Analisis Kelayakan Finansial Usahatani Singkong Gajah di ...

Gajah 10 Spring 1993.pdf - the Asian Elephant Specialist Group

Transcript of Gajah 10 Spring 1993.pdf - the Asian Elephant Specialist Group

Newsletter of the Asian Elephant Specialist Group @

NUMBER SPRING 1993

INTERNATIONAL UNIONFOR CONSERVATION OF NATURE

AND NATURAL RESOURCES

SPECIES SURVIVAL COMMISSION WWF World WideFor Nature

Produced with the assistance ofWorld Wide Fund for Nature

Fund

GAJAHNewsletter of the Asian Elephant Specialist GroupNumber 10 Spring 1993

WWF World Wide Fund .

For Nature

Editorc: Lyn de Alwis & Gharles Santiapillailnquiries:-DR CHARLES SANTIAPILLAIExecutive OfficerAsian Elephant Specialist Group1 10 Wattarantenne Road,

Kandy, Sri Lanka

The Newsletter is published and distributed with financial assistance form V\AffF-lnternational.

NEWSLETTER Advisory GroupMr. J.C. Daniel,

Prof. D.K. Lahiri-ChoudhuryDr. R. SukumarDr. Simon Stuart

The Asian Elephant Specialist Group Newsletter is published with the following aims:-- to highlight the plighr of the Asian Elephant- to promote the conservation of the Asian Elephant- to provide a forum for communication amongst all the members

Newsworthy articles are invited for consideration for publication and should be sent to DrCharles Santiapillai at 110 Wattarantenne Road, Kandy, Sri Lanka. All articles may bereprinted. Reprinted articles should give credit to the Newsletter. The editors would appreciatereceiving a copy of any article so used. The opinions expressed by the authors do notnecessarily reflect the policies of either \AANF or IUCN.

Cover : One of the many makhnas (tuskless bull elephants) in the Ruhuna National Park,Sri Lanka.

CONTENTS

Comment z Lyn de Alwis & Charles Santiapillai

Feature Articles

Community Ecology of the Asiatic Elephant.

by Joseph P. Dudley

Reconciling Elephant Conservation with Economic

Development in Sumatra .

by Charles Santiapillai & Widodo Sukohadi Ramono

Recent Elephant Conservation Efforts in Sri Lanka

by A. B. Fernando

Some observations on Elephants in the Buhuna National Park, Sri lanka.by H. l. E. Katugaha

Short Communications:

Making or Tagging Elephants for Individual ldentification.by Richard C. Lair

lnsuring against elephant depredationsin Sri Lanka

Elephants Under Threat in Laos

by Charles Santiapillai

Book Review:

The lllustrated Encyclopedia of Elephants. From theirOrigins and Evolution to their Ceremonial and WorkingRelationship with Man. Salamander Book, London. 19glReviewed by Charles Santiapillai

Diary:

Workshop on the Biology of Forest Elephants

International Seminar on the Conservation of the Asian Elephant

GA.IAII: tO, 1993

ut

0a

t1

19

32

33

26

10

34

39

40

COMMENT

It is a truism that, at any but the lowest density,large wild animals and human beings are fundamentallyincompatible. As the densities of both large mammalsand man increase, this incompatibility increases as well.Throughout Asia, increasing human popolation andincreasing agricultural land use havo substantiallyreduced the area once available to the elephants. Thesituation has reversed from one in which man lived in

small settlements in areas dominated by elephants toone in which the elephants find themselves confinedto small patches of habitat, surrounded by a man-dominated landscape. The elephants and other wildlifehave lost so much of their former habitat, that they are

often forced to invade the communities that havedisplaced them. This is the crux of the elephant-humanconflicts in Asia. Depredation by elephants has becomea way of life.

There is a relationship between tolerance of wildlifeand human population density. In countries where thehuman population densities are low, there is generally

an acceptance and tolerance of such large mammals as

the elephant. Religious sentiments too reinforce thisattitude to keep poaching, wanton killing and cruelty toanimals to a minimum. However, when the humanpopulation becomes too numerous and too sophisticated,this relationship progresses through'time f rom acceptanceto intolerance. \A/hen this happens, even religion ispowerless in preventing the slaughter of wildlife.

In Sri Lanka, despite a strong Buddhist culture a

number of wild elephants had been killed in the recentpast by irate farmers who had borne the brunt ofelephant depredations. In some instances, the killingswere carried out by poachers in order to supply tusksto a few carvers, who despite the international ban onivory, continue to produce pendants and other trinketsfrom elephant ivory for sale to the tourists who seemto have re-discovered Sri Lanka. In a desperate effortto resolve the humanclephant conflicts in Sri Lanka. a

consultant from abroad recommended the capture ofsome 500 wild elephants lor domestication and

subsequent sale through public auction! Such a

harebrained scheme, if implemented, would adverselyaffect the long-term survival of the elephants inthe u'ild.In most instances, much of the crop depredations are

the result of lone bulls wandering in search of oestrousfemales to mate. The capture and removal of suchanimals will seriously undermine reproduction and

recruitment in the wild. lt would also lead to a sigrrificantreduction in the genetic variation in the population.

Removal of chronic crop raiding elephants from an area

of high human population makes sense if it involves onlya .few animals. But to recommend the capture and

removal of almost 20 percent of the island's elephantpopulation for domestication and sale to the public willonly help accelerate the demise of the island's wild

G,4,IAII: 10, 1993

elephant population. Thereare no instant solutions to thecomplex problem of human-wildlife conflicts in Asia.Time, money and trained rrnnpower act in many casesas brakes on what can be done to resolve the problem.The root cause of elephent depredations throughout Asiais deforestation and conversion of forests to agriculture.Although human population pressure, land hunger and

a need for fuel wood have all helped to caussdeforestation, it has also been encouraged enormouslyby bad economics. Even the World Bank has realisedthat a tropical forest may be far more productive thanthe scrubland which often succeeds. But governmentsthroughout Asia.frequently assume that fragib forestscan easily be cleared and farmed. They also frequentlyignore the ecological costs of deforestation: soil erodes,rain fall diminishes, water supplies become less reliable,rivers silt up, dams get clogged. human-wildlife conflictsescalate and such extinctionprone species as theelephant and other large mammals often disappear.

It is now becoming increasingly clear that if we wantto enhance the long-term survival of the elephants inAsia, some sort of accommodation between man and

elephant must be reached. Man and elephant will haveto live together by mutual adjustment. Furthermore,management policies must be designed to persuadepeople to change their attitudes. from intolerance totolerance or from mere toleranca to acceptance. Howcan this be achievedT One way is through proper zoningof the conservation areas and their adjacrnt lands fortypes of use that integrate conservation needs withthose of adjacent human populations. Another possibilityis by improving the incentives for local communities toparticipate in the conservation of wildlife resources. Thecommunities that bear the brunt of elephant depredationsmust be properly compensated for their losses. Suchcompensation could be provided through sensibleinsurance schemes or from revenues from naturetourism. Unfortunately, in many Asian countries. the

-local communities receive little or no benefit from 'tourism, whereas the true beneficiaries of tourism are

the local tour operators and their international sponsors.Outdoor recreation is valued by a small segment of themore affluent section of the society while the poor

remain alienated or indifferent. The local communitiesmust participate fully in decisions affecting their land and

resources. International efforts to protect ond safeguardthe Asian elephant populations throughout their rangemust include projects and programmes that involve thecooperation and participation of the local communities.Finally, conservation educailon must be given highpriority. Conservation policies, however well-rooted theymay be in science, can succeed only if they are

intelligible to the people concerned.

by Lyn de Alwir & Charler Sanliapillai

3

)

COMMUNITY ECOLOGY OF THE ASIATIC ELEPHANTJOSEPH P. DUDTEY

DEPARTMENT OF WILDUFE AND RANGE SCIENCESSCHOOL OF FOREST BESOURCES AND CONSERVANON

UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDAGAINESVILLE, FLOBIDA 92611, tT S. A.

fn prehistoric times the Asiatic elephant (Elefiiasmaximus) occupied a large terrestrial generalistierbivoreniche within the alluvial plain, savanna, and gallery forestecosystems of southern Asia. Currently wild Asiaticelephant populations are largely restricted to relictlowland forest fragments and upland forest areas ofSoutheast Asia, whereas formerly this species occupieda much larger range ,and a greater variety of habitats.

Asiatic elephants were knorvn in historical times tohave lived throughout much of southern Asia from themontane regions of the Himalayas to the coastallowlands of Southeast Asia. Asiatic elephants rangedfrom the Tigris-Euphrates valley of Asia Minor in thewest across the Indian sub*ontinent to the Huang Heffellow River) yalley of China in the north and east; andsouth lhrough the Malay penninsula to the island ofSumatra. The modern population of Asiatic elephants onBorneo is thought to have been derived from introduceddomesticated stock. (Altevogt and Kurt, 1972; Olivier,1978bt.

The Asiatic elephant is able to utilize a wide varietyof habitats provided that basic requirements for water,shade, and forage can be met. Freezing temperaturesand dailyaccess to fresh water are major limiting factors.Savanna, forest-scrub, secondary forest, and grassland-forest mosaics are the preferred habitat types (Eisenberg,1980a). The availabilityof grasses (Graminae, Poaceaelis an important factor, since grasses typically constituteat least 507o of the Asian elephant's diet (Vancuylenberg,

.19771. Closed+anopy forests can thus support onlylimited elephant populations unless clearings or alluvialconidors are available to provide grasses for forage.Seasonal variations in the rvailability of water and foragemay result in regular migrations of 40 km or more, andformerly aggregations of elephants containing thousandsof individuals occurred in some areas as the result ofseasonal migrations to areas of exceptional resourceabundance.

The surylving Asiatic elephant populations are forthe most part small, isolated, and declining rapidly. Thealienation of habitat to agriculture, plantation forestry,wholesale clearcutting of forests, competition fromdomestic livestock, and direct human predation (for food.ivory. or crop protectionl are constant threatsto the fewremaining wild elephant populations. Until fairly recently

a

Feature Articles

the humanclephant relationship in Southeast Asia wasa relatively benevolent character with losses of alluvialplain habitats to stable agriculture balanced by increasesin the availability of suitable forest habitat as a resultof humaninduced fires, low.intensity selective logging,and traditional patterns of shifting cultivation.

The impact of explosive human population increasesin the past century and concurrent demands for greateragriculture and forestry production have steadily erodedthe limited remaining areas of wild elephant habitat.Most surviving wild populations of Asiatic elephants aresmall and isolated among relict forest fragments widelyscattered across humandominated la ndsc,ap6s, a situationwhich offers little hope for long-term survival (Soule,1980; Allendofi et a|,1986). The Asiatic elephant isnowextinct throughout most of its former range andexcluded from many preferred habitats (Olivier. l97Bb).This trend appears unlikely to change in the forseeablefuture, and the pressure on relict populations isincreasing steadily with the passage of time.

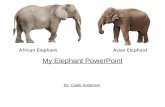

Elephants are the largest living terrestrial mammals.The Asiatic elephant is somewhat smaller than theAfrican bush elephant (Loxodonta africana africand andsimifar in size to the African forest elephant (L. a. eyclotis).MaturE Asiatic elephant bulls attain weights of 5400kg.and shoulder heights of 3.2 m. Females average aboutone-third smaller than males. Largetusks are found onlyin the male Asiatic elephant, and the proportion of tuskedand untusked males varies among populations. In SriLanka tusked males are rc(e (<10%), and thisphenomenon may be due to centuries of selectiveremoval of tuskers from the breeding population by man,either through killing for ivory or by capture fordomestication (Eisenberg, personal communication). Inthe nearby mainland populations of south India g0% ofmales ar6 tusked (Sukumar. 19861. The elongateproboscis or trunk functions effectively as a fifth limb,and enables the elephant to extend its feeding rangeto a height of five meters or rxlre vertically, enablingefficient use of scrub and low canopy forest habitati(Eisenberg and Mckay, 1974; Gzimek, 1g72: Shoshaniand Eisenberg, 1982).

GA.IAII:IO, 1993

Man has been an important predator of elephantssince at least the late Pleistocene. Only the largest ofthe great cats. tiger and lion, can be considered withman as a significant predator of elephants.

Formerly tigers were a major predator of youngelephants, and Williams (1950) estimated that tigerskilled about one fourth of all elephant calves during theirfirst few years of life. While healthy adult and sutsadultelephants are for the most part immune to predationby big cats, a lew instances of tigers killing adultelephants are known (Shoshani and Eisenberg, 1982).Elephants are hosts for various internal and externalparasites including various species of roundworms,flukes, lice, tickq bacteria, and protozoans (Benedict,

1936; Eltringham, 1982).

The Asiatic elephant typically assumes a role as theecologically dominant mammalian species within itshabitat (Eisenberg, 1981; McKay, 1973; Seidensticker,19841. Elephant foraging actlvities may have profoundimpact on the diversity, distribution, and abundance ofnumerous components of the biotic community (Janzen.

1983; lshwaran, 1983; Mueller-Dumbois, '1972; Lawsetal. 1975: Mulkey et al, 1984: Wing and Buss, 1970).Studies on the feeding habits of E. maximus maximusin Sri Lanka have assessed the impact of elephantforaging behavior on the physiognomy and speciescomposition of forest vegetation (lshwaran,'1983;Vancuylenberg, 1977: Muller-Dumbois, 19721. Foodpreferences in general are highest for open scrubspecies of plants and lowest for forest species. Amongwoody vegetation species consumed, early seral speciesare prefered over later seral or climax species (McKayand Eisenberg, 19741.

Although Asiatic elephant foraging behavior hassignificant effectson the plant communities within theirhabitats, major changes in habitat characteristics havenot been correlated with feeding activity by E. maximuspopulations. In contrast to the radical landscape-alteringimpacts attributed to African elephants floxodonta africana)in various East African ecosystems (Laws et al, 1975:Mulkey et al1984:Wing and Buss, 19701, theinfluenceof E. maximus maximus populations on their habitats hasbeen found to be of a mor€ subtle character. Amongstudy populations of the Asiatic elephant in Sri Lankathe principle effect of elephant activity has been tomaintain existing successional community characteristicswithout inducing malor changes in existing habitatstructure or species composition (lshwaran, 1983;Vancuyf enbe rg. 1 977 ; Mueller-Dumbois, 1 9721. However,this difference may be due in part to the lower densitiesof Asiatic elephant populations and not entirely todifferences in feeding habits (Mueller-Dombois, 19721.

Elephants are generalist herbivores which utilize a

broad range of herbaceous and woody vegetation, fruits,roots, tubes - virtually any form of plant material maybe consumed. Grasses are a prefered food source and

GAIAII:IO, 1993

comprise a high proportion of the diet when conditionspermit (McKay, 1971; Vancr.rylenberg, 19771. Bamboomay be an important food source in heavily forestedhabitats where the availability of other grasses is limited,and other monocots such as palms and rattans may beof importance in the diet in rain forest communities(Ollvier, 1978a; Blowet 1985). Forbs, shrubs, and treesare incorporated in the diet to varying degrees accordingto site and season. Forbs, seedlings, and smaller treesmay be consumed entirely, but leaf and/or bark may beselectively eaten in foraging on woody vegetation.

Feeding activity may be highly destructiw in certaininstances. Grasses are often ripped up and eaten root,culm, and leaf while trees may be pushed over or brokendown in order to gain access to fruit or leaves whichare out of reach (Mueller-Dombois. 1972; Kurt, 1974:Lekaguf and McNeely, 19771. In selective feeding onbark or leaves up to 80% of the biomass removed inforaging may be discarded (lshwaran, 1983; Lekagul andMcNeely, 19771. Seeds frequently pass unharmedthrough the digestive tract and may subsequentlygerminate or be eaten by other animals (McKay, 1973).

Elephants are hindgut fermenters with a faidy rapidgut transit time and relatively low digestiva efficiency(Benedict, 1936). Nonetheless, adequate nutrition can bemaintained on a relatively poor quality (low protien/highcellulose) diet provided sufficient quantities of forage areavailable (Janis, 1976; Eltringham, 1982). Elephants canutilize coarse and highly lignified mature grasses whichare unpalatable to other ungulates. Maturs elephantsconsume 150-200 kg per day of green vegetation(Lekagul and McNeely, 1977: Seidensticker, 1984;Vancuylenberg, 1977). Wild elephants may need tospend 70% to 80% of their waking time in foraging inorder to maintain an adequate nutritional plane (Eisenberg,

1981; McKay, ' 1973; Atevogt and Kurt 1972:Vancuyfenberg, 19771.

In Sri Lanka, elephants typically forage in smallgroups of one to ten individuals which feed for a fewdays in the vicinity of a particular water source and thenmove on. Feeding areas are shifted several times dailyand in Sri Lanka elephants feed on grasses in open areasduring the cooler morning and evening periods, andbrowse in shaded areas during the heat of the day(McKay, 1971). Although up to 7O% ol the plant speciesin a given habitat may be eaten, elephants tend to driftand spot-feed upon only a small percentage ofindividuals of any one species at a given site(Vancuyfenberg, 1977: Eisenberg and Lockhart, 1972:Mueller-Dombois, 1972; McKay, 19711.

Mortality of large trees due to browsing by theAsiatic elephant is very low, perhaps attributable in partto the limited distribution of elephants with large tusksamong the population as a whole. Browsing activityfocuses on woody plants inthe 2.0-32.0cm size class,and observations indicate that less than 9% of feedingon trees or shrubs involves the pushing over ot breakingdown of the individuals fed upon (lshwaran, 1983).

Mueller-Dombois (1972) has identified crown-distortion as the primary impact of Asiatic elephantbrowsing activity on woody vegetation. The physiognomyand growth patterns of trees and shrubs are altered asa result of injuries caused by elephants when browsingon bark, leaves, orfruits. Crowndistortion is characterizedby abnormal crown shapes and growth patterns. and thelong term effect is to create reductions in the rates andextent of canopy closure in browsed stands. Canopyspecies often show high levels of crown distortion,apparently, caused by elephant predation, and this mayaffect canopy regeneration in areas with high elephantdensities (Mueller-Dombois, 1972).

Elephant induced tree mortality also occurs outsideof a foraging context. Male elephants sometimes knockdown trees without any associated feeding activity,often within a localized area (Eisenberg and Lockhart,1972). While the low levelsof tree mortality associatedwith browsing by Asiatic elephants apparently has littledirecteffect on the species composition of forest stands,the selective browsing of early seral canopy speciestends to inhibit regeneration of shade-adapted climaxforest species by reducing canopy closure. Reducedcanopy closure benefits the elephant by increasing theavailability of prefered early seral vegetation forms,especially grasses.

Elephant feeding habits show extensive overlapswith those of other sympatric herbivores. Virtually allspecies of plants, browse and herbs, eaten by otherungulates are also consumed by elephants. In areas withhigh herbivore densities, elephants may compete withbovids, deer, swine. rhinoceros, porcupines, and haresfor available forage. Competition with domestic or ferallivestock for access to water and grazing is a significantprobfem in many areas (Altevogt and Kurt, 19721.Although the potential for exploitative competition cleadyexists, other factors tend to ameliorate the negativeimpact of elephant populations on various othersympatric herbivores.

The mobility and generally low populailon densitiesof Asiatic elephants tend to reduce the effects ofelephant competition for forage on most endemic wildherbivores, and behavioural facilitation phenomenaarising from elephant activity may provide benefits tonumerous other species. Athough the elephantcompetesdirectly with other herbivore species for access to someplant resources, elephants also graze on the tall, lignifiedstems of mature grasses which cannot be effectivelyutilized by most other ungulates (McKay and Eisenberg,1974: Vancuylenberg, 1977). This removal of maturegrass stems by elephants can stimulate new growth,increase primary productivity, and improve fie accessibilityof the underlying herbage to other herbivores(McNaughton, 1979). Young leaves discarded by elephantsduring browsing and bark feeding may be eaten by deeror other animals which otherwise would be unable toobtainaccess tothese resources (Lekagul and McNeely,19771.

6

Elephants dig deep holes in dry watercourses tocreate seeps when surface water is unavailable, andthese are used by other animals when the elephantsdepart (Eisenberg and Lockhart, 19721. Numerousanimals use elephant paths in traversing areas of denseundergrowth (McKay, 1971; Altevogt andKurt, 1972:Lekaguland McNeely, 19771, andthese paths may therebyfunction as corridors in promoting the movement ofspecies between habitat patches. The opening up ofdense understory and lower canory vegetation promotesgrowth of grasses and forbs favoured fu other ungulatesand various other herbivores. Elephant foraging activitiesthus can benefit various other mammalian species,especially grazing ungulates, by maintaining earliersuccessional plant communities and ecotone areas attheexpense of closed canopy forest species.

Elephant foraging activity can be beneficial tovarious species in other ways. Mynahs (Acridotherestristisl, cattle egrets (Bubulcus rbrsl and egrets lEgrettaspp.) feed on insects disturbed by elephants in feeding.and these birds may be allowed to perch unmolestedon the heads or backsof elephants (McKay, 1971).

The role of elephants in biomass transport andredistribution within ecosystems has been frequentlyoverlooked. In conjuntion with a food intake of some150k9/day, elephantsproduce about 80kg/day of dung(Vancuyfenberg,1977l. My own experience with captiveelephants indicates this latter figure may be somewhatconservative, and Benedict (1 936) records fecal depositionrate in a large captive female at up to 137 kg/day.Nonetheless, using Vancuylenberg's data for estimation,anelephant produces some 15 metric tons of fecalmaterial eech year. Two elephant herds in Sri Lankawere estimated by Vancuylenbers (1977) to deposit,respectively, 7507 kg and 9075 kg of dung daily. Asiatic '

elephant population densities vary widely amongdifferent habitats. and densities of 1.0&m2 (Eisenberg,1980a), O.27km2 (Olivier, 19781, 0.19/km2 (McKay, 19711have been reported. At a population density of 0.20rkm2,the elephant fecal deposition rate would be about 5000kg/km?!ear. At a density of '|.O/km'z (which is near themaximum record for Asiatic elephant populations),annual fecal deposition rates would be 30,000 kg/kmr/year. Elephant feeding and defecation thus contributesubstantially to the recycling and redistribution of plantbiomass within their habitats (Eisenberg, 1972:Vancuylenberg, 1977).

When undisturbed, elephants typically defecatewhile standing in a single spot. Defecation and urinationare frequently simultaneous. Excreta are oftenconcentrated in an area approximately one meter square.In captive Asiatic elephants a single defecation typicallyconsists of 6€ fecal boluses weighing from 0.5-1,5 kgeach (on a diet of grass hay with supplemental grainand occasional fresh fruit and vegetables). A singleurination may result in the localized deposition of lenliters of nutrient-rich fluid to the soil (Benedict,1936l.Elephant excreta form localized and patchily distributed

C,AIAII:|O, 1993

nutrient sources which are utilized by numerousmembers of the biotic community (Eisenberg, 1972:McKay, 1971; Anderson and Coe, 19741'

Elephant excreta provide rich nutrient sources fora wide range of both plant and animal species. Therelative inefficiency. of the elephant digestive tractensures that the overall nutrient content of the dungremains higher than that of most other ungulates(Benedict. 1936; Shoshani and Eisenberg, 1982).

Elephant excreta provide a rich organic nutrient sourcefor soil bacteria and various other detritivores, which in

turn make these resources available for plant use(Anderson and Coe, 1974).

Seeds and tough-skinned fruits eaten by elephantsfrequently pass through the digestive tract intact. Birdsand small mammals are known to seek out dung piles

to feed on undigested seeds, fruit, or plant material and

various coprophilic invertebrates (Eisenberg. 1972:McKay, 1971; Rood, 1975; Vancuylenberg,l9TT). Fungifrequently grow in elephant dung, and undigested seedsmay germinate if not subsequently eaten by otheranimals (Eisenberg, 1972: McKay, 19711. The importanceof the Asiatic elephant in the seed dispersal of tropicalforest plants is as yet poorly documented. Given thehigh vagility and extraordinary consumption potentialinherent to this species, Asiatic elephants should provide

excellent vehicles for redistributing seeds of many plantspecies employing animal seed dispersal strategiesUanzen. 1983).

Elephant dung is a prime food source for numerousinvertebrates such as termites, scarabid beetles. worms,and flies. Termites feed on elephant dung and refusefrom elephant foraging activities. New mound and

colonies of some termite species are frequently initiatedunder piles of elephant dung (Eisenberg and Lockhart.1972). Termites are extremly important membersof thebiotic community, and the role of termites in the nutrientcycles of tropical ecosystems is frequently underestimated(Eisenberg. 1972).

Termite mounds serye to concentrate resources'byforming high nutrient patches in nutrient-poor tropicalsoils (Golley, 1983; Salick et al, 19831. The indirecteffects of termite mound building activities includeincreased levels of soil turnover and soil aeration, aspectsof great importance to maintaining oprimal growingconditionslor plants in tropical soils. The elephant dung/termite relationship has far reaching implications whenviewed in terms of a keystone symbiosis in thebiogeochemical nutrient cycles of tropical forest andsavanna ecosystems (Eisenberg, personal communicationl

Elephants also contribute to soil turnover in othercontexts. ln feeding on short prostrate grasses elephantsscrape the ground with the nails of the forefeet,'scalping' the grasses and parts of the roots from theupper layer of the soil. When using this feeding methodelephants kick up large quantities of soil, and erosion

GAIAII:|O,7993

may occur subsequently on these sites (Kurq 1974:

Vancuylenberg, 1977). The mudiathing or dust-bathing

activities of elephants creEts soil turnovsr and enable

the transport of large quantides of soil between differenthabitat patches (Vancuylenberg, 19771.

Elephants and other herbivores have high sodiumrequirements and in many areas mineral licks areof great

importance to resident elephant populations(Seidensticker, 1984; Ldkagul and McNeely. 1977)' Saltsoils or friable rock are dug out with tusks or the toenailsof the forefeet and then collected with the trunk and

ingested. The unused remainder is frequently utilized by

other herbivore species (Lekagul and McNeely, 1977).

The distribution of mineral licks may harre marked effectson the mo/ement patterns of elephant populations in

some areas and can be manipulated as a means forregulating movements in some wild elephant populations(Seidensticker. 19841.

Elephants need daily access to drinking water' Thirtygallons (120 liters) of water or more rnay be ingestedover a short period of time by a large adult. Water isimportant not only for drinking and bathing but also as

a means for avoiding heat stress. Access to water and

shade are important for thermoregulation at highambient temperatures. The elephant's low surface area

to mass ratio predispose it to problems of overheatingat high temperatules or in direct sunlight (Eisenberg,

19831. African elephants apparently have greater

tolerance for exposure to direct sunlight at highertemperatures than do'Asiatic elephants (Seidensticker,

19841. The author has observed instances of sunbumon the skin of the forehead in captive Asiatic elephantsin temperate North America (Maryland, U.S,A.l followingextended exposur€ todirect sunlight in,the spring aftera several month period of limited outdoor activity duringwinter.

Elephants posse$i both physiological and behavioralmechanism for avoiding problems due to overheating.Physiological adaptations to heat stress include a

convection cooling mechanism associated with highvascularization of the large, flattened sat pinnae.

Increased blood flow in the ears when coupled withfanning movements permits rapid heat dissipation fromthe surface of the ears (Shoshaniand Eisenberg. 1982;Eisenberg, 1983). The wrinkling and folding of the skin

seryes to increase skin surface area and promote heatdissipation,. The sparse pelage permits frea air movementover the skin sur{ace, while tending to trap soil and

vegetation thrown onto the body to form an insulatingcover against sun and insects. Behavioral adaptations forreducing heat stress include bathing with'water or mudand seeking shade during the heat of the day. Whenaccess to drinking water is not limiting, water consumedearly in the day may be retained in the stomach, and

then hours later regurgitated into the throat drawn intothe trunk, and then sprayed on the body to promoteheat loss through evaporation from the skin.

In their daily and seasonal movements elephantswill cross large areas, and home rang€s of 60 km2 ormore have been reported for elephant herds in Sri Lanka(McKay, 1973). Olivier (1978a) has estimated the homerange for an elephant herd in Malaysian rain forest atover 166 kmz. Seasonal movements of 30{0 km areknown from both south lndia and Sri Lanka (Eisenbergand Lockhart. 19721. The Asiatic elephant frequentlyshifts activities between alluvial grasslands, savanna-scrub, grassy ecotone areas and forest interiors in dai[foraging activities (McKay, 1971; Vancuylenberg, .|977);

feeding bouts are interspersed with visits to drinking,bathing, and wallowing sites.

Considering the capacity of the elephant for bothmineral and biomass redistribution between differentactivity sites in the home range, the elephant may besaid to function as a mobile link between the various plantcommunities within its environment. While elephants arenever the numerically dominant mammal species in theirhabitats, they are nonetheless frequently an ecologicaldominant in terms of biomass and materials cyclingparameters (McKay, 1973; Seidensticker, 1984). Bothdirectly and indirectly elephants contribute substantiallyto the cycling of mineral and organic components of theecosystems they inhabit.

Elephant foraging activities affect the configurationand species composition of plant communities withintheir habitats. Elephants impose landscap+.level impactsupon their habitats by maintaining earlier seral stages ofplant succession, with far-reaching effectsupon the plantand animal species therein. The physical modificationsimposed by elephants upon their environments such aspathways, water seeps, and opening up of understoryvegetation may tend to offset competition for foragebetween elephants and other sympatric ungulatespecies. Herbivores favouring ecotone and forest-grassland mosaic habitats can benefit from the presenceof elephants, whose activities tend to maintain thesecommunities at the expense of closed-canopy foresthabitats. Species prefering closedcanopy habitats, suchas arboreal primates, may bo adversely affected forthesesama reasons (Eisenberg, 1980b).

The actual role of the Asiatic elephant in structuringits environment remains but poorly understood.Although various studies have provided regional insightsregarding general trends and the potential mechanismsinvolved, as yet only a few more obvious aspects ofthis phenomenon have been investigaled. The natureand scope of the known ecological interaction betweenthe Asiatic elephant and its environment as reviewetlabove probably represent a small fraction of thefunctional interrelationships actually present.

Unfortunately, the keystone function of the Asiaticelephant has already, been lost to ecosystemsthroughout most of the species original range. The Asiaticelephant may well become extinct before comprehensiveecological studies can assess the full significance of the

8

elephant's role in the tropical forest ecosystems ofSoutheast Asia. Theseforests form thE final refuge forthis once ubiquitous species of southern Aisa, andprovide the sole remaining opportunity for determiningthe ecological interaction of the Asiatic elephant in itsnative habitat. These forest systems lhemselves are ingreat jeopardy due to human exploitation, and given thepresent situation, as the forest goes so must theelephant.

The potential exists for maintaining viable populationof Asiatic elephants within multiple-use forest reseryes(Olivier, 1978c; Dudley, ms). Elephant populations canrespond favourably tocertain forms of habitat perturbation

The Elephant Range concept envisions a multiple-use forest reserve comprised of one or more inviolatecore preserve areas enveloped by one or moreconcentric designated-use areas (buffer-zonesl, managedin such a way as to enable the maintenance of wildelephant populations in concert with development of

es.eldofin

endemic plant and animal species, and would functionin protecting core preserye areas from the detrimentalimpacts of the surrounding humandominated landscape(and vic+versa).

The Elephant Range concept represents I potentialframework for the establishment of forest reserves

inexorable human pressures on the forest communitieswhich are the last refuge of the Asiatic elephant.

Lheraturc ched:

tic elephant. pp.

. 12, Grzimek'st al., eds.). Van

Anderson, J.M., and M.J. Coe. 1g74. Decompositiono{ elephant dung in an arid tropical environment.Oecologia I 4: 1 'l 1-1 25.

GAIAH:|O, 1993

Benedict. F.G.1936. Thephysioloy of the elephant.Carnegielnstitution. Washington, D.C.302 pp.

Blower. J. 1985. Project 1777 -Elephants in Burma.Pages 279-285 in WWF Monthy Repor! December1985. Gland, Switzerland.

Eisenberg, J.F. 1972. The elephant life at the top.Pp. 19'f -208 in: Iha maruels of aninnl behavior lT. B.Allen, ed.l. National Geographic Society, Washington,D.C.

Eisenberg, J.F. 1980a. Ecology and behavior of theAsian elephant. Elephant Suppl., 1:36€6.

Eisenberg, J.F. 1980b. The density and biomass oftropicaf mammals. Pages 35-55 in Conseruation Biology:An evolutionaryaclogical perspective (M.E. Soule andB.A. Wilcox, eds.). Sinauer Assoc., Sunderland,Massachusetts.

Eisenberg, J.F. 1981 . The Mammalian radiations: ananalysis of trends in evolution, adaptation and behavior.Univ. of Chicago Press, Chicago. 610pp.

Eisenberg, J. F. 1983. Higher vertebrate adaptationsto tropicaf rain forests. Pp. 267-278 in Tropical ForestEcosystems (F. Golley, ed.l Ecosytems of the World,Vol. l4A.

Eisenberg, J.F. and G.M. McKay,1974. Comparisonof ungulate adaptations in new and old world tropicalforests. Pps. 585-602 in: Ihe behavior of ungulates andits relation to management, vol. ll (V. Geist and F.Wafther, eds.l.IUCN New Series 24:1-94O.

Eisenberg, J. F., and M. Lockhart" 1972. Anecological reconnaissance of Wlpattu National Park,Ceyfon. Smithsonian Contrib. Zool. 101:1-118.

Eftringham, S. K. 1982. Elephants. Blanford Press.Dorset, U. K. 262 pp.

Golley, F.B. 1983. Decomposition. Pp. 157-165 inTropical Rain Forest Ecosystems (F. Golley, ed.).Ecosystems of the World, Vol. 14A.

Grizmek, B. 1972. The African elephant. Pp. SOG512 in Chapter 14 (Elephantsl Vol. 12, Grzimek's AnimalLife Encyclopedia lB. Gzimek et al.. ed.l. Van NostrandReinhold, New York.

Harris, L. D. 1984. The fragmented forest. Univ. ofChicago Press. Chicago. 211 pp.

lshwaran, N. 1983. Elephants and woody-plantrefationships in Gal Oya, Sri Lanka. Biol. Consent. 26:25$270.

Janis. C. 1976. The evolutionary strategy of theEquidae and the origins of rumen and caecal digestion.EvoL 30(4):757-774.

GAIAII:IO. 199{t

Jaruen, H. D. 1S3. Food webs. Pp. 167-182 inTropical Bain Forest Ecosystems (F. Golley, ed.l.Ecosystems of the World, Vql. 14A.

Kurt, F. 1974. Remarks on the socialstructure andecologyof the Ceylon elephant in the Yala National PArk.Pps. 618€34 in lhe bhavior of urgulates and itsrelation to management vol.ll (v. Geist and F.Walther,eds.). fUCN New Series 24:1-940.

Laws, R. M., l. S. C. Parker, end R. C. B. Johnstone.1975. Elephants and their habitats. Oxford, ClerendonPress. 376 pp.

Lekagul, 8., and JA. McNeely. 1577. Elephants. Pp.636€41 in Manntals of Thailand. Kurusapha LadpraoPress. Bangkok.

MAB. 1979. Biosphere Reserves, Proc. of U. S"/U.S.S.R. symposium, Moscow, 1976. USDAGen. Tech.Rep. PNW€2.

McKay, G. W. 1971. Behavior and ecology of theAisatic elephant in southeastern Ceylon. Unpubl. Pd. D.Thesis, Univ. Maryland, College Park 327 pp.

McKay, G. W. 1973. Behavior and ecology of theAisatic elephant in southcastern Ceylon. SmithsinianContrib. Zool. 125:1 -1 13.

McKay, G. M. and J.F. Eisenberg. 1974. Movementpatterns and habitat utilization of ungulates in Ceylon.Pp.7O8-721 in: lhe behavior of ungulates and itsrelationto management (V. Geist and F. WaltheC eds.l LUCNNew Series 24:1-94O.

McNaughton, S. J. 1979. Grassland-herbivoredynarnics. Pp. 4e81 in Serengeti: dynamics of anecosystem (/4. R. E. Sinclair, ed.l. Univ. Chicago Press,Chicago. 389 pp.

' McNeely, J. A. 1980. Conservation of endangeredfarge mammals in Sumatra. Elephant I (41:33-38.

Mueller-Dombois, D. 1972. Crown distortion andelephant distribution in the wood-vegetations ofRuhunu National Park, Caylon. Ecology 32: 20f}l226.

Mulkey, S. S., A. P. Smith, and T. P. Young. 1984.Predation by elephants on Senecio kenyaderdron(Compositae) in the alpine zone of Mount Kenya.Biotropica, 1 6(31: 246-248.

Olivier, R. C. D. 1978a. On the ecology of the Asianelephant. Unpubl. Ph. D. Thesis, Univ. Cambridge,England. 454pp.

Ollvier, R. C. D. 1978b. Status and distribution of theAsian efephant. Ory4 14:379424.

Oliviet R.C. D. 1978c. Conservation of the AsianEfephant. Environmental Conseruation 5(2):1 56.

Rood, J. P. 1975 Population dynamics and foodhabits of the banded mongoose. E.Afr. Wildi. J. 13:89-111.

Salick, J., R. Herrera, and C. Jordan.'1983.Termitaria: nutrient patchiness in nutrient deficient rain

forests. Biotropica. 15(1): 1-7.

Seidensticker, J. 1984. Managing elephantdepredation in agricultural and forestry proiacts. WorldBank Technical Paper. Washington, D. C.

Shoshani, J. and J. F. Eisenberg. 1982. Elephasmaximus. Amer. Soc. Mammal. Mammalian Species182:1€.

Soule, M. E. 1980. Thresholds for survival:maintaining fitness and evolutionary potentia:. Pages151-169 in: Conservation Biology: An evolutionary-ecological perspective (M. E. Soule and B. A. \Mlcoleds.). Sinauer Assoc., Sunderland, Massachusetts.

Sukumar, R. 1986. The elephant in south lndia. Pp.23-32 in \AM/F Monthly Report. January 1986. Gland,Switzerland.

Vancuylenberg, B. W. B. 1977. Feeding behaviourof the Asiatic elephant in south-east Sri knka in relationto conservation. Biol. Conseru., 12:3-54.

Williams, J. H. 1950. Elephant 8/l Rupert Hart-Davis, London 321 pp.

Wing, L.D., and l.O. Buss. 1970. Elephants andforests. Wildl. Monogr. 19:1-92.

ELEPHANTS UNDER THREAT IN LAOS

CHARLES SANTIAPIL]AI

Laos was known as Muong Lan Xang Hom Khaoorthe'Land of the Million Elephants and the WhiteParasol' in the fourteenth century when it was founded. lt was first called 'Laos' by the French when theyannexed it totheir Far Eastern Empire inthe last century. Today Laos, with a total land area of about 236,800km2 is estimated to have not more than 4,000 elephants in the wild and about 850 animals in captivity.One of the legacies of the Indo-China war is the ready availability of guns and firearms. Today, it is estimatedthat there are nearly 1.2 guns per mile in this strategic, land-locked, innocuous, little Buddhist country of4 million people (Martin, 1992). Between 1990 and 1992, about 50 elephants had been killed by poachers

for their tusks, skin and meat (Vientiane Mai, '1992). These killings occurred mostly in the Nam Theun area

in the Khammouane province in central Laos. The killings of elephants were attributed to some poachers

who crossed into Laos from neighbouring Vietnam (Vientiane, Mai, 1992). (Some of thd poachers who werecaught red-handed by the Laotian authorities turned out to be Vietnamese nationalsl). At over 400,000 ha

Nakai Plataer-r/Nam Theun is by far the largest proposed protected area in Laos with Vietnam as its easternboundary (Salter etaL, 1991). This area has a known resident population of elephants, and is inhabited largelyby Lao Loum and Lao Theung ethnic groups who practise slash and burn agriculture. Price of unworkedraw ivory is about US$ 50 per kg. lvory carvers in Vientiane and Luang Prabang using hand tools carveout small souvenirs such as Buddha pendants from ivory for sale to tourists (Martin, 19921. Most of thetourists are form Thailand and the problem will only be exacerbated if the proposed plan to build a bridge(with Australian aidl across the Mekong river, linking Thailand to Laos goes aheadl Laos needs internationalassistance (mainly funds and equipment) to improve the protection of almost all the proposed conseryationareas. Arresting the illegal trade in wildlife across its border with China, Burma, Thailand, Cambodia andVietnam will not be easy. ltis recommended that Laos becomes a party to CITES (Convention on InternationalTrade in Endangered Species). A British historian once casually remarked that 'Laos is like the Cheshire cat.One minute it's thqre, the next it has disappeared; and sometimeg while you're watching, it begins to fade,until there's nothing left but the smile - the Lao smile'(Field, 1965). lf poachers are allowed to ply theirtrade with impunity in Laos. then only the White Parasol will be left!

Bef: -Fiefd, M. 1965. The Prevailing Wind. Anchor Press, UK.-Martin, E.B. 1992. Wildlife Trade Booms in Laos. Wildlife Conseruation MarcVApril 1992.pp.8-9-Salter, R.8., Phanthavong, B. & Venevongphet. 1991. Planning and Development of a ProtectedArea System in Lao PDR: Status report to Mid-1991. Vientiane, Laos.

-Vientiane Mai., 5 August 1992. Laos.

10 GAIAII:IO. 1993

Reconciling Elephant Conservationwith Economic DeveloPment

in Sumatraby

Charler SantiaPillaiDept. of Zootogy, University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka

and

Widodo Sukohadi RemonoDirectorate of Forest Protection & Nature Cons€rvstion

tPHPAl, Jakarta, lndonesia.

1.0 Introduction

The Sumatran elephant (Elephas maximussumatranus) is the smallest of the three subspecies ofthe Asian elephant. lts numbers are estimated to be

anything between 2,800 and 4.800 (Blouch & Haryanto1984; Blouch & Simbolon 19851. Once widely distributedthroughout the eight prwinces of Sumatra, the animalhas almost disappeared from two provinces and is underthreat in the rest of the island from a host ofdevelopment programmes such as logging, human re-

settlement, ostablishment of large-scale plantation

estates, oil exploration, mining, irrigation and agriculture.

The conversion of primary forest into agricultural

holdings has been one of the causes of conservationproblems in Sumatra and the elephant has been amongthe large mammals most seriously affected by it.Development programmes have led to the annual

elimination of tens of thousands of hectares of elephanthabitat.

As their traditional migratory routes are blocked,

habitats fragmented. the elephants are becomingincreasingly confined to patches of forests that are

surrounded by cultivated land. As Laws (19811 points

out in the situation in East Africa, the situation inSumatra too is reversing gradually 'from one in whichhuman islands existed in a sea of elephants, to a sea

of people with elephant islands'. These conditions have

led to a dramatic increase in the scale of elephantdepredations in Sumatra. In some cases the success ofthe development programmes has been threatened ss

a result of which, there has been a change in attitude

.by the planners in recognizing the need to take into'consideration the ecological requirements of theelephant during the planning stage of any developmentprogramrhe. ln return, the Directorate of Forest

Protection and Nature Conservation (PHPAI which is

primarily responsible . for the conservation of elephantmust match this recognition by the planners withrealistic proposals to especies without leadingpaper is an attempt towith economic development in Sumatra.

GA,IAII: 10, 1993

2.O Gonrervatlon of ElePhant.

The human population of Indonesia cunentlyestimated to be 170 million and concentrated in Java

and Bali is growing at an annual rate of 2.1%, with nocontrolling mechanism in sight, and with a forecastwhich must be at best optimistic, of ultimately stabilizingat 400 million. In an effort to relieve the populationpressure on the already over-crowded island of Java, theGovernment of Indonesia is currently resettling thesurplus population on the so called 'Outer lslands' ofSumatra, Sulawesi, Kalimantan and lrian Jaya. Such

elephant in Sumatra. Hence PHPApolicy to ensure the long-term suin Sumatra by aiming to keeP theand human settlements as far apart as possible'

Given that our obiectives is to ensure the longtermsurvival of the elephant in Sumatra, we must adoPt Istrategy that can achieve this objective. Parker (1984)

recommended the protection of as many individuals as

possible in as wide a range of habitats as is practical.

This implies the fact that not all the elephants in Sumatra

can be actively protected. Before such a strategy can

be adopted, the PHPA must have clear information on

the following:-

1. An approximate idea of the total number ofelephants in Sumatra'

2. The number and size of discrete populations.

3. How such populations are distributed in space.

4. How many of these populations do in factinhabit protected areas, and so can be activelyprotected.

5. What should be done with the populations thatoccur outside the protected areasT

6. What is the total extent of the protected areasin Sumatra.

7. How many of these areas are in fact large

enough to hold viable elephant populations?

11

8. What can be done to enhance the survivalprospects of the elephants inhabiting smallareas?

9. What land-use practices can be accommodatedalong the periphery of the protected areas,without leading to unacceptable levels inelephant-human conflicts?

10. What is expected from other GovernmentDepartments. whose development programmeshave been responsible in the pas( for at leastpart of the current human-elephant problems

in Sumatra?

2.1 Number of Elephanto in Sumatre

On the basis of the surveys carried out by Blouch& Haryanto (1984) and Blouch & Simboton figgbl.between 2,800 and 4,800+ elephants are estimated tobe present in Sumatra today, distributed mostly in sixof the eight provinces (Table 11.

Table 1. The minimum and maximum number ofelephants in Sumatra

Source: Blouch & Haryanto fi9841;Blouch & Simbolon fi9851.

2.2 Number and cize of discrete populations

The surveys of Blouch & Haryanto 0g84) andBlouch & Simbolon (1985) have identified at least 44discrete elephant populations (Fig. l) whose size rangesfrom less than 50 to 400 (Table 2). The largestpopulations with up to 400 elephants are found in Riauand Aceh provinces, which are important areas foreconomic development and so have been identified withchronic elephant depredations in the past. Some of theelephant populations in the heavily populated Lampungprovince are very small, consisting at times less thanten animals, and so have no long term viability.

Table 2. The number and size of the discrete elephantpopulations in Sumatra in 1985

provrnce

l. Gunung Sulah' Lampung <SO2. Gunung Tanggang' Lampung <SO3. Gunung Betung' Lampung <S04. Way Kambas , Lampung IOO-2OO5. Way terusan Lampung SG1OO6. North Barisan Selatan Lampung/tsengkulu SGIOO7. South Barisan Selatan Lampung >lOOL Gunung Raya Lampung SGI0O9. Gunung Rindingan Lampung SG1OO

10. Block 42 Lampung <5()11. Block 46 Lampung SGIOO12. Block 44 Lampung SGI(X)13. Block 45 (Mesuji) Lgmpung >lOO14. Tunggal Buta South Sumarra <5015. Subanjeriji South Sumatra <5016. Air Semangus South Sumatra SG1OO17. Padang Sugihan S<luth Sumatra >lOO18. Sungai Pasir South Sumatra <S019. Bentayan South Sumatra SGIOO20. Air Medak South Sumatra >lO021. Air Kepas South Sumatra/Jambi >lOO22. Intan Hepta Jambi SOIOO23. Mendahara Ulu Jambl SGIOO24. Suban Jambi SGIOO25. Gunung Sumbing Jambi >1OO26. Batang Tebo Jambi SGIOO27. Sungai lpuh Bengkulu >lOO28. Bukit Hitam Bengkulu <SO29. Torgamba Riau/North Sumatra IOO-2OO30. Tanjung Medan Riau >SO31. North Central Riau Riau 2OO-3OO32. Koto Panjang Riau SG1OO33. Lipat Kain Riau 5OIOO34. Langgam Riau >5O35. South Central Riau Riau IOO36. Southern Riau Riau 3OO4OO37. Buantan Riau >5038. Siak Kecil Biau IOO-20039. Lower Rokkan Riau SGIOO40. Sinkinjang West Sumatm >5041. Singkil Aceh <SO42. Western Gunung Leuser Aceh ' SGIOOz|i|. Western Aceh Aceh 2OO-3OOzl4. Eastern Aceh Aceh 3OO.40O

( * extinct by 1990)

2.3 Distdbution of elephant populationr

Province Minimum

l. Aceh 600 8502. North Sumatra a few a few3. Riau 1,100 1,7004. West Sumatra a few a few5. Jambi 2AO 5006. Bengkula 100 2@7. South Sumatra 250 6508. Lampung 550 9OO

Total 2,800+ 4,800+

12 GA.IAII: 10, 1993

IN

ETEPHANT DISTRIBUTION

:l0 200km

inD

Fig. l. Distribution of Elephant Populations in Sumatra. Indonesia

1993

inadequate to accommodate all the populations in Riau.The situation in Lampung too is serious in that theanimals are scattered in a mandominated environment.The Barisan range of mountains that run along the spineof Sumatra support elephans but at much lowerdensities than the lowland forests.

2.4 Statur of tfie populatiom

The populations that inhabit the Barisan chain ofmountains in Sumatra must be protectd come whatmay as it would mean rpso facto lhe protection of thewatersheds. on which depends the entire island'sagricultural prosperity. However, this habitat (largelyprimary montane fores0 is unlikely to support elephantsat high densities. The total number that is likely to occuralong the Barisan Mountain range is anything between<9fl) and >1250 ffable 3).

Table 3. The number of elephants that are likely tooccur along the Barisan Chain of Mountains

Province Number

Table 4. Lowlard areas with the best potential forelephant conservation.

province areas (km2l

1. Way Kambas (GRl

2. Padang Sugihan (GRl

3. Lebong Hitam (PDF)

4. Subanjeriji (HR)

5. Seberida (PNR)

6. Peranap (PHRI

7. Siak Kecil (PGRI

8. Air Sawan (PGR)

9. Bukit Kembang BukitBaling-Baling

10. Jantho (with proposedextention)

Lampung 1,235Sumatra Selatan 750Sumatra Selatan 3,000South Sumatra 650Riau 1,200Riau 1,200Riau 1,000Riau 1,400

Riau 1,460

Aceh 1,880

Total 13,775

43.

42.

40.

28.

27.

26.

25.14.

9.

8.

7.

6.

Total <90G>1250

Source: Blouch & Haryanto (19841;

Blouch & Simbolon fl9g5).

In contrast to the montane areas. the lowland foresthabitates can maintain relatively higher elephant densitieson account of the high productivity. Ten areas in thelowlands offer the best hopes for the long-term survivalof elephants in Sumatra (Table 4).

Note: GR = Game Reserve; PDF = Production Forest;HR = Hunting Reserve; PNR = Proposed NatureReserve; PGR = Proposed Geme Reserve

Having established the lowland areas which offerthe best returns for elephant conservation efforts inSumatra. it is necessary to estimate, even as a roughapproximation, just how many elephants can beprotected within these areas? In suitable South Asianhabitats. crude density of elephants can range from 0..|to 1 .04m2 (Eisenberg 1981; Eisenberg & Seidensticker1976). In way Kambas, the average crude density ofelephants was found to be 0.14/tm2 (Santiapillai &Suprahman 1986). Assuming that the Way Kambasrepresents a secondary habitat that is typical of loggedout areas throughout the lowland in Sumatra, we coulduse this density value to estimate the number ofelephants that can be maintained in thE ten conservationareas. lt appears that a total of 1.900 is ebout all thatcan be accommodated in the ten conseruation areas atan average crude density of 0.14ftm2. Elephants can infact live at higher densities in secondary forests, but itwould be prudent to aim at maintaining a number wellbelow the carrying capacity of the areas.

But to translate this idea into reality would requirestrong action on the part of the PHPA to implementcertain vital recomrnendations:-

al. The conservation areas in Riau (eg: Seberida,Peranap, Siak Kecil, Air Sawan and Bukit KembangBukit Baling-Balingl should be given legal status (Apresent they are designated simply as 'prposed. andtherefore amount to little more than 'paper parks..)

b). These areas must be surveyed and properlydemarcated and separated preferably from humansettlements by suitable buffer zones.

Western Aceh Aceh

Western Gg. Leuser Aceh

Sinkinjang

Bukit HitamSungai lpuhBatang Tebo

Gunung Sumbing

Tunggal Buta

Gg. Rindinggan

Gunung Raya

South Barisan

North Barisan

West Sumatra

Bengkulu

Bengkulu

Jambi

Jambi

South Sumatra

Lampung

Lampung

Lampung

Lampung/Bengkulu

20G300

50-100

<50

<50

>100

50-100

>100

<50

50-r00

50-100

>100

60-100

14 GAJAH: 70, 1993

c). The proposed nature reserve Jantho (80 km'zl

in Aceh is inadequate as an elephant reserye.

However it could be much enlarged by incorporating

the surrounding 1,200 kmz block of protection

forest and the 600 km2 block of protection forest(Blouch & Simbolon '1985). The n€w reserve would

then have a total areas of 1,880 km2 and thus would

be adequate to maintain a viable elephantpopulation.

d). The Padang Sugihan Game Reserve is only

750 kmz but it supports about 240 elephants, giving

a crude density of O.3Zkmz (Nash & Nash 1985;

Nash 1987), which is one of the highest elephant

densities known in South-East Asia' The Padang

Sugihan elephants are about the maximum lhereserve can support. Already there have been

reports that some of the elephants have raided

crops in the adioining transmigration settlements.The problem is further compounded by the fact that

forest fires within the reserve have also driven some

animals oul leading to more conflicts with the

human settlers nearby. The elephants are in turnthreatened by harrassment and habitat degradation(Nash & Nash 1985; Nash 1987) within the reserve.

lllegal logging takes place despite the fact it is a

protected area. Loggers operate with impunity

within the reserve, cutting trees well below the

officially permitted diameter of 50 cm. In one

sample study of 450 logs that were felled illicitly

in the reserve, the average diameter was 33 cm,and some as small as 19 cm (Nash & Nash 1985;

Nash 1987).

Given the high elephant density observed in Padang

Sugihan reserve. it would be a fail safe measure

if this reserue could be linked with the larger(3,000 km'?l Lebong Hitam production forest to itseast. Such a move would greatly increase the area

for elephants from 750 km2 to 3,750 kmz and willrelieve the current pressures on the Padang Sugihan

reserve as well.

But there are currently disturbing reports of forest

fires even within the Lebong Hitam production

forest that have destroyed up to 10,000 ha of peat

swamp forestl Unless strong measures are taken

now to prevent the recurrence of forest fires, even

such an extensive area as Lebong Hitam would be

useless as a refuge for the surplus elephants fromthe Padang Sugihan Game Reserve.

So, with the best of efforts and will, it might iustbe possible to protect between 2,800 and 3,000elephants in Sumatra, one third of which inhabit the

Barisan mountain range, while two thirds occur in the

lowlands.

GA.IAII: 10, 1993

2.5 Elephantr outride protected arear

A decision must be made as to what should be done

with the eareas. Thewith thesubstantialannual home range of a population, then the area is bestmanaged as a multiple-use forest where elephants can

cocxGt with man and might even benefit from 'limited

human use of forested uplands, including selectivelogging for local consumption, traditional hunting,

UamUoo extraction and slash and burn agriculture'Managed E

by Olivier (

le economicso ought to

a try.

lf a population of elephants is causing unacceptable

levels of depredations, then a decision must be made

if the animals have to translocated to another reserve

or captured for domestication and training. The PHPA

have staff who are well experienced in both operations.

They have successfully driven whole herds of elephants

in 1982 and 1984 in Southern Sumatra and Lampungprovinces, away from problem areas. lf the number ofelephants that are causing the problem is small (less

than ten animalsl. then it would be more economicalto capture them using chemical immobilization for eitherrelease into another reserve or for domestication and

training.

In areas where elephants have become a problem

as a direct result of economic development (eg:

establishment of oil palm. rubber, sugar cane plantations),

the onus of establishing elephant barriers (eg: electricfence, ditch etc.) must be on the development agency

and not onthe PHPA. At present all elephant problems,

irrespective of their source of origin, are brought to thePHPA's'doorstep'to be resolved. Given the low budgeton which the PHPA oPerates, it would be grossly unfairto expect the PHPA alone to solve all the elephantproblems.

2.6 Protected areas in Sumatra

With a total area ol 47.7 million ha, Sumatra is thesecond largest island in the Indonesian archipelago.

64.3% of the land area is officially designated as forestland (Anon 19841. The primary forest cover amounts to42% (UNDP/FAO 19821. Protected areas (i. e: NationalParks, Nature Reserves. Game Reserves, RecreationParks, Hunting Reserues and Protection Forestsl account

tor 17.2% of the totalland area' As far as the elephantconseryation is concerned, there are 28 areas in Sumatrawhose total area is 48,448 km2 (Santiapillai 19871. But507o of the areas are still in the 'proposed' categoryand so do not have the full legal protection theydeserve. However not all of them represent prime

ntatrx)us.elephantand they

15

2.7 Ateas with potentially viable elephant populations

There are 13 areas in Sumatra(actual and proposedlwhich are over 1,000 kmz in extent and so might beadequate to accommodate viable populations. Howwer,size of a reserve alone is no guarantee for the viabilityof an elephant population. What is important is todetermine the productivity of the area. Small areas canin fact support high densities of elephants in comparisonto large areas. A good example is the Padang SugihanGame Reserve which despite its small size (750 kmr)supports a much higher elephant density than the largestconservation area in Sumatra, the Kerinci-Seblat NationalPark ('14,846 km,).

2.8 Small areas

lf resources are limiting, small areas are poor betsfor long term conservation programmes. However, if itis indeed possible, every effort must be made to linksmall reserves with a nearby large reserve by forestcorridors. For such corridors to be really effective, theyshould be broad (at least a minimum of 5 km widel.and established along the banks of the river.

2.9 Compatible land-use practices

ldeally, all protected areas where elephants occur,should be established as far away as possible fromhuman settlements. lf this is not possible. then asuitable buffer zone should be established in betweenthe reserve and the human settlements. Elephantsrespond to edges, the transition zone betwsen forestand grasslands in a positive way (Seidensticker .|984).

Much of the elephant depredations in Sumatra is dueto the establishament of crop lands by the side of thereserve, thereby creating a diversity of habitats for theelephant. The patch of land that lies between humansettlements and elephant reserve should have 'zeroappeal ' to the elephants tO deter them from leaving theforest. This could be achieved by maintaining heavilygrazed areas along the periphery of the reserye,establishing plantations that are not preferred byelephants (eg: Eucalyptusl, or livestock husbandryinstead of cash crop plantations.

2.10 (hher Govemment Department assistance

The elephant problem must be looked upon as lhecollective responsibility of a number of Gov€rnmenlSectors that include Transmigration, Forestry 0oggind.plantations (oil palm, rubber, coconut. sugar cane etc.),Swidden agriculture, Mining, and power (hydroclectricand oil explorations) etc. Transmigration has beenidentified as an agent of forest desruction and much ofthe blame for the previous appalling failures oftransmigration schemes is due to the scant attention theplanners paid to site selection. A careful assessment ofeach forest block set aside for transmigration should bemada before it is cut. Despitethe ambitious. wellmeaning efforts of the Government, the transmigrationprogramme cannot possibly solve the demographic

16

problems of Indonesia when human population growthin Java alone adds 2 million a year. The targel forresettlement during 1984-1989 was 800,OOO families

arable land is used, it would require an additional $10million ha of land every five years, which must comefrom the forests.

The lropical rhigh proportion ofOn an average,200 rn3/ha of commercial sizes trees (GOl/llED 1995).In Sumatra, timber pgrowth timber fromvaluable dipterocarpattain the 60-70 cm

The Department of Forestry has laid down strictlimits to the exploitation of commercial timber species.The regulations stipulate that a minimum diameter of50 cm dbh and a cutting cycle of 35 years, leaving morethan 25 trees per ha of commercial species of aUn ZO

cut trees well beSelective logging ito 20 trees/ha whthe residual stand (

profligate waste of timber at the point of extraction.Loggers often extract lower number but exploit largerareas. The rate of overall timber explclitation far exceedsany attempts of reforestation and rehabilitation. As faras the elephants are concerned, they do not have anyescape routes to mole from a disturbed area to another

1985) offers a practicalis to maintain unloggedrses to link a concession

area with coridors of mature forest.

An ingenious way to maintaining areas of olderforests as wildife habitats within a logging concessionis to cut it in a checkerboard pattren (Shelton l9gSl.It is worth quoting in full: 'In a forest reserve managedon a SO-year rotation, which is faidy typical in Malafsiatoday. a block amounting to one fiftieth of thc rcservewould be logged each year. lf alternate blocks wcre leftunlogged until the second 25 yaers, there worJd alwaysbe at least 25 blocks of 25 to 49 yearold logged forestdistributed evenly throughout the reserve. Ttrese blockswould be adjacent to more recently logged blocks, whichwould thus have a nearby refuge and source of seedsand animal colonizers'. Such a system provides the bestopportunity for the management and conservatjon ofelephant outside the protected areas in Sumatra.

GA.IAII: 10, 1993

The need to control the currsnt rates of deforestationin Sumatra cannot be overstated. Logging operations perse are not responsible for large scale conservation offorests. These actions however expose the forest byproviding access to many people along the loggingroads, to the interior (Ross 1984). Roads in a normallogging operation in the high forests of Sarawakrepresent 4Vo of the total area logged (Hong 1987).

The department of Forestry must explore thepossibility of using trained elephants in timber extractionwithin production forests, as is the case in Thailand andBurma. The Elephant Training Centres in Sumatra cannothope to provide trained elephants to replace modernmachinery but could assist in some way the extractionof timber from say, swampy areas where no machinerycan function economically.

Soil erosion is perhaps the most seriousenvironmental impact of logging (Hong '1987). The useof trained elephants in timber extraction withinproduction forests can greatly reduce the negativeimpact of logging.

Plantation estates such as oil palm, rubber, sugarcane, coconut etc. have reaped enormous profits in thepast but have not responded substantially to mitigatingthe current spate of elephant-human conflicts in areaswhere their activities have displaced the elephants.Proper environmental impact analysis must precede anynew establishrnent of oil palm or other plantations. Theoil palm is a much prefurred food item of the elephantand so in the dbsence of effective elephant barriers,enorrrpus elephant damage to oil palm trees will beinevitable. Appropriate electric fencing in PeninsularMalaysia could reduce elephant damage by more than95% (Rdtnam 1984). Electric fencing providps the mostcost effuctive way of reducing elephant depredationunder conditions prevaihrg in humid tropics (Blair & Noor19811.

Shifting cultivation is often accused of causing muchforest destruction. Howarer, much of the damage to theforests is caused by the so called 'Shifted cultivators'rather than by traditional slash and burn cultivators. AsRoss (1984lpoints out, shifting cultivation in its classicalform is the only self sustainable system of agriculturein the tropical rainforest. lt becomes destructive onlywhen thcir numbers exceed the carrying capacity of theforest. Compared to the amount of forest loggedcommercially, the primary forest opened by swiddenfarmers in Sarawak is only a small fraction (Hong 1987).

3.0 Comlurion

Elephant problems in Sumatra can never becornpletely eradicated. They can however be reducedsubstantially if much thought is given to the elephantin the phnning stage of many of the island'sdevelcpment programrnes. The PHPA alone cannot dealeffectively with the elephant depredations. lt would needthe active support and generous financial assistance

GAIAH: 10, 1993

from both Governmental Departments and lnternationalOrganizations. International philanthropy to date has paid

more attention to helping with extraction of timber ratherthan reforestation and rehabilitation of degrarded areas.

The conservation ol elephanG in the face of growingeconomic development and increased human populationgrowth calls for a provincial approach. Each prwinceshould establish a Task Force to deal with the elephantproblemg in that province on a respond-to+risis basis.Each Elephant Task Force (ETFI should include a

veterinarian trained in the use of cap+hur gun totranquilize problem elephants if they need to becaptured and translocated elsewhere.

The provincial ETFs should be under the control ofa Director of Elephant Conservation whose Departmentwould be responsible for the control. management andconseryation of elephants in Sumatra.

The elephant Training Centres should providetrained elephants for use in forestry. wildlife and tourism.Trained elephants should be seen as an asset toeconomic development. Incentives must be given toindividuals or companies that use trained elephants inhauling logs to using heauy machinery. Trained elephantsperformed a number of useful jobs during the Dutchcolonial period; they ranged from hauling artillery duringthe war to hauling telegraph posts during peace.Capturing ' problem elephants' end training them foruseful service to man seems to be more humane andmeaningful than shooting them as pests. The ElephantTraining Centres in Sumatra should incorporateprogrammes to start breeding elephants in captivity.Elephants are slow breeders no doubt, but that shouldnot prevent the PHPA in making a start in this direction.lf elephants are to be trained for use in forestryoperations, then they should be self-sustainable.Otherwise, there is a hidden danger that these trainingcentres would simply become the raison d'etre for morecaptures from the wild.

The PHPA should base its policies on soundecological research. This can only come about ifincreasing number of its staff are trained in wildlifemanagement, and such trained personnel are in fact'based in the field to address the problems and providethe appropriate solution. Unless and until this happens.wildlife conseryation in Sumatra would be nothingmore than an art of the possible.

4.0 Reference

Anon, 1984. Statistic Kehutanana Indonesia. 1982/1983Departemen Kehutanan, Jakarta.

Blair, A. S. & Noor, N. M. 1981. Conflict between theMalaysian Elephant and agriculture. In:Conseruation lnputs from Life Sciences. Ed. M.Nordin, A. Latiff, M. C. Mahani & S. C. Tan.Proc. Symp. Conservation Inputs from LifeSciences. Univ. Kebangsaan, Malaysia.

17

Blouch, R. A. & Haryantq 1984. Elephants in SouthemSumatra. IUCM(VINF Report No. 3., Project3033, Bogor

Blouch, R. A. & Simbolon, K.1985. Elephants in NorthSumatra. IUCNMWF Report No. 9., Project303, Bogor.

Eisenberg, J. F & Seidensticker, J. 1976. Ungulates insouthern Asia: a consideration of biomassestimates for selected habitats. Biol. Conseru.,10: 293-308

GOI/I I E D (Government of I ndonesidlnternational Institutefor Environment and Development) 1985. Areview of policies affecting the sustainabledevelopment of forest lands in lndonesia. Vol.lll. Background paper. Jakarta.

Hong, E. 1987. Natives of Sarawak Survival in Borneo'sVanishing Forest. lnstitute Masyarakat, Malaysia.259 PP.

Kartawinata, K., Adisoemarto, S., Riswan, A. & Vayda,A. P. 1981 . The lmpact of man on a TropicalForest in Indonesia. Anbio., 10 (2€l; 11$119

Laws, E. M. 1981. Experiences in the study of largemammals. In: Dynamics of Large MammalPopulations. Eds. Charles W. Fowler & Tim D.Smith. John Wiley & Sons. N. Y.

McNeely, J. A. 1978. Management of elephants inSoutheast Asia In: Wildlife Management inSoutheast Asr'a. Eds. J. A. McNeely, D. S. Rabor& E. Sumardja. Biotrop Special pub. No. 6.Bogor.

Nash, S. V. & Nash, A. 1985. The status and ecologyof the Sumatran elephant (Elephas ffExmussumtranus) in the Padang-Sugihan WildlifeReserve, South Sumatra.\|WF/IUCN 3133 FinalRepoft, Bogor.

Nash, A. D. 1987. The Elephantsof Padang Sugihan. In:The Conservation and Management ofEndangered Plants and Animals. Eds. CharlesSantiapillai& Kenneth R. Ashby. Biotrop SpecialPublication No. 30, Bogor.

Olivier, R. C. D. 1978. On the Ecology of the AsianElephant. Unpublished Ph. D Thesis, Universityof Cambridge. UK

Parker, l. C. S. 1984. Conservation of African Elephant.fn: 7he Status and Consenration of Africa'selephants and rhinos. Eds. D. H. M. Cumming& P. Jackson,. IUCN Gland.

Ratnam, L. 1984. An exercise in elephant management.ln: Wildlife Ecology in South East Asia. Biotrop,Special Publication No. 21. Bogor.

Ross, M. S. 1984. Forestry in tand Use Policy forIndonesia. D. Phil Thesis, University of Oxford,UK.

Santiapillai, C. & Suprahman, H. 1986. The Ecology ofthe Elephant (Elephas ,naxmus L.) in the WayKambas Game Reserve, Sumatra, I/WF/IUCN3133 Final Repoft, Bogor.

Santiapillai. C. '1987. Action Plan for Sumatran ElephantConservation. IUCN/SSC Asian ElephantSpecialist Group.\AM/F lndonesia Programme,Bogor.

Seidensticker, J. 1984. managing Elephant Depredationin Agricultural and Forestry Projects, A WorldBank Technical Paper. Wshington DC.

18 GAIAII: 10, 1993

REGENT ELEPHANT CONSERVATION EFFORTS INSRI LANKA

A Tragic StorybY A. B. Fernando

Retired Agsigtant Direetor lEtephent Cons€rYationlMembe of the Specier Survival Commission

and Asian Elephant Specialist Group-IUCN

Elephas maximus was once present in all the foresttracts, both in the central hill region as well as in thelowland parts of Sri Lanka. During the British occupation

of the country, elephants got progressively eliminatedfrom the wet and fertile regions mainly due to large scale

forest clearance, at first for cultivation of coffee and later

for tea. and uncontrolled shooting. Since gaining

independence in 1948, despite the authorities taking

some meaningful steps to give special protection to theelephant, the situation has not improved to any

appreciable degree. The total elephant population in Sri

Lanka today is estimated to be about 2,500 elephants.They are found scattered in disiointed ranges in the

north, north central. north western, east and south

eastern parts of the country. This drastic decline in theelephant ranges is basically due to habitat loss through:

(a) major irrigation - settlement schemes embracing

river valley basins;(b) cultivation - both legal and illegal encroachment;(c) change in forest composition by silvicultural

practices, and(d) loss of habitat through man-made construction'

In unfamiliar surroundings, the movement and

behaviour of elephants change drastically. Such elephants

are compelled either to wanderaimlessly for a few years

until they find a new route back to their old haunts, or

to remain confined to the new areas. Man-made barriers,

habitat discontinuity and deterioration can lead to a group

becoming isolated from the original population and linallyending up in an unexpected area, In either situation, the

result is increased frequency of human-elephantinteraction.

It is common knowledge that the Asian Elephant

has drastically declined in numbers in almost all the

countries it is still found during the past two hundred

years, and today the total population is estimated to be

not more than 56,0@ elephants in the whole of Asia'

The problems connected with the preservation of the

elephant are common to allthese countries and in thatcontext an Action Plan for the preservation of the Asian

Elephant was prepared in 1990 and was commended to

the respective Gdvernments by the Asian Elephant

Specialist Group 6ESGI. The chapter on the Sri Lankan

eiephant in the Action Plan gives a fair and

comprehensive assessment of the present status of the

C,AIAII: lO, 1993

Sri Lankan elephant, and with over 3 decades of

experience as a field wo*er in the Department ofWitatite Conservation, I may venture to say that th€recommendations madE there in are sound and practical

and form a scientific basis for guiding and dwelopingthe future elephant conservation plans and programmes.

It is in this context that I am making an attempt in thispaper to evaluate and assess the ongoing elephant

conservation efforts since 1990, by the Sri Lankan

authorities vis-a-vis the recommendations made by theAESG in its Asian Elephant Action Plan.

It has been long accepted in Sri Lanka that allcally

"rfi:end.

though funds and manpo/\rer requirements provided to

the department were minimal. During lhe past two or

three years, however, sufficient funds have beenprovided.

The Smithosonian Elephant Survey activities carried

out between 1966 and 1972 and the short term studiescarried out by the local Universities over the years, on

the biology and ecology of the elephant, have

contributed in no small measure to help and guide the

department to plan and develop practical elephant

management strategies.

One of the main recommendations made in the

Action Plan is the necessity to undertake a long-term

seriously. The authorities howaner, have done away withthe separate elephant conservation unit which existed

from 1980 and which had overall responsibility for

Elephant conservation activities, as well as the elephantcontrol units that functioned fairly effectively by

responding promptly, among other things, to the

complainis of farmers. Today, that responsibility has

devolved on the 5 Regional Assistant Directors, whose

decisions and recommendations are undoubtedlyinfluenced by the regional interests and requirements,rather than those of the country as a whole.