Graham, Stephen. "Cities as battlespace: the new military urbanism." City 13.4 (2009): 383-402.

-

Upload

stephen-graham -

Category

News & Politics

-

view

1.177 -

download

4

description

Transcript of Graham, Stephen. "Cities as battlespace: the new military urbanism." City 13.4 (2009): 383-402.

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

!"#$%&'(#)*+%,&$%-.,/*.&-+-%012%34,+($%5./(+/(%6#$('#07(#./89/2%:;%<&/7&'1%=>:>?))+$$%-+(&#*$2%?))+$$%6+(&#*$2%3$70$)'#@(#./%/7A0+'%B:==C>=DE8F70*#$"+'%G.7(*+-H+I/J.'A&%K(-%G+H#$(+'+-%#/%L/H*&/-%&/-%M&*+$%G+H#$(+'+-%N7A0+'2%:>E=BO;%G+H#$(+'+-%.JJ#)+2%P.'(#A+'%Q.7$+R%DES;:%P.'(#A+'%4('++(R%K./-./%M:!%D<QR%TU

5#(1F70*#)&(#./%-+(&#*$R%#/)*7-#/H%#/$('7)(#./$%J.'%&7(".'$%&/-%$70$)'#@(#./%#/J.'A&(#./2"((@2VV,,,W#/J.'A&,.'*-W).AV$A@@V(#(*+X)./(+/(Y(E:D;:>OE>

5#(#+$%&$%Z&((*+$@&)+2%!"+%N+,%P#*#(&'1%T'0&/#$A4(+@"+/%['&"&A

9/*#/+%@70*#)&(#./%-&(+2%:>%6+)+A0+'%=>>B

!.%)#(+%("#$%?'(#)*+%['&"&AR%4(+@"+/\=>>B]%^5#(#+$%&$%Z&((*+$@&)+2%!"+%N+,%P#*#(&'1%T'0&/#$A^R%5#(1R%:D2%;R%DCD%_%;>=!.%*#/`%(.%("#$%?'(#)*+2%69I2%:>W:>C>V:Da>;C:>B>D=BC;=OTGK2%"((@2VV-bW-.#W.'HV:>W:>C>V:Da>;C:>B>D=BC;=O

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf

This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial orsystematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply ordistribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contentswill be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug dosesshould be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss,actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directlyor indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Cities as battlespace (above)Transparent cities (below)

Downloaded By: [Swets Content Distribution] At: 13:55 14 January 2010

CITY, VOL. 13, NO. 4, DECEMBER 2009

ISSN 1360-4813 print/ISSN 1470-3629 online/09/040383-20 © 2009 Taylor & FrancisDOI: 10.1080/13604810903298425

Cities as battlespaceThe new military urbanism

Stephen GrahamTaylor and Francis

The latest in an ongoing series of papers on the links between militarism and urbanismpublished in City, this paper opens with an exploration of the emerging crossovers betweenthe ‘targeting’ of everyday life in so-called ‘smart’ border and ‘homeland security’programmes and related efforts to delegate the sovereign power to deploy lethal force toincreasingly robotized and automated war machines. Arguing that both cases representexamples of a new military urbanism, the rest of the paper develops a thesis outlining thescope and power of contemporary interpenetrations between urbanism and militarism. Thenew military urbanism is defined as encompassing a complex set of rapidly evolving ideas,doctrines, practices, norms, techniques and popular cultural arenas through which theeveryday spaces, sites and infrastructures of cities—along with their civilian populations—are now rendered as the main targets and threats within a limitless ‘battlespace’. The newmilitary urbanism, it is argued, rests on five related pillars; these are explored in turn.Included here are the normalization of militarized practices of tracking and targetingeveryday urban circulations; the two-way movement of political, juridical and technologi-cal techniques between ‘homeland’ cities and cities on colonial frontiers; the rapid growth ofsprawling, transnational industrial complexes fusing military and security companies withtechnology, surveillance and entertainment ones; the deployment of political violenceagainst and through everyday urban infrastructure by both states and non-state fighters;and the increasingly seamless fusing of militarized veins of popular, urban and materialculture. The paper finishes by discussing the new political imaginations demanded by thenew military urbanism.

Key words: military urbanism; militarisation; security; battlespace; surveillance; war

Target intercept …

n 14 November 2007, JacquiSmith, then the UK’s HomeSecretary, announced one of the

most ambitious attempts by any statein history to systematically track andsurveil all persons entering or leaving itsborders. Using technology developed bythe ‘Trusted Borders’ consortium led by

the massive Raytheon defense corporation,the UK’s highly controversial ‘E-borders’programme will deploy sophisticatedcomputer algorithms and data miningtechniques, along with biometric scanning,to continually try to identify ‘illegal’ orthreatening people or behaviours beforethey threaten the UK’s territorial limits.

The E-borders project is based on adream of technological omniscience: of

O

Downloaded By: [Swets Content Distribution] At: 13:55 14 January 2010

GRAHAM: CITIES AS BATTLESPACE 385

tracking all the flows of people that crossthe UK’s borders whilst using databases ofpast activities and associations to identifyfuture threats before they materialize.When the system is supposed to be fullyestablished in 2014—although many arguethat its simple unworkability will lead toinevitable delays—Smith promises thatcontrol and security will be reinstated forthe UK in a radically mobile and insecureworld. ‘All travellers to Britain will bescreened against no fly lists and intercepttarget lists’, she predicts. ‘Together withbiometric visas, this will help keep troubleaway from our shores … As well as thetougher double check at the border, IDcards for foreign nationals will soon give usa triple check in country’ (Kobe, 2007).

(In a rich irony, another surveillancesystem—Internet viewing bills—almostforced Smith to resign in late March 2009,when it was discovered that she tried to claimfor the costs of her husband’s pornographicviewing habits as parliamentary expenses.Eventually, she did resign on 2 June 2009after further controversy surrounding herexpenses claims.)

Smith’s language here—‘target lists’,‘screening’, ‘biometric visas’ and so on—reveals a great deal. For projects like theUK’s E-borders programme representattempts to push forward a startling militari-zation of civil society. They rest on theextension of military ideas of tracking, iden-tification and targeting into the quotidianspaces and circulations of everyday life.

Indeed, as attempts to ‘fix’ identity tobiometric scans of people’s bodies, to usecomputers to pick out dangerous peoplefrom the mass and flux of the backgroundcity, and to link databases of past activity tocontinuously ‘target’ the immediate future,projects like the UK’s E-borders programmeare best understood not merely as stateresponses to changing security threats.Rather, they represent dramatic translationsof long-standing military dreams of high-techand technophiliac omniscience and rational-ity into the governance of urban civil society.

With both security and military doctrinewithin Western states now centring on thetask of identifying insurgents, terrorists ormalign threats from the chaotic backgroundof urban life, this point becomes clearer still.As I have argued previously in the pages ofCity (Graham, 2008), whether in the queuesof Heathrow, the tube stations of Londonor the streets of Kabul and Baghdad, thislatest doctrine stresses that means must befound of automatically identifying andtargeting threatening people and circulationsin advance of their materialization, whenthey are effectively indistinguishable fromthe wider urban crowd. Hence the paralleldrive in cities within both the capitalist heart-lands of the Global North, and the world’scolonial peripheries and frontiers, to estab-lish high-tech surveillance systems which‘mine’ data accumulated about the past tocontinually identify insurgent or terroristactions in the near future.

Armed vision: ‘their sons against our silicon’

At the root of such imaginations of war andsecurity in the post-cold war world are tech-nophiliac fantasies where the West harnessesits unassailable high-tech power to reinstateits waning influence in a rapidly urbanizingand intensely mobile world. ‘At home andabroad,’ wrote US security theorists MarkMills and Peter Huber in the right-wing CityJournal in 2002, a year after the 9/11 attacks,‘it will end up as their sons against our silicon.Our silicon will win.’ Mills and Huber (2002)envisage a near future straight out of MinorityReport. In their vision, a whole suite ofsurveillance and tracking systems develop onthe back of high-tech systems of consump-tion, communication and transportation topermeate every aspect of life in Western orUS cities. Continually comparing currentbehaviour with vast databases recording pastevents and associations, these, the argumentgoes, will automatically signal when the city’sbodies, spaces and infrastructure systems are

Downloaded By: [Swets Content Distribution] At: 13:55 14 January 2010

386 CITY VOL. 13, NO. 4

about to be turned into terrorist threatsagainst it. Thus, what Mills and Huber call‘trustworthy’ or ‘cooperative targets’ arecontinually separated from ‘non-cooperators’characterized by their efforts to use postal,electricity, Internet, finance, airline and trans-port systems as means to project resistanceand violence. In effect, Mills and Huber’svision calls for an extension of airport-stylesecurity and surveillance systems to encom-pass entire cities and societies using the high-tech systems of consumption and mobilitythat are already established in Western citiesas a basis.

In resistant colonial frontiers, meanwhile,Mills and Huber dream of continuous, auto-mated and robotized counterinsurgencywarfare. Using systems similar to thosedeployed in US cities, but this time delegatedwith the sovereign power to kill automati-cally, they imagine that US troops might beremoved from the dirty job of fighting andkilling on the ground in dense cities. Swarmsof tiny, armed drones, equipped withadvanced sensors and communicating witheach other, will thus be deployed to perma-nently loiter above streets, deserts and high-ways. Automatically identifying insurgentbehaviour, Mills and Huber dream of afuture where such swarms of roboticwarriors work to continually ‘projectdestructive power precisely, judiciously, andfrom a safe distance—week after week, yearafter year, for as long as may be necessary’(2002).

Such two-sided dreams of high-techomnipotence remain much more than sci-fifantasy, however. As well as constructing theUK’s E-borders programme, for example,Raytheon are also the leading manufacturerof both cruise missiles and the unmanneddrones used regularly by the CIA to launchassassination raids—and kill large numbersof innocent bystanders—across the MiddleEast and Pakistan since 2002. Crucially,Raytheon are also at the heart of a range ofvery real US military projects designed touse similar kinds of anticipatory targetingsoftware to allow robotic weapons systems

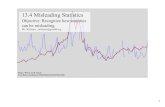

to automatically ‘target’ and kill their foeswithout any human involvement whatsoever(Figure 1).Figure 1 Two images reflecting the centrality of ‘armed vision’ to the new military urbanism. Top is the US Department of Defense’s vision of ‘identity dominance’ through the continuous ‘fusion’ of a whole series of biometric databases.As with the UK’s E-borders project, the technophiliac fantasy here is of omniscient control based on linking past associations and predictions of future risks, permanently targeting everyday urban circulations around the world in the process.Such a vision blurs worryingly with techniques of deploying lethal force against distant targets through armed drones controlled from video-game-like controls located on distant continents (bottom). Here air force ‘pilots’ are controlling anarmed Predator drone used to undertake targeted assassination raids within Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan, operating from within the inside of a ‘virtual reality cave’ at Nellis Air Force Base on the edge of Las Vegas. Major developmentefforts are underway to remove the pilot altogether, allowing such drones to automatically deploy their missiles against targets identified by their own software using target databases similar to those underpinning smart border projects. Sources:(Top) John D. Woodward, Jr., Director, ‘Using Biometrics in the Global War on Terrorism’, Department of Defense, Biometrics Management Office, West Virginia University, Biometric Studies Program, 7 April 2005 (US military: publicdomain). (Bottom) http://www.163rw.ang.af.mil/shared/media/photodb/photos/090402-F-8801D-002.jpg (US military: public domain).Thus, whether they involve automatedpolicing of no fly lists, or the delegation ofthe sovereign power to kill, software algo-rithms must now be seen as a broad contin-uum of linked techniques. These use historicaccumulations of data to make judgmentsabout future potentialities as a means ofpermanently deploying continuous contem-porary violence against the everyday sitesand circulations of the city (Amoore, 2009).Media theorist Jordan Crandall (1999) hascalled this the formation of a constellation ofwhat he calls ‘armed vision’. The key ques-tion now, he suggests, is ‘how targets areidentified and distinguished from non-targets’ within ‘decision making and killing’.

Crandall (1999) points out that the wide-spread integration of computerized trackingwith databases of ‘targets’ represents littlebut of ‘a gradual colonization of the now, anow always slightly ahead of itself’. This shiftrepresents a process of profound militariza-tion because the social identification ofpeople or circulations within civilian lawenforcement is complemented or evenreplaced by the machinic seeing of ‘targets’.‘While civilian images are embedded inprocesses of identification based on reflec-tion,’ Crandall writes, ‘militarised perspec-tives collapse identification processes into“Id-ing”—one-way channel of identificationin which a conduit, a database, and a bodyare aligned and calibrated.’

The new military urbanism

Such crossovers between high-technologyfor civilian borders, and high-technology formilitary killing, between the ‘targeting’ ofeveryday life in Western cities and thosecaught in the cross-hairs of aggressive colo-nial and resource wars, are at the heart of amuch broader set of trends which I label thenew military urbanism (Graham, 2010). Ofcourse the results of the targeting practices in

Downloaded By: [Swets Content Distribution] At: 13:55 14 January 2010

GRAHAM: CITIES AS BATTLESPACE 387

Figure 1 Two images reflecting the centrality of ‘armed vision’ to the new military urbanism. Top is the US Department of Defense’s vision of ‘identity dominance’ through the continuous ‘fusion’ of a whole series of biometric databases. As with the UK’s E-borders project, the technophiliac fantasy here is of omniscient control based on linking past associations and predictions of future risks, permanently targeting everyday urban circulations around the world in the process. Such a vision blurs worryingly with techniques of deploying lethal force against distant targets through armed drones controlled from video-game-like controls located on distant continents (bottom). Here air force ‘pilots’ are controlling an armed Predator drone used to undertake targeted assassination raids within Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan, operating from within the inside of a ‘virtual reality cave’ at Nellis Air Force Base on the edge of Las Vegas. Major development efforts are underway to remove the pilot altogether, allowing such drones to automatically deploy their missiles against targets identified by their own software using target databases similar to those underpinning smart border projects. Sources: (Top) John D. Woodward, Jr., Director, ‘Using Biometrics in the Global War on Terrorism’, Department of Defense, Biometrics Management Office, West Virginia University, Biometric Studies Program, 7 April 2005 (US mili-tary: public domain). (Bottom) http://www.163rw.ang.af.mil/shared/media/photodb/photos/090402-F-8801D-002.jpg (US military: public domain).

Downloaded By: [Swets Content Distribution] At: 13:55 14 January 2010

388 CITY VOL. 13, NO. 4

both cases—the hand on the shoulder in theairport queue or the alleged Taliban base leftin smouldering ruins—are very different.But, crucially, both represent acts of violencewhich rest at either end of a continuum basedon the core ideas driving the new militaryurbanism. These are based on the triumph ofhighly profitable, militarized solutions, basedon technophiliac dreams of high-tech target-ing and the linkage of surveillance databasesto the automatic identification of future‘targets’, to address pressing questions ofboth security and war in rapidly urbanizing,globalized societies.

As I have suggested before in my recentpapers for City on the deepening connectionsbetween militarism and urbanism, the newmilitary urbanism encompasses a complex setof rapidly evolving ideas, doctrines, practices,norms, techniques and popular cultural arenas(Graham, 2005, 2006, 2008). Through thesethe everyday spaces, sites and infrastructuresof cities—along with their civilian popula-tions—are now rendered as the main targetsand threats. It is manifest in the widespreadmetaphorization of war as the perpetual andboundless condition of urban societies—against drugs, against crime, against terror,against insecurity itself. It involves thestealthy militarization of a wide range ofpolicy debates, urban landscapes and circuitsof urban infrastructure, as well as realms ofpopular and urban culture. And it is leading tothe creeping and insidious diffusion of milita-rized debates about ‘security’ into every walkof life. Together, these work to bring essen-tially military ideas of the prosecution of, andpreparation for, warfare into the heart ofeveryday urban life.

The new military urbanism represents aninsidious militarization of urban life at a timewhen our planet is urbanizing faster thanever before. This process gains its powerfrom multiple circuits of militarization andsecuritization which are rarely consideredtogether or viewed as a whole. To understandits breadth, as well as its insidious power, it isnecessary to look at the new military urban-ism’s five constituent pillars in a little more

detail. In what follows, I explore each ofthese in turn.

Urbanizing security

‘The truth of the continual targeting of the world, as the fundamental form of knowledge production, is xenophobia, the inability to handle the otherness of the other beyond the orbit that is the bomber’s own visual path. Every effort needs to be made to sustain and secure this orbit—that is, by keeping the place of the other-as-target always filled.’ (Chow, 2006, p. 42)

Taking the high-tech surveillance and target-ing point first, it is important to stress at theoutset that, as with Mills and Huber’s visionjust noted, the new military urbanism restson a central idea: that essentially militarizedpractices of tracking and targeting mustperpetually colonize the geographies of citiesand the spaces of everyday life in both the‘homelands’ of the metropoles of the Westand the various neo-colonial frontiers andperipheries around the world. To the latestsecurity and military gurus, this imperative isdeemed to be the only adequate means toaddress the new realities of what they call‘asymmetric’ or ‘irregular war’.

Dominating political violence in the post-cold war, such wars pitch non-state terroristsor insurgents against high-tech security, mili-tary and intelligence forces of nation-states.Non-uniformed and largely indistinguish-able from the mass of the city, such non-stateactors, moreover, lurk invisibly within thecamouflage, density and anonymity offeredby the world’s burgeoning cities (especiallythe fast-growing informal districts). Theyalso both exploit and target the spirallingflows and circulations which link citiestogether: the Internet, You Tube videos,mobile phones, air travel, global tourism,international migration, port systems, globalfinancial flows, even postal and powersystems.

Recent terrorist outrages in New York,Washington, Madrid or London and Mumbai

Downloaded By: [Swets Content Distribution] At: 13:55 14 January 2010

GRAHAM: CITIES AS BATTLESPACE 389

(to name but a few), along with state militaryassaults on the urban sites of Baghdad, Gaza,Nablus, Beirut, Groznyy, Mogadishu andSouth Ossetia, demonstrate that asymmetricwarfare and political violence now takes placeacross transnational spaces while at the sametime telescoping through the streets, spacesand infrastructures of a rapidly urbanizingworld. Increasingly, the world’s main battle-grounds are thus profoundly urban, architec-tural and infrastructural spaces. More andmore, contemporary warfare takes place insupermarkets, tower blocks, subway tunnelsand industrial districts rather than openfields, jungles or deserts.

All this means that, arguably for the firsttime since the Middle Ages, the localizedgeographies of cities and the systems thatlink them together are starting to dominatediscussions surrounding war, geopolitics andsecurity. In the new military doctrine ofasymmetric war—also labelled ‘low intensityconflict’, ‘netwar’, the ‘long war’ or ‘fourthgeneration war’—the prosaic and everydaysites, circulations and spaces of the city arebecoming the main ‘battlespace’ (Blackmore,2005) both at home and abroad.

The ‘battlespace’ concept, indeed, is pivotalto the new military urbanism because it basi-cally sustains ‘a conception of military mattersthat includes absolutely everything’ (Agre,2001). As distinct from geographically andtemporally limited notions of war like ‘battle-field’, the battlespace concept prefiguresa boundless and unending process of milita-rization where everything becomes a site ofpermanent war. Nothing lies outsidebattlespace, temporally or geographically.Battlespace has no front and no back andno start or end. It is ‘deep, high, wide, andsimultaneous: there is no longer a front or arear’ (Blackmore, 2005, p. 34). The concept ofbattlespace thus permeates everything fromthe molecular scales of genetic engineering andnanotechnology through the everyday sites,spaces and experiences of city life, to the plan-etary spheres of space or the Internet’s globe-straddling ‘cyberspace’.1 The concept—whichis at the heart of all contemporary efforts to

urbanize military and security doctrine—thusworks by collapsing conventional military–civilian binaries. It stresses the way in whicheveryday urban sites and circulations contin-ually telescope local into global. And itsustains an urbanization of military and secu-rity doctrine as cities and urban sites are prob-lematized as key strategic sites whose density,clutter, unpredictability and vulnerabilityrequire new security lock-downs and radi-cally new military paradigms.

In such a context, Western security andmilitary doctrine is being rapidly reimaginedin ways that dramatically blur legal and oper-ational separations between policing, intelli-gence and military force; distinctionsbetween war and peace; and those betweenlocal and global scales. State power centresmore and more on efforts to try and separatemobilities and bodies deemed malign andthreatening from those deemed valuable andthreatened within the everyday spaces ofcities. Instead of legal or human rights andlegal systems based on universal citizenship,these emerging security politics are based onthe use of the latest identification, surveil-lance, tracking and database technologies topre-emptively profile individuals, places andgroups. Such practices place them withinvarious risk classes based on anticipations oftheir likelihood to resist or commit violence,disruption or resistance.

This shift threatens to re-engineer ideas ofcitizenship and borders that have been at theheart of the concept of the Western nation-state since the mid-17th century. An increas-ing obsession with pre-emptive riskprofiling, for example, threatens to use theaccoutrements of national security states toeffectively differentiate always fragile ideas ofuniversal national citizenship. In otherwords, different pre-emptive risk profiles,embedded within emerging national ID cardsystems, and based on surveillance of pastassociations, threaten to translate into variedpolitical entitlements within the body ofnational citizenry as populations are mappedfor propensities to harbour threats. As anexample, the USA is already pressuring the

Downloaded By: [Swets Content Distribution] At: 13:55 14 January 2010

390 CITY VOL. 13, NO. 4

UK to bring in a visa system only for UKcitizens who want to visit the USA who haveclose links to Pakistan. In other words, suchdevelopments threaten to establish borderingpractices—the definition of the geographicaland social ‘insides’ and ‘outsides’ of politicalcommunities—within the spaces of nation-states. This process parallels, in turn, theeruption of national border points within theterritorial limits of nations at airports andfast rail stations.

Meanwhile, the policing, security andintelligence powers of nations are also reach-ing out beyond national territorial limits asglobal surveillance systems are built tofollow the geographies of the world’s airline,port, trade and communications systems—anattempt to give early warning of malignurban circulations or insurgent attacks beforethey reach the strategic heartlands of West-ern global cities. National E-borderprogrammes, for example—like the one inthe UK—are being integrated into transna-tional systems so that passengers’ behaviourand associations can be data-mined beforethey attempt to board planes bound forEurope and the USA. Policing practices arealso extending beyond the borders of nation-states. The New York Police Department,for example, has recently established a chainof 10 overseas offices as part of its burgeon-ing anti-terror efforts. Extra-national polic-ing is also proliferating around majorpolitical summits or sporting events.

Such extensions of policing powersbeyond national borders are occurring just asmilitary forces are deploying much moreregularly within Western nations. The USArecently established a military command forNorth America for the first time: the North-ern Command.2 Previously, this was the onlypart of the world not so covered. The USGovernment has also gradually reduced long-standing legal barriers to military deploy-ment within US cities. ‘Urban warfare’training exercises thus now regularly takeplace in US cities, geared towards simulationsof ‘homeland security’ crises as well as thechallenges of pacifying insurgencies in the

cities of colonial peripheries in the GlobalSouth. In addition, in a dramatic convergenceof doctrine, high-tech satellites and droneshoned to surveil far-off cold war or insurgentenemies are increasingly being applied withinthe cities of Western nations.

Foucault’s boomerang

‘War has […] re-invaded human society in a more complex, more extensive, more concealed, and more subtle manner.’ (Qiao and Wang, 2002, p. 2)

The new military urbanism’s second keypillar involves the generalization of experi-ments with new styles of targeting and tech-nology in colonial war zones like Gaza orBaghdad, or security operations surroundingmajor sporting events or political summits, assecurity exemplars to be sold on through theworld’s burgeoning ‘homeland security’markets. Through such processes of imita-tion, explicitly colonial models of pacifica-tion, militarization and control, honed on thestreets of Global South cities, increasinglydiffuse to the cities of capitalist heartlands inthe Global North.

International studies scholar LorenzoVeracini (2005) has diagnosed a dramaticcontemporary resurgence in the importationof typically colonial tropes and techniquesinto the management and development ofcities in the metropolitan cores of Europeand North America. Such a process, heargues, is working to gradually unravel a‘classic and long lasting distinction betweenan outer face and an inner face of the colonialcondition’.

It is important to stress, then, that theresurgence of explicitly colonial strategiesand techniques amongst nation-states such asthe USA, UK and Israel in the contemporaryperiod3 involves not just the deployment ofthe techniques of the new military urbanismin foreign war zones but their diffusionand imitation through the securitization ofWestern urban life. As in the 19th century,

Downloaded By: [Swets Content Distribution] At: 13:55 14 January 2010

GRAHAM: CITIES AS BATTLESPACE 391

when European colonial nations importedfingerprinting, panoptic prisons and Hauss-mannian boulevard building through neigh-bourhoods of insurrection to domestic citiesafter first experimenting with them on colo-nized frontiers, colonial techniques todayoperate through what Michel Foucault(2003) termed colonial ‘boomerang effects’.4

‘It should never be forgotten’, Foucault(2003, p. 103) argued:

‘that while colonization, with its techniques and its political and juridical weapons, obviously transported European models to other continents, it also had a considerable boomerang effect on the mechanisms of power in the West, and on the apparatuses, institutions, and techniques of power. A whole series of colonial models was brought back to the West, and the result was that the West could practice something resembling colonization, or an internal colonialism, on itself.’

In the contemporary period, the militaryurbanism is marked by—and indeed, consti-tuted through—a myriad of increasingly star-tling Foucauldian boomerang effects. Forexample, Israeli drones designed to verticallysubjugate and target Palestinians are nowroutinely deployed by police forces in NorthAmerica, Europe and East Asia. Private oper-ators of US ‘supermax’ prisons are heavilyinvolved in running the global archipelagoorganizing incarceration and torture that hasbourgeoned since the start of the ‘war onterror’. Private military corporations heavilycolonize ‘reconstruction’ contracts in bothIraq and New Orleans. Israeli expertise inpopulation control is regularly sought bythose planning security operations for majorsummits and sporting events. And ‘shoot tokill’ policies developed to confront risks ofsuicide bombing in Tel Aviv and Haifa havebeen adopted by police forces in Westerncities (a process which directly led to the statekilling of Jean Charles de Menezes byLondon anti-terrorist police on 22 July 2005).

Meanwhile, aggressive and militarizedpolicing against public demonstrations and

social mobilizations in London, Toronto,Paris or New York now utilize the same‘non-lethal weapons’ as Israel’s army in Gazaor Jenin. Constructions of ‘security zones’around the strategic financial cores ofLondon and New York echo the techniquesused in Baghdad’s Green Zone. And many ofthe techniques used to fortify enclaves inBaghdad or the West Bank are being soldaround the world as leading-edge and‘combat-proven’ ‘security solutions’ bycorporate coalitions linking Israeli, US andother companies and states.

Crucially, such boomerang effects linkingsecurity and military doctrine in the cities ofthe West with those on colonial peripheriesare backed up by the cultural geographieswhich underpin the political right and far-right, along with hawkish commentatorswithin Western militaries themselves. Thesetend to deem cities per se to be intrinsicallyproblematic spaces—the main sites concen-trating acts of subversion, resistance, mobili-zation, dissent and protest challengingnational security states.

Bastions of ethno-nationalist politics, theburgeoning movements of the far right, oftenheavily represented within policing and statemilitaries, tend to see rural or exurban areasas the authentic and pure spaces of whitenationalism linked to Christian traditions.Examples here range from US ChristianFundamentalists, through the BritishNational Party to Austria’s Freedom Party,the French National Front and Italy’s ForzaItalia. The fast-growing and sprawlingcosmopolitan neighbourhoods of the West’scities, meanwhile, are often cast by suchgroups in the same Orientalist terms as themega-cities of the Global South, as placesradically external to the vulnerable nation—threatening or enemy territories every bit asforeign as Baghdad or Gaza.

Paradoxically, the imaginations of geogra-phy which underpin the new military urban-ism tend to treat colonial frontiers andWestern ‘homelands’ as fundamentally sepa-rate domains—clashes of civilizations inSamuel Huntington’s incendiary proposition

Downloaded By: [Swets Content Distribution] At: 13:55 14 January 2010

392 CITY VOL. 13, NO. 4

(1998)—even as the security, military andintelligence doctrine addressing both increas-ingly fuses. Such imaginations of geographywork to deny the ways in which the cities inboth domains are increasingly linked bymigration and investment flows to constituteeach other.

In rendering all mixed-up cities as prob-lematic spaces beyond the rural or exurbanheartlands of authentic national communi-ties, telling movements in representations ofcities occur between colonial peripheries andcapitalist heartlands. The construction ofsectarian enclaves modelled on Israeli prac-tice by US forces in Baghdad from 2003, forexample, was widely described by US secu-rity personnel as the development of US-style ‘gated communities’ in the country. Inthe aftermath of the devastation of NewOrleans by Hurricane Katrina in late 2005,meanwhile, US Army Officers talked of theneed to ‘take back’ the City from Iraqi-style‘insurgents’.

As ever, then, the imaginations of urbanlife in colonized zones interact powerfullywith that in the cities of the colonizers.Indeed, the projection of colonial tropes andsecurity exemplars into postcolonial metro-poles in capitalist heartlands is fuelled by anew ‘inner city Orientalism’ (Howell andShryock, 2003). This relies on the widespreaddepiction amongst rightist security or mili-tary commentators of immigrant districtswithin the West’s cities as ‘backward’ zonesthreatening the body politic of the Westerncity and nation. In France, for example, post-war state planning worked to conceptualizethe mass, peripheral housing projects of thebanlieues as ‘near peripheral’ reservationsattached to, but distant from, the country’smetropolitan centres (Kipfer and Goonewar-dena, 2007). Bitter memories of the Algerianand other anti-colonial wars saturate theFrench far-right’s discourse about waning‘white’ power and the ‘insecurity’ caused bythe banlieues—a process that has led to adramatic mobilization of state security forcesin and around the main immigrant housingcomplexes.

Discussing the shift from external to inter-nal colonization in France, Kristin Ross(1996) points to the way in which Francenow ‘distances itself from its (former) colo-nies, both within and without’. This func-tions, she continues, through a ‘greatcordoning off of the immigrants, theirremoval to the suburbs in a massive rework-ing of the social boundaries of Paris andother French cities’ (Ross, 1996, p. 12). The2005 riots were only the latest in a long lineof reactions towards the increasing militari-zation and securitization of this form ofinternal colonization and enforced peripher-ality within what Mustafa Dikeç (2007) hascalled the ‘badlands’ of the contemporaryFrench Republic.5

Indeed, such is the contemporary right’sconflation of terrorism and migration thatsimple acts of migration are now often beingdeemed to be little more than acts of warfare.This discursive shift has been termed the‘weaponization’ of migration (Cato, 2008)—the shift away from emphases on moral obli-gations to offer hospitality to refugeestoward criminalizing or dehumanizingmigrants’ bodies as weapons against purport-edly homogenous and ethno-nationalistbases of national power.

Here the latest debates about ‘asymmetric’,‘irregular’ or ‘low intensity war’, wherenothing can be defined outside of boundlessand never-ending definitions of politicalviolence, blur uncomfortably into the grow-ing clamour of demonization by right andfar-right commentators of the West’sdiasporic and increasingly cosmopolitancities. Samuel Huntington (2005), taking his‘clash of civilizations’ thesis (1998) further,now argues that the very fabric of US powerand national identity is under threat not justbecause of global Islamist terrorism butbecause non-white and especially Latinogroups are colonizing, and dominating, USmetropolitan areas.

Adopting such Manichean imaginations ofthe world, US military theorist William Lind(2004) has argued that prosaic acts of immi-gration from the Global South to the North’s

Downloaded By: [Swets Content Distribution] At: 13:55 14 January 2010

GRAHAM: CITIES AS BATTLESPACE 393

cities must now be understood as acts ofwarfare. ‘In Fourth Generation war’, Lindwrites, ‘invasion by immigration can be atleast as dangerous as invasion by a statearmy.’ Under what he calls the ‘poisonousideology of multiculturalism’, Lind arguesthat migrants within Western nations cannow launch ‘a homegrown variety of FourthGeneration war, which is by far the mostdangerous kind’.

Given the two-way movement of theexemplars of the new military urbanismbetween Western cities and those on colonialfrontiers, fuelled by the instinctive anti-urbanism of national security states, it is nosurprise that cities in both domains are start-ing to display startling similarities as wellas their more obvious differences. In both,hard, military-style borders, fences andcheckpoints around defended enclaves and‘security zones’, superimposed on thewider and more open city, are proliferating.Jersey-barrier blast walls, identity check-points, computerized CCTV, biometricsurveillance and military styles of accesscontrol protect archipelagos of fortifiedenclaves from an outside deemed unruly,impoverished or dangerous. In the formercase, these encompass green zones, war pris-ons, ethnic and sectarian neighbourhoodsand military bases; in the latter they aregrowing around strategic financial districts,embassy zones, tourist spaces, airport andport complexes, sport event spaces, gatedcommunities and export processing zones.

In both domains, efforts to identify urbanpopulations are linked with similar systemsof surveillance, tracking and targetingdangerous bodies amidst the mass of urbanlife. We thus see parallel deployments ofhigh-tech satellites, drones, ‘intelligent’closed circuit TV, ‘non-lethal’ weaponry andbiometric surveillance in the very differentcontexts of cities at home and abroad. And inboth domains, finally, there is a similar sensethat new doctrines of perpetual war are beingused to permanently treat all urban residentsas perpetual targets whose benign nature,rather than being assumed, now needs to be

continually demonstrated to complex archi-tectures of surveillance or data mining as thesubject moves around the city. Such movesare backed by parallel legal suspensionstargeting groups deemed threatening withspecial restrictions, pre-emptive arrests or apriori incarceration within globe-straddlingextra-legal torture camps and gulags.

Whilst these various archipelagos ofenclaves function in a wide variety of waysthey are similar in that they replace urbantraditions of open access with securitysystems that force people to prove legitimacyas they gain access. Urban theorists andphilosophers now wonder whether thepossibilities of the city as a key politicalfoundation for dissent and collective mobili-zation within civil society are being replacedby complex geographies made up of varioussystems of enclaves and camps which linktogether whilst withdrawing from the urbanoutside beyond the walls or access-controlsystems (Graham and Marvin, 2001; Dikenand Laustsen, 2005, p. 64). In such a contextone wonders whether urban securitizationmight reach a level in the future whichwould effectively decouple the strategiceconomic role of cities as drivers of capitalaccumulation from their historic role ascentres for the mobilization of democraticdissent.

Surveillant economy

‘What used to be one among several decisive measures of public administration until the first half of the twentieth century [security], now becomes the sole criterion of political legitimation.’ (Agamben, 2002, pp. 1–2)

Turning to the new military urbanism’s thirdpillar—its political economy—it is importantto stress that the colonization of urban think-ing and practice by militarized ideas of ‘secu-rity’ does not have a single source. In fact, itemanates from a complex range of sources.These encompass sprawling, transnationalindustrial complexes fusing military and

Downloaded By: [Swets Content Distribution] At: 13:55 14 January 2010

394 CITY VOL. 13, NO. 4

security companies with technology, surveil-lance and entertainment ones; a wide range ofconsultants and industries who sell ‘security’solutions as silver bullets to complex socialproblems; and a complex mass of securityand military thinkers who now argue thatwar and political violence centres over-whelmingly on the everyday spaces andcircuits of urban life cities.

As vague and all-encompassing ideas about‘security’ creep to infect virtually all aspectsof public policy and social life (Agamben,2002), so these emerging industrial–securitycomplexes work together on the highly lucra-tive challenges of perpetually targeting every-day activities, spaces and behaviours in citiesand the circulations which link them together.The proliferation of wars sustaining perma-nent mobilization and pre-emptive, ubiqui-tous surveillance within and beyond territorialborders means that the imperative of ‘security’now ‘imposes itself of the basic principle ofstate activity’ (Agamben, 2002, pp. 1–2).

Amidst global economic collapse, marketsfor ‘security’ services and technologies,which overlay military-style systems ofcommand, control and targeting over theeveryday spaces and systems of civilian life,are booming like never before. It is no acci-dent that security–industrial complexes blos-som in parallel with the diffusion of marketfundamentalist notions of organizing social,economic and political life. The hyper-inequalities and urban militarization andsecuritization sustained by neoliberalizationare mutually reinforcing. In a discussion ofthe US state’s response to the Katrina disas-ter, Henry Giroux (2006, p. 172) points outthat the normalization of market fundamen-talism in US culture has made it much more‘difficult to translate private woes into socialissues and collective action or to insist on alanguage of the public good’. He argues that‘the evisceration of all notions of sociality’ inthis case has led to ‘a sense of total abandon-ment, resulting in fear, anxiety, and insecu-rity over one’s future’.

‘International expenditure on homelandsecurity now surpasses established enterprises

like movie-making and the music industry inannual revenues’ (Economic Times, 2007).Homeland Security Research Corp. pointout that ‘the worldwide “total defense”outlay (military, intelligence community, andHomeland Security/Homeland Defense) isforecasted to grow by approximately 50%,from $1,400 billion in 2006 to $2,054 billionby 2015’. By 2005, US defence expenditurealone had reached $420 billion a year—comparable to the rest of the world combined.Over a quarter of this was devoted to purchas-ing services from a rapidly expanding marketof private military corporations. By 2010,such mercenary groups are in line to receive astaggering $202 billion from the US state alone(Schreier and Caparini, 2005).

Meanwhile, worldwide ‘Homeland Secu-rity’ spending outlay is forecasted to grow bynearly 100%, from $231 billion in 2006 to$518 billion by 2015. ‘Where the homelandsecurity outlay was 12% of the world’s totaldefence outlay in 2003, it is expected tobecome 25% of the total defence outlay by2015.’6 Even more meteoric growth isexpected in some of the key sectors of thenew control technologies. Global markets inbiometric technology, for example, areexpected to increase from the small base of$1.5 billion in 2005 to $5.7 billion by 2010.7

Crucially, as the Raytheon exampledemonstrates, the same constellations of‘security’ companies are often involved inselling, establishing and operating the tech-niques and practices of the new militaryurbanism in both war-zone and ‘homeland’cities. Often, as with the EU’s new securitypolicies, states or supranational blocks arebringing in high-tech and militarized meansof tracking illegal immigrants not becausethey are necessarily the best means of address-ing their security concerns but because suchpolicies might help stimulate their defence,security or technology companies to competein booming global markets for securitytechnology. Moreover, Israeli experience inlocking down its cities whilst turning theOccupied Territories into permanent, urbanprison camps, is proving especially influential

Downloaded By: [Swets Content Distribution] At: 13:55 14 January 2010

GRAHAM: CITIES AS BATTLESPACE 395

as a source of ‘combat proven’ exemplars to beimitated around the world (Klein, 2007). Thenew high-tech border fence between the USAand Mexico, for example, is being built by aconsortium linking Boeing to the Israelicompany Elbit whose radar and targetingtechnologies have been honed in the perma-nent lock-down of Palestinian urban life intohighly militarized enclaves (Catterall, 2009).It is also startling how much US counterinsur-gency strategies in Iraq have explicitly beenbased on efforts to effectively scale-up Israelitreatment of the Palestinians during thesecond Intifada.

The political economies sustaining thenew military urbanism inevitably centre oncities as the main production centres ofneoliberal capitalism as well as the mainarenas and markets for rolling out new secu-rity ‘solutions’. The world’s major financialcentres, in particular, orchestrate globalprocesses of militarization and securitiza-tion. They house the headquarters of globalsecurity, technology and military corpora-tions, provide the locations for the world’sbiggest technological corporate universities,which dominate research and developmentin new security technologies and support theglobal network of financial institutionswhich so often work to violently erase orappropriate cities and resources in colonizedlands in the name of neoliberal economicsand ‘free trade’.

The network of so-called ‘global cities’through which neoliberal capitalism isorchestrated—London, New York, Paris,Frankfurt and so on—thus helps to directlyproduce new logics of aggressive colonialacquisition and dispossession by multina-tional capital working closely with state mili-taries and private military operators.

With the easing of state monopolies onviolence, and the proliferation of acquisitiveprivate military and mercenary corporations,so the brutal ‘Urbicidal’ violence and dispos-session that so often helps bolster the parasiticaspects of Western city economies, andfeeds contemporary corporate capitalism,is more apparent than ever (Kipfer and

Goonewardena, 2007). In a world increasinglyhaunted by the spectre of imminent resourceexhaustion, the new military urbanism isalso linked intimately with the neo-colonialexploitation of distant resources to try andsustain richer cities and urban lifestyles. NewYork and London provide the financialand corporate power through which Iraqioil reserves have been reappropriated byWestern oil companies since the 2003 invasion.Neo-colonial land-grabs to grow biofuels forcars or future food for increasingly precariousurban populations of the rich North in thepoor countries of the Global South are alsoorganized through global commodity marketscentred on the world’s major financial cities.Finally, the rapid global growth in markets forhigh-tech security is itself providing a majorboost to global financial cities in times ofglobal economic meltdown.

Urban Achilles

‘If you want to destroy someone nowadays, you go after their infrastructure.’ (Agre, 2001, p. 1)

As I have detailed in a previous article forCity (Graham, 2005), the new militaryurbanism’s penultimate pillar rests on theway that the everyday architectures andinfrastructures of cities—the structures andmechanisms that support modern urbanlife—are now being appropriated by statemilitaries and non-state fighters as primarymeans of waging war and amplifying politi-cal violence. The very conditions of themodern, globalized city—its reliance ondense webs of infrastructure, its density andanonymity, its dependence on importedwater, food and energy—thus create thepossibilities of violence against it, and,crucially, through it. The intensivelynetworked and distanciated nature ofcontemporary urbanism provides the Achil-les heel when the everyday sites and spaces ofcities are transformed into the key‘battlespaces’ of ‘asymmetric’ or ‘irregular

Downloaded By: [Swets Content Distribution] At: 13:55 14 January 2010

396 CITY VOL. 13, NO. 4

warfare’. Urban everyday life everywhere isthus stalked by ambient threats of interrup-tion operating through webs of infrastruc-ture: the blackout, the gridlock, the severedconnection, the technical malfunction, theinhibited flow, the network unavailable sign.

The potential for catastrophic violenceagainst cities and urban life has changed inparallel with the shift of urban life towardsever-greater reliance on modern infrastruc-tures. The result of this is that the everydayinfrastructures of urban life—highways,metro trains, computer networks, water andsanitation systems, electricity grids, airlin-ers—may be easily assaulted and turned intoagents either of instantaneous terror, debili-tating disruption, even demodernization.Increasingly, then, in high-tech societiesdominated by socially abstract interconnec-tions and circulations, both high-techwarfare and terrorism ‘targets the means oflife, not combatants’ (Hinkson, 2005, pp.145–146). As John Robb (2007) puts it:

‘most of the networks that we rely on for city life—communications, electricity, transportation, water—are extremely vulnerable to intentional disruptions. In practice, this means that a very small number of attacks on the critical hubs of an [infrastructure] network can collapse the entire network.’

Many recent examples demonstrate hownon-state actors now gain much of theirpower by appropriating the technical infra-structure necessary to sustain modern,globalized urban life in order to project, andmassively amplify, the power of their politi-cal violence. Insurgents use the city’s infra-structure to attack New York, London,Madrid or Mumbai. Insurgents disrupt elec-tricity networks, oil pipelines or mobilephone systems in Iraq, Nigeria and else-where. Somali pirates systematically hijack-ing global shipping routes have even beenshown to be using ‘spies’ in London’s ship-ping brokers to provide intelligence for theirattacks. In doing so, such actors can get bywith the most basic of weapons, transforming

airliners, metro trains, cars, mobile phones,electricity and communications grids, orsmall boats, into deadly devices.

However, such threats of ‘infrastructuralterrorism’, while very real and important,pale beside the much less visible efforts ofstate militaries to target the essential infra-structure that makes modern urban lifepossible. The US and Israeli forces, for exam-ple, have long worked to systematically‘demodernize’ entire urban societies throughthe destruction of the life-support and infra-structure systems of Gaza, the West Bank,Lebanon or Iraq since 1991. States have thusreplaced total war against cities with thesystematic destruction of water and electric-ity systems with weapons—such as bombswhich rain down millions of graphite spoolsto short-circuit electricity stations—designedespecially for this task.

Ostensibly means of bringing unbearablepolitical pressure on adversary regimes, suchpurportedly ‘humanitarian’ modes of warend up killing the sick, the ill and the oldalmost as effectively as carpet bombing, butbeyond the capricious gaze of the media.Such wars on public health are engineeredthrough the deliberate generation of publichealth crises in highly urbanized societieswhere no infrastructural alternatives tomodern water, sewerage, power, medical andfood supplies exist.

The devastating Israeli siege of Gaza sinceHamas were elected there in 2006 is anotherpowerful example here. This has transformeda dense urban corridor, with 1.5 millionpeople squeezed into an area the size of theIsle of Wight, into a vast prison camp. Withinthis the weak, the old, the young and sick dieinvisibly in startling numbers beyond thecapricious gaze of the mainstream media.Everyone else is forced to live somethingapproaching what Georgio Agamben (1998)has called ‘bare life’—a biological existencewhich can be sacrificed at any time by acolonial power which maintains the right tokill with impunity but has withdrawn allmoral, political or human responsibilities forthe population.

Downloaded By: [Swets Content Distribution] At: 13:55 14 January 2010

GRAHAM: CITIES AS BATTLESPACE 397

Increasingly, such formal ‘infrastructuralwar’, based on the severing of the lines ofsupply which continually work to bringmodern urban life into its very existence as ameans of political coercion, blurs seamlesslyinto economic competition and energygeopolitics. Putin’s resurgent Russia, forexample, these days gains much of its strate-gic power not through formal militarydeployments but by its continued threats toswitch off the energy supplies of Europe’scities at a stroke.

The systematic demodernization of highlyurbanized societies through air power isjustified by ‘air power theory’, which existsas the dark shadow of long-discreditedmodernization theory. This suggests thatsocietal ‘progress’ can be reversed, pushingsocieties ‘back’ towards increasingly primi-tive states. Thomas Friedman, for example,deployed such arguments as NATO crankedup its bombing campaign against Serbia in1999. Picking up a variety of historic datesthat could be the future destiny of Serbiansociety, post bombing, Friedman urged thatall of the movements and mobilities sustain-ing urban life in Serbian cities should bebrought to a grinding halt. ‘It should belights out in Belgrade’, he said. ‘Every powergrid, water pipe, bridge, road and war-relatedfactory has to be targeted […]. We will setyour country back by pulverizing you. Youwant 1950? We can do 1950. You want 1389?We can do that, too!’ (cited in Skoric, 1999).In Friedman’s scenario, the precise reversalof time that the adversary society is to bebombed ‘back’ through is presumably amatter merely of the correct weapon andtarget selection.

The politics of seeing the bombing of infra-structure as a form of reversed modernizationplays a much wider discursive role. It alsodoes much to sustain and bolster the long-standing depiction of countries deemed ‘lessdeveloped’, along some putatively linear lineof modernization, as pathologically back-ward, intrinsically barbarian, unmodern, evensavage. Aerial bombing aimed at demodern-ization thus works to reinforce Orientalist

imaginations which relegate ‘the “savage”,colonized target population to an “other”time and space’ (Deer, 2007, p. 3). Indeed,Nils Gilman (2003, p. 199) has argued that, ‘aslong as modernization was conceived as aunitary and unidirectional process ofeconomic expansion’, it would be possible toexplain backwardness and insurgency ‘onlyin terms of deviance and pathology’.

At its heart, then, the systematic demod-ernization of whole societies in the name of‘fighting terror’ involves a darkly ironic andself-fulfilling prophecy. As Derek Gregory(2004) has argued, drawing on GeorgioAgamben’s ideas (1998), the demoderniza-tion of entire Middle Eastern cities and soci-eties, through both the Israeli wars againstLebanon and the Palestinians, and the US‘war on terror’, are both fuelled by similar‘Orientalist’ discourses. These revivify long-standing tropes and work by ‘casting out’ordinary civilians and their cities—whetherthey be in Kabul, Baghdad or Nablus—‘sothat they are placed beyond the privilegesand protections of the law so that their lives(and deaths) [are] rendered of no account’(Gregory, 2003, p. 311). Here, then, beyondthe increasingly fortified homeland, ‘sover-eignty works by abandoning subjects, reduc-ing them to bare life’ (Diken and Laustsen,2002, original emphasis).

Citizen-soldiers

‘All efforts to render politics aesthetic culminate in one thing—war.’ (Benjamin, 1968, p. 241)8

The final key pillar sustaining the new mili-tary urbanism is the way it gains much of itspower and legitimacy by fusing seamlesslywith militarized veins of popular, urban andmaterial culture. Very often, for example,military ideas of tracking, surveillance andtargeting do not require completely newsystems. Instead, they simply appropriate thesystems of high-tech consumption that havebeen laid out within and through cities to

Downloaded By: [Swets Content Distribution] At: 13:55 14 January 2010

398 CITY VOL. 13, NO. 4

sustain the latest means of digitally organizedtravel and consumption. Thus, as in centralLondon, congestion-charging zones thusquickly morph into ‘security’ zones. Internetinteractions and transactions provide thebasis for ‘data mining’ to root out suppos-edly threatening behaviours. Dreams of‘smart’ and ‘intelligent’ cars blur with thoseof robotic weapons systems. Satellite imageryand GPS support new styles of civilian urbanlife as well as ‘precision’ urban bombing.And, as in the new security initiative inLower Manhattan, CCTV cameras designedto make shoppers feel secure are transformedinto ‘anti-terrorist’ screens.

Perhaps the most powerful series of civil-ian–military crossovers at the heart of the newmilitary urbanism, however, are being forgedwithin cultures of virtual and electronic enter-tainment and corporate news. Here, to temptin the nimble-fingered recruits best able tocontrol the latest high-tech drones and weap-onry, the US military produces some of themost popular urban warfare consumer videogames. Highly successful games like the USArmy’s America’s Army or US Marines’ FullSpectrum Warrior9 allow players to slay‘terrorists’ in fictionalized and Orientalizedcities in frameworks based directly on thoseof the US military’s own training systems.

The main purpose of these games,however, is public relations: they are apowerful and extremely cost-effective meansof recruitment. ‘Because the Pentagonspends around $15,000 on average wooingeach recruit, the game needs only to result in300 enlistments per year to recoup costs’(Stahl, 2006, p. 123). Forty per cent of thosewho join the Army have previously playedthe game (Stahl, 2006, p. 123). The game alsoprovides the basis for a sophisticated surveil-lance system through which Army recruit-ment efforts are directed and targeted. In themarketing speak of its military developers,America’s Army is designed to reach thesubstantial overlap in ‘population betweenthe gaming population & the army’s targetrecruiting segments’. It addresses ‘tech-savvyaudiences and afford the army a unique,

strategic communication advantage’ (Lenoir,n.d.).

To close the circle between virtual enter-tainment and virtual killing, control panelsfor the latest US weapons systems—such asthe latest control stations for ‘pilots’ orarmed Predator drones, manufactured by ourold friends Raytheon (see Figure 1(b))—nowdirectly imitate the consoles of Playstation2s,which are, after all, most familiar to recruits.The newest Predator control systems fromRaytheon—leading manufacturer of assassi-nation drones as well as key player in theUK’s E-borders consortium—deliberatelyuse the ‘same HOTAS [hands on stick andthrottle] system on a [ ] video game’.Raytheon’s UAV designer argues that‘there’s no point in re-inventing the wheel.The current generation of pilots was raisedon the [Sony] Playstation, so we created aninterface that they will immediately under-stand’ (Richfield, 2006). Added to this, manyof the latest video games actually depict thevery same armed drones as those used inassassination raids by US forces.10

Wired magazine, talking to one Predator‘pilot’, Private Joe Clark, about this experi-ence directing drone assassinations from avirtual reality ‘cave’ on the edge of Las Vegas,points out that he has, in a sense ‘been prep-ping for the job since he was a kid: He playsvideogames. A lot of videogames. Back in thebarracks he spends downtime with an Xboxand a PlayStation.’ After his training, ‘whenhe first slid behind the controls of a Shadow[Unmanned Aerial Vehicle] UAV, the pointand click operation turned out to work muchthe same way. “You watch the screen. Youtell it to roll left, it rolls left. It’s prettysimple”’, Clark says (Shachtman, 2005).

Projecting such trends, Bryan Finoki spec-ulates about a near-future where ‘videogames become the ultimate interface forconducting real life warfare’, as virtual realitysimulators used in video gaming convergecompletely with those used in military train-ing and exercises. Finoki takes the videogame-like existence of the Las Vegas Predator‘pilots’, with their Playstation-style controls

Downloaded By: [Swets Content Distribution] At: 13:55 14 January 2010

GRAHAM: CITIES AS BATTLESPACE 399

as his starting point. He speculates, only halfironically, whether future video gamers could‘become decorated war heroes by virtue oftheir eye-and-hand coordination skills,which would eventually dominate the trig-gers of network-centric remote controlledwarfare?’11

A final vital circuit of militarization linkingurban and popular culture in domestic citiesto colonial violence in occupied ones centreson the militarization of car culture. Thisparticular link is most powerfully symbolizedby the rise of explicitly militarized SportsUtility Vehicles, especially in the USA(Mendietta, 2005). The rise and fall of theHummer is an especially pivotal examplehere. Here, US military vehicles for urbanwarfare have been directly modified as hyper-aggressive civilian vehicles marketed as patri-otic embodiments of the ‘war on terror’.

‘With names like Tracker, Equinox,Freestyle, Escape, Defender, Trail Blazer,Navigator, Pathfinder, and Warrior,’ DavidCampbell (2005, p. 958) writes, ‘SUVs popu-late the crowded urban routes of daily lifewith representations of the militarized fron-tier.’ Crucial here are the ways in which mili-tarized urban automobile cultures help tomaterialize and territorialize the separationof the domestic city lying ‘inside’ the ‘home-space’ of the US or Western nation or city,from the ‘borderlands’ cursed with the ongo-ing resource wars surrounding oil exploita-tion. Such borderlands, Campbell (2005,p. 945) continues, ‘are conventionally under-stood as distant, wild places of insecuritywhere foreign intervention will be necessaryto ensure domestic interests are secured’. Farfrom enriching local populations, dominantmeans of organizing exploitation andpipelines actually work to further marginal-ize impoverished indigenous communities,ratcheting up insecurity and violence in theprocess. The destiny of such people andplaces is thus violently ‘subsumed by theprivilege accorded a resource (oil) that iscentral to the American way of life, the secu-rity of which is regarded as a fundamentalstrategic issue’ (Campbell, 2005, p. 945).

Synoptic politics

‘The city [is] not just the site, but the very medium of warfare—a flexible, almost liquid medium that is forever contingent and in flux.’ (Weizman, 2005, p. 53)

The power of the new military urbanismthesis is that it forces together sites andcircuits of militarization that are usuallyscrutinized in isolation. It achieves this,moreover, by attending to the visceral andmaterial transformations across everydayurban life rather than the abstractions ofgeopolitics and international relations.Finally, it attends to the fundamental connec-tions in the contemporary world betweencities and urbanization on the one hand andquestions of state and non-state politicalviolence on the other.

In encompassing the ways in which tech-nophiliac dreams of control and omniscienceblend with Foucauldian boomerang effects,political economies of ‘security’, projectionsof political violence through the infrastruc-tural circuits of cities, and the militarizationof popular, electronic, material and automo-bile culture, the new military urbanism thesisreveals with unprecedented clarity howpernicious circuits of militarization operateacross a broad swathe. The ways in which thenew military urbanism works to colonize theeveryday spaces and sites of city life, underall-embracing paradigms that project lifeitself to be little but war, and within a bound-less and unending ‘battlespace’, emergestarkly.

Many contemporary military and ‘secu-rity’ theories and doctrines now concludethat ‘war’ is now ‘everywhere and every-thing. It is large and small. It has no bound-aries in time and space. Life itself is war’(Agre, 2001). Working though xenophobicand deeply anti-urban views of the world,which continuously telescope betweenconventional North–South binaries, suchperspectives see the world through techno-philiac cross-hairs; they automatically trans-late difference into othering, othering into

Downloaded By: [Swets Content Distribution] At: 13:55 14 January 2010

400 CITY VOL. 13, NO. 4

targeting, and targeting into violence. Suchlogics, moreover, have been shown to beconstituted through circuits of popularculture, from car culture to video games, filmand science fiction, through to the deepeningcrossovers between war, entertainment andweapon design. What emerges is a stark chal-lenge to all those concerned with the right tothe city, and the future of democratic urbanlife, at the start of this quintessentially urbancentury. For the challenge now is to forgea synoptic and multifaceted politics, whichitself embraces highly fluid new mediatechnologies and telescopes across globalNorth–South divides, to systematically erodethe key pillars of the new military urbanism.

Such a politics, though, must engage firstwith the ways in which ideas of an ‘urbanpublic domain’ must move beyond traditionalnotions that they encompass both mediacontent and geographical spaces exempt fromproprietary control which combine to ‘formour common aesthetic, cultural and intellec-tual landscape’ (Zimmermann, 2007). Ratherthan permanent, protected zones of urbanityor ‘publicness’, organized hierarchically bykey gatekeepers, transnational urban life isnow characterized by constantly emergingpublic domains which are highly fluid, plural-ized and organized by interaction betweenmany producers and consumers (Zimmer-mann, 2007). The new public domains,through which challenges to the new militaryurbanism can be sustained, must forge collab-orations and connections across distance anddifference. They must materialize newpublics, and create new countergeographicspaces. Ironically, they must use the very samemedia and control technologies that the mili-taries, and the transnational architecture ofsecurity states, are using so perniciously intheir attempts to pre-emptively lock-downdemocratic politics (Zimmermann, 2007).

Notes

1 1 Major David Pendall (2004) of the US Army writes that ‘friendly cyber or virtual operations live on the same networks and systems as adversaries’

networks and systems. In most cases, both use the same protocols, infrastructures, and platforms. They can quickly turn any space into a battlespace.’

2 2 See http://www.northcom.mil/3 3 See Derek Gregory, The Colonial Present, Oxford:

Blackwell, 2004; David Harvey, The New Imperialism, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

4 4 On the panopticon, see Mitchell (2000). On Hausmannian planning, see Weizman (2003). And on fingerprinting, see Sengoopta (2003).

5 5 See also Ross (1996, pp. 151–155).6 6 Source: Homeland Security Research Corp., 2007,

at www.photonicsleadership.org.uk/files/MarketResearch_DefenceSecurity.doc

7 7 Source: Homeland Security Research Corp., 2007, at www.photonicsleadership.org.uk/

8 8 Thanks to Marcus Power for this reference.9 9 See http://www.americasarmy.com/ and http://

www.fullspectrumwarrior.com/ respectively.10 10 One example here is the game, Battlefield 2, see

Quilty-Harper (2006).11 11 See ‘War Room’, Subtopia Blog, 20 May 2006, at

http://subtopia.blogspot.com/2006/05/war-room_20.html

References

Agamben, G. (1998) Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Agamben, G. (2002) ‘Security and terror’, Theory andEvent 5(4), pp. 1–2.

Agre, P. (2001) ‘Imagining the next war: infrastructuralwarfare and the conditions of democracy’, RadicalUrban Theory,14 September, http://www.rut.com/911/Phil-Agre.html

Amoore, L. (2009) ‘Algorithmic war: everydaygeographies of the war on terror’, Antipode 41(1),pp. 49–69.

Benjamin, W. (1968) ‘The work of art in the age ofmechanical reproduction’, in H. Arendt (ed.)Illuminations, trans. H. Zohn, pp. 217–252. NewYork: Schocken.

Blackmore, T. (2005) War X: Human Extensions inBattlespace. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Campbell, D. (2005) ‘The biopolitics of security: oil,empire, and the sports utility vehicle’, AmericanQuarterly 57(3), pp. 943–997.

Cato (2008) The Weaponization of Immigration. Centerfor Immigration Studies, February, http://www.cis.org/weaponization_of_immigration.html

Catterall, B. (2009) ‘Is it all coming together? Thoughtson urban studies and the present crisis: (15) elitesquads: Brazil, Prague, Gaza and beyond’, City13(1), pp. 159–171.

Chow, R. (2006) The Age of the World Target: Self-Referentiality in War, Theory, and ComparativeWork. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Downloaded By: [Swets Content Distribution] At: 13:55 14 January 2010

GRAHAM: CITIES AS BATTLESPACE 401

Crandall, J. (1999) ‘Anything that moves: armed vision’,C Theory,June, http://www.ctheory.net/articles.aspx?id

Deer, P. (2007) ‘Introduction: the ends of war andthe limits of war culture’, Social Text 25(2), pp.1–11.

Dikeç, M. (2007) Badlands of the Republic: Space,Politics and Urban Policy. Oxford: Blackwell.

Diken, B. and Laustsen, C.B. (2002) ‘Camping as acontemporary strategy: from refugee camps to gatedcommunities’, AMID Working Paper Series, 32,Aalborg University.

Diken, B. and Laustsen, C.B. (2005) The Culture ofException: Sociology Facing the Camp. London:Routledge.

Economic Times (2007) ‘Spending on internal security toreach $178 bn by 2015’, 27 December, http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/articleshow/msid-2655871,prtpage-1.cms

Foucault, M. (2003) Society Must be Defended: Lecturesat the Collège de France, 1975–6. London: AllenLane.

Gilman, N. (2003) Mandarins of the Future:Modernization Theory in Cold War America.Baltimore: Johns Hopkins.

Giroux, H. (2006) ‘Reading Hurricane Katrina: race,class, and the biopolitics of disposability’, CollegeLiterature I 33(3), pp. 171–196.

Graham, S. (2005) ‘Postmortem city’, City 8(2),pp. 165–186.

Graham, S. (2006) ‘Switching cities off: urbaninfrastructure and US air power’, City 9(2),pp. 170–192.

Graham, S. (2008) ‘Robowar dreams: US militarytechnophilia and Global South urbanization’, City12(1), pp. 25–49.

Graham, S. (2010) Cities Under Siege: The New MilitaryUrbanism. London: Verso (forthcoming).

Graham, S. and Marvin, S. (2001) Splintering Urbanism.London: Routledge.

Gregory, D. (2003) ‘Defiled cities’, Singapore Journal ofTropical Geography 24(3), pp. 307–326.

Gregory, D. (2004) The Colonial Present. Oxford:Blackwell.

Harvey, D. (2005) The New Imperialism. Oxford: OxfordUniversity Press.

Hinkson, J. (2005) ‘After the London bombings’, ArenaJournal 24, pp. 139–159.

Howell, S. and Shryock, A. (2003) ‘Cracking down ondiaspora: Arab Detroit and America’s “war onterror”’, Anthropological Quarterly 76(3), pp.443–462.

Huntington, S. (1998) The Clash of Civilizations and theRemaking of World Order. New York: Simon andSchuster.

Huntington, S. (2005) Who Are We: The Challenges toAmerica’s National Identity. New York: Simon andSchuster.

Kipfer, S. and Goonewardena, K. (2007) ‘Colonizationand the new imperialism: on the meaning ofurbicide today’, Theory and Event 10(2), pp. 1–39.

Klein, N. (2007) The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of DisasterCapitalism. London: Allen Lane.

Kobe, N. (2007) ‘Government announces that half of£1.2 billion in funding for technology to boostborder security will go to Raytheon-led TrustedBorders consortia for a screening system’, IT Pro,14November, http://www.itpro.co.uk/139053/650-million-e-borders-contract-to-raytheon-group

Lenoir, T. (n.d.) ‘Taming a disruptive technology:America’s Army, and the military–entertainmentcomplex’, undated presentation, Stanford University,http://www.almaden.ibm.com/coevolution/pdf/spohrer.pd

Lind, W. (2004) ‘Understanding fourth generation war’,Military Review,September–October, http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/milreview/lind.pdf

Mendieta, E. (2005) ‘The axle of evil; SUVing throughthe slums of globalizing neoliberalism’, City 9(2),pp. 195–204.

Mills, M. and Huber, P. (2002) ‘How technology willdefeat terrorism’, City Journal,Winter, http://www.city-journal.org/html/12_1_how_tech.html

Mitchell, T. (2000) ‘The stage of modernity’, in T. Mitchell(ed.) Questions of Modernity, pp. 1–34.Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Pendall, D. (2004) ‘Effects-based operations exercise ofnational power’, Military Review,January–February,http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/milreview/pendall.pdf

Qiao, L. and Wang, X. (2002) Unrestricted Warfare.Panama: Pan American Publishing.

Quilty-Harper, C. (2006) ‘Man the unmanned aerialvehicle in BF2’, Joystiq.Com,6 March, http://www.joystiq.com/2006/03/06/man-the-unmanned-aerial-vehicle-in-bf2/

Richfield, P. (2006) ‘New “cockpit” for Predator?’, C4isrJournal, 31 October, http://www.c4isrjournal.com/story.php?F=2323780

Robb, J. (2007) ‘The coming urban terror’, CityJournal,Summer, http://www.city-journal.org/html/17_3_urban_terrorism.html

Ross, K. (1996) Fast Cars, Clean Bodies: Decolonizationand the Reordering of French Culture. Cambridge,MA: MIT Press.

Schreier, F. and Caparini, M. (2005) Privatising Security:Law, Practice and Governance of Private Militaryand Security Companies, Geneva Centre for theDemocratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF)Occasional Paper No. 6, March 2005,hei.unige.ch/sas/files/portal/issueareas/security/security_pdf/2005_Schreier_Caparini.pdf

Sengoopta, C. (2003) Imprint of the Raj: HowFingerprinting was Born in Colonial India. London:Pan Books.

Downloaded By: [Swets Content Distribution] At: 13:55 14 January 2010

402 CITY VOL. 13, NO. 4

Shachtman, N. (2005) ‘Attack of the drones’, Wired,Issue 13.06—June, http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/13.06/drones.html

Skoric, I. (1999) ‘On not killing civilians’, posted atamsterdam.nettime.org, 6 May.

Stahl, R. (2006) ‘Have you played the war on terror?’,Critical Studies in Media Communication 23(2), pp.112–130.

Veracini, L. (2005) ‘Colonialism brought home: on thecolonialization of the metropolitan space’,Borderlands 4(1), http://www.borderlands.net.au/vol4no1_2005/veracini_colonialism.htm

Weizman, E. (2003) ‘Military operations as urbanplanning’, interview with P. Misselwitz, Mute

Magazine,August, http://www.metamute.org/?q=en/node/6317

Weizman, E. (2005) ‘Lethal theory’, LOG Magazine,April, p. 53.

Zimmermann, P. (2007) ‘Public domains: engagingIraq through experimental digitalities’,Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media48(2), pp. 66–83.

Stephen Graham is Professor of HumanGeography at the University of Durham.Email: [email protected]

Downloaded By: [Swets Content Distribution] At: 13:55 14 January 2010

CITYTaylor and FrancisCCIT_A_GN156975.sgm10.1080/City1360-4813 (print)/1470-3629 (online)Original Article2009Taylor & Francis134000000December 2009

VOLUME 13 NUMBER 4 DECEMBER 2009

EDITORIAL 379

ArticlesCITIES AS BATTLESPACE: THE NEW MILITARY URBANISM

Stephen Graham 383

TRANSPARENT CITIES: RE-SHAPING THE URBAN EXPERIENCE THROUGH INTERACTIVE

VIDEO GAME SIMULATION

Rowland Atkinson and Paul Willis 403

NEO-URBANISM IN THE MAKING UNDER CHINA’S MARKET TRANSITION

Fulong Wu 418

PROBING THE SYMPTOMATIC SILENCES OF MIDDLE-CLASS SETTLEMENT: A CASE STUDY

OF GENTRIFICATION PROCESSES IN GLASGOW

Kirsteen Paton 432

URBAN SOCIAL MOVEMENTS AND SMALL PLACES: SLOW CITIES AS SITES OF ACTIVISM

Sarah Pink 451

‘Cities for People, Not for Profit’: background and commentsEDITOR’S INTRODUCTION 466

PETER MARCUSE AND THE ‘RIGHT TO THE CITY’: INTRODUCTION TO THE KEYNOTE

LECTURE BY PETER MARCUSE

Bruno Flierl 471

RESCUING THE ‘RIGHT TO THE CITY’Martin Woessner 474

THE NEW MIKADO? TOM SLATER, GENTRIFICATION AND DISPLACEMENT

Chris Hamnett 476

CITIES FOR PEOPLE, NOT FOR PROFIT—FROM A RADICAL-LIBERTARIAN AND

LATIN AMERICAN PERSPECTIVE

Marcelo Lopes de Souza 483

CITIES AFTER OIL (ONE MORE TIME)Adrian Atkinson 493

Downloaded By: [Swets Content Distribution] At: 13:55 14 January 2010

DebatesTHE BANTUSTAN SUBLIME: REFRAMING THE COLONIAL IN RAMALLAH

Nasser Abourahme 499

Scenes & SoundsCHICAGO FADE: PUTTING THE RESEARCHER’S BODY BACK INTO PLAY

Loïc Wacquant 510

ReviewsTHINKING THE URBAN: ON RECENT WRITINGS ON PHILOSOPHY AND THE CITY

Philosophy and the City: Classical to Contemporary Writings, edited bySharon M. MeagherGlobal Fragments: Globalizations, Latinamericanisms, and Critical Theory, by Eduardo MendietaReviewed by David Cunningham 517

EndpieceIS IT ALL COMING TOGETHER? THOUGHTS ON URBAN STUDIES AND THE PRESENT CRISIS: (16) COMRADES AGAINST THE COUNTERREVOLUTIONS: BRINGING PEOPLE (BACK?) IN

Bob Catterall 531

Volume Content and Author Index 551

Downloaded By: [Swets Content Distribution] At: 13:55 14 January 2010