Fertility's new frontier takes shape in the test tube

Transcript of Fertility's new frontier takes shape in the test tube

N E W S

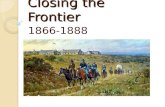

It is day seven of a young woman’s menstrualcycle. More than a dozen small follicles in herovaries respond to the surge of hormones,releasing estrogen, filling with blood andgrowing faster than any other structure in thebody. Within a couple of days, one amongthem becomes dominant, growing evenlarger and protecting and nourishing the eggit carries. The others shrink rapidly, stopsecreting estrogen and disappear.

But what if you could capture those youngfollicles before they shrink into oblivion?What if you could allow each to fulfill its des-tiny and release an egg capable of fertiliza-tion? This fall, scientists at three centers inthe US will initiate a clinical trial to do justthat. Stanford researcher Barry Behr and oth-ers plan to recruit young women with poly-cystic ovary syndrome—who have manymore follicles than average—to collect theirimmature follicles and bathe the cells in anourishing mixture of growth factors, pro-teins, vitamins and amino acids.

The technique, called in vitro maturation(IVM), has already been successful in someEast Asian nations, in Australia and at McGillUniversity in Canada. Nearly 200 babies havebeen born and, so far, all appear perfectlyhealthy.

IVM is one of many new advances in thebooming field of assistive reproductive tech-nology (ART), which burst into fame withthe birth of the first ‘test-tube’ baby in 1978.Today, there are more than a million babiesborn by in vitro fertilization (IVF). In the US,despite the cost of IVF—treatment cyclesaverage $12,000—35,000 IVF babies wereborn in 2000, accounting for nearly 1% of allbabies born that year. Between 1988 and2000, the success rate of IVF in women under35 doubled to nearly 40%.

With a clinical pregnancy rate of 30%,IVM is less efficient than IVF. But the tech-nique allows women to bypass hormonetreatment and offers women with polycysticovary syndrome a safe alternative to IVF, saysBehr, director of the IVF and ART labs atStanford University.

At recent fertility meetings, experts wereheard proudly proclaiming that they would

soon be able to help anyone. At the moment,however, there is little they can do to helpwomen older than 40, who make up at leasthalf of US fertility patients. The IVF successrate in those women drops to just 6%.

To help those who cannot be reached byavailable techniques, there are some bizarretechnologies in the pipeline. Several groupsare trying to create eggs and sperm in the testtube (Nature 424, 364; 2003). Others arefreezing ovarian tissue from patients under-going chemotherapy—but scientists do notyet know how to grow follicles from such anearly stage. Because eggs are usually the limit-ing factor in ART, some groups are perfectingegg-freezing techniques.

Progress in the field is slow because eggsrarely become available, says Roger Gosden,scientific director of the Jones Institute forReproductive Medicine in Virginia.“Most eggsleft over from IVF are stale and faulty,” Gosdennotes. Fertility research relies heavily on animalmodels, particularly farm animals, but theresults do not always hold up in humans.

Even selecting embryos for implantation ismore like a beauty contest than based on anymeaningful markers of fitness, says Gosden.To more accurately judge their merit,embryos can be matured for an additional24–48 hours in vitro—akin to guessing amarathon winner after the 21-mile mark,rather than the 2-mile mark. But doubtsremain about that technique’s safety.

Of mounting concern in the field is the factthat many such procedures are widely adoptedbefore they are proven to be safe. Recent studiessuggest that babies born by ART might be atgreater risk of birth defects, low birth weightand genetic diseases (Nature 422, 656; 2003).But many in the fertility industry have deridedthose studies, citing a lack of adequate controls.

To find meaningful trends in the skimpyand contradictory literature, the Genetics andPublic Policy Center at Johns HopkinsUniversity has assembled a panel of experts,and expects to hold a public forum on thetopic in November. The panel’s report onART risks is expected by the end of the year.

One of the most politically charged issuesin ART is preimplantation genetic diagnosis

(PGD). In use since 1988, PGD is used toscreen for disorders such as cystic fibrosisand familial Alzheimer disease, and for gen-der selection. “[Soon] there will be no IVFwithout PGD,” predicts Yury Verlinsky, direc-tor of the Chicago-based ReproductiveGenetics Institute.

Partly prompted by concerns about PGD,the President’s Council on Bioethics is pon-dering legislative options for ART and isexpected to announce its findings by the endof November. The US fertility industry iscurrently subject only to voluntary self-regu-lation. In most other countries, including theUK and Canada, the government funds andregulates ART.

Verlinsky is one of several researchers whohave been vocal about keeping ART free offederal regulation. Others contend that with-out oversight, it is easy to lose sight of unsa-vory turns research may take. At a recentfertility conference in Madrid, for instance,Israeli scientists announced that they had suc-ceeded in growing egg-producing folliclesfrom aborted fetuses, and US researchers pre-sented evidence of chimeric ‘she-male’human embryos.

“Just look at what goes on out there,” saysJeffrey Kahn, director of the Center forBioethics at the University of Minnesota.Self-regulation may be enough for othermedical techniques, Kahn says, “but forsomething that has societal implications,that’s not a good answer.”

Apoorva Mandavilli, New York

Fertility’s new frontier takes shape in the test tube

p1096 Prion prediction: Are there more vCJD epidemics on the way?

p1099 Icelandic earthquake:Kári Stefánsson likes to shake things up

p1100 Looking ahead:Cutting-edge implants deliver avision of the future

NATURE MEDICINE VOLUME 9 | NUMBER 8 | SEPTEMBER 2003 1095

Precious cargo: Only one mature follicle releasesan oocyte each month, making the egg the limit-ing factor in fertility research.

©20

03 N

atu

re P

ub

lish

ing

Gro

up

h

ttp

://w

ww

.nat

ure

.co

m/n

atu

rem

edic

ine