Compensating Variation, Equivalent Variation, Consumer Surplus, Revealed Preference

-

Upload

hishamsauk -

Category

Documents

-

view

1.207 -

download

0

Transcript of Compensating Variation, Equivalent Variation, Consumer Surplus, Revealed Preference

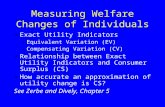

MICROECONOMICS: COMPENSATING VARIATION, EQUIVALENT VARIATION, CONSUMER SURPLUS, REVEALED PREFERENCE

THE PROBLEM If there is a shift in demand for any reason (a tax,

health scare, change in preferences etc.) we want to be able to judge whether the consumer is better or worse off.

One possible way is to simply plug the new quantities of the chosen goods back into the utility function: Problem is that UTILITY IS ORDINAL MEASURE:

One can’t compare utility levels between individuals. The extent of the difference between utility levels is

meaningless.

We want a measurable, comparable, monetary value of the change in welfare – this can be given in three forms: COMPENSATING VARIATION IN INCOME EQUIVALENT VARIATION IN INCOME CHANGE IN MARSHALLIAN CONSUMER SURPLUS

COMPENSATING VARIATION Consider a consumer with an

expenditure function of E(Px,...,U1).

When there is an increase of Px to Px’, the amount of income compensation required to keep the consumer on the original utility function U1 will be:

CV = E(Px’,...,U1) – E(Px,...,U1)

This is shown on the diagram to the right, where red is the initial situation and blue is after the price change.

However, due to problems observing people’s utility functions, we can rarely observe the CV via this method – Instead one has to use a Compensated Demand Curve (shown on a later slide).

E(Px’,...,U1)

E(Px,...,U1)

CV

U1

E(Px,...,U1)

E(Px’,...,U1)

X

Y

EQUIVALENT VARIATION Consider a consumer with

Expenditure function E(Px,...,U1).

Price of X rises, as before, from Px to Px’.

This puts the consumer on a LOWER level of utility – U2.

Equivalent Variation is the amount of income we would have to remove, at original prices, to put the consumer on U2.

EV = E(Px’,...,U2) – E(Px,...,U2)

EV can also be shown using a Compensated demand curve (later slide), but considers a curve at the NEW utility level, rather than the old one (CV).

E(Px’,...,U2)

E(Px,...,U2)

EV

U1

E(Px,...,U2)

E(Px’,...,U2)

X

Y

U2

MARSHALLIAN CONSUMER SURPLUS Equivalent Variation Vs. Compensating Variation: BOTH measure the distances of the two

indifference curves, but will depend on the slopes of the budget constraints.

In general EV ≠ CV. That is, The amount of money a consumer is willing

to give up to avoid a price change is not equal to the amount of money a consumer needs to be compensated for a price change.

Marshallian Consumer Surplus is the area below the Marshallian demand curve and above the market price; it shows what an individual would pay for the right to make voluntary transactions at that price.

MARSHALLIAN CONSUMER SURPLUS VS CV VS EV In the case of a PRICE

RISE: CV = Area under the

ORIGINAL compensated demand curve. CV = Px’.b.c.Px

EV = Area under the NEW compensated demand curve. EV = Px’.a.d.Px

Δ MCS = Area under the Marshallian Demand Curve. Δ MCS = Px’.a.c.Px

For a PRICE RISE: CV > Δ MCS > EV

For a PRICE FALL: EV > Δ MCS > CV

Px

X

Px

Px’

XX’

x(Px,...,M)

xc(Px,...,U1)

xc(Px,...,U2)

a b

cd

REVEALED PREFERENCE We can’t directly observe preferences, making

the past analysis rather hypothetical. However, we can observe consumer behaviour

and the bundles of goods that they purchase. We can use this to indirectly reveal their

preferences.

Assumptions: Preferences are constant over the observed period. Consumer uses all their available income. For each price and income only one bundle is

chosen. There exists only one price and income

combination at which each bundle is chosen.

REVEALED PREFERENCE Graphically, revealed

preference theory can be shown as in the diagram.

If initially the consumer faces income ‘M’ and chooses ‘B’ over ‘A’, then B has been revealed preferred to A.

The only time when A would be chosen would be either when B was unavailable (M’) or choosing B would violate one of the assumptions (M’’ – not using full income).

M

M’

M’’

AB

Y

X

REVEALED PREFERENCE – WARP & SARP WEAK AXIOM of REVEALED PREFERENCE

(WARP) If X and Y are two bundles that are both feasible and

affordable to a consumer and X is chosen over Y, then X has been DIRECTLY REVEALED PREFERRED to Y.

Y can NEVER be directly revealed preferred to X.

STRONG AXIOM of REVEALED PREFERENCE (SARP) If there are ‘n’ goods; A,B, ..., n, and A > B > C > ... >

n, then A > n. A is INDIRECTLY REVEALED PREFERRED TO ‘n’, and ‘n’

can NEVER be indirectly revealed preferred to A. SARP is essentially an expansion of WARP to

indirectly reveal prefer goods, you must use directly revealed preferred goods as steps along the road.

REVEALED PREFERENCE Solving Questions: When faced with a question on

WARP, draw a matrix of prices and bundles.

For example, two goods ‘X’ and ‘Y’. In period 1, Px = 4, Py = 3; In period 2 Px = 3, Py = 3. The consumer buys [X=2, Y=1] – BUNDLE 1 - in period 1 and [X=1, Y = 2] – BUNDLE 2 - in period 2. Is this consistent with WARP?

NO! The matrix shows why. Call the two Bundles ‘B1’ and B2’, and

the price combinations in the two periods P1 and P2.

The Matrix shows the total cost of the two bundles at the respective price combinations.

In Period 1, B1 has been directly revealed preferred to B2.

However, in period 2, BOTH ARE AFFORDABLE, yet B2 is still chosen.

This implies B2 has been directly R.P to B1, which violates WARP.

2|1

2

1

99

1010

BB

P

P