Joaquin February 2014

-

Upload

roberto-radrigan -

Category

Documents

-

view

219 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Joaquin February 2014

JoaquínEducation & Inequality

FEBRUARY 2014 • YEAR 2 • Nº 6 • $3.50

Educacióny Desigaldad

Where Do Latino Interests Come In?¿Dónde se toma en cuenta al latino?

A message to the State Board of EducationMensaje para el Directorio Escolar Estatal

Underscoring the issue of UndermatchingSubrayando la disparidad

EnvIronmEnt / mEdIoambIEntEBuilding business, two-wheels at a time Creando economía, dos ruedas a la vez

LEgIsLaturE / LEgIsLaturEWill the Rainy Day Fund survive 2014?¿Sobrevivirá el 2014 el Fondo de Reserva?

bLack HIstory montH /mEs dE La HIstorIa afroamErIcanaStrange Fruit RevisitedReleyendo ‘Extraña Fruta’

2 Joaquín fEbruary 2014

PersonnelEditor-in-ChiefRoberto A. Radrigá[email protected]

PublisherJess Cervantes /Leading [email protected]

Composition, Layout& All IllustrationsGráfica Designwww.graficadesign.net

ContributorsMax VargasSacramento, CARoxanne Ocampo San Marcos, CAScott WynnStockton, CAMarisa Méndez, DDSStockton, CA

Joaquín

Joaquín is an English & Spanish bilingual publication addressing relevant Latino issues in the California’s Northern Central Valley. It is published monthly by Leading Edge Diversified Ventures, a Lodi, CA-based LLC.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Any use of materials from this publication, including reproduction, modification, distribution or re-publication, without the prior written consent of LE, LLP, is strictly prohibited.

Joaquin is printed by LE Printing Services, a union print shop

EditorialBoardInés Ruiz-Huston, PhDGene Bigler, PhDRichard RíosManuel CamachoJeremy TerhuneCandelaria Vargas

Offices2034 Pacific AvenueStockton, CA 95204(209) [email protected]

Advertising & SubscriptionsLeading Edge11940 N. Lower Sacramento Rd.Lodi, CA [email protected](209) 948-6232

our mission is to provide the Latino community of california’s central valley with an unbiased mirror of our society, to advocate civic duty and participation, to celebrate the successes and achievements of our peers, and to provide a tribune for emerging Latino leadership.

Current Issues /ActualidadWhere do Latino Interests come In? /¿dónde se toma en cuenta al latino?

Education & Inequality/Educación y Desigualdada message to the state board of Education /mensaje para el directorio Escolar Estatal

Environment / Medioambientebuilding business, two-wheels at a time /creando economía, dos ruedas a la vez

Students’ Voices / Voces Estudiantilesmy Journey to success / Peregrinaje al triunfo

Money / EconomíaWhen you are no longer you/cuando ud. es otroPreparing for the next generation / Preparándose para la próxima generación

Legislature / LegislatureWill the rainy day fund survive 2014? /¿sobrevivirá el 2014 el fondo de reserva?

SUSD: susd launches LcaP / susd lanza LcaPParents don graduation caps /Padres visten gorra de graduación

Black History Month/Mes de Historia Afroamericana‘strange fruit’ revisited

SJCOE : Honor musicians shine at concert /músicos de Honor marcan la nota

Education & Inequality/Educación y DesigualdadQuetzalmama: the issue of undermatching /subrayando la disparidad

Chican-izmos: Love notes from a tough love teacher/Inflexible por su propio bien

Perspective / Punto de Vistaregarding true immigration reform /sobre una verdadera reforma inmigratoria

EthnoTales / EtnoRelatosmiddle school malaise/tormento de escuela intermedia

Literature / Literatura: ‘traqueros’

Legal Bits / Datos Legales: daca

Short Stories /El Cuentothe man from the south / El hombre del sur

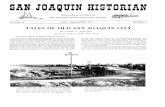

covEr: a robErto radrIgÁn & rIcHard rÍos coLLaboratIon

February 2014

In This IssueEn Este Número

3

5

7

8

910

11

12

13

14

16

17

19

20

23

24

25

fEbruary 2014 Joaquín 3

Where Do Latino InterestsCome In?

C U R R E N T I S S U E S • A C T U A L I D A D

za, “la disparidad se ha acrecentado. El

avance socioeconómico se ha detenido…”

Las estadísticas sobre desigual-dad las puede ver cualquiera hoy en día y son innegables: desde 1979 la pro-

ductividad en los EEUU —el valor del trabajo de los trabajadores— se ha incrementado en un 90 porciento, sin embargo el ingreso familiar solo ha crecido en un 8 porciento. El 95

porciento del aumento en ingreso durante los últimos 4 años —práctica-

mente todo el avance de nuestra economía desde la crisis del 2009— ha recaído en

apenas un uno por ciento de la población pro-ductiva. En los 1970s, el sueldo promedio de un ejecutivo era 30 veces el de un trabajador, pero hoy es 273 más alto, y una familia de ese uno por ciento es 288 más alto que el de una familia promedio. Y un dato más: la razón por la que crece la demanda de Cupones de Alimento es el aumento de familias que de-penden de un sueldo mínimo, lo que los deja muy debajo del límite de pobreza.

La experiencia en el aumento de la des-igualdad y menor acceso al bienestar económi-co en nuestra área es indudable. El desempleo en los condados San Joaquín y Stanislaus es alrededor del 13 por ciento, y 4 a 7 puntos superior entre la gente de color, en contraste al siete por ciento nacional y al menos del seis por ciento entre condados californianos más acaudalados. En el Valle —donde dos tercios de los niños de 3 a 4 años son latinos— menos de un 43 por ciento de ellos recibe educación preescolar. En condados más pudientes es el 58 por ciento. Por acá menos de un cuarto de los adultos sobre 25 años tiene título de educación superior, aunque el promedio estatal es 36 por ciento y en condados de mejores ingresos es sobre 46 por ciento. Más del 19 por ciento de nuestros jóvenes entre 16 y 24 años ni trabajan ni estudian, creando la llamada población desconectada de donde se nutre la mayoría de las pandillas y la violencia. En california y el resto del país el promedio de desconectados es de un 15 porciento, mientras que en condados pudientes es entre un 10 y 13 porciento. No es de extrañarse, entonces, que hace poco experimentásemos 800 crímenes violentos por 100 mil habitantes en el Condado San Joaquín, cuando en otros

dr. gene E. bigler, stockton, caAs I listened

to the Presi-dent’s State of the Union Address and the Republican responses on January 28, I kept asking myself how these contrast-ing political positions affect Latino interests. President Obama laid out a clear and hard to reject goal for the nation to “…make this a year of ac-tion….to build ladders of opportu-nity for the middle class.” He added that, despite great gains in wealth for a few, “inequality has deepened. Upward mobility has stalled…”

The data about inequality are widely available and mostly beyond questioning now: since 1979, U.S. productivity – that is the value of what workers make or do -- has increased by 90 percent, but family income has risen only 8 percent. Ninety-five percent of the increase in personal income over the last four years, almost all of the gains in our economy since the 2009 recession, has gone to just the top one percent of the income earners. Average CEO pay was 30 times average worker wages in the 1970s, but is now 273 times higher, and a family in the top one percent in income today is worth 288 times as much as a typical family. Furthermore, the single factor that is driving Foods Stamps demand is the increase in the number of families who depend on minimum wage jobs that leave them far below the poverty line.

Our local experience with widening in-equality and diminished access to opportunity is beyond question. Unemployment in San Joaquin and Stanislaus counties is about 13 percent, and four to seven points higher for people of color, in contrast to about seven per-cent joblessness nationwide and less than six percent in wealthier California counties. Less than 43 percent of children ages three and four here in the valley, where two thirds or more are Latinos, have access to pre-school educa-tion, while the statewide average is 49 percent and in wealthy counties with few Latinos it is above 58 percent. In our area, less than a quarter of adults 25 and older have any univer-sity degree, but the state average is 36 percent and wealthy counties are above 46 percent.

Over 19 percent of our youth, ages 16-24, are not working or attending school, creating the so called disconnected population that continúa a la vuelta

ACCESO A OPORTUnIDADES

¿Dónde se toma en cuenta al latino?

provides much of the fodder for gangs and violence. In California and nationwide the average is about 15 percent disconnected, and in wealthy counties between 10 and 13 percent. Not surprisingly, we recently experienced over 800 violent crimes in San Joaquin County for 100,000 people, in contrast to an average of just over 400 in California counties and of 386 in other states.

These last sets of statistics all come from the Opportunity Nation Index. The non-partisan Op-

ACCESS TO OPPORTUnITy

Al escuchar el discurso Estado de la Unión del presidente el 28 de enero y la reacción

de los republicanos no puedo sino preguntarme cómo estas contradictorias posiciones afectan los intereses latinos. El presidente Obama de-claró una meta difícil de resistir, hacer este “el año de la acción… crear escalas de oportuni-dad para la clase media.” Añadió que, aunque algunos han aumentado grandemente su rique-

continued on next page

4 Joaquín fEbruary 2014

condados californianos era de 400, y 386 en los otros estados.

Estas últimas esta-dísticas provienen del Índice de Opportunity Nation (Nación de Opor-tunidades). Opportunity Nation, entidad apar-tidista, ha establecido áreas clave que propician el acceso a oportunida-des en general: educa-ción pre-kinder a todo

niño entre 3 y 4 años, proporción de partici-pación ciudadana en programas cívicos y vo-luntarios, mantener a los jóvenes en la escuela, obteniendo títulos universitarios y acceso al empleo. La meta de Opportunity Nation es que en este país el avance socioeconómico no esté ligado a un código postal.

Para esta encrucijada nacional ¿Qué medi-das recomendaron el presidente Obama y los muchos republicanos que respondieron a su discurso? El Presidente dijo que si el Congreso no se pronunciaba a sus propuestas utilizará su limitada autoridad ejecutiva para seguir adelante. Por ejemplo, incluso si el Congreso no sube el sueldo mínimo para el país, él —por decreto presidencial— puede obligar que todo contrato federal cumpla con un sueldo mínimo superior. Nuevamente enfatizó sobre una total reforma inmigratoria para que los inmigrantes puedan competir por empleos y obtener una educación, sobre acceso universal a todo niño de 3 y 4 años a educación pre-

Acceso a oportunidadviene de la vuelta

Access to Opportunitycontinued from previous page

portunity Nation has determined crucial areas foster the access to opportunity in general: pre-kindergarten education for all three-and four-year olds, degree of citizen involvement in civic and volunteer programs, keeping youth in school, earning of college degrees, and access to employment. The goal of the Opportunity Nation program is to prevent zip codes from determining upward mobility in America.

So what actions did President Obama and the many Republicans who responded to his speech recommend for dealing with this in-creasingly crucial problem for America? The President said that if Congress does not act on his recommendations, he will use the limited Executive authority he has to move ahead. For instance, even if Congress does not increase the minimum wage for the country —by exec-utive order— he can require that federal con-tracts meet a higher level of minimum wage.

He again emphasized comprehensive immigration reform in order to enable immi-grants to compete for jobs and acquire educa-tion, universal access for three- and four-year olds to pre-kindergarten, programs to reduce the cost of college education and increased access to technology in poorer areas, expanded worker training programs, restored funding for unemployment insurance, financing of energy and transportation infrastructure projects, and so on. It is quite an impressive array of fairly specific measures, even if he has advocated most of them before.

Republican responses to the President’s ad-dress were different in some respects but alike in a few ways. All four of the statements I re-viewed were lacking in specifics and neglected any concern for inequality, in contrast to the emphasis they placed on reducing government spending and the size of our public debt. All four also said the main challenge was to re-duce the size of government. They mentioned, repeatedly, the Keystone Pipeline— project that rather than reduce inequality will primar-ily benefit the wealthy oil and gas industry.

The Republicans also shared one other statement —perhaps stated most simply by Congresswoman McMorris Rodgers about a different gap: “(the key problem for the nation is that)…the President’s policies are making people’s lives harder. Republicans have plans to close the gap.” Of course, the primary ex-ample given for the harder lives Obama is caus-ing relates to the bureaucratic snafus due to the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, but perhaps by calling it a gap will make it seem as important as the income gap and inequality.

Which approach do you think will better serve Latino interests?

kinder, programas que reduzcan el costo de la universidad y un mejor acceso a tecnología en barrios populares, ampliación de programas de capacitación laboral, reinstauración de fondos para el seguro de desempleo, financiación de proyectos energéticos y de infraestructura, y otros. Una impresionante lista de medidas con nombre y apellido, incluso si ya las ha propuesto antes.

Las respuestas republicanas al discurso presidencial fueron diferentes en ciertos pun-tos pero similares en otros. Las cuatro decla-raciones que analicé carecían de específicos o de cualquier preocupación por la desigualdad. Esto comparado al énfasis dedicado a reducir el gasto gubernamental y el volumen de nues-tra deuda pública. Los cuatro también dijeron que el principal reto era reducir el tamaño del gobierno. Mencionaron, repetidamente, el Oleoducto Keystone —proyecto que en lugar de reducir la desigualdad beneficiará, particularmente, a la acaudalada industria del gas y el petróleo.

Los republicanos también repitieron otro punto —quizá mejor sintetizado en una frase de la congresista McMorris Rodgers refirién-dose a otra brecha: “(el problema crucial para la nación es que) …las políticas del Presidente están dificultando la vida de la gente. Los republicanos tenemos planes para acortar la brecha.” De hecho, el principal ejemplo de obs-taculización que dan es un problema burocrá-tico de implementación del Acta de Atención Medica Accesible pero, al catalogarlo como brecha, le da la relevancia de una brecha como la de la desigualdad socioeconómica.

¿Cuál énfasis aprovecharía mejor a los intereses latinos?

C U R R E N T I S S U E S • A C T U A L I D A D

Gene Bigler, PhDWriter & consultant on global affairs,former professor, retired diplomat

“This massive concentration of eco-nomic resources in the hands of fewer

people presents a significant threat to in-clusive political and economic systems.

Instead of moving forward together, people are increasingly separated by

economic and political power, inevitably heightening tensions and increasing the

risks of societal breakdown…”OxFAM InTERnATIOnAL, 2014

“Esta masiva concentración de recursos económicos en las manos de unos pocos

presenta una importante amenaza a los sistemas políticos y económicos. En lugar de avanzar juntos, la gente está cada vez más separada por el poder

económico y político, inevitablemente acrecentando las tensiones y el riesgo de

una quiebre social…”

CORRECTIOnCORRECCIÓnIn JOAQUÍN’s January printed

issue, under the heading “El Grito that changed Latinos article in Politics” by Jess Cervantes it said: “a Latino turnout of 400,000 —enough to win a statewi-de election”. It should say “—far from enough to win…” We regret the confu-

sion this may have caused among readers.En la edición impresa de JOAQUÍN

en enero, bajo el titular “El Grito que cambió al latino en la política” por Jess Cervantes, se imprimió “unos 400 mil latinos a las urnas —suficientes como para ganar cualquier elección estatal”.

Debió decir “—lejos de suficiente…” La-mentamos la confusión que pueda haber

causado entre los lectores.

fEbruary 2014 Joaquín 5

davía en riesgo. Que, aunque los salones de clase están mejor in-tegrados, son muchos los estudiantes vul-nerables y en-riesgo que siguen posterga-dos. Por esto la legis-latura de California —a insistencia del gobernador Brown— revisaron la manera en que se asignan los fondos: desde julio del 2013, la ley dicta que el estudiantado desfa-vorecido reciba mayor financiación.

No obstante, se-gún el editorial del Sa-cramento Bee fechado el 14 de enero, 2014, “en un mundo perfec-to, los extra dólares

para estudiantes marginados se asignarían directamente a las escuelas. No obstante la ley asigna esos dólares a los distritos locales (…) Hay muchas lagunas” (para garantizar la apropiada distribución de esos fondos). Por eso se realizó esta audiencia pública.

La sospecha que fondos designados para estudiantes que viven en la pobreza, en cus-todia temporal, o cuyo lenguaje no es inglés —junto al dinero existente para estudiantes incapacitados— podría ser desviado con otros propósitos atrajo a más de 330 personas al mi-crófono. De hecho, en una junta del Directorio Escolar de Stockton el pasado noviembre hubo representantes del distrito que reclamaban más flexibilidad. Ya no se escuchó más de eso.

La mayoría de aquellos que escuchamos en Sacramento eran superintendentes de escuelas públicas o sus representantes, todos comprometiéndose públicamente a garantizar que los dineros de la Fórmula de Control de Financiación Local (LCFF, por sus siglas en inglés) se apliquen bien. El gobernador Jerry Brown hizo una sorpresiva aparición y habló por más de diez minutos en esa manera suya, con sentido, real, llamando a aceptar el reto. Algunos lo hicieron, como Dolores Huerta, sentada junto a la única representante del Distrito Escolar de Stockton, Gloria Allen. Allen se comprometió en el intento de usar los fondos como dicta la LCFF.

Pero Stockton, como siempre, tuvo repre-sentantes alternativos. Padres y Familias de San Joaquín (FFSJ, por

E D U C A T I o N & I N E q U A L I T y • E D U C A C I Ó N y D E S I g U A L D A D

A message to the State Board of EducationGreat things have

happened on a bus. I was born the year that Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat, launching the Montgomery Boycott, breathing new life into the Civil Rights Movement.

Recently, I rode in a different busload of motivated people headed to Sacramen-to. Arriving Thurs-day, January 16th, we, too, hoped to make some difference. We, too, believed that civil rights are still at stake. That, although classrooms are better integrated, vulnerable and at-risk students often still find themselves underserved. And so California’s State Legislature —at Gover-nor Brown’s urging— overhauled the way in which money is distributed: as of July of 2013, the law mandates that disadvantaged students receive higher funding.

Yet, according to the January 14, 2014 Sacramento Bee editorial, “In an ideal world, the extra dollars for disadvantaged kids would go directly to schools. Instead, the law dis-tributes the dollars to local districts (…) Major loopholes remain” (on how to ensure proper distribution of the funds). That’s why this public hearing was held.

Concerns that funding for students who are under the poverty line, in foster care, or whose first language is not English -- together with existing funds for students with disabili-ties -- would be diverted for other purposes brought over 330 individuals or groups to the microphone. In fact, at a November Stockton Unified Board meeting some district represen-tatives had argued for more flexibility. We did not hear that anymore.

The majority of those we heard in Sac-ramento were superintendents of public schools or their representatives, all making a public commitment to ensuring that the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) monies are used faithfully. Governor Jerry Brown made a surprise appearance and spoke for over ten minutes in his common sense, down-to-earth way, urging to embrace this challenge. Some did, as Dolores Huerta, sitting next to SUSD

sole representative: board member Gloria Allen. Allen echoed the commitment to use funding as LCFF intends.

But Stockton, true to its character, had other, unofficial representatives. Fathers and Families of San Joaquin (FFSJ) sent a diverse group of 45 committed people, from kids to elders, veterans to farm workers, students to teachers, kids to parents, staff to neighbors, all bringing a clear message to the State Capitol: “We ride busses for youth justice!” “Where are we from? -- Stockton! What do we want? Money! Who is it for? Our children!”

When we hopped off the bus, Channel 13 was there, and later

Grandes cosas han pasado en un au-tobús. Yo nací el año en el que Rosa

Parks se negó a dar su asiento, desatando el Boicot de Montgomery, dando nueva vida al Movimiento por los Derechos Civiles.

Hace poco fui parte de un diferente grupo de entusiastas viajeros en autobús rumbo a Sacramento. Arribando el jueves 16 de enero también queríamos cambiar las cosas. Tam-bién creemos que los derechos civiles están to-

continúa a la vueltacontinued on next page

Mensaje para el Directorio

Escolar Estatal

stockton youth at the January 16, 2014, LPac rally in sacramento. Juventud estock-toniana en la manifestación LPac del 16 de enero, 2014, en sacramento.

6 Joaquín fEbruary 2014

dónde somos? —Stockton! ¿Qué queremos? ¡Dinero! ¿Para quién? ¡Nuestros niños!”

Cuando descendimos del bus el Canal 13 es-taba allí, y más tarde televisó al grupo coreando y a nuestros jóvenes hablando a nombre de todos.

Poco más tarde, quince de nosotros ingre-samos a los salones del Directorio Estatal de

Educación. Nos abrió paso una muy solícita mujer; otra nos ofreció intérpre-tes y una tercera vigilaba el reloj. Éramos número 140 a 150 en una serie de oradores que se extendió por 7 horas. No obstante parecía que nuestros es-tudiantes no tenían voz —aunque muchos hablaron

por ellos— brillaba su ausencia. La excepción fue un destacado joven de Visalia, quien creció en una familia hispanoparlante.

Para entonces los miembros del Directorio almorzaban, pero prestaron toda su atención a nuestro grupo —incluso quien controlaba los minutos nos dio cierta ventaja. Al final, quince de nosotros hablamos —incluyendo uno que se pasó entre una escuela de continuación y otra, nueve en total, aprendiendo nada. Otro joven describió los retos que presentan la actividad pandillera, drogas, pobreza, padres que no hablan inglés, y un sistema que no ha sabido tratar la cruda realidad que los estudiantes en-frentan a diario. Dos madres hispanohablantes hablaron apasionadamente sobre la adversidad que sufren sus hijos autistas.

Yo cerré con una breve declaración: He visto demasiados jóvenes en la calle; he visi-tado demasiados en la cárcel o en la correc-cional; he enterrado demasiados.

El mensaje de la coordinadora de organi-zación juvenil de FFSJ, Alejandra Gutiérrez, resume lo que queríamos compartir en nuestro viaje: “La LCFF es una gran victoria, nos ofrece la esperanza de poder garantizar que nuestros niños y jóvenes tengan los recursos y respaldo necesarios para alcanzar su total desarrollo, y alcanzar sus sueños.”

Sammy Núñez, fundador y líder de FFSJ, elaboró: “LCFF es la mayor victoria para ga-rantizar igualdad educativa después de Brown vs Directorio Escolar pero debemos, como comunidad, mantenernos alertas para que este dinero se aplique con el espíritu de la ley, que es ayudar a nuestros estudiantes más vulnerables.

Si debemos mantenernos alerta. La cam-paña recién comienza. Pero no lo llamaré una “batalla” porque confío en que los distritos escolares de nuestro condado —Stockton Uni-ficado en particular— encabezarán el esfuerzo para que estos fondos lleguen a sus destina-tarios: nuestros niños en más alto riesgo.

E D U C A T I o N • E D U C A C I Ó N

Dean McFallsstockton, ca

broadcasted the group chanting and our youth speaking on behalf of everyone.

Shortly after, fifteen of us entered the chambers of the State Board of Education. We were ushered forward by a very kind woman; another offered translation, and a third watched the time. We were numbers 140 through 150 in a series of speakers lasting 7 hours. Yet, it seemed that our students do not even have a voice —while many spoke for them— they were absent. The exception was a highly successful young man from Visalia, who grew up in a Spanish-speaking home.

By then Board members were having lunch, but gave full attention to our group —even the timer gave us some slack. In all, fifteen of us spoke —including one who had been shuffled from one continuation school to another, attending nine in all, learning noth-ing. Other youth recounted challenges of gang activity, drugs, poverty, parents who could not speak English, and a system that has not coped well with the harsh realities students face daily. Two Spanish-speaking mothers spoke with passion about the hardship their autistic children face.

I concluded with a very brief statement: I have seen too many youth on the street; I’ve visited too many in jail or juvenile hall; I have buried too many.

FFSJ’s Youth Organizer Coordinator Alejandra Gutierrez’s message sums up what we travelled to share: “LCFF is a remarkable victory, it gives us the hope that we can ensure that our children and youth have the resources and support necessary to live up to their full potential, and live out their dreams.”

Sammy Nuñez, FFSJ founder and leader, took it farther: “LCFF is the greatest victory in ensuring educational equity since Brown v. Board of Education, but we, as a community, need to be vigilant that this money is spent in the spirit of the legislation: to help our most vulnerable students.”

Yes, we must be vigilant. The campaign is just beginning. But I won’t call it a “battle”, because I’m confident that the school districts of our county —in special Stockton Unified— will take the lead to guarantee that these restricted funds make it to their destination: our most at-risk children.

sus siglas en inglés) envió un diverso grupo de comprometidos individuos, de chicos a grandes, veteranos a campesinos, estudiantes a maestros, personal a vecinos, todos con un claro mensaje para el Capitolio Estatal: “¡En autobús por justicia a la juventud!” “¡¿De

Mensaje al Directorio Estatalviene de la vuelta

Message to the State Boardcontinued from previous page

fEbruary 2014 Joaquín 7

Positive signs of recent economic improve-ment in the San Joaquin region are starting to emerge. As our communities stabilize, its future economic development should include a discussion on bikes.

Yes, I’m talking about bicycles. 2014 is shaping up to be a big year for new policies, ideas and attitudes in Stockton; applying these ideas to our local transportation network is a necessity. The goal of many local policy makers is retaining the region’s youth, par-ticularly those with a college education and well developed employment skills. Reaching that goal is dependent on a whole array of fac-tors including the viability of Stockton’s local transportation network and acknowledging that a growing segment of the Millennium and Generation X generations prefer communities with well-developed bike systems.

According to a recent report published by the group People Powered Movement (PPM,) “The average young person is driving less and biking and taking public transit more.” Car ridership among Millennials is down 23 percent while transit ridership has increased by over 40 percent, and biking as a viable form of transportation is up over 24 percent. “For a rising generation of workers, who’ve grown up amid the urban rebound, traffic jams and office parks are the last places they want to spend time. That’s why companies that rely on young talent are increasingly seeking offices in central cities with good bike facilities,” read the report.

Currently, Stockton lacks a comprehensive bike network. Even though 13 percent local commuters travel 10 minutes or less —in a city mostly flat and with a relatively mild Mediterranean climate— less than 1 percent (about 700 people) regularly bike to work (Stockton Master Bikeway Plan, 2007). A more connected system with improved infra-structure would do wonders for encouraging more people to make the simple switch from four wheels to two.

Trading in the car for the occasional bike trip also does wonders not only for the indi-vidual (think improved health and less money spent on gas), but for the local economy as well. When employees who commute by bike are healthier, small businesses spend less money on healthcare costs, it relieves ve-hicle congestion from the street system, allow more people to be out and about at one time, to shop locally —ten bikes can fit in a single car parking space, bringing fully 50 cents more retail revenue per hour per square foot than a single car would. This

Creando economía, dos ruedas a la vez

Building business, two-wheels at a timeE N v I R o N m E N T • m E d I o a m b I E n t E

Poco a poco se está viendo un mejora-

miento económico en la región de San Joaquín. A medida que se estabilizan nuestras comunidades, el futuro desarrollo econó-mico debe incluir un deba-te acerca de las bicicletas.

Sí. Bicicletas. El 2014 se perfila como un año para

grandes y nuevas políticas, ideas y actitudes en Stockton; aplicando estas ideas a nuestro sis-tema de transporte es una necesidad. La meta de muchas autoridades es retener a la juventud de la región, particularmente aquellos con una educación superior y una buena capacitación laboral. Esa meta depende de una variedad de factores que incluyen la viabilidad del sistema de transporte de Stockton y reconocer que un creciente número de miembros de las genera-

is in addition to improving local air quality.This year, Stockton has the opportunity to

work toward improving the connectivity of its bikeway system. The City is looking to apply for grant funding to update its comprehensive bikeway plan and will be looking for citizen input. If you’d like to get involved, the San Joaquin Bike Coalition is a great starting place to learn more about how to do just that. Please contact us at [email protected]

ciones X y del Milenio prefieren comunidades con sistemas cicloviales bien planeados.

Según un reciente informe publicado por el grupo People Powered Movement (Movi-miento de Impulso Popular, “el joven promedio maneja menos, anda más en bicicleta o en locomoción colectiva.” Entre los Milenio, el traslado en automóvil ha decrecido en un 23 por ciento mientras que el traslado en trans-porte colectivo ha subido a más de un 40 por ciento, y el uso de la bicicleta ha aumentado a un 24 por ciento. “Para una creciente gene-ración de trabajadores que han crecido en el medio de una revitalización urbana, los embo-tellamientos de tráfico y complejos de oficinas son lo último que quieren experimentar. Esta es la razón por la que compañías que dependen del talento joven cada vez más buscan estable-cerse en ciudades centrales con buen sistema ciclovial,” cita el informe.

En la actualidad, Stockton carece de una buena red para bicicletas. Aun cuando el 13 por ciento de quienes se trasladan dentro de Stockton —una ciudad plana y con un benig-no clima mediterráneo— viajan 10 minutos o menos, menos de un 1 por ciento (cerca de 700 personas) van a trabajar en bicicleta (Plan Maestro de Ciclovías de Stockton, 2007). Un sistema de más conectividad y una mejor infraestructura podría motivar a una mayor población a cambiar las cuatro ruedas por dos.

Cambiar el coche por un viaje ocasional en bicicleta no solo hace maravillas para el individuo (mejor salud y menos gasto en gasolina) sino también en la economía. Los empleados que van a trabajar en bicicleta son más sanos por lo que la pequeña empresa gasta menos en atención médica, se está aliviando la congestión vehicular en el sistema vial, permitiendo que más gente ande haciendo compras al mismo tiempo en su localidad —se pueden estacionar diez bicicletas en un espacio para un auto, aumentando en 50¢ el ingreso por hora por pie cuadrado del comercio en comparación al coche. Esto además de mejorar la calidad del aire.

Este año Stockton tiene la oportunidad de progresar en la conectividad de su sistema

ciclista. El Ayuntamiento espera postular a una subvención de fondos para

actualizar su plan general de ciclovías y solicitará la opinión del público. Si desea participar, la Coalición Ciclista de San Joaquín es un buen lugar para informarse cómo hacerlo. Comu-

níquese con nosotros a [email protected]

Kristine Williamsvalley springs,ca

8 Joaquín fEbruary 2014

STUDENTS’ voICES • voCES ESTUDIANTILES

The Brighter Side

My Journeyto Successdominique valle, Livermore, ca

They say you must walk through fog to appreciate and understand the impor-

tance and value of light. My journey through high school made me realize what this saying meant. Many people think that one’s high school years the best years of our life, but in my case it was a roller coaster from hell; yet, I faced downfall after downfall.

It all started my freshman year at West High in Tracy when I got kicked out for fight-ing. My punishment was to be sent to a second opportunity school to redeem myself. Willow was known to be the school where they put all the “bad kids” when they got kicked out of their own district schools. Fourth graders, eight graders, and high school students all go to Wil-low and no one is allowed to wear any colors, just black, white, or grey to prevent gang fights.

After a month there, I faced a second downfall when I was expelled for being absent more than three days, the limit for absences allowed at the facility. As a consequence I was sent to Community School, filled with kids who are looked upon as lowlifes.

While attending Community, the blind-ness in suffered began to disappear, and I felt like I didn’t belong there, that I wasn’t being challenged, so I decided to take action by pleading the Tracy Unified School District to give me one last opportunity to change. I was blessed with the opportunity attend George and Evelyn Stein High School. There I found myself again, the girl before my teen-age years and uncertainty that kicked in, the one who was on the honor roll and made her family proud, instead of making them cry with disappointment.

Now, the dream of graduation became a reality and the urge to drop out no longer dominated my mind; I had finally changed. The next thing I knew, I was standing on stage, speaking on behalf of my class as Valedicto-rian. I had graduated from high school and a new dream was born, to graduate from college with a degree in nursing.

I know that these dark days will always haunt me, but I will remind myself that I survived it, and that made me stronger as an individual. I will remember that dark times only last for a bit and that will eventually make the light brighter.

Dicen que uno debe caminar por la bruma para ver la importancia y valor

de la luz. Mi peregrinaje por la secundaria me mostró cuán cierto es. Mucha gente cree que sus años en la prepa son los mejores que vive uno, pero los míos fueron un viaje del infierno, un trancazo tras otro.

Todo comenzó en mi primer año de se-cundaria en West High de Tracy, de donde fui expulsada por riñas. Mi castigo fue ser enviada a una escuela “de segunda oportunidad” donde corregirme. Willow tenía fama de ser donde iban a parar todos los malosos expulsados de sus respectivos distritos escolares. Estudiantes de cuarto, octavo grado, de secundaria, todos van a Willow y, para evitar riñas pandilleras, no se les permite vestir color, solo blanco, negro o gris.

Luego de un mes allí me di mi segundo en-contrón cuando fui expulsada por ausentarme más de tres días —el límite que se permitía en esa institución. Como resultado fui remitida a la Escuela Comunitaria, llena de chicos a quienes se les considera indeseables.

Mientras asistía a la Comunitaria, la ceguera en la que vivía comenzó a disiparse y empecé a sentir que yo no era de ese lugar, que ahí no se esperaba nada de mí, por lo que decidí hacer algo y le rogué al Distrito Escolar Unificado de Tracy que me dieran una última oportunidad para cambiar. Fui bendecida con la posibilidad de asistir a la Secundaria Geor-ge and Evelyn Stein. Allí me reencontré con esa niña preadolescente, esa de antes que me llenara de incertidumbre, esa que estaba en la lista de honor y que enorgullecía a su familia en vez de hacerles llorar desilusionados.

Ahora, el sueño de la graduación se con-vertía en realidad y la gana de dejar los estu-dios ya no dominaba mis pensamientos; por fin había cambiado. Repentinamente me encontré sobre el escenario, hablando a nombre de mis compañeros como la Primera de la Promoción. Me había graduado de la secundaria y nacía un nuevo sueño, graduarme con un título universitario en enfermería.

Sé que aquellos negros días me penarán de por vida pero me recordarán que sobreviví, y que me hicieron una persona más fuerte. Recordaré que la oscuridad solo dura un poco y que, eventualmente, hace que la luz luzca más brillante.

El Lado Bueno

Peregrinaje al triunfo

fEbruary 2014 Joaquín 9

m o N E y • E C o N o m Í A

When you are no longer youI leaned over the counter, and the smell

of a freshly brewed vanilla latte wafted through the air. I was too busy chatting with two other girls to notice the stern look of disap-proval fall over the cashier’s face.

“Do you have another card?” “Huh?” “Wait, what?” I whipped my head

over. “What did you say?”“Do you have another card? This one isn’t

working.”I felt my cheeks begin to flush. I knew I

didn’t have hundreds of dollars in my account, but I surely had enough to cover my afternoon pick-me-up. I mumbled a weak, “I don’t under-stand,” while rummaging through my wallet. “Here, try this.” I triumphantly handed her my favorite credit card. I knew this one had plenty of credit on it.

She swiped my card several times before heaving a heavy sigh. “Look, I’m sorry, but this one has been declined too.”

Can you imagine yourself in my shoes? Good. Then, I’ve done my job. I’ve sold you a story you can personalize and make your own. I’ve scared you. The thought of being embarrassed in front of your friends - or worse yet, in front of your date - paralyzes you with fear. Now, you’re ready for the pitch.

Are you worried this scenario might happen to you? Do you fear someone might steal your identity? Do you shred all of your mail? Do you have a different password for every account you use? For only $14.99/month I can give you the peace of mind of knowing your identity is safe. {Insert company name here} will monitor your credit and stop all potential fraud. But wait! There’s more! If you act right now, we’ll throw in this complimentary credit report (you just pay this insanely high “minor” shipping and handling fee! He-he!)Sound familiar? These “credit monitor-

ing” companies are all a giant scheme to have you part with your hard earned money each month. I can’t really call them a “scam” —they DO lock up your credit, after all. Only, they’ll charge you an exorbitant amount of money to do so. Charges, that after the initial credit freezes, are almost certainly pure profit.

However, why pay a company to do some-thing that you can do yourself? You can cut out the middle-man and freeze your reports

yourself. And the best part? You’ll only

have to pay a small, one-time fee. No more shelling out cash month after month!

What is a credit freeze? It simply locks down your credit. You (or anyone who at-tempts to steal your identity) will not be allowed to take out any credit in your name without calling the appropriate credit agency and giving them the pin number.

There are three major credit reporting agencies: Equifax, Experian and Trans Union. You can simply visit the website to each, indi-vidual reporting agency and request a credit freeze on your account. You’ll be given a pin and a number to call in the event that you need to temporarily lift the freeze in order to open your credit if you’re buying something or need your credit made available for any reason. There may be a small fee associated with freezing your credit. If you are a senior citizen or a victim of previous identity theft, you may even be allowed to freeze your credit free. Simply contact each agency to find out more.

Now, enjoy the peace of mind that comes with locking up your credit and enjoy a nice, af-ternoon latte with the money you’ve saved

Me incline sobre el mesón y el aroma de café con leche y vainilla se esparció a mi alrededor. Estaba demasiado ocupada conversando

con otras dos chicas como para notar cómo la cara de la cajera se tornaba seria y reprobatoria.

“¿No tendrá otra tarjeta?”“¿Ah? Espere” me volteé ”¿Cómo dice?”“Si tiene otra tarjeta, esta no sirve.”Sentí que mis mejillas se enrojecían. Sabía que no contaba con centenares

de dólares en mi cuenta pero de seguro que había suficiente para cubrir mi revitalizador de la tarde. Murmuré un imperceptible “No sé qué pasó” mien-tras buscaba en mi bolsa. “Aquí. Pruebe con esta,” y le entregue triunfalmen-te mi tarjeta predilecta. Sabía que en esta tenía todo el crédito del mu ndo.

Cuando Ud. es Otro

Hollyandrade blairWest Hillscomm. collegeLemoore, ca

Pasó la tarjeta varias veces por el lector de cinta hasta dar un pesado sus-piro. “Mire, lo siento, pero esta también ha sido rechazada.”

¿Pueden imaginarse en mis za-patos? Bien. Entonces lo he hecho bien y les he entregado una historia con la que podrían identificarse. Les he asustado. La sola idea de ser humillado en frente de sus amigos o, peor aún, de su pretendiente, les paraliza de miedo. Ahora, viene

el reclame.¿Le preocupa que le pase algo así a usted? ¿Teme a que alguien le robe su identidad? ¿Tritura usted su correo? ¿Tiene usted una contraseña diferente para cada una de sus cuentas? Por solo $14.99 mensuales le podemos ofrecer el alivio de saber que su identidad está segura. {Ingrese nombre de la compañía en este espacio} vigilará su crédito y detendrá cualquier posible fraude ¡Pero espere! ¡Eso no es todo! Si ordena YA, le ofrecemos un informe de crédito de cortesía (¡usted solo paga un ridículamen-te alto “pequeño” importe por manejo y envío!... Ja, ja)

¿Suena conocido? Estas compañías “vigila-crédito” no son sino un gran cuento para sacarle una tajada mensual a ese dinero que tanto le cuesta ganar.

Equifax: https://www.freeze.equifax.com/freeze/jsp/sff_PersonalIdInfo.jspExperian: http://www.experian.com/consumer/security_freeze.htmlTrans Union: http://www.transunion.com/personal-credit/credit-disputes/credit-freezes.page

continúa a la vuelta

10 Joaquín fEbruary 2014

Es una gran satisfac-ción regalar algo a nues-tros hijos. Aquí le doy algunos datos a considerar pensando en la próxima generación.¿Está preparado económicamente para su futuro?

Antes de considerar regalos a sus hijos, elimine

todas las cargas que pueda crear, sobre todo, trabaje en ser autosuficiente antes de ayudar a hijos o nietos. Analice sus planes de finanzas para cerciorarse que ahorró suficiente para su jubilación y que cuenta con un plan definitivo de vivienda y atención médica. Esto evita que sus hijos deban preocuparse por usted al tiempo que tratan de criar a su familia. Después, si deciden vivir todos juntos, usted puede contribuir con su dinero de retiro a la casa en lugar de ser una carga.

m o N E y • E C o N o m Í A

Preparing for the next generationAbra cuentas de ahorro de estudios

Con cada generación se incrementa la necesidad de contar con más estudios. Abra una cuenta de ahorro universitario Sección 529 para sus hijos —esto se puede con un asesor de finanzas y darle garantías tributarias que le podrá explicar su preparador de impuestos. Si sus hijos ya son mayores y viven sin usted de-bería considerar abrirla para sus nietos, porque así ayuda a que sus hijos ocupen sus recursos monetarios en criar a sus propios niños.

El factor más importante en una cuenta de ahorro universitario es empezarla lo más tem-prano posible. Cualquier comienzo es bueno: si puede ahorrar solo $20 mensuales, empiece por eso hasta que pueda dar más.Separe dinero para ocasiones especiales

¿Le gustaría pagar por un hermoso ca-samiento para sus hijas o ayudarles con el enganche en una casa nueva? Deje de gastar en pequeños regalos de cumpleaños y festivos y vaya ahorrando un poquito cada mes preparán-dose para grandes regalos en el futuro. Pídales a sus parientes que compren menos regalos y que contribuyan esos dineros a las cuentas de ahorro de sus hijos y así aumenten su balance.Enseñe a sus hijos a saber manejar su dinero

Analice bien como maneja sus finanzas. Si está siempre atrasado o demasiado endeudado ¡Busque ayuda! Hay clases disponibles que le enseñan cómo manejar sus cuentas y reparar sus errores. Una que me ayudó a mi es el curso de Dave Ramsey, disponible en inglés y español. Este combina sólidos principios económicos con la fe.

La clave está en moverse rápido. Si sus niños le ven esmerarse en corregir errores, pueden aprender a evitar esos mismos errores en sus propias vidas. Mientras contemos con más herramientas, más podremos entregar a la próxima generación.

so many small gifts for birthdays and holidays and set aside a little money each month to prepare for large gifts in the future. Some ask relatives to buy fewer gifts and contribute money toward their children’s savings ac-counts to increase their balance.Teach your children how to handle money properly

Take a good look at the way you handle your finances. If you are always behind or too much in debt, get help! There are classes available to learn how to handle finances and undo mistakes. One that helped me was Dave Ramsey’s course, available in English and Spanish. His approach combines sound financial principles with faith.

The key is to move fast. If your children see you work hard to fix mistakes, they can learn to avoid those mistakes in their own lives. The more tools we master, the more we can pass on to the next generation..

Preparándose para la próxima

generaciónIt’s a great feeling to pass on gifts to our

children. Here are some items to consider with the next generation in mind.Are you financially set up for your future?

Before considering gifts to children, eliminate any burdens you can create. above all, work toward being self-sufficient before helping children or grandchildren. Review financial plans to ensure you saved enough for your retirement and have a definite plan in place for adequate housing and healthcare. This avoids having our children take care of us while trying to raise a family. Then, if they chose to live all together, you can contribute to the household with your retirement money rather than creating a hardship.Set up college savings accounts

With each generation, the need for ad-ditional education increases. Set up a Section 529 college savings account for your children —this can be opened with a financial advisor and have tax benefits that a tax preparer can explain. If your children are grown and out of the house, you should consider setting up these accounts for your grandchildren, for it also helps your own children focus on the expense of raising their kids.

The most important factor for a college savings account is to start as early as possible. Anything is good to start: if you can afford only $20 per month, start with that until you can afford more.Set aside money for special events

Would you love to pay for a beautiful wedding for your children or help them with a down payment on a new home? Stop buying

No se les puede calificar, totalmente, de fraude —después de todo, SÍ congelan su crédito. Lo malo es que cobran un precio exorbitante para hacerlo. Los cobros —después del congela-miento inicial— de seguro son por nada.

Pero ¿Por qué pagarle a una compañía por algo que puede hacer usted mismo? Usted puede evitar intermediarios y congelar usted mismo sus informes ¿La mejor parte? No so-lamente se paga una pequeña tarifa inicial ¡y

una sola vez! ¡Nada de mensualidades!Pero ¿Qué es un congelamiento de crédito?

Simplemente le pone llave a su crédito. Ni a us-ted (o cualquiera que intente hacerse pasar por usted) se le permite sacar crédito a su nombre sin consultar a las agencias correspondientes y proporcionarles el número de clave.

Hay tres principales agencias de reporte crediticio: Equifax, Experian y Trans Union. Puede simplemente visitar el sitio virtual de cada una e individualmente solicitar que le congelen su crédito. Se le dará un número de

clave y un teléfono a llamar en caso que quiera “descongelar” cuando quiera abrir una línea de crédito al comprar algo o por cualquier otra razón. Puede se le cobre un pequeño monto por ese servicio pero, si usted es de la tercera edad o ha sido víctima de robo de identidad, es posible que no deba pagar. Para averiguarlo llame a cada agencia.

Ahora regocíjese en la tranquilidad de saber que su crédito estará protegido y, por la tarde, deléitese con un café con leche con el dinero que se habrá ahorrado.

staci rocharipon, ca

Cuando Ud es otroviene de la vuelta

fEbruary 2014 Joaquín 11

reserve. Governor Jerry Brown is certain to be at the top of the ticket for Califor-nia Democrats in the 2014 elections and will undoubt-edly campaign for a larger reserve. Meanwhile, state legislators vying to retain Democratic supermajori-ties in the Assembly and Senate will strive to restore

and create funding for programs and services important to their districts. Ultimately, leg-islators will likely cede to Governor Brown’s veto power and popularity and will strike a compromise on the Rainy Day Fund, that is, if drought and federal cuts do not decimate the reserve altogether

You can summarize Governor Jerry Brown’s 2014 vision for California in one word—prudence. It was the theme of his State of the State Address and the thesis for his proposed budget and Rainy Day Fund re-serve. However, prudence and the proposed $1.6 billion Rainy Day Fund will face a year of extraordinary challenges.

To start, California is experiencing its driest recorded year in its history. This State of Emergency, declared by the Governor last month, has and will continue to impact the state’s economic prospects. In the near-term, plans to promote conservation, clean up groundwater, develop more water storage, and fund local water projects will be costly, yet necessary, investments.

In the long-term, the effects of extended drought will strain our economy by affecting one of our most important sectors: agricul-ture. As the number one state in agricul-tural production a lot hangs in the balance for California’s economy when it comes to water. The latest Department of Water Resources measurements show the state’s snowpack at 12% of normal. If drought persists through the spring, the anemic Sierra snowpack will yield very little to help fill our creeks, rivers, and reservoirs that are so crucial to keeping farmland production afloat. If the state’s agricultural production atrophies, the loss to the economy will put this year’s Rainy Day Fund at risk, and perhaps even the prospects of future reserves in question.

However, the Rainy Day Fund is not only at odds with Mother Nature, but with national and state politics as well. In January, Repub-lican filibusters in the U.S. Senate stopped the passage of two separate bills for the extension of unemployment insurance benefits. One bill proposed an 11-month extension, the other a 3-month extension. Debates are ongoing and, if any compromise is reached, an extension is unlikely to last through the 2014-15 fiscal year. This means that over 200,000 Californians that lost their benefits in December of 2013 will have to continue to survive without unem-ployment insurance. Because revenues fund the reserve and people need to spend money for the state to collect revenues, the plight of California’s unemployed will undermine the potential of a state reserve.

Last but not least, state politics will spur negotiations over the requisite size of the

L E g I S L A T U R E • L E g I S L A T U R A

Will the rainy day fund survive 2014?

Max Vargasstockton, ca

La visión de California para el goberna-dor Brown se podría resumir en una palabra —prudencia. Fue el tema de su discurso Es-tado del Estado, como también la tesis de su propuesta presupuestal y su Fondo de Reserva para Tiempos Malos. Sin embargo, la pruden-cia y este propuesto Fondo de $1,6 mil millones enfrentan un año de extraordinarios retos.

Para empezar, California experimenta el año más seco en su historia. Este Estado de Emergencia —declarado por el Gobernador el mes pasado— afecta y seguirá afectando las perspectivas económicas del estado. En el cor-to plazo, planes para promover conservación, limpieza de aguas subterráneas, desarrollo de más almacenamiento de agua, y la finan-ciación de proyectos hídricos conllevarán un

¿Sobrevivirá el 2014 el Fondo de Reserva?

importante pero necesario costo.En el largo plazo, los efectos de una

larga sequía resentirá nuestra economía con el efecto que tendrá en uno de nuestros

sectores más importantes: la agricultura. Como estado líder en la producción agrícola, el papel que juega el agua en la economía es ma-yor. Las evaluaciones más recientes entregadas por el Departamento de Recursos Hídricos revelan que la masa de nieve se encuentra al 12% de lo normal. Si la sequía persiste a tra-vés de la primavera, poco es lo que la Sierra podrá aportar para llenar nuestros arroyos, ríos y represas, tan vitales en mantener a flote la producción agrícola. Si la producción agrícola del estado se atrofia, las pérdidas en la economía no solo pondrán al Fondo de Re-serva de este año en riesgo, sino también cues-tionarán los prospectos de futuras reservas.

No obstante, el Fondo de Reserva no solo tiene problemas con la Madre Naturaleza, sino también con la política estatal y nacional. En enero, tácticas obstruccionistas republica-nas en el Senado de los EEUU detuvieron la aprobación de dos proyectos de ley que expenderían los beneficios del seguro de des-empleo. Una ley proponía una extensión de 11 meses, la otra tres. Los debates continúan y, de llegarse a un acuerdo, cualquier extensión no para del año fiscal 2014-15. Esto significa que sobre 200 mil californianos que perdieron sus beneficios en diciembre del 2013 tendrán que seguir sobreviviendo sin seguro de desempleo. Dado que la reserva se alimenta de ingresos y la gente debe gastar dinero para que el estado recolecte ingresos, la crisis de los desemplea-dos en California también afecta dicha reserva.

Por último y no por eso menos importante, la política estatal se enfrascará en debates sobre el tamaño de la reserva. Es seguro que el gobernador Brown es el puntero en la nominación demócrata para California en la elecciones del 2014 y este, indudablemente, trabajará por una mayor reserva. En el ínterin, los legisladores estatales que intenten mante-ner las supermayorías demócratas en la Asam-blea y el Senado se esmerarán por restaurar y crear financiación para programas y servicios de importancia para sus distritos. Al final es muy posible que los legisladores se rindan ante el poder de veto y popularidad del Gobernador, y se contentarán con llegar a un acuerdo en el Fondo de Reserva. Eso, si es que la sequía o los recortes federales no lo acaban antes.

12 Joaquín fEbruary 2014

s t o c k t o n u n I f I E d s c H o o L d I s t r I c t

susd launches Local control accountability PlanSUSD has launched development of its

spending plan to improve academic achievement for its students over the next eight years. As part of Governor Brown’s new spending formula for state funds, SUSD will be given some flexibility to focus on programs that best serve low income, English language learner and foster youth.

This is an opportunity for the District to fund a significant program to boost student achievement starting in 2014-15. SUSD is in-cluding parents and the community in its efforts to develop as strong a plan as possible for the students —an advisory committee, comprised of parents, students, teachers, union represen-tatives, administrators, and others has been na-med and will be breaking into smaller groups to discuss the district’s priorities for next year.

Under the Governor’s plan, every district must develop a Local Control Accountability Plan (LCAP) that addresses how the state funding will be used over the next eight years. SUSD’s plan will first include programs for the next one to two years and then a longer term plan.

The District is expected to implement a proven program to help students, and it is already studying the significant success of the SIG schools, traditionally low performing schools that made bigger gains than the other schools last year. Funded by a special grant, those schools have more teacher collaboration and longer school days for students, even offer Saturday school.

SUSD held a public meeting in September announcing the plan and Superintendent Steve Lower has sent letters to all parents describing the process. There will be public outreach this spring and the Board of Education will receive a recommendation for the plan prior to budget consideration in May and June. The Board will vote on the plan when it approves its spending budget for next year.

The SUSD Parent DAC and DELAC will

El SUSD ha dado inicio al desarrollo de un plan de gastos para elevar el

rendimiento académico de sus estudiantes por los próximos ocho años. Como parte de la nueva fórmula estatal para gastos del Go-bernador Brown, al SUSD se le ha otorgado cierta flexibilidad para enfocarse en aquellos programas con mayor efecto en la juventud de bajos ingresos, de inglés como segunda lengua, o en custodia temporal.

Esta es una oportunidad para que el Dis-trito financie este importante programa para mejorar el nivel académico empezando este 2014-15. El SUSD ha incluido padres y vecinos en sus esfuerzos por desarrollar el plan más robusto posible para sus estudiantes —se ha

nombrado un comité asesor compuesto de padres, estudiantes, maestros, representantes sindicales, administradores y otros, el que se dividirá en pequeños grupos para estudiar las prioridades del distrito para el año venidero.

Bajo el plan del Gobernador, cada dis-trito debe desarrollar un Plan de Control y Responsabilidad Local (LPAC, por sus siglas en inglés) donde se cubra el destino de esos fondos estatales por los próximos ocho años. El plan del SUSD incluirá, en primer lugar, programas para los próximos uno o dos años, y luego un plan de más largo plazo.

Se espera que el Distrito implemente un programa probo en ayudar al estudiante, y se encuentra ya analizando el importante éxito que han tenido las escuelas bajo Subvención de Mejoramiento Escolar (SIG, por sus siglas en inglés), entidades de tradicionalmente bajo rendimiento pero que el pasado año han expe-rimentado mayor avance que otras escuelas. Financiadas por una subvención especial, estas escuelas cuentan con más colaboración entre maestros y más largas sesiones académicas para sus estudiantes, incluso ofrecen escuela en sábado.

En septiembre el SUSD realizó una audiencia abierta para anunciar el plan y el superintendente Steve Lowder ha enviado cartas a todos los padres detallando el pro-ceso. En esta primavera se llevará a cabo una campaña en la comunidad y el Directorio Escolar recibirá la recomendación de un plan —previo a considerarse el presupuesto en mayo y junio. El Directorio votará sobre este plan cuando apruebe el presupuesto de gastos para el próximo año.

El comité de padres que asesora al Distrito (DAC, por sus siglas en inglés) y DELAC, que lo asesora en el tema del inglés como segunda lengua, coordinará las reuniones del Distrito con los padres en cada zona. Estas presen-taciones se llevarán a cabo en un número de audiencias abiertas y se programará por lo menos un foro comunitario. El Distrito ofrece información sobre el LPAC en una página especial en su sitio virtual donde se incluye una encuesta para padres y la comunidad. Aquellos padres que desean participar en la encuesta y no tienen acceso a un computador pueden hacerlo en la oficina del Distrito en Calle Madison o en computadoras disponi-bles durante las audiencias mencionadas. Se ofrecerá traducción.

Para mayor información, comuníquese con la directora de información pública del SUSD, Dianne Barth al (209) 933-7025.

susd lanza Plan de

responsabilidad y control Local

be coordinating with the district on parent meetings planned for each zone. Presentations will be made at a number of community group meetings and at least one community forum will be scheduled. The District offers informa-tion about the LCAP on a special page on its website that includes a survey for parents and community members. Parents who do not have access to take the survey on a computer can do so at the District’s Madison Street office or at computers that will be provided at the parent meetings. Translations will be provided.

For more information, contact SUSD Communications Director Dianne Barth at 933-7025.

fEbruary 2014 Joaquín 13

More than fifty SUSD parents, from schools throughout the district, participated in the first 2013-2014 Parent Academy

Graduation ceremony at Hong Kingston Elementary School. The par-ents were honored for completing a six-week-long parents-as-educators training program offered by the SUSD’s Parent Empowerment Office, directed by Francisco Ortiz.

Parent Vanessa Elledge said it is important for her to prepare for her son Michael’s teenage years. “I just want to make sure that I’m aware of how to help him with the changes he needs to make,” she said. “Some of the things I know already because I am involved. But I (also) want to help promote parent involvement.”

Parent Involvement Coordinator Kennetha Stevens said the first pro-gram is part of an 18-week training that will help parents better under-stand how to help their students and become leaders in their education.

Attended by graduating parents, their families, SUSD Superinten-dent Steven Lowder, SUSD Board President Kathy Garcia and Board members Gloria Allen and David Varela —along with other school officials— the event highlighted the importance of parent participa-tion in SUSD schools. Four more academies are planned this year with the same goals. There is no charge and translation is available for non English speakers.

To learn more or find out how you can participate, call SUSD Parent Empowerment at 933-7470.

s t o c k t o n u n I f I E d s c H o o L d I s t r I c t

dijo, “algunas de las cosas ya las sé porque participo siempre, pero también quiero ayudar a promover la participación de otros padres.”

La coordinadora de Participación de Padres Kennetha Stevens dijo que el primer programa es parte de una capacitación de 18 semanas que busca que los padres entiendan mejor como ayudar a sus estudiantes y convertirse en líderes en su educación.

Con la asistencia de los padres que se graduaban, sus familias, el superintendente del SUSD, Steven Lowder, de los miembros del Directorio Gloria Allen y David Varela —junto a otras autoridades escolares— este evento destacó la importancia de la participación de padres en las escuelas del SUSD. Se han programado cuatro academias mas para este año con el mismo propósito. No se cobra la asistencia y se ofrece traducción a quienes no hablen inglés.

Para mayor información o saber cómo participar, llame a Capaci-tación de Padres del SUSD al 933-7470.

susd Parents don graduation caps

Padres SUSD visten gorra de graduación

Más de 50 padres del SUSD, de escuelas de todo el distrito, par-ticiparon en la primera ceremonia de graduación 2013-2014

de la Academia para Padres, realizada en la Primaria Hong Kingston. Se distinguió a padres que completaron el programa de capacitación de seis semanas Padres-como-Educadores, ofrecido por la Oficina de Capacitación para Padres, y que dirige Francisco Ortiz.

La madre Vanessa Elledge habló cuán importante es para ella pre-pararse para la adolescencia de su hijo Michael. “Quiero asegurarme y saber qué hacer para ayudarle en los cambios que se le presentarán,”

14 Joaquín fEbruary 2014

I slowly pulled the drawer open; it was heavy and it drug on the wooden base making it seem more like a tug-of-war

than anything else. 78’s. There they were. Those black discs made of shellac resin that protected the sounds of the past from obscurity. Old re-cords. Thick and fragile. I gingerly picked them up one-at-a-time, respectfully sliding each from the brown paper sleeve that guarded the secret of the artist. Dusting each off, I read the names and remembered the sounds that were my childhood, that were my parents’ lives.

My dad was a jazz musician and artist; my mom a historian of the music of her time… both must have been “hip” in their day. There was never a time… ever… that those 78’s would not be playing in our house, except when my pops would be playing the piano or trumpet himself. I could hear my parents talking about the heart, innovation, soul, chosen chords, phrasing of “licks”… about the “history” of the music, the history of the bands, the history.

As I slid a sleeve off… Billie Holiday… “Strange Fruit.” I remember the first time I heard it. I was little. It was a sad song… that’s all I knew. Her voice hurt. Pretty… but hurt.

Years later, when I could start to understand, the scratchy, almost gritty sound was filling the house and I remember saying to my mom how sad her voice sounded… Billie Holiday… “Strange Fruit.” We sat down on the floor in our living room… on the hard, deeply creased, wood floor… and she told me the story. It was not about fruit at all. She picked up the needle when the song finished, and started it again, and again, and again. We listened to the words.

I cried.It is tragic to me how over 60 years, when a

teacher named Abel Meeropol wrote “Strange Fruit” as a poem, and in 1939 when Billie Holi-day sang it, so sad, so full of pain… that things appear to change… but really don’t.

“…With liberty and justice for all…” be-comes haunting when you look at simple facts. Demographics of prisons. Demographics of poverty. Demographics of health. Demographics of dropouts.

Demographics undeniably unacceptable.It is National African-American History

month… some things change… some do not.

Strange Fruit REVISITEDLentamente abrí el cajón; estaba pesado y se

apegó a su base de madera transformán-dose más en un tira y afloja que otra cosa.

78s. Ahí estaban. Esos negros discos de pizarra que protegían a los sonidos del pasado del olvido. Viejos

discos. Gruesos y frágiles. Los tome cuidadosamente, uno a la vez, respetuosamente sacándole de la funda de

papel café que vigilaba el secreto del artista. Despol-vándolos individualmente, leí los nombres y recordé los

sonidos que fueran mi niñez, que fueran las vidas de mis padres.

Mi papá fue un músico de jazz y un artista; mi mamá una historiadora de la música de su tiempo…

ambos deben haber sido “hip” en sus días. No puede haber habido un tiempo… nunca… en el que no se

escucharan esos 78s en mi casa, excepto cuando mis padres tocaban el piano o trompeta ellos mismos. Les podía escuchar hablar del corazón, la innovación, el

alma, ciertos acordes, composición de “licks (series de notas)”… sobre la “historia” de esa música, la historia

de las bandas, la historia.Al sacar la caratula de… Billie Holiday… “Strange

Fruit (Extraña Fruta)” recordé la primera vez que la escuché. Era pequeño. Era una canción triste… era

todo lo que sabía. Su voz era dolorida. Linda pero dolorida.

Años más tarde, cuando ya podía entender, ese so-nido rasposo, casi arenoso llenaba la casa y recuerdo

que comenté a mamá cuan triste sonaba su voz… Billie Holiday… “Strange Fruit”. Nos sentamos en el piso de nuestra sala… en ese duro piso de madera de veta pro-funda… y ella me dijo la historia. No se trataba de una fruta. Levantó la aguja al acabar la canción y la volvió

a poner, y volvió a poner. Escuchamos la letra.Lloré.

Se me hace trágico que hace más de 60 años, cuan-do un maestro llamado Abel Meeropol escribió “Strage

Fruit” como poema, y en 1939 cuando Billie Holiday lo cantó, tan triste, tan llena de dolor… que pareciera

empezaban a cambiar las cosas… pero en realidad no.“…Con libertad y justicia para todos…” queda

dando vueltas cuando vemos ciertos hechos. La demo-grafía en las prisiones. En la pobreza. En la salud. En

el abandono de los estudios.Demografía innegablemente inaceptable.

Es el Mes de la Historia Afroamericana. Algunas cosas cambian. Otras no.

mick fountsmanteca, ca

February: Black History Month

fEbruary 2014 Joaquín 15

Strange Fruit REVISITEDFebruary: Black History Month

16 Joaquín fEbruary 2014

Music was in the air on January 11 at the San Joaquin County High School

Honors Concert for Band, Choir and Orchestra held at Stockton’s Delta College in Atherton Auditorium. More than 240 students from 21 area High Schools representing eight districts took part in this annual event. Students were selected to participate during auditions held last fall; any high school student enrolled in a school-sponsored band, choir or orchestra could participate. Selected were the best in the area to work with guest conductors.

This year’s Concert was dedicated to Dr. Mick Founts, San Joaquin County Superinten-dent of Schools in appreciation for his contin-ued support of the arts. Dr. Founts is retiring in December after 23 years at SJCOE.

This year’s guest conductor for band, Dr. Eric Hammer, teaches at University of the Pacific in Stockton. His engaging teaching style encouraged the students to reach to new heights of musical abilities, highly praised the by the over 1,000 people in attendance.

The 2014 Honor Choir students had the opportunity to study under Dr. Daniel Afonso of CSU Stanislaus. The 108 choir students entertained the audience with their five selec-tions; the choir also received a warm reception for their hard work and devotion. This was the third year that Honor Band and Choir were joined by an Honor Orchestra. The 33 members for 2014 were conducted by Thomas Derthick, director of the Central Valley Youth Symphony; their performance showed the

s a n J o a Q u I n c o u n t y o f f I c E o f E d u c at I o n

Honor musicians shine at concert

Había música en el aire ese 11 de enero en el Concierto para Bandas, Coros y Orques-

tas de Honor de secundarias del Condado San Joaquín, celebrado en el Auditorio Atherton de Delta College. Más de 240 estudiantes de 21 preparatorias, representando ocho distri-tos, tomaron parte en este evento anual. Los estudiantes fueron seleccionados a través de audiciones realizadas el pasado otoño y cual-quiera inscrito en una banda, coro u orquesta de la escuela podía participar. El proceso de audición selecciona a los mejores del área para trabajar con conductores invitados.

El Concierto de este año fue dedicado al Dr. Mick Founts, superintendente de escuelas del Condado San Joaquín en agradecimiento y aprecio por su continuo respaldo a las artes. El Dr. Founts se jubilará en diciembre luego de 37 años en la educación, 23 de ellos en la SJCOE.

El conductor de banda invitado de este año, Dr. Eric Hammer, enseña en la Univer-sidad del Pacífico en Stockton. Su estilo de enseñanza motivó a los estudiantes a llevar su talento musical a nuevos horizontes, reci-biendo logrando una tremenda acogida entre

los más de un millar de asistentes. Los estu-diantes del Coro de Honor del 2014 tuvieron la oportunidad de trabajar bajo el Dr. Daniel Afonso de la Universidad Estatal de California en Stanislaus. Los 108 estudiantes de coro deleitaron a la audiencia con cinco selecciones; el coro recibió también una calurosa recepción por su empeño y entrega. Este fue el tercer año en el que la Banda y Coro de Honor tocó junto a la Orquesta de Honor. Los 33 miem-bros del 2014 fueron conducidos por Thomas Derthick, director de la Sinfónica Juvenil del Valle Central; su actuación mostró emergentes talentos en este grupo.

El momento culminante de la noche: se galardonó a 18 estudiantes con el premio Nelson Zane por cuatro años de participación en Conciertos de Honor —todos en los que les era permitido competir. A dos de estos se les otorgó también la Beca Nelson Zane: en banda, Aditya Gupta, y en coro, Megan Carbiener.

Este concierto anual contó con la asisten-cia de familiares y amigos de todo el valle en lo que ya se ha convertido en uno de los mejores eventos musicales de nuestra área.

Músicos de Honor marcan la nota

growing talents of this group.The highlight of the night: 18 students

were awarded the Nelson Zane four-year award for participation in the Honors Concert for all four years they were eligible. Two of these were also awarded the Nelson Zane scholar-

ship: for Band, Aditya Gupta and for Choir, Megan Carbiener.

Family and friends from throughout the valley attended this annual concert that has become one of the finest student musical events in our area.

fEbruary 2014 Joaquín 17

As a doctoral student, I’m particularly in-

terested in researching the concept of Undermatching. Broadly speaking, “Under-matching” occurs when a highly qualified, high-performing student from a particular demographic (low-income, historically underrepresented) opts

out of applying to selective four-year colleges where they would have most likely gained admission. The benchmark for identifying “highly qualified” and “high performing” is qualified through Grade Point Average (GPA), class rank, test scores, and other traditional academic criteria. Students with this type of academic profile would certainly be recruited and highly sought after by Ivies and top tier private colleges like Stanford and MIT. But, they must first apply. Therein lies the problem.

Undermatching concerns me because of the disproportionate effect it has on minority and low socioeconomic-status students, and seeing the compelling social, financial, and psychological benefits that they forgo when they undermatch at a less selective institu-tion. Tremendous gains they unwittingly cede include renowned research, rigorous curriculum, networking opportunities, career advancement, social mo-bility, enhanced graduation success, financial benefits, and the ability to enga-ge in dialogue with peers who share their intellectual cur iosity and abilities. And, they typically cede a f u l l-ride. The ad-vantages here are hardly tri-vial. The mamá in me wants to k nock on t he i r door and say, “Mija/o, we need to t a l k!”

In addition, under-matching concerns me be-cause its impact extends beyond the individual

Underscoring theissue of Undermatching

Subrayando el tema de la

Disparidad

E D U C A T I o N & I N E q U A L I T y • E D U C A C I Ó N y D E S I g U A L D A D

Como candidata a un doctorado, estoy muy interesada en estudiar el

concepto de “undermatching (subestimación o disparidad de capacidad)” En términos generales, esta disparidad ocurre cuando un estudiante sobresaliente —cualificado y de alto rendimiento— perteneciente a un grupo demográfico en particular (de bajo ingreso, históricamente marginado) se abstiene de pos-tular a universidades de élite donde probable-mente hubiese sido aceptado como alumno. El parámetro para catalogar a un estudiante “cualificado” y “de alto rendimiento” se basa en su promedio de calificaciones, rango entre sus compañeros, notas que obtiene en pruebas y otros medios tradicionales de evaluación. Ciertamente que estudiantes con este tipo de perfil académico no solo serían aceptados sino invitados por las Ivy League y otras universidades privadas del más alto prestigio como Stanford y el MIT. Pero para eso primero deben postular… y ahí es donde está el detalle.

Esta disparidad me preocupa por el desproporcionado efecto que tiene entre estudiantes minoritarios o de bajo nivel so-cioeconómico, como ver todos los beneficios sociales, económicos y sicológicos que pierden cuando se les coloca en una institución menos exigente. Entre las inmensas ventajas que sin darse cuenta dejan ir se incluyen acceso a in-vestigación de renombre, rigurosos planes de estudio, conexiones, avance profesional, subir de nivel social, mejor probabilidad de gradu-ación, beneficios económicos, y la posibilidad de mezclarse con compañeros que comparten similares intereses y conocimiento. Y, general-mente, se pierden un viaje con todo pagado. Las ventajas en esto no son nada despreciables. La mamá en mí quiere ir a tocarles la puerta y decirles “M’ija/o, ¡tenemos que hablar!”

Además, esta disparidad es preocupante porque su impacto se extiende más allá del individuo —con efectos intergeneracionales y a la comunidad en general por su posible papel como posible modelo y orientador.

Sí —para el estudiante promedio, cualqui-er universidad típica es suficiente. Pero estos chicos no son promedio. No solo sobrepasan en desempeño a sus compañeros sino que lo han hecho a pesar de todos los obstáculos y barre-ras que se les anteponen.

– to intergenerational effects and to the greater community via the potential role-modeling and mentorship affect.

Yes – for the average student, a typical university experience is sufficient. However, these kids are not average. Not only are they outperforming their peers, but they have done so at a compounded rate due to the obstacles they’ve overcome along the way. It seems une-thical our society would permit these outliers to filter through the sieve of college admissions.