CR May10 Pages

-

Upload

colorado-christian-university -

Category

Documents

-

view

220 -

download

0

Transcript of CR May10 Pages

8/9/2019 CR May10 Pages

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cr-may10-pages 1/4

CIVILIZATION AND SAVAGERY: VIRGIL FOR TODAY

By Michael Poliakoff

Editor’s Note: Higher education today is ever less high. Our

institute stands against that trend. In shaping contemporary

citizens, we honor the ancient landmarks. This month’s

Centennial Review is not light reading. But Poliakoff’s insights

will repay you well. Aeneas speaks powerfully to our times.

The invitation this essay offers

is to travel an arduous path. It

will have sublimity, since we will

be looking at a masterwork of

the ancient world, the Aeneid ,

written by Virgil in what

Tennyson called “the stateliest

measure ever moulded by the

lips of man.” But the journey

will indeed be arduous, because

this ancient text will make us travel inside the human soul

and face some very hard questions about good and evil,

civilization and savagery, theirs and ours.

C.S. Lewis saw in Virgil’s epic poem a turning point in

civilization and a rite of passage for the reader:

No man who has once read it with full perception remains

an adolescent. … Virgil, with no intention of allegory, has

described once and for all the very quality of most human life

as it is experienced by anyone who has not yet risen to holiness

or sunk to animality. …You cannot be young twice. The

explicitly religious subject for any future epic has been dictated

by Virgil; it is the only further development left.

Virgil’s work is a classic that continues to speak to heartsand minds far removed in time, place, culture, and language

from its author. Its message is as urgent today as it was

in the time of Augustus Caesar. It challenges all of us, as

Lewis observed, to come into full maturity.

In this essay, we look rst at the impact of Virgil’s work in

preceding centuries. It has a central position in our cultural

literacy. We will also examine the context of the Aeneid ’s

creation: what it meant to live during the Roman Civil War

and the reign of Augustus. Then we return to the yet more

urgent question of why his work should matter to us.

Publius Vergilius Maro was born in 70 B.C. By 29 B.C when he completed his second poem, the Georgics , called

by John Dryden, “the best poem by the best poet,” Virgi

had wealth, stature, and even the ear of Caesar. The na

decade of Virgil’s life was devoted to the Aeneid , which h

composed at the average rate of two lines per day, leaving i

unnished when he died in 19 B.C. Ever the perfectionist

Virgil begged that the manuscript be burned. Augustu

fortunately, interceded and this monument of civilization

became the treasure of lands and peoples beyond th

farthest imagination of Rome.

Impacting Constantine, Augustine, Dante

Virgil’s works were instant classics. There are mo

manuscripts of his writings than of any other classica

author, and several are expensive, sumptuous copies, a sign

of his great popularity. It was a school text St. Augustin

recalls how in his youth he was required to know abou

the wanderings of Aeneas but did not take note of hi

own (moral) wanderings. Virgil weighed heavily upon him

as it did upon all educated Romans of his day. He wep

for Dido, the lost love of the Aeneid ’s hero, when, he tell

us, he should have wept for his own distance from God

( Confessions I.13-17). Like Augustine, the poet Dante draw

insight into the human heart and soul from Virgil, and it is

no accident that Dante makes Virgil his guide through hi

Inferno and Purgatory .

By the Middle Ages, Virgil has become a character larger

than life. In spelling his name with an “i,” even though the

Romans spelled it with an “e,” we follow medieval legend

where the poet becomes a necromancer with a magic wand

( virga in Latin). People used Virgil’s works for divination

and the early church had its own special legends of Virgil’

inuence and power. His fourth Eclogue, telling of the birth

Centennial ReviewEditor, John Andrews

Michael Poliakoff is policy director for the American Council of Trustees and

Alumni in Washington, D.C. He holds degrees from Oxford and the University

of Michigan. He has taught classics at Wellesley College, Hillsdale College,

Georgetown University, and George Washington University. He was formerly vice

president for academic affairs at the University of Colorado, deputy education

secretary in Pennsylvania, and a program director at the National Endowment

for the Humanities.

Centennial Institute sponsors research, events, and publications to enhance

public understanding of the most important issues facing our state and nation.

By proclaiming Truth, we aim to foster faith, family, and freedom, teach citizen-

ship, and renew the spirit of 1776.

Principled Ideas from the Centennial Institute

Volume 2, Number 4 • May 2010

Publisher, William L. Armstrong

8/9/2019 CR May10 Pages

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cr-may10-pages 2/4

CENTENNIAL REVIEW is published monthly by the Centennial Institute at ColoraChristian University. Designer, Danielle Hull. Illustrator, Benjamin Hummel.

Subscriptions free upon request. Write to: Centennial Institute, 8787 Alameda Ave., Lakewood, CO 80226. Call 800.44.FAITH. Or visit us online www.CentennialCCU.org.

Join the Centennial Institute today. As a Centennial donor, you can help urestore America’s moral core and prepare tomorrow’s leaders. Your gift is tadeductible. Please use the envelope provided.

Colorado Christian University seeks to impact the culture in support of traditionfamily values, sanctity of life, compassion for the poor, a biblical view of humanature, limited government, personal freedom, free markets, natural law, originintent of the Constitution, and Western civilization.

of a child during the consulship of Pollio in 40 B.C., who

will usher in a new Golden Age, was read by some as a pagan

prophecy of the birth of the Messiah, a matter that drew

the interest of the emperor Constantine. In an anonymous

medieval hymn, St. Paul mourns at Virgil’s tomb.

Returning to Virgil’s life

and times, we would

expect that the Aeneid

would be an intensely patriotic celebration of

Rome and Augustus Caesar, whose triumph brought peace

to Rome after decades of civil violence. The epic can and

has been read that way. The ancient commentator Donatus

stated that Virgil’s task was to show Aeneas as the worthy

ancestor of Augustus. He contended that the Aeneid was

written in the emperor’s honor.

And why should it be otherwise? As a child, Virgil had

experienced a conspiracy under Catiline to overthrow Rome,

had seen a citizen army cross the Rubicon to make war

against Rome itself, had lost his farm in land conscations,had seen Italy’s roads dangerous with highwaymen. Then

came the Augustan Peace and a First Citizen who legislated

to restore the old virtues of Rome: military discipline,

marriage, child-rearing.

But it was not that simple, and Virgil’s mind was not simple.

Octavian, on his way to power and his place in history as

Augustus Caesar, was known for his ruthlessness. With his

colleagues in the Triumvirate, he had published proscription

lists, rewarding anyone who brought the heads of their

political enemies, among them Cicero himself.

The Roman Republic was gone and liberty was dead.

Augustus would exile the poet Ovid for offending him.

Under the next emperor, Tiberius, informers would cause

the suicide and burn the books of a historian merely for

praising the long-dead Brutus and Cassius.

Mirror of Ambiguities

The hero of Virgil’s Aeneid is as complex as Virgil’s era, a

mirror of the ambiguities of human experience. Observe

the end of the story: The hero Aeneas, ancestor of Augustus,

has proposed a truce with Turnus, leader of the native forces

waging war against Aeneas as a foreign usurper. Dominionand the hand of Lavinia, the woman that both men have

sought, will be determined by their single combat.

But Turnus’ troops treacherously break the truce and

wound Aeneas, and Turnus returns to random slaughter

until cornered by Aeneas. At this crucial moment, Aeneas

wounds his enemy and brings him to his knees, pleading for

his life:

“Use the portion given to you: I deserve my fate. I have no

complaint. But if any thought of a grieving parent can touch

you still (and such you had in Anchises, the author of your line),

pity Daunus, my aged father. Return me to my kin–or even as

a corpse drained of life, if you prefer. You have conquered, and

my people see me in defeat, my hands stretched out, begging.

Lavinia is yours, your wife. Do not press further in hatred.”

What should the hero do? The action pauses:

He stood ferocious in all of his weaponry, eyes darting–and stayed his hand. And now more and more as he hesitated

Turnus words began to move him.

Aeneas has grounds for revenge. Turnus killed in ba

Aeneas’ young friend Pallas and wears the spoils he stripp

from the brave youth. Turnus is a truce breaker; he driv

a chariot with the heads of his slain enemies dangling fro

its rails. Should not Aeneas clear this monster from the la

destined to be Rome?

‘Spare the Defeated,’ Anchises Urged

Aeneas is not, however, supposed to act like the rag Achilles from Homer’s Iliad , aptly described by C. S. Lew

as “little more than a passionate boy.” When Aeneas met t

ghost of his father Anchises—the father whom he carri

out of the burning wrack of Troy as the old man clutch

in his arms the household gods—the paternal admoniti

for Aeneas’ burden and Rome’s destiny was clear:

“You, Roman, remember to rule the nations under your

dominion, for these will be your arts, and impress morality upon

the peace: to spare the defeated and to disarm the arrogant.” (6.

851-853)

Note that Anchises does not address Aeneas by his name,

as “son,” but as “Roman”: Virgil makes him speak for tim

to come. Aeneas’ great heir, moreover, Augustus, proud

(though not truthfully) inscribed on the monument of

achievements:

I often waged war, civil and foreign, by land and sea, throughout

the world, and as victor I spared all citizens who asked for

mercy. I preferred to preserve, rather than eliminate, foreign

nations whenever I could safely pardon them. (Res Gestae

Divi Augusti 3).

entennial Review, May 2010 ▪ 2

The Roman Republic

was gone and liberty

was dead.

8/9/2019 CR May10 Pages

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cr-may10-pages 3/4

DUSTING OFF THE CLASSICS

By Megan DeVore

“Let the clever ones learn Latin as anhonor and Greek as a treat.” WinstonChurchill’s words fall out of cadence with today’s apathy toward the ancient world. We are told the past is dead andgone or relegated to the ivory tower,along with its irrelevant languages.

I beg to differ—and a recent surge inClassical studies suggests I’m not alone. Classics stu-dents enjoy innumerable practical benets: Familiarity with Latin or Greek produces an erudite vocabulary (increasing job prospects), enhances performance onstandardized exams, and increases comprehension of modern languages. Knowledge of ancient history en-ables recognition of allusions in contemporary literature,political systems, military affairs, and phrases such as “aSisyphean task.”

At Colorado Christian University, however, the abovelitany does not sufce. We do not teach the Classicsmerely to produce students with skill in trivia or lucrativejobs. We do so out of the conviction that humans liveinextricably in the dimension of time. We are marked by our past and move in a present which once was the fu-ture. Amnesia on the communal, institutional, or nationallevel is devastating. If we are ignorant of our history —or, worse, twist history to suit present purposes—weset upon dangerous, egomaniacal paths into a nebulousfuture.

Additionally, as a professor of Greco-Roman history and

early Christian theology, I consistently emphasize thatour Judeo-Christian faith exists today where it began mil-lennia ago: in historical context. An understanding of theClassical world brings a lively depth of insight into ourScriptures, theologies, practices, and future directions. The ancient world is part of us—isn’t this thrilling? No wonder, then, at Churchill’s words: Learning the Classicstruly is an honor and a treat. ■

Megan DeVore has taught in the School of

Theology at Colorado Christian University since

2006. She holds an M.A. in Classics from the

University of Colorado and is completing her Ph.D.

in theology at the University of Wales, U.K.

V o i c e s o f C CU We left Aeneas, staying his hand from slaughter. Maybe the

ending should be:

And the Roman hero, with the gaze of friendship, stretched out

his hand to the Rutulian and lifted him up, reassuring him in

his supplication and rejoicing to bestow peace upon Latium.

But I wrote those silly lines, not Virgil: Worse than their

clumsy versication is the violence they do to the subtle

thinking of the poet.

What really happens is that Aeneas sees that Turnus is wearing the spoils he stripped from Pallas. Furiis accensus et

ira terribilis, “on re with fury and terrible in his rage,” he

shouts that Pallas is exacting punishment from Turnus and

plunges his sword into Turnus’ heart. With a groan Turnus

dies and the epic abruptly ends.

The end of the Aeneid has troubled readers since antiquity.

An anonymous biographer in the 4th century asserted that

Virgil intended an epic of not twelve, but 24 books. Maffeo

Vegio in the 1400s actually wrote a thirteenth book of the

Aeneid . These absurdities help illustrate that Virgil has given

us a profoundly disturbing ending. And, just as Virgil was

Dante’s guide through Hell and Purgatory, so he is going to

make us look into our hearts.

What Kind of Hero?

The end of the Aeneid , moreover, is only the most startling

reversal of expectation about the hero. We should have

been prepared for it by Book 10, where Aeneas, fresh from

the grief of Pallas’ death, slays two suppliants who fall at his

knees, and takes captives to be used as human sacrices at

Pallas’ funeral. What kind of hero did Virgil give us?

Aeneas is the most perfect of men. He introduces himself,

without irony, “I am Aeneas, the pious.” C.S. Lewis captures

the character of Aeneas with a few bold strokes. Quoting

Virgil, “the mind remains unshaken while the vain tears fall,”

Lewis observes that Aeneas “is compelled to see something

more important than happiness.”

Lewis notes vocation in Virgil, and with it, duty. Aeneas

loves Dido, but when divinity reminds him of duty, there is

no hesitation. When he meets her ghost in the underworld,

after she takes her own life, there is no comfort Aeneas can

give or take. He can only resume his duty.Burden of Conscience

Yet Aeneas fails in the end. At the beginning of the Aeneid

(1.294-96), Jupiter, king of the Roman gods, envisioned

a Roman world where the personication of rage, Furor

Impius, is bound and chained. But Aeneas now slays his foe

“kindled with furor .” He does not execute Turnus as a danger

to the rational, ordered world Rome must build: He kills

him in angry revenge. Roman Stoicism had doctrine about

appropriate wartime behavior. Cicero wrote that ghting

for personal gratication, rather than for public safety, is

Centennial

Institute

Colorado Christian University

Centennial Review, May 20

repugnant to humanity ( On Duties 1.62). For Cicero, even

in the heat of mortal combat, anger has no place ( Tusculans

4.43). Utopian, surely, but this was the paradigm Aeneas

was expected to exemplify.

Oxford scholar Oliver Lyne, one of the most inspired

readers of Virgil, wrote: “If Aeneas, the son of a goddess,

the hero of the epic, cannot ‘succeed,’ then perhaps no

one can. With great realism Vergil shows how an Aeneas,

who is genuinely in sympathy with Stoic imperial ideas

8/9/2019 CR May10 Pages

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cr-may10-pages 4/4

Centennial Review

May 2010

Centennial Institute

Colorado Christian University 8787 W. Alameda Ave.Lakewood, CO 80226

Return Service Requested

entennial Review, May 2010 ▪ 4

of the appropriate methods

of warfare cannot, under the

relentless pressure of human

reality, always uphold them.”

Admonished and chastened,

if we listen to Virgil, we grow.

In the Georgics , Virgil warned

that all things collapse to ruin

and are swept away: humanity

rows against a hostile tide, and

with the relaxation of effort is

swept headlong away (I. 199-

203). In the world of war and

empire, the temptations are

yet greater, the consequences more dire. As C.S. Lewis toldus, Virgil bids us to take up the burden of our conscience

and our responsibility. Yearn as we might for childhood,

Virgil summons us to moral maturity and to the challenge of

civilization. ■

The Aeneid : A Beginning Bibliography

Jasper Grifn, Virgil (Oxford, 1986).

C.S. Lewis, A Preface to Paradise Lost (Oxford, 1954).

R.O.A.M. Lyne, Further Voices in Vergil’s Aeneid (Oxford, 1987).

Ronald Syme, The Roman Revolution (Oxford, 1939).

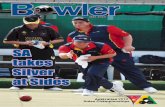

Aeneas, wounded by an arrow, with

his son and the goddess Venus

(Fresco from Pompeii, A.D. 79)

Centennial Institute and 710 KNUS Present

WESTERN CONSERVATIVE SUMMIT 2010Friday, July 9 – Sunday, July 11

Marriott South, Lone Tree, Colorado

Theme: “Right Turn, Right Now”

Conferees: Leaders in Business, Government,

Politics, Education, Faith, and Media,

from Fifteen States, California to Kansas

Invited Speakers Include:

Michele Bachmann Tom Coburn

Congresswoman Senator

General Jerry Boykin Arthur Brooks

U.S. Army (Retired) American Enterprise Institute

Brit Hume Foster Friess

Fox News Philanthropist & Businessman

Michael Barone James Dobson

Washington Examiner Broadcaster

Dick Morris Dennis Prager

Fox News Salem Radio

For information, reservations, and sponsorship opportunities,

e-mail [email protected] or call 303.963.3424

Civilization and Savagery:

Virgil For Today

By Michael Poliakoff Aeneas is the most perfect of

men. Yet he fails in the end. Who

then can succeed? If we listen to

Virgil, we grow.