Fall 2014 COA Magazine

-

Upload

college-of-the-atlantic -

Category

Documents

-

view

244 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Fall 2014 COA Magazine

CREATIVITY: THE ARTS

COAVolume 10 . Number 2 . Fall 2014

THE COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

152472_cover.indd 1 10/29/14 12:55 PM

152472_cover.indd 2 10/29/14 12:34 PM

COAThe College of the Atlantic Magazine

Creativity: The Arts

Letter from the President 3

News from Campus 4

Donor Profile • Cody van Heerden, MPhil '15 9

CREATIVITY: THE ARTS

Introduction • Catherine Clinger 10

Leaping into the Feature • Strange Eyes of Dr. Myes 12

Trouble Dolls • Jennifer Prediger '00 17

Creativity in Motion • Tawanda Chabikwa '07 18

Evolution, Creativity, and Art • A Dialogue 22

Seeking Form • Miles Chapin '10 24

Creativity • The Paths 28

Creative Activism

The Restaurant 30

The Future We Bought 32

Reclaiming Land, Connecting Communities 33

You: Unplugged 34

Poetry • Gregory Bernard '16 and Molly Caldwell '14 35

"Leta" • Grace Goschen '17 36

Alumni & Community Notes 40

On the Doorstep of Europe • Heath Cabot 47

Elmer Beal Retires 48

2014 Commencement Address Excerpt • Mary Harney '96 49

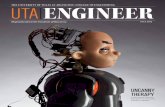

"I want to dance until I disappear, because at some point everything is shed, you're finally as you truly are meant to be — creativity, vitality, life."

Tawanda Chabikwa '07 (photo by Craig Bortmas)

152472_text.indd 1 11/3/14 11:44 PM

The stories in this issue reflect quests. They are personal accounts of alumni, faculty, and students striving to reach out, to connect, to change. Through them we see how we all seek to understand ourselves, our mortality, and our relation to our chosen worlds — from humanity's ancient heritage to the emotional and physical currents of daily life. Miles Chapin '10 carves a four-ton granite block in hopes of connecting two nations — and a smaller block to speak of love. Alexis Gancayco '17 draws a heart eighty-four times in a piece stretching twenty-eight feet as a response to the death of a friend. Tawanda Chabikwa '07 dances, chants, paints, and writes to instill some of the tremors of the primordial balance between humanity and nature into our twenty-first century world. With her distinctive humor, faculty member Nancy Andrews explores human consciousness. Others expand art into public activism to connect a community, confront bureaucracy, or simply remind people of the joyful satisfactions of sustenance.

Such efforts galvanize our full selves. As Ashley Bryan, artist, sculptor, children's book writer, and COA friend says, "The desire to create is what identifies us as being human." (An exhibit reflecting Ashley's life, produced with the help of a host of COA people, is in the Blum Gallery through February — so visit!)

As I write this, the full October moon is rising. I wake to the aroma of wood smoke in the glow of golden birch trees, and fall asleep to the glimmer of moonlight on Penobscot Bay. In the news, emerging from miseries of war, disease, and politics, is the revelation that cave paintings on the island of Sulawesi, Indonesia were created some 40,000 years ago. These paintings are as old, or older, than those on European cave walls. With this evidence that early creativity spanned the globe, scientists are saying that humans were likely making art even before the rafts of Homo sapiens left Africa — possibly even before we became human. Art, these scientists suggest, accompanied a huge growth spurt in human intelligence — something faculty members Helen Hess and Bill Carpenter speculate about here.

When I look at the blue-gray nightscape cast by the radiant moon, I have to wonder, did this surge in creativity evolve so as to comprehend the beauty of our world?

The faculty, students, trustees, staff, and alumni of College of the Atlantic envision a world where people value creativity, intellectual achievement, and diversity of nature and human cultures. With respect and compassion, individuals construct meaningful lives for themselves, gain appreciation of the relationships among all forms of life, and safeguard the heritage of future generations.

COA is published biannually for the College of the Atlantic community. Please send ideas, letters, and submissions (short stories, poetry, and revisits to human ecology essays) to:

COA Magazine, College of the Atlantic105 Eden Street, Bar Harbor, ME 04609 [email protected]

COAThe College of the Atlantic Magazine

Volume 10 · Number 2 · Fall 2014

WWW.COA.EDU

Donna Gold, COA editor

EditorialEditor Donna GoldEditorial Guidance Heather Albert-Knopp '99 Lynn Boulger Catherine Clinger Dru Colbert Darron Collins '92 Jennifer Hughes Katharine Macko Bob Mentzinger Suzanne Morse Steve Ressel Eliza Ruel '13 Lauren Rupp '05 Josh Winer '91Editorial Consultant Bill CarpenterAlumni Consultants Jill Barlow-Kelley Dianne Clendaniel

DesignArt Director Rebecca Hope Woods

COA AdministrationPresident Darron Collins '92Academic Dean Kenneth HillAssociate Academic Deans Catherine Clinger Stephen Ressel Sean Todd Karen WaldronAdministrative Dean Andrew GriffithsDean of Admission Heather Albert-Knopp '99Dean of Institutional Lynn BoulgerAdvancementDean of Student Life Sarah Luke

COA Board of TrusteesBecky Ann BakerDylan BakerTimothy R. BassRonald E. BeardLeslie C. BrewerAlyne CistoneNikhit D'Sa '06Beth GardinerAmy Yeager GeierElizabeth D. HodderPhilip B. Kunhardt III '77Anthony MazlishSuzanne Folds McCullaghSarah A. McDaniel '93

Linda McGillicuddyJay McNally '84Stephen G. MillikenPhilip S.J. MoriartyPhyllis Anina MoriartyLili PewHamilton Robinson, Jr.Nadia RosenthalMarthann Lauver SamekHenry L.P. SchmelzerStephen SullensWilliam N. Thorndike, Jr.Cody van Heerden, MPhil '15

Life TrusteesWilliam G. Foulke, Jr.Samuel M. Hamill, Jr.John N. KellySusan Storey LymanWilliam V.P. NewlinJohn ReevesHenry D. Sharpe, Jr.

Trustee EmeritiDavid Hackett FischerGeorge B.E. HambletonSherry F. HuberHelen PorterCathy L. Ramsdell '78John Wilmerding

COA indicates non-degree alumni by a parenthesis around their year.

Cover: Tawanda Chabikwa '07, photographed by Craig Bortmas (see page 18).

Back Cover: Beech Hill Farm by Ezra Hallett '17. As part of Dru Colbert's Activating Spaces: Installation Artwork class, Ezra turned one of the outbuildings of Beech Hill Farm into a camera obscura. The building became a large-scale pinhole camera. Should you have entered it during the installation, you would have seen this image projected on 10 by 6 feet of sheets hanging on the back wall. The back cover is a digital photograph of the actual projection.

Phot

o by

Bill

Car

pent

er.

152472_text.indd 2 11/3/14 11:44 PM

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE 3

When I consider COA, I think of creativity, for it is one of the most important characteristics we like to cultivate among students, faculty, and staff at College of the Atlantic. My use of the verb cultivate here is strategic because from my experience you neither teach nor learn creativity, but are rather exposed to conditions that encourage it.

Though creativity shows no bias when it comes to disciplines of thought, influencing outcomes in fields as diverse as political science, two-dimensional design, and micro-biology, COA's strategic lack of departments and focus on interdisciplinary approaches more forcefully inspires creative thought. Asking students to apply classroom learning to projects and problems is also something of a catalyst to the creative process, though one can certainly exhibit creative thinking in purely theoretical realms as well. And being at the controls of your own curriculum — that is, designing your own course of study around what you're interested in, what you're perplexed by, or what you're trying to solve — almost requires our students to think creatively about their own education.

You're not likely to come away from reading this issue with a blueprint for how to live a more creative life. That's not our intention. But the pages that follow dispel the myth of creativity as something only for the slightly touched, savant painter, or the scientist suddenly possessed by some mysterious, revelatory "a-ha" moment. When I consider creativity and the creative life, I think of my favorite artist John Coltrane whose wild, sometimes superficially incoherent improvisation is neither random nor mysterious. Coltrane's inspiration emerges from one of the hardest work ethics in jazz, from repetition, from attention to detail, and from supreme concentration and presence.

I like to think our work and our scholarship here on the COA campus, in the Mount Desert Island community, and across the world echoes Coltrane's focus on presence and practice and, in so doing, cultivates the creative spirit amongst us all.

From the President

Darron Collins '92, PhD

Darron, his daughter Molly, and Ashley Bryan at the opening of A Visit With Ashley Bryan (see page 7).

P.S. I want you to know that College of the Atlantic's annual report, previously mailed, will now be offered online each January at coa.edu/developmentliterature.

152472_text.indd 3 11/4/14 11:01 AM

4 FIND MORE STORIES AND PHOTOS AT NEWS.COA.EDU

SEPTEMBER OCTOBER NOVEMBER

A PRINT SHOP IS BORN BEECH HILL FARM BOUNTY

THE GREAT WEST MONSTER COURSE NEAR CALAVERAS

RICH BORDEN: A FACE OF HUMAN ECOLOGY

EARTH IN BRACKETS AT NYC'S CLIMATE MARCH

BLUM GALLERY PRESENTS JENNIFER JUDD-MCGEE (′92)

AUGUSTJULYJUNE

NEWSFROM CAMPUS

Degrees are handed to 76 students from 15 nations and 20 states, including Sean Murphy, the first male staffer to receive a BA, following in the footsteps of former staffers Pamela Parvin '93 and Patricia Ciraulo '94. Commencement speaker Mary Harney '96 (see inside back cover) brings tears to many eyes.

The New York Times publishes an op-ed by Doreen Stabinsky, faculty member in global environmental politics, calling for a global carbon emissions cap, plus substantial investment to make it happen.

Summer events range from a conversation with Jenny Bicks, Sex and the City and Men in Trees writer, and faculty member Jodi Baker, to genome research with trustee Nadia Rosenthal discussing her work in regenerative medicine with Steven Katona, former COA president.

The Peggy Rockefeller Farms obtains a commercial agriculture permit allowing it to fulfill more college and community needs, raising 30 sheep, 50 egg-laying hens, 200 meat chickens, and tending more than 50 apple trees, ½ acre of organic vegetables, and 30 acres of hayland.

Princeton Review rates COA as #3 among top liberal arts schools for "professors get high marks," #9 for best food, and in the top 20 for faculty access, quality of life, and financial aid.

Washington Monthly calls COA one of the top 100 "affordable elite" schools.

The Hatchery, COA's venture incubator, is asked to be a founding member of the University Network of Incubators and Accelerators, administered by the Rice Alliance for Technology and Entrepreneurship at Rice University in Texas.

The year opens with 107 new students — 80 first-years, 23 transfers, and 4 graduates. They hail from 14 nations and 30 states, joining 264 returning students.

COA stands in the top 100 of US News & World Reports' annual rankings, the top 15 for best value, and the top 10 for international students on campus.

Some 20% of COA students, numerous alumni, and faculty and staff attend the People's Climate March in New York City Sept. 21. Alumni Matt Maiorana '11 and Juan Carlos Soriano '11 are on the organizing team.

As they travel the national parks for the Great West 3-credit "monster course," 8 students and faculty members Ken Cline and John Anderson, affirm that water defines the region.

Michelle Pazmiño '17 heads to South Korea as an invited participant of the UN Conference on Biological Diversity.

At the Society for Human Ecology conference faculty member Rich Borden is honored as a "Face of a Human Ecologist" with a plaque in the George B. Dorr Museum of Natural History.

Jay Friedlander, faculty member in socially responsible business, gives a TEDx talk on his concept of the abundance cycle.

Singer-songwriter Dar Williams performs at Gates Community Center ahead of an appearance with Ani DiFranco in New York City.

The Earth in Brackets team is invited to UNFCCC planning meetings in Venezuela as civil society members. Klever Descarpontriez '16, Adrian Fernandez '15, Hiyasmin Saturay '15, and Julian Velez '15 go, along with faculty member Doreen Stabinsky.

152472_text.indd 4 11/3/14 11:44 PM

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE 5

The Fund for Maine Islands Takes COA OffshoreThe COA community has just gotten a whole lot larger. From a small college on a Maine island — albeit a bridged one — it now embraces many of Maine's unbridged, year-round islands. A grant of two million dollars from the Partridge Foundation has created a partnership between COA and the Island Institute, known as the Fund for Maine Islands. The fund will enhance collaborations between the two institutions on issues relating to energy, education, agriculture, and climate change on the islands.

The inaugural project began in September, when fifteen COA students, two alumni, faculty members Jay Friedlander (sustainable business) and Anna Demeo (director of energy education and management), along with individuals from Long Island, Monhegan, Peaks Island, Swan's Island, and Vinalhaven, and two Island Institute staff members, flew across the ocean to the Danish island of Samsø. Through a community-driven, grass-roots effort, Samsø — half the size and one-third the population of Mount Desert Island — has become carbon negative, producing more energy, renewably, than it can use.

In an intensive study that deepens COA's hands-on approach to education, the students are taking a coordinated schedule of three classes (a COA "monster class"), combining the engineering and financing of renewable energy and conservation strategies with the aim of applying these approaches to MDI and Maine's island communities. After the fall term, spent partially at the Samsø Energy Academy, the team will continue to develop

locally appropriate renewable energy strategies for Maine islands.

The fund was announced in August at a launch celebration held at the home of former COA board chair Sam Hamill in Maine's Seal Cove, and attended by renowned journalist Bill Moyers. This fund will empower COA and the Island Institute, "to search for solutions to sustain the ecosystems of these coastal islands," and to share the innovations with the world. Said Moyers, "From this seed in this place can come a new paradigm for the future."

Moyers concluded his remarks with a tribute to Partridge Foundation donor Polly Guth (see Spring 2011). "Once upon a time I might have thought a small island off the coast of Maine hardly the place where a partnership could be forged that might show the world this better way — one of obligation, reciprocity, and cooperation. I would have been wrong. The future begins here and now, this evening, in this small but significant place, this Isles de Polly, with each and all of us."

COA President Darron Collins '92 sees this connection as modeling an essential educational approach, combining the research efforts of the college with real-life applications that can solve, he said, "fundamental challenges that face islands and remote communities elsewhere." Collaboration is essential, added Rob Snyder, Island Institute president, "We could never do alone what we are now able to dream up and implement together."

The COA contingent arrives in Samsø. Back row: Energy academy staff members Michael Larsen, Michael Kristensen, Jesper Roug Kristensen, and Anne Boisen Albertsen. Third row: Zabet NeuCollins '16, Lauren Pepperman '16, Kate Unkel '14, Luke Greco '16, Wade Lyman '15, and Andrya Russell, MPhil '16. Second row: Nick Urban '15, Saren Peetz '15, Nathaniel Diskint, MPhil '16, Zakary Kendall '17, Navi Whitten '17, Surya Karki '16, and Sam Allen '17. Front row: Jay Friedlander, faculty, Rebecca Coombs '15, Anna Demeo, faculty, Malene Lundén and Mads Lundén Hermansen, energy academy staffers, and Paige Nygaard '17. Photo by Søren Hermansen, Samsø Energy Academy director.

152472_text.indd 5 11/3/14 11:44 PM

6 COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

Students in the Wards: Interning at Mount Desert Island HospitalBAR HARBOR, ME — It's one thing to be interested in health and medicine; it's quite another to experience life within a hospital, day after day. An arrangement with Mount Desert Island Hospital now offers COA students an internship within the intensity of hospital life — from toe amputations to childbirths.

"The veil between in-class theory and medical practice has been lifted for me," says Linnea Harrold '15, who spent the summer as the program's inaugural student. "I had the chance to see firsthand what clinicians do, how they interact with patients, the ways they work as a team. I learned so much from just watching how everyone works together, and from talking to patients and their families. It is such a rare and fantastic opportunity."

For ten weeks, Linnea shadowed hospital physicians and nurse practitioners, spending two weeks with each of five specialties. She discussed her observations with

practitioners daily, and each week met with Betsy Corrigan, nurse educator, along with the program's director, Edward B. Gilmore, MD, MACP, the hospital's chief of medicine. "The program was very positively received by colleagues," he says. "Each day Linnea would read about situations she encountered, and return with questions the next day. All the preceptors enjoyed having her around — she even inspired them. One of the refreshing things about bright and perceptive students is that they ask questions that make you think."

"We are so excited, grateful, and appreciative of the opportunity that the hospital is giving our students," adds biology faculty member John Anderson who oversees students interested in medical careers and worked with the hospital to arrange the program. "This is infinitely more powerful than classroom experience; it will prove invaluable in launching a new generation of health professionals."

Current intern Emily Peterson '15 agrees. "I'm excited to apply what I've learned in John's human anatomy class to the hospital setting," she says. "I'm getting an authentic glimpse into the medical field. I've been most surprised by how emotionally intense it can be. It's one thing to read about a health issue; it's another to experience it with a patient."

Her internship completed, Linnea refocused her senior project. Having experienced MDI's hospital — and patients coming in for everything from bug bites to forty-foot falls off Cadillac Mountain — she will look at ethical issues in international aid, and how physicians cope with the often extreme lack of resources.

And the most rewarding aspect of the internship? "The birth of a new person into this world," Linnea says. "The tension, anxiety, pain, and emotion are so overwhelming that the relief of the infant's first sounds brought tears to my eyes. It is the most magical thing I have ever witnessed."

"This internship has been great! I'm getting an authentic glimpse into the medical field," says Emily Peterson '15 (right), as she begins her day interning at Mount Desert Island Hospital by consulting with physician's assistant Kate Worcester.Photo courtesy of MDI Hospital.

152472_text.indd 6 11/3/14 11:44 PM

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE 7

ISLESFORD, ME — When Ashley Bryan tells a story, his fingers snap, his feet tap, and his voice quickens and slows, covering several octaves. He pulls the meaning out of each word, the sound out of each syllable; to him words, like people, like all of life, are momentous. This artist, storyteller, children's book writer and illustrator, puppetmaker, and humanitarian lives just off the shores of Mount Desert Island in the village of Islesford on Little Cranberry Island. Visits to his home, which is filled with artistic miracles — sea-glass stained glass windows, found-object puppets, large-scale flower paintings, and a global toy collection — have inspired legions of COA students. Ashley, now ninety-one, received an honorary MPhil as COA's commencement speaker in 1996.

This summer, thanks in large part to the help of the COA community, the exhibit "A Visit With Ashley Bryan" was launched on the island by the fledgling Ashley Bryan Center. Working with Betts Swanton '88, arts faculty member Dru Colbert designed the exhibit. Aiding them were Eli Mellen '11, MPhil '14 and Danielle Meier '08. Photography lecturer Josh Winer '91 coordinated the process as project manager.

"My involvement has been a labor of love," says Dru. "It is a small reciprocity for Ashley's generosity to COA over the years. Many, many faculty members have taken students out to Islesford to have them feel the palpable energy and spirit that Ashley has toward creative work and life. His philosophy is so close to our human ecological framework: making art from what's around us, and using art to help us see the world more fully."

The exhibit features the astonishing range of Ashley's work and his life in art. Born in the Bronx to parents from Antigua, his childhood was filled with music and color until he was

COA Artists Help Make Ashley Bryan Exhibit HappenA Visit With Ashley Bryan at COA through February

"I want people to have an experience of delight that will tap something so at the roots of enjoyment that it will lift their spirit," says 91-year-old artist Ashley Bryan of the exhibit of his life and work designed by faculty member Dru Colbert (with Ashley, above), along with Bett Swanton '88 and many more COA helping hands. Photo by Josh Winer '91.

drafted from his studies at Cooper Union into the segregated United States Army. Even on D-Day, Bryan concealed a sketchbook in his gas mask to draw his fellow soldiers, seeking, he says, "to preserve my humanity."

The exhibit is in the Ethel H. Blum Gallery through February. Hours are Monday through Saturday, 11 am to 4 pm. Please call 207-288-5015 to be sure of hours during COA's winter break.

152472_text.indd 7 11/3/14 11:44 PM

8 COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

Pipes & Pollution: Students Help Ellsworth Upgrade Drainage By Elena Piekut '09, Ellsworth Assistant City Planner

ELLSWORTH, ME — Lately in Maine, when it rains, it pours. In Ellsworth, where the Union River Watershed's 500 square miles of drainage meet the ocean in a heavily trafficked urban area, rain flows from roads and parking lots through storm drains directly into Card Brook, the Union River, and Blue Hill Bay.

Ellsworth's larger parking lots and stores, many of which were developed in the 1960s and 1970s, sit within the Card Brook Watershed, one that students — under the guidance of Ken Cline, faculty member in environmental policy and law — have been working to improve for more than a decade. Recently, the stakes have been raised. Card Brook fails to meet water quality standards under the Clean Water Act. The likely cause: stormwater runoff from impervious areas.

With Card Brook on the Environmental Protection Agency’s list, Ellsworth can no longer ignore water quality issues. The problem is even more pressing with increases in water quantity

associated with climate change. Along the Maine coast, extreme rain events are now more frequent, more intense, and have shifted in seasonality, with more storms occurring earlier in the year when soils are already saturated from snowmelt. Flooding is a real, costly consequence of local climate change.

COA's Land Use Planning class, taught by Isabel Mancinelli, faculty member in planning and landscape architecture, and Gordon Longsworth '91, GIS Laboratory director, specializes in taking on real, local problems. Last spring it focused on Ellsworth's stormwater drainage in the urban core area of the Card Brook Watershed. As assistant to Ellsworth's city planner, a position I've had since 2012, I helped guide the class — while building my own GIS skills.

Students looked at the location of drains, pipes, and culverts; utilized sophisticated LiDAR topographic data to create maps modeling water flow; updated impervious surface data; considered emergency management;

walked the brook's banks; and proposed green infrastructure solutions. In June, the class presented their findings to members of the planning board, city staff, and local engineers.

The audience was impressed. The students offered a cohesive analysis, educating and energizing our stakeholders. They helped us move forward by providing new data and figuring out what we still need to learn. We're ahead of the curve for a small municipality right now — COA's work helped us win a state grant to collect more data on our stormwater infrastructure.

Ellsworth's next step is to seek funding to implement solutions, hoping to build resiliency against a changing climate and maintain a healthy stream in the center of the city's commercial area. As the students wrote in their presentation, "Card Brook provides a rich ecosystem where frogs and beavers make their home, flowers bloom, and sounds from the city's traffic disappear."

When city officials realized that Ellsworth's stormwater runoff system needed help, COA's Land Use Planning class created detailed maps, such as this one of the area's soil drainage capacity (above left), often using LiDAR, a remote sensing technology measuring distance by analyzing the reflected light of a laser beam to determine the shape of the surface topography (above right).

152472_text.indd 8 11/3/14 11:44 PM

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE 9

Trustee Cody van Heerden is on her third master's degree. At twenty-two she began an MA in geology at Brown University; she then took an MS in oceanography at the Darling Center of the University of Maine. Now that her children have finished college, she's investigating how institutions change, focusing on Maine's lobster industry. Come June 6, 2015, Cody will become the first COA trustee to earn an MPhil in human ecology while serving on the board.

"If I was going to talk the talk, I just felt I should walk the walk," she said over a glass of lemonade at the coffee shop just outside of the three-story Artemis Gallery in Northeast Harbor, which Cody co-runs with Deirdre Swords (wife of Michael Boland '94). Her face, rimmed by shoulder-length straight brown hair, mingles the intensity of the eager scholar with motherly concern.

"I was a trustee, I love academics," she says. "I took an economics course with [COA faculty member] Davis Taylor and I thought he was one of the best teachers I ever had, and that

just inspired me. I was able to see the world through a different lens and I thought, why not take the next step? I knew it would be very challenging, but it's good to challenge yourself. And I really wanted to experience COA in that way, to have the pleasure and privilege of focusing really deeply on something."

The experience, says Cody, has been transformative. The questions of sustainability and resiliency in Davis' Ecological Economics class changed how she looks at what's happening to the earth. She's also studied water issues with law and policy faculty member Ken Cline, and the philosophy of nature and mind with philosophy faculty member John Visvader. "The best teachers I've ever had have been from COA," she adds, without a flicker of hesitation.

Raised outside of New York City, Cody spent summers on an island in central Maine's Belgrade Lakes. "We bathed in the lake using biodegradable soap, we had kerosene lamps, no electricity; we came and went by boat. I liked being outside in nature.

Growing up, catching frogs and turtles after school was my favorite thing to do." Cody almost applied to COA during the school's formative years, but her father thought she needed more structure. Besides, it was at Colby College that she met husband Christiaan van Heerden. That was before he left Colby to become a boat builder and naval architect, which led them to Mount Desert Island, and ultimately linked them both to COA. For after Cody spent a few years at the Department of Environmental Protection, Christiaan took a job with The Hinckley Company and the couple, with their first baby, moved into a home his family had on the island.

Schooling their two daughters immersed Cody in Blue Hill's Waldorf-inspired Bay School, where she taught math for a number of years, rewriting the curriculum and gaining solid insights into how people learn. In 2005 she joined the COA board, seeing in COA qualities similar to the Bay School: "Community. Regard. Respect. Those change everything," she says. "It's what I look for in my life." The connection deepened when Christiaan enrolled at COA, finishing his BA in 2009.

Cody's ties to the college now extend to Artemis Gallery, which tends to hire from the COA community and has featured work by COA students and alumni during each of its three years. This fall, the gallery became the site for the Activating Spaces: Installation Artwork course taught by arts faculty member Dru Colbert.

And what does Cody receive from these connections? "The satisfaction of knowing that COA does what it does, of being a part of that. Unless the world becomes a little bit more like COA, we're in big trouble."

Donor ProfileWalking the Walk: Cody van Heerden, MPhil '15By Donna Gold

Trustee Cody van Heerden, MPhil '15 hikes the Italian coast with her daughters Eliza and Alexi. Photo by Eliza van Heerden.

152472_text.indd 9 11/3/14 11:44 PM

10 COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

One Meditation on CreativityBy Catherine Clinger, faculty member in art and art history

Creativity happens, it does not wait for something to happen. Remaining in a state of anticipation or expectation may prevent us from harnessing our self to a deeper world where potency is paired with disintegration, images form and dissolve. Creativity calls for perseverance, humility, and a devotion to dreaming here in the phenomenal world where the sacred is concealed in plain sight and we miss its signs if we don't pay attention. It is the act of coalescing focus even as the subject of one's attention shifts and changes shape; becomes a line, a circle, a number, a tunnel, or disappears altogether. Creativity is the coming and going, immersion and resistance within a

Creativity is not Art, although Art may be a consequence of creative deliberation. Creativity can be both tender and mighty in its nature; an aggregate of processes and patterns, formative before form. Creativity is movement during stillness, toil during respite. It doesn't always get it right; however, one could argue that it should do no harm. It is not a stopping point or an end, rather it is a ceaselessly evolving tale that describes and constructs experience all at once. The act of creation restores myth to its old dignity and, in so doing, paradoxically builds new mythologies that disrupt timeworn solemnities.

To be is to bring oneself into existence; to imagine is the activation of being-ness beyond a calculated existence; to create is to convert imagination into being. Creativity is the act of

chooses to build a world with, whether it be a world of ideas or things, animate or inanimate; and this mindfulness may be one of the principles of Creativity — the ability to develop concentration without stagnation and to privilege reverie without elevating one's self above another entity.

In our day, the word is bantered about, sometimes with great care, sometimes with great incredulity, often enough with a modicum of lazy application. How do we speak of Creativity here

our gentle nature as an institution.

The Heart is the Hardest to Break, The Heart is the Hardest to Heal by Victoria Alexis Gancayco '17, sharpie on paper and stitching; detail; composed of individual pieces 4"x3½" stitched to extend to 336"x4"(see also pages 28–29).

152472_text.indd 10 11/3/14 11:44 PM

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE 11

152472_text.indd 11 11/3/14 11:44 PM

12 COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

Every artist begins somewhere. When Nancy Andrews, faculty member in performance art and video production, was nine, she drew a pastel "of a very lonely tree" that made it all the way to the Montgomery County Fair. Today her work has been collected by the Museum of Modern Art, but her most ambitious work is still ahead. With three decades of diverse artistic production behind her, this drawing, painting, puppet- and video-making Guggenheim Fellow has embarked on her first feature-length film, The Strange Eyes of Dr. Myes. Behind it will be the queer, complex creativity that expressed itself in a neighborhood art class in suburban Washington, DC circa 1970.

Not that everyone endorsed Nancy's vision quite as heartily as those fair officials. That lonely tree? "Well, the

kid next to me in class could draw Superman perfectly, and that's what I thought you had to do," she says, laughing. "But I suspected that that wasn't true." The daughter of a successful engineer and a former secretary, Nancy knew what the inside of a museum looked like. "One of the markers of middle class aspiration was giving your children cultural experiences: piano lessons, visits to cultural spaces," she says. If the slip of a girl had her bullies, she also had the work of her particular favorite, Paul Klee, to admire — and a burgeoning imaginative life of her own.

Today, much of Nancy's work draws on vaudeville and early film influences. In her world, song-and-dance might punctuate a scrupulously silent animated sequence. Crisp fields of black and white give way to shadows.

And, as in her Ima Plume trilogy (Monkeys and Lumps, The Dreamless Sleep, and The Haunted Camera, created between 2003 and 2005), a film noir homage centered on an artist who attempts to illustrate the unseen, imagination becomes something to investigate. Did her open approach to mystery, her attraction to bathos and black humor coalesce at art school? "Actually, I think my fifth grade teacher is responsible," says Nancy. Mr. Grossman introduced his class to Shakespeare, The Three Stooges, old radio shows, pulp fiction, and opera. He even projected the silent horror classic The Phantom of the Opera onto the classroom movie screen from a 16mm film projector. "I loved all of it," she says. "I had a lot of those 'That's what I'm talking about. That's it,' moments."

Leaping into the Feature: Nancy Andrews' Strange Eyes By Michael Diaz-Griffith '09

152472_text.indd 12 11/3/14 11:44 PM

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE 13

Rebel, rebelFor college, Nancy headed to the Maryland Institute College of Art. As a photography major, "we learned about composition, light, contrast — the basic building blocks of cinematography." She'd been playing around with Super 8 cameras for years and, in addition to film production and film history, took MICA's first course on video technique. She describes borrowing avant-garde films from the Enoch Pratt Library back when a reel in your hand might be the only way to see a particular, potentially life-changing film. With punk rock in the air, it was also a good time for rebellious do-it-yourself art-making. Studying abroad in England, Nancy photographed the butcher hanging slabs of beef — and made earrings out of the prints. Recounting this to the LA Record recently, she said, "I also

made a jumpsuit with clear pockets for pictures related to plastic surgery," showing that, for Nancy, art has always been interdisciplinary.

Nancy never did go to film school; she's always been a human ecologist, assembling her films from multiple sources. A decade after graduating from MICA, she began an MFA program at the The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, not in film but in performance art. The Art Institute is known for fostering interdisciplinarity, a key factor in Nancy's decision to attend. Why the shift to performance art? "The Baltimore scene," she says, with a wry smile. Intense friendships, communal living, supportive community, cheap rent: after MICA she remained in Baltimore, a perfect city for experimental artists at the time. "It was a real art community. People collaborated and helped each other out. There was nothing to compete for: if people wanted to 'make it,' they moved to New York. We made art because we loved to do it." In this context, almost by chance, Nancy formed a three-person band that morphed into a four-person performance group.

Soon they were playing gigs in DC and New York and were written up in the Washington Post. Encouraged, "we wrote more and more songs, and a friend made us crazy costumes," says Nancy. As a performance art troupe they aired on college radio and appeared in the pages of Interview magazine. They were almost booked for a slot on David Letterman's Late Show — "we were too weird, so they cancelled" — and never quite "made it," but it had a major impact on Nancy's art. Those eight years of performance added another dimension to her work in video and film.

Something "stupid" — and profoundIn her 2009 short, On a Phantom Limb, Nancy collages medical footage, drawn animation, and live action to tell the story of birdgirl, "a human-made hybrid, a surgical creation — part woman, part bird — passing

through death, purgatory, and returning to life." Over the course of the film, birdgirl is literally and figuratively reanimated: returned from near-death and rendered visually intelligible by Nancy's brush — and her performance. On one level, says Nancy, the film took shape like most of her art: "I have what I call a 'stupid idea' and just start working with it. It's a collage process."

She continues: "This one idea always dovetails with multiple other things I'm thinking about. Often these things don't fit together in obvious ways, so I sort of force-fit them and ask myself, 'Why am I thinking about things that wash up on beaches — things that can't be identified or assigned a provenance; and at the same time, Jane Goodall and her research on chimpanzees; and Donna Haraway's cyborg theory? Why am I thinking about these things together?' I don't really know, of course, but I use these questions to begin exploring leads."

The process is fundamentally experimental, involving more mystery, contingency, and uncertainty than you'd expect. "It's like going down a dark hallway and just trying a key in every door until you find one that fits. But it's not a singularity: the key is going to open more than one door. It's a blind faith thing. I also use the metaphor of taking a journey without a map. And so it's very much about finding my way as I go along."

Even on the brink of death. The "stupid idea" for On a Phantom Limb can be traced back to the Intensive Care Unit of Brigham and Women's Hospital, where for two weeks in 2005 Nancy fought for her life, remaining hospitalized for another two weeks. She had undergone multiple life-threatening surgeries; now, wracked by delirium and convinced that her doctors and the hospital staff were trying to kill her, she struggled to survive. Diagnosed at the age of twenty with Marfan's Syndrome, a genetic disorder affecting the connective tissues, Nancy was not new to hospital stays. In her senior

152472_text.indd 13 11/3/14 11:44 PM

14 COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

year of college she underwent open-heart surgery to replace a heart valve and part of her aorta affected by an aneurysm. But this time was different. The surgeries were riskier, and her delusions threatened to pull her under. "I was on a raft, in a space-pod, in a fly-by-night health clinic, in a conference room, in a library, in the arctic, in the desert, and even in a hospital, each with its own terrible narrative," she writes in her blog devoted to the art and science of ICU delirium (nancyandrews.net).

Radically healing artNancy credits her partner Dru Colbert, COA faculty member in art and design, with helping to save her life. In a TEDx talk on ICU delirium, Nancy recounts that Dru "offered me a pencil and paper to make drawings. She asked me to draw the dog that I would like to get once we got home. My first drawings were considerably worse than a two-year-old's, just a series of jagged lines. But after a few days I could draw something that resembled an animal, with legs and ears." Nancy continued drawing, creating "a heroic birdgirl avatar that represented myself." It could fly between heaven and earth "to negotiate the space in between, that space that I had inhabited within my delirium."

The drawing helped Nancy piece back her fragmented sense of self. "By externalizing my memories I began to understand how my version of what happened related to what really happened."

On a Phantom Limb, and the projects that followed, are a result of — and a further step in — this healing, though like many who have experienced ICU delirium, Nancy suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder. Her comic book, Loupette and the Moon, tells the story of another of Nancy's "avatars," a girl with the genetic mutation hypertrichosis, commonly known as "werewolf syndrome," in which the face and body are covered by a thick pelt of fur. While Loupette's genetic mutation is different from Nancy's, she says, "the struggles are not so

different — from trying to understand who I am as a person with a genetic mutation that is life-threatening and life-changing to determining how to be defined as a person, and by whom to be defined." On the book's final pages, Loupette escapes from the sanatorium where she is unfairly held, flies to the moon, admires a Ziggy Stardust-like magazine, Mutant Style — and scrubs away the monstrous black shadow projected not by herself but by an uncomprehending society.

Post-ICU, Nancy's work externalizes the bad and internalizes the good: a radical aesthetic project with therapeutic psychological effects for herself and her audience. She says that since Loupette began with images, not words, and since text can reduce the primacy of visual narratives, she kept writing to a minimum, allowing readers to "internalize the experience while actively having to work out what is happening." Something similar is at play in her Ima Plume triology, in which Ima says, "There were things I could draw pictures of, and there were things that couldn't be drawn. More and more I was attracted to the second category. There were things I wanted to describe, but I didn't know how. There were things that I wanted to show but there was no way to show them."

Drawing, for Nancy, is an attempt to describe the indescribable, to show the unshowable.

Filmmaking without a mapHer creative process continues to evolve. Inspiration for her 2010 short, Behind the Eyes are the Ears, came in the form of a song cycle, not images. Drawings were developed later; then the processes intertwined, "so that I might go from doing research to writing a song, to drawing an animation sequence, to finding some film footage, to shooting some live action. I didn't do anything in a neat order." That film, about Dr. Sheri Myes and her revolutionary attempts to expand human perceptions and consciousness, generated the idea for The Strange Eyes of Dr. Myes. She'd

been fantasizing about making a feature-length film for two years. With a month to spare before the COA winter term, and support from a friend who teaches screenwriting, Nancy began to write.

It was a new experience. "If you're making a feature, you want it to have some of the tropes of the popular form: recognizable characters, characters who have relationships, conflicting interests. These things are not my bread and butter," she says with a laugh. "So bringing them to life had to become a focus from the very beginning." Along the way she discovered that "a huge amount of the creativity of making a film comes in the writing." After completing the screenplay, Nancy sent it around to producers — and was told not to expect funding for her first feature. "Just make it and see what happens."

She successfully turned to Kickstarter.com, adding $10,000 from her own pocket. Indie-film websites quickly spread buzz about the film, featuring Michole Briana White as Dr. Myes, researcher in the science of perception, and Jennifer Prediger '00 (see page 17) as Dr. Linda Wiley, her best friend and love interest. "After a near-death experience, Dr. Myes attempts to graft animal senses to the brain to revolutionize human consciousness. She must face the consequences when she uses her own body and mind as a research tool and transforms herself into a creature with super-senses," Nancy writes in an email.

This project has been her most challenging — and rewarding — yet. "It was my first time on a feature set, and I was the director. So I had a lot of learning to do." But while the film may be large, the budget isn't — requiring constant invention. "We're always asking ourselves, 'How do we make a film that looks interesting and beautiful with no money?' — but Dru as production designer and the whole team have done just that. It's challenging, but it makes you more creative."

152472_text.indd 14 11/3/14 11:44 PM

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE 15

Animation stills from The Strange Eyes of Dr. Myes, featuring Michole Briana White; animated by faculty member Nancy Andrews and SL Benz (Lauren Benzaquen '14).

152472_text.indd 15 11/3/14 11:44 PM

16 COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

Scores of people got involved, from Rohan Chitrakar '04 as director of photography, to COA

locations for free. "There are creative aspects to everything," Nancy says. "Take a scene: you may have it story-boarded out, but when you're working, the actors, the weather, the cars going by — whatever you have to deal with that day, you have to come up with creative solutions."

She learned that "the buck has to stop with the director, one has to make decisions constantly — do we have enough takes? If we spend more time on this scene, what will we not have time for? Is a lighting set-up 'good enough' so that shooting can begin, even if it's not perfect?" As with teaching, the quality of the outcome depends on leveraging collaboration. And enjoying it. "Having all of these skilled people around makes me like a superhero," she says. They give me new powers, powers that I don't possess." When she says that she wants to let "everyone do their job" on set, it's clear that

everyone.

"The editor and I will be working on transitions and one of us will have an idea, so I'll start drawing an animated transition, and we'll end up inserting little bits of animation into the

It's never stopped being inventive." This meant leaving behind the screenplay. "Something works on paper, but then some people watch it and say, 'I don't really believe this relationship.' So you go back to the cutting room and say, 'How can I put this together to make these relationships more believable?' At that point it really doesn't matter what's down on paper. What's happening on the screen has to be doing the job. It's about what I have, not what I wrote."

Referring to her usual, collage-like creative

looking at how it all works together. At some point during editing, that's what this process became, too." Hearing her, you get the sense that she's more comfortable without the map.

a trip we couldn't make without her.

Visit thestrangeeyesofdrmyes.com for a link to the trailer and more on The Strange Eyes of Dr. Myes.

152472_text.indd 16 11/3/14 11:44 PM

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE 17

Trouble Dolls

Trouble Dolls The Onion

Nerve BabbleWashington Post's

SprigGrist.org’s

Uncle Kent A TeacherStrange Eyes of Dr. Myes (see previous article

Trouble Dolls

Above: Movie still and publicity photo from of Jennifer Prediger '00 (left)

and Jess Weixler (right). Photos courtesy of Jennifer Prediger.

152472_text.indd 17 11/3/14 11:44 PM

18 COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

Creativity in Motion: Tawanda Chabikwa '07By Donna Gold, photographs by Craig Bortmas

In a cluttered studio in Columbus, Ohio, Tawanda Chabikwa '07 dances along a path of white paper. At the wall, cornered, he stops, but only momentarily. Soon he's upside-down, his weight on his head. The quiet Shona chant that has been playing is silenced and the dancer becomes another sort of creature, arms and legs moving along the wall, a noose-like black rope dangling ominously

near him. Returning to his feet, he climbs onto a wobbling pile of books and balances, unsteadily, then knocks the pile down and he's on the floor pushing the books with his head. Later, Tawanda returns to the white paper, crossing it on his knees and elbows like a penitent, then rising to dance jubilant before collapsing to the ground, almost writhing now. Several times he is back at the wall

and on his head — spinning the world, definitions, himself, upside-down.

The fifteen-minute performance of Digression in the Fourth Movement ends with Tawanda taking a brush and a pail of black paint, materializing his ephemeral gestures on the now-rumpled white paper, which he then rolls into and rises, dancing, the paper echoing the rolled-up skirts of African women. Shortly before the performance closes, the paper tears away and becomes a body Tawanda holds to him, then abandons, ending the dance with gestures intended to cleanse and move on.

With its piles of books, gestural painting, and references to Africa and acrobatics, with its unusual segues, turning movement on its head, this dance could be an autobiography. Tawanda first choreographed and performed it in 2012 in his homeland of Zimbabwe, when he briefly served as artistic director of Tumbuka, the premier Zimbabwean contemporary dance company. A consummate artist, Tawanda is devoted to exploring the currents that flow beneath our lives, the ones that bind us as humans. Stories and myths — whether from science, contemporary theory, or ancient mystics — nourish him, as does the gesture, the movement that illuminates being.

Tawanda dances, yes. He also writes, makes music, and paints. For his senior project at COA, he wrote the novel Baobabs in Heaven, which he later published (see Spring 2011), and choreographed and performed an evening of dance. He is now in a PhD program in dance studies at Ohio State University. But he continues to practice his arts — as well as "hiking and photographing, making videos, reading quantum physics, religious texts, The Economist, and the New Yorker, and spending time on Facebook and YouTube." These media feed him. Digression emerged from some writing

152472_text.indd 18 11/3/14 11:44 PM

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE 19

Tawanda had done. "This happens quite a lot — one medium sparks another, and they bounce back and forth until I find the greatest form for it." In this case, the dance completed Tawanda's prose.

For those of us who struggle with one expressive form, Tawanda's reach seems astounding. When I mention this over lunch in Bar Harbor during a summer visit to Maine, he laughs. "What is the paradox?" he asks. "Time?" I venture. "My mother asks the same question," he returns, and laughs again. Tawanda laughs a lot — possibly a means of deflecting the intensity of his thoughts. But when he dances, this slight, muscular man with dreadlocks falling in curls down his back is both breathtaking and serious: agile, delicate, precise.

"If I could, I'd do it all, all the time," Tawanda continues. "Painting with my toes, writing with my hands, wriggling with my heart." As he speaks, he places his hands in a circle in front of his chest and rocks them, as if rocking his heart, his being.

The longingTawanda's own story begins in Harare, Zimbabwe's capital, the second of four children. He describes his education as "little boys in grey and khaki uniforms, shorts, shirts and ties, hats, blazers, and socks pulled up to your neck." His earliest dance training was in ballroom style; his first accolades were primary school prizes for the Lindy hop and cha-cha. Summers imbued another legacy: learning the stories and dances of his Shona heritage around the communal fires of his ancestral village. These movements have since been joined by a multitude of others — from modern dance and rugby to capoeira and salsa. But his days in urban Harare and his ancestral enclave remain central. Though he left Zimbabwe at fifteen, heading to the Li Po Chun United World College in Hong Kong, and from there to COA, this heritage continues to inform his work.

Tawanda never expected to be immersed in the arts. At Li Po Chun he focused on science until one day he found himself walking by the art studio, looking longingly inside. Chrys Hill, the art teacher, called him in. "'Paints are expensive,'" Tawanda objected. "'It's in the budget,'" Chrys assured him, inviting him to use the studio at will. Soon after, "when life things were gathering in my mind," as he says, and he was wandering around campus hours after midnight, Tawanda found the lights on in the empty arts studio and lost himself inside. That was it. Chrys and his wife Anne became mentors and the couple, along with the art he was making and the dance he began to explore, helped him to understand the questions of a young Zimbabwean in a new world. "I haven't turned back since," says Tawanda.

What began in Hong Kong blossomed at COA where Tawanda studied with arts faculty members Dru Colbert

152472_text.indd 19 11/3/14 11:44 PM

20 COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

Photographer Craig Bortmas met Tawanda Chabikwa '07 at a performance in 2013. He says,"The stage was rich with visuals, Tawanda executed unnerving acts of athleticism (such as climbing a ladder upside down), and he succeeded in creating an amazing mess of the performance space. Quite memorable, to say the least."

For more of Craig's photos visit www.bortmasphoto.com.

152472_text.indd 20 11/3/14 11:44 PM

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE 21

and Nancy Andrews, with literature and film lecturer Colin Capers ’95, MPhil ’09, with creative writing faculty member Bill Carpenter, and dance with visiting teachers. Through math and physics faculty member Dave Feldman's Chaos and Fractals class he found a mathematical basis to his own observations that in seashells and African compounds alike, the whole echoes the part. Tawanda laughs again, "It might as well have been an art class. Dave doesn't know it — don't tell him that!"

Body knowledgeFor Tawanda, the many manifestations of creativity have but one origin: the body. Whatever its form, he sees all creativity as movement. The body is where mind, spirit, instinct, and heart reside. "Everything is body, it's common sense to me," he says. "The writing is alive in body, that's how it comes out, through the written gesture."

In seeking to understand the source of humans' urge toward art, part of Tawanda's PhD work is practice-based research, investigating his own creative process through an autoethnography that's centered in how cultural ideas are learned and carried within the body. "It's the actual movement itself that creates knowledge," he says. Dance, he writes, produces an internal intelligence that lives "at the intersection of multiple fields of knowledge — culture studies, technology, cognitive neuroscience, aesthetics, semiotics, politics, philosophy."

More specifically, Tawanda is looking at the global presence of Africanness as a way of understanding the place of cultural experience within our bodies. To that end, this multi-talented artist has segued into theory, reading everything from ancient African texts to psychoanalyst and revolutionary philosopher Frantz Fanon, dance historian Brenda Dixon Gottschild, African scholar Cheikh Anta Diop, and a range of third-world feminist theorists. "I am in school because reading — yes, deep, nerdy, intense,

verbose reading — inspires me, cultivates my mind, and cultivates my practice," he says.

In studying while doing, theorizing while making, does he fear that the analysis of creativity will disrupt the source of his art? Tawanda smiles, dispelling the question. "I won't steal from the magic of creativity by speaking its name — why not sing the ninety-nine names of Allah? Why be shy about it — it's only my longing to be a part of this creative flow." Definitions, he says, whether of creativity or the thing one creates, "are places we gather, not places that should put us apart."

Life as ritualThis is not a dispassionate quest. Tawanda seeks to understand how dance is transformative, regardless of the culture. He frequently works collaboratively, looking at both life and dance as ritual. "I've read that rather than performing rituals, most traditional African communities simply ritualize their life," he says. There's a mission driving this life-as-ritual. Some negative attitudes are being imbued as truth within our bodies, he adds, causing a separation between people and within people. His ultimate search is to "harness the healing powers of dance to cultivate more sustainable ways of being."

In Tawanda's dance Inheritance — Dunhu reMhondoro, which he created as part of his dance MFA from Dallas' Southern Methodist University, one performer lifts high above the others, circling the air suspended on a rope. Elsewhere on the stage, five other dancers, all dressed in white, seem to be reaching, searching, while the sounds first of birds, then of beasts emerge over calm, quiet music. Among the Shona people, says Tawanda, dunhu reMhondoro can be translated as the valley of the spirits. It's a phrase used to describe life's journey, which can be perceived as a passage through the wilderness. This journey may be dangerous, but there is protection. The spirits — one's ancestors — walk beside their

descendants, at times appearing as watchful, gentle lions. To Tawanda, this reflects the eternal cycle of life, a river of self that connects in all directions: to one's ancestors, to the as-yet-unborn, and outward, to one's family and community. "The tree would not grow if it did not long for the sun — and the water," he says. Longing, reaching, in all directions.

For many years, though he was on scholarship, Tawanda managed to support the education of as many as fifteen AIDS orphans in his ancestral village who otherwise couldn't go to school. The funds came from ticket and painting sales, and the help of friends. Using art for fundraising is tricky, but Tawanda recognizes few boundaries. "Perhaps because of a short attention span, I tend to think in multiple ways about a single thing and to want to know it. We could go philosophical, spiritual or new age with it, or just pure quantum physics: we are made of the same thing as stars, every single bit of us." Again, Tawanda gestures, one hand circling in front of him, and then both come together almost tenderly, shaping a sphere. "That makes me smile," he says.

As Tawanda works toward publishing his theories of creativity, he continues to pen a second novel, and to paint, make music, collaborate, and dance. "I choose dance because nothing escapes the body — what is more human ecological than dance?" he says, and then, "I want to dance until I disappear, because it isn't dance. At some point everything is shed and you can truly be with people, you feel like you've joined what Rumi calls the 'migration of intelligences' because you've cut the crap, and the tax payments, and the wars, and the jealousies, and fears. You're finally as you truly are meant to be, you just grow — creativity, vitality, life." To see Tawanda's dances and other work, visit ndiniwako.org.

152472_text.indd 21 11/3/14 11:45 PM

22 COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

Evolution, Creativity, and Art: A dialogueBill Carpenter, poet, novelist, and faculty member in literature and creative writing, and Helen Hess, faculty member in invertebrate zoology and biomechanics, discuss evolution as process and metaphor. This dialogue reflects an ongoing conversation on questions of human evolution among faculty members and others, held over dinners during the last few years.

Donna Gold: So, the question is why? Why did creativity, or better, art, evolve? Why is it a universal?

Bill Carpenter: I think the reason why art is a universal is that we needed it. As we emerged as humans we lost our instincts for behavior that would tell us what to do in any given situation. An oriole can make an amazing pendant nest; a hummingbird cannot. Yet a human being can choose to make any kind of nest and also a modern glass house or a wooden house or an earth mounded one. We have that choice because we no longer have the compulsion of instinct. That also gave us a space of freedom, which was unknown and scary and required our creativity to fill.

Helen Hess: I agree with you that the lack of hardwiring and the narrowness of an animal's repertoire is the other side of the coin of our flexibility. Flexibility and plasticity is one end

of a continuum. At the other end is completely hardwired and instinctual behavior. So something that's neurologically very tiny and simple and yet fairly behaviorally complex, like the honeybee, makes these hives and does these dances and has complex parental behavior — but it's all hardwired, while more and more of our behavior is learned through culture.

BC: Yes, we're hardwired for both the freedom and the necessity to create. God was the greatest of our creations, but we didn't stop there, our anxiety caused us to keep creating stories and images so we would understand who we were. Those with that understanding were more fit to carry on.

HH: I think I've got a contrasting perspective. I would say that art and creativity arose as a capacity in response

Phot

o by

Don

na G

old.

152472_text.indd 22 11/3/14 11:45 PM

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE 23

to other things that were directly selected for. We're very, very good at problem solving and that requires some creativity. So being creative problem-solvers, we developed this capacity to be creative in all kinds of ways. Problem solving required creativity; the creativity permitted art.

BC: And some of the problems were those of identity and existence, to answer those our problem-solving creativity took an artistic form —

HH: Yes. We were getting more cognitively complex, more aware of ourselves and our universe and why am I here and what happens after I die — well, guess what, in our ability to make art we have this capacity to address those scary questions. And creativity was absolutely needed — and art fulfills even more than that in terms of self-expression and understanding our relationship to each other and to our world. Otherwise how do we get out of bed in the morning? Here's a story that I heard fairly recently. There have been all these efforts to teach great apes how to communicate. Well, one gorilla, in communicating with his human handlers, came to recognize that he was going to die and when he died it was all over. He was an incredibly depressed gorilla. He couldn't get out of bed.

BC: Because we had given him our anxieties without giving him the creative means to resolve them. We should have given him a paintbrush or a piano.

HH: Right, so if art makes you feel better, you just do it and it's going to persist. But you want it to be more fundamentally selected for? BC: What might be selected is the power of art to bring group cohesion. The huge cultural bond of a rock concert for instance. Artistic achievement when it becomes public has the quality of erasing individual differences and binding the social group.

HH: I think the capacity for binding within a group is very much hardwired and universal.

BC: So what are those mechanisms? I'm trying to define creativity a little more tightly, and I would say in art it's specifically the ability to bind a group together, I'm considering art to be public performance, not just individual experience.

HH: That's a surprising characteristic coming from a poet!

BC: Well we all want an audience! I tell students that poetry thought in your head is not yet poetry. When poetry becomes understandable by the group, then it becomes very group binding. And we push and revise until it happens — because the need is not just an individual one, it's shared. I imagine that cave paintings weren't just for an individual's own contemplation but for the community. And some art has almost worldwide acceptance, giving hope that it might transcend competing subgroups and help unify us as a species.

HH: So I would say, the capacity to be creative is a human universal. The capacity to participate in a group and feel group cohesion is a human universal. But how that creativity and binding manifests is going to be dependent upon your culture and situation.

BC: Oh, I think that's right. And I think all creativity is probably modeled after evolution. It is only made incrementally, by small changes. With

the instruments of mutation and death, nature produced this amazing world before we even got here.

HH: I would say we are different because we can use our imaginations and invent something that's never been and we can do that intentionally. Nature can't do anything intentionally. Natural selection is a remodeler, not an architect, and humans are architects.

BC: But TS Eliot said that when you make a poem, you're not building from scratch, you're making a small mutative change to the body of poetry which exists — going back to the dawn of the written word — and you can only add a little bit. So, like evolution, each poem is a slight revision of a global and ongoing body of work.

HH: I can see that revision process being very much analogous to natural selection because natural selection is really good at sorting among all the options and choosing the best of what's available. For the poem, the poet makes what's available, and does the sorting and the judging of which is best among the alternative versions.

BC: Right, but the main thing is you have to be quite tough about killing off the prior forms and moving it forward.

HH: Ninety-nine percent of the species that have ever evolved have gone extinct.

BC: But for the artist, a lot of this takes place unconsciously. By the time you see what you think is a first draft — and this is what the mystery is to me — what process has it already been through? So human creativity and natural creativity follow the same pattern, with a lot of waste and death involved!

HH: So evolution is both a metaphor and an analogy of the creative process, and the driving force and the process that made our capacity as a species to be creative as possible. Interesting!

Creativity was absolutely needed.

… Otherwise how do we get out of bed in

the morning?Helen Hess

152472_text.indd 23 11/3/14 11:45 PM

24 COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

152472_text.indd 24 11/3/14 11:45 PM

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE 25

Seeking FormMiles Chapin '10

Miles Chapin '10 grew up on Maine's coast — its

for his high school senior project — science

Even while Miles was at COA, his work was

see page 9

commissions: he's creating a large sculpture for

— Donna Gold

"In my sculpture I use curves and texture to mimic motion and emotion. I carve directly, developing a relationship with the stone, playing with the inter-relationship form has with itself. When I start carving a block of stone, it feels as if it is static or asleep. Carving into each block pulls life into the stone, awakening the stone with each curve and angle. Each piece has its own passage to completion."

— Miles Chapin '10

, granite, 2013, 16"x16"x12"A model of the seven-foot piece Miles Chapin is sculpting for the new rail station in Brunswick, Maine, commissioned by the Brunswick Public Art Group. Three forms weave together in an arch, says Miles, creating an internal space that evokes a sense of place and belonging. Photo by Kyra Chapin '10.

152472_text.indd 25 11/3/14 11:45 PM

26 COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

Photo by Frances Buerkens.

Photo by Kyra Chapin '10.

152472_text.indd 26 11/3/14 11:45 PM

Left top: Flux granite, 2012, 13"x21"x10"

"Capturing movement, the granite seems to blow through the space, exploring perceived motion."

Bottom: Sojourngranite, 2013, 14.5"x20"x10"

"A single form on its own sojourn, weaving through space while creating multiple internal spaces."

Right: Euphoriagranite, 2014, 60"x22"x20"

"This is about passion and unity — two rings, appearing separate from one vantage point, come together to form a heart shape, recalling the euphoric feeling of romance. As the two rings meet they lift, suspended as one. It is open and meant to be looked through to its surroundings, creating a relationship."

For more of Miles' work, visit mileschapin.com.

Photo by Kyra Chapin '10.

152472_text.indd 27 11/3/14 11:45 PM

28 COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

NOVELBill Carpenter, faculty member Even a long project like a novel will often spring from an instantaneous moment. In the actual life of the writer an experience seems to resonate. Something becomes a point of focus, and crystallizes into a perception full of condensed feeling. You can think of the whole story in a moment — even a long novel. And often the point where the story started becomes very small in the novel, as the original breakthrough dissolves in the unfolding narrative. My theory is that what appears to be instantaneous is actually the result of a long unconscious process that opens to the writer as a flash of insight. The rest is the hard work of constructing it in time so others can understand. Time is the medium of exchange between writer and reader. You can compare it to the creation of a child — that lightning-like contact between the two creators, opening yourselves up to the unknown of another being. In writing too, you have a moment of connection with another being — your creative unconscious. It's a moment, there's no further contact, then it's a matter of changing diapers and paying tuition!

SCULPTUREMiles Chapin '10 (see page 26)I knew I wanted to use local granite for Nexus, the piece that was going

to the town of Calais, Maine. I found the stone in the woods near an old Calais quarry — I saw the shape and that it had been drilled, and I knew it was the one to use. It's connected to the land, and the quarry drillholes connect to Calais history. The design came from the outer shape of the rock — I often work that way now; I knew I wanted to work inside the stone, to have the open space from which to connect to the landscape. I see the shapes inside as representing the interconnectedness of Calais with St. Stephen, Canada. The opening creates a welcome from both directions; the curve on the inside of the stone mirroring the exterior. To carve the interior, I first read the exterior of the stone as carefully as I could for fractures, then I used diamond blades on an angle grinder, making a series of cuts to remove material before flush

cutting the final surface. After flush cutting each surface I re-examined the stone for cracks. The design was able to be as open as it is because there were so few cracks in this stone, which started at 8,500 pounds. It is now 5,450.

SONGCora Rose Lewicki '10There are stages to how things come about. There's the inspiration moment — something that has happened, some experience, something that is emotionally jarring, whether that's negative or positive, or something that happened to a friend, or in the world. What someone else might scream, or vent, or write in their diary, I turn into songs.

Stage two is using a lot of tools to structure a song, tools that have taken a number of years to build. It's having all the ingredients — chord structure, lyrics, melody — and asking, "How am I going to turn you into a song today?" I absolutely write lyrics first. I used to work the other way around — it was painful. It took me until I was twenty-three to realize that if I switched it, the sky opens wide! It's essential to find your pattern and what works best. So then I tinker with the musical elements until they start to fit the emotions, the first-stage part. I know it's right when it feels good, like when

Nexus, granite, 2014, 120"x60"x60."Photo by Alan Stubbs.

Creativity: The Paths Five members of the COA community reflect on their own creative process

152472_text.indd 28 11/3/14 11:45 PM

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE 29

you hear a three-part harmony and you get that "zing" feeling in your chest. So I'm tinkering, tinkering, tinkering — zing — I'm going to keep that part.

DANCETawanda Chabikwa '07 (see page 18)It usually starts off with a sensation, or a feeling that something needs to be done, to be created, in order to have more flow happen. It's very much a part of my ritualistic way of looking at life. My art is something like that. For example, the dance Tear Gas Anthem came from a time when South African communities were turning against immigrants. People were shot, raped, burned. That conflated with the images of Buddhist priests killing themselves, but reversed. These were Africans turning on Africans. But it's not always political news; sometimes it's just a vision. And then the ritual begins to take place, through time and memory and how these connect to the community. I don't know how else to put it — it spirals out of control or grows like a fractal. After that, it's more looking for and building bodies that not only can be vessels of the movement, but also be transformed by it at a personal level. I'm not making a dance on people, it's collaborative. For me art is part of a much greater ritual of things that I deeply feel need to be expressed

for whatever reason. Isn't everyone's art just them trying to understand themselves better — or just trying to understand?

DRAWINGVictoria Alexis Gancayco '17Art is my mediator for difficult-to-express ideas and facts such as time/space, living/dying. Recently, an experience relating to the death of a close friend has made me think about how fragile, impermanent our lives are; that we must tell the ones we love how much they mean to us while we still can. Over the summer, an image of the heart began replaying in my

mind. I started to draw this image, my heart, your heart, our hearts. Eventually, as I continued to draw, each line and curve became automatic to my mind and hand. I constructed a foldup/foldout accordion volume containing the hearts across strips of paper sewn together. The process of drawing each heart became a meditation in itself. I found this experience needed to be shared. My intent of the piece is for the viewer to engage with images of the heart, contemplatively — a meditation about what it means to be alive, to slow down and feel every second of every beat.

Cora Rose Lewicki '10 performs her "Turn the World" concert at Gates Community Center in 2009. Photo by Jordan Motzkin '13.

152472_text.indd 29 11/3/14 11:45 PM

30 COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

The RestaurantPopping up delicaciesBy Eloise Schultz '16Photos by Becca Haydu '16

Two salads, said Bronwyn. One soup. …

152472_text.indd 30 11/3/14 11:45 PM

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE 31

with Labrador tea from Sunken Heath, a bog at the center of Mount Desert Island.

The Restaurant (also known as the Coop Coöp) has been an annual, student-organized event since its conception in 2012. In those two years it has served more than five hundred members of the COA community and raised over four thousand dollars to support Share the Harvest, a program run through Beech Hill Farm that provides access to fresh organic produce for those receiving SNAP and WIC benefits ([email protected]). The goal of the Restaurant is to provide full, whole nourishment to both volunteers and guests. Whether you come to taste the food or to lend a hand at washing dishes, serving tables, playing music, or preparing and plating food, you are welcome at the Restaurant.

In a 2012 documentary made by Devin Altobello '13 about the Restaurant (devinaltobello.com), Lally Owen '14 commented, it's about "eating not just to eat, but more consciously feeding yourself and other people. Kind of the idea of being held by something that you make, or holding other people and giving that way." The Restaurant serves as a community catalyst: an opportunity to connect over food, support each other's passions and projects, and celebrate our work together.

Students, staff, faculty, and community members work together to create the event, which has a different locale each time. In the weeks before, emails fly back and forth regarding farm culls, foraging excursions, and closets stacked with jars of kombucha and yogurt. In the morning, an off-campus student residence is cleaned and prepared to seat up to sixty guests at a time. The afternoon is spent gathering tables and chairs, while several kitchens across Bar Harbor are orchestrated to the tune of boiling stock pots, chopping produce, rolling pasta dough, and melting chocolate.

The work that goes into the Restaurant itself is hard to quantify. When spending hours juggling hats (in some cases, literally), one's periphery turns into a blur of food, flushed faces, and the tangled sounds of music and conversation. "After sixteen hours of work in those two days, we were so beat that it felt like our feet had turned to pulp," said Nicole. "Addie came out to the couch in the front yard with a fishbox full of warm water and lavender. When we put our feet in that box we all made the same face, which is probably too inappropriate to describe."