by Jacqueline Jones - ETS · PDF fileEarly Literacy Assessment Systems: Essential Elements by...

Transcript of by Jacqueline Jones - ETS · PDF fileEarly Literacy Assessment Systems: Essential Elements by...

Early LiteracyAssessment Systems:Essential Elements

by Jacqueline Jones

POLICY INFORMATIONPERSPECTIVE

Research & Development

Policy InformationCenter

023990-88502 • Policy Info Perspective • from Marketing to Pubs 5.6.03 kaj • 2CE 5/14/03 kb • code/preflight 5/19/03 jdj

023990_Cover 5/30/03 10:10 AM Page 2

Additional copies of this report can beordered for $10.50 (prepaid) from:

Policy Information CenterMail Stop 04-REducational Testing ServiceRosedale RoadPrinceton, NJ 08541-0001(609) 734-5694e-mail: [email protected] can also be downloaded from:www.ets.org/research/pic

Copyright © 2003 by Educational Testing Service. All rights reserved. Educational Testing Service is anAffirmative Action/Equal Opportunity Employer. The modernized ETS logo is a registered trademark ofEducational Testing Service.

June 2003

IFC

023990-88502 • Policy Info Perspective • from Marketing to Pubs 5.6.03 kaj • 2CE 5/14/03 kb • code/preflight 5/19/03 jdj 023990-8

023990_Cover 5/30/03 10:10 AM Page 3

EARLY LITERACY ASSESSMENT SYSTEMS • 1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Preface . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

Acknowledgements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

Increased Awareness of the Importance of Early Development . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

The Achievement Gap at Kindergarten . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

Concern About the Effectiveness of Public Education . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

Issues in Literacy Instruction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

Issues in the Assessment of Young Children . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

Elements of Effective Early Literacy Assessment Systems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

Multiple Forms of Evidence of Early Literacy Development . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

The Role of Leadership . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Teacher Professional Development . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

An Effective Early Literacy Assessment System . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

Summary and Conclusions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

023990_PIP_TEXT_EarlyLit 5/30/03, 10:13 AM1

2 • EARLY LITERACY ASSESSMENT SYSTEMS

PREFACE

As part of the No Child Left Behind Act,increasing attention is being paid to early lit-eracy achievement. Even pre-kindergartenprograms such as Head Start are being heldaccountable for the learning of very youngchildren, most particularly with respect toearly language and literacy acquisition. Andcertainly, we know that the achievement gapbetween those of different economic and eth-nic/racial groups begins to evidence itself atthe outset of formal education. My colleagueRichard Coley presented a very fine analysisof the Early Childhood Longitudinal Surveylast year in his Policy Information CenterReport, An Uneven Start: Indicators of Inequal-ity in School Readiness.

If we are to improve early literacy for allour young people, we are going to have towisely make use of assessment. In Early Lit-eracy Assessment Systems: Essential Elements,Jacqueline Jones carefully describes howassessment can support policy, teaching, andlearning of those literacy skills that are thekey determinants of individuals’ future edu-cational success.

Jones has worked with schools in SouthBrunswick, New Jersey, and New York Cityto develop systems that help teachers gaininsight about their students’ progress andmake instructional decisions that improve stu-dent learning. For our youngest students, sheconvincingly urges us to avoid the seductive

trap of relying on any single test to provide allthe critical information needed to have aneffective and accountable educational system.Rather, she helps us see how different infor-mation sources can be used together to fulfilldifferent roles in providing critical informa-tion needed by different stakeholders in thesystem. But ultimately, she focuses most onhow assessment can assist teachers in helpingtheir students develop literacy skills.

Though this report focuses on assess-ments of early literacy, the lessons Jones pro-vides are worth attending to for older studentsas well. We need fundamentally differentforms of assessment to provide informationappropriate to different needs. The granular-ity of assessment information needed by teach-ers is far different from that needed bypolicymakers. The qualities of educationalleadership that are so compelling for schoolsinhabited by 5-year-olds are just as necessaryfor those attended by teenagers. If we canmake the recommendations of JacquelineJones a reality in all our schools, we havethe chance of achieving fully accountable,high-quality learning environments forall our students.

Drew GitomerSenior Vice PresidentResearch and DevelopmentEducational Testing Service

023990_PIP_TEXT_EarlyLit 5/30/03, 10:13 AM2

EARLY LITERACY ASSESSMENT SYSTEMS • 3

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This report was reviewed by Ted Chittenden,Richard Coley, Drew Gitomer, and Irv Sigelof Educational Testing Service; John Love ofMathematica Policy Research; Willa Spicer ofthe South Brunswick, New Jersey SchoolDistict; and Ed Greene, Montclair State

University. Lynn Jenkins was the editor; CarlaCooper provided desktop publishing; andMarita Gray designed the cover. Errors of factor interpretation are the responsibility of theauthor.

023990_PIP_TEXT_EarlyLit 5/30/03, 10:13 AM3

4 • EARLY LITERACY ASSESSMENT SYSTEMS

INTRODUCTION

The ability to read and write is essential tosuccessful participation in our society.

Extraordinary attention is currently beinggiven to early childhood education, with anemphasis on early literacy acquisition. Acrossthe country, politicians, educators, andresearchers are attempting to ensure thatyoung children are provided with the mostfavorable opportunities to develop strong lit-eracy skills. The desire to hold early childhoodeducators accountable for children’s literacyacquisition is strong, and the accountabilitymethods themselves have become a focusof discussion. This report will outline a sys-tem-wide framework for monitoring the lit-eracy development of children in preschoolthrough 2nd grade. Specific early literacyassessment instruments and instructionalapproaches will not be suggested. Rather, thisreport will focus on some of the essential ele-ments of an assessment system intended tomonitor the progress of young children’s lit-eracy development.

As a starting point, it is helpful to focuson two major factors that have led to the cur-rent emphasis on early literacy developmentand teacher accountability:

� Increased awareness of the importance ofearly development, and

� The achievement gap among kindergart-ners.

Increased Awareness of the Importance ofEarly Development

Although U.S. public education has longbeen committed to K-12 education, there is arecent and growing emphasis on the impor-tance of the first five years of life.1 Merelyproviding a safe and nurturing environmentfor young children is no longer adequate.Greater attention is being paid to early cogni-tive development, with an emphasis on lan-guage and literacy. This shift has resulted fromnew insights into the extraordinary amountof learning that takes place during the firstyears of life. A subcommittee of the NationalResearch Council and Institute of Medicineset out to update the state of knowledge onearly development. Their final conclusionsand recommendations were grounded on fourbroad themes:

� All children are born wired for feelings andready to learn.

� Early environments matter, and nurturingrelationships are essential.

1 Committee for Economic Development, Preschool for All: Investing in a Productive and Just Society, New York, 2002;National Research Council, Eager to Learn: Educating our Preschoolers, Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2001.

023990_PIP_TEXT_EarlyLit 5/30/03, 10:13 AM4

EARLY LITERACY ASSESSMENT SYSTEMS • 5

023990 88 02 P li I f P i d fil PM6 f @1 R d 6 03 k j 2CE /14/03 kb /1 /03 l

� Society is changing, and the needs of youngchildren are also changing.

� Interactions among early childhood sci-ence, policy, and practice are problematicand demand dramatic rethinking.2

In sum, children enter the world tryingto make sense of communication systems,rules of social interaction, and how thingswork. As a result, early childhood educatorsare now challenged to ensure that young chil-dren receive enriched cognitive, linguistic, andsocial-emotional stimulation even prior to thetraditional age of compulsory education

The Achievement Gap at Kindergarten

This new understanding of the impor-tance of early learning opportunities has beenaccompanied by the realization that socioeco-nomic status can be an important factor inearly language development. Economicallyadvantaged children often demonstrate a sig-nificant lead in language development overtheir less economically privileged peers. Mostdisturbing has been the finding that these eco-nomically based discrepancies in languagedevelopment can persist throughout theschool years, resulting in overall poor literacyacquisition.3

Using data from the Early ChildhoodLongitudinal Survey (ECLS-K), a recentreport from the ETS Policy InformationCenter examined differences in the readingreadiness of kindergartners grouped by gen-der, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status(SES), and age. The study revealed statisticallysignificant differences in reading readinessamong different subgroups of kindergartners.Socioeconomic status was strongly related toreading proficiency, as children in higher SESgroups were more likely to be proficient thanchildren in lower SES groups. The study alsoreported that Asian and White childrenwere more likely than children in otherracial/ethnic groups to be proficient acrossall reading tasks measured. However, nearlyall racial/ethnic differences in reading disap-peared when children were grouped into simi-lar SES levels.4

Concern About the Effectiveness ofPublic Education

Identifying such discrepancies in earlyreading has fueled concern that our publiceducation system may not be effective inteaching all children to read and write, espe-cially children from lower socioeconomicenvironments. Reactions to the achievementgap can be seen at both the state and federal

2 National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early ChildhoodDevelopment, Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2000.

3 The Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Class of 1998-99 (ECLS-K), conducted by the National Centerfor Education Statistics, is following approximately 20,000 children in 1,000 public and private schools from kindergartenthrough fifth grade. For early findings and a description of the survey, see Jerry West, Kristin Denton, and Elvira Geronimo-Hausken, America’s Kindergartners, National Center for Education Statistics, 2000.

4 Richard J. Coley, An Uneven Start: Indicators of Inequality in School Readiness, Policy Information Report, PolicyInformation Center, Educational Testing Service, March 2002.

023990_PIP_TEXT_EarlyLit 5/30/03, 10:13 AM5

6 • EARLY LITERACY ASSESSMENT SYSTEMS

023990 88 02 P li I f P i d fil PM6 f @1 R d 6 03 k j 2CE /14/03 kb /1 /03 l

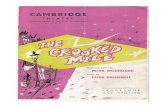

levels. One example of the state response isthe increasing number of states investing innon-compulsory education of 3- and 4-year-olds. As shown in Figure 1, according to Edu-cation Week, 39 states and the District ofColumbia now provide state-financed pre-kindergarten for at least some of their 3- to5-year-olds, up from 10 states in 1980.Annual state spending for such programs nowexceeds $1.9 billion, and there are growingpressures to gather data to show that the pro-grams are effective.

Despite the increase in state support forpreschool education, it should be noted thatteachers in these programs vary widely in

training and experience, and inevitably thequality of instructional programs often var-ies. Quality Counts (2002) reported that onlyseven states require pre-K programs to beaccredited, and while all states require theirkindergarten teachers to have a B.A., only 21require a B.A. for child care center teachers.5

One of the most ambitious state-levelattempts to close the achievement gapbetween advantaged and disadvantaged youngchildren is taking place in New Jersey. In 1988the class action known as Abbott v. Burkeresulted in the New Jersey Supreme Courtordering the State Department of Educationto provide universal preschool to 3- and

0 10 20 30 40 50

42

26

40

7

51

21

1

Require districts to provide kindergarten

Pay for all-daykindergarten

Provide funds forpre-K programs

Require pre-K programsto be nationally accredited

Require kindergarten teachersto have a B.A.

Require pre-K teachersto have a B.A.

Require child-care-centerteachers to have a B.A.

States that:

Number of States (including D.C.)

FIGURE 1: STATE EARLY-CHILDHOOD POLICIES

5 Education Week, Quality Counts 2002, Building Blocks for Success, January 10, 2002.

Source: Education Week, Quality Counts 2002.

023990_PIP_TEXT_EarlyLit 5/30/03, 10:13 AM6

EARLY LITERACY ASSESSMENT SYSTEMS • 7

023990 88 02 P li I f P i d fil PM6 f @1 R d 6 03 k j 2CE /14/03 kb /1 /03 l

6 Education Law Center, http://www.edlawcenter.org/ELCPublic/AbbottPreschool/AbbottPreschoolProgram.htm

4-year-olds in 30 of the state’s most under-achieving urban districts. The court ruled that,“Intensive preschool and full-day kindergar-ten enrichment programs are necessary toreverse the educational disadvantages thesechildren start out with” (Abbott v. Burke,1998). The New Jersey Supreme Courtordered the state’s Department of Educationto provide the following pre-K programming:

� Universal Eligibility - all 3- and 4-year-old children, with enrollment on demand;

� District-led Collaboration - preschoolcontracts with community and Head Startprograms able and willing to meet theAbbott quality standards;

� Qualified Teachers and Small Classes -no more than 15 children per class, staffedby a state-certified (P-3) teacher and anassistant;

� Adequate Facilities and Funding - state-provided facilities and funding, adequateto meet district needs;

� Preschool Curriculum - developmentallyappropriate curriculum, aligned with theNew Jersey Core Curriculum ContentStandards and elementary school reforms;

� Related Services - social and health ser-vices, transportation, and services for chil-dren with disabilities and with limitedEnglish proficiency, as needed; and

� District Support and Accountability -supervision, technical assistance, and pro-fessional development and evaluation toassure uniform high quality.6

Improvements to facilities, caps on classsize, and new teacher certification require-ments are part of the effort that is estimatedto cost New Jersey $355 million in the 2002fiscal year.

At the federal level, the No Child LeftBehind Act of 2001 authorized two new read-ing programs: Reading First, funded at $900million in the 2002 fiscal year, and Early Read-ing First, funded at $75 million. These pro-grams are intended to enhance the languageand literacy skills of all children and to elimi-nate the achievement gaps among racial/eth-nic and socioeconomic groups. Funds maybe used to select and administer screening,diagnostic, and classroom-based instructionalreading assessments; purchase instructionalmaterials; provide teacher professional devel-opment; and conduct program evaluation.

023990_PIP_TEXT_EarlyLit 5/30/03, 10:13 AM7

8 • EARLY LITERACY ASSESSMENT SYSTEMS

Recently, groups of experts have cometogether to explore the issue of what consti-tutes appropriate and effective literacy peda-gogy for young children. A 1998 report fromthe National Research Council sought to pro-mote a balanced approach to reading instruc-tion.7 Its broad conclusions are included inFigure 2. Charged with “conducting a studyof the effectiveness of interventions foryoung children who are at risk of having prob-lems learning to read,” the Council set threeproject goals:

(1) to comprehend a rich but diverseresearch base;

(2) to translate the research findings intoadvice and guidance for parents, edu-cators, publishers, and others involvedin the care and instruction of theyoung; and

(3) to convey this advice to the targetedaudiences through a variety of publi-cations, conferences, and other out-reach activities.

In 2000, the National Reading Panel pub-lished a review of early literacy studies thatthey defined as “scientifically based” research.8

That is, the group focused “exclusively onresearch that had been published or had beenscheduled for publication in refereed (peerreviewed) journals... [N]on-peer-revieweddata were treated as preliminary/pilot data thatmight illuminate potential trends and areasfor future research.” The panel concluded thatfive factors constituted the most importantcomponents of reading instruction:

� Phonemic awareness - Phonemic aware-ness refers to the ability to focus on andmanipulate phonemes in spoken words.

� Phonics - Systematic phonics instructionis a way of teaching reading that stressesthe acquisition of letter-sound correspon-dences and their use to read and spellwords.9

� Fluency - Fluent readers can read text withspeed, accuracy, and proper expression.

ISSUES IN LITERACY INSTRUCTION

E ducators have differed for some time on whichinstructional strategies are most effective in teaching children to read.

7 Catherine E. Snow, M. Susan Burns, and Peg Griffin (Eds.), Preventing Reading Difficulties in Young Children, NationalResearch Council, Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1998.

8 National Reading Panel, Report of the National Reading Panel: Teaching Children to Read, An Evidence-Based Assessmentof the Scientific Research Literature on Reading and its Impact for Reading Instruction, Washington, DC: NIFL, NICHD, 2000.

9 T.L. Harris and R.E. Hodges (Eds.), The Literacy Dictionary: The Vocabulary of Reading and Writing, Newark, DE:International Reading Association, 1995.

023990_PIP_TEXT_EarlyLit 5/30/03, 10:13 AM8

EARLY LITERACY ASSESSMENT SYSTEMS • 9

023990 88 02 P li I f P i d fil PM6 f @1 R d 6 03 k j 2CE /14/03 kb /1 /03 l

FIGURE 2: CONCLUSIONS FROM THE NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL

REGARDING APPROPRIATE READING INSTRUCTION

Adequate initial reading instruction requires that children:

� Use reading to obtain meaning from print,� Have frequent and intensive opportunities to read,� Be exposed to frequent, regular opportunities to read,� Learn about the nature of the alphabetic writing system, and� Understand the structure of spoken words.

Adequate progress in learning to read English (or any alphabetic language)beyond the initial level depends on:

� Having a working understanding of how sounds are represented alphabetically,� Sufficient practice in reading to achieve fluency with different kinds of texts,� Sufficient background knowledge and vocabulary to render written text mean-

ingful and interesting,� Control over procedures for monitoring comprehension and repairing misun-

derstandings, and� Continued interest and motivation to read for a variety of purposes.

Source: National Research Council, Eager to Learn: Educating Our Preschoolers, Washington, DC:National Academy Press, 2001.

Fluency depends upon well-developed wordrecognition skills, but such skills do notinevitably lead to fluency.

� Vocabulary - The importance of vocabu-lary in reading comprehension has been rec-ognized for more than half a century. In1925, Whipple stated, “Growth in readingpower means, therefore, continuous enrich-ing and enlarging of the reading vocabu-

lary and increasing clarity of discriminationin appreciation of word values.”10

� Text comprehension - Comprehension hascome to be viewed as “the essence of read-ing.... Comprehension strategies are specificprocedures that guide students to becomeaware of how they are comprehending asthey attempt to read and write.”11

10 G. Whipple (Ed.), The Twenty-fourth Yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education: Report of the NationalCommittee on Reading, Bloomington, IL: Public School Publishing Company, 1925.

11 D. Durkin, Teaching Them to Read (6th ed.), Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon, 1993.

023990_PIP_TEXT_EarlyLit 5/30/03, 10:13 AM9

10 • EARLY LITERACY ASSESSMENT SYSTEMS

023990 88 02 P li I f P i d fil PM6 f @1 R d 6 03 k j 2CE /14/03 kb /1 /03 l

Although these five components do notconstitute an exhaustive list of reading skills,they do represent important elements of read-ing development. Sound reading programswill balance decoding, comprehension, andhigh-interest materials. While debate contin-ues on how to implement early literacyinstruction, the groups do not hold entirelyantithetical notions of what represents thebasics of becoming literate—cracking a code,understanding the text, and having frequentopportunities to read interesting material.

Regardless of the instructional approachto literacy development, educators needeffective strategies to inform classroom prac-tice and to monitor children’s progress.Assessment needs and demands go beyondthis, however. The increased focus on earlyliteracy initiatives, the new thrust to provideenriched learning environments for young

children, and the persistent achievement gapsamong specific subgroups of students haveraised the inevitable call for accountability.Meeting these diverse needs for assessmentinformation is, of course, a complex under-taking. What is required is not merely a newset of standardized instruments, but a coordi-nated system for monitoring children’s literacydevelopment—one that incorporates appro-priate learning goals, multiple measures oflearning, administrative leadership, and on-going professional development for teachers.

The following section outlines majorissues in the design of an effective early lit-eracy assessment system. The componentsdescribed have emerged from the study of thedesign and implementation of early literacyassessment systems that inform instructionalpractice and meet accountability needs.12

12 See Brent Bridgeman et al., Characteristics of a Portfolio Scale for Rating Early Literacy, Princeton, NJ: Educational TestingService, 1995; Jacqueline Jones and Edward Chittenden, Teachers’ Perceptions of Rating an Early Literacy Portfolio, Princeton, NJ:Educational Testing Service, 1995; Ruth Mitchell, Testing for Learning: How New Approaches to Evaluation Can Improve AmericanSchools, New York: The Free Press, 1992; Joe Murphy, “Leadership for Literacy: Policy Leverage Points,” paper presented at theEducational Testing Service/Education Commission of the States Conference on Leadership for Literacy, Washington, DC,October 9, 2001.

023990_PIP_TEXT_EarlyLit 5/30/03, 10:13 AM10

EARLY LITERACY ASSESSMENT SYSTEMS • 11

ISSUES IN THE ASSESSMENT OF YOUNG CHILDREN

The question of how to assess young childrenappropriately has challenged educators for some time.13

In 1987 the nation’s largest childhood orga-nization, the National Association for theEducation of Young Children (NAEYC),issued a position statement, shown inFigure 3, that calls for careful considerationof the purpose, selection, and use of stan-dardized tests with young children. Earlychildhood experts in NAEYC and other pro-fessional groups, such as the National Asso-ciation for Early Childhood Specialists in StateDepartments of Education (NAECS/SDE),have continued to consider what constitutessound assessment of children below grade 3.14

The process of ongoing assessment shouldbe distinguished from the administration ofstandardized norm-referenced tests. In theirjoint set of standards for educational and psy-chological testing, the American Educational

Research Association (AERA), the AmericanPsychological Association (APA), and theNational Council on Measurement in Educa-tion (NCME) have defined assessment as “Anysystematic method of obtaining informationfrom tests and other sources, used to drawinferences about characteristics of people,objects, or programs.”15

Lorrie Shepard and her colleagues haveproposed a set of principles and purposes toguide the overall assessment of young children(see Figure 4). These researchers argue that,particularly below 3rd grade, the primary pur-pose of assessment is to provide the teacherwith information that can be used to guideand improve instruction. Therefore, assess-ment of young children below 3rd gradeshould be centered on classroom-based

13 See Edward Chittenden and Rosalea Courtney, “Assessment of Young Children’s Reading: Documentation as anAlternative to Testing,” in Emerging Literacy: Young Children Learn to Read and Write, Dorothy S. Strickland and Leslie M.Morrow (Eds.), Newark, DE: International Reading Association, Inc, 1989; Henry S. Dyer, “Testing Little Children: Some OldProblems in New Settings,” Childhood Education, 49 (7), 362-367, 1973; Celia Genishi (Ed.), Ways of Assessing Children andCurriculum, New York: Teachers College Press, 1992; Lorrie A. Shepard, “The Challenges of Assessing Young ChildrenAppropriately,” Phi Delta Kappan, 76 (3), 206-212, 1994.

14 National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) and National Association of Early ChildhoodSpecialists in State Departments of Education (NAECS/SDE), Guidelines for Appropriate Curriculum Content and Assessment inPrograms Serving Children Ages 3 Through 8, 1992. www.naeyc.org. (Revised statement due out in Summer, 2003.)

15 American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, and the National Council forMeasurement in Education, Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing, Washington, DC: American EducationalResearch Association, 1999.

023990_PIP_TEXT_EarlyLit 5/30/03, 10:13 AM11

12 • EARLY LITERACY ASSESSMENT SYSTEMS

023990 88 02 P li I f P i d fil PM6 f @1 R d 6 03 k j 2CE /14/03 kb /1 /03 l

NAEYC believes that the most important consideration in evaluating and using standardizedtests is the utility criterion: The purpose of testing must be to improve services for childrenand ensure that children benefit from their educational experiences. Decisions about testingand assessment instruments must be based on the usefulness of the assessment procedure forimproving services to children and improving outcomes for children. The ritual use even of“good tests” (those that are judged to be valid and reliable measures) is to be discouraged inthe absence of documented research showing that children benefit from their use.

The following guidelines are intended to enhance the utility of standardized tests and guideearly childhood professionals in making decisions about the appropriate use of testing.

� All standardized tests used in early childhood programs must be reliable and validaccording to the technical standards of test development.*

� Decisions that have a major impact on children, such as enrollment, retention, orassignment to remedial or special classes, should be based on multiple sources ofinformation and should never be based on a single test score.

� It is the professional responsibility of administrators and teachers to critically evaluate,carefully select, and use standardized tests only for the purpose for which they areintended and for which data exists demonstrating the test’s validity (the degree to whichthe test accurately measures what it purports to measure).

� It is the professional responsibility of administrators and teachers to be knowledgeableabout testing and to interpret test results accurately and cautiously to parents, schoolpersonnel, and the media.

� Selection of standardized tests to assess achievement and/or evaluate how well a programis meeting its goals should be based on how well a given test matches the locally deter-mined theory, philosophy, and objectives of the specific program.

� Testing of young children must be conducted by individuals who are knowledgeableabout and sensitive to the developmental needs of young children and who are qualifiedto administer tests.

� Testing of young children must recognize and be sensitive to individual diversity.

*American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, National Councilon Measurement in Education, Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing, Washington, DC:American Education Research Association, 1985.

�1987 National Association for the Education of Young Children

Source: National Association for the Education of Young Children, Standardized Testing of YoungChildren 3 Through 8 Years of Age, Washington, DC, 1987.

FIGURE 3: NAEYC POSITION STATEMENT ON STANDARDIZED TESTING

OF YOUNG CHILDREN 3 THROUGH 8 YEARS OF AGE

023990_PIP_TEXT_EarlyLit 5/30/03, 10:14 AM12

EARLY LITERACY ASSESSMENT SYSTEMS • 13

023990 88 02 P li I f P i d fil PM6 f @1 R d 6 03 k j 2CE /14/03 kb /1 /03 l

Assessment should bring about benefits for children.

Assessments should be tailored to a specific purpose and should be reliable, valid, and fairfor that purpose.

Assessment policies should be designed recognizing that reliability and validity of assess-ments increase with children’s age.

Assessments should be age-appropriate in both content and the method of data collection.

Assessments should be linguistically appropriate, recognizing that to some extent allassessments are measures of language.

Parents should be a valued source of assessment information, as well as an audience forassessment results.

Major Purposes of Early Childhood Assessment

� Assessments to support learning,� Assessments for identification of special needs,� Assessments for program evaluation and monitoring trends, and� Assessments for high-stakes accountability.

Source: Lorrie Shepard, Sharon L. Kagan, and Emily Wirtz, Principles and Recommendations for EarlyChildhood Assessments, Washington, DC: National Education Goals Panel, 1998.

FIGURE 4: GENERAL PRINCIPLES AND PURPOSES OF EARLY CHILDHOOD ASSESSMENT

evidence of learning rather than externallydesigned norm-referenced, standardizedmeasures.

Finally, early literacy assessment wasaddressed directly in the Joint PositionStatement of the International ReadingAssociation (IRA) and NAEYC. The twoorganizations outlined a set of principlesfor appropriate literacy assessment of youngchildren, and these are shown in Figure 5.

In general, these positions highlightappropriate early childhood assessment as ameans of understanding how young childrenare developing competence and as a tool toinform instructional practice. The followingsections will outline some of the elements ofan effective early literacy assessment system.

To provide the appropriate educationalexperiences that can promote literacy devel-opment in all young children, educators will

023990_PIP_TEXT_EarlyLit 5/30/03, 10:14 AM13

14 • EARLY LITERACY ASSESSMENT SYSTEMS

023990 88 02 P li I f P i d fil PM6 f @1 R d 6 03 k j 2CE /14/03 kb /1 /03 l

FIGURE 5: JOINT NAEYC/IRA POSITION STATEMENT

Principles of Assessment in Reading and Writing

Assessment should support children’s development and literacy learning.Assessment should take many different forms.Assessment must avoid cultural bias.Assessment should encourage children to observe and reflect on their own learning progress.Assessment should shed light on what children are able to do as well as the areas where they need further work.

Assessment Procedures

Anecdotal notesNarratives, story retellingWriting foldersInstructional conversationsEmergent storybook readingsInformal reading inventoriesRunning records

Source: Susan B. Neuman, Carol Copple, and Susan Bredekamp, Learning to Read and Write:Developmentally Appropriate Practices for Young Children, Washington, DC: National Associationfor the Education of Young Children, 2000.

need to design appropriate learning goals,implement sound instructional strategies,institute comprehensive monitoring systemsthat reflect and inform classroom practice, andprovide for a well-trained and adequatelysupported teaching force. To this end, thoseresponsible for the education of young chil-dren must:

� Acquire the skills necessary to select, use,and interpret multiple measures of literacydevelopment that are aligned to clear andappropriate standards;

� Recognize the critical role that sound lead-ership plays in a useful assessment system;and

� Provide the teaching staff with a coherentprogram of professional development tohelp them develop knowledge and skillsthat will enable them to successfully buildchildren’s literacy skills, monitor children’sprogress, and apply assessment informationto their instructional practice.

023990_PIP_TEXT_EarlyLit 5/30/03, 10:14 AM14

EARLY LITERACY ASSESSMENT SYSTEMS • 15

ELEMENTS OF EFFECTIVE EARLY

LITERACY ASSESSMENT SYSTEMS

Perhaps the single most unifying concept in the arena

of early literacy instruction and assessment is recognition of the need for multiple assessment measures.

Multiple Forms of Evidence of EarlyLiteracy Development

The early childhood community, the nationalreading organizations, and the measurementcommunity have issued policy statementsopposing the use of a single assessment instru-ment to determine literacy progress for high-stakes purposes.16 In testimony before theHouse Subcommittee on Education Reform,Reid Lyon, Chief of the Child Developmentand Behavior Branch, National Institutes ofHealth, spoke of the role of assessments in theNo Child Left Behind legislation: “ThePresident’s proposed reading programs recog-nize both the importance of assessment andthe fact that assessments have multiple pur-poses, including early identification, diagno-sis, program evaluation, and accountability. Asingle test cannot address all these purposes.”17

Further, as Catherine Snow and JacquelineJones have stated, “... tests, by themselves, can-not improve educational outcomes. They canlead to improvement only if they become a

stimulus to change in the educational system—a basis for improved curricula, upgradedinstruction, better professional developmentfor teachers, and better distribution ofresources.”18 No single test instrument will besufficient to promote good teaching, trackchildren’s progress, signal when children aredemonstrating potential problems, and provideuseful feedback to teachers. As illustrated inFigure 6, some instruments are designed to pro-vide more information about individual stu-dents than others.

Classroom-based assessments that aredirectly linked to the instructional program canprovide a rich source of information on a singlechild or a group of children. Conversely, large-scale national assessments, such as the NationalAssessment of Educational Progress (NAEP),are intended to provide a big picture of groupprogress. In the case of NAEP, individual chil-dren take blocks of the assessment; no childtakes the entire test. Therefore, no generaliza-tions can be made about a specific child. Soundearly literacy assessment systems should include

16 International Reading Association, High-stakes Assessment in Reading, Newark, DE, 1999; American EducationalResearch Association, 1999; and National Association for the Education of Young Children, Standardized Testing of YoungChildren 3 Through 8 Years of Age, Washington, DC, 1987.

17 G. Reid Lyon, Measuring Success: Using Assessments and Accountability to Raise Student Achievement, Subcommittee onEducation Reform, Committee on Education and the Workforce, Washington, DC, 2001.

18 Catherine E. Snow and Jacqueline Jones, “Making a Silk Purse: How a National System of Annual Testing Might Work,”Education Week, April 25, 2001.

023990_PIP_TEXT_EarlyLit 5/30/03, 10:14 AM15

16 • EARLY LITERACY ASSESSMENT SYSTEMS

023990 88 02 P li I f P i d fil PM6 f @1 R d 6 03 k j 2CE /14/03 kb /1 /03 l

the range of assessments, from informing andreflecting classroom practice to serving schooldistrict and state program evaluation needs.Screening measures, classroom-based assess-ments, and program evaluation measures con-stitute the major types of assessment instru-ments that can yield important informationin an early literacy assessment system. Each isconsidered below.

� Screening measures are gross indicators ofwhether children are generally progressingon course or whether there are major prob-lems, such as visual or auditory obstacles

to learning. They serve as a first step in iden-tifying children who may be at high riskfor delayed development or academic fail-ure, or who are in need of further evalua-tion for special services. While screeninginstruments are not intended to guideinstructional interventions, they can serveas red flags to alert educators of potentialdifficulties.19

� Classroom-based literacy assessments canprovide powerful evidence of children’s lit-eracy acquisition. As Lorrie Shepard and hercolleagues have argued, the major purpose

FIGURE 6: RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN LEVEL OF ASSESSMENT AND

KNOWLEDGE OF SPECIFIC STUDENTS

Source: Robert J. Marzano and John S. Kenall, A Comprehensive Guide to Designing Standards-BasedDistricts, Schools, and Classrooms, Copyright 1996, McREL. Reprinted with permission of McREL.

No knowledge

of specific students

In-depth knowledge

of specific students

NationalAssessments

StateAssessments

DistrictAssessments

ClassroomAssessments

19 John M. Love, Instrumentation for State Readiness Assessment: Issues in Measuring Children’s Early Development andLearning, Princeton, NJ: Mathematica Policy Research, 2001.

023990_PIP_TEXT_EarlyLit 5/30/03, 10:14 AM16

EARLY LITERACY ASSESSMENT SYSTEMS • 17

023990 88 02 P li I f P i d fil PM6 f @1 R d 6 03 k j 2CE /14/03 kb /1 /03 l

Cycle, developed by ETS Research andDevelopment and shown in Figure 7, class-room-based literacy assessments are an in-tegral part of the teaching/learning process.

In the documentation-assessment process,teachers are guided through a five-stagecycle.

Stage 1. Identifying learning goals andthe evidence of learningStage 2. Collecting the evidence over time

of early childhood assessment is to informinstructional practice. Classroom-basedassessments that are tied to classroomexperiences in which children play, engagein conversations, and construct meaningcan guide future instruction by providingvaluable information about literacy devel-opment. This evidence should be continu-ally measured against a set of clearlydefined, challenging, and appropriate lit-eracy goals. As illustrated in the 5-StageEarly Literacy Documentation-Assessment

FIGURE 7: 5-STAGE EARLY LITERACY DOCUMENTATION-ASSESSMENT CYCLE

Copyright © 2003 by Educational Testing Service. All rights reserved.

023990_PIP_TEXT_EarlyLit 5/30/03, 10:14 AM17

18 • EARLY LITERACY ASSESSMENT SYSTEMS

023990 88 02 P li I f P i d fil PM6 f @1 R d 6 03 k j 2CE /14/03 kb /1 /03 l

Stage 3. Describing evidence in a non-evaluative mannerStage 4. Interpreting evidence in order toidentify mastery of established goalsStage 5. Applying this new information toinform instruction to support learning.

In Stage 1 of the cycle, appropriate literacygoals and the classroom activities andexperiences that will help children masterthe goals are identified. Stage 1 also in-cludes identification of what will consti-tute evidence that children have achievedthe goals.

The teacher collects the classroom-basedevidence of early literacy development inStage 2. This evidence may consist ofrecords of children’s conversations andsamples of children’s work, such as draw-ings, writings, and constructions.

In Stage 3 of the Documentation-Assess-ment Cycle, teachers work collaborativelyto describe what they see in the records ofchildren’s language and in work samples.This stage is modeled on Patricia Carini’sdescriptive review process in which teach-ers engage in a close analysis of children’swork.20

In Stage 4, the classroom-based evidenceof early literacy development is weighedagainst the goals identified in Stage 1of the cycle. It is in Stage 5 that the

information gained in Stages 1-4 is usedto plan future instruction and to planadditional assessment opportunities.

Teachers benefit most from the documen-tation-assessment process when theywork collaboratively, sharing strategies forcollecting evidence of children’s literacydevelopment and engaging in descriptionsand interpretations of that evidence. Theprocess can enhance teachers’ recognition,observation, and understanding of the evi-dence of young children’s emerging literacylearning. At the heart of identifying andcollecting classroom-based data is theteachers’ ability to become a keen observerand listener of children.

� Program evaluation and accountability areessential aspects of any system-wide work.Assessments such as NAEP, currentlyadministered at grades 4, 8, and 12, canprovide an overall look at how specificgroups of children are progressing alongtoward a defined set of outcomes. How-ever, these results are not intended to givespecific information on the progress ofindividual children or to provide instruc-tional strategies for teachers.

As educational systems move towardmonitoring children’s literacy development,the types of assessments described above mustmeet technical specifications if the results theyyield are to be of value to teachers and

20 Patricia Carini, Observation and Description: An Alternative Methodology for the Investigation of Human Phenomena,Grand Forks, ND: University of North Dakota Press, 1975; Patricia Carini, The Descriptive Review of the Child: A Revision,North Bennington, Vermont: Prospect Center, 1993.

023990_PIP_TEXT_EarlyLit 5/30/03, 10:14 AM18

EARLY LITERACY ASSESSMENT SYSTEMS • 19

023990 88 02 P li I f P i d fil PM6 f @1 R d 6 03 k j 2CE /14/03 kb /1 /03 l

children. Figure 8 shows a set of standards foraccountability systems outlined by staff fromthe National Center for Research on Evalua-tion, Standards, and Student Testing(CRESST).

In general, effective early literacy assess-ment systems should include multiple typesof assessments for multiple purposes, assurethat all the measures are as valid and reliableas possible, and provide for clear and accuratereporting. Systems need to develop strategiesto ensure that assessment instruments areadministered and interpreted in comparableand consistent ways.21 No system canaccommodate all of these factors without acommitted and informed administrative andteaching staff. The critical role of leadershipin the success of a system-wide assessment sys-tem follows.

The Role of Leadership

If the achievement gap is to be closed,system-wide solutions are needed. Factors be-yond the assessment instruments can be criti-cal determinants in the design and implemen-tation of an effective assessment system.Research suggests that school districts thathave been most successful in educating all chil-dren share some common attributes, andparamount among those commonalities isleadership that creates a shared vision of

success and provides the staff with the toolsto meet that vision. No matter how dedicatedor well-trained, teachers cannot affect lasting,systemic change by themselves. Good teach-ing and good teachers need to be valued andsupported by a rational system.

Leadership is not an individual. No singleadministrator can design, implement, andnurture an early literacy assessment system.Rather, leadership consists of the coordinatedefforts among an administrative staff thatshares a common vision. Joe Murphy has out-lined the leadership components of success-ful literacy programs and these are providedbelow (in italics).22

� Establishing clearly defined, challenging,and public standards that are the focusof policymaking, institutional structures,and activities. Everything is centered onaccomplishing the learning goals thathave been defined. No assessment systemcan be effective and useful to teachers un-less it is grounded in a clearly defined andpublic set of standards. So it is that earlyliteracy assessment depends on a commondefinition of the literacy goals for youngchildren. Whatever the emphasis on pho-nemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabu-lary, comprehension, or appreciation oftext, the literacy goals must be clear toall educators and aligned with each

21 Eva L. Baker, H.F. O’Neil, and Robert L. Linn, “Policy and Validity Prospects for Performance-Based Assessment,”American Psychologist, 48 (12), 1993. Also see Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing (cited earlier).

22 Murphy, 2001.

023990_PIP_TEXT_EarlyLit 5/30/03, 10:14 AM19

20 • EARLY LITERACY ASSESSMENT SYSTEMS

023990 88 02 P li I f P i d fil PM6 f @1 R d 6 03 k j 2CE /14/03 kb /1 /03 l

Accountability Systems

� Accountability expectations should be made public and understandable for allparticipants in the system.

� Accountability systems should employ different types of data from multiplesources.

� Accountability systems should include data elements that allow for interpreta-tions of student, institution, and administrative performance.

� Accountability systems should include the performance of all students, includ-ing subgroups that historically have been difficult to assess.

� The weighting of elements in the system, including different types of testcontent and different information sources, should be made explicit.

� Rules for determining adequate progress of schools and individuals should bedeveloped to avoid erroneous judgments attributable to fluctuations of thestudent population or errors in measurement.

� Longitudinal studies should be planned, implemented, and reported evaluatingeffects of the accountability program. Minimally, questions should determinethe degree to which the system:

a. builds capacity of the staff;b. affects resource allocation;c. supports high-quality instruction;d. promotes student equity access to education;e. minimizes corruption;f. affects teacher quality, recruitment, and retention; andg. produces unanticipated outcomes.

� The validity of test-based inferences should be subject to ongoing evaluation. Inparticular, evaluation should address aggregate gains in performance over timeand impact on identifiable student and personnel groups.

Source: Eva L. Baker, Robert L. Linn, Joan E. Herman, and Daniel Koretz, Standards for EducationalAccountability Systems, Los Angeles, CA: National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, andStudent Testing (CRESST), 2002.

FIGURE 8: STANDARDS FOR SYSTEM COMPONENTS

023990_PIP_TEXT_EarlyLit 5/30/03, 10:14 AM20

EARLY LITERACY ASSESSMENT SYSTEMS • 21

023990 88 02 P li I f P i d fil PM6 f @1 R d 6 03 k j 2CE /14/03 kb /1 /03 l

assessment. A major responsibility of earlychildhood leaders is to guide their educa-tors in defining a set of challenging and ap-propriate literacy goals for young children.

� Creating a shared belief that all childrencan learn and that the educators have theknowledge, skills, and resources to engagein effective teaching. No program can besuccessful without the deeply held beliefthat all children can and will become liter-ate. While individual differences will cer-tainly be demonstrated, and some childrenwill be better readers or writers than oth-ers, teachers must feel they have the neces-sary skills and resources (human as well asmaterial) to guide each child to successfulliteracy development. Accordingly, teach-ers need a wide range of literacymaterials, as well as support from otherstaff within the school—including specialeducation staff—in order to provide fullydifferentiated instruction that addressesstudents’ diverse needs. As noted in alater section, professional development isalso vital.

� Guiding the assessment system. An assess-ment system cannot survive without admin-istrative guidance and support. In addition,a person or group within the school musthave a deep knowledge of (a) how youngchildren learn to read and write and (b)what constitutes appropriate literacy goalsand instructional programs. A variety ofassessments can then be aligned to the learn-ing goals.

� Providing the early literacy expertise toensure that teachers are implementing ahigh-quality instructional program thatcan help children meet the district’s learn-ing goals. Early childhood leaders mustlook carefully at the plethora of readingprograms and decide which instructionalprogram is best aligned with their literacygoals and has a proven record of success.Someone with expertise in early literacydevelopment must be either on staff oravailable to the staff as these instructionaldecisions are made.

� Providing, honoring, and protecting thetime that teachers and other staff need tocarry out their work. There must be suffi-cient time to do the work. The most pre-cious commodity in most schools is notmoney; it’s time. Supportive administratorsrecognize that teachers need time to plan,teach, reflect, and collaborate with their col-leagues. That time must be honored, pro-vided, and protected.

� Creating a system of monitoring progresstoward the specified goals and ensuringthat this information is used and under-stood. Early childhood administrators mustestablish and support the means throughwhich assessment information is commu-nicated to educators and parents to showhow children are progressing toward thelearning goals. This assessment informationmay be conveyed through report cards, par-ent conferences, or other means.

023990_PIP_TEXT_EarlyLit 5/30/03, 10:14 AM21

22 • EARLY LITERACY ASSESSMENT SYSTEMS

023990 88 02 P li I f P i d fil PM6 f @1 R d 6 03 k j 2CE /14/03 kb /1 /03 l

� Providing for a coherent system of pro-fessional development activities thatenable teachers to plan appropriate instruc-tional programs, teach, gather the evidenceof children’s learning, reflect on thatinformation with colleagues and individu-ally, and apply what they have learned totheir ongoing classroom practice.

� Maintaining a stable district adminis-tration that keeps the vision of the work,ensures consistent implementation, andoffers a coherent system of policies andprocedures. Frequent changes in adminis-trators can create changing visions andshifting definitions of success. The focuson literacy may be lost, instructionalprograms can cease to be aligned to a setof standards, or the literacy goals may shiftand become unclear. Long-term stabilityin administration helps to sustain thefocus of early literacy programs over time.

� Creating an educational partnershipbetween the school and the home. Par-ents of young children play a critical role,and the work of improving early childhoodeducation cannot be accomplished with-out a strong educational partnershipbetween parents and educators.

TEACHER PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

Research tells us that teachers are at theheart of any successful reform initiative.23 Thepreparation and ongoing development of well-trained teachers and administrators is there-fore key to closing the achievement gap. Ifimproving instruction is the primary purposeof early childhood assessment, teachers needto be able to design classroom assessments anduse the resulting information to guidetheir practice.

In addition, administrators must be ableto select screening and accountability instru-ments that are aligned with their instructionalprogram and to accurately interpret andreport the results. These are daunting tasksfor most educators, however. Richard Stigginshas argued that educators need to develop amuch greater degree of “assessment literacy”if they are to monitor student progress in ameaningful manner.24 The lack of attentionto the design and appropriate use of class-room-based assessments in early childhoodteacher preparation programs has played amajor role in creating a teaching force thatholds negative views toward testing and lacksthe expertise to develop or use the classroom-based strategies that are appropriate for assess-ing young children’s progress.

23 National Commission on Teaching and America’s Future, What Matters Most: Teaching for America’s Future, September1996.

24 Richard J. Stiggins, “Assessment Literacy,” Phi Delta Kappan, 72 (7), 1991; Richard J. Stiggins, “Evaluating ClassroomAssessment Training in Teacher Education Programs,” Educational Measurement: Issues and Practices, 18 (1), 1999; and Richard J.Stiggins, “The Unfulfilled Promise of Classroom Assessment,” Educational Measurement: Issues and Practices, 20 (3), 2001.

023990_PIP_TEXT_EarlyLit 5/30/03, 10:14 AM22

EARLY LITERACY ASSESSMENT SYSTEMS • 23

023990 88 02 P li I f P i d fil PM6 f @1 R d 6 03 k j 2CE /14/03 kb /1 /03 l

An essential element of an effective earlyliteracy assessment system is a coherent andcomprehensive set of professional developmentactivities that are targeted to enhancing class-room teachers’ and administrators’ assessment-related knowledge and skills. Educators mustbe equipped to select the most suitable set ofinstruments, administer them appropriately,and interpret the results to other teachers, par-ents, school boards, and state departments ofeducation. In addition, it is critical that teach-ers play a key role in the design and ongoingrevision of their assessment system. As ScottParis and colleagues suggest, “It may takeseveral years for all teachers to understandassessment practices and use them in similarways. Consensus is built upon regular reflec-tion and discussion among teachers about whatassessments are working well, how the assess-ments support parent conferences and reportcards, and how assessments help individualchildren.”25

25 Scott G. Paris, Alison H. Paris, and Robert D. Carpenter, Effective Practices for Assessing Young Readers (CIERA Report#3-013), Ann Arbor, Michigan: Center for Improvement of Early Reading Achievement, 2001.

023990_PIP_TEXT_EarlyLit 5/30/03, 10:14 AM23

24 • EARLY LITERACY ASSESSMENT SYSTEMS

The South Brunswick, New Jersey, school dis-trict designed and implemented an early lit-eracy portfolio and scale that has been opera-tional for over 10 years. The portfolio andscale were designed to monitor the literacydevelopment of all kindergarten through 2ndgrade children in the district. The assessmentsystem was intended both to inform teachers’instruction and to serve as an accountabilitymeasure.

Components of the South BrunswickEarly Literacy Profile are listed in Figure 9.As the figure shows, a variety of forms of in-formation or “literacy evidence” is collectedfor each student. This information is thenused by teachers, at least twice during everyschool year, to assess and document eachchild’s literacy development using the district’sEarly Literacy Scale. This scale is organizedaround six major phases in the normal devel-opment of children’s emerging abilities tomake sense of print (see Figure 10).

The committee of teachers who createdthe initial instrument drew upon the existingbody of research on early literacy developmentin defining each stage of emergent literacy.The constellation of behaviors at any givenstage grows out of preceding stages. The scaleis not a checklist of specific behaviors. Instead,it attempts to embody the assumptions about

children’s language, reading, and writing thatunderlie the district’s notions of appropriatecurriculum. The scale represents the district’spublic set of literacy goals for kindergartenthrough 2nd grade children, with each stageserving as a benchmark as children become“Advanced Independent” readers.

Each point on the early literacy scale isdescribed in terms of the strategies and under-standings that children typically bring to textat a given stage. The descriptors are explicitlyreferenced to types of behaviors that teachersmight observe in the portfolio documents. Fur-thermore, there is a consistent attempt at eachpoint to characterize children’s literacy learn-ing in terms of what they can do rather thanwhat they can’t do. For example, the child isdescribed as “indicating a beginning sense ofone-to-one correspondence” in attempts to readtext, word for word.

At least twice a year, each kindergartenthrough 2nd grade child in the school districtis rated using the early literacy scale. As statedin the district’s guidelines, “The ratings arebased solely on information in the student’sportfolio. Placing students on the scale isintended to serve two purposes. First, the pro-cess requires that teachers review and summa-rize each student’s progress at a designated pointin time. Second, the ratings are used by the

AN EFFECTIVE EARLY LITERACY ASSESSMENT SYSTEM

In considering these many prerequisites for an effec-tive early literacy assessment system, it is helpful to examine an actual system—a place where thenecessary components have been brought together successfully.

023990_PIP_TEXT_EarlyLit 5/30/03, 10:14 AM24

EARLY LITERACY ASSESSMENT SYSTEMS • 25

023990 88 02 P li I f P i d fil PM6 f @1 R d 6 03 k j 2CE /14/03 kb /1 /03 l

� Self-portrait � Student Interviews � Parent Questionnaire � Concept About Print Test � Phonemic Awareness � WAWA II � Alphabet Test � Word Analysis � Word Lists � Running Record Assessment � Writing Sample � Story Retelling � Nonfiction Retelling � Higher Order Comprehension

FIGURE 9: COMPONENTS OF THE SOUTH

BRUNSWICK PORTFOLIO

district, in place of first- and second-gradereading tests, to monitor and evaluate the suc-cess of our students and the early childhoodprogram.”26

It is important to emphasize that estab-lishing a common set of procedural guidelinesfor collecting work samples would not besufficient by itself to sustain the assessmentsystem; mechanisms must be in place to fos-ter teacher professional development and col-laboration.

Indeed, a critical factor in the success ofthe South Brunswick, New Jersey, schooldistrict’s early literacy portfolio and scale isthe district’s emphasis on intense teacher

professional development. Leaders in the dis-trict recognized that successful systemic imple-mentation of the Early Literacy Portfolio andits developmental scale required several lay-ers of ongoing district support. Beyond thedefinition of a common set of assumptionsor guidelines, the following institutionalmechanisms were needed to foster andsustain professional conversation amongteachers.

Development Committee - The Early Lit-eracy Portfolio Development Committee,consisting of teachers, was responsible fordesigning the original portfolio and thedevelopmental scale and for reviewing andrevising the assessment.

Training Workshops - Throughout theschool year, the district sponsors trainingworkshops and “same-grade” meetings forall primary-level teachers, as well as work-shops for all new staff.

Portfolio Scale/Calibration Meetings -These meetings provide one of the mostpowerful professional development oppor-tunities in the district. They are viewed byteachers as useful in building a consensusand a common language, refining their rat-ing skills, helping to standardize the port-folio procedures, and broadening theirunderstanding of the entire rating process.

26 South Brunswick, New Jersey, Early Literacy Portfolio Guidelines, 1999 (Portfolio Manual Directions, p. 6).

023990_PIP_TEXT_EarlyLit 5/30/03, 10:14 AM25

26 • EARLY LITERACY ASSESSMENT SYSTEMS

023990 88 02 P li I f P i d fil PM6 f @1 R d 6 03 k j 2CE /14/03 kb /1 /03 l

Child’s Name ________________________________ Grade K 1 2

Primary Reading/Writing ScaleDevelopment of children’s strategies for making sense of print

Directions: To record score, insert date and circle appropriate levelRecord child’s name and gradePlace form in the student’s portfolio

Date ______________________

Level 1: EARLY EMERGENTDisplays an awareness of some conventions of reading, such as front/back of books, distinctionsbetween print and pictures. Sees the construction of meaning from text as “magical” or exterior to theprint. While the child may be interested in the contents of books, there is as yet little apparentattention to turning written marks into language. Is beginning to notice environmental print.

Level 2: ADVANCED EMERGENTEngages in pretend reading and writing. Uses reading-like ways that clearly approximate booklanguage. Demonstrates a sense of the story being “read,” using picture clues and recall of story line.May draw upon predictable language patterns in anticipating (and recalling) the story. Attempts touse letters in writing, sometimes in random or scribble fashion.

Level 3: EARLY BEGINNING READERAttempts to “really read.” Indicates beginning sense of one-to-one correspondence and concept ofwords. Predicts actively in new material, using syntax and story line. Small stable sight vocabulary isbecoming established. Evidence of initial awareness of beginning and ending sounds, especially ininvented spelling.

Level 4: ADVANCED BEGINNING READERStarts to draw on major cue systems; self-corrects or identifies words through use of letter-soundpatterns, sense of story, or syntax. Reading may be laborious especially with new material, requiringconsiderable effort and some support. Writing and spelling reveal awareness of letter patterns.Conventions of writing such as capitalization and full stops are beginning, but are not consistent.

Level 5: EARLY INDEPENDENT READERHandles familiar material on own, but still needs some support with unfamiliar material. Figures outwords and self-corrects by drawing on a combination of letter-sound relationships, word structure,story line and syntax. Strategies of re-reading or of guessing from larger chunks of texts are becom-ing well established. Has a large stable sight vocabulary. Conventions of writing are understood.

Level 6: ADVANCED INDEPENDENT READERReads independently, using multiple strategies flexibly. Monitors and self-corrects for meaning. Canread and understand material when the content is appropriate. Writes with some fluency. Ideasremain on the topic and are conveyed in a logical sequence. Conventions of writing and spelling are—for the most part—under control.

Rating scale developed by South Brunswick teachers and ETS staff - January 1991

FIGURE 10: SOUTH BRUNSWICK EARLY LITERACY SCALE: SCORING FORM

023990_PIP_TEXT_EarlyLit 5/30/03, 10:14 AM26

EARLY LITERACY ASSESSMENT SYSTEMS • 27

023990 88 02 P li I f P i d fil PM6 f @1 R d 6 03 k j 2CE /14/03 kb /1 /03 l

During the scale calibration meetings,teachers across the district read, discuss, andrate their colleagues’ Early Literacy Portfolios.Working in pairs, teachers are presented withthe portfolio of a child they do not know, otherthan by the evidence in the portfolio. Theteachers use these portfolio documents toassign a rating on the portfolio’s six-point scale.This rating is then compared with the ratingassigned by the child’s own classroom teacher.Agreement coefficients have consistentlyranged from the mid .80’s to the low .90’s.27

In the unlikely case of a disagreement of morethan one scale point, a third party mediatesthe discussion until consensus is achieved.As a result of these meetings, the teacher whoseportfolio has been rated might revise the scoreand review the documents in a specificportfolio. The double scoring procedures pro-vide an opportunity to discuss documents,review scoring standards, and assure thatconsistent scoring standards are maintainedacross the district.28

27 Bridgeman et al., 1995.

28 Jones and Chittenden, 1995.

023990_PIP_TEXT_EarlyLit 5/30/03, 10:14 AM27

Improving literacy development for all chil-dren and closing the achievement gap requirea system-wide commitment to ongoing pro-fessional development in early literacy acqui-sition, instruction, and assessment. A usefulassessment system requires:

� Multiple literacy assessments. The coher-ent use of an array of instrumentsconsisting of screening, diagnostic, andclassroom-based instruments to informinstructional practice and to evaluate pro-gram effectiveness is essential.

� Strong and stable leadership. While class-room teachers play a critical role inchildren’s learning, the success of any sus-tained system-wide change requires solidadministrative support. Someone mustguide the process by providing sufficienttime and resources to teachers, and some-one must hold fast to the vision forthe work.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Monitoring the literacy development of youngchildren and evaluating the effectiveness of programs cannot be accomplished by administering a

single test during the academic year.

� Coherent professional development pro-grams. Good intentions alone are not suf-ficient. Effective assessment systems rely onwell-trained and reflective teachers whounderstand cognitive and literacy develop-ment as well as the basic concepts ofappropriate assessment.

These are difficult systems to design andimplement, as evidenced by the paucityof model programs. The financial resourcesbeing allocated for literacy testing will onlybe useful to children and teachers if we recog-nize the critical role played by multiple formsof assessment in the teaching and learningprocess and begin to examine how to makesystem-wide changes that incorporateprofessional development for teachers andadministrators.

28 • EARLY LITERACY ASSESSMENT SYSTEMS

023990_PIP_TEXT_EarlyLit 5/30/03, 10:14 AM28

IBC blank

023990-88502 • Policy Info Perspective • from Marketing to Pubs 5.6.03 kaj • 2CE 5/14/03 kb • code/preflight 5/19/03 jdj

023990_Cover 5/30/03 10:10 AM Page 4