Fetal methotrexate and misoprostol exposure: The past revisited

-

Upload

marsha-wheeler -

Category

Documents

-

view

213 -

download

1

Transcript of Fetal methotrexate and misoprostol exposure: The past revisited

Fetal Methotrexate and MisoprostolExposure: The Past Revisited

MARSHA WHEELER,1* PATRICK O’MEARA,1 AND MICHELLE STANFORD2

1Denver Health Medical Center, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Department of Pediatrics,Denver, Colorado 802042University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Department of Pediatrics, Denver, Colorado 80262

ABSTRACT

Background: Fetal aminopterin/methotrexate syn-drome was described nearly 50 years ago when theseagents were first used as abortifacients. Physiciansessentially stopped using these agents when the asso-ciated anomalies were recognized. Over the last sev-eral years the use of methotrexate with or withoutmisoprostol for management of ectopic pregnancy andmedical terminations of pregnancy has increased.Methods: A 23-year-old female sought a termination ateight weeks gestation. She was given methotrexatefollowed by misoprostol.Results: The medical termination was unsuccessful.The patient elected to continue the pregnancy second-ary to financial considerations. She presented at 39weeks without intervening prenatal care. She was di-agnosed with severe preeclampsia. At delivery theinfant was hypotonic and growth restricted with multi-ple anomalies.Conclusions: Physicians are increasingly using meth-otrexate with or without misoprostol for treatment ofectopic pregnancies and medical terminations. Clini-cians need to be aware of the characteristic teratologiceffects of these two agents.Teratology 66:73–76, 2002. © 2002 Wiley-Liss, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

In a study by Thiersch (Thiersch ’52), a series of 12patients who had been treated with the oral folic acidantagonist aminopterin during the first trimester ofpregnancy was published. Ten of the 12 pregnanciesresulted in spontaneous abortions whereas two of the12 pregnancies required surgical intervention to com-plete the termination. In the 1960s aminopterin andmethotrexate were commonly used as abortifacients.From the 1950s throughout the early 1970s, multiplereports of congenital malformations, which resultedfrom use of aminopterin or methotrexate as an aborti-facient, were published by Milunsky et al. (Milunsky etal. ’68), Shaw and Steinbach (Shaw and Steinbach ’68),and Powell and Ekert (Powell and Ekert ’71). Subse-quently this use of methotrexate became rare. In the1990s the use of methotrexate with misoprostol as an

abortifacient and methotrexate alone for medical treat-ment of ectopic pregnancies has again increased; how-ever, reports of associated abnormalities have not re-curred. The standard doses for medical termination,which were proposed by Christin-Maitre et al. (Chris-tin-Maitre et al. ’00), are a single dose of 50 mg/m2 ofmethotrexate followed by 800 �g of misoprostol 3–7days later. We present a case of failed medical termi-nation. The patient’s pregnancy resulted in a child withfetal methotrexate associated anomalies without theclassic misoprostol associated defects.

Case study

A 23-year-old G3P2 female sought an abortion at 8weeks from her last menstrual period. She was given100 mg of methotrexate intramuscularly and 800 �g ofmisoprostol vaginally 4 days later. She had no followup until 12 weeks of gestation. At that time she had anultrasound that showed a viable intrauterine preg-nancy. She elected to continue the pregnancy, becauseshe was uninsured and could not pay for a surgicaltermination. The physician would not have billed forhis part of the procedure, but the patient would stillhave been responsible for the hospital charges. She hadno prenatal care until she presented to our institutionat 39 weeks of gestation. At that time she was diag-nosed with severe preeclampsia. On ultrasound thefetus had symmetric growth retardation at signifi-cantly below the 10th centile using the Lubchenco etal.(Lubchenco et al. ’63) intrauterine growth stan-dards. These growth standards were developed in Den-ver and are an appropriate standard for our patientsbut no first or 2.5 centile are available and thereforethey do not reflect the severity of the growth retarda-tion. The estimated fetal weight by ultrasound was1,841 g that is less than the 10th centile by Lubchencoet al.(Lubchenco et al.’63) and the 3rd centile by Hamilet al. (Hamil et al. ’79). The head circumference was28.5 cm that is well below the 10th centile according to

*Correspondence to: Dr. Marsha Wheeler, 777 Bannock Street, MC0660, Denver, CO 80204. E-mail: [email protected]

Received 29 March 2001; Accepted 14 December 2001

Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com).DOI 10.1002/tera.10052

TERATOLOGY 66:73–76 (2002)

© 2002 WILEY-LISS, INC.

Lubchenco et al. (Lubchenco et al. ’63) and less thanthe 5th centile by Hadlock et al. (Hadlock et al. ’83).The biparietal diameter was 8.0 cm that was less thanthe 10th centile by Lubchenco et al. (Lubchenco et al.’63) and less than the 5th centile by Hadlock et al.(Hadlock et al. ’83). The abdominal circumference was28.6 cm that is the less that the 10th centile by Lub-chenco et al. (Lubchenco et al. ’63) and less than the 5thcentile by Hansmann (Hansmann ’85). The femurlength was 7.0 cm that is less than the 10th centile byLubchenco et al. (Lubchenco et al. ’63) and less thanthe 5th centile by Hansmann (Hansmann ’85). Theinfant was in a breech presentation with oligohydram-nios and electronic fetal monitoring was nonreassur-ing. The infant was delivered by cesarean section.

At delivery the female infant was noted to be smallwith dysmorphic features. The weight was 2,050 g thatis well below the 10th centile for 39 weeks by thegrowth parameters prepared by Lubchenco et al. (Lub-chenco et al. ’63). This weight would be at the 3rdcentile according to Tanner et al. (Tanner et al. ’66).The length was 46 cm that is the 3rd centile at 39weeks according to Tanner and Whitehouse (Tannerand Whitehouse ’76). The head circumference was 31cm that was the 3rd centile according to Nellhause(Nellhause ’68). The infant was noted to have milddolichocephaly with a tall forehead. The head lengthmeasurement was 10.8 cm that is �2 SD below normalfor a term infant using the standards published byFeingold and Bossert (Feingold and Bossert ’74). Thecephalic index was 75 based on measurements from theCT scan and is consistent with mild dolichocephaly.The nose was prominent with lateral fullness. The eyeswere felt to be mildly hyperteloric. The bony interor-bital distance measured on CT scan was 1.9 cm thatis at the 97th centile for a term infant according toHansmann (’66). The inner canthal distance was 2cm that is the 25th centile for a 39-week-infant andthe outer canthal distance was 5.2 cm that is the 3rdcentile for 39 weeks according to Merlob et al. (Mer-lob et al. ’84). Because the head was the size of a32-week-fetus, however, these measurements shouldbe compared to the 32-week fetus. In that case, themeasurements were greater than the 95th centile,demonstrating hypertelorism that confirms whatwas apparent clinically. The palpebral fissure lengthwas 1.2 cm, which is well below 2 standard fromnormal for 39 weeks. Normal is �1.4 cm according toJones (Jones ’78). The child had a well-formed phil-trum, small mouth, and was micrognathic. Thehands demonstrated fifth-finger clinodactyly and ex-tra flexion creases on the thumbs. The feet had mildsyndactyly of the second and third toes with 4th and5th toe clinodactyly. The toenails were hypoplasticbut consistent with the small growth restricted dig-its. The hands and toes were carefully examined andshowed no evidence of contraction bands consistentwith misoprostol exposure. The infant was noted tohave hypotonia. Apgars were 4 at 1 min and 8 at 5min. Resuscitation included DeLee suction and 1 min

of positive pressure ventilation. The infant was un-able to maintain normal body temperature. Environ-mental temperature control with an Isolette was re-quired for 5 days. Because of the dysmorphicfeatures, a standard chromosome analysis was sentand interpreted as normal. The family history wasnoncontributory. The child has a sib by a differentfather who is doing well. The maternal urine toxicol-ogy was positive post partum for opiates, barbitu-rates, and Valium. CT scan of the head and neonatalhead ultrasounds showed no evidence of brain pa-thology or malformation. No evidence of skull orossification defects was seen. Both pediatric and ob-stetric genetic consultants evaluated the patient andconcluded that the infant demonstrated some aspectsof the methotrexate syndrome. The infant was dis-charged at 7 days.

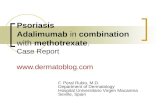

The infant was then evaluated at 12 and 18 monthsof age. At both times she was well below the 10 centilein weight and head circumference. At 18 months thechild was 70 cm tall [�3rd centile by Hamil et al.(Hamil et al. ’79)], her head circumference was 43.5 cm[�3rd centile according to Nellhause (Nellhause ’68)]and weighed 15.7 pounds [�3rd centile by Hamil et al.(Hamil et al. ’79)]. Figure 1 is the child at 18 months ofage. The dysmorphic features did not appear to befamilial. The mother declined formal developmentaltesting of the infant, but the usual developmental mile-stones were stated to be normal.

DISCUSSION

Methotrexate is a folic acid antagonist that has beenused for juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupuserythematosus, psoriasis and other autoimmune disor-ders. Other uses have included chemotherapy, medicalmanagement of ectopic pregnancies and medical termi-nation of pregnancy. The teratologic effects were firstdescribed nearly 50 years ago by Thiersch (Thiersch’52). Subsequent reports include Milunsky et al. (Mi-lunsky et al. ’68), Powell and Ekert (Powell and Ekert’71), and Shawn and Steinbach (Shawn and Steinbach’68). A list of the most common anomalies includes bonymalformation of the skull, globular head, microgna-thia, and hypertelorism. Other facial features in-clude small palpebral fissures, a prominent nose, andmalformed ears. Exposed babies can also have limbanomalies, cleft palate, dislocated hips, and clubfeet.This child had many of the anomalies associated withthe syndrome such as growth restriction, short stat-ure, hypertelorism, micrognathia, small palpebral fis-sures, prominent nose, and limb abnormalities includ-ing syndactyly, clinodactyly, and abnormal flexioncreases.

Early exposure appears to correlate with a greaterdegree of severity, the critical period being between6–8 weeks postconception that was when this infantwas exposed. The threshold dose for teratogenicity isthought to be 10 mg/week as reported by Feldkamp andCarey (Feldkamp and Carey ’93). This patient received

74 WHEELER ET AL.

100 mg in a single dose. Methotrexate interferes withDNA synthesis in actively dividing cells. The specificmechanism by which methotrexate causes a termina-tion, as reported by Crenin et al. (Crenin et al. ’98), isthrough disruption of cytotrophoblast syncytializationresulting in blunting of the expected increase in serum�-human chorionic gonadotropin.

Misoprostol was also given to this patient. Misopros-tol use in the first trimester was reported by Gonzaleset al. (Gonzales et al. ’98) to be associated with Mobiussequence. Infants with Mobius sequence have mask-like facies with sixth and seventh nerve palsies thatare usually bilateral. Other associated anomalies in-clude talipes equinovarus, limb reduction defects, syn-dactyly, and Poland sequence. This child’s dysmorphicfeatures and growth restriction are more consistentwith methotrexate than misoprostol effect but thisagent could have synergistic affects with the metho-trexate.

This case shows the teratologic effect of one dose ofmethotrexate at 8 weeks from her last menstrual pe-riod combined with misoprostol at 8.5 weeks. The lackof prenatal care for the majority of the pregnancy is

problematic in that she may have had other exposuresor infections. The patient’s severe preeclampsia is an-other confounding variable. Severe preeclampsia canbe associated with asymmetric growth restriction withhead sparing. This infant had symmetric growth re-striction. The infants of mothers with preeclampsia areusually are not dysmorphic.

A Pub MED review of the literature from 1964 topresent using the keywords methotrexate, teratology,and pregnancy produced 72 references. Ten of the ref-erences described fetuses exposed to methotrexate.Most exposures were low doses that were given weekly.This case is unique in the use of one intramusculardose at a critical time. Only two references, the 1968manuscript by Milunsky et al. (Milunsky et al. ’68) andthe adult reported by Bawle et al. (Bawle et al. ’98)describe teratologic effects of failed methotrexate ter-minations.

Methotrexate is increasingly being used for two preg-nancy-associated indications: treatment of ectopicpregnancy and medical termination. As a result morecases of fetal methotrexate and misoprostol exposurewill occur. The obstetrician must emphasize close fol-low-up of patients when these agents are used. Physi-cians who see pregnant women with growth retardedfetuses or pediatricians who see these infants afterbirth should consider these in utero exposures. Themother may not readily give a history of these expo-sures secondary to embarrassment. In the health caresystem in the United States a patient can see manydifferent physicians who do not have a centralizedrecord system. The physician who delivers the infantmay be the last to know about exposures that thepatient had early in the pregnancy.

LITERATURE CITED

Bawle EV, Conard JV, Weiss L. 1998. Adult and two children withfetal methotrexate. Teratology 57:51–55.

Christin-Maitre S, Bouchard P, Spitz I. 2000. Medical termination ofpregnancy. N Engl J Med 342:946–956.

Crenin MD, Stewart-Akers AM, DeLoria JA. 1998. Methotrexate ef-fects on trophoblast and the corpus luteum in early pregnancy.Am J Obstet Gynecol 179:604–609.

Feingold M, Bossert WH. 1974. Normal values for selected physicalparameters: an aid to syndrome delineation. Birth Defects OrigArtic Ser 10:1–16.

Feldkamp M, Carey JC, 1993. Clinical teratology counseling andconsultation case report: low dose methotrexate exposure in theearly weeks of pregnancy. Teratology 47:533–539.

Gonzales CH, Marques-Dias MJ, Kim CA, Sugayama SM, Da Paz JA,Huson SM, Holmes LB. 1998. Congenital abnormalities in Brazilianchildren associated with misoprostol misuse in first trimester ofpregnancy. Lancet 351:1624–1627.

Hadlock FP, Deter RL, Harrist RB. 1983. Sonographic detection offetal intrauterine growth retardation. Appl Radiol 12:28–31.

Hamil PV, Drizd TA, Johnson CL, Reed RB, Roche AF, Moore WM.1979 Physical growth: National Center for Health Statistics per-centile. Am J Clin Nutr 32:607–629.

Hansmann CF. 1966. Growth of interorbital distance and skull thick-ness as observed in roentgenographic measurements. Radiology86:87–96.

Hansmann CF. 1985. Ultrasound diagnosis in obstetrics and gynecol-ogy. Berlin: Springer.

Jones KL. 1978. Palpebral fissure size in newborn infants. J Pediatr92:787–790.

Fig. 1. The child at 18 months of age, with a small mouth, smallpalpebral fissures, frontal bossing, and prominent nose with lateralfullness.

FETAL METHOTREXATE AND MISOPROSTOL EXPOSURE 75

Lubchenco LO, Hanson C, Dressler M, Boyd E. 1963. Intrauterinegrowth as estimated from liveborn birth-weight data at 24–42weeks of gestation. Pediatrics 32:793–800.

Merlob P, Sivan Y, Reisner SH. 1984. Anthropometric measurementsof the newborn infant 27–41 gestational weeks. Birth Defects OrigArtic Ser 20:1–52.

Milunsky A, Graef JW, Gaynor NF. 1968 Methotrexate-induced con-genital malformations. J Pediatr 72:679–683.

Nellhause G. 1978. Head circumference from birth to 18 years. Pedi-atrics 41:106–114.

Powell HR, Ekert H. 1971. Methotrexate-induced congenital malfor-mations. Med J Aust 2:1076–1077.

Shaw EB, Steinbach HL. 1968. Aminopterin-induced fetal malforma-tion: survival of infant after attempted abortion. Am J Dis Child115:477–482.

Tanner JM, Whitehouse RH, Takaishsi. 1966. Standard from birth tomaturity for height weight, height velocity, and weight velocity.Arch Dis Child 41:613–617.

Tanner JM, Whitehouse RH. 1976. Clinical longitudinal standards forheight, weight, height velocity, weight velocity, and stages of pu-berty. Arch Dis Child 51:170–179.

Thiersch JB. 1952. Therapeutic abortions with a folic acid antagonist,4 amino pteroylglutamic acid (4-amino PGA) administered by theoral route. Am J Obstet Gynecol 63:1298–1304.

76 WHEELER ET AL.