Dr ryden maroon studies for social sciences

-

Upload

ted-b-shull -

Category

Documents

-

view

213 -

download

1

description

Transcript of Dr ryden maroon studies for social sciences

Dr. David B. Ryden, PhD, Associate Dean of UHD’s college of Humanities and Social Sciences, gives personal interview to Dateline Downtown after presenting research at the 2013 Social Science lecture series.Theodore B. Shull – Staff Reporter

November 8, 2013

Dr. David Ryden, U.H.D. professor of History, presented his most recent research project studying small communities of runaway slaves, known as “Maroon” communities in Jamaica, and how the Jamaican Maroon community was able to flourish in trade, living in the northern highlands of Jamaica and live in relative peace alongside the English Colonial Government in Jamaica. Dr. Ryden’s research explores a treaty that the Maroon communities signed with the British in 1738-39, and how this former slave rebel group received huge benefits like land ownership and the ability to participate in the market economy by becoming collaborators with the British white elite. The Maroon’s living in the interior were paid by the British to refuse any new escaped slaves into their society, and use their expertise in Guerilla warfare and knowledge of the Jamaican interior terrain to catch new runaway slaves which were being imported in large numbers to operate on Sugar Plantations.

Interest in the historical and developmental aspects of these minority

groups exploded in the 1960’s with mass increases in funding for sociological and anthropological studies, and an increased interest in understanding cultures (other than the white colonialists) that really emerged during the ‘60’s. Dr. Ryden also speculated that there was significant interest in the fierce guerilla tactics of the Jamaican Maroons, as the U.S. military became bogged down in its own fierce

guerilla campaign in Vietnam.

Fierce Maroon Guerilla Warriors –Google Images

Dr. Ryden, an economic historian, outlined the specific economic benefits the Maroons enjoyed under the 1738-39 treaty. It would have “legitimized Maroon ownership of the land they occupied, given access to the islands market economy, and allowed Maroon mobility”, or the freedom of autonomous movement throughout the island, giving the community access to produce and purchase textiles, agriculture, livestock, and metal-ware, including weapons. The Maroon communities thrived during this period, with access to mountain springs and a plentiful supply of wild animals for food, they arguably had better living conditions than African slaves on the lowland sugar plantations, and even the plantation owners themselves.

The 1738-39 Maroon treaty with the British came to an abrupt halt for the group

of Maroons living in Trelawney town. In 1796, two youth of the Trelawney town Maroons were convicted by the Montego Bay magistrate for theft of “domesticated” hogs, and this event, which was never disputed by the Maroons, became the mat,ch that ignited a tinder-box of built pressure among the Maroons. The demeaning punishment meted out to these two boys became stirred up more complaint against the Colonial government, in part because they believed the punishment, which called for whipping of the boys by slaves, was a violation of the 1738-39 treaty, and was a powerful symbol to the Maroons that in the eyes of British, the Maroons were still equal in status to that of the slaves, and by 1795 the Trelawney Town Maroons issued a list of complaints, and after sensing that a “rebellion might be afoot”, as Britain faced in several of its colonies in the late 18th century, and began its Second Maroon War.

Casualties were very high on the British side, and the Trelawney town Maroons were lured to a “Friendship Feast” by the colonial Governor. The Trelawney Town Maroons agreed to surrender on the guarantee that they would not be deported from Jamaica. The fierce Maroon fighters, highly skilled at warfare but not diplomacy, fell for the British trap. Upon reaching the governors home, the Maroons were deported en masse to Halifax, Nova Scotia as victims of “white deceit”.

The true Maroon legacy is difficult to tease out, as almost all written sources come from the British, however their oral history continues to be passed down over the centuries. Jamaican historian Mavis

Campbell, in her book “The Maroons of Jamaica, 1655-1739: A History of Resistance, Collaboration and Betrayal” speaks of the “ambivalent legacy” the Jamaican Maroons left. Praised as heroes against Slavery by some, and condemned by others as self-seeking collaborators who flipped on a dime to help catch slaves for the British, their legacy is still felt today through music in Afro-pop and Reggae, and while they did not seek to change the status-quo system, such as what happened in Haiti. The Maroons, according to historian Mavis Campbell believes “Their fight for freedom still represents another chapter in the history of the human struggle for the expression of freedom – with all of its contradictions”.

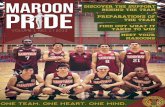

Dr. David Ryden, PhD, and Associate Dean of the College of Social Sciences and Humanities.