KM Design Project

-

Upload

don-robison -

Category

Documents

-

view

216 -

download

1

description

Transcript of KM Design Project

T h e W a y A h e a d

1 | P a g e T h e F u t u r e o f K n o w l e d g e a t I n t e r n a t i o n a l R e l i e f

CREATING, MOVING, AND USING THE KNOWLEDGE WE NEED:

A MANDATE FOR KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT AT

INTERNATIONAL RELIEF

DON ROBISON

CHIEF KNOWLEDGE OFFICER

AUGUST 12, 2010

T h e W a y A h e a d

2 | P a g e T h e F u t u r e o f K n o w l e d g e a t I n t e r n a t i o n a l R e l i e f

Organization and Role Description

Organization Name: International Relief (fictional)

Type of Organization: International non-profit relief, development and advocacy agency working with

children, families, and communities to overcome poverty.

My Position. I am the new Chief Knowledge Officer of the organization. My salary is actually paid

through the donations of individuals and businesses which support my work.

Size of Organization: Based in the U.S., International Relief, boasts a home-staff of some 320 workers at

their Phoenix, AZ offices; and an international staff of over 1,500 working in 75 different countries.

Organizational Maturity. International Relief has grown steadily since its inception in 1955. It is

recognized worldwide for effective and sacrificial work with the poor. Workers are typically well-educated

and work together well. There is a strong and positive social and learning environment throughout the

organization.

Current Knowledge Management Activity. Led by young volunteers and staff in India, there are several

web-based communities of practice. A vocational training program near Amritsar, in the west of India,

trains software programmers. This group has created some custom applications that are used throughout

the organization: a web-based work area that stores documents, allows discussion threads, and facilitates

presentation.

Using their limited personal funds, workers in Pakistan planned and executed two-day meetings of workers

from several relief agencies to discuss the challenges of vocational training in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh,

and Sri Lanka. The attendees found the conferences so valuable (and encouraging) that the annual

conference has grown in three years from a meeting of 15 relief workers in Pakistan, to over 100 workers

from ten organizations who work throughout the region.

Existing Training Programs. International Relief operates two key training programs. Their traditional

orientation training program operates out of Phoenix, AZ and prospective field staff attend the program

prior to heading out to the field. This program is effective at transferring the organization‟s visions and

values, and for providing practical skills for cross-cultural relief work. The key trainers are experienced

field personnel who have a contagious passion for the work and great expertise. Students often say they

wish the initial training program were twice the length.

Field training is ineffective. Five paper-based correspondence courses are set up to train field staff in

specific areas. Although it is required that the field staff complete one course a year for the first five years,

less than 25% actually do. Feedback from students and other field staff rate these courses as “completely

irrelevant to our work.”

T h e W a y A h e a d

3 | P a g e T h e F u t u r e o f K n o w l e d g e a t I n t e r n a t i o n a l R e l i e f

Finances. International Relief operates solely off of the contributions of individuals and organizations.

The annual budget is just over $76 million. Many of the staff—both at home and on the field—are

volunteers. Remarkably, over 50% of the budget is devoted directly to relief, development, and advocacy.

Technological Infrastructure. Because of the widely dispersed nature of the work, the organization

required solar/satellite laptops for each field staff member. These laptops were purchased by the individual

staff member with an allowance provided for them and use different operating systems and web browsers.

Interestingly, over 97% of field personnel currently use Skype as their primary means of communication

and report reliable connectivity through their satellite connections, regardless of their physical location.

Main Bases of Operation:

The U.S. Home Office: 320 staff. These staff members are administrators, administrative support,

trainers, and spokespeople. Location: Phoenix, AZ.

o Additional 50 Recruiters and Representatives positioned in 25 U.S. urban areas

The International Office (London): 45 staff.

o Additional 15 Recruiters and Representatives positioned in 10 U.K. urban areas

Twelve key forward operating bases

o India (Supporting 35 teams representing 300 workers)

o Somalia (Supporting 18 teams representing 150 workers)

o Chad (Supporting 18 teams representing 135 workers)

o Sumatra (Supporting 15 teams representing 120 workers)

o Georgia (Supporting 10 teams representing 120 workers)

o Pakistan (Supporting 11 teams representing 135 workers)

o Iraq (Supporting 12 teams representing 145 workers)

o Caucasus (Supporting 9 teams representing 120 workers)

o Bolivia (Supporting 8 teams representing 135 workers)

o Mongolia (Supporting 12 teams representing 140 workers)

Problems that the entire organization would agree about:

Because of the de-centralized and widely disbursed nature of the organization, it is difficult for

newer field staff to benefit from the expertise of seasoned staff. And there are no reliable avenues

for that at this time.

Significant aspects of the work are similar in each location, but there is a sense that all efforts are

“first-time inventions.” People know that challenges have been met before, but they don‟t know

how to access lessons learned, or even what the challenges were.

People are excited to have satellite laptops. They have greatly improved morale and productivity,

but there is a daily sense of frustration over how the work is still isolated because of the lack of a

standard suite of desktop tools. Many have started saving documents to .pdf format for sharing, but

that leaves people frustrated when they want to make minor changes to existing documents and

cannot do it with their desktop tools.

Money is tight everywhere, and a dollar saved here or there may feed a starving child.

T h e W a y A h e a d

4 | P a g e T h e F u t u r e o f K n o w l e d g e a t I n t e r n a t i o n a l R e l i e f

T h e W a y A h e a d

5 | P a g e T h e F u t u r e o f K n o w l e d g e a t I n t e r n a t i o n a l R e l i e f

T h e W a y A h e a d

6 | P a g e T h e F u t u r e o f K n o w l e d g e a t I n t e r n a t i o n a l R e l i e f

The Way Ahead: The Future of Knowledge at International Relief

The poor of the world wait in breathless anticipation for International Relief to become truly

excellent at what we do. The work we have done to date has been remarkable, especially considering the

resources and people we have devoted to it, but hunger still kills 13,000 children a day and that figure is

climbing (World Vision, 2010). And, as we know from our daily work throughout the globe, hunger is just

one of the many faces of poverty. The purpose of this paper is not to present the grim status of world

poverty—though we all know it to be grim and have dedicated our lives to battling it. The purpose of this

paper is to present a rich strategic opportunity. We can significantly energize, unite and improve our

existing workforce, and perhaps facilitate innovative breakthroughs that will multiply the impact we can

have on our world.

In May 2010 our “Clean Water” well project in Cameroon was evaluated as a failure. We had

worked with the local people to dig new wells, but could not get them to believe that the water was cleaner

than the water they drank from the nearby polluted river. Apparently, there were animistic beliefs

confounding the issue that we underestimated. One jarring truth about this failure is that it was a repeat of

two failed well initiatives that we worked within 600 miles of the same location in a neighboring African

country six months earlier with the same cultural people group. We repeated the same failure three times

in six months without knowing.

The time has come for International Relief to develop a robust ability to

create, move, and use knowledge. It is time to benefit more broadly from what

we already know, and to create together the knowledge we need for the future.

Many of our people have demonstrated brilliance and creativity in overcoming the

challenges of their local situations, others have seen rich gains from solving

common problems as teams or in groups, still others have shown that distance and

separation can be bridged through creative use of money and technology. We

need to dramatically improve our knowledge management capacity so that we are

intentionally cultivating the knowledge and innovation we need to effectively meet

the challenges of a world in poverty. This paper presents a vision for

International Relief as a robust knowledge organization and presents a road map

for accomplishing the vision. It will also describe our current state presenting the

current needs and lost opportunities. The paper will conclude with a discussion of

the benefits of the proposed knowledge organization.

Many would ask, “Why now? We have been working with the poor for over fifty years, we‟ve done

well, why should we think about knowledge management now?” The first quick answer is that this is not

the beginning of knowledge management in International Relief, we have been intentionally growing and

innovating, teaching, mentoring, and sharing since our birth as an organization. Knowledge management is

not a new initiative at all. Second, not only have we been managing our knowledge since our birth as an

organization, but every organization does this in one way of another or they cease to exist (Davenport &

Prusak, 1998). Cultivating the expertise and knowledge to accomplish the things we have to accomplish is

fundamental to our organizational life, it is our breath.

T h e W a y A h e a d

7 | P a g e T h e F u t u r e o f K n o w l e d g e a t I n t e r n a t i o n a l R e l i e f

But, the third answer is the most compelling. We must now intentionally and significantly improve

our ability to grow, move, and use knowledge because of where our success has placed us: we are now

1,800 workers in 75 different countries around the globe. In that position we are poised to make a huge

impact on world poverty, but only if we are up to the challenge: only if our teams work synergistically, and

only if each of us is the best he or she can be. This means we

have to take every opportunity to intelligently confront

challenges, we have to think together in teams and groups, we

must innovate, and we must move the wisdom and expertise

that resides in pockets out into the peripheral regions of our

workforce. Further, advances in information communications

technology afford us opportunities that were not available

earlier. One great answer to the question, “Why now?” is the

technology that would make a revolutionary leap in

collaborative organizational learning possible is available to

us inexpensively.

A Vision for Knowledge Growth, Movement and Use at International Relief

We envision an organization where collaboration, synergy, innovation, wisdom, expertise, learning,

best practice, and communities of practice are the norm of our everyday work together. We envision an

organization where the challenges of poverty as they are addressed in one location inform the actions taken

by teams in others; where the hard lessons learned are shared freely and are accessible and valued by all.

We want to repeat effective practices as locally appropriate, improve ineffective practices, and

collaboratively develop breakthrough processes. Through modeling, proximity, interaction, and mentoring,

the wisdom and expertise of accomplished staff will be consistently transferred to new staff. Field workers

will have access to learning opportunities they value and the organization needs. International Relief

workers will see their work as part of a whole system of relief that includes the labors of many national and

international colleagues. Therefore, we will freely share and create forums for sharing that will result in

joint solutions to difficult shared challenges. We will value knowledge and facilitate its growth, movement,

and use throughout and around our work all over the world.

Anemic Knowledge Flow: Understanding The Current State

We have bright and innovative people doing amazing things around the world. The problem is, they

generally operate their own. As an organization we have not developed infrastructure, systems or good

opportunities for the knowledge of our people to flow or be of benefit to others. The following bullets

describe what we lose with our current systems and approaches:

Our teams reinvent solutions to the same problems on a daily basis. Our current goal is to get

qualified workers on the ground in the right places. The issue is that we have inadequate

communications and knowledge structures, so our teams cannot benefit from the work that has gone

before and they must invent new solutions to common problems every day. We should have

systems that allow teams to access the lessons learned by other teams.

Our success has put us in a unique

position: we have 1,800 workers in 75

countries… We are poised to make a

huge impact on poverty, but only if we

become great at growing, moving, and

using the knowledge we need.

T h e W a y A h e a d

8 | P a g e T h e F u t u r e o f K n o w l e d g e a t I n t e r n a t i o n a l R e l i e f

Though we have the expertise to handle most of our field challenges, no one knows where that

expertise resides. Over 65% of our field staff have over 10 years of experience. We know how

to do a lot of things, we boast experts in many domains. The problem is, we do not systematically

identify who those experts are. We do not know how to get to them.

Our junior people are operating in a vacuum and do not

routinely benefit from the experience and wisdom of our

senior and experienced people. We have recruited great

people, but they operate in twos and threes, and with our

current systems, they operate almost completely

independently. It is very difficult for a field worker to get

relevant advice or direction outside of his or her area of

operation.

The extreme wisdom, experience and contagious passion of our home office trainers is under-

utilized. Our home preparation training is exceptional, and field personnel would benefit from

continued contact with the home trainers, but there are currently no points of contact for that. The

wisdom and experience of our home trainers must be more creatively and effectively mined.

There is little creative friction or synergy in our organization. Problems are solved at the local

level almost all the time. Because our teams are so widely distributed, they are practically on their

own. But, the problems faced in each of our locations could help inform the solutions we use at all.

We must create venues for practitioners to meet, argue, dream, and invent together.

We have consistent identified knowledge/skill gaps in the field that our current training

programs do not address. Our field training is simply “broken.‟ This is a fact that the home office

and field representatives agree upon. Our field training must be attractive and relevant to our

people. We have a bright group and continuous learning is a core value for many of them. There are

many potential gains if we meet our people there.

Our staff is increasingly frustrated by the lack of a single compatible desktop suite. Documents created by one team are inaccessible by teams working nearby. Existing structured

knowledge in the form of documents is therefore suspended in a no-use zone because of software

incompatibility. We must develop a standard desktop productivity package to allow this basic

sharing of document types

.

We do not routinely work with local agencies engaged in similar work to achieve shared

solutions to problems. Even though the successful accomplishment of many of our local missions

would be accommodated through an active collaboration with others working in the area, we do not

have common practices or systems for sharing with them. We need to cultivate the value and build

the processes and systems to routinely do this in all our areas of operation.

In summary, we are not accomplishing all that we can as effectively as we can because of an

“anemic” knowledge flow. Our people are sometimes frustrated by barriers that appear to be easy to

overcome, but which nevertheless continue to defeat progress. The things we have discovered in parts of

our organization are not readily available in other parts of the organization that need them. It is time to

significantly improve the way we handle knowledge at International Relief.

Our junior people do not routinely

benefit from the experience or

wisdom of our experienced people.

T h e W a y A h e a d

9 | P a g e T h e F u t u r e o f K n o w l e d g e a t I n t e r n a t i o n a l R e l i e f

Mapping the Way to a Healthy Knowledge Ecosystem

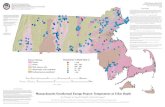

We are proposing two courses of action at this time. We propose that we adopt the full system of

systems approach depicted in Figure 1 as our long range goal for organizational knowledge management,

and secondly it is proposed that we approve the three phase implementation plan depicted in Figure 2 below.

The proposed system will work as a sort of “knowledge ecosystem.”

Figure 1. A representation of the functions and components of a mature knowledge management system

for International Relief. This diagram depicts both systems and processes.

As mentioned, for the short term, we are proposing that Phase 1 of the knowledge management roll-

out plan (depicted in Figure 2) be implemented in the next twelve months. Upon successful

implementation of Phase 1, we should regroup, publicize tangible victories, and proceed to Phase 2 of the

plan. Full implementation of all three phases should be completed by August 2013.

T h e W a y A h e a d

10 | P a g e T h e F u t u r e o f K n o w l e d g e a t I n t e r n a t i o n a l R e l i e f

Figure 2: The three phases of the implementation plan.

Three Phase Implementation Plan. The first phase of implementation will focus on areas where

our innovators have already developed successful prototypes or where we already have a clear consensus

regarding the organizational need. Phases 2 and 3 involve the implementation of new initiatives. While

these knowledge management approaches have been proven in various applications, their implementation

will involve dedicated labor and careful roll-out. This paper discusses Phase 1 implementation, leaving the

implementation of Phases 2 and 3 to the outline form presented in Figure 2.

Phase 1. Phase 1 implementation will involve the creation of an “Innovation Team” responsible for

planning the adoption of the knowledge initiatives, development and enterprise release of two significant

learning or knowledge systems, the establishment of a standard office desktop suite of software, and the

encouragement of two approaches that our people have shown to be effective. The proposed budget for

Phase 1 is attached as Appendix A. Each step will be led by a responsible organizational office, our

proposals for which office should lead each step is also described in Appendix A. A brief summary of the

substance of the Phase 1 plan:

T h e W a y A h e a d

11 | P a g e T h e F u t u r e o f K n o w l e d g e a t I n t e r n a t i o n a l R e l i e f

The Innovation Team. The first step is to recruit the “Innovation Team,” this is the group drawn

from all levels of the organization that will design and implement the roll-out. This team should

include key innovators who have already fielded knowledge management solutions, and include

influential representatives from communities of practice. This is not a publicity committee, this is

an „innovation adoption‟ group. Their task is to plan the best ways for our knowledge management

initiatives to fit into our organization.

Implement Standard Office and Collaborative Systems. The next two steps of Phase 1 are 1)

implementing the Open Office desktop suite for office functions, and 2) the adoption of Google

Groups as International Relief‟s standard online collaboration tool. These two steps will require

minimal cost but considerable computer support labor to download and install software. The U.S.

Home Office will be responsible for policy and roll-out communications.

Reengineer Field Training. The most significant enterprise labor and addition of Phase 1 will be

the reengineering of our Field Training and Education process. The U.S. Training Organization

will be responsible for this initiative. The following task sequence is anticipated:

o The U.S. Training Organization will conduct a

Needs Assessment to identify the performance

and knowledge gaps in the field. This Needs

Assessment will include extensive interaction

with field personnel. Needs will be identified

and prioritized in terms of “costs to mission

accomplishment.” Conclusions regarding needs

will be communicated back to field leaders for validation.

o After performance or knowledge needs (or desires) are objectively identified, the U.S.

Training Organization will identify and acquire or design and develop appropriate

interventions.

o Concurrently, the software programming school in Amritsar, India will modify the latest

version of Moodle in anticipation of use as a collaborative distance learning system.

o The U.S. Information Technology Office will conduct a survey of existing systems and

describe the performance characteristics and limitations of our current network and field-

available bandwidth.

By any objective measure, our

current field training system is badly

broken.

T h e W a y A h e a d

12 | P a g e T h e F u t u r e o f K n o w l e d g e a t I n t e r n a t i o n a l R e l i e f

Encourage Communities of Practice and Establish a Standard Two-way Communications

Medium. The last two implementation steps of Phase 1 involve taking successful local initiatives

and launching them enterprise-wide.

o First, Skype will be established by policy and by publicity as the official two-way

communications medium. Innovative or effective user stories will be regularly presented in

the monthly internal newsletter.

o Second, a “Group-It” seed fund will be established. The goal here is to encourage local

community of practice conferences such as the ones successfully conducted in Pakistan.

What Could We Gain?

The potential “wins” of this implementation plan are enormous, far outweighing the relatively

modest investment of labor and resources required by this plan. The general gains from implementation of

this entire plan will affect performance and personal engagement throughout International Relief. The

specific gains we may realize from Phase 1 implementation are clear:

Implementing Open Office as a standard desktop suite will yield the following gains:

o The substantial current barrier created by different document formats will be erased,

allowing for wide-spread structured knowledge sharing and reuse.

o Costs associated with Open Office are minimal.

o The Open Office suite is interchangeable.

Adopting Google Groups as our standard collaborative web groupware will yield the following

gains:

o Widely separated workgroups will be able to securely collaborate. Group documents and

contact information will be easily organized.

o Google Groups is offered to non-profit organizations at no cost.

o Our workforce already sees the web as the chief communications and collaboration

medium, this move builds on that existing value.

Conducting a needs assessment in the field and then acquiring or developing necessary content

with extensive field input will result in relevant offerings. This is an area that all of us agree is

in need of reengineering.

o Specifically, this could result in significantly improved field performance in our areas of

greatest need.

o This should reduce the frustration of our bright recruits who value learning as a lifelong

process.

o Having a good collaborative distance learning system like Moodle will dramatically

improve our ability to train at a distance. Using our own programmers, we can develop a

tailored application of this shareware at minimal cost.

T h e W a y A h e a d

13 | P a g e T h e F u t u r e o f K n o w l e d g e a t I n t e r n a t i o n a l R e l i e f

Adopting Skype as the standard two-way communications medium is a logical step. Formally

institutionalizing Skype as the organization‟s medium of choice validates the current use of this

powerful tool and also encourages the increased use of it. Providing user stories should increase

its innovative use.

Finally, the local community of practice conferences in Pakistan were huge successes. While

there is a bit of an art in making such meetings work, we want to encourage a lot more of this

sort of collaborative face-to-face meeting. This initiative also emphasizes a major cultural value

we want to push: we are in this challenge with others who help us think more holistically, who

help us develop solutions that are more powerful than if we develop them alone.

Conclusion

Organizations live or die by what they

know, by how they innovate and grow, and by how

they transfer and use the knowledge they have

(Davenport & Prusak, 1998; Gery, 1991; Rossett &

Schafer, 2007). Much of the critical expertise and

knowledge of an organization resides in the tacit

knowledge of its leaders and experts (Davenport &

Prusak, 1998; Wiig, 2000). Knowledge is

sometimes considered a “thing” but it is really more

fluid than that; as it exists within the minds and

hearts of experts it is often inexplicable (Davenport

& Prusak, 1998). Managing knowledge, then, is

difficult to do well, but the potential gains are enormous.

International Relief stands at a critical point in our organizational life, we have enjoyed significant

success with our work with the poor throughout the world, but that very success has positioned us in a place

where must improve our knowledge management structures and processes. The plan proposed here

encourages the growth of knowledge in every cell of our organization, it offers our people rapid gains and

the promise of significant long-term progress in areas they value. The plan recognizes the value of gaining

buy-in from leadership and rank-and-file members and proposes face-to-face, process, and technological

knowledge growth interventions. The world anxiously waits for us to get truly excellent at what we do: the

road to excellence is paved by improving our ability to grow, move and use the knowledge we need to solve

the problems presented by poverty.

Managing knowledge is difficult to do well, but

the potential gains are enormous.

Our success has put us in a position to accomplish

great things, but only if we become great at

managing the knowledge we need.

T h e W a y A h e a d

14 | P a g e T h e F u t u r e o f K n o w l e d g e a t I n t e r n a t i o n a l R e l i e f

References

Davenport, T.H. & Prusak, L. (1998). Working Knowledge: How Organizations Manage What

They Know. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Gery, G.J. (1991). Electronic Performance Support Systems. Tolland, MA: Gery Performance

Press.

Rossett, A., and Schafer, L. (2007). Job Aids and Performance Support: Moving From

Knowledge in the Classroom to Knowledge Everywhere. San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer.

Wiig, K.M. (2000). Knowledge management: An emerging discipline rooted in a long history.

In C. Depres & D. Chauvel (Eds.), Knowledge Horizons: The Present and the Promise of

Knowledge Management, (pp. 3-26). Boston, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann.

World Vision. (2010). Retrieved August 10, 2003 from http://www.worldvision.org/content.nsf/

pages/search-for-a-child?open&campaign=11935136&cmp=KNC-11935136&ttcode=hunger

T h e W a y A h e a d

15 | P a g e T h e F u t u r e o f K n o w l e d g e a t I n t e r n a t i o n a l R e l i e f

Appendix A: The Proposed Phase 1 Knowledge Management Project Budget

and Organizational Responsibilities Implementation Step Responsible Proposed Budget Note

Innovation Team, KM

Project Roll-out

CKO, Assistant

Director U.S. Office

$15 K

Implement Open Office as

standard office suite

CIO $10K Significant labor for CIO shop, little additional

cost

Implement Google Groups

as standard online

collaboration tool

Assistant Director,

U.S. Office

-- Cost neutral

Identify field needs,

acquire or design relevant

valuable training

U.S. Training Dept $260K Could involve partnering with Universities or

other training venues, or significant design and

development.

Establish Skype as two-

way communications

medium

Assistant Director,

U.S. Office, CIO

-- Cost neutral

Actively encourage local

community of practice

conferences

CFO, Regional Mgrs. $90K These funds should be used as “seed” to

encourage low-cost conferences like the

Pakistan conference. Should implement other

interventions to spotlight the approach and

availability of financial assistance.

T h e W a y A h e a d

16 | P a g e T h e F u t u r e o f K n o w l e d g e a t I n t e r n a t i o n a l R e l i e f

International Relief