Headwaters Winter 2013: Utilities

-

Upload

colorado-foundation-for-water-education -

Category

Documents

-

view

224 -

download

5

description

Transcript of Headwaters Winter 2013: Utilities

H e a d w a t e r s | W i n t e r 2 0 1 3 1

Colorado Foundation For Water eduCation | Winter 2013

Turningon The

Tap

Why We Pay More For Water TodayWater Infrastructure That Demands Attention

Protecting Human Health and the Environment Through Water TreatmentA Step-By-Step Bathroom Makeover That Makes WaterSense

Opportunity + Conservation = Water

C o l o r a d o F o u n d a t i o n f o r W a t e r E d u c a t i o n | y o u r w a t e r c o l o r a d o . o r g

Strengthening Leadership

Apply Now for the 2013 Water Leaders Program Are you a mid-career professional that desires to have a long-term impact on Colorado water issues? Do you wish for a network of similarly minded peers? Do you want to further develop the leadership skills you possess, while focusing on those most important for a career in water?

If so, the CFWE Water Leaders Program may be for you! Through this program, you will gain understanding of leadership challenges in Colorado water, ex-

plore how your personal strengths equip you to face those challenges, and create a long-lasting group of friends and colleagues. A survey of employers who sent staff members through the program found marked growth in their employees’ confidence and self-awareness, their ability to self-reflect, and their leadership skills. Employers noted that they also benefited from the knowledge the participants’ gained and the new relationships they built during the program.

Applications to take part in this unique experience are now available at yourwatercolorado.org. They are due February 15, 2013.

CFWE Mission in MotionGrowing Capacity

CFWE Extends its Gratitude December is always a hustle and bustle, and we all struggle to find time to fit everything in. With that said, we are extremely pleased that so many supporters found time during the holiday season to show financial appreciation for CFWE as we wrapped up a successful end-of-the-year giving campaign.

More than 98 supporters demonstrated their passion for balanced and accurate water education by donating over $11,000. These donations mean a great deal to us—they allow us to continue delivering the outstanding educational programs you all know and love us for.

Thank you once again from the team here at CFWE!

Graduates of the 2012 Water Leaders course learned how to more effectively problem-solve and navigate conflict and diversity.

In Recognition of Leaders in Water Education

The Colorado Foundation for Water Education is proud to announce the recipient of our 2013 President’s Award, Jim Isgar. A state director for the U.S. Department of Agriculture Rural Devel-opment, Jim was an integral member of CFWE’s creation 11 years ago as a former state senator. The award pays tribute to those who demonstrate steadfast commitment to water resources educa-tion. Join us in thanking Jim for his advancement of a greater understanding of water in Colorado.

We will also bestow our Emerging Leader Award to Amy Beatie. Amy has been the execu-tive director for the Colorado Water Trust for more than five years and is a graduate of CFWE’s Water Leaders Program. Congratulations, Amy!

A ceremony will be held to celebrate their work in April 2013 in downtown Denver. Tickets will be available at yourwatercolorado.org in early March. We hope to see you there!

Cultivating Participation

Speakers Increase Water Fluency Last year, the Colorado Water 2012 Speakers Bu-reau reached more than 2,800 community leaders and civic group members, helping them speak flu-ent water. CFWE couldn’t let all that momentum pass us by. Rather than ending the Speakers Bu-reau program with the close of 2012, CFWE ad-opted the program and will continue to engage volunteer speakers to increase water awareness across the state.

Welcome the new and improved CFWE Speak-ers Bureau! This year, we’re working with a diverse group of talented speakers who will reach out to civic groups and talk about drought and the value of water in Colorado. CFWE kicks off the new pro-gram with an updated presentation and handouts for speakers and educators to use—we’ll double our reach, speaking to more community leaders than ever before. Find a water speaker near you at yourwatercolorado.org.

Keep the Feedback Coming We asked. You answered. To improve our educa-tional offerings and capacity to provide relevant programs to our members, CFWE conducted our second annual survey of members and top CFWE supporters in December 2012.

Respondents relayed how they use both our Citizen’s Guides and Headwaters magazine, and let us know how accurate and balanced they feel these publications are. Ninety-eight percent of respondents said that Headwaters was “very or

moderately helpful” in helping them understand current Colorado water issues, and 94 percent of members use it as a reference. What topics would supporters like to see us cover? Top re-sponses were drought, supply and demand, and population growth on the East Slope.

This input will help staff set goals to reflect our members’ educational needs and preferences, and ensure that our work remains relevant and useful. Thanks to all participants!

H e a d w a t e r s | W i n t e r 2 0 1 3 1

Defining Values

On Tour With CFWE CFWE is gearing up to offer a water tour near you! These interactive programs help participants to define and understand the many values and uses associated with water in Colorado.

Join us in exploring the value of water in your life at any of these upcoming CFWE tours. Sign up to be notified as registration becomes available for specific tours at yourwatercolorado.org.

• March 8, 2013—Learn how climate science and water resources are connected at the National Ice Core Laboratory in Lakewood.

• May 2 and May 16, 2013—Explore how urban waterways are managed, restored and protected on an Urban Waters Bike Tour in Denver.

• May 30-31, 2013—Get a taste of Grand Valley water, agriculture and energy issues on the Lower Colorado River Basin Tour.

• June 20-21, 2013—Gain understanding of the relationship between river health and transbasin diversions on the Upper Colorado River Basin Tour.

• July 17-19, 2013—Broaden your perspective on interstate water issues on the Platte River Tour in Colorado, Wyoming and Nebraska.

Increasing Awareness

Headwaters Stories Step Off the Page As the Colorado Foundation for Water Educa-tion’s cornerstone publication, Headwaters reach-es thousands of Coloradans each year through engaging and balanced storytelling. Numerous individuals and groups find it an effective educa-tional tool to both increase awareness of water as a scarce resource and examine water-related values and uses.

CFWE is now taking Headwaters on the road! A panel discussion at the 2013 Colorado Wa-ter Congress Annual Convention will reveal the production process from conception to delivery. Journalists, sources and reviewers from the Win-ter 2013 utilities-focused issue and the Fall 2012 agriculture-focused issue will give a behind-the-scenes look at their respective articles. Conven-tion attendees will hear how farming practices are evolving in the face of shrinking water supplies and get an inside look at the nuts and bolts of transporting water to and from the tap.

Look for future Headwaters events as CFWE brings the faces, voices and stories from the magazine’s pages to life.

CFWE staff (left) gear up for the Nestle Waters tour stop.

Creating Knowledge

Hot Topics in Colorado Water Get ready to learn about the hottest topics in water! CFWE is creating one-page Water 101 fact sheets covering drought, wildfire and other on-demand subjects. These fact sheets can be downloaded from CFWE’s website for your reference or distri-bution. They’re ideal for public speaking engage-ments, classroom presentations, or as a quick guide to get an overview on a popular water topic. Check out existing fact sheets, and come back for many more this year at yourwatercolorado.org.

To manufacture 1 liter of your favorite bottled beverage takes about 2.26 liters of water if you prefer Coca-Cola, 1.37 liters if you’d rather

hydrate with Nestle Water, and 4.07 liters if your drink of choice is a Coors beer.

H e a d w a t e r s | F a l l 2 0 1 2

1

Colorado Foundation For Water eduCation | Fall 2012

Quality + Scarcity + Opportunity = Water

Keeping Water on Colorado’s FarmsCoping With Drought and a Competitive Water MarketAgricultural Water Rights 101

Tasting the Fruits of the North Fork Valley’s Labor

Grown in Colorado For the Rocky Mountain state,

agriculture means

quality food,

open space and

a boon to the economic engine

H e a d w a t e r s | F a l l 2 0 1 2

1 3

By Caitlin Coleman

iSto

ck.c

om (3

)

CFWE tour participants (above) got an inside look at the Miller-Coors water treatment facility in December 2012.

Executive Director

2 C o l o r a d o F o u n d a t i o n f o r W a t e r E d u c a t i o n | y o u r w a t e r c o l o r a d o . o r g

Nicole Seltzer, CFWE Executive Director

How much of one’s life should a job constitute?

Depending on your point of view, it could be something that occupies your time from 9 to 5

and pays the bills, or something that defines you and gives you much more than a paycheck.

I don’t believe there is one universally right answer—we each have our own work-life bal-

ance that (hopefully) suits our lives. I will qualify the next statement, as I do not have much

professional experience outside the field of natural resources management, but it seems to

me there is a noticeably large portion of those who work in and around water whose jobs are

a meaningful part of their lives.

Surely the responsibility to provide clean, adequate water to Colorado communities is one to take seriously—and even honor. Our water and wastewater infrastructure keeps disease rates low, our rivers free from pollution, and the economic engine turning. I am proud to work alongside so many who display obvious passion for their work. Some of those people are interviewed and profiled in this issue; their stories and perspectives resonate.

Much of the work of water happens behind security gates, and this rare glimpse inside water utilities’ day-to-day probably doesn’t do justice to the importance or sheer impressive-ness of what they accomplish. I will go so far as to say that your local water treatment plant operator is an unsung hero.

As the Colorado Foundation for Water Education wraps up Water 2012, I am thankful for many other unsung heroes—all those who volunteered their time, resources and money to make Colorado’s Year of Water such a success. Partners, new and old, stepped up their water education contributions. More than 600 volunteers made a priority of communicating water’s importance. Those like the Colorado Water Conservation Board, Encana and Xcel Energy gave meaningful sums of money to make it happen. Others such as Continuing Legal Education of the Colorado Bar Association and Colorado Humanities gave organizational resources that helped exceed the goal of reaching 500,000 Coloradans with a message of water’s value.

With so much more left to do, it’s easy to just move on to the next project. But I would be remiss if, at the start of a new year, I did not stop and express my gratitude to everyone who helped CFWE thrive in 2012. Our annual report is available online. The list of donors and volunteers grows each year. I hope you will take a second to view the names of those who helped Colorado “speak fluent water” in 2012, and if your name isn’t on there yet, we can surely find a home for your talents!

Wishing you a peaceful, prosperous and enjoyable 2013,

ContentsWinter 2013

H e a d w a t e r s | W i n t e r 2 0 1 3 3

Turningon The

Tap

13 The Rising Cost of Bringing Water to a Faucet Near YouBy Caitlin ColemanWater rates have gone up dramatically over the past 20 years, and customers want to know why. Utilities aren’t out to turn a profit; they’re just trying to keep up with their own rising costs—for everything but the kitchen sink.

18 Beyond the TapBy Jerd SmithA labyrinth of water infrastructure lies beneath our city streets. And it’s getting old. Just what does it do for us, and how much attention—and funding—will its maintenance and replacement require?

23 The Art and Science of Pricing WaterBy Chris WoodkaSome utilities get tax dollars, others don’t. Some charge higher tap fees for new development, while others have higher rates. Ultimately, every utility must bill customers for their water use in order to cover costs, but each does so differently. A look at the not-so-simple process of setting rates, and why we aren’t all paying the same.

28 Water Quality’s Front LineBy Dan GordonWater moves into and out of our homes daily, coming in clean and going out dirty. On either end, someone is treating that water to keep it varying degrees of clean. Regulations stipulate the contaminants that must be filtered out, whether the water is destined for our bodies, our lawns or our rivers. It’s a protective barrier that wasn’t always in place.

Water is…8 A SourceWhy wildfires disrupt water supplies and have water utilities working in the forest, too; When it comes to source water protection, prevention is best; Opportunities to lend a hand protecting local water sources.

9 ConservationHow utilities maximize efficient water use; Watering restrictions and conservation messages help stretch scarce water supplies; Outdoor water use trivia.

10 SnowMountain snowpack serves as a natural reservoir, but that reservoir is at risk; Snowmaking can make up for some lack of natural snowfall, but has its limitations; An Arizona ski resort becomes the first to make snow with treated wastewater.

12 OpportunityWhy water and wastewater utilities are gearing up now to fill job vacancies; Cheat sheet for entering the water utility workforce; Water utility recruiters are going green.

36 DIY: Have a WaterSense WeekendWater conservation is a great excuse for a bathroom makeover. Plan a weekend to change out three bathroom fixtures for their water-saving counterparts, and watch the savings, both in water and energy costs, roll in. By Frank Kinder

On the Cover: Steve Ryken of Ute Water Conservancy District in the Grand Valley.

Mat

thew

Sta

ver

Kev

in M

olon

ey

Steve Hellman climbs out of the mechanical room at Aurora’s Charles A. Wemlinger water treatment plant.

Colorado Foundation for Water Education1580 Logan St., Suite 410 • Denver, CO 80203303-377-4433 • www.yourwatercolorado.org

Board MembersGregg Ten Eyck

President

Justice Gregory J. Hobbs, Jr.Vice President

Rita CrumptonPast President

Eric HecoxSecretary

Alan MatloszTreasurer

Becky BrooksNick Colglazier

Lisa DarlingSteve Fearn

Rep. Randy FischerJennifer GimbelGreg JohnsonPete KasperDan Luecke

Trina McGuire-CollierKaylee MooreReed Morris

Sen. Gail Schwartz Travis SmithAndrew ToddChris Treese

Reagan Waskom

StaffNicole Seltzer

Executive Director

Kristin MahargProgram Manager

Caitlin ColemanProgram Associate

Jennie GeurtsAdministrative Assistant

Adam HicksDevelopment Officer

Mission statEMEnt The mission of the Colorado Foundation for Water Education is to promote better understanding of water resources through education and information. The Foundation does not take an advocacy position on any water issue.

acknowledgments The Colorado Foundation for Water Education thanks the people and organizations who provided review, comment and assistance in the development of this issue.

Headwaters Magazine is published three times a year by the Colorado Foundation for Water Education. Headwaters is designed to provide Colorado citizens with balanced and accurate information on a variety of subjects related to water resources. Copyright 2013 by the Colorado Foundation for Water Education. ISSN: 1546-0584 Edited by Jayla Poppleton. Designed by Emmett Jordan.

ContributorsCaitlin Coleman is a writer and program associate with the Colorado Foundation for Water Education. Originally from New York state, where she grew up with a septic tank and well, reporting her story for this issue (“The Rising Cost of Bringing Water to a Faucet Near You,” page 13) gave her a new appreciation for utilities. “I’ve worked on water quality issues caused by limited wastewater treatment in impoverished areas, but that’s an extreme,” Caitlin says. “Talking with water utility managers about their role in securing the health and safety of a community, allowing cities and towns to prosper—it’s no different, but their service is something we all value.”

Jerd Smith is a Colorado-based writer and editor with a special interest in water and conservation issues. Reporting on water infrastructure for this issue (“Beyond the Tap,” page 18), Jerd says: “Let’s face it, there’s nothing very glamorous about a buried water pipe, and for decades they’ve been largely ignored by the general population. But deep within the bowels of water delivery systems, fascinating things are starting to occur that will help local water providers deliver water in ways that are less expensive and more efficient than we’ve ever seen.”

An editor and reporter for the Pueblo Chieftan, Chris Woodka makes a guest appearance writing for Headwaters this issue. He has reported on water issues for the Chieftain since 1985, specializing in large-scale water projects throughout Colorado. For 12 years, Chris was the president of a small ditch company west of Pueblo that mainly served hobby gardens. Today, he just farms bluegrass, relying on the Pueblo Board of Water Works for his water supply. In preparing his story on water-rate setting for this issue (“The Art and Science of Pricing Water,” page 23), he became so bogged down in numbers that he nearly forgot to shut down his sprinkler system for the winter months.

First-time Headwaters contributor Dan Gordon returned to Colorado after growing tired of being buffeted by hurricanes in south Florida. He and his wife now live in La Junta, near where he grew up at Fort Lyon. “As a kid, I didn’t think much about water or the lack of it in this part of the world,” says Dan. Since returning, he has a new interest in how Coloradans share their water and how they built systems to deliver it for urban and agri-cultural uses. For this issue, he dove into the subject of water treatment (“Water Quality’s Front Line,” page 28). A 30-year veteran of newspapers, he has worked for the Rocky Mountain News in Denver and the Sun-Sentinel in Fort Lauderdale.

Barton Glasser is a commercial and editorial photographer based in western Colo-rado. In photographing water-based stories, Barton is repeatedly astonished by the engineering feats, vast infrastructure and great cooperation that are involved. He is grateful for the people that help make it possible for us to have the water we need to live, work and play in the West. His photography appears throughout this issue (“Beyond the Tap,” page 18, and “Water Quality’s Front Line,” page 28).

Photographer Kevin Moloney, based in Denver, jokes that he drives for a living and takes pictures on the side, given the vast stretches of road between assignments around the Rocky Mountain West. Photo shoots for this issue (“Beyond the Tap,” page 18, and “The Art and Science of Pricing Water,” page 23) kept him closer to home in Erie and Aurora, where he couldn’t help but notice how quiet and lonely automated water plants feel these days. Kevin’s work has regularly appeared in Headwaters, as well as the New York Times, publications of the National Geographic Society, and many other publications.

Matthew Staver is an editorial and documentary photographer based in Denver. “Cre-ating visual permanence in a world of relentless motion” is more than a tagline for Matthew; it is an ongoing mission that he strives to achieve during every commis-sion. His assignment for this issue (“The Rising Cost of Bringing Water to a Faucet Near You,” page 13, and “Water Quality’s Front Line,” page 28) took him to Vail and the Eagle River Valley. He hopes his photographs reveal water utilities’ connection to the environment in a way that helps foster a better understanding of this often underappreciated and evolving subject.

iSto

ck.c

om

4 C

On a bright sunny morning in December, I

donned my hardhat obediently and followed my hosts toward the sound of rushing water.

It had been nearly 16 years since I visited a wastewater treatment plant in college, and I

couldn’t remember being quite so excited then. But now, I was nearly giddy as I caught my

first glimpse of the grayish water tumbling around a sharp corner. Peering gingerly over the cement wall, I wondered if the wastewater below could be

coming from my own neighborhood in northeast Denver. Could this be the very water we had used hours earlier that day in our showers and sinks—and our toilets? Moving at high speed, it all blended into one big, murky river, and I was spared from imagining I might be seeing my next-door neighbor’s you-know-what.

Barbara Biggs, governmental affairs officer, and Marty Tiffany, plant operator, were gra-ciously giving me a personal tour of the Robert W. Hite Treatment Facility of the Metro Wastewater Reclamation District in north Denver, where nearly 2 million people’s waste-water is continuously processed. As we crossed a bridge over the west-bound interceptor canal to view several coming in from the opposite side of the city, I was impressed to note labels denoting sources as distant as “Golden.” At that moment, the dirty water was coming in at a rate of 150 million gallons per day for treatment.

Nearly two hours later, after trekking around the enormous plant and receiving patient answers to my many questions, I had a pretty good handle on exactly what Marty, Barbara and their colleagues accomplish for the community. As we watched the treated effluent pour into the South Platte River, it was comforting to know the water had been meticulously treated and tested to meet the many state and federal water quality standards in place for our protection. The whole process was pretty incredible, and I highly recommend taking a similar tour if you ever have the opportunity.

Despite the extent of our daily reliance on water, not to mention our dependence on its arrival and departure from our homes, many of us remain largely ignorant of what goes into moving, storing, treating and delivering it. We know we have to pay our bills or our water service could be shut off, but we don’t really know exactly what we’re paying for. What do water utilities really do? How do they keep up with the nonstop, and often growing, daily water demand of their communities? And what role do they play in protecting both public health and the environment?

In this issue, we invite you to explore these questions and more as we delve into the realm of water and wastewater utilities. Next time you turn on your tap and clean water comes out, you’ll have a better idea of what—and who—made that small miracle possible.

Jayla Poppleton

TenT h i n g s To D o

I n T h i s I s s u e :

1 Apply for CFWE’s 2013 Water Leaders Program (inside front cover).

2 Attend Headwaters’ first live discussion, where its stories will step off the page (page 1).

3 Lend a hand to protect the source of your drinking water (page 8).

4 Check out what Americans nationwide have to say about water infrastructure (page 16).

5 Visit your water utility’s website for a water quality report and tips on in-home water infrastructure maintenance (page 22).

6 Compare water rate structures for a handful of Colorado utilities (page 25).

7 Learn how to decipher your water bill (page 26).

8 Follow your flush through the wastewater treatment process (page 32).

9 Find out which ingredients in your personal care products aren’t removed by wastewater treatment (page 33).

10 Swap your old bathroom fixtures for their water-saving counterparts (page 36).

H e a d w a t e r s | W i n t e r 2 0 1 3 5

Editor

Jayla Poppleton, Editor

6 C o l o r a d o F o u n d a t i o n f o r W a t e r E d u c a t i o n | y o u r w a t e r c o l o r a d o . o r g

Headwaters Photo Contest See your photo in the next issue of Headwaters magazine! The Colorado Foundation for Water Education is now accepting entries of profes-sional and amateur photographs that tie in with the topical focus of upcoming issues. The winning photo will appear on this two-page format, while other photos may be used throughout the magazine. Find contest rules and details on future topics at www.yourwatercolorado.org.

Walking On WaterWinning photo submission by Steve VanderleestStaff from the Glenwood Springs Water and Wastewater Department traverse along

an 800-foot pipeline that brings raw water bound for Glenwood from Grizzly Creek.

The pipeline, accessible by foot trail, was 90 years old when it was replaced in 2002.

Materials had to be delivered by helicopter.

H e a d w a t e r s | W i n t e r 2 0 1 3 7

A Source > Conservation > Snow > Opportunity

Water is Colorado

Water is A Source

8 C o l o r a d o F o u n d a t i o n f o r W a t e r E d u c a t i o n | y o u r w a t e r c o l o r a d o . o r g

Protecting Water From Fire In 2012, wildfires blazed across Colorado landscapes, incinerating thousands of forested acres and leaving barren slopes and loose soils. The same was true during the drought of 2002, when water utilities saw fires wreaking havoc on their water sources. Water providers have since invested more heavily in restoring and protecting their watersheds from fire.

“We learned that water infrastructure is more than pipes and dams,” says Travis Thompson, me-dia coordinator for Denver Water. “For Denver Water, our ‘infrastructure’ encompasses more than 2.5 million acres of land in 13 counties. Our investment in these watersheds is a long-term commit-ment to keeping them healthy decades from now.”

Deep in a healthy forest, a web of strong root systems holds soils in place, sustains vegetation and naturally filters water. Intense fire destroys that network, leaving ash, sediment and burnt debris with no anchor. Storms that follow bring those sediments rushing in torrents down mountainsides—and into streams and water supplies.

Even a small rain can trigger large ash flows after a fire, says Eric Reckentine, deputy director of water resources for Greeley Water. Last summer, northern Colorado’s Poudre River ran black with ash from the High Park Fire, while the Clifton Water District to the west of the Continental Divide saw a muddied Colorado River full of burnt pine needles, ash and other debris after the Pine Ridge Fire.

In June 2012, Greeley and Fort Collins stopped drawing water from the Poudre because of ash. In normal years, flows from the Poudre supply about 25 percent of Greeley’s water.

To prevent ongoing damage to water quality, utilities like Greeley must stabilize burn-area soils and promote new plant growth—yet they don’t always own the land surrounding their water sup-plies. Instead, they partner with organizations like the U.S. Forest Service, the Natural Resources Conservation Service, volunteer groups and private landowners to restore forest health by mulch-ing and seeding, planting trees and shrubs, installing erosion control bars and sediment traps, and thinning trees prone to future wildfires.

This work doesn’t come free. Greeley Water expects to share a $9.9 million investment in High Park Fire remediation with the cities of Loveland and Fort Collins as well as three nearby districts collectively referred to as the Tri-Districts, with partial reimbursement from the Natural Resources Conservation Service.

Denver Water plans to spend $16.5 million on forest treatment projects over a five-year period. The U.S. Forest Service will match the utility’s investment, enabling them to target more than 38,000 acres in priority watersheds. —Caitlin Coleman

Going to the Source Communities take pride in the quality of their drinking water—or they worry about it. Either way, protecting the source of the water supply can be both personal and a matter of public health.

Source water protection work is in progress across Colorado, but looks different depending on the locale. Activities range from addressing nonpoint sources of pollution such as farm fertilizer runoff or contamination from roads, to reducing access to reservoirs or promoting forest health.

Grand Junction developed a watershed protection ordinance in 2007 after Genesis Gas and Oil acquired leases to drill within the Plateau Creek watershed on the Grand Mesa, a source of the city’s water. Residents were concerned about the potential impacts of drilling—particularly hydraulic fracturing—on their drinking water supply. To deal with these concerns, stakeholders including the cities of Grand Junction and Palisade, Genesis, federal land managers and local citizens came together, agreeing to a set of best management practices once drilling began. Genesis has avoided developing its leases within the watershed so far. In the meantime, Grand Junction is funding a water monitoring study to establish a baseline for the

quality of its water. Monitoring is something Colleen Williams, source water protection spe-

cialist for the Colorado Rural Water Association, frequently recommends to the water utilities she works with. By establishing a baseline for water quality, communities can track what is showing up in their water over time and watch for red flags. “It’s really important to have some way that they would know that there is a problem in that water source,” says Williams.

Some communities face concerns about oil and gas drilling, others with abandoned mine drainage or septic tank maintenance. Then there’s fire and drought—two of the biggest concerns, Williams says. Fortunately, much of Colorado doesn’t have contaminated water, she adds. A lot of the focus is on prevention—keeping water clean in the first place is far more cost-effective.

Williams also recommends public outreach and information sharing: “We want the community to encourage everyone to become a stakeholder, to become a steward of that drinking water source.”

—Caitlin Coleman

Lend a Hand to Protect Source Water Get involved in protecting your drinking water with volunteer opportunities around the state:

>> High Park Restoration Coalition: High Park and Hewlett Gulch fire restoration work is underway near Fort Collins through a coalition of organizations that includes Wildlands Restoration Volunteers; Trees, Water and People; and Rocky Mountain Fly Casters. Expect to help seed native grasses, plant native trees and shrubs, install erosion control structures and apply mulches, primarily on private lands. Visit www.wlrv.org.

>> Coalition for the Upper South Platte: CUSP teaches communities how to live with and survive fire in the 2,600 square-mile Upper South Platte watershed that stretches southwest from Denver nearly to Buena Vista. CUSP’s most immediate work is with the Waldo Canyon Fire. Volunteer to help with sandbagging, erosion control, revegetation and chipping wood for fire prevention. Go to www.uppersouthplatte.org.

>> Volunteers for Outdoor Colorado: Volunteers for Outdoor Colorado is also working on High Park Fire and Waldo Canyon Fire projects, among others. See www.voc.org.

>> Local Watershed Group: The Colorado Watershed Assembly supports the efforts of grassroots, nonprofit groups working to protect watersheds. Find out if a group near you is involved with source water protection work at www.coloradowater.org.

—Caitlin Coleman

Aerial mulching is used to stablize soil in the Monument Gulch area in Larimer County after the High Park Fire.

US

DA

For

est S

ervi

ce

H e a d w a t e r s | W i n t e r 2 0 1 3 9

Water is Conservation

Waste Not, Want Not She’s got her headphones on—must be listening to some chart-topping song. No, in fact, water utility employees routinely conduct leak surveys, listening with headphones or setting up equipment to sound for leaks, then repairing broken pipes. Such actions can save millions of gallons each year of a limited—and increasingly expensive—resource.

All utilities unavoidably lose some water through leaks, broken meters, water main breaks and more. As utilities detect and fix leaks, they prevent larger breaks and cut costs.

“If you’re buying more water than you need, that’s not very efficient at all,” says Roby Forsyth, distribution and collection manager for the Eagle River Water and Sanitation District. The district completes a leak survey of its entire distribution system at least twice each year, sounding through sections of water main that need more analysis. Leaks, large to small, can sound like water rumbling through rapids in a river or like the spraying noise you hear if you put your finger over a faucet.

By reducing water loss, utilities can bill for more of the water that’s run-ning through their systems. They also save energy and treatment costs by not pumping as much soon-to-be-lost water partway through the system.

Improving efficiency is just one way utilities maximize their water sup-plies. They also run conservation programs to raise public awareness about water use, encourage water savings and reuse water. As water reaches customers, many utilities encourage wise water use through tiered rate structures, rebates on low water-use devices, public education cam-paigns, xeriscape demonstration gardens, water use audits and more.

For water providers that deliver 2,000 acre feet or more each year (2,000 acre feet typically meets the needs of about 5,000 households), such actions were stipulated by the state legislature in 2004 in the form of water conservation plans. These providers must develop and imple-ment, then periodically evaluate and revise, a water conservation plan or they become ineligible for financial assistance from the Colorado Water Conservation Board or Colorado Water Resources and Power Develop-ment Authority.

The conservation plans are meant to further promote a range of sustain-able practices that water utilities across the state, many of which have reduced demand by 20 percent over the past decade, may already employ. —Caitlin Coleman

Watering Restrictions: Conservation Measure or Drought Response? Water monitors in Castle Rock pass their sum-mer cruising around town, enforcing mandatory watering restrictions during the peak water use months of June, July and August. From their ve-hicles, they scan for wasteful watering or water-ing at the wrong time or on the wrong day, and educate customers. The “water cops” of Castle Rock didn’t just come out for the 2012 drought; the town has implemented this aspect of its con-servation program every summer since 1985.

Castle Rock is not the only water provider that includes watering restrictions in its regular conservation plan. Denver Water and the cities of Brighton, Thornton and Greeley are among many who implement such restrictions—often limiting watering days and times—regardless of drought conditions. Denver Water, for example, asks that from May 1 through October 1 cus-tomers water between 6 p.m and 10 a.m., refrain from watering during rain or wind storms, avoid

watering sidewalks and streets, and only water three days a week. The restrictions are enforced by “Water Savers,” who hand out warnings for first-time offenders. After that, fines start at $50; multiple offenders could have their water service shut off. Similarly, the city of Thornton has a wa-ter waste code; however, Thornton only hires patrols when responding to drought.

Utility water conservation and drought miti-gation efforts are often completely separate programs, but they can piggyback off each other. Many Colorado cities implement water conservation plans year-round through market-ing, rebates, customer education and watering restrictions—but during drought, those mes-sages intensify.

“The efforts that we’re making now in educat-ing and communicating to our consumers about water conservation is what is getting us through the 2012 drought,” says Joseph Burtard, public

relations officer for the Ute Water Conservancy District and chairman of the Drought Response Information Project (DRIP).

DRIP is a product of the 2002 drought, when the four water providers in the Grand Valley—Ute Water, the city of Grand Junction, the town of Palisade and Clifton Water District—came to-gether to create a drought plan. Through DRIP, the utilities promote conservation year-round through outreach channels such as radio and television ads targeting residential and commer-cial water use. When the 2012 drought struck, DRIP was able to quickly reach out to custom-ers, asking them to implement voluntary water-ing restrictions.

“Conservation awareness and behavior helps prepare communities for drought conditions,” Burtard says. “I think everybody saw that this year across the state.”

—Caitlin Coleman

Did You Know?

55 Percent of residential water in Front Range urban areas is used outdoors, primarily to water turf, making lawn watering the largest demand on municipal water supplies.

3 Gallons of water are required to sustain each square foot of buffalograss for a season. The more commonly seen Kentucky bluegrass needs 18 to 20.

9:00 is the time of day that bookends efficient lawn watering hours. Watering after 9 p.m. and before 9 a.m. helps reduce evaporation losses due to hot and windy weather.

50 Percent of flower bed irrigation needs can be cut by using mulch, which reduces evaporation from the soil surface.

Source: CSU ExtensionDenver Water’s “Use Only What You Need” messaging is highly visible around the metro area.

Cou

rtes

y D

enve

r W

ater

1 0 C o l o r a d o F o u n d a t i o n f o r W a t e r E d u c a t i o n | y o u r w a t e r c o l o r a d o . o r g

Water is Snow

Bring on the Snow Liquid assets is a term used by money manag-ers, but should it not also apply to the recreation industry? For resort communities and the snow sports industry across Colorado, water that falls as snow is a tremendous asset; the entire state depends on the income it generates. But what happens when there isn’t enough?

“Snow trumps all,” says Greg Ralph, marketing director at Monarch Mountain. “Snow is why they come here.” Low snowpack, as experienced dur-ing the 2011 to 2012 winter, draws fewer skiers to the slopes. In some cases snowmaking can make up for that loss, but to a limited extent.

Last year, Monarch received only 195 inches of snow, just more than half its average 350 inches. This, along with Monarch’s no-snowmaking poli-cy, caused a 19 percent decrease in skier visits. “It was devastating,” Ralph says.

Collectively, the 22 Colorado Ski Country USA resorts, which include Monarch and most other major ski resorts except for those owned by Vail Resorts, weren’t hit quite as hard, seeing an 11.9 percent decrease in skier visits compared to the five-year average. Colorado Ski Country USA

also attributes this decline to the dry and warm 2011 to 2012 winter—West Slope precipitation was 43 percent below average.

Aspen Snowmass faced only a 1.8 percent de-cline in skier visits last year. But Aspen has a strong international clientele, people who book their trips months in advance. The resort isn’t heavily reliant on Front Range traffic, says Jeff Hanle, director of public relations at Aspen Snowmass. That doesn’t change the fact that Aspen received only half its average annual snowfall. Aspen Snowmass used its early-season snowmaking, though limited, to cover high traffic areas where natural snowfall wouldn’t have been sufficient, says Hanle.

Resort managers might make more snow if they could, but snowmaking has its limitations. Most resorts divert directly from streams during winter months, when rivers run low. If their water rights are behind other users in line, or the stream is be-low stipulated flow levels, they may have to shut off their blowers. Snowmaking is also limited by temperature—if it’s not cold, there won’t be snow. Other limiting factors can include high operating costs and community water and energy needs.

Historically, Aspen Snowmass starts making snow November 1 and stops before Christmas each year—the resort is limited by its water right decree from pulling water from Snowmass Creek after December. In the future, they may have more flexibility. In July 2012, Aspen Skiing Company purchased rights to a portion of the water stored in Zeigler Reservoir, located on the mountain. The $3.25 million agreement with Snowmass Water and Sanitation District will prevent low flows from being further depleted by snowmaking withdraw-als in Snowmass Creek and allow for later-season snowmaking. The resort will also save on energy costs previously used to pump water uphill from the creek. “For environmental reasons, for ef-ficiency reasons, for making-snow-at-optimum-time reasons, this was a huge deal for us…a win-win-win-win grand slam,” says Hanle.

Still, although snowmaking technology has im-proved, it’s not the same as skiing fresh powder, Monarch’s Ralph contends. “Most of the time na-ture takes care of us pretty well. Skiing on all-nat-ural snow—it’s one of our marketing attributes.”

—Caitlin Coleman

Recycling Hits the Slopes:

Where does your snow come from?This winter the Arizona Snowbowl resort just north of Flagstaff became the first in the world to

make snow entirely from reclaimed, treated wastewater effluent.

The plan has been a long time coming. In February 2012, a federal appeals court put an end

to a 10-year legal battle brought by a coalition of environmental groups and 13 American Indian

tribes by ruling in favor of Arizona Snowbowl. The decision will allow the use of treated waste-

water effluent from the nearby city of Flagstaff to powder the resort’s slopes. Opponents cite the

desecration of sacred land, health concerns and ecological impacts of chemicals that may remain

in the effluent-based snow.

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, reclaimed water is already being used for

snowmaking in Maine, Pennsylvania and California, as well as in Canada and Australia—but none

of these resorts use effluent alone. Although the use of reclaimed wastewater effluent to make snow

hasn’t yet been tried in Colorado, it is used for other purposes, such as watering city parks.

Until the recent decision, Arizona Snowbowl was short a water supply to use for snowmaking.

Now, after spending approximately $12 million on legal fees and infrastructure to move the re-

claimed wastewater uphill from Flagstaff, its snow machines are running.

Many Colorado ski areas also face challenges in securing sufficient water supplies for snow-

making, and a few reclaim water in their own way to compensate for slim streamflows in winter

months. Loveland Ski Area recaptures up to 70 percent of its manufactured snowmelt, storing it in

an off-site reservoir and releasing it to make up for river diversions the following year. The practice,

called a substitute water supply plan, doesn’t go so far as to cut river diversions for snowmaking at

the point of diversion, but it does allow the ski area, with its relatively junior priority water rights, to

keep making snow when it otherwise legally couldn’t take water from the stream. —Caitlin Coleman

Reclaimed wastewater, also called treated effluent, must meet water quality standards to protect all applicable uses of the receiving water body. Regulation 84 of the Colorado Water Quality Control Division is in place to further protect public health if reclaimed wastewater is to be reused for nonpotable uses such as landscaping.

iSto

ck.c

om

H e a d w a t e r s | W i n t e r 2 0 1 3 1 1

Water is Snow

Nature’s Reservoir at Risk “Colorado’s mountain snowpacks are the first and foremost reservoir for Colorado water supplies,” says Chris Landry, executive director for the Silver-ton-based Center for Snow and Avalanche Studies. Most of Colorado’s water supplies are first banked as snowpack before they flow into constructed reservoirs. That natural snow bank is beginning to face pressures, creating challenges for Colorado’s people, environment and water managers.

Between 60 percent and 90 percent of the water used in the western United States is mountain run-off, says Mark Williams, a researcher at the Institute of Alpine and Arctic Research at the University of Colorado. At Williams’ research station on Niwot Ridge, 20 miles west of Boulder, 87 percent of an-nual precipitation falls as snow.

“If we had rain instead of snow during the winter, it would just run off and leave our system,” explains Williams. Instead, snowpack accumulates and re-mains frozen in the mountains all winter, melting throughout the spring and summer and feeding riv-ers. By the end of June, only half the snow at Niwot Ridge is gone, with plenty remaining to melt in July and August, when summer temperatures heighten irrigation demands for lawns and crops. “That water is released from the snowpack when we need it the most,” Williams says.

According to a 2012 U.S. Geological Survey study based in part on Williams’ research, how-ever, Colorado snow is melting—and fueling peak runoff—two to three weeks earlier than it did in the 1970s. Changes are related to warming cli-mate trends and are additionally affected by phe-nomena such as “dust on snow” and heightened evapotranspiration rates for forest plants. All causes lead to the same effect—earlier and pos-

sibly reduced runoff.When Colorado’s snow

melts early, water comes to people and water man-agers before it can be fully put to use. Reservoirs and water storage can help trap and hold water for use later in the year. But Wil-liams believes reservoirs aren’t enough to ease con-cern surrounding overall reduced runoff: “We can’t engineer our way out of it through the construction of new dams.”

Impacts reach beyond water managers—forests can’t intentionally bank water. When snow melts early, water may run off before forest vegetation can use it; then soils dry out. “Your fire danger just goes through the roof,” Williams says.

Compounding the effect of early snowmelt on water supply, plant activity may also begin earlier, resulting in increased evapotranspiration; plants release more water to the atmosphere, further re-ducing runoff. A 2010 study coauthored by Landry found that runoff was decreased by about 5 percent when plants became active earlier in the year.

Another contributing factor is what’s known as dust on snow. The Center for Snow and Avalanche Studies’ data show as many as three to 12 dust events each year. When dust from lands disturbed by agriculture or development settles on snow, the dark layer absorbs more of the sun’s heat, reduces

reflectivity and causes snow to melt faster. Landry and others, including Brad Udall at the University of Colorado’s Western Water Assessment, have shown that dust is a factor in early and rapid runoff. The amount of dust settling on the Rocky Moun-tains, according to their joint report published in the 2010 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sci-ences, has increased over the past 150 years by as much as 600 percent.

Temperature, snow depth, snow water equiva-lents, radiation and other factors all play a role in early or reduced runoff as well. When there just plain isn’t a lot of snow, for example, snow melts earlier. “Precipitation is still the principle factor determining snowmelt behavior,” Landry says. “First and fore-most you have to have a snowpack.”

—Caitlin Coleman

Researchers take climate measurements near an elevation of 12,000 feet on Niwot Ridge, 20 miles west of Boulder, in the 1950s.

iSto

ck.c

om

© C

ente

r fo

r S

now

and

Ava

lanc

he S

tudi

es

University of Utah graduate students Annie Bryant (left) and McKenzie Skiles collected dust samples from a snowpit at Rabbit Ears Pass between Kremmling and Steamboat Springs in 2010. Dust events, which can cause snow to melt faster, leave behind dark layers in the snowpack.

Cou

rtes

y Jo

hn M

arr

and

the

Niw

ot R

idge

LTE

R p

rogr

am a

rchi

ves

1 2 C o l o r a d o F o u n d a t i o n f o r W a t e r E d u c a t i o n | y o u r w a t e r c o l o r a d o . o r g

Water is Opportunity

Water Recruiters Wear Green The slogan, “If you’re going green, you got to think BLUE,” adorns the cover of a career pamphlet from an American Water Works Association chapter in Texas. Closer to home, the Pueblo Board of Water Works includes “promoting environmental values” on its career brochure. They hope the message, which highlights water utilities’ role in resource stewardship and sustainability, will resonate with the next generation of employees.

“The millennial generation reacts to a different message than baby boomers in what is important to them in taking on a job or starting a career,” says Paul Fanning, public relations administrator at the Pueblo Board of Water Works. Fanning uses “green talk” when speaking with younger potential employees as it has a more inspirational and emotional appeal, he says. And why not?

“We say that at heart, we are the original green industry,” says Cynthia Lane with the American Water Works Association. While it’s a shift for people to view utility jobs as green or progressive, public and environmental health rest in the hands of water and wastewater utilities, Lane explains. Perhaps blue really could be the new green. —Caitlin Coleman

Working With Water: A Career Awaits Stability and reliability—that’s what we expect from our water utility service. Those are also the qualities one finds in water utility sector employment. And, along with the element of social responsibility, those are the qualities water utilities hope will attract the next generation of employees.

According to the Water Research Foundation, as much as 31 to 37 percent of the water workforce could retire within the next 10 years. Even without the looming exodus of retiring baby boomers, the water utility sector, which includes both drinking water providers and wastewater treatment, is ex-pected to need additional employees in coming years—up to 45 percent more—in order to adapt to more stringent regulations, add and replace pipe-lines and treatment plants, and meet the demands of a growing population. Although the high level of expected turnover poses a challenge for utilities, it’s a great opportunity for job seekers.

“A lot of people retiring have been there forever,” says Cynthia Lane, who directs sustainability pro-grams for the American Water Works Association, a nonprofit educational association that provides re-

sources for water utility professionals. “We’re losing that knowledge, and we’re losing the people who saw working at utilities as a good, stable profession that supported their family and gave them a sense of well-being that their job makes a difference to others.”

To fill open positions, some utilities have estab-lished training programs and recruitment websites. Many utilities are specifically in need of operators and technicians. There are also plenty of other jobs in the field, from engineers and project managers to biologists and communication specialists.

At Ute Water Conservancy District in the Grand Valley, water treatment operators at the highest certification level are making $57,000 annually with benefits. With a high retention rate—99 percent this past year—the district hasn’t yet needed to recruit. “We’re a steady industry,” says Kalanda Isaac, who works in human resources and risk management at Ute Water. “The pay and benefits are generally quite good, and I think people like knowing that they’ve done something good for people.”

—Caitlin Coleman

Career-Ready Training Opportunities>> Connect directly with water utilities: For drinking

water, wastewater and stormwater utility em-ployment opportunities, resources and training programs in Colorado, visit getintowaterco.org. For national opportunities, check out workfor-water.org. Looking for a job with a specific water or wastewater utility? Many offer apprenticeship and internship programs.

>> Gain technical training and on-the-job experience: Colorado’s community colleges and water utilities are collaborating to provide tech-nical training for treatment plant operators and technicians. Red Rocks Community College in Lakewood and Pikes Peak Community College in Colorado Springs started training programs a few years ago. West Slope utilities saw a similar need and created a training program with Western Colorado Community College in Grand Junction. The first class from Western will graduate with associate’s degrees in Applied Science in Water Quality Management in 2014.

>> Pursue a college degree to be used in water utility work: The rate at which students earn bach-elor’s or master’s degrees in science and tech-nical fields has declined in the United States from one in six in 1960 to just one in 10 in 2000, according to the Water Research Foundation. Colorado’s top colleges and universities offer programs in higher education that would give any graduate an edge when applying for a water or wastewater utility job. Check out these top Colorado water programs:

>> Metro State University of Denver’s new One World, One Water Center offers an interdis-ciplinary water studies minor.

>> The Water Center at Colorado State Univer-sity offers water courses or a water minor.

>> The Water Center at Colorado Mesa Univer-sity has degree programs and continuing

education courses.

—Caitlin Coleman

A water utility employee changes out a reverse osmosis filter in a water treatment plant.

© iS

tock

.com

(2)

The Rising Cost of Bringing Water to a Faucet Near You

The good old days. remember when movies were just $0.20,

when the town of Vail was tiny, and when “conservation”

wasn’t part of your vocabulary? Or remember just 10 years

ago when water bills were half what they are today?

By Caitlin Coleman

Things have changed. As water services have expanded

to meet demand, so too has the cost of those services.

“There is no difference between a water bill, an airline fare

or the cost of McDonalds,” says Peter Binney, manager of

sustainable infrastructure for Merrick & Company and former

director of Aurora Water. “People see costs going up and

they think, ‘What the heck is going on?’”

H e a d w a t e r s | W i n t e r 2 0 1 3 1 3

A gallon of bottled water at Safeway goes for $1.29. For the same price, Denver Water delivers 498 gallons directly to customers’ homes.

1 4 C o l o r a d o F o u n d a t i o n f o r W a t e r E d u c a t i o n | y o u r w a t e r c o l o r a d o . o r g

Water rates have surged in the past de-cade, doubling across much of Colorado. Nationally, according to the American Wa-ter Works Association, water and wastewa-ter charges for 1,000 gallons of water have increased annually by 4.7 percent and 4.9 percent respectively—a rate nearly double the annual Consumer Price Index increase of 2.5 percent. (By comparison, the aver-age electricity rate in Colorado increased by just 1.6 percent between 1990 and 2011.) At the same time, the roles of water and wastewater utilities have changed, and the environment they operate in is wrought with expense. “I don’t think we’ve done a good job of making people understand, appreci-ate and support why our water bill is what it is,” Binney says.

The charges on customers’ water bills in-corporate more than just the volume of liq-uid that pours from the tap or flushes down the toilet. They cover the cost of hiring and training staff, building and maintaining in-frastructure, installing improved technology to meet regulatory requirements, paying for electricity to pump and treat water, provid-ing water for firefighting and other emer-gency services, protecting existing water sources and acquiring new ones, planning for drought, and more.

Water utilities exist to meet community needs; many are public entities. Some, like Aurora Water, operate within the city gov-ernment structure and are governed by the city council. Others, like the Greeley Water and Sewer Department, are governed jointly by the city council and an appointed board of directors. Then there are the special dis-tricts, like the Eagle River Water and Sanita-tion District, quasi-municipal corporations governed by an elected board of directors. In all cases, water and wastewater utilities fill a necessary role across Colorado. “The ability to provide low-cost reliable service is absolutely essential to a community’s quality of life and economic viability,” says Wayne Vanderschuere, general manager in water services at Colorado Springs Utilities.

Keeping Pace With GrowthEarly public water systems in the United States expanded substantially in the early 20th century, largely due to fire danger. Cities were highly flammable and needed a consistent, high-pressure water supply capable of dousing fires. Giant infernos in San Francisco and Chicago provided the impetus for resizing pipes across the country. Today’s engineers continue to size pipes in order to meet demand for firefight-ing, as opposed to drinking water or toilet flushing, says David LaFrance, executive director of the American Water Works As-sociation. Public water systems have since evolved further, making our water safer to drink, and treating our wastewater so thor-oughly that many water-borne diseases

have been virtually eliminated. In many cases, utilities have innovated

and allowed communities to grow, Bin-ney points out. Look at Los Angeles in the 1920s and 1930s, Las Vegas in the 1970s and 1980s—the water systems they had in place were stifling growth because they were too small, but the communities didn’t let infrastructure define them; they built am-ple water systems to meet their needs.

The same was true in Colorado’s Eagle River Valley, where the Eagle River Water and Sanitation District has been consis-tently growing since the 1962 founding of Vail. As the resort community matured, the district had to keep pace. “We were having to make large investments in infrastructure,” says Becky Bultemeier, finance manager for the Eagle River district.

Now, Front Range cities like Aurora con-tinue to face the realities of providing water—and collecting wastewater—for a large and growing population. “There was no question in the minds of the mayor or chambers of commerce that as people wanted to locate there [in Aurora], they were going to be able to provide the services,” Binney says. Au-rora Water had to figure out how to meet the demand, and the expanded infrastructure meant an increase in rates. “It’s a question of what kind of community do you want to live in? A community that can suit your needs?”

The city of Grand Junction made a differ-ent decision when, in the 1950s, it chose not to expand its system. People outside city limits wanted to connect with the city’s wa-ter system, but Grand Junction didn’t think there would be enough growth in the Grand Valley area to warrant running water lines to those outliers, says Rick Brinkman, Grand Junction’s water services manager. In 1956, those without water service formed a con-servancy district—Ute Water. In the 1970s, Clifton Water District also secured a more reliable source from the Colorado River. Today, the three systems are connected, but abut one another, limiting each other’s growth. “We just got surrounded,” Brinkman says. “We [Grand Junction’s water services] haven’t grown very much because we’re pretty much landlocked.”

Investing in TomorrowJust as communities decide on growth for public water systems and utilities respond to that direction, the public, water boards and city councilors strive to keep water rates in check. Public water entities are non-profits, and because they operate in a mo-nopolistic setting, there are some controls placed on their finances. Many have some ability to establish funds that roll over from year to year, used to stabilize revenues or build up capital for infrastructure projects. But, for the most part, they operate based on their costs of service in a pay-as-you-go system. Ultimately, the vast majority of the

WATERLAWPATRICK|MILLER|KROPF|NOTO

�e world�s �ost precious resource deserves

a law �r� �ocused only on water

ASPEN • BASALT DENVER • TULSAwww.waterlaw.com

800.282.5458

©

H e a d w a t e r s | W i n t e r 2 0 1 3 1 5

revenue a water utility uses to provide for the community comes from customer wa-ter rates. “Rates,” reiterates Greg Kail, di-rector of communications for the American Water Works Association. “That’s how they pay for their operations and manage their assets into the future.”

In addition to rates, utilities charge tap fees when a new house or business comes online. In theory, tap fees should cover the costs of expanding water and wastewater systems, but big projects still have to be financed in advance. Municipal systems typically fund major repairs and other in-frastructure work by issuing bonds that are repaid over time.

Since the economic downturn, many cit-ies haven’t experienced ample growth to finance the infrastructure they built to ac-commodate expanding populations. “There are no more tap fees coming in; that’s dried up,” Bultemeier says of the Eagle River Val-ley. So, to service its debt, the district relies more heavily on existing customers. “That puts pressure on our rates.”

The American Water Works Association conducts a state-of-the-industry survey each year, speaking with about 2,000 util-ity professionals. The same issues regularly rise to the top: water infrastructure needs, regulatory challenges and the ability of utili-ties to finance those needs. Those same issues weigh heavily on utility managers in Colorado, and have been magnified in recent years by the challenging economy.

Much of Colorado’s infrastructure was built 30 to 50 years ago, or earlier. In the meantime cities have been able to rely on that infrastructure without making additional large capital investments. “Our generation

has not experienced that cost before,” Kail says. “It was our parents, our grandparents, our great-grandparents who put most of the pipes in the ground. We’ve arrived at a new moment in our country’s history.”

The severity of the need to update infra-structure varies by utility. Vanderschuere estimates that about 75 percent of Colo-rado Springs Utilities’ budget is allocated for repairing and modernizing infrastructure. Some of the city’s infrastructure dates back to the 1800s, while the most recent seg-ments were built between the 1950s and 1970s. Colorado Springs is also looking to-ward the future; the utility is in the process of building its Southern Delivery System, laying more than 50 miles of pipe to deliver water stored in Pueblo Reservoir northward to Colorado Springs, Fountain, Security and Pueblo West. The project’s first phase will cost about $1 billion, to be paid over 40 years by customers and developers through increased water rates and tap fees.

The job of meeting demands for growth, however, is largely viewed differently by utili-ties than it was 50 years ago. Since large water projects have become increasingly difficult to permit, cities are putting more effort into managing demand—focusing on conservation and efficiency to better use available water. Not only is conservation a public expectation, it comes back to cost, Binney says. Large capital projects cost hundreds of millions of dollars. “Public rate-payers, policy makers, city councilors…they expect you to find ways to solve problems so you don’t go through the rate increases,” Binney says. “Water conservation is the minimum point of entry to actually running any utility now. And it’s a good thing.”

At the same time, water conservation poses its own set of financial challenges. Utilities need a budget to staff conservation programs, fund outreach campaigns and finance rebates. When conservation is ef-fective, water suppliers collect less income because consumption drops, while costs to utilities to continue providing services remain fixed or increase over time. “I call it the near-perfect storm,” says Bultemeier. “We’ve spent years telling people, ‘Don’t buy our product,’ and we’ve built facilities for growth. Now people are buying less and the growth is coming slower than project-ed, so our current customers have to pay those fixed costs.”

Adapting to New ChallengesThose fixed costs are going up in the Ea-gle River Valley and elsewhere. New state nutrient regulations are requiring utilities to better treat their wastewater for nitrogen and phosphorous, which can produce large algal blooms in water bodies. When those plants die off, the decaying matter deprives the water of oxygen, posing problems for aquatic life. The U.S. Environmental Protec-tion Agency requires states to limit nitrogen and phosphorous pollution. Now, the Colo-rado Department of Public Health and En-vironment will require 44 facilities to install additional treatment—total costs are esti-mated at $1.5 billion.

“This is a big deal,” Bultemeier says, with emphasis. Small utilities are exempt from complying with the new rules, and the larg-est utilities are better able to distribute the cost of treatment plant upgrades among their many customers. Eagle River Water and Sanitation District is just big enough

Mat

thew

Sta

ver

Becky Bultemeier (left) oversees finances for the Eagle River Water and Sanitation District in Vail, in a balancing act to keep revenues on par with fixed costs and capital improvements. At the end of 2012 (right), about 30 miles of pipeline—more than half of what will be needed—had been installed for the Southern Delivery System regional water project. The project, slated for completion in 2016, will transport water stored in Pueblo Reservoir to communities as far north as Colorado Springs.

Cou

rtes

y C

olor

ado

Spr

ings

Util

ities

This graphic is courtesy of Xylem

Profile Ann TerrySpec ia l D i s t r i c t Assoc i a t i on o f Co lo rado

H e a d w a t e r s | W i n t e r 2 0 1 3 1 7

Ann Terry is a familiar face at the state Capitol. There she represents special districts from around the state, help-ing legislators to understand their specific concerns. For the past three years, Terry has served as executive director of the Special District Asso-ciation of Colorado, dividing her time between advocacy work, project management, and meetings or train-ings with any number of the organi-zation’s 1,355 member districts.

Many of the special districts SDA represents have some tie to

water and sanitation services, but they also provide a wide range of other functions, including fire protection, hospital and emer-gency care, parks and recreation, and library services. “The com-mon tie is that these are local governments created for specific purposes,” says Terry.

In all cases, citizens came together to tax themselves or charge usage fees in order to provide a needed service to the community. “It’s my ideal government,” says Terry. “Special districts are the clos-est form of government to the people. All are governed by a board of elected officials, so they answer to the people and property owners who they represent.”

With a law degree and a background of serving as a lobbyist at the Capitol and in Colorado criminal justice, Terry took the helm at SDA in 2009. Her ability to understand complex issues and bring a new perspective to those issues made her a perfect fit for the position.

Now, as part of SDA’s three-member advocacy team, Terry works

to both construct and shape public policy that affects member dis-tricts. In 2010, she worked to defeat measures 60, 61 and 101, which would have eliminated certain taxes special districts rely on. “They [the referendums and proposition] would have been harmful to all forms of local government,” says Terry.

Currently, SDA is working with fire districts and the Colorado Di-vision of Fire Safety on several bills related to wildfire issues. And, she says, “We are actively monitoring the new state nutrients require-ments [for wastewater treatment] very closely. We are concerned with the unfunded mandate to districts to achieve compliance.”

Terry believes her ability to interact with all kinds of people with diverse backgrounds has helped her bring a customer service ap-proach to her job. “I love the idea that special districts affect Colora-do in such a positive way, and that I have a chance to interact with not only SDA members, but with other local governments, as Colorado works toward a healthier economy,” she says.

For member organizations, SDA’s annual conference features edu-cational and training opportunities and assistance through its leader-ship academy, individual workshops, publications and board member trainings. In addition, districts can post their transparency notices on SDA’s website, where the public can access board member names and contact information, meeting dates, and mill levy information.

At the Capitol, Terry takes every opportunity to share special dis-trict success stories. “For the public and state legislators to under-stand the successes, we need to highlight special districts and how they can be used to assist a community.” —Jayla Poppleton

SDA will host its annual conference for members in Keystone in Sep-tember 2013. Anyone interested in presenting hot topics in water is invited to apply beginning in February or March at www.sdaco.org.

that it has to comply, and because of its to-pography, the district uses three wastewa-ter treatment plants, each of which is sub-ject to the new regulations. “We’re looking at a $90 million improvement in wastewater over the next 10 years,” Bultemeier says. “Those are not numbers we’ve ever used before. Our last improvements, when we to-tally improved the wastewater plants in the ‘90s, we spent $20 million.”

Of course, even $20 million is a lot of money. The city of Longmont plans to spend $20 million to comply with the new nutrient regulations—that is in addition to $20 million in other upgrades the city had already planned to complete during the same time period. The upgrades will be funded through rate increases that will raise the average Longmont household’s monthly sewer bill from $22.08 in 2012 to $35.80 by 2018. Small commercial users and multi-family buildings will face higher bills. Initially, bonds and cash will cover the costs of the projects—repaid by rate-

payers over the next 20 years. Then there are federal regulations that

serve to protect water quality, but can drive up costs. “As the Clean Water and Safe Drinking Water acts continue to move for-ward in time and more stringent regulations spin off of those, we have to employ tech-niques and technologies which can be very costly to remain in compliance,” Vander-schuere says. “From an industry perspec-tive, it’s going to be expensive.”

Still, the national and state regulations on water quality serve a key purpose. By limit-ing contamination from both man-made and naturally-occurring substances, they ensure waterways remain vibrant and healthy, and protect humans from life-threatening illness—benefits that, if understood, most customers would likely be willing to pay to preserve.

The American Water Works Association runs an “Only Tap Water Delivers” campaign to raise awareness about water utility service. “It plays on the fact that water is out of sight and out of mind. The advertisements bring

that water infrastructure above-ground and ask the customer, ‘If only our water infrastruc-ture could talk to us, what might it say?’” Kail says. “I think it’s having an impact, but we’re talking about many decades of people pay-ing under $3 for 1,000 gallons of water. When you think about what we pay for less essential things, it really is astounding.”

The cost of water, for the utility and the customer, will only continue to climb, right along with the cost of electricity and infra-structure and the price of securing new wa-ter supplies in an increasingly competitive market. It is, after all, a scarce resource, and without substitute. And for that, people will simply have to pay.

“I think this is a major change for water, how we provide the service,” Binney says. “The real water utility managers are social scientists, communicators, team leaders and strategists. We in the water industry need to do a better job of working with communities, having them understand what the value of water is.” q

Connect with the American Water Works Association’s Only Tap Water Delivers Facebook page to learn more about investing in water infrastructure: www.facebook.com/OnlyTapWaterDelivers.

By Jerd Smith

It is just after 8 a.m. on a bright fall morning in Erie. At

the Lynn J. Morgan Water Treatment Plant, Evelyn Crocfer,

a plant operator, and Bruce Chameroy, chief of operations,

have been on the job for an hour. They work in a sunny,

window-filled room that is part operations center and part

gleaming laboratory.

Dozens of water samples taken from different sites around

the system sit on a counter. As a quality control measure,

Crocfer checks the samples for various constituents first

thing, carefully recording results as residents begin their day.

Across the room, a large computer screen glows with

diagrams of the water treatment plant and the delivery system.

This supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) system

gives a detailed, underground view of everything water-

related, from old town Erie out to its polished Vista Ridge

neighborhood and golf course.

Beyond the TapA mostly buried network of infrastructure calls for our attention

1 8 C o l o r a d o F o u n d a t i o n f o r W a t e r E d u c a t i o n | y o u r w a t e r c o l o r a d o . o r g

New pipe awaits installation in Aurora (top). Bruce Chameroy (right) completes daily inspections at Erie’s water treatment plant to ensure the automated system is running smoothly.

Kev

in M

olon

ey

Ron

Mey

er

H e a d w a t e r s | W i n t e r 2 0 1 3 1 9

Ninety-one percent of Coloradans get their domestic water from surface supplies such as reservoirs, lakes and rivers, while

the other 9 percent rely on groundwater tapped by wells. Source: Colorado Division of Water Resources

2 0 C o l o r a d o F o u n d a t i o n f o r W a t e r E d u c a t i o n | y o u r w a t e r c o l o r a d o . o r g

Chameroy and Crocfer check the com-puter and know almost instantly how much water is being consumed throughout the system, and what the capacity is in various storage tanks and reservoirs. This morning, the plant is quiet. It has adequate treated water stored to meet the day’s forecasted demand of 1.5 million gallons. This is enough water for Erie residents to cook breakfast, shower and get their children off to school. By contrast, that number exceeds 7 million gallons on hot summer days when sprinkler systems kick into high gear, and the plant ramps up to run nearly at capacity.

Chameroy and Crocfer are members of a full-time staff of seven responsible for ensur-ing that Erie’s rapidly growing population has enough water each day and that the precious liquid is safe to drink and tastes right. Their day starts with an inspection of this hyper-modern water treatment plant, an automated facility that has sophisticated sensors, pres-sure gauges and filters that work around the clock so that Erie, population 20,000 and counting, can run its water system with a handful of people working 7 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. seven days a week, instead of the 24-hour staffing older facilities require.

Most water utilities use SCADA systems

now, but large utilities, such as Denver Wa-ter still staff their systems round-the-clock. No matter how they’re staffed, water utilities must work closely with police and fire de-partments and residents to ensure they can respond quickly if and when there is an emer-gency. Sophisticated alarm systems tell on-call operators if there’s been a sharp change in water pressure, for example, which may indicate a major water main break.

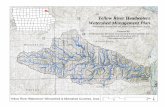

Delivery systems are often supplied by vast collection systems that capture and transport mountain runoff. Erie, for instance, gets most of its water from the upper Colo-rado River west of the Continental Divide, through the Northern Colorado Water Con-servancy District’s Colorado-Big Thompson Project. Erie’s water arrives each day, hav-ing originated as snowmelt on some of the tallest peaks in Rocky Mountain National Park, via a 13-mile tunnel beneath the Con-tinental Divide, many miles of additional tunnels, multiple reservoirs, and a 37-mile pipeline that comes down from Carter Lake. From there, the water is delivered into raw water storage and held for treatment.

Roughly half of the water Front Range resi-dents use comes from West Slope rivers. But dozens of communities, such as Castle Rock

and Parker, rely on groundwater pumped from deep in the ground. Regardless of the water’s source, it all must be treated, and treatment methods vary depending on water quality and the utility’s age.

A Growing InvestmentAs Chameroy and Crocfer go about the quiet, vital work of delivering water, hun-dreds of other water professionals repeat the same rituals across the state. Accord-ing to the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, some 2,050 public water systems are in operation here, ensur-ing Coloradans have enough water to cook, clean, water lawns and manufacture every-thing from beer to shoes.