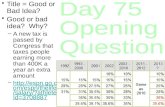

Good and Bad

-

Upload

nndesign87 -

Category

Documents

-

view

213 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Good and Bad

-

POLICY AND PRACTI CE

Good and bad fortune of the plan for the constructionof 5,000 (low- and middle-income) housing unitsin Brussels

Nicolas Bernard

Received: 27 May 2008 / Accepted: 27 May 2008 / Published online: 25 July 2008 Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2008

Abstract Especially due to the impoverishment of the population of the capital,combined with the increasing tendency to family separation, the need for low-income

housing is in constant progress in Brussels. Unfortunately, the public supply remains

inadequate to absorb this demand. The Brussels authorities have actually started an

extensive plan for the construction of 5,000 low- and middle-income units, but this plan is

faced with, if not a failure, at least serious problems in its realization. But why is it so

arduous to build social housing in the Brussels Capital Region? This question constitutes

the object of this article.

Keywords Brussels Housing policy Social housing

1 Introduction

Housing policies are the subject of intense activity right now in Brussels. The flurry of

activity in the capital is effectively coordinated by issues such as rent allowances,

reforming the rent scale for low-income estate agencies, and regulating rents on the private

market dominate the agenda. Yet, one event is tending to supplant all the others in terms of

importance. This is the vast programme to build 5,000 housing units in Brussels over

20042009 (3,500 low-income and 1,500 middle-income units). Rather than paint a

superficial picture of all of these measures, given the amount of space allotted for this

article, it appears more judicious to shine the spotlights on this momentum. Indeed, from

a scientific viewpoint, in-depth study of a subject is preferable to a rough overview of a

broad field.

N. Bernard (&)Facultes universitaires Saint-Louis, Brussels, Belgiume-mail: [email protected]

123

J Hous and the Built Environ (2008) 23:231239DOI 10.1007/s10901-008-9114-0

-

2 The figures

2.1 Low-income housing supply

Social housing in Brussels combines 33 public housing companies that, under the guard-

ianship of an umbrella organization (the Brussels Region Housing Company), manage each

one their own housing units. However, their autonomy is restricted through the fact that

they are submitted to a uniform regional regulation that applies to all housing companies.

There are slightly more than 38,000 low-income housing units in Brussels. This is 8% of

the regions overall building supply.1 Some people assert that the capital suffers from the

comparison with the situation in Wallonia, where low-income housing is 25% of the total.

This comparison nevertheless quickly proves to be flawed, for the latter figure is the

proportion of the 100,000 low-income housing units in Wallonia over not the total number

of housing units (as is the case in Brussels), but over the number of (private and public)

tenants, who actually account for a smaller percentage of the population in the south (26%in total)2 than in the centre (54% in total).3 If we correct for this methodological bias

(which flaws the calculation considerably) and adopt an identical basis for comparison,

e.g., the number of low-income housing units over the number of tenants, the comparison

is noticeably less in Brussels disfavour, since one out of eight tenants lives in low-income

housing in Brussels compared with one out of four in the Walloon Region.4

Nevertheless, Belgium as a whole clearly continues to lag behind its European neigh-

bours when it comes to low-income housing.5 In the Netherlands, for example, no less than

36% of the total housing supply is earmarked for low-income housing, which means that

two of three tenants lives in state-owned housing.6 More generally, we see that policies to

facilitate housing ownership and measures to build low-income housing are inversely

related across Europe as a whole.7

Despite all this, the Brussels Region seems to be losing on both fronts, for it has fewer

private owners8 and less low-income housing9 than Wallonia, for example. Of course, one

always finds fewer home owners in (large) cities than in rural areas,10 but with its 43%

home ownership figure, Brussels continues to lag 515% points behind Belgiums other

urban centres.11 Belgium also appears to have lost on both scores compared with its

European neighbours (France and the Netherlands) as well, for there is no rent control

1 Zimmer (2006, pp. 1011).2 In this way we record 73% of ownersoccupiers in Wallonia, 19% of tenants of private letters and 7% ofsocial letters.3 Brussels indeed numbers 42% of ownersoccupiers, 46% of tenants of private letters and 8% of socialletters. See Charles (2007).4 Bernard (2006a, p. 33).5 For France, see, for example, Laferre`re (2005, p. 140).6 Elsinga (2005, p. 91).7 Bernard (2005a, p. 15).8 Observatoire de la sante et du social de la Commission communautaire commune de Bruxelles (2006, p.63).9 Zimmer (2000).10 Charles (2007).11 So, the home-ownership rates are 58.2% for Charleroi, 53.2% for Ghent, 53.1% for Antwerp, and 49.3%for Lie`ge. See the results of the socio-economic survey of 96.9% of the countrys households that theMinistry of Economic Affairs commissioned from the National Statistics Institute in 2001.

232 N. Bernard

123

-

scheme in effect in our country12 and, in addition, we have no rent allowance scheme to

help tenants out financially.13

One last word, which tends to make the supply of low-income housing in Brussels

appear even smaller yet: When it comes to vacant housinga true scandal in the Brussels-

Capital Region, if only because of the number of vacant dwellings (between 15,000 and

30,000 units)14most of the time people speak about those that are privately owned, but

far too often the fact that many state-owned low-income housing units are also vacant(1,800 of a total of 38,000, which is no less than 5% of the supply)15 are also vacant. The

reasons: their poor state and the need to carry out rehabilitation work. Moreover, reha-

bilitation is under way through the various investment plans that have been adopted, as a

result of which more than half of the supply should eventually be brought up to snuff.

However, we must bear in mind that thisnecessarywide-scale refurbishing of low-

income housing will reduce the supply of publicly-owned housing even more, as the

Brussels Junior Minister for housing herself has admitted, for three subsidised units will

yield only two units, on average, after renovation, if only to comply with updated mini-

mum living space standards).16 For the sake of comparison, 2,551 units remain unused in

Wallonia (for a ratio that is just barely less than that in the Brussels-Capital Region).17

What is more, 30% of these vacant Walloon low-income housing units are vacant because

of major renovation required to be able to let them again. Be that as it may, Wallonias

Special Investment Plan provides for the deconstruction (i.e., the destruction) of

1,589 inhabitable state-owned flats.

2.2 The demand for low-income housing

After these public supply statistics, it is time to analyse the low-income housing demand.To approach this matter from the right angle, one must know that many more people would

like to get into state-owned low-income housing than the 30,000 households that are

traditionally quoted as being on the low-income housing waiting list. Indeed, many of the

households eligible for public housing because of their low incomes do not even take the

trouble to register with the public departments real estate companies because they are

discouraged by the extremely long waiting times (up to 10 years for families with three or

more children!) Be that as it may, no fewer than one of two Brussels dwellers (among those

who are eligible for the public housing stock, i.e. those who are not already owner) is

entitled to sign up for social housing on the basis of their financial resources. This shows

the great distance that must still be covered to meet the potential demand.18

The main reason for this inertia is the extremely low rotation rate in low-income

housing: a mere 5% per annum. This means that only one of 20 units becomes vacant at the

end of each year. To put it simply, when you get into public housing, it is for life: When

you vacate the premises, it is usually feet first. As a result, low-income housing is no longer

the trampoline towards an improvement in housing conditions that it strove to be in the

12 Bernard (2006c, p. 1).13 Bernard (2006d, p. 40).14 Demanet (2007).15 Bernard (2005b, p. 1).16 Bernard and Van Mieghem (2005).17 Institut Emile Vandervelde (2003, p. 1).18 Zimmer (1996).

Good and bad fortune 233

123

-

past. Today, it tends more to be the end of the line. The social lift that public housing issupposed to be is no longer climbing. Its cables are stuck, and in some cases it even seems

to be coming down.19

Be that as it may, and paradoxically in view of what has just been said, low-income

housing is more than ever necessary, given the spectacular surge in the demand for publichousing. At least three factors can be pinpointed to explain this phenomenon. First of all,

the number of residents in the capital is rising (a net increase of 50,000 people between

1997 and 2004), reversing a longstanding trend of urban flight.20 Second, as a result of the

rising trend of family decomposition (divorces, separations, etc.), the housing demand is

necessarily increasing for the same number of inhabitants.21 Finally, the living conditions

of Brussels residents have been deteriorating. For 100 recipients of the minimum guar-

anteed income (minimexwhich has since been replaced by the so-called integration

income) in 1995, there were 140 recipients in 2002. More generally, the number of

minimum income recipients has been multiplied by 2.89 since the Brussels-Capital

Regions creation in 1989. As a result of this pauperisation, the rental arrears owed to the

public offices real estate companies quadrupled between 1989 and 2002, forcing the

Brussels Region Housing Society (in French: SLRB) to increase the sums it allocates to

these companies considerably in order to fill the gap. As a result, the social housing

companies, which are in or almost in the red, do not dare build any new housing.

3 The construction of low-income housing in Brussels

3.1 The past (put in perspective)

The building of public housing flourished in the inter-war period and the 1970s, when the

main focus was to support the building industry. This activity fell off sharply thereafter. As

a result, only 19 low-income housing units per year on average are built in Brussels

today.22 In striking contrast, the private sector currently builds 2,000 units a year.How does one explain the extremely feeble low-income housing construction activity

posted these past years? Primarily by the fact that the regional authorities have focused the

bulk of their financial means on renovating the public rental supply. Following a cadastretechnique that put the refurbishment needs at 450 million euros, the authorities released

75 million euros, via the 19992001 investment plan (which concerns 5,000 housing

units), while the 20022005 investment plan managed to mobilise 150 million euros (for

17,000 housing units) and the supplemental 4-year plan another 50 million euros in order

to get a certain number of low-income housing units to comply with the Brussels Housing

Code.23 Finally, another 200 million euros was released for this purpose under the 2006

2009 4-year plan. So much for budget commitments. When it comes to actual achieve-

ments and the state of progress of such rehabilitation work, we are forced to acknowledge

that things are moving slower than planned, for, given the current renovation rate of 1,042

19 Noel (2003, p. 120).20 Van Criekingen (2006).21 Noel and Dawance-Goossens (2004).22 De Decker and Laureys (2007, p. 1). Since 1998 however, the number of dwellings managed by socialreal estate agencies (non-public actors offering accomodation at social tariffs) has increased with an averageof one hundred units a year.23 Noel (2004, p. 263).

234 N. Bernard

123

-

housing units per year, on average, it will take more than 15 years to complete the process,

compared with the 10 years initially foreseen. So, contrary to a commonly held idea,

everything is not always a matter of financial means. You also have to have executive

bodies that are effective enough to set up valid projects and ensure that they are carried out

within the foreseen deadlines.

Can this reluctance to build low-income housing be attributed to the lack of available

building plots as well? The argument is not very convincing when one knows that the

umbrella organisation when it comes to low-income housing, i.e., the Brussels Region

Housing Society, and various social housing companies of the capital (SHC, known col-

lectively by their initials SISP in French), together have a war chest of more than 50 ha

of land24 on which it would be more than feasible to build the 5,000 housing units

promised under the Future of Housing Plan with a not overly unreasonable density of

100 housing units per hectare. Yet very few low-income housing blocks are springing up

on this land. One of the reasons is that the public social housing companies have tended to

opt for more financially profitable operations with these vacant lots over the past few years

(outright sales, building of middle-income housing, etc.).25 That is why the Future of

Housing Plan did not want to rely solely on the SHCs good will.

Let us wrap up with the reminder that low-income housing is not always built in order to

increase the public supply. However, this is not a seeming paradox. So, Brussels popu-

lation decreased markedly in the 1970s due to the exodus of a large proportion of the

middle class to the citys green outskirts. Paradoxically, the regional authorities launched a

huge low-income housing construction effort at the same time. The underlying aim of this

at first glance surprising policy was effectively to generate employment and support the

building sector. At the time, no fewer than four out of 10 new units built were low-income

housing, compared with a ratio of one per 200 today!

3.2 The present

It is impossible to raise the issue of low-income housing in Brussels without examining the

Regional Housing Plan, which aims to build 5,000 housing units (3,500 low-income and

1,500 middle-income units). The stakes riding on this plan are high; this can never be

repeated enough. The building of low-income housing is indeed a truly crucial operation in

that it leads to two positive consequences. First, it makes it possible to house more families

in a by definition affordable public housing supply. Second, by injecting new units on the

housing market, according to classical economic logic, it causes a general downward trend

in rents on the private market because the supply rises compared with demand. Indeed,

Brussels Free University (ULB) estimated the critical mass for triggering this turn-around

in the rental trend at 5,000 units! Only the future will tell us if this research centres models

are correct.

Moreover, even if the Brussels low-income housing market is far from having reached

the level of discredit and disqualification of its French (and, to a lesser extent) Walloon

neighbours, it imperatively needs to have its image restored. This vast building plan givesit an ideal opportunity to do just that, and it is all the more important to seize this

opportunity as this is the first time since the Brussels Region was created in 1989 that the

Minister in charge of housing is now in charge of town planning as well. The main levers

24 Zimmer (2007).25 Lasse`rre (2007).

Good and bad fortune 235

123

-

of change are now in the same hands! No one could understand it if this historic oppor-

tunity to give Brussels social housing policy a salutary lash of the whip was not taken up.

Despite this traditionally glowing report, however, one thing is clear: The 5,000 housing

units will not be completed before the end of the current legislature (June 2009). Believing

otherwise is illusory. The authorities can assert all they want that the promise made during

the elections was merely to break ground on the 5,000 units. No one is fooled: The

governing majoritys official agreement does indeed stipulate the construction and

production of 5,000 dwelling units.26 It is of course a (very) good thing to know that

these projects are in the pipeline, as has been proudly announced, but they must above

all come to completion. The States credibility and the reinforcement of its legitimacy in

the eyes of the people (who, in a democracy, are entitled to call the State to account) are

both at stake. The public authorities will enhance their power if they recognise having

made mistakes, provided that they learn from these mistakes and do not repeat them!

On another front, the federal government has finally met a longstanding demand to

reduce the VAT rate on low-income housing construction via the law of 27 December

2006, which reduced this rate to 6%27 from the previous 12%. It is thus surprising, given

these new conditions, that the people in charge, whose voices have finally been heard, have

not taken advantage of this to raise the housing plans quantitative targets commensurately.

To this day, in any event, this excellent measure still has not had any impact on the

governments leading housing programme. Sure enough, the parallel rise of building prises

has not failed to absorb a part of the beneficial impact of this measure,28 but does not

explain everything. Since 1998 however, the number of dwellings managed by social real

estate agencies (non-public actors offering accommodation at social tariffs) has increased

with an average of 100 units a year.

Much has already been written about this vast plan to build 3,500 low-income and 1,500

middle-income units.29 In any event, there are currently 27 projects in the works repre-

senting 2,700 housing units spread over 11 boroughs. We can note that in any event this is

the first somewhat sizable low-income housing construction programme for at least the

past 15 years or so.30 What is more, this plan is all the more ambitious because it plans

(planned) to build 5,000 units in 5 years, whereas the mean public housing production rate

for all the operators (SHCs, SDRB, municipalities/boroughs, etc.) together is currently

some 500 units a year.31

Of course, the plan is slowly getting under way, but the rules inherent in public pro-

curement are by definition complex and thus slow to implement. In the present case the

Brussels region first had to find free building land from the municipality, then enter into an

agreement with the latter regarding the making available before calling for tenders for the

building of housing and, eventually, starting up the procedure for obtaining the urban

development permit (that requires a slow and patient consultation, notably with the local

residents). For the sake of comparison, private developers are much freer to act in that

26 Un avenir et une ambition pour Bruxelles, pp. 27 and 28, respectively.27 Art. 55 of the framework law (I) of 27 December 2006, Moniteur Belge/Het Belgisch Staatsblad, 28December 2006.28 Steel for instance, has seen its tariffs multiplied by 2.5 since 2002.29 See in particular Bernard (2006b, pp. 929). See also Bernard (2007, pp. 77102).30 Zimmer (2002).31 See the special report on Brussels housing policy in the magazine Art. 23, published by Rassemblementbruxellois pour le droit a` lhabitat (Brussels Union for the Right to Housing), Issue 15, AprilMayJune2004.

236 N. Bernard

123

-

respect and thus build more quickly. In addition, the prospect of the creation of low-income

housing has sparked a NIMBY reaction from residents in certain places, such as Molen-

beek, who are not always motivated by concerns for the public good.

But the main raison for the failure of the Plan is rather to be found in the following case.

So, while the plan relied heavily, at least in the beginning, on close cooperation with the

local authorities (boroughs) for the real estate aspects, the majority of the local authorities

did not answer the call, preferring to keep their many plots of land (more than 160 ha in

all!) for other, more profitable, operations. That is why the plan took care from the very

outset to pull in other players with land holdings, with a certain amount of success. Of

course, some boroughs (Watermael-Boitsfort and Woluwe-Saint-Lambert) already have a

close to 20% low-income housing rate, but others remain at desperately low levels

(Woluwe-Saint-Pierre and Ixelles/Elsene, with rates of 4% and 3%, respectively, bring in

the rear). These laggards must shake a leg first and foremost! They are already doing so,

in fact.

Despite these various explanatory elements, the slow pace of the process continues to be

a source of amazement, especially to the extent that the regional bodies are doing only

what is minimally required by town-planning regulations when it comes to holding

meetings with and consulting residents. Now, it is possible that slightly more proactiveness

in this regard might have succeeded in defusing residents sometimes vehement opposition

to projects in Ixelles/Elsene (mediocre architecture, vagueness about parking spaces),

Molenbeek (too many large units), and, to a lesser extent, Uccle/Ukkel (blocks of housing

out of scale with the neighbourhood and closed upon themselves, without interconnections

with the surrounding existing buildings). Of course, these reproaches were not all guided

by concern for the common good: For example, the residents of Molenbeek rejected the

large units above all to avoid an influx of families of immigrant stock in their neigh-

bourhood (despite the selfishness, along the lines of NIMBY, of this opposition, the

projects promoters gave in to it!). Nevertheless, sparking town meetings and consultation

upstream from the project is the best way to get the neighbourhood to rally to what it would

otherwise be likely to consider an invasion (of course, we are going to build low-income

housing next to you, but at the same time we are going to build an athletic centre, for

example, a day-care centre, etc.).

3.3 The future

Be that as it may, one must remain vigilant. A proportion of 30% large units (for large

families) was required by the housing plan. In light of the first plans, is this objective still

realistic? This reasoning also holds for the 70/30 low-income/middle-income housing split.

And the next instalment? Where are the remaining 2,300 housing units to reach the

target of 5,000 new units (which is not a sacred figure but should nevertheless be kept in

mind) to be set up? One good development in this connection: A study commissioned by

the Brussels authorities has just found that there are another 1,200,000 m_ of state-owned

land available in the capital. This should without a doubt facilitate future prospecting.

4 Conclusions

Given the number of people eligible for low-income housing who are nevertheless forced

to remain outside public housing for lack of vacancies (and who are thus forced to cope

Good and bad fortune 237

123

-

with the high rents on the private market32), the private housing supply must imperatively

be made financially accessible to people with modest incomes,33 at the same time as efforts

continue to increase the public housing supply. Private landlords are actually de facto

social landlords and, moreover, accommodate many more poor people than the SHCs

themselves. Yet rents are subject to practically no regulation on the private housing market.

It is thus high time to socialise the private housing supply, notably through social medi-

ation of the market (social real estate agencies, rents covered by rent control agreements,

joint rent commissions, etc.), in addition to building low-income housing. The people who

are affected by the housing crisis are doubtless less interested in low-income housing sensustricto than in housing of a social nature, that is, that they can afford. One can only hopethat the authorities have gauged the importance of this far-reaching change in society.

References

Bernard, N. (2005a). Renforcer lacce`s a` la propriete: un eclairage europeen et prospectif. Professionsimmobilie`res, Revue de la Federation nationale des agents immobiliers de France, 94, 1517.

Bernard, N. (2005b). Le regime fiscal applicable aux immeubles abandonnes en Wallonie, en Flandre et a`Bruxelles. Convergences et ruptures. Les Echos du logement, 1, 125.

Bernard, N. (2006a). La crise du logement: a` Bruxelles aussi. LObservatoire de lImmobilier (67), 3334.Bernard, N. (2006b). Le logement social a` Bruxelles: origines et perspectives. In En Brik? Le logement

public en question. Recommandations sur la culture de la qualite et la qualite des projets en matie`re delogement public (pp. 929). Brussels: Disturb. This text (in French) can be downloaded fromwww.disturb.be.

Bernard, N. (2006c). Huit propositions pour un encadrement praticable et equilibre des loyers. Les Echos dulogement, 1, 120.

Bernard, N. (2006d). Lallocation-loyer, un outil pour faire baisser la pression locative. Le Politique HS6,4048.

Bernard, N. (2007). Le logement social a` Bruxelles: origines, perspectives davenir et comparaisonseuropeennes. Les cahiers des sciences administratives, 13, 77102.

Bernard, N., & Van Mieghem, W. (Eds.). (2005). La crise du logement a` Bruxelles. Proble`me dacce`s et/oude penurie? Brussels: Bruylant.

Charles, J. (2007). Structure de la propriete sur le marche locatif prive bruxellois. Brussels: ProspectiveResearch for Brussels.

De Decker, P., & Laureys, J. (2007). Le marche du logement se polarise-t-il a` Bruxelles et en Wallonie? LesEchos du logement, 1, 120.

Demanet, M. (2007). La densification de lespace urbain par laction sur les proprietaires prives. In Produireet financer des logements a` Bruxelles (pp. 7381). Brussels: Atelier de recherche et daction urbaines.

Elsinga, M. (2005). Politique de la location et subside locatif aux Pays-Bas. In N. Bernard & W. VanMieghem (Eds.), La crise du logement a` Bruxelles. Proble`me dacce`s et/ou de penurie? (pp. 91109).Brussels: Bruylant.

Institut Emile Vandervelde. (2003). Etat de la question. Investir les logements inoccupes pour repondre auxbesoins en la matie`re. Brussels.

Laferre`re, A. (2005). Les aides personnelles au logement: reflexion economique a` partir de lexperiencefrancaise. In N. Bernard & C. Mertens (Eds.), Le logement dans sa multidimensionnalite: une grandecause regionale (pp. 140160). Namur: Publications de la Region Wallonne.

Lasse`rre, C. (2007). Reserves foncie`res et marches immobiliers: les mecanismes financiers sont-ils unereponse aux besoins en espace? In Produire et financer des logements a` Bruxelles (pp. 1935).Brussels: Atelier de recherche et daction urbaines.

Noel, F. (2003). Regards croises sur le logement social. In Le logement social au musee? De socialehuisvesting naar het museum? (pp. 120128). Brussels: Luc Pire.

Noel, F. (2004). Un plan de lutte contre la crise structurelle du logement a` Bruxelles. Lannee sociale 2003,263284. Brussels: ULB.

32 According to the Brussels-Capital Regions 2006 rent observatory, in any event, rents are rising markedlyfaster than income (p. 39).33 Thomas and Vanneste (2007).

238 N. Bernard

123

-

Noel, F., & Dawance-Goossens, J. (2004). Offre et demande de grands logements en Region de Bruxelles-Capitale. Brussels: Brussels-Capital Regions Advisory Council on Housing.

Observatoire de la sante et du social de la Commission communautaire commune de Bruxelles. (2006). Atlasde la sante et du social de Bruxelles-Capitale (pp. 6378).

Thomas, I., & Vanneste, D. (2007). Le prix de limmobilier en Belgique. Les Echos du logement, 1, 1831.Van Criekingen, M. (2006). Que deviennent les quartiers centraux a` Bruxelles? Des migrations selectives au

depart des quartiers bruxellois en voie de gentrification. Brussels Studies 1.Zimmer, P. (1996). Le logement social a` Bruxelles. C.H. CRISP 15211522.Zimmer, P. (2000). Dix ans de politique du logement social a` Bruxelles. Brussels: S.L.R.B.Zimmer, P. (2002). La politique de lhabitat de la Region de Bruxelles-Capitale. C.H. CRISP 17461747.Zimmer, P. (2006). La politique du logement de la Region de Bruxelles-Capitale. Les Echos du logement

(2), 1018.Zimmer, P. (2007). Les productions publiques: acteurs, ressources, production et reserves foncie`res. In

Produire et financer des logements a` Bruxelles (pp. 82104). Brussels: Atelier de recherche et dactionurbaines.

Good and bad fortune 239

123

-

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

Good and bad fortune of the plan for the construction of 5,000 (low- and middle-income) housing units in BrusselsAbstractIntroductionThe figuresLow-income housing supplyThe demand for low-income housing

The construction of low-income housing in BrusselsThe past (put in perspective)The presentThe future

ConclusionsReferences

/ColorImageDict > /JPEG2000ColorACSImageDict > /JPEG2000ColorImageDict > /AntiAliasGrayImages false /DownsampleGrayImages true /GrayImageDownsampleType /Bicubic /GrayImageResolution 150 /GrayImageDepth -1 /GrayImageDownsampleThreshold 1.50000 /EncodeGrayImages true /GrayImageFilter /DCTEncode /AutoFilterGrayImages true /GrayImageAutoFilterStrategy /JPEG /GrayACSImageDict > /GrayImageDict > /JPEG2000GrayACSImageDict > /JPEG2000GrayImageDict > /AntiAliasMonoImages false /DownsampleMonoImages true /MonoImageDownsampleType /Bicubic /MonoImageResolution 600 /MonoImageDepth -1 /MonoImageDownsampleThreshold 1.50000 /EncodeMonoImages true /MonoImageFilter /CCITTFaxEncode /MonoImageDict > /AllowPSXObjects false /PDFX1aCheck false /PDFX3Check false /PDFXCompliantPDFOnly false /PDFXNoTrimBoxError true /PDFXTrimBoxToMediaBoxOffset [ 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 ] /PDFXSetBleedBoxToMediaBox true /PDFXBleedBoxToTrimBoxOffset [ 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 ] /PDFXOutputIntentProfile (None) /PDFXOutputCondition () /PDFXRegistryName (http://www.color.org?) /PDFXTrapped /False

/Description >>> setdistillerparams> setpagedevice