Fold 01 Fragment Screen version

-

Upload

robert-grover -

Category

Documents

-

view

221 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Fold 01 Fragment Screen version

A prompt, a comparison Richard Serra is referring to the ethical intent of his work, what is gleaned from a critical process, however he could just as easily be referring to an architectural condition or possibly even an approach to making architecture, something implicitly fragmentary. I would argue this architecture like Serra’s work is not gestural, not absolutist, not prescriptive of a ‘modus operandi’, not nostalgic, and not adding to a syntax that already exists. This architecture is ‘not looking for affirmation’ or complicity, the emergence of this architectural work as with Serra’s sculpture ‘relies on the process of its making’, not the augmentation of an existing language. A fragment.

Cutting Device: Base Plate-MeasureThe integrity of Serra’s work is concomitant with its process. In ‘Cutting Device: Base Plate-Measure’ a number of diverse elements are juxtaposed to separate and divide the piece. The activity of cutting restructures the field, informing the relationship between disparate parts in a way other than the literal juxtaposition of individual elements. What is poignant is that it takes into account the simultaneity and contradictory nature of the elements present and sorts them into a discernible historical continuum. The significance of it lies in its ethic not its intentions, Serra sets out to constrain the work in a qualified way, or in his own words ‘it’s how we do what we do that conjures a meaning of what we have done’. Serra establishes his own a priori in the way each architectural context presents its own frame and ideological overtones. Serra’s approach and ethic would suggest it’s a matter of the degree to which we choose to interpret them.

The Fragment as a means of understanding an a priori condition

‘I never begin to construct with a specific intention; I don’t work from a priori ideas and theoretical propositions. The structures are the result of experimentation and invention. In every search there is a degree of unforseeability, a sort of troubling feeling, a wonder after the work is complete, after the conclusion. The part of the work that surprises me invariably leads to new works. Call it a glimpse; often this glimpse occurs because of an obscurity which arises from a precise resolution.’ Richard Serra

‘In th

e gift

of w

ater,

in th

e gift

of w

ine,

sky a

nd ea

rth

dwell

. But

the g

ift o

f the

out

pour

ing

is w

hat

mak

es th

e jug

a ju

g. In

the j

ugne

ss of

the j

ug, s

ky a

nd ea

rth

dwell

.’M

arti

n H

eide

gger

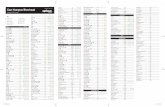

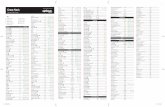

Front PageFragment of the Forma Urbis of Rome

Piranesi, 1756PROMPTING A QUESTION OF ARCHITECTURAL INTENTJoshua Waterstone

A ch

ance

disc

over

y of

a fr

agm

ent f

rom

a c

eram

ic

jug

reve

als

mor

e to

us

than

jus

t th

e fra

gmen

t its

elf.

Our

und

ersta

ndin

g of

its m

ater

ial q

ualit

y, its

wei

ght,

thic

knes

s, ag

e an

d co

lour

ins

tant

ly

give

us a

n id

ea o

f wha

t the

who

le ju

g m

ay h

ave

been

like

. Its

curv

atur

e an

d su

rface

tex

ture

giv

e us

an

impr

essio

n of

the

size

of

the

orig

inal

jug

and

how

it w

as m

ade.

An

imag

e fo

rms

in o

ne’s

min

d of

how

the v

esse

l may

hav

e loo

ked

and

felt.

At t

his

poin

t a

leap

is

mad

e be

twee

n ph

ysic

al

artif

act

and

imag

ined

obj

ect,

in w

hich

one

’s m

ind

begi

ns t

o tu

rn t

he p

otte

r’s w

heel

and

co

mpl

ete

the

piec

e to

one

’s ow

n sp

ecifi

catio

ns;

the

leng

th a

nd s

hape

of t

he s

pout

, the

wid

th o

f th

e ha

ndle

. Our

ow

n th

ough

ts an

d ju

dgem

ents

form

the

rem

aini

ng fr

agm

ents

of th

e pi

ece,

such

th

at i

f an

othe

r pe

rson

wer

e to

stu

dy t

he s

ame

fragm

ent a

diff

eren

t im

agin

ing

may

be a

rriv

ed at

.

In d

oing

so

ther

e is

a ris

k th

at w

e im

agin

e th

e ju

g as

an

obje

ct w

ith s

cien

tifica

lly q

uant

ifiab

le

prop

ertie

s ra

ther

tha

n a

thin

g w

hich

is

part

of

and

defin

ed b

y na

ture

; th

at i

t ha

s a

cultu

ral

auth

entic

ity th

at g

oes b

eyon

d be

ing

a ut

ility

for

man

.

The

read

ing

of a

bui

ldin

g, st

reet

or c

ity si

mila

rly

info

rms

us o

f a

mul

tiplic

ity o

f di

ffere

nt p

iece

s of

info

rmat

ion

mor

e la

yere

d an

d co

mpl

ex t

han

thos

e of

the

jug

fra

gmen

t th

at w

e ca

n ho

ld

betw

een

two

finge

rs.

‘Rat

iona

l’ ju

dgem

ents

are

diffi

cult

to a

rriv

e at

: th

e w

eath

er o

r th

e tim

e of

day

can

cha

nge

the

feel

ing

of a

plac

e. Th

e site

that

the a

rchi

tect

seek

s to

und

ersta

nd a

nd in

som

e w

ay to

add

to is

not

a

fixed

obj

ect

but

rath

er a

shi

fting

, ch

angi

ng,

deca

ying

pl

ace

inha

bite

d by

liv

ing

peop

le.

The

fragm

ents

adde

d or

rem

oved

are

not

of

a di

scer

nibl

e who

le th

at ca

n ev

er b

e com

plet

ed -

to

try

to d

o so

is fu

tile.

Rat

her,

the

arch

itect

ca

n tr

y to

im

bue

the

fragm

ents

whi

ch t

hey

add,

be

they

as

smal

l as

a

door

han

dle

or a

s la

rge

as a

city

blo

ck,

with

qu

aliti

es th

at a

re fe

lt in

the

neig

hbou

ring

piec

es

and

that

conn

ect o

ne w

ith an

idea

of a

n im

agin

ed

who

le.

The

best

outc

ome

is th

at t

he m

ater

ial

piec

es

they

ha

ve

adde

d ea

ch

belo

ng

and

have

an

in

terc

onne

cted

ness

tha

t al

low

s th

em t

o off

er

them

selv

es fo

rth

not j

ust a

s ob

ject

s qu

antifi

able

by

the

ir w

eigh

t or

vol

ume

but

as

thin

gs w

ith

a ne

arne

ss a

nd s

peci

ficity

tha

t is

able

to

gath

er

toge

ther

man

, cul

ture

and

pla

ce.

A F

RA

GM

EN

TE

D W

HO

LEM

atth

ew W

ickha

m

Issue #01

Fragment

foldthinking about architecture

Contributors:

Robert Grover

Philip ShelleyM

atthew W

ickhamAlastair C

rockettM

arcus RothnieJoshua W

aterstone

To contribute please contact foldmagazine.m

ail@gm

ail.com

ww

w.foldmagazine.w

ordpress.com robertjgrover@gm

ail.comphilip.shelley@

gmail.com

wickham

.matthew

@googlem

ail.comacinusa@

hotmail.com

marcus@

rothnie.orgjoshuaw

aterstone@gm

ail.com

Decem

ber 2012

If dust is the destiny of all objects, then fragmentation is the medium-term plan. The fragment is such a ubiquitous figure, we are likely to forget its presence. The very concept is part of a common European cultural inheritance, even the word is shared by most European languages, passed down, mostly in tact, from the Latin fragmentum. It’s telling that more equivalent vernacular words have not performed so well. German, for instance, has Bruchstück (‘broken piece’), but Das Fragment refuses to step aside. Etymological depth grants words a kind of power that they might otherwise lack; a license to signify more than the literal.

In this sense, fragment also implies value. Accordingly, we rarely speak of worthless fragments, but rather bits and pieces. The value of a fragment often depends of what it can tell us about itself and what it can, by implication, tell us more about the things of which it was once part, as well as how it was made. As such, fragments are a form of physical memory; a matrix from which reconstruction can be attempted. This capacity for implication is often enhanced by another property of fragments: that their edges are irregular, uneven, often implying the larger programme of which it was part; of pattern, for instance, or, where location is

preserved, of the arrangement of entire building complexes over time. Even small fragments thus possess an implicate order, which can only be recreated by the efforts of people: by the application of scientific techniques together with the cultural acts of interpretation, discussion, and communication of such insights. As for architecture, might the idea of the fragment go beyond that of physical substance (of, say, building conservation) to be extended to the immaterial, acknowledging its role in the subject and character of our thinking? Might there not be value in embracing the fragmentary quality of knowledge in architecture, rather than pretending it is some organic whole, or ignoring the problem entirely?

Fragmentation can of course also be destructive. It could be argued that the point at which fragmentation becomes undesirable is where the different branches of knowledge and practice can no longer be understood in relation to one another, when the outline of the whole schema is no longer discernible; where fragmentation is disguised as pluralism, when artificial boundaries between disciplines harden, as their common understanding and purposes wither away. Our knowledge is necessarily incomplete, but our thought and actions should, in some sense,

always take account of the larger picture, and the full purposes and potentials of how we shape the world around us. One precarious consequence of this over-fragmentation is the present schism between designers and society, in which the social dimension of architecture in particular is either mistrusted, forgotten, or marginalised, both within and outside of the discipline.

The corrective shift towards a more complete architecture is underway, with thinking and teaching increasingly taking place close to practice. Accepting the fragmentary quality of knowledge, our task is to make it and its overall shape more coherent. This task involves a kind of curation – interpretation, ordering, narrating, setting in place. Indeed, the whole question of how architectural knowledge is to be held and perpetuated in the digital age should also be contended. Sites such as art.sy, an attempt to create a structured public repository of art, promise future revolutions in how we might share and order architectural knowledge in the near future.

In the meantime, an increased openness would be welcome, creating a kind of practice more interested in incorporating valuable precedents and existing structures, with architecture as a social art and cultural practice.

EMBRACING THE FRAGMENTPhilip Shelley

A ST

UD

Y OF FR

AG

ME

NT

Marcus Rothnie

On the western side of the PlaÇa de Carles Buïgas stands a low horizontal building. Its form is unclear; a white horizontal roof to the north appears to float above a reflective void offset, by a solid plane of pale stone to the south. It is an object of illusion; reflections and transparencies distorting the perception of a physical reality.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona pavilion is a place of ambiguity; it is simultaneously knowable and incomprehensible, rational and chaotic, simple and complicated. Solid walls appear to dissolve whilst transparent planes become voids of infinite reflection. It is clearly a building of heavy stone yet floats as though its mass is inconsequential. Inhabiting this structure is like being the edge of Nirvana, yet never being able to achieve enlightenment.

Mies walks a precarious tightrope, traversing a fine line between tantalising ambiguity and meaningless incoherence. Despite its careful detailing and fine craftsmanship The Barcelona Pavilion appears to us incomplete; a piece of reality that alludes to a larger whole beyond the physical limitations of its walls. The building is a fragment of an elusive whole, an allusion to a higher reality slightly beyond reach.

This fragmentary architecture runs counter the Quixotic pursuit of an architectural ideal. A reductionalist world view lends itself to the belief that buildings can become the physical manifestation of rationalist thought. The results are invariably disappointing as they never achieve the ideal they seek to pertain, serving as monuments to the fallibility of man.

The mystical world of the Barcelona Pavilion is a place for dreaming. It is not a failed attempt to achieve a Platonic ideal but a fragment which stimulates personal transendence to an elusive higher reality.

AN ELUSIVE REALITYRobert Grover

We

live

in

an

envi

ronm

ent

whe

re

muc

h ar

chite

ctur

al c

omm

unic

atio

n an

d ed

ucat

ion

is th

roug

h pu

blic

atio

n an

d th

e lim

ited

pers

pect

ive

prov

ided

by

im

ager

y. O

ur

unde

rsta

ndin

g of

ar

chite

ctur

e is

war

ped

by u

se o

f th

is sin

gle

form

of

med

ium

, red

ucin

g a

build

ing

to a

sing

le se

t of

phot

ogra

phs a

nd fo

rmal

dra

win

gs. I

wou

ld a

rgue

th

at re

lianc

e on

a se

t of p

rints

for a

n ap

prec

iatio

n of

the

bui

lt fo

rm l

eads

to

misc

omm

unic

atio

n fro

m t

hese

fra

gmen

ts. Th

is m

iscom

mun

icat

ion

allo

ws

for

both

int

ende

d an

d ac

cide

ntal

mis-

repr

esen

tatio

n of

a b

uild

ing

by it

s aut

hor.

For

a w

eak

proj

ect,

this

fragm

enta

tion

can

be

bene

ficia

l, hi

ghlig

htin

g po

sitiv

e as

pect

s, an

d fa

iling

to

com

men

t up

on t

hose

les

s su

cces

sful.

For

an e

xcel

lent

wor

k, t

his

fragm

enta

tion

can

be d

etrim

enta

l, as

the

lim

ited

capa

city

of

such

pu

blic

atio

n m

etho

ds l

eave

s th

e re

ader

with

out

the

true

leve

l of u

nder

stand

ing

that

a v

isit w

ould

pr

ovid

e.

It co

uld

be c

onsid

ered

tha

t th

e aw

aren

ess

that

a

proj

ect

will

be

prim

arily

exp

erie

nced

thr

ough

a

num

ber

of p

hoto

grap

hs m

ay l

ead

to a

des

igne

r cr

eatin

g m

erel

y a

build

ing

suffi

cien

t to

pro

vide

th

ese

phot

ogra

ph

oppo

rtun

ities

an

d no

thin

g fu

rthe

r. An

exa

mpl

e of

thi

s co

uld

be a

priv

ate

dwel

ling.

The

arch

itect

wish

es t

o us

e th

e pr

ojec

t fo

r pu

blic

ity a

nd g

ener

atin

g fu

rthe

r w

ork

once

co

mpl

eted

. By

pro

vidi

ng a

bui

ldin

g th

at w

ill

satis

fy fi

ve o

r six

cam

era

snap

shot

s m

ay a

chie

ve

this

publ

icity

br

ief,

whi

lst

not

nece

ssar

ily

prod

ucin

g a

grea

t wor

k th

at b

est s

erve

s the

nee

ds

and

aspi

ratio

ns o

f the

clie

nt.

In c

ontr

ast,

ther

e ar

e th

ose

proj

ects

to w

hich

ph

otog

raph

s w

ill n

ot d

o ju

stice

. I r

efer

to

thos

e th

at p

lay

to a

ll th

e se

nses

of

touc

h, s

mel

l an

d so

und

as w

ell

as s

ight

, or

are

jus

t in

capa

ble

of

true

enj

oym

ent

with

out

a vi

sit.

It is

for

such

bu

ildin

gs t

hat

the

fragm

enta

tion

of a

rchi

tect

ure

thro

ugh

imag

ery

is m

ost f

rustr

atin

g, d

imin

ishin

g a

care

fully

con

sider

ed c

reat

ion

of s

pace

int

o a

repr

esen

tatio

n th

at c

an n

ever

ful

ly r

ecre

ate

the

orig

inal

.

Dur

ing

our

educ

atio

n, w

e ar

e ta

ught

of

the

signi

fican

t m

ovem

ents

and

figur

es o

f th

e pa

st th

roug

h ke

y bu

ildin

gs.

How

ever

, ve

ry

rare

ly

do w

e re

ceiv

e th

is tu

ition

thr

ough

visi

ts to

suc

h im

port

ant

proj

ects,

ra

ther

vi

a pr

esen

tatio

ns

cons

istin

g of

a

brie

f ph

otog

raph

ic

over

view

s an

d gl

imps

es o

f for

mal

pla

ns. Th

is do

es n

ot le

ad

to a

pos

ition

whe

re w

e tr

uly

unde

rsta

nd t

he

signi

fican

ce o

f su

ch w

orks

, but

rat

her

deve

lop

a su

perfi

cial

vie

w o

f ho

w w

e co

nsid

er t

he p

hysic

al

form

dep

icte

d in

the

imag

ery.

Poss

ibly

this

is ju

st th

e res

ult o

f a w

orld

whe

re th

ere i

s so

muc

h to

see,

an

d a

limite

d tim

e in

whi

ch to

exp

erie

nce

it. W

e ar

e re

quire

d to

res

ort

to f

ragm

ents,

as

anyt

hing

la

rger

wou

ld li

mit

the n

umbe

r of p

roje

cts i

t wou

ld

be p

ossib

le to

disc

over

.

May

be

this

fragm

enta

tion

is w

hy

mod

ern

build

ings

of

ten

feel

so

ov

erdo

ne,

exce

ssiv

ely

borr

owin

g fe

atur

es

from

m

any

prec

eden

ts th

at l

ead

to a

cob

bled

tog

ethe

r co

mpo

sitio

n w

ith n

o ov

er r

idin

g ae

sthet

ic o

r ch

arac

ter.

The

wea

lth o

f fra

gmen

ted

influ

ence

s th

at w

e ha

ve

at o

ur fi

nger

tips

lead

s to

a c

lutte

red

min

d an

d su

bseq

uent

ly o

ver-

busy

arc

hite

ctur

e. If

we w

ere t

o re

duce

the

quan

tity

of a

rchi

tect

ural

snip

pets

that

w

e vie

w, an

d ra

ther

conc

entr

ate o

n th

e qua

lity

and

dept

h of

arc

hite

ctur

e th

at w

e ex

perie

nce

perh

aps

we,

as

the

next

gen

erat

ion,

can

ful

ly u

nder

stand

th

e bu

ildin

gs th

at w

e w

ant t

o cr

eate

and

form

an

era

of a

rchi

tect

ure

that

can

not b

e su

mm

ed u

p by

fra

gmen

ted

imag

es.

MIS

CO

MM

UN

ICAT

ION

TH

RO

UG

H F

RA

GM

EN

TAT

ION

Alas

tair

Cro

cket

t

A prompt, a comparison Richard Serra is referring to the ethical intent of his work, what is gleaned from a critical process, however he could just as easily be referring to an architectural condition or possibly even an approach to making architecture, something implicitly fragmentary. I would argue this architecture like Serra’s work is not gestural, not absolutist, not prescriptive of a ‘modus operandi’, not nostalgic, and not adding to a syntax that already exists. This architecture is ‘not looking for affirmation’ or complicity, the emergence of this architectural work as with Serra’s sculpture ‘relies on the process of its making’, not the augmentation of an existing language. A fragment.

Cutting Device: Base Plate-MeasureThe integrity of Serra’s work is concomitant with its process. In ‘Cutting Device: Base Plate-Measure’ a number of diverse elements are juxtaposed to separate and divide the piece. The activity of cutting restructures the field, informing the relationship between disparate parts in a way other than the literal juxtaposition of individual elements. What is poignant is that it takes into account the simultaneity and contradictory nature of the elements present and sorts them into a discernible historical continuum. The significance of it lies in its ethic not its intentions, Serra sets out to constrain the work in a qualified way, or in his own words ‘it’s how we do what we do that conjures a meaning of what we have done’. Serra establishes his own a priori in the way each architectural context presents its own frame and ideological overtones. Serra’s approach and ethic would suggest it’s a matter of the degree to which we choose to interpret them.

The Fragment as a means of understanding an a priori condition

‘I never begin to construct with a specific intention; I don’t work from a priori ideas and theoretical propositions. The structures are the result of experimentation and invention. In every search there is a degree of unforseeability, a sort of troubling feeling, a wonder after the work is complete, after the conclusion. The part of the work that surprises me invariably leads to new works. Call it a glimpse; often this glimpse occurs because of an obscurity which arises from a precise resolution.’ Richard Serra

‘In the gift of water, in the gift of w

ine, sky and earth dwell. But the gift of the outpouring is w

hat m

akes the jug a jug. In the jugness of the jug, sky and earth dwell.’

Martin H

eidegger

Front PageFragment of the Forma Urbis of Rome

Piranesi, 1756

PROMPTING A QUESTION OF ARCHITECTURAL INTENTJoshua Waterstone

A chance discovery of a fragment from

a ceramic

jug reveals more to us than just the fragm

ent itself. O

ur understanding of its material quality,

its weight, thickness, age and colour instantly

give us an idea of what the w

hole jug may have

been like. Its curvature and surface texture give us an im

pression of the size of the original jug and how

it was m

ade. An image form

s in one’s m

ind of how the vessel m

ay have looked and felt.

At this point a leap is made betw

een physical artifact and im

agined object, in which one’s

mind begins to turn the potter’s w

heel and com

plete the piece to one’s own specifications;

the length and shape of the spout, the width of

the handle. Our ow

n thoughts and judgements

form the rem

aining fragments of the piece, such

that if another person were to study the sam

e fragm

ent a different imagining m

ay be arrived at.

In doing so there is a risk that we im

agine the jug as an object w

ith scientifically quantifiable

properties rather than a thing which is part of

and defined by nature; that it has a cultural authenticity that goes beyond being a utility for m

an.

The reading of a building, street or city sim

ilarly inform

s us of a multiplicity of different pieces

of information m

ore layered and complex than

those of the jug fragment that w

e can hold betw

een two fingers.

‘Rational’ judgem

ents are difficult to arrive at:

the weather or the tim

e of day can change the feeling of a place. Th

e site that the architect seeks to understand and in som

e way to add to is not

a fixed object but rather a shifting, changing, decaying

place inhabited

by living

people. Th

e fragments added or rem

oved are not of a discernible w

hole that can ever be completed - to

try to do so is futile.

Rather,

the architect

can try

to im

bue the

fragments w

hich they add, be they as small as

a door handle or as large as a city block, with

qualities that are felt in the neighbouring pieces and that connect one w

ith an idea of an imagined

whole.

The best outcom

e is that the material pieces

they have

added each

belong and

have an

interconnectedness that allows them

to offer them

selves forth not just as objects quantifiable by their w

eight or volume but as things w

ith a nearness and specificity that is able to gather together m

an, culture and place.

A FR

AG

ME

NT

ED

WH

OLE

Matthew

Wickham

Issue #01

Fragment

fold thinking about architecture

Con

trib

utor

s:Ro

bert

Gro

ver

Phili

p Sh

elle

yM

atth

ew W

ickh

amAl

asta

ir C

rock

ett

Mar

cus R

othn

ieJo

shua

Wat

ersto

ne

To c

ontr

ibut

e pl

ease

con

tact

fold

mag

azin

e.mai

l@gm

ail.c

om

ww

w.fo

ldm

agaz

ine.w

ordp

ress.

comrobe

rtjg

rove

r@gm

ail.c

omph

ilip.

shell

ey@

gmai

l.com

wick

ham

.mat

thew

@go

oglem

ail.c

omac

inus

a@ho

tmai

l.com

mar

cus@

roth

nie.o

rgjo

shua

wat

ersto

ne@

gmai

l.com

Dec

embe

r 201

2

A pr

ompt

, a co

mpa

riso

n R

icha

rd S

erra

is r

efer

ring

to t

he e

thic

al in

tent

of

his

wor

k, w

hat i

s gl

eane

d fro

m a

crit

ical

pro

cess

, ho

wev

er h

e co

uld

just

as e

asily

be

refe

rrin

g to

an

arc

hite

ctur

al c

ondi

tion

or p

ossib

ly e

ven

an

appr

oach

to

m

akin

g ar

chite

ctur

e,

som

ethi

ng

impl

icitl

y fra

gmen

tary

. I

wou

ld

argu

e th

is ar

chite

ctur

e lik

e Se

rra’s

wor

k is

not

gestu

ral,

not

abso

lutis

t, no

t pre

scrip

tive

of a

‘mod

us o

pera

ndi’,

no

t no

stalg

ic,

and

not

addi

ng t

o a

synt

ax t

hat

alre

ady

exist

s. Th

is ar

chite

ctur

e is

‘not

loo

king

fo

r affi

rmat

ion’

or

com

plic

ity,

the

emer

genc

e of

th

is ar

chite

ctur

al w

ork

as w

ith S

erra

’s sc

ulpt

ure

‘relie

s on

the

pro

cess

of

its m

akin

g’,

not

the

augm

enta

tion

of an

exist

ing

lang

uage

. A fr

agm

ent.

Cut

ting

Dev

ice:

Bas

e Pla

te-M

easu

reTh

e in

tegr

ity

of

Serr

a’s

wor

k is

conc

omita

nt

with

its

proc

ess.

In ‘C

uttin

g D

evic

e: B

ase

Plat

e-M

easu

re’

a nu

mbe

r of

di

vers

e el

emen

ts ar

e ju

xtap

osed

to

sepa

rate

and

div

ide

the

piec

e. Th

e ac

tivity

of c

uttin

g re

struc

ture

s the

fiel

d, in

form

ing

the

rela

tions

hip

betw

een

disp

arat

e pa

rts

in a

way

ot

her

than

the

lite

ral j

uxta

posit

ion

of in

divi

dual

el

emen

ts. W

hat

is po

igna

nt i

s th

at i

t ta

kes

into

ac

coun

t the

sim

ulta

neity

and

cont

radi

ctor

y na

ture

of

the

ele

men

ts pr

esen

t an

d so

rts

them

int

o a

disc

erni

ble

histo

rical

con

tinuu

m. Th

e sig

nific

ance

of

it li

es in

its

ethi

c no

t its

inte

ntio

ns, S

erra

set

s ou

t to

con

strai

n th

e w

ork

in a

qua

lified

way

, or

in h

is ow

n w

ords

‘it’

s ho

w w

e do

wha

t w

e do

th

at c

onju

res

a m

eani

ng o

f w

hat

we

have

don

e’.

Serr

a es

tabl

ishes

his

own

a pr

iori

in th

e w

ay e

ach

arch

itect

ural

con

text

pre

sent

s its

ow

n fra

me

and

ideo

logi

cal o

vert

ones

. Ser

ra’s

appr

oach

and

eth

ic

wou

ld su

gges

t it’s

a m

atte

r of t

he d

egre

e to

whi

ch

we

choo

se to

inte

rpre

t the

m.

The F

ragm

ent a

s a m

eans

of u

nder

stand

ing

an a

prio

ri co

nditi

on

‘I ne

ver b

egin

to co

nstr

uct w

ith a

spec

ific i

nten

tion;

I do

n’t w

ork

from

a p

riori

idea

s and

theo

retic

al

prop

ositi

ons.

The s

truc

ture

s are

the r

esult

of ex

perim

enta

tion

and

inve

ntio

n. In

ever

y sea

rch

ther

e is a

deg

ree

of u

nfor

seeab

ility,

a so

rt o

f tro

ublin

g fee

ling,

a w

onde

r afte

r the

wor

k is

com

plet

e, af

ter t

he co

nclu

sion.

The

part

of t

he w

ork

that

surp

rises

me i

nvar

iabl

y lea

ds to

new

wor

ks. C

all i

t a g

limps

e; of

ten

this

glim

pse o

ccur

s be

caus

e of a

n ob

scurit

y whi

ch a

rises

from

a p

recis

e reso

lutio

n.’

R

icha

rd S

erra

‘In the gift of water, in the gift of wine, sky and earth dwell. But the gift of the outpouring is what makes the jug a jug. In the jugness of the jug, sky and earth dwell.’Martin Heidegger

Front PageFragm

ent of the Forma U

rbis of Rome

Piranesi, 1756 PR

OM

PT

ING

A Q

UE

STIO

N O

F A

RC

HIT

EC

TU

RA

L IN

TE

NT

Josh

ua W

ater

stone

A chance discovery of a fragment from a ceramic jug reveals more to us than just the fragment itself. Our understanding of its material quality, its weight, thickness, age and colour instantly give us an idea of what the whole jug may have been like. Its curvature and surface texture give us an impression of the size of the original jug and how it was made. An image forms in one’s mind of how the vessel may have looked and felt.

At this point a leap is made between physical artifact and imagined object, in which one’s mind begins to turn the potter’s wheel and complete the piece to one’s own specifications; the length and shape of the spout, the width of the handle. Our own thoughts and judgements form the remaining fragments of the piece, such that if another person were to study the same fragment a different imagining may be arrived at.

In doing so there is a risk that we imagine the jug as an object with scientifically quantifiable

properties rather than a thing which is part of and defined by nature; that it has a cultural authenticity that goes beyond being a utility for man.

The reading of a building, street or city similarly informs us of a multiplicity of different pieces of information more layered and complex than those of the jug fragment that we can hold between two fingers.

‘Rational’ judgements are difficult to arrive at: the weather or the time of day can change the feeling of a place. The site that the architect seeks to understand and in some way to add to is not a fixed object but rather a shifting, changing, decaying place inhabited by living people. The fragments added or removed are not of a discernible whole that can ever be completed - to try to do so is futile.

Rather, the architect can try to imbue the

fragments which they add, be they as small as a door handle or as large as a city block, with qualities that are felt in the neighbouring pieces and that connect one with an idea of an imagined whole.

The best outcome is that the material pieces they have added each belong and have an interconnectedness that allows them to offer themselves forth not just as objects quantifiable by their weight or volume but as things with a nearness and specificity that is able to gather together man, culture and place.

A FRAGMENTED WHOLEMatthew Wickham

Issue #01

Fragment

foldthinking about architecture

Contributors:Robert GroverPhilip ShelleyMatthew WickhamAlastair CrockettMarcus RothnieJoshua Waterstone

To contribute please contact [email protected] www.foldmagazine.wordpress.com

[email protected]@[email protected]@[email protected]@gmail.com

December 2012

If dust

is the

destiny of

all objects,

then fragm

entation is the medium

-term plan. Th

e fragm

ent is such a ubiquitous figure, we are likely

to forget its presence. The very concept is part of

a comm

on European cultural inheritance, even the w

ord is shared by most European languages,

passed down, m

ostly in tact, from the Latin

fragmentum

. It’s telling that more equivalent

vernacular words have not perform

ed so well.

Germ

an, for instance, has Bruchstück (‘broken piece’), but D

as Fragment refuses to step aside.

Etymological depth grants w

ords a kind of pow

er that they might otherw

ise lack; a license to signify m

ore than the literal.

In this

sense, fragm

ent also

implies

value. Accordingly,

we

rarely speak

of w

orthless fragm

ents, but rather bits and pieces. The value

of a fragment often depends of w

hat it can tell us about itself and w

hat it can, by implication, tell us

more about the things of w

hich it was once part,

as well as how

it was m

ade. As such, fragments

are a form of physical m

emory; a m

atrix from

which reconstruction can be attem

pted. Th

is capacity for implication is often enhanced

by another property of fragments: that their

edges are

irregular, uneven,

often im

plying the larger program

me of w

hich it was part;

of pattern, for instance, or, where location is

preserved, of the arrangement of entire building

complexes

over tim

e. Even

small

fragments

thus possess an implicate order, w

hich can only be recreated by the efforts of people: by the application of scientific techniques together w

ith the cultural acts of interpretation, discussion, and com

munication of such insights.

As for

architecture, m

ight the

idea of

the fragm

ent go beyond that of physical substance (of, say, building conservation) to be extended to the im

material, acknow

ledging its role in the subject and character of our thinking? M

ight there not be value in em

bracing the fragmentary

quality of knowledge in architecture, rather than

pretending it is some organic w

hole, or ignoring the problem

entirely?

Fragmentation can of course also be destructive.

It could be argued that the point at which

fragmentation becom

es undesirable is where the

different branches of knowledge and practice

can no longer be understood in relation to one another, w

hen the outline of the whole schem

a is no longer discernible; w

here fragmentation is

disguised as pluralism, w

hen artificial boundaries betw

een disciplines harden, as their comm

on understanding and purposes w

ither away. O

ur know

ledge is necessarily incomplete, but our

thought and actions should, in some sense,

always take account of the larger picture, and the

full purposes and potentials of how w

e shape the w

orld around us. One precarious consequence

of this over-fragmentation is the present schism

betw

een designers and society, in which the

social dimension of architecture in particular is

either mistrusted, forgotten, or m

arginalised, both w

ithin and outside of the discipline.

The corrective shift tow

ards a more com

plete architecture is underw

ay, with thinking and

teaching increasingly

taking place

close to

practice. Accepting the fragmentary quality of

knowledge, our task is to m

ake it and its overall shape m

ore coherent. This task involves a kind

of curation – interpretation, ordering, narrating, setting in place. Indeed, the w

hole question of how

architectural knowledge is to be held and

perpetuated in the digital age should also be contended. Sites such as art.sy, an attem

pt to create a structured public repository of art, prom

ise future revolutions in how w

e might

share and order architectural knowledge in the

near future.

In the meantim

e, an increased openness would

be welcom

e, creating a kind of practice more

interested in incorporating valuable precedents and existing structures, w

ith architecture as a social art and cultural practice.

EM

BR

AC

ING

TH

E FRA

GM

EN

TPhilip Shelley

A STUDY OF FRAGMENTMarcus Rothnie

On

the

wes

tern

side

of t

he P

laÇa

de

Car

les B

uïga

s sta

nds a

low

hor

izont

al

build

ing.

Its

form

is u

ncle

ar; a

whi

te h

orizo

ntal

roof

to th

e no

rth

appe

ars

to fl

oat a

bove

a r

eflec

tive

void

offs

et, b

y a

solid

pla

ne o

f pal

e sto

ne to

the

sout

h.

It is

an o

bjec

t of i

llusio

n; r

eflec

tions

and

tran

spar

enci

es d

istor

ting

the

perc

eptio

n of

a p

hysic

al re

ality

.

Ludw

ig M

ies

van

der

Rohe

’s Ba

rcel

ona

pavi

lion

is a

plac

e of

am

bigu

ity;

it is

simul

tane

ously

kno

wab

le a

nd in

com

preh

ensib

le, r

atio

nal a

nd c

haot

ic,

simpl

e an

d co

mpl

icat

ed.

Solid

wal

ls ap

pear

to d

issol

ve w

hilst

tran

spar

ent

plan

es b

ecom

e vo

ids o

f infi

nite

refle

ctio

n. I

t is c

lear

ly a

bui

ldin

g of

hea

vy

stone

yet

floa

ts as

tho

ugh

its m

ass

is in

cons

eque

ntia

l. I

nhab

iting

thi

s str

uctu

re is

like

bei

ng th

e ed

ge o

f Nirv

ana,

yet

nev

er b

eing

abl

e to

ach

ieve

en

light

enm

ent.

Mie

s wal

ks a

pre

cario

us ti

ghtro

pe, t

rave

rsin

g a

fine

line

betw

een

tant

alisi

ng

ambi

guity

and

mea

ning

less

inco

here

nce.

Des

pite

its

care

ful d

etai

ling

and

fine c

rafts

man

ship

The B

arce

lona

Pav

ilion

appe

ars t

o us

inco

mpl

ete;

a pi

ece

of re

ality

that

allu

des t

o a l

arge

r who

le b

eyon

d th

e phy

sical

lim

itatio

ns o

f its

wal

ls. Th

e bui

ldin

g is

a fra

gmen

t of a

n el

usiv

e who

le, a

n al

lusio

n to

a hi

gher

re

ality

slig

htly

bey

ond

reac

h.

This

fragm

enta

ry a

rchi

tect

ure

runs

cou

nter

the

Qui

xotic

pur

suit

of a

n ar

chite

ctur

al id

eal.

A re

duct

iona

list w

orld

vie

w le

nds i

tself

to th

e bel

ief t

hat

build

ings

can

beco

me t

he p

hysic

al m

anife

statio

n of

ratio

nalis

t tho

ught

. Th

e re

sults

are

inva

riabl

y di

sapp

oint

ing

as th

ey n

ever

ach

ieve

the

idea

l the

y se

ek

to p

erta

in, s

ervi

ng a

s mon

umen

ts to

the

falli

bilit

y of

man

.

The

mys

tical

wor

ld o

f th

e Ba

rcel

ona

Pavi

lion

is a

plac

e fo

r dr

eam

ing.

It

is no

t a

faile

d at

tem

pt t

o ac

hiev

e a

Plat

onic

idea

l but

a f

ragm

ent

whi

ch

stim

ulat

es p

erso

nal t

rans

ende

nce

to a

n el

usiv

e hi

gher

real

ity.

AN

ELU

SIV

E R

EA

LIT

YRo

bert

Gro

ver

We live in an environment where much architectural communication and education is through publication and the limited perspective provided by imagery. Our understanding of architecture is warped by use of this single form of medium, reducing a building to a single set of photographs and formal drawings. I would argue that reliance on a set of prints for an appreciation of the built form leads to miscommunication from these fragments. This miscommunication allows for both intended and accidental mis-representation of a building by its author.

For a weak project, this fragmentation can be beneficial, highlighting positive aspects, and failing to comment upon those less successful. For an excellent work, this fragmentation can be detrimental, as the limited capacity of such publication methods leaves the reader without the true level of understanding that a visit would provide.

It could be considered that the awareness that a project will be primarily experienced through a number of photographs may lead to a designer creating merely a building sufficient to provide these photograph opportunities and nothing further. An example of this could be a private dwelling. The architect wishes to use the project for publicity and generating further work once completed. By providing a building that will satisfy five or six camera snapshots may achieve this publicity brief, whilst not necessarily producing a great work that best serves the needs and aspirations of the client.

In contrast, there are those projects to which photographs will not do justice. I refer to those that play to all the senses of touch, smell and sound as well as sight, or are just incapable of true enjoyment without a visit. It is for such buildings that the fragmentation of architecture through imagery is most frustrating, diminishing a carefully considered creation of space into a representation that can never fully recreate the original.

During our education, we are taught of the significant movements and figures of the past through key buildings. However, very rarely do we receive this tuition through visits to such important projects, rather via presentations consisting of a brief photographic overviews and glimpses of formal plans. This does not lead to a position where we truly understand the significance of such works, but rather develop a superficial view of how we consider the physical form depicted in the imagery. Possibly this is just the result of a world where there is so much to see, and a limited time in which to experience it. We are required to resort to fragments, as anything larger would limit the number of projects it would be possible to discover.

Maybe this fragmentation is why modern buildings often feel so overdone, excessively borrowing features from many precedents that lead to a cobbled together composition with no over riding aesthetic or character. The wealth of fragmented influences that we have at our fingertips leads to a cluttered mind and subsequently over-busy architecture. If we were to reduce the quantity of architectural snippets that we view, and rather concentrate on the quality and depth of architecture that we experience perhaps we, as the next generation, can fully understand the buildings that we want to create and form an era of architecture that cannot be summed up by fragmented images.

MISCOMMUNICATION THROUGH FRAGMENTATIONAlastair Crockett

If dust is the destiny of all objects, then fragmentation is the medium-term plan. The fragment is such a ubiquitous figure, we are likely to forget its presence. The very concept is part of a common European cultural inheritance, even the word is shared by most European languages, passed down, mostly in tact, from the Latin fragmentum. It’s telling that more equivalent vernacular words have not performed so well. German, for instance, has Bruchstück (‘broken piece’), but Das Fragment refuses to step aside. Etymological depth grants words a kind of power that they might otherwise lack; a license to signify more than the literal.

In this sense, fragment also implies value. Accordingly, we rarely speak of worthless fragments, but rather bits and pieces. The value of a fragment often depends of what it can tell us about itself and what it can, by implication, tell us more about the things of which it was once part, as well as how it was made. As such, fragments are a form of physical memory; a matrix from which reconstruction can be attempted. This capacity for implication is often enhanced by another property of fragments: that their edges are irregular, uneven, often implying the larger programme of which it was part; of pattern, for instance, or, where location is

preserved, of the arrangement of entire building complexes over time. Even small fragments thus possess an implicate order, which can only be recreated by the efforts of people: by the application of scientific techniques together with the cultural acts of interpretation, discussion, and communication of such insights. As for architecture, might the idea of the fragment go beyond that of physical substance (of, say, building conservation) to be extended to the immaterial, acknowledging its role in the subject and character of our thinking? Might there not be value in embracing the fragmentary quality of knowledge in architecture, rather than pretending it is some organic whole, or ignoring the problem entirely?

Fragmentation can of course also be destructive. It could be argued that the point at which fragmentation becomes undesirable is where the different branches of knowledge and practice can no longer be understood in relation to one another, when the outline of the whole schema is no longer discernible; where fragmentation is disguised as pluralism, when artificial boundaries between disciplines harden, as their common understanding and purposes wither away. Our knowledge is necessarily incomplete, but our thought and actions should, in some sense,

always take account of the larger picture, and the full purposes and potentials of how we shape the world around us. One precarious consequence of this over-fragmentation is the present schism between designers and society, in which the social dimension of architecture in particular is either mistrusted, forgotten, or marginalised, both within and outside of the discipline.

The corrective shift towards a more complete architecture is underway, with thinking and teaching increasingly taking place close to practice. Accepting the fragmentary quality of knowledge, our task is to make it and its overall shape more coherent. This task involves a kind of curation – interpretation, ordering, narrating, setting in place. Indeed, the whole question of how architectural knowledge is to be held and perpetuated in the digital age should also be contended. Sites such as art.sy, an attempt to create a structured public repository of art, promise future revolutions in how we might share and order architectural knowledge in the near future.

In the meantime, an increased openness would be welcome, creating a kind of practice more interested in incorporating valuable precedents and existing structures, with architecture as a social art and cultural practice.

EMBRACING THE FRAGMENTPhilip Shelley

A S

TU

DY

OF

FRA

GM

EN

TM

arcu

s Rot

hnie

On the western side of the PlaÇa de Carles Buïgas stands a low horizontal building. Its form is unclear; a white horizontal roof to the north appears to float above a reflective void offset, by a solid plane of pale stone to the south. It is an object of illusion; reflections and transparencies distorting the perception of a physical reality.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona pavilion is a place of ambiguity; it is simultaneously knowable and incomprehensible, rational and chaotic, simple and complicated. Solid walls appear to dissolve whilst transparent planes become voids of infinite reflection. It is clearly a building of heavy stone yet floats as though its mass is inconsequential. Inhabiting this structure is like being the edge of Nirvana, yet never being able to achieve enlightenment.

Mies walks a precarious tightrope, traversing a fine line between tantalising ambiguity and meaningless incoherence. Despite its careful detailing and fine craftsmanship The Barcelona Pavilion appears to us incomplete; a piece of reality that alludes to a larger whole beyond the physical limitations of its walls. The building is a fragment of an elusive whole, an allusion to a higher reality slightly beyond reach.

This fragmentary architecture runs counter the Quixotic pursuit of an architectural ideal. A reductionalist world view lends itself to the belief that buildings can become the physical manifestation of rationalist thought. The results are invariably disappointing as they never achieve the ideal they seek to pertain, serving as monuments to the fallibility of man.

The mystical world of the Barcelona Pavilion is a place for dreaming. It is not a failed attempt to achieve a Platonic ideal but a fragment which stimulates personal transendence to an elusive higher reality.

AN ELUSIVE REALITYRobert Grover

We

live in

an environm

ent w

here m

uch architectural com

munication and education is

through publication and the limited perspective

provided by

imagery.

Our

understanding of

architecture is warped by use of this single form

of m

edium, reducing a building to a single set of

photographs and formal draw

ings. I would argue

that reliance on a set of prints for an appreciation of the built form

leads to miscom

munication

from these fragm

ents. This m

iscomm

unication allow

s for both intended and accidental mis-

representation of a building by its author.

For a weak project, this fragm

entation can be beneficial,

highlighting positive

aspects, and

failing to comm

ent upon those less successful. For an excellent w

ork, this fragmentation can

be detrimental, as the lim

ited capacity of such publication m

ethods leaves the reader without

the true level of understanding that a visit would

provide.

It could be considered that the awareness that a

project will be prim

arily experienced through a num

ber of photographs may lead to a designer

creating merely a building suffi

cient to provide these

photograph opportunities

and nothing

further. An example of this could be a private

dwelling. Th

e architect wishes to use the project

for publicity and generating further work once

completed. By providing a building that w

ill satisfy five or six cam

era snapshots may achieve

this publicity

brief, w

hilst not

necessarily producing a great w

ork that best serves the needs and aspirations of the client.

In contrast, there are those projects to which

photographs will not do justice. I refer to those

that play to all the senses of touch, smell and

sound as well as sight, or are just incapable of

true enjoyment w

ithout a visit. It is for such buildings that the fragm

entation of architecture through im

agery is most frustrating, dim

inishing a carefully considered creation of space into a representation that can never fully recreate the original.

During our education, w

e are taught of the significant m

ovements and figures of the past

through key

buildings. H

owever,

very rarely

do we receive this tuition through visits to such

important

projects, rather

via presentations

consisting of

a brief

photographic overview

s and glim

pses of formal plans. Th

is does not lead to a position w

here we truly understand the

significance of such works, but rather develop a

superficial view of how

we consider the physical

form depicted in the im

agery. Possibly this is just the result of a w

orld where there is so m

uch to see, and a lim

ited time in w

hich to experience it. We

are required to resort to fragments, as anything

larger would lim

it the number of projects it w

ould be possible to discover.

Maybe

this fragm

entation is

why

modern

buildings often

feel so

overdone, excessively

borrowing

features from

m

any precedents

that lead to a cobbled together composition

with no over riding aesthetic or character. Th

e w

ealth of fragmented influences that w

e have at our fingertips leads to a cluttered m

ind and subsequently over-busy architecture. If w

e were to

reduce the quantity of architectural snippets that w

e view, and rather concentrate on the quality and depth of architecture that w

e experience perhaps w

e, as the next generation, can fully understand the buildings that w

e want to create and form

an era of architecture that cannot be sum

med up by

fragmented im

ages.

MISC

OM

MU

NIC

ATIO

N T

HR

OU

GH

FRA

GM

EN

TATIO

NAlastair C

rockett

If du

st is

the

desti

ny

of

all

obje

cts,

then

fra

gmen

tatio

n is

the

med

ium

-term

pla

n. Th

e fra

gmen

t is s

uch

a ubi

quito

us fi

gure

, we a

re li

kely

to

forg

et it

s pre

senc

e. Th

e ve

ry c

once

pt is

par

t of

a co

mm

on E

urop

ean

cultu

ral i

nher

itanc

e, e

ven

the

wor

d is

shar

ed b

y m

ost E

urop

ean

lang

uage

s, pa

ssed

dow

n, m

ostly

in

tact

, fro

m t

he L

atin

fra

gmen

tum

. It’

s te

lling

tha

t m

ore

equi

vale

nt

vern

acul

ar w

ords

hav

e no

t pe

rform

ed s

o w

ell.

Ger

man

, for

insta

nce,

has

Bru

chstü

ck (

‘bro

ken

piec

e’), b

ut D

as F

ragm

ent

refu

ses

to s

tep

asid

e.

Etym

olog

ical

dep

th g

rant

s w

ords

a k

ind

of

pow

er t

hat

they

mig

ht o

ther

wise

lack

; a li

cens

e to

sign

ify m

ore

than

the

liter

al.

In

this

sens

e,

fragm

ent

also

im

plie

s va

lue.

Ac

cord

ingl

y, w

e ra

rely

sp

eak

of

wor

thle

ss

fragm

ents,

but

rat

her

bits

and

piec

es. Th

e va

lue

of a

fragm

ent o

ften

depe

nds o

f wha

t it c

an te

ll us

ab

out i

tself

and

wha

t it c

an, b

y im

plic

atio

n, te

ll us

m

ore

abou

t the

thin

gs o

f whi

ch it

was

onc

e pa

rt,

as w

ell a

s how

it w

as m

ade.

As s

uch,

frag

men

ts ar

e a

form

of

phys

ical

mem

ory;

a m

atrix

fro

m

whi

ch re

cons

truc

tion

can

be a

ttem

pted

. Th

is ca

paci

ty f

or im

plic

atio

n is

ofte

n en

hanc

ed

by a

noth

er p

rope

rty

of f

ragm

ents:

tha

t th

eir

edge

s ar

e irr

egul

ar,

unev

en,

ofte

n im

plyi

ng

the

larg

er p

rogr

amm

e of

whi

ch i

t w

as p

art;

of p

atte

rn,

for

insta

nce,

or,

whe

re l

ocat

ion

is

pres

erve

d, o

f the

arr

ange

men

t of e

ntire

bui

ldin

g co

mpl

exes

ov

er

time.

Ev

en

smal

l fra

gmen

ts th

us p

osse

ss a

n im

plic

ate

orde

r, w

hich

can

onl

y be

rec

reat

ed b

y th

e eff

orts

of p

eopl

e: b

y th

e ap

plic

atio

n of

scie

ntifi

c tec

hniq

ues t

oget

her w

ith

the

cultu

ral

acts

of i

nter

pret

atio

n, d

iscus

sion,

an

d co

mm

unic

atio

n of

such

insig

hts.

As

for

arch

itect

ure,

m

ight

th

e id

ea

of

the

fragm

ent

go b

eyon

d th

at o

f ph

ysic

al s

ubsta

nce

(of,

say,

build

ing

cons

erva

tion)

to

be e

xten

ded

to th

e im

mat

eria

l, ac

know

ledg

ing

its ro

le in

the

subj

ect

and

char

acte

r of

our

thi

nkin

g? M

ight

th

ere

not b

e va

lue

in e

mbr

acin

g th

e fra

gmen

tary

qu

ality

of k

now

ledg

e in

arc

hite

ctur

e, ra

ther

than

pr

eten

ding

it is

som

e or

gani

c w

hole

, or i

gnor

ing

the

prob

lem

ent

irely

?

Frag

men

tatio

n ca

n of

cou

rse

also

be

destr

uctiv

e.

It co

uld

be a

rgue

d th

at t

he p

oint

at

whi

ch

fragm

enta

tion

beco

mes

und

esira

ble

is w

here

the

diffe

rent

bra

nche

s of

kno

wle

dge

and

prac

tice

can

no lo

nger

be

unde

rsto

od in

rel

atio

n to

one

an

othe

r, w

hen

the

outli

ne o

f the

who

le s

chem

a is

no lo

nger

disc

erni

ble;

whe

re fr

agm

enta

tion

is di

sgui

sed

as p

lura

lism

, whe

n ar

tifici

al b

ound

arie

s be

twee

n di

scip

lines

har

den,

as

thei

r co

mm

on

unde

rsta

ndin

g an

d pu

rpos

es w

ither

aw

ay.

Our

kn

owle

dge

is ne

cess

arily

inc

ompl

ete,

but

our

th

ough

t an

d ac

tions

sho

uld,

in

som

e se

nse,

alw

ays t

ake a

ccou

nt o

f the

larg

er p

ictu

re, a

nd th

e fu

ll pu

rpos

es a

nd p

oten

tials

of h

ow w

e sh

ape

the

wor

ld a

roun

d us

. O

ne p

reca

rious

con

sequ

ence

of

this

over

-frag

men

tatio

n is

the

pres

ent s

chism

be

twee

n de

signe

rs a

nd s

ocie

ty,

in w

hich

the

so

cial

dim

ensio

n of

arc

hite

ctur

e in

par

ticul

ar is

ei

ther

mist

ruste

d, f

orgo

tten,

or

mar

gina

lised

, bo

th w

ithin

and

out

side

of th

e di

scip

line.

The

corr

ectiv

e sh

ift t

owar

ds a

mor

e co

mpl

ete

arch

itect

ure

is un

derw

ay,

with

thi

nkin

g an

d te

achi

ng

incr

easin

gly

taki

ng

plac

e cl

ose

to

prac

tice.

Ac

cept

ing

the

fragm

enta

ry q

ualit

y of

kn

owle

dge,

our

task

is to

mak

e it

and

its o

vera

ll sh

ape

mor

e co

here

nt. Th

is ta

sk in

volv

es a

kin

d of

cur

atio

n –

inte

rpre

tatio

n, o

rder

ing,

nar

ratin

g,

setti

ng in

pla

ce. I

ndee

d, t

he w

hole

que

stion

of

how

arc

hite

ctur

al k

now

ledg

e is

to b

e he

ld a

nd

perp

etua

ted

in t

he d

igita

l ag

e sh

ould

also

be

cont

ende

d. S

ites

such

as

art.s

y, an

atte

mpt

to

crea

te a

str

uctu

red

publ

ic r

epos

itory

of

art,

prom

ise f

utur

e re

volu

tions

in

how

we

mig

ht

shar

e an

d or

der

arch

itect

ural

kno

wle

dge

in t

he

near

futu

re.

In t

he m

eant

ime,

an

incr

ease

d op

enne

ss w

ould

be

wel

com

e, c

reat

ing

a ki

nd o

f pr

actic

e m

ore

inte

reste

d in

inc

orpo

ratin

g va

luab

le p

rece

dent

s an

d ex

istin

g str

uctu

res,

with

arc

hite

ctur

e as

a

soci

al a

rt a

nd c

ultu

ral p

ract

ice.

EM

BR

AC

ING

TH

E FR

AG

ME

NT

Phili

p Sh

elley

A STUDY OF FRAGMENTMarcus Rothnie

On the w

estern side of the PlaÇa de Carles Buïgas stands a low

horizontal building. Its form

is unclear; a white horizontal roof to the north appears

to float above a reflective void offset, by a solid plane of pale stone to the south. It is an object of illusion; reflections and transparencies distorting the perception of a physical reality.

Ludwig M

ies van der Rohe’s Barcelona pavilion is a place of ambiguity;

it is simultaneously know

able and incomprehensible, rational and chaotic,

simple and com

plicated. Solid walls appear to dissolve w

hilst transparent planes becom

e voids of infinite reflection. It is clearly a building of heavy stone yet floats as though its m

ass is inconsequential. Inhabiting this structure is like being the edge of N

irvana, yet never being able to achieve enlightenm

ent.

Mies w

alks a precarious tightrope, traversing a fine line between tantalising

ambiguity and m

eaningless incoherence. Despite its careful detailing and

fine craftsmanship Th

e Barcelona Pavilion appears to us incomplete; a piece

of reality that alludes to a larger whole beyond the physical lim

itations of its w

alls. The building is a fragm

ent of an elusive whole, an allusion to a higher

reality slightly beyond reach.

This fragm

entary architecture runs counter the Quixotic pursuit of an

architectural ideal. A reductionalist world view

lends itself to the belief that buildings can becom

e the physical manifestation of rationalist thought. Th

e results are invariably disappointing as they never achieve the ideal they seek to pertain, serving as m

onuments to the fallibility of m

an.

The m

ystical world of the Barcelona Pavilion is a place for dream

ing. It is not a failed attem

pt to achieve a Platonic ideal but a fragment w

hich stim

ulates personal transendence to an elusive higher reality.

AN

ELU

SIVE R

EA

LITY

Robert Grover

We live in an environment where much architectural communication and education is through publication and the limited perspective provided by imagery. Our understanding of architecture is warped by use of this single form of medium, reducing a building to a single set of photographs and formal drawings. I would argue that reliance on a set of prints for an appreciation of the built form leads to miscommunication from these fragments. This miscommunication allows for both intended and accidental mis-representation of a building by its author.

For a weak project, this fragmentation can be beneficial, highlighting positive aspects, and failing to comment upon those less successful. For an excellent work, this fragmentation can be detrimental, as the limited capacity of such publication methods leaves the reader without the true level of understanding that a visit would provide.

It could be considered that the awareness that a project will be primarily experienced through a number of photographs may lead to a designer creating merely a building sufficient to provide these photograph opportunities and nothing further. An example of this could be a private dwelling. The architect wishes to use the project for publicity and generating further work once completed. By providing a building that will satisfy five or six camera snapshots may achieve this publicity brief, whilst not necessarily producing a great work that best serves the needs and aspirations of the client.