Earthquake Disaster Response in Christchurch, New Zealand

-

Upload

brian-dolan -

Category

Documents

-

view

213 -

download

1

Transcript of Earthquake Disaster Response in Christchurch, New Zealand

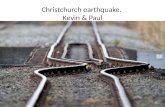

EARTHQUAKE DISASTER RESPONSE IN

CHRISTCHURCH, NEW ZEALAND

Authors: Brian Dolan, MSc (Oxon), MSc (Nurs), RN, Anne Esson, BA (Educ), RGON, Paula (Polly) Grainger, MN(Clinical), Dip HE (nursing), RN, PhD (C), Sandra Richardson, BA, RGON, Dip Soc Sci, DipHeal Sci, Dip Tert Teach, PhD

(C), and Mike Ardagh, PhD, MBChB, FACEM, DCH, Christchurch, New ZealandSection Editors: Pat Clutter, MEd, RN, CEN, FAEN, and Carole Rush, MEd, RN, CEN, FAEN

On September 4, 2010, an earthquake that mea-sured 7.1 on the Richter scale struck the regionof Canterbury, New Zealand. Even though it

was the same magnitude as the Haitian earthquake in Jan-uary 2010 that killed more than 220,000 people, not oneperson lost his or her life in the city of Christchurch.Human survival was due to 3 interrelated elements: rigor-ously applied building codes, the earthquake’s depth of6 miles (10 km) and distance of 25 miles (38 km) fromChristchurch, and the early morning time of the occur-rence (4:35 AM). Although damage was significant, manyof Christchurch’s major landmarks survived, and duringthe following months, locals began to tell with unerringaccuracy the magnitudes of the thousands of aftershocks thatare normal after these events. What came a few months laterwas a whole different situation.

Tuesday, February 22, 2011, started out as an ordinaryday in many ways in Christchurch. The continuing after-shocks were subsiding in both frequency and intensity, andalthough a number of buildings had been damaged or evendestroyed by the earlier earthquake, most people were sim-ply getting on with their day in hospitals, schools, offices,

and homes. In the Christchurch Hospital EmergencyDepartment—one of the busiest emergency departmentsin the southern hemisphere, where more than 87,000patients are seen each year— the day also started quite ordi-narily. This emergency department is almost unique in thedeveloped world, because it is the only emergency depart-ment in a city of 400,000; the next nearest emergencydepartment is a 4-hour drive away. When a magnitude6.3 earthquake struck at 12:51 PM, staff struggled to stayon their feet as the lights went out. The emergency genera-tors were challenged to maintain a supply of electricity andfailed over the course of the following hours as dozens ofaftershocks struck (Figure 1).

Unpredictable Movement of the Earth

Earthquakes do not all feel the same. The September quakehad people feeling they were rolling side to side, backwardand forward, over and over as the earth convulsed beneaththem. The February quake has been described as being liketrying to walk on a trampoline while someone else wasbouncing on it. It was located a mere 3 miles (5 km) deepand 6 miles (10 km) from the city centre. People in the cityran out of buildings, lost their balance, and lost their livesas masonry crashed onto their prone bodies. Even sitting ina car or bus didn’t always provide protection, as lives werelost there, too. Inside buildings, people were thrown to thefloor, and unable to get up, they crawled under tables ifthey could, while those who could not protect themselvesperished as walls and ceilings fell on top of them (Figure 2).Most of the unlucky ones, who were in the wrong place atthe wrong moment, died within seconds of massive crushand head injuries.

Initial Civilian Response and

Communication Challenges

Much of the emergency department had been newly builtjust a few years earlier, and although it shook violently,many staff dusted themselves off and got on with theirwork, not realizing that less than a mile away, the destruc-tion of lives and buildings was enormous (Figure 3). It wasmany hours before the location of the epicenter and scope

Brian Dolan is Director of Service Improvement, Canterbury District HealthBoard, New Zealand.

Anne Esson is Nurse Manager, Christchurch Hospital Emergency Depart-ment, Christchurch, New Zealand.

Paula (Polly) Grainger is Nurse Coordinator, Clinical Projects, ChristchurchHospital, Christchurch, New Zealand.

Sandra Richardson is Nurse Researcher, Christchurch Hospital EmergencyDepartment, and Senior Lecturer with the Centre for Post Graduate NursingStudies, University of Otago, Christchurch, New Zealand.

Mike Ardagh is Professor of Emergency Medicine, Christchurch HospitalEmergency Department, Christchurch, New Zealand.

For correspondence, write: Brian Dolan, MSc (Oxon), MSc (Nurs), RN, c/oBusiness Development Unit, Canterbury District Health Board, 33 St AsaphSt, Christchurch, New Zealand; E-mail: [email protected].

J Emerg Nurs 2011;37:506-9.

Available online 5 August 2011.

0099-1767/$36.00

Copyright © 2011 Emergency Nurses Association. Published by Elsevier Inc.All rights reserved.

doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2011.06.009

I N T E R N A T I O N A L N U R S I N G

506 JOURNAL OF EMERGENCY NURSING VOLUME 37 • ISSUE 5 September 2011

of the disaster could be communicated to staff, who wereworking with limited access to radio, television, andphones. Within minutes the first patient, a young child,was brought in, requiring full resuscitation. For many staff,the sight of this child, carried in the arms of a civilian res-cuer who had run from the city centre to the hospital,remains a poignant memory. And the wounded kept com-ing, arriving via all available means of transport: in flat bedtrucks and cars, carried on doors and roofing iron, and onfoot. Some 365 disaster documentation packs were usedbefore supplies were depleted.

External Triage Established

The emergency plan swung into action smoothly, and itwas determined that a triage point should be establishedin the car park adjacent to the emergency department.Patients were then triaged to a range of treatment areas;many minor injuries were treated immediately in the carpark. Other patients were sent to the main OutpatientDepartment or the Fracture Clinic if they had minorinjuries needing more complex interventions, such assutures. The main “trolley” areas of the emergencydepartment were used for more serious injuries such asfractured hips or even chest pain, while the trauma andresuscitation bays were used for persons with immediateand life-threatening conditions. Two waves of patientsarrived, many of whom were seriously injured; the firstwave was those injured but not trapped, and the secondwave was those extricated from the rubble—many withsevere crush injury syndrome.

Working Conditions For Which Disaster Plans Cannot

Fully Prepare Staff

Many persons said that if the September 4, 2010, earth-quake was the dry run, then undoubtedly this earthquakewas the real thing. In the emergency department hundredsof patients were seen with crush injuries, head injuries,chest pains, fractures, lacerations, and traumatic amputa-tions. At times, the ED staff was literally working in thedark, trying to intubate, insert intravenous lines, and assess

FIGURE 1

ED staff working by torchlight.

FIGURE 2

Tattoo parlor aftermath.

FIGURE 3

Footbridge near Christchurch Hospital.

Dolan et al/INTERNATIONAL NURSING

September 2011 VOLUME 37 • ISSUE 5 WWW.JENONLINE.ORG 507

patients even as the emergency power continued to failintermittently, given the violence of the aftershocks.Meanwhile, Christchurch Hospital evacuated 4 wards.While the hospital was managing the scores of injuredpersons who were presenting for treatment, staff were alsoorganizing the transportation of patients from the facilityduring the complicated and overwhelming situation.

Other non-emergency hospitals and primary care facil-ities were quickly inundated with patients, some withmajor trauma and crush injuries. A number of facilities alsowere badly damaged by the quake (Figure 4). A St John

Ambulance field station, led by an ED physician who isalso the St John Medical Director, was established in theCentral Business District, where most of the injuries andfatalities occurred. In all, some 2500 people were injuredand 182 were killed.

Crush Injuries: A Prevalent Scenario

Coincidentally, a urology conference and an advanced lifesupport conference were both being held in the city centre.In at least one instance, surgeons were faced with the griz-

FIGURE 4

ED waiting room the day after the earthquake.

FIGURE 5

Urban Search and Rescue teams from around the world.

FIGURE 6

John Knox Presbyterian Church will need to be demolished.

FIGURE 7

“Broken but still beating”: A message of hope outside John Knox PresbyterianChurch in Christchurch, New Zealand.

INTERNATIONAL NURSING/Dolan et al

508 JOURNAL OF EMERGENCY NURSING VOLUME 37 • ISSUE 5 September 2011

zly task of performing an on-scene amputation with a hack-saw and a foldout knife, with the patient mercifully anaes-thetized by a hospital anesthetist who went to the scene toassist. The maxims with on-scene amputations are “now ornever” and “not who, but when.” It also took particularcourage on the part of medical teams to go into buildingsthat were at sustained risk of collapse to support fire andrescue teams and deliver life-saving medical care. Sadlyfor many persons, however, death—unblinking and remor-seless—reached people before their rescuers did.

Although they are rare in other forms of disaster events,crush injuries are not uncommon in earthquakes. A featureof crush injuries is rhabdomyolysis, that is, the breakdown ofskeletal muscle fibers that results in the release of myoglobininto the bloodstream. This process is harmful to the kidneysand can lead to significant kidney damage, thus requiringrenal dialysis. Community and inpatient dialysis patientswere transferred quickly out of the region to allow for theinflux of crush injury–related patients, and the Royal NewZealand Air Force flew dozens of other patients to othercities to release capacity. A particular challenge, due to theaftershocks, was the need to constantly recalibrate the dialy-sis machines, especially on the first day.

Rapid Outside Response

A further feature of this earthquake, unlike those in moreremote or less developed areas, was how quickly the rescueteams arrived on scene. New Zealand has highly experi-enced Urban Search and Rescue teams, and within daysthese teams were supplemented by civil and military teamsfrom the United States, Australia, the United Kingdom,China, Japan, Mexico, and many other countries. Theycommented widely that it was the best coordinated disasterresponse they had ever encountered (Figure 5).

About 70 people were rescued alive from collapsedbuildings. The last survivor came out a little over 24

hours after the earthquake, even though the internationalstandard for expecting survivors is usually 72 hours. Thisspeed is a tribute to the effectiveness of the UrbanSearch and Rescue teams, who themselves remained inconstant danger working in highly unstable buildingswith frequent aftershocks.

Amazing Resilience

Staff continued to work, even when their homes were sobadly damaged that they would have to be demolishedand they did not know if all of their family members weresafe. In all, some one third of all central business districtbuildings were destroyed, including two thirds of heritagebuildings, such as the iconic Anglican and Catholic Cathe-drals (Figure 6). The homes of some 25% of health carestaff were damaged, many irreparably.

As we move from the drama of the first phase of rescue,the recovery phase has begun and will take years to complete.Above all else, in the days of darkness, the resilience,community spirit, and innate decency of New Zealandersshone like a lighthouse while waves of grief come crash-ing around them, as they mourned so many lost lives(Figure 7). Although Christchurch has stumbled, therest of the world will hold its hands on its long journeyback to a new normal in a renewed city with theMaori cry of affirmation ringing across the land, “KiaKaha”—Forever Strong.

Submissions to this column are encouraged and may be sent toPat Clutter, MEd, RN, CEN, [email protected] Rush, MEd, RN, CEN, [email protected]

Dolan et al/INTERNATIONAL NURSING

September 2011 VOLUME 37 • ISSUE 5 WWW.JENONLINE.ORG 509