Getting Closer at the Company Party: Integration Experiences,...

Transcript of Getting Closer at the Company Party: Integration Experiences,...

OrganizationScienceArticles in Advance, pp. 1–25ISSN 1047-7039 (print) � ISSN 1526-5455 (online) http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1120.0808

© 2013 INFORMS

Getting Closer at the Company Party:Integration Experiences, Racial Dissimilarity,

and Workplace Relationships

Tracy L. DumasFisher College of Business, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 43210, [email protected]

Katherine W. PhillipsColumbia Business School, Columbia University, New York, New York 10027, [email protected]

Nancy P. RothbardWharton School, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104, [email protected]

Using survey data from two distinct samples, we found that reported integration behaviors (e.g., attending companyparties, discussing nonwork matters with colleagues) were associated with closer relationships among coworkers but

that this effect was qualified by an interaction effect. Racial dissimilarity moderated the relationship between integration andcloseness such that integration was positively associated with relationship closeness for those who were demographicallysimilar to their coworkers, but not for those who were demographically dissimilar from their coworkers. Additionally, thismoderation effect was mediated by the extent to which respondents experienced comfort and enjoyment when integrating.These findings highlight the importance of creating the right kind of interactions for building closer relationships betweenemployees, particularly relationships that span racial boundaries.

Key words : diversity; boundary theory; racial dissimilarity; high-quality relationships; integration; segmentationHistory : Published online in Articles in Advance.

IntroductionRelationships between coworkers are increasingly im-portant in today’s organizations, particularly given thecollaborative nature of service and knowledge-basedwork. In fact, coworker relationships influence impor-tant organizational outcomes such as work group per-formance (Gruenfeld et al. 1996, Harrison et al. 2002,Jehn and Shah 1997), organizational citizenship behav-iors (Kidwell et al. 1997, Podsakoff et al. 2000), atten-dance (Sanders and Nauta 2004), and turnover (Iversonand Roy 1994). The growing importance of coworkerrelationships is complicated by the increasing demo-graphic diversity in today’s workforce. The effects ofdiversity can vary, but demographic diversity, particu-larly racial diversity, is often associated with relationalchallenges including greater conflict, lower cohesion,and lower-quality communication (e.g., Hoffman 1985,Pelled et al. 1999, Tsui and O’Reilly 1989; for reviews,see Van Knippenberg and Schippers 2007, Williams andO’Reilly 1998). Recommendations both for improvingworkplace relationships and for managing diversity oftenentail encouraging employees to attend social eventswith coworkers, bring their family members to organi-zational events, or disclose information about their per-sonal lives at work (Casey 1995, Ensari and Miller 2006,Finkelstein et al. 2000, Fleming and Spicer 2004, Pratt

and Rosa 2003, Roberson 2006). These behaviors areaddressed from a number of research perspectives, allwith the expectation that they will improve relation-ships. Boundary theorists have described behaviors suchas attending social events with coworkers as integra-tion practices because they allow activities, emotions,artifacts, and people commonly reserved for the non-work domain to transcend the work–home boundary andenter into the workplace (e.g., Ashforth et al. 2000).Also, diversity researchers have included behaviors suchas socializing with coworkers within their concept of“social integration” (e.g., O’Reilly et al. 1989). How-ever, it is not clear whether integration behaviors actuallylead to improved workplace relationships, particularlyfor those employees who are racially dissimilar fromtheir colleagues.

We posit that integration behaviors have implicationsfor workplace relationships that are underexplored inexisting organizational research. In doing so, we drawfrom the emerging body of research on boundary the-ory, which has provided a great deal of insight into theways that individual and organizational practices shapethe temporal and spatial boundaries between employees’work and nonwork lives and identities (Kreiner 2006;Kreiner et al. 2006, 2009; Nippert-Eng 1996) as well asindividuals’ preferences for integration (Kreiner 2006,

1

Copyright:

INFORMS

holdsco

pyrig

htto

this

Articlesin

Adv

ance

version,

which

ismad

eav

ailableto

subs

cribers.

The

filemay

notbe

posted

onan

yothe

rweb

site,includ

ing

the

author’s

site.Pleas

ese

ndan

yqu

estio

nsrega

rding

this

policyto

perm

ission

s@inform

s.org.

Published online ahead of print February 28, 2013

Dumas, Phillips, and Rothbard: Getting Closer at the Company Party2 Organization Science, Articles in Advance, pp. 1–25, © 2013 INFORMS

Powell and Greenhaus 2010, Rothbard et al. 2005).Qualitative studies within this body of literature suggestthat managers expect integration behaviors to have pos-itive effects on relationships in the workplace (Nippert-Eng 1996, Pratt and Rosa 2003), but these studies didnot theorize about or test these effects. Here, we chal-lenge and test the expectation that integration behaviorswill always improve coworker relationships and arguethat racial dissimilarity may moderate this relationship.

Indeed, although organizational researchers are devot-ing increased attention to the ways that employeesmanage the boundary between their personal and pro-fessional lives through integration practices, the questionremains as to how demographic differences in the work-place, particularly racial dissimilarity, might affect thedynamics of integrating one’s work and nonwork lives.Boundary theorists suggest that people may benefit lessfrom integration behaviors when values, expectations,and norms of behavior in their work and nonworkdomains differ (Ashforth et al. 2000, Clark 2000).We posit that the demographic differences betweenemployees and their colleagues may also affect out-comes associated with integration behaviors. Thereforewe contribute by connecting research on boundary the-ory with research on demographic diversity.

We also contribute to research examining demo-graphic differences in organizational contexts. Diver-sity research reflects the expectation that under specifiedcircumstances, increased contact, information exchange,and personal interaction are solutions for interracial rela-tional challenges (Allport 1954, Ensari and Miller 2006,Miller 2002, Pettigrew 1998, Tropp and Pettigrew 2005).Moreover, existing studies of diversity in organizationsreflect the assumption that behaviors such as socializingwith fellow workers (an integration behavior) and attrac-tion among coworkers will necessarily covary positively(Harrison et al. 2002, O’Reilly et al. 1989). We directlyaddress and test this assumption in our paper. In orga-nizational contexts, people may voluntarily participatein social activities with their coworkers or even discussnon-work-related matters, and yet these behaviors canfail to reflect or yield closer relationships among col-leagues, particularly when they are demographically dis-similar from each other. We propose that the potentialpositive effects of increased social interaction with anddisclosure to coworkers (i.e., integration behaviors) willbe attenuated by racial dissimilarity. We also examinethe process by which this attenuation occurs. Specifi-cally, we consider how the quality of the individual’sexperiences while integrating affects his or her relation-ships with coworkers, thus highlighting the fact that inte-gration behaviors alone are not enough to produce closerrelationships. Rather, employees’ experiences when inte-grating are critical.

Addressing the effects of integration behaviors withindemographically diverse settings has important implica-tions for organizational efforts to improve employees’

working relationships. Also, understanding these dynam-ics will be helpful for interpreting the social interactionthat is often observed in organizational settings. Ulti-mately, we aim to improve our collective understandingof how to build better relationships among employees,particularly those who are demographically dissimilarfrom their colleagues.

Integration Behaviors andClose Employee RelationshipsIn considering workplace relationships, we focus on theextent to which employees view relationships with theircoworkers as “close.” We define closeness in coworkerrelationships as the extent to which people feel a senseof connection and bonding with their colleagues, or theextent to which their relationships go beyond the mereperfunctory tasks associated with their work (Bacharachet al. 2005). Given the importance of coworker relation-ships in organizations, a number of organizational schol-ars have studied similar concepts. For example, Ibarra(1995) examined what she called the “intimacy” ofmanagers’ organizational relationships by asking mem-bers how close they felt to each of the people listedin their organizational networks. Podolny and Baron(1997, p. 683) examined closeness among organizationalmembers, which they defined as the degree to whichrespondents had “direct personal relations” or were“friends” with other organizational members. Likewise,Carmeli et al. (2009) studied the concept of bondingsocial capital, conceptualized earlier by Adler and Kwon(2002) and Onyx and Bullen (2000) as a measure of“high-quality relations” and “bonding” among employ-ees, which included consideration of how “close” peoplefelt to coworkers, as well as support, caring, and trust.Research addressing relationships between coworkers ortask group members often reveals the expectation thatclose relationships would be reflected in behaviors suchas socializing together (Harrison et al. 2002, O’Reillyet al. 1989) or sharing personal information (Bacharachet al. 2005, Fleming and Spicer 2004, Hurlbert 1991).Given this expectation, we felt it was important toexamine the association between closeness and thesetypes of behaviors—which we describe as integrationbehaviors—directly.

Integration behaviors are individual practices that blurthe boundary between personal and professional lifespheres (Ashforth et al. 2000, Clark 2000, Kreineret al. 2009, Nippert-Eng 1996). Boundary theoristsexplain that “integration” entails creating a permeableboundary between multiple life roles and domains bycausing overlap between them, and it also entails locat-ing behaviors, emotions, people, and artifacts from dif-ferent roles in the same time and space (Ashforthet al. 2000, Nippert-Eng 1996, Rothbard et al. 2005).In an ethnographic study, Nippert-Eng (1996) identifieda number of behaviors and practices as “integrating,”

Copyright:

INFORMS

holdsco

pyrig

htto

this

Articlesin

Adv

ance

version,

which

ismad

eav

ailableto

subs

cribers.

The

filemay

notbe

posted

onan

yothe

rweb

site,includ

ing

the

author’s

site.Pleas

ese

ndan

yqu

estio

nsrega

rding

this

policyto

perm

ission

s@inform

s.org.

Dumas, Phillips, and Rothbard: Getting Closer at the Company PartyOrganization Science, Articles in Advance, pp. 1–25, © 2013 INFORMS 3

including participation in social activities with cowork-ers, bringing family members to work-related activities,displaying pictures of family and friends at work, ordiscussing nonwork matters with coworkers. For exam-ple, in describing one integrating employee, Nippert-Eng(1996, p. 9) wrote, “He brings the family to an annualworkplace picnic 0 0 0 0” As conceptualized by boundarytheorists, integration can be unidirectional or bidirec-tional; that is, employees may integrate from nonworkto work by allowing aspects of their personal lives toenter the workplace, from work to nonwork by allowingaspects of their work lives to enter their personal lives,or in both directions (Ashforth et al. 2000, Kossek andLautsch 2012, Nippert-Eng 1996). Additionally, integra-tion includes both interpersonal behaviors (e.g., social-izing with coworkers or discussing personal matters inthe workplace) and task-related behaviors (e.g., handlingpersonal business at work, completing family-relatedtasks on the job, or taking work home) (Kreiner 2006,Nippert-Eng 1996, Olson-Buchanan and Boswell 2006).Because we are addressing implications for interpersonalrelationships within the organization, we focus on inte-gration behaviors that entail incorporating more of theemployee’s personal life into the organization and thataddress the interpersonal aspects of integration.

When employees blur the line between their per-sonal and professional lives through the kinds of integra-tion behaviors described above, they may develop closerrelationships with their coworkers. Although existingresearch documenting integration behaviors among em-ployees has not explicitly focused on improved coworkerrelationships as an outcome, these studies generally sup-port the idea that efforts to incorporate employees’ non-work lives into the organization can help foster closerrelationships among employees (Kirchmeyer 1995,Nippert-Eng 1996, O’Reilly et al. 1989, Pratt and Rosa2003). Indeed, the O’Reilly et al. (1989) study of diver-sity and turnover in work groups assumed that thisrelationship was so strongly positive that they com-bined attraction to, satisfaction with, and socializing withcoworkers into a single “social integration” index vari-able. Pratt and Rosa’s (2003) qualitative work suggeststhat when employees feel that the organization invitesthem to incorporate their non-work-related identities androles into the organization, they feel a stronger connec-tion to the organization and its members, because of theirbelief that all aspects of their identities are welcome inthe organization, and a reduction in the feeling that theirprofessional lives necessarily conflict with their personallives. The idea that integration behaviors can enhance asense of closeness to coworkers is also expressed wellby Nippert-Eng (1996); she described a new employee’sadjustments to working in a department where integra-tion behaviors were common and encouraged:

Now, along with several colleagues, she [Lauren] partic-ipates in the Lab’s ballroom dance club, her departmen-tal volleyball team, post-workday medical seminars on

healthier lifestyles, tennis, and lunchtime “power walks, ”exploring the local grounds while talking about so manydifferent “home and work things.” (pp. 181–182)

Lauren was also surprised to see how people in her newwork group talk about family and leisure concerns when-ever they like. Brief phone calls to cross-realm othersare assumed 0 0 0 0 Lauren now feels free to make andreceive such calls. Between this and the expectation thatshe’ll talk with coworkers about her outside interests, Lau-ren’s previous feeling of estrangement in the workplace isabating. (p. 182, emphasis added)

Integrating by participating in social events withcoworkers can also provide the opportunity for employ-ees to acquire additional information about each other,which is important for the formation of close relation-ships (Asch 1946). Joint participation in leisure activitieshelps to motivate the sustained interaction necessaryto advance relationships because “playing together”creates a context for information exchange (Altmanand Taylor 1973, Hays 1984, Segal 1979, Werner andParmelee 1979). As explained and illustrated in thequotes above, integration behaviors also entail refer-encing nonwork roles or sharing personal information,which can increase the sense of connection and bondingwith others in the workplace. Studies of self-disclosuredemonstrate that sharing personal information makespeople feel closer to each other and increases the extentto which people like each other (Cozby 1972, 1973; for ameta-analysis and review, see Collins and Miller 1994).This explains why sharing personal non-work-relatedinformation in the workplace may improve relationshipsbetween coworkers. It is important to note, however, thateven if coworker interaction does not include direct ver-bal self-disclosure, joint participation in social activitiescan provide them with information about each other. AsStephens et al. (2011) explained, in the context of theworkplace, social activities take employees out of theirregular routines and interaction patterns, allowing themto see each other differently. This, in turn, can allowthem to form closer relationships. Similarly, Ingram andMorris (2007) explained that parties and social mixersprovide the opportunity for encounters that can cementfriendships or serve as important first steps in formingclose relationships in professional settings.

In sum, researchers studying the interface betweenemployees’ work and nonwork lives suggest that inte-grating employees’ personal and professional lives willstrengthen their bonds to the organization and fellowcoworkers (Nippert-Eng 1996, Pratt and Rosa 2003).Moreover, classic psychological research on relation-ship formation supports the notion that participatingin social events and sharing personal information willbe associated with closer relationships among cowork-ers (Altman and Taylor 1973, Hays 1984, Werner and

Copyright:

INFORMS

holdsco

pyrig

htto

this

Articlesin

Adv

ance

version,

which

ismad

eav

ailableto

subs

cribers.

The

filemay

notbe

posted

onan

yothe

rweb

site,includ

ing

the

author’s

site.Pleas

ese

ndan

yqu

estio

nsrega

rding

this

policyto

perm

ission

s@inform

s.org.

Dumas, Phillips, and Rothbard: Getting Closer at the Company Party4 Organization Science, Articles in Advance, pp. 1–25, © 2013 INFORMS

Parmelee 1979). Thus, based on prior work that reflectsthe assumption that shared social activities are associ-ated with closer coworker relationships, we expect that,in general, employees who integrate by attending socialevents with coworkers, bringing family members to theseevents, and discussing their nonwork lives in work con-texts should feel closer to their coworkers. Therefore,

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Integration behaviors will bepositively associated with close relationships amongcoworkers.

Personal–Professional Domain Integration andDemographic DissimilarityOverall, although we expect a positive relationshipbetween integration behaviors and closeness amongcoworkers, this relationship may be weaker for thosewho are demographically dissimilar from their cowork-ers, in part because engaging in integration behaviorscan actively highlight dissimilarity and also becausemerely being different from the majority may underminethe positive effects of integration behaviors (Bacharachet al. 2005, Phillips et al. 2009). Research on theeffects of demographic dissimilarity draws primarily onsocial identity and self-categorization theories, whichexplain how people derive their sense of self or identityand esteem from group memberships and social cate-gories (i.e., gender, race, religion) (Abrams and Hogg1990, Tajfel 1981, Tajfel and Turner 1986). Addition-ally, the similarity attraction paradigm asserts that peo-ple are more attracted to those who are similar onsalient dimensions and form relationships more easilywith those who share their demographic characteris-tics (Byrne 1971, Riordan and Shore 1997). Moreover,relationships between those with different demographiccharacteristics are often associated with relational chal-lenges including greater conflict, lower cohesion, andlower-quality communication (e.g., Jackson et al. 2003,Hoffman 1985, Pelled et al. 1999, Tsui and O’Reilly1989; for reviews, see Van Knippenberg and Schippers2007, Williams and O’Reilly 1998).

People’s close relationships or friendships tend to beformed with those who are similar to them on demo-graphic characteristics (e.g., Ibarra 1995, Mehra et al.1998, Mollica et al. 2003, Reagans 2011). It is impor-tant to note, however, that when people perceive thatrelationships with dissimilar others will enhance theirstatus, they may find it useful or preferable to form suchrelationships in organizational settings for instrumen-tal reasons (Chattopadhyay 2003, Chattopadhyay et al.2004). Indeed, Ibarra (1995) found that in work contexts,minorities often networked with dissimilar others forinstrumental reasons, but they formed close relationshipsor friendships with those who were demographicallysimilar, suggesting that there is less social interactionamong those who are demographically dissimilar. There-fore, research on intergroup relations (Allport 1954,

Pettigrew and Tropp 2006) suggests that under certainconditions, increasing contact among dissimilar individ-uals will provide individuating information and help touncover unobserved similarities, which should improverelationships. We argue, however, that even if peo-ple engage in integration behaviors (e.g., participat-ing in social activities with coworkers, bringing familymembers to work-related activities, discussing nonworkmatters with coworkers), closeness between dissimilarindividuals may not increase as much as it will for thosewho are similar to each other.

Existing research suggests two reasons why the rela-tionship between integration behaviors and closenessmay be weaker for those who are demographicallydissimilar from their coworkers. First, when dissimi-lar individuals acquire more personal information abouteach other through their integration behaviors, theymay discover similarities, but their interaction may alsohighlight differences between them. The differences dis-covered may confirm the expectations of dissimilar-ity that accompany demographic dissimilarity (Byrne1971). These differences are likely to loom large inemployees’ perceptions because people tend to givemore weight to information that confirms their preex-isting ideas or conclusions (Bazerman and Moore 2009,p. 28; Jonas et al. 2001). For example, when Phillipset al. (2006) attempted to increase group cohesion ina laboratory study by instructing participants to self-disclose and compile a list of attributes that they had incommon, the researchers found that this exercise led toan increased feeling of similarity for members of homo-geneous groups, but not for members of diverse groups.

Additionally, even when people are not directlyexchanging or disclosing information about themselves,those who are demographically dissimilar from themajority often experience a heightened awareness oftheir own demographic category (Bacharach et al. 2005,Blau and Schwartz 1997, Chatman et al. 1998, Mehraet al. 1998, Riordan and Shore 1997). This can lead toan exaggerated sense of dissimilarity such that they feelmore isolated (Jackson et al. 1995, Kanter 1977) andexperience the organizational context differently thanthose who are demographically similar to the major-ity (Bacharach et al. 2005, Chatman et al. 1998, Flynnet al. 2001). As the proportion of similar others inthe organization decreases, the distinction between in-group members (those who are demographically similar)and out-group members (those who are demographi-cally different) becomes more salient to those who arein the numerical minority. Further, relationships within-group members actually become closer and moreprevalent (Bacharach et al. 2005, Mehra et al. 1998),whereas relationships with out-group members remainmore superficial and instrumental (Ibarra 1995). Thus,because dissimilar individuals often feel a heightenedsense of distinction from others, integration behaviors

Copyright:

INFORMS

holdsco

pyrig

htto

this

Articlesin

Adv

ance

version,

which

ismad

eav

ailableto

subs

cribers.

The

filemay

notbe

posted

onan

yothe

rweb

site,includ

ing

the

author’s

site.Pleas

ese

ndan

yqu

estio

nsrega

rding

this

policyto

perm

ission

s@inform

s.org.

Dumas, Phillips, and Rothbard: Getting Closer at the Company PartyOrganization Science, Articles in Advance, pp. 1–25, © 2013 INFORMS 5

may not lead to the expected positive effects on close-ness for those who are dissimilar from their coworkers.

At first glance, these arguments appear to conflict withexisting research on intergroup relations, which suggeststhat more interaction and information exchange betweenpeople in different demographic categories can ame-liorate the problems associated with dissimilarity (i.e.,Allport 1954; Ensari and Miller 2002, 2006). This exist-ing research argues that under specified circumstances,greater interaction among members of different demo-graphic categories provides individuating informationthat can serve to reduce prejudice by changing people’sperceptions of those who are demographically dissimilarand by reducing reliance on stereotypes (Allport 1954,Ensari and Miller 2002, Miller 2002, Turner et al. 2007;for a review, see Pettigrew and Tropp 2006). It is impor-tant to note, however, that those intergroup relationsarguments focus on the reduction of prejudice or dis-crimination, rather than the formation of close relation-ships, which is the focus of this paper. We acknowledgethat the reduction of prejudice may be a precondition forthe formation of close relationships across demographicdifferences, but the reduction of prejudice does not nec-essarily mean that close relationships between dissimilarindividuals will occur. Additionally, as we noted ear-lier, some scholars suggest that providing opportunitiesfor more intimate interaction and the exchange of per-sonal, individuating information can help demograph-ically dissimilar people feel similar to each other ondeeper attributes (Harrison et al. 1998, 2002) and viewdissimilar others more accurately and completely, whichwill allow them to work better together (Ensari andMiller 2006, Polzer et al. 2002). However, these studiesassess both dissimilarity and its outcomes at the aggre-gate group level (e.g., Polzer et al. 2002; Harrison et al.1998, 2002), thus leaving uncertainty as to how personalinteraction may impact individuals differentially basedon the demography of the context and whether the indi-vidual is in the numerical majority or minority, which iswhat we study here.

In sum, we recognize existing research suggestingthat increased contact between dissimilar individuals canhave positive effects for intergroup relations. However,a number of researchers show that even when dissimilarindividuals seek to form close relationships, the chal-lenges of communicating and interacting with out-groupmembers can keep those relationships from becomingas close as relationships with similar others would be(Bacharach et al. 2005, Frey and Tropp 2006, Vorauerand Sakamoto 2006). Therefore, we argue that inte-gration behaviors may not increase close relationshipsbetween dissimilar others as much as they do for thosewho are similar to one another. Indeed, Bacharach et al.(2005) suggested that casual contact among dissimilarindividuals may help create superficial relationships butthat creating close, supportive relationships among those

who are demographically dissimilar from each other ismore difficult. Overall, although we expect that integra-tion behaviors will be associated with closer relation-ships among coworkers, we also expect that this effectwill be weaker for those who are demographically dis-similar to their coworkers.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Demographic dissimilarity willmoderate the relationship between integration behaviorsand relationship closeness among coworkers such thatintegration behaviors will be positively associated withcloser relationships for those who are demographicallysimilar to their coworkers, but this relationship will beless positive for those who are demographically dissim-ilar from their coworkers.

Quality of the Integration ExperiencePart of our objective is to test the underlying assumptionthat integration behaviors will be associated with closerrelationships among coworkers, given our expectationthat this relationship will be weaker for dissimilar indi-viduals because, in essence, they have a different expe-rience of engaging in integration behaviors. We definethe quality of the integration experience as the extent towhich employees enjoy themselves and feel comfortablewhen they are engaging in integration behaviors. This isconceptually distinct from relationship closeness. Close-ness represents an appraisal of the overall relationshipwith others, whereas the quality of employees’ experi-ences when integrating represents an appraisal of howthey feel when integrating and interacting with others.This distinction parallels a similar distinction used in theShelton et al. (2005) study of cross-race relationshipsbetween college roommates. They distinguished between“liking” one’s college roommate and the affect experi-enced when interacting with that roommate. The qualityof integration experience is a more targeted and specificdimension of a person’s experience in the workplace,and it may contribute to overall relationship closeness.Additionally, Allport’s (1954) original contact hypothe-sis considered the quality of contact to be an importantfactor for mitigating prejudice across different social cat-egories. Similarly, Voci and Hewstone (2003) found thatItalians’ attitudes toward African immigrants were asso-ciated with the quality of their interaction rather thanmerely the amount of interaction. Therefore, we arguethat the differential effect of integration behaviors onrelational closeness for dissimilar versus similar employ-ees will be explained by the quality of the experiencethey have when integrating.

Research suggests that the quality of employees’ expe-riences when engaging in integration behaviors willaffect their sense of closeness with or bonding to theircoworkers. Ingram and Morris (2007) found that peoplewho attended professional mixers were more likely totalk with someone at a mixer if they had a prior posi-tive relationship. Also, the business people attending the

Copyright:

INFORMS

holdsco

pyrig

htto

this

Articlesin

Adv

ance

version,

which

ismad

eav

ailableto

subs

cribers.

The

filemay

notbe

posted

onan

yothe

rweb

site,includ

ing

the

author’s

site.Pleas

ese

ndan

yqu

estio

nsrega

rding

this

policyto

perm

ission

s@inform

s.org.

Dumas, Phillips, and Rothbard: Getting Closer at the Company Party6 Organization Science, Articles in Advance, pp. 1–25, © 2013 INFORMS

mixer reported that they were most interested in form-ing relationships that were easy to maintain (Ingram andMorris 2007). It follows, therefore, that when peoplechoose to engage in integration behaviors, they will feelmore close to those with whom they have rewarding,enjoyable, comfortable interactions. This is consistentwith Berscheid’s (1985) earlier work on relationships ingeneral, which suggests that people are more attractedto those who provide a positive ratio of rewarding expe-riences to nonrewarding or punishing experiences. Like-wise, people consider the costs of any given interactionand are less attracted to interactions that are uncomfort-able or require greater effort. Simply stated, social inter-actions will lead to closer relationships between peopleto the extent that the quality of that interaction experi-ence is positive.

Given the existing research supporting the similar-ity attraction paradigm, as well as the above-describedexplanations of the difficulties people face when inter-acting with dissimilar others (e.g., Chatman et al. 1998,Vorauer and Sakamoto 2006, Frey and Tropp 2006,Williams and O’Reilly 1998), it is likely that forthose employees who are more demographically sim-ilar to their coworkers, attending social events willbe positively related to an enjoyable and comfortableexperience. Conversely, those who are demographicallydissimilar from their coworkers may view the eventsprimarily as opportunities to enhance their status or togather information that will be helpful for their careers,rather than as activities to be undertaken solely for plea-sure (Chattopadhyay 2003, Chattopadhyay et al. 2004,Ibarra 1995). Similarly, Phillips et al. (2009) theorizedthat in interactions with dissimilar others, people arestrategic in their decisions about integration behaviorsand may engage in self-disclosure specifically as a wayto manage status perceptions rather than purely for socialreasons. The work of these researchers supports the ideathat for those who are demographically dissimilar fromthe majority of their coworkers, higher attendance atorganizational social events or greater engagement inintegration behaviors is less likely to be associated withthe enjoyment of these activities than for those who aresimilar to their coworkers. Furthermore, the more peopleenjoy integrating, the closer they will feel to their fel-low coworkers. Therefore we expect that the quality ofthe employee’s experience while integrating will medi-ate the moderating effect of dissimilarity on the rela-tionship between integration behaviors and closeness. Inother words, the interaction of dissimilarity and inte-gration will affect closeness among coworkers indirectlythrough the quality of their experience when integrating.Figure 1 depicts all of our hypothesized relationships.

Hypothesis 3 (H3). The moderating effect of demo-graphic dissimilarity on the relationship between inte-gration behaviors and closeness will be mediated by the

Figure 1 Conceptual Model of Hypothesized Relationships

Racialdissimilarity

Integrationbehaviors

Quality ofintegrationexperience

Close coworkerrelationships/bonding social

capital

H2

H1

H3

H3

quality of the employee’s experience when engaging inintegration behaviors.

We tested our hypotheses with two studies. ForStudy 1, we compiled data from three surveys of MBAstudents that were distributed as part of an organizationalbehavior class to facilitate discussion on their workplaceexperiences. Study 1 included data that allowed us totest Hypotheses 1 and 2. To replicate these findings andto test for the mediated moderation predicted in Hypoth-esis 3, we conducted Study 2, a survey of employedU.S. adults. Study 2 also allowed us to test our hypothe-ses on a broader population of workers, characterized bygreater racial diversity. We describe each of the studiesin more detail separately below.

Study 1Sample and ProcedureWe conducted surveys of first-year MBA students intheir first academic term of classes at a Midwesternuniversity. Both full-time and part-time students par-ticipated in the study. The surveys were administeredin three rounds. The first survey, administered in thefirst week of classes, was a paper-and-pencil “getting-to-know-you” questionnaire that collected informationon the respondents’ demographic characteristics, familystructure, and work tenure. The second survey, admin-istered online four weeks later, included questions onrespondents’ integration behaviors (e.g., participation insocial activities with colleagues). The part-time studentswere instructed to complete this survey based on theircurrent work experiences, whereas the full-time studentscompleted the survey based on experiences in the jobthey held immediately prior to enrolling in the MBAprogram. The third survey, administered separately butlater in the same week as the online survey, collecteddata on the respondents’ coworkers. This third surveyrequired that respondents list up to 10 coworkers withwhom they interacted on a daily basis. Respondentsrated how close they felt to each of the individuals theylisted and also provided characteristics of their cowork-ers (e.g., race). Thus, across three separate surveys, wecollected information allowing us to determine the extent

Copyright:

INFORMS

holdsco

pyrig

htto

this

Articlesin

Adv

ance

version,

which

ismad

eav

ailableto

subs

cribers.

The

filemay

notbe

posted

onan

yothe

rweb

site,includ

ing

the

author’s

site.Pleas

ese

ndan

yqu

estio

nsrega

rding

this

policyto

perm

ission

s@inform

s.org.

Dumas, Phillips, and Rothbard: Getting Closer at the Company PartyOrganization Science, Articles in Advance, pp. 1–25, © 2013 INFORMS 7

to which respondents integrated by incorporating aspectsof their nonwork lives into work, how close they felt totheir coworkers, and how racially dissimilar they werefrom their coworkers.

A total of 228 respondents completed all three sur-veys for a response rate of 51%. Because our analysisfocused on the demographic category of race, we omit-ted international students from our analyses, becausethe typical U.S. racial descriptors may hold differentmeanings for those from other countries. After filter-ing out the international students, and after listwisedeletion for missing data, the final number of obser-vations used in the analysis was 165. Of this finalgroup of respondents, 38% were women. Ten percentof the respondents were underrepresented minorities(African Americans, Native Americans, Hispanic/LatinoAmericans, and “other” race or ethnic background com-bined), 13% were Asian American, and 77% werewhite/Caucasian. Forty percent of the respondents werepart-time MBA students who were working full-timeduring the day. The average age of the respondents was27.95. A comparison of this sample’s demographic char-acteristics to the population of respondents, based onstatistics provided by the school, suggests that the sam-ple is representative of the population.

Dependent, Independent, and Moderator Variables

Closeness. Our dependent variable was respondents’feelings of closeness to their coworkers, defined as con-nection and bonding. To capture this variable, we useda measure of average closeness, used in prior studies byIbarra (1995), Podolny and Baron (1997), and Reagans(2011). These researchers asked respondents to indicateon a five-point scale how close they felt to each of theircolleagues or fellow organizational members listed in anetwork survey. We followed their technique of askingrespondents to indicate how close they felt to each oftheir listed coworkers on a scale of 1 (not at all close)to 5 (very close) and averaging the respondents’ rat-ings of their closeness with each colleague to determinetheir overall sense of closeness with their coworkers.Respondents answered this question for up to 10 differ-ent coworkers separately, depending on how many theylisted. One of the advantages of this measure is thatit allowed us to collect granular information about therespondents’ relationships with each of their coworkers.This measure was collected via the third survey.

Integration Behaviors. Our primary independent vari-able was integration behaviors. To capture this construct,we sought a measure that both (a) addressed behaviorsthat integrate by incorporating more of the employee’spersonal life into the organization and (b) tapped into theinterpersonal aspect of integration described by boundarytheorists such as Nippert-Eng (1996). Existing integra-tion scales typically consider whether employees blur

the boundary between their personal and professionallives more generally, but they often fail to distinguishthe direction of integration (e.g., Desrochers et al. 2005).Other scales distinguish the direction but do not cap-ture enough of the interpersonal aspect of integrationthat we sought to measure (e.g., Powell and Greenhaus2010). Other measures focus on employees’ preferencesfor integration rather than asking about specific behav-iors (Kreiner 2006, Rothbard et al. 2005). As a result, wedeveloped three items to measure respondents’ reportedintegration behaviors. These items were based on thebehaviors described by Nippert-Eng (1996) as integrat-ing practices—that is, employee participation in com-pany social events, inclusion of their families in suchevents, and discussion of their personal lives at work.Our measure is also consistent with the social interac-tion component of the social integration index used bydiversity researchers (e.g., O’Reilly et al. 1989). There-fore, our items are as follows: “How much do you par-ticipate in company sponsored or informal social activ-ities?” “To what extent do you take members of yourfamily or nonwork friends and companions to company-sponsored or informal work-related gatherings?” And“How much do you talk about your nonwork life withcoworkers?” The response scale ranged from 1 (not at all)to 7 (a great deal).

These items serve as formative (Edwards and Bagozzi2000) or causal (Bollen and Lennox 1991) indicators.Note that items that comprise formative indices are notnecessarily expected to be highly correlated with eachother (Bollen and Lennox 1991, Edwards and Bagozzi2000, MacKenzie et al. 2005). MacKenzie et al. (2005,p. 728) explicitly stated,

For formative-indicator constructs, the concept of internalconsistency is not appropriate as a measure of reliabil-ity because the indicators are not assumed to be reflec-tions of an underlying latent variable. Indeed, as notedby Bollen and Lennox (1991), formative indicators maybe negatively correlated, positively correlated, or com-pletely uncorrelated with each other. Consequently, Cron-bach’s alpha and Bagozzi’s index should not be used toassess reliability and, if applied, may result in the omis-sion of indicators that are essential to the domain of theconstruct.

Our integration behaviors items meet the criteria forformative indicator scales as described by MacKenzieet al. (2005) in that they represent defining character-istics that collectively explain the meaning of the con-struct, and the items each capture a unique aspect of theconceptual domain. For example, participation in socialactivities with coworkers and bringing family mem-bers to company-sponsored outings are both integrationbehaviors; however, these two distinct behaviors may notnecessarily covary. Because the behaviors are related andfall squarely within the realm of integration behaviorsspecified by boundary theorists (Ashforth et al. 2000,

Copyright:

INFORMS

holdsco

pyrig

htto

this

Articlesin

Adv

ance

version,

which

ismad

eav

ailableto

subs

cribers.

The

filemay

notbe

posted

onan

yothe

rweb

site,includ

ing

the

author’s

site.Pleas

ese

ndan

yqu

estio

nsrega

rding

this

policyto

perm

ission

s@inform

s.org.

Dumas, Phillips, and Rothbard: Getting Closer at the Company Party8 Organization Science, Articles in Advance, pp. 1–25, © 2013 INFORMS

Nippert-Eng 1996), they can be combined to create ascale. MacKenzie et al. (2005) suggested that for for-mative indicators, the significance and strength of thefactor loadings reflect item validity. Therefore, to testthe validity of the items in this integration behaviorsscale, we used a separate sample consisting of 109 MBAstudents from the same institution as the main study par-ticipants, but these separate respondents did not partic-ipate in the main study.1 We conducted an exploratoryfactor analysis to determine whether these items loadedtogether on a single factor. The analysis yielded one fac-tor with an eigenvalue greater than 1. The three itemsloaded onto the factor at 0.81, 0.69, and 0.78, respec-tively. To determine the significance of these factor load-ings, we ran a confirmatory factor analysis that indicatedthat these items loaded significantly onto a single factor,with all t-values greater than 3.05 (p < 0001). Thus, wedecided to combine these items into an index of integra-tion behaviors. In the sample used for the main analysesin Study 1, the factor loadings for the integration behav-ior items were 0.69, 0.76, and 0.77, respectively. Theseall loaded significantly onto a single factor with t-valuesgreater than 3.39 (p < 00001). This integration behaviorsmeasure was collected in the second survey administeredto the MBA students.

In addition, because this was a new measure, weincluded an open-ended question on the main surveyto collect more specific information about the kinds ofintegrating activities or events that respondents werereferring to when they responded to the item askingabout their participation in company social activities.Participants were asked to “please describe the natureof the social gatherings you attend,” and they wereprovided with a multiline text field to type in theirresponses. Ninety percent of the survey respondentsanswered this question. For exploratory purposes, theopen-ended responses were coded for the number of dif-ferent activities listed, which we use as a control vari-able and discuss in more detail below. The responseswere also categorized into different types of activities.We report these categories in the Results section.

Racial Dissimilarity. We examined racial dissimilar-ity as a moderator. Using the demographic data providedin the respondents’ list of coworkers, we computed therelational demography score as a measure of respon-dents’ racial dissimilarity from their coworkers (Tsuiet al. 1992). The possible scores on this measure rangefrom 0 to approaching 1, but not reaching 1. Highernumbers indicate that the respondent is more raciallydissimilar from his or her coworkers, whereas lowernumbers indicate that the respondent is more similarto his or her coworkers. This measure was constructedbased on information collected in the third survey.

Control VariablesWe collected several variables to serve as controls in ourdata analysis to meet three objectives. First we wanted tocontrol for established factors that affect an employee’srelationships with their coworkers. Second, we tookinto account individual characteristics of the respon-dent, including factors that are related to racial dissim-ilarity. Third, we wanted to control for the contextualfactors that would be related to the respondents’ integra-tion behaviors. Therefore, we sought to include controlvariables that could help eliminate potential alternativeexplanations for our effects and also address some ofthe more predictable questions that readers might haveabout our data.

We controlled for demographic factors and charac-teristics of the respondents, which were collected inthe first survey. Past research on work and nonworkroles has shown that men and women may have differ-ent experiences in the ways they approach their workand nonwork lives (Andrews and Bailyn 1993, Rothbard2001, Rothbard and Brett 2000). Men and women alsodiffer in their responses to demographic dissimilarity(Toosi et al. 2012). Therefore, we controlled for sexin these analyses. We also controlled for the respon-dents’ age as well as parental status and marital statusbecause these factors all affect an employee’s experienceof the relationship between their work and nonworklives (Gordon and Whelan 1998, Martins et al. 2002).We controlled for the respondents’ tenure in their workorganization because the length of time that peoplehave worked with each other affects their relationships(Harrison et al. 1998, 2002; Riordan and Shore 1997)and can have a considerable impact in demographicallydiverse settings (Joshi and Roh 2009). We also con-trolled for whether the respondents were full-time orpart-time MBA students in an attempt to capture andcontrol for variance arising from the different employ-ment status of the respondents. Finally, because ourhypotheses focused on racial dissimilarity, we also con-trolled for the respondents’ race or ethnic background;this is important because these characteristics can affectan individual’s experience of demographic dissimilarity(Chattopadhyay 1999, Tsui et al. 1992). We includedtwo dummy variables for race. The first race dummyvariable coded all underrepresented minority categories(African American, Native American, Hispanic/LatinoAmerican, and other race) as 1 and all others as 0. Thesecond race dummy variable coded all respondents whoselected Asian American as 1 and all others as 0. Wecoded these groups separately, because these groups areknown to experience the workplace differently and havedifferent levels of status in American society that mayaffect integration behaviors (Leslie 2008, O’Reilly et al.1998, Phillips et al. 2009). White/Caucasian was theomitted category.

Copyright:

INFORMS

holdsco

pyrig

htto

this

Articlesin

Adv

ance

version,

which

ismad

eav

ailableto

subs

cribers.

The

filemay

notbe

posted

onan

yothe

rweb

site,includ

ing

the

author’s

site.Pleas

ese

ndan

yqu

estio

nsrega

rding

this

policyto

perm

ission

s@inform

s.org.

Dumas, Phillips, and Rothbard: Getting Closer at the Company PartyOrganization Science, Articles in Advance, pp. 1–25, © 2013 INFORMS 9

In addition to controlling for the above-describeddemographic factors, we also sought to take into accounta number of contextual and structural factors of the worksetting that may affect coworker relationships. Accord-ingly, we controlled for the number of coworkers respon-dents listed on the third survey because group size hasbeen shown to affect relationships among group mem-bers (Carron and Spink 1995, Chattopadhyay 1999).Additionally, we controlled for the demography of thework setting on characteristics other than race, so weincluded measures of the respondents’ dissimilarity fromtheir coworkers with regard to sex and status in theorganization, both of which have been shown to affectrelationships with coworkers and group outcomes inpast research (Chattopadhyay 1999, Chattopadhyay et al.2010). To measure sex dissimilarity, we used the samerelational demography measure used for racial dissimi-larity (Tsui et al. 1992). For status dissimilarity, whenrespondents listed their coworkers, they also providedinformation on whether each coworker listed was apeer, subordinate, or superior. From this information,we computed a measure reflecting the proportion ofthe respondents’ colleagues who were different in sta-tus from the respondent (i.e., superiors or subordinates)consistent with the status proportion measures used byIbarra (1995). A higher number on this measure indi-cates that the respondent is primarily different in statusfrom his or her coworkers. We also wanted to accountfor the general organizational norms for socializing,so we asked respondents the following question: “Howmuch does your company have social activities, eithercompany sponsored or informal?” The response scaleranged from 1 (not at all) to 7 (a great deal), and thisitem was included as a control variable in our analyses.We also controlled for the number of activities respon-dents attended, using a count of the different types ofsocial activities listed by the respondent in the open-ended question. This measure captured not the frequencyof attending events but rather the breadth and variety ofactivities the respondents attended, which might meanthey are having interpersonal contact with a broaderset of colleagues, thus potentially affecting their senseof closeness.

AnalysisTo test our hypotheses, we used ordinary least squares(OLS) regression analysis. We first entered the controlvariables and then the independent variables to assessmain effects. We then entered the interaction term asa final step in the analysis to allow us to determinethe change in variance explained by adding the inter-action term. Given that we predicted interaction effectsamong continuous variables, we followed the procedurerecommended by Aiken and West (1991) to assess theinteraction effects. Specifically, we used centered vari-ables to compute the interaction terms. Centering the

variables entails subtracting the means from the variableto remove the multicollinearity introduced by interactionterms. Furthermore, we used the regression coefficientsto plot and interpret the form of each interaction (Aikenand West 1991).

Results: Study 1Table 1 includes descriptive statistics and correlationsamong our study variables. The correlation table revealsseveral interesting patterns. Single employees were lesslikely to report integrating work and nonwork. Com-pared with full-time students, part-time students listeda broader variety of organizational social events, wereolder, were more likely to be married, were more likelyto have children, and listed more coworkers in their sur-vey. Closeness was positively correlated with integrationbehaviors. However, not surprisingly, closeness was neg-atively correlated with the number of coworkers listed.

In addition, we found that respondents reportedparticipating in a variety of social activities in theirorganizations. In response to the open-ended questionrequesting a description of the types of social activi-ties they attended, respondents listed up to 11 activities,with the mean number of activities listed being 3.40(SD = 1082). For descriptive purposes, we categorizedthe activities into three different types of activities. Theywere (1) company-sponsored social events, comprising50.25% of activities listed (e.g., holiday parties, com-pany picnics, sporting events); (2) employee-initiatedsocial events, comprising 41.45% of activities listed(e.g., going for drinks after work, baby/wedding show-ers, lunch with coworkers); and (3) company-sponsoreddevelopment or service activities (e.g., team-buildingretreats, professional development seminars, communityservice), comprising 8.29% of activities listed. The threespecific activities listed most frequently were happyhours/drinking outings with colleagues (35.27%), holi-day parties (25.04%), and company-sponsored outingsto sports or theater events (13.05%).

Hypothesis 1 predicted that those who reported higherlevels of integration behaviors would report closer rela-tionships with their coworkers than would respondentswho reported lower levels of integration. As shown inTable 2, Step 2, this hypothesis was supported. Integra-tion behaviors were positively and significantly relatedto closeness (�= 0018, p < 0005).

Hypothesis 2 predicted that racial dissimilarity wouldmoderate the relationship between integration behaviorsand closeness. As shown in Table 2, Step 4, this hypoth-esis was also supported.2 The positive main effect ofintegration on closeness is qualified by a negative andsignificant interaction between racial dissimilarity andintegration (� = −0018, p < 0005). Plotting the resultsand evaluating the simple slopes reveals that, as pre-dicted, integration was positively associated with close-ness only for individuals who were demographically

Copyright:

INFORMS

holdsco

pyrig

htto

this

Articlesin

Adv

ance

version,

which

ismad

eav

ailableto

subs

cribers.

The

filemay

notbe

posted

onan

yothe

rweb

site,includ

ing

the

author’s

site.Pleas

ese

ndan

yqu

estio

nsrega

rding

this

policyto

perm

ission

s@inform

s.org.

Dumas, Phillips, and Rothbard: Getting Closer at the Company Party10 Organization Science, Articles in Advance, pp. 1–25, © 2013 INFORMS

Table

1Study1:

CorrelationsAmongStudyVariablesan

dDes

criptive

Statistics

12

34

56

78

910

1112

1314

1516

1.Se

x(1

=fe

mal

e)1

2.Age

−00

23∗∗

13.

Und

errepres

entedminority

a00

0700

051

4.Asian

American

a00

0000

03−

0013

15.

Marita

lstatus

(1=

sing

le)

0017

∗−

0027

∗∗

−00

0700

041

6.Pa

rental

status

(1=

pare

nt)

−00

1400

53∗∗

0002

0005

−00

35∗∗

17.

Part-time/full-tim

eMBA

−00

0500

23∗∗

0009

0002

−00

34∗∗

0033

∗∗

1(1

=pa

rttim

e)8.

Tenu

re(in

mon

ths)

−00

1300

47∗∗

0006

−00

06−

0014

0017

∗00

041

9.No.

ofco

worke

rslisted

−00

0400

20∗

−00

0200

06−

0023

∗∗

0013

0027

∗∗

0016

∗1

10.Status

diss

imila

rity

−00

0900

1100

00−

0001

0005

0006

−00

05−

0002

0004

111

.Se

xdiss

imila

rity

0040

∗∗

−00

1000

1000

0100

04−

0009

0005

−00

0800

22∗∗

0016

∗1

12.Org.s

ocializingno

rms

0006

−00

08−

0009

0005

0007

−00

12−

0011

−00

1200

0400

0600

061

13.Num

berof

activ

ities

0005

−00

04−

0002

0009

0003

−00

09−

0024

∗∗

0003

0016

∗00

0800

1200

37∗∗

114

.Integrationbe

haviors

0009

−00

05−

0015

0008

−00

17∗

0002

−00

0200

0400

0900

02−

0001

0040

∗∗

0023

∗∗

115

.Rac

iald

issimila

rity

0000

0011

0038

∗∗

0055

∗∗

−00

1300

1500

08−

0001

0024

∗∗

−00

0100

11−

0009

0002

−00

091

16.Close

ness

0013

−00

15−

0005

−00

0100

08−

0014

−00

09−

0006

−00

19∗

0002

−00

1000

1300

0800

21∗∗

−00

111

Mea

n00

3827

095

0010

0013

0057

0010

0040

4003

480

9000

6000

5340

2530

2840

3200

4030

51SD

0049

3002

0030

0033

0050

0030

0049

2700

410

7700

2300

2310

3510

6710

1100

3200

53

Note.

N=

165.

aFo

rth

edu

mm

yva

riabl

esfo

rra

ce,un

derrep

rese

nted

minority

isco

ded

as1

for

Afri

can

Am

eric

an,

Nat

ive

Am

eric

an,

His

pani

c/La

tino

Am

eric

an,

and

othe

rra

ce.Asian

American

isco

ded

as1

for

allr

espo

nden

tsw

hose

lect

edA

sian

Am

eric

an.

∗p<

0005

;∗∗p<

0001

.

Copyright:

INFORMS

holdsco

pyrig

htto

this

Articlesin

Adv

ance

version,

which

ismad

eav

ailableto

subs

cribers.

The

filemay

notbe

posted

onan

yothe

rweb

site,includ

ing

the

author’s

site.Pleas

ese

ndan

yqu

estio

nsrega

rding

this

policyto

perm

ission

s@inform

s.org.

Dumas, Phillips, and Rothbard: Getting Closer at the Company PartyOrganization Science, Articles in Advance, pp. 1–25, © 2013 INFORMS 11

Table 2 Study 1: Closeness Regressed on IntegrationBehaviors and Racial Dissimilarity

Step 1 Step 2 Step 3 Step 4

ControlsSex (1= female) 0�18∗ 0�15∗ 0�15† 0�16†

Age −0�08 −0�05 −0�05 −0�03Underrepresented minority −0�04 −0�02 −0�01 −0�03Asian American −0�01 −0�02 −0�02 0�02Marital status (1= single) −0�02 0�02 0�02 0�00Parental status (1= parent) −0�08 −0�09 −0�09 −0�10Tenure (in months) 0�03 0�01 0�01 0�00No. of coworkers listed −0�15† −0�16† −0�16† −0�19∗

Status dissimilarity 0�08 0�07 0�07 0�06Sex dissimilarity −0�18∗ −0�16† −0�16† −0�14Org. socializing norms 0�09 0�02 0�02 0�00Number of activities 0�08 0�06 0�06 0�06Part-time/full-time MBA 0�04 0�04 0�04 0�05

(1= part time)Main effects

Integration behaviors 0�18∗ 0�18∗ 0�16†

Racial dissimilarity −0�01 −0�03Interaction effects

Integration −0�18∗

×Racial dissimilarity

R2 0�03 0�05 0�05 0�07�R2 0�03∗ 0�00 0�03∗

Notes. N = 165. The coefficients reported in each column are stan-dardized beta coefficients. The adjusted R2 for each step of theequation is reported at the bottom of the table along with the �R2

from adding each set of variables to the equation.†p < 0�10; ∗p < 0�05.

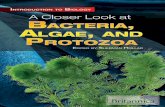

similar to their coworkers (t = 2�12, df = 143, p < 0�05).In contrast, individuals who were dissimilar from theircoworkers did not experience greater closeness whenthey integrated more (t = 0�07, df = 143, not signifi-cant), as illustrated in Figure 2.

Discussion: Study 1The results of our first study supported both Hypothe-ses 1 and 2. Overall, there was a positive relationshipbetween integration behaviors and closeness, which was

Figure 2 Study 1: Effect of Integration Behaviors onCloseness Moderated by Racial Dissimilarity

3.0

3.2

3.4

3.6

3.8

4.0

4.2

4.4

Low High

Clo

sene

ss

Integration behaviors

Low dissimilarity

High dissimilarity

qualified by an interaction effect of racial dissimilarity.Integration behaviors were positively related to closenessonly among coworkers who were racially similar to theircolleagues; however, this effect did not hold for thosewho were racially dissimilar from their colleagues.

Our significant results in Study 1 raised questionsthat we wanted to explore further. First, one limitationin interpreting our central finding is that our sampleincluded a small percentage of underrepresented minori-ties. Although we controlled for the respondents’ racewhen testing our hypotheses, we remain aware that racialdissimilarity can have different effects on people basedon their racial or ethnic background (Tsui et al. 1992).We ran additional analyses exploring potential three-way interactions between integration behaviors, eachdemographic group (i.e., Asians, Caucasians, underrep-resented minorities) separately, and demographic dissim-ilarity. In other words, we wanted to determine whetherthe effects of demographic dissimilarity were differentacross racial groups. This supplemental analysis yieldedno significant effects and therefore supports the ideathat our findings are driven by racial dissimilarity ratherthan the experiences of a particular racial group. How-ever, we sought to test our hypotheses with a secondstudy using a sample with a higher percentage of under-represented minorities. Second, we wanted to test ourhypotheses with a richer operationalization of close rela-tionships that would provide further insight into howintegration behaviors and racial dissimilarity affect con-nections between coworkers. Third, and perhaps mostimportantly, we needed a second study with data thatwould allow us to test Hypothesis 3, which predicted thatthe quality of respondents’ experience when integratingwould mediate our significant interaction effect.

Study 2Sample and ProcedureFor Study 2, we administered a survey to a panel ofparticipants compiled by Qualtrics, an organization thatprovides software to host online surveys and also assistsresearchers in identifying research participants. Qualtricshas access to over six million U.S. adults who haveexpressed willingness to participate in research and arecompensated by earning points that can be used toredeem products and services from online merchants.Similar to our first study, we administered the surveyin rounds. The first round of the survey contained theindependent, mediator, and control variables. The secondround of the survey was administered two weeks afterthe close of the first round and contained the moderatorand dependent variables.

We sought a survey administration that would yield apercentage of underrepresented minorities that is morerepresentative of the U.S. population, and we requestedthat the survey organization distribute the survey to

Copyright:

INFORMS

holdsco

pyrig

htto

this

Articlesin

Adv

ance

version,

which

ismad

eav

ailableto

subs

cribers.

The

filemay

notbe

posted

onan

yothe

rweb

site,includ

ing

the

author’s

site.Pleas

ese

ndan

yqu

estio

nsrega

rding

this

policyto

perm

ission

s@inform

s.org.

Dumas, Phillips, and Rothbard: Getting Closer at the Company Party12 Organization Science, Articles in Advance, pp. 1–25, © 2013 INFORMS

a sample comprising at least 25% underrepresentedminorities. We also specified that respondents to our sur-vey must be full-time employees. Of the 10,544 peo-ple whom Qualtrics invited to participate, 1,178 openedthe survey invitation message. Consistent with the Longet al. (2011) use of a Qualtrics sample, as well asBrown and Robinson’s (2011) use of a similar onlinesurvey organization, we consider the response rate basedon the number of participants who opened the surveyinvitation. Of those 1,178 individuals, 601 completedthe first part of the survey for a 51% response rate.The second part of the survey yielded 429 responses,which is 71% of those who completed the first partof the survey. Thus, our overall response rate acrossboth surveys was 36%. These response rates are consis-tent with both conventional and online survey responserates (Baruch and Holtom 2008, Cook et al. 2000,Long et al. 2011). After combining the responses forthe two separate surveys (parts 1 and 2) and after list-wise deletion for missing data across both surveys, thefinal sample included in the analysis is 141. Of thisfinal group of respondents, 57% were women. Twenty-four percent were underrepresented minorities (AfricanAmericans, Native Americans, Hispanic/Latino Ameri-cans, and other race/ethnic backgrounds combined), 8%were Asian American, and 68% were white/Caucasian.The average age of the respondents was 40.14.

A comparison of the final sample with the popu-lation of members invited to participate reveals thatthey had comparable percentages of women and AsianAmericans. Our final sample had fewer underrepresentedminorities, which we intentionally oversampled, and ourfinal sample was older than the invited population. How-ever, we controlled for these factors in our analyses, andthey did not affect the results. Additionally, we com-pared those who completed only the first part of thesurvey with those who completed both parts. There wereno statistical differences in their responses to the inde-pendent and mediator variables.

Dependent, Independent, and Moderator VariablesFor our dependent variable, we captured closeness byusing the bonding social capital scale developed byCarmeli et al. (2009).3 They defined and operational-ized this construct as close, caring, and supportive rela-tionships among group members. The emphasis of theirstudy was on “behaviors that might generate close andcollaborative internal relationships within the group”(Carmeli et al. 2009, p. 1554). Therefore, this mea-sure tapped into the notion of “closeness” that we mea-sured in Study 1, but it also captured additional aspectsof close coworker relationships. This four-item measureasked respondents to indicate (1) how close they feel totheir coworkers, as did our initial average closeness mea-sure from Study 1, but it is a broader scale also askingrespondents to indicate how much they (2) can count ontheir colleagues, (3) get help from their colleagues, and

(4) feel a sense of caring for their colleagues at work.These items were measured on a five-point scale rangingfrom 1 (not at all) to 5 (a great extent). The reliabilityfor this scale was good (�= 0091).

For our independent variable, we used the same inte-gration behaviors scale used in Study 1. Recall that thisis a formative index (MacKenzie et al. 2005). The factorloadings for the items in this sample were 0.87, 0.88,and 0.75, respectively. The confirmatory factor analy-sis showed that the items all loaded significantly ontoone factor at a minimum of t = 11083 (p < 00001). Forour moderator variable, racial dissimilarity, we used thesame relational demography measure used in Study 1(Tsui et al. 1992).

Mediator and Control VariablesThe data collected in Study 2 allowed us to testthe mediated moderation predicted in Hypothesis 3,whereby the interaction of dissimilarity and integra-tion behaviors would affect closeness indirectly throughthe quality of the respondents’ integration experience.To measure the quality of the integration experience, weadapted the two-item scale from the study by Sheltonet al. (2005) in which they assessed the degree to whichtheir study participants enjoyed interacting with theirassigned partners during the experiment. Specifically,we adapted these items to refer to respondents’ interac-tion with their coworkers. Additionally, to create a morerobust scale, we developed two new items and addedthem to the Shelton et al. (2005) scale. Specifically, theitems ask (1) “How much do you enjoy getting to knowyour coworkers at these events?” (2) “How much doyou enjoy the interaction with your coworkers at theseevents?” (3) “Do you enjoy participating in these activ-ities?” And (4) “How comfortable are you with beingthere?” Responses were measured on a seven-point scaleranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (to a great extent). Weconducted an exploratory factor analysis on these itemsusing a separate Qualtrics sample of 100 employed U.S.adults.4 The analysis yielded factor loadings of 0.89,0.90, 0.92, and 0.95, respectively. On the test sample,the reliability of the items was good (�= 0096). There-fore we combined the items to create a scale. In thestudy sample, the reliability of the items was also good(� = 0097). We used identical control variables acrossthe two studies (with the exception of the inclusion ofthe part-time or full-time MBA student control in Study1) because we wanted a consistent test of our hypothesesacross the two samples.

Finally, to test for the discriminant validity of integra-tion behaviors, quality of integration experiences, andbonding social capital, we conducted confirmatory fac-tor analyses on the sample used for the main analyses inStudy 2. We compared our three-factor model (X26417=190034, p < 00001, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0097,standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = 0005)to a one-factor model with the items from all three scales

Copyright:

INFORMS

holdsco

pyrig

htto

this

Articlesin

Adv

ance

version,

which

ismad

eav

ailableto

subs

cribers.

The

filemay

notbe

posted

onan

yothe

rweb

site,includ

ing

the

author’s

site.Pleas

ese

ndan

yqu

estio

nsrega

rding

this

policyto

perm

ission

s@inform

s.org.

Dumas, Phillips, and Rothbard: Getting Closer at the Company PartyOrganization Science, Articles in Advance, pp. 1–25, © 2013 INFORMS 13

loaded onto one latent variable (X26447 = 11048094,p < 00001, CFI = 0084, SRMR = 0016). The one-factormodel was a significantly worse fit to the data thanthe three-factor model (X2 difference, 3df = 85806). Wealso compared our three-factor model to three differ-ent combinations of two-factor models to be certain thatthese three scales were distinct from each other. Thefirst two-factor model separated the integration behav-ior items onto their own latent factor but combined thequality of integration experience and bonding social cap-ital items together onto another latent factor (X26437 =

694085, p < 00001, CFI = 0084, SRMR = 0019). Thistwo-factor model fit the data significantly worse thanour three-factor model (X2 difference, 2df = 504051,p < 0001). The second two-factor model separated thebonding social capital items onto their own latent fac-tor but combined the integration behavior and qualityof integration experience items together onto anotherlatent factor (X26437 = 232091, p < 00001, CFI = 0096,SRMR = 0005). This model also fit the data significantlyworse than our three-factor model (X2 difference, 2df =

42057, p < 0001). The third two-factor model separatedthe quality of integration experience items onto theirown latent factor but combined the integration behaviorand bonding social capital items together onto anotherlatent factor (X26437= 11005015, p < 00001, CFI = 0085,SRMR = 0016). This two factor model was a signifi-cantly worse fit to the data compared with our three-factor model (X2 difference, 2df = 814081, p < 00001).Therefore the confirmatory factor analysis and nestedmodel X2-difference testing suggest that these threescales are distinct and tap into different constructs.

AnalysisWe used the same OLS regression procedure used inStudy 1 to test Hypotheses 1 and 2. To test Hypothesis 3,the mediated moderation prediction, we used the PRO-CESS macro by Andrew Hayes (available for downloadat http://www.afhayes.com). Specifically, the PROCESSmacro allowed us to test our mediated moderation byevaluating the indirect effect of the product of integrationbehaviors and racial dissimilarity on closeness mediatedthrough the quality of the integration experience (seeModel 8 in Hayes 2012). Accordingly, we entered all ofour variables, including control variables, into the PRO-CESS syntax. We specified integration behaviors as ourindependent variable, racial dissimilarity as the moder-ator, bonding social capital as the dependent variable,and quality of integration experience as the mediator.The PROCESS command was run with bootstrappingspecified at 5,000 samples.

Results: Study 2Table 3 contains the descriptive statistics and correla-tions for the study variables. Similar to Study 1, wefound that respondents reported participating in a vari-ety of social activities in their organizations. In response

to the open-ended question requesting a description ofthe types of social activities they attended, respondentslisted up to six activities, with the mean number of activ-ities listed being 1.88 (SD = 0097). Using the categoriesfrom Study 1 to group the activities listed by respon-dents, we found that 64.96% of activities reported werecompany-sponsored social activities (e.g., holiday par-ties and company picnics), 27.26% of activities wereemployee-initiated social events (e.g., going for drinksafter work), and the remainder included a number ofdifferent types of activities including attending profes-sional development seminars, spiritual activities, andaffinity groups.

Hypothesis 1, predicting that those who reported moreintegration behaviors would also feel closer to their col-leagues, was supported. As shown in Table 4, Step 2,integration behaviors were significantly and positivelyrelated to bonding social capital (� = 0030, p < 0001).Hypothesis 2, predicting that racial dissimilarity wouldmoderate the relationship between integration behaviorsand closeness among colleagues, was also supported.5

As shown in Table 4, Step 4, the interaction term ofintegration behaviors and racial dissimilarity was signif-icantly and negatively related to bonding social capital(� = −0018, p < 0005).6 Plotting the results and evalu-ating the simple slopes revealed that, as predicted, forindividuals who were racially similar to their cowork-ers, integration behaviors were positively associatedwith higher bonding social capital (t = 3079, df = 125,p < 00001). In contrast, for those individuals who weredissimilar from their coworkers, this positive effect wasattenuated; integration behaviors were not significantlyassociated with higher bonding social capital (t = 1027,df = 125, not significant), as illustrated in Figure 3.

Hypothesis 3 predicted that the quality of the respon-dents’ experiences when integrating—how comfortablethey felt and how much they enjoyed engaging in inte-gration behaviors with their coworkers—would mediatethe significant interaction effect, or that the interac-tion of dissimilarity and integration behaviors wouldaffect the closeness of coworker relationships indirectlythrough the quality of the respondents’ experiences whenintegrating. The PROCESS macro tests for mediatedmoderation by constructing the indirect effect of theinteraction on the dependent variable via the media-tor. For descriptive purposes, the PROCESS macro alsoprovides tests of the effect of the interaction on themediator and the effect of the mediator on the out-come variable. First, these results revealed a signifi-cant interaction effect of integration behaviors and racialdissimilarity on our mediator variable, quality of inte-gration experience (B = −0048, SE = 0021, p < 0005).Specifically, following the pattern that we saw in thetest of Hypothesis 2, the relationship between integra-tion behaviors and quality of experience was more pos-itive for those respondents who were similar to their

Copyright:

INFORMS

holdsco

pyrig

htto

this

Articlesin

Adv

ance

version,

which

ismad

eav

ailableto

subs

cribers.

The

filemay

notbe

posted

onan

yothe

rweb

site,includ

ing

the

author’s

site.Pleas

ese

ndan

yqu

estio

nsrega

rding

this

policyto

perm

ission

s@inform

s.org.