COMMERCE IN THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ATLANTIC DAVID...

Transcript of COMMERCE IN THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ATLANTIC DAVID...

David Hancock COMMERCE IN THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ATLANTICDAVID HANCOCK

Commerce and Conversation in theEighteenth-Century Atlantic: The Invention ofMadeira Wine In 1807, Madeira was the foremost luxurydrink of the day—not a common beverage wine, but an expen-sive, exotic, status-laden, and highly processed wine produced onthe Portuguese island of Madeira, 500 miles west of Morocco. Byway of contrast, in 1703, it was a cheap, simple table wine, madefrom a base of white grape must to which growers and exportersadded varying amounts of red must in order to give it color andtaste. Between 1703—the year when the Methuen Treaty be-tween England and Portugal was signed—and 1807—the yearwhen Britain occupied the island—the wine that oenophiles andsongsters extolled in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries wasinvented.

The story of this transformation offers a compelling insightinto eighteenth-century Atlantic commercial life in all its com-plexity. The invention of Madeira wine was both an economicact—carried out in response to commercial motives—and a socialact—not invented by a solitary “genius” but by an Atlantic net-work of producers, distributors, and consumers in intense con-versation with one another. Trans-Atlantic commerce was adiscursive system, a process that sprang from a continual, compli-cated, often confusing exchange of information about commodi-ties—how they were made, packaged, and shipped; how theywere distributed; and how they were stored, displayed, andconsumed. The story provides a remarkable case study of theexpansion of the Atlantic market economy in the eighteenthcentury—through product innovation, the elaboration of distri-bution channels and networks, and heightened consumption.1

David Hancock is Associate Professor of History, University of Michigan. He is the authorof Citizens of the World: London Merchants and the Integration of the British Atlantic Community,1735–1785 (Cambridge, 1995).

The author would like to thank Eliza McClennen for creating the map of the Atlanticocean currents, trade winds, and shipping routes.

© 1998 by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the editors of The Journal ofInterdisciplinary History.

Journal of Interdisciplinary History, xxix:2 (Autumn, 1998), 197–219.

1 The role of conversation in modern business strategy has been examined by John J. Quinn,“The Role of ‘Good Conversation’ in Strategic Control,” Journal of Management Studies, XXX

structural and sociological perspectives on the atlantic

economy The idea of an Atlantic economy is relatively new.One of the more signiªcant developments in the historiographyof the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries during the past ªvedecades has been the emergence of a fuller comprehension of theAtlantic community as an entity in its own right. What was earlierdubbed Anglo- or British, French, Spanish, or Portuguese Amer-ica is now as often described as part of Atlantic America—acommunity that exchanged commodities, services, settlers, andlaborers; waged war on itself; and shared political ideas and insti-tutions, even while its constituent states also exhibited distinctivecultures. Scholars now see the Atlantic as “a waterway more thana moat,” and, with the application of new labels and metaphors,have found new perspectives on one of the world’s great storiesof economic development. We now look at the lands frontingthe ocean and see “the scene of a vast interaction,” the “steady,increasing contact, intermingling and sometimes direct blending”of peoples, plants, and animals, as well as goods, tools, services,and ideas.2

The initial trans-Atlantic perspective was deªned early in thiscentury by the founders of what came to be known as “theimperial school of early American history.” Chief among themwere Charles Andrews of Yale and Clarence Haring of Harvard,who wrote extensively from the 1910s through the 1940s—Andrews on England and Haring on Spain. They viewed therespective empires that they studied structurally, almost as idealforms that were viable only as abstractions. This structural per-spective found the sinew of empire in institutional, governmental,and bureaucratic activities. Accordingly, these authors interpretedthe social and economic life of Atlantic empires as a matter ofinstitutions, an extension of metropolitan governments and thecreation of cabinet ministers.3

(1996), 381–394; Jeffrey D. Ford and Laurie W. Ford, “The Role of Conversations inProducing Intentional Change in Organizations,” Academy of Management Review, XX (1995),541–570.2 Ian Steele, “Empire of Migrants and Consumers: Some Current Approaches to the Historyof Colonial Virginia,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, XCIX (1991), 491; DonaldW. Meinig, The Shaping of America: A Geographical Perspective on 500 Years of History (NewHaven, 1986), I, 65.3 Charles Andrews, The Colonial Period of American History (New Haven, 1934–1938), 4v.;Clarence Haring, The Spanish Empire in America (New York, 1947).

198 | DAVID HANCOCK

The structural perspective eclipsed the ªeld until the 1950s,when a new group of scholars began to reexamine early-modernAtlantic empires, states, and communities from a more “sociologi-cal” perspective. A wider range of historical phenomena de-manded explanation—ideologies, social forms, economies, andcolonial laws and politics—and a wider array of evidence wasmarshalled to understand them. Scholars adopting the sociologicalperspective conceived of empire more as a process than as astructure, and the connections that they found were typicallysocial and human. Such an approach allowed economic and socialhistorians to investigate the “micro” context of early-modernEuropean and African activity in the New World, as well as the“macro” context, the widening sphere of cause and effect as theempires interacted through expansion, trade, and war. In the studyof commerce and exchange, “sociological” historians, like Tollesand Bailyn, emphasized the social bases of economies—for in-stance, the religious ties of America’s Quaker merchants and thekinship networks of New England’s mercantile force. Their per-spective repeatedly identiªed individual choice within social andcultural contexts, rather than centrally directed, bureaucraticallyimplemented policy, as the lens for understanding this subject.4

The new Atlantic perspective extends these sociologicallyinformed histories to entire Atlantic communities. Its continuityis the examination of social, commercial, and cultural lives, espe-cially of the marginal members of society. It also opposes thenearly total preoccupation with domestic colonial American af-fairs, and considers the larger Atlantic basin just as important asthe smaller regional groupings or the still-smaller jurisdictions ofcolony, county, or town. Those who have focused on individuals’contributions during the eighteenth century, in particular, haveuncovered an intensiªcation of trans-Atlantic social linkages: a

4 The term, “sociological,” is not meant to limit the discussion to the subjects of modernacademic sociology. The term more broadly refers to the social, economic, or ideational—asopposed to the formal, institutional, or structural—aspects of life in the past. For examples,see Frederick B. Tolles, Meeting House and Counting House: The Quaker Merchants of ColonialPhiladelphia, 1682–1763 (Chapel Hill, 1948); Thomas Doerºinger, A Vigorous Spirit of Enterprise:Merchants and Economic Development in Revolutionary Philadelphia (Chapel Hill, 1986); WilliamT. Baxter, The House of Hancock (Cambridge, Mass., 1945); Bernard Bailyn, The New EnglandMerchants in the Seventeenth Century (Cambridge, 1955). For recent work along similar lines,see John Clark, La Rochelle and the Atlantic Economy during the Eighteenth Century (Baltimore,1981).

COMMERCE IN THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ATLANTIC | 199

surge in commercial correspondence, a growth in the number andintricacy of supplier/consumer relationships, a rise in the avail-ability and ºexibility of ªnancial services involving credit andinsurance, and an increase in the publication and dissemination ofmaritime and mercantile information. These researches have alsohighlighted the dynamic growth and globalization of commercialactivity during the eighteenth century, when more goods wentto more and more distant places around the world. At the end ofthe eighteenth century, the Atlantic was more integrated eco-nomically than it had ever been.5

production, consumption, and conversation Since theAtlantic integration process was both an economic and a socialevent, this article extends current scholarship about the expansivesocial construction of the Atlantic market economy by emphasiz-ing the interactive nature of much overseas trade. Madeira winewas invented in a century-long series of conversations, the record

5 Ralph Davis, The Rise of the Atlantic Economies (London, 1973); Jacob Price, Capital andCredit in British Overseas Trade: The View from the Chesapeake, 1700–1776 (Cambridge, Mass.,1980); Steele, The English Atlantic, 1675–1740: An Exploration of Communication and Community(New York, 1986); Hancock, Citizens of the World: London Merchants and the Integration of theBritish Atlantic Community, 1735–1785 (Cambridge, 1995). Kenneth Morgan, Bristol & theAtlantic Trade in the Eighteenth Century (Cambridge, 1993), 9–10, traces the stretching of oneport’s commercial lines. Similarly, American commodities were shipped to newer, moredistant markets, as the century progressed. Price, France and the Chesapeake: A History of theFrench Tobacco Monopoly, 1674–1791, and of its Relationship to the British and American TobaccoTrades (Ann Arbor, 1973), 2v.; idem, The Tobacco Adventure to Russia: Enterprise, Politics, andDiplomacy in the Quest for a Northern Market for English Colonial Tobacco, 1676–1722 (Philadelphia,1961); Paul Clemens, The Atlantic Economy and Colonial Maryland’s Eastern Shore: From Tobaccoto Grain (Ithaca, 1980); Peter Coclanis, The Shadow of a Dream: Economic Life and Death in theSouth Carolina Low Country, 1670–1920 (New York, 1989); Robert C. Nash, “South Carolinaand the Atlantic Economy in the Late Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries,” EconomicHistory Review, XLV (1992), 677–702. On cloth distribution worldwide, see John Irwin andKatharine Brett, The Origins of Chintz (London, 1970), 3–6.

Another mark of Atlantic economic integration was the rise of similar institutions andideologies in different countries. Various cities served similar functions around the Atlanticrim. See Anne Perotin-Dumon, “Cabotage, Contraband, and Corsairs: The Port Cities ofGuadeloupe and Their Inhabitants,” in Franklin W. Knight and Peggy K. Liss (eds.), AtlanticPort Cities (Knoxville, 1991), 61. Distinct similarities among labor markets emerged. SeeMarcus Rediker, Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea: Merchant Seamen, Pirates and theAnglo-Maritime World, 1700–1750 (New York, 1993), 80. Similar kinds of economic manage-ment—that is, plantation experts—appeared in all empires and created “a unique market-oriented set of cash crop-producing areas” (Pieter C. Emmer, “The Dutch and the Makingof the Second Atlantic System,” in Barbara L. Solow [ed.], Slavery and the Rise of the AtlanticSystem [New York, 1991], 79).

200 | DAVID HANCOCK

of which we ªnd in letters and visits between producers andcustomers. These conversations changed the product, its distribu-tion, and, eventually, its social status over the course of thecentury. This article is concerned with their effect on innovationin the drink itself.

Product innovation has been little explored and poorly un-derstood by most students of Atlantic America’s history. Previousstudies have focused on products statically, as either the end resultsof production processes or the carriers of meanings, rather thandynamically, not as evidence of the volatile social and materialinºuences on trade. Madeira wine, to cite only one example, wasinvented by a highly verbal, contentious, and, to the participants,occasionally irritating discourse.

This discourse informs a wider range of developmental eco-nomic, demographic, and social issues. In particular, the historyof the conversations among producers, distributors, agents, andconsumers and the resulting product innovation in Madeira wineshed light on two current vigorous debates among American andEuropean historians: one about the origins of the Industrial Revo-lution and another about the engine and nature of the earlyAmerican economy. Because they are not primarily interested inthe social nature of trade, the participants in these debates havetended to focus on different groups—one side looking at produc-ers and merchants, products and processes, and the other side atconsumers and taste-setters, commodities and meanings. Sadly, themore these debates become polarized, the more the participantstalk past each other.

Historians of the production “school” deal with manufactur-ers, farmers, and laborers, and the tools and machines that theyused, that is, the human and nonhuman agents that increased thesupply of goods. These historians stress that, in the aggregate—taking storage into account—people cannot consume more thanthey produce: The dramatically rising standards of living in theindustrialized world during the last two centuries could not havehappened without the changes in technology that made peoplemore productive and increased the amount of consumables. Theyaccount for America’s development by the availability of goods,as determined by production and transportation; they discussthe cultivation of food, economic cycles, the composition of theworkforce, and shipping routes, with seldom a word about the

COMMERCE IN THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ATLANTIC | 201

tastes and needs of the eventual consumers. In short, they ignorethe place of commodities in people’s lives. Their justiªcation fordoing so is the belief that the nature of production determines thetype of society, especially in vigorous periods of economicchange.6

Historians from the more recent consumption “school” grantprimacy to demand, and to the “work” of consumers in creatingand manipulating the meanings of the goods that they buy anduse. They point out that the two centuries from 1600 to 1800witnessed a sustained increase in the consumption of marketedgoods (as opposed to home-produced goods) well in advance of thelegendary productivity increases of the Industrial Revolution.Accordingly, they see the Industrial Revolution as the producers’creative response to consumers’ demand. Consumption-side his-torians who address issues central to the development of theAmerican economy look at people as consumers—buyers andusers of goods—often in the context of managing domestic house-holds. The choices made by these consumers were not determinedby impersonal forces or machines, but by consumers’ creativity incombining goods and attitudes to “produce” social roles andmeanings.7

6 Phyllis Deane and William Cole, British Economic Growth, 1688–1959: Trends and Structure(Cambridge, 1967; 2d ed.), highlighted the importance of British exports to the rise of certainindustries (like cotton manufacturing) and industrial production in the overall economy. Theymade no attempt, however, to incorporate consumer preferences into their calculations; theywere concerned solely with large-scale production of goods and services. More recently, JoelMokyr picked up this theme in discussing the importance of new technology to industriesacross the board (The Lever of Riches: Technological Creativity and Economic Progress [New York,1990]; “Technological Change, 1700–1830,” in Roderick Floud and D. N. McCloskey [eds.],The Economic History of Britain since 1700 [Cambridge, 1994; 2d ed.], I, 12–43). Two outstand-ing examples of the production school are Richard Dunn, Sugar and Slaves: The Rise of thePlanter Class in the English West Indies, 1624–1713 (Chapel Hill, 1972); Price, Capital and Credit.7 Colin Campbell, Lorna Weatherill, Carole Shammas, and Richard Bushman have alllooked at issues connected to spending: Campbell, The Romantic Ethic and the Spirit of ModernConsumerism (London, 1987); Weatherill, Consumer Behavior and Material Culture in Britain,1660–1760 (London, 1988); Shammas, The Pre-Industrial Consumer in England and America(Oxford, 1990); Bushman, The Reªnement of America: Persons, Houses, Cities (New York, 1992).Ann Martin has provided the best succinct summary of the scholarship. Her distinctionsbetween consumption, consumerism, and materialism deserve wider notice (“Makers, Buyers,and Users: Consumerism as a Material Culture Framework,” Winterthur Portfolio, XXVIII[1993], 141–157). Two collections of essays, one edited by John Brewer and Roy Porter thatcovers both sides of the Atlantic, and another edited by Cary Carson that covers America,have been highly inºuential: Brewer and Porter (eds.), Consumption and the World of Goods(London, 1993); Carson, Ronald Hoffman, and Peter Albert (eds.), Of Consuming Interests:The Style of Life in the Eighteenth Century (Charlottesville, 1994), especially Carson’s chapter,“The Consumer Revolution in Colonial British America: Why Demand?” 483–697.

202 | DAVID HANCOCK

As provocative and fruitful as these approaches are, both areplagued by the problem of one-way causality: Either producersor consumers determine the outcome. Yet, in complicated reality,production and consumption, technology, use, and meaning con-stantly affect each other, offering individuals ever-changing op-portunities to make and remake their lives, and to choose andstructure the icons of their societies. On the one hand, consumersconstrained production (and distribution); their preferences forcertain goods in their domestic lives and social “projects” werenot lost on producers and distributors. On the other hand, pro-duction and distribution constrained consumption: The organiza-tion of the market and the machinations of its entrepreneursinºuenced what products were available, to whom, and on whatterms. Moreover, producers and distributors actively manipulatedmeanings.8

To redress this problem of one-way causality, the concept of“reciprocal inºuence,” or “collaborative conversation,” seems be-spoke. Though it is trendy to invoke “conversation” today in allsorts of contexts, its use is apposite in this one. “Conversation,”in the eighteenth-century sense of the term, meant dealing withothers or things. It need not have been a public or private oralexchange, discussion, debate, or conference. Conversation onlyhad to exhibit two characteristics: (1) collaboration, that is, anexchange of information between at least two persons, and (2)reciprocity, that is, an opportunity for all participants to revealtheir knowledge and articulate their positions. As Fielding deªnedit, conversation was “that reciprocal Interchange of Ideas, bywhich Truth is examined, Things are, in a manner, turned around,and sifted, and all our knowledge communicated to each other.”In the Atlantic commercial world, “conversation” was no meremetaphor.9

8 Jan De Vries avoids the causality problem by suggesting that rising production andconsumption in the years from 1492 to 1776 were both the results of the spread of theEuropean market economy (“Between Purchasing Power and the World of Goods: Under-standing the Household Economy in Early Modern Europe,” in Brewer and Porter [eds.],Consumption, 85–132).9 Richard Bradley, A Philosophical Account of the Works of Nature (London, 1721), 59;Alexander Hamilton, A New Account of the East Indies (London, 1727), I, xxv, 320; SamuelJohnson to Edward Cave, c. April 1738, in Bruce Redford (ed.), The Letters of Samuel Johnson(Princeton, 1992), I, 14; John and William Langhorne (trans.), Plutarch’s Lives (London, 1770;new ed., London, 1786), I, 152; John C. Stephens (ed.), The Guardian (Louisville, 1982), 111;

COMMERCE IN THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ATLANTIC | 203

Through conversation, producers and distributors providedand obtained information about consumer needs and productproblems; they created understandings among parties; and theybuilt organizations. They made consumers partners in productinnovation, enlisting their aid in design, assessment, and dispersal.Consumers expected to be heard and heeded.

Producers and exporters also spoke to wholesalers, retailers,and customers—for instance, about how to “read” quality signalsin Madeira wine (and thus how to reproduce them) and abouthow best to market the wine. The producers and distributors withthe best transoceanic conversations—or at least the most extensiveconversational networks—fostered commitment and loyalty. Ex-tensive (and intensive) communication in the world of Atlanticcommerce transformed a collection of individual exporters,wholesalers, retailers, and peddlers into an information channelfor distributors to learn what was important to customers, and forbuyers to be educated about the treatment and use of a product.It was the chief mechanism for creating an adaptive response to,and an appreciation for, the product on the part of consumers.

the making of a wine And change the product did. What isknown today as Madeira wine was invented between 1703 and1807. Consider ªrst its variety. In 1703, only four grapes—white,black, Malvasia, and Vidonia—were grown on the island, and thewines made from them were mixtures of black and white grapes.By 1807, twenty-three varieties had been raised, including the

George B. Hill (ed.), Boswell’s Life of Johnson (Oxford, 1934), IV, 186; Henry Fielding,Miscellanies (London, 1743; 2d ed.), I, 119, 123.

Peter Burke, The Art of Conversation (Cambridge, 1993), 91, provides the best modernexplication of eighteenth-century “conversation,” although he narrows his focus to speechacts, ruled by “the spontaneity and informality of the exchanges” and “their ‘non-business-likeness.’” Several recent studies explore the characteristics of conversation behavior in modernsociety and, although their work is not historically grounded, some of their insights arerelevant: Susan K. Donaldson, “One Kind of Speech Act: How Do We Know When We’reConversing?” Semiotica, XXVIII (1979), 259–299; Stephen Levinson, Pragmatics (Cambridge,1983); H. Paul Grice, “Logic and Conversation,” in Peter Cole and Jerry Morgan (eds.),Syntax and Semantics 3: Speech Acts (New York, 1975), 41–58; John Wilson, On the Boundariesof Conversation (Oxford, 1989). These scholars generally regard speech acts as oral forms distinctfrom literate discourse. One scholar who has paid attention to the similarities, as this articledoes, is Robin Lakoff, Talking Power: The Politics of Language in Our Lives (New York, 1990),40–53.

204 | DAVID HANCOCK

four “noble” varieties that were made from the unblended stockfavored by consumers for their smoothness and ºavor—the drySercial, the less dry Verdelho, the medium sweet Boal, and the sweetMalvasia Candida (Malmsey).10

When unblended lots began to appear in Atlantic marketsafter mid-century, American and British consumers reported tothe distributors that they preferred them to blended lots. Americandrinkers desired the dryer wines; British drinkers wanted thesweeter kinds. This divide spurred growers and distributors toproduce new varieties with the requisite smoothness and sweet-ness. But, because agricultural constraints sometimes kept themfrom being able to satisfy demand, they had to ªnd ways toconvince importers and consumers of the qualities of other, time-honored varieties that they had at their command.11

In addition to increasing varieties and introducing pure un-blended drinks, the producers began to fortify Madeira withbrandy. Fortiªcation is often singled out as one of the hallmarksof Madeira’s wine, but it was introduced into production anddistribution only in the second quarter of the century, takingdecades to become widespread. Although an English physicianªrst prescribed the practice in the early seventeenth century,descriptive mention of adding brandy to Madeira occurred in a1743 edition of Poor Richard’s Almanac, in which Benjamin Frank-lin urged readers who were either shipping or selling Madeira tomix it with brandy. The ªrst reference to island producers ordistributors adding brandy as a supplement appeared ten yearslater, suggesting that the practice was gaining acceptance on theisland by mid-century.12

10 Hans Sloane, A Voyage to Jamaica (London, 1687), 10; John Ovington, A Voyage to Suratin the Year 1689 (London, 1696), 13; Graham Blandy (ed.), The Bolton Letters (Funchal, 1960),II, passim; “Inventories” Books, v. 1794–1797 & v. 1798–1800, Cossart & Gordon Papers,Madeira Wine Company Archives, Funchal; Nicholas C. Pitta, Account of the Island of Madeira(London, 1812), 66; William Gourlay, Observations on the Natural History, Climate and Diseasesof Madeira (London, 1811), 15.11 Thomas Murdoch to Francis Newton, May 4, 1792, v. 14, f. 180, Newton, Gordon &Murdoch to Harriet Horry, February 17, 1802, v. 23, f. 102, Newton & Gordon Letterbooks.12 On alternative wines generally, see Alan D. Francis, The Wine Trade (London, 1972);Warner Allen, Sherry and Port (London, 1952); George Robertson, Port (London, 1978; 4thed.), 12, 15, 16; Julian Jeffs, Sherry (London, 1992; 4th ed.). Although Madeira was the ªrstIberian wine to be fortiªed, in the 1600s, Dutch merchants were already rectifying their ownbrandy and adding it to common beverage wines to produce brandewijn (named for the“burning” process of distillation), a drink more suitable for long-distance travel. On Madeiran

COMMERCE IN THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ATLANTIC | 205

Adding spirits to the wine was thought to “help” “veryindifferent and clear” grades. It imparted a smooth taste to rough,acidic, or full-bodied wines. As one ªrm explained to Londonpurchasers, since Madeira’s wine was “sweetish” in the must, itneeded more brandy “than was common” to other wines to “eatoff the sweetness” and thereby “prevent fretting.” Today, weknow that the practice ensures microbiological stability, renderingimpotent most bacteria and strains of yeast and thereby precludingfurther fermentation. It also pleased consumers in certain markets,like London, where “they like everything that is powerful andheady.” However contemporaries described or justiªed it, by1760, fortiªcation appears to have been adopted by enough exportªrms to warrant the island government’s banning the importationof expensive French brandy, on the grounds that too much of itwas being watered down; diluted brandies sullied the reputationof the island’s export wines. Some export ªrms, especially thosespecializing in higher-quality wines, initially refused to addbrandy. As late as 1807, they were still decrying such “spoilage”and arguing for its use only as a last resort. But despite theremonstrations of a few, the “brandy doctrine” had gained generalacceptance by 1790. Brandy became the “indispensable” compo-nent of all grades.13

fortiªcation, see William Vaughan, Directions for health, natural and artiªciall (London, 1633;7th ed.), a reworking of his Natural and artiªciall directions for health (London, 1600); RichardSaunders, Poor Richard, 1743 (Philadelphia, 1743), in Leonard W. Labaree (ed.), The Papers ofBenjamin Franklin (New Haven, 1960), II, 367; Francis Newton to Thomas Newton, August4, 1753, Francis Newton to George Spence, October 27, 1753, Newton & Gordon Letter-books, v. 1, ff. 62, 77.13 Newton & Gordon to Kearny & Gilbert, January 25, 1768, v. 4, f. 171, Thomas Murdochto Thomas Gordon, January 28, 1789, Newton & Gordon Letterbooks; John Leacock toMichael Nowlan, June 2, 1779, Leacock Papers; Johann Wilhelm Von Archenholz, A Pictureof England (Dublin, 1791), 203; James Gordon to Alexander Gordon, March 14, 1768, Gordonof Letterfourie Papers; Provedoria da Fazenda, no. 942, ff. 19–20, Arquivo Regional Madeira,Funchal; Newton & Gordon to Kearny & Gilbert, January 25, 1768, v. 4, f. 171, ThomasMurdoch to Thomas Gordon, January 28, 1789, v. 11, f. 218, Thomas Murdoch to ThomasGordon, January 28, 1789, v. 11, f. 218, and June 15, 1789, v. 12, f. 86, Newton & Gordonto Thomas Gordon, August 19, 1789, James Gordon to Thomas Gordon, September 3, 1803,and Thomas Murdoch to Robert Lenox, September 30, 1803, v. 25, f. 173, Newton &Gordon Letterbooks; James Gordon to Alexander Gordon, May 22, 1769, Letterfourie Papers;Newton & Gordon to Thomas Gordon, January 28, 1789, v. 11, f. 177, Newton & GordonLetterbooks; John Leacock, Sr. to William Leacock, May 29, June 27, 1799, Leacock & SonsLetterbook 1799–1802, 35, 52–58, Michael Nowlan to Gedley Clare Burges, February 25,1762, Nowlan & Burges Letterbook, Leacock Papers.

206 | DAVID HANCOCK

The widespread fortiªcation of Madeira wine with brandy,which preceded that in Port and Sherry production, was largelycustomer-responsive. Firms altered wine formulas to suit the vari-ous palates in British America, negotiating with American dis-tributors in each region in response to the preferences ofpurchasers. The correspondence between island ªrms and theircustomers shows how producers and distributors varied the for-mulas. Foremost in the minds of customers were questions ofcolor and taste. With no adulteration, new wine bore a reddishcolor and sweetish taste; old wine, having experienced additionalfermentation and climatic heating, had a lighter hue and a drierºavor. The addition of brandy accelerated both processes.

In the British West Indies and the southern colonies of BritishNorth America, where there was no concern for wine spoilingfor lack of heat, dark, sweet wines ºourished. To satisfy customersthere, Madeira distributors put less brandy in their export. Some-times, in response to requests from Caribbean planters, they senta quarter cask of red must and another of brandy along with apipe of unfortiªed wine so that it could be colored and strength-ened to taste. In contrast, consumers to the north asked for a paler,drier wine, and so producers and shippers added one or twogallons more of brandy than they put in Caribbean wine. SouthCarolinians and Virginians preferred extremely pale, dry whitewine (“white as water”) that had been heavily fortiªed; Philadel-phians requested golden wines with slightly less brandy andslightly more sweetness; and New Yorkers wanted an amber,somewhat reddish drink with even less brandy and more sugar.Each market demanded and—after several rounds of serious ne-gotiation about body, smoothness, and ºavor—each market re-ceived its own distinctive formula.14

Fortifying the wine created technical problems for wine mak-ers. Unless treated further, fortiªed wines could be quite rough;the brandy spirit, with its lower density, tended to ºoat on top

14 Thomas Murdoch to Pierce Butler, October 18, 1800, Newton & Gordon Letterbooks;Spence, Leacock & Spence to John Erskine, June 26, 1762, John Leacock to William Leacock,May 10, 1796, Leacock Papers; Henry Laurens to Corsley Rogers & Son, May 16, 1755, inPhilip M. Hamer (ed.), Papers of Henry Laurens (Columbia, S.C., 1968), I, 248; Newton &Gordon to John Diffell, January 17, 1776, v. 6, f. 38, Newton & Gordon Letterbooks; ThomasNewton to Newton & Gordon, November 26, 1759, Thomas Newton Letterbook, MadeiraWine Company Archives; Baynton & Wharton to Thomas Newton, October 2, 1763, Box2, Cossart & Gordon Papers, Liverpool University Archives.

COMMERCE IN THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ATLANTIC | 207

of the wine. To solve this problem, the Madeirans introducedanother vinicultural innovation—agitation. Shaking or rockingthe wines had the effect of distributing the alcohol more evenlyafter the introduction of brandy; it also removed suspended andinsoluble materials from the must and eradicated “the hot andburnt taste and twang” left behind after ªning with gesso.15

Agitation happened inadvertently at ªrst. Pipes in the holdof a vessel rocked to and fro as the ship rode out high waves orintense storms. Eventually, exporters and customers made theconnection between the agitation and its effect. As John Leacock,a shipper, had learned from a two-year-long correspondence withone of his customers, a New York wine retailer, “in the courseof eight or nine months’ continual agitation on board a vessel, theextra ªre and spirit of the brandy must be exhausted and softened,and the wine receive the strength.” He also had learned that notall voyages were alike: Since some ships experienced greateragitation than others, the quality of the wines varied greatly.Acting on knowledge gleaned from agents’ reports and consumers’requests, island distributors resorted to direct agitation in the1780s. Leacock, for instance, insisted that his growers install me-chanical devices to stir the wine twice a day during fermentation.After initial fortiªcation and fermentation, island ªrms assignedofªce servants to simulate the effect of stormy seas by manuallyrocking the wine in the casks. Later, toward 1800, as Americansbegan to report a preference for artiªcially rocked, rather thannaturally but erratically rocked, wines, distributors employed newsteam-powered machines to perform the task.16

A similar kind of intervention process occurred in aging thewine. Well before the eighteenth century, it was recognized thataging improved wine, making it “ªt for drinking much sooner.”It diminished the harsh taste and yeasty odor. To Madeira, itimparted a smooth, mellow, nutty ºavor and a clear, pleasing,often invigorating odor. Aging also allowed wine to fare “better”(that is, not sour as quickly) in “colder climates” like Boston,

15 Aaron Hill to William Popple, November 30, 1740, in Aaron Hill, The Works (London,1754; 2d ed.), II, 103.16 John Leacock to William Leacock, April 3, 1789, Leacock & Sons Letterbook, ff. 71–75,Leacock Papers; Richard Derby to Scott, Pringle & Cheap, June 1, 1767, Richard DerbyLetterbook 1760–1772; John Searle & Co. to Elias Hasket Derby, March 23, 1788, DerbyFamily Papers, Box 12, Folder 6, Essex Institute; Pitta, Account, 71.

208 | DAVID HANCOCK

Québec, and London. However, at ªrst, when aging occurred, ittook place in the cellars of consumers. In 1700, when Madeiradistributors described the wine that they shipped to America orBritain as “old,” they meant wines of eighteen months or so—theproduct of the previous year’s vintage that they had been unableto sell. Wine older than that usually had been hoarded by pur-chasers: When Dean Swift, for example, cracked open a bottle,he was pouring a wine purchased at least seven years before; whenCharleston merchants advertised aged Madeira in 1761, they werereferring to wines imported ªfteen years before and kept in theirwarehouses; and when Thomas Jefferson presented thirty-six bot-tles to an old science professor in 1775, he was giving Madeirahis family had placed in its cellars eight years earlier.17

Not until the American Revolutionary period did distributorsintentionally begin to keep wines for longer than a year or two.The commercialization of aged wines can be dated with someprecision. Madeira’s merchants did not begin to charge £1 sterlingmore per pipe for every additional year of age until 1781. Thisnew price followed the conjunction of two events: The ªrst wasa run of low harvests between 1768 and 1772, when vintages fellto one-third of their usual output, and distributors almost ran outof wine to satisfy long-standing buyers. To guard against a recur-rence of the problem, distributors began restocking their wines inearnest during the mid- and late-1770s, when harvests returnedto average levels. At the same time that they were replenishingtheir wine stocks, however, the Revolutionary War cut off theiraccess to American customers. The number of ships bound toBritish North America dropped by three-fourths—nine ships peryear—and the amount of wine shipped by two-thirds.18

17 Nowlan & Burges to Samuel Hall, April 10, 1760, Nowlan & Burges Letterbook1759–1762, Leacock Papers; Jonathan Swift to John Gay, March 19, 1729/30, in HaroldWilliams (ed.), The Correspondence of Jonathan Swift (Oxford, 1963), III, 381; Herman Moll,Atlas Geographus: Or, A Compleat System of Geography . . . for Africa (London, 1714), IV, 692;South-Carolina Gazette, 1761, 4; Thomas Jefferson to William Small, May 7, 1775, Julian Boyd(ed.), The Papers of Thomas Jefferson (Princeton, 1950), I, 165.18 Francis Newton to George Spence, June 9, 1756, Newton & Gordon Letterbooks, v. 1,f. 208; Francis Newton to Mackenzie & Edington, September 3, 1756, v. 1, f. 222, Newton& Gordon Letterbooks. At ªrst, the premium for older wines was £1 sterling for every year,but after March 1785, merchants were allowed to charge whatever “they [thought] the oldwine [was] worth.” John Leacock to Michael Nowlan, March 26, 1785, Leacock, Spence &Leacock Letterbook 1784–1789, f. 116, Leacock Papers.

COMMERCE IN THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ATLANTIC | 209

To deal with the surfeit, the distributors bought or rentedmore storehouse space in Funchal. They also continued restock-ing, purchasing pipes and staves, hiring coopers, and buying morewine at the press. While the wine sat and aged in Madeira, thestores and cellars of revolutionary America were being exhaustedand plundered. When the sizable American market for Madeirawine thirstily returned at war’s end, the distributors took advantageof the situation: Not only did they off-load their aging supply,but they also segmented the market and stratiªed their customersby wealth and taste, introducing a vocabulary of age distinctionsthat postwar consumers in Kingston, Philadelphia, New York, andLondon used to describe what they were drinking with moreprecision, and to distinguish themselves from those who dranknew wine. “Age, Age” became “the grand sine qua non.”19

The Madeira shippers introduced aged wines and age distinc-tions with some apprehension, but the risk was worth taking.Consumers’ reports on old wines were largely favorable. Accord-ingly, shippers came to realize that “a reserve must be kept ade-quate.” As William Johnston wrote to his partner, “the taste forold wines” had “become so general” in America by 1787 that“none but old wines would please.” By 1793, some ªrms wereselling eight- and ten-year-old wines; by 1807, they were offeringªfteen-year-old wines.20

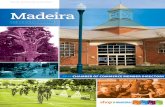

Intentional aging of Madeira wine coincided with one ªnalproduct innovation—heating—which also developed in concertwith customers’ views. Some heating occurred naturally on theisland. The early blended wines were naturally heated from directexposure to the sun during the harvest, as well as while stored inwooden attics before shipment. Additional heating occurred inthe holds of ships. As Figure 1 shows, Madeira was the favoredoutbound stop for British and American ships en route to Africa,India, the Caribbean, and North America. Because of the conªgu-ration of trade winds and ocean currents, wine destined for NorthAmerica, Britain, and Northern Europe was forced to follow the

19 James Gordon to Alexander Gordon, September 21, 1769, Gordon of Letterfourie Papers;William Johnston to Thomas Gordon, November 10, 1788, v. 11, f. 177, Newton & Gordonto Thomas Gordon, November 24, 1791, v. 14, f. 15, Newton & Gordon Letterbooks;Francis Newton to Newton, Gordon & Murdoch, November 30, 1793, Loose Letters, Cossart& Gordon Papers, Madeira Wine Company Archives.20 William Johnston to Thomas Gordon, March 25, 1787, v. 10, f. 380, and ThomasMurdoch to Thomas Gordon, August 5, 1793, v. 15, f. 207, Newton & Gordon Letterbooks.

210 | DAVID HANCOCK

Fig. 1Atlantic Shipping Routes, Ocean Currents, and Trade Winds (Eliza McClennen, Cartographer)

long, indirect southern route. On these trips, it was subject toextremely high temperatures, often 110° and 120° F, en routefrom the tropics to New York or London. Sometimes it was evenremoved from the ship and lodged with a resident in port for anynumber of years.21

Since buyers began reporting that they liked wines that hadmade the voyage, distributors began sending wine on a longcircuit, even when quicker more direct routes were available. Theªrst mention of a distributor or consumer intentionally sendingwine the long way round via the West Indies occurred in 1749,and the India subcontinent in 1772. Thereafter, shippers experi-mented aggressively and competitively with heating routes.Through numerous trials, they established a circuit of “ºoatingovens” by 1775.22

During the decade of the American Revolution, when thewine was being stockpiled, producers shifted the process to land.References to ovens, stoves, and hothouses being used for warm-ing pipes and cellars on the island began to appear after the 1775publication of Sir Edward Barry’s Observations Historical, Critical,and Medical, on the Wines of the Ancients, which lavished attentionon the subject of wine heating. When Pantaleao Fernandes, aninety-year-old Portuguese merchant, constructed an estufa (oven,stove, or hothouse) in 1794 and placed casks of wine in it, anindustry was born.

Although Fernandes’ estufa was little more than a room ªlledwith barrels placed on trestles and warmed to 90° or 100° F bywood ªres—by all accounts, the work of a hobbyist—his estufagem

21 Knowledge about the inºuence of the ocean currents and the trade winds was not fullyacquired until after 1850, even though the currents and winds, and the place of Madeira inthem, had been studied for centuries. David W. Waters, The Art of Navigation in England inElizabethan and Early Stuart Times (London, 1958), 20–21, 147–148, 201–206, 261–268,284–287, 311–312. The winds were examined by Edmond Hally, who delivered what becamethe locus classicus on the subject to the Royal Society of London in 1686: “An historicalaccount of the trade winds, and monsoons, observable in the seas between and near theTropicks, with an attempt to assign the phisical cause of the said winds,” PhilosophicalTransactions of the Royal Society (London, 1686–1687), XVI, 153–168. For later accounts, seeFranklin’s explication of the Gulf Stream, in Albert Smyth (ed.), The Writings of BenjaminFranklin (New York, 1906), IX, 372–413; Thomas Pownall, Hydraulic and Nautical Observationson the Currents in the Atlantic Ocean (London, 1787).22 Sloane, Voyage to Jamaica, 10; Warren Johnson Journal, sub January 12, 1761, in MiltonW. Hamilton (ed.), The Papers of Sir William Johnson (Albany, 1962), XIII, 198; Francis Whiteto Richard Derby, May 7, 1766, Richard Derby Papers, Box 10, Folder 5, Essex Institute.

212 | DAVID HANCOCK

process initiated a frenzy of experimentation. Nearly every majorhouse rushed to rent a stove or build its own. By early 1799, forinstance, the large quality house of Newton & Gordon hadªnished building one estufa and was beginning work on another.Another ªrm built large tanks installed with hot-water coils tohold and heat new wine. The smaller, more typical house ofLeacock & Sons, which had ªnished plans for its stove, awaitedits completion by experimenting with the niceties of yet anothertechnique—immersing pipes of wine in heaps of dung. The ªrmreported to American customers that the smell was ªne and thelook good, but the taste somewhat harsh!23

By 1807, warming rooms had won out over dung heaps, and“all the Houses” were using estufas. Considerable savings in timeand money accrued from shortening production and avoidinglong-distance cargo fees: A wine that would have been palatableto Americans only after four or ªve years in England, three yearsin Madeira, or one year on the India subcontinent or in the WestIndies could be readied in an estufa in three months. Moreover,

23 Livro do Saida, no. 22, f. 24, Arquivo Nacional, Lisbon. Experiments are recounted inThomas Gordon to Francis Newton, October 24, November 17, 1783, v. 8, f. 124, April 14,1785, v. 8, f. 139, Thomas Murdoch to Thomas Gordon, November 20, 1789, v. 12, f. 177,and Thomas Murdoch to Francis Newton, September 1, 1792, v. 14, f. 322, Newton &Gordon Letterbooks. On earlier uses of stoves, see Barry, Observations (London, 1775), 1–10,48–58, 67–84, 442–443; Daniel Henry Smith to James & Alexander Gordon, December 1775,Gordon of Letterfourie Papers. As early as 1727, wine growers and makers along the Moselleappear to have been building iron stoves in their cellars and using them to meliorate wines.But the practice was not widely known, and no Madeiran mentioned German procedures.Barry’s inºuence is a far more likely one on the Anglo-centered Portuguese. On Fernandesand the ªrst estufas, see History of Estufa Heating, February 8, 1803, Arquivo MarinoUltramarino, no. 1,431, Arquivo Historico Ultramarino; Newton & Gordon to HenryHeskith, October 15, 1799, and to Edmund Middleton, April 20, 1801, v. 20, f. 67, v. 22,f. 367, Newton & Gordon Letterbooks. The love of experiment should not be overlooked;it played an important part. Visitors to the island, especially those among the foreign merchantcommunity, remarked on it. On later estufas, see Thomas Murdoch to John Campbell, April14, 1798, v. 18, f. 316, Thomas Murdoch to Thomas Gordon, June 27, October 15, 25, 1799,v. 19, f. 337, v. 20, ff. 52, 81, Thomas Murdoch to Robert Lenox, February 2, 1802, v. 23,f. 81, Newton & Gordon Letterbooks; John Leacock, Sr. to William Leacock, January 18,April 29, June 27, 1799, January 18, August 28, October 28, 1800, January 23, 1801, Leacock& Sons Letterbook 1799–1802, ff. 6–9, 27, 52–58, 107, 192–194, 223, Leacock Papers;Arquivo Marino Ultramarino, no. 1,431; Anonymous, A Guide to Madeira (London, 1801);Pitta, Account (1812). Throughout the period, however, ªrms remained reticent about placingtheir best wines in an estufa. See Newton, Gordon & Murdoch to Robert Lenox, v. 25,f. 173, September 30, 1803, Newton & Gordon Letterbooks. On early trials with dungheating, see Daniel Henry Smith to James & Alexander Gordon, December 1775, Gordonof Letterfourie Papers.

COMMERCE IN THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ATLANTIC | 213

in mellowing the wine, the distributors mitigated undesirablecharacteristics, thereby increasing the quality of their low-gradeexport wines. Ultimately, what guaranteed the success of thetechnology, however, was the response from the men and womenwho drank the wine in America, India, and Britain. The custom-ers’ “candid opinion” was unanimous and positive. Oven-heatedwines did not sour so quickly as unheated or traditionally heatedwines, and, just as important, they retained the essential deªningcharacteristics of color and taste. Thus, Madeira became a reliable“manufactured” luxury wine that men and women in the empirecould drink in the salons and stalls of fashionable London as wellas obtain from the general stores or ºatboat warehouses in theOhio River Valley.24

the sincerest form of flattery These innovations contrib-uted to the success of the wine in the British colonies not onlybecause they enhanced the reliability of the product but alsobecause they instilled in it an air of luxury and European (yetnon-British) status. Not coincidentally, Madeira was used to bribethe Indian chief Pontiac in 1766, to toast the work of the FirstContinental Congress in 1775, and to christen the launching ofthe Constitution in 1797.25

One way that producers and distributors created luxury statusfor the wine was by differentiating grades and types of Madeira.They sang the praises of new varieties like Sercial and Boal, andrare strains like Malvasia—all of which, even in the best vintageyears, were harvested only in small lots—to their correspondentsand customers. Certain grades they described as “opulent,” ªt onlyfor those in the metropolis with discerning palates, or for thoseon the periphery who aspired to live like them, or at least were

24 John Leacock, Jr. to William Leacock, August 28, 1800, Leacock & Sons Letterbook,Leacock Papers; October 21, 1800, Newton & Gordon Letterbooks; John Leacock, Sr. toJohn Parker, March 21, 1798, and John Leacock to William Leacock, January 18, June 27,1799, and August 28, 1800, Leacock & Sons Letterbook 1799—1802, ff. 6–9, 52–58, 192–194,Leacock Papers.25 Normand Macleod to Sir William Johnson, August 4, 1766, in Hamilton (ed.), Papersof Sir William Johnson (1957), XII, 150; Lyman H. Butterªeld (ed.), Diary and Autobiographyof John Adams (Cambridge, Mass., 1961), 136, 149; The Independent Chronicle and the UniversalAdvertiser, 23 Oct. 1797, 1; Boston Gazette and Weekly Republican Journal, 23 Oct. 1797, 1;Massachusetts Mercury, 24 Oct. 1797, 1; Columbian Centinel, 25 Oct. 1797, 1.

214 | DAVID HANCOCK

familiar with their genteel ways. Likewise, after 1780, they mar-keted wines of certain ages as more suitable for “intelligent”drinkers: the older the wine, the more distinguished its drinker.They went so far as to deploy testimonials from men of goodfamily or high ofªce to seduce would-be wine bibbers into raisingthe quality of their purchases. Customized packaging—tailor-made sizes, painted barrels, initialled and labelled casks, and thelike—reinforced the notion of exclusivity.26

In the course of turning Madeira into a luxury, the producersand distributors raised its price. A compilation of the standardshipping prices for Madeira wine exported from the island, al-though fraught with difªculty, suggests that export prices rosedramatically during the century. In the ªrst decade, the averageprice of a pipe of London Particular—the grade generally deemedmost suitable for discerning palates—was £5.5 at the dock inFunchal. By the third decade, that pipe’s price had risen to £8,by the ªfth, to £22.5, and by 1807, to £43. Unadjusted forinºation, the price rose eight-fold. Taking inºation into account,it tripled. Other qualities followed similar trajectories. The cheap-est wine in the Kingston, Boston, or London market in 1700 hadbecome the most expensive by 1800. Only “opulent people” couldafford to drink it.27

26 Famous customers were often used to impress other prospective purchasers. John Mars-den Pintard, for instance, “puffed” about his supply to George Washington and John Hancock( Joseph Gillis to Henry Hill, August 2–September 20, 1783, v. 9, ff. 14–16, Hill Letterbooks,John Jay Smith Family Papers “A,” Historical Society of Pennsylvania). On the tailoring ofpackaging to suit buyers, see Newton & Gordon to John Munro, June 10, 1789, to ThomasGordon, June 15, 1789, v. 11, ff. 75, 86, and to James Sheafe, March 18, 1801, v. 20, f. 315,Newton & Gordon Letterbooks.27 Sources for the shipping prices charged by Madeiran exporters to middlemen distributorsand consumers, even in the best years, are thin. There is no single series for the period from1703 to 1807. The principal extant sources are the letters and accounts of the exportersthemselves, as well as records of American and British importers. However, except for aletterbook kept by William Bolton, an island merchant, during the period from 1695 to 1715,and stray bundles of letters and accounts of other houses, ªrm papers have not survived forthe years before 1739. Island shippers did not report prices systematically until 1753. Theprices given in newspapers to advertise the sale of wines imported into America or Britainare useful and necessary in reconstructing colonial distribution patterns and purchasingconstraints, but since they incorporate the importers’ or tavernkeepers’ markup, they do notreveal the exact prices of the wines from Madeira. By 1800, the shipping price of Madeirarose 3.02 times, as determined from the elements in John McCusker’s composite commodityprice index for Great Britain (How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index forUse as a Deºator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States [Worcester, 1992]). Thesterling price index rose by a factor of 2.6 from 1703 to 1807. McCusker’s price index for

COMMERCE IN THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ATLANTIC | 215

These dramatic price increases were partially the result of anattempted cartel. With the sanction of the island’s local govern-ment, the island’s merchant and landed aristocracy aggressivelytried to control prices at their end. Most notably, the Britishorganized themselves into a trade association called the “Factory,”which was based in Funchal. From at least mid-century onward—the time when the British gained their own consul (no longersubordinate to the consul in Lisbon)—Factory members agreedupon shipping prices for each grade of export wine. During somedecades, they held prices constant from year to year; during others,they adjusted them yearly. Prices were set at the beginning ofJanuary and seldom altered, if at all, until the next calendar year.Although, as the century progressed, the members constituted adeclining share of the island’s merchant population, most mer-chants honored their rates. If they refused, they either had toundergo ostracism, pay severe ªnes, or leave the island.28

The rise in the number of entrepreneurs selling imitationMadeiras is evidence that the Factory’s attempts to create a luxuryproduct succeeded. Counterfeiting took a number of forms. Forinstance, the mixture of inferior northside wines with superiorsouthside wines on the island was considered a problem from the

American commodities rose only by a factor of 1.2 during that period. Although it is difªcultto know for sure, given the absence of an adequate series of exchange-rate data for the years1783 through 1807, it is possible that Madeira became even more expensive in America thanin Britain. On the rise to opulence, see Francis Newton to Newton, Gordon & Murdoch,May 29, 1798, Loose Letters, Cossart & Gordon Papers, Madeira Wine Company Archives.28 John Leacock accurately described the situation when he wrote to William Waddell ofNew York that, in greatest measure, “the price depends upon the demand” (November 16,1764, Spence, Leacock & Spence Letterbook 1762–1765, f. 185). That demand, in turn, waslargely due to the number of people willing and able to drink the wine, as well as the amountof wine available for importation. The rise in demand in North America was undoubtedlythe driving force behind the price increases of the late 1700s; it overpowered the fact thatthe supply was increasing. Nevertheless, the organization of the distribution cannot beignored; nor can the nearly constant warfare of the period.

A British “factory” was established at Funchal at some point in the late seventeenth orearly eighteenth century. Daily affairs were managed by a vice-consul who was subordinateto the Lisbon consul. In 1755, the Crown began appointing a consul to Funchal. The consuland vice-consul were always drawn from the British merchant group on the island. Theyenforced matters relating to trade law and monitored the breach of treaty privileges. The ªrstrecorded vice-consul was William Bolton in 1702 (Blandy [ed.], Bolton Letters, II, 21, subNovember 1702; Brass-Studded Blue “Minutes” Chest, British Factory Records, Blandy’sOfªce, Funchal; Arquivo Marino Ultramarino, no. 1,421). On self-regulation, see WilliamJohnston to Thomas Gordon, September 14, 1785, v. 9, f. 84, Thomas Murdoch to ThomasGordon, June 5, 1794, v. 15, f. 467, Newton & Gordon Letterbooks.

216 | DAVID HANCOCK

outset of the eighteenth century. The aldermen of Funchal issuednumerous edicts forbidding the movement of wines from one sideof the island to the other, on the grounds that mixing the wine,or fobbing off north wine as south wine, would harm the generalreputation of the island’s main export.

As prices rose after mid-century, imitation occurred withgreater frequency and greater creativity. In the early 1760s, forexample, many of the smaller, undercapitalized ªrms that wereestablishing themselves on the island—largely to take advantageof rising prices—began to “correct” the colors of their northsidemust. One especially innovative entrepreneur added the juice ofblack cherries so that his thin must bore the look of full body.Another counterfeiter ground up almond bark and added it to hiswine.29

Fraud also happened off-island. One aggressive “mushroommerchant” (so called as he had quickly sprung from obscurity)named Manoel Oliveira, who regularly brooked custom and made“advantageous offers” to other merchants’ suppliers and customers,in the late 1790s opened “an establishment” on the Azorean islandof Fayal, where he successfully concocted a wine that bore therough look and taste of Madeira. At the end of the century,Québec’s market, for one, was so ºooded with his counterfeit,which was produced and packaged with certain authentic mater-ials, that no other exporters were able to make any headway there.Since he operated from outside the island, the island establishmentwas powerless to stop him. Yet, in the end, the authentic pro-ducers beneªtted, too; his “trash” only served to underscore inthe minds of discerning Québécois what constituted a true Ma-deira.30

On the American side of the ocean, from Kingston to Louis-bourg, wholesalers and retailers were also busily engaged in thebusiness of imitation. Wine merchants Hugh and Alexander Wal-lace of New York warned their customer Sir William Johnson in

29 Report of the Governor of Madeira, October 17, 1761, no. 246, and Report of theGovernor of Madeira and Public Notice, February 1, 1768, nos. 289–290, Arquivo MarinoUltramarino. Concerning the rise of alternative wines after the Revolution, see Newton &Gordon to Hugh Moore, May 9, 1784, v. 8, f. 232, Newton & Gordon Letterbooks.30 Thomas Murdoch to Thomas Gordon, October 2, 1800, v. 21, f. 40, April 30, 1802,Newton & Gordon Letterbooks. For previous feints, see Francis Newton to Newton &Gordon, March 26, 1794, and Newton & Gordon to Thomas Gordon, July 8, December 7,1797, Loose Papers, Cossart & Gordon Papers, Madeira Wine Company Archives.

COMMERCE IN THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ATLANTIC | 217

1772 that taverns in up-country New York punningly sold adul-terated Tenerife wine as “Made, here, a.” Further south, JohnGuerard—a Charleston merchant who traded in dry goods andwines in the 1750s and 1760s—found the wines of Madeira“excessively dear”; most people were “forced to use wines thatare imported from the Canaries at a much cheaper price.” To“remedy” the situation, he instructed his captain to load Canarywines at the Canaries and “colour them like Madeira” on boardthe ship, so as to “best please our planters & others.” To him, thearrangement was a proªtable resolution of a problem posed bythe high shipping prices out of Madeira. Guerard and entrepre-neurs like him knew ªrsthand that “a variety of mixtures pass forMadeira, some of which are compounded of wines that nevergrew on the island.” Yet, scoundrels that they were, they had theadvantage of selling more cheaply while burnishing the status oftrue wine.31

Because we so often focus on the monumental increases in humanproductivity that followed the Industrial Revolution, it is easy toforget how innovative the eighteenth century was. The inventionof Madeira wine helps to bring this preindustrial inventivenessback into the picture, displaying the social—that is, decentralized,discursive, and reciprocal—nature of the process, and the Atlanticscale on which it took place.

Each aspect of Madeira wine’s invention unfolded throughtime and discourse. Producers and distributors continually “lookedover their shoulders” to see what customers wanted, and consum-ers paid close attention to what producers and distributors (andtheir neighbors!) were telling them about the proper use of a statussymbol. Innovations in selecting, fortifying, agitating, aging, andheating were not mainly responses to the ªne points of newtechnologies, but to negotiations between producers, distributors,and consumers. The traders and enterprisers who developed theMadeira market started small, eventually forming a network thatlinked producers on their little island to consumers around the

31 John Guerard to William Jolliffe, November 14, 1753, January 31, 1754, John GuerardLetterbook 1752–1754, South Carolina Historical Society, Charleston. See also Hugh andAlexander Wallace to Johnson, November 20, 1772, in Alexander C. Flick (ed.), Papers of SirWilliam Johnson (1933), VIII, 662; “The Autobiography of Peter Stephen Du Ponceau,”Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, LXIII (1939), 434.

218 | DAVID HANCOCK

world. They had to persuade consumers that changing varietals,agitating, and heating were valuable improvements. The goals ofMadeira consumers were probably more cosmopolitan—to showtheir familiarity with a trans-Atlantic luxury discourse. By the endof the eighteenth century, they had convinced producers to “im-prove” the product by aging and fortifying it. Understandingeighteenth-century trade and economics as a reciprocal inter-change and a collaborative conversation provides an alternative toone-sided explanations of economic progress before the IndustrialRevolution, and of the growth of the American economy.

The story of Madeira also demonstrates the Atlantic scale ofthe eighteenth-century economy. By the turn of the nineteenthcentury, Madeira was the drink of choice on the farms of back-country Ohio and on the plantations of Jamaica and Curaçao; itwas as much at home in the army messes and hospitals of Indiaas in the clubs and taverns of London or the country housesof Scotland. The Atlantic community—made up of Europeansand the European diaspora—was linked by shared (and stolen)production techniques, kinship and friendship relations, commonconsumption patterns—and conversations. The conversationabout Madeira was not grand, philosophical, nor even scintillating;it was plain, practical, and importunate. But it created a commoncommercial, cultural, and ideational space that pervaded the en-tire Atlantic basin—Europe, South America, Africa, and NorthAmerica.

COMMERCE IN THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ATLANTIC | 219