CME Common Craniofacial Anomalies: The Facial Dysostoses · mation was caused by imperfect...

Transcript of CME Common Craniofacial Anomalies: The Facial Dysostoses · mation was caused by imperfect...

CME

Common Craniofacial Anomalies: The FacialDysostosesJeremy A. Hunt, M.D., and P. Craig Hobar, M.D.Dallas, Texas

Learning Objectives: After studying this article, the participant should be able to: 1. Understand the etiology andpathogenesis of facial dysostosis syndromes. 2. Recognize and classify common facial dysostoses. 3. Understand thedifferent management plans for the reconstruction of facial dysostoses.

The wide spectrum of craniofacial malformationsmakes classification difficult. A simple classification systemallows an overview of the current understanding of theetiology, assessment, and treatment of the most frequentlyencountered craniofacial anomalies. Facial dysostoses arereviewed on the basis of their diverse etiology, pathogen-esis, anatomy, and treatment. Conditions discussed in-clude craniofacial microsomia, Goldenhar syndrome,Treacher Collins syndrome, Nager syndrome, Binder syn-drome, and Pierre Robin sequence. Approaches to thesurgical management of these conditions arereviewed. (Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 110: 1714, 2002.)

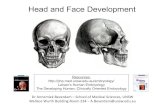

The wide spectrum of craniofacial malforma-tions makes them difficult to classify. Gorlin1,2

believes that our limited understanding of theembryology and etiology of the malformationsrestricts efforts at classification. In 1981 theCommittee on Nomenclature and Classifica-tion of Craniofacial Anomalies of the Ameri-can Cleft Palate Association3 grouped craniofa-cial disorders according to their diverseetiology, anatomy, and treatment. They pro-posed a practical and simple classification sys-tem of five categories that allows an overview ofour current understanding of the etiology, as-sessment, and treatment of the most frequentlyencountered craniofacial anomalies:

I. Facial clefts/encephaloceles and dysostosisII. Atrophy/hypoplasiaIII. Neoplasia/hyperplasiaIV. CraniosynostosisV. Unclassified

The broad category of facial clefts/encepha-loceles and facial dysostosis is extensive. In thisarticle, deformities of craniofacial dysostosiswill be reviewed and discussed, as will the sur-gical correction of these craniofacialanomalies.

In 1976 Tessier4 described an anatomicalclassification system whereby a number is as-signed to each of the malformations accordingto its position relative to the sagittal midline.This system has become internationally ac-cepted and allows concise and effective com-munication between clinicians.

Van der Meulen and coworkers5 tried to cor-relate clinical features of the disorders withembryologic events. The authors envisionedthe craniofacial skeleton as developing along ahelical course symbolized by the letter S. Theirscheme uses “focal fetal dysplasia” in prefer-ence to “cleft” for an arrest in skin, muscle, orbone development and names the dysplasticanomaly after the area(s) involved. In malfor-mations characterized by dysostoses, an addi-tional distinction is made between transforma-tion defects and developmental arrestsoccurring before fusion of the facialprocesses.5

The deformity known as maxillozygomaticdysplasia is equivalent to Tessier No. 6 cleft, orincomplete Treacher Collins syndrome. Thecomplete form of Treacher Collins is charac-terized by zygotemporoauromandibular dys-

From the Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. Received for publicationFebruary 14, 2002; revised May 29, 2002.

DOI: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000033869.10382.91

1714

plasia and corresponds to Tessier Nos. 6, 7, and8 clefts. Temporoauromandibular dysplasia isalso known as auromandibular dysostosis,hemifacial microsomia, or first and secondbranchial arch syndrome.

Maxillomandibular dysplasia is a failure ofthe maxillary and mandibular processes tofuse, resulting in macrostomia. Mandibulardysplasias, exemplified by the Pierre Robin se-quence, consist of micrognathia, glossoptosis,and respiratory distress.

CRANIOFACIAL MICROSOMIA

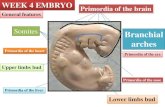

Craniofacial or hemifacial microsomia is theterm most frequently used to describe the firstand second branchial arch syndrome, whichcorrelates with a Tessier No. 7 cleft. Thomson6

was the first to suggest in 1843 that the malfor-mation was caused by imperfect developmentof the first two anterior branchial arches. Clin-ical manifestations of craniofacial microsomiaare underdevelopment of the external andmiddle ear and underdevelopment of the man-dible, zygoma, maxilla, temporal bone, facialmuscles, muscles of mastication, palatal mus-cles, tongue, and parotid gland. Macrostomia,a first branchial cleft sinus,6,7 and possible in-volvement of any or all cranial nerves8 are alsofeatures.

The birth incidence of craniofacial microso-mia is approximately 1 in 4000,9 and approxi-mately 10 percent of cases are bilateral.6,10 Thepossible etiology is thought to relate to hema-toma of the embryonic stapedial artery injur-ing the developing first and second branchialarches.9,11 The expression of craniofacial mi-crosomia is variable, with isolated microtia con-sidered to be a microform of craniofacial mi-crosomia.12 In its fullest expression, thecraniofacial microsomia syndrome is made upof a constellation of congenitally malformedfacial structures arising from the embryonicfirst and second visceral arches, the interven-ing first pharyngeal pouch and first branchialcleft, and the primordia of the temporalbone.13

Murray and colleagues13 suggested thatcraniofacial microsomia is a progressive skele-tal and soft-tissue deformity that worsens overtime. Subsequently, Polley et al.14 performedlongitudinal cephalometric analyses of 26 pa-tients with untreated hemifacial microsomiaand concluded that the deformity is nonpro-gressive and a phenomenon of growth, notworsening disease. More recently, Kearns et

al.15 studied 67 patients with untreated hemifa-cial microsomia and again suggested that theprocess of asymmetry is indeed progressive.Presentations of the disease may vary from sim-ple preauricular skin tags through hypoplasiaor aplasia of skeletal and soft-tissue elements,with management dependent on the severity ofthe defect.16–20

The deformities of craniofacial microsomiacan be broadly considered as being skeletal,auricular, and soft-tissue. Pruzansky19 was thefirst to describe the mandibular deficiency incraniofacial microsomia and identified threetypes:

Type I: Mild hypoplasia of the ramus, andthe body of the mandible is minimally affected.

Type II: Condyle and ramus are small, thehead of the condyle is flattened, the glenoidfossa is absent, the condyle is hinged on a flatand often convex intratemporal surface, andthe coronoid process may be absent.

Type III: Ramus is reduced to a thin lamellaof bone or is completely absent; no evidence ofa temporomandibular joint (Fig. 1).

This classification was modified by Mullikenand Kaban,21 who added a clinically useful sub-division of type II into type IIA (Fig. 2), inwhich the glenoid fossa-condyle relationship ismaintained and the temporomandibular jointis functional, and type IIB, in which the gle-noid fossa-condyle relationship is not main-tained and the temporomandibular joint isnonfunctional. The Kaban classification systemis now widely accepted in classifying mandibu-lar deficiency and is used to determine treat-ment protocols for mandibular deficiencysyndromes.

Munro’s16,18 classification extended the skel-etal anomaly to not only classify the mandiblebut also to include the orbit. This system aimsat providing a basis for surgical reconstructionand consists of five types of skeletal abnormal-ity. Type I shows a complete but hypoplasticfacial skeleton, and types II through V showprogressively severe absence of part of the skel-eton. Type II has an absent mandibular con-dyle and part of the ramus. Type III also lacksthe zygomatic arch and glenoid fossa. In typeIV, the above findings are associated with pos-terior and medial displacement of the lateralorbital wall. Type V further presents with amicro-orbit or an inferiorly displaced orbit.

The auricular deformity of craniofacial mi-

Vol. 110, No. 7 / FACIAL DYSOSTOSES 1715

crosomia was classified by Meurman, who rec-ognized the following three grades of defor-mity: grade I, distinctly smaller malformedauricle but all components are present; gradeII, only a vertical remnant of cartilage and skinis present, with atresia of the external meatus;grade III, complete or nearly complete absenceof the auricle.20,22

Incorporating the skeletal (S), auricular (A),and soft-tissue (T) anomalies, David and col-leagues23 proposed a multisystem classification

of hemifacial microsomia in the tumor, node,metastasis style. The physical manifestations ofhemifacial microsomia are graded accordingto five levels of skeletal deformity (S1 to S5)equivalent to the Pruzansky classification for S1to S3, with S4 representing orbital involvementand S5 representing orbital dystopia. The au-ricular deformity (A0 to A3) is similar to theclassification described by Meurman,20 and thesoft-tissue deficiency (T1 to T3) is graded asmild, moderate, or severe. The SAT system

FIG. 1. (Above, left and right) Severe expression of craniofacial microsomia with Pruzansky typeIII mandibular hypoplasia, severe soft-tissue hypoplasia, and microtia. (Below) Three-dimensionalcomputed tomographic reconstruction shows Pruzansky type III mandibular hypoplasia.

1716 PLASTIC AND RECONSTRUCTIVE SURGERY, December 2002

enables classification of the skeletal, auricular,and soft-tissue deformity and allows a compre-

hensive and staged approach to skeletal andsoft-tissue reconstruction (Fig. 3).

The timing of surgical intervention incraniofacial microsomia must be integrated toaddress the multiple tissue deficiencies. Macro-stomia should be corrected in the first fewmonths of life,24 similar to the timing of cleftlip repair. Most authors14,17–19,25–28 believe thatsurgery for moderate-to-severe craniofacial mi-crosomia should be performed when the childis 5 to 6 years old, rather than waiting until thechild is older and facial growth is complete.The mandibular deformity is usually compen-sated for first. It was believed in the past thatrepositioning the jaw would unlock the growthpotential of the functional matrix to allowmore normal growth of the mandible,29,30 al-though it does remove the abnormal growthtendencies of the maxilla. In mild cases ofmandibular deformity, Posnick24 prefers to waitfor skeletal maturity and uses traditional or-thognathic surgery to achieve favorable aes-thetic results. For mild cases, mandibular sur-gery may involve contour surgery with orwithout genioplasty once skeletal maturity isreached. The advent of distraction osteogene-sis allows early correction of cases of mandibu-lar deformity up to type IIB,31,32 whereas incases of type III deformity, a costochondralgraft is usually indicated, although many au-

FIG. 2. Moderate expression of right craniofacial micro-somia, with deviation of menton to right secondary to man-dibular asymmetry (Pruzansky type IIA), and right microtia.

FIG. 3. SAT classification system for craniofacial microsomia allows classification of the skel-etal (S), auricular (A), and soft-tissue (T) anomalies and provides a treatment plan. (From David,D. J., Mahatumarat, C., and Cooter, R. D. Hemifacial microsomia: A multisystem classification.Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 80: 525, 1987; used with permission.)

Vol. 110, No. 7 / FACIAL DYSOSTOSES 1717

thors have noted unpredictable overgrowth ofcostochondral grafts.8,16–18,27,33

Ross34 reviewed 48 cases of severe craniofa-cial microsomia treated with costochondralgrafts at The Hospital for Sick Children. Thesuccess rates were higher when the childrenwere operated on earlier (85 percent for ages 3to 7 years versus 50 percent for those olderthan 14 years). Equal growth with the othernormal side was seen in 46 percent of cases,undergrowth in 15 percent, and overgrowth in39 percent. Given the option of early or de-layed surgery, the author favors early surgery atage 4 to 5 years, citing a higher graft successrate, the psychosocial advantage of attainingimproved facial symmetry at a younger age,and the additional benefit that erupting teethwill assume a more normal position, makingfuture orthodontic treatment less difficult.

Munro16,18,27 advocates much more exten-sive surgery, operating on the maxilla at thesame time as the mandible. In orbitozygo-matic hypoplasia, Posnick24 performs recon-struction using split cranial bone grafts atage 5 to 7, stating that at age 7 the cranio-orbitozygomatic complex is nearly mature,allowing reconstruction of an adult-sizevault, orbit, and cheekbone. Also, the thick-ness of the calvarium at that age makes for aneasier harvest of split calvarial bone grafts.Ultimately, refinements to the mature skele-ton may be needed, and patients may requiresagittal split osteotomy, Le Fort I osteotomy,or genioplasty to achieve a symmetrical andaesthetic result.24

At times, the soft-tissue deformity in cranio-facial microsomia must also be addressed toattain a long-term aesthetic result, and thisusually follows skeletal reconstruction. Pasttreatment methods have included siliconefluid injections,35 which are contraindicatedbecause of long-term complications, and injec-tions of lipoaspirated fat, which have met withmixed results.36 Autologous fat injections, how-ever, certainly have a place in the correction ofmild contour irregularities. Muscular atrophyof pedicled or free muscle flaps presents aproblem for calculating the final volumeneeded for the repair,37 and microvascular freetissue transfer of dermis fat flaps, as describedby La Rossa et al.38 and Upton et al.,39 is pre-ferred for large-volume soft-tissue deficiencyaugmentation.

GOLDENHAR SYNDROME

The features of Goldenhar syndrome (ocu-loauriculovertebral dysplasia) resemble thoseof craniofacial microsomia except that Golden-har syndrome is characteristically bilateral. Dif-ferentiating features include epibulbar der-moids and vertebral anomalies40 (Fig. 4).Occurrence is believed to be sporadic, withonly a weak genetic component. Managementprotocols are similar to those used in cases ofcraniofacial microsomia.

TREACHER COLLINS SYNDROME

The first reference to mandibulofacial dysos-tosis in the medical literature was made byBerry in 1889. Berry described the physicalsymptoms and speculated about the heritabletransmission of the deformity. His treatise wascertainly much more detailed than the twocases reported 11 years later by Treacher Col-lins, after whom the syndrome was named. InEurope, the deformity is known as the France-schetti-Zwahlen-Klein syndrome on the basis ofthose authors’ 1949 monograph summarizingthe world literature.41 Treacher Collins syn-drome is variably expressed; the incomplete formshould be designated as Treacher Collins syn-

FIG. 4. Goldenhar syndrome. Skeletal deformity similarto craniofacial microsomia (Pruzansky type III mandibularhypoplasia) with residual eyelid deformity following excisionof epibulbar dermoid.

1718 PLASTIC AND RECONSTRUCTIVE SURGERY, December 2002

drome42 and the complete form as Franceschettisyndrome.

Treacher Collins syndrome43 represents amanifestation of the Tessier Nos. 6, 7, and 8clefts. It is inherited as an autosomal dominanttrait with an incidence of 1 in 10,000 livebirths.44 Bilaterality is always present, and al-though phenotypic expression is variable, thedeformity is nearly always symmetrical (Figs. 5and 6). The gene for Treacher Collins syn-drome was identified in 1991, when it wasmapped to chromosome 5 by Dixon and col-leagues45 from a study of 12 families. Later thatyear, the genetic locus was refined to bands5q31.33 q33.3.46

The pathogenesis of Treacher Collins syn-drome remains unknown. Sulik and col-leagues47 were able to produce the facial ab-normalities of Treacher Collins in mice byadministration of isotretinoin, suggesting thatthe syndrome can be triggered by disruption ofvitamin A metabolism. There is also an appar-

ent correlation between frequency of mutationand advanced paternal age.

The typical features of Treacher Collins syn-drome include:

FIG. 5. Treacher Collins syndrome. The skeletal featuresof mandibular hypoplasia are similar to those of craniofacialmicrosomia with a propensity for bilaterality. Note the pal-pebral fissures sloping downward laterally (antimongoloidslant); hypoplasia of the facial bones, especially the malarbones (bilateral presence of zygomas demonstrating variableexpression); malformation of the external ear; and absenceof eyelashes in the medial third of the lower eyelid.

FIG. 6. (Above) A child with Treacher Collins syndromefollowing repair of bilateral lower lid colobomata and bilat-eral mandibular distraction osteogenesis. Note the palpebralfissures sloping downward laterally (antimongoloid slant),with coloboma of the outer portion of the lower lid; hy-poplasia (aplasia) of the facial bones, especially the malarbones and mandible; malformation of the external, middle,and inner ear; atypical hair growth in the form of tongue-shaped processes of the hairline extending toward thecheeks; and absence of eyelashes in the medial third of thelower eyelid. Zygomatic reconstruction with split rib grafts isplanned, followed by bilateral microtia reconstruction. (Be-low) Three-dimensional computed tomographic reconstruc-tion of a patient with Treacher Collins syndrome demon-strating hypoplasia of the facial bones with near total aplasiaof the malar bones.

Vol. 110, No. 7 / FACIAL DYSOSTOSES 1719

• palpebral fissures sloping downward laterally(antimongoloid slant), with coloboma of theouter portion of the lower lid and, rarely, theupper lid

• hypoplasia (aplasia) of the facial bones, es-pecially the malar bones and mandible

• malformation of the external ear and, occa-sionally, the middle and inner ear

• macrostomia, high palate, abnormal posi-tion and malocclusion of the teeth

• blind fistula between the angles of themouth and the ears

• atypical hair growth in the form of tongue-shaped processes of the hairline extendingtoward the cheeks

• absence of eyelashes in at least the medialthird of the lower eyelid

In newborns with the syndrome, the over-whelming priority is airway management.Shprintzen et al.48 noted that some patientshave marked narrowing of the airway (pharyn-geal diameter �1 cm in some cases), and Beh-rents et al.49 described extreme shortening ofthe mandible with severe lower face retrusion.Combined, these malformations can explainthe obstructive sleep apnea and reports of neo-natal death associated with cases of TreacherCollins syndrome. Tracheostomy may be nec-essary, although distraction osteogenesis of themandible in the neonatal period has been usedto avert it.

The eyelid coloboma must be addressed toprotect the cornea. Tessier44 addresses theproblem with a Z-plasty, and Jackson50 uses afull-thickness skin-tarsal plate flap from the up-per lid for reconstruction of the lower lid. Cor-rection of the coloboma must be addressedacutely, and despite the description of multipletechniques to address the problem, an “oper-ated-on look” is hard to avoid.

Primary reconstructive surgery in TreacherCollins syndrome is directed to the maxilla,mandible, and zygoma and to the soft-tissuedeficiencies of the eye, ear, and malar re-gions.51 Pruzansky type I and II mandibulardefects can be corrected with distraction osteo-genesis in children younger than 10 years.Type III defects may require costochondral ribgrafts, which are best performed during themixed dentition phase (age 6 to 10 years).52

Posnick et al.53 augment hypoplastic zygomaswith onlay nonvascularized bone grafts, with-out significant graft resorption or change incontour over time. Others prefer vascularized

calvarial bone flaps54,55 or osteotomy and ad-vancement,56 finding the resorption of nonva-scularized bone to be high. Van der Meulenand associates57 prefer a temporal osteoperios-teal flap, and Psillakis et al.58 describe a tempo-ral aponeurosis-vascularized outer table fascialflap. Autogenous cartilage is the preferredform of auricular reconstruction,59 and soft-tissue augmentation can be performed withdermal grafts60 or free-tissue transfer.38,39

Orthognathic surgery and refinement proce-dures with onlay grafts and soft-tissue augmen-tation can be beneficial to children aged 10 to19 years. Freihofer56 describes a combinationof well-known orthognathic techniques for thecorrection of Treacher Collins syndrome. Thepatients are treated in two to three operativesessions beginning early in the second decadeof life. The main components are chin ad-vancement with concomitant malar osteoto-mies in the first session. In the second opera-tion, the chin prominence is moved furtherforward by simultaneous vertical movement ofthe maxilla, sagittal split osteotomy, and bodyosteotomy of the mandible.

NAGER SYNDROME

The Nager anomaly (acrofacial dysostosis) israre. It is inherited as an autosomal recessivetrait, and patients have craniofacial featuressimilar to mandibulofacial dysostosis, coupledwith preaxial reduction defects of the upperand, sometimes, the lower limbs (Fig. 7). In theupper limbs, there is hypoplasia or agenesis ofthe thumbs and radius and of one or moremetacarpals.61 Unlike in Treacher Collins,lower eyelid colobomas are not as frequent butcleft palate is practically universal. Affected in-dividuals are also typically of short stature andhave subnormal intelligence.62

BINDER SYNDROME

Zuckerkandl in 1882 described an anomalyin the anterior nasal floor in which the normalcrest that separates the nasal floor from theanterior surface of the maxilla was absent and,instead, a small pit (the fossa prenasalis) con-stituted the inferior margin of the piriformaperture.63 In 1939, Noyes64 described a patientwith a flat nasal tip sitting on a retruded max-illonasal base, and in 1962, von Binder65 de-scribed a syndrome consisting of a short nosewith a flat bridge, absent frontonasal angle,absent anterior nasal spine, limited nasal mu-cosa, short columella and acute nasolabial an-

1720 PLASTIC AND RECONSTRUCTIVE SURGERY, December 2002

gle, perialar flatness, convex upper lip, and atendency to class III occlusion. Occasionallythere may be hypoplastic frontal sinuses. VonBinder postulated these defects were caused byrhinocephalic dysplasia, which he called “max-illonasal dysostosis.” Since that time, the con-dition has been known as maxillonasal dyspla-sia or Binder syndrome.66

Posnick and Tompson67 note that the physi-cal findings of Binder syndrome are the resultof hypoplasia (depression) of the anterior na-

sal floor (fossa prenasalis) and localized sym-metric maxillary hypoplasia of the alar rim re-gions. From the basal view, typical variationsfrom normal include a retracted columella-lipjunction; lack of normal triangular flare at thenasal base, a perpendicular alar-cheek junc-tion; convex upper nasal tip with a wide, shal-low philtrum; crescent-shaped nostrils withouta sill; low-set and flat nasal tip; and stretchedand shallow Cupid’s bow (Figs. 8 and 9).68 Themost striking characteristics of the nose arevertical shortening, lack of tip projection, peri-alar flattening, and an acute nasolabial angle.Holmstrom68 found a hereditary connection in16 percent of 50 patients with Binder syn-drome, and inheritance may be as an autoso-mal recessive trait with incomplete pene-trance.69,70

Surgical correction of the deformities ofBinder syndrome is complex.67,71 Techniquesfor nasal reconstruction aim at increasing nasallength and tip projection and have been de-scribed by Posnick and Tompson,67 Holm-strom,71 Jackson et al.,72 and Banks and Tan-

FIG. 7. (Above) A child with severe Nager syndrome ex-hibiting bilateral mandibular hypoplasia with micrognathia,resulting in airway obstruction necessitating tracheostomy.(Below) Three-dimensional computed tomography scan re-construction of the child at 12 months of age shows theseverity of micrognathia.

FIG. 8. (Above) The nose and upper lip in maxillonasaldysplasia. 1, retracted columella-lip junction and lack of tri-angular flare at the base; 2, perpendicular alar-cheek junc-tion; 3, convex and wide upper lip with a shallow philtrum;4, crescent-shaped nostril without nostril sill; 5, low-set andflat nasal tip; 6, stretched and shallow Cupid’s bow. (Below)Surgical correction is by medial rotation of tissues on eitherside of the midline. [From Holmstrom, H. Clinical andpathologic features of maxillonasal dysplasia (Binder syn-drome): Significance of the prenasal fossa on etiology. Plast.Reconstr. Surg. 78: 559, 1986; used with permission.]

Vol. 110, No. 7 / FACIAL DYSOSTOSES 1721

ner.73 Reconstructive options include Le Fort IIosteotomy, Le Fort I osteotomy, a combinationof Le Fort II and I osteotomies, compensatoryorthodontic alignment of the teeth, and in-fraorbital rim augmentation.66,71,72,74–80 Nasalreconstruction may involve both autogenousand homogenous bone and cartilage grafts ex-tending up the columella and over the dorsum,from the radix to the tip.

Disappointing long-term results thought tobe caused by bone graft resorption were chal-lenged by Rune and Aberg.81 They followed up11 patients for 40 months and found a reduc-tion of graft length of 28 percent. Despite this,there was no alteration in the achieved im-provement in nasal length or tip projection.

Banks and Tanner73 approach the nasal de-formity in Binder syndrome by lifting the facialmask through a coronal incision and reachingthe nasal floor through an incision in the up-per buccal sulcus. The nasal soft tissues, includ-ing the alar cartilages, are mobilized. The noseis lengthened and tip projection is achievedwith a cantilever graft of lyophilized cartilage.

Wolfe82 describes a technique of nasofrontalosteotomy to lengthen the nose in cases of

posttraumatic shortening and Binder syn-drome. McCollum et al.83 review the literatureand provide long-term follow-up of two pa-tients—one treated with traditional orthog-nathic surgery and the other with a growthcenter implant to the nose.

PIERRE ROBIN SEQUENCE

In 1923, Pierre Robin, a French stomatolo-gist, identified the physical characteristics of acombination of anomalies that were once con-sidered a syndrome but are known now as thePierre Robin sequence.84 The characteristicfeatures of the Pierre Robin sequence are ret-rogenia, glossoptosis, and airway obstruction(Fig. 10).1,84 Although many infants with PierreRobin sequence have micrognathia, Ran-dall85,86 points out that retrogenia better de-scribes the condition of the jaws in the disorderbecause it is the posterior displacement of thechin that predisposes to glossoptosis. An asso-ciated high-arched midline cleft of the softpalate and, occasionally, of the hard palate isalso present in about 50 percent of cases.87,88

The sequence shows great etiologic heteroge-neity, with as many as 18 associated syndromes.

FIG. 9. Binder syndrome. Note the short nasal length and lack of tip projection associated witha short columella (left). On basal view (right), note the retracted columella-lip junction and lackof triangular flare at the base, a perpendicular alar-cheek junction, convex and wide upper lipwith a shallow philtrum, crescent-shaped nostril without nostril sill, low-set and flat nasal tip, andstretched and shallow Cupid’s bow.

1722 PLASTIC AND RECONSTRUCTIVE SURGERY, December 2002

The glossoptosis in Pierre Robin sequencecan begin a vicious sequence of events, withairway obstruction, increased energy expendi-ture, and decreased caloric intake from im-paired feeding. Afflicted infants typically fail tothrive because of respiratory and feeding diffi-culties, and if these problems are ignored, car-diac failure and death may ensue.

In 1946, Douglas89 reported a greater than50 percent mortality rate with conservativetreatment of Pierre Robin sequence. It is nowclear that the key to successful medical treat-ment of infants with Pierre Robin sequence isto hold the infant prone to relieve the glossop-tosis and open the airway. In some cases, thisposition must be maintained 24 hours a day,even during feeding, baths, and diaperchanging.90

Although most infants can be successfullytreated conservatively, a few will require surgi-cal intervention. If medical treatment failed torelieve the symptoms of airway obstruction, theinfant previously would have been consideredfor tongue-lip adhesion or tracheostomy.85,91

The advent of distraction osteogenesis pro-vides an alternative for addressing airway ob-struction. Denny et al.92 describe a series of 10patients who were treated with distraction os-teogenesis of the mandible. Two of three pa-tients with indwelling tracheostomies were suc-cessfully decannulated within 6 weeks. Allchildren showed clinical improvement aftermandibular distraction, with a mean effectiveairway increase after distraction of 67.5percent.

P. Craig Hobar, M.D.Department of Plastic and Reconstructive SurgeryUniversity of Texas Southwestern Medical Center411 N. Washington AvenueSuite 6000, LB 13Dallas, Texas [email protected]

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Marco A. Medina, Clinical Photogra-pher, and Leesa Thompson, Craniofacial Coordinator, TheFogelson Plastic Surgery and Craniofacial Center for Chil-dren, Dallas, Texas, for their invaluable assistance and con-tributions to this article.

REFERENCES

1. Gorlin, R. J., Pindborg, J. J., and Cohen, M. M. Syndromesof the Head and Neck, 2nd Ed. New York: McGraw-Hill,1976.

2. Gorlin, R. J. Classification of craniofacial syndromes. InJ. M. Converse and J. G. McCarthy (Eds.), Symposiumon the Diagnosis and Treatment of Craniofacial Anomalies.St. Louis: Mosby, 1979.

3. Whitaker, L. A., Pashayan, H., and Reichman, J. A pro-posed new classification of craniofacial anomalies.Cleft Palate J. 18: 161, 1981.

4. Tessier, P. Anatomical classification of facial, cranio-facialand latero-facial clefts. J. Maxillofac. Surg. 4: 69, 1976.

5. van der Meulen, J. C., Mazzola, R., Vermey-Keers, C.,Stricker, M., and Raphael, B. A morphogenetic clas-sification of craniofacial malformations. Plast. Recon-str. Surg. 71: 560, 1983.

6. Thomson, A. Cited by Grabb, W. C. The first and sec-ond branchial arch syndrome. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 36:485, 1965.

7. Posnick, J. C. Hemifacial microsomia: Evaluation andstaging of reconstruction. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 56:642, 1998.

8. Bassila, M., and Goldberg, R. The association of facialpalsy and sensorineural hearing loss in patients withhemifacial microsomia. Cleft Palate J. 26: 287, 1989.

9. Poswillo, D. The pathogenesis of the first and secondbranchial arch syndrome. Oral Surg. Oral Med. OralPathol. 35: 302, 1973.

10. Converse, J. M., Edgerton, M. T., and Marsh, J. L. Bi-lateral facial microsomia: Diagnosis, classification, andtreatment. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 59: 653, 1977.

11. McKenzie, J., and Craig, J. Mandibulofacial dysostosis.Arch. Dis. Child. 30: 391, 1952.

12. Johnston, M. C., and Sulik, K. K. Embryology of the headand neck. In D. Serafin and N. G. Georgiade (Eds.),Pediatric Plastic Surgery, Vol. 1. St. Louis: Mosby, 1984.

13. Murray, J. E., Kaban, L. B., Mulliken, J. B., and Evans,C. A. Analysis and treatment of hemifacial microso-mia. In E. P. Caronni (Ed.), Craniofacial Surgery. Bos-ton: Little, Brown, 1982.

14. Polley, J. W., Figueroa, A. A., Liou, E. J. W., and Cohen, M.Longitudinal analysis of mandibular asymmetry in hemi-facial microsomia. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 99: 328, 1997.

15. Kearns, G. J., Padwa, B. L., Mulliken, J. B., and Kaban,L. B. Progression of facial asymmetry in hemifacialmicrosomia. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 105: 492, 2000.

16. Munro, I. R. Treatment of craniofacial microsomia.Clin. Plast. Surg. 14: 177, 1987.

FIG. 10. Four-month-old child with Pierre Robin se-quence exhibiting retrognathia and micrognathia, resultingin glossoptosis and airway obstruction that necessitated tra-cheostomy and nasogastric feeding tube.

Vol. 110, No. 7 / FACIAL DYSOSTOSES 1723

17. Murray, J. E., Kaban, L. B., and Mulliken, J. B. Analysisand treatment of hemifacial microsomia. Plast. Recon-str. Surg. 74: 186, 1984.

18. Munro, I. R. One-stage reconstruction of the temporo-mandibular joint in hemifacial microsomia. Plast. Re-constr. Surg. 66: 699, 1980.

19. Pruzansky, S. Not all dwarfed mandibles are alike. BirthDefects 5: 120, 1969.

20. Meurman, Y. Congenital microtia and meatal atresia.Arch. Otolaryngol. 66: 443, 1957.

21. Mulliken, J. B., and Kaban, L. B. Analysis and treatmentof hemifacial microsomia in childhood. Clin. Plast.Surg. 14: 91, 1987.

22. Bennun, R. D., Mulliken, J. B., Kaban, L. B., and Murray,J. E. Microtia: A microform of hemifacial microso-mia. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 76: 859, 1985.

23. David, D. J., Mahatumarat, C., and Cooter, R. D. Hemi-facial microsomia: A multisystem classification. Plast.Reconstr. Surg. 80: 525, 1987.

24. Posnick, J. C. Surgical correction of mandibular hyp-oplasia in hemifacial microsomia: A personal perspec-tive. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 56: 639, 1998.

25. Converse, J. M., Horowitz, S. L., Coccaro, P. J., and Wood-Smith, D. The corrective treatment of the skeletalasymmetry in hemifacial microsomia. Plast. Reconstr.Surg. 52: 221, 1973.

26. Ortiz-Monasterio, F. Early mandibular and maxillary os-teotomies for the correction of hemifacial microsomia:A preliminary report. Clin. Plast. Surg. 9: 509, 1982.

27. Munro, I. R., and Lauritzen, C. G. K. Classification andtreatment of hemifacial microsomia. In E. P. Caronni(Ed.), Craniofacial Surgery. Boston: Little, Brown, 1984.

28. Ortiz-Monasterio, F., and Fuente del Campo, A. Earlyskeletal correction of hemifacial microsomia. In E. P.Caronni (Ed.), Craniofacial Surgery. Boston: Little,Brown, 1984.

29. Moss, M. L. The functional matrix. In B. S. Kraus andR. A. Reidel (Eds.), Vistas in Orthodontics. Philadelphia:Lea and Febiger, 1962.

30. Moss, M. L., Bromberg B. E., Song, I. C., and Eisenman,G. The passive role of nasal septal cartilage in mid-facial growth. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 41: 536, 1968.

31. McCarthy, J. G., Schreiber, J., Karp, N., Thorne, C. H., andGrayson, B. H. Lengthening the human mandible bygradual distraction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 89: 1, 1992.

32. Molina, F., and Ortiz Monasterio, F. Mandibular elon-gation and remodeling by distraction: A farewell formajor osteotomies. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 96: 825, 1995.

33. McCarthy, J. G., Grayson, B. H., Coccaro, P. J., and Wood-Smith, D. Craniofacial microsomia. In J. G. Mc-Carthy (Ed.), Plastic Surgery, Vol. 5. Philadelphia:Saunders, 1990.

34. Ross, R. B. Costochondral grafts replacing the mandib-ular condyle. Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 36: 334, 1999.

35. Rees, T. D., Ashley, F. L., and Delgado, J. P. Siliconefluid injections for facial atrophy: A 10-year study.Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 52: 118, 1973.

36. de la Fuente, A., and Tavora, T. Fat injections for thecorrection of facial lipodystrophies: A preliminary re-port. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 12: 39, 1988.

37. de la Fuente, A., and Jimenez, A. Latissimus dorsi freeflaps for restoration of facial contour defects. Ann.Plast. Surg. 22: 1, 1989.

38. La Rossa, D., Whitaker, L., Dabb, R., and Mellissinos, E.The use of microvascular free flaps for soft tissue aug-

mentation of the face in children with hemifacial mi-crosomia. Cleft Palate J. 17: 138, 1980.

39. Upton, J., Mulliken, J. B., Hicks, P. D., and Murray, J. E.Restoration of facial contour using free vascularizedomental transfer. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 66: 560, 1980.

40. Cohen, M. M., Jr., Rollnick, B. R., and Kaye, C. I. Ocu-loauriculovertebral spectrum: An updated critique.Cleft Palate J. 26: 276, 1989.

41. Rogers, B. O. Berry-Treacher Collins syndrome: A re-view of 200 cases. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 17: 109, 1964.

42. Munro, I. R., Kay, P. P., Randell, P., Ruff, G. L., andSiebert, J. W. Craniofacial syndromes. In J. G. Mc-Carthy (Ed.), Plastic Surgery, Vol. 4. Philadelphia:Saunders, 1990.

43. McCarthy, J. G., and Zide, B. M. Rare craniofacial clefts.In D. Serafin and N. G. Georgiade (Eds.), PediatricPlastic Surgery, Vol. 1. St. Louis: Mosby, 1984.

44. Tessier, P. Surgical correction of Treacher Collins syn-drome. In W. H. Bell (Ed.), Modern Practice in Orthog-nathic and Reconstructive Surgery, Vol. 2. Philadelphia:Saunders, 1992.

45. Dixon, M. J., Read, A. P., Donnai, C., Colley, A., Dixon,J., and Williamson, R. The gene for Treacher Collinssyndrome maps to the long arm of chromosome 5.Am. J. Hum. Genet. 49: 17, 1991.

46. Jabs, E. W., Li, X., Coss, C. A., Taylor, E. W., Meyers, D. A.,and Weber, J. L. Mapping the Treacher Collins syn-drome locus to 5q31.33q33.3 Genomics 11: 193, 1991.

47. Sulik, K. K., Johnston, M. C., Smiley, S. J., Speight, H. S.,and Jarvis, B. E. Mandibulofacial dysostosis(Treacher Collins syndrome): A new proposal for itspathogenesis. Am. J. Med. Genet. 27: 359, 1987.

48. Shprintzen, R. J., Croft, C., Berkman, M. D., and Rakoff,S. J. Pharyngeal hypoplasia in Treacher Collins syn-drome. Arch. Otolaryngol. 105: 127, 1979.

49. Behrents, R. G., McNamara, J. A., and Avery, J. K. Pre-natal mandibulofacial dysostosis (Treacher Collinssyndrome). Cleft Palate J. 14: 13, 1977.

50. Jackson, I. T. Reconstruction of the lower eyelid defectin Treacher Collins syndrome. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 67:365, 1981.

51. Raulo, Y. Treacher Collins syndrome: Analysis and prin-ciples of surgery. In E. P. Caronni (Ed.), CraniofacialSurgery. Boston: Little, Brown, 1984.

52. Posnick, J. C. Treacher Collins syndrome. In S. Aston(Ed.), Grabb and Smith’s Plastic Surgery, 5th Ed. Phila-delphia: Lippincott Raven, 1997.

53. Posnick, J. C., Goldstein, J. A., and Waitzman, A. A. Sur-gical correction of the Treacher Collins malar defi-ciency: Quantitative CT scan analysis of long-term re-sults. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 92: 12, 1993.

54. McCarthy, J. G., and Zide, B. M. The spectrum of cal-varial bone grafting: Introduction of the vascularizedcalvarial bone flap. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 74: 10, 1984.

55. McCarthy, J. G., Cutting, C. B., and Shaw, W. W. Vas-cularized calvarial flaps. Clin. Plast. Surg. 14: 37, 1987.

56. Freihofer, H. P. M. Variations in the correction ofTreacher Collins syndrome. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 99:647, 1997.

57. van der Meulen, J. C., Hauben, D. J., Vaandrager, J. M.,and Birgenhager-Frenkel, D. H. The use of a tem-poral osteoperiosteal flap for the reconstruction ofmalar hypoplasia in Treacher Collins syndrome. Plast.Reconstr. Surg. 74: 687, 1984.

58. Psillakis, J. M., Grotting, J. C., Casanova, R., Cavalcante,

1724 PLASTIC AND RECONSTRUCTIVE SURGERY, December 2002

D., and Vasconez, L. O. Vascularized outer-tablecalvarial bone flaps. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 78: 309, 1986.

59. Brent, B. Auricular repair with autogenous rib cartilagegrafts: Two decades of experience with 600 cases. Plast.Reconstr. Surg. 90: 355, 1992.

60. Dufresne, C. Treacher Collins syndrome. In C. Duf-resne (Ed.), Complex Craniofacial Problems: A Guide toAnalysis and Treatment. New York: Churchill Living-stone, 1992.

61. Munro, I. R., Randell, P., Ruff, G. L., and Siebert, J. W.Craniofacial syndromes. In J. G. McCarthy (Ed.), Plas-tic Surgery, Vol. 4. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1990.

62. Jackson, I. T., Bauer, B., Saleh, J., Sullivan, C., and Argenta,L. C. A significant feature of Nager’s syndrome: Palatalagenesis. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 84: 219, 1989.

63. Zuckerkandl, E. Fossae praenasales: Normale und pa-thologische. Anat. Nasenhohle 1: 48, 1882.

64. Noyes, F. B. Case report. Angle Orthod. 9: 160, 1939.65. Von Binder, K. H. Dysostosis maxillo-nasalis, ein arhi-

nencephaler Missbildungskomplex. Deutsche Zahnaer-ztl. Z. 17: 438, 1962.

66. Munro, I. R., Sinclair, W. J., and Rudd, N. L. Maxillo-nasal dysplasia (Binder’s syndrome). Plast. Reconstr.Surg. 63: 657, 1979.

67. Posnick, J. C., and Tompson, B. Binder syndrome: Stag-ing of reconstruction and skeletal stability and relapsepatterns after Le Fort I osteotomy using miniplatefixation. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 99: 961, 1997.

68. Holmstrom, H. Clinical and pathologic features of max-illonasal dysplasia (Binder’s syndrome): Significanceof the prenasal fossa on etiology. Plast. Reconstr. Surg.78: 559, 1986.

69. Rival, J. M., Gherga-Negrea, A., Mainard, R., and Delaire,J. Dysostose maxillo-nasale de Binder. J. Genet. Hum.22: 263, 1974.

70. Olow-Nordenram, M., and Valentin, J. An etiologicstudy of maxillonasal dysplasia: Binder’s syndrome.Scand. J. Dent. Res. 96: 69, 1988.

71. Holmstrom, H. Surgical correction of the nose andmidface in maxillonasal dysplasia (Binder’s syn-drome). Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 78: 568, 1986.

72. Jackson, I. T., Moos, K. F., and Sharpe, D. T. Totalsurgical management of Binder’s syndrome. Ann.Plast. Surg. 7: 25, 1981.

73. Banks, P., and Tanner, B. The mask rhinoplasty: A tech-nique for the treatment of Binder’s syndrome andrelated disorders. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 92: 1038, 1993.

74. Converse, J. M. Restoration of facial contour by bonegrafts introduced through the oral cavity. Plast. Recon-str. Surg. 6: 295, 1950.

75. Converse, J. M., Horowitz, S. L., Valauri, A. J., and Mon-tandon, D. The treatment of nasomaxillary hypopla-sia: A new pyramidal naso-orbital maxillary osteotomy.Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 45: 527, 1970.

76. Ragnell, A. Nasomaxillary retroposition in children.Successive reconstruction of the nose: A preliminaryreport. Nord. Med. 77: 847, 1967.

77. Henderson, D., and Jackson, I. T. Naso-maxillary hyp-oplasia: The Le Fort II osteotomy. Br. J. Oral Surg. 11:77, 1973.

78. Steinhauser, E. W. Variations of Le Fort II osteotomiesfor correction of midfacial deformities. J. Maxillofac.Surg. 8: 258, 1980.

79. Tessier, P., Tulasne, J. F., Delaire, J., and Resche, F.Therapeutic aspects of maxillonasal dysostosis (Bind-er syndrome). Head Neck Surg. 3: 207, 1981.

80. Holmstrom, H., and Kahnberg, K. E. Surgical approachin severe cases of maxillonasal dysplasia (Binder’s syn-drome). Swed. Dent. J. 12: 3, 1988.

81. Rune, B., and Aberg, M. Bone grafts to the nose inBinder’s syndrome (maxillonasal dysplasia): A fol-low-up of eleven patients with the use of profile roent-genograms. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 101: 297, 1998.

82. Wolfe, S. A. Lengthening the nose: A lesson fromcraniofacial surgery applied to posttraumatic and con-genital deformities. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 94: 78, 1994.

83. McCollum, A. G. H., and Wolford, L. M. Binder syn-drome: Literature review and long-term follow-up ontwo cases. Int. J. Adult Orthod. Orthognath. Surg. 13: 45,1998.

84. Robin, P. Backward fall of the root of the tongue ascause of respiratory disturbances. Bull. Acad. Med. (Par-is) 89: 37, 1923.

85. Randall, P. The Robin sequence: Micrognathia andglossoptosis with airway obstruction. In J. G. McCarthy(Ed.), Plastic Surgery, Vol. 4. Philadelphia: Saunders,1990.

86. Randall, P., Krogman, W. M., and Jahina, S. PierreRobin and the syndrome that bears his name. CleftPalate J. 2: 237, 1965.

87. Fletcher, M. M., Blum, S. L., and Blanchard, C. L. PierreRobin syndrome pathophysiology of obstructive epi-sodes. Laryngoscope 79: 547, 1969.

88. Kiskadden, W. S., and Dietrich, S. R. Review of thetreatment of micrognathia. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 12:365, 1953.

89. Douglas, B. The treatment of macrognathia associatedwith obstruction by a plastic procedure. Plast. Reconstr.Surg. 1: 300, 1946.

90. Pashayan, H. M., and Lewis, M. B. Clinical experiencewith the Robin sequence. Cleft Palate J. 21: 270, 1984.

91. Routledge, R. T. The Pierre Robin syndrome: A surgicalemergency in the neonatal period. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 13:204, 1960.

92. Denny, A. D., Talisman, R., Hanson, P. R., and Recinos,R. F. Mandibular distraction osteogenesis in veryyoung patients to correct airway obstruction. Plast.Reconstr. Surg. 108: 302, 2001.

Self-Assessment Examination follows onthe next page.

Vol. 110, No. 7 / FACIAL DYSOSTOSES 1725

Self-Assessment Examination

Common Craniofacial Anomalies: The Facial Dysostosesby Jeremy A. Hunt, M.D., and P. Craig Hobar, M.D.

1. WHICH OF THE FOLLOWING IS CHARACTERISTIC OF TREACHER COLLINS SYNDROME?A) Autosomal recessiveB) BilateralityC) MicrostomiaD) Mongoloid slant of palpebral fissureE) Frontal bossing

2. THE MAJOR DIFFERENCES BETWEEN THE FACIAL ANOMALIES IN NAGER’S SYNDROME AND TREACHERCOLLINS SYNDROME IS:A) Auricular deformityB) Facial bone hypoplasiaC) Cleft palateD) ColobomaE) Antimongoloid slant of palpebral fissure

3. WHICH OF THE FOLLOWING IS THE PRIMARY DIFFERENTIATOR BETWEEN CRANIOFACIALMICROSOMIA AND GOLDENHAR SYNDROME?A) Degree of mandibular involvementB) Extent of auricular involvementC) Presence of macrostomiaD) BilateralityE) Presence of coloboma

4. WHICH OF THE FOLLOWING COMPONENTS OF CRANIOFACIAL MICROSOMIA SHOULD BECORRECTED FIRST?A) Auricular deformityB) MacrostomiaC) Mandibular ramus deficiencyD) Mandibular body deficiencyE) Temporal mandibular joint abnormalities

5. IN THE MAJORITY OF PATIENTS WITH PIERRE ROBIN SEQUENCE, AIRWAY OBSTRUCTION CAN BESUCCESSFULLY MANAGED WITH:A) Prone positioningB) Oral-tracheal intubationC) Lip-tongue adhesionD) TracheostomyE) Mandibular distraction

6. THE PHYSICAL FINDINGS IN BINDER’S SYNDROME ARE PRIMARILY ATTRIBUTABLE TO HYPOPLASIAOF THE:A) Medial orbital wallB) Anterior wall of the maxillaC) Nasal septumD) Anterior nasal floorE) Anterior cranial base

To complete the examination for CME credit, turn to page 1824 for instructions and the response form.