Competency-Based Approach: the Problematical of Assessment ...

Herpes simplexencephalitis: longtermmagnetic resonance ...infection. The diagnosis of herpes simplex...

Transcript of Herpes simplexencephalitis: longtermmagnetic resonance ...infection. The diagnosis of herpes simplex...

14ournal ofNeurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 1994;57:1334-1342

Herpes simplex encephalitis: long term magneticresonance imaging and neuropsychological profile

N Kapur, S Barker, E H Burrows, D Ellison, J Brice, L S Illis, K Scholey, C Colbourn,B Wilson, M Loates

Wessex NeurologicalCentre, Southampton,UKN KapurS BarkerJ BriceL S IllisK ScholeyM LoatesNeuropathologyDepartment,Southampton GeneralHospital,Southampton, UKD EllisonKing Edward VIIHospital, Midhurst,UKE H BurrowsApplied PsychologyUnit, Cambridge, UKB WilsonDepartment ofPsychology,University ofSouthampton, UKC ColboumCorrespondence to:Dr Narinder Kapur, WessexNeurological Centre,Southampton GeneralHospital, Southampton,S09 4XY, England.Received 20 January 1994and in revised form12 April 1994.Accepted 19 April 1994

AbstractThe first comprehensive in vivo docu-mentation of the long term profile ofpathological and spared tissue is des-cribed in a group of 10 patients with adiagnosis of herpes simplex encephalitis,who were left with memory difficulties asa major residual sequel of their condi-tion. With a dedicated MRI protocol,which included high resolution images oftemporal lobe and limbic system areas,data are provided on structures that haverecently gained importance as anatomi-cal substrates for amnesia. The majorfeatures of the lesion profile were: (1)unilateral or bilateral hippocampal dam-age never occurred in isolation, and wasoften accompanied by damage to theparahippocampus, the amygdala, spe-cific temporal lobe gyri, and the temporalpoles; (2) the insula was always abnor-mal; (3) neocortical temporal lobe dam-age was usually unilateral or asymmetric.It never occurred in isolation, and wasinvariably associated with more medialpathological changes; (4) anterior andinferior temporal lobe gyri were damagedmore often and more severely than poste-rior and superior temporal lobe gyri; (5)pronounced abnormality was often pre-sent in the substantia innominata (regionof the basal forebrain/anterior perforatedsubstance); (6) there was evidence of sig-nificant abnormality in the fornix; (7)there was evidence of damage to themammillary bodies; (8) thalamic nucleiwere affected in around 50% of cases,with damage usually unilateral; (9)frontal lobe damage was present in a fewpatients, and affected medial areas morethan dorsolateral areas; (10) there wassome involvement of the striatum,although this was usually unilateral andmild; (11) there was usually limitedinvolvement of the cingulate gyrus and ofthe parietal and occipital lobes; (12) thecerebellum and brain stem were neverdamaged. Lesion covariance analysisindicated a close relation between thepresence of abnormalities in temporallobe and limbic-diencephalic regions.Unlike severe head injury, lesions inthe temporal pole were not associatedwith the presence of lesions in theorbitofrontal cortex. Long term neuro-psychological impairments were charac-terised by a dense amnesia in 60% ofcases, and a less severe but noticeable

anterograde memory impairment in theothers. Naming and problem solvingdeficits were found in a small number ofcases. Only two patients were able toreturn to open employment. Severity ofamnesia showed a significant relationwith severity of damage to medial limbicsystem structures such as the hippocam-pus, with bilateral damage being particu-larly important. By contrast, there was aminimal relation between memory lossand severity of damage to the thalamus,to lateral temporal lobe areas, or to thefrontal lobes.

(_ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1994;57: 1334-1342)

Herpes simplex encephalitis is one of the mostcommonly recognised forms of viralencephalitis. Whereas there have been welldocumented case studies,' 2 there is little inthe way of detailed documentation of longterm lesion profiles and recovery of neuropsy-chological functioning in a series of patientswho have survived the initial illness.

Both CT and postmortem studies3 havehighlighted the involvement of limbic systemand temporal lobe structures in herpes sim-plex encephalitis. Studies with CT lackanatomical precision, particularly evident bythe absence of high resolution images in thecoronal plane-this plane is often critical fordetailed examination of limbic structures suchas the hippocampus. Postmortem studies sufferfrom the inevitable selection bias in suchsamples, and from the time lapse betweenclinical examination and anatomical investiga-tions. The availability of MRI provides aunique opportunity to examine in vivo thepattern and severity of lesions in this group ofpatients. Magnetic resonance imaging is aparticularly useful procedure for examiningsuch lesions in view of the high signal yieldedby abnormal brain water content. Magneticresonance imaging in relation to patients withherpes simplex encephalitis has so far beenprimarily used as an improved diagnostic toolin the acute management of such patients.4-5It has also been shown to be useful in moni-toring recovery of lesion severity with time.6

At the neuropsychological level, there havebeen several important single case or smallgroup studies, of patients with herpes simplexencephalitis.7-'0 These studies have been valu-able, but have been limited by the small samplesizes, the selection bias in the patient samples,the absence of a dedicated MRI protocol to

1334

on April 28, 2021 by guest. P

rotected by copyright.http://jnnp.bm

j.com/

J Neurol N

eurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.57.11.1334 on 1 N

ovember 1994. D

ownloaded from

Herpes simplex encephalitis: long term magnetic resonance imaging and neuropsychological profile

examine closely limbic system structures, andthe limited anatomical description of thosestructures that were damaged or spared by theinfection.The aims of the present long term study of

patients with herpes simplex encephalitis werethreefold: Firstly, we aimed to provide a neu-roanatomical profile of abnormal and sparedtissue, as indicated by a dedicated MRI proto-col. We paid particular attention to theintegrity of candidate anatomical structuresthat in recent years have come to assume criti-cal importance in animal and human lesionstudies of memory disorder. We also exam-

ined lesion covariance between selectedanatomical regions, in view of the finding thatin certain types of cerebral pathology, such as

severe head injury, particular associations anddissociations may emerge between MRI basedlesion distribution. "I

Secondly, we wished to ascertain the extentof recovery of cognitive functioning by provid-ing an outline of the profile of patients in a

series of neuropsychological tests. In thisstudy, we concentrated on anterograde mem-ory and general cognitive functioning. Otherareas, such as semantic memory and therelated area of retrograde amnesia, requiredetailed investigations in their own right, andare only briefly covered in this report. Thirdly,we aimed to ascertain which, if any, correla-tions might be found between anterogradememory loss and lesions in specific anatomi-cal regions such as the limbic system. Someinvestigators'2 13 have shown that meaningfulcorrelations can be derived between MRIlesion measures and memory test perfor-mance. In these papers, and in similar MRIstudies,'4 tissue abnormality was simply pre-

sumed from reduced tissue volume. Whereas

patients with herpes simplex encephalitis aresimilar to other groups such as those withAlzheimer's disease or alcoholic Korsakoffpatients in having several coexistent sites ofpathology, the particular advantage in study-ing patients with herpes simplex encephalitisis that the nature of the inflammatory changesin brain water content result in their lesionprofile being clearly shown as well demarcatedbright signals on T2 image sequences, and asdark signals on Ti sequences. Identificationof the extent and severity of lesion profiles canthus be made with more confidence than inmany other groups of patients. Becausepatients with herpes simplex encephalitis gen-erally comprise a younger age group, they alsotend not to have ischaemic or other changesthat are associated with an older population ofsubjects.

Patients and methodsPATIENTSTen patients who had a diagnosis of herpessimplex encephalitis, who were at least sixmonths post-recovery, and who were left withsignificant memory difficulties, formed thegroup for the present study (table 1). Weincluded cases where there was clear evidencefor the presence of a herpes simplex viralinfection. The diagnosis of herpes simplexencephalitis is often problematical, even inseropositive cases, and we therefore also tookinto account clinical and neurophysiologicalfeatures, as well as virological data, for eachcase. For most of the cases, we were able totrace the relevant pathological records thatindicated viral confirmation of a diagnosis ofherpes simplex encephalitis, although we alsoincluded two patients (cases 2. and 5 in

Table 1 Clinical and neuropsychological profiles of cases of herpes simplex encephalitisDuration of Amnesia NART Verbal IQ Performance IQ

Age and memory severity * estimated subtest subtest Picture CardCase sex disorder (y) score (124) IQ score scores scores naming sorting

1 53 7 0 106 Infor = 8 Pict ar = 8 Impaired NormalMale Arith = 12 B des = 15 2/30

Simil = 6t Dsy= 112 39 15 1 117 Infor = 6t Pict ar = 8 Normal Pronounced

Female Arith = 8 B des = 8 11/30 impairmentSimil = 7 D sy = 8

3 42 10 2 113 Infor = 7 Pict ar = 8 Normal NormalFemale Arith = 12 B des= 10 15/30

Simil = 11 D sy = 144 45 3 3 110 Infor = 5t Pict ar = 8 Impaired Mild

Female Arith = 10 B des = 9 2/30 impairmentSimil = 7 D sy = 10

5 59 7 4 122 Infor = 10 Pict ar = 14 Normal NormalMale Arith = 12 B des= 12 21/30

Simil = 13 D sy = 146 39 4 7 (Long- Infor = 5t Pict ar = 13 Impaired Normal

Male standing Arith = 6t B des = 12 5/30dyslexia) Simil = 8 D sy = 6t

7 70 3 9 98 Infor = 12 Pictar = 7 Normal MildMale Arith = 12 B des= 11 13/30 impairment

Simil= 11 Dsy= 88 57 2 12 (Dysphasia Infor = 5t Pict ar = 12 Impaired Normal

Female affected test Arith = 7 B des = 12 0/30score) Simil= 7 Dsy= 11

9 65 7 13 89 Infor = 7 Pict ar = 7 Normal PronouncedMale Arith = 9 B des = 8 11/30 impairment

Simil = 7 D sy = 910 24 1 23 107 Infor = 9 Pict ar = 9 Normal Normal

Female Arith = 11 B des= 10 22/30Simil= 10 Dsy= 7

* Severity of amnesia was based on a composite score reflecting performance on the Wechsler memory scale-revised, the recognitionmemory test, and the current awareness test. t Impairment. Infor = Information; Arith = Arithmetic; Simil = Similarities;Pict ar = Picture arrangement; B des = Block design; D sy = Digit symbol.

1335

on April 28, 2021 by guest. P

rotected by copyright.http://jnnp.bm

j.com/

J Neurol N

eurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.57.11.1334 on 1 N

ovember 1994. D

ownloaded from

Kapur, Barker, Burrows, Ellison, Brice, Illis, et al

table 1) for whom we were unable to locatethe relevant virological data at the time ofadmission, but where herpes simplexencephalitis was the firm diagnosis reachedafter their hospital admission, and where therewere strong clinical and neurophysiologicalgrounds for supporting such a diagnosis. Allof our patient sample could therefore be classi-fied as definite or probable herpes simplexencephalitis. There was no difference in clini-cal or anatomical profile between the eightdefinite cases and the two probable cases ofherpes simplex encephalitis.

NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL TEST PROCEDURESPatients were given the national adult readingtest,'5 a short form of the Wechsler adult intel-ligence scale-revised, the Wechsler memoryscale-revised, the recognition memory test,16the graded naming test,'7 and the modifiedcard sorting test.'8 As the orientation subtestof the Wechsler memory scale-revised is partlycultural-specific to the United States, a shortorientation test was drawn up and given topatients-it assessed orientation for place(town), year, month, day of the week, andcurrent prime minister of Great Britain. Ascore of 1 or 0 was given, resulting in a maxi-mum score of 5.

Table 1 gives our patients' general neu-ropsychological test scores. As some patientswith herpes simplex encephalitis may showsurface dyslexia,' and as the national adultreading test assesses reading of irregularwords, its scores may not meaningfully relateto levels of premorbid cognitive functioning.Although other estimates of premorbid cogni-tive functioning may also have their own limi-tations, we decided to base our interpretationsof intellectual impairment on performance onindividual subtests of the Wechsler adultintelligence scale-revised. A dagger marksthose age related subtest scores from the scalewhere patients performed more than one SDbelow the mean score of 10 that was derivedfrom the distribution of scores in the original

normative study (less than 7). In the case ofverbal IQ subtests, the most common testto show an impairment was the informationsubtest, with 40% of patients having a score of5 or 6. This test mainly assesses generalknowledge that would normally have beenacquired before the patient's illness, and tothis extent it will pick up retrograde andsemantic memory deficits that are present. Inthe case of performance subtests, only onepatient obtained an age scaled score below 7,this being for the digit symbol subtest. Fortyper cent of patients showed a naming deficiton the picture naming task-guidelines pro-vided in the manual were followed fordeciding if a score represented a deficit.Impaired performance primarily consisted ofa naming score lower than would have beenexpected on the basis of the patient's readingscore and educational background, and whichresulted from paraphasic errors. It is worthnoting that most of the patients with namingdeficits did not have clinically obvious dys-phasia during their conversational speech. Asimilar number of patients were impaired tosome degree on the modified card sorting test.An impairment was considered to be presentwhen patients sorted into less than four cate-gories or had more than 50% perseverativeerrors.

Table 2 shows the detailed memory testresults for the Wechsler memory scale-revisedand the recognition memory test. Sixty percent of cases displayed a dense amnesia,defined as a delayed memory quotient of 50or less (the delayed memory quotient does notyield scores lower than 50). A compositeamnesia severity score was derived that tookinto account performance on the Wechslermemory scale, the recognition memory test,and the current awareness test. This score wasderived by examining each patient's test scoreacross the 24 memory tests and subtests inquestion, rating the score as 0 or 1 according towhether it was impaired or normal, and thensumming scores across the various subtests.

Table 2 Memory test scores ofpatients with HSE

WMS-R WMS-R WMS-R WMS-R WMS-R RMT Currentverbal visual general attention/ delayed (age- awarenessmemory memory memory concentration recall scaled test

Case quotient quotient quotient quotient quotient score) (max = 5)

1 <50 <50 <50 105 <50 Faces <4 1Words <4

2 <50 <50 <50 79 <50 Faces <4 0Words <4

3 62 <50 <50 100 <50 Faces <4 4Words< 4

4 <50 <50 <50 99 <50 Faces <4 2Words <4

5 58 75 50 108 <50 Faces <4 0Words <4

6 58 77 56 81 76 Faces <4 5Words <4

7 78 82 72 113 <50 Faces 5 3Words <4

8 <50 98 52 95 59 FacesI1 4Words 9

9 103 110 103 72 100 Faces <4 5Words <4

10 79 80 77 98 75 Faces 5 5Words 13

WMS-R=Wechsler memory scale-revised; RMT=recognition memory test.

1336

on April 28, 2021 by guest. P

rotected by copyright.http://jnnp.bm

j.com/

J Neurol N

eurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.57.11.1334 on 1 N

ovember 1994. D

ownloaded from

Herpes simplex encephalitis: long term magnetic resonance imaging and neuropsychological profile

Each patient could receive a maximum scoreof 24.

Amnesia was by far the most disablingdeficit found in our patient group. It is of notethat two of the three most severely amnesicpatients (case 2 and case 3) had normal pic-ture naming scores, and two similarly amnesicpatients (case 1 and case 3) had normal per-formance on the modified card sorting test.

In terms of everyday adjustment, only twopatients were able to return to open employ-ment. One patient (case 6) was employed in aclosely supervised post with British Rail, anddid relatively routine tasks that did not tax hismemory. The other patient (case 10), whohad the least severe memory impairment inthe series, returned to her work as a care assis-tant, and was able to cope with the help ofmemory aids.

MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING PROTOCOLMagnetic resonance imaging was carried outwith a Philips 0 5 Tesla Gyroscan T5 scanner.Our protocol was designed to obtain both anoverview of the entire brain and to obtaindedicated views of candidate anatomicalregions important for memory, such as struc-tures in the limbic-diencephalic system, thetemporal lobes, and the frontal lobes.An initial set of "survey" sagittal scans was

carried out to enable planning of dedicatedcuts. This survey had nine cuts.A whole brain axial scan was then carried

out. This comprised proton density and T2weighted 5 mm images with an 0 5 mm inter-slice gap (TR = 2129; TE = 90/30; matrixsize = 205 by 256; field of view = 220).Twenty slices were obtained, with the centreline being positioned along the axis of the cor-pus callosum.A coronal inversion recovery Ti weighted

scan was then performed, covering the ante-rior two thirds of the brain (TR = 1500; TE =30; TI = 400; matrix size = 205 by 256; fieldof view = 220). Around 17 slices wereobtained, each of 5 mm width and 1I0 mminterslice gap.

Finally, a sagittal scan was carried out withthe specific aim of imaging mid-line structuressuch as the mammillary bodies (TR = 523;TE = 25; matrix size = 205 by 256; field ofview = 250). This scan was Ti weighted, andhad 3 mm width slices, with a 0 3 mm inter-slice gap. The centre line for this scan, whichencompassed seven slices, was positioned tolie along the middle of the third ventricle.

IMAGE ANALYSESWe used image analysis procedures similar tothose of other studies.'9 20 Scans were inde-pendently assessed by three raters (DE, JB,and SB), who were all blind to the neuropsy-chological test results relating to individualpatients. All three raters had many years ofexperience in neuroanatomy and neuro-radiology, and when inspecting the scans theyhad available a number of anatomical atlasesand MRI reference texts to assist in their rat-ings.2'22 Initially, all scans were assessed byDE and JB. There was 80-90% agreement

between these two ratings. Where there wasdisagreement for a particular structure, thisarea was rated by SB, who was blind to theraw rating score from either of the two sets ofearlier ratings.A standard table of structures was provided

to each rater, who indicated whether therewas a mild or major abnormality in a particularstructure. For initial ratings by one of theraters, we used normal images from MRatlases for reference, but for the final sets ofratings we only used data that were obtainedon the basis of comparisons between herpessimplex encephalitis images and those of agematched control subjects. In all, six controlsubjects were scanned (four men 18, 45, 55,and 70 years old, and two women 31 and 39years old), so as to provide appropriate com-parative images of the normal appearance ofstructures. For a specific comparison, the sub-ject for a matched control scan was alwaysaged within five years of a particular patientwith herpes simplex encephalitis, except forcase 10 where the relevant control subject wassix years younger. All control subjects werecarefully screened to ensure the absence ofany neurological illness or injury, or alcoholabuse. The scan protocol given to controlsubjects was identical to that received bypatients with herpes simplex encephalitis.

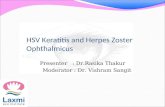

ResultsMAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING FINDINGSDetailed neuroanatomical profiles for individ-ual structures were mapped on to medial (figl(upper) and surface (fig 1(lower)) views ofthe brain. These show the number of patientswith lesions in specific brain regions. Forillustrative purposes, we have collapsed mildand major lesions into one category. Datafrom the four thalamic areas have been com-bined, as have data from the anterior and pos-terior cingulate gyrus. This anatomical profileshows the invariable damage in the hippocam-pus and adjacent structures such as the amyg-dala and the insula, the greater involvement ofanterior and inferior temporal lobe gyri, andthe damage often found in structures such asthe mammillary bodies and the anterior perfo-rated substance.The striatum, which is not displayed in the

figure, showed left sided damage in threecases, right sided damage in two cases, andbilateral damage in one case. The third ventri-cle was enlarged in seven cases. There wasbilateral enlargement of the lateral ventriclesin six cases, and unilateral (right sided)enlargement in three cases.

Lesion covariance between damage inselected anatomical regions was also assessed.The coincidence of lesions between six hemi-spheric sites and each of 10 target anatomicalstructures was computed as a binomial proba-bility (two tailed). The six hemispheric siteswere the right and left limbic-diencephalicsystems, right and left temporal poles, andright and left temporal lobes (excludingpoles). The 10 target anatomical structuresincluded these six areas, and also the right and

1 337

on April 28, 2021 by guest. P

rotected by copyright.http://jnnp.bm

j.com/

J Neurol N

eurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.57.11.1334 on 1 N

ovember 1994. D

ownloaded from

Kapur, Barker, Burrows, Ellison, Brice, Illis, et al

Figure 1 Illustrativemaps showing numbers ofpatients with lesions inspecific brain structures,displayed in (upper)midline and (lower)surface views. In the caseof a complex threedimensional structure suchas the human brain, werecognise thatfor purposesof illustration some featuresthat are drawn may berather arbitrary. Thus thetemporal pole,anteriorlposterior sectionsof temporal lobe gyri and ofthe hippocampus, and theuncuslentorhinal cortex arenot morphologically distinctstructures, but aredelineated here for purposesof highlighting the majorprofile of lesion damage. Inaddition, the insula liesinfolded deep below thecortical surface, and istherefore represented by astriped line.

Anterior Part or ostirrior ; rt oa

-lrppocarpuso-JlrDWCarrrL)tS

'-riht nor tlGros

:}arnprhppoca mpa Gyvrus

1. ,I-, e ;*

I>rcIsIicrria}l

*r il F 4 4\|

L<u Ic3Lll i LX S S XX~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~t- Iv

Substanha nnroirr ia{Yrirrr, S mri iarvTR dirs Oi

rAnaonorParForatdd Substarnce

: ~ ~~~ ~ ~~~~ ~ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~L

1 3~~~~ ~ ~3. l 3

R.W..f.,WR,I

nAterior Part u: Intefimr Posterior Part f1 Infsrieremporal Gyro Temporal Gvrus Temporal Gvyrts

.9h. 1t i.

`ostinra Pa rt oC Mir,11ar-arroa v-: So

4~~~ ~ ~

2 .d a n e22r,2a'!

Anterior Part of Superior Posterior Part of Superioir Dorsolatera3 ObltOfrbor a

Tsula ;-ritalAr OrTemporal Gyrus Temporal GyrUS tferreatho Surtacea ia raA(

left orbitofrontal regions, and the right andleft medial and dorsal frontal regions. For thepurposes of this analysis, the limbic-dien-cephalic system included the hippocampus,parahippocampal gyrus, uncus/entorhinal cor-tex, amygdala, substantia innominata, fornix,thalamus, mammillary bodies, and cingulategyrus. We examined those hemispheric sitesfor which there were at least six patients whoshowed lesions. We then ascertained whichstructures from the set of target anatomicalstructures would also show damage. Therewere significant contingent associationsbetween the presence of lesions in the rightand left limbic-diencephalic areas (p < 0-02);left limbic-diencephalic and left temporal poleareas (p < 0 04); left temporal pole and leftlimbic-diencephalic areas (p < 0 008); righttemporal lobe (excluding temporal pole) andright temporal pole areas (p < 0-008); lefttemporal lobe (excluding temporal pole) andright limbic-diencephalic areas (p < 0-03); left

temporal lobe (excluding temporal pole) andleft limbic-diencephalic areas (p < 003); andleft temporal lobe (excluding temporal pole)and left temporal pole areas (p < 0-03).

There was no significant lesion covariancerelating temporal lobe to frontal regions. Anotable finding relating to lesion dissociationwas that we had one patient with bilateraldamage in the mammillary bodies but a nor-mal fornix (case 5), and one patient withbilateral damage in the fornix, but normalmammillary bodies (case 6).

MEMORY-ANATOMY CORRELATIONSWe analysed our data both for group correla-tions between severity of damage in a definedanatomical area and degree of impairment on amemory task, and also for individual cases ofdissociations between anatomy profiles andmemory profiles. With a sample size ofonly 10 patients, it is not meaningful toderive memory-anatomy correlations for each

1 338

J.

j ..

.i., 3

21

i

.-

q, 1. :.

f--(..- 1.9 c, r

on April 28, 2021 by guest. P

rotected by copyright.http://jnnp.bm

j.com/

J Neurol N

eurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.57.11.1334 on 1 N

ovember 1994. D

ownloaded from

Herpes simplex encephalitis: long term magnetic resonance imaging and neuropsychological profile

individual structure. Of the wide range ofstructures that could be included, we concen-trated on those that have been noted in the lit-erature as associated with human memorydisorder. The frontal lobes were only partlydamaged in a few patients, and so there wereinsufficient data to yield meaningful correla-tions across subjects. We have therefore pre-sented data in respect of the followinganatomical areas: (1) the limbic-diencephalicsystem as a whole-this included the hip-pocampus, parahippocampal gyrus, uncus/entorhinal cortex, amygdala, substantiainnominata, fornix, thalamus, mammillarybodies, and cingulate gyrus; (2) the hippo-campal formation-the hippocampus, para-hippocampal gyrus and uncus/entorhinalcortex; (3) the thalamus; (4) the temporallobes, excluding medial structures. Weincluded the three major temporal lobe gyri,and also included the insula in view of itsproximity to temporal lobe neocortical struc-

tures and its frequent involvement in herpessimplex encephalitis.A score of 0 was ascribed to a structure that

showed no evidence of damage, a score of 1indicated the presence of a mild abnormality,and a score of 2 was allocated if there was pro-nounced abnormality. It was possible, there-fore, to obtain for individual structures indicesof right sided, left sided, and total amount ofabnormality. We also separately computed anindex of bilaterality of pathology by giving ascore of 0 if the lesion was unilateral, a scoreof 1 if there was a mild lesion on one side anda mild lesion on the other side, a score of 2 ifthere was a mild lesion on one side and a pro-nounced lesion on the other side, and a scoreof 3 if there was marked abnormality on bothsides.

In the case of memory test measures, weconsidered the following variables: (a) thefour memory quotients from the Wechslermemory scale-revised; (b) the faces recogni-tion memory age corrected percentile scorefrom the recognition memory test; (c) thewords recognition memory age-corrected per-centile score from the recognition memorytest; (d) the composite amnesia severity scoredescribed earlier; (e) performance on theinformation subtest of the Wechsler adultintelligence scale-revised - this provides a sim-ple index of general knowledge and semanticmemory that would have been intact in mostpatients before their illness. It therefore pro-vides a simple index of retrograde memoryloss.

Spearman rank correlation coefficientswere computed between memory test scoresand lesion indices. The Spearman test is aconservative statistic that only uses the ordinalproperties of data, and so it was particularlyappropriate with the type of data gathered inthis study.The most comprehensive index of memory

loss, that reflected performance over a widerange of memory tests, is the overall amnesiaseverity score. This showed the highest corre-lations with bilateral hippocampal damage(-0 97, p < 0 01) and bilateral limbic systemdamage (- 0-89, p < 0.01). Amnesia severityalso correlated with total limbic-diencephalicdamage (-O 86, p < 0 05), total hippocam-pal formation damage (-0-84, p < 005),and total temporal lobe damage (-0-67,p < 005).

Although measures of delayed retention areamong the most sensitive indices of memoryloss, the zero delayed recall scores of some ofour patients with herpes simplex encephalitisrenders this index less valuable than the overallamnesia severity score. Taking this intoaccount, the most sensitive single index ofmemory impairment from the Wechslermemory scale-revised, the delayed recall quo-tient, correlated best (-0-89, p < 0 01) withtotal amount of damage to the hippocampalformation. It also showed a correlation withbilateral limbic-diencephalic damage (- 0-82,p < 005), total limbic-diencephalic damage(-0-77, p < 0 05), and bilateral hippocampaldamage (- 0-78, p < 0 05).

1 339

--Nqimmw --r

on April 28, 2021 by guest. P

rotected by copyright.http://jnnp.bm

j.com/

J Neurol N

eurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.57.11.1334 on 1 N

ovember 1994. D

ownloaded from

Kapur, Barker, Burrows, Ellison, Brice, Illis, et al

It is of note that there was little evidence torelate material specific memory loss with uni-lateral damage. Indeed, visual memory quo-tient showed a number of significantcorrelations with left sided damage, perhapsreflecting the verbal loading on subtests in thisscale and the immediate rather than delayedretention that is measured by this quotient.These included correlations between visualmemory quotient and left sided limbicdiencephalic damage (-0 92, p < 0-01),bilateral limbic-diencephalic damage (- 0 70,p < 0 05), left sided hippocampal formationdamage (- 0-78, p < 0-05), bilateral hippo-campal formation damage (- 066, p < 0-05),and left sided temporal lobe damage (-0-80,p < 005). Verbal memory quotients corre-lated with bilateral limbic-diencephalicdamage (- 0-84, p < 0 05), total limbic-diencephalic damage (-0 79, p < 0 05),bilateral hippocampal damage (-0 90,p < 0-05), and total hippocampal damage(-0 77, p < 0-05). Also, faces recognitionmemory showed a significant correlationwith only one index of abnormality-namely,total limbic-diencephalic damage (- 70,p < 0 05).

Both left sided thalamic damage and lefttemporal lobe damage correlated with perfor-mance on the information subtest (-0-80,p < 0 05 and - 0 74, p < 0 05 respectively).We found an absence of any significant corre-lation between thalamic damage and antero-grade memory test scores. This was furtherborne out by an examination of individualcases: for the three most severely amnesicpatients in our series (cases 1, 2, and 3), boththe right and left thalamus were found to benormal. Although the number of cases withfrontal lobe damage was too small to enableus to carry out meaningful correlational analy-ses, it is worth noting that case 2 and case 5-who scored at floor on the delayed recallquotient-had normal frontal lobes. Case 1,who was the most severely impaired patient inour series, only had mild damage in the leftmedial frontal lobe. In the case of the twopatients referred to earlier with varyingdegrees of mammillary body and fornix dam-age, it was the patient with bilateral mammil-lary body damage and a normal fornix (case5) who had a more severe amnesia than thepatient (case 6) with bilateral fornix damageand normal mammillary bodies.

DiscussionIn a series of 10 cases, the profile of neuropsy-chological recovery after severe herpes sim-plex encephalitis infection was characterisedby pronounced memory impairment, with avariable degree of additional cognitive deficits.A dense amnesia was the most disabling of thehandicaps in the sample. Naming and prob-lem solving deficits were also found, but didnot seem to be as such a major handicap. Allbut two patients were unable to resume anyform of open employment. The anatomicallesion profile was characterised by damage tohippocampal and adjacent medial temporal

lobe structures, by pathology in anterior andinferior temporal lobe gyri, by involvement ofthe insula, by dissociable damage to the mam-millary bodies and fornix, and by lesions inthe anterior perforated substance. Lesioncovariance analysis showed associationsbetween damage in temporal and limbicstructures rather than between temporal andfrontal regions. Damage to medial limbicstructures correlated with severity of memoryimpairment, with hippocampal structuresrather than thalamic nuclei showing the clos-est association with severity of amnesia.Our findings largely confirm those made at

postmortem by Hierons et al.3 Selection pro-cedures are such that their sample of patientsprobably included more severe cases of herpessimplex encephalitis than the patients seen inour study. Even with this proviso, our lesionprofiles were strikingly similar to those foundby Hierons et al,3 and this conclusion holdstrue even if we restrict our comparison tocases in their study (cases 2, 4, and 9) whoseemed to have a relatively pure memory dis-order and who were therefore most compara-ble with our herpes simplex encephalitispopulation.Our MRI lesion profiles paralleled those

that have been documented in the acute,recovery phase of herpes simplex encephali-tis.5 Specific comparisons with individualstudies are difficult to make in view of differingimaging protocols and anatomical descrip-tions of lesions. It does seem that the majorpattern of lesions is similar in the acute and inthe chronic phases of herpes simplexencephalitis, but that the size of lesions in par-ticular regions, as well as the degree ofinvolvement of subcortical structures such asbasal ganglia, is somewhat attenuated in thechronic phase.

In our study, unilateral or bilateral hip-pocampal damage never occurred in isolation,and was often accompanied by parahip-pocampal abnormality, by damage to theamygdala, by variable damage to specific tem-poral lobe gyri, and by involvement of thetemporal poles. To this extent, the MRI pro-file in herpes simplex encephalitis differs fromthat found in paraneoplastic encephalitis,2'where there often seems to be more focaldamage that is restricted to the hippocampusand to immediately adjacent structures suchas the parahippocampal gyrus and the amyg-dala.The insula was always damaged in our

study. It is uncertain as to its precise role inhuman memory disorder, and recent studieshave in fact linked it to autonomic functionssuch as heart rate,24 to recovery of motor func-tion,25 and to multimodal sensory integra-tion.26

Because of the size of our patient sample,and due to the covariance of damage in adja-cent structures in the medial and lateral tem-poral lobe, anatomy-memory correlations inour study must be regarded as preliminary. It isof note, however, that some of our findingsdid confirm established relations from otherclinical and methodological approaches.

1 340

on April 28, 2021 by guest. P

rotected by copyright.http://jnnp.bm

j.com/

J Neurol N

eurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.57.11.1334 on 1 N

ovember 1994. D

ownloaded from

Herpes simplex encephalitis: long term magnetic resonance imaging and neuropsychological profile

Thus, we found that bilateral damage to thehippocampal formation showed the highestcorrelation with severity of amnesia.Bilaterality of damage rather than totalamount of damage seemed to be critical forthe severity of memory loss. By contrast,structures such as the thalamus and thefrontal lobes were minimally associated withseverity of memory loss. Damage to temporallobe gyri was also much less closely associatedwith severe anterograde memory impairment.Our findings confirm the primacy of medialtemporal lobe damage, especially bilateraldamage, in accounting for amnesia in patientswith temporal lobe abnormality, and comple-ment similar sets of data from other neurolog-ical conditions.27

Neocortical temporal lobe damage wasusually unilateral or significantly asymmetric.In this respect, it seemed to differ from hip-pocampal pathology, which was bilaterallysevere in those cases where it was very abnor-mal. It remains possible that at thehistopathological level, such damage was infact asymmetric and mimicked what was hap-pening at the neocortical level, but there wasno firm evidence for this from the postmortemstudy of Hierons et al.3 Neocortical temporallobe damage never occurred in isolation, andwas invariably associated with more medialdamage. Our profile thus differs from thatfound in other types of brain insult, such ashead injury or cerebral infarction, where dam-age may sometimes be restricted to neocorti-cal structures. Anterior and inferior temporallobe gyri suffered damage more often andmore severely than posterior and superiortemporal lobe gyri, which were completelyspared in a few cases. In this respect, the pro-file of temporal lobe cortical and white matterlesions was similar to that found after someforms of cerebral radionecrosis.28A notable finding in our study was the

appreciable damage often found in the sub-stantia innominata (region of the basal fore-brain/anterior perforated substance). At theanatomical level, this finding is not in itselfsurprising, in view of the proximity of thisregion to structures such as the amygdala andthe anterior hippocampus. This area has beenimplicated in conditions such as rupture ofaneurysms of the anterior communicatingartery,29 and it is also adjacent to the nucleusbasalis of Meynert, which itself has beenimplicated in the pathology of Alzheimer'sDisease.30

Magnetic resonance images of small, deepstructures such as the mammillary bodiesmust be interpreted with caution, as slicethickness and angle of cut may sometimesdetermine the quality of the outline shapewhich is obtained. Taking this qualificationinto account, our study found evidence ofdamage to the mammillary bodies and alsoevidence of significant damage to the fornix. Anumber of postmortem studies have providedevidence that sheds light on the integrity ofthe mammillary bodies after medial temporallobe damage. Warrington and Duchen'1reported mammillary body atrophy in their

patient with long standing bilateral medialtemporal lobe lesions. Some authors, how-ever, have found normal mammillary bodiesin amnesic patients with hippocampal pathol-ogy.32-'5 Woods et al36 found demyelination inthe fomix after bilateral hippocampal lesions.They did not specifically comment on themammillary bodies, both of which appearednormal in their coronal section of the brain.The efferent pathways from the hippocampusvia the fornix to the mammillary bodies makedamage to the mammillary bodies highlylikely, but our data suggest that, instead of a"connectionist" disease model, an "anatomi-cal proximity" model might better explain thedistribution of damage in herpes simplexencephalitis. This possibility is reinforced byour finding of cases of "double dissociation"between the presence of mammillary bodydamage and the presence of fornix damage.The proximity of the mammillary bodies tothe anterior hippocampus and amygdala sug-gests that the inflammatory process itselfinvolved structures adjacent to the main dis-ease focus. It is, however, likely-as Hieronset al3 pointed out-that both pathologicalmechanisms operate in herpes simplexencephalitis, especially in respect of the longerterm sequelae of the disease, where some sec-ondary degeneration might be expected tooccur after a number of years. Our own datawould seem to point to the disproportionatedegree of primary rather than secondary dam-age in this part of the brain.Our finding of major mammillary body

involvement casts doubt on the often madedistinction between temporal lobe amnesiaand diencephalic amnesia that has been pro-posed on the basis of comparisons betweenpatients with herpes simplex encephalitis andalcoholic Korsakoff patients.'7 It would nowseem that both sets of patients have mammil-lary body damage, and this fact must there-fore be a constraining factor in anatomicalinterpretations of differences between thememory performance of temporal lobe anddiencephalic amnesic patients.

Thalamic nuclei were affected in around50% of cases, and damage was usually unilat-eral. The lesser degree of involvement of thal-amic nuclei compared with mammillary bodynuclei again points to primary rather than sec-ondary mechanisms underlying such damage,in view of the mammillothalamic connectionsbetween these structures. Frontal lobe dam-age was only present in a few patients, andaffected medial areas more than dorsolateralareas.We found a different profile of lesion

covariance to that shown by Wilson et al I forpatients with head injury. They reported thatlesions in the temporal pole often coexistedwith lesions in the orbitofrontal regions.When we analysed our data in precisely thisfashion, we did not find such a lesion covari-ance profile. This finding highlights the dis-tinctive profiles of these two types of damage,even though they often render similar clinicaland neuropsychological sequelae.

In conclusion, we have documented the

1341

on April 28, 2021 by guest. P

rotected by copyright.http://jnnp.bm

j.com/

J Neurol N

eurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.57.11.1334 on 1 N

ovember 1994. D

ownloaded from

Kapur, Barker, Burrows, Ellison, Brice, Illis, et al

long term neuropsychological and MRI lesionprofiles shown by patients who had hadherpes simplex encephalitis and the extent ofinvolvement of temporal lobe, limbic-dien-cephalic, and frontal lobe structures. Thisstudy must perforce reflect recovery of func-tion in a subset of patients with herpes sim-plex encephalitis. Those who die as a result ofthe infection, or those who make an appar-ently complete clinical recovery, may show adifferent lesion profile and a different neu-ropsychological profile. Studies of thosepatients should help to complete the overallpicture of pathology and recovery of functionthat follows this type of viral infection.

We thank the following for their assistance in various parts ofthe study: Radiography staff of the MRI Unit, King EdwardVII hospital, Midhurst; consultants in the WessexNeurological Centre; Mrs J Hazan, Mr D Moakes, ProfessorA J Parkin, and Mrs D Wearing. Funding was provided fromthe Wessex Neurological Centre Trust. NK acknowledges thesupport of Professor John Pickard and Dr Nicholas Lawton inthe early stages of the project.

1 Warrington EK, Shallice T. Category specific semanticimpairments. Brain 1984;107:829-54.

2 Damasio A, Eslinger P, Damasio H, et al. Multimodalamnesic syndrome following bilateral temporal and basalforebrain damage. Arch Neurol 1985;42:252-9.

3 Hierons R, Janota I, Corsellis JAN. The late effects ofnecrotising encephalitis of the temporal lobes and limbicareas: a clinico-pathological study of ten cases. PsycholMed 1978;8:21-42.

4 Schmidbauer M, Podreka I, Wimberger D, et al. SPECTand MR imaging in herpes simplex encephalitis.JComputAssist Tomogr 1991;15:811-5.

5 Demaerel PH, Wilms G, Robberecht W, et al. MRI of her-pes simplex encephalitis. Neuroradiology 1992;34:490-3.

6 Albertyn LE. Magnetic resonance imaging in herpes sim-plex encephalitis. Australas Radiol 1990;34: 117-21.

7 Cermak LS. The encoding capacity of a patient withamnesia due to encephalitis. Neuropsychologia 1976;14:311-26.

8 Warrington EK, McCarthy R. The fractionation of retro-grade amnesia. Brain Cogn 1988;7:184-200.

9 Pietrini V, Nertempi P, Vaglia A, et al. Recovery fromherpes simplex encephalitis: selective impairment of spe-cific semantic categories with neuroradiological correla-tion. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1988;51:1284-93.

10 Laurent B, Allegri RF, Michel D, et al. Encephalites her-petiques a predominance unilaterale etude neuropsy-chologique au long cours de 9 cas. Rev Neurol (Paris)1990;146:671-81.

11 Wilson JTL, Hadley DM, Wiedmann KD, Teasdale GM.Intercorrelation of lesions detected by magnetic reso-nance imaging after closed head injury. Brain Inj 1992;6:391-9.

12 Lencz T, McCarthy G, Bronen RA, et al. Quantitativemagnetic resonance imaging in temporal lobe epilepsy:relationship to neuropathology and neuropsychologicalfunction. Ann Neurol 1992;31:629-37.

13 Jemigan TL, Ostergaard L. Word priming and recognitionmemory are both affected by mesial temporal lobedamage. Neuropsychol 1993;7:14-26.

14 Kritchevsky M, Squire LR. Permanent global amnesiawith unknown etiology. Neurology 1993;43:326-32.

15 Nelson HE. National adult reading test. Windsor: NFER-Nelson, 1982.

16 Warrington EK. Recognition memory test. Windsor: NFER-Nelson, 1984.

17 McKenna P, Warrington EK. The graded naming test.Windsor: NFER Nelson, 1983.

18 Nelson HE. A modified card sorting test sensitive tofrontal lobe defects. Cortex 1976;12:313-24.

19 Shenton ME, Kikinis R, Jolesz FA, et al. Abnormalities ofthe left temporal lobe and thought disorder in schizo-phrenia. New EnglJ Med 1992;327:604-12.

20 Coffey CE, Wilkinson WE, Weiner RD, et al. Quantitativecerebral anatomy in depression. A controlled magneticresonance imaging study. Arch Gen Psychiat 1993;50:7-16.

21 DeArmond SJ, Fusco MM, Dewey MM. Structure of thehuman brain. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

22 Naidich TP, Daniels DL, Haughton VM, et al. The hip-pocampal formation and related structures of the limbiclobe: Anatomic-magnetic resonance correlation. In:Gouaze A, Salamon S, eds. Brain anatomy and magneticresonance imaging. Berlin: Springer Verlag, 1988.

23 Larcomis D, Khoshbin S, Schick RM. MR Imaging ofparaneoplastic encephalitis. Jf Comput Assist Tomogr1991;14:115-7.

24 Oppenheimer SM, Gelb A, Girvin JP, Hachinski VC.Cardiovascular effects of human insular cortex stimula-tion. Neurology 1992;42:1727-32.

25 Weiller C, Choller F, Friston KF, et al. Functional reor-ganisation of the brain in recovery from striatocapsularinfarction in man. Ann Neurol 1992;31:463-72.

26 Pandya DP, Yeterian EH. Architecture and connections ofcerebral cortex: implications for brain evolution andfunction. In: Scheibel AB, Wechsler AF. eds.Neurobiology of higher cognitive function. New York:Guilford Press, 1990:53-83.

27 Milner B. Hippocampal-neocortical interactions in humanmemory processes. Discussions in Neuroscience1990;6: 101-8.

28 Lee AWM, Cheng LOC, Ng SH, et al. Magnetic reso-nance imaging in the clinical diagnosis of late temporallobe necrosis following radiotherapy for nasopharyngealcarcinoma. Clin Radiol 1990;42:24-31.

29 Irle E, Wowra B, Kunert HJM, et al. Memory disturbancesfollowing anterior communicating artery rupture. AnnNeurol 1992;31:473-80.

30 Van Hoesen GW. The dissection by Alzheimer's disease ofcortical and limbic neural systems relevant to memory.In: McGaugh JL, Weinberger NM, Lynch G. eds. Brainorganization and memory. New York: Oxford UniversityPress, 1990:234-61.

31 Warrington E, Duchen L. A re-appraisal of a case of per-sistent global amnesia following right temporal lobec-tomy: A clinico-pathological study. Neuropsychologia1992;30:437-50.

32 Penfield W, Mathieson G. Memory. Autopsy findings andcomments on the role of the hippocampus in experien-tial recall. Arch Neurol 1974;31:145-54.

33 Duyckaerts C, Derouesne C, Signoret JIL, et al. Bilateraland limited amygdalo-hippocampal lesions causing apure amnesic syndrome. Ann Neurol 1985;18:314-9.

34 Zola Morgan S, Squire L, Amaral D. Human amnesia andthe medial temporal lobe region: enduring memoryimpairment following a bilateral lesion limited to fieldCAI of the hippocampus. JfNeurosci 1986;6:2950-67.

35 Victor M, Agamanolis D. Amnesia due to lesions confinedto the hippocampus: a clinico-pathologic study. Journalof Cognitive Neuroscience 1992;2:246-57.

36 Woods BT, Schoene W, Kneisley L. Are hippocampallesions sufficient to cause lasting amnesia? _J NeurolNeurosurg Psychiatry 1982;45:243-7.

37 Parkin A. Functional significance of etiological factors inhuman amnesia. In: Squire L, Butters N eds.Neuropsychology of memory. 2nd ed. New York: GuilfordPress, 1992:122-9.

1 342

on April 28, 2021 by guest. P

rotected by copyright.http://jnnp.bm

j.com/

J Neurol N

eurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.57.11.1334 on 1 N

ovember 1994. D

ownloaded from

![hma.org.tw · the control group for seropositive participants (1-88%[95% CI 1.54-2.31] in seropositive controls vs 0.38% [0-26—0.54] in seropositive vaccinees), and increased by](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/5f180af091496b79e1655a71/hmaorgtw-the-control-group-for-seropositive-participants-1-8895-ci-154-231.jpg)