English posters2015

-

Upload

camila-garcia -

Category

Documents

-

view

81 -

download

0

Transcript of English posters2015

www.postersession.com

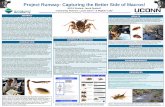

Birth and Family

Born March 17, 1912 in West Chester, Pennsylvania, to Florence Rustin and Archie Hopkins, Bayard Taylor Rustin was one of the most effective and fearless, though frequently overlooked, organizers in the civil rights movement.[3] He was raised by his maternal grandparents whom he believed were his parents.[3] It was not until Bayard was eleven that he discovered that Florence Rustin was his mother, not his sister, and that his “parents” , Janifer Rustin and Julia Rustin, were in fact his grandparents. Regardless, Janifer and Julia Rustin had a deep and abiding influence on their grandson who enjoyed a more comfortable family life than his complicated origins might seem.[5] His grandmother Julia Rustin was a Quaker deeply enrooted in the belief of pacifism and racial equality. This had a lasting effect on Bayard who remained a Quaker and fought for racial equality throughout his life. As an active member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Mrs. Rustin hosted leaders such as W.E.B. Du Bois and James Weldon Johnson when they toured in the West Chester area as guests in the Rustin home. Having these Political leaders in his early life influenced the young Rustin to campaign against racially discriminatory Jim Crow laws.[3]

Accomplishments, Awards,

and Recognition

Bayard Rustin: Civil Rights Activist

References

became an important strategist in the Civil Rights Movement. This then lead to him being the chief organizer of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

1. Dubofsky, Melvyn. "Rustin, Bayard." American National Biography Online. and Mark C. Carnes. , John A. GarratyNew York: Oxford UP, 2008. Oxford African American Studies Center. n.d. Web 1 Jul 2015.

2. Levine, Daniel. Bayard Rustin And The Civil Rights Movement. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2000. eBook Collection (EBSCOhost). Web. 1 July 2015

3. Cook, Charles Orson. "Rustin, Bayard." Encyclopedia of African American History, 1896 to the Present: From the Age of Segregation to the Twenty-first Century. Ed. Paul FinkelmanNew York: Oxford UP, 2008. Oxford African American Studies Center. n.d. Web 5 July 2015.

4. "[Bayard Rustin, Head-and-shoulders Portrait, Facing Right]." The Library of Congress. n.d. Web. 5 July 2015.

5. Niven, Steven J.. "Rustin, Bayard Taylor." African American National Biography. Ed. Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham. New York: Oxford UP, 2008. Oxford African American Studies Center. n.d. Web. 5 July 2015.

6. "Rustin, Bayard." Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience, Second Edition. Ed. Kwame Anthony Appiah, Henry Louis Gates Jr.New York: Oxford UP, 2008. Oxford African American Studies Center. n.d. Web. 5 July 2015.

7. Tuttle, Kate. "March on Washington, 1963." Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience, Second Edition. Ed. Kwame Anthony Appiah and Henry Louis Gates Jr.. New York: Oxford UP, 2008. Oxford African American Studies Center. n.d. Web. 5 July 2015.

Rustin died on August 24, 1987, of a perforated appendix. Despite the fact that he played such an important role in the civil rights movement, Rustin "faded from the shortlist of well-known civil rights lions," in part because of public discomfort with his sexual orientation..

LegacyEarly Life

Involvement

Rustin was a leading activist of the Civil Rights Movement, helping to initiate a 1947 Freedom Ride to challenge the racial segregation issue related to interstate busing.[6] Alongside Martin Luther King, Jr.'s leadership, Rustin helped organize the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. By promoting the philosophy of nonviolence Rustin

•Accomplishments, Awards and Recognition

•Personal LifeI.Marriage/Family InvolvementII.ChildrenIII.Personal Hobbies

Influence on the Civil Rights Movement

Most Memorable Achievement(s)

Rustin's involvements in the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), a radical pacifist movement, lead him to the establishment of the New York branch of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). Throughout the 1940s and 1950s he led weekend seminars on nonviolent action for both groups.[6]Bayard also helped organize the Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1955, and was involved in the formation of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC).[6]

Posthumous Awards

In 2013, President Barack Obama awarded Rustin a posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom. This award is given to individuals who have a made particularly significant contributions in any variety of endeavors.[5]

Bayard Rustin, 1963. Photograph by Warren K. Leffler.[1]

Bayard Rustin. Rustin (left) with Eugene Reed at a news briefing on the civil rights march, Washington, D.C., 1963. Photograph by Al Ravenna.[3]

Rustin and Cleveland Robinson of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 7, 1963

Rustin speaks with civil rights activists before a demonstration, 1964

Figure 1 Bayard Rustin, head-and-shoulders portrait, facing right.[4]

Education

As a member of his high school football team while attending public school, Rustin first challenged racial segregation when he and a friend demanded to be served after denied service in a segregated restaurant. He attended the historically black Wilberforce University and Cheyney State Teachers College, then in 1937 enrolling in the City College of New York. Although he never completed a college degree he became addicted to the New York culture finding it exhilarating and considered a career in musical theater.

The March on Washington served as a springboard for the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act, marking the high point of unity in the civil rights movement.[5] Rustin served as the coordinator of the March on Washington which had 200,000 people who attended. Rustin was arrested twenty-three times, but he continued to believe that racial equality should be pursued through nonviolent means.[6]

Rustin 1965

March on Washington