FROZEN IN THE HEADLIGHTS: MEDIA OWNERSHIP …determine issues of ownership of Australian media on a...

Transcript of FROZEN IN THE HEADLIGHTS: MEDIA OWNERSHIP …determine issues of ownership of Australian media on a...

FROZEN IN THE HEADLIGHTS:MEDIA OWNERSHIP AND POLICY UNDER THE HOWARD GOVERNMENT

"Where a particular publisher has access to a

large proportion of the audience, any

policymaker would be foolhardy not to take

care before making policies which could

damage that company's business prospects."

Alley Steele

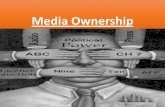

Making policy for the media industry is a tricky business. Governments rely on the media to disseminate news on public affairs. The media relies on governments, as one of their most reliable and accessible forms of information. There is always the risk of capture, that the media could evolve into a mere mouthpiece for the government, or that the government could become overly influenced by media proprietors flexing their muscle. Although these extremes may exist in other countries, no-one could argue that either institution has captured the other in Australia. Rather, the reality is infinitely more complex - a world where each link in the chain of democracy doesn’t always function as intended or expected; where government policies implemented for one purpose actually end up serving a completely different purpose; where certain groups hold more influence over policy, not because they are the majority (as we would expect in a democracy), but for other reasons entirely. Australia’s mix of highly concentrated media ownership, protection of incumbent companies in the face of new technology and the possibility of new competition, and bipartisan democracy has resulted in a sort of policy paralysis for the Howard government.

In some policy areas, Howard’s stubborn, middle-right of the road political strategy has, as would be expected from a conservative government, preserved the status quo more than engendered any groundbreaking policy issues, illustrated most perfectly in his attitude to the republic issue: “what we’ve got works [for me], why change it?”: and by his obstinate refusal to adhere to the current tide of support for aboriginal reconciliation by saying sorry’. The same cannot be said of Howard’s intentions for the media industry. One of the government’s 1996 election platforms was to hold a public inquiry into media cross-ownership laws and there were plans to investigate the creation of a fourth TV channel, and reform the ABC. What Howard has discovered, however, is that it is far simpler to criticise media policy from the opposition side of parliament, than actually to implement policy as a government.

The media is perceived by governments as a threat to their hold on power. Media campaigns can make or break governments. Where a particular publisher has access to a large proportion of the audience, any policymaker would be foolhardy not to take care before making policies which could damage that company’s business prospects. That said, the exact effects of the media on people’s opinions are at best indeterminate, so it is not the role of the media as opinion-setter which governments fear, but the role of the media as a catalyst to political events which alter the balance of public opinion. Investigative journalism, combined with the broader defence to defamation of qualified privilege1, confers a power on the media to alter the course of political events which affect public opinion- as opposed to influencing public opinion itself.

12(1) Polemic 26

Source: Reuters News Picture Service. Photo by David Gray 24/02/2000

Australia’s television and print industries are highly concentrated, as is radio to a lesser extent. Most capital cities in Australia are serviced by only one daily metro newspaper: Melbourne and Sydney are fortunate enough to have a choice of two. Murdochs News Ltd owns the only daily paper in Adelaide and Brisbane, and competes with Murdochs national paper, The Australian. Significantly, in terms of circulation, News Ltd owns 66% of Australian capital city metro circulation; and Fairfax, 21%. Television is similarly concentrated, with the three commercial channels networked via satellite. Restrictions on cross-media ownership2 mean that an owner of a radio or TV station cannot have an interest exceeding 15% (“control”) of the shareholding in a newspaper. Similarly, the owner of a newspaper cannot own more than 15% of a radio or TV station. Kerry Packer, who owns the Nine Network, also has a 15% holding in Fairfax. Murdoch has, at various stages, held 15% of channels 10 and 7.

Any government which wants to stay in power would clearly be reckless to formulate media policy without being conscious of the ramifications to the incumbent media players. In a market dominated by so few players, whose audience reach is remarkably high, it is risky to cross either one. And John Howard knows it. Soon after coming to power in 1996, he and Communications Minister, Richard Alston, announced a review of the cross-media rules, with a view to dismantling them. They believed that the rules would become obsolete - the advent of new technology would render them ineffective. In 1996 Howard had twin goals for media policy: to have as many owners as possible, and to have as many Australian owners as possible. The reform was to be reinforced with a public interest’ test inserted into the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth), to ensure diversity, giving the Treasurer the authority to determine issues of ownership of Australian media on a case-by-case basis.

The status of the cross-media review was intended to be public, encompassing various interest groups, the media companies themselves and academics, among

"Any government which wants to stay in power would clearly be reckless to formulate media policy without being conscious of the ramifications to the incumbent media players."

12(1) Polemic 27

others. Soon after the election, it was clear that the review was to be scaled back to an in-house review. Conducted in 1996-7, the review was regarded by some as ineffectual.3 After such strong convictions, the government eventually found that it couldn’t enact policy in the media industry without risking injuring one incumbent or the other- at the time, the government’s push to dismantle the cross-ownership laws was seen as opening the door to Kerry Packer’s PBL for a future bid on the Fairfax newspaper business (It is worth noting that Packer has a massive stake in the Australian magazine industry, however magazines are not included in the cross-ownership rules).

The government denied that it was ‘doing a deal’ with Packer - although when Jamie Packer introduced Treasurer Peter Costello in early 2000 as “my friend, the very, very good Treasurer Peter Costello”, questions were raised as to whether this was actually so. Irrespective of whether in fact a deal was done, this comment raises a number of issues as regards media policymaking. The first, is that when making policy for an industry dominated by a few personalities, virtually any change in policy will advantage one or perhaps two, and disadvantage another. Second, this same environment fosters close (perhaps too close?) relations between media proprietors and governments. The final point of interest is that media companies are all too happy to play on these relations in order to further their business goals, at the same time pressuring governments to prevaricate about every policy move made in the fear that it could ignite the wrath of one or other of the media proprietors.

The media ownership issue was put in the ‘too hard’ category, two years passed and the Productivity Commission handed down its final report on Broadcasting.4 The Productivity Commission recommended an increase in competition in broadcasting by issuing a fourth TV licence - something for which Australia has always, incidentally, had the capacity, but has never implemented. The Productivity Commission also queried the benefit of prohibiting the allocation of any new TV licences until 2007,5 a move clearly protective of the status quo

and incumbent interests, with little regard for quality of service for customers.

All governmental enthusiasm for media ownership reform having been eliminated, advances in technology, instead of ideological or reformist zeal, set the agenda for media policy, as has often been the case in Australia’s media history. In 1998, the government legislated to guide new (‘groundbreaking’) digital technology into the market.6 The Digital Conversion Act mandated High Definition Television (HDTV) over Standard Definition (SDTV) as the preferred format for digital television broadcasts. This was followed by legislation preventing datacasters from broadcasting material in SDTV datacasting channels which would encroach on the ‘territory’ of the incumbent broadcasters, heavily restricting broadcasts of drama, current affairs programs, sporting programs and events, music programs, infotainment and lifestyle programs, comedy programs, documentaries and reality. Mandating HDTV was a perplexing choice in a few ways.

"Jamie Packer introduced Treasurer

Peter Costello in early 2000 as 'my friend, the

very, very good Treasurer Peter Costello

12(1) Polemic 28

Firstly, in light of Howards goal for media policy (as many owners as possible’), SDTV offered by far the best alternative. Digital technology will allow the radiofrequency spectrum to be used more efficiently, and eliminates the need for buffer channels, creating the potential for an increase in the number of owners in what is a highly concentrated industry. One analogue (the current technology) channel transmits over 7MHz, with 7MHz buffer space to prevent interference. 7MHz allows for four SDTV channels, or one high quality HDTV channel, which the government mandated in its 1998 Act. In the legislation, each incumbent broadcaster was offered 7MHz of spectrum, free of charge (although the spectrum is highly valuable, and is auctioned to telecommunications companies for billions of dollars), as well as the guarantee of no competition until December 2006.

Secondly, HDTV is highly impractical. It requires sophisticated receiving and transmitting technology - high definition video can only be viewed on displays that are large, greater than 90cm. The receiving technology is therefore expensive. In August 2000, the cost of an HDTV was upwards of $20,000. Although the price is expected to fall as economies of scale kick in, a comparison with the SDTV makes the decision to mandate HDTV even stranger: SDTV can be viewed on any television if the signal is converted with a set-top box. HDTV has not been taken up in any country successfully, although SDTV has been very successful in the UK. The Productivity Commission report recommended that HDTV should be permitted but no longer mandated.7 It criticised the legislation as threatening to become a premium service’ for a small number of viewers, disadvantaging those media consumers who view television most heavily: those on low incomes, pensioners and rural viewers.

It seems illogical, contradictory. It is generally accepted that media diversity is desirable, particularly in the interests of democracy. Yet the public interest in diversity of ownership was in this case ignored. Putting the HDTV decision in the context of the policy paralysis’ argument provides an explanation. The need to legislate a standard for digital TV provided the government with the opportunity and impetus for making policy. At the time that all these decisions were being made, it was commented that ‘Kerry Packer couldn’t have written a better amendment himself.’8 Murdoch’s News Ltd potential interest in SDTV and datacasting had been effectively demolished, and it was reported that Murdoch asked of the prime minister “What else did you give Kerry Packer today?”9 Interestingly, the competing interests of the two most powerful media proprietors in Australia were at loggerheads, and the government, like a rabbit frozen in the headlights of an oncoming car, was loath to make a decision that impacted negatively upon either. The difference in the case of digital TV is that necessity of technological change dictates that a decision must be made. In choosing between the interests of two proprietors, one of whom is antagonistic10 and the other who is a ‘friend of the government’ (as illustrated by Jamie Packer’s comments about the Treasurer), which would a Prime Minister choose?

And where, in all of this debate about the welfare of Packer and Murdoch, is the welfare of the consuming public considered? The stream of drivel and

‘Australianised’ facsimiles of American TV programmes, as well as syndicated magazine and press articles dominating the Australian media landscape, indicate

"It is generally accepted that media diversity is desirable, particularly in the interests of democracy. Yet the public interest in diversity of ownership was in this case ignored."

12(1) Polemic 29

that the public interest in diversity of sources and opinion in the maintenance of democracy not perhaps not a high public priority.

Clearly media ownership policymaking is problematic, because the relationship between media and the government is a fractious one. This is particularly so where the media industry is as concentrated as it is in Australia, as John Howard and his government have learnt. Inevitably, it is the incumbent media companies’ interests that will prevail over any other interests (such as the public’s) where this relationship remains unchanged.

Endnotes1 Lange v ABC (1997); also see Theophanus v ABC (1994) and Stephens v ABC

(1994). Expanded (and loosened) the common law defence of qualified privilege with respect to political issues, in accordance with the implied constitutional right of freedom of political discussion Nationwide News v Wills (1992); ACTV (1992).

2 s60 Broadcasting Services Act (1992).3 see Dennis Cryle, 1998, “Niche markets or monopolies? Regional Media,

Government policy and the Cross-Media Review,” Media International Australia: Incorporating Culture and Policy v64 n2, p79.

4 Productivity Commission, 2000, Broadcasting Inquiry, Report no. 11, Ausinfo, Canberra

3 As amended by this government in 1997.6 See Television and Broadcast Services (Digital Conversion) Act 1998.7 Above, n4 at p2598 Greens Senator Bob Brown in Parliament.9 Four Corners Transcript, August 2000, Idiot Box.10 After the decision, headlines in Murdoch newspapers were particularly antagonistic,

as were editorials.

An ^ummefSierkship Program

Are you looking for a Summer Clerkship with a leading national law firm which offers a dynamic program with excellent professional experience in a friendly environment? If so, then Corrs Chambers Westgarth would like to hear from you.

As an expanding national law firm with a commercial focus, we place great emphasis on giving Summer Clerks an in-depth look at all aspects of our operation within an interesting and structured learning program, including:

■ hands on experience in work groups with challenging and interesting work■ mentoring, coaching and advice from senior and junior lawyers■ interactive workshops focusing on legal, professional and personal development■ a full social program with opportunities to meet with all our people

If you would like more information on Summer Clerk opportunities then contact:

Regina Elias Human Resources Coordinator by

phone: 9210 6075 or email: [email protected]

Corrs Chambers Westgarth GPO Box 9925 Sydney NSW 2001

For more information visit our website at: www.corrs.com.au

12(1) Polemic 30