IDF Diagnostic Clinical Care Guidelines for Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases 2nd Edition

-

Upload

maria-eduarda-viana -

Category

Documents

-

view

30 -

download

0

Transcript of IDF Diagnostic Clinical Care Guidelines for Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases 2nd Edition

Immune Deficiency FoundationDiagnostic & Clinical

Care Guidelinesfor Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases

40 West Chesapeake Avenue • Suite 308 • Towson, Maryland 21204 • www.primaryimmune.org • [email protected](800) 296-4433 • (410) 321-6647 • fax (410) 321-9165

Readers may redistribute this article to other individuals for non-commercial use, provided the text, htmlcodes, and this notice remain intact and unaltered in any way. The Immune Deficiency FoundationDiagnostic and Clinical Care Guidelines for Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases may not be resold,reprinted or redistributed for compensation of any kind without prior written permission from the ImmuneDeficiency Foundation.

SECOND EDITIONCopyrights 2008, 2009 the Immune Deficiency Foundation

D IAGNOST IC & CL IN ICAL CARE GU IDEL INES 1

The Immune Deficiency Foundation, in partnership with expert immunologists, developed thesediagnostic and clinical care guidelines to enhance earlier diagnosis, improve health outcomesand increase access to specialized health care and optimal treatment for patients with primaryimmunodeficiency diseases. The development and revision of the guidelines was funded by anunrestricted educational grant from Talecris Biotherapeutics.

The Immune Deficiency Foundation is the national patient organization dedicated to improvingthe diagnosis, treatment and quality of life of persons with primary immunodeficiency diseasesthrough advocacy, education and research.

Table of ContentsPrimary Immodeficiency Diseses 3

Introduction 4

Antibody Production Defects 5

Cellular or Combined Defects 11

Phagocytic Cell Immune Defects 15

Complement Defects 19

Practical Aspects of Genetic Counseling:General Considerations 22

Life Management Considerations 24

Health Insurance 25

Sample Physician Insurance Appeal Letter 27

Glossary 28

Immune Deficiency Foundation

Diagnostic & Clinical Care Guidelinesfor Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases

2 IMMUNE DEF IC I ENCY FOUNDAT ION

Mark Ballow, MDWomen and Children’s Hospital of Buffalo

Division of Allergy and Immunology

Melvin Berger, MD, PhDCase Western Reserve University

R. Michael Blaese, MDMedical Director

Immune Deficiency Foundation

Francisco A. Bonilla, MD, PhDChildren’s Hospital, Boston

Mary Ellen Conley, MDUniversity of Tennessee College of Medicine

St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital

Charlotte Cunningham-Rundles, MD, PhDMt. Sinai School of Medicine

Alexandra H. Filipovich, MDCincinnati Children’s Hospital

Thomas A. Fleisher, MDDepartment of Laboratory Medicine, CC

National Institutes of Health, DHHS

Ramsey Fuleihan, MDChildren’s Memorial Hospital, Chicago

Erwin W. Gelfand, MDNational Jewish Medical and Research Center

Steven M. Holland, MD

Laboratory of Clinical Infectious Diseases - NIAIDNational Institutes of Health

Richard Hong, MD

University of Vermont School of MedicineDepartment of Pediatrics

Richard B. Johnston, Jr., MDUniversity of Colorado School of Medicine

National Jewish Medical and Research Center

Roger Kobayashi, MD

Allergy, Asthma and Immunology AssociatesUCLA School of Medicine

Howard Lederman, MD, PhDJohns Hopkins Hospital

David Lewis, MDStanford University School of Medicine

Harry L. Malech, MD

Genetic Immunotherapy Section

Laboratory of Host Defenses - NIAIDNational Institutes of Health

Bruce Mazer, MD

McGill University Health CenterMontreal Children’s Hospital

Stephen Miles, MDAll Seasons Allergy, Asthma and Immunology

Hans D. Ochs, MD

Department of PediatricsUniversity of Washington School of Medicine

Jordan Orange, MD, PhDThe Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

Jennifer Puck, MD

Department of PediatricsUniversity of California San Francisco

William T. Shearer, MD, PhDTexas Children’s Hospital

E. Richard Stiehm, MD

Mattel Children’s Hospital at UCLAUCLA Medical Center

Kathleen Sullivan, MD, PhDThe Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

Jerry A. Winkelstein, MDJohns Hopkins University School of Medicine

EDITOR

Rebecca H. Buckley, MDDuke University School of Medicine

CONTRIBUTORS

D IAGNOST IC & CL IN ICAL CARE GU IDEL INES 3

P R I M A R Y I M M U N O D E F I C I E N C Y D I S E A S E S

ANTIBODY PRODUCTION DEFECTSDISEASE COMMON NAME ICD 9 CODE

X-Linked Agammaglobulinemia (Bruton’s) Agammaglobulinemia, XLA 279.04

Common Variable Immunodeficiency (CVID) Late Onset Hypo- or Agammaglobulinemia, CVID 279.06

X-Linked or Autosomal Hyper IgM Syndrome Hyper IgM 279.05

Selective IgA Deficiency IgA Deficiency 279.01

CELLULAR OR COMBINED DEFECTSDISEASE COMMON NAME ICD 9 CODE

Severe Combined Immunodeficiency “Bubble Boy” Disease, SCID 279.2

DiGeorge Syndrome also known as Thymic Aplasia 279.1122q11 Deletion Syndrome

Ataxia Telangiectasia AT 334.8

Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome WAS 279.12

PHAGOCYTIC CELL IMMUNE DEFECTSDISEASE COMMON NAME ICD 9 CODE

Leukocyte Adhesion Defect LAD 288.9

Chronic Granulomatous Disease CGD 288.1

Chediak Higashi Syndrome CHS 288.2

Cyclic NeutropeniaKostman Disease

Neutropenia 288.0

COMPLEMENT DEFECTSDISEASE COMMON NAME ICD 9 CODE

C1 Esterase Inhibitor Deficiency Hereditary Angioedema 277.6

Complement Component Deficiencies(e.g. C1, C2, C3, C4, C5, C6, C7, etc.) Complement Deficiency 279.8

4 IMMUNE DEF IC I ENCY FOUNDAT ION

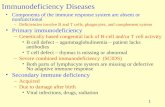

The hallmarks of primary immunodeficiency are recurrent orunusual infections. Some of the infections may be persistentand some may be due to unusual microorganisms that rarelycause problems in healthy people. The primaryimmunodeficiency diseases are a group of more than 150genetically determined conditions that have an identified or tobe determined molecular basis. Because most of these arelifelong conditions, it is very important to perform a detaileddiagnostic evaluation before initiating therapies that will becontinued in an open-ended fashion. The guidelines that follow

are intended to provide practical information for patients andhealth care providers who are concerned about whether or notan individual’s immune system is functioning normally.Currently, no screening is performed for these defects at birth,during childhood or in adulthood. Therefore, primaryimmunodeficiency diseases are usually detected only after theindividual has experienced recurrent infections that may ormay not have caused permanent organ damage. There isobviously a great need for the early detection of these defects.

I N T R O D U C T I O N

KEY CONCEPTSSITE OF INFECTIONS POSSIBLE CAUSE SCREENING DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

Upper Respiratory Tract Antibody or Complement Deficiency Serum immunoglobulin levels, antibodytiters to protein and polysaccharidevaccines; isohemagglutinins; CH50

Lower Respiratory Tract Antibody or Complement Deficiency; Serum immunoglobulin levels, antibodyT Cell Deficiency; titers to protein and polysaccharidePhagocytic Cell Defect vaccines; isohemagglutinins; CH50; WBC

with manual differential to countneutrophils, lymphocytes and platelets;Respiratory Burst Assay

Skin, internal organs Phagocytic Cell Defect Respiratory Burst Assay/CD11/CD18Assay

Blood or Central Nervous System Antibody or Complement Deficiency Serum immunoglobulin levels, antibody(meninges) titers to protein and polysaccharide

vaccines; CH50

Suspect a primary immunodeficiency if:

» There are recurrent infections or there is an unusual or persistent infection» A usually mild childhood disease takes a turn for the worse (may become life-threatening)» Blood cell counts are low or persistently high

Consider a PrimaryImmunodeficiency

Disease

Low Blood Cell CountsUnusual or LessVirulent Infectious

Agents

Persistent

RECURRENTINFECTIONS

D IAGNOST IC & CL IN ICAL CARE GU IDEL INES 5

Part A: Recognition and AssessmentAn infection recurring in a single site is generally not indicative of aprimary immunodeficiency disease. Rather it suggests an anatomicabnormality. On the other hand, several types of infectionsaffecting various organ systems may be indicative of an underlyingimmunologic deficiency.

These infections and conditions include:

� Recurrent sinopulmonary infections

» Pneumonia with fever» Sinusitis documented by X-ray or Computerized tomography

(C-T) scan» Otitis media (Although frequent ear infections are seen in

normal children, an evaluation may still be indicated forindividuals on a case by case basis.)

� Meningitis and/or sepsis (blood stream infection)

� Gastrointestinal infections

� Cutaneous (skin) infections

The occurrence of infections with unusual organisms also suggeststhe presence of a primary immunodeficiency disease. This is howsome patients are diagnosed. Examples are atypical mycobacteria,which would suggest an IFN-yR defect, or Pneumocystis jiroveci,which would suggest Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID)or Hyper IgM syndrome.

In addition, certain types of autoimmune and allergic conditionsmay be associated with some types of primary immunodeficiency,including antibody deficiency disorders. Examples of autoimmunedisorders includeautoimmune endocrine disorders, rheumaticconditions, and autoimmune hemolytic anemia, neutropenia orthrombocytopenia (low platelet count). These autoimmunedisorders are seen especially in patients with IgA deficiency,Common Variable Immunodeficiency (CVID), chronicmucocutaneous moniliasis (CMC or APCED), X-linked immunedysregulation, polyendocrinopathy and enteropathy (IPEX),autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS) and Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. Allergic disorders with elevated serum IgE canalso be seen in IgA deficiency, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, theHyper IgE syndrome, IPEX and Omenn syndrome.

Useful Physical Examination Findings� Absence or reduced size of tonsils and lymph nodes in X-linked

agammaglobulinemia and in X-linked Hyper IgM syndrome

� Enlarged lymph nodes and splenomegaly in CVID andautosomal recessive Hyper IgM syndrome

� Scarred tympanic membranes

� Unusual skin changes such as, complete absence of eyebrowsand hair, severe eczema resistant to treatment, mouth thrushresistant to treatment after 4 months of age, candida skininfections, petechiae, vitiligo, recurrent or persistent warts orsevere molluscum contagiosum

� Rales and rhonchi in lungs, clubbing of the fingers

Useful Diagnostic Screening Tests� Complete blood count and manual differential

» These tests are of great clinical importance because theyallow the physician to know whether the lymphocyte,neutrophil and platelet counts are normal. Many immunedefects can be ruled out by these simple tests. In the settingof immunodeficiency disorders, the manual differential is morereliable than an automated differential.

� Quantitative serum immunoglobulin (IgG, IgA, IgM and IgE)levels

» Quantitation of immunoglobulin levels can be performed atany CLIA (Clinical Laboratories Improvement Act) approvedlaboratory. However, the assay results should be evaluated inthe context of the tested patient’s age and clinical findings. Animportant problem exists for IgA levels, which may bereported as the value at the lower limit of sensitivity of themethod but may actually be zero. Most commercially availableassays for IgA are not sensitive enough to distinguishbetween very low and absent levels. Results of allimmunoglobulin measurements must be compared with age-adjusted normal values to evaluate their significance. IgGsubclass measurements are rarely helpful.

� Measurement of specific antibodies to vaccines

» These tests are of crucial importance in determining whetherthere is truly an antibody deficiency disorder when the serumimmunoglobulins are not very low or even if they are low. It isimportant to test for antibodies to both protein (i.e. tetanus ordiphtheria) and polysaccharide (i.e. pneumococcalpolysaccharides) antigens. Isohemagglutinins (antibodies tored blood cells) are natural anti-polysaccharide antibodies; ifthey are missing this also suggests an antibody deficiencydisorder.

When these screening tests are not conclusive and the clinicalsuspicion of an immunodeficiency is strong, the patient should bereferred to an immunologist for further evaluation before beginningimmune globulin (IG) replacement therapy. This is particularly true

A N T I B O D Y P R O D U C T I O N D E F E C T S

ANTIBODY PRODUCTION DEFECTSDISEASE COMMON NAME ICD 9 CODE

X-Linked Agammaglobulinemia (Bruton’s) Agammaglobulinemia, XLA 279.04

Common Variable Immunodeficiency (CVID) Late Onset Hypo- or Agammaglobulinemia, CVID 279.06

X-Linked or Autosomal Hyper IgM Syndrome Hyper IgM 279.05

Selective IgA Deficiency IgA Deficiency 279.01

6 IMMUNE DEF IC I ENCY FOUNDAT ION

for those who have been diagnosed with IgG subclass deficiencyor “polysaccharide antibody deficiency.” The latter diagnoses areoften based on the results of measurements of serum IgG subclasslevels or tests of pneumococcal antibody titers. The results of suchtests are highly variable from laboratory to laboratory andsometimes misinterpreted. If IG therapy is started before referral toan immunologist, it would seriously confound the ability of theimmunologist to perform further immunologic testing. Therefore, itis very important that all of the tests listed in this section be donebefore IG replacement is started.

Part B: Management, Expectations,Complications and Long TermMonitoringWith the exceptions of selective IgA deficiency and transienthypogammaglobulinemia of infancy, patients with an identifiedantibody deficiency disorder are generally treated on at regularintervals throughout life with replacement IG, either intravenously orsubcutaneously. IG therapeutic products are comprised ofnumerous IgG antibodies purified from blood or plasma donationsfrom approximately 60,000 donors per batch. The half-life of theseIgG antibodies is 19-21 days and the amounts of the other classesof immunoglobulins are extremely low, so they do not affect thepatient’s blood level of these proteins. The intervals between IGdoses are generally 2 to 4 weeks for the intravenous route ofadministration and more frequently (1 to 14 days) for thesubcutaneous route. An immunologist should participate in thedetermination of the proper dose and interval for IG therapy ineach patient. Typical total monthly doses are in the range of 400 to600 mg/kg body weight. Trough (pre-dose) blood levels of IgG canbe evaluated more frequently initially and at least once a year afterthat to determine if there has been a change in thepharmacokinetics and resultant blood levels of IgG in a specificindividual. IG dose adjustments are obviously necessary duringchildhood related to normal growth or during pregnancy. However,once an IG dose has been established for an adult, it is not usuallynecessary to routinely measure trough IgG levels unless the patientis not doing well clinically. The trough level should be at least at orabove the lower range of normal for IgG levels or >500 mg/dl. Thismay vary depending on the judgment of an immunologist as to thepatient’s clinical condition. For example, in one study, when IgGtrough levels in patients with agammaglobulinemia weremaintained above 800 mg/dl, serious bacterial illness andenteroviral meningoencephalitis were prevented. Higher troughlevels (>800 mg/dl) may also have the potential to improvepulmonary outcomes. It is important to recognize that, for virtuallyall confirmed antibody deficiencies, lifelong IG replacement isrequired.

IG replacement is preventive therapy, and the regular dose shouldnot be considered adequate to treat infections. Many patients withantibody production disorders also benefit from the use ofprophylactic antibiotics or adjunctive therapy with full doseantibiotics rotating on a monthly schedule. This is because IG

therapy only replaces IgG and there is no way to replace IgA in thepatient’s serum or external secretions. Patients with antibodydeficiencies are at risk for developing chronic sinus and lungdisease; therefore, it is best to obtain an annual assessment ofpulmonary function and sinus or chest x-rays or perhaps highresolution C-T scans. Families should expect that their affectedrelative will have decreased absences from school and/or workwith proper therapy. However, while sepsis and meningitis attackswill stop with IG treatment, sinopulmonary and gastrointestinalinfections may continue to occur, although with less frequency.

If there is evidence of bronchiectasis in an individual with anantibody deficiency disorder, a high-resolution C-T scan of thelungs should be obtained and repeated as needed or if therapy isaltered to monitor progression. Excessive scanning should beavoided.

Spirometry (lung breathing tests) should also be performedannually or at 6-month intervals if the disease appears to beprogressing adversely at a more rapid rate. Complete pulmonaryfunction testing should also be done periodically in CVID patientswho have interstitial lung disease in order to measure their diffusioncapacities. Liver and renal function blood tests should be checkedprior to beginning IG therapy and at least once a year thereafter.

In the face of any abnormal neurologic or developmental findings,a baseline lumbar puncture (spinal tap) for the examination ofspinal fluid may be helpful in detecting an insidiousmeningoencephalitis (brain) infection due to enterovirus,particularly in patients with X linked (Bruton’s)agammaglobulinemia. Developmental assessments of suchchildren should also be obtained annually or at 6-month intervals ifthe disease appears to be progressing adversely at a more rapidrate.

From a prognostic point of view, antibody deficient patientsdetermined to have B cells by flow cytometry (e.g. likely to haveCVID) are also at risk for autoimmune disease complications.

Granulomatous lesions in the skin, liver, spleen and lungs inpatients with CVID may be misdiagnosed as sarcoid and theiroccurrence also diminishes the prognosis.

Patients with CVID, Bruton’s agammaglobulinemia or X-linkedHyper IgM may present with chronic diarrhea and havemalabsorption due to infection with parasites, e.g. Giardia lambliaor Cryptosporidium, or from overgrowth in the small intestines withcertain types of gram negative bacteria, e.g. C. difficile.

IG Therapy When Diagnosis is UncertainWhen there is uncertainty of the diagnosis, and IG replacement hasalready been started, it is useful to reassess the need for IGtreatment. This is particularly true if the patient’s serum containsIgA, IgM and IgE, which are not present in significant amounts inIG preparations. If these classes of immunoglobulin are present inthe patient’s serum, this means that the patient is producing them.However, the serum IgG level and antibody titers to vaccineantigens could all be from the IG therapy. To further evaluatewhether the patient can produce IgG antibodies normally, thepatient can be challenged with a neoantigen (e.g. a vaccine notroutinely administered, such bacteriophage phi X174) for which

A N T I B O D Y P R O D U C T I O N D E F E C T S

D IAGNOST IC & CL IN ICAL CARE GU IDEL INES 7

A N T I B O D Y P R O D U C T I O N D E F E C T S

there is no specific antibody in IG preparations. Whilebacteriophage immunizations are useful because it is notnecessary to discontinue IG replacement when they are given, thevaccine and testing are available at only a few research institutionsunder an IND application. Alternately, only under the advisement ofan immunologist, IG treatment can be stopped in the spring orsummer when infection risks are less. After three months the patientcan be reimmunized with standard killed vaccines and the antibodytiters to these vaccines tested two to three weeks later. If thepatient’s serum immunoglobulins and antibody titers tobacteriophage phiX174 and/or to vaccine antigens are found to bein the normal range, then IG replacement is not necessary. Skintesting for allergies is also useful; individuals who have positiveallergy skin tests are producing IgE antibodies to the allergens andare not likely to need IG replacement.

Monitoring IG Therapy in Antibody Deficient PatientsFrequency of testing for trough levels

� Monitor IgG levels at least once a year (more often if the patientis having infections) just before the next infusion. Be aware thatgastrointestinal tract infection with the parasite Giardia lamblia orother enteropathies can cause enteric loss of IgG leading tounexpectedly low IgG levels. Generally, once the optimal dose ofimmune globulin has been established in a patient, monthlymonitoring of the IgG level is not indicated unless there is proteinloss through the GI or urinary tracts.

Long-term follow up of patients on IG therapy

� Evaluations regarding hepatitis A, B, and C by PCR (polymerasechain reaction) screening may be indicated. Yearly PCRscreening for hepatitis C is the standard of care in EuropeanUnion countries.

Adverse event monitoring on IG therapy

� Every 6-12 months creatinine level and liver function tests areuseful.

Other ScreeningsCancer screening may be indicated on a periodic basis, as it is forindividuals with intact immune systems. Some subgroups of thosewith a primary immunodeficiency disease, such as patients withCVID, particularly those with chronic lymphadenopathy may meritbaseline complete pulmonary function studies, CT, MRI and/or PETscans and more intensive screening. Lymphoma evaluation is thesame as for those without hypogammaglobulinemia. Usefuldiagnostic screening tests for malignancy include determination ofuric acid, LDH (lactic dehydrogenase) and ESR (erythrocytesedimentation rate).

VaccinationsPatients receiving regular infusions of IG possess passiveantibodies to the agents normally given in vaccines. Thus, while apatient is receiving IG, there is no need for immunizations. Someimmunologists recommend influenza vaccination, but the patient isunlikely to respond to it with antibody production. However, allhousehold contacts should receive regular immunizations with killedvaccines, particularly annual influenza immunizations. Live virus

vaccines, even if attenuated, pose a substantial risk to certainindividuals with primary immunodeficiency diseases. Thesevaccines include the the new rotovirus vaccines (Rototeq® orRotorix®), oral polio vaccine, mumps, measles and Germanmeasles (rubella) vaccine (MMR®), yellow fever vaccine, and thechickenpox vaccine (Varivax®). In addition, FluMist®, an intranasal,attenuated live influenza vaccine could potentially be a risk forthose with primary immunodeficiency, although adverse events fromthis have not yet been reported. Agents used to counteractbioterrorism such as vaccinia vaccine to provide immunity tosmallpox may also be harmful to a person with associated T celldefects.

Part C: Practical Aspects of GeneticCounselingThe genetic bases of many of the common antibody productiondefects are currently unknown. This is especially true for mostpatients with Common Variable Immunodeficiency and SelectiveIgA deficiency where the underlying molecular defect has beenidentified in less than 10% of patients. For this reason, geneticcounseling can be complicated in families affected by thesedisorders. The inheritance pattern and recurrence risk to familymembers is difficult to predict without a molecular diagnosis,but an accurate family history may be helpful in this aspect. Itshould be noted, however, that these disorders can also occursporadically and the family history in those cases would benegative. Even though the inheritance pattern for somedisorders may not be clearly understood, research has shownthat family members of patients with CVID and Selective IgAdeficiency also have an increased risk of antibody deficienciesand autoimmune disorders. It is also important to note that,when the gene defect has not been identified for a specificdisorder, prenatal diagnosis is not an option.

The genetic bases of other antibody production defects areknown and these disorders include patients with absent B cellsand agammaglobulinemia and most cases of the Hyper IgMsyndrome. These disorders can follow either an X-linkedrecessive or an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern. Pleasesee the general genetic counseling section for a more detailedexplanation of inheritance. Because mutations in a variety ofdifferent genes can cause these conditions, molecular testing isimportant to determine the specific gene involved and itsmutation. This can help predict the clinical manifestation of thedisorder in the affected individual. The gene identification alongwith an accurate family history will also help determine thepattern of inheritance in the family, risks for family members thatcould be affected, as well as identification of at-risk carrierfemales of X-linked disorders. Genetic testing is currentlyavailable in specialized labs for diagnostic confirmation, carriertesting and prenatal diagnosis of some of these diseases. For acurrent list of these laboratories, consult your immunologist orcontact the Immune Deficiency Foundation.

8 IMMUNE DEF IC I ENCY FOUNDAT ION

1. Will the patient outgrow the disease?While it is unlikely that a patient will outgrow a primaryimmunodeficiency disease, identifying changes in thepatient’s medical condition and their management is bestperformed by your immunologist.

2. What is IG?IG stands for immune globulin, a family of plasma proteinsthat help fight infections. Commercially availablepreparations of these globulins are comprised ofnumerous IgG antibodies purified from blood or plasmadonations from approximately 60,000 donors per batch.The name IVIG refers to the intravenous (in the vein) formof IG and SCIG is IG, which is given subcutaneouslyunder the skin.

3. Is there a need for extra IG during infections, such aspneumonia, and during surgery?During an infection, the antibodies to that infectious agentare rapidly used up, so there may be a need for additionalamounts of IG during that illness. IG may also providebroad protection against infections that may occur duringinvasive surgery. Appropriate antibiotic coverage shouldalso be considered during surgery.

4. Can IG be given orally and is there any place for thisas a treatment?While IG has been given by mouth to some patients,trying to mimic the situation in very young animals wherethe infant animal receives protective antibodies in mother’smilk, there are no research trials that confirm itsusefulness in people.

5. Is there protection in IG from West Nile Virus?At the present time, this is unknown. However, there is norisk of transmitting the virus by IG.

6. What is the safety of IG?There is a remote or theoretical possibility of blood bornedisease transmission. However, laboratory screeningmethods are very good and can identify infected donorsas well as those developing infection. In addition, themanufacturing of IG separates and may inactivatepotentially contaminating viruses. To date, there has beenno evidence of prion (the agent of Mad Cow Disease) orHIV transmission by IG.

7. Why is it important to record the brand, infusion rateand lot numbers of IG that is infused?On rare occasions, a problem is identified in a specific lotof IG from a specific manufacturer. With good recordkeeping, you can know if the potential problem affects youor you can avoid infusing the specific lot. The best way tolearn about these types of problems when they happen isto sign up for the Patient Notification System, by calling1-888-UPDATE-U (1-888-873-2838).

8. Is it appropriate to have a central vascular line(Infusaport, Broviac or Hickman) implanted to receiveIVIG treatments?While surgically implanted central lines may makeinfusions easier, they carry real risks of serious infectionand blood clotting that could greatly complicate the careof a person with a primary immunodeficiency disease.Therefore, central lines are not recommended if only to beused for this purpose. When “standard” venipunctures aremade to start IV lines for the infusion of IVIG, it is helpfulin younger patients to apply a topical anesthetic creamlike EMLA 30 to 60 minutes before the “stick.”

9. Can IG be given in any way besides by vein?There have been a number of studies that demonstratethat IG can be infused subcutaneously (SC), under theskin in restricted volumes, with good clinical results. Useof SCIG may be a good choice for those with poorvascular access, very young children and those withnumerous reactions to the intravenous infusions.Immunology specialists will be familiar with this techniqueand can advise you whether it is appropriate for you. OneIG preparation for subcutaneous administration has beenlicensed in the United States and it is anticipated thatthere will be others in the near future.

10. What are some types of reactions to IG?Reactions are common during the first infusions of IVIGafter the diagnosis has been established. They are ofseveral different types. True allergic reactions are rare,occur early during the time of the infusion and arecharacterized by hives, chest tightening, difficulty inswallowing or breathing, feeling faint, abdominaldiscomfort and blood pressure or pulse changes. The firstresponse should be to stop the infusion. Your medicalprovider may then take additional steps if the symptomsdo not rapidly subside.

Lot-to-lot and product-to-product reactions may includeheadache, flushing, lightheadedness, nausea, vomiting,back or hip pain and fatigue. These side effects are morecommon and are usually rate related, occurring generallyat the higher infusion rates.

Headaches may be a significant complication and mostoften occur within 24 hours of an IVIG infusion. Someheadaches can be managed with milder analgesic agentslike acetaminophen (Tylenol®), aspirin or ibuprofen.However, some headaches represent the syndrome ofaseptic meningitis. Severe headaches occur mostfrequently in individuals with a prior history of migraineheadaches.

For specific information about less common but seriousreactions, you should refer to the specific IVIG packageinsert.

A N T I B O D Y P R O D U C T I O N D E F E C T S

Part D: Frequently Asked Question about Antibody Deficiency Disorders

D IAGNOST IC & CL IN ICAL CARE GU IDEL INES 9

A N T I B O D Y P R O D U C T I O N D E F E C T S

Patients experiencing reactions should NOT be treated athome. Newly diagnosed patients or patients using a newproduct should receive their first infusion in a medicalsetting.

11. How is IG reimbursed?Ask your provider for an itemized bill to help clarify billingquestions, or ask your insurance company for anExplanation of Benefits (EOB). Reimbursement for IG mayvary from year to year and from insurance plan toinsurance plan. It is very important to understand yourplan and its coverages.

12. As more patients receive their IG infusions in thehome, what is the recommendation for follow up withan immunology specialist?An immunologist should follow up most patients every 6 to12 months, but patients with secondary complications,such as chronic lung or gastrointestinal disease may needmore frequent follow-up and/or more than one specialist.

13. What expectations should the patient with antibodydeficiencies have once he or she is on immuneglobulin therapy?IG therapy should protect the patient from sepsis (bloodstream infection), meningitis (infection of the coverings ofthe brain) and other serious bacterial infections. Inaddition, school/work absences will decline. However, donot expect all infections to stop. There may still be a needfor the use of antibiotics. Children in general fare betterthan adults do. Quality of life should be greatly improvedon immune globulin therapy.

14. What is the role of antibiotics in antibody deficiencydiseases?Antibiotics may be used chronically if there is evidence ofchronic infection or permanent damage to the lungs(bronchiectasis) or sinuses. The antibiotics should begiven in full treatment doses. Often, different antibioticswill be prescribed on a rotating schedule on a monthlybasis. Prophylactic antibiotic therapy may be useful forsome patients with Selective IgA deficiency, as IG therapyis not indicated for that condition.

15. What is the role of over-the-counter immunestimulants?There is no evidence that these stimulants have anyhelpful effects.

16. Is it OK to exercise and play sports?Yes. Physical activity and sports may help improvepatients’ sense of well-being and enable them toparticipate in some of life’s enjoyable activities.

17. Is it OK to have pets?Yes, but be aware that animals may carry infections suchas streptococcal infections that can be transmitted tohumans. In addition, live vaccines may be given todomestic pets and could potentially pose a risk to theperson with primary immunodeficiency.

18. Can IG be given during pregnancy?Yes and it should be given as when not pregnant.

For additional information on the use of IVIG, see:Orange JS, Hossny EM, Weiler CR, Ballow M, Berger M,Bonilla FA, Buckley RH et al. Use of intravenousimmunoglobulin in human disease: a review of evidence bymembers of the Primary Immunodeficiency Committee of theAmerican Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. JAllergy Clin Immunol 117: S525-S553, 2006.

Part D: Frequently Asked Question about Antibody Deficiency Disorders

10 IMMUNE DEF IC I ENCY FOUNDAT ION

TreatmentImmune Globulin Replacement

IgA < 11mg/dL

IgM > 200or < 40mg/dL

IgG < 400mg/dL

LABORATORYEVALUATION

May be a primaryimmunodeficiency

TYPES OF INFECTIONSRecurrent Otitis and Sino-Pulmonary Infections with Fever

MeningitisSepsis

Cutaneous InfectionsGI Infections

Autoimmune Disorders: Immune Cytopenias

One site of infection > Two sites of infection

May be a primaryimmunodeficiency

Generally NOT a primaryimmunodeficiency

Findings on PhysicalExamination

Absent tonsils or Lymph nodes

Generally a primaryimmunodeficiency

Low age-adjusted absoluteLymphocyte, Neutrophil or

Platelet Counts

Tonsils and Lymph nodes present

IgE > 1000IU/ml

CBC and DifferentialQuantitative Immunoglobulins

ANTIBODY PRODUCTION DEFECTS

Specialized Testing

Referral to an immunologist for further evaluation, diagnosis and development of a care plan

D IAGNOST IC & CL IN ICAL CARE GU IDEL INES 11

C E L L U L A R O R C O M B I N E D D E F E C T S

CELLULAR OR COMBINED DEFECTSDISEASE COMMON NAME ICD 9 CODE

Severe Combined Immunodeficiency “Bubble Boy” Disease, SCID 279.2

DiGeorge Syndrome also known as Thymic Aplasia 279.1122q11 Deletion Syndrome

Ataxia Telangiectasia AT 334.8

Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome WAS 279.12

Part A: Recognition and AssessmentThese individuals have abnormal T cell function and, as aconsequence, also have problems with antibody production.Affected individuals have both common and unusual infections.Typically, the patient is an infant or a young child and would notsurvive without early medical diagnosis and intervention(s). Someaffected individuals present clinically in the nursery, such as thosewith severe or complete DiGeorge syndrome or some with theWiskott-Aldrich syndrome. However, most other infants with severeT cell defects have no outward signs to alert anyone to theirproblem until infections begin. Those with the most severe formsof cellular or combined defects represent a true pediatricemergency and should receive prompt referral to an immunologistso that plans can be made for treatment — often a transplant toachieve immune reconstitution. Early diagnosis can avoidinfections and make survival more likely. Patients may:

� Appear ill

� Have facial dysmorphia (DiGeorge syndrome) or ectodermaldysplasia (NEMO)

� Fail to thrive

» Weight is a more important determinant than length

� Have congenital heart disease (heart murmur at birth, cyanosis,DiGeorge syndrome)

� Have skin changes

» Severe diaper rash or oral candidiasis (thrush)

» Eczema as in Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome or Graft versus HostDisease (GVHD)

» Red rash as in GVHD, Omenn’s syndrome or atypicalcomplete DiGeorge syndrome

» Telangiectasia (prominent blood vessels)

» Petechiae in Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome

» Absence of nails, hair or sweating (NEMO)

� Have chronic intractable diarrhea

� Develop intractable viral infections due to Respiratory syncitialvirus (RSV), parainfluenza, cytomegalovirus (CMV), EpsteinBarr Virus (EBV), or adenovirus

� Have infections not accompanied by lymphadenopathy exceptin the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome

� Have adverse reactions after live vaccines such as Varivax,given to prevent chicken pox

� Have neurological findings such as ataxia or tetany of thenewborn (DiGeorge syndrome)

� Have X-linked immune dysregulation and polyendocrinopathy(IPEX), or chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMC,APCED)

� Need to have a diagnosis of Human Immunodeficiency Virus(HIV) infection excluded

Some combined defects, though ultimately fatal without treatment,are not initially as severe so do not present as early as SCID.Examples are zeta-associated protein (ZAP) 70 deficiency, purinenucleoside phosphorylase (PNP) syndrome, Wiskott-Aldrichsyndrome or nuclear factor of kappa B essential modulator(NEMO) deficiency. The clinical recognition of AtaxiaTelangiectasia may also be delayed, as signs developprogressively during the first several years of life.

Laboratory TestingA white blood cell count with a manual differential should beobtained to determine whether the patient has a low absolutelymphocyte count (i.e. is lymphopenic). Age-appropriate normalvalues must be considered.

These tests would also reveal whether the patient has too low aneutrophil count (i.e. is neutropenic) or has an elevated neutrophilcount, as is seen in leukocyte adhesion deficiency (LAD). Plateletcounts and platelet size measurements may also be useful to ruleout Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. Referral to an immunologist shouldbe made for more detailed lymphocyte analysis by flow cytometry.T cell functional testing is of greatest importance. Quantitativeimmunoglobulin measurement and antibody testing should beperformed. Genetic testing is complicated by the fact that thereare at least twelve different molecular causes of SCID. If adiagnosis of SCID is suspected, the infant should be kept awayfrom other small children and those with infections andimmediately referred to an immunologist for definitive treatment asthis is a pediatric emergency.

DEFINITION OF LYMPHOPENIABirth < 2500/µL5–6 Months up to 1 year < 4000/µLAdult < 1000/µL

12 IMMUNE DEF IC I ENCY FOUNDAT ION

Part B: Management, Expectations,Complications and Long TermMonitoringOnly irradiated (5000 RADS), CMV-negative, leukocyte-depleted blood products should be used in managing thepatient with SCID or other suspected T cell deficiencies. Nolive virus vaccines should be administered to any member ofthe household, including the patient. This includes no rotovirus(Rotateq® or Rotarix®), oral polio, MMR®, FluMIST® orVarivax® vaccines and no BCG in countries where thesepractices are recommended. However, all household contactsshould receive regular immunizations with killed vaccines,particularly annual influenza immunizations. Typical serious,often overwhelming or fatal infections in SCID are PJP(Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia), candida, RSV,parainfluenza 3, CMV, EBV and adenovirus. If an infant issuspected of having SCID, he or she should be placed on PJPprophylaxis with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. If there is afamily history of an early death due to infection, a diagnosis orexclusion of SCID in a subsequent birth can be done byperforming a white blood cell count and a manual differentialon the cord blood to look for a low lymphocyte count. If thecount is low, flow cytometry, a specialized laboratory test,should be performed to see if T cells are present.

Immune reconstitution in SCID generally requires bone marrowtransplantation early in life. No pre-transplant chemotherapynor post-transplant GVHD prophylaxis is needed for true SCIDinfants because they do not have T cells. Gene therapy has

been tried with notable success, but there have been seriousadverse events. SCID patients who have received successfulbone marrow transplants require at least annual follow up byan immunologist at a specialized center. There may beunanticipated complications and patients should also have theopportunity to benefit from new therapeutic developments.

Patients with combined immune deficiencies (CID) who havelow but not absent T cell function may additionally fail to makeantibodies normally despite normal or elevated immuneglobulin levels. They also require IG replacement therapy. Forexample, although Wiskott-Aldrich patients may have normalserum immunoglobulin levels, they are usually treated with IGbecause their ability to make antibodies is abnormal. In thecomplete form of DiGeorge syndrome, there is no T cellfunction and thymic transplantation is the recommendedtreatment. The long-term outcome for partial DiGeorgesyndrome is generally satisfactory from an immunologicperspective, however, susceptibility to other complicationssuch as developmental delay, seizure, severe autoimmunedisease or EBV induced lymphoma remains. AT (AtaxiaTelangiectasia) patients and patients with SCID due to Artemisgene mutations should minimize their exposure to ionizingirradiation, as they have an increased risk for chromosomalbreakage and its complications.

C E L L U L A R O R C O M B I N E D D E F E C T S

Part C: Practical Aspects of GeneticCounselingThe genetic basis is known for many of the cellular orcombined immune defects. Several of these disorders followX-linked inheritance; many others follow autosomal recessiveinheritance. Please refer to the general genetic counselingsection for an explanation of inheritance patterns. A specialconsideration for genetic counseling of families affected bythese disorders is the fact that there are several differentgenes that, when mutated, result in the same clinical disorder.For example, it is currently known that mutations in one of atleast eleven genes can cause SCID. The most common formof SCID follows X-linked inheritance; all other forms of SCIDfollow autosomal recessive inheritance. It is therefore crucialthat genetic testing be done to determine the specific geneinvolved in these disorders to provide accurate estimates ofrisks for family members being affected. However, genetictesting should not delay initiation of appropriate treatment.Genetic testing for many of the cellular or combined

immunodeficiency disorders is only available in specializedlaboratories in the U.S. and abroad. For more specificinformation refer to the general section on genetic counseling.

DiGeorge syndrome is one of the few primaryimmunodeficiency diseases that may follow autosomaldominant inheritance, however most cases are sporadic. It iscaused by a deleted portion of a region on chromosome 22 inmore than half of the cases, by mutations in a gene onchromosome 10 in another 10% and is of unknown cause inthe other cases; it affects both males and females. While manyof these cases occur as new mutations in the genesresponsible on chromosome 22, it is also important to domolecular testing of the parents of a child with this conditionbecause there can be clinical variability and an affectedparent may have previously gone undiagnosed. Whether or notthe chromosome defect is inherited or due to a new mutationhas significant impact on recurrence risk for a family. Genetictesting for chromosome 22 deletions is widely available inlaboratories across the United States.

D IAGNOST IC & CL IN ICAL CARE GU IDEL INES 13

1. What happens if my child is exposed tochickenpox?You need to let your physician know immediately so heor she can receive VariZIG (Varicella IG), aninvestigational hyperimmune globulin, within 48 hoursof exposure. IG replacement therapy in the usualdoses can also provide antibodies against thechickenpox virus. The incubation period of varicella is11 to 21 days. If your child already has a vesicularrash, which looks like small blisters, he or she will needto be treated with acyclovir, an antiviral agent.Intravenous (IV) acyclovir is superior to oral.

2. What is the risk to those with primaryimmunodeficiency diseases if attacks ofbioterrorism occur?Individuals with T cell defects are at serious risk ifwidespread smallpox immunization programs areinitiated. Anti-vaccinia antibodies in immune globulintherapy may offer some protection. Research is beingconducted to find additional treatments, and vacciniahyper-immune globulin is being developed.

3. What kind of vaccines can my child receive?All of the killed vaccines are safe, but he or she shouldnot receive any live vaccines such as rotovirus(Rotateq® or Rotarix®), oral polio, measles, mumps,rubella (MMR®), varicella (Varivax®), or intra nasalinfluenza vaccine (FLuMist®). Antibodies in IG may giveprotection against some or all of these viruses. Ingeneral, immunodeficient patients who are receiving IGreplacement should not be given vaccines, althoughsome immunologists give influenza immunizations. Ifthe patient is immune deficient enough to need IGreplacement, he or she probably would not be able torespond with antibody production. It is uncertainwhether there would be a T cell response that could behelpful. However, the antibodies in the IG replacementtherapy would neutralize most vaccines and they wouldbe ineffective.

C E L L U L A R O R C O M B I N E D D E F E C T S

Part D: Frequently Asked Questions

14 IMMUNE DEF IC I ENCY FOUNDAT ION

LaboratoryTesting

Refer toImmunologist

TreatmentImmune Globulin

Replacement TherapyBone Marrow Transplantation

Gene Therapy

Complete blood countand manual differential

LymphopeniaBirth < 2500/µL,

5 – 6 Months < 4000/µL,Adults < 1000/µL,

Thrombocytopenia orNeutropenia

Failure to thriveand gain weight

Adverse reactionsafter live vaccines

Intractable diarrhea,viral infections

Cutaneousfindings

Absence oflymphoid tissue

PhysicalExamination

Common or unusualinfections in an infant or

young child

CELLULAR ORCOMBINEDDEFECTS

D IAGNOST IC & CL IN ICAL CARE GU IDEL INES 15

Part A: Recognition andAssessmentSigns of defects in the phagocytic cells are manifest inmany organ systems. The onset of symptoms is usually ininfancy or early childhood.

— Skin—abscesses (boils) (seen in CGD and the HyperIgE syndrome) and/or cellulitis (inflammation of theskin) (seen in LAD)

— Lymph nodes—may be swollen and contain pus inCGD patients

— In LAD there may be delayed shedding of the umbilicalcord or infection of the cord base (omphalitis) andcellulitis but no abscesses.

— Osteomyelitis—an infection of bone seen frequently inpatients with chronic granulomatous disease (CGD).

— Hepatic Abscess—liver absesses may also be seen inCGD

— Lungs—Aspergillus (mold) lung disease is insidiousand common in patients with CGD. Abscesses andother infections may occur in these patients due topathogens that do not result in abscesses in normalhosts.

— Gastrointestinal tract outlet and/or urinary tractobstruction resulting in abdominal or back pain is oftenseen in CGD, as is constipation

— Mouth (gingivitis)—gum inflammation, mouth ulcers

— Unexplained fever without identifiable cause

— Malaise and fatigue

— Albinism may be seen in Chediak Higashi syndrome

Laboratory TestsDefects in phagocytic cells can be due to an insufficientnumber of such cells, an inability of the cells to get to aninfected area, or to an inability to kill ingested bacteria orfungi normally.

— A complete blood count and differential are needed todetermine whether phagocytic cells (neutrophils) arepresent in normal number. In the case of cyclicneutropenia, the test (absolute neutrophil count orANC) has to be repeated sequentially (e.g. 2 times perweek for 1 month).

— A test for CD11/CD18 expression on white cells isneeded to exclude LAD.

— A Respiratory Burst Assay (the replacement for theNBT assay) should be performed to determine ifphagocytic cells can produce oxygen radicals neededto kill bacteria and fungi. Neutrophils from patients withCGD do not produce these oxygen radicals.

« As is the case in CGD, patients with the Hyper IgEsyndrome also present with abscesses (boils)although they have a normal number of neutrophilsand a normal Respiratory Burst Assay result. Thus, aserum IgE level should be measured in patients withrecurrent abscesses to make certain that the HyperIgE syndrome is not the underlying cause.

P H A G O C Y T I C C E L L I M M U N E D E F E C T S

PHAGOCYTIC CELL IMMUNE DEFECTSDISEASE COMMON NAME ICD 9 CODE

Leukocyte Adhesion Defect LAD 288.9

Chronic Granulomatous Disease CGD 288.1

Chediak Higashi Syndrome CHS 288.2

Cyclic NeutropeniaKostman Disease

Neutropenia 288.0

16 IMMUNE DEF IC I ENCY FOUNDAT ION

P H A G O C Y T I C C E L L I M M U N E D E F E C T S

Part B: Management, Expectations,Complications and Long TermMonitoringIn general, neutropenia (reduced numbers of phagocytes)is most commonly secondary to a drug or an infection andthe patient should be referred to a hematologist or otherspecialist for management. In individuals with a primaryimmunodeficiency disease affecting phagocytic cells,prophylactic antibiotics are appropriate. These antibioticsinclude trimethoprim sulfamethoxizole and cephalexin.CD40 Ligand deficient patients are often profoundlyneutropenic. Individuals with Kostmann’s Syndrome may beresponsive to granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF), as may be the neutropenia associated with CD40Ligand deficiency. Prophylactic antifungal agents are oftenadministered in patients with CGD.

It is important to obtain bacterial and fungal cultures inthese patients to direct antibiotic treatment. Withappropriate antibiotic therapy, individuals with CGD shouldlive into their 40’s or older. However, there are differences ininfection susceptibility in terms of the X-linked and

autosomal recessive types, with somewhat more frequentinfections in the X-linked type. Meticulous medical carefrom an expert in immunology will increase the patient’schances of longer survival. Typically, hemogloblin,hematocrit, ESR (erythrocyte sedimentation rate) and/orCRP (C-reactive protein) and a chest X-ray should befollowed regularly in CGD. If there is any fever, malaise orchange in health status, the patient requires immediatemedical evaluation. Patients with CGD have normal T celland B cell function. Therefore, they are not susceptible toviral infections, can receive live virus (but not BCG)vaccines, and can attend school and visit public areassuch as malls.

Gamma-interferon has been used to treat CGD. There is nochange in in vitro tests of phagocytic cell function with thistreatment, although some clinical benefit (e.g. reducednumber of serious infections) has been reported. Bonemarrow transplantation has been successful in children withCGD when there is a matched sibling donor.

Part C: Practical Aspects of GeneticCounselingThe genetic basis is known for most of the phagocytic cellimmune defects. However, as with SCID, mutations inmultiple genes are responsible for a clinically similarcondition. For example, four genes (when mutated) areknown to cause Chronic Granulomatous Disease. The mostcommon form of this disorder follows X-linked recessiveinheritance and the other forms follow autosomal recessiveinheritance. A detailed family history may be helpful in

determining the type of CGD. However, genetic testing isagain crucial in determining the specific gene involved.With this information, the clinical prognosis can beassessed and patterns of inheritance determined in thefamily. Genetic testing for the phagocytic cell immunedefects is only available in specialized laboratories. Pleasesee the general section on genetic counseling for moreinformation about testing.

D IAGNOST IC & CL IN ICAL CARE GU IDEL INES 17

Part D: Frequently Asked Questions1. What activities and places should my child avoid?

There is no general recommendation for avoiding infections. However, swimming in lakes or ponds should beavoided. Exposure to aspergillus and mold that is associated with gardening that involves digging and handling orbeing around mulch should also be avoided. These and any other activities that will expose the child with aphagocytic cell primary immunodeficiency to potentially harmful bacteria or fungi should be avoided.

2. Can my child receive all types of vaccines?Yes, except for Bacille Calmette Guerin (BCG), because patients with CGD have normal T and B cell function.

P H A G O C Y T I C C E L L I M M U N E D E F E C T S

18 IMMUNE DEF IC I ENCY FOUNDAT ION

Skin GastrointestinalTract

RespiratoryBurst Assay

CD11/CD/18 byflow cytometry

Serum IgE Levels

Lymphadenopathy Musculoskeletal Pulmonary ConstitutionalSymptoms

Antibiotics Anti Fungal Agents

Bone MarrowTransplantation

Gamma-Interferon

CBC and ManualdifferentialESR or CRP

If abnormal, refer to an immunologist for further evaluation, diagnosis and treatment

PHAGOCYTIC CELLIMMUNE DEFECTS

Physical Examination

Laboratory Tests

Treatment

D IAGNOST IC & CL IN ICAL CARE GU IDEL INES 19

Evaluation of the complement system is appropriate forpatients with episodes of bacteremia, meningitis orsystemic Neisserial (either N. meningitidis or N. gonorrhea)infections. A single systemic Neisserial infection warrantsimmediate testing of the complement system.

� C1, C4 or C2 deficiencies may present with recurrentpneumococcal disease, i.e. otitis, pneumonia orbacteremia. There can also be concomitant antibodydeficiency due to poor antigen uptake by dendritic cells,which normally interact with antigen-antibody complexesbearing complement components. System lupuserythematosus is much more common than infections asa manifestation of early complement componentdeficiencies.

� C3 deficiency is very rare, but is characterized byrecurrent serious bacterial infections, such as pneumoniaor bacteremia, and development ofmembranoproliferative glomerulonephritis.

� Systemic Neisserial infections in children andadolescents suggest C5-7 deficiencies:

» Recurrent Central Nervous System (CNS) infectionsare more common in African Americans thanCaucasians with complement component deficiencies.

» Genitourinary tract infections are also seen.

» Cutaneous lupus and other manifestations ofautoimmunity are observed, particularly withdeficiencies of C1, C2, or C4.

Hereditary Angioedema is due to a deficiency of C1esterase inhibitor. Patients may experience recurrentepisodes of abdominal pain, vomiting and laryngealedema. The diagnosis can be made based on the clinicaloccurrence of angioedema (swelling) and the repeatedfinding of decreased quantities of C1 inhibitor protein oractivity and reduced levels of C4. C1q when measuredconcomitantly is normal.

Laboratory TestsDiagnosis: CH50 and AH50

� In the work up for complement deficiency, the CH50 isan excellent screening test, but the blood needs to behandled carefully—see below. Alternative Pathwaydefects can be screened for with the AH50 test.Identification of the particular component that is missingwill require studies in a research or specializedlaboratory.

� For diagnosis, proper specimen collection of bloodsamples is very important. Complement is very heatlabile. In general, if the CH50 is undetectable, thepatient likely has a deficiency in a complementcomponent, however, if the CH50 is just low, it is morelikely that the specimen was not handled properly or thatthe patient has an autoimmune disease.

C O M P L E M E N T D E F E C T S

Part A: Recognition and Assessment

COMPLEMENT DEFECTSDISEASE COMMON NAME ICD 9 CODE

C1 Esterase Inhibitor Deficiency Hereditary Angioedema 277.6

Complement Component Deficiencies(e.g. C1, C2, C3, C4, C5, C6, C7, etc.)

Complement Deficiency 279.8

20 IMMUNE DEF IC I ENCY FOUNDAT ION

Part B: Management, Expectations,Complications and Long TermMonitoringProphylactic antibiotics may be appropriate for deficienciesof any of the components of the complement cascade.Meningococcal vaccine and/or antibiotic prophylaxis maybe helpful for any person diagnosed with a C5 through C9deficiency.

All complement deficient patients should receiveimmunization with Prevnar® or Pneumovax or both forpneumococcal infection prevention. Early recognition offevers and prompt evaluation (including blood cultures) isvery important.

Complications of complement deficiency includeautoimmune disease, especially systemic lupuserythematosus, lupus-like syndromes, glomerulonephritis,and infections.

Mannose binding lectin, a protein of the innate immunesystem, is involved in opsonisation and phagocytosis ofmicro-organisms. Most of those with the Mannose BindingLectin defect are healthy except for skin infections, butsome resemble patients with early complement componentdefects. In the setting of recurrent infection with suspectedmannose binding lectin deficiency, a specialty laboratory(not a commercial one) must diagnose this defect.

Part C: Practical Aspects of GeneticCounselingThe genetic basis is known for all of the complementdefects but testing is only available in specializedlaboratories. All forms of inheritance have been reportedfor the complement defects and it is very important todetermine the specific complement factor involved as wellas its molecular basis.

The genetic basis of hereditary angioedema is known andfollows autosomal dominant inheritance. Please see thegeneral genetics section for a more complete descriptionof autosomal dominant inheritance. Family history isimportant in the evaluation of angioedema. Genetic testingis available for C1 Esterase Inhibitor deficiency and can beimportant in distinguishing the hereditary form of thedisorder from the acquired forms.

Part D: Frequently Asked Questions1. Can my child receive all types of vaccines?

Yes, individuals with complement defects usually have normal T and B cell function.

2. Are there infection risks if my child with a complement defect attends public school or goes to public places?No, in general the problems with infections are due to those that your child would come in contact with in a variety ofphysical settings. However, if there is a known outbreak of pneumonia or meningitis in your community, it may beprudent to keep your child at home out of the school environment and administer antibiotics recommended by thepublic health authorities.

Complement ScreeningAssays: CH50, AH50Specific Assays:

Complement Components

Angioedema, laryngealedema, abdominal pain

Laboratory Tests

Ear infections, PneumoniaBacteremia, Meningitis,Systemic Gonorrhea

C1 Esterase Inhibitor

Prophylaxis withAndrogens and/or

EACA, Infusion of C1Esterase Inhibitor for

Acute Attacks

Prophylactic Antibiotics,Immunize with

pneumococcal and N.meningitidis vaccinesMonitor for Autoimmune

Diseases

Treatment

Laboratory Tests

Treatment

D IAGNOST IC & CL IN ICAL CARE GU IDEL INES 21

COMPLEMENTCOMPONENT or

INHIBITOR DEFECTS

If abnormal, refer to an immunologist for further evaluation, diagnosis and treatment

22 IMMUNE DEF IC I ENCY FOUNDAT ION

Due to the genetic nature of the primary immunodeficiencydiseases, genetic counseling for the individual affected by thesediseases, as well as family members, is very important inproviding comprehensive care. Genetic counseling is typicallyprovided once the individual has been diagnosed with a specificprimary immunodeficiency disease. While most immunologists areknowledgeable about the genetic aspects of primaryimmunodeficiency disease, it is sometimes helpful to refer theindividual or family member to a genetic counselor who hasexpertise in providing complex information in an unbiased andeasily understood manner. Issues addressed in geneticcounseling for a primary immunodeficiency disease shouldinclude:

� Discussion of the diagnosis and the gene(s) responsible for thedisorder, if known.

� Determination of available molecular genetic testing forconfirmation of the diagnosis, if applicable, depending on thedisorder in question.

� An accurate intake of the patient’s family history, preferably inthe form of a pedigree.

� Determination and discussion of inheritance pattern andrecurrence risk for future children.

� Identification of family members who may be at risk of beingaffected with the disorder or at risk of being carriers.

� Brief discussion of the availability of prenatal diagnosis optionsfor the particular primary immunodeficiency. This can bediscussed again in more detail in future genetic counselingsessions when appropriate.

� Discussion of whether the family should save the cord blood offuture infants born to them. If the infant is affected, this wouldnot be helpful. If the infant is normal, the cord blood could beused as a source of stem cells for affected HLA-identicalmembers of the family who might need a transplant for immunereconstitution.

Patterns of InheritanceThe pattern of inheritance is very important when evaluating thepatient with a primary immunodeficiency disease. Many of theprimary immunodeficiency diseases follow X-linked recessiveinheritance. This means that the genes responsible for thesedisorders are located on the X chromosome and these conditionspredominantly affect males. Affected males have either inheritedthe gene defect from their mothers who were carriers of the genedefect or the gene defect occurred as a new mutation for the firsttime in the affected male.

About one third of all X-linked defects are identified as newmutations. In these cases, the mothers are not carriers or are thefirst affected (carrier) member of the family and the family historyis otherwise negative. Female carriers of the gene defect do nottypically show clinical symptoms. However, half of all boys born tofemale carriers may be affected with the disorder and half of thedaughters may be carriers like their mothers. Therefore, in familieswith X-linked disorders, it is important to determine whether thegene defect is inherited or is a new mutation, because this willgreatly affect the recurrence risk to other family members.

The other most common pattern of inheritance for primaryimmunodeficiency diseases is autosomal recessive. Disordersfollowing this pattern are caused by gene defects on any of the 22pairs of numbered chromosomes (not the X or Y) and therefore,affect both males and females. In this type of inheritance, thecondition is only expressed when both parents are carriers of thegene defect and both have passed the defective gene on to theirchild. These couples have a one in four chance of having anaffected child with each pregnancy.

P R A C T I C A L A S P E C T S O F G E N E T I C C O U N S E L I N G :G E N E R A L C O N S I D E R A T I O N S

Normal Affected Normal CarrierMale Male Female Female

Normal Affected Carrier Normal Affected CarrierMale Male Male Female Female Female

X-LINKED RECESSIVE INHERITANCE

AUTOSOMAL RECESSIVE INHERITANCE

D IAGNOST IC & CL IN ICAL CARE GU IDEL INES 23

Some primary immunodeficiency diseases follow autosomaldominant inheritance. These disorders are caused by genedefects on any of the numbered chromosomes and affectboth males and females. Unlike autosomal recessiveinheritance, only one copy of the gene defect needs to bepresent for the condition to be expressed in an individual.The defective copy overrides the individual’s normal copyof the gene. Individuals affected with these disorders havea 50% chance of passing the gene defect on to each oftheir children, regardless of gender. It is important to notethat some of these disorders occur as new mutations in theaffected individual and a family history may be negative.

A number of factors complicates genetic counseling forprimary immunodeficiency diseases. It is important that theprocess of genetic counseling for primaryimmunodeficiency diseases be done by either animmunologist or genetic counselor knowledgeable aboutthe specific intricacies of these disorders. Some of thecomplicating factors include:

� Primary immunodeficiency diseases are a group of morethan 150 different disorders and there are at least thatmany genes involved in these disorders.

� Some primary immunodeficiency diseases have thesame or similar clinical presentation, but different geneticcauses. This impacts the accurate determination ofinheritance pattern and recurrence risk to other familymembers.

� The genetic basis is still not known for many of theprimary immunodeficiency diseases, including some ofthe most common disorders, making it difficult toaccurately determine inheritance patterns and risk toother family members. This also makes it difficult to offerprenatal diagnostic options.

� Very few commercial laboratories perform moleculardiagnostic procedures for primary immunodeficiencydiseases and, for those that do, costs may be $2500-$3000 or more per family. Genetic testing is alsopossible in some research laboratories. Theseconsiderations may influence accessibility to testing aswell as timely receipt of test results. For a current list oflaboratories performing genetic testing of primaryimmunodeficiency diseases, consult your immunologistor contact the Immune Deficiency Foundation.

Genetic counseling also involves a psychosocialcomponent. This is true when providing genetic counselingto families affected by the primary immunodeficiencydisorders. The emotional aspect of having a geneticdisease in the family can be a heavy burden and this canbe explored in a genetic counseling session. In addition,the discussion of prenatal diagnostic options can be asensitive topic, since interruption of a pregnancy may be aconsideration. Prenatal diagnosis for primaryimmunodeficiency diseases may be an option if the geneticdefect is known in the family. This could be done through achorionic villus sampling performed in the first trimester ofpregnancy or through amniocentesis performed in thesecond trimester. Each of these procedures has a risk ofmiscarriage of the pregnancy associated with it, so theserisks need to be discussed thoroughly by the geneticcounselor. Prenatal diagnosis for a primaryimmunodeficiency disease may be considered when acouple wants to better prepare for the birth of an infant withthe disease in question. For example, knowing that a fetusis affected can give a couple time to start looking for amatch for a bone marrow donor if this is the therapy for thedisease. Knowing that a fetus is unaffected can offer greatrelief to the couple for the rest of the pregnancy. Prenataldiagnosis may also be considered when a couple wouldchoose to terminate a pregnancy of an affected fetus.Again, these considerations are thoroughly discussed in agenetic counseling session.

Finally, the discussion of gene therapy may be addressedin the genetic counseling of a family affected by a primaryimmunodeficiency disease. The anticipation is that genetherapy will become available for several diseases over thecoming years. However, even if the treatment is perfectedand found to be safe, it cannot be done unless theabnormal gene is known in the family.

P R A C T I C A L A S P E C T S O F G E N E T I C C O U N S E L I N G :G E N E R A L C O N S I D E R A T I O N S

24 IMMUNE DEF IC I ENCY FOUNDAT ION

Diagnosis InformationPatients need a hard copy description of their diagnosisand therapy and/or a MedicAlert badge (if applicable, areavailable at www.medicalert.org). In addition, individualsshould consider acquiring a Personal Health Key from theMedicAlert organization. This USB enabled key stores yourhealth record and can be carried on a key chain or in apurse.

Travel RecommendationsTravel outside the United States may require medicalregimens or vaccinations. Patients should consult with theirimmunologist to determine which vaccines can be safelyadministered and about the advisability of travel to variousgeographic areas of the world. As an example, be awarethat yellow fever vaccine is a live vaccine so it should notbe given to patients with T cell defects or members of theirimmediate household. In addition, IVIG would be of nobenefit for protection against yellow fever, as it lacksantibody to this viral agent.

Psychosocial ConcernsThe challenges of living with a primary immunodeficiencydisease can cause significant stress and have a greatimpact on the psychological well being of the personaffected with the disease and his/her caregivers and familymembers. Learning effective coping strategies can benefitall who are affected by these chronic illnesses. Establishinga good support system through family members, friends,health care team members and other peers affected byprimary immunodeficiency disease is essential to copingeffectively with the disease. It is important for health careproviders to pay close attention to signs of more seriouspsychological concerns, such as clinical depression, in apatient affected by a primary immunodeficiency or his/hercaregiver. This recognition can help the individual andfamily seek appropriate intervention in a timely manner. TheImmune Deficiency Foundation provides peer support byconnecting patients and their families with trainedvolunteers who have gone through similar situation to shareexperiences, encouragement and understanding. Pleasecontact the Immune Deficiency Foundation for moreinformation on this resource.

EducationThe transition from infant/toddler to school aged child canbe particularly challenging for a family affected by aprimary immunodeficiency disease. Communicationbetween parents and caregivers, the health care team andschool professionals is very important. This should includeeducating school personnel about the child’s particulardisease, management of infections, vaccine restrictions,prescribed therapy and precautionary measures that canbe taken to minimize infection in the school. Parents andhealth care providers should be familiar with the federalregulations enacted to promote equal education for childrenwith chronic diseases, such as primary immunodeficiencydiseases, that may qualify as disabilities. For moreinformation about these regulations, please contact theImmune Deficiency Foundation.

EmploymentAdults with primary immunodeficiency diseases aresometimes faced with the problem of employmentdiscrimination because of their diseases. Both patients andhealth care providers should be familiar with the Americanswith Disabilities Act. It protects U.S. citizens with healthconditions such as primary immunodeficiency diseases thatmay qualify as disabling conditions. For more informationabout federal regulations, please contact the ImmuneDeficiency Foundation.

L I F E M A N A G E M E N T C O N S I D E R A T I O N S

H E A L T H I N S U R A N C E

D IAGNOST IC & CL IN ICAL CARE GU IDEL INES 25

Great progress has been made in the treatment of primaryimmunodeficiency diseases. Life-saving therapies are nowavailable for many of the primary immunodeficiency diseases.However, primary immunodeficiency diseases differ from acutehealth conditions, as many of the therapies necessary to treatthese conditions are life-long. Therefore, it is essential thatpatients affected by these diseases have adequate healthinsurance coverage for these chronic therapies. In many cases, iftherapy is not administered on a regular basis, the cost of healthcomplications and subsequent hospitalizations could be extremelyburdensome.

Reimbursement and coverage of the treatments and services forprimary immunodeficiency diseases can vary considerably,depending on the type of health insurance a patient has.Therefore, maintenance of health insurance coverage requires aclose working relationship on the part of the patient, the healthcare provider and the health insurance administrator. Patients ortheir caregivers need to pay particular attention to the followingissues when working with their health insurance providers:

� Obtain a complete copy of the patient’s health insurance policyand understand services and treatments that are coveredunder the policy and those that are excluded.

� Know the patient’s specific diagnosis, including the ICD-9 codefor the diagnosiis. This information is available through thephysician’s office.

� Know if the insurance policy requires physician referrals and/orprior authorization for coverage of medical treatments, servicesor procedures before administration of the treatment isscheduled to take place.

� Consider establishing a case manager through the healthinsurance provider to maintain consistency when seekingadvice on the patient’s policy.

� Maintain a good understanding of out-of-pocket expenses,includin annual deductible amount, coinsurance amount andcopayments for prescription drugs, office visits and any otherservices.

� Know if the health insurance policy has a lifetimelimit/maximum on benefits and if so, know the maximumamount.

� Know if the health insurance policy has any pre-existingcondition waiting periods.

� Know patients’ rights under the Health Insurance Portabilityand Accountability Act (HIPAA) and how these protectinsurance coverage.

� If the patient is covered by Medicare, selecting the option ofPart B coverage is necessary for proper reimbursement ofmany of the therapies for primary immunodeficiency diseases.Additionally, since coverage of these therapies is usuallylimited to 80%, it is also important that a patient considerselecting a Medigap policy to help defray the cost of the 20%for which the patient is typically responsible.

Since reimbursement for therapies is constantly changing, it isimportant to keep up with any changes in each individual’s healthinsurance policy. In some cases, coverage for therapies may bedenied and the patient may have to appeal for reconsideration ofcoverage. Patients should read their health plan’s Summary PlanDocument to know the appeals process and timelines associatedwith filing an appeal. Resources are often available for this type ofassistance through manufacturers of the therapies. In addition, theresources below can be of assistance to patients going throughthis process. Sample letters for patients and providers areattached below for guidance through the insurance appealsprocess.

� Immune Deficiency Foundation:www.primaryimmune.org or (800) 296-4433

� State Departments of Insurance:www.naic.org/state_web_map.htm

� ww.cms.hhs.gov

How to Appeal Health InsuranceImmunoglobulin DenialsImmunoglobulin (IG) therapy is an expensive therapy.Unfortunately, some insurance companies deny IG therapy forpatients with primary immunodeficiency until the insurerunderstands the rationale behind this life sustaining therapy.Insurers are very reluctant to approve expensive payments peryear where indications are not substantiated.

Listed below are tips that have been successful in helping tooverturn health insurance IG denials. The appeal should be short,succinct and carefully documented.

� Keep in mind that you have a very short amount of time(probably only a few minutes) of the Medical Director’sattention.

� Provide well-accepted diagnostic studies, which are in thepractice guidelines.

� Provide standards of practical criteria to support the laboratorystudies.

26 IMMUNE DEF IC I ENCY FOUNDAT ION

� Provide proof and documentation of serious infections andcomplications, which have not been responsive to appropriatemedical and /or surgical intervention; include clearradiographic evidence of persistent disease, e.g. lungs,sinuses et al, and clinical documentation of infections etc.

� Focus on the rationale for IG therapy; a doctor’s letter thatstates, “because it is medically necessary” is not specificenough. Precise statements, such as 3 episodes ofpneumonia with fever to 102, or chest x-ray showed lobarpneumonia and xx days of antibiotics were required, areneeded.

� Keep in mind that the insurance companies are reviewingthousands of appeals; therefore, the larger appeal packets willbe put to the side. Remember, the shorter the appeal, theshorter the turn-around-time for a response.

� When concluding the letter, add the names of immunologiststhat have completed the scientific research on the diagnosis inquestion, should the insurer request a peer review. Forexample “Should you have any questions, I would request apeer review by either Dr. John Smith or Dr. Ann Jones from theUniversity School of Medicine.”

For additional information:1. To view sample appeal letters, visit the IDF Website at

www.primaryimmune.org

2. References to attach to appeal letter can be found atwww.pubmed.com PubMed is a service of the U.S. NationalLibrary of Medicine that includes over 18 million citations fromMEDLINE and other life science journals for biomedicalarticles back to 1948.

3. The IDF Consulting Immunologist Program offers freephysician-to-physician consults; consults or second opinionson issues of diagnosis, treatment and disease management;and access to a faculty of recognized leaders in clinicalimmunology 1-800-296-4433.

4. The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology(AAAAI) Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases Committeecreated an IVIG toolkit to educate payers and regulators whoare responsible for coverage determinations and aidphysicians in the safe, effective and appropriate use of IVIG forpatients with primary immunodeficiency diseases. The IVIGtoolkit has been approved by the AAAAI Board of Directors,and endorsed by the Clinical Immunology Society and theImmune Deficiency Foundation. The IVIG toolkit includes:

� Eight guiding principles for safe, effective and appropriateuse of IVIG

� Guidelines for the site of care of the administration of IVIGtherapy for patients with PIDD