Sweet related visual cue reactivity fades out until adulthood

Comparing alcohol cue-reactivity in treatment-seekers ...

Transcript of Comparing alcohol cue-reactivity in treatment-seekers ...

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found athttps://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=iada20

The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol AbuseEncompassing All Addictive Disorders

ISSN: 0095-2990 (Print) 1097-9891 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/iada20

Comparing alcohol cue-reactivity in treatment-seekers versus non-treatment-seekers withalcohol use disorder

Alexandra Venegas & Lara A. Ray

To cite this article: Alexandra Venegas & Lara A. Ray (2019): Comparing alcohol cue-reactivity intreatment-seekers versus non-treatment-seekers with alcohol use disorder, The American Journalof Drug and Alcohol Abuse, DOI: 10.1080/00952990.2019.1635138

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00952990.2019.1635138

Published online: 11 Jul 2019.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 52

View related articles

View Crossmark data

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Comparing alcohol cue-reactivity in treatment-seekers versus non-treatment-seekers with alcohol use disorderAlexandra Venegas a and Lara A. Raya,b

aDepartment of Psychology, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA; bDepartment of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, Universityof California, Los Angeles, CA, USA

ABSTRACTBackground: Recent studies have examined the distinction between treatment-seekers and non-treatment-seekers with alcohol use disorder (AUD) with a focus on treatment development.Objectives: To advance our understanding of treatment-seeking in clinical research for AUD, this studycompares treatment-seekers to non-treatment-seekers with AUD on alcohol cue-reactivity (CR).Methods: A community sample (N = 65, 40% female) of treatment-seeking (n = 32, 40.6% female)and non-treatment-seeking individuals (n = 33, 39.4% female) with a DSM-5 diagnosis of moder-ate-to-severe AUD completed a laboratory CR paradigm. Analyses compared the two groups onsubjective alcohol craving, heart rate, and blood pressure after the presentation of water cues andalcohol cues.Results: Mixed-design analyses of variance revealed a main effect of treatment-seeking status (i.e.,group; p = .02), such that treatment-seekers reported higher levels of subjective craving acrossboth water (p = .04) and alcohol (p = .03) cue types. However, analyses did not support a group ×cue type interaction effect (p = .9), indicating that treatment-seekers were not more cue-reactive.Group differences in craving were no longer significant when controlling for AUD severity. Onblood pressure and heart rate, there was no significant effect of cue type, group, or cue type ×group (p’s > 0.13).Conclusion: These findings suggest that while treatment-seekers report higher levels of subjectivecraving than non-treatment-seekers, they are not more cue-reactive. Under the framework ofmedications development, we interpret these null findings to indicate that non-treatment seekingsamples may be informative about CR and therefore, medication-induced effects on CR.

ARTICLE HISTORYReceived 18 December 2018Revised 18 June 2019Accepted 18 June 2019

KEYWORDSAlcohol; craving;cue-reactivity;treatment-seeking;behavioral pharmacology

Introduction

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a chronic, relapsing condi-tion, characterized by continued use despite harmful med-ical, psychological, and social consequences. Despite AUDbeing highly prevalent, treatment rates remain remarkablylow. Among those with 12-month and lifetime diagnoses ofAUD, only 7.7% and 19.8%, respectively, sought treatmentfrom 2012–2013 (1). Furthermore, it has been estimatedthat there is an average lag of approximately 8 yearsbetween the age of onset and age at first treatment (2).Greater severity of substance use disorders isa predominant factor associated with treatment-seeking(3,4) and individuals with current AUD are more likelyto endorse a desire for AUD treatment if they are older,female, report higher levels of social impairments, andfailed efforts to stop or cut down on drinking (5–7).Similarly, it has been demonstrated that treatment-seekers with AUD have higher rates of negative social

consequences and higher levels of drug use and psychiatricseverity, than non-treatment-seekers (8). Taken together,these studies not only identify specific traits that differacross these two samples, but also highlight their clinicalsignificance.

The distinction between treatment-seekers and non-treatment-seekers with AUD is pertinent in both researchand clinical contexts and is particularly important inAUD treatment development. For instance, behavioralpharmacology trials represent a necessary first step inestablishing preliminary safety and efficacy of novel med-ications and are largely conducted in non-treatment-seeking samples (9). However, it is often observed thatfindings from human laboratory studies do not consis-tently and reliably carry over in clinical trials (10,11).Although the exact cause of discrepant findings betweenhuman laboratory studies and randomized controlledtrials remains ambiguous, one plausible explanation isthat treatment-seekers respond differently to medications

CONTACT Lara A. Ray [email protected] Department of Psychology, University of California Los Angeles, 1285 Franz Hall, Box 951563, LosAngeles, CA 90095–1563

THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF DRUG AND ALCOHOL ABUSEhttps://doi.org/10.1080/00952990.2019.1635138

© 2019 Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

for AUD than non-treatment-seekers. This hypothesis issupported by the nicotine and tobacco literature, whichsuggests that motivation to quit smoking significantlyinfluences the efficacy of medications for smoking cessa-tion, such that nicotine replacement therapy (i.e., nicotinepatch), was found to increase abstinence in treatment-seekers, but had no significant effect in those who werenot currently seeking treatment (12,13). Moreover, ourgroup (6) and others (7) have recently identified a host ofclinical variables that distinguish treatment-seekers fromnon-treatment-seekers, including tonic craving. As such,examining possibly inherent differences between treat-ment-seeking and non-treatment-seeking samples interms of experimental and clinical paradigms for AUDis warranted.

The cue-reactivity (CR) paradigm was developed toevaluate the urge to drink in response to alcohol-relatedstimuli, as alcohol cue-exposure in the laboratory canmimic real-world situations in which alcohol is readilyavailable, artificially inducing a conditioned response toalcohol cues (14). This response is a viable target toAUD treatment, as cue-induced alcohol craving hasbeen shown to be predictive of treatment outcome(14). Studies have used CR in the context of treatmentand found that salivary response to alcohol cues duringdetoxification predicted a higher frequency of drinkingdays during the 3-month follow-up (15)However, giventhat human laboratory CR trials have been comprisedof non-treatment-seeking samples, the inclusion of(and comparison to) treatment-seekers is a necessarynext step in this line of research.

To that end, the present study compared treatment-seekers to non-treatment-seekers with AUD ona human laboratory assessment of alcohol CR. Basedon the finding that treatment-seekers report higherlevels of tonic craving (6), we hypothesized that treat-ment-seekers would display higher levels of alcohol CRcompared to non-treatment-seekers, over and abovethe effects of AUD severity. Lastly, exploratory analysesconsidered a dichotomous definition of craver versusnon-craver, as proposed by Mason and colleagues (16).

Participants and methods

Participants

A community sample of treatment-seeking and non-treatment-seeking individuals reporting current pro-blems associated with alcohol use was enrolled in thestudy (N = 65). Inclusion criteria for the study were: (i)age between 21 and 50 years; (ii) fluency in the Englishlanguage; and (iii) meet current (past 3-month) DSM-5diagnostic criteria for moderate or severe AUD.

Exclusion criteria were: (i) currently in treatment foralcohol use or history of treatment in the 30 days pre-ceding the study visit; (ii) lifetime DSM-5 diagnosticcriteria for a bipolar or psychotic disorder; (iii) positiveurine toxicology screen for any drug (other than can-nabis), as measured by Medimpex United Inc. 10 paneldrug test; (iv) blood alcohol concentration (BAC) of0.000 g/dl at the time of the study visit, as measured bythe Dräger Inc. Alcotest® 6510; (v) score of 10 or higheron the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment forAlcohol Scale – Revised (CIWA-Ar (17);) and (vi)current use of psychoactive medications. The twogroups of treatment-seekers (n = 32) and non-treatment-seekers (n = 33) were identified on thebasis of their self-reported desire for treatment, as indi-cated by their answer to the following question: “Forthis study, we are looking for people who are seekingtreatment for their alcohol use (would like help withtreatment planning) as well as people who are not.Which category best describes you?” Their indicationof treatment-seeker or non-treatment-seeker informedtheir participation in the study as described below.

Screening procedures and measures

All study procedures were approved by the Universityof California, Los Angeles Institutional Review Board,and all participants provided written informed consentafter receiving a full explanation of the study proce-dures. Participants were recruited via online and printadvertisements. Interested individuals called the labora-tory and completed a phone interview for preliminaryeligibility.

Following telephone screening procedures, eligible par-ticipants completed one in-person screening/assessmentvisit, lasting approximately 1 hour. This assessment visitwas comprised of individual differences measures, includ-ing questionnaires designed to assess demographics, past-month substance use, AUD severity, baseline craving, andreadiness to change drinking patterns. The following mea-sures were administered: (1) Timeline Follow-Back (TLFB;(18)); (2) Alcohol Dependence Scale (ADS; (19)); (3)Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale (OCDS; (20); (4)Penn Alcohol Craving Scale (PACS; (21)); (5) Stages ofChange Readiness and Treatment Eagerness Scale(SOCRATES; (22)); and (6) Contemplation Ladder (23).

A total of 314 individuals completed a screeninginterview over the phone, of which 113 individualswere eligible and came to the laboratory for an in-person screening visit. Of the 113 individuals evaluatedin person, 65 of them were deemed eligible for thestudy. Reasons for exclusion after the in-person assess-ment included not meeting diagnostic criteria for

2 A. VENEGAS AND L. A. RAY

moderate-to-severe AUD, BAC greater than 0.000 g/dl,and testing positive on the urine toxicology screen fordrugs other than marijuana. Immediately following thein-person assessment, eligible participants (N = 65)completed an alcohol cue-exposure session. After thecue exposure, all participants discussed their responsesto the alcohol cues with a trained counselor.Treatment-seekers also completed a treatment planningsession with the counselor, in which treatment optionswere discussed. A summary of screening and experi-mental procedures is provided in Figure 1.

Alcohol cue-reactivity (CR) procedures andmeasures

Alcohol CR followed well-established procedures(24,25). Sessions began with a 3-minute relaxation per-iod. Then, participants held and smelled a glass ofwater for three minutes to control for the effects ofsimple exposure to any potable liquid. Next, partici-pants held and smelled a glass of their preferred alco-holic beverage and were asked to recall sensory andpsychological memories associated with their alcoholuse (e.g., how one typically feels right before beginningto drink, one’s mood prior to drinking, the location inwhich one typically drinks, and with whom one typi-cally drinks). Order was not counterbalanced, due tocarryover effects that are known to occur (24).Participants who self-identified as cigarette smokerswere allowed a smoke break 15 minutes prior to andimmediately after the CR assessment to avoid thepotential confounding effects of nicotine withdrawal.The following measures were collected before andafter the presentation of the water and alcohol cuesduring the CR procedure:

Alcohol urge questionnaireThe Alcohol Urge Questionnaire (AUQ (26);) is an8-item scale in which subjects rated their craving foralcohol at the present moment. Participants rated theirurge to drink prior to beginning the alcohol CR proce-dure, after the presentation of the water cue, and afterthe presentation of the alcohol cue, on an 11-pointLikert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to“strongly agree.” The AUQ has demonstrated highinternal consistency in alcohol human laboratory stu-dies (27).

Physiological indicatorsVital signs including heart rate and blood pressure weremeasured using an Omron BP785N Automatic BloodPressure Monitor. Vital signs were not measured con-tinuously during each period of the CR procedure, butinstead were measured before beginning the procedure,once following the presentation of the water cue, andonce more following the presentation of the alcoholcue, resulting in three measures of physiological reac-tivity. Given that we used a single time-point recordingmethod, there was no tool for checking for motionartifacts.

Treatment planning session

All participants who completed the CR paradigmmet witha trained study counselor, supervised by a licensed clinicalpsychologist to discuss their responses to the alcohol cues.Those who self-identified as treatment-seeking participatedin a treatment planning session with the study counselor.The counseling session followed standardized proceduresdeveloped for this study. The counselor began by providingthe participant with feedback on answers to the various

Figure 1. Overview of screening and experimental procedures.

THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF DRUG AND ALCOHOL ABUSE 3

questionnaires from the screening portion of the visit(drinking and drug use patterns, AUD diagnosis, familyhistory of alcohol use, and withdrawal and depressivesymptoms). Next, the counselor reviewed the participant’shistory of alcohol treatment and sought to identify barriersto treatment access. Lastly, the counselor reviewed treat-ment options with the participant, including the partici-pant’s primary care provider, self-help groups, and localclinics. The counselor provided all participants with the“Rethinking Drinking” (28) pamphlet and addressed anyquestions or concerns.

Power analysis

Given that no preliminary data were available for effectsize estimation, the current study was powered to detecta medium effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.50). A power analysiswas conducted according to Cohen’s guidelines to deter-mine the sample size needed to achieve a power ≥ 0.80(i.e., 80%) at an alpha level of 0.05. Using the programG*Power version 3.1.2 and selecting the repeated mea-sures analysis of variance (ANOVA), between-subjectsdesign, with alpha = 0.05 and f = 0.25, we arrived ata total of 64 participants (32 treatment-seekers and 32non-treatment-seekers).

Data analysis plan

A series of mixed-design (repeated-by-between-subjects)analyses were conducted using PROC GLM in SASStatistical Software Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc.,Cary, N.C.). Specifically, we conducted general linearmodel analyses in which group (treatment-seeker versusnon-treatment-seeker) was a two-level between-subjectsfactor and cue (water cue versus alcohol cue) was a two-level within-subjects factor. The dependent measureswere alcohol craving, as measured by self-reported crav-ing on the AUQ (primary outcome), and physiologicalresponse to cues (secondary outcome: heart rate andblood pressure). Based on clinical differences reportedbetween treatment-seekers and non-treatment-seekers(6,7), subsequent analyses compared treatment-seekersto non-treatment-seekers on cue-induced subjectivecraving after adjusting for age and ADS score.

Exploratory analysesWe sought to explore whether treatment-seekers weremore likely to be classified as “cravers” than non-treatment-seekers. To do so, we followed the classifica-tion proposed by Mason and colleagues (16), wherebyan individual was considered cue-reactive if his or her“strength of craving” score was one standard deviationgreater for alcohol than for water cues on the Visual

Analog Scale (VAS), corresponding to an increase of 3VAS rating scale points. In the present study, an indi-vidual was considered cue-reactive if his or her cravingrating per the AUQ was at least 6 points or higher foralcohol than for water cues. To test the dichotomouscraving variable, we conducted a chi-square test toexamine whether treatment-seekers were more likelyto be classified as cravers than non-treatment-seekers.

Results

Sample characteristics

Sixty-five participants who completed the entire studywere included in the statistical analyses reported herein.Sample characteristics are reported in Table 1, includ-ing alcohol use quantity and frequency, baseline levelsof craving, and AUD severity. As shown in Table 1, ofthe 65 participants enrolled in the study, 40% (n = 26)met current diagnostic criteria for moderate AUD,whereas 60% (n = 39) met diagnostic criteria for severeAUD.

As shown in Table 1, analyses comparing treatment-seekers and non-treatment-seekers on demographic andclinical variables revealed that treatment-seekers wereolder, had higher OCDS and PACS scores (p’s < 0.05),marginally higher ADS scores (p < .053), and were morelikely to report cigarette smoking (p < .05).

As expected, given the treatment-seeking constructitself, treatment-seekers reported significantly higherlevels of motivation for change, as indexed by higherreadiness to change (i.e., a higher score on theContemplation Ladder), greater recognition of alcoholproblems and lower ambivalence subscales on theSOCRATES (p’s < 0.05).

Effect of treatment-seeking status on alcohol cuereactivity

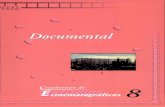

Cue-induced subjective cravingAnalyses revealed a main effect of cue type on cue-induced subjective craving, such that levels of self-reported subjective craving (i.e., AUQ score) were higherfollowing the presentation of alcohol cues than after thepresentation of water cues (F(1, 64) = 35.0, p < .0001).Analyses also revealed a main effect of group (defined astreatment-seeking status; F(1, 63) = 5.3, p < .05), suchthat treatment-seekers displayed higher levels of subjec-tive craving than non-treatment-seekers following boththe water and alcohol cues. However, analyses didnot yield a group × cue type interaction effect (F(1,63) = 0.03, p = .86). These results are presented inFigure 2.

4 A. VENEGAS AND L. A. RAY

There were observed group differences with regardto age and ADS score (Table 1), such that treatment-seekers were significantly older (p < .05) and reportedmarginally greater ADS scores (p < .053), which wasexpected given prior research. Both of these variableswere tested as covariates in separate mixed-designANCOVA models. When comparing treatment-seekers to non-treatment-seekers on cue-induced sub-jective craving, adjusting for both of these variables inseparate models, the effect of treatment-seeking statuswas no longer significant after controlling for ADSscore (p = .13); however, the effect of treatment-seeking still remained after controlling for age(p < .05). This finding suggests that treatment-seekingstatus and measures of AUD severity overlapped in thissample, despite our efforts to match groups on severity.

Cue-induced heart rate and blood pressureDifference scores for measures of heart rate and bloodpressure were calculated by subtracting the valuesobtained during the relaxation period from the values

obtained following the presentation of the water andalcohol cues, respectively. ANOVAs did not reveal sig-nificant effects of cue on any physiological indicators ofcue-reactivity, including cue-induced heart rate (F(1,64) = 0, p = .97), systolic blood pressure (F(1, 64) = 2.4,p = .13), or diastolic blood pressure (F(1, 64) = 0, p = .95).Similarly, although analyses yielded a significant effect ofgroup on cue-induced heart rate (F(1, 63) = 4.1, p < .05),they did not yield any significant effects of group onsystolic blood pressure (F(1, 63) = 0.7, p = .42) or diastolicblood pressure (F(1, 63) = 0.04, p = .84). Lastly, there wereno significant group × cue interaction effects on cue-induced heart rate (F(1, 63) = 0.3, p = .61), systolicblood pressure (F(1, 63) = 1.0, p = .33), or diastolicblood pressure (F(1, 63) = 0.2, p = .63).

Exploratory analyses

Across groups, 41.5% (n = 27; 14 non-treatment-seekers,13 treatment-seekers) of individuals were considered to becue-reactive. Chi-square analyses comparing the

Table 1. Sample characteristics and group differences.

Variablea

Treatment-Seekers(n = 32)

M(SD) or n(%)

Non-treatment-Seekers(n = 33)

M(SD) or n(%)

Full Sample(N = 65)

M(SD) or n(%) t or χ2 p

Age 37.28 (7.78) 30.94 (8.42) 34.06 (8.65) −3.15 .002*Gender

Female (%) 13 (40.6%) 13 (39.4%) 26 (40.0%) 0.010 .92Hispanic/Latino

Yes (%) 9 (28.1%) 6 (18.2%) 15 (23.1%) 0.91 .34ADSb

OCDSc20.22 (8.42)20.25 (8.97)

16.18 (6.80)15.33 (7.52)

18.17 (8.40)17.75 (8.57)

−1.98–2.40

.054

.02*Baseline AUQd

CIWA-Are18.06 (12.12)1.06 (2.14)

13.27 (10.77)1.27 (2.52)

15.63 (11.62)1.17 (2.32)

−1.690.36

.098.72

PACSf 18.91 (7.10) 13.94 (6.84) 16.38 (7.35) −2.87 0.006*SOCRATESg: Recognition 25.91 (5.88) 19.79 (6.46) 22.80 (6.86) −3.40 <.001*SOCRATESg: Ambivalence 15.84 (3.45) 12.42 (3.22) 14.11 (3.73) −4.13 <.001*SOCRATESg: Taking Steps 25.19 (8.86) 22.88 (6.94) 24.02 (7.96) −1.17 .25Contemplation Ladder 6.59 (2.14) 5.18 (2.53) 5.88 (2.43) −2.43 .02*AUD Diagnosish

Moderate (%) 12 (37.5%) 14 (42.4%) 26 (40.0%) 0.16 .69Severe (%) 20 (62.5%) 19 (57.6%) 39 (60.0%)

Drinking Daysi 24.31 (7.52) 20.58 (8.80) 22.42 (8.35) –1.84 .070Drinks/Drinking Dayi 7.72 (5.62) 6.09 (4.15) 6.89 (4.96) –1.33 .19Binge Drinking Daysi 14.31 (10.26) 11.52 (9.17) 12.89 (9.75) –1.16 .25Smoker

Yes (%) 24 (75.0%) 17. (51.5%) 41 (63.1%) 3.85 .0498Cannabis useri

Yes (%) 16 (50.0%) 22 (66.7%) 38 (58.5%) 1.86 .17BDI-IIj 15.25 (11.83) 17.97 (11.30) 16.63 (11.55) 0.95 .35BAIk 15.31 (13.11) 12.18 (9.73) 13.72 (11.54) –1.09 .28

aStandard deviations appear within parentheses for continuous variables. Percent of group (i.e., treatment-seekers or non-treatment-seekers)appear within parentheses for categorical variables.

bAlcohol Dependence Scale (ADS)cObsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale (OCDS)dAlcohol Urge Questionnaire (AUQ)eClinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol – Revised (CIWA-Ar)fPenn Alcohol Craving Scale (PACS)gThe Stages of Change Readiness and Treatment Eagerness Scale (SOCRATES)hCurrent (past 3 months) Alcohol Use Disorder (17) assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview DSM-5 (SCID-5).iAssessed by Timeline Follow Back (TLFB) interview for the past 30 days.jBeck Depression Inventory – II (BDI-II)kBeck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)*Asterisks denote statistically significant differences between groups (p’s < 0.05).

THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF DRUG AND ALCOHOL ABUSE 5

probability across the 2 × 2 model (cue-reactive versusnon-cue reactive; treatment-seeking versus non-treatment-seeking), indicated that there were no significant differ-ences in the likelihood of being classified as cue-reactivebetween groups, such that treatment-seekers were nomorelikely to be considered cue-reactive than non-treatment-seekers (χ2 (1, n = 65) = 0.02, p = .88).

Discussion

Results generally provided evidence for higher levels ofself-reported alcohol craving in treatment-seekers thannon-treatment-seekers. However, there was no evi-dence that treatment-seekers were more cue-reactive,contrary to our initial hypothesis. Instead, treatment-seekers displayed elevated levels of craving at baselineand following the presentation of both the water andalcohol cues and there was no support for a group ×cue interaction effect. Furthermore, after adjusting forAUD severity and measures of tonic craving (e.g.,PACS, OCDS), the effect of treatment-seeking statuswas no longer significant, suggesting that group differ-ences in AUD severity may explain the higher cravingscores that were observed in treatment-seekers.Although we attempted to match these groups onAUD severity by only including participants with mod-erate-to-severe AUD, group differences in other mea-sures of AUD severity were observed. Those clinicaldifferences in turn are consistent with previous findings

of greater AUD severity among treatment-seeking indi-viduals (6,7).

In terms of physiological indicators of cue-inducedcraving, no indices yielded significant effects of eithercue or group, such that cue-induced heart rate andblood pressure remained relatively constant acrossboth water and alcohol cues, as well as across treat-ment-seeking status. The procedures employed in thepresent study resulted in three discrete measurementsof physiological indicators of craving. Our approachconsisted of a single time-point recording, as opposedto continuous long-range assessment, which may posea limitation in that the largest physiological effect waslikely not captured within the present paradigm. Thesemethods may explain the largely null findings withregard to cue-induced heart rate and blood pressure.

Despite potential limitations of this procedure,the results obtained are in line with the mixed evi-dence regarding physiological reactivity and its rolein subjective craving. While there is evidence sug-gesting that the exposure to alcohol cues increasescraving and associated physiological arousal in absti-nent alcohol dependent individuals and social drin-kers (29–31), there is mixed evidence with regard tothe effect of alcohol-related cues on physiologicalindices (32–34). Furthermore, some work hasshown that physiological cue-reactivity is only mod-erately correlated with subjective craving (35–37), ifat all (38). It is plausible that subjective responserepresents a more reliable indicator of craving than

Figure 2. Subjective craving scores (Alcohol Urge Questionnaire; AUQ), presented with standard errors, following water and alcoholcue presentation. Double asterisks denote a significant main effect of cue, such that individuals reported significantly higher rates ofcraving following the alcohol cue compared to the water cue (p < .0001). Single asterisks denote a significant effect of group,indicating that treatment-seekers displayed higher levels of subjective craving following both the water and alcohol cues (p = .02).

6 A. VENEGAS AND L. A. RAY

the physiological measurements employed in thisstudy, which might explain these nonsignificantfindings.

Regarding the exploratory aims, analyses reflect alter-native ways in which the field has dealt with the constructof cue-reactivity (i.e., craver versus non-craver).Exploratory analyses suggested that categorizing indivi-duals as cravers or non-cravers, as recommended byMason and colleagues (16), produced the same resultssuch that treatment-seekers were no more likely to beclassified as cue-cravers than non-treatment-seekers.

The present study must be interpreted in light ofits strengths and limitations. Strengths include thatthis study was one of original data collection with thea-priori aims of comparing these two groups.Extensive efforts were made to match the two groupson severity by only allowing those with moderate-to-severe AUD to participate. Additionally, offeringa treatment-planning session to ensure commitmentto the treatment process was a strength which allowedparticipants’ involvement in the study to be matchedby their stated desire for treatment. Lastly, the exclu-sion of polysubstance users on the basis of clinicalassessments and toxicology data also bolstered theinternal validity of the study as it applies to samplewith a primary diagnosis of AUD. Study limitationsinclude the fact that we did not offer a full treatmentprogram such that the full range of treatment-seekersmay not have participated in our study. It is possiblethat treatment-seekers exhibiting the most severerange of symptoms were not well represented. Thefact that the sample was not fully matched on AUDseverity also represents a limitation, which we soughtto address statistically by adding relevant covariatesto our models.

In conclusion, our study found that although treat-ment-seekers reported higher levels of alcohol cravingduring the CR procedure, they were not significantlymore reactive to alcohol cues than non-treatment-seekers. Results from the present study have implica-tions for medications development and behavioralpharmacology for AUD. Specifically, these findingssuggest that studies of non-treatment-seekers on cue-reactivity may be translatable to treatment-seekingsamples. In other words, while clinical differencesbetween treatment-seekers and non-treatment-seekersfor AUD have been recently identified (6,7), such dif-ferences do not seem to extend to cue-reactivity per se.Nonetheless, whether individuals who are treatment-seeking (or who are motivated to change their drink-ing) are more responsive to medications for AUD thannon-treatment-seekers are remains an open question,not addressed in this study. More research is needed to

further investigate the differences between these groupsin the context of pharmacotherapy studies and deter-mine their differential response to AUD medicationstargeting cue-induced craving.

Disclosure statement

Neither author has any conflicts of interests to disclose.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of AlcoholAbuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) under grant K24AA025704;and the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) undergrants DA041226 and T32 DA007272.

ORCID

Alexandra Venegas http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6679-8954

References

1. Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, Chou SP, Jung J,Zhang H, Pickering RP, Ruan WJ, Smith SM, Huang B,et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder:results from the national epidemiologic survey on alco-hol and related conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry.2015;72:757–66.

2. Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, Grant B F.Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity ofDSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the UnitedStates: results from the national epidemiologic surveyon alcohol and related conditions. Arch GenPsychiatry. 2007;64:830–42.

3. Grella CE, Stein JA. Remission from substance depen-dence: differences between individuals in a generalpopulation longitudinal survey who do and do notseek help. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133:146–53.doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.05.019.

4. Grella CE, Karno MP, Warda US, Moore AA, Niv N.Perceptions of need and help received for substancedependence in a national probability survey. PsychiatrServ. 2009;60:1068–74.

5. Ray LA, Hart E, Chelminski I, Young D,Zimmerman M. Clinical correlates of desire for treat-ment for current alcohol dependence among patientswith a primary psychiatric disorder. Am J DrugAlcohol Abuse. 2011;37:105–10.

6. Ray LA, Bujarski S, Yardley MM, Roche DJO,Hartwell EE. Differences between treatment-seekingand non-treatment-seeking participants in medicationstudies for alcoholism: do they matter? Am J DrugAlcohol Abuse. 2017;43:703–10.

7. Rohn MC, Lee MR, Kleuter SB, Schwandt ML, Falk DE,Leggio L. Differences between treatment-seeking andnontreatment-seeking alcohol-dependent research parti-cipants: an exploratory analysis. Alcoholism.2017;41:414–20.

THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF DRUG AND ALCOHOL ABUSE 7

8. Weisner C, Matzger H. A prospective study of thefactors influencing entry to alcohol and drugtreatment. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2002;29:126–37.doi:10.1007/BF02287699.

9. Litten RZ, Falk DE, RyanML, Fertig JB. Discovery, devel-opment, and adoption of medications to treat alcohol usedisorder: goals for the phases of medicationsdevelopment. Alcoholism. 2016;40:1368–79.

10. Yardley MM, Ray LA. Medications development forthe treatment of alcohol use disorder: insights intothe predictive value of animal and human laboratorymodels. Addict Biol. 2017;22:581–615. doi:10.1111/adb.2017.22.issue-3.

11. Ray LA, Bujarski S, Roche DJO, Magill M. Overcomingthe “Valley of Death” in medications development foralcohol use disorder. Alcoholism. 2018;42:1612–22.

12. Perkins K, Lerman C, Stitzer ML, Fonte CA, Briski JL,Scott JA, Chengappa K. Development of procedures forearly screening of smoking cessation medications inhumans. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84:216–21.

13. Perkins KA, Lerman C. An efficient early phase 2procedure to screen medications for efficacy in smok-ing cessation. Psychopharmacology. 2014;231:1–11.doi:10.1007/s00213-013-3364-6.

14. Monti PM, Rohsenow DJ, Hutchison KE. Toward brid-ging the gap between biological, psychobiological andpsychosocial models of alcohol craving. Addiction.2000;95:229–36. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.95.8s2.11.x.

15. Rohsenow DJ, Monti PM, Rubonis AV, Sirota AD,Niaura RS, Colby SM, Wunschel SM, Abrams DB. Cuereactivity as a predictor of drinking among malealcoholics. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62:620.

16. Mason BJ, Light JM, Williams LD, Drobes DJ. Proof-of-concept human laboratory study for protracted absti-nence in alcohol dependence: effects of gabapentin.Addict Biol. 2009;14:73–83.

17. Sullivan JT, Sykora K, Schneiderman J, Naranjo CA,Sellers EM. Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: therevised clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alco-hol scale (CIWA-Ar). Br J Addict. 1989;84:1353–57.

18. Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back, in measur-ing alcohol consumption. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press,1992:41–72.

19. Skinner HA, Allen BA. Alcohol dependence syndrome:measurement and validation. J Abnorm Psychol.1982;91:199. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.91.3.199.

20. Anton RF, Moak DH, Latham PK. The obsessive com-pulsive drinking scale: a new method of assessing out-come in alcoholism treatment studies. Arch GenPsychiatry. 1996;53:225–31.

21. Flannery B, Volpicelli J, Pettinati H. Psychometric prop-erties of the Penn alcohol craving scale. Alcoholism.1999;23:1289–95. doi:10.1111/acer.1999.23.issue-8.

22. Miller WR, Tonigan JS. Assessing drinkers’motivation forchange: the Stages of Change Readiness and TreatmentEagerness Scale (SOCRATES). Psychol Addict Behav.1996;10:81. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.10.2.81.

23. Biener L, Abrams DB. The contemplation ladder: valida-tion of a measure of readiness to consider smokingcessation. Health Psychol. 1991;10:360. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.10.5.360.

24. Monti PM, Binkoff JA, Abrams DB, Zwick WR,Nirenberg TD, Liepman MR. Reactivity of alcoholicsand nonalcoholics to drinking cues. J Abnorm Psychol.1987;96:122.

25. Monti PM, Rohsenow DJ, Swift RM, Gulliver SB, ColbySM, Mueller TI, Brown RA, Gordon A, Abrams DB,Niaura RS, et al. Naltrexone and cue exposure withcoping and communication skills training for alco-holics: treatment process and 1-year outcomes.Alcoholism. 2001;25:1634–47.

26. Bohn MJ, Krahn DD, Staehler BA. Development andinitial validation of a measure of drinking urges inabstinent alcoholics. Alcoholism. 1995;19:600–06.doi:10.1111/acer.1995.19.issue-3.

27. Drummond DC, Phillips TS. Alcohol urges in alcohol-dependent drinkers: further validation of the alcoholurge questionnaire in an untreated community clinicalpopulation. Addiction. 2002;97:1465–72.

28. NIAAAN. Rethinking drinking: alcohol and your health.Bethesda, MD: NIH Publication; 2010. p. 15–3770.

29. Fox HC, Bergquist KL, Hong K-I, Sinha R. Stress-induced and alcohol cue-induced craving in recentlyabstinent alcohol-dependent individuals. Alcoholism.2007;31:p. 395–403.

30. Cooney NL, Gillespie RA, Baker LH, Kaplan RF.Cognitive changes after alcohol cue exposure.J Consult Clin Psychol. 1987;55:150.

31. Sinha R, Fox HC, Hong KA, Bergquist K, Bhagwagar Z,Siedlarz KM. Enhanced negative emotion and alcoholcraving, and altered physiological responses followingstress and cue exposure in alcohol dependentindividuals. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:1198.

32. Rohsenow DJ, Childress AR, Monti PM, Niaura RS,Abrams DB. Cue reactivity in addictive behaviors: the-oretical and treatment implications. Intl J Addict.1991;25:957–93.

33. Sayette MA, Shiffman S, Tiffany ST, Niaura RS,Martin CS, Schadel WG. The measurement of drugcraving. Addiction. 2000;95:189–210.

34. Niaura RS, Rohsenow DJ, Binkoff JA, Monti PM,Pedraza M, Abrams DB. Relevance of cue reactivityto understanding alcohol and smoking relapse.J Abnorm Psychol. 1988;97:133.

35. Myrick H, Anton RF, Li X, Henderson S, Drobes D,Voronin K, George MS. Differential brain activity inalcoholics and social drinkers to alcohol cues: relation-ship to craving. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:393.

36. Wrase J, Schlagenhauf F, Kienast T, Wüstenberg T,Bermpohl F, Kahnt T, Beck A, Ströhle A, Juckel G,Knutson B, et al. Dysfunction of reward processingcorrelates with alcohol craving in detoxifiedalcoholics. Neuroimage. 2007;35:787–94.

37. Mason BJ, Light JM, Escher T, Drobes DJ. Effect ofpositive and negative affective stimuli and beveragecues on measures of craving in non treatment-seekingalcoholics. Psychopharmacology. 2008;200:141–50.

38. Erblich J, Bovbjerg DH, Sloan RP. Exposure to smok-ing cues: cardiovascular and autonomic effects. AddictBehav. 2011;36:737–42. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.01.008.

8 A. VENEGAS AND L. A. RAY