Lang Lang May16 web - Chicago Symphony Orchestra · This is the piano concerto Prokofiev introduced...

Transcript of Lang Lang May16 web - Chicago Symphony Orchestra · This is the piano concerto Prokofiev introduced...

-

PROGRAM

ONE HUNDRED TWENTY-FIFTH SEASON

Chicago Symphony OrchestraRiccardo Muti Zell Music Director Yo-Yo Ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO

Saturday, May 21, 2016, at 8:00

Charles Dutoit ConductorLang Lang Piano

StravinskyFireworks, Op. 4

ProkofievPiano Concerto No. 3 in C Major, Op. 26 Andante—AllegroAndantinoAllegro ma non troppo

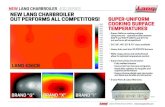

LANG LANG

INTERMISSION

StravinskyThe Firebird

This concert is generously sponsored by Ling Z. and Michael C. Markovitz and Bank of China.

This work is part of the CSO Premiere Retrospective, which is generously sponsored by the Sargent Family Foundation.

This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts.

-

2

COMMENTS by Phillip Huscher

Igor StravinskyBorn June 17, 1882, Oranienbaum, Russia.Died April 6, 1971, New York City.

Fireworks, Op. 4

This is the first music by Stravinsky the Chicago Symphony Orchestra ever played. Frederick Stock included it on the second half of his program on January 22, 1915, sand-wiched between music by Eric DeLamarter and the Queen Mab Scherzo from

Berlioz’s Romeo and Juliet. The program book mentions (in passing and without comment) a recent ballet by Stravinsky called The Rite of Spring; the importance of that score, one of the few truly revolutionary works of the twentieth century, wasn’t yet appreciated, even though it had caused a riot at its premiere in Paris little more than a year before.

F ireworks is a small piece of great his-torical importance. Stravinsky began it in the spring of 1908, at a time when he often went to see his beloved teacher, mentor, and recently appointed father-figure, Rimsky-Korsakov. “He seemed to like my visits,” Stravinsky later wrote. “He had my deep affec-tion, and I was genuinely attached to him. It

seems that these sentiments were reciprocated, but it was only later that I learned so from his family. His characteristic reserve had never allowed him to make any sort of display of his feelings.”

One day, Stravinsky mentioned to Rimsky-Korsakov that he was writing a new orchestral fantasy:

He seemed interested and told me to send it to him as soon as it was ready. I finished it in six weeks and sent it off to the country place where he was spending the summer. A few days later a telegram informed me of his death and shortly afterwards my registered package was returned to me: “Not delivered on account of death of addressee.”

Stravinsky dedicated Fireworks to Rimsky’s daughter Nadia, in honor of her marriage to Maximilian Steinberg. Apparently the Steinbergs didn’t appreciate the gesture, then or later. In fact, Stravinsky’s relations with Rimsky-Korsakov’s family deteriorated almost literally from the day of the funeral, when he and Rimsky’s widow had exchanged heated words. In 1962, when Stravinsky returned to Russia for the first time in nearly a half century and invited

COMPOSED1908

FIRST PERFORMANCEFebruary 6, 1909; Saint Petersburg, Russia

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCESJanuary 22 & 23, 1915, Orchestra Hall. Frederick Stock conducting

June 26, 1951, Ravinia Festival. William Steinberg conducting

CSO PERFORMANCES, THE COMPOSER CONDUCTINGNovember 7 & 12, 1940, Orchestra Hall

July 21, 1962, Ravinia Festival

MOST RECENT CSO PERFORMANCESJuly 7, 1968, Ravinia Festival. Seiji Ozawa conducting

September 11, 12 & 14, 2004, Orchestra Hall. Sir Andrew Davis conducting

INSTRUMENTATIONthree flutes and piccolo, two oboes and english horn, three clarinets and bass clarinet, two bassoons, six horns,

three trumpets, three trombones and tuba, bass drum, cymbals, glockenspiel, triangle, celesta, two harps, timpani, strings

APPROXIMATE PERFORMANCE TIME4 minutes

CSO RECORDINGS1946. Désiré Defauw conducting. RCA

1968. Seiji Ozawa conducting. RCA

1992. Pierre Boulez conducting. Deutsche Grammophon

-

3

Sergei ProkofievBorn April 23, 1891, Sontsovka, Ukraine.Died March 5, 1953, Moscow, Russia.

Piano Concerto No. 3 in C Major, Op. 26Performed as part of the CSO Premiere Retrospective

COMPOSED1927–31

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCESDecember 16 & 17, 1921, Orchestra Hall. The composer as soloist, Frederick Stock conducting (world premiere)

July 23, 1949, Ravinia Festival. Dmitri Mitropoulos conducting from the keyboard

CSO PERFORMANCES, THE COMPOSER AS SOLOISTJanuary 21 & 22, 1937, Orchestra Hall. Hans Lange conducting

MOST RECENT CSO PERFORMANCESApril 4, 5 & 6, 2013, Orchestra Hall. Yuja Wang as soloist, Sakari Oramo conducting

July 27, 2013, Ravinia Festival. Lang Lang as soloist, James Conlon conducting

INSTRUMENTATIONsolo piano, two flutes and piccolo, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trom-bones, timpani, bass drum, castanets, tambourine, cymbals, strings

APPROXIMATE PERFORMANCE TIME28 minutes

CSO RECORDING1960. Van Cliburn as soloist, Walter Hendl conducting. RCA

This is the piano concerto Prokofiev introduced to the world on this stage in 1921. Prokofiev’s ties to Chicago go back to the summer of 1917, when local businessman Cyrus McCormick, Jr., the farm machine magnate, met the twenty-six-year-old

composer Sergei Prokofiev while on a business trip to Russia. Prokofiev was unknown to McCormick, but the composer recognized the distinguished American’s name at once, because the estate his father had managed owned several impressive International Harvester machines. McCormick expressed an interest in the composer’s new music, and he eventually agreed

to pay for the printing of his unpublished Scythian Suite. He also encouraged Prokofiev to come to the United States, and asked him to send some of his scores to Chicago Symphony Orchestra music director Frederick Stock.

McCormick wrote to Stock at once, say-ing that Prokofiev “would be glad to come to Chicago and bring some of his symphonies if his expenses were paid. But not knowing myself the value of his music, I did not feel justified in taking the risk of bringing him here.” After Stock received Prokofiev’s scores, he replied to McCormick: “There is no question in my mind as to the talent of young Serge.” Although Stock at first doubted that it was feasible to bring the Russian composer to the United States right away, Prokofiev (or Prokofieff, as the U.S. press spelled his name at the time) made his debut

Nadia Steinberg to a concert of music which included Fireworks, she declined.

But Fireworks found a most receptive audience at the first performance in Saint Petersburg in 1909, for that night the crowd included the impresario Sergei Diaghilev. He was so impressed with Stravinsky’s music (the Scherzo fantastique also was performed) that he invited

him to orchestrate music by Chopin and Grieg for the upcoming ballet season in Paris and com-missioned him to compose the score for a new ballet he was planning on the Russian legend of the Firebird. The rest, of course, is history, but the fresh force of a singular new voice in music is felt throughout these four explosive, astonishing minutes of orchestral fireworks.

-

4

with the Chicago Symphony the following season, playing his First Piano Concerto under Stock’s baton and conducting the orchestra himself in the American premiere of his Scythian Suite in Orchestra Hall in December 1918.

“The appearance here of the young Russian, Sergei Prokofieff, at the Chicago Symphony Orchestra concert was the most startling and, in a sense, important musical event that has happened in this town for a long time,” wrote Henriette Weber in the Herald and Examiner. “Personally he is middle-sized and blond, somewhat gangling about the arms and shoulders, and entirely business-like in demeanor,” reported the Journal. “His business is his music, while he is on the stage, and he would seem to resent even the time that it takes to bow.” The music itself caused quite a stir. “Russian Genius Displays Weird Harmonies” was the headline in the American. “The music was of such savagery, so brutally barbaric,” Henriette Weber wrote, “that it seemed almost grotesque to see civilized men, in modern dress with modern instruments, performing it. By the same token it was big, sincere, true.” The public loved it. “Every man and woman there reacted to it,” Weber contin-ued, “and Prokofieff was given a thundering ovation that at least in a slight degree expressed the tumultuous emotions he inspired.”

In Chicago, McCormick introduced Prokofiev to Cleofonte Campanini, the director of the Chicago Opera, who asked the composer if he had written an opera. When Prokofiev explained that he had, but that the score for The Gambler was sitting on the shelf of the Mariinsky Theater back in Russia and would be difficult to obtain, Campanini hit on the idea of commissioning him to write a new opera for the Chicago company. That January, Prokofiev signed a contract to produce an operatic version of The Love for Three Oranges, based on the Russian adaptation of Venetian playwright Carlo Gozzi’s commedia dell’arte fairy tale, to be premiered in Chicago. By March, citrus growers in Florida and California were fighting over promotion rights. (One stated: “This succulent and healthful brand inspired Prokofiev and is used exclusively by him in this opera and at home.”)

Prokofiev expected to be back in Chicago the following winter for the premiere of The Love for

Three Oranges. But while rehearsals were under way that December, Campanini suddenly died; the premiere was postponed, first for one year, and then, because of financial disagreements, for yet another. Prokofiev finally returned to Chicago late in October 1921 to oversee the pro-duction of his opera. On December 16, Prokofiev took a break from rehearsals at the Auditorium Theatre to appear again at Orchestra Hall, playing his brand new Piano Concerto no. 3 with the Chicago Symphony. Two weeks later, the opera opened. Both were warmly applauded and recognized as scores of significance, although, in the end, the great Third Piano Concerto has proven less perishable than the Oranges.

A lthough Prokofiev would later call these his two “American” pieces, the piano concerto was written in the French countryside, on the coast of Brittany during a summer holiday in 1921, an unlikely pastoral setting for such a bustling, urban piece. Like his first two piano concertos, the work was written for his own hands, formidable and fearless at the keyboard. Prokofiev took his first piano lessons from his pianist mother; his great technical ability was apparent at an early age. He gravi-tated to the most challenging works; his concerto repertoire included Beethoven’s Emperor, the first two by Rachmaninov, and Tchaikovsky’s popular First. (He played earlier, classical works with his own “improvements.”) In 1937, just before Prokofiev’s last American tour, Francis Poulenc still marveled at how his “long, spatulate fingers held the keyboard as a racing car holds the track.”

Prokofiev’s first two piano concertos, both written before he finished his degree at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, are bold, chal-lenging scores. The flamboyant first (1911) was Prokofiev’s earliest controversial work (he later called it “footballish”); the ultramodern second (1913) left listeners “frozen with fright, hair standing on end,” according to a contemporary critic. Prokofiev had long wanted to write a new concerto, and had, in fact, been collecting material for years. This would remain his charac-teristic compositional method—making sketches as ideas came to him, at any hour of the day or night, and saving them until they found a place in his music.

-

5

Igor Stravinsky

The Firebird

The Firebird opened on June 25, 1910; on June 26, Stravinsky was a famous man. The great impresario Sergei Diaghilev had predicted as much—at one of the final dress rehearsals he pointed to Stravinsky and said, “Mark him well; he

is a man on the eve of celebrity.” Diaghilev was a good judge of such things, for in 1910 his circle included many of the most famous creative artists of the time. He was also, perhaps, excessively proud, for he had discovered Igor Stravinsky—or, to be more accurate, he was the one who put Stravinsky in the right place at the right time. The rest was all Stravinsky’s doing.

The right place was Paris in 1910. By chance, Diaghilev had heard Stravinsky’s music for the first time just two years before, at a concert in Saint Petersburg. He immediately invited the twenty-six-year-old composer to assist in orches-trating music for the 1909 ballet season in Paris.

But Stravinsky owes his first international success to Nikolai Tcherepnin and Anatole Liadov, both prominent, though modestly talented Russian composers who declined Diaghilev’s offer to write music for The Firebird. (Richard Taruskin has debunked the beloved old story that Liadov, a famous procrastinator, initially accepted but lost the job when Diaghilev learned that he was just stocking up on manuscript paper at the time the first installment of the score was due.)

The Firebird was a spectacular success. (See Stravinsky’s account, which follows.) According to Ravel, the Parisian audience wanted a taste of the avant-garde, and this dazzling music by the daring young Russian fit the bill. The Firebird was Stravinsky’s first large-scale commission, and, being an overnight hit, it was quickly followed by two more. The first, Petrushka, enhanced his reputation; the second, The Rite of Spring, made him the most notorious composer alive.

Both of those works were more revolutionary than The Firebird—less indebted to folk melody and the gestures of other masters—and spoke in a voice of greater individuality. But The Firebird

T he Third Piano Concerto incorporates sketches gathered over a decade. The earliest ideas date from 1911. The E minor theme that opens the second movement was sketched in 1913, and was intended from the start as the basis of a set of variations. In 1916–17, Prokofiev wrote down the two main ideas with which he would ultimately begin the piece, as well as two variations on the 1913 theme. A string quartet begun and abandoned en route to the United States in 1918 provided two themes for the finale. So when Prokofiev sat down to begin his new concerto during the summer of 1921, he had already written most of the important thematic material.

The score is a remarkable achievement, combining the brilliant, edgy momentum of Prokofiev’s previous music with a haunting new lyricism. All three movements benefit from the interplay of both elements; the balance is carefully judged: the second movement is calm

with fiery interludes, the finale just the oppo-site. The forms are essentially those that have ruled piano concertos since Mozart’s day—the first movement is a sonata-allegro, the second a theme and variations, the last a rondo—but the sonority and style are what we now recognize as Prokofiev’s own.

The Chicago premiere went well. The reviews were cordial but largely uncomprehending (“a plum pudding without the plums”). The audience was highly enthusiastic. The concerto quickly became Prokofiev’s calling card; within a year he played it in London, Paris, and New York. (“In Chicago there was less understanding than support,” the composer later recalled. “In New York there was neither.”) It was the first work he recorded (in 1932)—a blazing document of his fabled style and technique; and it was destined to become his most popular piano concerto (he would complete two others) and a favorite landmark of twentieth-century music.

-

6

Over the course of forty years, Igor Stravinsky was a regular guest conductor with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra at Orchestra Hall, the Pabst Theater in Milwaukee, and at the Ravinia Festival.

For his debut appearances on February 20 and 21, 1925, Stravinsky chose to con-duct his Song of the Volga Bargemen, Scherzo fantastique, Song of the Nightingale, and a suite from The Firebird. According to the Chicago American, “The audience was pleasantly agog yesterday and gave Mr. Stravinsky a stirring

welcome . . . . And what a conductor!” The reviewer, Herman Devries, continued, “I have rarely seen ‘effect’ so completely expressed and obtained as it was mirrored upon Orchestra Hall’s

platform yesterday. . . . [His conducting is] a study in expression, a marvelously magnetic picture of musical mood.”

Stravinsky guest conducted again in January 1935 and February 1940 before appearing to lead the world premiere of his Symphony in C—commissioned for the Orchestra’s fifti-eth season—on November 7, 1940. Edward Barry in the Chicago Tribune wrote, “In the course of the performance we caught our-selves muttering, ‘Ha! A major work!’ ” Robert Pollak in the Chicago Daily Times proclaimed that “Musical history is made at night and perhaps it was made last night at Orchestra Hall.” And Claudia Cassidy in the Journal of Commerce described the work as “both contemporary and timeless, autobiographical and impersonal. It has the lovely sense of form as much a part of all Stravinsky scores as indescribable richness of instrumentation is the signature of the finest. It is lyrical to the point of intoxication, and at the same time delicately, immaculately restrained.”

The composer continued to return regularly to lead the Orchestra, both down-town and at the Ravinia Festival. Stravinsky’s July 1964 visit included recording sessions of his ballet Orpheus for Columbia Records, and his last appearance was on April 17, 1965, conducting his Pulcinella in Orchestra Hall.

Frank Villella is the director of the Rosenthal Archives. For more information regarding the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s anniversary season, please visit cso.org/125moments.

Composers in Chicago

Stravinsky leads a recording session for his ballet Orpheus in Orchestra Hall on July 20, 1964

Chicago American, February 21, 1925

-

7

COMPOSEDNovember 1909–May 1910

FIRST PERFORMANCEJune 25, 1910, with Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes at the Paris Opera

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCES (SUITES)February 11 & 12, 1921, Orchestra Hall. Frederick Stock conducting

July 3, 1936, Ravinia Festival. Ernest Ansermet conducting

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCES (COMPLETE)February 8, 9 & 10, 1973, Orchestra Hall. Seiji Ozawa conducting

July 1, 1982, Ravinia Festival. Charles Dutoit conducting

CSO PERFORMANCES, THE COMPOSER CONDUCTING (SUITES)February 20 & 21, 1925, Orchestra Hall

January 14, 1935; Pabst Theater, Milwaukee, Wisconsin

January 17, 18 & 22, 1935, Orchestra Hall

February 27, 1940, Orchestra Hall

November 7, 8 & 12, 1940, Orchestra Hall

January 12, 14 & 15, 1954, Orchestra Hall

July 21, 1962, Ravinia Festival

MOST RECENT CSO PERFORMANCES (COMPLETE)August 9, 1984, Ravinia Festival. Michael Tilson Thomas conducting

January 21, 22 & 23, 2010, Orchestra Hall. Pierre Boulez conducting

January 31, 2010, Carnegie Hall. Pierre Boulez conducting

MOST RECENT CSO PERFORMANCES (SUITES)October 2, 3 & 4, 2014, Orchestra Hall. Riccardo Muti conducting

June 26, 2015, Morton Arboretum. James Feddeck conducting

July 12, 2015, Ravinia Festival. Ted Sperling conducting

INSTRUMENTATIONthree flutes and two piccolos, three oboes and english horn, three clarinets, clarinet in E-flat and bass clarinet, three bassoons and two contrabassoons, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones and tuba, timpani, triangle, tambourine, cymbals, bass drum, tam-tam, bells, xylophone, celesta, piano, two harps, and strings, with three trumpets, four tenor tubas, and bells playing offstage

APPROXIMATE PERFORMANCE TIME47 minutes

CSO RECORDINGS1969. Carlo Maria Giulini conducting. Angel (suite)

1992. Pierre Boulez conducting. Deutsche Grammophon (complete)

1996. James Levine conducting. Disney (suite)

2000. Pierre Boulez conducting. EuroArts (video, complete)

is one of the most impressive calling cards in the history of music—a work of such brilliance that, if he had written nothing else, Stravinsky’s name would still be known to us today.

A lthough Stravinsky later called the Firebird orchestra “wastefully large,” he used it with formidable clarity and imagination. “For me,” Stravinsky wrote, “the most striking effect in The Firebird was the natural-harmonic string glissando near the beginning, which the bass chord touches off like a catherine wheel. I was delighted to have discovered this, and I remember my excitement in demonstrating it to Rimsky’s violinist and cellist sons. I remember, too, Richard Strauss’s astonish-ment when he heard it two years later in Berlin.” The score is filled with delicious details, though none so novel as the one Stravinsky rightfully claimed as his own, and, in the closing pages, a magnificent sweep unmatched by much music written in the previous century and little since.

With The Firebird, Stravinsky found instant and enduring fame. “And, oh yes, to complete the

picture,” he later wrote, “I was once addressed by a man in an American railway dining car, and quite seriously, as ‘Mr. Fireberg.’ ”

Igor Stravinsky on The Firebird

I had already begun to think about The Firebird when I returned to Saint Petersburg from Ustilug, in the autumn of 1909, though I was not yet certain of the commission (which, in fact, did not come until December, more than a month after I had begun to compose; I remember the day Diaghilev telephoned me to say go ahead, and my telling him I already had). Early in November, I moved from Saint Petersburg to a dacha belong-ing to the Rimsky-Korsakov family about seventy miles southeast of the city. I went there for a vacation, a rest in birch forests and snow-fresh air, but instead began to work on The Firebird. Andrei Rimsky-Korsakov (son of the composer) was with me at the time, and he often was during the following months; because of this, The Firebird is dedicated to him. The introduction up to the bas-soon and clarinet figure at bar six was composed

-

8

in the country, as well as notations for later parts. I returned to Saint Petersburg in December and remained there until, in March, I had finished the composition. The orchestra score was ready a month later, and the complete music mailed to Paris by mid-April. (The score is dated May 18, but by that time I was merely retouching details.)

The Firebird did not attract me as a subject. Like all story ballets, it demanded descriptive music of a kind I did not want to write. I had not yet proved myself as a composer, and I had not earned the right to criticize the aes-thetics of my collaborators, but I did criticize them, and arrogantly, though perhaps my age (twenty-seven) was more arrogant than I was. Above all, I could not abide the assumption that my music would be imitation Rimsky-Korsakov, especially as by that time I was in such revolt against poor Rimsky. However, if I say I was less than eager to fulfill the commission, I know that, in truth, my reservations about the subject were also an advance defense for my not being sure I could. But Diaghilev, the diplomat, arranged everything. He came to call on me one day, with Fokine, Nijinsky, Bakst, and Benois. When the five of them had proclaimed their belief in my talent, I began to believe, too, and accepted.

Fokine is credited as the librettist of The Firebird, but I remember that all of us, and

especially Bakst, who was Diaghilev’s principal adviser, contributed ideas to the plan of the sce-nario; I should also add that Bakst was as much responsible for the costumes as Golovine. My own “collaboration” with Fokine means nothing more than that we studied the libretto together, episode by episode, until I knew the exact measurements required of the music. In spite of Fokine’s wearying homiletics, delivered at each meeting, on the role of music as an accompani-ment to dance, he taught me much, and I have worked with choreographers somewhat in the same way ever since. I like exact requirements.

I was flattered, of course, at the promise of a performance of my music in Paris, and my excitement on arriving in that city, from Ustilug, towards the end of May, could hardly have been greater. These ardors were somewhat cooled, however, at the first rehearsal. The words “for Russian export” seemed to be stamped every-where, both on the stage and in the music. The mimic scenes were especially obvious in this sense, but I could say nothing about them as they were what Fokine liked best. I was also deflated to discover that not all of my musical remarks were held to be oracular, and Pierné, the con-ductor, disagreed with me once in front of the whole orchestra. I had written “non crescendo,” a precaution common enough in the music of

THE FIREBIRD: A SYNOPSIS OF THE COMPLETE BALLET

Fokine’s adaptation of the fairy tale pits the Firebird, a good fairy, against the ogre Kashchei, whose soul is pre-served as an egg in a casket. A young prince, Ivan Tsarevich, wanders into Kashchei’s magic garden in pursuit of the Firebird. When he captures her, she pleads for her release and gives him one of her feathers, whose magic will protect him from harm. He then meets thirteen princesses, all under Kashchei’s spell, and falls in love with one of them. When he tries to follow them into the magic garden, a great carillon sounds an alarm and he is captured. Kashchei is about to turn Ivan to stone when the prince waves the feather; the Firebird appears. Her lullaby puts Kashchei to sleep, and she then reveals the secret of his immortality. Ivan opens the casket and smashes the egg, killing Kashchei.

The captive princesses are freed, and Ivan and his beloved princess are betrothed.

A scene-by-scene breakdown of Stravinsky’s score follows.

IntroductionScene 1:Kashchei’s magic garden—Appearance of the Firebird pursued

by Ivan Tsarevich—Dance of the Firebird—Ivan Tsarevich captures the Firebird—The Firebird’s entreaties—Appearance of the thirteen

enchanted princesses—The princesses’ game with the golden

apples (Scherzo)—Sudden appearance of

Ivan Tsarevich—The princesses’ khorovod

(Round dance)—

Daybreak—Magic Carillon, appearance of

Kashchei’s guardian monsters and the capture of Ivan Tsarevich—

Arrival of Kashchei the Immortal, Kashchei’s dialogue with Ivan Tsarevich, intercession of the princesses—

Appearance of the Firebird—Dance of Kashchei’s retinue, under the

Firebird’s spell—Infernal dance of all

Kashchei’s subjects—Lullaby (the Firebird), Kashchei

wakes up—Kashchei’s Death, deep shadows—

Scene 2:Disappearance of the palace and dissolution of Kashchei’s enchant-ments; animation of the petrified knights; general rejoicing

-

9

the last fifty years, but Pierné said, “Young man, if you do not want a crescendo, then do not write anything.”

The first-night audience glittered indeed, but the fact that it was heavily perfumed is more vivid in my memory; the gaily elegant London audience, when I came to know it later, seemed almost deodorized by comparison. I sat in Diaghilev’s box, where, at intermission, artists, dowagers, aged Egerias of the Ballet, “intel-lectuals,” balletomanes, appeared. I met for the first time Proust, Giraudoux, Paul Morand, Saint-John Perse, Claudel (with whom, years later, I nearly collaborated on a musical treatment of the Book of Tobit) at The Firebird, though I cannot remember whether at the premiere or at subsequent performances. At one of the latter I also met Sarah Bernhardt. She was thickly veiled, sitting in a wheelchair in her private box, and seemed terribly apprehensive lest anyone should recognize her. After a month of such society, I was happy to retire to a sleepy village in Brittany.

A moment of unexpected comedy occurred near the beginning of the performance. Diaghilev had had the idea that a procession of real horses should march on stage—in step with, to be exact, the last six eighth notes of bar eight. The poor animals did enter on cue all right, but they began to neigh and whinny, and one of them, a better critic than an actor, left a

malodorous calling card. The audience laughed, and Diaghilev decided not to risk a repetition in future performances. That he could have tried it even once seems incredible to me now—but the incident was forgotten in the general acclaim for the new ballet afterwards.

I was called to the stage to bow at the con-clusion, and was recalled several times. I was still on stage when the final curtain had come down, and I saw Diaghilev coming towards me, and a dark man with a double forehead, whom he introduced as Claude Debussy. The great composer spoke kindly about the music, ending his words with an invitation to dine with him. Some years later, when we were sitting together in his box at a performance of Pelléas, I asked him what he really thought of The Firebird. He said, “Que voulez-vous, il fallait bien commencer par quelque chose” [Well, you had to start with something]. Honest, but not extremely flatter-ing. Yet shortly after The Firebird premiere he gave me his well-known photo (in profile) with a dedication “à Igor Stravinski en toute sympa-thie artistique.” I was not so honest about the work we were then hearing. I thought Pelléas a great bore as a whole, and in spite of many wonderful pages.

Phillip Huscher is the program annotator for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

Costume designs by Léon Bakst for the Ballets Russes’ production of The Firebird, Paris Opera, 1910: the Firebird (left), Tamara Karsavina as the Firebird (center), the Tsarevna (right)

© 2016 Chicago Symphony Orchestra