GMT - Education Resources Information Center · Higher-Education Budgeting at the State Level:...

Transcript of GMT - Education Resources Information Center · Higher-Education Budgeting at the State Level:...

Eb 256 265

AUTHORTITLE.

INSTITUTION

SPO GMT_Pug

IOTEAVAILABLi nook

.PUB TYPE

EDRSDESCRIPTORS

t

ABSTRACTNew approaches to allocating state resources to

'colleges are discussed: Budgeting. and resource allocation principlesare considered that: (1) reflect the unique context'of highereducation; (2) are consistent with sound budgeting and managementprinciples; and (3) represent institutional mechanisms applied-at thestate level rather than approaches-developed expressly to reflectstate priorities. to form the basis for a set of first principles forstate-level resouxdb allocation,,the following concepts areaddressed: the link between budgeting, planning, and eccoumtabilitv,governance relationships; production functions in hj.gher educatios;and key structural components of the budget. The following customaryapproaches to resource allocation are evaluated in light of theseprinciples and guidelines: incremental budgeting, formula budgeting,base-plup-increment approaches, and categorical or competitiveapproaches.eThe changing environment affecting resource allocatioband actual and potential responses to the.problems involved.are alsoconsidered, including buffering and decoupling, marginal costing, andusing flied and variable costs. Finally, key recommendations aresummarized, and areas where reform of resource' allocation may' fartherthe aims' of schools and state government 'are identified. (SW)

DOCUMENT RESU14Er

Jones, Dennis P.

HE 018 331

Higher-Education Budgeting at the State Level:Concepts and Principles.National Center for Higher Education ManagementSystems, Boulder, Colo.National Inst. of Education (ED), Washington, DC.

400-83-0009120p.NatioRelCenter for Higher Education ManagementSystemi, P.O. Drawer P, Boulder, CO 80302 ($8.00).Viewpdints (120)

MF01/PC05 Plus Postage.Accountability; *Budigetingi College Planning;Economic Climate; *Financial Policy; Governance;*Government School Relationship; *Hither Education;*Resource Allocation; *State Aid

.

44,

**********************************t*************o*********************** 'Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made. 'It

from the original decument.***********aW**********************************************************

"PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THISMATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY

TO NEEDUCATIONAL RESOURCES

INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC)."

010,ANTINENT ay lawmanNA AL INSInian Of tOtiCA

EOUC tONAL RESOURCES MIFORASIVOtiCENTER (ERIC!

ho document has rbotro ssproCksosst ssreceived hom rhe mown w orgonizstionorsosorog ttWhom changes have boon mode to Improvereproduction wetly

PIntlel vtew or %morons stated at Mrs dew,moor do not nctosney tooresont othcolorsairoo of poiacp

t,_

National Center-for Higher Education Management SystemsPost Office Drawer P, Boulder,-Colorado 80302An Affirmative Action/Equal Opportunity Employer

_The mission of the National Center for Higher Education Mamigement SystemsiNCHEMS) is to carry out reseaki development, dissemination, and evaluatidnactivities and to serve As a national resource to assist. individuals, institutions,agenc;es and organizations Of Postseeondarreducation, and state and 'federal'goveriments in bringing about improvements in plarixiIng and Management inpostsecondary education.

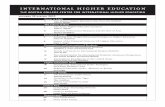

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

(.1totrtrtonRiched, L.-van HourUniversity of klinston-LT niversity Park

Arthur G. AndersonIBM Corporation

Richard K. GreenfieldSt Louis CommunityCollege District.

Kermit HansenFinancial PerspectivesCompany

David F. johns4nNatignal Institutes of Heahh

*jt)e E. LeeSK ht an Miloagencn tinto 1porateti

Ben Lawrence'President

Otairman-ElectSherry H. PenneySUNY-Central Administration

Kenneth P. MortimerThe Pennsylvat* StateUniversity,,,

Chahners Gail NorrisUtah Slate Board of Regents

James I. Spainhower.Lindenwood College

Joyce TsunodaUniversity of Hawaii

Hon. Gordon 0. VossMinnesota Slate Representative

Marvin WorkmanTemple University

OFFICERS

Sherrill CloudI

Vice President forAdministration and Finance

William Tet lowDirector,

Management Products Division

KAI. WatsonPioneer Corporation,Retired

EX-OFFICIO MEMBERS

Elaine El-KhawasChairNational Advisory CouncilAmerican Council onEducation

Charles M. ChambersChairman:ElectNational Advisory CouncilAmerican Association ofuniversity Administrators

Dennis- pilesvice President for .

Planning

Ellen ChaffeeDirector,

Organizational Studies Division

BUT COPY AVAILABLE

to

.4

a

Higher-Education Budget*At the State Level

Ccinceptd arid Piinciples

Dennis P. Jones

1984

Nstkmal Center for Higher E4peation Mangwanegt SystemsPAX Drawer P ". Bouldeis Coles-ado 80302-

Aflimk;tivo Action/Equal 04;portraty &cloy,

4

"

The work upon which this bliostion is based was performedpursuant to Contract No. of the National Institute of.Bducation. It does not, hovever, necessailly reflect the views of

ThataSencY

This publication was not printed at the expense federal

government

National Center for Higher BatucationMansiement System'sBoulder, Colorado 803C0 .

the United States of AmericaDesigned by Lynn B. fl4lips '

r

Thble of Confents

Acknowledgments

avoter 1The Future of State Funding

r

,Cha2tw.. 2Ile Budget in Concept and Context 11

Chapter 3Customary Approaches to Resourc Allocati 41

Chapter 4Budgeting in the 1980s: Responding toNew Realities

I Chapter 5Budgeting and Educational Policy:Conclusions and Recommendations 91

Appendix 97

References 111

1. Short,Circulting the Budgeirrocess . '" 19

Z. Govettumelatkurships . 26

3. Iurs of " *the Process 314

Budgetary CoinponentiV

5. Custmnary Approaches to &WWI*AllOattkin 42

6. Average versus Marginal its *1 53

7. State Allocations Linked to a MulliyearAverage of Enrollments

8. "trading CeilinpDuring-Perkxls of--Enrollmant Growth

9. Minnesota's Enrollment Buip Policy ........,..

S

4

W.-Marginal-Cost Curve Over. a Wide Rangeof Enrollments 79

11. Fixed and Variable Costs 4, # I a. 81

%

a

.

1. A Menu of Menial State ObjectivesRegarding Higher Education . . OOOOOOO 20

2. The Infhience of Governance RelationtiiipsFinancing, Bthigeting, Accountskbility,

3. Summary of Budget Formula.for HigherEducation, State of Kentucky, 1983

4. ynrifirsity of Wisconsin Systems, Fixed-CostAnalysis, Instruction; Base Year-19780.. 164\

5. Marginal-Cost Factorb

a4

AP

In

I 6

,

cknow nts

In developing this document I benefited from the Ideas dadassistance of frienas, and colleagues around the country.: Toeach of them I qwe a particular debt of gratitude. Rich Om-provided 'the, impetus, for the effort and offered manyvaluable comments alms the way. Paul Brh3kman's nearbyoffice made him a victim of my frequent need to discussideas, both conceptual and technical. His unfailing goodiraaq allowed me to benefit from 1;oth I" and his

Bill Pickens contributed his . his experi- .

ence, ; 'copies of- many pertinent papers "" his file's.John Folgt`ff found time at numerous = 4,1 tolisten to.my ideas] offered his own unique blend of academicand real-world perspectives,. and subsequently reviewed thenumerous drafts. through which this document passed.Brenda Albright,' Gail Norris, Bill Fulle4 and Mice Mullenprovided encouraOmei%t wilt as substanthe commentsduring this period, With skill, craftimanship, and patience,Rolf Norgaard transformed the draft into a final product. I,Paula Dressler typed the domain* over and over aiptin withgood humor and style. Clara Roberts otersaw the productionof this volume: with 'help. froth Linda Croom, Lynn Phillips,and Mary Hey. I hope thilbook reflects y valuable.contributions.

S

The Future o State Funding

4

James Thurber was fond of saying, It is better to know someof the questions than all O. the answers." Adopting hisadvice, this volume step,back frop annualattempts to makethe numbers come' out igght and considers instead basicquestfons about state funding of higher education. -

Budget cycles turn as inevitably as the lesions. itelent-less and swift, these revolutions on the fiscal treadmill com-plicate the already difficult task of finding suitable rerconsesto thy needs of higher' More importantly, changingcircumstances have rendered many customary approachesto resource allocations inappiopriate. The needs of statecoll universities are clearly different today than theywere in L e 1950s . and .1960s. Moremer; the state's owneducational requirOments 'lave changed as a new generationof students prepares itself for working and living in an infor-mation society. If new answers are needed, we must firstremind ourselves of the questions. Then we must frame our

uses within the context of basic concepts and principles.can assist us in forming educational.and fiscal policies

appropriate to the 1989s.This book represents an attqmpt to get hack to the basics

on the topic of state financing in higher education. 'lb do so, .

"'must clear much of the conaptuikand rhetorical under-brink that has accumulatid over the years We must review

A

1. 01.

-s,

2

a,

the wealth of experience that states have in financing highereducation an tamable how wtcan better tap and,utilize it.Some experience consists of the perstpial knowledgeaccumulated by indivichials responsible for recommendingand- insplementing new mechanisms for resource allocation.Mich of the literature dealing with state financing of highereduCation consists of the documented experience of others.The most frequeitly cited writings are all descriptive innature (such as Miller 1964, Gross t973, and -Manny 1976).Those writing's that diinot inflect pertonal sotierierite5or pronvide descriptive accounts arc irfeyitably hcntatori in nature.They extol the virtues of one particular method or urgetheadoption of a.particular point of-view. What is missing is afuridamelsta4 conceptual basis for arpnizing thiS exfai-ence. We must be able to juxtapose and compareapproaches.It is crucial that we identify .which approaches are similar.-at heart and which are based on dramatically different setsof assumptions. Likewise, we 'must recognize the,

features of varioulapproaches and understand the context inwhich they are being employed. -

Three. perspectives inform, our consideration of state-level funding of postsecondary education. The erst concernsthe diversityand complexity.of higher education itself and ofcurrent mechanisms for allocating resources within theenterprise. We must recognize that we are spealdng of .3,C00unique invitutions. While colleges and universities havemuch in common, they are 'clearly different from each otherin important ways: The resource-allocation mechanifinsthrough winch they acquire their funds are sirailarly diverse.Examined closely, the funding process consists of myriadindividual decisionth arrayed in complex Ways by a largt andcontinually changing Cast of eharaclers. iltagetary decisionsare never, exactly replicated. from year to year, much lessfrom state to state. lb some degree, this diversity is bothwarranted and healthy. Not only must resourceallocatiftsprocedures reflect the unique context of higher education,they must also take s = account specific institutional andstate concerns e with time. Nevertheless, if wewish to discern basic = r. and principles that inform the,funding process, we must 16, beyond this complexity. In'

a

4

these pages we address issues cominon to all states-andpublic institutions, without overlooking necemery:,clistinc-

. tions oiforming unduly broad generalizations.The second perspective that informs this book concerns

the importance of. recognizing sound budgetintprinciplei.. These principles argue that.thebudget process la more than a

indans of allotting resources; it is also an extensitur. of theplanning process and a framer of accountability. Withoutadequate planning, lesource allocation becomes nonpurpo:sive at best. Likewise, *aecolmtability mechanisnis normallyconsideied to be an integral part resource allocation areeither missing from, inconsistent with, or coutderproddotiveto many state funding sthemes. Our discussioh seeks togenerate some "first principles forum by those developingand implementing new or modified procedures for resource°allocation that reflect. sound budgeting procedures in othercontexts. .

This discussion of state fu 'n'clinig of higher etlucaticurdiffers from others in a thiiclerespect. We. view the processfrom the state perspective. Approaches to resource alloca-'lion hfve most often been developed froin an institutionalperspective. In other words, they represent institutionalmechanisms applied at the-state levetrather than approachesdeveloped expressly to reflect state prioritiei. It is littlewonder, then, that institutiondl and .s level admini&tratori seem to clash incessantly over the operational details .

of running colleges and univa, . The ineaanisn2s put inplace to guide the state -level resource- allocation processinvite state -level decisionmakers to treat, as policy variables,items that would otherWise be considered well within theManagerial prerogatives of institutional administrators. Thisbook adopts the state perspective for several reasons. -.Theview of state government is crucial because it is the locus ofthe decisionmaking with which we are concerned. Whetherby design or by default, resource-alkcation meclianismsreflect statepriorities and.educational policies. We take thisperspective not to the exclusion of institutional interests, butas a necessary and inVortant corrective to our customaryunderstanding of resource allocation.

3

4'This book speaki to the needs of public higher education

in. the -1.9130i. ,New circumstances, however, skald rugneceissrily force us to or embrace radically different

a approaches, Rather, m reexamine What has come to be; viewed as stdhdard practice anti-modify these aPproaches l .,

but important ways:k/hat is calledlot and whait thisvolume hopes to provide, is a set of ,concepts and principlesabquystate-level budgeting and )-etource *claim that:

1. Reflects the state perspective lbut,not to the exclusionof Institutional cnterests)

'2. FroceOris firm and is consistent with sound principlesof b a': and management. . ,

3. D -the_ pppEcation of that basic principleiwi 41 the unique context of education

!iv

.WatUng t, these three perspvti'ves,` 410..caii, de-04 acoherent and conceptually sound picture of two relatively

r independent entidepostsecxindary institutions and stategovernment---bound together by a series of relationships thatextend beyand hula* to include governance. 6vice, andACCOU*Obilitit. 1 -

Publi4postsecondary education is r thuch a matureof state -virnmettt. Just as national defense is .recognized asa- function of the federal government, and elementary and

. secondary education- are generally Connidered communityconcerns, the governance and finance' cd Public highereducetion reside with the state. The relationship is nbt

. sive. The federal gofernnient -and, in some, slates," localgovernments do. contribute' to the aping operation ofpublic postsecondary education. Students,, too, contribitte a

' collectively significant "share. Newt theless, the tesixnsi-bilities of guardianshiplie-with state goirernMent.

Two facts Eeveal the strength And importanix% of thisbond. First, state government is by far the 'dingle: Writsouree of support for public colleges mut universities. States

I contribute abOut fi0 percent of the revenues that stipPottpublic highehducation'e instructionaland geziend expendl-turn. Remove the revenues constminell to supportresearch,

- and their shire escalailm to almost lo jereent. Second. the

v.

$

4

* ,share of revenues that higher education receives fromgeneral state funds typically rant second only to those allo-cated to eyinentary and secondary education. Clearly, state %...government4has an important stake in its educational institu-tions; these institutions, in earn, look to the state for theirsupport.Thqtfles are of mutual interest and benefit.

The basis gthis relationship financial supportmakesfo)kan association not onli close and strong, but oftenfrustrating and sometimes contentious. Because higheredliTtion receives a lion's share of the state budget, its con-stantregquests for more resquices often ring more hollow and

'strident than true. On the other hand, the state is tie primaryguOrdian of its colleges and universities. Advocates of highereducation muit of necessity look to the state not only forsubsistence bur for a reasonable quality of life. Inevitably,squabbles over levels or support and Organizational life-styles do occur; Such eruptions are seldom irc the belt inter-'

"eats of either party The, esteem and credibility of both are tooeasily diminished When inherent conflictsarenrt Inanagedand contained. Like nuclear fission, reactions can be a forcefor good if they are prdperly channeled; unconstrained,these reactions can become destruptive.

Recognizing, explibitly or implicitly, the importanceof keeping their give` and take within bounds,' both partieshive 'devised ways to smooth the aflocation process. Themating dance, in short, has been ritualized. Name states,approaches have become standard operating procedureswithout .a clear lind explicit agreement' the system' has 1-rassumed its present shape by precedent alone. Precedent; forexample, can lehd to the unquestioned assumption that last %year's allcatipn becomes the base from ('hick to calculatethis year's increment. Mechanisms fot special requests doxist in nearly all cases, but ,the bulk of the allocation is

determined through procedures with wflich participantshave grown comfortable over time In other states theseunderstandings have become codified in the form of 'budgetformulas or other structured guidelines. In these instances,the, key factors that enter into budget calculations are re-.

duced to explicit formulas through a negotiation process.

as

e A

6 a-

Slier the years; state goverpnient and public posrsecond-

- ary institutions have achieved reasonable stability in theirrelationships. All parties involved halve tacitly recognizedand accepted the process by which funds are requested andallocated.. Consensus has also existed regarding whichfactors would be considered when adjusting allocations fromone year to the next. This stability, however, is crumbling.Cuktomary practices ke falling victim to changing links andnew priorities. In some states these changes are gradnai,alters, precipitous. The immediate cause is economic: Staterevenues are not expanding at a rate commensurate with theneeds of higher education. Theseievenues are limiter) eitherby a shish economy or by fundsinental social 'shifts that-have resulted in either revenue reductions or caps,on therate of expenditure growth within the state. samples in-clude California's famous 13 and its variants inother 'stales. Although now less 21. pant, inflation has alsowreaked havoc. It has often effectively transformed what-ever increases have beei2 granted into q net loss.

Economic condition0 have iilso forced varictus *tatepriorities into,sharper focus and, at thries; into direct(=Oct.Qften mandated by a leeslative statute, state connnitnwntsto elementary and secondary education, welfare, and otherprograms have been maintained at the expense Of highereducation, Not only is the fiscal pie' getting smaller in realterms, the sizes of the pieces are changing. At best, high&education's portion is staying conetant In many states,however, its share la clearly decreAsing (McCoy and Halstead19841. This has prompted many state ,and institutional

for , acinlinistr,itcrrs to trade In their pie cutter for the finalhatchet. few ,energy-rich states have been spaied thfse.strictures. Many states,- however-rare heiniforcedto changethe ground rules-that govern the process by which statefundi are allocated to postsecondary institutions. s

The changes being made or proposed take many forms.This reflects different state practices, unique coixiitions intheir external environment, .antithepolitiial and economicconstrOnts-that dictate' *hit change is possible. When dif,ficulties are not acute, states favor' modifications to theircurrent approach. Their first inclination is to give the old

4

machine a tune-up and hope it carry them-through imemore budgetary season. Some states will fund their "poit-secondaq institutions at a percentage bf the f9rnmla or willallocate4unds to yield only a constant share of the fiscalpie.Those states facing relatively small revenue limitations canafford to tinker with the existing resource-allocaildh machin-ery and.fet it to work under somewhat altered condition.

Some states, however, are forcedor are Willinglychoosingto consider fundaniental kid radical changes in

. their funding procedures. Moreover, some that have made atseries of Ma:entente' changes in their appsoaches now findthemselves with badly flawed or unworkable akninge!nents.Funding. at a "percentage of formula" catle be a reasonableshort-term solution to a fiscal problem But if the solution isrepeated over a series of years so that instituthins are fundedat 60 or 70 percent of the formula, then we must question thecontinued desirability or even viability of -this approach.Continued application of gand-akis will not result in a cast,the kind of solid support needed to remedy today% problems.A few states are being forced to make more radical changesbecause of precipitous and pot I laver* dadines intheir economic fortunes; Even if economies Aboundfully, pent-pp demand for state resources will create analtered fending environment that can't help but affect theprocess for many years to come.

Finally, many states are rethinking, in whole or in part,their approach to resource allocation. They are not promptedby., economic neceisity alone, but by the recognition thattheir funding mechanisms are no longer synchronized withstate priorities. Be they formula or incremental approaches,funding mechanisms are devices for bringing some measureo certainty and stability to resource allocation. They are notgeared to respond to rapid change or to reallocate fundsswiftly among shifting state priorities. Change, however, hasbeen the-hallmark Af the. last &cede. Many of the resource-,allocation mechanisms now in place were developed at a

. time when the baby-boom cohort was reaching allege age.At that time, the primary state objective was accommodatingthe horde of new students. Clearly, condition; and objectiveshave changed. Enrollments are now increasing if at

a

8

4

all. Ibday, states are more concerned with maintaining thequality of their institutions and promoting the economicdevelopment of their region than with expanding theircapacity to serve more students.

The above reasons indicate why approaches to resourceallocations are In a state of floc.-Administrators at both theinstitutional and state levels are exhibiting considerableinterest in new approaches to their budgeting probIdeally, these approaches will adconlmodate their chancircunistances but will not require them to abandonprinciples or priorities. Although the need to changeapproaches is 'widely accepted, little guidance forsafely navigating these uncharted waters. As a con.seirence,administrators recommending changes can be expected torely on a dustrinanuitrategy: borrow the basic solution fromsomeone else and accominodate local, idiosyncratic concli

. tions by modifying it over time. This was the method usedby many states in the 1950s and 1960s when incorporatingfunding formulas into their resource-allocation process.Note, for example, the plumber of southeastern states thatborrowed directly or. erectly from the 'Dues formula andthen modified that f ; twit their particular needs.

This "borrow and ;,. pt" strategy has, however, severaldrawbacks, First, it requires some states to innovate, to take,that initial, risky step. After all, there has to be a bandwagon

'before anybody can clamber aboard. Several innovationscurrently meet this need. For example, Indiana has adopteda nugginal-cost approach and Wisconsin a fixed, andvarigle-cost approach. Tennessee has initiated aperformance-funding program for promoting outcomes con-sider:.. important from the state perspective, Colorado's,"M 4, urn of in importantways the relationship between statirvernment and state-supported colleges and universities. These examples'illus-trate that innovative responses ire emerging that addresschanging economic and educational conditions. It remains4obe seen, however, which if any of these initiatives provesitself w y of widespread emulation. .

The drawbick to the "borrow and adapt"strategy . 1 ves from applying someone else's solution- to

17

yOur own problems. A budget is a means for impleirientingapolicy. History suVgests, .however: that it is all too easy tobecome preoccupied with' the means and lase sight of thi''policies.and priorities that lie at their heart. Before a stateshould adopt anther's procedures,' it is essential that itunderstand the key policy implications of that approach.Surgeons, for example, have learned that when transplantingan organ from a donor to a recipient, a long list of specialconditions must) prevail. Likewise, administrators mustundersiand the idiosyncratic conditions that preiail beforeresource- allocation approaches can be successfully trans-planted from one state to another.. Without such an under-standing, the transplant snag be rejected, to the discomfortif not the peril of the borrowing state:The potential forrejection is exacerbated -when we ignore whatever crudeunderstandings we do have in the rush at* change pro-caddies. Progress by trial and Fir& can evilly turn into noprogress at all.-

The third limitation of this strategy lies in ale fact thatwhile it is easy to borrow, it is considerably more difficult toadapt. Whatever the:current bhdgetary practice, one can besure that it evolved to its present state over a period of time.One can also be sure that this evolutiorf did not occur flaw-lessly. Few participants familiar with the resource-allocationprocess are without tales of a procedure or a legislative provi-sion that did not become a mild if not unmitigateddisaster.Borrowing someone else's solution increases the need forfield modifications and, consequently, increases the proba-bility that significant problems will emerge.

Mention of these drawbacks is not intended to argueagainst change; change is not only inevitable, but necessary.Rather, it is intended to argue for informed and consideredchange. If we are to develop new approaches to resourceallocation, we must first ensure that they are grounded inappropriate concepts and assumptions and reflect soundbudgeting principles. In short, this book argues for a returnto basics. The'next chapter deals with several key conceptsthat can form the basis for devising a set of first principlesfor dtate-level resource allocation. Concepts given closeattention in chapter 2 include the link between budgeting,

9

11

a

ni,14 '

10

f

planning, '"andtaccountability; governance relatiOnships; pro-duction functions in higher education; and key structuralcomponents of the budget. Chapter 3 deals with customityapproaches to resource allocation, evaluating them in light ofthe principles artd guldillines presented in chapter 2.

Chapter 4 describes the changing envionment that isaffecting resource allocation and, in (ton, discusses actualand potential responses to these psoblema. bang on theConcepts developed in chapter 2, the fourth chapter assessesthe strengths and weaknisses of current efforts to bringresource, allocation in line with today'seconomic and educa-tional realities. No attempt is made, however, to inventory allcurrent practices or to report on the latest happenings inhigher-education budgeting at the state level. Chapter 5 sum-'marines key' recommendations and identifies thaw supswhere reform of resource allocation may further theaima ofboth educational institutions and state government.

With thi exception of the final chapter, an effort hasbeen made to avoid prescription and preachment. 'The bite*of this book is to logically develop a conceptualwithin which funding itreclianisms can beevaluated. Above all, it is hoped that the concepts. presentedwill help administrators in state government, legislativestaff, and executives at colleges t and universities to ilevelorarrangements for resource allocation, planning, and account-

,. ability that are appropriate to the 1980s . If these arrange-

-ments are to be successful, they must simultaneously servethe priority needs of the state, recognize key institutionalobjectives, and accommodate the economic realities of ourtime.

11.:01 :3 9.1

19

I 0 - 1

I 1,t 14 4

4 4.. 0 11 .11 :4- : - 4 - 1 1: 1 .1

11.1.41 1' .4 II . 1.1 1 4 ILL.m.....,11 1

-. 4 I - : 11...),.... .1 4.4. I 111.t 4. 4 4.0i ti .1 ..1; -.40 CI t:4411

2 1 m _ 1,: 1 111 k a l I .2 , 1 t 11, e II . -,,, cc,, 1,.,,,,..)_L.,

M- a 411.4,18 ,t -,1: 1 I 4 : t. 1

If 4 10 4 4 1 I. II 1 .4.1 : 11 1 . 04 .+1 .14

...: 10' I .., Ill 1 11 ) ' 4A, 14 III 1.1414 : 4 10 4 11.:.

* 311, )1 . t . 1...s:42 .. i..., 5 / ...-...5.1. it ""S: .11 t 4 1 Ai - .11:4-1, .4; I It 4,1., 4 4 4,: 'NI , : I 1 41,.. :.1 Or.A13.4 I ,

: 4 -4 $ t : 1. 41._,.11.4 1 1

44 : .44 11 ...., : DLL, 11.100: 4 4 luiLLI 10,.....4 5

* : : - I 1 ...11 ,+4 4 .. : .... 1 : Ito,. e I:1 e

411

1 '

D 1 : 411 .414 . tp

1

. ,4.: ..1 l .1 ;4.

1/1-it! 4 . 11 :

.1 -1 . l 11 11 : txa , ' 4. / If

4: 4 t .4.4 1 .14 44 14: it.: 0,..... ..1 Ir. 1 4.1

* : 0 : ial...44 4__1421. . , 4 ... 14 ..... t I., tle. 141 .... e ... I 1)11/: f, ti-

...if 14. 4. 9 i 14:7 111 1 , # A,. t '1 A,14* 1. 1 V43 -.lot ,,..44.4..: 1 1 4.4 /4: t .... .434..... 11 -.

12 .

r

financial exercise that starts and stops with the bottom line ofthe appropriation; its point is reduced to djvAring up the pie.

Unfavoiable economic conditions only reinforce thisperception. State legislators become preoccupied withsqueezing morkrevenues out of an already burdene# systemand cutting all tions in discretionary areas of the budget;They wish to mike ends meet, as indeed they must accord-ing to nearly all state constitutions. When tides of red inkrise, legislators and state administrators can-easily lose sightof other functions of the budget. These functions are notsimply supplemental or auxiliary. Rather, they invest thebudget ini process with meaning and purpose. That thesefunctions are often less visible than the bottom line does not

- negate their presence or importance.If we take a step back from the numbers, we come to

view the budget not so much as a docurnent but as a process.For examplb, Peter A. Pyher 119731 considers it as part of anintegrated system that includes planning as well as budget-.frig. While planning identifies desired **outs, budgetingidentifies required inputs. Reginald L. Jones and H. George

'tin succinctly characterized the key features of thesystem:

A budget can be regarded as primarily a plan or goal orobjective, 'and we know of no better definition of bud -feting than to say it is primarily a planning and controlsystem. Each word in that definition is important for a

. full understanding of budgeting's proper role. The plan-ning and cordibl aspects relate to the fundamentals ofthe management process. (1966, P. 141

Even this somewhat technical definition does not embracethe full substance of budgeting or reflect its broad impact. AsAaron Wildaysky correctly points out, budgeting cannot bedisassociated from its participants:

Budgeting deals with the purporles of men. How canthey be moved to cooperate? How can their conflict&beresolved? . . . Serving diverse purposes, a budget can bemany things: apolitical act, a plan of work, a prediction,a source of enlightenment, a means of obfuscation, a

21

13

4mechanism -of control, an (gripe from restrictions, ameans to action, a break on progress, even adkrayer that ,the powers that be will deal gently with the best aspira-tions of fallible wen. [1974, F. 3DM]

This book will not attempt to unravel some of the moremetaphysical implications suggested by Wildaysky.. How-ever, sefend functions of the budget suggested in the abovequotes mtlsi be kept clearly in mind when we discussapproaches to resource allocation.

Linking Intentions and Actions

A budget's primary function is to span the distance be-tween intentionand action. It is the device by which a statecarries out its/plans and by which it signals its priorities. Weshould Irma/Ithat states do support higher-education systemsfor reasons other than habit. Some motives are highly amorrphous (an educated citizenry will enhance the public wellbeing), while others are very specific (state economic growthdemands the availability of continuing- education programsf9r engineers employed by area industries). More often than

these priorities and purposes remain impliFitat best.They are neither written dowrrnor agreed to by the principalparties. Frequently we can only infer the interests andmotives that the budget process harbors. Ibday's hot issuemay receive attention, but rarely is it incorporated into alonger list of purposes that may be equally importantt-if lessflashy.

These priorities change over time, and legitimately*.Indeed, they often change faster than the budgetingmechanisms put in place to finance their achievement. As aconsequence, operational priorities are largely determinedduring the budget process. The budget can become, in fact,an ad hoc surrogate for careful planding. Because the processof allocating resources recurs every year (every two years ina few states) and because it has a direct and dramatic impacton institutional operations, #

ably responsive to the signals thattors, re: F :4

erstand-"" that pror:$$$ throughcess. Indeed, the budget is the. , k$.;. $

140

which `states can reward and grant favor in tangible ways tostate organizations and their employees, Other control 0

devices, such as laws and regulations, constrain or punish;they are not designed to provide incentives. The power of thebudgeting process to capture the attention of insfitutionaladministrators is further heightened in those states wheregovernment, through hmd:Ing or stareory 'control:14 is clearlythe dominant external constituent for the institution; .

Because the bUdget and theprocess by whichit is deter-mined exert 'considerable influence, statepurposes reflectedin them are also given tacit or explicit prioiity. This pohitreceives far too little attention. Whed'all eyes concentrate onthe bottom line, it is easy to ignore the incentives and signalsbuilt into the process by which that bottom line is reachtd.Cynics may nat'be alone in arguingihat no state priorities arereflected in the budget, save perhaps operating efficiency orthe limitation of expenditures. However& be it by design oraccident, consciously or unconsciously, values and prioritiesare inherent in the budget and the methods used tecalculateit. These priorities may not be the ones that state offiaialswould chomp isyere their decision explicit and conscious, butthat does not negate their presence. How many state legis-lators, for example, would argue that their priorities are todiminish educational quality or boundlessly expand accessto higher education? And yet, incentives for exactly thesepig-paws are incorporates into most funding formulas. Thisis i*ot to argue that formulas should not be used or thatformulas as we have come to know them areiwrong. Rather,it is to call attention to the fact that procedures for calculatingbudgets are not value free. That these values are implicitrather' than explicit or that they weien't considered whencalculation procedures were devised makes them neitherneutral nor inconsequential. Once put in place,Nhese proce-dures will be used and interpreted in such ways that allow'institutions to maximize their revenues. This being the case,it behooves the state to consciously choose allocationmechanisms that reinforce institutional behaviors con-sidered most desirable.

Being a isxidike between intentions and actions, the bud-, get process can collapse a distinction that is vital to maintain,

23'

0

. 15

that betwee'n procedure and policy. Because state prioritiesare rarely made explicit, the usefulness of.thebudget as a toolfor state policy is severely limited. In the absence of policyobjectives, budgeting procedures take the upper hand. Thisresults in entrenched bureaucratic structures uninformed byany clear strategy. If budgeting is to promote, not hinder,educational policy, administrators at both the institutionaland state levels must consciously review not merely themeans for financial support but its ends.

Planning

Planning, the second key function of the budget process,,is the way we can consciously choose desirable ends. It is anexercise, however, that most states readily confess that theydo nut undertake. Some states still develop. and publish five;year plans for their colleges and universities. These plans-;however, almost inevitably represent a summation of institu-tional plans, not state objectives. Moreover, they offer lessplan than prediction. They calculate future enrollments andthe resources required to serve them, but fastidiously avoidany corisideration of educational policy. There is littleevidence of planning being used at the state level to proposeand then achieve a desirable future for higher edtication. Atbest, planning has been an effort to document an expectedfuture.

Although considered lamentable by many, this lack ofplanning is in some respects understandable. State govern-ment is not a monolithic entity. By design, policies are forgedin a political crucible. This makes any agreement on desirablefutures very hard to achieve. State officials, legislators, andcollege, administrators must confront legitimately differentand -strongly held views concerning "what ought to be"when trying to envision the future of public postsecondaryeducation. Since confrontation is painful, even politically dis-advantageous, it is often studiously avoided. This representslesg a tendency toward open compromise than a tendencytoward obfuscation and generality. Instead of achievingresolution, those inholved in the planning procels seekagreeable phraseology. Golden prose is written about the

4

.

1 :)I t: I I iaTt'a V. .

10 t^ I :it: ..t 1: . a . ,

4 lit.. : . 1

:I : a :a to 1 4 A": a al : (a - .a ' , * vil $ a a

1 a1 . a - M e l i a : 4 0 :-. 4a : 11 ::6 : a

1 :4 ot. - .14.4 47-: 14 1 Ara t : 5 -r . . .

1 at 1 .

a 11 a. 141. , 4 . r i1 :,-t a - ' 1 i,..'14 1 Z .

a . ' ere 0 I _ : : a 4 ' a is : . r t ;-,. I : : . :.*

. A - 7 - i i 7 i 1 a . 1 a - a t t A 4 a 4 . : , .

4 . ,

: -

0 : 1 ,

6 6 6 : : 1 - 1 4 - . 6 : _ .

sok 0 tt t 17 : a 0 s _ e t;

. ,t at* _a al. Artaast , a : 1 a

. a 41 4 a a 1

: ,- 1. lilt. 1 flat ..-.10 -: 1 Ii"-1- # a A a .

a ; a *it : a t : -

it :a a .1 a ., ' ii F-* a a a: II 4 : . is a : 3- a r . .

a a

,-) _

4 1 : 4 :-.--k:7-4 at . a #

. a

. a - t s :r

a , t a t :r t all : -.± a a i (a -

:41 - = 't t

a i . %-.:

. t,t . :-11-1-_- a t ril-F a n: a a

a . ' .: : : a a a ,- a _ IA :771« a _

: - it

a 1 a ' -1-"ail .

1 .

:I i It : : a Tall 1 1 -

-,: a a 1 a : 1 64 4 - a .

11 - .

l'a . :

a a a 1 a . :d: ea i Yi a a: FeT.T.' 5 :- a Iv _Is a : a

(4164a1. : 1 - 4 1 it Are i r...c p. a I 1 agei- ,. a tom a t

a I 6 4

:ft ,

1 a :Fit' : lirTa '61-4kivt-v `a : s ks ".5 it : 4.4

1 I '4 .1 16-111r1tr a 61 04 : 1 .

a

a I` 1 Fa`i t o :;^IISt4.47.-r :ft ir./47:ra i a a el, a

. a 111 : s SI' ' it a.t ; t

114 a. a a : 11 'a a i" . AI

a 1 ' a a a 4 4 11 4141t 1 1. I a :

1 ti : Os 1 a a- I 1 ,

a I- II a t °"$. ;

s .- : . ' 11 1 a ' el .: . ? 'a : .

6 Srt.' $ r$71Ft as, -let: 7.-`15 ..I i t : I a t ' - r .

s 1 I' a a .

`1, 1 a :lb it i i 1 :

.:' a , a

- : . tTTt'i . ,-, a Vs a 111:

1 t '4 "'it Sr! II 0 a ili : S --1-.ST'...nit." - - il,''Fer t I 'frit

- Ft. * -I Tali ,- t`i . a 11 ,

a .-: - 4 :;-t-ri

. ' : 5 1 4 - t -:1r,IF: : 1 - 1 1 t a a -1-Fir: a r a t al .

a

, a' i . ..: I te';':-41 i' a : .

:).

.. I . 11 - 1 11 % ' 1 re. a"... 1

. 1 a: a I : : a .; I . I

1I a . a .

,-Z-it a . V7:4..:'

, 1 T 4 a -7-11: a a :2.: a 171-16

. ., a

i - : a

area). In such cases, the accountability or performanceclIttanumbers of degrees grantedmust- be submitted

before the next allocation can be calculated.Such a clear relationship between planning and account-

ability is the exception; not the rule: In the abseice of directcorrespondence, the common, tendency is.to frame acqount,ability issues in purely financial terms. Institutions are heldacZountkb,le for spending hinds in accordance with the waysthbse funds are generaieti. This turns the allocation algo-rithm into a spending plan; proCedure becomes a- surrogatefor policy. Funding algorithms-were not originally devised toserve this function. When by default theY,410 serve as aspending plan, they only cloud, not clarify,. sta ;ectives in

- higher education. An alternative is to build into` dgetprocess additional requirements for reporting and $performance. The aim of such requirements is, of course,Vot-better inform decisions concerning 'resourceHowever, they proceed on the assuMption that state

,purposes and priorities can be stated clearly enough to giveguidance to those engaged in reporting and monitoringaccountability.

Accountability loses much of its meaning when .statepriorities remain ambiguous, and desirable future conditionsunspecified. When little or no effort is.maile to understandstate purposes and intentions regarding higher education,administrators at all levels of the state system focus onmeans-bfitafaccountability rather than on ends-based stan-dards. Questions regarding accountability then typicallytake a different form: "Did-you utilize your resources asexpected?" rather than "Did you accomplish what we ex-pected?" Narrow concerns for efficiency drive out expecte-lions of effectiveness; doing things right becomes moreimportant than doing the right things. With this emphasison means rather than ends, the crucial policy questions thatlie at the heart of state-level resource allocation are answeredby indirection and inadvertence, if indeed they are answeredat ail

1

26

17

41'

s'

Current Practice

The functicuis of planning and accountability that shouldaccompany, indeed inform, the budget process are-absent from t state practices of resource- allocatiThis bridge between intentions and eons.turn, the budget process becomes but a bureaucratic thicketuninformeli by foresight or retrospective twalysis. As sug-gested iq figure 1, when planning and accountability aredenial their prIver roles, the entire process of resOurce$1kirtation is short-cireuited.' The budget then becoines .adosed but infinite imp. What are sometimes mistaken forplanning and accointebility are actually mirror images of thebudget itself. The process can sometimes become nothingmore than a self,referentiaf n $. Om that compbundspast errors and frustrates any s improvenlent;

The relationship between one's. approach ?to 'ressitirceallocation and the (ends it achieves does exist whither or notthe link is explicitly recognized:Clearly, there are twochoices. One can start with priorities and objectiVes in mindand then fashion, in turn, a resource-allocation process thatwill provlae -incentives for : achievhxg those purposes. Theuninviting alternativg is to start with or inherit a resource-allocation scheme and accept, often blindly, the 'conse-quences of the incentives and values that inevitably lurkwi tin. that system.

1T states are to mend the ways and incorporate irur-

poses and prioritieS into the budgeting process, they nuzstavoid both sins ot'aommission and.,omission. On 'the, onehand, mechsulisms for calculatinii the budget are ofteri builtin such a way that they create incentives for low priority oreven unwanted outcomes. On the other hand, the power ofthese mechanisms to influefse institutional behavior indesirable directions is 'seldom exploited to anywhere near itsfull potential:- ifirely is explicit use made of the budget andits calculafiOn mechanisms as an incentive and vehicle Loxeffective educational policy: .

0

1 f I , t f ^ a.: lat. t.rA +a ' itar--7-ii -la.- .r a,- :a rt

r a 0 11 41.-71-FT7t, t a 4- ". sok* 1 1 'at" tt

a at 6-1.4% t. t 1:t.t a5 11;- I f t.1

- t I -al Is tr.: ---7-777. t a 4) rrr a a ' I n r I :"t't

I A a it.. : a ea -7--Pra- al sa

1.s., a a .16 .

. (fit .tat ,z.. a :t II I a a a a t- * a I,

`41ta. I "r" 6 a... a a - a te as t 1 - 4 fa

Li all to 11-1, t Ea 4,11 1 ' 4-'11

t i t t.- t1 a.. 11 11 1111 : 1 5 a a :04

a a aiTICT-T'al----ti a,* tTr -7-: a' 1 a 1 I a a a,

if ^at at :4 10 Ills ta4 0,44 .4 ;".. It 1

r-taTi 44 at- a t :1 ate.-7-7 ' <61.1 at al-

1- e :Mt art 1 t- z l It a

6-111----al - a a- a a ft ' a "a tTi i lk el a S`l

a to t "ft;.571. ft./. 1,5 t a t la a MY It

t ',II a, .t $ 7-ittt.-ito at t. .,at It fa a., at- : a fa

-,11 1

a to 1 * 7-7n7717:1 I t

1

0

. ilr, . ;1.70 1111-: I 't i) I .0%

, II.,', i ^ WOI---

'4.: 4 :r

el al. Stu t. 1 4" tr. . I t

.4- 4 "WI .4 '" I: , 54 .:

:--T , 4 *. : t: v: rivi(a I r 6 F. 4 :;!. kl.

. : .--t i T-7 ft": s I . : . r -rl . : I #.,7117 t :

: al. 0) -"a -V-7,' ii.".4 I . I- f ' . J.. re

- 4"..--1

. '̂i t. * to f- T- - rt. Tirkl ,t 4---..-.--

:if- # t -1.---1-#7 '4 ' 1.44.. I it.' I'ar a t j'.. :a

:11 Tvti t., . t t,e-111-41-4,* . ,tUr.. 711-V-IT-T

1,,2 4 i -f--,

tittaN- 104

11*

;^'1,117574111r. r'1 Ti t 1 1i. It

tr,t1 tt- 1 tit st-11-1 - t , It- 54

--- "I '5 4

4

I 4 I ,15 55 55$ 1 4 I-. r=1 .-44

111 t 14 t:4;551. 5,5 t i t I re's- 5 t--4 51 t , , 7.TIT t '-olt

(-Vit II417-"--$, 5. :;=1.:415. ' I Ng

1, #1.-itta I, -t t-11-1470 fl 6 t * t t '111-0-1/ Tel it

-r -7.7" 1.7( 1 1171r:-.1 -1.1 I ,r

' 5 I 5 ^ I It ' (tit 11I T'S I _ I.- - ,;1 4 , I a 4 Ii i I ,:a : - 7^ . ' 7i4"%-`

- 4 . .- I It ,--air-4 Z 4 .1 . 1 : 0

12 a 4 I $ "t a 4 -:';'141 4 re : at p . ire t 4

- : I t 7 a.: tire .A 5 I 5 0--vi , # 11- 1 . I : 1

I

TABLE 1, continual

of the state's system of higher education appropriate?Should allinstitutions be maintaihed? Should missions bechanged?

2. Conformance to missionDo programs fit intended insti-tutional mission? ..

3. Student qualityfinstihational selectivityAre xiesirableadmissions staodards being stained?

4. Institutional qOality-.-ls the effectiveness of the institutionbeing miistaifed cir improved?

5. Program quality; Are desirable standards and curriculabeing, maintained or developed in various programs anddisciplines?

6. Resource quality. 1 fFacultyFacilities

711 LibraryISLE 4. ent

7. Insti viability (a composite). Do institutions havethe financial resources to retain a critical mass of qualitystudents, programs, faculty, and fiwilities?

D. Contributions to eatsI. EmployersThe provision .of trained/retrained man -

power, consuiting,.and Ober services.2. DisciplinesResearch contributions to specific or a broad

range of disciplines.3. State. II

Service to state agenciesEconomic developmentManpower to meet high priorisions, teachers, high-tiactand

4. Special subpopulatlons within the state.IndigentRural residentsInner city residentsAgriculture or other specific industries

B. Efficiency Aimsto accomplish all of the above with theleast draw on the state treasury.

needs (health profes-

21

22

When any state becomes preoccupied with balancing itseducational checkbook, it loses sight of three crucial points: wswp,

why it is buifing, how it is buying, and what it Is buying. Inother words, it _loses perspective on planning, budgetarymechanisms, and accounfabilitakAn awareness of the largerscore and purpose of state-leveffinancing of higher educa-tion is necessary if we are to avoid becoming prisoners of thevery budgetary mechanisms. we have eroded.

-7

1

The Chgardzational Context,

Public institutions of higher education are heavily-detOendent upon and influenced brstate government. The.few exceptions are a handful if federally funded inatitutions(and those community colleges tbakareincally financed andcontrolled. State colleges and universities are established by*statute (in some cases, omstliutionally) and are. thereforecreatures of the State. Because thefareleavily subsidized bypublic funds, they are susceptible to" direct interv(ntion byboth legislative and executhie branches of state government.Nevertheless, these institutions are unlike any of admin-istrative or operating arm of the state. They are not stateagencies in the swne sense as the Deputment of Corrections aor the Division of Hmziali Serivica. Public postiecondariinstitutions are invariably estiiblished as separately, or-ganized corporate entities with their' own governance andpolicymaking bodies, They therefore have a special relation-ship with state government and enjoy a certain degree ofindependence.

This governance arrangement is, e suffices to distin-guish higher education from most - = of state govern-ment. Other organizational of higher educationfurther differentiate colleges and universities from stateagencies. These characteiistics have a direct bearing on theform:and effectiveness of mechanisms for resource allocattion and accountability. We will be better able to appreciatethe larger context in which state-level financing operates byconsidering, the constituents and fund as of state Mahn-tions, the governance relationship between institutions and

V

31

the state, and educational production functions (the mannerin which institutions achieve educational outcomes).I

'Constituents and Funders

Postseiondary.rinstitutions are by design pluralisticbodies. They must simultaneously serve the needs and pur-poses of various constituents. At an absolute minimum,state-sqpported colleges and universities have two clearly.defined audiences: the students enrolled in the institutionand the collective needs of state citizens. Most institutions,however; hive many more constituent groups from whichthey receive some measure of support, to which they providesome kind of services, or by which they are regulated in oneway or another.

These different constituents contributerefources in airariety of forms; such as money, time, or influence. In turn;they all hold sr:kiln expectations regarding the consequencesof tiAeir involvetnent. Federal agencies, for example, provideinstitutions with funds for research, library books, scientificequipment, institutional devekipment, and many other pur-poses. In turn, they extract adherence to a wide variety ofrules and regulations, some tied to the funding, many not.They may also specify performance of certain programactivities as a quid pro quo.

Business and industry have their own agenda for highereducation. They seek as their employees college graduateswith training in selected fields, promote the provision ofinstructional programs that serve the continuing-educationneeds of these employees, and rely on universities for break-

througths that fuel technological. development. Whetheracting as individuals or as foundations, philanthropists alsoprovide funds to institutions. Although they generally havethe shortest agenda of any fonder, even they have someexpectations regarding how the institutions will behave inresponse to 'their generosity. Faculty and other employeesalso have expectations, particularly in regard to the nature ofthe organizational environment that is so important to theirjob satisfaction and productivity.

32

23

Some of these constituents-view their contributions aspayment for seivices. rendered. Students are an obviousexample, but government and industry can be similarlycharacterized, such as when they purchase research or otherservices. Other constituents view their contribations purelyas investments in the future of the institution. Donations tothe endowment fund, for example, are clearly made with aneye to the qng-term visibility and capacity of the institution. .

&ate-government is unique among these various consti-tuents, and likewise its agenda is very different from otherindividuals and groups. With`the exception of a few co)ssti-tutionally created universities, state _government has thestatutory responsibility and authority to createiioilign.ize,and divest, itself of public postsecondary institutions andtheii assets.' Andle boards of trustees -or regents are estab-lished to carryout the governance said policy functions ofcolleges an uniyersities, .state government hotels ultimateauthority. This authority can be wielded 'directly throughstatutes or hidireotly, through the budget.

As a function of this responsibility, state governmentmust necessarily view the institutkon, or its system of instills:-Lions, in investment terms. Cleariutate government wishesto maintain or create a desirabk mix and location' of post-secondary institutions and prdpams. It also desires qualityfaculty, appropriate facilities up-tcrdate laboratory ,equip-ment, and libnny and other information resources that are atleast adequate to the needs of each institution. Of course,states do expect more than "good"' institutions to result fromtheir appropriations. They also expect trained manpower,solutions to problems facing the state, and certain goods andservices that may also be priorities of other constituentgroups. These expectations, however, do not lessen_what isthe state's primary obligation: concern for the condition of itseducational assets, whether in the form of programs, faculty,or buildings.

Two salient points emerge from this brief discussionabout the pluralistic nature of higher education. Both areobvious but are so important as to warrant repetition andfurther emphasis. First, while state government is the majorconstituent of public higher education, it is by no means the

"IN4

only con ht. College admtnistrators are faced thenecessity of simultaneously responding to # groups,each of which has provides financial or other resources tothe institution and each of which has a somewhat different _

set of .expectations. When compared to state government,these other groups may have a small butevertheless impor-tant stake in the enterprise: As a result, hatever kdgetingprocesses areiput in place by the state must serve the state'sneeds but not diminish the institution's ability to respondappropriately to other constituents. Second, of these variousconstituents, state government is the fonder that must con-cern itself with the ongoing viability of its higher-educationsystem. No other group has a material interest in the investment component of support to public colleges and =Aver-sides. Others are better viewed as purchasers of services. -N

Indeed, what sets state colleges and universities opted fromtheir private counterparts is this public responsibility for thedevelopment and maintenance of institutional assets.

Governance

Thektudget is often the most tangible and direct linkbetween state government and its educational institutions.However, the structure and purpose of that budget are oftenshaped by the governance relationships that ,-st betweenthe state and these institutions. Although perhaps pot imme-diately apparent on a day-to-flay basis; these governancearrangements have a pervasive influence on ho* the budgetis conceived and implemented. These relationships can becomplex and, mor4ver, can differ greatly from state to state.

nIt is not the purpose of this book to describe these com-plexities in detail or to enumerate all existing varieties.Instead, it is far more helpful to consider the continuum ofpossible relationships. As suggested by Denis Curry, NormanM. 'Fischer, and Ibm Ions (1982), these relationships span abroad spectrum (see figure 2). At one end of the spectrum,educational institutions are treated much like state agencies.At the other end f the spectrum; institutions function muchlike independent, nonprofit organizations with which thestate contracts for desired services. in practice, of course,

; 4

;A

26

f

FIGURE 2

Governance Relationships

Greater Institutional Autonomy

Greater State Control

pinnain Denis J. earty, Noon: M. Pischen and *n loos, "State Policy Optionsfor Pinancing Higher &Wad= end Accountsbilily Objectives," Ham*Issue PR" no, 2 IN State Council for PostsecondaryEducation, Gmarnittee of the Whole, 1 February f9824.1

4

neither of these extremes is found in-its Pure state. Neverthe-less, they represent,the tArn poles of a continuum alongwhich we can locate actual governance felationshipS. As wemove along this continuum from the state-agency modeltoward the free-market model, wefind that the state's role isincreasingly circuinscribed and that institutional autonomyexpands correspondingly. As an expansion Of figure 2, table Zcharacterizes these 22fferent arrangements with respect tofinancing, budgeting, and accountability.

Drawing upon table 2, we can arrive at some concluaionsabout the close-relationship between governance arrange -ments and the structure and function of the budge,!. As withall generalliations, there will be some exceptions.

Means versus En& Under the stateogencythe state places emphasis on the ways in which institutionsfunction. Important variables include such factors as classsize and the number of contact hours faculty members arerequired to teach. At the other end of the continuum, the

4,

4

free-market model expresses state interests in terms ofpurposes or ends. The question here concerns what servicesor oppoittmitie.s the state is buying from the institution. Inother words, the state-agency*model emphasizes operationalpurposes; the state's priority is to have educational institu-tions function in a particular way. By contrast, the free-market model emphasizes strategic 'purl:ones; the state'spriority is to have educational institutions achieve certainends that serve broader state purtmses. Clearly, differentgovenumce arrangements both, presuppose and reinforcedifferent state objectives for higher education, be they opera-tional or strategic. In short, governance relationships reflectstate priorities.,

-Accinintability. Bemuse, state purposes for higher educa-tion are expressed in different ways under different forms,of governance, accOuntability arrangements will also vary.Un4er the state-agency made!, issues of aroimtability focusa l m o s t e n t i r e l y on.. titit procedure, and emphasizeprimarily fi*cial isideratirms. Were expenditures madein accordance with the details cones in the spendingplan? Were stipulated Procedures foljpAted for handling avariety of transactions in su4Faireas as personnel andpurchasing? Because this form oraccountability is largelyfinancial in nature, the for ensuring accountabilitytend to be directly into the budget process.Figures about actual expenditures during previous yearsbear directly on discussions about future budgets. Issues ofaccountability under the "free-market model focus leis, onfinancial matters and more on outcomes and effectiveness.As a consequence, considerably different data and reportingmechanisms are required to monitor and demonstrateaccountability. These arrangements- Can- be air adjimato thebudget process can lie 'almost entirely outside of it.

Constituents. OVa state-agency model, the statelooms as the overwh t dominant , tuent When"all funds, regardless of their' source, are a . into thestate general fund and allocated through, I, ve acts, theperspectives. of other constituents are masked. Such circum-stances militate against simultaneously achieving an array of

37

. -

4 , . r

products and benefits that serve other groups. These qp-stihients simply lack the, leverage they need to make theirvoices heard. Under the free-market model, the state is justone of several "customers" that the institution serves. Thiskind of governance creates great incentives for institutionaladministrators to maximize those benefits that serve avariety of customers. It also creates circumstances underwhich constituents-other than the state have considerableincentive to enter into mutually _beneficial arrangementswith the institution.

When state guidelines become 'highly prescriptive, insti-tutional managers are left with very little maneuveringroom. This makes it more difficult to design activities thatserve multiple purposes simultaneously. In turn, other con-stituents may by less willing to invest their funds in lb&institution under these conditions. When governancearrangements approach the state-agency model, institutions

:lbecome less able to tap potential support fro .ether coast'-tuents. Their revenues are deiived almst- exclusively frontstate appropriations.

Consumers and Investors. Under the free-market model,the state becomes a consumer of educational products andservices. It invests in the educational system only insofar asit utilizes institutions in ways similar to othet constituents.Under this niodeMpreserving institutional viability becomesthe responsibility of the individual college or university Inall other models, thetoatescetains responsibility fqt creatingand maintaining the system of higher education. I

Methods of Resource Allocation. Governancements do not necessarily determine the method ofallocation. Various mechanisms for calcuting the amountof support can be employed in all of these models, However,there are some obvious affinities. Linder the state-agencymodel,, educational institutions are treated like all otherbranches of government. Under, such an arranpment, wecan easily expect incremental budgeting on a line-item basis.Under the free-market model, the level of service as wellasits price wills.be subject to negotiation. Between these two

_extremes lies the full panoply of arrangements that exist inthe SO states.

38

29

30 I

The relationship between governance and methods ofresource allacation has further ramifications. As is illustratedin figure 3, the level o* detail incbrporated into budgetcalculations can vary. The amount of financial data employed inthe budget process decreases as one moves toward the free- 4market arrangement Conversely, the agaount of data aboutperformance, effectiveness, and outcomes increases. Underthe state-agency 'model, the state ooncerna itself with alldetails of institutional functions and programs. Under thefree-market model, the state is concerned wititlinancial data

. only to the extent that it is used in justifying or negotiating4 the price of opportunities or services it chooses to purFhase.

The above five points emphasize that the budgeting pro-cess is shaped not only by a state's educational objectivesbut also by its policies regarding governance and level ofcontrol. Indeed, these two notions work in close tandern4oreinforce a particular approach. t state control, goeshand4n-handVith . ural and . nal purposes andleads almost inevita to line-item b and a finance-oriented accountability system. Less rigid state controlprovides, the opportunity to include more ends-orientedpurposes. This in turn promotes budgeting :schemes andaccountability Mechanisms that focus on services renderedand objectives achieved.

As should'be apparent, structural and philosophic (oresprovide the environment within which budgeting systemsmust be devised and assessed. These forces vary greatly fromstate to state. This should give considerable pause to anyonetempted to borrow new budgeting approaches from otherstates without investing considerable effort to understandthe contexts within ich it is operating. "Environmentalfit" is a topic far fob little discussed in the extensiveliteratureon formula funding and other budgeting devices. By concen-trating on basic concepts and emphasizing the broad contextwithin which the budgeting process occurs, this book isdesignsil to help fill this gap in both theory and practice.

39

' .

47,

FIGURE 3

Areas of Emphasis in the Budget Process

J

State-AgencyModel

e.

Production Relationships

Free-MarketModel

Most educational outcomes can be p cad in a varietyof ways. in other words, educatiortal ction *relation-ships are very loosely defined. For (wimple, instruction canoccur through large lectures or through small seminars; faceto face or through such media as television. Similarly,research activities can be conducted by employing seniorresearchers, fulPtime technicians, graduate students, andundergraduate stu s, in widely varying proportions.Again, num St factors influence just how a project isaccomplished. e areS no absolutes on how best to goabout the business of education. Deciding whidi productionrelationship to employ is a function of institutionalpreferences, the skills of individual faculty, and theavailability .of faculty, facilities, egisipment, and other

31

1......:14 4..4, I . I I . ...1_16: 4 4 4 i : 4 1114L' I II : 11 41 I

11 : 4 Ls 1 ' ...... ..I . > 6 ;.....A1 A ,-.4. 4 LI 8 ' 4_

4..44 4 .:

OIL...1.2 44 ,..' 4 4 lt....11 1,162 Mt 4 I : 4 4 .." 4 14.. 41

:Si : : ...Li I 4 1 : 1 :. I; .: 4,4 1 I t 4 :I 1

4 4 1 1 1 1 1 i I 4 . 4 4 ..o. 4 4 4 6 ... .1 4 I

_I_.".2

I . 4 : 4 4. 4

. ),4_114 6.4 4r a1' 11 Y.) 4 ...'4 4 6-11 I

.1 '6 4 :... 4 LAIL4104 4...4 4 6 : I it_ii : ..0).3 : . I I

4 , 1 4 .. 4 . 4 .L4 1 . :,.,4 / ... 11' 1 .4 3 [11 if al I

,:. .1 4 1. ' 4: 4 4 I . I 4 1",..I ' . 6 6 11: 4 64-.

II i..L.:i. i 91 1_/' t.14 9.1--.. * .-k:_..i..-.

t ; 4 , I ...44 1,11 I

. ,4 . 141 446 1 : . 4 * 1 L,.... 1 4 1:4 I I illi ;I 11...0 1 , 4 . I

I 1 4 ..... 4 1 k4 1 4 11 '

6 1 41511,.14.1

4 1 ID

1 64;,14... 4 1 64 .. 114.

11 4 I ' V t:i_1...41.22,.'

0,4 11 i, . .41_ 4 1 It - 1 ,4 .4

L141, I 6 a. .. 41 ;16LL.. I ±.4_1:43 ILL

4 /8 I.._ 4 1,04. 1 4 1 I It 4 : $ 0'0 4 4 1 .,

.11 t% I I. 4 III I .. ,114 .1: 1 41.L.: 1 .1 .4. 1 1 1 IQ 4,6c 44 1.

I 414 44 ''Ali 117.1., I II

11.4 16 Ji 1 ' -.4.41 421.1,6j4,614141 1111,, ;

1 14.1,1 ttt ; t 4 64 , 141 , 1,1114 4. 4 .41

: _414 4/ 12 6 110:AI 10 4'4 : 6' _161:o,

' 44* 11 LL'.41',.4,4.,:4

iI 46 I 1 4 4 .41116 Oa

14 5 :0; t 444.L.S,L61_: 1_1 _..1_411 4. 1 1 .4 4 "...,414 1 1

1 . 1 : $ 1 1 4 1 f I 4 4 41 4

41 . I # ei I :_1 ...N./ j 1_42

6 I 4410. I 1 ILL108,, ,*111 4 4)11 1 It .4 1 .4

: LO t t: I k I 1 . t; _Ott VI it

t 4 5 'It. 145: 14 I, 40.494J .

If 4 $ ...* .1;. 4 :

, 1 ; ' :1 4 =4 : 41 I 4 4i

e, 4 4 6 :

* 10 1' 4 .zU.... 4 .4 r. 421111 r t V 4_.21 :1

: 1 * * * I S : 1 , 4 4 4 4 4 .`il ..* - 1 1 1 . 1 - 6 . 4 14 604 ;...1 4,14 .614

.... . 1 . 41 C. 1214 4 41. It I 4 4140,411,114 4.44 '....11; :;4444 4

614 47_' 4_21....-.-- 1,:- 4 41 t -49 -41.- 4 4 : 4

.. 4 I , 1 4 . '4 1114,;.4$ : s I I 4 . 4 1141.4 : 6 4: 44`: kw.

4 s

I

Atigyzing these multiple outcomes is difficult becausesome are directly intendecand accomplished by postsecon-dary institutions, while others are merely ancillarytteffects,The line that distinguishes what is actually produced oncollege and university campuses and what is not remainsunclear. Moreover, some production relationships occur ontechnical grounds, while others.arephiefly organizational in-nature. Sheep raising is a good example of joint productionthat proceeds from technical considerations. To otitputs,wool and mutton, can be produced in varying proportions bya single production process. Itacli output is a natural, indeednecessary, consequence of the other.

joint production in higher education occurs on differentgrounds. Colleles and universities produce outcomes jointlynot. out of t necessity but for reasons of mania-

-tional efficiency = * effectiveness. Clearly, it is not valid toseparitte one activity such as teaching or research) and,analyze produttion and cost relationships associated With it

. in isolation from fl) Other institudinial activities., Colleges-and universities organize thernselves to produce multiple,not single, outcomes (through one set of tx7ordhuated activi-ties because joint production con be more cast-effective. Inother words, they wish to maximize the possibility of jointsupply, it condition in which multiple outputs can be pro-duced more cheaply together than separately.

The possibilities of joint supply on,collegm and university'campuses justifies their being assigned the. Various functionsthat are now commonly accepted as being within their pur-view. For example, much of the nation's basic research isconducted in research universities rather than in separatelyOrganized research centers: The rationale for this should beclear. Research activity produces knowledge 'while also`ediicating a new generation of research scholars;Conversely,.graduate education issuch that it also yields new discoveries.

. The assumption is that combining both functions is, or atleast can be, cost-effective.

Although colleges and universities,genenally undertakeac $lvities that yield multiple outcomes, their activities arenotsolely of Chia nature. if the expectations of certain constituent'groups are to be met, institutions may.-have to institutespecial programs. The benefits'of these activities may not

*

01 tki.4 I 1_ IL, Imtal.il I .44 4, :at 1.1- IL: I I I $ 4 V'

....1 .41 ....: 44 il 41 i , .4 4... 41 1_, 44

1: I . 40_2 a .41 .) 1 ,* j i a 4 4 4 4;

4 111_( i 1 4 1 :0 1.2.,_t_ II V -a i jol _.2 _f_s I :.* - u..t ;;.4

. 1 4) . la tell_ . .4 f : 1 ..4..i :4t ...4 II 1 .4 Al s 4.:

1 4 I 4 ...at; 4. 4 13" I 4 .4 _1 1. .1

ast, 4 4 4 .4 .,...1_1_ 4111. i -.01_ 4 I1 I '-' a

Ii-'...; 3 1. I I. I .444 ..n._ I. 4 *st s wli *4 ' 4r_i.l. -..- 1)

II If I,. I -, I I' 44 41 4 1 1114t41411 4 Vi 11 1 It ...4 ;

4 11; 4,4 I 44 I . 4. 14 1 .0 a 111 4 a0A1j1_141 a , 4 4 a

a "..1t_tt 4 t I , 4 : ....ti k4"..41 4, . 1 4 44 4 11

4.4... 14 1 I 1'.'1_1. 444 14,444 4-41m

S. ..44 ..114 11 :I 4 .11

4,1a. L.2.11 I 11 -14 1 It Il 4 1 el *4 i

11, , - 1. * . , lit ik 44..1. t .1 it / I -4.4 ,_441 .

a .- t 4,4.1171. 1 = .... 4.4,4 1 . t I [4,)1 it 1 ..4 (

4 . $ t,..11 41 41* 4 1 4.1 Is -4, ...ii Ii ..... 4 4...... viii

44 1 .3 II 4 t to , .... I 4L- i 7 .4 4) ' t.4 4 .141

. 4 4 VI 40(0.4111_414 I I i.1 4 CI . 1 11, 14 I j.41) *I a 4.. I.

:..... 4 pi., 1 . L. 41. eLLI.A0,,_.411_ , a 41[..:0t. . 4 4 44 14' 4 .

, 4, 4 ,. .1 r....; '4 4...4:Z, 42 41 11 ,..$ L. _42.....41. ii....-±c

4 : I t a 4 k 41L2__ IlLito 2.. 4 _..,, 4 1441 4..4 ,..i , =. 1 4......

41 ; I ;. 11.. : 14 4_,_142,_= 4 1 -It 4.1 1 .14 41 4. . 1 1

.4 1 4 f:.4 I a _all' i 1.41 1 4 .4 4,4 . 4 i i$ . 1) -0 4 41 4 ..

'II it____114 14 1-1 11 .14,....1.11=. 4 1,, 4 40440 1$ VI 1444 411_4 11

' 1,4 i 4 , , 1±.4±:isuji : ,...:414 fit .2.14. t_4: . .44 11 4 .4.411 it, 1.. I

5 4 I '04...al .3 a : 4.-f V =. 4 .1I ...,' 1 : 4 ill

41 = I ; 1 ,141: V 0 :44 : . L. kir,1 4 4. 4 4 1 1 , 611, t-

I .af, 4 ta ; s ...44 ;ii 4 ; ' a a .-.1 .44t1 . I_' 4 1l 111

..; a 1.4 ....1 , $ .4 la 4 4,4_2 1 4

4 .4.1 '14 it . 8 4 ... 4 , r; . ; 4..) 44 i 14 *j$ , 4 4 -al NA ..;,`_4la.

I : II i 4 $1 0 .....4 U4,7,4 a a 0 4 4 1 '

L.., : 4 4'1 ,11_11. -1111

. II 1 .4....1.,....1 111 : 4 I ...11 4 I 4 4 I 'I: II 4 4 4

;11 i .61_--:: 4 .44 A .4 4 1,...,414: 4 1/4 . * 4' a 11111..14 _I .44 4; l.4 1,1114Ar,'

'-a, tt..;mi 4' ) . . / 0 - I. 4 , 4 '1$ I ...: 4 j it , 414 4, ' .. 44 s; 4. I/. 1.

tall 4 =4 t .41 4 . 1 :I w ...- -wiw - 44 ,I i I 1 . . .4 ' 4.,.. ..1

4 a11 II II , ;1114141_,.. 4 . .1 4 $1 . t 14 4, 1 4. 4 . ...1 1 Mt

it 44 *may 4' 4 14 4 't_wk24., 5: $44. I L11_

'14,4 41114 ' a 1.4 Lt.1014 11 111 4 4 '

natural selection process, such institutions attract consti-tuents that have compatible expectations. Institutions thathave particularly fwzy-missions or project an unaear insti-tutional image to various constituent groups are most likelyto be faced with irreconcilable deniands from their variousconstituents. this is not to say that independent activitiesand programs cannot be established to respond to theseneeds. Indeed, such a capacity is one of the virtues of thelarge public university; it can put forward different faces todifferent audiences and do so successfully. What is lost,however, is the opportunity to gain some efficiency in theaysteut If state-level rewurce allocation is to take advantageof the benefits offered by joint-production relationships,administrators m be willing to devise schemes that areresponsive to and nforce different institutional Mi8SiOnS.

ti

The Structure of the Budget

'Having discussed the function and scope of the budgeta. and some of the contextual factors that must be considered

when developing an approach to resource allocation, we cannow consider in genetic terms what structural componentsmake up a budget. Higher-education budgets are formulatedin nearly as many ways as there are states. Nevertheless,these many approaches can be viewed as combinations ofonly two basic forms: a multipurpose (core, general) compo-nent, and varied 'numbers of single-purpose (categorical,*dal) components.

The Multipurpose Component

Invariably the larger of the two components, m<purpose funding provides support for basic operations anprograms. State allocations to the multipurpose componentare accompanied 1* expectations that the/will meet nearlyall educational objectives. The majority of these purposes areclosely interrelated; yet seldom are they made explicit in anyorderly or comprehensive way. In many respects, it is dif-ficult to achieve consensus about these purposes in anything

44

but glittering generalities. Nevertheless, it is still possible toidentify several key state ptuposis that are closely tied to the .core component of the budget:

1. Access to higher-education opportunities. While accessfor stale citizebs is not an end in itself, irumy benefits doaccrue from a morehighly educated citizenry. This con-.Ames to make access* educgtlimudopportunity alutsicstate purpose and an. (miming priority. .

2. Economic 'development. States are ecrinfomic as *ell pispolitical subdivisions. As such, a' healthy econotfty isnecessarily e statittiority. Higher education can meetthat objective through training- and retraining of askilled work force, through research and innovationthat assist key state industries, and.through its role as amajor esmloyer and industry4n its own right.

3 Maintenance and enhanCement of the edueation.alsystem. Unlike other constituents of *public highereducate, the state has responsibility for developingand maintaining educational assets. ItSpust decide thenumber and location of public 'postsectdary iastitu-.fions; the mission, role, inui scopecithese institutions; .'end the level of quality to be

4. Efficiency. Although efficiency is seldom lisked as amajor, state priority, actual practice is such that it canhardly be omitted from the list. Indeed, it may be usefulto incorporate efficiency into a more outcome-oriantedlist of state priorities so that inevitable calls for effi-ciency will be cast in terms of trade-offs .that mayimpinge on effectiveness.

because there are joint-supply considerations involved,the costs of achieving the above objectives cannot be par-celed out and treated separately. This is why states seek toencourage joint supply through a se major allocation.The msiltipurpose component of the budget is designed tosupport activities thatwill allow institufions to achieve thesemultiple yet ,closely interrelated purposes.

45

4

The Single-Purpose Component

AlthoUgh core funding for higher-education institutionsmay derive from the multipurpose component, no state canignore the seed to allocate special-purpose funds. Three 0.basic reasons' prompt states to approve single- 9 VI 9 alloca-tions above and beyond the multipurpose co nest of thebudget.

First, the single-purpose component accommodates thefact that states may halm specific objectives or priorities forhigher education that are best met by allocating a special mitof money,- In many-cases- these priorities ihay representshort-term rather than ongoing needs. In these circum-stances, it suits both the state and the institution' to create a"special project" to respond to the need, fund the projectwith special fads, and not incorporate these funds bito thebale allocation given to the institution. Under this arrange-meat, the state becomes, in essence, a consumer of services,

. with the financing airangement serving as a turchape agree-ment-Neither party to the transaction ,expects, or shouldexpect, the arrangement to be long-lived.

Second, the state may approve si*cial-purpose alloca-tions to create additional incentives for activities that ateongoing within the institutions but that have emerged ashigh priorities. Consider, for example, the recent need forteachers in bilingual education. Because of federal initia-