Imagine - · PDF file3 Imagine there’s no heaven, it’s easy if you try, No hell...

Transcript of Imagine - · PDF file3 Imagine there’s no heaven, it’s easy if you try, No hell...

This publication is about a possibility.

Imaginewhat might happen if we really believed in God’spower to transform people’s lives?

Imaginewhat might happen if we were gripped with joy andgratitude by the difference Christ’s love has made toour lives?

Imaginewhat might happen if we looked around at thepeople we spend our days with and asked God:how do you want me to be good news to thesepeople today?

Imaginewhat might happen if we rediscovered ourresources in Christ and learned to bechannels of lavish blessing to our fellowcitizens, wherever we meet them?

Imaginewhat might happen if we createdChristian communities where peoplewere safe to be who they are, andencouraged to become all that theycan be?

Imagine all this in a country where theoverwhelming majority has rejected theChurch, disregarded Christianity and doesn’teven know why Easter is a public holiday.

Imagine that.

1. Imagine

2. Can you make a difference?

3. The UK in a state: opportunity knocks

4. The Church in a state

5. The road to irrelevance

6. The great resource

7. Let my people go

8. Learning to live, living to learn

9. Your country needs you

10. Your turn to speak

Produced in partnership with

Mark Greene is the executive director of the London Institute forContemporary Christianity. Previously he was vice-principal andlecturer in communications at London Bible College, where he alsostudied theology. Before that he spent 10 years in advertising withOgilvy & Mather in London and New York. He has written andspoken widely on workplace ministry and contemporary culture.

The London Institute for Contemporary Christianity was founded in 1982 byJohn Stott to equip Christians to make a radical difference for Christ in thecontemporary world - in their workplaces, neighbourhoods, schools andcolleges. LICC today acts, nationally and internationally, as a champion forwhole-life discipleship and for mission ‘where you are’. The multi-disciplinaryteam provides a wide range of resources for Christians, leaders, theologicalcolleges and Christian agencies through courses, conferences, publications,videos, email and the web. To find out more, contact:LICC, St Peter's, Vere St, London W1G 0DQ. Tel: (020) 7399 9555 Fax: (020) 7399 9556 Email: [email protected] Website: www.licc.org.uk

Imagine

Imagine

3

Imagine

2

Evangelical Alliance186 Kennington Park RoadLondon SE11 4BTTel: (020) 7207 2100Email: [email protected] Website: www.eauk.org

© Mark Greene/LICC 2003

This publication calls on the BritishChurch to focus together to develop astrategy to reach out to the people ofthe UK. It argues that, by and large,the Church has not fully envisioned,equipped, nor supported its people toreach out to others where they are, andthat we have often failed to give ourexisting members a compelling visionof what it means to live as whole-lifedisciples of Jesus in the modern world.

Opportunities abound, however.Imagine if the people we already havein church were envisioned, equippedand supported. Imagine if we weretaught how to be good news to thepeople with whom we already haverelationships. Imagine if we grasped theimpact that showing and sharing thelove of Christ could have.

Two key areas of change arenecessary. First, our churchcommunities need to become muchmore open, interactive, personal andexpressive - easier places to come to,easier communities to belong to.

Second, we need to return to Jesus’instruction to ‘make disciples’, tobecome lifelong learners andpractitioners in learning communities -communities that are focused onequipping people to go where thosewho don’t know Jesus are. This willrequire a radical shift in pastoraltraining, in current pastoral practice

and in the readiness of individualChristians to commit themselves to thedisciplines of lifelong Christianlearning.

In the previous decade, churchleaders tried to address lots ofquestions: How can we reach theyoung? How do we grow a localchurch? How can we preach moreeffectively? How can the churchminister to the poor? How can wecommunicate Christian values in themedia? These are important questions.But how we answer them might changeradically if we had a clear overallstrategy for reaching the UK, and aclear sense of how individuals,churches, para-church organisationsand denominations might worktogether towards this goal. Right now,we don’t have a plan. We need one.

Lots of ways forward might besuggested, not least taking a long, hardlook at the Book of Acts. Obviously,this short publication can’t explorethem all, but it does analyse the stateof the UK, the state of the Church andthe relevance of the Gospel to the UKtoday. It also suggests where the workof sharing Christ needs to be pursued,by whom and in what way. It doesn’toffer a quick-fix solution, but it doesoffer a focus, and explores theimplications of that focus for individualChristians and for our churches.

4

Of course, the UK is hugely diverse:racially, ideologically, economically.Similarly, the Church is diverse in itsapproach to the Bible, its forms ofworship, its teaching, its pastoral care,its cultural engagement. Nevertheless,the overall values driving British cultureare common to every region, and theoverall task of the Church is the sameeverywhere. Can we identify some keysteps that might radically transform ourcapacity to show and share Christ withour nation?

Surely we can. Indeed, the goal ofthis publication is not to itemise theChurch’s past errors, but rather to seewhat we can learn from one anotherand contribute to God’s purposes forthe UK.

Your turn to speak‘Sermons,’ according to onecommentator, ‘are the pastor’s turn tospeak.’ This statement assumes that thepeople would have their say too.

This publication’s primary purposeis to act as a catalyst for a debate.What would help you to make adifference where you are? What wouldhelp us to reach the UK? What sort oflong-haul strategy is needed for theChristian community to reach out tothe nation? Naturally, such a debatewill involve leaders from across avariety of different denominations andcontexts. But those leaders do need toknow what the people of God think. Soplease complete the questionnaire onthe web or at the end of thispublication. It is vital that you haveyour say.

This process should help each of usto see how we can make a differencefor Christ, and give us all a clearer ideaof how we can work together to makea difference.

‘Would you tellme, please,

which way Iought to gofrom here?’said Alice.

‘That dependsa good deal on

where youwant to get to,’

said the Cat.From Alice in Wonderland

by Lewis Carroll

In much of the developing world, Christianity is flourishing. Inthe UK, it is withering. Today, only around 7.5 per cent ofBritish people go to church once a month or more. That’s

down from 9.5 per cent in 1990, and 10.9 per cent in 1980. Thismay be bad news for the Church, but it is a tragedy for thepeople who don’t know Jesus. The key issue is not the survival ofan historic institution, but the eternal destiny and presentwellbeing of 59 million people. Can we make a difference?

2

Imagine

What is the state of the nation weare seeking to reach?

This process should help each of us to seehow we can make a difference forChrist, and give us all a clearer

idea of how we can worktogether to make a

difference.

Imagine

5

Can you make a difference?

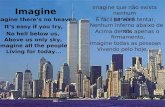

3Imagine there’s

no heaven, it’s easy if you try,No hell below us,

above us only sky.

From ‘Imagine’ by John Lennon

Britannia’s children, however, werenot dancing triumphantly into the newmillennium, but tiptoeing in, unsurethat we would be able to create a bravenew world in which we could, inLennon’s words, ‘live as one’. The songhad touched a nerve. It probably wasn’tLennon’s dream of a God-free, socialistparadise that swung votes. Rather itwas the music’s gentle, melancholicmood and the general yearning of thelyrics for a better life, a better world, abetter tomorrow.

Lennon believed that a worldwithout God would be a happier place. But what the 20th century proved waswhat Nietzsche predicted: as societiesmove away from God, they don’t gethappier, they get unhappier; they don’tget more loving, they get more selfish.

The UK is no exception. Christianityhas been rejected, and we are not anyhappier for it. Indeed, after all themyriad of positive changes of the past40 years, three things are clear:� The UK has rarely, if ever, been sodepressed and directionless.� The individualistic values that aredriving our society are enormouslypowerful, but they are not deliveringthe satisfaction people crave. � A society that can’t meet its people’sneeds is ready to hear good news thatmight.

We’ve never had it so sadThe UK has the highest rate of teenagepregnancy in Europe, the highest rateof youth crime, the third highest rate

of divorce. We have a growing drugproblem and a massive drink problem.And you can’t blame unemployment -the UK has one of the lowest rates inEurope. In fact, we work more hoursper week than any other EuropeanUnion nation, and commute thelongest. Not surprisingly, this has had anegative impact on the quality of ourrelationships - with partners, childrenand friends. We have less time and lessenergy. The number of days the Britisheconomy loses to sickness has doubledin the past seven years, and stress anddepression abound. There are nowsome 12 million of us on anti-depressants - more than a quarter ofthe adult population.

Overwork, however, is not the onlymajor factor. Behind these statistics liesthe fact that we have lost our sense ofnational identity and purpose, and this isreflected in the increasing disillusionmentwith politics. To the public at large, andto the young in particular, none of themajor political parties seems to offer anycompelling sense of national orindividual purpose, or hope. If there isno big idea to bind us together, nogrand purpose to pursue, no shared setof values we really agree about, it ishardly a surprise that people becomemore individualistic and more self-centred, more concerned about theirrights and less about their duties.

Prime Minister Tony Blair, speakingin 1995, expressed it thus: ‘We enjoy athousand material advantages over anyprevious generation, and yet we suffer

What is the state of the nation that we are seeking toreach? In December 1999, ‘Imagine’ was voted the UK’ssong of the millennium. It seemed, at first glance, to be

a surprising choice. After all, most of the people who voted for‘Imagine’ were not even alive when it was first released in 1970.Besides, at the dawn of a brand new millennium, wouldn’t youexpect something more upbeat and celebratory?

a depth of insecurity and spiritualdoubt they never knew.’

The situation has not improvedsince then. In the light of its 2002census, the youth culture magazine TheFace wrote: ‘If identity crisis is a formof madness, then Young Britain 2002 isa schizoid manic-depressive withbombsite self-esteem. Our status as themost boozed-up, drug-skewed,pregnancy-prone wasters in Europe ispretty much unchallenged.’

Certainly, our technologies havemade us better connected - by car, jet,phone, text and the web - but we aremore fragmented. We know morepeople, but have fewer friends. We lead‘spider lives’, as the Henley Centre putsit: we skitter along the threads of ourworldwide webs, picking up all kinds ofdelicacies, but we can’t find a place torest, nor any source of genuinenourishment or intimacy. People todayhave a million different options toexplore, but no strong set of values tohelp choose which one might be best.

The new opiate The only thing keeping this show onthe road is the brilliance and variety ofour leisure options. Entertainment isthe opiate of the masses, and we aredistracted from reflective thought andradical action by the power, creativityand pervasiveness of our media.Increasingly, our ‘hope’, what keeps usgoing, is the expectation of the nextepisode of EastEnders. And ouridentity is to be found in the logos onour clothes. Consumerism - the beliefthat the key to identity and a sense ofbelonging is to be found in thepurchase and the display of materialthings - is the religion of our time. It isa formidable foe.

The advertising line, ‘Life is full ofenough embarrassing moments, don’tlet your mobile be one of them,’ is

absurd. Nevertheless, the reality is thatthe ‘wrong’ mobile can be a profoundthreat to an individual’s sense of self-esteem. As one 12-year-old Christiansaid to her Christian parents: ‘If youdon’t buy me the right mobile, don’tbuy me a mobile at all.’ Indeed, thehighest level of absenteeism in manyschools occurs on non-uniform day. Thereason is simple: kids who don’t havethe right gear, don’t turn up. They fearridicule and rejection by their ‘friends’.

Despite what Margaret Thatcheronce famously said, there is such athing as society, but you need the rightproducts and logos to belong. Logosare the idols of our time. They rule ourhearts, but they do not satisfy them.

Still searchingInterestingly, though most people haveturned away from Christianity, theyhave not, on the whole, consciouslyreplaced it with an alternative set ofideas that gives them a satisfying senseof identity and purpose. Many peopleare still searching for some kind ofspiritual reality, for some centre to theirlives. We see this in theexperimentation with a whole host ofNew Age and Eastern practices, and inthe increasing interest in witchcraft andthe paranormal. ‘Mind, Body, Spirit’sections in high-street bookshops are nowgiven more shelf space than ‘Religion’.

Though some are still searching,others have given up believing thatthere is anything out there worthfinding. For example, back in 1995, the18-year-old Emma Forrest wrote this inher Sunday Times column: ‘At 18 weare so sophisticated that leaving schooldoesn’t move us. The subconscious fearis not of adulthood, of success orfailure, but that nothing else will moveme either.’ This profound sense of thepointlessness of the search isincreasingly common.

6

Imagine

Can we answer thequestions ‘Britannia’now poses?

Logos arethe idols

of our time

Opportunity knocksSo, why might now be a fertile seasonfor the Gospel? Because we are livingin a culture that cannot provide ananswer to the fundamental questionsabout meaning and purpose. And aculture that cannot answer its ownquestions is a culture open to ananswer.

Ultimately, of course, we know thatall human beings yearn for a restoredrelationship with God, for a bridgeback across the chasm that sin hashewn. But different societies, indifferent circumstances, pose differentquestions. Can we answer the questions‘Britannia’ now poses?

The UK in a state: opportunity knocks

8

Imagine

Imagine

9

4 The Church in a state

It’s pretty easy to criticise the Church in the UK. In fact, it’s soeasy, almost everyone does it. The purpose here, however, isnot to examine the range of criticisms levelled at the Church,

but rather to try to explore the major underlying problems thathave inhibited the communication of Christ in the UK. Three points emerge that we will look at in greater depth later.

� It is not primarily the world’s valuesthat have prevented the Church fromreaching out effectively, it is theChurch’s values. � The problem with Church culture isnot that it is irrelevant to those outsidethe community, but that it is not anauthentic expression of the culture ofthe people in it. � The primary evangelistic problemthat the Church faces is not theresistance of those who don’t believethe good news about Jesus, but thefailure to envision, equip and supportthose who do.

The effective Church First, it is important to remember thatnot all churches are in decline. Churchattendance is growing in one in fiveAnglican dioceses, and Black-majoritychurches are flourishing.

Second, the church remains anenormous force for good in ourcountry. Indeed, look around manyneighbourhoods and ask yourself:� Who is running drop-in sessions for

isolated and often lonely mums?� Who is running a lunch club for the

elderly?� Who is providing an after-school

haven for latchkey kids?� Who is reaching out to the local

home for those with disabilities?� Who is providing kids’ holiday clubs?� Who is running a homeless centre?� Who gives most to the poor

voluntarily?The answer is often the people of

the local church. No one contributes

more to this society voluntarily thanlocal churches and the pastors who leadthem. And it is a contributionincreasingly recognised by both centraland local governments. A BristolUniversity survey showed that, overall,Christians are three-and-a-half timesmore likely to do something helpful forsomeone outside their immediate familythan the general population. If ‘all youneed is love’, then, in the neighbour-hood at least, love often abounds.

Spitting image?Nevertheless, the Church in the UK hasa terrible image. From the benign butineffectual Reverend Timms in PostmanPat, to the benign but at least red-blooded Vicar of Dibley, the image ofthe Church has been ever thus.

The Church would be well advisedto pay more attention to its mediacommunications, but the UK will not bewon by a series of high-profileadvertising campaigns, nor throughgreater presence on the media, desirablethough that is. In the long term,substance matters more than image,and relationships more than TVprogrammes. Similarly, ‘customersatisfaction’ is more potent than a slickslogan, and word-of-mouth testimonymore powerful than TV commercials.

Alas, many of the Church’s currentcustomers are far from satisfied.

Friendly fireThe national Church is criticised by itsleaders and its members for its pooradministration, and for its failure to

Power for lifeWe know Christianity works. And itworks not only because Christ is thetruth, but because Christ works in aradically different way to the othermajor religions. Other religions expectchanges in behaviour to lead to achange of heart - they work from theoutside in. Christ works from the insideout: ‘Therefore, if anyone is in Christ,they are a new creation. The old haspassed, the new has come’ (2Corinthians 5:17). We have a newnature and ready access to the HolySpirit to help us lead the life that Christcalls us to. The Gospel has the powerto save, to transform and to sustain.

One way in a multi-faith society Making the case that Christianity is theonly true way is more challenging in amulti-faith, multi-cultural society.Many Christians have lost confidence inthe Gospel. We may be able to confessthat Jesus is ‘my lord’ but do we reallybelieve that he is The Lord - the onlyway to the Father?

In reality, the historical,

circumstantial and textual evidence forthe life of Christ and His resurrectionare entirely robust. Christianity is notonly intellectually coherent, but in itsunderstanding of the loving nature ofGod, the potential of intimacy withHim, and the benefits of salvation inthis life and after death, it need fear nocomparison with the offerings of any ofthe major faiths.

Furthermore, it is important toremember that while a Muslim imamwill not welcome the conversion of anyof his community to Christianity, he

understands the claim to exclusivetruth. The Koran is clear about the dutyto seek the conversion of the ‘infidel’and clear about the eternalconsequences of not acknowledgingMuhammad as Allah’s final prophet.

Nevertheless, the liberal humanistestablishment jumps to Muslims’defence, as if a more robustlyconversionist Christian Church is athreat to social harmony, public orderand world peace. Their apparentaltruism conceals the truth that the realthreat is to their belief - the belief thatthere is no absolute truth, a creed thatbrands anyone who claims to know‘The Truth’ as arrogant and intolerant.

It is vital to see this. Obviously,Christians should try to reach out tothose of other faiths, yet the greatestchallenge in the UK is not from otherfaiths but from the individualistic,consumerist values of our media-drivenculture and the de facto atheism thatunderpins it.

Nevertheless, if the way of Christ isso superior, why haven’t we succeededin communicating it more persuasively?

And I’d join the movement,

If there was one I could believe in.

Yeah, I’d break bread and wine,

If there was a church I could receive in.

From ‘Acrobat’, Achtung Baby, by U2

In this directionless culture, could a life as a Christian have some great purpose?

In this cynical culture,could being a Christian give me an outlet for my energy, my passion, my enthusiasm, my yearning to create a different world?

In this spin-driven culture,is this Christian life really real?

In this high-tech culture,could knowing Jesus satisfy my yearning for awe, for some taste of the beyond, some fragrance of the transcendent?

In this abrasive society, could Christian communities be safe havens to bring my brokenness, my hurt and my loneliness?

In this glitzy, powerful, in-your-face culture,could Christ give me the power to live differently?

Imagine a way of life that could offer all that.

speak out on major social andeconomic issues - though it does. It iscriticised for its failure to engage withgovernment, the media, the educationalestablishment - though it does.Nevertheless, it is true that, over thepast 20 years, theChurch has rarelyhad a strong,effective publicvoice.

The criticism ofthe Church goesbeyond centralleadership to itsperformance at thelocal level. Here it iscriticised for itsfailure to reachchildren, teenagers, singles, marrieds,the middle-aged - essentially everyoneexcept the elderly. It is criticised for itsfailure to address the needs ofemployed women, its failure to attractmen, its failure to provide a communityof acceptance for non-practisinghomosexuals, and its flight from thearts. Church structures are criticised forbeing inflexible, and too hierarchical.Preaching is criticised for its irrelevanceto daily life, and worship services inmany churches are not merelyunattractive to those outside theChurch but are often excruciatingly dullto those within it.

These criticisms reflect a deep crisis.And they come not just from perennialwhingers or from people disappointedthat there are very few hymns with‘hip-hop’ arrangements, they comefrom committed people. And they oftencome from committed people inchurches that are not only full butgrowing and widely perceived to besuccessful. In sum, there is a growing

concern that the local church is failingto meet the legitimate needs of itsmembers, never mind reaching out tothose on the fringe and beyond.

Of course, Christians are not calledto preach the Church but to preach

Christ and HisGospel. Nevertheless,the state of theinstitutional Churchand of individualchurch communitiesoften acts either asa magnet or as adeterrent to theGospel.

Furthermore, theChurch, as thecommunity of

believers, is meant to play a crucial rolein envisioning, equipping andsupporting Christians for the life Godintended, which includes sharingChrist’s love with others.

Three questions emerge� Does your church effectively helpyou to live in the contemporary world?� Is your church effective in preparingpeople for their role in mission? � Is your church an attractivecommunity to those who don’t yetknow Jesus?

Of course, there are some finechurches that are attractive to non-believers and effective in equippingtheir people for mission, but broadlyspeaking most people would answerthese questions ‘no’.

So what are the key underlyingcauses for the Church’s saggingperformance with existing members,and its lack of impact more widely?Let’s look first at the issue of Churchculture.

Is the Church amagnet or a

deterrent to theGospel?

10

Imagine

Imagine

11

So here’s a mystery: why is so muchof the way we do things in churchalien and off-putting to explorers,when during the week we appear tohave so much in common with them?

Perhaps the reason is because wehave created a community in which theway things are done does not reflectthe culture of the bulk of the people inthe Church. We cannot find ways toexpress ourselves. On the whole, we donot sing songs with tunes that most ofour people like. We do not use thelanguage that most people use. We donot address the issues that most peoplewant addressed. We do not give peoplean opportunity to ask the questionsthat are really on their minds. We donot create ways of meeting and waysof learning that resonate with the waysof meeting and learning ofcontemporary life.

The primary problem with Churchculture is not just that it is unattractiveto people who don’t know Jesus. Theprimary problem is that it is often notan authentic expression of the cultureof the people in the Church - it is noteven ‘our’ culture.

Of course, Christian culture shouldat root be a counter-culture. Christianculture is not intended to mimic anyparticular society’s culture. There oughtto be things about Church culture thatan explorer finds alien.

But these ought to be things thathave their roots in a response to the

person of Christ, not in a false beliefthat 18th century rhythms and 18thcentury idioms are necessarily closest togodliness.

This is not to say that old songscannot be sung, that old rites cannotbe performed. Indeed, such songs andrites may well resonate with people’sdesire for a sense of the eternalcontinuity of the message, orencourage a sense of the transcendent.

Nevertheless, in every generation weneed not only to pass on the best ofthe past, but also to connect to thepresent and allow new songs, new waysof learning, new ways of relating andnew ways of making decisions to findexpression.

Whole-loaf discipleshipFurthermore, Church culture hassometimes presented a limited view ofwhat it means to be human - and isoften perceived to be withoutspontaneity, freedom of expression, funand the enjoyment of the materialworld. Christ came to give us ‘abundantlife’, and it is each Christian’s calling toexplore, and help others to explore, theimaginative possibilities of thatabundant life in Christ.

Christ’s transforming Spirit isintended not only to affect everythingwe do but all our being - mind, body,emotions, will, spirit - like yeastpervading the whole loaf. Whole-loaf

Christianity rejoices in the senses - inthe fragrance of a rose, in theliberating joy of moving limbs in sportand dance, in human expressionthrough the arts.

Whole-loaf, whole-life Christianityis honest, open, vulnerable. It does notcensor the agony of brokenrelationships, the bewilderment ofunanswered questions, the struggle ofwork, the scandal of death, the impactof evil on ourselves and those aroundus. In sum, whole-loaf, whole-lifeChristianity embraces the wonders andgriefs of humanity in all its fullness inGod’s world.

As LICC’s Brian Draper puts it: ‘Weneed to be more Christian in the world,and more human in the Church.’

Too often Church culture looks tobe life-denying, not life-affirming. TheUK needs both to hear the message ofChrist and to see the power of Christworking itself out in the authenticityof people’s lives.

If we create an overall Churchculture that is relevant and genuinelyenriching for our own people, we willcreate a culture that will be much morerelevant to many who don’t yet knowChrist. And we will give our ownpeople the joy and confidence thatknowing Christ really does make a difference.

How many roads didI travel before

I walked down onethat led me to you?

From ‘Holy’, Woven & Spun,by Nicole NordermanThe culture block

Most Christians have a very good grasp of UK culture -they live in it. They wake up in the morning, listen tothe radio, read newspapers, go to work, are managed,

trained, motivated in particular ways, go shopping, play football,watch TV... the Church is in the world day in, day out.

The road to i rrelevance, part 1:

The road to i rrelevance, part 2:

The great divideWell, I never pray.

But tonightI’m on my knees, yeah.

I need to hear somesounds that recognise the

pain in me, yeah.From ‘Bittersweet Symphony’ by The Verve

Imagine

12

Traditional analyses of why the Church has failed to make animpact in the public sphere have tended to focus on awhole host of external factors - ideological, technological

and economic. All these factors are said to have combined in thepost-war period to relegate faith - all faiths - to the privatesphere. Faith was reduced to a matter for personal, privatereflection. It was put in a compartment. It had no place in thepublic arena, whether that be in work, school or politics. Faithceased to be the central organising principle that informed all oflife and all of life’s decisions and actions.

Private irrelevanceThe drop in the perceived relevance ofchurch teaching to daily life isparalleled by a drop in private prayerand daily Bible reading. Notsurprisingly, perhaps. After all, if mytrained pastor can’t show me how this8th century BC text applies to my 21stcentury AD life, what chance have Igot? In sum, Christians spend less timein focused reflection on God and lesstime with people who share theirworldview and their concerns.

Prayer, biblical reflection andmeeting purposefully with God’s people

are not the only ways to sustain arelationship with God, but they are notsimply traditional methods, they arebiblical methods. Of course, peopleoften say that it’s a matter of time:certainly more of us are workingoutside the home, and more of us areworking harder and commuting further.But we still have time.

Nor has Bible reading declinedsimply because reading has declined.People, particularly the middle classes,still read significant amounts. And theycertainly read what’s important tothem. Bible reading has declined

The problem with blaming socialforces for the decline of Christianity isthat it presumes that Christiandoctrines and lifestyle have no powerto resist their onslaught. In otherwords, we blame the world for thedemise of Christian values, and perhapsdon’t ask ourselves to what extent wemight be responsible. You can’t blamethe meat for going rotten - that’s whatmeat does. You blame the salt for notbeing there to preserve it.

Privatising ChristianityThe primary reason Christianity has hadlittle impact on the public sphere is notbecause the world has privatised theGospel, but because we have.

Research reveals that 47 per cent ofchurch attendees say that the teachingthey receive in their churches isirrelevant to their daily lives. When youprobe more deeply into where churchteaching is helpful, you discover thatchurch teaching is least helpful when itcomes to where people spend mosttime - home and work.

Helpfulness rating by life area(on a scale of 0-4, from least to most helpful)

Personal 2.57Church 2.12Home 1.83Work/school 1.68

Importantly, few people said thatthe problem with preaching andteaching was the preacher’s delivery orcommunication skills or even theirfailure to engage with the Bible(though this remains a concern). Thecore issue was the relevance of thematerial to people’s lives. The problemis not primarily one of form but ofcontent.

Overall, churchgoers are not lookingto be entertained, they are looking forwisdom for their daily lives. They wantto know how to live Christianly. Andthat is not being delivered.

This is not just a pity for them, butit is a tragedy evangelistically becausemillions of people in the UK arethirsting for practical wisdom for living.People may not be directly interested inthe Gospel, but many are interested inhow to choose a career, a partner, havea happier marriage, bring up childrenand manage debt.

This failure to deliver wisdom fordaily living applies to some of thefinest teaching churches in Britain. Onemember of such a congregation said:‘The teaching is excellent. It’s just veryhard to apply it to my life.’

Research shows that this failure tomake the connection between theWord of God and the world manifestsitself right across the denominations.

because we are not convinced that Godhas something essential andexhilarating to say to us about how tolive in His world. And prayer hasdeclined because we are not convincedthat it will make any difference to ourdaily lives.

We will not grow more effective forGod unless we grow more attentive toGod. And we will not grow attentive toGod unless we are convinced thatlistening makes a difference. Askyourself two questions:� Do I understand the relevance ofChristianity to my ordinary daily life?

The sacred-secular divide,which keeps

our day-to-daylives separate

from ourchurch lives,has led to

flawedtheologies ofChurch andoutreach.

� Do I seek God’s wisdom andsupport in my ordinary daily life?

For many Christians in Britain, theanswer is likely to be ‘no’. We may beconvinced that Christ makes adifference to our eternal destination,but does He make a difference to us inour day-to-day decisions?

So, even before we get to thequestion of whether the Church isequipping its people to share theGospel, we run headlong into thereality that many Christians simply donot see the compelling relevance ofChristianity to their ‘ordinary’ Christianlives. Why?

The great divideIt is certainly not that our leaders don’tcare about us, nor that they areincompetent. The key cause is theimpact of the sacred-secular divide onvirtually every aspect of church life.

The sacred-secular divide involvesthe pervasive belief that some parts oflife are not really important to God -work, school, sport, TV - but anythingto do with prayers, church services andchurch-based activities is.

It is because of the sacred-seculardivide that the vast majority ofChristians in every denomination feelthat they get no significant support fortheir work from the teaching, prayer,worship, pastoral or community aspectsof church life. It is because of thesacred-secular divide that over 50 percent of them have never heard asermon on work - something that theywill spend around 65 per cent of theirwaking lives doing for about 40 years.Quotations like this abound: ‘I teach inSunday school 45 minutes a week andthey haul me up to the front and thewhole church prays for me. I teach inschool 40 hours a week and no oneever prays for me.’

That’s the sacred-secular divide:praying for one part of a Christian’s lifebut not another; believing thatteaching in Sunday school for 45

minutes a week is more important toGod than teaching in school for 40hours a week.

It is because of the sacred-seculardivide that the Harry Potter novels havebeen so widely commented on byChristian leaders, but the choice ofliterature for the national curriculumhas been almost entirely ignored. Theprimary reason the Church has engagedso vigorously with the Harry Potterbooks is because of their setting in aschool for wizards and witches - the

setting raises issues about the ‘spiritual’realm of the occult, a realm the Churchquite rightly feels it should engage in.Meanwhile, back in the nationalcurriculum, kids are reading all kinds ofoften very fine literature: SamuelBecket’s Waiting for Godot or DHLawrence’s Sons and Lovers, forexample. And they are not just readingthem, they’re studying them hard,learning quotations, writing essays.Quite rightly. But are the children oftoday’s Church being equipped to use abiblical perspective to respond toBecket’s atheism or Lawrence’s view offree love? Are they being equipped torespond biblically to any other aspectof their curriculum?

To date, we, at LICC, afterconsiderable research, have not yet

been able to identify a single resourcefor youth workers that encouragesthem to help their young people thinkbiblically about their studies at school.The result is that, by default, our kidslearn very young that the 9-to-5 is notimportant to God. We have a leisure-time Christianity.

Leisure-time ChristianityThis continues on into universityeducation. Norman Fraser, formerly asenior executive with Universities andColleges Christian Fellowship (UCCF),the UK’s largest student ministry,lamented: ‘I could practically guaranteethat you could go into any ChristianUnion in Britain and not find a singlestudent who could give you a biblicalperspective on the subject they arestudying to degree level.’

That’s the sacred-secular divide -not expecting Christians to thinkChristianly about what they’re doing inthe world.

The sacred-secular divide haspromoted a leisure-time Christianity,not a 24/7, whole-life Christianity.Evenings and Sundays are God’s, 9-to-5is the world’s. And so the sacred-seculardivide leads adults to believe that reallyholy people become missionaries,moderately holy people becomeministers, and people who are notmuch use to God get a job. Bahhumbug.

God is the God of all of lifeChrist claims all of our lives - our lifeat work and our life in theneighbourhood. If we want to see theUK won for Christ, the sacred-seculardivide must be expunged from everythought and prayer. After all, most ofour interactions with the 90 per cent ofpeople who don’t know Jesus occur onthe ‘secular’ side of the great divide -the side that we and our communitiesrarely pray for, or consider vital to God.

The sacred-secular divide ispervasive and has contributed to flawedtheologies of the Church, of the role of

the minister and of outreach. Flawed view of the ChurchIn Matthew 5, Jesus gives the disciplestwo similes to describe the people ofGod, the Church: the light on a hill,and salt. Here light is primarily animage of the Church gathered together.What does the community of Christlook like to the watching world? If welove one another, John records, allpeople will know that we are Jesus’disciples. The loving relationshipsbetween Christians are a testimony tothe world of the transforming power ofthe One we follow.

Second, the people of God arecompared to salt scattered in the world.This is a call to individual Christians towork out their faithfulness in theworld. But does the individual Christiancease to be a member of the Churchwhen they are out in the world? Notaccording to the Bible.

In reality, however, the averageChristian does not feel that they go towork as the individual representative ofthe body of Christ, supported in prayerand fellowship by other Christians. No,the average Christian believes they goto work alone.

The impact of the sacred-seculardivide has been to see the ‘churchgathered’ as more important to missionthan the ‘church scattered’. Indeed, thevast majority of church evangelisticinitiatives have tended to bedomestically focused and pastor-centred. The goal becomes to get non-believers into a domestic or churchcontext to listen to a pastor, live or onvideo, as opposed to get the non-believer into relationship with Christthrough a relationship with a Christian.We spend an enormous amount ofenergy trying to work out how to makethe church a place people will want tocome to, and little energy working outhow we can train Christians to make themost of the places they already go to.

Flawed view of the pastor’s roleThe sacred-secular divide also manifests

itself in a flawed understanding of therole of the pastor. In Ephesians 4:11-12, Paul writes: ‘It was He who gavesome to be apostles, some to beprophets, some to be evangelists andsome to be pastors and teachers, toprepare God’s people for works ofservice, so that the body of Christ maybe built up.’

The job of the pastor is to preparehis or her people for their ministry -which is likely to involve contextsoutside a one-mile, or even three-mile,radius of the local church. Indeed, if wethink not so much about where people

are at 11 o’clock on Sunday morning,but where they are at 11 o’clock onMonday morning, then we will, inalmost every case, get a much clearerpicture of their potential for mission.The question is not ‘How can I use thisperson in the local church?’ but ‘Howdoes God want to use this person?’

Unfortunately, very few pastors seetheir role in this way - otherwise theywould have been equipping theirpeople to be effective for Christ in workand school. The sacred-secular dividehas, therefore, profoundly affected whodoes evangelism, in what contexts and

Imagine

14

Imagine

15

The key to mission is to equip Christians for wherethey are, not where they are not; for where theyhave relationships, not where they don’t.

The question isnot ‘How can I

use this person inthe local church?’

but ‘How doesGod want to

develop and usethis person?’

Imagine

17

The parable of the mustard seedshows us that little things can make ahuge difference over time, and canbecome welcome signs to the world ofa different way.

The parable of the yeast addsanother vital dimension: ‘The kingdomof heaven is like yeast that a womantook and mixed into a large amount offlour until it worked all the waythrough the dough.’ Yeast not onlypervades the dough, yeast transforms itinto something much tastier and muchmore satisfying - into bread. It takesjust 10 grams of yeast to turn a kilo offlour into bread. It’s not quantity thatcounts but impact.

The Christian is intended to be anagent of transformation in the world.We are not simply there to arrest decay,to add savour, to expose sin; notsimply there to show a different way.We are there to radically transform thesociety in which God places us.

Imagine that. Is that how you feel?Is that what your local Christiancommunity is helping you to become?

The key to mission and socialtransformation in the UK - and alsoglobally - is to equip Christians forwhere they are, not where they are not;for where they have relationships, notwhere they don’t.

The sacred-secular divide, however,has led to a situation where the bulk ofBritish outreach activity has ignoredwhere many people spend most of theirtime - at work, at school, at college -and focused instead on where they

spend less time and have fewerrelationships. For too long, we haveallowed the location of the churchbuilding and the expertise of the pastorto determine the scope of outreachactivity, rather than the location ofGod’s people and their potential.

1945 and all thatBack in 1945, the Church of Englandpublished a book called Towards theConversion of England. The section onevangelism came to this conclusion:‘We are convinced that England willnever be converted until the laity usethe opportunities for evangelism dailyafforded by their various occupations,crafts and professions.’

Many Christians baulk at such anarrow focus for outreach. Of coursethe neighbourhood is significant forthose with relationships in it, and it iseven more significant when‘neighbourhood’ is not only defined asthe context in which people havefriends but the context in whichschools, hospitals, shops and clubsoperate, in which the communityshapes itself. Still, the 1945 statementdoes not say that other contextscannot be fruitful; it simply states thatif the Church does not address thework context, then we will not win theUK. This makes instinctive sense.

Furthermore, the writers graspedseveral important points:� The key task force for mission is notprimarily the pastor, it is everyone else.There is one simple reason for this:

Never forget that ourgreatest assets walk out

of the elevator at theend of every day.

Advertising guru David Ogilvy of Ogilvy & Mather

Imagine

164

some 4.5 million people go to churchonce a month or more - but there areonly 37,000 church-paid pastors.� The basis for evangelism isrelational. The reason the laity arecrucial is not only numerical. It isbecause all the research points to thereality that relationships are a criticalfactor in the process of someonebecoming a Christian. The 4.5 millionpeople who attend church are probablyconnected to over 90 per cent of thepopulation of the UK. People maypoint to Alpha as the tool that ledthem into the Kingdom, or to aparticular sermon as a key moment, butit is usually relationships that drewthem into the Alpha group or theevangelistic meeting in the first place. � While people have relationships inall kinds of contexts in which theGospel can be planted - clubs, pubs,teams, on the web, on the train - theworkplace is where most Christians havethe highest number of ongoingrelationships.� The workplace is where Christiansare credible. Most Christians do a goodjob. Most have good relationships withtheir colleagues. And that makes themcredible to their colleagues.� The workplace is where Christiansare transparent. People can see thedifference Christ makes. People see usfail and succeed; lose our temper,control our temper; gossip, not gossip;go out of our way to shift the blame,accept responsibility when it’s ours.People see whether honesty andintegrity really matter to us or not.People see whether people really matterto us or not. They see whether Godreally matters to us or not. We can’thide.

Since the publication of Towardsthe Conversion of England, theworkplace has become, if anything,even more important to mission,because people have fewer significant

relationships elsewhere, and becausethe workplace is almost the last contextwhere people of different ages, socio-economic groups, ethnicities and life-stages have any significant, regularcontact. You don’t, for example, seemany 47-year-olds clubbing with 25-year-olds. But in the workplace, peoplefrom 16 to 65 can, and do, relate.

The importance of the workplacehas been grasped by an increasingnumber of leaders, but it has notbecome an active part of mostchurches’ strategic thinking. At root,the key point is not the importance ofthe workplace. The key point is torecognise the potential of everyChristian to make a difference forChrist where they are, to plant theGospel in the networks of relationshipsin which they spend most of their time.

Sadly, however, the Church’s heroesand heroines still tend to be ‘theprofessionals’ - people of extraordinarytalent leading extraordinarily fruitfullives in ‘full-time’ Christian work in

often unusual circumstances. This elitistmodel easily discourages the rest of us.We aren’t that smart, that brave, don’thave the gifts to be a preacher or apastor or even the faintest whisper of asense of call to some far-flung cornerof the globe. Is there no heroism in theordinary Christian life?

The reality is that day in, day out,‘ordinary’ Christians are doingextraordinary things in ordinarycircumstances - not only reaching outto friends and colleagues, but alsotransforming schools and city centres,working practices and productstrategies.

Certainly, in recent decades, therehas been some emphasis on ‘everymember ministry’, but this has beenpredominantly confined to ‘everymember ministry in the church’, andnot understood as ‘every memberministry where God leads’. It is the laitywho on the whole must do the work ofministry, witness and transformation.And it is the clergy who must take upthe task of envisioning, equipping andsupporting them in that role.

Let my people goIndeed, the moment you stop asking,‘How will the UK be won?’ and startasking the question, ‘Who will win theUK?’ the whole picture begins tochange. Suddenly the 7.5 per cent ofthe population who go to churchrepresents an enormous resource.

Never mind the Church’s ageingprofile. Never mind that we areprimarily middle class. That’s still oneperson in 13 in the population. Evenpresuming that as many as half ofthose people aren’t converted orcommitted, that’s still in 1 in 25.

The fact that a Christian in work orschool spends 40 hours a week or sowith, on average, 50 people representsa huge opportunity. The fact that a 23-year-old who likes dancing spends

Every generation tends to focus on particular metaphors forthe Christian life. In the 20th century, there was muchemphasis on ‘salt and light’ from the Matthew 5 passage.

Salt was popularly understood as an agent of preservation, asarresting decay and adding savour. Light was popularlyunderstood as modelling a different way and exposing evil. Butin Matthew 13 there is another pair of parables: the mustard seedand yeast.

Suddenly 7.5 per cent of the

population going tochurch represents anenormous resource:

that’s oneperson in 13.

6� � � � �

� � � � � � �

Imagine

184

eight hours a week in clubs representsa superb opportunity for relationshipbuilding. The fact that a housewifewith a child at a primary school has thescope to interact with up to 30 or sosets of parents for seven years suddenlylooks like an enormous opportunity tobuild relationships. The fact that a 70-year-old in a retirement home gets tomix 12 hours a day with 30 or 40 or50 other people of similar agerepresents a huge opportunity.

We have the people. And we havethem in place.

Re-invigorating the people of GodThis view of the potential of everyChristian to serve God where they are isnot just a missionary tactic, it is ascriptural truth. It not only has thepotential to see many people come toChrist, it has the potential to re-invigorate Christians.

At the moment, many Christians aretotally unaware of their potential toserve God where they are. They go towork, do a good job, try to be honestand dash home at the end of the dayto go to the prayer meeting or toinvolve themselves in some churchactivity, so that they can ‘do somethingfor God’ that day. They do not knowthat they have already served God. Theydo not know that whatever they do canbe done to the glory of God.

One woman I met put it this way:‘I’ve worked in the NHS for 17 years.And for many years I’ve wondered whatministry God had for me. About a yearago, I suddenly realised where Godwanted me: right here in the NHS. Andit has transformed my attitude to myjob. How sad it is that some people diewithout realising the ministry God hadfor them.’

If Christ isn’t relevant to Christians

where they spend most of their time,why should He be relevant to non-Christians where they spend most oftheir time? And if God isn’t relevant tous where we spend most of our time,why would He be relevant where wespend less of our time?

Furthermore, if we Christians don’t

live as if faith affects all of our life,then why should non-Christians believethat Christianity is relevant to all oftheirs? If explorers don’t see anydifference about us in our work time,then they will continue to believe thatChristian activities are merely ourpreferred way of spending our leisuretime - rather than the power plant ofour entire existence.

Transform where you areIn addition, the realisation that everyChristian can make a difference wherethey are opens up the possibility not

only of modelling the Christian way butof bringing the wisdom of Christ tobear on the way that things are done -in a school, hospital or business. Willthe priorities of the King who createdall have some impact on His createdorder? On what products we make,what games we play, what wages wepay, what hours we expect others towork and so on. The Christian in God’sworld has a mandate not only forverbal witness but also for socialtransformation.

Tragically, the 1945 document wasignored, perhaps because it would haveinvolved such a radical change in thewhole focus of church ministry. Orperhaps because, as one commentatorput it, the leadership put the Churchbefore the Church’s mission, put theinstitution before the institution’spurpose. It is a powerful temptation.The Church that puts the institutionbefore its purpose is as likely to befruitful as a dance studio that spendsall its money and time on the décorand sound quality, rather than teachingpeople to dance.

The people of God represent afantastic resource. And it is the failureto unleash that resource that is one ofthe Church’s key problems. Asmanagement guru Richard Farsonwrote: ‘The real strength of a leader isthe ability to elicit the strength of thegroup.’

How can we elicit the strength thatis in the Christian community?

What is God calling you to do? What supportdo you need from your church?

This is not teacher-centred thinkingbut disciple-centred thinking. Suchthinking does not begin with thequestion: ‘How do I tell you what Iknow?’ It begins by asking a questionlike: ‘How can I help you live for Christwhere you are?’ Or more specificquestions like:� What issues are you facing in your

life?� What is God calling you to do?� What knowledge do you feel you

lack?� What skills do you need to acquire?� What questions are you or your non-

Christian friends asking?� What resources would help you?� What support do you need from your

church?

What might we discover?We might discover that many of us arestruggling to integrate faith and life, tointegrate faith and work. We mightdiscover that we have a number ofunresolved questions ourselves, andthat we don’t feel confident to answerthe questions we imagine non-believersmight ask us.

We might discover that in manyareas we are thirsting for wisdom tolead our lives - to choose a career, alife-partner, to stay married, to bringup our kids, to manage our finances.

We might discover that many of usfeel guilty about our self-perceivedfailure to make a difference, and that

many of us don’t really know how toshare our faith, and that we aresuspicious of formulaic methods.

We might discover that the numberone barrier that most Christians feelprevents them from fulfilling theirpotential in Christ in mission andministry is fear - fear of their ownignorance, fear for their own self-esteem, fear of being embarrassed, fearof failure, fear of letting God down.

This doesn’t let any of us off thehook from seeking to share Christ. Weknow He expects His people to witnessto Him: ‘But you will receive powerwhen the Holy Spirit comes on you;and you will be my witnesses inJerusalem, and in all Judea andSamaria, and to the ends of the earth’(Acts 1:8).

Nevertheless, the contemporaryunderstanding of the concept ofwitnessing militates against mostpeople ever doing it. A witness is not

We would stand andrespond and expand

and include and allowand forgive and enjoy

and evolve and discernand inquire and acceptand admit and divulge

and open and reach outand speak up.

This is my utopia, this is my ideal, my end in sight.From ‘Utopia’, Under Rug Swept,

by Alanis Morissette

� � � � � � � � � � �

� � � � � �� � � � �

� � � � � � � � � � �

Imagine

19

7How can the Church create Christian communities that help

release the strength of the people where they are? � Askthe people. � Take their responses seriously. Of course,

leaders must set the overall direction, but good leaders also seekto find out what issues their people face, and what resources theyneed to face them. We must listen not only to the Word and theworld - double listening, as John Stott called it - but also toGod’s people - triple listening.

Let my people go

We have the people.And we have them in place.How can weunleash this

fantastic resource?

necessarily a preacher or a debater. Awitness is someone who tells otherswhat they have seen and experienced.

You do not need special training totell someone about the day you metthe love of your life. You do not needcoaching to tell someone about thesquash club you really enjoy. Theirresponse might well be to tell you thattheir squash club is better, or that theydon’t like squash because it is thepreserve of the middle-class toff, orthat tennis is a much better game.

The power of conversationWitness is not about winning anargument, but about having aconversation. And the great lack in thecontemporary Christian community isnot for a new generation of platformevangelists but for a community ofpeople who will talk about Jesus over acup of coffee.

If the model of witness is anevangelistic sermon or the debatingskills of the professional apologist, nowonder people don’t speak aboutChrist. The set-piece prepared talk isnot something you can usually deployin a pub, and a Gospel tract is a usefultool, but there is a time and a place.

Christianity might have begun tospread through the ancient worldthrough Peter’s sermon to a largeaudience, but it didn’t continue thatway. Indeed, we have record of veryfew such addresses to large audiences.Most meetings were in homes far toosmall to contain the averagecontemporary British congregation.And most ‘preaching’ would have bornlittle resemblance to the kind ofuninterruptible, monological addresswe are used to.

Nor did the Gospel spread throughtracts or mass media or through thepenetration of power structures andchannels of influence. It spreadthrough purposeful conversations,underpinned by prayer, empowered bythe Holy Spirit and validated by the

evidence of changed lives. However, even if witness is akin to

conversation, it is not a ‘natural’activity. Speaking about Christ needs tobe a spiritually empowered activity. Inthe Book of Acts, seven times thedisciples pray for boldness (NIV), orbetter translated, ‘freedom’ to speakabout Christ. No doubt they prayedmore often. Christian witness cannotbe reduced to a technique. It is morethan mere conversation, and it is notrisk-free. After all, many contemporarypeople have imbibed relativism and aremore likely to respond to even themost direct presentation by saying‘cool’, and going on to tell you howcrystals have changed their life.

If witness is at its simplest aconversation, this is not to say that wedo not have a responsibility to beprepared to answer people’s questions.Peter calls on all Christians to ‘alwaysbe prepared to give an answer toeveryone who asks you to give a reasonfor the hope that you have’ (1 Peter3:15). This former fisherman doesn’ttell us that we have to be able to takeon the professor of Buddhism atCambridge, but he does encourage usto be ready with a reason for the hopethat we have. We don’t have to winthe argument, we simply have to stateour case.

However, the vast majority ofpeople in our churches are not trainedfor the mission God has called them to.And there is little point in constantexhortations to ministry and witness ifsuch exhortations are not preceded byappropriate training and accompaniedby appropriate support. Tools likeAlpha and Christianity Explored arepowerful not just because they allowinterested people to explore theChristian faith, but because they givebelievers the opportunity to clarifytheirs. And that leads to much greaterconfidence.

There are things our people need tolearn. It’s time they were taught.

Is your churchmaking disciples?Are you closer to

Christ than youwere a year ago?

Go, therefore, andmake disciples of

all nations,baptising them in

the name of theFather, and of the

Son and of theHoly Spirit, andteaching them toobey everything

I have commanded you.

Jesus of Nazareth, Matthew 28:19-20

Learning to live,8The Church in the UK has a ‘convert

and retain’ strategy. Christ had a‘disciple and release’ strategy. Are wemaking disciples?

Disciple-making is altogether messierthan preaching and teaching. You canuse big meetings and programmes tohelp make disciples, but programmes arenot enough. The disciple-maker has toget into close relationship with thedisciple, has to be in a position to asksharp questions, to hold up the mirrorof God’s Word, to deal with theparticular pressures and temptationsthat the individual has.

Consider these questions:� Is your church making disciples?� Are you closer to Christ than you were a year ago? � In the last year, have you learned a significant amount about what it means to live as a follower of Christ in the contemporary world?

Most pastors have been trained toteach and preach and counsel. Disciple-making, however, is more than that, andmost pastors have not been trained inthe art of disciple-making. Generallypastors are not members of a homegroup or involved in mentoringrelationships with anyone in theirchurches. Nor do the structures in mostchurches lend themselves to disciple-making. In fact, pastors spend very littletime on disciple-making or passing onthe skills of disciple-making. They spend

most time on administration, crisiscounselling and visiting, preparing andleading services, and sermonpreparation.

The average pastor has a jobdescription that virtually no one in theircongregation would accept. The averagepastor is also, according to EvangelicalAlliance research, overworked, over-stressed and poorly paid. Many arethinking about leaving their job.

The average pastor is also gifted,committed to Christ and committed totheir people. We can’t ask them to doany more. But we must release them todo what’s really important.

Focusing on the fewJesus focused on the development of asmall group of people. Do we?

A pastor who gets involved indisciple-making will discover countlessbenefits for the wider congregation.They will develop relationships thatreveal the real issues on people’s hearts,uncover the questions that Christiansface in the world, see where they failand succeed, and discern why. It is fromsuch in-depth, purposeful relationshipswith the few that the many are oftenbest served.

We might ask ourselves: Have wemade any disciples lately? Is ourteaching building up outwardlyorientated disciples or just retainingconverts? Do our services contribute to

The Church’s goal is not to build the Church. Christ doesthat. The goal is to make disciples. That’s what Jesus spentmost of His time doing in His three years of public ministry.

That’s what Barnabas did with Paul and John Mark, and Paul withTimothy. Certainly, Jesus spoke to thousands but His focus wason 12. Christ made disciples and commanded us to do the same.

Imagine

21

building up disciples or do they simplyhelp maintain faith? Do we haveleaders willing to pursue a trainingagenda? Or a deep enough convictionthat communicating the Good News iscentral to discipleship?

Lifelong learningFurthermore, do our church patternsreflect the New Testament’s four-foldfocus on prayer, learning, relationshipsand communion? ‘They devotedthemselves to prayer, to the apostles’teaching, to fellowship and thebreaking of bread’ (Acts 2:42).

The Church of Christ is notintended to be a community whereteaching ‘happens’, it is intended to bea community that is ‘devoted toteaching’. It is intended to be alearning organisation. Most churchesaren’t, and never will be, as long asthere is an overwhelming emphasis onthe Sunday service.

You can do a lot of things in anhour or 90 minutes on a Sunday, butyou can’t do everything. We simplycannot expect any pastor/teacher,however gifted, to teach the wholeBible, all the major Christian doctrines,what to think about cloning, abortion,Saddam Hussein, EastEnders, Oasis,how to be a better husband/wife/friend/colleague/boss/parent, and howto have a greater impact in thecommunity, the local school, theworkplace - in 10 minutes or even 30minutes on a Sunday. And youcertainly can’t give everyone anopportunity to ask questions about theteaching they’ve had or explore theirdoubts.

There is nothing wrong withmonological preaching. But it is mosteffective in contexts where it iscombined with other means oflearning. We need more teaching, notless - particularly becausecontemporary people who come tochurch have learned less at school or athome about Christianity than people ofprevious generations. It can’t all be

done on a Sunday, nor should anyminister pretend it can be. Most peopleneed to be prepared to devotethemselves to active learning, asopposed to expecting to grow strongon titbits.

Three-tier learningOf course, different Church streams willrespond to the need differently. Muchof this has already been explored bythe cell church movement and by theG12 cell model, and there is anenormous amount to learn from whatthey are learning. However, the issue isnot about any particular form that theresponse takes, but the content weseek to deliver and the outcomes wehope to achieve. That said, amainstream Protestant church with aSunday service might operate with athree-tier structure, offering: � The opportunity to worship God inthe community of believers and hearthe Bible taught.� The opportunity to explore thetruths of the Bible in a context wherequestions can be asked and truthsapplied to contemporary life (eg homegroups, adult Sunday school andmidweek teaching).� The opportunity to developintimate, mutually supportiverelationships of accountability andservice with a small number of peoplein which there is the freedom to askand answer tough questions (egmodified home groups, prayerpartnerships, commuter groups on thetrain, workplace triplets, pre-clubbingsessions).

Essentially this was the pattern thatthe great Methodist evangelist andchurch-planter John Wesley developed.But the key is not the form he used inhis era, but rather for us to beimaginative about how we work withthe rhythms of contemporary life tohelp one another grow in discipleship.

Interestingly, many leaders arguethat people just won’t come todemanding activities. But that partly

A disciple is anactive, intentional

learner.

A disciple is anapprentice and a

practitioner - not just a student

of the Word but a doer of it.

A disciple is afollower of a

particular teacher.

A disciple isaccountable to

someone who knowsthem and helps them

to learn and growand live.

A disciple isoutwardly orientated,

focused on helpingothers learn

what it means to be a disciple.

depends on whether we mean 50 percent of a congregation or a group ofdisciples. Many people will give anevening to a learning activity - and do.What can we do with the time peoplewill give?

For example, in-depth Bible studiessuch as Precept and Bible StudyFellowship are growing in popularity.The reason for this is simple: you studythe Bible in depth, with life applicationin mind, and it helps you to lead yourlife. Busy commuter-belt professionalswill give hours to something thatdelivers, but resent every second spentin an anodyne, flaky group. This isn’tto say that the future lies in high-commitment, in-depth Bible studies,but it is to say that part of the futurelies in creating contexts in whichpeople are taught and learn how to livefor Christ today. And it is vital that thisis done in contexts where questions canbe asked, doubts expressed,disagreements voiced, difficultieswrestled with and commitmentssupported.

Until the advent of cell church, theprimary solution in the UK to thelimitations of monological Sundaypreaching was to start home groups.But research has suggested that over 70per cent of home groups had noconscious goals at all. Of those thatdid, half of them were not actuallygoals but lists of activities. That is, thegroup got together to do things - somecombination of study, prayer, worship,friendship - but without any idea ofspecific outcomes, eg to grow inparticular ways, to learn particular skillsor to encourage one another in specifickinds of ways.

Furthermore, the tendency was toimpose the same set of material onevery group, as if it were really the casethat one size fits all. This makes verylittle sense from a training and learningperspective because it fails to recognisethat people may be at different stagesin their Christian development and atdifferent stages in their lives, and

therefore have very different needs. Onesize fits one.

Disciples not only need a place tolearn, they need a place to be ‘real’, toallow the sharing of questions andintimate discoveries, struggles and joys,temptations and failures, sins and

triumphs. In sum, they needrelationships of support andaccountability. This can be achieved ina whole variety of ways - in triplets, inpairs, in cells - but such relationshipsare for many people one of the mostimportant keys to continued growth inChrist.

Better to start somewhereIf we are to create communities thathave disciple-making on their hearts, itwill probably require our leaders tolearn new skills. Just as we seek tocreate life-long learning among ourpeople, so we should take the life-longlearning of our pastors seriously.

Sadly, pastoral ministry is almost theonly profession left where peopleseriously expect someone to learnpretty much all they need to learn for alifetime in two or three years. We don’texpect that of a lawyer, an accountantor a doctor. And it is an issue thatevery church needs to take seriously.How can we ensure our pastors arelearning what they need to learn?What’s in our budget for that?

Pastors may well ask: How indeed

do we make disciples today? How canwe create congregations that aredisciple-making in orientation?

The answer is probably to startsmall and slow. No pastor can do allthe work of disciple-making, but apastor can begin somewhere and trainthose who will be able to share theload. Vitally, this will in time spread thesources of wisdom across thecommunity. Otherwise, the church runsthe danger of becoming far toodependent on the professional pastoralteam. They can’t do it all, and even ifthey could, they’re not meant to.

We have much to learn, andtrumpeting some new programme asthe solution to the Church’s woes willprobably be met with the scepticism itdeserves. Nevertheless, there are anumber of resources available.Furthermore, there may well be newmodels already being tried that willcome to light through the process thatthe Evangelical Alliance is leading.

Yes, we have much to learn, but wemust not allow the search for ‘greatmodels’ to inhibit starting the processof making disciples. A leader could doworse than simply asking theircongregation what would help them, orbeginning a group with a small numberof people with the express intent ofhelping them to grow.

The Church’s greatest resource is thepeople we already have. We must findways to help them go to those whodon’t know Christ - with generosity,humility and purpose.

Imagine if we all askedJesus the question:Lord, how can I make adifference for youtoday?Im

agine

224

We must not allowthe search for great models to prevent

us from starting theprocess of making

disciples

The UK is a post-Christian country and our families, friends, neighboursand co-workers need to hear the Gospel in terms they can understand.We cannot expect them to come to our church buildings, they mustlearn about Christ from us.

My conviction is this:

The UK will never be converted until we create open, authentic, learningand praying communities that are focused on making whole-life disciples

who take the opportunities to show and share the Gospel wherever they relate to people in their daily lives.

And we must pray.

Every Christian has this high calling: to be involved in the unfoldinghistory of God’s relationship with humankind.

Every Christian can be different where they are and make a differencewhere they are.

And every one of us is involved in the struggle to overcome evil withgood, to support the weak, to comfort the bereaved, to feed the poor, tocreate a country, a town, a workplace, a school, a home where the yeastof the Kingdom transforms all.

Let us pray.

Imagine if we created praying, supportive, learning communities thathelped us to grow in wisdom, in humanity and in generous love -communities that people wanted to come to. And communities thatenabled their people to go to others.

Imagine if we all asked Jesus the question:

‘Lord, how can I make a difference for you today?’

What difference would that make? Where might Jesus take us,individually and together? A very exciting place, which, in many cases,will be exactly where we already are. But it will look different as we beginto see it through His eyes. And even more different as He begins to work in it.

May it be so wherever you are. And in our land.

9Your country needs you

Your turn to speakPlease complete the questionnaire