Headwaters Winter 2005: Projects

-

Upload

colorado-foundation-for-water-education -

Category

Documents

-

view

219 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Headwaters Winter 2005: Projects

PLANNING FOR COLORADO’SWATER FUTURE

C O L O R A D O F O U N D A T I O N F O R W A T E R E D U C A T I O N | W I N T E R 2 0 0 5

Study Predicts Water Shortage by 2030 | CSU Water ArchivesRehab Projects Support Winter Fisheries

Colorado Foundation for Water Education

1580 Logan St., Suite 410 • Denver, CO 80203303-377-4433 • www.cfwe.org

MISSION STATEMENT

The mission of the Colorado Foundation for Water Education is to promote better understanding of water resources through education and information. The Foundation does not take an advocacy position on any water issue.

STAFF

Karla A. BrownExecutive Director

Kevin DarstStaff Writer

OFFICERS

PresidentDiane Hoppe

State Representative

1st Vice PresidentJustice Gregory J. Hobbs, Jr.

Colorado Supreme Court

2nd Vice PresidentBecky Brooks

Colorado Water Congress

SecretaryWendy Hanophy

Colorado Division of Wildlife

Assistant SecretaryLynn Herkenhoff

Southwestern Water Conservation District

TreasurerTom Long,

Summit County Commissioner

Assistant TreasurerMatt Cook

Coors Brewing

At LargeTaylor Hawes

Colorado River Water Conservation District

Rod KuharichColorado Water Conservation Board

Lori OzzelloNorthern Colorado Water Conservancy District

TrusteesRita Crumpton, Orchard Mesa Irrigation District

Lewis H. Entz, State Senator

Frank McNulty, Colorado Division of Natural Resources

John Redifer, Colorado Water Conservation Board

Tom Pointon, Agriculture

John Porter, Colorado Water Congress

Chris Rowe, Colorado Watershed Network

Rick Sackbauer, Eagle River Water & Sanitation District

Gerry Saunders, University of Northern Colorado

Ann Seymour, Colorado Springs Utilities

Reagan Waskom, Colorado State University

Headwaters is a quarterly magazine designed to provide Colorado citizens with balanced and accurate information on a variety of subjects related to water resources.Copyright 2005 by the Colorado Foundation for Water Education. ISSN: 1546-0584

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Colorado Foundation for Water Education thanks all the people and organizations that provided review, comment and assistance in the development of this issue.

LETTER FROM EDITOR ...........................................................1

CFWE HIGHLIGHTS .............................................................2

IN THE NEWS ......................................................................3

LEGAL UPDATE .....................................................................4

CSU WATER & AG ARCHIVES ...............................................6

FISH IN THE WINTER ............................................................8

SWSI ..............................................................................10

FIRM YIELD .......................................................................14

Northern Integrated Supply Project ........................................ 15

So. Municipal Supply Pipeline ................................................. 16

Windy Gap Firming ................................................................ 17

Moffat Collection System ........................................................ 18

On the Drawing Board ............................................................ 19

ORDER FORM ....................................................................21

�����������������������������������

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �

�������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

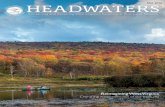

About the Cover: Cars speed up and down Interstate 70 on a Colorado evening. Crowded interstates like this are one indication of the state’s growth. Water managers, recreational and environmental interests

are looking ahead, trying to balance population growth with water resources.

David Wright, Citizen Planners, p. 15

Gary Behlen, Erie’s director of public works, p. 15

Delph Carpenter, CSU Water and Agriculture Archives. p. 6Delph Carpenter, CSU Water and Agriculture Archives. p. 6

The theme of this winter edition of Headwaters is the water supply programs and projects currently in various stages of planning across the state.

To that end, it is important to note that these articles are not meant to provide an exhaustive list of potential water projects or to suggest that they are the best or only answers to the state’s projected water shortages.

Many other solutions are involved in that much larger problem, including non-structural alternatives such as conservation, legal and policy changes, as well as adjustments in Coloradans’ expectations, values and lifestyles.

Still, we wager that the number and diversity of the projects presented will come as a surprise to many readers. If most people in Colorado have no idea where the water in their kitchen faucet comes from, perhaps they might also be surprised to find out just how many water supply projects are under consider-ation across the state.

Combine these planning efforts with all the ongoing studies, computer models and court battles about how much water the fish need or how much water it takes to have a reasonable kayaking experience—and we can all easily get lost in the details.

At least in the process of planning we do have a chance to open our minds to bigger ideas, to listen more, to change directions or forge ahead. At least that’s one way to start the New Year.

Watermarks

Editor and Executive Director

HEADWATERS – WINTER 2005 1

Fletcher Mountain, 13,951 feet, Tenmile Range

Planning For a New Year

Eric

Wun

row

2 COLORADO FOUNDATION FOR WATER EDUCATION

Join CLE International and the Colorado Foundation for Water Education, March 7 and 8 to discuss long-term solu-tions for acquiring, using and protecting water in Colorado.

The 4th Annual Colorado Water Law Conference will be held at the Marriott City Center Hotel in downtown Denver. The conference agenda includes a panel of diverse experts who will discuss impor-tant issues such as:

• How Will Colorado Meet Our Water Needs in 2030?

• Water Users’ Compliance with the Endangered Species Act

• Integrating Municipal and Agricultural Water Supplies

• and more…The feature presentation, A View from

the Denver Water Board, will be given by

Denise S. Maes, Esq., commissioner of the Denver Water Board.

More than 100 people are expected to attend. Speakers will include representatives from Colorado State University, Colorado Water Conservation Board, Environmental Defense, Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District, U.S. Department of the Interior and the area’s top water and environmental law practitioners.

Colorado Foundation for Water Education members are also eligible for a $100 discount off the full $595 tuition for this conference.

For more information or to register for the conference, log onto www.cle.com or call (303)377-6600. Media pass-es for this event are available by calling CLE International.

Colorado Water Law ConferenceMarch 7-8, 2005

Water Educators’ ConferenceMARCH 29-30, 2005

It’s time for the second annual Water Educators’ Conference March 29-30, at the Hotel Colorado in Glenwood Springs.

This year, panels of practicing teachers will report back from the classroom: what works and what doesn’t. Other speakers will share their expertise from successful water education programs around the state. Leading water resource policy makers will also help get conference participants up to speed about what water issues may

make the headlines in the coming year.Our evening reception on Tuesday

March 29 provides a great opportunity to meet other Colorado educators in a relaxed atmosphere and view their educa-tional programs. Exhibit booths are avail-able, please contact the Foundation to sign up today.

For a conference agenda or registration details, contact CFWE at (303)377-4433, or visit www.cfwe.org.

Peter Roessmann with the Colorado River Water Conservation District gets fourth and and fi fth grade students thinking about rivers as part of the Granby Water Festival.

DENVER—The Colorado State Supreme Court heard arguments Dec. 6 in a case that could determine the mini-mum amount of water necessary for a “reasonable recreational experience” at Colorado’s many whitewater parks and kayaking courses.

The Colorado Water Conservation Board and the state engineer’s office, Colorado’s water law enforcer, are fighting a 2003 water court ruling that sided with the Upper Gunnison Water Conservancy District and its application for a white-water course downstream of the City of Gunnison. The CWCB and the state engineer’s office opposed the amount of water requested by the Gunnison district, claiming it exceeded the state-mandated “minimum” flow necessary for a “reason-

able recreational experience.”Under a state statute, the CWCB

reviews applications for recreational in-channel diversions and makes factual find-ings and recommendations to the water court. The Supreme Court will decide whether the water court’s judgment or the CWCB’s judgment should prevail.

The water court in its 2003 deci-sion rejected arguments that Gunnison’s recreational in-channel diversion request, which asked for more water than the board’s recommendation, was too high. The Supreme Court will also decide whether the water court was wrong when it said that limitations on the amount of recreational instream water rights infringe on the state constitution.

Supreme Court Decision Will Shape the Future of Colorado’s Whitewater Parks

DENVER—Court heard arguments Dec. 6 in a case that could determine the mini-mum amount of water necessary for a “reasonable recreational experience” at Colorado’s many whitewater parks and kayaking courses.

Board and the state engineer’s office, Colorado’s water law enforcer, are fighting a 2003 water court ruling that sided with the Upper Gunnison Water Conservancy District and its application for a white-water course downstream of the City of Gunnison. The CWCB and the state engineer’s office opposed the amount of water requested by the Gunnison district, claiming it exceeded the state-mandated “minimum” flow necessary for a “reason-

Supreme Court Decision Will Shape the

Water Educators’ ConferenceMARCH 29-30, 2005

DENVER—Colorado watershed groups have joined together with similar organi-zations in Utah and Montana to help bring federal dollars into the Rocky Mountain West for the protection of headwaters riv-ers and streams.

In January the Colorado Water Conservation Board is scheduled to review a proposed resolution to support this fed-erally-funded regional initiative to help watershed groups implement water con-servation projects throughout Colorado. Supporters of the plan note that although Colorado’s rivers supply water to 19 states and Mexico, there are scant resources available to protect and maintain that

water supply. Similar coalitions through-out the country have been established to protect regional bodies of water such as the Great Lakes and Chesapeake Bay, and are currently receiving federal funding.

However, building the necessary polit-ical momentum for what could be a more than $20 million funding request could be difficult for Western states because they lack the political clout of Eastern states and because the group would not focus on one specific water body, observ-ers say. Existing bills still in committee in Congress, such as the National Drought Preparedness Act or Water 2025, could be used as a vehicle for this proposal.

However, a variety of options are currently being investigated.

Colorado has more than 40 local water-shed protection groups working side-by-side with government agencies and regional water districts to address a variety of issues including irrigation diversion improvements, stream and floodplain res-toration, water conservation, habitat pro-tection, water quality, acid mine drainage and community education and outreach. They receive some state and federal fund-ing but need a higher profile and more money to be successful, supporters say.

Coalition Seeks Federal Dollarsto Help Protect Colorado Rivers

HEADWATERS – WINTER 2005 3

Mic

hael

Lew

is

NEPA was designed to provide the fed-eral agencies that fund, issue permits or are otherwise involved with federal proj-ects with a clear understanding of how different actions generate different envi-ronmental results. It also seeks to identify strategies to reduce those impacts.

At the heart of the NEPA process is a study called an Environmental Impact Statement, or EIS. These docu-ments identify the “purpose and need”

of the proposed action, list all reason-able alternatives (also briefly describing alternatives eliminated from consider-ation), evaluate current environmental conditions, estimate potential impacts to specific resources such as air and water quality, and propose mitigation strategies to reduce impacts.

In addition to evaluating environmen-tal impacts and alternatives, an EIS pro-vides an opportunity for public scrutiny

Want to Build a Water Project?

NEPAYou Better Know

By John Morton

As public concern for environmental health escalated during the 1960s, Congress introduced more than 30 environmental protection bills between 1967 and 1971. One

of those most familiar to organizations involved in water

supply development is the National Environmental Policy Act, or NEPA.

Signed into law January 1, 1970, the act requires federal officials to study

the environmental ramifications of any proposed federal government

action that could “significantly” affect the quality of the environment.

4 COLORADO FOUNDATION FOR WATER EDUCATION

and involvement. NEPA procedures are designed to help ensure that environmen-tal information about a proposed federal action is available to the public before a decision is made. NEPA provides several opportunities, including public meetings and written comments, for the public and interested parties to participate.

Today’s EIS reports are thought by some officials to be easier for the public to read and understand, though they are generally much more encompassing than early statements.

“Early EISs were more of a brochure. They might have been harder to read but they were 50 pages,” says David Merritt, chief engineer for the Glenwood Springs-based Colorado River Water Conservation District, who led the district through a five-year NEPA process in the 1980s with Wolford Mountain Reservoir, a joint ven-ture with Denver Water. “Now, they might be easier to read but they’re 500 pages.”

“NEPA is designed to be a public process,” says Nicole Seltzer, a spokes-person for the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District. “At several points, you’re required to show your hand to the public. You can’t get around that. Why not go ahead and embrace it fully?”

Agencies also use the EIS to show compliance with other federal environ-mental requirements. For example, the reports are often used to demonstrate compliance with the Endangered Species Act and to document consultation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The EIS can also document steps taken to comply with the National Historic Preservation Act, which addresses historic properties and archeological sites.

The NEPA review process only applies to projects that require some kind of federal decision. It does not apply to pri-vate sector or state and local government actions unless those projects require an element of federal oversight and decision making. Federally-funded highways, for example, require an EIS. Reservoirs that need a Section 404 permit from the Army Corps of Engineers to discharge dredge or fill material into rivers and streams, or reservoirs that require a special-use per-mit from the U.S. Forest Service, are also required to complete an EIS.

Most water development projects in Colorado, especially large-scale storage projects, require an EIS because they need

an Army Corps permit or because they require some other type of federal action.

“In Colorado, we’re seeing more (envi-ronmental impact statements) because there’s more going on as a result of growth and the recent drought,” says Jerry Kenny, an engineer at HDR Engineering in Denver. “Generally, most water proj-ects will trigger NEPA. It’s not impossible, but it’s very difficult to do a water project and avoid NEPA.”

The NEPA process typically lasts two to three years, Kenny says, though it can last as little as 14 months. Merritt says Wolford Mountain took five years to get through the process, and that was consid-ered “pretty quick.” And the timeframe is often determined by the degree of contro-versy associated with a project.

Still, some water providers consider NEPA an onerous process because of its costs in time and money. “It can be viewed as a roadblock, but frankly it’s much bet-ter viewed as a way to get folks involved,” Merritt says. “In balance, ultimately you’re dealing with a public resource.”

SHOULD IT GET A FONSI?Because some federal actions do not

have the potential to cause “significant” environmental impacts, the agency or the project proponent may prepare a more limited analysis, called an Environmental Assessment. This study helps determine whether or not the project will result in significant environmental impacts—and whether an EIS is necessary.

If the EA determines the project could cause significant impacts, the lead federal agency (in conjunction with other project proponents) must prepare an EIS. If it is determined that the proposed action will not have significant impacts, the agen-cy can conclude the NEPA review with a Finding of No Significant Impact, or FONSI, allowing the permit to be issued and construction to proceed.

STARTING THE PROCESS

The EIS process begins when an orga-nization that wants to build, for example, a water reservoir, applies to the fed-eral agency that will fund or otherwise issue permits for their project. That fed-eral agency—such as the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation or the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers—then publishes a notice in the Federal Register publicly declaring its

intent to prepare an EIS. That notice also starts what is called the scoping process, when the public and other organizations comment to the federal agency about issues that need to be considered. Some agencies hold one or more public meet-ings to get comments during the scoping phase. Environmental studies of the veg-etation, surface water, groundwater, wild-life and a full gamut of natural and human resources are also initiated at this time.

When the scoping process and environ-mental field work are complete, the feder-al agency prepares a Draft Environmental Impact Statement, files it with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and cir-culates it for review by interested parties, who have at least 45 days to comment. Though called a draft, this document is nearly complete and includes a full disclosure of the impacts of the action. Depending on the project, it can take months or years to move from scoping to a draft EIS.

After the end of the comment period, which usually lasts longer than the mini-mum required 45 days, the federal agency prepares a Final Environmental Impact Statement, files it with the EPA and makes it available to the public. The final state-ment must address all comments received on the draft version and include any modifications or factual corrections.

Then the federal agency must wait at least 30 days to make a decision on the proposed action. This 30-day period allows the public and interested parties to further review the final document and provide comments.

“People want to be included in the pro-cess,” Merritt says. “I don’t think (NEPA’s drafters) saw how much public involve-ment there would be. It changed the way we do water projects.” ❑

Editor’s Note:John Morton has worked for HDR

Engineering for 10 years as vice president in charge of their environmental science pro-gram for the Midwest. Involved in NEPA activities for more than 30 years, Morton also was a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers employee for 20 years, working on a variety of water storage projects, including Denver Water’s Two Forks project, which was vetoed by the EPA.

NEPA

HEADWATERS – WINTER 2005 5

Mic

hael

Lew

is

The well-known 20th century water lawyer Delph Carpenter helped divide the waters of the Colorado River by developing a legal agreement in use to this day. In the process, he kept voluminous reports,

diaries and letters that decades later would almost be lost to, of all things, a flood.

Now those records are safe and will soon be available to researchers and the public alike at Colorado State University’s Water Resources Archive. Created in 2001, the archive is a col-laborative venture by CSU and the Colorado Water Resources Research Institute to preserve and protect Colorado’s water his-tory. Water engineers, historians and researchers say the archives will play an invaluable role in centralizing and preserving the photographs, maps, records, let-ters and other primary sources that can help modern-day schol-ars understand how Colorado’s communities, economy and life-style have been shaped by our scarce water resources.

Carpenter, a leader in the creation of the Colorado River Compact of 1922, became known as the “Father of Colorado River Treaties.” His com-mitment to negotiation, not litigation, spawned many complex interstate compacts which determined how Colorado would

share its rivers with adjacent states. Carpenter died in 1951, leaving his collection of water memoirs with his family.

But when a clogged culvert pushed groundwater into the Greeley-area basement of Donald Carpenter—Delph’s son—and

threatened boxes of irreplaceable documents, the family knew the papers needed a new home.

In a triage effort, the docu-ments were first stored at the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District offices in Loveland. But the collection was molding and in need of profes-sional restoration. Looking for a place that could both care for and provide access to the papers, the Carpenter family decid-ed to donate the collection to Colorado State University in May 2004. Currently, the university is busy restoring and organizing Carpenter’s 90 boxes of water his-tory that make up what is likely one of the most valuable assets in its archives.

Among the documents in the Carpenter collection are letters from President Herbert Hoover, who became a friend of Delph’s during the compact negotiations and credited Carpenter’s “tenac-

ity and intelligence” with seeing the compact negotiations to their end.

Prolonged drought in the West accompanied with unprec-

6 COLORADO FOUNDATION FOR WATER EDUCATION

WAT E RARCHIVES H E L P H I S T O R Y COME ALIVE

By Kevin Darst

A potato harvest crew poses for a portrait near Greeley. Photo by F. E. Baker.

edented water use and growth has recently renewed tensions in the Colorado River Basin—tensions quite similar to those present 80 years ago when Delph worked to craft the Colorado River and other compacts. As author and historian Daniel Tyler found in his recent book “Silver Fox of the Rockies: Delphus E. Carpenter and Western Water Compacts,” many of Carpenter’s strategies and lessons-learned are very salient to the tough water negotia-tions facing Colorado and the West today.

That’s what makes the Carpenter col-lection the most important acquisition to the university’s water archives, says Robert Ward, director of the Colorado Water Resource Research Institute at CSU.

“It’s going to be a very contentious time and understanding history is going to be more important than ever,” Ward says. “The Carpenter collection is most signifi-cant because it deals with a key segment of the evolution of water development in the West. Carpenter led the charge.”

Other collections in the archives include the personal papers of the inven-tor of modern-day water measurement devices, Ralph L. Parshall, a collection of historic groundwater data, as well as organizational records from groups such as the Colorado Association of (Soil) Conservation Districts.

Patty Rettig, head archivist for the uni-versity’s water and agricultural collections,

knows these collections are one of a kind. Although she acknowledges the uni-

versity will allow limited access to some collections until they can be better orga-

nized and restored, Rettig says she is pleased the university is working toward providing public access to all these impor-tant and one-of-a-kind materials. ❑

HEADWATERS – WINTER 2005 7

The CSU Water Resources Archive contains about 25 collections and more than 700 boxes of material. The contents of 16 water collections are listed online at the archive’s Web site, http://lib.colostate.edu/water.

Head Archivist Patty Rettig (above) says that a select number of documents, maps and photos will be digitized and available on the Web starting in early 2005, though in-person visits to the archive continue to be the best, and in most cases only, way to access the primary refer-ences, maps and photos that help bring alive the history of water and agriculture in Colorado.

Rich

Abr

aham

ason

/The

Col

orad

oan

CSU

Wat

er &

Agr

icul

ture

Arc

hive

s

8 COLORADO FOUNDATION FOR WATER EDUCATION

ISHING IN THE OLDISHING IN THE OLDFISHING IN THE OLDCIMPROVING WINTER HABITAT MAKES FOR HEALTHIER FISHERIES

By Ken Neubecker

HEADWATERS – WINTER 2005 9

Fishlooking for a home in the cold waters of Colorado’s high mountain streams are having

a tough time, especially in the winter. However, as river recreation and fishing become more important to the economy and lifestyle of mountain communities, rehabilitation projects to improve fish habitat are increasingly popular. What proponents have found is that design-ing river habitat to help fish through the long winter months is good for the trout, and good for business.

Winter is a lean time for Colorado’s rivers and streams. Flows and tem-peratures drop to the lowest levels of the year as the water supply is locked up in the deepening snow pack. Groundwater seeping quietly into the riverbed may offer the only source of replenishment to the stream. Only spring will herald the release of built-up stores when snow melts and the loud voice of Colorado’s rivers returns.

Yet winter life for fish and aquatic insects is not as dire as it may seem. Adapted over thousands of years to the annual cycle of spring floods and winter lows, many cold-water river residents thrive in this icy environment.

Ultimately, fish survival in the winter stream depends not so much on water temperatures, but on the complexity and diversity of their stream habitat and the shape and variation of the river channel. Deep pools where the water runs slower and where there is abundant protec-tive cover from stream bank vegetation provide ideal winter fish habitat. And despite the cold, insect food for the fish is often abundant throughout the winter. Fish behavior in cold-water streams also changes. They become less territorial and more gregarious, gathering together and resting in the deeper pools.

However, habitat degradation and low flow conditions in the stream can make winter a difficult time for fish and insects. Many of Colorado’s high country streams have been damaged by human activities, past and present. Runoff from mining, agriculture, highways and devel-opment can fill the river’s pools and riffles with sediment. Diversions of water out of the stream for snowmaking, irrigation, or drinking water, for example, can reduce the high-velocity flows necessary to cre-ate the deep pools and open channels

fish need to survive. Diversions have also diminished the total volume of water in Colorado rivers at certain times of the year. Before reservoirs and diversions, river channels were wider to accommo-date floods and greater surges of water. But in modern-day rivers with lower flows, in some cases the result is a dis-persed shallow river with few pockets of deep habitat to hold over-wintering fish.

In degraded river channels, improv-ing fish habitat during wintertime low flow conditions can be critical to the year-round health of the fishery. Recent river restoration projects on the Blue River through the town of Silverthorne focused on re-tooling shallow gravelly channels to provide more deep pools linked by fast flowing riffles.

Although releases of cold water from the bottom of Dillon Reservoir helped turn the Blue River into a Gold Medal fishery, low flows—particularly during drought—were slowly degrad-ing the resource.

To mobilize a restoration effort, Trout Unlimited, the town of Silverthorne, Denver Water and many other agencies worked together to raise money and resources. Andy Gentry, president of the Gore Range Chapter of Trout Unlimited, was instrumental in building momen-tum for the project. “It was a broad-based community effort,” he explains. “Everyone recognized the importance of the river and pitched in, from all the governmental agencies to non-prof-it organizations and private business. That’s what made it such a success.”

Collectively the community raised over $90,000 to match a $94,750 grant from the National Forest Foundation. The town of Silverthorne organized the various partners and developed a restoration plan. Denver Water pro-vided additional funding and access to key portions of the river for the resto-ration work.

Large boulders were used to vary the depth and sinuosity of the new channel. The old wide riverbed was then left as floodplain, where high flows can spread out, dissipating energy and watering the newly planted riparian vegetation.

According to Troy Thompson of Ecological Resource Consultants, Inc., who led the design and construction of the Blue River project, “As more and

more people look at doing projects like these they are realizing the importance of planning and building for winter habitat.” He adds that many high coun-try streams are challenged to maintain ecological balance because “the reduced flow of today is struggling within a channel made by the much larger flows of the past.”

Winter fishing had always been pret-ty good on the Blue River below the dam, but the restoration work “definite-ly improved the fishery,” according to Barry Kirkpatrick of Cutthroat Anglers in Silverthorne.

Despite common misperceptions about barren winter streams, fishing is a year-round activity in Colorado and rivers like the Blue River below Dillon Reservoir are often open throughout the winter. And despite the cold tem-peratures, many high-country fly fish-ing shops and guides remain busy throughout the winter.

Bill Perry of Fly Fishing Outfitters in Avon opened his shop 10 years ago as a year-round fly fishing store, one of the first in Colorado to do so. “Lots of peo-ple who come out to ski are surprised to find out that Colorado has year-round fishing,” says Perry, who adds that he has guides on the river with clients every day of the year. “Maybe they can’t go skiing, so they go fishing. Besides, there aren’t many other fishermen out so it’s a great time to go.”

Helping the rivers and the fish dur-ing the lean winter months also helps Colorado’s economy. Fishing alone was worth $1.6 billion dollars annually and employed over 15,000 people in Colorado in 2001, according to a study by the American Sportfishing Association.

Low flow conditions, whether caused by drought, diversion or both, are now fairly common in the headwater rivers and streams of Colorado. At the same time, the value of our rivers for fish-ing and recreation is increasing. River rehabilitation projects like those on the Blue River are working to meet not only the changing ecological needs of these unique streams, but also the changing social and economic demands of the communities they support. ❑

Editor’s Note: Ken Neubecker is the west slope organizer for Colorado Trout Unlimited.

10 COLORADO FOUNDATION FOR WATER EDUCATION

The numbers generated by the Statewide Water Supply Initiative are plentiful, splashed across 500 pages in the state’s most compre-hensive water supply assessment to date. In and beyond those numbers lies Colorado’s map to its water future.

The report shows that water providers have plans to meet about 80 percent of projected 2030 water demand. They say they need new pipelines and water storage to get there. If they can’t develop new water, they’ll buy farms and agricultural water to meet future demand. All the while, they’ll be competing with recreational and environmental interests who claim that same water can best help the state by remaining in the river.

TAKING THE INITIATIVEC O M P R E H E N S I V E S T U DY O U T L I N E S C O L O R A D O ’ S

F U T U R E WAT E R N E E D SBy Kevin Darst

HEADWATERS – WINTER 2005 11

he Statewide Water Supply Initiative, or SWSI, seeks to identify Colorado’s future water demands, as well as what programs—including water storage, con-servation and the drying of agricultural land—the state’s water providers are pro-posing to meet those needs.

“It’s probably more information on Colorado water than you’ve probably ever had at one time,” says Matt Heimerich, a Crowley County commissioner and member of the Arkansas River Basin study group.

Led by the Colorado Water Conservation Board, beginning in September 2003 SWSI project managers held four meetings in each of the state’s eight major water basins. The meetings brought together representatives from cit-ies, development, agriculture, the envi-ronment and recreation, participants who had been chosen by the CWCB through nominations in the months before the study started.

In December 2004 the CWCB deliv-ered the study to the State Legislature. What SWSI found on a broad scale was that, in a best-case scenario, Colorado water providers have plans to meet most of the state’s municipal water demand by 2030, assuming the projects and processes identified by SWSI pan out.

But the shortfall is daunting, project-ing a shortage of at least 118,000 acre-feet of water, enough for 700,000-900,000 people, by 2030. And the numbers are contested, with experts from some fields calling them high and others claiming them to be low.

“The numbers matters less than the themes,” says David Nickum, who repre-sented Trout Unlimited in the South Platte River Basin during the Statewide Water Supply Initiative.

Those themes, identified during the 18-month, $2.7 million study, are simple. New and expanded reservoirs will play a part, as will conservation. One of the study’s major findings, however, is that taking water from irrigated agricultural land and converting it to municipal use will be a primary source of water for cit-ies, one that will be increasingly more attractive if other projects fail. As many as 400,000 acres of Colorado’s irrigated agri-cultural land could be dried up by 2030, according to SWSI.

“They really highlighted what was going to happen to ag,” says John Stencel,

president of the Rocky Mountain Farmers Union, a Colorado-based group with members in Colorado, Wyoming and New Mexico. “It gives more urgency to start looking at a state water plan. Nobody wants to talk about that, but it could help us protect some of our ag water.”

The study did not address the impacts of irrigated land losses or suggest solu-tions, except to say that new water proj-ects would take some pressure off of agriculture.

“They did not try to quantify solu-tions,” says Reeves Brown, president of the Western Slope lobbying group Club 20. “But the identification of unmet demand begs that question.”

Finding solutions wasn’t SWSI’s man-date, says Rick Brown, the study’s project manager. The initiative was intended to pro-duce a “reconnaissance-level” look at water supply and demand across the state, as well as to facilitate dialogue between what had essentially become competing interests.

“We didn’t answer every question, but I didn’t expect to,” Rick Brown says. “We tried not to impose solutions, not give answers, but frame the issues…Many people thought it would be a scoring method that would spit out an answer. It’s an initiative, not a plan.”

What it did spit out were projections, basin-by-basin, of gaps in water supply needed for homes, agriculture, indus-try, and other uses. According to SWSI, overall, state water providers lack plans for 118,000 acre-feet of projected 2030 demand, a 20 percent shortfall. Much of the unaccounted-for demand was found in the urban South Platte basin, where the state demographer estimates another 2.4 million people will live by 2030.

Conservation will ease but not elimi-nate the state’s looming water shortage, the study suggested. Passive conservation, the effect of current federal regulations that require water-efficient residential and commercial plumbing fixtures, is expected to cut 5 percent out of demand by 2030, according to SWSI. More-advanced con-servation efforts such as education, rate hikes, leak detection systems and rebates for efficient toilets and washers could lop 12 percent off future water usage. More stringent measures like steeper rate hikes, turf restrictions or the elimination of ultra-thirsty landscaping could strip more than one-third off the 2030 estimated demand.

“Reliance on water conservation to

By Kevin Darst

he Statewide Water Supply Initiative, or SWSI, seeks to identify Colorado’s future water demands, as well as what programs—including water storage, con-servation and the drying of agricultural land—the state’s water providers are pro-posing to meet those needs.T

We didn’t answer every question,

but I didn’t expect to…We tried

not to impose solutions, not give

answers, but frame the issues…”

—Rick BrownSWSI Project Manager

Bria

n Ga

dber

y

12 COLORADO FOUNDATION FOR WATER EDUCATION

meet all additional water demands is not possible,” says the executive summary of the report. “While citizens will respond by temporarily reducing water use during drought conditions and many are willing to make technological improvements in water use efficiency, there are technical and social limits to long-term water conserva-tion. Conservation levels that would need to be imposed to meet all future demands would result in a significant change in the quality of life for most Coloradans.”

Recent dry years and accompany-ing water restrictions have raised public awareness of conservation, a trend that should continue even if the state faces wet years ahead, says Bart Miller, the water programs director for Western Resource Advocates. In that sense, Miller says SWSI somewhat undermined the effect of con-servation on Colorado’s potential water supply shortfall.

“I think it’s likely cities across

Colorado will do more (conservation),” says Miller, who agrees that conserva-tion will be just one of several tools used to cover future demands.

Rod Kuharich, CWCB executive direc-tor and the study’s director, says the SWSI team assumed a “fairly aggressive conserva-tion plan” in its estimates. Still, he contends that conservation won’t be the proverbial silver bullet for future water shortages, and that means water providers will likely have to develop new water sources.

“New water entails development of new water rights and, in almost all cases, some sort of storage scenario,” Kuharich says. “New water also carries the (possi-bility) of out-of-basin diversions. You just can’t ignore that situation.”

The contentious issue of transferring water from one basin to another was not addressed by the study, a point of criti-cism for some participants on the Western Slope. Trans-basin diversions are a sig-

nificant concern for Western Slope areas where most of the state’s water originates, and which stand to lose more water to growing Front Range urban areas. One of the most notable transfer recipients is the South Platte River Basin, where most Coloradans live, which receives 345,000 acre-feet of water from the Colorado River Basin each year. Much of that is pumped across the Continental Divide by Denver Water and the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District, who still have unde-veloped water rights on the Western Slope that could ship yet more water from the Colorado to the South Platte Basin.

The study sprouted enough inter-basin concerns that a second phase of SWSI, scheduled to begin this month, will bring representatives from both sides of the mountains into one room for a series of meetings. “(Transbasin diver-sions are) the big elephant in the room we all wanted to ignore,” said Dave

Estimated 2030 Water Demandby Basin vs. Current Anticipated Supply

T. Wright Dickinson (left), Karen Shirley (center) and

Jeff Crane (right) were members of Statewide Water Supply Initiative

“roundtable” groups that met four times over

13 months to assess Colorado’s water supply

and demand forecast. Dickinson said he hoped the study would produce a “vision” for the state’s

water future.

River Basin Currentaf/yr.

Projectedaf/yr.

Shortfall

North Platte

100 100 0

South Platte

319,100 409,700 22%

Colorado 58,900 61,900 5%

Yampa & White

22,300 22,300 0

Gunnison 12,500 14,900 16%

Arkansas 80,900 98,000 18%

Rio Grande 4,200 4,300 2%

Dolores & San Juan

13,900 18,800 26%

Bria

n Ga

dber

y (3

)

HEADWATERS – WINTER 2005 13

Merritt of the Colorado River Water Conservation District at the November CWCB board meeting.

Project manager Rick Brown says having those inter-basin meetings during SWSI’s tight schedule could have swamped the study.

“We needed to understand how individual basins are meeting their needs,” Brown explains. “The only way to be successful…is to look at our own basins first. You can’t understand your own needs if you’re looking at others’ needs. Water becomes emotional so quick. People turn to advocacy to protect those interests. It’s important to move away from advocacy. I don’t think we can look at solutions until we do that.”

At the CWCB’s November meeting, where SWSI was presented to the board, several participants said the study’s biggest benefit might have been convening a collage of interests and people that don’t normally find themselves face-to-face.

“It helped a little bit to start developing some trust,” says Jeff Crane, who represented the North Fork River Improvement Association, a Paonia-based non-profit, in the Gunnison basin meetings.

T. Wright Dickinson, a Maybell rancher and Yampa basin participant, says he hopes the study can help foster a state water “vision.” “What I really hope comes out of this is a vision of how we in Colorado can keep our cake and eat it, too,” he said at the November CWCB meeting.

Yet the study’s participants remain divided on its value. While Tom Cech, executive director of the Central Colorado Water Conservancy District, called SWSI a “smart move, very forward thinking, very wise on a tough issue,” participants in at least two basins sent letters to SWSI managers complaining about the study’s process and results. Some envi-ronmental and recreation representatives feel the study had little to say about those needs.

Durango fly-fishing shop owner Tom Knopick called SWSI “business as usual” and an attempt to create support for traditional water develop-ment projects.

“I heard a lot of talk about water projects…but there was little talk about environment and recreation,” says Knopick, who co-owns Duranglers Flies and Supplies in Durango and represented recreational interests on the study’s roundtable for the southwestern basins. “It almost sounded like a plan to endorse those traditional projects people have been working on.” Adds Knopick, “What we shouldn’t forget is that “a lot of this increase in population comes for (recreation).”

One of SWSI’s 10 major findings was that population growth would spur environmental and recreational uses of water. At the same time, recreation and environmental interests will likely push project devel-opers to include more benefits for recreation and the environment, in exchange for support of those projects. And that could fuel conflict.

According to the study’s executive summary, “The development of reliable water supplies for agricultural, municipal, and industrial uses will compete with the desire to preserve the natural environment and to maintain and enhance water-based recreation opportunities.”

SWSI’s executive summary also included eight recommendations developed by the Colorado Water Conservation Board. One suggested tracking the projects and processes to meet future water demands identified during SWSI; another proposed developing and supporting implementation plans for those processes. And a third urged standard-ized water-use reporting by cities and industry.

Club 20’s Reeves Brown had his own recommendation.“We are recommending that policy makers don’t take this summary

as a mandate to create new policy or laws,” Brown said. “We need to allow the current entities in place to develop those solutions.” ❑

10 Major Findings of theStatewide Water Supply Initiative

1. Significant increases in Colorado’s population, together with agricultural water needs and an increased focus on recreational and environmen-tal uses, will intensify competition for water.

2. Projects and water management planning pro-cesses that local municipal and industrial water providers are implementing or planning to implement have the ability to meet about 80 percent of Colorado’s M&I water needs through 2030.

3. To the extent that these identified municipal and industrial projects and processes are not success-fully implemented, Colorado will see a signifi-cantly greater reduction in irrigated agricultural lands as M&I water providers seek additional permanent transfers of agricultural water rights to provide for demands that would otherwise have been met by specific projects and processes.

4. Water supplies are not necessarily where demands are; localized shortages exist, especially in head-water areas, and compact entitlements in some basins are not fully utilized.

5. Increased reliance on nonrenewable groundwa-ter for permanent water supply brings serious reliability and sustainability concerns in some areas, particularly along the Front Range.

6. Regional solutions can help resolve the remain-ing 20 percent gap between municipal and industrial supply and demand, but there will be tradeoffs and impacts on other water uses– espe-cially agriculture and the environment.

7. Water conservation will be relied upon as a major tool for meeting future demands, but conservation alone cannot meet all of Colorado’s future water needs. Significant water conserva-tion has already occurred in many areas.

8. Environmental and recreational uses of water are expected to increase with population growth. These uses help support Colorado’s tourism industry, provide recreational and environmental benefits for our citizens, and are an important industry in many parts of the state. Without a mechanism to fund environmental and recre-ational enhancement beyond the project mitiga-tion measures required by law, conflicts among M&I, agricultural, recreational, and environ-mental users could intensify.

9. The ability of smaller, rural water providers and agricultural water users to adequately address their existing and future water needs is signifi-cantly affected by their financial capabilities.

10. While SWSI evaluated water needs and solu-tions through 2030, very few M&I water pro-viders have identified supplies beyond 2030. Beyond 2030, growing demands may require more aggressive solutions.

FIRMYIELD

Water supply projectsin the works statewide

The Statewide Water Supply Initiative, an 18-month study of

Colorado’s water supply and demand projections, helped catalog

dozens of these water development projects in various stages of

completion.

Four of the biggest proposed projects would bring more drink-

ing water to Front Range areas, while the rest include plans to reha-

bilitate smaller reservoirs, construct pipelines or hold more water

for late-season releases to fisheries, among others purposes.

The following pages include a look at some of these propos-

als, from those in the permitting process to those barely on the

drawing board.

Numerous water supply projects are currently in development across the state. What water providers are looking for is “fi rm yield” or the ability to provide a dependable water sup-ply available in all years, including drought.

14 COLORADO FOUNDATION FOR WATER EDUCATION

HEADWATERS – WINTER 2005 15

By Kevin Darst

Smaller cities and water districts in northern Colorado are courting Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District’s first proposed storage project in more than two decades to help them meet the demands of population growth.

The Northern Integrated Supply Project, or NISP, would construct two new reservoirs with water rights from the Cache la Poudre and South Platte rivers to supply 17 “emerging providers”—gen-erally small towns and rural-domestic suppliers—in northern Colorado with a combined 34,400 acre-feet of water annually for their growing populations. It would also provide 12,000 acre-feet of storage for water from NCWCD’s existing Colorado-Big Thompson Project.

Glade Reservoir, the larger of the two proposed NISP reservoirs, would hold about 177,000 acre-feet of Cache la Poudre River water in a 260-foot-deep, five-mile long lake in a valley north of Fort Collins. U.S. Highway 287, which currently runs north through the valley, would be moved east.

Galeton Reservoir north of Greeley would hold 30,000 acre-feet of water from the South Platte and Poudre rivers. This could be traded with two local ditch systems for water upstream, allowing the NCWCD to deliver water to NISP par-ticipants when and where they need it. Participants say the water exchange with downstream irrigators is crucial to the viability of NISP.

The project won’t come cheap. It’s expected to cost about $370 million, or about $10,000 per acre-foot. That’s less expensive than a share of existing NCWCD water, but still a sizeable invest-ment for the smaller providers.

The town of Erie expects to get 5,000 acre-feet of new water and an additional 2,500 acre-feet of storage from NISP. The new water alone could cost Erie about $50 million but would likely cover Erie’s water needs through the town’s buildout, says Gary Behlen, Erie’s director of public works.

“I don’t know what the alternatives are,” Behlen says. “That’s the concern the other towns have.”

The project could cost Little Thompson Water District, which serves more than 6,500 customers between Longmont and Loveland, about $40 million for 4,000 acre-feet. While the district needs more new water supplies, funding Little Thompson’s stake in the project could be challenging, District Manager Hank Whittet says.

“It’s a financing issue,” Whittet explains. “There’s no question about whether we need it.”

But David Wright, who heads Citizen Planners in northern Colorado, has ques-tions about the feasibility of the project, given the smaller providers involved. He says the project would complement or even subsidize “rapid growth” in the area and argues that rate payers should have a chance to vote on whether they want their provider to participate in NISP. Some NISP participants say growth would pay for the project.

“If people don’t want the growth, they wouldn’t want to pay for a reservoir,” Wright contends. “People like me and the people I represent really don’t want this rapid growth.”

Fort Lupton, which until several years ago relied on groundwater wells to supply its residents, would get 2,300 acre-feet from NISP, enough to double the town’s population. Fort Lupton’s town admin-istrator says the community needs new water, but the $23 million price tag has tempered some expectations.

“We’re fully committed (to NISP),” Fort Lupton Town Administrator Jim Sidebottom says. “The only question that may arise is—can we afford 2,300 acre-feet. We’ve been trying to plan to be able to do it.”

East Larimer County Water District, which serves about 5,300 taps in north-east Fort Collins and unincorporated Larimer County, opted against new water

from the project but could store 2,000 acre-feet of its current NCWCD water in NISP’s reservoirs. Storing more water would allow the district to stretch existing supplies by storing water in wet years for use in dry years, ELCO General Manager Webb Jones says.

“We looked at buying new yield in the NISP project, but it’s pretty expensive,” Jones says. “Our board doesn’t want to saddle cur-rent customers with a lot of debt.”

The NISP project is currently in the National Environmental Policy Act pro-cess, and has just completed is project scoping which included several public comment meetings and identification of numerous project alternatives. Work on its Environmental Impact Statement could start in early 2005. ❑

NISP Participants 1. Berthoud 2. Central Weld County Water District 3. East Larimer County Water District 4. Eaton 5. Erie 6. Evans 7. Fort Collins-Loveland Water District 8. Fort Lupton 9. Fort Morgan 10. Lafayette 11. Lefthand Water District 12. Little Thompson Water District 13. Morgan County Quality Water 14. North Colorado Water Authority 15. North Weld County Water District 16. Severance 17. Windsor

N O R T H E R NINTEGRATEDS U P P L YP R O J E C T

F I R M Y I E L DM

icha

el L

ewis

16 COLORADO FOUNDATION FOR WATER EDUCATION

By Dan MacArthur

Colorado Springs is staking its bets on its proposed Southern Delivery System as the best way of supporting continued growth and addressing potential urban water shortages by as early as the end of the decade. But the city still must withstand environmental scrutiny and overcome a major permitting obstacle that could fur-ther delay its ambitious schedule.

The Southern Delivery System is a regional project that would use storage space in Pueblo Reservoir to deliver water owned by the communities of Colorado Springs, Fountain and Security to the growing Pikes Peak region.

The $539 million first phase of the project would involve construction of a 43-mile-long, 66-inch diameter pipeline drawing water from the Arkansas River, at or downstream of Pueblo Reservoir, and running north to Colorado Springs. This would also include three or four pump stations, and one water treatment plant. Several possible pipeline alignments are being studied.

As part of the projected $400 million second phase, two new reservoirs would be constructed: Jimmy Camp Creek Reservoir near Colorado Springs and Williams Creek Reservoir near the town of Fountain. A water treatment plant in the area would also have to be expanded.

Long stalled by opposition from Pueblo, the Southern Delivery System moved closer to becoming a reality in early 2004 when Colorado Springs reached an agreement with the Pueblo City Council and the city’s Board of Water Works that ended years of conflict. In exchange for dropping their opposition to the pipeline,

Colorado Springs agreed to dedicate a share of its Arkansas River water rights sufficient to maintain more consistent flows through downtown Pueblo.

Despite that agreement, however, Colorado Springs still faces fierce oppo-sition from an unconvinced contingent of critics. They continue to contend that Colorado Springs has not seriously con-sidered alternatives that are less costly and environmentally damaging. Critics cite concerns that the project would unaccept-ably reduce the quantity and quality of the Arkansas River through Pueblo—instead diverting relatively clean water above the city and returning sediment- and pollut-ant-laden water to the river via discharg-es into Fountain Creek from Colorado Springs’ wastewater treatment plant.

Colorado Springs Utilities Regional Project Manager Gary Bostrom a c k n o w l e d g e s that water qual-ity issues still must be evalu-ated and will be addressed in the Env i ronmenta l Impact Statement and a study of the Fountain Creek watershed sched-uled for comple-tion in 2007. He and others, however, express open exaspera-tion at what they regard as baseless and false fear-mongering aimed at unraveling the fabric of recently negotiated regional cooperation.

Fueled by an unrelenting series of fiery editorials in The Pueblo Chieftain newspa-per, opponents have pressed the county commissioners to block the required per-mits for the project by strengthening the county’s land-use regulations, also known as “1041 powers.” And by all indications, making it through this local permitting will still be a difficult process.

Although not directly a part of the Southern Delivery System, Colorado Springs also is pushing for eventual expan-sion of Pueblo Reservoir, which is part of the Fryingpan-Arkansas Project belonging to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. For the last 25 years, Colorado Springs and its neighbors have been purchasing and receiving so-called “Fry-Ark” water for domestic use throughout El Paso County.

While construction of the Southern Delivery System does not depend on Pueblo Reservoir expansion, it would enable Colorado Springs to maximize use of the pipeline, better regulate flows, and store non-project water it owns. In addi-tion, Bostrom notes that the agreement to maintain Arkansas River flows through Pueblo also is predicated on future expan-sion of Pueblo Reservoir.

But before any expansion could go for-ward, Colorado Springs must gain congres-sional approval for an exten-sive study of the proposal. Last-minute opposi-tion derailed an effort to secure that authoriza-tion just before the last session ended in 2004. Future efforts to authorize the expansion may suffer setbacks, given the stated opposition of U.S. Sen.-elect

Ken Salazar and his brother, John Salazar, who in November was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives and will repre-sent the Western Slope in Washington.

A draft Environmental Impact Statement studying Phase I and II of the Southern Delivery System is set for com-pletion in late 2005 with the final expected in mid-2006. Construction of the system is proposed to begin in 2009. ❑

By Dan MacArthur

C O L O R A D OS P R I N G S ’S O U T H E R N

DELIVERY SYSTEM

F I R M Y I E L D

The Southern Delivery System, a Colorado Springs Utilities plan, would use a pipeline and storage space in Pueblo Reservoir to deliver water to the growing Pikes Peak region.

HEADWATERS – WINTER 2005 17

By Kevin Darst

The idea wasn’t new: store water on the Western Slope and pump it to the Eastern Slope to satisfy rising water demand in the state’s most populated river basin, the South Platte.

In 1985, after nearly 18 years of plan-ning and permitting, Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District’s Windy Gap Project pumped its first water from the 445-acre-foot Windy Gap Reservoir on the Colorado River to Lake Granby. From Lake Granby, the water traveled east through the 13-mile-long Alva B. Adams to the Front Range.

Intended as a supplement to north-ern Colorado’s Colorado-Big Thompson Project, Windy Gap water is stored in a reservoir near Granby and pulses through C-BT reservoirs and pipelines on a space-available basis. But that arrangement has led to problems that have reduced water availability for Windy Gap benefactors. In wet years, the C-BT system has been too full to pipe Windy Gap water to the Eastern Slope. In dry years, Windy Gap’s junior water rights haven’t produced much water.

In Spring 2003, nine Windy Gap par-ticipants submitted a plan for reservoirs that would store nearly 100,000 acre-feet and improve, or firm, the reliability of 30,000 acre-feet of water from the Windy Gap Project for Broomfield, Erie, Greeley, Longmont, Louisville, Loveland, Superior, Central Weld County Water District and Platte River Power Authority.

Northern initially identified five pos-sible reservoir sites with nine variations or combinations for its in-house review. Some of those alternatives could be

scrapped because they don’t meet U.S. Army Corps of Engineers guidelines for reservoir sites.

A district spokesperson said Northern isn’t ready to release its new list of pro-posals. She said, however, that the proj-ect would probably be a combination of reservoirs on both sides of the moun-tains because a single Eastern Slope reservoir would not hold enough water to deliver the annual yield requested by Windy Gap participants.

One option previously cited by offi-cials at Northern is Chimney Hollow Reservoir, a proposed 110,000-acre-foot lake west of Loveland and Carter Lake. But the impoundment might not be big enough if interested parties Fort Lupton, Lafayette, Little Thompson Water District and the Middle Park Water Conservancy District join the project.

“That’s why we have a West Slope site we’re also pursuing,” district spokesper-son Nicole Seltzer explains.

One of the district’s original Western Slope site proposals, the so-called Jasper North site, was eliminated after engi-neers found peat-forming, groundwa-ter-fed wetlands called fens. And plans for a Little Thompson Reservoir site near Lyons, which generated much ire from residents in the area, likely will be dropped because of Army Corps screen-ing criteria eliminating sites that would inundate streams with year-round flows,

such as the Little Thompson River.Regrouping will probably set Windy

Gap Firming Project construction back to early 2008, which could hurt project par-ticipants who need the additional water for their customers, project manager Jeff Drager explains. “We want to make sure it complies with the Corps’ requirements first,” Drager says.

Exploration of new sites has upset some Western Slope residents, Drager admits. One potential reservoir site west of the Continental Divide has several homes on it, and homeowners won’t let district engineers onto their property to survey the land, he reported.

“Those homeowners aren’t thrilled about being on the list,” Drager says. “It’s a handful (of opponents) compared to (the proposed Little Thompson site), but they’re not really excited about it and I can’t blame them.”

As part of the environmental review process mandated by the National Environmental Policy Act, Northern just recently completed its scoping process where it solicited input from interested parties about various project alternatives. In the coming year, it will work with the Bureau of Reclamation to draft an Environmental Impact Statement—a cru-cial step toward obtaining the necessary federal permits that could make this proj-ect a reality. ❑

W I N D Y

G A PF I R M I NG P R O J E C T

F I R M Y I E L D F I R M Y I E L D

Windy Gap Reservoir west of Granby delivers water to Front Range cities and water districts through the Colorado-Big Thompson Project.

18 COLORADO FOUNDATION FOR WATER EDUCATION

By Dan MacArthur

Denver Water considers its proposed Moffat Collection System Project impor-tant to bring better balance and reliability to its water supply system.

Denver Water currently provides water to more than 1.2 million customers using three major water collection systems—the Moffat, South Platte and Roberts Tunnel systems—originating high in the moun-tains west of the metro area.

Providing only about 20 percent of Denver’s total water supply, the Moffat Collection System is located in the Williams Fork and Fraser river basins on the Western Slope. A series of tunnels channel that water under the Continental Divide to be stored in Gross Reservoir above Boulder and the smaller Ralston Reservoir above Arvada, where it awaits transfer to Denver’s water treatment facilities.

The proposed expansion of the existing Moffat Collection System would provide 18,000 acre-feet of dependable annual water supply to the Moffat Treatment Plant and other customers. The current collec-tion system, Denver Water contends, is not sufficiently reliable or flexible to meet existing or future demands.

With the current system, in a single severe dry year the Moffat Treatment Plant and several other water customers can run out of water. During the 2002 drought, for example, lack of water at times forced the Moffat Treatment Plant to be shut down and all water treatment shifted to the Foothills and Marston plants. In addition, to maintain water in the Moffat System, Denver Water was forced to curtail mini-

mum bypass flows (flows which keep water in the stream to help mitigate the impact of diversions) in the Fraser River Basin.

As part of the National Environmental Policy Act process and according to a 2003 scoping report developed by U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, numerous alter-native project scenarios have been identi-fied. Some examples of potential alterna-tives include: enlarging Gross Reservoir on South Boulder Creek, a new reservoir near Highway 93 and Coal Creek Canyon (Leyden Gulch), and a potable water recy-cling facility, among others.

The Corps of Engineers is current-ly preparing an Environmental Impact Statement to assess the impacts and issues associated with of each of these alterna-tives. However, the preferred alternative(s)

will only be known after the EIS is released. Originally scheduled to debut in early 2005, current indications are that the report may be delayed for several months, if not longer.

That delay troubles Grand County Manager Lurline Underbrink-Curran. These delays mean the Moffat Collection System EIS may not be reviewed concurrently with another EIS for an additional proposed project that may take more water out of the Fraser River Basin—Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District’s Windy Gap

Firming Project. She said Grand County officials strongly believe both proposals must be reviewed concurrently to assess their combined environmental, economic, social and other impacts. Environmental concerns listed in the initial scoping docu-ments included concerns for the health of the Fraser River, South Boulder Creek, water quality, land use and recreation.

Although Grand County has participat-ed in recent EIS scoping meetings and other discussion forums, Underbrink-Curran remains skeptical that Denver Water will provide any significant accommodation. “It’s not an easy solution because Denver is determined to develop the storage nec-essary for ‘firming’ its water rights,” she explains. “There’s not a lot of wiggle room for us.” ❑

����������������������

������������

������������������

�����������

������

�������������

�������������

��������������

�������������

����������������

������������

��������������

���������

���������������������

�����������������

�������

�����������

������������

����������������

��������������

�����������������

��������������

���������������������

�������������������

������������

MOFFATCOLLECTION

SYSTEME X P A N S I O N

F I R M Y I E L D

Expanding the Moffat Collection System would deliver an additional 18,000 acre-feet annually to water providers, primarily Denver Water. The added water would help keep Denver’s Moffat Treatment Plant running during dry years. The plant had to shut down in 2002 because of low fl ows.

HEADWATERS – WINTER 2005 19

ON THED R A W I N G

B O A R D

F I R M Y I E L D

The Statewide Water Supply Initiative helped inventory dozens of proposed water sup-ply projects all over the state. The following is meant to pro-vide a sample of the some of the projects on the drawing board and is not meant to be a comprehensive list.

ARKANSAS RIVER BASIN

Enlargement of Pueblo Reservoir and Turquoise Lake

The Southeastern Colorado Water Conservancy District, which manages the transbasin Fryingpan-Arkansas Project, has proposed enlarging Pueblo and Turquoise reservoirs to add an additional 69,625 acre-feet of storage. The district provides water to farmers, cities and industry in nine Arkansas basin counties.

Enlarging Turquoise Lake, which lies five miles west of Leadville and east of the Continental Divide, could cost $14.5 mil-lion, including permitting costs. Expanding

Pueblo Reservoir, which sits west of Pueblo and currently has an active capacity of about 330,000 acre-feet, could cost $75.5 million. Cities and industry would benefit most from these enlargements.

Arkansas Valley Conduit

The proposed Arkansas Valley Conduit, which would run from near Pueblo to La Junta and Lamar, could yield about 18,200 acre-feet of water annually—primarily for municipalities and agriculture—in Pueblo, Otero, Bent and Prowers counties. About one-third of the water could come from the Fryingpan-Arkansas Project, with the rest coming from exchanges with cities and agriculture. An updated feasibility study in October 2004 suggested construction of the pipeline and other facilities could cost $252 million. Federal legislation to fund the project has been proposed but not passed. The pipeline was authorized with the Fryingpan-Arkansas Project in 1962, but a proposal to build it was derailed in 1972 for lack of funding.

SOUTH PLATTE RIVER BASIN

Enlargement of Halligan and Seaman Reservoirs

After pulling out of the Northern Integrated Supply Project, the cities of Fort Collins and Greeley have plans to enlarge Halligan and Milton Seaman res-ervoirs on the North Fork of the Cache la Poudre River.

Expanding Halligan Reservoir would give Fort Collins nearly 40,000 acre-feet of storage in the reservoir and about 34,000 acre-feet more than it currently has and provide an additional 12,000 acre-feet of reliable water supply annually to the city. Halligan enlargement could cost up to $35 million, with a completion goal of 2010.

Enlarging Seaman Reservoir would net Greeley about 38,000 acre-feet more stor-age and provide the city 10,000 acre-feet of reliable water supply annually. The Seaman expansion could cost as much as $50 million. Current estimates suggest the expansion would be done by 2020. North Poudre Irrigation Company, North Weld County Water District, Fort Collins-Loveland Water District, East Larimer

County Water District and the City of Evans could join Greeley and Fort Collins in the project.

Enlargement of Standley Lake

Enlargement of Standley Lake in the South Platte basin would solidify municipal and industrial water supplies for the grow-ing north Denver suburb of Northglenn. Expanding this reservoir in Adams County by as much as 18,000 acre-feet would provide about 6,000 acre-feet of water to the city. Under previous agreements, the Farmers Reservoir and Irrigation Company would get 20 percent of the extra storage. Initial estimates said the enlargement could cost up to $50 million.

GUNNISON RIVER BASIN

A/B Lateral

In the Gunninson basin, the Uncompahgre Valley Water Users Association has been working for years on the A/B Lateral, a hydropower project. The project would pipe the existing A/B Lateral, an open canal which currently helps pro-vide irrigation water to the Uncompahgre Valley. Without compromising existing irrigation uses, the pipeline would funnel water through a new hydroelectric station to supply additional power for Delta and Montrose counties. The project could cost an estimated $65 million. Project sponsors are waiting for the final environmental impact statement from federal agencies.

Eric

Wun

row

20 COLORADO FOUNDATION FOR WATER EDUCATION

ON THED R A W I N G

B O A R D

F I R M Y I E L D

Rehabilitation of Dams and Reservoirs

Rehabilitating dams and small reser-voirs on the Grand Mesa in Delta County could create additional water storage for agricultural users in the area. The Grand Mesa Water Conservancy District, Colorado River Water Conservation District and the Colorado Water Conservation Board are partners in the plan, which would restore existing dams, rehabilitate old reservoirs, and poten-tially build new dams on the mesa.

YAMPA/WHITE/GREEN BASINS

Enlargement of Elkhead Reservoir

Enlargement of Elkhead Reservoir near the town of Hayden could begin early this year and would add 11,750 acre-feet of storage to support cities and the environ-ment in Moffat and Routt counties. About 5,000 acre-feet of storage would go to help endangered fish and environment, while the other 4,750 acre-feet could go to municipal, industrial and agricultural use, including the town of Craig. The remain-ing 2,000 acre-feet could go for either aquatic or human use.

COLORADO RIVER BASIN

Wolcott Reservoir

The proposed Wolcott Reservoir, which could be as small as 50,000 acre-feet or as big as 150,000 acre-feet, would provide water for cities on both sides of the moun-tains and could also dedicate water for the environment and endangered species. A feasibility study released last summer by the project’s sponsors indicated that the project could be economically feasible.

As proposed, the reservoir would supply water for Denver Water, Eagle County water

users and the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District. Northern and Denver Water could use Wolcott water to help meet their obligations to aid endangered fish in the Colorado River Basin. The reservoir would deliver between 13,000 acre-feet and 34,000 acre-feet of water annually to its operators on the west and east slopes, according to the feasibility study, which pegged the construction cost at between $120 million and $197 million.

Colorado River Return Project

The Colorado River Return Project, also called the Big Straw Project, would take water from near the Colorado-Utah state line and pump it back to serve users on the Eastern Slope. The Colorado Water Conservation Board sponsored a study in 2003 which found that 250,000-750,000 acre-feet of water could be developed by the project. That water would also help meet water supply needs on the Western Slope. The study also raised significant concerns about high water costs per acre-foot, environmental impacts, and techni-cal feasibility.

RIO GRANDE RIVER BASIN

Rio Grande Headwaters Restoration Project

The Rio Grande Headwaters Restoration Project, a plan to repair river systems in the San Luis Valley, would help support the riv-er’s historic functions, sponsors say. Among those functions are flood protection, irriga-tion diversion, riparian habitat and down-stream water deliveries required under the Rio Grande Compact. Restoration efforts would include stabilizing the river bank, redirecting flows, planting willows and potentially relocating existing ditch and canal diversion structures. The plan could cost $20-$30 million.

Groundwater Recharge

With depleting groundwater supplies threatening irrigated agriculture in the Rio Grande basin, a handful of water providers are proposing the construction of groundwater recharge facilities. The recharge pits could store water that would seep back into the groundwater table.

DOLORES/SAN JUAN/ SAN MIGUEL RIVER BASINS

Irrigation of New Acreage

The Dolores Water Conservancy District’s Water for Everyone Tomorrow Package (WETPACK) includes plans to provide irrigation water for about 2,500 acres of currently unirrigated land.

Structures to irrigate the first 440 acres should be completed in June 2005 and will cost about $497,000. Infrastructure to irrigate the remaining 2,100 acres could be done by June 2008 and could cost about $3.7 million. A $5.46 million Colorado Water Conservation Board loan helped fund the project.

Plateau Creek Reservoir

A new reservoir upstream of McPhee Reservoir called Plateau Creek could add 20,000 acre-feet of storage for southwest-ern Colorado. Some of this water would be dedicated to late-season releases to aug-ment extremely low flows in the Dolores River, and to improve habitat for aquatic life. Plateau Creek Reservoir, a compo-nent of the Dolores Water Conservancy District’s Water for Everyone Tomorrow Package (WETPACK), would fill with flows that would otherwise cause the downstream McPhee Reservoir to spill. Sponsors already have a court decree for the needed water but are working out issues of funding and reservoir use. ❑

Eric

Wun

row

HEADWATERS – WINTER 2005 21

Contact name:_____________________________________Company (if applicable):_________________________________________Address:_____________________________________________________________________________________________________Phone or email (in case there is a problem or delay fi lling your order):_____________________________________________________

Membership orders: How would you like this membership listed in our publications and annual membership reports?__ Under my name __ Under my company’s name __ Anonymous

__ Check enclosed __ Visa __ Mastercard __ Discover __ AmexCard number: ______________________________________________________ Expires: ____________________________________Name on card: ______________________________________________________ Signature: __________________________________

Item Quantity Member Price Price Total

Citizen’s Guide to Colorado Water Law: 2004 revised edition Explores the basics of Colorado water law, how it has developed, and how it is applied today. Updated for 2004 with important changes based on new legislation in 2003. 33 pages, full color.

$7.20 each;$5.40 each if ordering 10

or more

$8 each;$6 each if

ordering 10 ormore

$

Citizen’s Guide to Water Quality Protection For those who need to know more about Colorado’s com-plex regulatory system for protecting, maintaining, and restoring water quality. 33 pages, full color.