Israel Settlements en Jerusalen Palestina

-

Upload

danieladanu -

Category

Documents

-

view

217 -

download

0

Transcript of Israel Settlements en Jerusalen Palestina

-

7/28/2019 Israel Settlements en Jerusalen Palestina

1/20

Environment and Planning A 2013, volume 45, pages 497 516

doi:10.1068/a45108

The politics o suburbia: Israels settlement policy and

the production o space in the metropolitan area o

Jerusalem

Marco Allegra

Centro de Investigao e Estudos de Sociologia (CIES), Instituto Superior de Cincias

do Trabalho e da EmpresaInstituto Universitrio de Lisboa (ISCTE-IUL), Avenue das

Foras Armadas, 1646-026 Lisboa (PT), Portugal; e-mail: [email protected]

Received 29 February 2012; in revised form 23 June 2012

Abstract. Israels settlement policy in the West Bank represents a crucial issue in the IsraeliPalestinian confict. Through the examination o a single case studythe planning history

o the Jewish settlement o Maale Adummim, located in the eastern periphery o the

citythe paper addresses the complex nexus between planning and state-building practices;

building on Henri Leebvres theory o space, he oers an account o the role o Israels

settlement policy in the transormation o the material, symbolic, and political landscape

o the metropolitan area o Jerusalem. My main argument is that the observation o the

development o large suburban communities in the metropolitan areaa blind spot both

in media and in academic discourseis crucial or our understanding o the settlement

policy as a whole, and its impact on IsraeliPalestinian relations.

Keywords: Jerusalem, Maale Adummim, Israel, Palestine, planning, Jewish settlements,

Henri Leebvre

Just a few miles east of Jerusalem, along the road to Jericho, in a brown, barren lunar

landscape of enormous boulders and talcum-powder-fine sand, miles of ridges have been

covered with three- and four-story apartment complexes made of glass and shimmering

white stone. The settlement is called Maale Adummim.

Robert Friedman (1992, pages xxivxxv) (1)

1 Producing (state) spaces: Israels settlement policy

As Henri Lefebvre noted, space is at the same time a social product and a tool that individuals

and groups use in framing their relationsas a means of mobilization, production, and

control. For the French philosopher:

[a]ny social existence aspiring or claiming to be real but failing to produce its own

space, would fall to the level of folklore and sooner or later disappear altogether,

thereby losing its identity, its denomination and its feeble degree of reality (Lefebvre,

1991, page 53).

Indeed, statesmen and nationalists of all times would agree with Lefebvre. The vast

literature on state building and nationalism emphasizes the role of the state in creating new

spacesmaterial, administrative, symbolic, etcin order to build and strengthen a common

self-perception of the national community and to advance the goals of determined social

groups (Anderson, 1983; Hobsbawm and Ranger, 1983; Mitchell, 1991; Taylor, 1994). As

Oren Yiftachel (1998) observed, there is an intimate link between planning, the logic of

(1) Multiple transliterations can be found of the name of the settlement. My choice is MaaleAdummim, but I decided to keep the different forms appearing in articles, reports, and other sourcematerial.

-

7/28/2019 Israel Settlements en Jerusalen Palestina

2/20

498 M Allegra

the modern nation-states attempts to control the production of space within its boundaries

(page 399; see also Brenner and Elden, 2009).

The settlement of tens of thousands of Israeli Jews in the territories occupied in 1967

represents an extreme example of the nexus between the production of space and statebuilding, and a major element in the process of transformation of the material, symbolic, and

political landscape of IsraeliPalestinian relations.(2)

Despite its relevance, the literature on Israels settlement policy remains scarce. To be

sure, almost every book and article dealing with the IsraeliPalestinian conflict devotes some

attention to the issue of Jewish settlements; only a limited number of researchers, however,

have so far delved into the specific issue of settlements. After the second half of the 1980s,

academic interest in the topic steadily declined, overshadowed by the emphasis which the

peace process placed on the so-called two-state solution. Since then, the issue of settlements

has been approached almost exclusively from the point of view of conflict resolutionby

considering settlements as a whole as obstacles to peace or detailing territorial proposals for

Israels disengagement from the World Bank and Gaza Strip (see, for example, Reuveny,

2003). Overall, research on the topic remained surprisingly scarce, with an almost total

absence of case studies and an emphasis on the hard-line nationalreligious component of

the settlers world.(3)

The only comprehensive accounts of Israels settlement policy to date are the volumes by

journalists Gershon Goremberg (2006, covering only the period 196777), Akiva Eldar and

Idith Zertal (2007), and the more scholarly study of settlement policy and decision making by

William Harris (1980) and Peter Demant (1988). Still, as Menachem Klein (2007) notes in his

review of the volume by Eldar and Zertal, these contributions analyze primarily the symbiosis

between the political establishment and its settler agents and not the social dynamic of

a single settlement over time or the variety of social relations and internal interactionsdeveloped in different models of settlement (page 127). With few exceptions (Newman,

1996; Portugali, 1991; Segal and Weizman, 2003; Weizman, 2007), academic output on

Israel settlement policy continues to be characterized by loose theoretical frameworks and

an emphasis on description, rather than interpretation or analysis. Indeed, the main bulk of

knowledge produced about the settlements in the last twenty years derives from the activity

of NGOs devoted to monitoring settlement expansion, such as the Foundation for Middle

East Peace, Peace Now, Bimkom, and BTselem.

(2) For the purposes of this paper the term settlement identifies every locality built by Israel on landoccupied in 1967irrespective of its status in Israeli law. As of 2007, I estimate the number of settlersat around 465 000, of whom 190 000 are in East Jerusalem and 275 000 in the rest of the West Bank(ICBS, 2010, table 2.6; JIIS 2010, table III/14). The reader should remember that it is difficult toestimate the settler populationand in particular in the area of Jerusalemas Israeli figures fromthe Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics (ICBS) do not distinguish between East and West Jerusalem.The figures in tables 1 and 2 are therefore my own best estimates for the end of 2007, based on data

produced by the ICBS, the Jerusalem Institute for Israeli Studies (JIIS), and the NGO BTselem;I chose to consider figures for 2007 as figures for the Palestinian population are available for thesame year. The last figure published by the ICBS (2011) for the number of Jewish residents in theWest BankEast Jerusalem excludedis 311 100 (end of 2010). Recently, an article appeared in theIsraeli newspaperIsrael Hayon (2012) in which the number of settlers in the West Bank in 2011 wasestimated at 722 000, including 300 000 Jews living in East Jerusalemto my best knowledge, aninflated figureand 60 000 students enrolled in educational institutions located beyond the pre-1967

border.(3) See Aran (1986; 1991), Don Yehiya (1994), Friedman (1992), Isaac (1976), Lustick (1988), Newman(1985), Newman and Herman (1992), Ravitzky (1996), Sprinzak (1991). Feiges (2001; 2002; 2009)work offers a relatively rare example of case-study sociological analysis, while other contributionsdeal with the settlers narrative, political attitudes, and place attachment from the point of view of

psychology (for a review see Possick, 2004).

-

7/28/2019 Israel Settlements en Jerusalen Palestina

3/20

The politics of suburbia 499

The aim of this paper is to begin to fill this void by presenting an account of the history

of the Jewish settlement of Maale Adummima suburban community of almost 40 000

residents founded in the periphery of Jerusalem at the end of 1970s. This history, I argue,

is a single but significant episode in Israels settlement policy, and a telling example of itscomplex role in the process of the production of space in a contested region.

The paper is articulated in four main sections. In section 2 I illustrate the history of

Maale Adummim. Building on this account, in section 3 I introduce a more theoretically

oriented discussion, based on Brenner and Eldens (2009) reading of Lefebvre. In sections 4

and 5 I discuss Israels settlement policy in the light of the notions of territory effect, and

the production of territory, respectively.

2 Of brides, dowries, and suburban dreams

After the war of 1967 Levi Eshkol, the Israeli Prime Minister, noted how Israel did covet the

dowry [the conquered land], but not the bride [the Palestinians] (Gordon, 2008, page 29).

This was especially true for the area of Jerusalem, given the citys status as Israels capital,

the contested sovereignty of the eastern neighbourhoods, and the presence of a significant

Palestinian communityboth within and immediately outside the newly expanded city

limits.

In order to bridge the inherent contradiction between territorial and demographic goals,

Israeli governments resorted to the Zionist tradition of territorial settlement. In the mid-

1970s, after the construction of several settlements within Jerusalem municipal borders

(see figure 1), many Israeli politicians looked forward to strengthening Israeli control over

the capital through the development of an outer ring of Jewish settlements (Dumper, 1997,

pages 114119; MERIP, 1977).

The history of Maale Adummim begins in the summer of 1974, when the idea of buildingan industrial park in the eastern periphery of Jerusalem began floating through officialdom

(Goremberg, 2006, pages 297298); in November, the government approved the teams

proposal for the establishment of an industrial area and a workers camp for the employees

on a group of hills located approximately 5 km east of Jerusaleman area belonging to

surrounding Palestinian villages but inhabited only by small Bedouin groups (Bimkom, 2009,

pages 1213).(4)

A metropolitan outlook clearly surfaced in the governments decision to establish the

industrial area:

[p]lanning of the area will take into account Jerusalems municipalindustrial development

needs (quoted in Bimkom, 2009, page 12).

The government also executed a formal expropriationat the time a highly unusual

procedure which involved a permanent change in the ownership of the landof an area

of 30 km2 (Bimkom, 2009, pages 914).(5) In December 1975 the first two dozen families

moved to Maale Adummim workers camp, but, according to a senior Israeli planner in the

Ministry of Housing Program Department (interview, Jerusalem, November 2010), at that

time a plan had already been put forward for the construction of three new planned towns in

Jerusalems periphery: Maale Adummim, Efrat, and Givat Zeev. In 1977, in one of the last

cabinet sessions before its electoral defeat, the Labour government approved the plan for the

construction of a new large settlement (5000 housing units) in the Maale Adummim area

(4) On the Jahalin Bedouin tribe and Maale Adummim see BTselem, 1999, pages 34, 2122; Bimkom2009; and the website of the Jahalin Association (http://www.jahalin.org).(5)The common procedure before the High Courts landmark ruling on the case of the settlement ofElon Moreh in 1979 was the (theoretically temporary) requisition for military purposes. It should be

pointed out that various legal arguments have been raised against the legality of the expropriationprocedure of the land in 1974 (see Bimkom, 2009).

-

7/28/2019 Israel Settlements en Jerusalen Palestina

4/20

500 M Allegra

(Jerusalem Post1978). After the election, the new Likud government moved to implement

the plan for the new town, which was dedicated in 1982.

Since the early 1980s almost every Israeli government has worked to expand and

consolidate Maale Adummim. The settlement enjoyed the support of Ariel Sharon during his

tenure as Minister of Housing under Yitzhak Shamir, and escaped the partial freeze enacted

by Yitzhak Rabin after 1992 (Friedland and Hecht, 1996, pages 444446). Under Rabin

and after the beginning of the Oslo processthe municipal jurisdiction of the settlement

was extended to an impressive 48 km2 area (against Tel-Avivs 52 km2), so that it touched

Jerusalems city limits. The 1994Metropolitan Jerusalem Master and Development Plan

approved by the government but never formally adopted as policy documentforesaw a

fourfold increase in Jewish population in the growth area of Maale Adummim (Bollens,

2000, pages 5557, 141148). During the years of the Oslo Process (19932000) Maale

Adummims population grew from 17 000 to 25 000 residents.

(6) Givaat Zeev(7) Har Shmuel(8) Modiin Illit(9) Modiin-Reut-Maccabim(10) Bet Shemesh

(11) Beitar Illit(12) Efrata(13) Gilo(14) Har Homa(15) Ramat Shlomo

Jewish settlements:built-up areas

Palestinian localities:built-up areas

Maale Adummim:built-up area

F-1 area (OutlinePlan 420/4)

Green Line

Municipal boundariesof Jerusalem andMaale Adummim

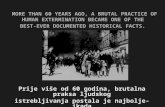

Figure 1. Jewish and Palestinian localities in Metropolitan Jerusalem (source: authors elaboration on

maps by BTselem and Weizman, 2002; Bimkom, 2009, page 19).

(1) Maale Adummim(2) Mishor Adummim industrial area(3) Pisgat Zeev(4) Neve Yaakov(5) Ramot

(16) Mevasseret Zion(17) Kfar Zion

-

7/28/2019 Israel Settlements en Jerusalen Palestina

5/20

The politics of suburbia 501

Since the early 1990s all Israeli governments have explicitly linked the status of Maale

Adummim to that of Jerusalem. Following Rabin, Israel borders after the final status

agreement would include First and foremost, united Jerusalem, which will include both

Maale Adummim and Givat Zeev (Rabin, 1995). In 1998, during a visit to the settlement,the new Likud Premier Benjamin Netanyahu, declared:

the greater Jerusalem area is of equal value to the city of Jerusalem. Therefore the building

here will continue as it does in Jerusalem (Settlement Report, 1998, page 5).

One year later his successor, the labourite Ehud Barak, reiterated the concept saying that his

government considered the settlement to be part of the state of Israel (quoted in Felner,

1999)a position maintained during the Camp David summit of 2000 (see, for example,

WINEP, 2004). Despite strong Palestinian and US opposition (PLO 2009; Rice, 2005),

political consensus on Maale Adummim also included bipartisan support for the construction

of about 3500 new housing units in a 12 km2 area located between Maale Adummim and

Jerusalem (see, for example, Haaretz, 2009;Jerusalem Post2009). The so-called E-1 plan

designates broad expanses of land for regional needs, and the social and economic benefit

of the population of Maaleh Adummim and the district [that is, Jewish settlements and

Jerusalem] (quoted in BTselem, 1999, page 37; see figure 1).

Despite its political genesis as shield to Jerusalem, however, the rapid development and

steady growth of the settlement derived from a wide and diverse basket of other favourable

conditions. First, Maale Adummim represented an answer to a structural need for suburban

housing, due to the congestion of the crowded inner city of Jerusalem (Benvenisti, 1984;

Newman, 1996; Portugali, 1991) and the shrinking of open space in the traditional area of

expansion of the cityon the JerusalemTel-Aviv axis. As a former Jerusalem City Engineer

and member of the Maale Adummim planning team notes:

if we do not regard the political aspect of it, I think [building Maale Adummim] was anormal step giving Jerusalem more time to deal with building in the city , as within

the city you have to go with the spoon ; if there would not have no political pressure,

and still you would say: no, we are not going to let the market to dictate [a development

westward of Jerusalem], but we are going to plan it, where would you recommend to

build a new city? It would be [eastwards] (interview, Tel-Aviv, February 2010).

The planning team also seized the occasion to apply cutting-edge theories and technologies:

efficient metropolitan planning, a new, postmodern outlook based on the variety of spaces

and the search for a local architectural language; and innovative technical solutions such

as the systematic use of climate-measuring stations (interview with former Jerusalem City

Engineer and Maale Adummim planning team member, Tel-Aviv, February 2010; Tamir-Tawil, 2003, pages 156157). The original government guidelines foresaw a new town with

autonomous infrastructure and social services, offering a high standard of living that would

make it competitive with Jerusalem (Tamir-Tawil, 2003, pages 153155; interview with

former Jerusalem City Engineer and Maale Adummim planning team member, Tel-Aviv,

February 2010). The settlement was, therefore, planned to offer a wide range of commercial

services and facilities for culture, education, recreation and sports (Leitersdorf, undated,

page 5).

In order to translate the relatively mild governmental guidelines into reality, the planners

who drafted the project for Maale Adummim changed the location and the scale of the

projectfrom 5000 to 10 000 housing units (interview, Maale Adummim planning team Chief

Architect, Tel-Aviv, November 2010)citing architectural and planning reasons that wouldmake Maale Adummim an attractive residential opportunity and a viable, self-contained,

entity: climate; morphology of the terrain, proximity to employment centres, accessibility

to infrastructures; and, of course, the possibility to see the light of Jerusalem from Maale

Adummim (interview with former Jerusalem City Engineer and Maale Adummim planning

-

7/28/2019 Israel Settlements en Jerusalen Palestina

6/20

502 M Allegra

team member, Tel-Aviv, February 2010; see also Leitersdorf, undated; Tamir-Tawil, 2003,

page 153).

The implementation of the project involved the mobilization of considerable skills and

resources: the project was carried out through the parallel design of outline and detailedplans of the neighbourhoods and the rapid mobilization of 10 construction companies, 80

consultants and the allocation of massive resources by the Ministry of Housing (Leitersdorf,

undated, page 1). As a result, the whole process proceeded at a very fast pace: 2600 housing

units were built at a unique rate of development in Israel (Leitersdorf, quoted in Weizman,

2007, page 112). The preliminary survey took place at the end of 1977; in November 1979 a

ground-breaking ceremony was held, and the town was dedicated in September 1982. By 1983

the families who arrived in Maale Adummim found eighteen kindergartens, seventy-five

small factories, and three synagogues (Thorpe, 1984, page 117).

New buildings, sound planning, schools and kindergartens, beautiful views of Jerusalem

and the Judean Desert in a large, modern settlement within minutes of the inner cityMaale

Adummim had much to offer the average middle-class Jerusalemite. An advertisement

published in theJerusalem Postin 1983 read:

Outside JerusalemYet so NearA 7 minute ride from Jerusalem and youll find

yourself at Maaleh Adummim . A well-planned neighbourhood in the best location in

town! (reproduced in Thorpe, 1984, page 119).

Much to the chagrin of Maale Adummim residents, the vast majority of whom work

in Jerusalem, today the 7 minute ride promised by real estate agents during the 1980s is

often a fantasy, due to the huge traffic problems of the Jerusalem area. Nonetheless, large

infrastructural investments offer the residents the advantages noted in general with respect to

the separate system of roads serving the settlements:

a fast and uncomplicated connection and the feeling that they live almost inJerusalem that they are not at the frontier, but a natural expansion of suburbia into the

mainstream of Israeli life (Pullan et al, 2007, page 182).

After the opening of the new road between the settlement and Jerusalem, and the tunnel

under Mt Scopus, the surrounding Palestinian communities almost disappeared from

the landscape, as is shown in the experience described by Meron Benvenisti of the road

connecting Jerusalem to Gilo:

the person travelling on the longest bridge in the country and penetrating the earth

in the longest tunnel may ignore the fact that over his head there is a whole Palestinian

town he does not come across any Arab, save for some drivers that dare go on the

Jewish roads (Weizmann, 2002).Indeed, its political genesis notwithstanding, the development of Maale Adummim came

to reproduce the basic principles of all planned suburbs since the early 1920s:

order/efficiency, daily exposure to natures beauty and goodness, use of technology to

improve the residents quality of life, aesthetic quality, and the values of individuality,

family and community (Modarres and Kirby, 2010, page 116).

Today, the Jewish Agency offers the following description of Maale Adummim to potential

olim (Jewish immigrants):

[t]he diversity and services of a city, the warmth and quiet of a small town and the

cleanliness and preplanned design of suburbia . Surrounded by the breathtaking hills

of the Judean desert, permeated with the dry, yet cool desert breeze and adorned with

wide flowered boulevards and an abundance of parks, Maaleh Adummim offers a highstandard of living, a rich community life, cultural diversity and excellent schools and

facilities . Offering the social diversity of the city, Maaleh Adummim nonetheless

-

7/28/2019 Israel Settlements en Jerusalen Palestina

7/20

The politics of suburbia 503

maintains a camaraderie of neighbourhood connection, synagogue affiliation and a

general sense of community involvement (Jewish Agency, 2010).

The settlement received various awards from Israeli authorities for the quality of its

educational facilities and environment. As theIsrael Environment Bulletin (1993) reportedafter the award of the Environmental Prize for Local Authorities, Maale Adummim surpassed

its [52] municipal competitors in such categories as physical appearance, cleanliness,

gardening, street signs and solid waste management (see also BTselem, 1999, page 18).

As Robert Friedman noted, settlements like Maale Adummim are not only affordable,

but are also attractive suburban housing developments that would not look out of place

in Phoenix or Orange County, California (1992, pages xxivxxv). The new, fast-growing

modern town just outside Jerusalem came to be perceived as part of Jerusalem both by its

inhabitants and by Israeli public opinion. The first residents of Maale Adummim had no

specific political affiliation or strong organizational links to the settler movement, and the

settlement grew up maintaining this original feature: the population of Maale Adummim

grew as fast as it did because of the influx of nonideological Jerusalemite commuters looking

for better housing opportunities.

Political and institutional factors did remain relevant in the process of development of

suburban settlements: attractive suburban utopias such as Maale Adummim were realized

with generous financial backing from the government. Of course, settlers did enjoyand still

doa wide and diverse basket of public incentives adding to the market-related price gap

between Jerusalem and the suburbs: artificially low land prices, public incentives to developers,

state allowances for mortgages, etcnot to mention the budget for security-related issues

(Hever 2010, pages 6268; Reuveny 2003, pages 359360).

Nevertheless, whereas incentives were applied throughout the West Bank to the point that

in many locations housing availability regularly surpassed demand, this was never the casein Maale Adummima community of almost 40 000 which is still growing. When asked

about the current expansion project of the settlement, even many stern critics of Israels

settlement policywhile still contesting the idea that any settlements should be allowed

to grow at alladmit that Maale Adummim has almost exhausted the land available for

residential construction due to population increase (interviews with a researcher working

for BTselem and an architect working for Bimkom, Jerusalem, February and November

2010, respectively).

3 Lefebvre in Jerusalem: the production of space in a contested metropolitan region

What does the history of Maale Adummim imply for an analysis of Israels settlement

policy? And how can Lefebvres theory of space be used to illuminate the role of this policy

as an engine of the transformation of IsraeliPalestinian relations? A useful starting point

is Brenner and Eldens (2009) account of Lefebvres work as theorist of territoryand

especially with reference to the notions of territorial strategies, production of territory,

and territory effect.

Following Brenners and Eldens reading of Lefebvre, territory represents a historically

specific political form of (produced) space (page 363) that is defined by its relation with

the state and state-building practices. In this respect, we see settlement policy as a territorial

strategy for the creation of a new state space in the land occupied by Israel in 1967. Planning

broadly defined as the formulation, content and implementation of spatial public policies

(Yiftachel, 1998, page 395)can be seen as a crucial tool in this process. At the same time,Lefebvre insists that the process is not simply a one-way, instrumental one, with the state

making and remaking a purportedly pregiven, malleable space . For Lefebvre, the

geographies of state space are themselves arenas, stakes and outcomes of such struggles

(Brenner and Elden, 2009, pages 364, 369).

-

7/28/2019 Israel Settlements en Jerusalen Palestina

8/20

504 M Allegra

In other words, Lefebvre invites us to consider theproduction of territory as a multifaceted

and dynamic social process. For Lefebvre space is not only composed of different fundamental

componentsspatial practices (the perceived space, the spatial structure of social relations),

abstract representations of space (the conceived space, the formalized space of planners andsocial engineers); and spatial perceptions (the lived space, the space as directly experienced

by individuals through a complex lens made up of senses, symbols, and culture)but is

historically and contextually produced through social practices that are qualitatively different

from a simple straightforward exercise of sociospatial engineering.

Against this background, Brenner and Elden define as territory effect the fetishization

of territory or, as Lefebvre describes it, the illusion of transparency (pages 370373), the

deceptively simple and natural appearance of spacesee also John Agnews (1994) notion

of the territorial trap. The task of social scientists would be, on the one hand, to avoid

fetishization of territory by carefully exploring the social dynamics of production of space;

and, on the other hand, to investigate the very emergence of the territory effect as a result of

the production of space itself.

A Lefebvrian account of Israels settlement policy, I argue, offers a more coherent

and nuanced understanding of the process of incorporation of the West Bank into Israels

state space than do other theoretical approaches: see, for example, Lusticks (1993)

thresholds model, or the suggestive but sparse insights of Weizmans (2007) architecture

of occupation. Although not inherently comparative (see, instead, Bollens, 2000; Lustick,

1993, or the concept of the laboratory of extreme put forward by Weizman, 2007), it also

allows meaningful generalizations and lays the ground for comparative analysis. In addition,

a careful and nuanced engagement with the notion of production of territory offers us a

way out from the reification of history and collective identities that is implicit in much of

the literature on contested cities (Anderson 2008; Kotek 1999; for the same argument, seeAllegra et al, 2012).

In order to do so, and to understand Israels settlement policy as a process of production

of space, I consider the history of Maale Adummim by adopting the metropolitan area of

Jerusalem as the fundamental sociospatial scale of my investigation arena, and as a social

product of the struggle for appropriating the contested landscape of Jerusalem. A few

considerations on the idea of metropolitan Jerusalem are therefore in order, along with a

tentative, broad-brush, definition of the metropolitan area.

Every definition of a metropolitan area is, to a certain extent, arbitrary. In Jerusalem a

further difficulty derives from the existence of an intricate grid of jurisdictionsdetermined

by the mixed and fragmented nature of sovereigntyand from the extreme politicizationof almost every issue linked to urban policies and development: from archaeology to public

transportation, housing, and nature reserves. Jerusalems intricate tangle of overlapping

boundaries and political issues is reflected in the lack of systematic data collection on a

metropolitan scale. The yearly Statistical Abstractpublished by the ICBS, for example,

presents data for the metropolitan areas of Tel-Aviv, Haifa, and Beer Sheva, but not for the

metropolitan region of Jerusalem (2008, table 2.16). Although in 2010 the JIIS published

for the first time in its Statistical Yearbookdata on Jerusalems environs, it only included

Jewish local authorities (JIIS, 2010); as one of the JIIS planners remarked: we wont have

data on the Palestinian population on the metropolitan area [in the Statistical Yearbook],

although this data is available we will not publish it (interview, Jerusalem, February

2010).For practical purposes in this paper I assume the definition of the Jerusalem Region put

forward by the JIIS as a territorial base, and therefore refer to an area included in a range

-

7/28/2019 Israel Settlements en Jerusalen Palestina

9/20

The politics of suburbia 505

Table 1. Metropolitan Jerusalem: territorial and demographic components (figures for 2007) [source:

authors estimates based on data from the Jerusalem Institute for Israeli Studies (JIIS 2008, table III/16,

XVII/4) and the Palestinian Bureau of Statistics (PCBS, 2009)].

Population Jews Palestinians

A Jerusalem a 750 000 490 000 260 000

A.1Of which in East Jerusalem 450 000 190 000b 260 000

B Israel (West Jerusalem excluded) 210 000 200 000 10 000

C West Bank (East Jerusalem excluded) 980 000 195 000 c 780 000 d

Jerusalem Region (A+ B+C) 1 940 000 885 000 1 050 000

a Jerusalem in the Israeli-defined municipal borders, including the about 70 km2 of East Jerusalem,whose occupation is not recognized by the international community.bThis figure was determined by summing the population of the city subquarters (JIIS, 2008, table II/16)listed by BTselem (2011) as located east of the Green Line. I added to BTselems figures the 1362Israeli Jews living within the Old City but outside the Jewish Quarter (from JIIS, 2008, table III/16).cThis figure includes Jewish communities east of the Green Line, where the main population centresare Modiin Illit (38 000), Maale Adummim (33 000), Beitar Illit (32 000) and Givaat Zeev (10 900);the area includes also the Regional Counciladministrative units reuniting smaller centresof Matte

Binyamin (43 400) and Gush Etzion (13 600).dThis figure includes Palestinian localities in the governorates of Ramallah, Jerusalem, Bethlehem,

and Hebron. The major population centres in the area are Hebron (163 146), al-Bireh (38 202),

Ramallah (27 460), Bethlehem (25 266), Halhul (22 128), and ar-Ram/Dehiyat al-Bareed (20 359); 11

other centres have a population larger than 10 000, and other 24 larger than 5000.

Palestinian localities:built-up areas

Figure 2. Metropolitan Jerusalem (source: Authors elaboration on a map by De Jong, 1997).

Jerusalem:municipal boundaries

Small metropolitanJerusalem(de Jong, 1997)

Large metropolitanJerusalem(authors elaboration

Green line

-

7/28/2019 Israel Settlements en Jerusalen Palestina

10/20

506 M Allegra

2030 km from the Old City, with a population of about two million people with a slight

prevalence of Palestinians (see figure 2 and table 1).(6)

4 Settling for suburbs: unveiling the Jerusalem effect

Adopting a Lefebvrian angle means interrogating the very notion of space, and unmasking

the territory effect. This is even more necessary because of the fragmented and contested

nature of jurisdiction in the West Bank, where practices of gerrymandering are part and parcel

of the confl

ict itself. In taking the metropolitan area of Jerusalem as the unit of analysis anddelving into the history of Maale Adummim, my goal is precisely to call into question some

longstanding, implicit, territorial assumptions inherent to the discourse on Israels settlement

policy.

More specifically, I argue that a sort of Jerusalem effectthe adoption of the

Israeli-defined municipal boundaries of Jerusalem as a territorial watershedhinders our

understanding of Israels settlement policy. As Janet Abu-Lughod (1982, page 25) observed,

settlements such as Ramat Eshkol, French Hill, Neve Yaakov, Gilo, East Talpiyyot, or

Ramot, disappeared from the academic production on Israels settlement policy precisely

because of their inclusion in the Israeli-defined municipal borders of Jerusalem. This shielded

them from the criticism more easily directed towards other localities in the West Bank, but

also obscured the fundamental suburban component of the settlement policy.Still, it is easy to point out that the absurd (Benvenisti, 1995, page 53) new municipal

boundaries of the cityredrawn in the aftermath of the 1967 war to include about 70 km2

of former Jordanian territoryalready had an explicit metropolitan character: Major

Rehavam Zeevi, head of the ministerial committee charged with the matter, summarized

the principles guiding the drawing of the new boundaries by referring to the maximum

increase of territory allowing the city to expand into a great metropolis (Gazit, 2003,

(6) Figures presented in table 1 and table 2 are my own very raw estimates; many other possibledefinitions of metropolitan Jerusalem can be adopted (see, for example, Benvenisti, 1984; DeJong, 1997, Hochstein, 1983; Portugali, 1991; Rosen and Shlay, 2010; Sharkansky and Auerbach,

2000; Stern, 1990). Another debatable issue is that of how to define the metropolitan area in thelight of movement restrictions applied to Palestinians (on this issue, see Khamaisi, 2008, Nasrallah2008). I considered a large Jerusalem Region as defined by the JIIS (2010, table XVII/4, figuresfor 2007see figure 2) and added population data (from the Palestinian Census realized in 2007

by the Palestinian Bureau of Statistics, PCBS, 2009) for 143 Palestinian communities locatedwithin the area.

Table 2. Settler population in Metropolitan Jerusalem and in the West Bank (figures for 2007)

[source: authors estimates based on data from the Jerusalem Institute for Israeli Studies (JIIS, 2008,

table III/16) and the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics (ICBS, 2008, table 2.9)].

Settlerpopulation

A West Bank (Metropolitan area of Jerusalem) 385 000

A.1of which inside East Jerusalem 190 000 a

A.2of which outside East Jerusalem 195 000

B West Bank (excluding Metropolitan area of Jerusalem) 80 000b

Total settler population in the West Bank (A+B) 465 000

a See note b in table 1.bThis figure was calculated by subtracting the figure A.2 from the total settler population of the West

Bank as calculated by the ICBS (2008, table 2.9; the figure for 2007 is 276 100); the ICBS does not

consider the Israeli residents of East Jerusalem as part of the population of the West Bank (Judea and

Samaria following the official label used by the ICBS).

-

7/28/2019 Israel Settlements en Jerusalen Palestina

11/20

The politics of suburbia 507

page 246). Many settlements built after 1967 within the municipal bordersas an Israeli

planner working for the JIIS notes with respect to Gilo, Pisgat Zeev and Ramot,

would they be separate from Jerusalem, they would get immediately the status of

city . [T]hese neighbourhoods function as suburbs and the inner city function as a coremetropolitan area, but we dont see it so much in the data because those neighbourhoods

are inside the municipal borders (interview, Jerusalem, February 2010).

In other words, despite their different status in the Israeli administrative system, Gilo

and Pisgat Zeev (built within Jerusalems municipal boundaries, by Labour and Likud

governments, respectively), as well as Maale Adummim (an autonomous municipality) are

all state-sponsored suburban settlements in the metropolitan area of Jerusalem.

One important implication of the adoption of metropolitan Jerusalem as my unit of

analysis is that, as far as the development of Israels settlement policy is concerned, the

similarities between the policies implemented by the Likud and the Labour government,

respectively, appear much more significant than their differences. Much of the literature on

the conflict explains the so-called settlement boom of the 1980s by referring to the new,

more aggressive, settlement strategy of the Likud as a turning point. As Weizman puts it, after

the Likuds electoral victory in 1977, the government [of Menachem Begin, the first Likud

Prime Minister] made an early attempt to transform the settlement project from improvised

undertaking into an elaborate state project (2007, page 111). Segev, in rejecting Gorembergs

claim that the policy of the Likud was simply an escalation of preexisting trends, argues that

[a]lthough by 1977 settlers had already started moving into the territories, at that point

they numbered less than 60 000, and about 40 000of them lived in East Jerusalem (2006,

page 148, emphasis added).

However, these interpretations are based on the arbitrary distinction between the

settlements inside and outside Jerusalem municipal boundaries. If one refers, for example,to the metropolitan area of Jerusalem instead of to the municipal boundaries of the city,

Segevs figures hardly prove his point. What they really tell us is that, to use Weizmans

words, settlement policy outside the inner city of Jerusalem was already an elaborate state

project during the Labour era. In fact, ten years after 1977 the settler population outside East

Jerusalem had grown to 50 000 people (Peace Now, 2009; Maale Adummim alone had about

11 000 residents at that date) an increase comparable with the one which Segev reports for

the first decade of the occupation. Indeed, senior planners in the Israeli Ministry of Housing

(Jerusalem District and Program Department) describe the various phases of metropolitan

developmentfrom the early construction of settlements within Jerusalems city limits after

1967, to the birth of Maale Adummim, Givat Zeev, and Efrat, to later development in the1980sin terms of an overall process of strengthening Jewish Jerusalem through the creation

of a Jewish hinterland east of the city (interviews, Jerusalem, November 2010).

At the same time, even after 1977 Jewish colonization of the West Bank was mostly part

of the metropolitan expansion of the Tel-Aviv region and the metropolization of Jerusalem;

the inner city of Jerusalem, in particular, has contributed more than any other Israeli town

to Jewish colonization of the West Bank because of the huge flows towards the surrounding

suburban settlements (Portugali, 1991, pages 33, 46). Maale Adummim is an example of

how even the territorial maximalism of the Likud adapted to suburban trends. Although

apparently the development of a large metropolitan settlement did not fit the original Likuds

ideological settlement patternthe conquest of the land through the establishment of

small Jewish settlements in the central massif of the West Bank, aimed at sabotaging anyfuture territorial compromise with Israels neighbours (Benvenisti, 1984, pages 5255)

Likud politicians showed flexibility towards planning arguments and acknowledged the

suburbanization trend operating in Israeli society. It was under the Likud that the original

location chose in 1977 by Labour for the new town of Maale Adummima few kilometres

-

7/28/2019 Israel Settlements en Jerusalen Palestina

12/20

508 M Allegra

eastward toward Jericho, the furthest place from Israel that was conceivably possible

[Thomas Leitersdorf, Chief Architect for the Maale Adummim Planning Team, quoted in

Tamir-Tawil (2003, pages 152153)]was changed at the planners request in favour of the

present site, nearer to Jerusalem (Jerusalem Post1978).The Likud understood that the demand for suburban housing, if channelled towards the

West Bank areas adjacent to Tel-Aviv and Jerusalem, could produce the quantitative shift in

the settler populations which was otherwise impossible to achieve. This new outlook found

its concretization in the Master Plan drafted in 1983 by the World Zionist Organization and

the Ministry of Agriculturea plan which cannot be viewed as other than the official land

use plan for the West Bank at the time (Benvenisti, 1984, page 28; see also pages 2629,

5763). The plan emphasized the role of semi-urban settlements of high quality of life in

demand zones (1983 Master Plan, quoted in Benvenisti, 1984, page 58, see also page 60).

The unleashing of the suburban potential of the settlements, in turn, did produce political

consequences that were not lost even to the ideologized Gush Emunim pioneers:

[f]rom the outset, we talked about the fact that Samaria will be a success when people will

move here exactly for the same reasons they move from Nethanya to Hadera [two cities in

Israel]. I am not sorry about the decline in ideological tension ... . In order for a settlement

to become normal, it must not consist of idealists alone (Feige, 2009, page 72).

As Pinhas Wallerstein (head of the Binyamin Regional Council, and former Secretary

General of the Yesha Council) noted with respect to depoliticized settlers of Beitar Illit:

I expect nothing from the Haredi settlers. But even if they didnt come here for ideological

reasons, they wont give up their homes so easily (Haaretz, 2003).

And indeed, nonideological settlers were coming. Despite governmental policies of

financial incentives favouring settlement in more remote areas of the West Bank, during

the decade after the creation of the Maale Adummim, seven out of the ten fastest growingsettlements were located within the metropolitan area of Jerusalem (FMEP, 2010). In 2002,

77% of Israeli residents in the West Bankexcluding East Jerusalemcited quality of life

factors as primary motivation for living in the settlements (The Guardian 2010). Today, as my

calculations show (see table 2), the vast majority of settlers live in large suburban communities

around Jerusalem. Even adopting a narrower definition of the metropolitan area, the picture

does not change: in 2008 out of twenty-one settlements with a population of more than 5000

inhabitants, nine were inside Jerusalems municipal borders, and five (Maale Adummim,

Givaat Zeev, Efrata, Betar Illit, and Modiin Illit) were located in the main settlement blocs

just outside the city limits, between 5 km and 10 km from the Green Line; the population of

these fourteen settlements alone was about 310 000 people (BTselem, 2010).In other words, the turning point which Segev and Weizmann are talking about is much

less evident if we do not consider the somewhat arbitrary distinction between the settlements

inside and those outside Jerusalems municipal boundaries. Despite their differences in terms

of planning preferences (Reichman, 1986), both Labour and Likud focused their efforts

on settling the metropolitan area of Jerusalem, and this convergence represents the most

important feature of Israels settlement policy as a whole.

At the same time, the Israeli government was not so successful in promoting

settlements in more remote areas of the West Bank. The demographic weight of Labours

strategic settlements remained negligible. The score of the Likudwhose territorial and

demographic stated goals were more explicit and radical than those of Labourhas not been

very different. Under the 1983 Master Plan, for example, settlements located in the highdemand areasdefined by commuting distance with respect to the outer ring of Tel-Aviv

and Jerusalemreceived less government subsidy than did the high priority areasmainly

located on the hills of the West Bank (Weizman, 2007, pages 122125). Nonetheless, if we

consider the twenty-four settlements with a population of 2000 or more (figures for 2007),

-

7/28/2019 Israel Settlements en Jerusalen Palestina

13/20

The politics of suburbia 509

only five are located in the 1983 high priority areasthree of which are in any case located

in high-demand areas around Jerusalem [authors elaboration on data from Benvenisti (1984,

page 81), BTselem and Weizman (2002), Peace Now (2011)]. In other words, the policy of

differential financial assistance provided by the government has been largely unable to pushthe settlers outside the metropolitan belt of Jerusalem (see also Newman, 1996, pages 6466),

to more remote locations where architecture replaces human presence (Segal and Weizman,

2003, page 22).

5 Maale Adummim is Jerusalem: producing a new metropolitan space

Suburban settlements such as Maale Adummim are a key element of this process of

suburbanization of Israels settlement policy, which is usually interpreted as a purely

political enterprise: as a project of conquest of the land carried out by the settlers movement

and the Israeli state for nationalistic or millenaristic motives. In Lefebvrian terms, this

interpretation establishes a sort of hierarchy among the three dimensions of space/territory,

and the territorial struggle in the West Bank is often portrayed in terms of an imposition of the

colonial conceived space (a project of sociospatial engineering linked to political ideology and

planning practices) over the indigenous lived spaceas in Libby Porters (2010, pages 15,

45) Lefebvrian description of the complicity between planning and colonialism in Australia. I

argue that this would be a superficial understanding both of the dynamic of Israels settlement

policy and of Lefebvres work.

It is, of course, impossible to ignore the role of the Israeli state in the process. As Eyal

Benvenisti (1989, preface) pointed out, the pre-June 1967 borders have faded for almost

all legal purposes that reflect Israeli interests. The history of Maale Adummima planned

town built by the Israeli government on occupied territorybears the mark of a direct

intervention of the Israeli state, pursuing goals linked to Zionist ideology, national interest,and perceived security reasons. As such, it stands in marked contrast to the interpretation

of the settlement policy as an incremental phenomenon driven by bottom-up pressure from

settlers grassroots organizations (see, for example, Eldar and Zertal, 2007)and, of course,

with its description in terms of an accidental (Goremberg, 2006), foolish (Gazit, 2003),

innocent (Shimon Peres, in Gazit, 2003, page xix), and ultimately unwanted, entanglement.

At the same time, it would be impossible to deny that politicized urban planning has

been one of the main drivers of the development of the metropolitan area of Jerusalem since

the reunification of the city after 1967. As Andreas Faludi puts it, although Jerusalem lacks

a planning doctrine, what is evident, however, is a strong sense of purpose behind

developments in East Jerusalem, namely, [t]he widely, if not unanimously shared political

goal [of] the permanent unification of Jerusalem under Israeli rule (1997, page 98). This

broad ideological frame has been translated into a partisan urban planning policy whose aim

has been winningrather than settlingthe conflict in Jerusalem by further strengthening

Israels control over the city (Bollens, 2000; Dumper, 1997; Yacobi and Yiftachel, 2002).

Planning in Jerusalem is, of course, the product of an overall ethnonationalist governing

ideology favouring Jewish development and national goals over Palestinian ones (Bollens,

2000, pages 1933, 307324; see also Yacobi and Yiftachel, 2002).

Nevertheless, acceptance of a linear account of Israels settlement policy means that

our analysis of the phenomenon as dehistoricized and decontextualized, to the point that

the crucial dimension of the real contextual rationality of the planning process (Flyvbjerg,

1996) is lost. To think of Israeli planning as war carried out by other means (Coon, 1992,page 210), while correctly acknowledging the partisan nature of the planning system, suggests

the idea of the existence of a fully fledged, carefully calculated, strategy behind planning, and

reduces planning to a subordinate and instrumental roleultimately leaving no room for any

analysis of the agency of other actors beyond the dichotomy of complicityresistance.

-

7/28/2019 Israel Settlements en Jerusalen Palestina

14/20

510 M Allegra

As for the first point, while a discussion of the nature and coherence of Israeli decision

making is outside my purposes in this paper, it can be pointed out that even the development

of the state-planned new town of Maale Adummim does not reproduce the mechanism

of comprehensive, controlled and efficient architectural experiments like that whichmarked the Israeli policy of population dispersal of the Sharon plan in the 1950 (Efrat,

2003, page 60). The key to the success of Maale Adummim lies precisely at the junction

between centralized planning, market preferences, and suburbanization trends. Concepts

such as Yiftachels (2003) settlement instinct or reflex action appear, therefore, likely to

be more fruitful in explaining Israels settlement policy than is referring to a comprehensive,

centralized, plan.

As for the second point, planners have not simply been a tool in the hands of politicians.

While is fair to say that geopolitical and national considerations created the context in which

Maale Adummim was born, professional and neutral arguments have been important in

determining the development of the new town. At the same time, as Yiftachel (1998) notes

in his critique of the dark side of planning, and contrary to widespread perceptions among

Israeli professionals, the influence of planning expertise on the development of Maale

Adummim did not diminish the political consequences of Israels settlement policy. Rather,

it can be said that sometimes those consequences were even maximized. The mobilization

of planning arguments in defining the location and scale of the settlementemphasizing the

need to create a functioning urban unitproduced permanent political consequences: directly,

by cutting the Palestinian West Bank in two through the construction of a Jewish town from

scratch; and indirectly, by creating the conditions for the success story of an ultimately

controversial urban policy [for a similar conclusion about infrastructural investments, see

Pullan et al (2007, page 178)].

More broadly, the experience of Maale Adummim suggests that the relative successof Israeli settlement policy in producing a new set of sociospatial arrangements cannot be

reduced to the execution of a top-down political project of sociospatial engineering: rather,

it depended instead on a variety of factors. Discussing how the Likud government had come

to terms with the contradiction between its original policy of population dispersal inherent to

the concept of conquest of the land, and the creation of a large satellite town near Jerusalem,

Thomas Leitersdorf notes that:

[Maale Adummim] was a success story and every apartment that went on the market

was instantly grabbed. So the politicians said, Ok, the population in Judea and Samaria

is growing, we have no marketing problems and we dont have to pay huge subsidies to

support mobile homes on various hills . I would say that the glory of that time wasthat the planning and political considerations went hand in hand (Leitersdorf, quoted in

Tamir-Tawil, 2003, pages 155156).

What determined the convergence of the preferences of (Israeli) politicians, planners, and

consumers? For Brenner and Elden, Lefebvres own work is a reminder that the production

of territory does not take place on a tabula rasa:

[s]tates make their own territories, not under circumstances they have chosen, but under

the given and inherited circumstances with which they are confronted (2009, page 367).

Building on Lefebvre and borrowing from the vocabulary of actor-network theory, we could

say that territory has agency: this convergence found its locus, its centre of gravity, in the

metropolitan area of Jerusalem.(7)

(7)An often forgotten fact about Israeli settlement policy is the role of constraints posed by thephysical, human, and legal landscape of the West Bank on the unrestrained expansion of settlements.The strategy of capturing the hills, for example, did not answer only to Israeli politico-military needs,

but also resulted from the preexisting distribution of Palestinian settlement and agricultural land, aswell as the legal geography of the Ottoman land law (see, for example, Weizman, 2007, page 117).

-

7/28/2019 Israel Settlements en Jerusalen Palestina

15/20

The politics of suburbia 511

While still conceding that the post 1978 wave of settlement reflected to a certain extent

Likuds rise to power, Portugali notes that it also implied the unfolding, or the realization,

of most of the spatio-economic potentialities of the West Bank hitherto unrealized. Namely,

its close proximity to the metropolitan region of Tel-Aviv and the city of Jerusalem (1991,page 32). The peculiar situation in which this rush toward bourgeois utopias (Fishman,

1986) took place in Jerusalem did create obvious differences from the much more market-

driven American urban development; however, after 1967 the Green Line acted as a boundary

of price discontinuity of land prices, thereby creating new incentives for Israelis to move to

bedroom communities in the periphery of the cityincentives that run parallel to the political

impetus toward colonization (Newman, 1996). As Yiftachel observes, beyond the powerful

impact of the settling ethnocratic culture, there are some influential groups that gain from

the establishment of settlements, such as developers and upwardly mobile groups who

seek quality of life often an euphemism for the rush of middle-class families into gated,

or controlled, suburban localities, protected from the proximity of undesirables (2003,

page 36), be they Palestinians or fellow Jews.

The very experience of suburban settler-consumers makes a stark contrast with the

description of Hebron offered by a local settlers leader:

this is not the place that you come to in order to build a cottage and cultivate a garden.

It is a place that is meant to articulate the fact that the people of Israel will not desert the

city of the Patriarchs (quoted in Feige, 2009, page 182; see also Feige 2001).

Elsewhere in the West Bank, however,

a cottage and a garden were exactly what many settlers wished for. Many were not

dedicated to the idea of a Greater Israel, but grasped the opportunity, given them by the

state, to improve their standard of living. Although they reside in the occupied territories,

these settlers define themselves as normal Israelis and distance themselves from thoseliving on the mountain ridge of Judea and Samaria, whom they define as religious

fanatics (Feige, 2009, page 182).

The suburban formula Maale Adummim is Jerusalemfound in planning documents,

political leaflets, and real estate commercials, each dimension strengthening and legitimizing

the otherlaid the conditions for the rapid growth of the settlement as the territorial common

denominator of the preferences of different sectors of Israeli society. For politicians, Maale

Adummims link to Jerusalem was essentially politico-strategic, as the fast-growing new

town represented a permanent territorial and demographic fact on the ground in the political

game for Jerusalem. Planners saw this link in terms of urban planning issues, as Maale

Adummim constituted an appropriate answer to the need for a rational expansion of the cityand an occasion to apply their professional skills to the creation of a new town from scratch.

In addition, for the Jerusalemite Jewish middle class, hungry for housing opportunities, the

quiet suburban community of Maale Adummim was the best place in town in terms of

affordability and quality of life within commuting distance of the inner city.

At the same time, the multifaceted nature of the process of place-making embodied

in the development of settlements such as Maale Adummim represented the fundamental

force that gradually transformed the spatial and social perceptions of what Jerusalem is

(Shlay and Rosen, 2010, page 384). After the evacuation of the settlements in the Sinai,

following the IsraeliEgyptian peace treaty, Rabbi Yoel Bin-Nuna settler leader of

the timeobserved that the settler movement had been unable to settle in the heart of the

nationmeaning that the settlement project remained controversial for Israeli society aswhole. Indeed, the settler-consumers of Maale Adummim succeeded in this purpose: albeit

in ways that the Rabbi would probably consider too mundane, they did manage to settle in

the heart of Israel. A new community of Jerusalemites, and a new self-perception of

indigeneity, arose not simply from Zionist ethos or planning documents, but from Maale

-

7/28/2019 Israel Settlements en Jerusalen Palestina

16/20

512 M Allegra

Adummims villas, from the shopping mall, from the neat boulevards beautified by palms

and olive trees.

6 ConclusionThe underlying argument of this paper is that the observation of suburban settlements in the

metropolitan area of Jerusalem represents an important inroad into the dynamics of Israels

settlement policy.

Consideration of the metropolitan area of the city offers a more realistic picture of Israels

settlement policy. This allows us to get rid of the misleading reference to the legal status

of settlements under Israeli lawand, in particular, the arbitrary distinction between Israeli-

defined Jerusalem and the rest of the West Bank, on which the narrative describing structural

differences between the Labor and Likud governments is based. The development of suburban

settlements such as Maale Adummim is also an example of the complex dynamics of the

production of territory in the contested metropolitan landscape of Jerusalemthereby

contradicting its representation in terms of a top-down, controlled, experiment of sociospatial

engineering, as well as the simplistic linear accounts of the nexus between politics and

planning.

The struggle for the production of territory reshaped the metropolis of Jerusalem

along the three Lefebvrian dimensions of conceived, perceived, and lived space. Abstract

images of the metropolis (the political dream of Jewish Jerusalem, as well as blueprints

detailing commuterflows) have been used by Israeli planners and policy makers to draw

models and future images of the metropolis. At the same time, however, a comprehensive

redefinition of the material infrastructure of the metropolitan space has been realized, which

transformed Jewish Jerusalem from the pre-1967 truncated border city into a metropolitan

hub for a vast Jewish hinterland beyond the Green Line. Last but not least, the developmentof suburban communities like Maale Adummim created a new perception of the boundaries

and the very nature of Jerusalem deeply rooted in the mind of the Israeli public. In its role

of territorial common denominator of the preferences of different sectors of Israeli society,

Maale Adummim can be considered a success story of Israels settlement policy. Thriving

suburban communities such as Maale Adummim have been a crucial factor in the process

of obliteration of the pre-1967 Green Line: today, almost no one in Israel considers the

possibility of evacuating Maale Adummim as either a desirable or a realistic option under

any scenario, because of its size, as a senior member of the Geneva Initiative group noted

(interview, Tel-Aviv, January 2010).

However, There is a continual production of territory, rather than an initial moment

that creates a framework or container within with future struggles are played out (Brenner

and Elden, 2009, page 367). The success story of Maale Adummim cannot hide the inherent

contradictions of Israels settlement policy. After more than four decades of settlement activity,

the resulting bundle of Jewish and Palestinian territorialities, of conflict and proximity, today

represents the core issue in the conflict. Indeed, as the recently leaked Palestinian papers

(Aljazeera, 2011a; 2011b) confirmed, Maale Adummim represents a major obstacle for

the so-called two-state solution. Ironically, the existence of communities such as Maale

Adummim is also one of the main arguments of the supporters of the so-called one-state

solution for the creation of a single democratic state in the whole of Israel/Palestineand

thereby the end of Israel as a Jewish state. Despite its success, the development of Maale

Adummim is a stark reminder of the illusion that urban contradictions could be supersededby urban design (Castells, 1983, page 94).

Acknowledgements. The author would like to thank Haim Yacobi and the three anonymous referees

for their comments on earlier drafts of this paper.

-

7/28/2019 Israel Settlements en Jerusalen Palestina

17/20

The politics of suburbia 513

References

Abu-Lughod J, 1982, Israeli settlement in the occupied Arab Lands: conquest to colonyJournal of

Palestine Studies11(2) 1654

Aljazeera, 2011a, The Palestine Papers the biggest yerushalayim , 23 January,http://english.aljazeera.net/palestinepapers/2011/01/2011122112512844113.html

Aljazeera, 2011b, The Palestine Papers. The napkin map revealed, 23 January,

http://english.aljazeera.net/palestinepapers/2011/01/2011122114239940577.html

Allegra M, Casaglia A, Rokem J, 2012, The political geographies of urban polarization. A critical

review of research on divided cities Geography Compass6 560574

Anderson B, 1983Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism

(Verso, London)

Anderson J, 2008, From empires to ethno-national conflicts: a framework for studying divided

cities in contested states , WP 1, Conflict in Cities and the Contested State Programme,

http://www.conflictincities.org/workingpapers.html

Aran G, 1986, From religious Zionism to Zionist religion: the roots of Gush Emunim Studies in

Contemporary Jewry2 116143Aran G, 1991, Jewish Zionist fundamentalism: the block of the faithful in Israel (Gush Emunim),

inFundamentalism ObservedEds M E Marty, R S Appleby (University of Chicago Press,

Chicago) pp 265344

Auerbach G, Sharkansky I, 2000, Which Jerusalem? A consideration of concepts and borders

Environment and Planning D: Society and Space18 395409

Benvenisti E, 1989Legal Dualism: The Absorption of the Occupied Territories into Israel(Westview

Press, Boulder, CO)

Benvenisti M, 1984 The West Bank Data Project. A Survey of Israels Policies (American Enterprise

Institute for Public Policy Research, Washington and London)

Benvenisti M, 1995Intimate Enemies. Jews and Arabs in a Shared Land(University of California

Press, Berkeley, CA)

Bimkom, 2009, The hidden agenda. The establishment and expansion plans of Maale Adummim

and their human rights ramifications,

http://eng.bimkom.org/Index.asp?ArticleID=142&CategoryID=125

Bollens S, 2000 On Narrow Ground: Urban Policy and Ethnic Conflict in Jerusalem and Belfast

(State University of New York Press, Albany, NY)

Brenner N, Elden S, 2009, Henri Lefebvre on state, space, territoryInternational Political

Sociology3 353377

BTselem, 1999, On the way to annexation. Human rights violations resulting from the

establishment and expansion of the Maaleh Adummim settlement,

http://www.btselem.org/english/publications/index.asp?TF=08

BTselem, 2011, Settlement population, XLS,

http://www.btselem.org/download/settlement_population_eng.xlsBTselem, Weizman E, 2002, Jewish settlements in the West Bank. Built-up areas and land reserves.

May 2002, http://www.btselem.org/Download/Settlements_Map_Eng.PDF

Castells M, 1983 The City and the Grassroots. A Cross-cultural Theory of Urban Social Movements

(University of California Press, Berkeley, CA)

Coon A, 1992 Town Planning Under Military Occupation (Dartmouth Press: Aldershot, Hants)

De Jong J, 1997, Metropolitan and Greater JerusalemJan 1997,

http://www.fmep.org/maps/jerusalem/metropolitan-and-greater-jerusalem-jan-1997

Demant P, 1988Ploughshares into Swords. Israeli Settlement Policy in the Occupied Territories,

19671977PhD thesis, Universiteit van Amsterdam

Don Yehiya E, 1994, The book and the sword: the nationalist yeshivot and political radicalism in

Israel, inAccounting for Fundamentalism: The Dynamic Character of Movements

Eds M E Marty, R S Appleby (University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL) pp 262300

Dumper M, 1997 The Politics of Jerusalem since 1967(Columbia University Press, New York)

Efrat Z, 2003 The plan, inA Civilian Occupation. The Politics of Israeli Architecture Eds R Segal,

E Weizman (Babel and Verso Press, London) pp 5978

-

7/28/2019 Israel Settlements en Jerusalen Palestina

18/20

514 M Allegra

Eldar A, Zertal I, 2007Lords of the Land: The War Over Israels Settlements in the Occupied

Territories, 19672007(Nation Books, New York)

Faludi A, 1997, A planning doctrine for Jerusalem?International Planning Studies2(1) 83102

Feige M, 2001,Jewish settlement of Hebron: the place and the other GeoJournal53 323333Feige M, 2002, Do not weep Rachel: fundamentalism, commemoration and gender in a West Bank

settlementJournal of Israeli History21(1) 119138

Feige M, 2009 Settling in the Hearts. Jewish Fundamentalism in the Occupied Territories (Wayne

State University Press, Detroit, IL)

Felner E, 1999 Apartheid by any other name. Creeping annexation of the West BankLe Monde

Diplomatique November, http://mondediplo.com/1999/11/08israel

Fishman R, 1986Burgeois Utopias: The Rise and Fall of Suburbia (Basic Books, New York)

Flyvbjerg B, 1996, The dark side of planning: rationality and realrationalitt , inExplorations

in Planning Theory Eds S J Mandelbaum, L Mazza, R W Burchell (Center for Urban Policy

Research Press, New Brunswick, NJ) pp 383394

FMEP, 2010 Ten fastest growing West Bank settlements, 19942004,

http://www.fmep.org/settlement_info/settlement-info-and-tables/stats-data/ten-fastest-growing-west-bank-settlements-199420132004

Friedland R, Hecht R, 1996 To Rule Jerusalem (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge)

Friedman R, 1992Zealots for Zion: Inside Israels West Bank Settlement Movement(Random House,

New York)

Gazit S, 2003 Trapped Fools: Thirty Years of Israeli Policy in the Territories (Frank Cass, London)

Gordon N, 2008, From colonization to separation: exploring the structure of Israels occupation

Third World Quarterly29(1) 2544

Goremberg G, 2006 Occupied Territories. The Untold Story of Israels Settlements (I B Tauris,

London)

Haaretz, 2003, The price is right, 25 September,

http://www.haaretz.com/print-edition/business/the-price-is-right-1.101174

Haaretz, 2009, Israel plans to build up West Bank corridor on contested land 1 January,http://www.haaretz.com/news/israel-plans-to-build-up-west-bank-corridor-on-contested-

land-1.266848

Harris W, 1980 Taking Root: Israeli Settlement in the West Bank, the Golan and the GazaSinai

19671980 (Research Studies Press, Chichester, Sussex)

Hever S, 2010 The Political Economy of Israels Occupation. Repression Beyond Exploitation

(Pluto Press London)

Hobsbawm E, Ranger T (Eds), 1983 The Invention of Tradition (Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge)

Hochstein A, 1983Metropolitan Links between Israel and the West Bank(West Bank Data Project/

Jerusalem Post, Jerusalem)

ICBS, 2008 Statistical Abstract of Israel 2008 Israeli Central Bureau of StatisticsICBS, 2010 Statistical Abstract of Israel 2010 Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics

ICBS, 2011 Statistical Abstract of Israel 2011 Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics

Israel Environment Bulletin 1993, Environment Week, Summer 19935754 16(3),

http://www.mfa.gov.il/MFA/Archive/Communiques/1998/ENVIRONMENT%20WEEK

Israel Hayon, 2012, Jewish population in Judea and Samaria increases by 4.3 percent, census says,

15 January, http://www.israelhayom.com/site/newsletter_article.php?id=2676

Isaac R, 1976Israel Divided: Ideological Polictics in the Jewish State (Johns Hopkins University

Press, Baltimore, MD)

Jerusalem Post1978, Country-club suburb from pioneer start, 4 July

Jerusalem Post2009, Rivlin: no peace without E-1 building, 10 August

Jewish Agency, 2010 Maaleh Adummim,http://www.jewishagency.org/JewishAgency/English/Aliyah/Absorpton+Options/Municipal+and+Co

mmunity+Absorption/Maaleh+Adummim.htm

JIIS, 2008Jerusalem Statistical Yearbook 2007/2008 Jerusalem Institute for Israeli Studies and

Jerusalem Municipality, Jerusalem

-

7/28/2019 Israel Settlements en Jerusalen Palestina

19/20

The politics of suburbia 515

JIIS, 2010Jerusalem Statistical Yearbook 2008/2009 Jerusalem Institute for Israeli Studies and

Jerusalem Municipality, Jerusalem

Khamaisi R, 2008, Between competition and integration: the formation of a dislocated and distorted

urbanized region in Jerusalem; inJerusalem and Its Hinterland(The International Peace andCooperation Center, Jerusalem) pp 6886

Klein M, 2007, Lords of the land: the settlers and the State of Israel, 19672004 (review article)

Jewish Quarterly Review97(3) 125127

Kotek J, 1999, Divided cities in the European cultural contextProgress in Planning52 227237

Lefebvre H, 1991 The Production of Space (Blackwell, Oxford)

Leitersdorf, undated, Maaleh Adumima new town developed by the Ministry of Housing,

Thomas Leitersdorfs personal archive, Tel Aviv

Lustick I, 1988For the Land and the Lord: Jewish Fundamentalism in Israel(Council on Foreign

Relations, New York)

Lustick I, 1993 Unsettled States, Disputed Lands : Britain and Ireland, France and Algeria, Israel

and the West BankGaza (Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY)

MERIP, 1977, Israel settlement policy, Middle East Research and Information Project,MiddleEast Report59 1823

Mitchell T, 1991, The limits of the state: beyond statist approaches and their criticsAmerican

Political Science Review85 7796

Modarres A, Kirby A, 2010, The suburban question: notes for a research program Cities27

114121

Nasrallah R, 2008, Jerusalem and its suburbs: the decline of a Palestinian City, inJerusalem and

Its Hinterland(The International Peace and Cooperation Center, Jerusalem) pp 4752

Newman D (Ed.), 1985 The impact of Gush Emunim (Croom Helm, London)

Newman D, 1996, The territorial politics of exurbanization: reflections on 25 years of Jewish

settlement in the West BankIsrael Affairs3(1) 6185

Newman D, Herman T, 1992, A comparative study of Gush Emunim and Peace NowMiddleEastern Studies28 509530

PCBS, 2009Population, Housing and Establishment Census 2007, Palestinian Central Bureau of

Statistics, Ramallah

Peace Now, 2009, West Bank settlementsfacts and figures, June 2009,

http://peacenow.org.il/eng/node/297

Peace Now, 2011, Full settlements list, http://peacenow.org.il/eng/content/settlements-and-outposts

PLO, 2009, The Adumim bloc and the E-1 expansion area background paper, PLO, Negotiations

Affairs Department, http://www.plomission.us/index.php?page=resources

Porter L, 2010 Unlearning the Colonial Cultures of Planning(Ashgate, Farnham, Surrey)

Portugali J, 1991, Jewish settlement in the occupied territories: Israels settlement structure and the

PalestinansPolitical Geography Quarterly10(1) 2653

Possick C, 2004, Locating oneself as a Jewish Settler on the West Bank: ideological squatting andevictionJournal of Environmental Psychology24 5369

Pullan W, Misselwitz P, Nasrallah R, Yacobi H, 2007, Jerusalems Road 1 City11 176198

Rabin Y, 1995, Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin: ratification of the IsraelPalestinian interim

agreement, The Knesset, 5 October, 1995,http://www.mfa.gov.il/MFA/MFAArchive/1990_1999/1995/10/PM+Rabin+in+Knesset-

+Ratification+of+Interim+Agree.htm

Ravitsky A, 1996Messianism, Zionism, and Jewish Religious Radicalism (University of Chicago

Press, Chicago, IL)

Reichman S, 1986, Policy reduces the world to essentials: a reflection on the Jewish settlement

process in the West Bank, inPlanning in Turbulence Eds D Morley, A Shachar (Magnes Press,

Jerusalem) pp 8396

Reuveny R, 2003, Fundamentalist colonialism: the geopolitics of IsraeliPalestinian conflict

Political Geography22 347380

Rice C, 2005, Quartet Statement, 20 Sep 2005,http://www.mfa.gov.il/MFA/Peace+Process/Reference+Documents/Quartet+Statement+20-

Sep-2005.htm

-

7/28/2019 Israel Settlements en Jerusalen Palestina

20/20

516 M Allegra

Segal R, Weizman E, 2003, Introduction, in Occupation. The Politics of Israeli Architecture

Eds R Segal, E Weizman, A Civilian (Babel and Verso Press, London) pp 1926

Segev T, 2006, A bitter prize: Israel and the occupied territories Foreign Affairs85(3) 145150

Settlement Report, 1998, Settlement timeline Settlement Report8(3),http://www.fmep.org/reports/archive/vol.-8/no.-3/settlement-timeline

Sharkansky I, Auerbach G, 2000, Which Jerusalem? A consideration of concepts and borders

Environment and Planning D: Society and Space18 395409

Shlay A, Rosen G, 2010, Making place: the shifting Green Line and the development of Greater

metropolitan Jerusalem City and Community9 358389

Sprinzak E, 1991 The Ascendance of Israels Radical Right(Oxford University Press, New York)

Stern D, 1990, Ethno-ideological segregation and metropolitan development Geoforum21 397409

Tamir-Tawil E, 2003 To start a city from scratch. An interview with architect Thomas M

Leitersdorf, inA Civilian Occupation. The Politics of Israeli Architecture Eds R Segal,

E Weizman (Babel and Verso Press, London) pp 151162

Taylor P, 1994, The state as a container: territoriality in the modern world-systemProgress in

Human Geography18 151162The Guardian 2010, We were looking for a nice, peaceful place near Jerusalem , 25 September,

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2010/sep/25/west-bank-settlers

Thorpe M (Ed.), 1984Prescription for Conflict. Israels West Bank Settlement Policy (Foundation for

Middle East Peace, Washington, DC)

Weizmann E, 2002, The politics of verticality: roadsover and under,

http://www.opendemocracy.net/ecology-politicsverticality/article_809.jsp

Weizman E, 2007Hollow Land: Israels Architecture of Occupation (Verso, London)