Headwaters Summer 2004 Water and Growth

-

Upload

colorado-foundation-for-water-education -

Category

Documents

-

view

221 -

download

2

description

Transcript of Headwaters Summer 2004 Water and Growth

C O L O R A D O F O U N D A T I O N F O R W A T E R E D U C A T I O N | S U M M E R 2 0 0 4

Colorado Foundation for Water Education

1580 Logan St., Suite 410 • Denver, CO 80203303-377-4433 • www.cfwe.org

MISSION STATEMENT

The mission of the Colorado Foundation for Water Education is to promote better understanding of water resources through education and information. The Foundation does not take an advocacy position on any water issue.

STAFF

Karla A. BrownExecutive Director

Carrie PatrickAssistant

Young Hee KimPrograms Specialist

OFFICERS

PresidentDiane Hoppe

State Representative, R-Sterling

1st Vice PresidentJustice Gregory J. Hobbs, Jr.

Colorado Supreme Court

2nd Vice PresidentBecky Brooks

Colorado Water Congress

SecretaryWendy Hanophy

Colorado Division of Wildlife

Assistant SecretaryLynn Herkenhoff

Southwestern Water Conservation District

TreasurerTom Long,

Summit County Commissioner

Assistant TreasurerMatt Cook

Coors Brewing

At LargeTaylor Hawes

Northwest Council of Governments

Rod KuharichColorado Water Conservation Board

Lori OzzelloNorthern Colorado Water Conservancy District

TrusteesRita Crumpton, Orchard Mesa Irrigation District

Lewis H. Entz, State Senator, (R-Hooper)

Frank McNulty, Colorado Division of Natural Resources

Brad Lundahl, Colorado Water Conservation Board

David Nickum, Trout Unlimited

Tom Pointon, Agriculture

John Porter, Colorado Water Congress

Chris Rowe, Colorado Watershed Network

Rick Sackbauer, Eagle River Water & Sanitation District

Gerry Saunders, University of Northern Colorado

Ann Seymour, Colorado Springs Utilities

Reagan Waskom, Colorado State University

Headwaters is a quarterly magazine designed to provide Colorado citizens with balanced and accurate information on a variety of subjects related to water resources.Copyright 2004 by the Colorado Foundation for Water Education. ISSN: 1546-0584

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Colorado Foundation for Water Education thanks all the people and organizations that provided review, comment and assistance in the development of this issue.

LETTER FROM EDITOR ..........................................................2

IN THE NEWS .....................................................................3

CFWE HIGHLIGHTS............................................................3

LEGAL UPDATE ..................................................................4

WATER & GROWTH IN COLORADO .......................................6

Leases Help Farms & Suburbs Weather Drought.................... 12

Reuter-Hess Reservoir ............................................................. 14

Pagosa Springs Gets Water Wise............................................. 16

Mutual Irrigation Company Caters to New Customers ........... 18

VOICES.............................................................................20

River of Words

ORDER FORM ...................................................................21

HEADWATERS – SUMMER 2004 1

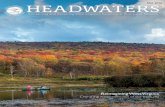

About the Cover: An imaginary shower sprinkles a housing develop-ment near the Boulder Flat Irons. A silhouetted Don Magnuson, manager of the Lake Canal Company, looks out on Windsor Lake. Photographs by Jim Richardson (Boulder), Cynthia Hunter (Magnuson) and Emmett Jordan.

Don Henrichs, High Line Canal superintendent, p.12

Denise Rue-Pastin, leading new water conservation pro-grams in Pagosa Springs, p. 16.

A larger population also means greater demand for in-stream recreation, p. 6.

CCWCD Groundwater Management Subdistrict • Central Colorado Water Conservancy District • City of Aurora Utilities • Colorado River Water Conservation District • Colorado Water Resources & Power Development Authority • Coors Brewing Company • Denver Water • Eagle River Water & Sanitation District • MWH • Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District • Ute Water Conservancy District

Charter Members

PIONEER MEMBERS

Aaron Clay • Anderson & Chapin, P.C. • Angie Graber • Ann Seymour • Anschutz Family Foundation • Aqua Engineering, Inc • Balcomb & Green, P.C. • Barbara Dallemand • Barbara Horn • Barry Cress • Big Thompson Watershed Forum • Brent Schantz • Bucher, Willis & Ratliff • Buck Rulifson • Carol Sullivan • Carolyn Clark • Case Ranch • Center Conservation District • Charles Fisk • Charles Howe • Charles McKay • Charles Waneka • Cheyenne County Commissioners • Chris Reichard • Chris Rowe • Ciliberto & Associates, LLC • City & County of Broomfi eld • Coalition for the Upper South Platte • Collins, Cockrel & Cole • Colorado Division of Wildlife • Colorado Farm Bureau • Colorado Land Investments • Colorado Rural Water Association • Colorado Water Conservation Board • Colorado Water Offi cials Association • Colorado Water Workshop • Conejos Water Conservancy District • Curry Rosato • Dale Kortz • Daniel Kaup • Daniel Tyler • Danyel Brenner • Dave Rich • David Allen • David Bailey • David Bernhardt • David Hallford • David Nelson • David Nickum • David Wagers • Delbert M. Smith • Delta Conservation District • Dianne Miller • Dick Unzelman • Dick Wolfe • Dietze & Davis, PC • Division of Water Resources • Don Ament • Don Lewis • Donna Hellyer • Douglas County • Dry West Nursery • East Grand Water Quality Board • Edith Zagona • Edward Kenyon • Elaine Davis • Elk Ridge Ranch • Enlarged Southside Irrigation Ditch • Environmental Process Control • ERO Resources Corporation • Ferdinand Hagden Chapter, Trout Unlimited • Frank Anesi • Frank McNulty • Friends of the Animas River • Fruitland Domestic Water Company • Gerry Saunders • Gretchen Cerveny • Harold Miskel • Harvest Farm (Denver Rescue Mission) • High Line Canal Preservation Association • Hon. Richard Decker • Jack Ferguson • Jake Klein • Janet Bell • Janet Enge • Jason Wolfe • Jay & Dori Van Loan • Jeff Goble • Jerry Kenny • Jim Aranci • Joel Plath • John & Susan Maus • John Porter • John Wiener • Jord Gertson • Julio Iturreria • Kathy Jeffrey • Karen Wiley • Katryn Leone • Ken Kester • Lawrence J. MacDonnell • Lee Stierwalt • Longmont Community Radio • Luther & Jolene Stromquist • Lynn Herkenhoff • Magro, LLC • Marie Mackenzie • Mark & Sara Hermundstad • Mark Campbell • Mark Smith • Martin & Wood Water Consultants • Mary Miller • Matthew Duncan • McCarty Land & Water Valuation • Meaker Cemetery District • Melvin Rettig • Merrill, Anderson, King & Harris • Michael Bauer • Miller Ranch Corp • Minion Hydrologic • Moapa Valley Water District • Mohamed Worayeth • Nancy Holmes • Nancy Porter • Nathan Fey • National Park Service Black Canyon/Curecanti • Nel Caine • North Fork River Improvement Association • NWCCOG • Offi ce of the State Engineer • Patricia Locke • Patrick, Miller & Kropf, P.C. • Paul Lee Turner • Paula Daukas • Peggy & Philip Ford • Penny Lewis • Pete Crabb • Peter Italiano • Raejean Riegel • Reagan Waskom • Richard Tremaine • Rick Sackbauer • Rio Blanco Water Conservancy District • Rita Crumpton • Roaring Fork Conservancy • Robert Marx • Rocky Mountain Guides Association • Ron Eller • S.S. Papadopulos & Associates • San Juan Water Conservancy District • San Miguel County Commissioners • Sarah Stevens • Scott Hummer & Sally Roscoe • Silverlined Productions • South Pueblo County Conservation District • South Reservation Ditch Company • St Vrain Sanitation District • State Rep Diane Hoppe • Steven Janssen, Attorney • Steven Parker • Steven Patrick • Sue Petersmann • Tanya Unger Holtz • Taylor Hawes • Terry Huffi ngton • The Hudson Gardens • The Tisdel Law Firm, PC • Tom Farber • Tom Pointon • Tomlinson & Associates • Tony Koski • Town of Aguilar • Town of Breckenridge Water Division • Town of Frisco • Town of Telluride Public Works Dept • Town of Windsor • Treatment & Technology Inc • Trees, Water & People • Tri-County Water Conservancy District • Troy Bauder • Turkey Creek Soil Conservation District • US Fish & Wildlife Service • Vranesh & Raisch, LLP • W. D. Farr • Warner Ranch • Washington Group International, Inc • Water Coalition • WaterWise Resource Action Program • Weld County Underground Water Users Assn • Wendy Hanophy • Werner Living Trust • William & Donna Patterson • William & Linda Hanson • Wyoming Water Association

HDR Engineering, Inc • Metro Wastewater Reclamation District • Southwestern Water Conservation District

Applegate Group • Board of Water Works of Pueblo • City of Grand Junction Utilities • Duncan Ostrander & Dingess • Porzak Browning & Bushong • Robert T. Sakata • St. Vrain & Left Hand Water Conservancy District • Summit County Board of Commissioners • Upper Arkansas Water Conservancy District • White & Jankowski

Arkansas River Outfi tters Association • AWWA, Rocky Mountain Section • Ayres Associates • Bishop-Brogden Associates • Black & Veatch Corporation • Bouvette Consulting • Centennial Conservation District • Centennial Water & Sanitation District • City of Boulder Water Quality & Environmental Services • City of Westminster • Clifton Gunderson LLP • Colorado Springs Utilities • Colorado State Conservation Board • David & Linda Overlin • Delta County Commissioners • Fort Collins Utilities • Gregory J. Hobbs, Jr. • Gregory Hoskin • Hydrosphere Resource Consultants • Inverness Water & Sanitation District • L.G. Everist, Inc • Leonard Rice Engineers • Lower Arkansas Valley Water Conservancy Dist • Mesa County • Middle Park Water Conservancy Dist • Pete Gunderson • Platte Canyon Water & Sanitation District • Roxborough Park Metro District • Rutt Bridges • Southeastern Colorado Water Conservancy District • Town of Fraser • Wheatland Electric Cooperative • Y-W Electric Association, Inc

Bill Yohey • Dan Gibbs • Dillon Cowan • Jean Anderson • Julie Kreps • Marian Flanagan • Michael Pease • Paul Harms • Thomas Barry • Wendy Fisher

SUSTAINING MEMBERS

ASSOCIATE MEMBERS

INDIVIDUAL MEMBERS

STUDENT MEMBERS

Colorado Water Conservation BoardEndowing Partner

Thank you!First Annual Membership Campaign

T O A L L T H O S E W H O S U P P O R T E D T H E F O U N D A T I O N I N O U R

Eric

Wun

row

HEADWATERS – SUMMER 2004 32 COLORADO FOUNDATION FOR WATER EDUCATION

CITIZEN’S GUIDE TO COLORADO WATER CONSERVATION

The latest in the citizen’s guide series, the Colorado Foundation for Water Education is pleased to present the Citizen’s Guide to Colorado Water Conservation.

Authored by Nancy Zeilig, former editor of the American Water Works Association Journal, this 33-page booklet is designed to provide a balanced over-view of the water conservation technolo-gies, incentive programs, regulations and policies promoting efficient water use in Colorado today.

Is your community or business doing all it can to use water wisely? Get informed about the opportunities and challenges for water conservation in Colorado today.

CITIZEN’S GUIDE TO COLORADO WATER LAW: 2004 REVISED EDITION

Based on new legislation in 2003, the Foundation’s first and most popular citizen’s guide has been updated for 2004 with important changes.

Written by Justice Gregory J. Hobbs of the Colorado Supreme Court, this attractive full-color guide provides a con-cise, clear overview of our water law as it works in the courts and on the ground.

Copies of the guides are $8 each, or $6 if ordering ten or more. Contact CFWE at (303) 377-4433 or visit www.cfwe.org to purchase the guides or other CFWE products.

New Publications

In its 2004 session, the Colorado General Assembly repealed the water administration fee program it instituted in 2003. Originally designed to help bol-ster the state’s declining budget for water resource management, the fee program met with significant opposition from water right holders.

House Bill 04-1402 will refund fees already paid by water rights own-ers, excluding interest. Approximately $467,000 will be refunded.

Fees originally ranged from $10 for farm irrigation and stock-watering rights to $250 for municipal, industrial and commercial water rights.

Throw that Bill Away: Water Administration Fees Repealed

Since 1998, representatives from Grand and Summit counties, the Colorado River District, Denver Water, Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District, the Northwest Colorado Council of Governments, Middle Park Water Conservancy District and other local entities have been working on a joint effort to examine water quality and quantity issues in the headwaters of the Colorado River.

Known as the Upper Colorado River Basin Project, or UPCO, this series of stud-ies is looking to identify and balance com-peting water supply needs for municipali-ties, recreation, and the environment. The study also evaluates what the basin might look like after all projected in-basin and out-of-basin water development projects have been accomplished.

An initial fact-finding and assessment report was released in May 2003. The report found that in coming decades, both

Grand and Summit counties may not be able to meet projected water demands. For domestic needs, Grand County could face an annual shortage of about 2,400 acre-feet (8,500 acre-feet if instream flow needs are considered). Summit County could fall short by 1,900 acre-feet annually.

The Upper Fraser River Basin near Winter Park was identified as one of the areas in Grand County facing the high-est risk of water crisis. Increasing water demands in Summit County are expected to focus on the towns of Silverthorne, Eagles Nest and Mesa Cortina.

Next, UPCO participants will be completing an analysis of the potential alternatives available to address projected shortfalls. Anticipated for release later this summer, the report will focus on priori-tizing and identifying possible solutions. Complete study reports are available on http://nwc.cog.co.us.

Study Projects Shortfall for Upper Colorado River Basin

n the lazy, hazy days of summer, the Foundation turns its attention to issues of water and growth in Colorado.

Our feature article summarizes some traditional and alterna-tive approaches to providing water for growth, and highlights some interesting lessons. The first lesson: water scarcity does not stop growth.

The western system of water allocation—the prior appro-priation doctrine—rests on the premise that water can be moved from where it is found, to where it is needed. And even though the current drought has resulted in watering restrictions and dried-up reservoirs, it has not curtailed new housing starts.

A 1972 law requires developers to provide evidence that their new developments will have water of sufficient quantity and quality to support whatever kind of construction proposed. Several counties now have 300-year water supply requirements for all new developments utilizing Denver Basin groundwater.

With concerns over unmitigated sprawl and long-term sus-

tainability, water providers often find themselves in a controver-sial arena. But utilities, water and sanitation districts, or mutual ditch companies are not in the growth management and land use planning business. Their main job is to provide a service, water. They’re not land use agencies; they don’t regulate land use. Instead, with imperatives to provide reliable water supplies to meet future demands, water providers find themselves react-ing to growth, not directing it.

Historically, the state legislature has deferred the majority of land use and water policies almost exclusively to local planning offices, city and county officials, citizens’ advisory boards. Larger forces such as national, state, and regional economic trends, pro-vide a behind-the-scenes directive.

This issue of Headwaters highlights how different communi-ties are pursuing different approaches to meeting future water demands. And growth marches on. That’s no surprise. Colorado is a great place to live.

WATERMARKS:Reacting to Growth, or directing it?

I

Yampa River, Dinosaur National Monument

Eric

Wun

row

Karla BrownEditor and Executive Director

HEADWATERS – SUMMER 2004 54 COLORADO FOUNDATION FOR WATER EDUCATION

Water, Growth and Land Use

Historians point out that coping with growth has been Colorado’s single greatest invigorating influence, and its single greatest concern, since World War II (Ubbelohde, Benson & Smith, A Colorado History 346-47(8th Ed. 2001)).

By the mid-1970s, environmental protection, land use regu-lation, and water supply policy had become a major focus of legislation in the Colorado General Assembly. Throughout this decade, statewide air and water quality legislation figured promi-nently—complimenting statutes such as the Clean Water Act of 1977 at the federal level.

Although the majority of land use and water policies were deferred almost exclusively to local governments, in 1974 the legislature did adopt several land use and growth-related statutes that still have significant influence today: the Local Government Land Use Control Enabling Act, House Bill 1041, and subdivi-sion water supply provisions.

LAND USE CONTROL ENABLING ACT

The Land Use Enabling Act granted towns, cities, and coun-ties broad authority to plan and regulate the “orderly use of land and protection of the environment.” According to the act, local governments have authority to:

• Regulate development in hazardous areas• Protect wildlife habitat and species• Preserve areas of historical and archeological importance• Regulate the location of activities and development that

may cause significant changes in population density• Regulate land use based on impacts to the community• Impose impact fees or other charges related to impacts

from proposed development on facilities provided as a service of the local government, such as water supply and wastewater treatment plants. (see Sections 29-20-101-108 (C.R.S. 2003)).

HOUSE BILL 1041This legislation encouraged local governments to select sites

and regulate the development of “areas and activities of state interest,” including:

• Major domestic water and sewage treatment systems• Municipal and industrial water projects• Solid waste disposal sites• Municipal or county airports• Rapid or mass transit systems• Highways and interchanges• Major facilities for public utilities• New communities• Mineral resource areas • Natural hazard areas • Areas containing, or having a significant impact upon,

historical, natural, or archaeological resources of

statewide importance • Areas around key facilities in which development may

have a material effect upon the facility or surrounding community (see Sections 24-65.1-101-502).

HB 1041 regulations were put to the test in 1989 when the Colorado Supreme Court upheld Grand County’s 1041 powers in Denver v. Grand County. Grand County argued successfully that the Colorado Constitution does not prohibit a county from requiring a permit for new or modified water projects. Although specific language in HB 1041 states that “nothing herein shall be construed as enhancing or diminishing a water right or modify-ing or amending water laws or water right decrees,” it does allow a county to condition or deny a permit for a water project that will create a nuisance or significantly degrade the environ-ment, including:

• Aquatic habitats• Marshlands and wetlands• Groundwater recharge areas• Steeply sloping or unstable terrain• Forests and woodlands• Critical wildlife habitat• Big game migratory routes• Calving grounds• Migratory ponds• Nesting areas and the habitats of rare and

endangered species• Public outdoor recreation areas• Unique areas of geologic, historic, or

archaeological importance.

HB 1041 powers were further upheld in 1994, when Aurora and Colorado Springs wanted to divert water from the Eagle River Basin for the Homestake II Reservoir, but were denied a permit from Eagle County because the project failed to comply with the county’s 1041 regulations.

In this case, the Court of Appeals ruled that “the cities’ enti-tlement to take water from the Eagle River basin, while a valid property right, should not be understood to carry with it abso-lute rights to build and operate any particular water diversion project.” Aurora and Colorado Springs are working to redesign the project to locate it outside of the Holy Cross Wilderness Area and to reduce its environmental impacts, but to date they have not reapplied for a HB 1041 permit from Eagle County.

Early use of HB 1041 powers in the context of water projects focused on trans-mountain diversion proposals. Recently, how-ever, counties on the eastern plains have taken an interest in this unique land-use enabling authority. Counties along the lower Arkansas River have adopted HB 1041 regulations requiring a permit for, among other things, the removal of irrigation water from land which has historically been irrigated. These regula-

tions address the environmental impact of agricultural dry-up: topsoil loss, noxious weed invasion, and the consequent loss of wildlife habitat. The regulations emphasize revegetation and wildlife mitigation plans as key permit conditions.

SUBDIVISION WATER SUPPLY PROVISIONS Concern about adequate water supplies for new subdi-

visions prompted the General Assembly in 1972 to require developers to provide counties with adequate evidence of sufficient water supply in terms of quality, quantity, and dependability for whatever type of construction proposed. (see Section 30-28-133(3)(d)).

Further, the General Assembly required the county to submit the proposed supply plan to the State Engineer for an opinion as to whether it might cause injury to other decreed water rights, and to evaluate if it provides sufficient supply. (see Section 30-28-136(h)(I)).

The State Engineer comments on wells and surface water supplies from municipalities and other sources. The different types of water supply proposed for a subdivision may include surface water, tributary groundwater, Denver Basin groundwater, and designated groundwater.

For example, if Denver Basin groundwater is proposed for the subdivision, the State Engineer will require a declaration of the specific aquifer intended for the subdivision, and a calculation of the amount of groundwater in storage underlying the develop-ment. It is important that the developer specifically determine how the Denver Basin aquifers will be utilized, because several counties have 300-year water supply requirements for all new developments utilizing these aquifers.

In 2001, 335 subdivisions were reviewed and commented on by the State Engineer, increasing to 425 reviews in 2002, and 348 reviews in 2003.

RECENT GROWTH AND WATER SUPPLY LEGISLATION

Exacerbated by drought and growth, critical shortfalls in water supply have prompted another spate of water-related legislation past in the last three years. Water supply shortfalls, if only for lim-

ited critical periods of time, often require water providers to pursue short and long-term exchanges, transfers, or leases of water rights.

Traditionally, changes of water rights were the purview of the water courts. However, it can often take from six months to two years to have these changes approved. Contested cases may take even longer.

To improve the flexibility and responsiveness of the state’s administration system to better address issues such as drought, growth, and concern for instream flows for fish and wildlife, in 2002, 2003, and 2004 the General Assembly adopted legislation authorizing the State Engineer to:

• Allow interruptible water supply agreements between water right owners and cities. The leases may operate no more than three out of ten years. Temporary changes in the point of diversion, location of use, and type of use for absolute water rights are allowed without the need for court approval (HB 03-1334, HB 04-1256).

• Allow farmers to loan all or part of their decreed water rights to another agricultural water right holder on the same stream system, or the Colorado Water Conservation Board for instream flows. The loan can operate for no more than 180 days, must be approved by the Division Engineer, and cannot cause injury to other water rights. (SB 04-032)

• Allow temporary changes of water rights and substitute supply plans for out-of-priority diversions while appli-cations for changes of water rights and augmentation plans are pending in Water Court (HB 02-1414, HB 03-1001)

• Establish water banks for stored water throughout the state (HB 03-1318)

• Give junior tributary wells in the South Platte Basin until December 31, 2005 to file their augmentation plan applications in Water Court. In the mean time, they are allowed to pump their wells if they have a substitute supply plan approved by the State Engineer (SB 03-073). ❑

Jim R

ichar

dson

A new subdivision presses up against farm fields in Brighton, Colorado. By law, all developers must show county officials that they have sufficient water sup-plies to meet the demands of whatever type of new construc-tion proposed.

HEADWATERS – SUMMER 2004 76 COLORADO FOUNDATION FOR WATER EDUCATION

WATER &G R O W T HIN COLORADO

ALTHOUGH CONVENTIONAL WISDOM HOLDS

THAT WATER AVAILABILITY CONTROLS

GROWTH, THAT NOTION IS SIMPLY NOT TRUE.

The demise of Two Forks Dam in 1990, designed to

meet metro Denver’s water needs this century, did not

slow growth. In fact, since 1990, the fastest growing

states (including Colorado) rank among the driest. This

apparent contradiction can exist because the western

system of water allocation—the prior appropriation

doctrine—rests on the premise that water can be moved

from where it is found to where it is needed.

Jim R

ichar

dson

(2)

Jim H

avey

By Peter Nichols

HEADWATERS – SUMMER 2004 98 COLORADO FOUNDATION FOR WATER EDUCATION

New Growth: Same Basic Water Supply

Colorado gained almost a million new residents from 1990 to 2000. The state demographer projects another 2.8 million new Coloradans by 2030. The majority—1.9 million—will reside in the urban Front Range (Colorado Springs to Fort Collins), where most of the state’s population already lives. Although the West Slope will grow faster than the Front Range, it will gain almost 250,000 new residents in the same period.

The Colorado Water Conservation Board’s Statewide Water Supply Investigation (SWSI) projects that new residents will require an additional 600,000 acre-feet of municipal water by 2030. The Front Range will need 75 percent of the total.

Yet meeting the water needs of population growth is not as simple as supplying additional water to Front Range municipali-ties. To satisfy growth, Colorado needs more water for drink-ing, more water for industrial and commercial uses, and more water for recreation—snow to ski, rivers to raft and kayak, and streams and lakes to fish and boat—not to mention water to grow the food we eat, and for aquatic ecosystems. Meeting future demands is further complicated by the fact that over 80 percent of current and future Coloradans live on the Front Range, while 86 percent of the state’s water originates elsewhere (primarily as snow on the West Slope).

Coloradans have historically met their municipal growth needs and solved the problems of uneven distribution of popu-lation and water by constructing new on-stream reservoirs and trans-mountain water diversions to the Front Range. Denver’s Dillon Reservoir exemplifies this approach, as does Colorado Springs’ and Aurora’s Homestake Reservoir.

Windy Gap—the last major trans-mountain project—came on line in 1985, 18 years after conception. Later proposals floundered under pressure from environmental interests and the communities that stood to lose their water. EPA vetoed Two Forks Reservoir in 1990. Opposition from watersheds where water supplies would originate, commonly referred to as “basins-of-origin,” defeated exports proposed by American Water Development, Inc. from the San Luis Valley in 1994, and by Arapahoe County from the Gunnison River in 1995, and again in 2000 in water court. Eagle County stopped the pro-posed Homestake II Reservoir using state-granted “1041” local land-use authority in the 1990s.

Beginning in the 1950s, Colorado also began to meet the demands of growth by reallocating agricultural water to munici-pal use. Irrigated acreage in the Arkansas River Basin declined from over 600,000 acres in 1950 to less than 435,000 acres today, a 28 percent loss in 50 years. A similar trend is evident in the Lower South Platte River Basin, where agricultural to munic-ipal water right changes totaled 653,000 acre-feet from 1979 through 1995. Municipal and industrial users now own over 90 percent of Twin Lakes Canal and Reservoir Company shares, and approximately 60 percent of Colorado-Big Thompson units, two of Colorado’s largest trans-mountain irrigation projects. These trends not only continue, they appear to be accelerating.

However, traditional approaches to supplying water for

growth often had unmitigated economic and environmental consequences. Transferring irrigation water to cities often led to dried up farms and ranches, weed and dust problems, and declining agricultural communities. Ordway, for example—a once-thriving agricultural center—is now more reminiscent of ghost towns after the gold rush.

Historic on-stream dams and trans-mountain diversions have also had mixed effects on tourism and recreation, an $8.5 bil-lion industry. The 2002 drought illustrates this. The Arkansas River normally hosts the most commercial rafting days in the nation, in excess of 250,000 rafting days per year. This fell by almost half during the low river flows of 2002. Simultaneously, commercial rafting days on the Colorado River grew 50 percent because senior downstream water rights supported by upstream storage kept the water flowing. Because popular recreational sites like Dillon, Ruedi, and Turquoise lakes exist in part to meet municipal water needs, they experience low water levels when exports to the Front Range are at their maximum. Although constructed as water supply reservoirs, the public is often both unaware and uninterested in this fact, and sees them primarily as recreational amenities.

Low flows can harm aquatic ecosystems as well. For example, popular fisheries on the South Platte, Arkansas, and Fryingpan experience diminished flows from municipal diversions to serve the Front Range, although these same rivers also benefit from water released from reservoirs constructed in part to meet municipal needs. A 2002 poll by the Colorado Water Trust of state and federal agencies and conservation organizations identi-fied several thousand miles of water-short streams in the state, nearly as many miles as are already protected by the Colorado Water Conservation Board’s instream flow program.

Historical Water Supply Solutions

As part of the Statewide Water Supply Initiative, the Colorado Water Conservation Board projected out to the year 2030 increases in municipal, commercial, and industrial water demand, as well as demand from users of private wells. Divided by water division, the percent increase appears in yellow above the estimated 2030 demand expressed in acre-feet (af).

Eric

Wun

row Co

urte

sy o

f the

Rus

s Jo

hnso

n Co

llect

ion,

Ster

ling,

Colo

rado

Rocky Mountain National Park

10 COLORADO FOUNDATION FOR WATER EDUCATION HEADWATERS – SUMMER 2004 11

Alternatives for the future can be seen in a number of innova-tive cooperative approaches, many of which have already been completed or are now under way.

NEW DEVELOPMENT

New cooperative water development projects, reservoir redevelopment, and storage reallocation can benefit the basins where water supplies would originate. Front Range providers are increasingly proposing such projects to avoid opposition. For example, Wolford Mountain Reservoir is a win-win project ben-efiting both sides of the Continental Divide. Funded by Denver Water, the Municipal Subdistrict of the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District, and the Colorado River District, this reservoir allows Denver, by exchange, to keep more water in Dillon Reservoir, provides water for the River District, and serves as mitigation for Northern’s Windy Gap Project.

Reallocation of existing storage space to different uses presents another alternative to new reservoirs. Clinton Gulch Reservoir, a former mining structure, is a cooperative project that now provides Summit and Grand counties with water for domestic use and snowmaking. The Colorado River District and Denver Water also benefit, helping Denver to capture more melt-ing snow in Dillon Reservoir and the River District to develop more water in western Colorado.

Redevelopment offers a similar alternative to new devel-opment. For example, Vail-area communities, Vail Resorts, Colorado Springs, Aurora and the Colorado River District rede-veloped an old mine tailings pond to create a new storage facility called Eagle Park.

Off-channel reservoirs provide another alternative to on-stream dams. For example, the Parker Water and Sanitation District plans to construct Reuter-Hess Reservoir, an off-chan-nel storage facility to serve the groundwater-dependent town of Parker in Douglas County.

Conjunctive use of groundwater and surface water offers many of the storage possibilities of new water development, with fewer environmental impacts. Conjunctive use involves taking excess surface water collected in wet years, and pumping it into ground-water aquifers for extraction as drought or need requires. The South Metro Water Supply Study, involving 11 Douglas County water suppliers, Denver Water, and the Colorado River District, is exploring a project that would provide new long-term supplies for groundwater-dependent Douglas County water agencies, using a

combination of existing Denver Water reservoirs, new storage in the South Platte Basin, and conjunctive use of groundwater.

REALLOCATION OF EXISTING SUPPLIES: FARMS TO CITIES

Agricultural to urban transfers will continue to supply at least a portion of the state’s future population growth for the simple reason that municipal water is worth 20 times as much as agri-cultural water, and there are fewer regulatory hurdles associated with such transfers. The long-term challenge for Colorado is to manage these transfers in a way that minimizes negative impacts and fosters healthy agricultural economies and communities.

However, the immediate challenge is to switch from perma-nent to temporary transfers in order to provide time to develop long-term solutions. Interruptible supply agreements (some-times called dry-year option agreements) allow municipalities to lease agricultural water for intermediate (up to ten year) terms, and to use that water in abnormally dry years.

For example, in the Lower Arkansas River Basin, Aurora recently leased up to 12,600 acre-feet of Rocky Ford Highline Canal water annually, potentially drying up some 8,200 acres (approximately 36 percent of the total acreage irrigated by the canal), and allowing the city to refill drought-depleted reser-voirs. Under the interruptible leasing approach, irrigators typi-cally receive a one time sign-up fee and an annual payment per share of water, which provides stable income for farm-related investments, purchases, and debt repayment. Interruptible leas-ing also allows farmers or ranchers to maintain water for irriga-tion in most years, avoiding permanent dry-up of lands.

Assuming that irrigators dry up their least productive acre-age, and more intensively farm their most productive land, this suggests it might be possible to transfer additional water from agricultural to municipal use, without a corresponding decrease in production. Although simpler with individual ditch compa-nies, the concept might also work for a pooling arrangement of several ditches on a long-term basis, with selective fallowing or dry-up of some lands. These agreements could provide an annu-al supply for municipal growth, or periodic supply for drought.

More than half of Colorado’s agricultural irrigation demand—some 2.0 million acre-feet—is in the South Platte and Arkansas River basins. Idling 15 percent of this acreage would supply nearly 300,000 acre-feet for Front Range municipal growth, roughly two-thirds of projected 2030 municipal and industrial demands. This illustrates the potential of agricultural to urban transfers to protect

Alternatives for the Future

and enhance long-term agriculture and rural communities, while contributing water to meet municipal growth.

WATER CONSERVATION AND EFFICIENCY Conservation strategies function in one of two ways: funda-

mentally reducing demand or stretching existing supplies. There are a variety of ways to accomplish this, including demand reduction, water reuse, re-operation of reservoir systems, and regional coordination.

Public values largely drive long-term demand. Water-depen-dent landscaping, including traditional grass, constitutes from a third to nearly two-thirds of Front Range municipal demand dur-ing the summer months. Changing values could reduce long-term demand and corresponding needs for additional water supply.

Reuse of trans-mountain return flows is another proven strategy. According to Colorado law, water imported into anoth-er river basin can be used and reused to extinction. Decades ago Colorado Springs pioneered a program that irrigates golf courses, cemeteries, public properties, and sports facilities with non-potable reused water. Aurora also has a reuse program, and, like Colorado Springs, plans expansion. Denver’s reuse project came on line in 2004.

Coordinated operation of existing storage facilities owned by different entities is another conservation strategy. So-called reservoir “reoperation” capitalizes on the increased flexibility available from operating several facilities as one to increase yields without building new structures. The potential of coordinated reservoir operations is evident from the 63,000 acre-feet deliv-ered to support endangered fish in the Grand Valley in 1999. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation is also examining the use of “excess” capacity in the Fryingpan-Arkansas Project to store water for Aurora and others.

Regional coordination and cooperation is another proven strategy to meet future growth demands. Windy Gap Project upstream of Kremmling, and the Windy Gap Firming Project, involving potential construction of a new off-channel reservoir, are examples of multi-purpose projects that will help supply 11 Front Range municipalities with up to 48,000 acre-feet of addi-tional water per year.

WATER FOR RECREATION AND THE ENVIRONMENT

More people means more demand not only for municipal water, but also for every use, including recreation and the envi-

ronment. The Colorado Water Conservation Board continues to appropriate water for instream flows to preserve the natural envi-ronment to a reasonable degree. Others, such as the Colorado Water Trust, donate water to the CWCB for this purpose. Owners of water rights can also loan water to the CWCB for instream flows. Communities are also appropriating in-channel diversions to meet recreational demands.

Cooperation is another proven approach. An annual inter-agency agreement between the Fryingpan-Arkansas agencies and the Colorado Division of Wildlife ensures up to 400 cfs for the Browns Canyon stretch of the Arkansas River. A long-term agreement between Denver Water and the Farmers Reservoir and Irrigation Company provides 150 cfs of water to the South Platte River through Denver. On a longer-term basis, Eagle Park Reservoir provides water for instream flows, in addition to water for headwaters communities and ski areas. These examples are especially significant because they involve municipal suppliers addressing recreational and environmental needs.

•••Growth and drought place Colorado at a crossroads. New on-

stream reservoirs, trans-mountain diversions, and transfers of water from agriculture are unlikely to meet the needs of Front Range growth due to opposition from basins where the water would origi-nate and concerns over diminishing supplies for their own domes-tic, agricultural, recreational, and aquatic ecosystem needs.

However, moderate changes in historical water supply prac-tices offer the possibility to better balance the environmental and social trade-offs required to support new growth. These strategies include small trans-mountain diversions that benefit both the basins-of-origin and the Front Range, reconceived agri-cultural to municipal transfers that provide water for growth and preserve water for irrigation, municipal demand reduction, more efficient use of existing water supply infrastructure, and projects that incorporate recreational and environmental flows. ❑

Editor’s Note: Peter Nichols currently practices law with the Denver firm of Trout, Witwer & Freeman P.C. He is the principal co-author of “Water and Growth in Colorado, A Review of Legal and Policy Issues” published by the Natural Resources Law Center, University of Colorado School of Law (2001), and other articles on water issues.

Whi

t Ri

char

dson

HEADWATERS – SUMMER 2004 1312 COLORADO FOUNDATION FOR WATER EDUCATION

REALLOCATIONLEASES HELP FARMS AND SUBURBS

WEATHER DROUGHTBy Dan MacArthur

The largest temporary water lease in Colorado history promises to benefit both rural and urban interests. As part of this innovative agreement, the City of Aurora will lease enough water to weather the drought. In the Lower Arkansas River Valley, lease revenues will help farmers survive lean times while retaining ownership of their water, as well as the option to keep some land in production.

As part of a $5.5 million, three-year deal inked in March of 2004,

Aurora can lease up to 12,600 acre-feet annually—close to four billion

gallons—of High Line Canal Company water. Paralleling the Arkansas

River for 87 miles through Otero County, the High Line is the second

longest canal in the state. With water rights dating back to 1861, the

canal also holds the third and fourth most senior rights on the river.

High Line superintendent Dan Henrichs says the three-year lease will potentially dry-up about 36 percent of the 22,500 acres irrigated by the canal. The rest will remain in full or partial produc-tion. In addition, farmers have the option of leasing all or part of their canal shares.

“It’s one of those things where the sun and moon and the stars lined up and everybody came away from the table with what they needed,” says Aurora Director of Utilities, Peter Binney.

Aurora Mayor Paul Tauer also praised the agreement that he says demonstrates how cities and agriculture can work together. “We all win—farmers, small communities in the Arkansas Valley and Aurora residents,” says Tauer.

High Line Canal President Stan Fedde expressed similar but more cautious optimism. “It will keep the water rights in the valley and some of the young guys on the land, which we need,” he says. “At least it keeps the wolves away…We’re getting a lot of pressure to sell and I’m against that,” adds Fedde, whose family has farmed near Fowler for more than a century. “I don’t want to lease either, but it’s a lot better than selling.”

Bringing together the details of the lease arrangement took more than two years. It required convincing state law-makers in 2003 to approve legislation allowing cities to negotiate short-term leases of water, rather than outright pur-chases. This was the first time the state had ever passed any water-lease legisla-tion of this kind according to Binney.

To make sure that other organizations involved in regional water management would not oppose the deal, in the fall of 2003 the interested parties sat down with the Southeastern Colorado Water Conservancy District to come to an agreement on the larger implications of the transfer.

The resulting agreement with Southeastern prohibited Aurora from purchasing or permanently transferring additional water out of the Arkansas Valley for 40 years. At the same time, it acknowledged Aurora’s right to lease a total of up to 145,200 acre-feet during that period. According to Binney, “What it did was put to rest 20 years of water wars. It was a very constructive agreement for all of us.” It also paved the way for the

finalization of the High Line lease. Leased water will be delivered

through exchange agreements with the Bureau of Reclamation and the city of Pueblo. It is held in Twin Lakes Reservoir, discharged to the Otero Pump Station, and then directed to the Spinney Mountain Reservoir.

Aurora leased water from 152 High Line shareholders, effectively taking some 8,200 acres out of production. Binney notes that double that number wanted to participate, but could not due to limits on how much water can be moved.

“These new guys (farmers) are really struggling,” canal company president Fedde concedes. While 87 percent of the share-holders voted for the bylaw changes neces-sary to permit the leases, he doubts interest would have been so great if crop prices were better. He believes that uncertainty combined with depressed crop prices made the lease attractive to farmers this year.

The city paid $5,280 a share, with individual payments ranging from $2,000 to $209,000. According to canal superin-tendent Henrichs, that is about triple the amount most farmers could have expected to net per acre in a good year.

And it’s also a fair deal for Aurora, according to Binney. Desperate to fill its reservoirs depleted by on-going drought, the city plans to finance the lease with a surcharge of 68 cents per 1,000 gallons of water used. Doug Kemper, Aurora’s man-ager of water resources, says they hope to negotiate additional leases with the High Line in the future as well.

Yet even with this new temporary addition to Aurora’s water portfolio, Binney is convinced that the drought outlook remains grim. With the High Line water increasing Aurora’s reservoir storage by perhaps 5 to 6 percent, Binney still estimates that this year reservoirs will fill to no more than 60 percent—the level above which mandatory watering restric-tions could be lifted.

Beyond all the contracts and agree-ments that bind and protect them, both camps concur that the temporary agree-ment also requires a leap of good faith somewhat akin to leasing a new car. They can kick the tires, but confidence will come only after seeing how it runs. But for now they’re content to at least be traveling together in a promising new direction. ❑

It will keep the waterrights in the valley andsomeof the youngguysontheland,whichweneed.

—StanFedde,President,HighLineCanal

“

”

It’s one of those thingswherethesunandmoonandthe stars linedupandevery-body came away from thetablewithwhattheyneeded.

—PeterBinney,AuroraDirectorofUtilities

“

”

Canal Superintendent, Don Henrichs (left) pulls debris away from the diversion structure which shuttles water from the Arkansas River into the 87 mile-long High Line Canal (above).

Mich

ael L

ewis

(3)

Bria

n G

adbe

ry

HEADWATERS – SUMMER 2004 1514 COLORADO FOUNDATION FOR WATER EDUCATION

Planning and permitting a reservoir is no small undertaking. There are years of engineering studies, environmental reviews, public comment, logistical and funding challenges. To complicate mat-ters further, imagine if you are one of the fastest growing counties in the nation relying totally on nonrenewable ground-water. For one Douglas County water provider, it was time to cobble together sources of water from every angle. The result will be a unique new reservoir called Reuter-Hess.

Located just southeast of Denver, Douglas County encompasses the towns of Castle Rock, Larkspur, Parker, and the City of Lone Tree. According to an April 2004 news release by the U.S. Census Bureau, Douglas County was the third fastest growing county in the United States between 2000 and 2003.

Unfortunately, the county also faces rapid depletion of its primary source of water for thirsty homes and businesses: groundwater. Most of county’s municipal water suppliers rely on high-volume wells located in the Dawson, Denver, Arapahoe, and Laramie-Fox Hills groundwater aqui-fers. Numerous other homeowners have

private wells that tap the same resource. The Parker Water and Sanitation

District (PSWSD) has provided water to the homes and businesses of Parker and the surrounding areas since 1962. Until now, it relied solely on groundwa-ter sources to deliver potable water for indoor and outdoor use by its more than 22,000 customers.

Reuter-Hess Reservoir will be the district’s first foray into storing water aboveground. Frank Jaeger, PWSD district manager, says that planning for Reuter-Hess began in 1985, when PWSD’s engineering consultants projected a 3,000 acre-foot shortfall based on growth levels projected in the city’s master plan.

Initially, the district looked to stretch existing supplies by employing water conservation and reuse methods, and pur-chasing additional undeveloped land so

that it could tap the groundwater below. It also implemented tiered pricing, where customers are charged increasingly higher rates for greater levels of water consump-tion. Over time, these methods resulted in a 40 percent reduction in residential water use. But it was not enough.

Initial studies investigated the feasibility of constructing a reser-voir in Castlewood Canyon located in Castlewood Canyon State Park. However, unable to acquire the land, the district had to look elsewhere for a potential dam site. Finally, in 1993 PSWD acquired rights to purchase the almost 2,500 acre Reuter-Hess site locat-ed about three miles southwest of Parker in Newlin Gulch. Preliminary studies began in 1996 for the geotechnical feasi-bility of the dam. Environmental impact assessments of the dam and reservoir area were initiated the next year.

It was not until late February 2004 that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers approved PWSD’s environmental impact statement, clearing the way for the dis-trict to begin construction of the 16,200 acre-foot Reuter-Hess Reservoir in the fall of this year. Final voter approval of the

NEW DEVELOPMENT REUTER-HESS RESERVOIR

By CFWE Staff

district’s use of water rates and tap fees from new homes and businesses to repay project bonds was received in May.

This $105 million reservoir will pro-vide terminal storage of reclaimed waste-water, storm runoff, and irrigation return flows. “Unlike traditional reservoirs like Dillon, where water is captured from stream flows and runoff, Reuter-Hess water will come from irrigation water returned to the system, from wastewa-ter treatment plant effluent, and storm runoff that flows down Cherry Creek and Newlin Gulch,” explains Jim Nikkel, PWSD district engineer. A 48 inch raw-water pipeline will transport this water to the reservoir.

First, the reservoir will store wastewa-ter using an “exchange” system whereby treated effluent from the PWSD wastewa-ter treatment plant is released into Cherry Creek. Then the water will be drawn back into the Parker system through shallow wells along the creek. PWSD currently releases about two million gallons per day from its wastewater treatment plant. According to Nikkel, two million gallons is enough to supply the entire Town of Parker with domestic water for one day.

In addition, these same shallow groundwater wells will also intercept irrigation return flows. In this context, return flows generally enter the shallow groundwater system as a result of water-ing of urban landscapes such as lawns or golf courses.

A certain amount of water will also be provided by diversions from Cherry Creek. However, the 1985 water rights owned by the district are so junior, they are available primarily during peaks in creek flows provided by storm events.

In addition, in a process known as conjunctive use, surplus or “carryover” water stored in the reservoir during off-peak months will be injected back into aquifers to help preserve and increase the groundwater supply.

Although the reservoir will engulf some 470 acres, the project will retain 2,000 acres of open space around the res-ervoir site. PWSD would also like to open up the reservoir and surrounding lands to recreation. However, it lacks the authority to operate recreation programs such as non-motorized boating or hiking trails.

“No one (from state or county parks departments) has yet approached us about

the recreational opportunities for the res-ervoir,” says Nikkel. “But when someone does approach us, we’ll be ready to plan and add the recreational components.”

It will take 40 years for PWSD to repay the Colorado Water and Power Development Authority for the loan to build Reuter-Hess. Nikkel says it will be repaid primarily through taxes and tap fees. This means that in order to make pay-ments, the district needs to sell some 600 taps per year, a level below or on par with previous tap sales over the last 15 years.

“Growth seems to happen whether or not we are water-rich,” says Nikkel. “Instead of stopping the growth, which we can’t do, we are being proactive and finding solutions.”

Construction of the reservoir is sched-uled to begin in the fall of 2004, and is expected to be ready to fill in 2007. But after spending 18 years to complete the Reuter-Hess project, Jaegar and his team are not slowing down to celebrate.

“We are always looking at what’s next,” says Jaegar. “We are trying to find solu-tions to how we can get more water, how we can expand the reservoir, what else we can do to ensure long-term supply.” ❑

private wells that tap the same resource.

Growthseemstohappenwhetherornotwearewater-rich.Insteadofstoppingthegrowth,whichwecan’tdo,weare

beingproactiveandfindingsolutions.

—JimNikkelPWSDDistrictEngineer

“”

Mich

ael L

ewis

(2)

Reuter-Hess Reservoir will inundate some 470 acres of Newlin Gulch, three miles south of the Town of Parker

HEADWATERS – SUMMER 2004 1716 COLORADO FOUNDATION FOR WATER EDUCATION

When Colorado entered its fifth year of drought in 2003, a small water district in Archuleta County decided to meet the challenge head on. Looking at alternatives for providing water to its growing population,the Pagosa Area Water and Sanitation District (PAWSD) launched its first water conservation program. Designed to reduce water demand and stretch existing supplies, the program incorporates education, restructured water-rates, advertising, rebates, and simple door-to-door outreach.

And when the first year results came in, the district was in for a pleasant surprise: residents of Pagosa Springs and its outlying communi-ties had reduced their water consumption by 17 percent.

Established in 1971, the Pagosa Area Water and Sanitation District provides water and wastewater services to a largely residential community within Archuleta County (popula-

tion 11,000) in southwest Colorado. Twenty-one full-time personnel man-age and operate approxi-mately 290 miles of water lines and 80 miles of sewer lines. Some 75 percent of the PAWSD customer base is residential, and more than 50 percent of the water they consume

(especially in the summer months) is used for outdoor irrigation.

Serving slightly more than 4,220 accounts today, total water demand within this district is some 538 million gallons. However, if projected growth rates continue, by 2040 the district estimates demand will rise to some 3,800 mil-lion gallons per year. With that sort of growth, PAWSD managers knew they would have to look at all alternatives and include conservation in their water supply planning.

In spring 2003, PAWSD named environ-mental consultant Denise Rue-Pastin as its first water conservation program director. With a background in environmental policy and analy-

CONSERVATIONPAGOSA SPRINGS GETS WATER WISE

By Christine Meyer

sis, she introduced PAWSD to the practice of “anticipatory public politics”—changing institutions and individual actions now to prevent anticipated crises in the future.

“The consensus was that we needed to get ahead of the growth curve as opposed to chasing the problem,” says PAWSD board president Karen Wessels. “This meant look-ing at time horizons of 20-40 years.”

One of PAWSD’s first educational events was a standing-room-only work-shop called “Responsible Landscaping.” The program discussed seven principles of Xeriscape landscaping to create low-water-use lawns and gardens. Techniques for improving soil and grouping plants according to water needs were among the recommended measures.

The district placed displays on water saving technologies at local home shows and county fairs. It also launched an annual, four-month “Professor Drip” advertising campaign, featuring a bespe-cled professor clad in a white lab coat. The character introduces new incentives and publicizes other water saving instruc-tions in newspaper and radio spots.

In June 2003, PAWSD discontinued its flat fee rate in favor of a increasing tiered rate structure based on individual use.

Conservation-oriented rates such as these reward customers for using less water.

Soon after, Rue-Pastin began to knock on doors and talk with customers about their concerns, issues, and needs for additional information. Establishing alli-ances with local trade groups--plumbers, plumbing equipment suppliers, nurseries, hardware stores--had an immediate payoff. Nursery representatives developed presen-tations for the landscaping workshop, and plumbers contributed practical input to the design of the toilet rebate program.

But a critical component of the dis-trict’s conservation program was to inte-grate educational and marketing activi-ties with community buy-in. In the fall, PAWSA, representatives from the town and county, and the local property own-ers association, convened the Archuleta County Water Wise Policy Task Force to develop a set of over-arching principles that could guide future conservation planning. The result was an unprecedent-ed “Joint Water Waste Proclamation.”

Published in the local paper and posted in the library and PAWSD office,the proclamation provided evidence of the commitment on the part of elected officials, businesses, and the community

to pursue water conservation measures. The latest in Pagosa’s portfolio of

conservation incentives is a toilet rebate program introduced in the summer of 2004. From June 1 through November 30, residents who retrofit or replace high volume toilets with more efficient models are credited $75-125 on their water bill.

It’s a win-win strategy, according to Rue-Pastin. “When you help your cus-tomers become more efficient, you help them save money. This money can be used for other purposes, which in turn gets recycled into the local economy.”

Looking to build on its first year suc-cesses, PAWSD is considering expanding its rebate program to include incentives for more efficient dish and clothes washers, and more information on the latest advances in irrigation system controls. In the commer-cial sector, PAWSD will begin to work with schools, hotels and other large commercial facilities, tying together efficient water use with reduced energy consumption.

“All our programs and community ini-tiatives work together to change patterns of water use—in times of drought or not,” says Rue-Pastin. “That’s the way it is in the 21st century, it’s all about efficiency.” ❑

When you help your customers become more efficient, you help them save money.— Denise Rue-Pastin,

PAWSD Water Conservation Director

“”

Char

les

Man

n

18 COLORADO FOUNDATION FOR WATER EDUCATION HEADWATERS – SUMMER 2004 19

Agricultural ditch and reservoir companies increasingly threatened by urban encroachment may find new direction by supplying water for a whole different crop of water users.

Soon, a pioneering program will take shape in Northern Colorado dem-onstrating how irrigation companies can adapt and prosper by providing water to both agricultural and residen-tial customers. Mutual irrigation companies are private, non-profit organizations formed to distribute water to their mem-ber owners. There are hundreds of these companies across the state that historically have supplied irrigation water for agricultural operations.

Dual-use—or secondary—systems will enable irrigation water providers to deliver untreated water for suburban gar-dens and green spaces by updating their existing canals and headgates to accommodate new residential irrigation systems.

“It’s a win-win for everybody. There’s no downside,” declares Stephen Smith, chairman and vice president of the Fort Collins-based Aqua Engineering Inc. A globally recog-nized authority on irrigation design, Smith is a clear advocate for putting traditional agricultural irrigation water delivery systems to dual purposes.

Don Magnuson, manager of the Lake Canal Company—a small agricultural water provider that serves the eastern edge of Fort Collins southeast to the burgeoning communities of Timnath and Windsor—also thought these systems might work in his area.

More than three years ago, Dr. John Wilkins-Wells, an assistant professor and senior research scientist at the Colorado State University Sociology Water Lab, began researching the application of dual-use systems in other western states. He sponsored workshops and hosted field trips to spread the word about the potential of these innovative systems. After one of those trips, Smith and Magnuson were hooked.

With the support of Lake Canal’s board of directors, they prepared a fea-sibility study evaluating the 7,000 acres served by the company. Although largely still an agricultural area, soon these same acres are slated to bear crops of thousands of new homes. A separate regional feasi-bility study was also completed in the fall of 2003 examining the success of dual-use supply systems in Utah and Idaho. It

concluded that these alternative systems could offer similar benefits in Colorado.

Work on the first prototype system is expected to begin no later than next year. It calls for installing a network of pipes, ponds and pumps necessary to transfer water out of the tra-ditional large uncovered canals, into the piped systems used to irrigate lawns and gardens. Estimated to cost up to $12 million, primary funding for the project will be provided by a loan from the Colorado Water Conservation Board. Intended strictly for landscape irrigation, the secondary system will be totally separate and distinct from the primary canal system, and will also be separate from the treated drinking water sys-tem provided by the local municipal water suppliers.

“We see a daisy chain of economic benefits,” says Wilkins-Wells, who served as principal investigator of the regional feasibility study.

First, dual-use systems reduce the costs of providing water to residential developments. Developers are required by law to provide sufficient water to meet the basic water needs of every new home. For developers in the Lake Canal service area that usually means one share of Colorado-Big Thompson (CB-T) water for each home. Each of those shares currently costs from $12,500 to $14,000. But with more than 50 percent of domes-tic water in the summer months typically consumed by land-scape irrigation, finding a cheaper source of irrigation water (such as that provided by a local ditch company) can reduce a developer’s water supply costs dramatically. Even after tak-

PROFILEMUTUAL IRRIGATION COMPANY

CATERS TO NEW CUSTOMERSBy Dan MacArthur

ing into account the added expense of constructing a dual-use system, developers can save $1,000 to $1,500 per home.

In addition, project proponents claim that by reducing demands for treated water, the limited amount of water avail-able in the CB-T system can go to additional uses. Homeowners also benefit from bargain-basement water prices—potentially keeping their yards green for less than $225 a year.

Farmers serve to benefit as well. “Infusions of cash from residential customers can help the irrigation company keep its annual [rates] for agricultural water to a minimum,” says Smith, “which can be quite helpful in keeping agriculture viable in this area.”

New income can also help irrigation companies finance sys-tem improvements, such as upgrades to delivery facilities, lining of canals, and pressurizing systems for easier deliveries.

“If one thinks about it, mutual company involvement makes a lot of sense” notes Wilkins-Wells. “The company rep-resents an established organization dedicated to the business of managing water rights, delivering water to users and main-taining a delivery infrastructure. The future can be bright for the ditch company with a simple repackaging of the irrigation company’s historic commodity.”❑

ing into account the added expense of constructing a dual-use

Just east of Fort Collins, irrigation company manager Don Magnuson (above) was faced with losing some of his agricultural customers to suburban growth. Teaming up with an inde-pendent irrigation consultant and a Colorado State University professor, and taking their cue from successful dual-use programs in Utah and Idaho, the Lake Canal will soon provide irriga-tion water to both farms and residential lawns.

Cynt

ia H

unte

r (3

)

Contact name:_____________________________________Company (if applicable):_________________________________________Address:_____________________________________________________________________________________________________Phone or email (in case there is a problem or delay fi lling your order):_____________________________________________________

Membership orders: How would you like this membership listed in our publications and annual membership reports?__ Under my name __ Under my company’s name __ Anonymous

__ Check enclosed __ Visa __ Mastercard __ Discover __ AmexCard number: ______________________________________________________ Expires: ____________________________________Name on card: ______________________________________________________ Signature: __________________________________

Item Quantity Member Price Price

Citizen’s Guide to Colorado Water Law: 2004 revised edition This booklet explores the basics of Colorado water law, how it has developed, and how it is applied today. Designed to be easy-to-read, yet comprehensive enough to serve as a valuable reference tool. Updated for 2004 with important changes based on new legislation in 2003. 33 pages, full color.

$7.20 each;$5.40 each if ordering 10

or more

$8 each;$6 each if

ordering 10 ormore

$Citizen’s Guide to Water Quality Protection This handy desk reference is designed for those who need to know more about Colorado’s complex regulatory system for protecting, maintaining, and restoring water quality. Wondering if your local creek is safe for fi shing or swimming? This guide can help you fi nd the answers. 33 pages, full color.

Citizen’s Guide to Colorado Water Conservation The latest in the Citizen’s Guide series looks at the current water conservation technologies, incentive programs, regulations and policies promoting effi cient water use in Colorado. Not a “how-to” book, but a reference for those who need a balanced overview of the opportunities and challenges for water conservation in Colorado today. 33 pages, full color.

Headwaters Magazine Our quarterly magazine features interviews, legal updates, and in-depth articles on fundamental water resource topics. Available by subscription or free with your membership, Headwa-ters keeps you up-to-date and informed about water resource concerns throughout the state.

FREE $25 annually $

Colorado: The Headwaters State Poster Recently updated, this colorful poster provides an overview of the major lakes, reservoirs and rivers in Colorado and describes how humans and the environment rely on these variable resources. 24”h x 36”w.

FREE (plus shipping)

Water History Poster An archeological and historical timeline of Colorado’s water resources and their development from circa 14,000 B.C. to the present. 36”h x 24”w. FREE (plus shipping)

Shipping & HandlingCITIZEN’S GUIDES $0-$48 = $2 • $48.01-$120 = $5.50 • $120.01-$210 = $9.00 • $210.01-$360 = $10.50 • Over $360 = $12.50

POSTERS 1-5 posters = $3.50. If ordering more than 5 posters please call us on 303-377-4433 for shipping charges.$

SUBTOTAL $

I / we would like to become a member at the ____________________________________ level as described above. $

TOTAL $

Charter member - $2,000 or more: Up to 10 FREE annual subscriptions to Headwaters magazine; FREE individual registration for tours and events; special recognition in CFWE events & publications

Pioneer member - $1,000 or more: Up to 7 FREE annual subscriptions to Headwaters magazine; 20% off registration for Foundation tours and events; FREE set of Citizen’s Guides, maps and posters

Sustaining member - $500: Up to 5 FREE annual subscriptions to Headwaters magazine; 20% off registration for Foundation tours and events

Associate member - $250: Up to 3 FREE annual subscriptions to Headwaters magazine; 10% off registration for Foundation tours and events

Individual member - $50 / Student member (current students only) - $25: FREE annual subscrip-tion to Headwaters magazine; 50% off all tours and events

BECOME A MEMBER

Mail with payment to CFWE, 1580 Logan Street, Suite 410, Denver, CO 80203, fax (303) 377-4360, or order online at www.cfwe.org

Support the Foundation’s efforts to provide balanced and accurate information on water resource issues. All members receive regular updates and notices on new Foundation products and events, discounts on all publications and event registrations, and FREE subscriptions to the quarterly Headwaters magazine.

Your membership contribution is tax-deductible, in accordance with state and federal laws.

Member Member Price

Non-Member Price TotalMember Non-Member

20 COLORADO FOUNDATION FOR WATER EDUCATION HEADWATERS – SUMMER 2004 21

Down from DenverDown to Kiowa CountyAnd into Kiowa country.Ancient cottonwoods, gnarled junipersPrairie grasses, sweet sageCover dry cracked plains.

Down 287, past Kit CarsonMist tah yeots: Mists of DeathVision of past.

Western winds whisper: Tsis Tsis Tas*Eroded sand dunesSad songs of past.

Venemous veho: Shi shi kneh woh eesLook! On ridge! Blue snake:Coiled for Attack!

White Antelope unfoldsWhite flag of surrender.History recoilsIn minds of visitors.

Frozen moon touchesSoul of The LandBloody rivers flowMisery at hand: Massacre.

White Antelope singsDeath Song: “Nothing Lives Long. Only earth, only mountains remain.”

Skulls stare skyward:Look! See! Seven Brothers!And beyond: Seyan!

Sun rises red.Mochi: tenacious si seyouts,Buffalo Calf Woman: Sings! Shouts!“I will be a warrior! And a warrior I will remain Forever”

Sweet MedicineA Collaborative Poem

Translation of Indian Words

mis tah yeots Mists of deathTsis Tsis Tas people who were precursors of the Cheyenneveho the white manshi shi kneh woh ees snake“Seven Brothers” the seven stars in the Big Dipperseyan the place of the deadsi yeouts spirits

Written by Luisa Romero and Students in Ethnic Literature Class Eleventh and Twelfth Grades. Teacher: Kathleen Kelleher, North High School, Denver, Colorado

First Place, Colorado River of Words 2004, High School Division

Editor’s Note: The 1845 map of John C. Fremont’s survey from Independence, Missouri to the Great Divide in Colorado shows the Front Range from Wyoming to New Mexico as being inhabited by the Sioux, Arapahoe, Cheyenne, Comanchee, and Kiowa Indians.

SUBMISSION GUIDELINESWe encourage submissions of original essays, non-fiction,

poetry and/or photographs for our Voices department. Headwaters magazine publishes one to two selections of creative work in each issue.

Voices is a forum for Coloradans to creatively express their relationship to our water resources. As a literary and artistic outlet, we are looking for well-crafted, and preferably unpublished work.

Literary submissions should not exceed 500-600 words. Longer pieces may be considered, but may require editing. Photo submissions need to include pertinent caption information.

Deadline: review on a continuing basis.Articles or digital photos may be submitted to

[email protected]. Print submissions should be mailed to:1580 Logan Street, Suite 410Denver, CO 80203

If desired, please enclose a self-addressed stamped envelope (SASE) with enough postage for us to return your materials to you.

The writer retains the copyright and, therefore, the right to resell or repackage the original manuscript to another party after publication in Headwaters magazine. The right to republish the edited manuscript in a subsequent anthology or on the Colorado Foundation for Water Education website is retained by Colorado Foundation for Water Education.

With photographs, CFWE exercises “one-time” or “first serial” rights, both of which include the right to reprint the photo (as originally used) for marketing and promotional purposes, such as ads or on the Colorado Foundation for Water Education website.

Emm

ett

Jord

an

1580 Logan St., Suite 410Denver, Colorado 80203303-377-4433 • www.cfwe.org

NONPROFIT ORGU.S. POSTAGE

PAIDDENVER, CO

PERMIT NO 178

Green River, Dinosaur National Monument.

Photo by Eric Wunrow

NONPROFIT ORGU.S. POSTAGE

PAIDDENVER, CO

PERMIT NO 178