HERBERT HOOVER DIKE Herbert Hoover Dike REHABILITATION PROGRAM

Ciclo Hoover

-

Upload

sol-freyre -

Category

Documents

-

view

240 -

download

1

description

Transcript of Ciclo Hoover

-

Applied Intermediate Macroeconomics Draft 2, 24 March 2005 Chapter 5 Trends and Cycles Word Count: 6210 2004 Kevin D. Hoover, All Rights Reserved AWL Page Equivalent 11

1

5 Trends and Cycles

The last three chapters focused on the measurement of key national accounting variables:

GDP and prices. While these are the centerpiece of macroeconomic analysis, there are

thousands of other measures of the economy most related in one way or another to

GDP and its components. In this chapter, we begin a wider examination of the economy,

shifting our focus to the question, how do GDP and large variety of other economic

variables behave over time? We begin by dividing their movements into longer run

trends and shorter run cycles. We then ask, are the cycles in different variables are

closely related in an economy-wide business cycle? And, finally, what are the properties

of the business cycle?

5.1 Decomposing Time Series

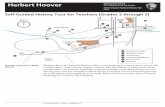

Look back at Figure 2.10, 2.12, or 2.14. Each shows the path of U.S. real GDP over a

period of about fifty years. Two characteristics of these graphs stands out. First, the

dominant movement of U.S. GDP is upward. But, second, the dominant movement is

unsteady: there are frequent and, at best, roughly regular ups and downs. A large

proportion of the thousands of economic time series that describe the economy behave

similarly. Take three examples: Figure 5.1 shows the time series for personal disposable

income (less transfers), industrial production, and employment. Each one resembles

GDP; each displays a pattern of fluctuations around a dominant upward path.

The economist often finds it useful to distinguish the dominant path, known as the

TREND, from the fluctuations, known as the CYCLE, because distinct factors explain each.

-

Source: Personal income, Bureau of Economic Analysis; industrial production, Federal Reserve; employment, Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Figure 5.1 Trends and Cycles in Selected Times Series

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

400

450

1959

1961

1963

1965

1967

1969

1971

1973

1975

1977

1979

1981

1983

1985

1987

1989

1991

1993

1995

1997

1999

2001

2003

I

n

d

e

x

N

u

m

b

e

r

(

1

9

5

9

:

0

1

=

1

0

0

)

Employment

Industrial Production

Personal Income (less transfers)

Like real GDP many economic time series show a pattern of fluctuations (a cycle) around an underlying growth path (a trend).

-

Applied Intermediate Macroeconomics Draft 2, 24 March 2005 Chapter 5 Trends and Cycles Word Count: 6210 2004 Kevin D. Hoover, All Rights Reserved AWL Page Equivalent 11

2

Most of the later chapters of this book aim to explain the trend (especially Chapters 6 and

7) or the cycle (especially Chapters 9 and 12-16).

The upper panel of Figure 5.2 shows a stylized version of an economic time

series, which cycles regularly about a smooth exponential trend. The time series may be

decomposed in two steps: first, estimate the trend and, second, express the fluctuations

as deviations from the trend. The lower panel shows the cycle, now measured as the

difference between the time series and its trend expressed as a percentage of the trend.

Displaying the cycle as percentage of the trend makes sense: although the fluctuations of

an economic variable are likely to be absolutely smaller when its average value is small,

there is no reason to believe that they will be relatively smaller than when its absolute

value is large.

As we saw in Chapter 2, it is sometimes convenient to display economic time

series on logarithmic graphs. Figure 5.3 displays the same information as Figure 5.2

using a logarithmic scale. The exponential trend becomes a linear trend. The lower

panel shows the difference log(time series) log(trend). Since the difference in

logarithms is a ratio, just like a percentage difference, the lower panel is qualitatively

identical to the lower panel in Figure 5.2. And, if we multiply by 100, it too can be read

in percentage points. (See Box 2.3 and the Guide, section G.11, on logarithms and

logarithmic graphs.) The key to decomposing any time series into its trend and cycle is

the identification of the trend. Box 5.1 discusses some useful methods for estimating

trends.

In either the original or the logarithmic representation, a local high point is a

CYCLICAL PEAK and a local valley is a CYCLICAL TROUGH (rhymes with off). A

-

Figure 5.2The Trend and Cycle of Stylized Economic Time Series

Time

V

a

l

u

e

(

o

r

i

g

i

n

a

l

u

n

i

t

s

)

V

a

l

u

e

(

p

e

r

c

e

n

t

a

g

e

o

f

t

r

e

n

d

)

Peak

Trough

Trend

0

Detrended Series(right axis)

Original Series(left axis)

Peak

Peak

Trough

Trough

The detrended series is the difference between the trend and the original series expressed as a percentage of the trend.

Peaks and troughs of the original series are also the peaks and troughs of the detrended series.

Deviation from trend

-

Figure 5.3The Trend and Cycle of a Stylized Economic Time Series:

A Logarithmic Version

Time

V

a

l

u

e Peak

0

Detrended Series

Original Series

log scale

The detrended series is the difference between the trend and the original series . Since the difference of logarithms is a ratio, the detrended series can be interpreted as a percentage of the original trend series.

Peaks and troughs of the original series are also the peaks and troughs of the detrended series.

Peak

Peak

Trough

Trough

Trough

-

Applied Intermediate Macroeconomics Draft 2, 2 April 2005 Chapter 5 Trends and Cycles, BOX 5.1 Word Count: 961 2004 Kevin D. Hoover, All Rights Reserved

Box 5.1. Working with Economic Data: Detrending Time Series

The distinction between trend and cycle is not given in nature. There is no one right way

to detrend a time series. The question is not one of right or wrong, but of useful or not

useful. Does it help us to see more clearly what is happening in the economy? In this

book, we will use three of the many methods of detrending.

The Constant Trend

If we believe that, despite cyclical fluctuations, the average growth rate of a series does

not change much over a long period, then it is reasonable to assume that the trend has a

constant rate of growth and can be described by an equation

trend = a(1 + b)t

or

trend = aexp(bt),

where t is time, and a and b are constants. Each equation describes exponential growth at

a constant rate, b. The trend line in Figure 5.2 can be described by these equations.

Box 5.1 1

The difference between the time series and the trend is

-

Applied Intermediate Macroeconomics Draft 2, 2 April 2005 Chapter 5 Trends and Cycles, BOX 5.1 Word Count: 961 2004 Kevin D. Hoover, All Rights Reserved

deviation from trend = time series trend

= time series a(1 + b)t

or

= time series aexp(bt).

At each period, there is a different deviation from trend (see Figure 5.2).

If we knew the values of the constants a and b, we could calculate the values of

each of the deviations and the variance of those deviations. We can calculate the

variance of these deviations (see the Guide, section G.4.2). Different values for a and b

would give us different sets of deviations and different variances. One rule for choosing

the trend is to pick values for a and b that maximize portion of the change in the time

series attributed to the trend, minimizing the portion attributed to the cycle. This is

equivalent to choosing a and b such that the variance of the deviations is as small as

possible. Fortunately, common spreadsheets (such as Excel) can do this at the click of

mouse (see the Guide, section G.15).

Box 5.1 2

If a time series grows at a steady proportionate rate, then log(time series) will

grow at a steady absolute rate as in Figure 5.3. The trend is then described by a linear

function, not an exponential function:

-

Applied Intermediate Macroeconomics Draft 2, 2 April 2005 Chapter 5 Trends and Cycles, BOX 5.1 Word Count: 961 2004 Kevin D. Hoover, All Rights Reserved

trend = a + bt.

The method of finding the trend by choosing a and b to minimize the variance of the

deviations remains the same. Linear trends arise naturally when we consider the

logarithms of steadily growing data, but may also be appropriate even for natural data

that do not grow exponentially.

The Moving-Average Trend

In Chapter 2 (especially Figures 2.11 and 2.12) we saw that average growth rates were

not constant decade by decade. In such cases, a constant trend may not be appropriate.

We could perhaps use the average growth rate each decade to approximate the trend. But

that would imply, wrongly, that decades were somehow natural breaks. Instead, we can

calculate a centered moving average. Suppose that we have annual data on real GDP

from 1960 to 2006. A five-year centered moving average would start in 1962 would

average the value for 1962 with the values for two years before and two years after:

trend1962 = 56463626160 YYYYY ++++ .

In 1963, the moving average would drop Y60 and add Y65:

Box 5.1 3

trend1963 = 56564636261 YYYYY ++++ ,

-

Applied Intermediate Macroeconomics Draft 2, 2 April 2005 Chapter 5 Trends and Cycles, BOX 5.1 Word Count: 961 2004 Kevin D. Hoover, All Rights Reserved

and so on until 2004.

One disadvantage, of course, is that the centered moving average cannot start

right at the beginning of the sample and must end before the end of the sample in order to

accommodate the leading and lagging terms. Centered moving averages should have an

odd number of terms, to preserve symmetry. The narrower the window (i.e., the number

of periods in the average), the more fluctuations the trend will display. There is no one

right choice of window, but for detrending economic time series, a fairly long window is

appropriate. The 25-quarter window used in Figure 5.4 approximates the average length

of the U.S. business cycle, ensuring that the trend averages both upswings and

downswings at every point.

Differences and Growth Rates

The previous two methods truly decompose the trend and the cycle into separate parts.

Sometimes we may not really care about the trend but just want to focus on fluctuations.

This is easily done by taking the first difference of the data:

Xt = Xt Xt-1.

More commonly, we calculate the proportional first difference, which is just the growth

rate:

Box 5.1 4

1

1

1

==t

tt

t

tt X

XXX

XX .

-

Applied Intermediate Macroeconomics Draft 2, 2 April 2005 Chapter 5 Trends and Cycles, BOX 5.1 Word Count: 961 2004 Kevin D. Hoover, All Rights Reserved

Figure B5.1 shows a time series that has been detrended by calculating growth

rates. Notice that differencing a time series (or calculating a growth rate) causes a phase

shift: When the original time series is falling, its growth rate is negative; when the level

time series is rising, the growth rate is positive. The growth rate reaches its peak one-

quarter cycle ahead of the original series. This makes sense. When the level is exactly at

its peak or exactly at its trough it is neither rising nor falling, so its growth rate must be

zero. After one of these extreme points, it changes faster for a while and then slows

down to no change just at the next extreme point. Its growth rate must, therefore, reach

its fastest absolute value between the peak and the trough of the level series. What this

means economically is that we cannot judge the peak or trough of economic activity from

the peak or trough of the growth rate of GDP, but instead from noting when that growth

switched from positive or negative or back to positive. Growth rates should be fastest

somewhere in the middle of economic expansions and slow to nothing at the cyclical

peaks and troughs, and should reach their most extreme negative rates somewhere in the

middle of recessions.

Box 5.1 5

See the Guide, section G.12, for more on detrending time series.

-

Figure B5.1A Stylized Time Series and in Levels and Percentage Changes

Time

L

e

v

e

l

G

r

o

w

t

h

R

a

t

e

0

Times Series in Levels(left axis)

Time Series in Percentage Changes(right axis)

Peak

Peak

Peak

Trough

Trough

Trough

Plotting the growth rate of a time series shifts its phase .: The peaks and troughs of the original series occur when the growth rates are zero, while the fastest positive and negative growth rates (the peaks and troughs of the growth -rate series) occur one quarter cycle later in mid-expansion and mid-recession.

-

Applied Intermediate Macroeconomics Draft 2, 24 March 2005 Chapter 5 Trends and Cycles Word Count: 6210 2004 Kevin D. Hoover, All Rights Reserved AWL Page Equivalent 11

3

complete CYCLE can be measured from peak to peak or from trough to trough.

Sometimes the trend growth is referred to as secular change (or growth) to distinguish it

from cyclical fluctuations.

Of course, Figures 5.2 and 5.3 are only stylizations. Compare Figure 5.2 to

Figure 5.4, which shows actual real GDP and its trend in the upper part and the

percentage deviations from trend below for the 1970s. The graphs of actual data are not

so regular as the stylized graphs, but the overall similarity is clear.

5.2 The Business Cycle

5.2.1 THE LANGUAGE OF BUSINESS CYCLES

A careful look at Figure 5.1 shows that the ups and downs of the four series are closely

related. When the data are detrended (Figure 5.5), the pattern is even more clear. This is

not mere chance. The cyclical patterns of a large number of economic time series are

closely related. The tendency of many measures of economic activity to move in concert

suggests that there are common driving forces and that we can think, not just about the

trends and cycles of the individual measures, but of a business cycle. A reasonable

definition runs:

The BUSINESS CYCLE is the alternation in the state of the economy of a roughly

consistent periodicity and with rough coherence between different measures of the

economy.1

1 Occasionally, one still hears a older name of the business cycle: the trade cycle.

-

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis

Figure 5.4Real GDP: Trend and Cycle, 1970-1980

2500

3000

3500

4000

4500

5000

1970:1 1972:1 1974:1 1976:1 1978:1 1980:1

B

i

l

l

i

o

n

s

1

9

9

2

C

o

n

s

t

a

n

t

D

o

l

l

a

r

s

D

e

v

i

a

t

i

o

n

f

r

o

m

T

r

e

n

d

(

p

e

r

c

e

n

t

)

5

0

-5

Real GDP(left axis)

Trend

Detrended real GDP(right axis)

Trend is a 25-quarter centered moving average.

-

Source: Personal income, Bureau of Economic Analysis; industrial production, Federal Reserve; employment, Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Figure 5.5Selected Detrended Time Series

-20

-15

-10

-5

0

5

10

1959 1961 1963 1965 1967 1969 1971 1973 1975 1977 1979 1981 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001

p

e

r

c

e

n

t

-4

-2

0

2

4

6

8

10

p

e

r

c

e

n

t

Industrial Production(left axis)

Personal Income less transfers (right axis) Employment (right axis)

-

Applied Intermediate Macroeconomics Draft 2, 24 March 2005 Chapter 5 Trends and Cycles Word Count: 6210 2004 Kevin D. Hoover, All Rights Reserved AWL Page Equivalent 11

4

Rough coherence in this definition reflects the tendency of different economic

time series to move up or down in closely related patterns. Saying that the economywide

ups and downs are roughly consistent acknowledges the fact that, even though they are

not evenly spaced, the pattern of ups and downs does not appear to be completely

random: over the past 150 years, the average business cycle lasted four to five years; the

shortest, less than two years; the longest, ten years.

As with cycles in particular times series, business cycles are identified by their

peaks and troughs (see Figure 5.6). A specialized language has developed to describe

business cycles. Key terms include:

RECESSION (synonyms: slump, contraction): the period between the cyclical

peak and the cyclical trough, when economic activity is falling.

EXPANSION (synonyms: boom, recovery): the period between the cyclical

trough and cyclical peak, when economic activity is rising. Recovery is

sometimes used in the more limited sense of the period between the trough and

when the economy regains either (1) the level of activity experienced at the

previous peak or (2) the level it would have experienced had it remained on trend

(see Figure 5.6).

Depression: a particularly severe recession. Originally, depression was a

synonym indeed, a euphemism for a recession. Unfortunately, it became

associated with the largest slump in U.S. and world economic history: the Great

Depression of 1929-33, in which real GDP fell 27 percent and the unemployment

rate rose from just over 3 percent to just under 25 percent from the peak to the

-

Figure 5.6A Stylized Economic Time Series

Time

E

c

o

n

o

m

i

c

A

c

t

i

v

i

t

y

Peak

Peak

Peak

Trough

Trough

Trough

Recovery: Definition 2

Recovery: Definition 1

The period from peak to trough is a recession (also known as a slump or contraction). The period from trough to peak is known as an expansion (also known as a boom or recovery). Recovery is sometimes used to indicate only a portion of the upswing, either: 1. the period from trough to the level of the previous peak; or 2. the period from trough to the level of the trend. A ( complete) cycle is the period between a trough and the subsequent trough or a peak and the subsequent peak.

Complete Cycle

Complete Cycle

Trend

-

Applied Intermediate Macroeconomics Draft 2, 24 March 2005 Chapter 5 Trends and Cycles Word Count: 6210 2004 Kevin D. Hoover, All Rights Reserved AWL Page Equivalent 11

5

trough.2 Depression is now largely reserved for a recession that is particularly

severe in both scale and duration. Several of the contractions of the 19th century

are consider depressions, but the Great Depression is the only example of the 20th

century.

Growth recession: a period of slower than trend growth, usually lasting a year

or more. During a growth recession, output continues to rise, but at so slow a rate

that other aspects of the economy particularly, employment may stagnate or

fall. A growth recession, may be a harbinger of a proper recession.

(Complete) cycle: the period between a peak and the following peak or between

a trough and the following trough.

5.2.2 DATING THE BUSINESS CYCLE

The problem of dating business cycles is really just a matter of determining when the

economy reaches its peaks and its troughs. With so ambiguous a notion as the state of

the economy, there is no unique way to identify the business cycle.

A common rule of thumb defines a recession as two consecutive quarters of

negative growth in real GDP. The peak would then be marked at the quarter immediately

before GDP begins to fall, and the trough at the quarter immediately before it begins to

grow again.

2 While technically the trough of the Great Depression was reached in March 1933, many economic

historians regard the entire decade of the 1930s as depressed with recovery not secure until the United

States entered World War II at the end of 1941.

-

Applied Intermediate Macroeconomics Draft 2, 24 March 2005 Chapter 5 Trends and Cycles Word Count: 6210 2004 Kevin D. Hoover, All Rights Reserved AWL Page Equivalent 11

6

Although it has no official status, the National Bureau of Economic Research

(NBER), a private, non-profit organization, is widely regarded in the United States as the

arbiter of the beginnings and ends of recessions. The NBER explicitly rejects the two-

quarter rule. According to the NBER, a recession is

a recurring period of decline in total output, income, employment, and trade,

usually lasting from six months to a year, and marked by widespread contractions

in many sectors of the economy.3

Declining real GDP is, of course, typical of recessions, but the NBER Business-Cycle

Dating Committee regards it as an inadequate measure, because it is too narrow in its

scope and calculated only quarterly. The NBER casts its net wider and looks closely at

monthly, as well as quarterly, data. There is no formal rule. The NBERs judgment is

based on its overall impressions of the movements of many series. The complete set of

NBER business-cycle dates is given in Table 5.1.

The data that the NBER uses are often published only with a substantial delay,

and the committee usually must wait to see whether a change in direction is reversed or

confirmed by data of the next month or two. As a result, the dates of the peaks and

troughs are not typically announced until six months to a year after they occur. A

recession is usually nearly over before its onset is declared. An expansion is usually well

underway before the end of the recession is known to the public.

3 Quoted from the NBER web site (http://www.nber.org/cycles.html).

-

Table 5.1 NBER Business Cycle Dates

Business-cycle Reference Dates Duration in Months Trough Peak Contraction Expansion Cycle

(peak to trough)

(trough to peak)

trough from previous trough

peak from previous peak

December 1854 June 1857 -- 30 -- -- December 1858 October 1860 18 22 48 40 June 1861 April 1865 8 46 30 54 December 1867 June 1869 32 18 78 50 December 1870 October 1873 18 34 36 52 March 1879 March 1882 65 36 99 101 May 1885 March 1887 38 22 74 60 April 1888 July 1890 13 27 35 40 May 1891 January 1893 10 20 37 30 June 1894 December 1895 17 18 37 35 June 1897 June 1899 18 24 36 42 December 1900 September 1902 18 21 42 39 August 1904 May 1907 23 33 44 56 June 1908 January 1910 13 19 46 32 January 1912 January 1913 24 12 43 36 December 1914 August 1918 23 44 35 67 March 1919 January 1920 7 10 51 17 July 1921 May 1923 18 22 28 40 July 1924 October 1926 14 27 36 41 November 1927 August 1929 13 21 40 34 March 1933 May 1937 43 50 64 93 June 1938 February 1945 13 80 63 93 October 1945 November 1948 8 37 88 45 October 1949 July 1953 11 45 48 56 May 1954 August 1957 10 39 55 49 April 1958 April 1960 8 24 47 32 February 1961 December 1969 10 106 34 116 November 1970 November 1973 11 36 117 47 March 1975 January 1980 16 58 52 74 July 1980 July 1981 6 12 64 18 November 1982 July 1990 16 92 28 108 March 1991 March 2001 8 120 100 128 November 2001 8 -- 128 -- Average, all cycles:

1854-2001 (32 cycles) 17 38 55 5611854-1919 (16 cycles) 22 27 48 4921919-1945 (6 cycles) 18 35 53 53 1945-2001 (10 cycles) 10 57 67 67

continued next page

-

Average, peacetime cycles: 1854-2001 (27 cycles) 18 33 51 523 1854-1919 (14 cycles) 22 24 46 474 1919-1945 (5 cycles) 20 26 46 45 1945-2001 (7 cycles) 10 52 63 63 Notes: 131 cycles. 215 cycles. 326 cycles. 413 cycles. Figures printed in bold italic are the wartime expansions (Civil War, World Wars I and II, Korean War, and Vietnam War); the postwar contractions, and the full cycles that include the wartime expansions. Source: U.S. Department of Commerce, Survey of Current Business, October 1994, Table C-51.

-

Applied Intermediate Macroeconomics Draft 2, 24 March 2005 Chapter 5 Trends and Cycles Word Count: 6210 2004 Kevin D. Hoover, All Rights Reserved AWL Page Equivalent 11

7

In the 1992 presidential campaign, the delay in announcing the end of the

recession allowed Bill Clinton to claim (with some plausibility) that the economy was in

one of the longest recessions of the postwar period which, of course, he blamed on the

first President Bush. His catch phrase was, Its the economy, stupid! In fact, the

recession of 1990-91 was the second shortest in the postwar period, having lasted only

eight months, and had ended in March 1991 twenty months before the election. In

fairness to Clinton and the voters who agreed with his view of the economy, the

unemployment rate did not begin to fall until June 1992 (three months after the trough)

and did not reach its level at the cyclical peak (6.8 percent) until August 1993 more

than two years after the recovery had begun. This is not unusual; the peak in the

unemployment rate typically lags the cyclical trough. As we saw in Chapter 3, section

3.6.2, the NBER did not announce that the economy had reached its cyclical trough in

November 2001 until March 2003. And the Democrats again (and again with some

plausibility) blamed a President Bush for an economy effectively in recession in the run-

up to the 2004 election.

5.2.3 THE TYPICAL BUSINESS CYCLE

How well do the NBER business-cycle dates capture the cyclical fluctuations in the U.S.

economy? This is largely a question of how well they cohere with the movements of

time series that can be taken to be good reflections of the general state of the economy.

Economists have studied thousands of economic time series and classified their cyclical

behavior. To try to give some feeling for the business cycle as a whole, the U.S.

Department of Commerce created indices of ECONOMIC INDICATORS, similar to price

-

Table 5.2 Component Series of the Indices of Business-Cycle Indicators

Index of Leading

Indicators Index of Coincident

Indicators Index of Lagging

Indicators 1. Average weekly hours, manufacturing

1. Employees on nonagricultural payrolls

1. Average duration of unemployment *

2. Average weekly initial claims for unemployment insurance*

2. Personal income less transfer payments

2. Inventories to sales ratio, manufacturing and trade

3. Manufacturers' new orders, consumer goods and materials

3. Industrial production 3. Change in labor cost per unit of output, manufacturing%

4. Vendor performance, slower deliveries diffusion index

4. Manufacturing and trade sales

4. Average bank prime rate%

5. Manufacturers' new orders, nondefense capital goods

5. Commercial and industrial loans

6. Building permits, new private housing units

6. Consumer installment credit to personal income ratio

7. Stock prices, 500 common stocks

7. Change in consumer price index for services%

8. Money supply, M2 9. Interest rate spread, 10-year Treasury bonds rate minus federal funds rate%

10. Index of consumer expectations

Source: Conference Board *inverted series, a negative change in this component makes a positive contribution. % in percent change form, contributions based on arithmetic changes.

-

Applied Intermediate Macroeconomics Draft 2, 24 March 2005 Chapter 5 Trends and Cycles Word Count: 6210 2004 Kevin D. Hoover, All Rights Reserved AWL Page Equivalent 11

8

indices. (Since 1995, the indices have been compiled by the Conference Board, a non-

profit business organization.) Each of the three indices (leading, coincident, and lagging

indicators of the business cycle) is a weighted average of several monthly time series and

is expressed as an index number based such that the average value for 1992 equals 100.

Table 5.2 shows the component series for each index. At this stage, we are concerned

only with the index of coincident indicators a group of time series whose peaks and

troughs should correspond to the peaks and troughs of the business cycle. (We will

consider leading and lagging indicators in section 5.3 below.) Figure 5.7 shows that the

peaks and troughs of the (detrended) coincident indicators closely match the NBER cycle

dates.

How can we characterize the typical business cycle? Figure 5.8 provides one

answer with another view of the relationship between the coincident indicators and the

NBER cycle dates. The figure is centered on the business cycle peak, marked 0. The

index of coincident indicators is rescaled to take the value of 100 at the business cycle

peak (see the Guide, section G.8.1). The figure shows twelve months before the peak (1

to 12) and thirty-six months after (+1 to +36). The vertical lines indicate the NBER

peaks and troughs. Heavy lines show average values for the seven business cycles

between 1960 and 2004, while the lighter lines show the values for the 1990-91

recession. (As noted in Chapter 3, the recession of 2001 is somewhat unusual. Students

are asked to examine it in problem 5.13.) The average index peaks exactly at the NBER

peak. At +16 months, its trough is about five months past the average trough for the

seven business cycles (+11). This shows that, when recessions are longer than average,

-

Source: Index of coincident indicators, The Conference Board; recession dates, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Figure 5.7Coincident Indicators and the Business Cycle

-6

-4

-2

0

2

4

6

1962 1964 1966 1968 1970 1972 1974 1976 1978 1980 1982 1984 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996

D

e

v

i

a

t

i

o

n

s

f

r

o

m

T

r

e

n

d

(

p

e

r

c

e

n

t

)

Shaded areas are NBER recessions.

The index of coincident indicators conforms well, though not perfectly, with the NBER business cycle

-

Sources: index of coincident indicators, The Conference Board; business-cycle dates, National Bureau of Economic Research

Figure 5.8Coincident Indicators and the Business Cycle

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

-12 -10 -8 -6 -4 -2 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 28 30 32 34 36Months from Peak

I

n

d

e

x

(

v

a

l

u

e

a

t

p

e

a

k

=

1

0

0

)

Average coincident indicators (last seven business cycles)

Coincident indicators(1990-91 business cycle)

Average trough (last seven business cycles)

Peak

Trough(1990-91

business cycle)

-

Applied Intermediate Macroeconomics Draft 2, 24 March 2005 Chapter 5 Trends and Cycles Word Count: 6210 2004 Kevin D. Hoover, All Rights Reserved AWL Page Equivalent 11

9

they are also deeper than average drawing down the average level of the coincident

indicators. In 1990-91 the coincident indicators track the NBER cycle dates exactly.

Figures 5.9 (a) (c) examine the typical cyclical behavior of the three time series

already displayed in Figure 5.1: personal income (less transfers), industrial production,

and employment. These are three of the four components of the index of coincident

economic indicators. The pattern of industrial production most strongly resembles that of

the index of coincident indicators. The average data peaks at the NBER business cycle

peak, but the trough is some five months behind the NBER trough. And the data for

1990-91 are nearly perfectly coincident. The pattern for employment is similar for the

average; but the major losses in employment tend to come early in the recession, so that

employment falls only slowly to its trough. The pattern of employment in the 1990-91

recession is different: it peaks before the NBER peak flattens out near the NBER trough,

and begins a steady recovery only eight to ten months after the NBER trough. It was this

anomalous pattern that supported the Democrats claim that the economy was still in

recession at the time of the 1992 election. The pattern of personal income less transfers

is almost perfectly coincident in 1990-91; yet, on average, it appears to peak before the

NBER peak and to rise very slowly from the NBER trough. One striking feature is that

personal incomes are far less variable over the average recession than are industrial

production or employment.

Table 5.1 and Figures 5.7-5.9 give us a good picture of the history of recent U.S.

business cycles. At least two characteristics are worth noting. First, the average

recession in the post-World War II period lasted eleven months, while the average

expansion lasted fifty months. Far from acting like the simple, symmetrical sine waves in

-

Sources: employment, Bureau of Labor Statistics; business-cycle dates, National Bureau of Economic Research

Figure 5.9 (a)Industrial Production and the Business Cycle

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

-12 -10 -8 -6 -4 -2 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 28 30 32 34 36Months from Peak

I

n

d

e

x

(

v

a

l

u

e

a

t

p

e

a

k

=

1

0

0

)

Average industrial production (last seven business cycles)

Industrial production (1990-91 business cycle)

Average trough (last seven business cycles)

Peak

Trough(1990-91

business cycle)

-

Sources: employment, Bureau of Labor Statistics; business-cycle dates, National Bureau of Economic Research

Figure 5.9 (b)Employment and the Business Cycle

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

-12 -10 -8 -6 -4 -2 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 28 30 32 34 36Months from Peak

I

n

d

e

x

(

v

a

l

u

e

a

t

p

e

a

k

=

1

0

0

)

Average employment (last seven business cycles)

Employment(1990-91 business cycle)

Average trough (last seven business cycles)

Peak

Trough(1990-91

business cycle)

-

Sources: employment, Bureau of Labor Statistics; business-cycle dates, National Bureau of Economic Research

Figure 5.9 (c)Personal Income (less transfers) and the Business Cycle

96

98

100

102

104

106

-12 -10 -8 -6 -4 -2 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 28 30 32 34 36Months from Peak

I

n

d

e

x

(

v

a

l

u

e

a

t

p

e

a

k

=

1

0

0

)

Average personal income (last seven business cycles)

Personal income (1990-91 business cycle)

Average trough (last seven business cycles)

Peak

Trough(1990-91

business cycle)

-

Applied Intermediate Macroeconomics Draft 2, 24 March 2005 Chapter 5 Trends and Cycles Word Count: 6210 2004 Kevin D. Hoover, All Rights Reserved AWL Page Equivalent 11

10

the stylized graphs of Figures 5.2, 5.3, and 5.4, business cycles are asymmetrical. The

process of economic growth over the last fifty years can be characterized as a pattern of

five steps forward and one step back.

Second, the expansion that began in December 1982 is the third longest on record,

the expansion that began in April 1991 is the longest, and the recession that separated

them is tied with the 2001 recession as the second shortest. Consequently, the typical

college student in 2005 has lived through the longest sustained period of growth in U.S.

economy history and has virtually no personal experience with highly unfavorable

economic conditions.

5.3 The Business Cycle and the Economy

5.3.1 WHAT CAUSES THE BUSINESS CYCLE?

The causes and proper analysis of the business cycle have been hotly debated by

economists since it was first identified as a regular phenomenon in the 19th century.

Economists have found it useful to distinguish two aspects of the cycle: IMPULSE and

PROPAGATION MECHANISMS. A child on a swing follows a cyclical pattern. A mother

who gives the child an occasional push provides the impulse. In this case, the cycle is

caused by the propagation mechanism that is, by gravity and the construction of the

swing that limits its motion, guaranteeing that an outward motion reaches a peak, is

reversed and reaches a trough on the backswing. Theories of the business cycle differ in

whether they place the main emphasis on the impulse or the propagation mechanism.

One class of theories argues that the propagation mechanisms in the economy are

like the swing intrinsically cyclical. Many of the cycles in nature, such as the tides or

-

Applied Intermediate Macroeconomics Draft 2, 24 March 2005 Chapter 5 Trends and Cycles Word Count: 6210 2004 Kevin D. Hoover, All Rights Reserved AWL Page Equivalent 11

11

the paths of the moon and the planets, are intrinsic. Even a complex cycle, such as the

vibrations of a guitar string, which needs impulses from time-to-time to continuing

sounding, is mainly governed by its propagation mechanism. If the economy has an

intrinsic cycle it is necessarily a highly complex one more complex than the guitar

string or the tides.

A second class of theories holds that the cycles in the economy are the result

primarily of cycles in the impulse mechanisms themselves. In the 19th century, William

Stanley Jevons (1835-1882) argued that variations in solar activity, correlated with

sunspots, caused variations in agricultural harvests and, ultimately, caused the business

cycle. Although Jevons theory was never widely accepted, some economists today argue

that exogenous cycles in technology cause the business cycle. Others believe that

recurring recessions are induced by the actions of policymakers. If the Federal Reserve

would just leave the economy to its own devices, and not raise interest rates from time to

time, advocates of this view believe that the economy would suffer few recessions.

A third class of theories argues that business cycles are ultimately irregular. Yes,

there are ups and downs, but the patterns that we see in these ups and downs are illusory.

Imagine that GDP tends to grow on average 2 percent per year, but that each year

completely random good or bad events events with no cycle occur. Statisticians

describe such a pattern as a random walk with a drift. (The drift is the 2 percent trend

growth.) The pattern is called a random walk because it resembles the path that a

drunken man might take after leaving the tavern: since each step is just as likely to go in

one direction as another, the best average prediction of where the man will be after his

next step is where he is now standing. Figure 5.10 shows a random walk with a drift that

-

Figure 5.10 A Random Walk with a Drift

3000

4000

5000

6000

7000

8000

9000

1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 23 25 27 29 31 33 35 37 39 41 43 45 47 49 51 53 55 57 59 61

Years

G

D

P

With random walk with a drift, today's value is yesterday's value plus a percentage growth term (the drift) plus a random term as equally likely to move up as down (the random walk). Such a series may appear to have a cycle (this one looks remarkably like the graph of real GDP), but there is no genuine regularity behind its fluctuations.

-

Applied Intermediate Macroeconomics Draft 2, 24 March 2005 Chapter 5 Trends and Cycles Word Count: 6210 2004 Kevin D. Hoover, All Rights Reserved AWL Page Equivalent 11

12

looks strikingly similar to graphs of real GDP (e.g., Figure 2.10). The apparent cyclical

patterns in the figure are purely accidental and do not describe a genuine phenomenon in

need of a theoretical explanation.

The jury is still out on which type of account of business cycles describes the

actual economy: Are its ups and downs governed by laws as regular as (if more complex

than) those of physics and biology? Or are the ups and downs really just a reflection of

the way in which the economy processes random influences? Or is there room for some

combination of these mechanisms (for example, random influences superimposed on

underlying regular patterns)? We cannot hope to give definitive answers in an

intermediate textbook. They are the agenda for cutting-edge economic research.

If the random-walk explanation is correct, then the cyclical behavior of the

economic is an illusion. Economists who do not want to imply the strong notion of

regularity that often attends the word cycle sometimes use economic fluctuations as a

more neutral description than business cycle. But there is something lifeless about this

term; so, we shall continue to use business cycle throughout this book.

5.3.2 THE CLASSIFICATION OF ECONOMIC INDICATORS

Our definition of the business cycle had two parts: (1) alternation in the state of the

economy; and (2) coherence among different measures of the economy. While

economists continue to debate the ultimate sources of alternation, and even whether the

patterns are truly recurring ones, they understand much better the nature of the coherence

among different measures. Sometimes the connections are obvious. It takes workers to

produce goods; therefore, it is not surprising that employment and industrial production

-

Applied Intermediate Macroeconomics Draft 2, 24 March 2005 Chapter 5 Trends and Cycles Word Count: 6210 2004 Kevin D. Hoover, All Rights Reserved AWL Page Equivalent 11

13

follow similar patterns over time. It takes income to support expenditure; therefore, it is

not surprising that consumption follows a similar pattern to income. Other connections

are less obvious, and much of economic theory (and much of this textbook) aim to make

them more clear. As a starting place, it is useful to have a good vocabulary to describe

the relationships among different time series.

Economic indicators can be classified according to how they behave compared to

the business cycle. We have already used the index of coincident indicators as a measure

of the cycle. An indicator is said to be coincident if it reaches its peak at or near the peak

of the business cycle and reaches its trough at our near the trough of the business cycle.

Economic indicators are classified by whether or not they generally move in the same

direction as the main positive measures of the business cycle, such as GDP, industrial

production, or employment. Indicators can be

procyclical: they move in roughly the same direction as the business cycle (for

example, retail sales are procyclical);

countercyclical: they move in roughly the opposite direction as the business

cycle (for example, the unemployment rate is countercyclical); or

acyclical: they have no regular relationship to the cycle (for example, agricultural

production and population are acyclical).4

4 Even though it has its own ups and downs, agricultural production follows the seasons and year-to-year

fluctuations in the weather, rather than fluctuations in the economy as a whole. Agriculture now constitutes

only 2.5 percent of the economy by total employment. In the past, when its share in the economy was

larger, it would have been more closely related to the business cycle.

-

Applied Intermediate Macroeconomics Draft 2, 24 March 2005 Chapter 5 Trends and Cycles Word Count: 6210 2004 Kevin D. Hoover, All Rights Reserved AWL Page Equivalent 11

14

Indicators are also classified by their phase relationship to the business cycle

that is, according to whether their extreme points occur before, after, or at the same time

as the extreme points of the business cycle. Some possibilities for procyclical time series

are illustrated in Figure 5.11:

A leading indicator reaches its peak and trough before the corresponding peak or

trough of the business cycle;

A lagging indicator reaches its peak and trough after the corresponding peak or

trough of the business cycle;

A mixed indicator follows a regular pattern different from either the leading or

lagging indicator. The third series in Figure 5.11 shows a mixed indicator that

leads the business-cycle peak at the peak, but is coincident at the business-cycle

trough. There are many possible mixed patterns.

Countercyclical indicators can also be leading, lagging, or mixed indicators. The average

duration of unemployment, for example, is a countercyclical, lagging indicator of the

business cycle.

The U.S. Department of Commerce developed, and the Conference Board now

maintains and publishes monthly, indices of leading and lagging economic indicators.

Table 5.2 shows the component series of these indices, as well as those of the index of

leading economic indicators.

5.3.3 IS THE BUSINESS CYCLE PREDICTABLE?

The fact that a number of time series are consistent leading economic indicators suggests

that it may be possible, to some degree, to predict the course of the business cycle.

-

Figure 5.11Classification of Economic Indicators

Time

V

a

l

u

e

o

f

I

n

d

i

c

a

t

o

r

Leading Indicators

Lagging Indicators

Mixed Indicators: leading at peak; coincident at trough

Acyclic Indicators

Shaded areas indicate recessions.

-

Applied Intermediate Macroeconomics Draft 2, 24 March 2005 Chapter 5 Trends and Cycles Word Count: 6210 2004 Kevin D. Hoover, All Rights Reserved AWL Page Equivalent 11

15

Figure 5.12 shows the three indices of economic indicators (detrended). Notice first, the

broad similarity of the fluctuations. All three series are procyclical, and they show the

rough coherence that characterizes the business cycle.5 Looking more closely, we see the

expected pattern (especially clear at the peaks and troughs): the leading indicators move

ahead of the coincident indicators, which, in their turn, move ahead of the lagging

indicators.

How well can the relationships among the indicators be exploited to forecast the

path of the business cycle? There are two questions: First, how long on average is the

lead between the leading and coincident indicators? Second, how strongly related are the

two indices? The second question can be answered by calculating the coefficient of

correlation between the two indices. (Box 5.2 describes the measurement of correlation.)

The correlation between the leading and coincident indicators is 0.44, which is a

moderate, positive correlation. But we should not really expect a strong correlation

between the leading indicators today and coincident indicators today. We know that the

leading indicators move ahead of the coincident indicators. We can instead calculate the

correlation between the coincident indicators in each period and the leading indicators

one or more months earlier. The correlation between the index of coincident indicators

and the index of leading indicators one month earlier is 0.54 a little bit stronger.

Table 5.3 presents the results of such calculations for leads and lags of twelve

months. The first column shows the correlations between the coincident indicators and

5 One of the component series of the index of leading indicators and one of the lagging indicators are

actually countercyclical, but they are multiplied by 1 before being entered into the indices, so that all

components tend to move in the same direction relative to the business cycle.

-

Applied Intermediate Macroeconomics Draft 2, 2 April 2005 Chapter 5 Trends and Cycles, BOX 5.2 Word Count: 492 2004 Kevin D. Hoover, All Rights Reserved

Box 5.2. Working with Economic Data: Correlation

Data that move together systematically are said to be correlated. The left-hand side of

Figure B5.2, panel A, shows two perfectly positively correlated series plotted against

time. They have different means and different amplitudes, but a 20 percent rise in X is

matched by a 20 percent rise in Y and a 3 percent fall by a 3 percent fall and so on. The

correlation coefficient (r) measures degree of conformity between the series (see the

Guide, section G.13, on the details of its calculation). A correlation coefficient of r = +1

indicates perfect correlation. Look at the data another way. The right-hand side of panel

A, which shows the same two series plotted against each other rather than against time,

illustrates the hallmark of perfect correlation: the points lie on a straight line.

See the Guide, section G.12, for more on detrending time series.

The correlation coefficient takes the value r = 1, when series are perfectly

negatively correlated. Then each movement of X would be matched by a proportional

movement of Y in the opposite direction. It takes the value r = 0, when there is no

relationship between the series. Besides these extreme points, values in the interval

0 < r < 1, indicate different degrees of conformity between fluctuations between series.

Panel B shows two highly, but imperfectly, correlated series (r = 0.9). For the most part

the series fluctuate together. Once in a while they move in opposite directions, and, when

they move together, it is not always with a constant proportion. The right-hand side of

Panel B shows that the scatterplot forms a cloud of points. The more oblong this cloud,

the closer it comes to a straight line, the higher the correlation.

Panel C illustrates a case of zero correlation (r = 0). Here there is no common

pattern to the movements of the time series. The cloud of points are scattered in a diffuse

-

Applied Intermediate Macroeconomics Draft 2, 2 April 2005 Chapter 5 Trends and Cycles, BOX 5.2 Word Count: 492 2004 Kevin D. Hoover, All Rights Reserved

oval rather than tightly grouped along a line. Panel D shows a moderate negative

correlation (r = 0.5). The points in the scatterplot form an obviously downward tilting

cloud neither as diffuse as panel C nor as tight as panel B.

Although the illustrations are all time series, the correlation coefficient can also

measure the conformity among cross-sectional data. We can equally calculate the

correlation between GDP growth rates and inflation rates for the United States since the

1970s or for the G-7 countries in 2004.

Like other summary statistics, the coefficient of correlation is interpretable only

for stationary data. The Guide, section G.14.1, discusses nonsense correlation, which

arise when data do not have constant means. Two trending series will generally have a

high correlation coefficient. Yet, there may or may not be a genuine relationship between

them. It is important to detrend nonstationary time series before calculating the

coefficient of correlation (see Box 5.1 and the Guide, section G.13).

-

Figure B5.2 Correlations between Time Series

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

3.5

4

4.5

5

1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19Time

X

Y

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19Time

X

Y

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

3.5

4

1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 1Time

X

Y

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

.5

4

4.5

5

0 0.5 1 1.5

X

Y

Panel A. r = 1.0

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

0 0.5

X

1

Y

Box 5.2

Panel B. r = 0.9 3.5

4 37 19

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

0 0.5 1 1

X

.5

Y

Panel C. r = 0.0 Continued next page

3

-

Figure B5.2 Correlations between Time Series

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

3.5

4

4.5

5

1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19Time

X

Y

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

3.5

4

4.5

5

3 3.5 4 4.5 5

X

Y

Box 5.2 4

Panel D. r = 0.5

-

Source: The Conference Board

Figure 5.12Indices of Business Cycle Indicators

-8

-6

-4

-2

0

2

4

6

8

1962:01 1967:01 1972:01 1977:01 1982:01 1987:01 1992:01

D

e

v

i

a

t

i

o

n

s

f

r

o

m

T

r

e

n

d

(

p

e

r

c

e

n

t

)

Index of Leading IndicatorsIndex of Lagging Indicators

Index of Coincident IndicatorsDetrended using a 25-quarter centered moving average.

T he three indices show closely related movements. As seen most easily at the peaks and troughs ,the leading economic indicators anticipate the movements of the coincident indicators, which in turn anticpate the movements of the lagging indicators.

-

Table 5.3 Correlations Among Business-Cycle

Indicators

Number of months lead

Leading indicator

Lagging indicator

-12 -0.41 0.77 -11 -0.37 0.79 -10 -0.32 0.81 -9 -0.27 0.82 -8 -0.20 0.82 -7 -0.14 0.80 -6 -0.06 0.78 -5 0.01 0.75 -4 0.09 0.72 -3 0.17 0.66 -2 0.26 0.60 -1 0.35 0.52 0 0.44 0.44 +1 0.53 0.33 +2 0.61 0.23 +3 0.69 0.13 +4 0.75 0.03 +5 0.80 -0.06 +6 0.84 -0.14 +7 0.86 -0.22 +8 0.88 -0.30 +9 0.89 -0.37 +10 0.89 -0.44 +11 0.88 -0.50 +12 0.86 -0.56

Source: Conference Board and authors calculations Entries represent the correlation coefficient between the current value of the indices of leading and lagging indicators and value of the index of coincident indicators 1 to 12 months earlier and 1 to 12 months later.

-

Applied Intermediate Macroeconomics Draft 2, 24 March 2005 Chapter 5 Trends and Cycles Word Count: 6210 2004 Kevin D. Hoover, All Rights Reserved AWL Page Equivalent 11

16

the leading economic indicators. The row labeled 0 is the correlation when both indices

are measured in the same month. It is, as we already observed, 0.44. The row labeled +1

indicates the leading indicators in one month and the coincident indicators one month

later. It measures how well the leading indicators predict the later coincident indicators

and, therefore, the business cycle. Again, we already have seen that the value is 0.54.

Subsequent rows (labeled +2 to +12) show the correlation between the leading indicators

and the coincident indicators two, three, and up to twelve months ahead, as well as one to

twelve months behind (1 to 12). on. The second column shows a similar set of

correlations between the lagging indicators and the coincident indicators.

The highest correlation between the coincident and leading indicators is 0.89 at

+9 and +10 months lead (that is, roughly three quarters ahead). Such a strong correlation

suggests that the leading indicators are a good, though imperfect, predictor of the future

behavior of the business cycle. The point is reinforced visually in Figure 5.13, which is

similar to Figure 5.12, except that the index of leading indicators has been shifted

forward by nine months (that is, the value for January is plotted at the following

September and so forth). Once shifted, the leading and coincident indicators line up

extremely well.

News reports frequently say that the index of leading economic indicators is the

governments main forecasting tool and that the index signals downturns in the

economy six to nine months ahead. The first claim is hyperbole. Most government

forecasts are, in fact, generated from macroeconomic computer-models of the economy

in which tens, or even hundreds, of equations represent different aspects of the economy,

and the index of leading economic indicators plays no part whatsoever. Also, as we

-

Source: The Conference Board

Figure 5.13How well do the leading indicators predict the business cycle?

-8

-6

-4

-2

0

2

4

6

1962:10 1967:10 1972:10 1977:10 1982:10 1987:10 1992:10

D

e

v

i

a

t

i

o

n

s

f

r

o

m

T

r

e

n

d

(

p

e

r

c

e

n

t

)

Index of Leading Indicators

Index of Coincident Indicators

Index of Leading Indicators shifted forward 9 months

Shifting the leading economic indicators forward by nine months aligns them closely with the coincident indicators, giving some evidence of their ability to signal business cycle fluctuations roughly three quarters ahead.

-

Applied Intermediate Macroeconomics Draft 2, 24 March 2005 Chapter 5 Trends and Cycles Word Count: 6210 2004 Kevin D. Hoover, All Rights Reserved AWL Page Equivalent 11

17

noted earlier, the government has given over the maintenance of the business cycle

indicators to the private sector.

There is, nevertheless, good reason to believe that the index of leading indicators

does have some predictive power for the business cycle. Notice that in Table 5.2 the

correlation between the leading and coincident indicators is above 0.8 for each of the

months between +6 and +12. This supports the idea that the leading indicators help to

forecast recessions. A popular rule of thumb states that two months of consecutive

declines in the leading indicators signals an imminent recession. This rule often works,

but it also works too often: most recessions are predicted accurately, but sometimes a

recession is predicted and none occurs. Others have suggested three months of decline,

rather than two, to give more accurate predictions. In that case, however, there is

necessarily less lead time between the signal and the onset of the recession.

One reason that the leading economic indicators are important is that, as we

discussed in section 5.2.2, as well as in Chapter 3, section 3.6.2, there is often

considerable delay in getting relevant information about coincident indicators. One of

the roles of the index of lagging economic indicators is to buttress the evidence that the

economy actually entered or left a recession and to help to resolve the uncertainty that

clouds all judgments about the state of the economy. Table 5.3 shows that the correlation

between the lagging and the coincident indicators is highest at 0.82 with a lag of 8 to 9

months (roughly three quarters behind).

The consistent patterns of the leading, lagging, and coincident indicators

demonstrate that there are facts about the business cycle that economists need to explain.

They give some clues about the course of the business cycle. But they do not, in

-

Applied Intermediate Macroeconomics Draft 2, 24 March 2005 Chapter 5 Trends and Cycles Word Count: 6210 2004 Kevin D. Hoover, All Rights Reserved AWL Page Equivalent 11

18

themselves, explain the why the business cycle behaves as it does. In later chapters, we

will try to understand the mechanisms that account for these patterns.

Summary

1. Many economic time series are dominated by fluctuations around a dominant tendency

to grow. These may be decomposed into a trend, reflecting growth and a cycle

reflecting the fluctuations.

2. The high point of a cycle relative to trend is known as the peak; and the low point, the

trough. A complete cycle is measured peak to peak or trough to trough.

3. The business cycle is the tendency of the state of the economy (measured by a wide

variety of time series) to fluctuate in a roughly regular manner.

4. A complete business cycle includes a recession (the period from peak to trough) and an

expansion (the period from trough to peak).

5. Business cycles are dated according to their peaks and troughs. The relevant

information often arrives with a substantial delay.

6. The expansion phase of the typical post-World War II business cycle in the U.S. is

about five times as long as the recession phase (11 versus 50 months).

7. Economists remain divided over the causes of business cycles. Some point to cycles in

the extrinsic impulses to the economy. Others point to intrinsic economic behavior

that propagate cycles. Still others believe that the fluctuations are not true cycles, but

random movements that merely suggest a cycle.

8. Whether cycles are genuine or not in the sense of possessing a deep regularity,

economic behavior does explain common movements among economic time series.

-

Applied Intermediate Macroeconomics Draft 2, 24 March 2005 Chapter 5 Trends and Cycles Word Count: 6210 2004 Kevin D. Hoover, All Rights Reserved AWL Page Equivalent 11

19

Series can be classified as moving with the business cycle (procylical), against the

cycle (countercyclical), or unrelated to the cycle (acyclical). They may also

systematically lead, lag, or coincide with the business cycle, or have some more

complex relationship to it.

9. The existence of patterns in which some time series are leading indicators for the

business cycle implies that the cycle may itself be predicted. The index of leading

economic indicators tends to lead the business cycle by about nine months.

Key Concepts cycle cyclical peak cyclical trough business cycle expansion

recession economic indicators impulse mechanism propagation mechanism

Suggestions for Further Reading National Bureau of Economic Research, Business Cycle Dating Committee Web Site

(http://nber.org/cycles/main.html) contains useful articles about its procedures and announcements of particular peaks and troughs.

Norman Frumkin. Guide to Economic Indicators. Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, 1990. F.M. OHara, Jr. and F.M. OHara, III. Handbook of United States Economic Indicators, revised edition. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2000.

-

Applied Intermediate Macroeconomics Draft 2, 24 March 2005 Chapter 5 Trends and Cycles Word Count: 6210 2004 Kevin D. Hoover, All Rights Reserved AWL Page Equivalent 11

20

Problems Data for this exercise are available on the course website under the link for Chapter 5 (insert web link here). Before starting these exercises, the student should review the relevant portions of the Guide to Working with Economic Data: sections G.4, G.7, and G.13. Problem 5.1. In Problem 2.12 you were supposed to have identified the peaks and

troughs of the business cycle using the two-quarter rule. If you have not done this exercise already, do it now. Table 5.1 gives the NBER monthly dates in which peaks and troughs occurred. Convert these to the equivalent quarters and then construct a table that compares your results from Problem 2.12 to the NBER dates. Go the NBERs Business Cycle Dating Committees website (http://nber.org/cycles/main.html). Read the Frequently Asked Questions and other documents relating to their dating procedures. In light of the information provided by the NBER and your own understanding of the business cycle, explain how and why your dates differ from the official NBER dates.

Problem 5.2. (a) Using Table 5.1, construct your own table identifying by date and

duration in months the shortest and longest booms, slumps, and complete cycles (peak to peak and trough to trough) for the period from 1945 to the present. Also identify by date and duration the median boom, slump, and complete cycle. (b) Repeat the exercise in part (a) for the period before 1942. (c) Does the business cycle have noticeably different characteristics before and after the Second World War?

Problems 5.3 and 5.4 generate data to be used in Problems 5.5 and 5.6. Problem 5.3. Using quarterly real GDP data for the period since 1947, calculate the

percentage change in GDP for each recession (peak to trough), expansion (trough to peak), and complete cycles (peak to peak and trough to trough) and enter them as separate time series on a spreadsheet. For each series calculate the mean and median values.

Problem 5.4. Using monthly employment data for the period since 1947, calculate the

percentage change in employment for each recession (peak to trough), expansion (trough to peak), and complete cycles (peak to peak and trough to trough) and enter them as separate time series on a spreadsheet. For each series calculate the mean and median values.

Problem 5.5. Using the calculated in Problems 4.2, 4.4 and 4.5, describe the quantitative

and temporal characteristics of the typical post-World War II business cycle.

-

Applied Intermediate Macroeconomics Draft 2, 24 March 2005 Chapter 5 Trends and Cycles Word Count: 6210 2004 Kevin D. Hoover, All Rights Reserved AWL Page Equivalent 11

21

Problem 5.6. There are a number of competing theories of the business cycle. One suggests that the seeds of the slump are sown in the boom, so that the higher the peak, the lower subsequent trough. Another suggests that the economy is like a guitar string, the further it is plucked (the lower the trough), the more it rebounds (the higher the subsequent peak). Another holds that mild recessions are followed by strong recoveries. Yet another holds that adjacent recessions and expansions are essentially independent of each other. There are other possibilities. How could you state these three views in terms of correlations between the changes in real GDP and adjacent recessions and expansions? (Hint: it is easier to think clearly if the fall in GDP during a recession is measured by its absolute value.) Using the data you generated in Problem 5.3, test your hypotheses by calculating two correlations: 1. between expansions and the subsequent recession; and 2. between recessions and the subsequent expansion. Which of the four hypotheses (or which other pattern) do your calculations favor?

Problem 5.7. Instead of focusing on the size of changes as measured by GDP as in

Problem 5.6 consider the same set of hypotheses using the duration of the recessions and expansions. Using the data in Table 5.1 for post-World War II recessions, repeat the calculations of Problem 5.6. Which of the four hypotheses (or which other pattern) do your calculations favor? Compare these results for those using GDP.

Problem 5.8. Use data on real GDP to establish the dates of the peaks and troughs of the

Canadian business cycle. Explain your procedure. What is the typical Canadian business like measured by the size and durations of its recessions, expansions, and complete cycles? Do Canadian business cycles seem to be closely related to U.S. business cycles?

Problem 5.9. Use data on real GDP to establish the dates of the peaks and troughs of the

Japanese business cycle. Explain your procedure. What is the typical Japanese business like measured by the size and durations of its recessions, expansions, and complete cycles? Should we characterize Japan as having experienced a depression in the 1990s?

-

Applied Intermediate Macroeconomics Draft 2, 24 March 2005 Chapter 5 Trends and Cycles Word Count: 6210 2004 Kevin D. Hoover, All Rights Reserved AWL Page Equivalent 11

22

Problem 5.10. How good are the leading indicators as predictors of recessions? One rule (see section 5.3.3) states that if index of leading economic indicators turns down two months in succession, then a recession should be expected. Statisticians recognize two types of error. Type I error (false negative) occurs when a recession is not signaled, but one in fact follows. Type II error (false positive) occurs when a recession is signaled and none in fact follows. Using Table 5.1 and the time series for the index of leading economic indicators, identify all the times in which the 2-quarter rule signals a recession, then check to see whether the business cycle reaches a peak (i.e, a recession begins) within the subsequent year. Similarly, identify all the times in which a recession occurs, then check to see whether the leading indicators signaled a recession within the preceding year. Fill in the number of each case in the following table:

Recession Does Not Occur Occurs

Do NotSignal

Recession

Leave this cell blank.

Any case that does not fall into one of the other cells automatically belongs here.

Type I Error: enter the number of times a recession occurred without having been signaled

Leading Indicators

Signal

Recesssion

Type II Error: enter the number of times a recession was signaled but failed to occur

Success: enter the number of times a recession was signaled and occured

Repeat this exercise using a 3-quarter rule. How do the errors change? Which rule is

best? Why? Is the best rule useful as a predictor of recessions? Explain the reasons for your assessement.

-

Applied Intermediate Macroeconomics Draft 2, 24 March 2005 Chapter 5 Trends and Cycles Word Count: 6210 2004 Kevin D. Hoover, All Rights Reserved AWL Page Equivalent 11

23

Problem 5.11. Using whatever calculations and graphical analysis that you find helpful, examine the unemployment rate and identify its cyclicality; i.e., is it: procyclical, countercyclical, or acyclical? Is it a leading, lagging, or mixed indicator? (If mixed, give an accurate description of its properties.)

Problem 5.12. Calculate the time series for the annualized quarterly rate of real GDP

growth. Plot this series against the NBER business cycle dates. Compare your graph to Figure B5.1. Do these two graphs conform roughly to the stylized relationship between fluctuations in a level series and the rate of change series as shown in that figure and discussed in Box 5.1?

Problem 5.13. As observed in Chapter 3, section 3.6.2 (especially Figure 3.6), the 2001

recession appears not to have been a recession at all when judged by the revised data for real GDP. Using whatever data, calculations, and graphical analysis that you find helpful, do a wider range of data support the NBERs identification of a recession in that year?