GalántaiTánkoc(Dances 06-13 Kavakos:Layout 1 6/4/13 · PDF fileSeveral volumes...

Transcript of GalántaiTánkoc(Dances 06-13 Kavakos:Layout 1 6/4/13 · PDF fileSeveral volumes...

New York Philharmonic30

Galántai Tánkoc (Dancesof Galánta)

Zoltán Kodály

Zoltán Kodály achieved eminence as a com-poser, ethnomusicologist, and educator, and allof these strands proved interrelated throughmost of his career. As the son of a frequentlytransferred stationmaster for the Austro-Hungarian Imperial Railroads, Kodály spent hisearly years in a succession of small Hungariantowns, some of which would later be reas-signed to Czechoslovakia. He expressed de-light in the Magyar folk music that surroundedhim and simultaneously developed an interestin mainstream European chamber music. Hisparents were enthusiastic musical amateurs,and Kodály learned piano, violin, viola, andcello well enough to perform credibly oneach — not bad preparation for a composerin the making. In the course of studies at theBudapest Academy of Music he grew in-creasingly fascinated by the traditional musicof his native country. He received diplomasin composition (in 1904) and teaching(1905), and in 1906 he was awarded adoctorate in musicology, culminating in hisdissertation Strophic Struc-ture in the Hungarian FolkSong. Béla Bartók, whoseopinion, emanating fromthe apex of 20th-centuryHungarian music, holdsconsiderable authority,wrote of Kodály’s work:

If I were to name thecomposer whose worksare the most perfect em-bodiment of the Hungar-ian spirit, I would answer,Kodály. His work proveshis faith in the Hungarian

spirit. The obvious explanation is that allKodály’s composing activity is rooted only inHungarian soil, but the deep inner reason ishis unshakable faith and trust in the con-structive power and future of his people.

The three disciplines of composition,teaching, and musicology — often uneasycounterparts — coexisted and reinforced oneanother in what would become Kodály’striple legacy. He joined with his great com-patriot and lifelong friend Bartók in organiz-ing trips around the countryside to collectfolk songs. As with Bartók, the musical ma-terial of these folk pieces deeply inspired thelanguage of Kodály’s original compositions.After polishing his compositional skills withthe help of a post-graduate grant in Paris(where he studied with Charles-Marie Widor,made the acquaintance of Debussy, andgenerally widened his awareness of the lat-est compositional trends), Kodály returned toBudapest. Reestablished in his native coun-try, he taught at his alma mater, wrote musiccriticism for newspapers and magazines (in-cluding important analyses of Bartók’sworks), edited and published folk-song col-lections, and continued to compose.

In Short

Born: December 16, 1882, in Kecskemét, Hungary

Died: March 6, 1967, in Budapest

Work composed: 1933; dedicated to the Budapest Philharmonic Societyon its 80th birthday

World premiere: October 23, 1933, in Budapest, Ernö von Dohnányi conduct-ing the Budapest Philharmonic Society

New York Philharmonic premiere: March 4, 1937, Artur Rodzinski, conductor

Most recent New York Philharmonic performance: November 16, 2006,at the Seoul Arts Center, Seoul, South Korea, Lorin Maazel, conductor

Estimated duration: ca. 16 minutes

06-13 Kavakos:Layout 1 6/4/13 4:17 PM Page 30

31June 2013

The best known of Kodály’s works, at leastoutside Hungary, are his orchestral scores,including such shimmering displays ofmelody and color as the evocative Dances ofGalánta. The immediate roots of this workmight be traced to 1927, when Kodály wrotea piano suite called Dances of Marosszék,celebrating a section of Transylvania that hehad visited while growing up. He orches-trated that work in 1930, and seems to haveviewed Dances of Galánta as a sort of se-quel. He provided the following commentabout the piece, phrased rather curiously inthe third person:

Galánta is a small Hungarian market townknown to travelers between Vienna and Bu-dapest. The composer passed seven yearsof his childhood there. At that time there ex-isted a famous Gypsy band that has sincedisappeared. This was the first “orchestral”sonority that came to the ears of the child.The forebears of these Gypsies were al-ready known more than a hundred yearsago. About 1800, some books of Hungar-ian dances were published in Vienna, oneof which contained music “after several

Gypsies fromGalánta.” They have preservedthe old traditions. In order to keep it alive,the composer has taken his principalthemes from these old publications.

In the course of this work’s five move-ments, the listener is treated to various man-ifestations of the traditional Hungarianverbunkos style, in which slow figures alter-nate with fast ones and swagger gives wayto irresistible foot-stomping. The clarinet isgiven a particularly prominent part, reflectingthe role of the single-reed tárogató in Hun-garian folk music. This work, however, is nomere folk-song recital; instead, everything isfiltered through the composer’s colorfulbrand of brilliantly orchestrated modernism.

Instrumentation: two flutes (one doublingpiccolo), two oboes, two clarinets, two bas-soons, four horns, two trumpets, timpani,bells, triangle, snare drum, and strings.

An earlier version of this note appeared inthe programs of the UBS Verbier FestivalOrchestra and is used with permission.© James M. Keller

A Classicist Among Modernists

If Bartók preferred the percussive aspects of Hungarian and Balkanfolk music, then Kodály was drawn more strongly to its melodic andharmonic suggestions; both composers, however, were fascinatedby the repertoire’s metrical complexity. Kodály developed a recog-nizable style that, even in strictly instrumental pieces, emphasizedthe vocal contours of melodies and the influence of speech inflec-tion on the shaping of phrases. Many of his works exude a certainsense of introspection; a precise stylist, he stands as a classicistamong 20th-century ethno-Nationalists.

Bartók and Kodály in 1905

06-13 Kavakos:Layout 1 6/4/13 4:17 PM Page 31

Dances of Galánta (1933) By Zoltán Kodály (Kecskemét, Hungary, 1882 - Budapest, 1967) Zoltán Kodály made it his life’s work to study the folk music of his native Hungary and to write original compositions inspired by the folk tradition. Yet the Dances of Galánta are more than arrangements of folk dances heard during a field trip. They held deep personal meaning for the composer, for the town of Galánta (in Northern Hungary, now Slovakia) was the place where he had grown up, having moved there as a toddler with his family. In the preface to the printed score, Kodály wrote:

The author spent the most beautiful seven years of his childhood in Galánta. The town band, led by the fiddler Mihók, was famous. But it must have been even more famous a hundred years earlier. Several volumes of Hungarian dances were published in Vienna around the year 1800. One of them lists its source this way: “from several Gypsies in Galánta.”… May this modest composition serve to continue the old tradition.

During his research, Kodály found extensive evidence to show that the fame of those Gypsy musicians had indeed spread far beyond the boundaries of their hometown. As a child in Galánta, Kodály not only had ample occasion to hear Mihók’s band; he also learned many folksongs, sung to him by servants and schoolmates. (On another occasion in the 1930s, he would recall the voices of his “bare-footed companions from the Galánta public school.”) At the same time, Kodály was introduced to Western classical music while in Galánta. He took up the cello and, as his parents loved chamber music, he was soon able to participate in the musical evenings at home. Forty-odd years after the initial encounter with the Galánta dances, Kodály returned to them as a mature composer and a leading scholar of Hungarian musical traditions. He took the melodies from the early 19th-century Viennese editions mentioned in the preface; these editions had just been rediscovered by a musicologist named Ervin Major. Yet Kodály didn’t have to rely solely on the printed notes; he certainly had the sound of the old town band still in his ears when he scored the music. The style of these dances is known as verbunkos, from the German Werbung (recruitment). The Austrian army recruiters used to travel around the countryside with dancers and musicians in tow, whose performances were meant to entice young men to sign up. The verbunkos became the dominant Hungarian instrumental tradition of the 19th century. Kodály gave the various verbunkos melodies some exquisite musical coloring and arranged them in a masterful sequence with alternating moods and tempos. The pensive introduction anticipates the stately principal melody, played by the solo clarinet. Later on, this melody will return several times as a rondo theme. Two intervening episodes (one played by the flute, the other by the oboe) are faster in tempo and lighter in character. In the second half of the composition, the rondo form is cast aside and we hear a string of dance tunes that (with the exception of one slower theme) gradually get faster and faster. The climactic ending is delayed for a moment by the return of part of the opening melody, with a short clarinet cadenza added. The entire second half of the piece is dominated by a characteristic syncopated figure (short-long-short) which provides an ending which is as striking as it is simple.

Duration of complete work: 15:00 Last CSO performance of work: 1/11/2004 with Thomas Wilkins, conductor

Concerto in D minor for Two Pianos and Orchestra (1932) by Francis Poulenc (Paris, 1899 - Paris, 1963) Une Américaine à Paris (�An American Woman in Paris”)—reads the title of an interesting biography

© 2016 Triple A Learning – this analysis is sold as part of a BACCpack and is not to be distributed or re-published in any form without permission.

Dances de Galánta

Analysis

The structure of the piece

This is probably one of the most challenging aspects of the piece. Several suggestions have

been advanced in relation of its form. The score published by Universal Editions describes:

“A slow movement (bars 1-412) is followed without a break by a fast movement with

recapitulations of the principal theme and other elements from the slow movement (bars 413-

607). The slow movement is a rondo featuring three appearances of the principal theme and

three interpolated episodes. The theme of the fast movement is also heard three times, with

episodes in this case being variants from the slow movement.”1

Some aspects suggested in this structure are open to debate. The question arises about the

suggestion that the “fast” part begins at bar 413. One argument against this suggestion is that,

admitting the ‘slow and fast’ subdivision (quite acceptable taking into consideration the

verbunkos inspired lassú and friss), Kodály’s tempo indication at m. 238 is already quite fast

(quarter = 140). Also the claim that “The theme of the fast movement is also heard three times,

with episodes in this case being variants from the slow movement” does not seem to take in to

consideration that most of the melodies used in the fast section are ‘new’ melodies from the ‘raw

material’ rather than “variants from the slow movement” as the analysis in this section will

demonstrate.

Several scholars recognize the complicated task to describe a structure in this piece. Some of

them show frustration for the lack clear description of structure in existing books:

“If the form of the Dances of Marosszék was an unconventional version of a standard

rondo, the Dances of Galánta is even more enigmatic. Both Sárosi and Breuer describe

the form as a rondo with a finale (or coda in Breuer’s case) that contains six dance

melodies. Both authors comment that the length of the coda is actually longer than the

main rondo. Sárosi gives a clear starting point, stating that it begins in measure 236, but

he makes little effort to define the sections of the finale, aside from stating that the

performers “…go on playing the last dance of the dance cycle at length, stringing various

melodies together in a capricious, virtuoso manner, using variations and alterations.”2

1 Kodály, Zoltán. Tänze aus Galanta für Orchestra (1933). Universal Edition A. G. Wien, 1934. P. XIII.

2 Ong, Corinne K. A Historical Overview and Analysis of the Use of Hungarian Folk Music in Zoltán

Kodály’s Háry János Suite, Dances of Marosszék, and Dances of Galánta. Master Thesis. University of

Kansas. 2011. P. 81.

© 2016 Triple A Learning – this analysis is sold as part of a BACCpack and is not to be distributed or re-published in any form without permission.

The Structure in this Analysis

The present analysis suggests a hybrid form including elements from verbunkos and rondo in

the following way:

Dances de Galánta

Overall Structure

Section Subsection Beginning measure

Main Melodic Material from ‘Vienna Verbunkos Score’ (Raw Material)

Introduction 1 Theme A

Lassú Rondo-A 50 Theme B

Rondo-B 94 Theme C Rondo-A 153 Theme B Rondo-C 175 Theme D Rondo-A 231 Theme B

Friss Section 1 238 Themes E, F, and G

Section 2 336 Theme H Section 3 407 Theme I and J (first part) Section 4 445 Theme J (second part) Section 5 492 Themes E, F, and J

Coda Section 1 567 Theme B

Section 2 581 Variations of Theme J

Treatment of the ‘Raw Verbunkos Material’ by Kódaly

While the use of the verbunkos raw material is evident in Dances of Galánta, it is necessary to

clarify that Kódaly seldom uses these themes in their entirety. He rather presents them in a

fragmented way even when they appear for the first time in the piece. As it will be demonstrated

in the next section, Kódaly often splits the themes in two or three sections and, in their first

appearance, he often presents only the first part of the themes. It is only after several measures

or passages that the remaining sections are introduced. This ‘technique’ applies mostly to

themes starting in m. 175 (Theme D).

© 2016 Triple A Learning – this analysis is sold as part of a BACCpack and is not to be distributed or re-published in any form without permission.

Detailed Analysis

3 Ong, Corinne K. A Historical Overview and Analysis of the Use of Hungarian Folk Music in Zoltán Kodály’s Háry

János Suite, Dances of Marosszék, and Dances of Galánta. Master Thesis. University of Kansas. 2011. P. 70.

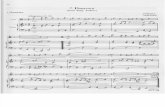

Bar Section Description 1 Introduction The piece opens with an exact transcription of Theme A (from the ‘Vienna’

verbunkos) in cellos. The double dotted rhythms are characteristic of the verbunkos.

6 The previous statement is responded with the entrance of higher strings and flute in imitations. Following the lassú style, rubato is present. A fermata at the end of this passage (between mm. 9 and 10) help to distinguish these two sections from the following sections. Some scholars see this passage as in A melodic minor3.

10 Similar to m. 1 (French horn transposed a perfect 4th above). 15 Similar to m. 6 (piccolo instead of flute). 19 With an indication of poco più mosso this section supports the rapid

alternation of portions of the two main motives (transposed) from the previous section. Theme A presented by:

• oboe/flute (m. 19)

• bassoon viola (m. 23)

• violin I/II (m. 27)

© 2016 Triple A Learning – this analysis is sold as part of a BACCpack and is not to be distributed or re-published in any form without permission.

34 Quasi cadenza in the clarinet (based on arpeggios related to motives in m.

6). The fermatas maintain the rubato aspect of this section. 37 A poco stringendo passage based in part of ascending and descending

arpeggios reminding figures in mm. 6-9. 45 Cadenza by the clarinet concludes the first section. Some scholars see in

the prominent presence of the clarinet (here and in m. 34) an attempt to imitate the tárogató, a single reed instrument used in Hungarian folk music.

50 Lassú Rondo A

Change of tempo and meter mark the beginning of section 2. Clarinet introduces another theme from the ‘Vienna’ verbunkos. Theme B is introduced with some changes in rhythm and pitch from the original. The following example shows two staffs: 1) on top the original verbunkos from the Vienna book and, 2) on the bottom, the fragment of Dances of Galánta starting at m. 50. In order to compare the melodic contour of both melodies, the ‘original’ verbunkos has been transposed to the same key and register than the passage from ‘Dances’. The passage from ‘Dances’ has been transformed into 2/4 (from original 4/4). The notes in red indicate existing differences between the two versions. For clarity, the example does not include articulation or expressive indications.

© 2016 Triple A Learning – this analysis is sold as part of a BACCpack and is not to be distributed or re-published in any form without permission.

66 New entrance of Theme B (flute, clarinets, and higher strings) with small

changes and transposed a P4 above. 82 Partial entrance of second part of Theme B (clarinets, bassoon I, viola,

cello). This passage is similar to m. 74. 94 Lassú

Rondo B

Change of tempo, meter and key signature open a new section. Pizzicato off-beats in higher strings (esztam) prepare new section.

97 Theme C is introduced by flute I (m. 97), joined by piccolo (m. 104) and continued by clarinets, violins and violas (m. 110). The following example shows two staffs: 1) on top the original verbunkos from the Vienna book and, 2) on the bottom, the fragment of Dances of Galánta starting at m. 97. In order to compare the melodic contour of both melodies, the ‘original’ verbunkos has been transposed to the same key and register than the passage from ‘Dances’. The notes in red indicate existing differences between the two versions. For clarity, the example does not include articulation or expressive indications.

© 2016 Triple A Learning – this analysis is sold as part of a BACCpack and is not to be distributed or re-published in any form without permission.

124 New presentation of Theme C split as follows:

• m. 124: piccolo, oboe I, clarinet II, bassoon I

• m. 130: flute I, piccolo, oboe II

• m. 136: clarinets, most strings

• m. 140: flute I, piccolo, oboe I The parallel motion of the different instruments offers an non-Western flavor (m. 124 and 130)

153 Lassú Rondo A

Climatic reappearance of Theme B (ff appassionato) and large instrumentation (woodwinds and higher strings). The following example shows two staffs: 1) on top the original verbunkos from the Vienna book and, 2) on the bottom, the fragment of Dances of Galánta starting at m. 153. In order to compare the melodic contour of both melodies, the ‘original’ verbunkos has been transposed to the same key and register than the passage from ‘Dances’. The passage from ‘Dances’ has been transformed into 2/4 (from original 4/4). The notes in red indicate existing differences between the two versions. For clarity, the example does not include articulation or expressive indications.

© 2016 Triple A Learning – this analysis is sold as part of a BACCpack and is not to be distributed or re-published in any form without permission.

175 Lassú

Rondo C

Kodály introduces Theme D (only its 1st part) in a way very close to the original verbunkos in terms of pitch and rhythm.

The following example shows two staffs: 1) on top the first part of the original verbunkos from the Vienna book and, 2) on the bottom, the fragment of Dances of Galánta starting at m. 175. The notes in red indicate existing differences between the two versions. For clarity, the example does not include articulation or expressive indications.

183 Repetition of the 1st part of Theme D in flute (transposed 8ve higher)

191 Second part of Theme D introduced by oboe I. The following example shows two staffs: 1) on top the first part of the

original verbunkos from the Vienna book and, 2) on the bottom, the

fragment of Dances of Galánta starting at m. 191.

© 2016 Triple A Learning – this analysis is sold as part of a BACCpack and is not to be distributed or re-published in any form without permission.

199 Repetition of the 2nd part of Theme D (piccolo).

207 Alternation of different sections extracted from Theme D as follows:

• m. 207: Flute 1, 2nd part of Theme D transposed a perfect 4th above.

• m. 211: Violins, last 4 measures of Theme D not transposed.

• m. 215: Flutes, beginning of 2nd part transposed half a step above.

• m. 215: Oboe I, figures extracted from 2nd part.

• m. 219: Woodwinds and violins, last 4 measures of Theme D (with a different ending at m. 222) not transposed.

These sections ‘interrupt each other in tempo and motivic material. 223 The ascending short motive of m. 222 seems to be the element creating

the eight-measure codetta (with stringendo) that concludes this section. The following example presents only the two violin parts. However, this motive appears in several voices. In the following example the motive is in red.

231 Lassú Rondo A

This section concludes with the climatic reappearance of the 1st part of Theme B. The tempo is again andante maestoso, a tempo that has been associated with the appearances of this theme at mm. 50 and 153. The following example shows two staffs: 1) on top the first appearance

© 2016 Triple A Learning – this analysis is sold as part of a BACCpack and is not to be distributed or re-published in any form without permission.

of Theme B in the dances and, 2) on the bottom, the fragment of Dances of Galánta starting at m. 231. In order to appreciate the melodic transformation the example does not include articulation or expressive indications, and the part of the clarinet at m. 50 has been transposed to C.

238 Friss

Section 1

Theme E is presented in the violins. The following example shows two staffs: 1) on top the first part of the original verbunkos from the Vienna book and, 2) on the bottom, the fragment of Dances of Galánta starting at m. 238. The notes in red indicate existing differences between the two versions.

254 Entrance of Theme E in violin I with doubling on violin II a sixth lower. At m. 260 flutes and clarinets have opening of Theme E (imitated by horn).

270 1st part of Theme F in flute and oboes. This section is repeated with some variation at m. 274 (violin I). The following example shows two staffs: 1) on top the first part of the

© 2016 Triple A Learning – this analysis is sold as part of a BACCpack and is not to be distributed or re-published in any form without permission.

original verbunkos from the Vienna book and, 2) on the bottom, the fragment of Dances of Galánta starting at m. 270. The notes in red indicate existing differences between the two versions. For clarity, the verbunkos example has been transposed to the key of “Dances”.

278 1st part of Theme E (flute I, oboes, clarinets, and violins). However, from

m. 284 the 3rd part of the same theme appears. The following example shows two staffs: 1) on top the first part of the original verbunkos from the Vienna book and, 2) on the bottom the fragment of Dances of Galánta starting at m. 278. The notes in red indicate existing differences between the two versions.

This third part of the theme repeats several times, each time an octave higher, to support the overall crescendo.

305 Theme G in piccolo and violins. The following example shows two staffs: 1) on top the first part of the original verbunkos from the Vienna book and, 2) on the bottom, the fragment of Dances of Galánta starting at m. 305.

At the same time, oboe I and clarinet II play sections of Theme F transposed from its original presentation.

313 Sections of Theme F are presented in a ‘stretto’ manner as follows:

• m. 313: violins

© 2016 Triple A Learning – this analysis is sold as part of a BACCpack and is not to be distributed or re-published in any form without permission.

• m. 317: clarinets and bassoons

• m. 319: flutes and oboes. Simultaneously, at m. 317, Theme E reappears in the violins. At m. 319 oboes and clarinets present theme F with French horn playing theme E on the beat.

324 A twelve-measure closing section begins with p subito / crescendo, syncopation, rising melodic contour, esztam, and an indication of “ritmo di 3 battute” (beat in 3) that means that the macro-measure is a 6/4.

336 Friss Section 2

A poco meno mosso section prepares the entrance of Theme H (only 1st part: clarinet I, m. 348). The following example shows two staffs: 1) on top the first part of the original verbunkos from the Vienna book and, 2) on the bottom, the fragment of Dances of Galánta starting at m. 348. The notes in red indicate existing differences between the two versions. For clarity, the verbunkos example has been written in ‘A’, as the clarinet is.

• M. 339 Trombone I and II with theme I (second part) in canon.

• M. 352 theme H is in the flute. 356 A new presentation of Theme H (in bassoon I and cello). This section is

accompanied by arpeggio figures that seem to emanate from the last measure of Theme H in m. 355.

364 The 2nd part of Theme H is introduced by violin I. The following example shows two staffs: 1) on top the first part of the original verbunkos from the Vienna book and, 2) on the bottom the fragment of Dances of Galánta starting at m. 364. The notes in red indicate existing differences between the two versions.

This section of Theme H is repeated an 8ve higher at m. 372 (violin and

© 2016 Triple A Learning – this analysis is sold as part of a BACCpack and is not to be distributed or re-published in any form without permission.

flute) while other instruments provide imitations of some of the motives of this theme.

379 The last measure of Theme H is repeated homophonically by several instruments and used as codetta for this section (diminuendo to poco sostenuto at m. 387).

393 This a tempo section functions as a bridge to the next section. The transition begins with the first motive of Theme H in m. 396 (piccolo). This figure is imitated by several instruments (bassoon I, m. 397; piccolo, m. 402; bassoon, m. 403).

407 Friss Section 3

Finally, the 1st part of Theme I appears in m. 407 (horn I). The following example shows two staffs: 1) on top the first part of the original verbunkos from the Vienna book and, 2) on the bottom the fragment of Dances of Galánta starting at m. 393. For clarity, the verbunkos example has been written in ‘F’, as French horn.

This 1st part of the theme is repeated by:

• piccolo and bassoon I at m. 409

• flute I, oboe I, and bassoon I at m. 417 423 The change of tempo (Allegro vivace) brings the 2nd part of Theme I in

canonic entrance between viola and violin II. However, only violin II plays the 2nd part of Theme I in its entirety. The following example shows two staffs: 1) on top the first part of the original verbunkos from the Vienna book and, 2) on the bottom, the fragment of Dances of Galánta starting at m. 423.

This presentation is followed by partial presentations or variations of Theme I (either 1st or 2nd part) such as:

• m. 432:flutes, violin II

• m. 435: violas

• m. 436: clarinets

• etc. 427 Concurrent with the presentation of 2nd part of Theme I (mm. 424-431)

Kodály introduces the 1st part of Theme J (flute and violin I, m. 427). The following example shows two staffs: 1) on top the first part of the original verbunkos from the Vienna book and, 2) on the bottom, the

© 2016 Triple A Learning – this analysis is sold as part of a BACCpack and is not to be distributed or re-published in any form without permission.

fragment of Dances of Galánta starting at m. 427. For clarity, the verbunkos example has been transposed a major 2nd above.

This is followed by transported imitations or variations of this fragment such as:

• m.431: clarinets

• m. 435: violin I

• m. 436: violin II At m. 442 flute/oboe present fragments of Theme H (1st part).

445 Friss Section 4

The 2nd part of Theme J is presented at m. 445 by violin I The following example shows two staffs: 1) on top the first part of the original verbunkos from the Vienna book and, 2) on the bottom, the fragment of Dances of Galánta starting at m. 445. The notes in red indicate existing differences between the two versions. For clarity of the example the original verbunkos has been transposed a major second above.

This is followed by transported imitations or variations of this fragment such as:

• m. 449: clarinet joins violin

• m. 453: flute, oboe, and 2nd violin join

• m.477: violins

• m. 491: flutes, violin I 492 Friss

Section 5

A variation of the 1st part of Theme E is presented by most of the instruments. During this passage (mm. 492-526) parts of Theme E will alternate with 1st part of Theme F :

• m. 492: Theme E

© 2016 Triple A Learning – this analysis is sold as part of a BACCpack and is not to be distributed or re-published in any form without permission.

• m. 508: Theme F • m. 512: Theme E • m. 516: Theme F • m. 520: Theme E

508 This passage offers the following similarities to the passage at m. 324: • p subito / crescendo

• syncopation

• rising melodic contour

• Presence of syncopated figures

• “ritmo di 3 battute” The differences are the scale passages found on higher instruments such as flute I, oboe I, clarinet I, and violins. These passages could be traced to Themes E and/or F.

545 While in this passage violins clearly present the 2nd part of Theme J, other voices (woodwinds) present motives that could emanate from Theme J or other themes.

567 Coda

A ‘general pause’ brings a change of tempo to Andante maestoso. This is the tempo that has been associated to Theme B (mm. 50, 153, 231). This is also de case at m. 569 where motives of Theme B reappear in flute, oboe and clarinet. The last of these presentations (m. 573) in clarinet evolves into a cadenza similar to that in m. 45 (where clarinet imitates the tárogató).

581 The melodic material could be associated to previous themes but mostly to Theme J.