couple of weeks until the hemangiomaets softer and is apparently arrested in its growth [44]. Whenndicated, it is never used as monotherapy but in combinationith systemic steroids.

ropranolol

A novel and promising therapeutic agent in the treatment ofutaneous [45] and orbital [46] hemangiomas is propranolol.ropranolol is given at a low dose for several months [47],

n those few treated patients reported so far, no systemic sideffects were observed, while all hemangiomas were reducedn lesion size.

aser treatment

Treatment of hemangiomas with different types of laseras been performed since the 1980s. The wavelength of anyind of laser is absorbed much stronger from the red heman-ioma tissue than from the surrounding non-affected tissue,hus enabling the application of a higher energy in the heman-ioma tissue without damaging the neighboring tissue. Theim of laser treatment is to prepone the involution phase ofhe hemangioma by stopping the proliferation phase. Theres no single laser system, that can be successfully used forhe treatment of every kind of hemangioma.

The ideal laser for the treatment of infantile hemangiomashould have an appropriate wavelength (i.e. targeting thentravascular oxyhemoglobin), suitable pulse duration (toinimize damage to the surrounding healthy tissue) and a

uitable energy setting.

verview of used laser types

rgon ion laser

The argon laser was invented 1964 and is one in the groupf ion laser which uses a noble gas as active medium [48].t has been used in ophthalmology since 1968. Argon lasersmit at several wavelengths in the visible and ultraviolet spec-rum, the most powerful spectral lines are emitted at 488 nmn the blue and at 514.5 nm in the green. These wavelengthsre strongly absorbed by hemoglobin as well as by epidermalnd dermal melanin. The laser beam penetrates the epidermisnd coagulates pigmented structures in the basal cell layer anduperficial dermis at a depth of 1 mm [49]. Best results are

chieved in glaring red, superficial lesions [50,51]. The usef the argon laser in children is limited because of a restrictedffective depth of 1–2 mm and the nonspecific coagulation ofascular structures with an important risk of scarring [52].

aser Ap

C

iaattrocbtlo

F

wiaawiucdmtmesamlsftfihmanmiAltheewsa

ta

N

adma1adTTatFpIf[atlwA8amt

D

utgaistlmvpaoMv

H.M. Elflein et al. / Medical L

arbon dioxide laser

The CO2 laser is a molecular gas laser [48], which wasnvented in 1964. It emits a non-visible infrared beam withwavelength of 10,600 nm, especially targeting intracellularnd extracellular water but with no pigment preference. Whenhe energy is absorbed by water in the tissue, skin vaporiza-ion occurs with production of coagulative necrosis in theemaining dermis, thereby producing a coagulative sealingf the vessels at the site of the impact. The CO2 laser is espe-ially suitable for surgical hemangioma excisions as it makeslood loss easier to control. The incidence of scarring seemso be somewhat higher with the CO2 laser than with otheraser systems [53]. It is now especially used for the treatmentf intraoral hemangiomas [54].

lashlamp-pulsed dye laser

Infantile hemangiomas are currently preferentially treatedith the flashlamp-pulsed dye laser (FPDL), which was

nvented in 1966. The pulsed yellow light of the FPDL usesn organic dye as the lasing medium. Dye lasers, in whichflashlamp excites the dye to fluoresce, can cover a muchider wavelength range than the gas lasers such as the argon

on or carbon dioxide lasers. This feature makes them partic-larly suitable for tunable and pulsed lasers. Today, the mostommonly used FPDL has a wavelength of 585 nm, pulseuration of 0.3–0.45 ms and a penetration depth of approxi-ately 1.2 mm. As the wavelength of the FPDL corresponds

o one absorption peak of hemoglobin, the pulse energy isainly absorbed by blood vessels. It selectively destroys

ctatic blood vessels without significant side effects on theurrounding tissue [55,56]. For successful treatment the laserpplications have to be repeated several times. The most com-on side effects are transient edema and purpura, which may

ast up to 7–14 days [57,58]. The absence of hypertrophiccarring after FPDL treatment makes it a safe instrumentor the treatment of children [52]. Poetke et al. [59] showedhat the greatest degree of effectiveness was noted in super-cial hemangiomas in the involution phase: 61% of patientsad complete clearing of their lesion after 1.9 ± 1.2 treat-ents (range: 1–4) and 33% had good results. Landthaler et

l. [60] treated 28 patients with 37 hemangiomas. Twenty-ine were classified as superficial hemangiomas and eight asixed-type hemangiomas. The group obtained good results

n nearly 60% of superficial and 40% of mixed hemangiomas.n earlier study by Garden et al. [61] observed an average

ightening of 93.9% in lesions that were 3 mm or less inhickness after four treatments with the FPDL, and mixedemangiomas that were more than 3 mm in thickness light-ned in 85.1% but showed less reduction in thickness. Barlow

t al. [62] treated seven patients younger than 12 monthsith hemangiomas with the FPDL. All lesions showed aignificant reduction in size with improvement in skin colornd integrity. Additional dynamic epidermic cooling seems

ao9r

plication 25 (2010) 242–249 245

o be associated with lower rates of dyspigmentation andtrophy [63].

d:YAG laser

An alternative laser is the neodymium-doped yttriumluminum garnet (Nd:YAG) laser [48,64], which was firstemonstrated in 1964. This laser uses a crystal as lasingedium (the neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet)

nd typically emits an infrared beam with a wavelength of064 nm. This laser can be operated in a continuous as wells in a pulsed mode and can also be efficiently frequency-oubled to generate a laser light of 532 nm wavelength.he 1064 nm laser has a penetration depth of 5–7 mm [65].reatment with the Nd:YAG laser can be proposed whenhemangioma is proliferating very fast (Fig. 4a–c) or to

reat mixed or deep hemangiomas that do not benefit fromPDL treatment [52]. Alani and Warren [66] reported on 11atients treated with Nd:YAG laser for deep vascular lesions.n each patient a marked improvement was achieved withurther improvement after repeated treatments. Grantzow67] described 77–98% reduction of size of hemangiomasfter percutaneous Nd:YAG laser treatment, depending onhe number of treatments. Ulrich et al. [64] presented theong-term results of 20 patients treated with Nd:YAG laser,ith partial or nearly complete remission in 86% of the cases.similar success rate is mentioned by Civas et al. [68] with

0% of 25 patients with hemangioma treated 2.6 times onverage with Nd:YAG laser, even though in this study theean age of patients was 35.1 years, suggesting that not all

reated lesions were infantile hemangiomas.

iscussion and conclusion

Infantile hemangiomas occur in 8–12% of infants and inp to 22% of premature infants with a birth weight lesshan 1 kg. Girls are preferentially affected (3–5:1). Heman-iomas are typically present in the first days or weeksfter birth. Precursor lesions such as circumscribed telang-ectasias, anemic, reddish to bluish macules or port-winetain-like lesions may occur. Hemangiomas pass throughhree successive phases: a growth, a quiescent and an invo-ution or regression phase. Marked vascular changes at birth

ust lead to taking a congenital hemangioendothelioma or aascular malformation into consideration. During the growthhase (6–9 months, rarely longer) the hemangioma prolifer-tes variably and rapidly with surface extension, exophyticr endophytic subcutaneous growth, often in combination.ultiple hemangiomas may display dissociated growth. A

ariable long quiescent phase follows, regularly leading to

regressive phase. Depending on size and location, thisccurs at a variable speed and is usually completed by theth year of life. Small hemangiomas usually regress withoutesidual features. In contrast, larger hemangiomas often heal

246 H.M. Elflein et al. / Medical Laser Application 25 (2010) 242–249

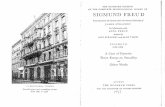

F orbitalu fter fivv

whct

sSga

ctttw

ig. 4. Course of a hemangioma. (a) Newborn, no pathologic peripper eye lid obstructing the visual axis. (c) At 29 months of age aisual functions.

ith telangiectasias, atrophy, scarring, cutis laxa, hyper- orypopigmentation or folds of fibrofatty tissue. These changesorrelate with the size of the hemangioma prior to enteringhe quiescent and regression phase.

Hemangiomas are generally (about 90%) localized,

harply circumscribed and originate from a central focus.everal forms are identified including cutaneous heman-iomas that are flat (at skin level) or slightly elevatednd subcutaneous hemangiomas as well as combinedh(fm

findings. (b) At 5 months of age with a huge hemangioma of thee treatments with Nd:YAG laser and surgery for residues, normal

utaneous–subcutaneous tumors. About 60% are found onhe head and neck. Segmental hemangiomas are less commonhan localized hemangiomas; they typically have a segmen-al pattern on the head. Some are sporadic and others occurith a syndrome (e.g. Sturge–Weber syndrome). Not all

emangiomas can be categorized into these two main groupsabortive or indeterminate hemangiomas). Further specialorms are hemangiomatoses (>10 cutaneous ± organ involve-ent) and rare congenital hemangiomas (rapid involuting

H.M. Elflein et al. / Medical Laser Application 25 (2010) 242–249 247

heman

chts

pbtatcweso[wamcsgia[frptttoi

Z

BH

Dd

ietufTShvig

S

R

Fig. 5. Treatment of infantile

ongenital hemangioma (RICH), non-involuting congenitalemangioma (NICH)). The relationship of RICH and NICHo hemangiomas is questionable due to a differing antigentructure (GLUT-1 negative) [16].

Periorbital hemangiomas usually require a multidisci-linary treatment approach (Fig. 5) with communicationetween the pediatrician, the ophthalmologist and the derma-ologist. The aim of any treatment is to prevent functional lossnd to avoid or minimize complications arising from ulcera-ion, scars, infection or bleeding. As a result of their naturalourse, there might even be cases in periorbital hemangiomashen “wait and see” with regular, close-meshed control

xaminations is the best option. This applies especially tomall hemangiomas which are not threatening visual functionr its correct development (Figs. 1–3). German guidelines16] recommend that control examinations are made at one-eek intervals for each completed month of age. Once visual

cuity is at risk or rapid growth is documented, active treat-ent has to be considered. To date, the FPDL has been

onsidered to be the most effective method with the fewestide effects for treating initial, superficial infant heman-iomas [58]. The continuous wave (cw) Nd:YAG laser withts greater depth of penetration can be used percutaneouslynd in special circumstances intralesionally via quartz fibers16]. Surgery often represents a definitive treatment optionor a hemangioma, but due to the high rate of spontaneousegression and the success of early laser therapy is now onlyerformed in selected cases. It is indicated if complicationshreaten that the condition cannot be controlled conserva-ively, in acute threat of functional loss of the eye, and as far asechnically possible for residual hemangiomas and when thebligatory scar produces esthetic disfigurement or functionalmpairment [16].

usammenfassung

ehandlung kindlicher Augenlid- und periorbitaler

ämangiome mit Laserie Behandlung kindlicher Hämangiome erfordert iner Regel eine multidisziplinäre Zusammenarbeit. Oft

giomas. Adapted from [16].

st eine abwartende, beobachtende Haltung ausreichend,ntsprechend dem natürlichen Verlauf mit meist spon-aner Regression. Nichts desto trotz können kosmetischend vor allem funktionelle Einschränkungen dennoch einerühzeitige Intervention erforderlich machen. Möglicheherapieoptionen sind die lokale oder systemische Gabe vonteroiden, Kryotherapie, Magnesiumspickung und Laserbe-andlung. Der vorliegende Artikel stellt insbesondere dieerschiedenen Lasertypen und deren Anwendungsbereichen der Behandlung von Augenlid- und periorbitalen Häman-iomen vor.

chlüsselwörter: Kindheit; Hämangiom; Laser; Amblyopie

eferences

[1] Enjolras O, Mulliken JB. The current management of vascularbirthmarks. Pediatr Dermatol 1993;10(4):311–3.

[2] Lieb W, von Scheven A. Hemangiomas of the eyelid area.Ophthalmologe 2001;98(12):1209–23, quiz 1224–5.

[3] Haik BG, Jakobiec FA, Ellsworth RM, Jones IS. Capillaryhemangioma of the lids and orbit: an analysis of the clinicalfeatures and therapeutic results in 101 cases. Ophthalmology1979;86(5):760–92.

[4] Drolet BA, Esterly NB, Frieden IJ. Hemangiomas in children.N Engl J Med 1999;341(3):173–81.

[5] Metry DW, Hebert AA. Benign cutaneous vascular tumorsof infancy: when to worry, what to do? Arch Dermatol2000;136(7):905–14.

[6] Bowers RE, Graham EA, Tomlinson KM. The natural his-tory of the strawberry nevus. Arch Dermatol 1960;82(5):667–80.

[7] Margileth AM, Museles M. Cutaneous hemangiomas inchildren. Diagnosis and conservative management. JAMA1965;194(5):523–6.

[8] Philipp CM, Poetke M, Berlien HP. Vascular tumors and mal-formations of the pelvic and genital region – Classification and

laser treatment. Med Laser Appl 2009;24(1):27–51.[9] Mulliken JB, Glowacki J. Hemangiomas and vascularmalformations in infants and children: a classificationbased on endothelial characteristics. Plast Reconstr Surg1982;69(3):412–22.

2 aser Ap

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

48 H.M. Elflein et al. / Medical L

10] Mulliken JB. A plea for a biologic approach to hemangiomasof infancy. Arch Dermatol 1991;127(2):243–4.

11] Mulliken JB, Glowacki J. Classification of pediatric vascularlesions. Plast Reconstr Surg 1982;70(1):120–1.

12] Cremer H. Gefäßanomalien im Bereich der Haut. MonatsschrKinderheilk 1998;146(6):622–38.

13] Robb RM. Refractive errors associated with hemangiomasof the eyelids and orbit in infancy. Am J Ophthalmol1977;83(1):52–8.

14] Stigmar G, Crawford JS, Ward CM, Thomson HG. Ophthalmicsequelae of infantile hemangiomas of the eyelids and orbit. AmJ Ophthalmol 1978;85(6):806–13.

15] Bogan S, Simon JW, Krohel GB, Nelson LB. Astigmatismassociated with adnexal masses in infancy. Arch Ophthalmol1987;105(10):1368–70.

16] Grantzow R, Schmittenbecher P, Cremer H, Höger P, RösslerJ, Hamm H, et al. Hemangiomas in infancy and childhood.S 2k Guideline of the German Society of Dermatology withthe working group Pediatric Dermatology together with theGerman Society for Pediatric Surgery and the German Soci-ety for Pediatric Medicine. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2008;6(4):324–9.

17] Paterson R, Tod MC. The radium treatment of angioma inchildren. Am J Roentgenol 1939;42:726–30.

18] Thoms J, Fjeldborg N. Radiation treatment of hemangiomas.Acta Radiol 1953;40(1):39–53.

19] Andrews GC, Domonkos AN, Post CF. Treatment of angiomas;summary of twenty years’ experience at Columbia Presbyte-rian Medical Center. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med1952;67(2):273–85.

20] Andrews GC, Domonkos AN, Torres-Rodriguez VM, Bem-benista JK. Hemangiomas: treated and untreated. J Am MedAssoc 1957;165(9):1114–7.

21] Talmi Y, Kalmanovitch M, Zohar Y. Thyroid carcinoma,cataract and hearing loss in a patient after irradiation for facialhemangioma. J Laryngol Otol 1988;102(1):91–2.

22] Haddy N, Andriamboavonjy T, Paoletti C, Dondon MG,Mousannif A, Shamsaldin A, et al. Thyroid adenomas andcarcinomas following radiotherapy for a hemangioma duringinfancy. Radiother Oncol 2009;93(2):377–82.

23] Ward CM, Buchanan R. Haemangiosarcoma following irradia-tion of a haemangioma of the face. (Case report). J MaxillofacSurg 1977;5(3):164–6.

24] Thierfelder S, Hagen R, Sold-Darseff JE, Uhlmann A. Mag-nesium seeding in therapy of pediatric hemangioma of thetemporal region, lower eyelid and orbit. Klin Monbl Augen-heilkd 1996;208(4):243–5.

25] Staindl O. Treatment of hemangiomas of the face with magne-sium seeds. Arch Otorhinolaryngol 1989;246(4):213–7.

26] Geh JL, Geh VS, Jemec B, Liasis A, Harper J, Nischal KK, et al.Surgical treatment of periocular hemangiomas: a single-centerexperience. Plast Reconstr Surg 2007;119(5):1553–62.

27] Haik BG, Karcioglu ZA, Gordon RA, Pechous BP. Capillaryhemangioma (infantile periocular hemangioma). Surv Ophthal-mol 1994;38(5):399–426.

28] Djawari D. Kontaktkryochirurgische Frühbehandlung des

Säuglingshämangioms. In: Kautz G, Cremer H, editors.Hämangiome – Diagnostik und Therapie in Bild und Text.Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Verlag; 1999. p. 55–64.29] Fraunfelder FW, Fraunfelder FT. Liquid nitrogen cryotherapyof a conjunctival vascular tumor. Cornea 2005;24(1):116–7.

[

[

plication 25 (2010) 242–249

30] Enjolras O, Riche MC, Merland JJ, Escande JP. Managementof alarming hemangiomas in infancy: a review of 25 cases.Pediatrics 1990;85(4):491–8.

31] Boon LM, MacDonald DM, Mulliken JB. Complications ofsystemic corticosteroid therapy for problematic hemangioma.Plast Reconstr Surg 1999;104(6):1616–23.

32] Pandey A, Gangopadhyay AN, Upadhyay VD. Evaluation andmanagement of infantile hemangioma: an overview. OstomyWound Manage 2008;54(5):16–29.

33] Abry F, Kehrli P, Speeg-Schatz C. Hemangioma of the eyelidsand orbit in children: therapeutic follow-up. J Fr Ophtalmol2007;30(2):170–6.

34] Kushner BJ. Capillary hemangiomas of the adnexa in infants.In: Hornblass A, editor. Oculoplastic, orbital and reconstructivesurgery. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1988. p. 243–50.

35] Verity DH, Rose GE, Restori M. The effect of intralesionalsteroid injections on the volume and blood flow in periocularcapillary haemangiomas. Orbit 2008;27(1):41–7.

36] Sloan GM, Reinisch JF, Nichter LS, Saber WL, Lew K, Mor-wood DT. Intralesional corticosteroid therapy for infantilehemangiomas. Plast Reconstr Surg 1989;83(3):459–67.

37] Chowdri NA, Darzi MA, Fazili Z, Iqbal S. Intralesional corti-costeroid therapy for childhood cutaneous hemangiomas. AnnPlast Surg 1994;33(1):46–51.

38] Chen MT, Yeong EK, Horng SY. Intralesional corticosteroidtherapy in proliferating head and neck hemangiomas: a reviewof 155 cases. J Pediatr Surg 2000;35(3):420–3.

39] O’Keefe M, Lanigan B, Byrne SA. Capillary haemangiomaof the eyelids and orbit: a clinical review of the safetyand efficacy of intralesional steroid. Acta Ophthalmol Scand2003;81(3):294–8.

40] Coats DK, O’Neil JW, D’Elia VJ, Brady-McCreery KM, PaysseEA. SubTenon’s infusion of steroids for treatment of orbitalhemangiomas. Ophthalmology 2003;110(6):1255–9.

41] Bauman NM, Burke DK, Smith RJ. Treatment of massiveor life-threatening hemangiomas with recombinant alpha(2a)-interferon. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1997;117(1):99–110.

42] Greinwald Jr JH, Burke DK, Bonthius DJ, Bauman NM, SmithRJ. An update on the treatment of hemangiomas in childrenwith interferon alfa-2a. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg1999;125(1):21–7.

43] Michaud AP, Bauman NM, Burke DK, Manaligod JM,Smith RJ. Spastic diplegia and other motor distur-bances in infants receiving interferon-alpha. Laryngoscope2004;114(7):1231–6.

44] Fledelius HC, Illum N, Jensen H, Prause JU. Interferon-alphatreatment of facial infantile haemangiomas: with emphasis onthe sight-threatening varieties. A clinical series. Acta Ophthal-mol Scand 2001;79(4):370–3.

45] Léauté-Labrèze C, Dumas de la Roque E, Hubiche T, BoraleviF, Thambo JB, Taïeb A. Propranolol for severe hemangiomasof infancy. N Engl J Med 2008;358(24):2649–51.

46] Li YC, McCahon E, Rowe NA, Martin PA, Wilcsek GA,Martin FJ. Successful treatment of infantile haemangiomasof the orbit with propranolol. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol2010;38(6):554–9.

47] Nguyen J, Fay A. Pharmacologic therapy for periocular infan-tile hemangiomas: a review of the literature. Semin Ophthalmol2009;24(3):178–84.

48] Berlien H-P, Müller GJ, editors. Applied laser medicine. Berlin,Heidelberg, New York: Springer Verlag; 2003.

aser Ap

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

[

H.M. Elflein et al. / Medical L

49] Shorr N, Goldberg RA, David LM. Laser treatment of juvenilehemangioma. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 1988;4(3):131–4.

50] Achauer BM, Vander Kam VM. Argon laser treatment ofstrawberry hemangioma in infancy. West J Med 1985;143(5):628–32.

51] Achauer BM, Vander Kam VM. Strawberry hemangioma ofinfancy: early definitive treatment with an argon laser. PlastReconstr Surg 1991;88(3):486–9; discussion 490–1.

52] Al Buainian H, Verhaeghe E, Dierckxsens L, Naeyaert JM.Early treatment of hemangiomas with lasers. A review. Der-matology 2003;206(4):370–3.

53] Glassberg E, Lask G, Rabinowitz LG, Tunnessen Jr WW. Cap-illary hemangiomas: case study of a novel laser treatmentand a review of therapeutic options. J Dermatol Surg Oncol1989;15(11):1214–23.

54] Bitar MA, Moukarbel RV, Zalzal GH. Management of congeni-tal subglottic hemangioma: trends and success over the past 17years. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2005;132(2):226–31.

55] Tan OT, Murray S, Kurban AK. Action spectrum of vascu-lar specific injury using pulsed irradiation. J Invest Dermatol1989;92(6):868–71.

56] Hohenleutner U, Hilbert M, Wlotzke U, Landthaler M.Epidermal damage and limited coagulation depth with theflashlamp-pumped pulsed dye laser: a histochemical study. JInvest Dermatol 1995;104(5):798–802.

57] Hohenleutner S, Badur-Ganter E, Landthaler M, HohenleutnerU. Long-term results in the treatment of childhood hemangiomawith the flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye laser: an evaluation of617 cases. Lasers Surg Med 2001;28(3):273–7.

58] Raulin C, Greve B. Retrospective clinical comparison ofhemangioma treatment by flashlamp-pumped (585 nm) andfrequency-doubled Nd:YAG (532 nm) lasers. Lasers Surg Med2001;28(1):40–3. Erratum in: Lasers Surg Med 2001;29(3):293.

[

plication 25 (2010) 242–249 249

59] Poetke M, Philipp C, Berlien HP. Flashlamp-pumped pulseddye laser for hemangiomas in infancy: treatment of super-ficial vs mixed hemangiomas. Arch Dermatol 2000;136(5):628–32.

60] Landthaler M, Hohenleutner U, el-Raheem TA. Laser therapy ofchildhood haemangiomas. Br J Dermatol 1995;133(2):275–81.

61] Garden JM, Bakus AD, Paller AS. Treatment of cutaneoushemangiomas by the flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye laser:prospective analysis. J Pediatr 1992;120(4 Pt 1):555–60.

62] Barlow RJ, Walker NP, Markey AC. Treatment of proliferativehaemangiomas with the 585 nm pulsed dye laser. Br J Dermatol1996;134(4):700–4.

63] Rizzo C, Brightman L, Chapas AM, Hale EK, Cantatore-Francis JL, Bernstein LJ, et al. Outcomes of childhoodhemangiomas treated with the pulsed-dye laser with dynamiccooling: a retrospective chart analysis. Dermatol Surg2009;35(12):1947–54.

64] Ulrich H, Bäumler W, Hohenleutner U, Landthaler M.Neodymium-YAG Laser for hemangiomas and vascular mal-formations – Long term results. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges2005;3(6):436–40.

65] Clark C, Cameron H, Moseley H, Ferguson J, Ibbotson SH.Treatment of superficial cutaneous vascular lesions: experiencewith the KTP 532 nm laser. Lasers Med Sci 2004;19(1):1–5.

66] Alani HM, Warren RM. Percutaneous photocoagulation of deepvascular lesions using a fiberoptic laser wand. Ann Plast Surg1992;29(2):143–8.

67] Grantzow R. Differential therapy of hemangiomas – Whencryotherapy, laser therapy or operation? Kongressbd Dtsch GesChir Kongr 2001;118:521–4.

68] Civas E, Koc E, Aksoy B, Aksoy HM. Clinical experi-ence in the treatment of different vascular lesions using aneodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet laser. DermatolSurg 2009;35(12):1933–41.

![Capillary thermostatting in capillary electrophoresis · Capillary thermostatting in capillary electrophoresis ... 75 µm BF 3 Injection: ... 25-µm id BF 5 capillary. Voltage [kV]](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/5c176ff509d3f27a578bf33a/capillary-thermostatting-in-capillary-electrophoresis-capillary-thermostatting.jpg)