Endndes i rt (ChcerDi si ) ecisi s - Family La v Grangeglen.pdf · ces "sˆell ashe tsf lecti it...

Transcript of Endndes i rt (ChcerDi si ) ecisi s - Family La v Grangeglen.pdf · ces "sˆell ashe tsf lecti it...

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

England and Wales High Court

(Chancery Division) Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> England and Wales High Court (Chancery Division) Decisions >> Pineport

Ltd v Grangeglen Ltd [2016] EWHC 1318 (Ch) (13 June 2016)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2016/1318.html

Cite as: [2016] EWHC 1318 (Ch)

[New search] [Printable RTF version] [Help]

Neutral Citation Number: [2016] EWHC 1318 (Ch)

Case No: HC-2015-004127

IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE

CHANCERY DIVISION

Royal Courts of Justice

Strand, London, WC2A 2LL

13/06/2016

B e f o r e :

CHIEF MASTER MARSH

____________________

Between:

Pineport Limited Claimant

- and -

Grangeglen Limited Defendant

____________________

Mr Robert Bowker (instructed by Surjj Legal Ltd) for the Claimant

Mr Jamal Demachkie (instructed by Blaser Mills LLP) for the Defendant

Hearing dates: 6 and 7 April 2016

____________________

HTML VERSION OF JUDGMENT

____________________

Crown Copyright ©

Chief Master Marsh:

1. This claim concerns the Claimant's application for relief against forfeiture of an underlease

of Unit 4, Endsleigh Industrial Estate, Endsleigh Road, Southall, Middlesex UB2 5QR

("Unit 4"). The underlease which is dated 20 July 1998 was granted to the Claimant for a

term of 125 years, less 10 days, from 6 April 1981 for a premium of £90,000. It is agreed

Page 1 of 18Pineport Ltd v Grangeglen Ltd [2016] EWHC 1318 (Ch) (13 June 2016)

01/07/2016http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2016/1318.html

that the current value of the leasehold interest is £275,000 in its actual condition and

£300,000 if Unit 6 were put into full repair. The reversionary interest expectant upon the

termination of the lease became vested in the Defendant in about March 2011. The

underlease includes a right of re-entry in the event of non-payment of rent for a period of 21

days, whether formally demanded or not (Clause 6(1)). The rent payable pursuant to the

underlease comprises three elements:

i. ground rent of £100 per annum;

ii. a sum equivalent to the amount expended by the landlord in insuring Unit 4;

iii. a service charge as defined in clause 4(7).

2. The landlord's expenditure which falls within the service charge is widely defined and

includes all the expenditure falling within the definition of "Management Services" as well

as the costs of collection and audit and the creation of a reserve. The Claimant was obliged

to pay:

i. A quarterly advance payment of an amount considered to be fair and

reasonable by the landlord.

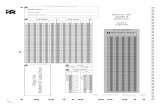

ii. A balancing payment in respect of the sum shown to be due by the account

produced by the landlord supported by a certificate of the landlord or the

landlord's managing agent produced as soon as reasonably practicable after the

end of the service charge year. Clause 4(7)(b) makes provision for the

information to be provided with the certificate. In the event that the tenant has

overpaid for the service charge year, the overpayment is held by the landlord as

a credit against the following year's service charge.

3. The only other clauses of the underlease which are material are clauses 4(12) and 4(13)

concerning user. The use of Unit 4 was restricted to any use falling within Use Class III of

the Town and Country Planning (Use Classes) Order 1972. The tenant covenanted not to

use the premises for any illegal or immoral act or purpose. Unit 4 has been used as an MOT

garage and workshop.

4. On 24 April 2014 the Defendant forfeited the underlease by peaceable re-entry based upon

unpaid rent. However, this claim seeking relief against forfeiture was not issued until 23

June 2015. The claim was transferred to the County Court at an early stage but then

transferred back on the basis that the County Court does not have jurisdiction to grant relief

in the circumstances which have arisen. A case management conference was held on 25

November 2015 at which it was allocated to the case management and trial by Master

management track. It came on for trial before me on 6 and 7 April 2016. The only other

aspects of the order for directions made on 25 November 2015 which are worthy of mention

are that:

i. An order for disclosure was made in accordance with CPR 31.5(7)(b),

requiring the parties to serve the documents upon which they relied by 16

December 2015 with requests for specific disclosure and response by fixed

dates. There was no order for standard disclosure.

ii. Witness statements were ordered to be exchanged by 29 January 2016.

The parties

Page 2 of 18Pineport Ltd v Grangeglen Ltd [2016] EWHC 1318 (Ch) (13 June 2016)

01/07/2016http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2016/1318.html

5. The Claimant was incorporated on 3 March 1998 and operated its main business of

providing MOT and garage services from Unit 4 until the underlease was forfeited. It has

two directors, Mr Shorab Jadunandan and Mr Sajjad Ahmad, who are equal shareholders. In

recent years Mr Ahmad has had no involvement with the running of the company and the

business has been under the control of Mr Shorab Jadunandan. An underlease of Unit 11 on

the same estate was purchased by the Claimant at the same time as Unit 4 but was sold a

few years later. The company also holds an underlease of Unit 5 which has not been

forfeited. The abbreviated balance sheet for the Claimant as at 31 March 2014 shows a

negative balance of £24,022.

6. A restraint order was made against both the Claimant and Mr Shorab Jadunandan by a judge

in Isleworth Crown Court on 2 August 2013 upon the application of the Vehicle & Operator

Services Agency ("VOSA"). The order was made in extremely wide terms and included a

prohibition against Mr Shorab Jadunandan disposing of, dealing with or diminishing the

value of any of the assets the Claimant. It also prohibited any third party from "knowingly

to assist in or permit a breach" of the order. No point was taken during the trial about

whether the act of re-entry may have been a breach of the restraint order, or placed the

Defendant at risk of contempt proceedings, although it is the Claimant's case that the

Defendant was made aware of the order.

7. The prosecution was based upon the issue of MOT certificates by Mr Shorab Janunadan,

and others, without the correct procedure being followed. The prosecution's case was that

over 1,400 such MOT certificates had been issued; in some cases the certificate was issued

without the vehicle being examined and in other cases following examination by a person

who was not authorised. In any event, Mr Shorab Janunandan pleaded guilty on 23 April

2014 to two counts of conspiring dishonestly to make a false representation to make a gain.

On 2 March 2015 he pleaded guilty to four further counts of dishonestly making a false

representation to make a gain. His sentencing hearing was deferred and on 7 March 2016

Mr Shorab Janundandan was sentenced to a term of imprisonment of 18 months. When he

gave evidence at the trial before me he was a serving prisoner. It is right to say, however,

that Mr Shorab Jadunandian does not accept the prosecution case about the scope of his

dishonest activity. He says that the prosecution extrapolated from a very limited review of

test certificates issued and has come up with an estimated number of incorrect certificates

which is far too large. Mr Jadundanian puts the number of vehicles which were given MOT

certificates without tests having been undertaken at between 10 and 15. He accepted,

however, that there were other irregularities concerning the manner in which MOT

certificates were issued.

8. The Defendant is a property holding company. One of its directors, Mr Andrew Butler, is

also head of the Uxbridge office of Colliers International which acted as managing agents

for the estate.

Statements of case

9. The claim is made in straightforward terms. Although the Claimant reserved its position

concerning the lawfulness of the re-entry there is now no challenge to it. The claim has

proceeded on the basis that at the time of re-entry there were arrears of rent (in fact service

charges) amounting to £2,155. In passing, I mention that a notice under s.146 of the Law of

Property Act 1925 was served on 3 April 2014 although such a notice is not required in the

case of unpaid rent. The claim merely asserts that the Claimant was ready willing and able

to pay the arrears of service charges and seeks relief from forfeiture under the court's

equitable jurisdiction on such terms as the court thinks fit, just and equitable.

Page 3 of 18Pineport Ltd v Grangeglen Ltd [2016] EWHC 1318 (Ch) (13 June 2016)

01/07/2016http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2016/1318.html

10. The defence was settled by leading counsel, Mr Jonathan Karas QC. The Defendant relies

on the delay on the part of the Claimant in making the claim for relief and the absence of an

explanation for that delay. The claim for relief is described as being stale. In addition the

Defendant relies upon the following points:

i. Prior to forfeiting the underlease the Defendant made repeated attempts to

contact the Claimant to ascertain why the arrears had not been paid and to

require payment.

ii On 8 August 2014 the Claimant's solicitors acting in the criminal

proceedings, Makwanas, contacted the Defendant's solicitors and said a

freezing order had been made against the Claimant. However, there was no

follow up to that conversation.

iii. It was not until 12 June 2015 that the Claimant's current solicitors made

contact and said an application for relief was to be made.

iv. The Defendant has incurred costs and expenses since the date of re-entry

and the costs and expenses have increased by virtue of the delay. They are

described as falling into four general categories namely (a) management,

insurance and security, (b) dealing with vehicles found at Unit 4, (c) business

rates and (d) preparing an application to the Land Registry to vacate reference

to the underlease from the Defendant's title. The costs and expenses are

particularised in a schedule served with the defence.

v. In addition, it is said that the Defendant has been prejudiced by the delay on

the part of the Claimant in making the application for relief. The claim to

prejudice is based upon the increase in costs and expenses incurred by the

Defendant resulting from the delay.

vi. In the alternative, the Defendant requires payment of all sums which would

have fallen due for payment had the lease continued and an indemnity for all

costs and expense the Defendant has incurred.

11. In its reply the Claimant says at paragraph 3 that the Defendant "… did not at any time prior

to re-entering the premises demand any alleged arrears, indicate its intention to forfeit, enter

into dialogue with the Claimant regarding alleged arrears, or pursue pre-action

correspondence". The Claimant goes on to say in the following paragraph that its solicitors

hold £2,155 on their client account and that the Claimant was ready and willing to pay that

amount into court if directed to do so. The Claimant's case for the grant of relief is fleshed

out in paragraph 8:

"8. …. Matters of fact and evidence in seeking to persuade the court to exercise

its discretion shall be provided in witness evidence. For completeness, the

Claimant is entitled to relief from forfeiture on the following basis:

a. On 7 August 2013 the Claimant and its sole director Mr Shorab Jadunandian

were served with a Restraint Order freezing the Claimant's assets ("the Order")

and causing some financial hardship to the Claimant and access to funds. The

Order was made in separate criminal proceedings against Mr Shorab

Jadunandian.

b. Despite financial hardship the Claimant took steps to mitigate arrears by

subletting Unit 4 ….. ("the Property") to Adil Yusek t/a A.K. Motors on 5

Page 4 of 18Pineport Ltd v Grangeglen Ltd [2016] EWHC 1318 (Ch) (13 June 2016)

01/07/2016http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2016/1318.html

October 2013. The Claimant also holds the leasehold interest in Unit 5 …. next

to the Property which is sublet to Zeus Security and Electrical Limited.

c. The claimant did however fall into service charge arrears for the Property and

Unit 5 … On or about 25 March 2014, the Defendant instructed bailiffs to

attend Unit 5 and collect arrears from the Claimant. The Claimant informed the

bailiffs of the order and provided them with a copy. The Claimant made clear

that whilst there was an order in place it was willing to make payment of all

arrears and the bailiffs telephoned the Defendant's solicitors on site during the

visit. Between the period of 25 March 2014 and 13 May 2014 the Claimant

paid approximately £4,807.84 in rent arrears which it believed would be

apportioned between Unit 4 and Unit 5.

d. However, on 24 April 2014 the Defendant peaceably re-entered the Property

without any notice to the Claimant. The Claimant put the Defendant to strict

proof of its "repeated attempts to contact the Claimant to ascertain why

payment of arrears had not been paid", as set out in paragraph 8(2)(a). The

Defendant was aware of the Order and the Claimant's circumstances at the time

of forfeiture. Paragraph 3 of the Reply above is repeated.

e. The Claimant was contacted by Mr Adil Yusef t/a A.K. Motors to whom the

Property had been sublet on 24 April 2014 and both the Claimant and Mr Adil

Yusef contacted the Defendant's solicitors informing them that they were

willing to make payment of the arrears. The Claimant has from the outset

expressly set out its intention to seek relief from forfeiture.

f. Due to Mr Jadunandian's ill health and state of mind the Claimant delayed in

seeking legal advice and making its application for relief from forfeiture. Mr

Jadunandian as the sole director of the Claimant was diagnosed with depression

in or around 10 March 2014. During the immediate period after forfeiture took

place Mr Jadunandian struggled to face reality and was unable to engage in day

to day activity. Due to the stress and anxiety caused by criminal proceedings

against him, Mr Jadunandian continues to suffer from depression and has been

prescribed antidepressants."

The jurisdiction to grant relief and the relevant principles

12. I am grateful to both counsel for their helpful submissions on the law. The principles are

summarised in Chapter 17 of Woodfall on Landlord and Tenant and the references which

follow are to paragraph numbers in that chapter. It is helpful in a number of instances to

refer to the underlying authorities.

13. Where a landlord has lawfully peaceably re-entered, as opposed to forfeiting a lease by

pursuing proceedings, the High Court has power in equity, independently of statute, to grant

relief. This principle is stated unequivocally at paragraph 17.188 and with a degree of

equivocality at paragraph 17.185 ("It seems the court also has power to grant relief under its

inherent jurisdiction …"). However, the position is made plain by the Court of Appeal's

approval of Howard v Fanshawe [1895] 2 Ch 581 in Lovelock v Margo [1963] 2 QB 787

and the decision of the Court of Appeal in Billson v Residential Apartments [1992] 3 WLR

264 (that decision being unaffected by reversal on a different point).

"In summary, the basic jurisdiction to relieve from forfeiture for non-payment

of rent is the old equitable jurisdiction; that equitable jurisdiction (and the

statutory application thereof in the county courts) is subject to a separate code

Page 5 of 18Pineport Ltd v Grangeglen Ltd [2016] EWHC 1318 (Ch) (13 June 2016)

01/07/2016http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2016/1318.html

of statutory provisions modifying and limiting the equitable jurisdiction in

certain respects, particularly in relation to time; however the old equitable

jurisdiction to relieve, without limit of time, continues to apply where there has

been a forfeiture by peaceable re-entry." Per Nicholls LJ

14. Paragraph 17.185 adds the proviso, which is repeated elsewhere in Chapter 17, that the

landlord is to be paid in full the arrears of rent and the cost of recovering those arrears. I will

return to the question of what constitutes the cost of recovery as opposed to the costs of the

claim.

15. The equitable jurisdiction to grant relief from forfeiture arising from court proceedings was

restricted by the Landlord and Tenant Act 1730 to an application made within a period of 6

months after the execution of judgment for possession. This provision was re-enacted in

Section 210 of the Common Law Procedure Act 1852. However, those provisions relate

only to forfeiture arising from proceedings and have no direct application in the case of

peaceable re-entry. The position is summarised in Woodfall in the following way at 17.188:

"For the purposes of [the equitable jurisdiction], the six months' limitation

period under the Common Law Procedure Act does not apply; but the six

month period will be taken as a guide rather than as a strict limit."

It is also pointed out at paragraph 17.187 that it may be inequitable to grant relief under the

1852 Act within the six month period. Thus, the 1852 Act does not operate in a similar way

to the Limitation Act which provides fixed periods with a bar to recovery only in the event

of a claim being issued outside that period.

16. In this case the application for relief was issued some 14 months after re-entry. There is

only limited help from the authorities concerning whether the equitable jurisdiction may be

exercised to grant relief in response to an application made so far outside a period which is

to be taken as a guide rather than a final cut-off date. The issue was considered by Sir

Jocelyn Simon P in Thatcher v C. H. Pearce & Sons (Contractors) Ltd [1968] 1 WLR 748.

In that case the landlord peaceably re-entered on 4 July 1964 for non-payment of the

quarter's rent due on 24 June 1964. The application was issued on 8 January 1965, just six

months and four days after re-entry. The Claimant was in prison during the relevant period

and the judge accepted that he did all he could to deal with seeking relief in the

circumstances but was hampered by being 'inops consilii' for a period. The judge granted

relief and in doing so made the following observations:

"As I understand the old equitable doctrine, the court would not grant relief in

respect of stale claims. Furthermore, if there were a statute of limitation

applying at common law, equity followed the law and applied the statute to

strictly analogous proceedings in Chancery. But there is no question in the

instant case of a Limitation Act applying to the present situation; and it seems

to me to be contrary to the whole sprit of equity to boggle at a matter of days,

which is all that we are concerned with here, when justice indicates relief.

I think that a court of equity … would look at the situation of the plaintiff to see

whether in all the circumstances he acted with reasonable promptitude.

Naturally it would also look at the situation of the defendants to see if anything

has happened, particularly by way of delay on the part of the plaintiff which

would cause a greater hardship to them by the extension of the relief sought

than by its denial to the plaintiff."

17. The six month period was also considered by Nicholls LJ in the Court of Appeal in Billson:

Page 6 of 18Pineport Ltd v Grangeglen Ltd [2016] EWHC 1318 (Ch) (13 June 2016)

01/07/2016http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2016/1318.html

"Equity follows the law. This is not to say that courts of equity should now

grant relief without any regard to the statutory provisions. Equity follows the

law, but not slavishly nor always: see Cardozo C.J. in Graf v. Hope Building

Corporation (1930) 254 N.Y. 1, 9. On this we have the benefit of guidance

elsewhere in the field of relief from forfeiture. Section 210 of the Common Law

Procedure Act 1852, which is still in force, limited to six months after judgment

the period within which a tenant could apply for relief in the non-payment of

rent cases to which that statute applied, viz., where the rent was six months in

arrears. Courts of equity have due regard to this statutory limitation in non-

payment of rent cases where the statute does not apply: in cases of forfeiture by

peaceable re-entry, and in cases where possession has been taken under a court

order where less than six months' rent was in arrears. In Howard v. Fanshawe

[1895] 2 Ch. 581, the landlord re-entered without the aid of the court. Stirling J.

said, at pp. 588-589:

"it does not follow that a court of equity would now grant relief at

any distance of time from the happening of the event which gave

rise to it. It appears to me that, inasmuch as the inconvenience of

so doing has been recognised by the legislature, and a time has

been fixed after which, in a case of ejectment, no proceedings for

relief can be taken, a similar period might well be fixed, by

analogy, within which an application for general relief in equity

must be made. A court of equity might possibly say that the action

for relief must be brought within six months from the resumption

of possession by the lessor."

18. Nicholls LJ went on to say, having considered the decision in Thatcher:

"The concurrent equitable jurisdiction can only be invoked by those who apply

with reasonable promptitude. What is reasonable will depend on all the

circumstances, having due regard to the statutory time limits."

19. Plainly, in this case where the application was made 14 months after re-entry, the Claimant

has a significant obstacle to overcome whether the court has "due regard" to the six month

period under the 1852 Act or the period is taken as a guide. It is not that the court is unable,

as a matter of jurisdiction, to grant relief where an application is made some considerable

time outside the six month period but rather whether the court should exercise its

jurisdiction to do so. The issue of "reasonable promptitude" necessarily involves

consideration of the reasons for the delay by the Claimant; it also may involve considering

those reasons in the overall context as what is reasonable may vary depending on that

context.

20. The general principles which apply to applications for relief in the case on non-payment of

rent are explained in paragraph 17.181:

"In the eyes of equity, the proviso for re-entry was merely a "security" for the

rent. Equity is in the "constant course" of relieving against forfeiture where the

tenant pays the rent and all expenses. Thus save in exceptional circumstances

the function of the court is to grant relief when all that is due for rent and costs

has been paid up. The same applies where the breach for which forfeiture has

occurred is non-payment of sums analogous to rent such as service charges.

The fact that the tenant is insolvent does not make any difference; if he pays the

rent in arrear, interest and costs, he is normally entitled to relief."

Page 7 of 18Pineport Ltd v Grangeglen Ltd [2016] EWHC 1318 (Ch) (13 June 2016)

01/07/2016http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2016/1318.html

21. Mr Demachkie draws assistance from the approach adopted by Lewison J in Vision Golf v

Weightmans [2005] EWHC 1675 (Ch). In that case solicitors failed to apply for relief

against forfeiture within 6 months. Referring to Thatcher the judge observed that "a few

days is not a few weeks" and without deciding whether the tenant would not have been

succeeded on an application for relief from forfeiture, concluded that the right to relief had

been substantially damaged or devalued by the solicitors' breach of duty. Mr Demachkie

submits that I should conclude from the approach adopted by Lewison J that an application

for relief made 14 months after re-entry should not succeed. However, the way the court

deals with a late application for relief will depend upon the facts of the case and Lewison J

did not find that the tenant's application was bound to fail.

22. When considering an application for relief in relation to forfeiture for non-payment of rent

the court should not take account of other breaches of covenant save in exceptional

circumstances (paragraph 17.182). One such circumstance is where the breach is extremely

serious. However, the taking account of such a breach does not necessarily lead to relief

being refused. It may be a factor but in the exercise of the equitable jurisdiction all the

circumstances will be considered, including the starting point that the court leans heavily in

favour of granting relief. An example of where the court considered another breach of

covenant but decided that it was not relevant is Gill v Lewis [1956] 2 QB 1 (a decision made

under s212 of the 1852 Act). A tenancy of two dwelling houses had been granted to the

Defendants as joint lessees. Forfeiture proceedings were pursued for non-payment of rent.

One of the Defendants had been convicted of indecent assaults on boys in one of the houses.

In a well-known passage, Jenkins LJ sets out the general approach to the grant of relief for

non-payment of rent and goes on to consider in what circumstances that approach may not

apply [p13 to 14]:

"… save in exceptional circumstances, the function of the court in exercising

this equitable jurisdiction is to grant relief when all that is due for rent and costs

has been paid up, and (in general) to disregard any other causes of complaint

that the landlord may have against the tenant. The question is whether, provided

all is paid up, the landlord will not have been fully compensated; and the view

taken by the court is that if he gets the whole of his rent and costs, then he has

got all he is entitled to so far as rent is concerned, and extraneous matters of

breach of covenant, and so forth, are, generally speaking, irrelevant.

But there may be very exceptional cases in which the conduct of the tenant has

been such as, in effect, to disqualify them from coming to the court and

claiming any relief or assistance whatever. The kind of case I have in mind is

that of a tenant falling into arrear with the rent of premises which he was

notoriously using as a disorderly house: it seems to me that in a case of that sort

…. the court, on being apprised that the premises were being consistently used

for immoral purposes, would decline to give the tenant any relief or assistance

which would in any way further his use or allow the continuance of his use of

the house for those immoral purposes. In a case of that sort it seems to me that

it might well be going too far to say that the court must disregard the immoral

user of the premises and assist the guilty tenant by granting him relief.

I cannot, however, find any facts in the present case approaching the

exceptional state of affairs I have in mind."

23. In applying the principles to the facts of the case, Jenkins LJ went on to note that the

conviction related to one isolated incident against one of the tenants which took place at one

of the two houses.

Page 8 of 18Pineport Ltd v Grangeglen Ltd [2016] EWHC 1318 (Ch) (13 June 2016)

01/07/2016http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2016/1318.html

24. It seems to me that a significant factor for the court in deciding whether there are

exceptional circumstances is whether the grant of relief may have the effect of assisting the

tenant to continue a breach of covenant. If the breach is past and unlikely to continue, even

a serious breach may not be sufficient to permit the court to decline to grant relief. I accept,

however, that in some circumstances, a landlord might be able to provide evidence of the

reversionary interest having been damaged by an historic breach of covenant such that the

breach could be a material factor in refusing to grant relief.

25. It was suggested by Mr Demachkie during submissions that the maxim 'He who comes to

equity must come with clean hands' may be of general application and that Mr Shorab

Jadunandan's conviction might be relevant to the grant of relief. However, it does not seem

to me that resorting to an equitable maxim is a helpful approach to the exercise of a

jurisdiction which has a long history and a well developed jurisprudence. I consider that the

approach explained by Jenkins LJ in Gill v Lewis, which takes account of the longstanding

approach to the grant of relief for non-payment of rent, is the right one.

26. The final general consideration concerns the conditions upon which relief should be

granted. The principle is explained at paragraph 17.180:

"It is an invariable condition of relief from forfeiture for non-payment of rent

that the arrears, if not already available to the lessor, shall be paid within a time

specified by the court. If the tenant cannot pay the arrears relief may be refused.

It appears there must be evidence before the Court that the rent will definitely

be paid rather than that it may be repayable in the future and that there is no

discretion otherwise to grant relief. The tenant will normally also have to pay

the landlord's costs.

The landlord is not bound to accept tender of the arrears from a third party."

27. It is not merely the arrears which must be paid, but also any other expenses or loss sustained

by the landlord in light of the forfeiture. As Arden J said in Inntrepreneur Pub Co (CPC)

Ltd v. Langton [2000] 1 EGLR 34:

"The principle which underlies the exercise of the court's discretion is that

provided the lessor can be put in the same position as before, the lessee is

entitled to be relieved against the forfeiture on payment of the rent and any

expenses to which the lessor has been put, prima facie the lessor is entitled to

be put into the position he would have been in if the forfeiture had not occurred.

This principle has often been endorsed by the Court of Appeal."

28. As for the time for payment, Inntrepreneur v Langton again provides assistance:

"The period fixed for the payment of arrears must be one within the

immediately foreseeable future, so that the court can say with a sufficient

degree of certainty that the rent outstanding will be paid. Even then, the tenant

has no right to relief. The court may decline to grant relief if, for example, the

landlord has changed his position before the tenant makes an application for

relief (see Gill v Lewis [1956] 2 QB 1) because there has been excessive delay

in making the application for relief… there has to be evidence that [the tenant]

will be able to pay the arrears within a fixed time."

29. As for costs, the matter has been dealt with definitively by the Court of Appeal in Patel v

K&J Restaurants Ltd [2010] EWCA Civ 1211, in which it was said (within a detailed

examination of the authorities at paras.96-104):

Page 9 of 18Pineport Ltd v Grangeglen Ltd [2016] EWHC 1318 (Ch) (13 June 2016)

01/07/2016http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2016/1318.html

"Having given closer consideration to the authorities on the appropriate basis of

costs than was possible during the hearing of the appeal, I have come to the

conclusion that the indemnity basis should apply as a general principle…

normally this should require that the Applicant for relief should pay the

landlord's costs on the indemnity basis, rather than only on the standard basis."

The issues

30. It is not in doubt that the High Court has jurisdiction to grant relief against forfeiture on the

Claimant's application. The principal issues for the court to consider are:

i. Should the Claimant's delay in making the application for relief preclude the

grant of relief?

ii. Should account be taken of the Claimant's use of Unit 4 for illegal activity?

Does that activity bring this case within the band of exceptional cases whereby

relief should be refused albeit but for the illegal activity relief would have been

granted?

iii. What other circumstances should be taken into account? Should the court

take account of the value of the underlease measured against the size of the

arrears of rent and, if any, prejudice to the Defendant resulting from the non-

payment of rent?

iv. Upon what terms should relief be granted and is the Claimant in a position

to comply with such terms?

31. Although delay may ultimately be determinative, it would in my judgment be wrong to deal

with this issue in isolation without regard to all the circumstances because the court's

discretion is a broad one and the conclusion will follow from an overall review. I propose to

consider the circumstances of this case taking into account all of the relevant issues rather

than treating the exercise as a series of thresholds for the Clamant to surmount with delay

being an initial hurdle.

The evidence

32. The parties exchanged witness statements in accordance with the court's directions. Mr

Shorab Jadunandan gave evidence on behalf of the Claimant and Mr Edward Thompson a

solicitor with Blaser Mills LLP, the Defendant's solicitors, gave evidence on behalf of the

Defendant. At the conclusion of Mr Shorab Jadunandan's evidence, Mr Bowker, who

appeared for the Claimant, applied for permission to adduce evidence from Mr Rodion

Jadunandan, who is Shorab's brother, and for relief from sanctions. (For the sake of brevity

and without I hope causing offence I will refer to them respectively as "Shorab" and

"Rodion"). The application was opposed. Having heard submissions from both counsel on

this application I determined the application should be granted applying the approach set out

in Denton v TH White Ltd and said I would give reasons in my judgment.

33. Rodion's evidence covers one issue in the claim, namely how the Claimant will be able to

meet an order to pay the arrears of rent and other sums as a condition of granting relief. It is

right to characterise that issue as being subsidiary to the principal issues concerning the

grant or refusal of relief. I was told that Mr Bowker had only been instructed a week before

the trial and he expressed concern about the lack of evidence about the Claimant's ability to

make a payment. The evidence was therefore procured at the last moment. It is undoubtedly

the case that the breach of the order for exchange of witness statements was serious and

Page 10 of 18Pineport Ltd v Grangeglen Ltd [2016] EWHC 1318 (Ch) (13 June 2016)

01/07/2016http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2016/1318.html

significant. Shorab's witness statement does not deal at all with the Claimant's ability to pay

any sums due although the particulars of claim say that £2,155 has been deposited with

solicitors acting for the Claimant. Clearly an element of essential evidence was overlooked

by the Claimant's advisers until it was pointed out by Mr Bowker. Oversight by legal

advisers will not normally be a good excuse for failing to comply with an order.

34. Mr Demachkie submitted that relief should be refused in view of the absence of an adequate

reason for the failure to produce the evidence upon exchange of witness statements and

taking into account the provision of CPR 3.9(1)(a) and (b). He pointed to the lateness of the

application for relief itself and submitted that the attempt to adduce late evidence was

symptomatic of the Claimant's approach. Mr Bowker urged me to take account of the wider

circumstances and submitted that it would a denial of justice if the evidence could not be

submitted.

35. My decision to permit the Claimant to rely upon Rodion's evidence is principally based on

the following considerations:

i. The Claimant did not fail to comply with the order for exchange of witness

statements altogether. A full witness statement from Shorab was provided.

ii. A error was made about the extent of the evidence which was needed.

Shorab's witness statement failed to deal with this one point.

iii. There has been no prejudice to the Defendant and the trial was able to

proceed without being affected by the later evidence.

iv. Given that the sentence of imprisonment was passed after Shorab's statement was served,

it was inevitable that some additional evidence in chief would be required and no objection

was taken to Shorab explaining his position when giving evidence. In the light of the

sentence of imprisonment Shorab became unable to work and clearly could not conduct the

Claimant's business. There has been a change of circumstances. Shorab could have given

evidence about his understanding of his brother's willingness to assist with the payment of

any sums which are ordered to be paid but it is clearly preferable to have Rodion's evidence

on the point.

36. Shorab was brought to court to enable him to give evidence. I was satisfied that he was a

truthful witness. He answered questions put to him by Mr Demachkie in a straightforward

way and I have no doubt about accepting the majority of his evidence notwithstanding that

he has recently pleaded guilty to a number of offences of dishonesty. He candidly accepted

that he had acted wrongly and he accepted his guilt by making pleas of guilty. The restraint

order remains in place and he now faces confiscation proceedings under the Proceeds of

Crime Act which he said may be concluded in 2017 but may run in to 2018. The CPS is

seeking a confiscation order in a sum between £400,000 and £450,000 between himself and

the Claimant.

37. Shorab agreed that paragraph 3 of the Reply was incorrect and that a number of demands for

payment had been made by the Defendant before re-entering Unit 4. He said that he left the

management of the Claimant's finances to others and he was not aware of the demands for

payment of the arrears whilst not seeking to excuse his lack of knowledge. He did not

dispute that there were arrears of rent at the date of re-entry, and there had been arrears in

varying amounts over the previous three years, although his understanding had been that a

payment of £4,807.84 made not long before the forfeiture was to be allocated against sums

due relating to both Units 4 and 5. In fact the payment was allocated by the Defendant

Page 11 of 18Pineport Ltd v Grangeglen Ltd [2016] EWHC 1318 (Ch) (13 June 2016)

01/07/2016http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2016/1318.html

solely to sums due in respect of Unit 5 because it arose from enforcement action taken

solely in respect of Unit 5.

38. On 2 September 2013 Tony Simpson, an employee of the Claimant, sent Andrew Butler of

Colliers International an email explaining that the Claimant was subject to an investigation

by VOSA and that it was unable to issue cheques. The email was acknowledged by Mr

Butler the following day expressing sympathy but pointing out that the Claimant held two

valuable assets and making it clear that unless payment of the arrears was made the leases

would be forfeited. There was no reply either to that email or to the email sent by Mr Butler

on 22 September 2013. Colliers sent a letter by email on 31 January 2014 referring to these

emails and others and providing a statement showing that the arrears had reached £2,003.65.

This was followed by a s.146 notice sent on 3 April 2014. Shorab may be right in saying

that the S.146 notice was never received by the Claimant because it was sent to Unit 4

where it would have been received by the sub-tenant but nothing turns on this.

39. Shorab says that he first saw his GP in December 2013 because he had become withdrawn

and deflated and he was diagnosed as suffering from depression. He was prescribed an anti-

depressant named fluoxetine which he started taking. He saw his GP again in January 2014

because he felt worse and the anti-depressants were not helping. This account is supported

by a letter from his GP. He was referred for counselling and attended his first counselling

session in mid-April 2014. However by that time he had stopped taking the medication,

because it did not agree with him, and he did not continue with counselling because he

thought he was about to be sentenced. In fact the sentencing was adjourned but he did not

take up another appointment with the counsellor. Thus by the end of April 2014 he was no

longer receiving treatment or medication for depression. He describes his ability to cope

with his business as being up and down and he had mood swings. He said he had to control

his condition himself. He believes that his depression caused a lack of mental clarity and

prejudiced his ability to take prompt steps to seek relief from forfeiture. Although the

quality of evidence about Shorab's mental state is limited, his circumstances and the way he

behaved does to my mind lend strong support to him continuing to suffer from depression

and an inability to cope with his business affairs. Some measure of support for this view can

be obtained from the shear irrationality of allowing an asset belonging to the Claimant with

a value of £275,000 to be forfeited to the Defendant when the unpaid rent amounted to less

than 1% of its value.

40. Shorab was aware of the forfeiture in Unit 4 immediately after it occurred because he was

told about by the sub-tenant. He went to Unit 4 to see for himself and made efforts to

contact Andrew Butler at Colliers without his telephone calls being returned. He then spoke

to the Defendant's solicitors. He describes them as being evasive and unhelpful. Although

they may have appeared to be unhelpful, no doubt they were being properly cautious in

dealing with him and they recommended that he should seek legal advice. Thereafter Shorab

took only limited steps to recover the underlease. He says that due to financial difficulty

arising from the prosecution, the restraint order and the loss of the income from the sub-

tenant, he was not able to seek advice and that he was only later prompted to take action by

receiving notification from the Land Registry in about June 2014 saying that the lease title

would be closed. He contacted Makwanas who were the solicitors acting in the criminal

prosecution and they made contact with Blaser Mills. There is no evidence from

Makawanas on this subject but there is no reason to doubt the veracity of the attendance

note made by Mr Thompson of Blaser Mills of his conversation with Tulsi Shah of

Makawanas on 8 August 2014 (more than three months after the forfeiture). Ms Shah was

given information about the forfeiture, the arrears and that further sums had fallen due. She

said she would take instructions.

Page 12 of 18Pineport Ltd v Grangeglen Ltd [2016] EWHC 1318 (Ch) (13 June 2016)

01/07/2016http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2016/1318.html

41. Thereafter no further steps were taken until the Claimant's current solicitors were appointed

in 2015 and after an exchange of correspondence this claim was issued. Shorab says he

thought, wrongly, that the issue was being dealt with by Makwanas but tellingly he says that

he never imagined that Unit 4 could be taken away from him. He had no understanding of

how forfeiture works or what had to be done.

42. The Claimant is not currently trading and has not traded since VOSA withdrew its licence in

September 2012. Unit 5 is still owned by the Claimant but it is in the hands of receivers

appointed by the mortgagee. The Claimant's ability to pay any sum needed to obtain relief

from forfeiture is entirely dependant upon Rodion. Shorab disputes that some of the items

claimed by the Defendant are due but says Rodion is able and willing to pay whatever is

found to be due. The Claimant does not wish to lose the capital tied up in the underlease

which includes the benefit of improvements carried out not long after the lease was

purchased.

43. Rodion's evidence, which I accept with one qualification, is that he is the sole owner of 80

Chamberlayne Avenue, Wembley which is registered in his sole name under title number

NGL800596. The title entries show that Rodion acquired the property in 2001 and that it is

charged to Santander. Rodion says he re-mortgaged the property in 2010 and the amount

currently due to Santander is approximately £207,000. He produced a screen shot on his

telephone to confirm that figure. The property was placed on the market with Ellis & Co

Estate Agents on 30 March 2016 at an asking price of £349,950. If that price were to be

achieved, taking into account the expenses of sale, there would be net proceeds of about

£100,000. He believes that it will take about 6 weeks to realise this sum. An offer of

£348,000 has been received which he had accepted.

44. Rodion explained when cross-examined that he usually lives at 11 Heritage View, Harrow

where his mother, another brother, Shorab and Shorab's son also reside. He is willing to sell

80 Chamberlayne Avenue to help out Shorab and is willing to allow, if necessary, the entire

net proceeds of sale to be used. He does not regard this is as a loan and is prepared to take a

risk about whether Shorab will ever be able to pay him back. It is for him purely a family

matter, not commerce.

45. Rodion said that the sale had moved forward even since making his witness statement on 5

April 2016. The agents have reported to him there was a new offer of £352,000 which he

has accepted and there is yet further interest. However, he had scant details and did not

know anything about the purchasers and had not received anything in writing yet from the

agents. He accepted that the purchaser at £352,000 might be subject to a chain but expressed

unshakable confidence that the sale could be completed in 6 weeks. He was asked about an

offer which had been made on behalf of the Claimant on 24 February 2016 under which the

Claimant would pay £25,963.94 plus the Defendant's reasonable legal costs. Rodion said

that had the offer been accepted the Claimant, with his help from the proceeds of sale of 80

Chamberlayne Avenue, and funds held by his mother would have been able to pay the sum

offered. My only concern about Rodion's evidence is that he is almost certainly over-

optimistic about the length of time the sale of his flat will take to complete.

46. The Defendant called only Mr Thompson to give evidence. To my mind that was a

surprising decision because Mr Thompson, as the Defendant's solicitor, has only limited

first-hand knowledge about a number of key matters. Entirely understandably, Mr

Thompson was unable to provide helpful answers to many of the questions put to him in

cross-examination because he had no relevant knowledge. His statement includes a number

of paragraphs which are mere argument rather than evidence, including his opinion that the

court should not exercise its equitable jurisdiction in favour of the Claimant. His evidence is

Page 13 of 18Pineport Ltd v Grangeglen Ltd [2016] EWHC 1318 (Ch) (13 June 2016)

01/07/2016http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2016/1318.html

based upon what he has been told by Mr Andrew Butler. In particular, Mr Thompson was

not able to provide any real help about the schedule of expenditure the Defendant claims to

have incurred as a result of the forfeiture amounting to £66,717.02, save for those items

relating to his firm's legal costs. I accept Mr Thompson's evidence about his conversation

with Tulsi Shah of Makwanas Solicitors on 8 August 2014 which is recorded in his

attendance note. Mr Thompson has no recollection of being contacted by Shorab following

the forfeiture.

47. The correspondence and emails passing between Colliers and the Claimant were not

illuminated by Mr Thompson's evidence but they largely speak for themselves. It is not

seriously in doubt that the Defendant, through its managing agent and solicitors made real

efforts to recover, without taking enforcement action, the arrears which were due and the

Claimant cannot maintain the suggestion that it was taken by surprise. There is, however, a

most curious aspect of the Defendant's case concerning the schedule of expenditure the

Defendant now seeks if the court were to be inclined to grant relief. Mr Thompson says

baldly in his statement that "the Defendant has suffered prejudice following the forfeiture of

the Lease". He then refers to the schedule of expenditure after which he says:

"… the Defendant has suffered prejudice as it has been unable to re-let the

Forfeited Property for in excess of 18 months since forfeiture took place."

However, when cross-examined, Mr Thompson was unable to explain further the assertion

that prejudice had been suffered and he was unaware of anything the Defendant had been

unable to do as a consequence of the sum due not having been paid.

48. The most surprising aspect of the Defendant's case is that although Mr Thompson, entirely

in good faith, said he thought that the documents supporting the schedule of expenditure had

been disclosed pursuant to the order for disclosure, it has transpired that they were not

provided to the Claimant during the course of preparation for the trial. This is despite Mr

Thompson's firm having made observations about the trial bundles and added documents to

them. It was only after the cross-examination of Mr Thompson was almost complete during

the short adjournment on the second day of the trial that copies of the invoices were handed

to Mr Bowker. He completed his cross-examination without having had a chance to refer to

them and I ruled that they could not be relied upon for the purposes of re-examination. The

trial concluded without the invoices being part of the evidence before the court. I directed

that the Defendant could make submissions about the admission of those documents in

writing with the Claimant having an opportunity to respond. Submissions were duly

received form both parties. The Defendant requests the court to take the invoices into

account. The Claimant objects. I will approach this issue by first summarising Mr

Thompson's evidence about the schedule of expenditure and then considering whether the

invoices should be considered in order to supplement his evidence.

49. Mr Thompson says in his statement that the Defendant has incurred costs which include

service charges, buildings insurance, Local Authority Business Rates and electricity and

other charges. He goes on to say:

"25. Amongst other things, the Defendant has carried out work to secure the

Forfeited Property and ensure that the Forfeited Property is in a suitable

condition to be let to prospective tenants. The Defendant has attempted to

remove vehicles from the Forfeited Property, installed concrete barriers to

ensure the Forfeited Property remains secure.

26. As a result of the improvements to the Forfeited Property, if the Claimant is

granted relief from forfeiture in this claim, the Claimant will have a better

Page 14 of 18Pineport Ltd v Grangeglen Ltd [2016] EWHC 1318 (Ch) (13 June 2016)

01/07/2016http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2016/1318.html

Property with a substantially increased value of the Leasehold as a result of

their numerous breaches of the Forfeited Lease."

50. I do not find the logic behind these two paragraphs easy to follow. It is stretching a point to

say that a property is improved by attempting the removal of vehicles and it is not at all

clear upon what basis the value of the Unit 4 has been substantially increased or why that

increase in value should flow from the Claimant's breaches of covenant.

51. Mr Thompson said in evidence that the only document the Defendant was relying upon was

the schedule he exhibits and no other documents were relied upon. He was under the

impression that the underlying invoices had been provided to the Claimant's solicitors but he

now accepts that his belief was false. In any event, his firm had the opportunity to include

the invoices in the trial bundles but failed to take it up. As to remaining items:

i. Mr Thompson was not able to provide any help with the basis upon which the

loss of rent is calculated. The schedule of loss refers to an email from Mr Butler

but it has not been disclosed.

ii. He was able to provide a limited amount of help about the claim for legal

expenses. He said much of the work which has been invoiced was carried out

by him at a charging rate between £200 and £225 per hour. However, he said

the Defendant was not relying on any of the invoices.

iii. He was unable to provide any help about the calculation of service charges

after the forfeiture and has not seen the annual certificate which the underlease

requires to correct payments on account.

iv. His understanding, without having first-hand knowledge, is that the concrete

barriers installed in the parking area were there to maintain the security of the

unit by stopping anyone parking close to the shutters of Unit 4.

52. I have been provided with submissions by both parties together with the invoices and other

documents the Defendant wishes to rely on but failed to disclose. The court is asked to

admit them. The Claimant's response is qualified. Some of the items are accepted as proper

items to be included in the tally of sums payable as a condition of the grant of relief, without

accepting that such sums are due as a debt. In those instances the presence or otherwise of

the invoices makes no difference. As to the remaining items, the Claimant says the court

should decline to admit the invoices.

53. It is clearly unsatisfactory for documents to be produced in the course of a short trial

without the other party having an opportunity to consider them and at a moment of the trial

when the witness who relies on such documents has already been cross-examined and has

said in clear terms that additional documents are not relied upon. I can see no good reason

why these additional documents should be admitted. The Defendant had an ample

opportunity to prepare its case. The basis upon which disclosure was ordered was that each

party was required to disclose the documents relied upon. The Defendant has proceeded on

the basis that it did not rely upon the invoices and this was confirmed by Mr Thompson. As

the only witness called by the Defendant he was not in a position to speak to any of the

invoices other than those rendered by his firm and in many instances the invoices do not

speak for themselves. Furthermore, not only were they were produced at a very late stage of

the trial but without there being any adequate excuse for their omission. Indeed, I have a

strong sense that they were only produced in an attempt to bolster Mr Thompson's evidence

when it must have been clear before the trial that he would be unable to help the court about

most of the expenses claimed. It remains hard to fathom why he was tendered as a witness

Page 15 of 18Pineport Ltd v Grangeglen Ltd [2016] EWHC 1318 (Ch) (13 June 2016)

01/07/2016http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2016/1318.html

instead of someone with relevant knowledge. For all those reasons I decline to exercise my

discretion to admit the invoices which were provided to me after the trial.

Decision

54. At first sight, the Claimant's case does not look promising given the length of the delay in

making the application for relief. A helpful starting point, however, is to consider what the

terms of relief would be if relief is granted and whether the Claimant is able to comply with

them. I start, therefore, by considering the Defendant's schedule of expenditure a copy of

which forms appendix 1 to this judgment. For the purposes of the grant of relief the

Claimant accepts the items under the following headings:

Insurance £2,361.46

Business rates £14,043.66

Electricity £112.86

Bailiff's fee £644.88

Land Registry Fee £12.00

DVLA fee £12.50

Shutters £230.00

Ground rent £200.00

Service charges up to forfeiture £2,155.00

TOTAL £19,772.36

55. A claim is made for 'loss of rent' amounting to £14,808.23. I can disregard the absence of a

proper explanation for the calculation because the Defendant has not incurred a loss of rent,

other than the ground rent. The underlease was granted for a substantial premium at a

ground rent. During the twilight period pending the application for the grant of relief and

pending the trial of the claim the only loss suffered by the Defendant is the ground rent,

insurance rent and service charges. No evidence has been provided about efforts made by

the Defendant, if any, to let Unit 4 or to grant a new long lease.

56. The largest remaining item is legal fees. The Defendant is only entitled to recover as a

condition of the grant of relief legal expenses relating to the forfeiture. Legal fees of the

claim seeking relief are at large and fall to be considered applying the provisions of CPR

44.2. Five invoices were rendered to the Defendant. Three invoices post-date the issue of

the claim and are clearly costs of the claim. The two invoices which pre-date the claim are

for £4,856.88 (dated 30.9.14) and £1,203.00 (dated 19.03.15) and total £6,059.88. Mr

Thompson's witness statement does not explain these invoices and he was not able to

provide any real assistance under cross-examination. It is notable that the bailiff's fee is not

included and at least some legal work in the form of serving a s.146 notice was otiose. It

would wrong to ignore the legal expenditure altogether because it clearly relates to the

forfeiture but on the basis of the evidence cannot be allowed in full. Doing the best I can I

will allow 50% (rounded to) £3,000.

57. The claim for service charges has to be approached in a similar way. Although the

information is inadequate I cannot ignore the reality that service charges will have

continued to accrue. In the absence of annual certificates and invoices I will take the

Page 16 of 18Pineport Ltd v Grangeglen Ltd [2016] EWHC 1318 (Ch) (13 June 2016)

01/07/2016http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2016/1318.html

advance rate which prevailed at the time of the forfeiture which was £152 and allow eight

quarters which totals £1,216.

58. The remaining items in the schedule can be dealt with compendiously on the basis either

that the Defendant has not provided sufficient evidence to support them or has not been able

to demonstrate that the items of expenditure are related to the forfeiture.

59. Thus if relief is to be granted the sum to be paid totals £23,988.01 plus interest at a rate to

be determined. The Defendant is entitled to interest on this sum which I assess at 1% over

base rate during the period since re-entry and taking a broad view I shall assume that the

liabilities accrued evenly over the period up to the issue of the claim. The full interest rate

will apply thereafter. Rounding interest for convenience, I turn therefore to consider

whether the Claimant has established that it is able to meet a liability of £24,530 within a

reasonable period as a condition of the grant of relief.

60. As a starting point, I note that this figure is less than the amount the Claimant offered to

pay, plus reasonable costs, on 24 February 2016. It seems unlikely that no consideration was

given, before this offer was made, to how the sum would be paid. Although Rodion's

evidence about the likely time it will take to complete the sale of his flat was optimistic, I

am satisfied that the flat is on the market, there is a buyer and a real likelihood of a sale

taking place within a matter of weeks. Rodion is willing to lend Shorab (and he in turn will

lend the sum to the Claimant) sufficient money to enable the Claimant to pay the sum which

will be payable as a condition of the grant of relief within the immediately foreseeable

future. Without being over precise it seems likely that the money will be available within 12

to 16 weeks of the trial date. This is sufficiently soon to be the "immediately foreseeable

future".

61. I turn to consider the relevance of the illegal activity which led to Shorab's conviction and

sentence of imprisonment. The evidence about this subject is very limited. No evidence was

called by the Defendant who wishes to rely on the seriousness of the offending. Plainly the

sentencing judge regarded the offences as being well over the custody threshold and one

which merited for offences of dishonesty a moderately severe sentence. The conduct

involved activity directly connected with the Claimant's principal business carried on at Unit

4. However, it seems to me that even taking those factors into account it does not fall within

the exceptional category which Jenkins LJ had in mind in Gill v Lewis. His principal

concern appears to have been the risk of the court appearing to be complicit in the continued

use of premises for unlawful or illegal activity by granting relief in the knowledge that such

conduct was likely to continue. That concern simply does not arise here. The Claimant has

lost its licence to grant MOTs certificates and there is no real risk of the conduct being

continued. There is also only very limited evidence about the possibility of the premises

having been tainted by the past conduct. I conclude that Shorab's conviction is not a relevant

factor.

62. The underlease was granted for a substantial premium at a ground rent. To my mind this is

an important factor which weighs heavily in the balance. There may well be different

considerations in relation to a lease at a rack rent. The court should have regard to the value

of the asset which the Defendant will obtain if relief is refused compared with the rent

outstanding at the date of forfeiture and the sum payable as a condition as the grant of relief.

The Defendant exercised its right to forfeit the underlease when the unpaid rent amounted to

£2,155, rather less than 1% of the capital value of the underlease. If relief is granted, the

sum payable will be about 10% of its value. Although it would be wrong to apply a purely

arithmetic approach, in both cases there is a severe disproportion between the value

obtained by the Defendant as a windfall, if relief is refused, and the sum due to the

Page 17 of 18Pineport Ltd v Grangeglen Ltd [2016] EWHC 1318 (Ch) (13 June 2016)

01/07/2016http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2016/1318.html

Defendant. It seems to me, therefore, that the Claimant in this case has a particularly

powerful case for relief given the starting point that equity regards the right of re-entry in

the case of unpaid rent as security for payment.

63. The Defendant is not able to point to any prejudice it, or any third party, has suffered as a

result of the failure to pay the rent on time, the forfeiture or, indeed, the delay in making the

application. The Defendant took no steps to market Unit 4 with a view either to the grant of

a lease at a market rent or a long lease for a premium. The Defendant stood by to await

events.

64. The very lengthy period of delay is a matter of very great difficulty for the Claimant to

overcome. I have to consider whether it can be said the application was made with

"reasonable promptitude" taking the 6 month period as a guide and having due regard to it.

There is an explanation for the long delay. It arises from a combination of Shorab's ill

health, the restraint order, the lack of money and the absence of specialist advice. His

evidence that he did not believe it was possible for the lease to be taken away from the

Claimant rings true in view of its value. That evidence combined with the well understood

effects of depression, of which I take judicial notice, which may include an inability to

focus on important issues, are weighty factors to be put in the balance. The discretion to

grant relief is a broad one and I am not constrained by a fixed time limit which prevents the

court from granting relief. Reasonable promptitude is an elastic concept which is capable of

taking into account human factors, including those I have mentioned. Although 14 months

is more than double the guide period of 6 months (and near to the breaking point for the

concept's elasticity), I am satisfied that it would be wrong to bar the Claimant from

obtaining relief in the circumstances of this case. In the light of the evidence I am able to

conclude that the application was made with reasonable promptitude.

65. I will make an order granting the Claimant relief from forfeiture in relation to Unit 4 on

terms that the Claimant pays to the Defendant the sum of £24,530 within a period following

the date of handing down this judgment which I will fix after hearing submissions. I will

hear counsel as to the remaining terms of the order and any other matters which arise.

BAILII: Copyright Policy | Disclaimers | Privacy Policy | Feedback | Donate to BAILII

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2016/1318.html

Page 18 of 18Pineport Ltd v Grangeglen Ltd [2016] EWHC 1318 (Ch) (13 June 2016)

01/07/2016http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2016/1318.html